Abstract

People with diabetes or prediabetes face a higher risk of cardiovascular events. However, the impact of sex and menopausal hormone therapy on cardiovascular disease (CVD) in these individuals remains unclear. We examined cardiovascular event risk and the association between menopausal hormone therapy and CVD risk in female Koreans with diabetes or prediabetes. We utilized the National Health Insurance Service database from 2009 to 2019. People undergoing hemodialysis or with an eGFR < 15 mL/min/1.73 m2 were excluded. We analyzed 1,313,591 people with prediabetes and 890,184 people with diabetes without a history of heart failure. Additionally, we examined 1,180,576 people with prediabetes and 673,688 people with diabetes without a history of acute myocardial infarction or stroke. Hazard ratios (HRs) for CVD risk were calculated using Cox proportional hazards models. Women with diabetes had a higher risk of heart failure compared to men with diabetes (HR: 1.095, 95% CI 1.068 to 1.123), a pattern also seen in people with prediabetes (HR: 1.150, 95% CI 1.118 to 1.183). Conversely, women with diabetes had a lower risk of acute myocardial infarction (HR: 0.507, 95% CI 0.486 to 0.528) and stroke (HR: 0.787, 95% CI 0.771 to 0.804) compared to men with diabetes, which was similarly observed in people with prediabetes. Hormone therapy was linked to a reduced risk of ischemic stroke in postmenopausal women with diabetes (HR: 0.761, 95% CI 0.589 to 0.983) and prediabetes (HR: 0.659, 95% CI 0.488 to 0.889). Women with diabetes or prediabetes have a higher risk of heart failure than men. More intensive screening and management of heart failure are needed, especially for these women. Conversely, women with diabetes or prediabetes have a lower risk of acute myocardial infarction and stroke compared to men. Menopausal hormone therapy may help prevent ischemic stroke in postmenopausal women with diabetes or prediabetes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The global prevalence of diabetes is rising due to increasing obesity and lifestyle changes. Individuals with diabetes face a higher risk of cardiovascular diseases (CVD) and mortality. Among those with type 2 diabetes, CVD is the leading cause of morbidity and mortality1,2. Besides atherosclerotic CVD, including ischemic heart disease, stroke, and peripheral vascular disease, heart failure is a common complication of diabetes3,4.

Previous studies have shown sex differences in CVD outcomes, including heart failure5,6. While diabetes is a known risk factor for CVD, sex-specific outcomes in diabetic patients are inconsistent. Diabetic women have lower left ventricular global longitudinal strain compared to non-diabetic women, but this difference is less pronounced in men7. A retrospective registry study in Japan found that women with type 2 diabetes and coronary artery disease had a higher risk of heart failure hospitalization than men8. Diabetes significantly increases the mortality risk of patients with heart failure, more so in women than men among Caucasians hospitalized with congestive heart failure9. However, another study found that sex was not a significant predictor of congestive heart failure incidence in diabetic patients without existing congestive heart failure10. Data from Finnish and Swedish cohorts showed that diabetic men have a higher risk of coronary heart disease and ischemic stroke than diabetic women11.

In postmenopausal diabetic women, the risk of coronary heart disease events increases with age and worsening risk factors12. The effects of hormone therapy on CVD risk are inconsistent13. Although hormone therapy has been reported to improve glycemic control, its impact on CVD outcomes in postmenopausal women with diabetes or prediabetes is unclear14. Menopausal hormone therapy was linked to reduced CVD risk in white women with prediabetes or diabetes but not in black women15. According to the Korea National Health Insurance Service Database, menopausal hormone therapy was not associated with CVD or type 2 diabetes in middle-aged postmenopausal women16. This study examined cardiovascular event risk and the association between menopausal hormone therapy and CVD risk in female Koreans with diabetes or prediabetes.

Materials and methods

Data source

We utilized the National Health Insurance Service database from January 1, 2009, to December 31, 2019. Data were assessed for research purposes from August 31, 2023, to September 15, 2023. The National Health Insurance Service is a population-based cohort that conducts health screenings based on national health insurance data in Korea.

Informed consent

was not obtained as the study data had already been collected. The Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Ewha Womans University Mokdong Hospital approved our study. Due to the retrospective nature of the study, IRB of Ewha Womans University Mokdong Hospital waived the need of obtaining informed consent. Patient records were anonymized before release. All methods were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Study population

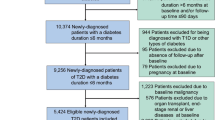

The study included adults aged 40 years or older who underwent a health checkup between January 1, 2009, and December 31, 2010 (n = 2,688,352). Excluding those with missing data, the study population was 2,640,389. After excluding individuals with an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) < 15 mL/min/1.73 m2 (n = 47,452), with a history of chronic kidney disease indicated by ICD-10 codes N18 or N19 (n = 15,913), undergoing hemodialysis (n = 3,115), or with a history of heart failure (n = 59,177), the study population reached 2,523,352. Among them, 2,203,775 people were with prediabetes or diabetes. Finally, we analyzed 1,313,591 people with prediabetes and 890,184 people with diabetes. Additionally, we examined 1,180,576 people with prediabetes and 673,688 people with diabetes without a history of acute myocardial infarction or stroke. Participants were observed until the earliest occurrence of a CVD event, death, or the last follow-up on December 31, 2019. A flowchart detailing the participant selection process is shown in Fig. 1.

Diabetes was defined by the E10–14 codes of the 10th edition of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10) a prescription for oral glucose-lowering medications or insulin for more than 30 days or fasting glucose of 126 mg/dL or higher. Prediabetes was defined as fasting glucose between 100 and 125 mg/dL without meeting the diagnostic criteria for diabetes. Menopausal status was determined by having an ICD-10 code (N95), being over 60 years old, or using a self-report questionnaire.

Outcome variables and covariates

The primary outcome was the time to CVD occurrence, identified using ICD-10 codes: I21 for acute myocardial infarction, I60–I62 for hemorrhagic stroke, I63 for ischemic stroke, I60–I63 for stroke, and I50 for heart failure.

Smoking status was categorized as a current smoker or non/ex-smoker. Alcohol consumption was classified as heavy drinking (> 2 drinks/day for men and > 1 drink/day for women) or non-heavy drinking (≤ 2 drinks/day for men and ≤ 1 drink/day for women). Physical activity was grouped into none, 1 time/week, and ≥ 2 times/week.

Drug prescriptions at the index date were defined as those prescribed for > 30 days. Sociodemographic data (age, sex, smoking status, alcohol consumption, physical activity, and menopausal status for women), physical examination data (body mass index and blood pressure), laboratory test data (fasting glucose, cholesterol, and triglycerides), and treatment data (use of hypoglycemic agents, antihypertensives, and lipid-lowering therapies) were collected at the index date. The index date was the time of health screening after January 1, 2009, and the follow-up period from the index date to the occurrence of CVD, death, or the end of the study on December 31, 2019.

Statistical analysis

Baseline characteristics were presented as mean ± standard deviations for continuous variables and as frequency and proportion for categorical variables. We used Cox proportional hazards models to evaluate the risk of CVD events, adjusting for age, smoking status, alcohol consumption, physical activity, drug prescriptions for antihypertensives and lipid-lowering therapies, body mass index, and fasting glucose. Adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals were then calculated. P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS (version 9.4, SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

Baseline characteristics of all participants are shown in Tables 1 and 2. The mean age was 57 years, with about 44% of participants being women among subjects without a history of heart failure. The mean age was 56 years, with about 43% of participants being women among subjects without a history of acute myocardial infarction or stroke. Women were older and had higher levels of total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL cholesterol), and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL cholesterol) than men. The proportions of current smokers and heavy drinkers were lower in women than in men. Women received more lipid-lowering and antihypertensive medications than men.

Baseline information for individuals with diabetes or prediabetes is provided in Supplemental Tables 1 and 2. The mean age was 55 years for those with prediabetes and 60 years for those with diabetes among subjects without a history of heart failure. Among women without a history of heart failure with prediabetes (n = 571,910), 3,668 (0.64%) were prescribed hormones. Among 391,383 women without a history of heart failure with diabetes, 2,971 (0.76%) were receiving hormone treatment. The mean age was 54 years for those with prediabetes and 59 years for those with diabetes among subjects without a history of acute myocardial infarction or stroke. Among women without a history of acute myocardial infarction or stroke with prediabetes (n = 510,596), 3,134 (0.61%) were prescribed hormones. Among 290,023 women without a history of acute myocardial infarction or stroke with diabetes, 2,143 (0.74%) were receiving hormone treatment. Among menopausal women, those on hormone replacement therapy were younger and had lower levels of body mass index, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, fasting glucose, and triglycerides than those not on hormone replacement therapy (data not shown).

During a median follow-up of 11 years, we observed 50,430 heart failure events (men with prediabetes, n = 10,227; men with diabetes, n = 12,788; women with prediabetes, n = 11,792; women with diabetes, n = 15,623), 23,687 acute myocardial infarctions (men with prediabetes, n = 8,992; men with diabetes, n = 8,667; women with prediabetes, n = 2,330; women with diabetes, n = 3,698), and 81,435 stroke events (men with prediabetes, n = 24,671; men with diabetes, n = 24,825; women with prediabetes, n = 14,906; women with diabetes, n = 17,033) were observed (Table 3).

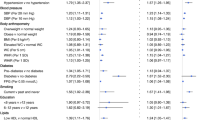

The risk of heart failure was higher in women with diabetes compared to men with diabetes (HR: 1.095, 95% CI 1.068 to 1.123), and a similar pattern was observed in individuals with prediabetes (HR: 1.150, 95% CI 1.118 to 1.183). Conversely, the risk of acute myocardial infarction (HR: 0.507, 95% CI 0.486 to 0.528) and ischemic stroke (HR: 0.759, 95% CI 0.742 to 0.777) was lower in women with diabetes compared to men with diabetes, with the same pattern observed in individuals with prediabetes (HR: 0.330, 95% CI 0.315 to 0.347 for acute myocardial infarction; HR: 0.698, 95% CI 0.681 to 0.716 for ischemic stroke) (Table 4). Hormone therapy was associated with a reduced risk of ischemic stroke in postmenopausal women with diabetes (HR: 0.761, 95% CI 0.589 to 0.983) and prediabetes (HR: 0.659, 95% CI 0.488 to 0.889) (Table 5).

Discussion

Women with prediabetes have a higher risk of heart failure compared to men. However, among people with diabetes or prediabetes, women have a lower risk of acute myocardial infarction or stroke than men. Menopausal hormonal therapy might help prevent ischemic stroke in postmenopausal women with diabetes or prediabetes.

Several studies have examined CVD occurrence by sex among diabetic and non-diabetic individuals. Research indicates that women have a higher risk of heart failure than men17. Consistent with our findings, multiple studies have shown that diabetes increases the risk of heart failure more in women than in men5. The Korean Heart Failure Registry study suggested that diabetes has a stronger impact on mortality and heart failure readmission in women than in men18. From the systematic review and meta-analysis of 47 cohorts, the risk of heart failure with diabetes was greater in diabetic women than in diabetic men19. The ASIAN-HF registry also indicated that diabetes poses a greater risk of adverse outcomes in women than in men20. However, the Framingham study, which began in 1949, found that diabetic men had more than twice the frequency of congestive heart failure, while diabetic women had a fivefold increased risk compared to nondiabetic cohorts over an 18-year follow-up period21.

Contrary to our findings, several studies have shown that diabetic women have a higher risk of coronary heart disease than diabetic men. The adjusted relative risk of death from ischemic heart disease was 2.4 for diabetic men and 3.5 for diabetic women compared to nondiabetics22. In Finland, the diabetes-related HR for major coronary heart disease events was 3.8 for men and 14.7 for women23. Finnish studies also reported higher myocardial infarction mortality in diabetic women compared to men aged 25–74 years24. Among Japanese individuals aged 40 to 79, diabetes diagnosed by an oral glucose tolerance test was an independent risk factor for coronary heart disease in women25. A systematic review and meta-analysis of 64 cohorts found that the excess risk of stroke associated with diabetes was higher in women than in men26. Another meta-analysis of 37 prospective cohort studies reported that the relative risk for fatal coronary heart disease associated with diabetes was higher in women than in men27. The 40-Year Rancho Bernardo Cohort Study suggested that diabetic women lose cardiovascular protection due to multiple CVD risk factors28. However, our study confirmed that diabetic women have a lower risk of acute myocardial infarction or stroke than diabetic men. Consistent with our findings, Spanish diabetic patients without known coronary artery disease showed that men had more major adverse cardiac events than women29. Similarly, at Hartford Hospital, diabetic patients without known coronary artery disease had fewer cardiac events in women compared to men30. Differences in race or CVD risk adjustment might explain the varying results between studies.

The effects of hormone replacement therapy on CVD outcomes are inconsistent across studies15. For instance, the Women’s Health Initiative Randomized Trials found no association between hormone replacement therapy and the risk of all-cause or cardiovascular mortality among multiethnic postmenopausal women31. The impact of hormone therapy on CVD outcomes may depend on the timing of therapy initiation. Among healthy postmenopausal women, those who started estradiol therapy within 6 years of menopause had a lower rate of atherosclerosis compared to those on a placebo. However, this benefit was not observed in women who began therapy 10 or more years after menopause32. Although our study did not consider the timing of hormone therapy initiation, we found that hormone therapy use was associated with a reduced risk of ischemic stroke among postmenopausal women with diabetes or prediabetes after adjusting for various confounding factors.

The mechanism behind sex differences in CVD risk among people with diabetes is not well understood. Factors such as the influence of sex hormones, variations in cardiovascular risk factors over a lifetime, and lifestyle differences may contribute to these disparities17. Women generally have a higher fat mass percentage, particularly in the subcutaneous area and lower extremities, compared to men33. Additionally, women showed a greater increase in intracardiac lipid content between normoglycemic and hyperglycemic states than men34. Specific risk factors for CVD in women include conditions like gestational diabetes and polycystic ovary syndrome17. Differences in CVD risk factors before and after menopause suggest that estrogen plays a role in CVD development35. However, the effect of female hormones, particularly estrogens, on CVD outcomes remains unclear. A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials indicated that hormone replacement therapy does not affect the incidence of coronary events or myocardial infarction36. Overall, the health risks of estrogen plus progestin exceeded the benefits for total CVD outcomes in healthy postmenopausal women, according to the Women’s Health Initiative Randomized Controlled Trial37. Further research is needed to understand the mechanisms of sex differences and the role of menopausal hormone therapy in CVD development among people with diabetes.

Our study has several strengths. It is the first to evaluate sex differences in the risk of cardiovascular events and the association between hormone therapy use and CVD risk in Koreans with diabetes or prediabetes. The large sample size allows our results to be generalized to Korean patients with these conditions. We also adjusted for various confounding factors that could affect CVD risk.

However, our study has limitations. As a retrospective study, we cannot establish a causal relationship between sex or hormone therapy and CVD outcomes. The start time of hormone therapy could not be confirmed, so the duration of hormone treatment is unknown. We did not consider the type, dosage, or administration route of hormone therapy. Previous systematic reviews and meta-analyses have reported that menopausal hormone therapy increases the risk of venous thromboembolism38. Because the effects of menopausal hormone therapy may vary depending on age, time since menopause, and comorbidity status39, the risks and benefits of menopausal hormone therapy should be considered and caution should be used when interpreting the results. Glycated hemoglobin was not used as a diagnostic criterion for diabetes or to assess glycemic control. Obstetric and gynecological factors were not considered. Additionally, we lacked information on the duration of diabetes or prediabetes. The type of heart failure (reduced ejection fraction or preserved ejection fraction) was not taken into account. CVD incidence was assessed using ICD-10 codes and may differ from actual incidence. Lastly, we did not consider the type of hypoglycemic agents used, such as sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors or glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists, which may affect the occurrence of cardiovascular disease40.

In conclusion, there is a need for more intensive screening and management of heart failure, particularly in women with diabetes. Menopausal hormonal therapy might help prevent ischemic stroke in postmenopausal women with diabetes or prediabetes. Further prospective studies are necessary to determine the optimal timing, dosage, and duration of hormone replacement in these women.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed in the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- CVD:

-

Cardiovascular diseases

- ICD-10:

-

International classification of diseases

- HDL:

-

Cholesterol high-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- LDL:

-

Cholesterol low-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- eGFR:

-

Estimated glomerular filtration rate

References

Yang, J. J. et al. Association of diabetes with all-cause and cause-specific mortality in Asia: A pooled analysis of more than 1 million participants. JAMA Netw. Open. 2(4), e192696–e192696 (2019).

Rawshani, A. et al. Mortality and cardiovascular disease in type 1 and type 2 diabetes. N Engl. J. Med. 376(15), 1407–1418 (2017).

Pop-Busui, R. et al. Heart failure: An underappreciated complication of diabetes. A consensus report of the American diabetes association. Diabetes Care 45(7), 1670–1690 (2022).

McMurray, J. J. & Sattar, N. Heart failure: Now centre-stage in diabetes. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 10(10), 689–691 (2022).

Fourny, N. et al. Sex differences of the diabetic heart. Front. Physiol. 12, 661297 (2021).

Lam, C. S. et al. Sex differences in heart failure. Eur. Heart J. 40(47), 3859–68c (2019).

Kwak, S. et al. Sex-specific impact of diabetes mellitus on left ventricular systolic function and prognosis in heart failure. Sci. Rep. 11(1), 11664 (2021).

Fujita, Y. et al. Women with type 2 diabetes and coronary artery disease have a higher risk of heart failure than men, with a significant gender interaction between heart failure risk and risk factor management: A retrospective registry study. BMJ Open. Diabetes Res. Care. 10 (2), e002707 (2022).

Gustafsson, I. et al. Influence of diabetes and diabetes-gender interaction on the risk of death in patients hospitalized with congestive heart failure. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 43(5), 771–777 (2004).

Nichols, G. A., Gullion, C. M., Koro, C. E., Ephross, S. A. & Brown, J. B. The incidence of congestive heart failure in type 2 diabetes: An update. Diabetes Care. 27 (8), 1879–1884 (2004).

Hyvärinen, M. et al. The impact of diabetes on coronary heart disease differs from that on ischaemic stroke with regard to the gender. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 8, 1–5 (2009).

Kim, C. Management of cardiovascular risk in perimenopausal women with diabetes. Diabetes Metab. J. 45(4), 492–501 (2021).

Mosca, L. et al. Hormone replacement therapy and cardiovascular disease: A statement for healthcare professionals from the American heart association. Circulation 104(4), 499–503 (2001).

Paschou, S. A. & Papanas, N. Type 2 diabetes mellitus and menopausal hormone therapy: an update. Diabetes Ther. 10(6), 2313–2320 (2019).

Yoshida, Y. et al. Menopausal hormone therapy and risk of cardiovascular events in women with prediabetes or type 2 diabetes: A pooled analysis of 2917 postmenopausal women. Atherosclerosis 344, 13–19 (2022).

Kim, J-E. et al. Effects of menopausal hormone therapy on cardiovascular diseases and type 2 diabetes in middle-aged postmenopausal women: Analysis of the Korea National health insurance service database. Menopause 28 (11), 1225–1232 (2021).

Regensteiner, J. G. et al. Sex differences in the cardiovascular consequences of diabetes mellitus: a scientific statement from the American heart association. Circulation 132(25), 2424–2447 (2015).

Kim, H. L. et al. Gender difference in the impact of coexisting diabetes mellitus on long-term clinical outcome in people with heart failure: a report from the Korean heart failure registry. Diabet. Med. 36(10), 1312–1318 (2019).

Ohkuma, T., Komorita, Y., Peters, S. A. & Woodward, M. Diabetes as a risk factor for heart failure in women and men: A systematic review and meta-analysis of 47 cohorts including 12 million individuals. Diabetologia 62, 1550–1560 (2019).

Chandramouli, C. et al. Impact of diabetes and sex in heart failure with reduced ejection fraction patients from the ASIAN-HF registry. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 21(3), 297–307 (2019).

Kannel, W. B., Hjortland, M. & Castelli, W. P. Role of diabetes in congestive heart failure: the Framingham study. Am. J. Cardiol. 34(1), 29–34 (1974).

Barrett-Connor, E. & Wingard, D. L. Sex differential in ischemic heart disease mortality in diabetics: a prospective population-based study. Am. J. Epidemiol. 118(4), 489–496 (1983).

Juutilainen, A. et al. Gender difference in the impact of type 2 diabetes on coronary heart disease risk. Diabetes Care. 27(12), 2898–2904 (2004).

Hu, G., Jousilahti, P., Qiao, Q., Katoh, S. & Tuomilehto, J. Sex differences in cardiovascular and total mortality among diabetic and non-diabetic individuals with or without history of myocardial infarction. Diabetologia 48, 856–861 (2005).

Doi, Y. et al. Impact of glucose tolerance status on development of ischemic stroke and coronary heart disease in a general Japanese population: the Hisayama study. Stroke 41(2), 203–209 (2010).

Peters, S. A., Huxley, R. R. & Woodward, M. Diabetes as a risk factor for stroke in women compared with men: A systematic review and meta-analysis of 64 cohorts, including 775 385 individuals and 12 539 strokes. Lancet 383 (9933), 1973–1980 (2014).

Huxley, R., Barzi, F. & Woodward, M. Excess risk of fatal coronary heart disease associated with diabetes in men and women: meta-analysis of 37 prospective cohort studies. BMJ 332(7533), 73–78 (2006).

Barrett-Connor, E. Why women have less heart disease than men and how diabetes modifies women’s usual cardiac protection: a 40-year rancho Bernardo cohort study. Glob Heart 8(2), 95–104 (2013).

Romero-Farina, G. et al. Gender differences in outcome in patients with diabetes mellitus. J. Nucl. Cardiol. 29(1), 72–82 (2022).

Santos, M. T. H., Parker, M. W. & Heller, G. V. Evaluating gender differences in prognosis following SPECT myocardial perfusion imaging among patients with diabetes and known or suspected coronary disease in the modern era. J. Nucl. Cardiol. 20(6), 1021–1029 (2013).

Manson, J. E. et al. Menopausal hormone therapy and long-term all-cause and cause-specific mortality: the women’s health initiative randomized trials. JAMA 318(10), 927–938 (2017).

Hodis, H. N. et al. Vascular effects of early versus late postmenopausal treatment with estradiol. N Engl. J. Med. 374(13), 1221–1231 (2016).

Power, M. L. & Schulkin, J. Sex differences in fat storage, fat metabolism, and the health risks from obesity: Possible evolutionary origins. Br. J. Nutr. 99(5), 931–940 (2008).

Iozzo, P. et al. Contribution of glucose tolerance and gender to cardiac adiposity. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 94(11), 4472–4482 (2009).

Kander, M. C., Cui, Y. & Liu, Z. Gender difference in oxidative stress: A new look at the mechanisms for cardiovascular diseases. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 21(5), 1024–1032 (2017).

Yang, D., Li, J., Yuan, Z. & Liu, X. Effect of hormone replacement therapy on cardiovascular outcomes: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PLoS One 8(5), e62329 (2013).

Rossouw, J. E. et al. Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women: Principal results from the women’s health initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA 288(3), 321–333 (2002).

Kim, J. E. et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of effects of menopausal hormone therapy on cardiovascular diseases. Sci. Rep. 10(1), 20631 (2020).

Flores, V. A., Pal, L. & Manson, J. E. Hormone therapy in menopause: Concepts, controversies, and approach to treatment. Endocr. Rev. 42(6), 720–752 (2021).

American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee. 9. Pharmacologic approaches to glycemic treatment: Standards of care in diabetes—2024. Diabetes Care 47(Supplement_1), S158-78 (2024).

Funding

This research was supported by a grant from the Ewha Womans University College of Medicine Alumnae 50th Anniversary Memorial Academic Research Fund of 2023.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.K.S., Y-A.S., Y.S.H., M.K., and H.L. were involved in the conception, design, and interpretation of the results. D.K.S. wrote the first draft of the manuscript, and H.L. edited and reviewed the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Song, D.K., Sung, YA., Hong, Y.S. et al. Impact of sex and menopausal hormonal therapy on cardiovascular diseases in people with diabetes or prediabetes. Sci Rep 15, 25450 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-01768-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-01768-8