Abstract

Contour error is a critical factor influencing machining quality. This paper proposes a combined contour error control method for five-axis machine tools based on digital twin. The proposed method combines pre-compensation implemented in digital twin with feedback control in the real-time controller. After obtaining the tool path input, the digital twin performs interpolation and applies model predictive pre-compensation control to the interpolated commands to control modeled errors. The pre-compensated commands and interpolation data are sent to the real-time controller where contour error is estimated and controlled in each control cycle through feedback control to control unmodeled errors. Using the S-shaped curve as the test case, the maximum tool tip position contour error is reduced by 77.78%, with an average reduction of 83.90%. The maximum tool orientation contour error decreased by 79.05%, with an average reduction of 86.66%. The experimental results demonstrate that the proposed method significantly reduces tool contour error.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Five-axis machine tools are widely used for machining complex parts. The limited dynamic bandwidth of servo axes leads to tracking errors during motion. These tracking errors are kinematically transferred to the tool of five-axis machine tools and result in tool deviations from the intended tool path. These deviations are defined as contour error.

Improving the bandwidth of each axis can reduce contour error indirectly but cannot address the dynamic performance mismatches between axes. Therefore, direct control of contour error is currently the focus of research, which can be divided into two directions: contour error estimation (CEE) and contour error control (CEC).

For CEE, since real-time controllers operate in discrete systems, discrete interpolation points are typically used to approximate the ideal curve for contour error estimation. Yang et al.1 proposed a fast iterative method that approximates the ideal contour as a straight line. Yang et al.2 used three interpolation points to fit an intended arc for calculating the contour error. Chen et al.3 conducted a comparative analysis of the computational efficiency of various approximation methods, including straight lines, arcs, and their linear combinations. Pi et al.4 used Ferguson curves to refit the interpolation points. Liu et al.5 proposed a CEE method based on Taylor series expansion and the Frenet-Serret frame to consider the effects of curvature and torsion. Yang et al.6 identified high-curvature regions and modified the contour error vector to avoid abrupt changes. Wang et al.7 proposed an iterative method with Aitken acceleration. Li et al.8 employed a moving window method to compare reference positions and search for the optimal solution. Ghaffari et al.9 proposed a dynamic CEE algorithm based on the Newton update algorithm.

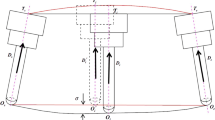

For CEC, typical control methods include feedback control, pre-compensation control, and predictive control10. Control structures of these three methods are illustrated in Fig. 1.

Feedback control calculates the current contour error in each control cycle, decomposes the contour error into each axis, and compensates it by adjusting the control inputs of each axis in the next cycle. Lu et al.11 designed a single-neuron adaptive cross-coupled controller, which dynamically adjusts its weights through a single-neuron learning algorithm to enhance control precision. Zhao et al.12 proposed a controller that integrates feedforward, feedback, and cross-coupled control. Feedback control is simple to implement and can handle the effects of unknown disturbances. However, feedback control always lags the contour error. To address these limitations, researchers have investigated pre-compensation control. Pre-compensation control optimizes control commands in advance through simulation or modeling, enabling compensation before contour errors occur. Pre-compensation control does not rely on the real-time state of the system, so it can be completed in offline conditions. Xu et al.13 proposed a 1DCNN-BiLSTM-Attention model to predict and compensate contour errors. Wang et al.14 proposed an iterative pre-compensation method based on a predictive model. Xiao et al.15 proposed a model predictive contour error pre-compensation method. Wang et al.16 analyzed the composition of contour errors in three-axis machine tools and designed a pre-compensation controller. Pi et al.17 further considered the influence of cutting force disturbances. Lyu et al.18 and Duong et al.19 achieved pre-compensation by offline adjustment of servo control gains. Although pre-compensation method can control contour error in advance, its effectiveness depends on the model accuracy which is not easy to fulfill. Recently, predictive control methods such as MPC20,21,22 and generalized predictive control (GPC)5,23 have been applied to contour error control. Based on the current state of the machine tool, predictive control solves multi-objective optimization problems by predicting future states over multiple steps, thereby obtaining the optimal control commands for the current cycle. Compared with pre-compensation control, predictive control compensates based on the system’s current actual state, so it can compensate for errors caused by unmodeled disturbances. Compared with feedback control, predictive control compensates through multi-step prediction and rolling optimization, so the compensation does not lag the occurrence of errors. However, predictive control involves numerous matrix calculations, which result in a significant computational load on the real-time controller. The application of MPC and GPC in contour error control is mainly focused on two-axis or three-axis platforms. Therefore, it is necessary to consider combining those methods to fully leverage the advantages of each.

As a digital mirror of the real world, digital twin technology has obtained significant attention in recent years24. Many scholars have explored the application of digital twin in CNC machine tools for commissioning25,26, virtual machining27,28, optimization29,30,31,32 and monitoring33,34. However, in the above research, digital twin primarily optimizes the machining process by adjusting feedrate override and few studies have explored combining digital twins with real-time controllers for contour error control. Digital twin can synchronously update with physical machine tools35,36 and handle greater computational loads through cloud computing service37, which meets the requirements of model precision and computation capability of MPC. Therefore, developing a combined contour error control method based on the digital twin effectively meets the requirements for both control accuracy and computational load.

This paper presents a combined contour error control method based on the digital twin. After obtaining the tool path input, the digital twin performs interpolation and applies model predictive pre-compensation control (MPCC) to the interpolated commands to control modeled errors. The pre-compensated commands and interpolation data are sent to the real-time controller which estimates and controls contour error in each control cycle by feedback control to control unmodeled errors.

The remaining sections of this paper are organized as follows: “Principle of proposed method” introduces the principle of the proposed method. Section “Digital twin for contour error control” describes the software architecture of the digital twin, as well as the servo dynamic model and the machine kinematics model. Section “Combined contour error control method” presents the offline model predictive pre-compensation control and the online feedback control method. Finally, “Experiment” demonstrates the experimental results and discusses their implications.

Principle of proposed method

The combined contour error control method for five-axis machine tools based on digital twin is shown in Fig. 2. The contour error control is divided into two steps: offline pre-compensation implemented in the digital twin and online control executed in the real-time controller.

The NURBS toolpath and processing information generated by CAM are input into the digital twin. The NURBS direct interpolator of the digital twin processes the tool path to generate interpolation commands. Subsequently, the simulation module, which includes the machine tool kinematics model and servo dynamics model, executes simulations of the interpolation commands. Meanwhile, the pre-compensation module simultaneously compensates for the interpolation commands and ultimately generates the pre-compensated commands. Then the interpolation commands, the pre-compensated commands, and other required data are sent to the real-time controller via the Beckhoff Automation Device Specification (ADS) protocol.

In the real-time controller, the online controller estimates the contour error in each control cycle and generates compensation commands. The resulting commands are then transmitted via the industrial ethernet to the servo drives. The real-time data (axis position, axis velocity, axis current, etc.) sampled at each interpolation cycle is also transmitted to the digital twin adapter via EtherCAT and formatted into structured data. Then the formatted data is sent to the database as machining history data for storage via ethernet. The machine status data is transmitted to the digital twin monitoring module via ADS every 100 ms. The digital twin periodically reads machining historical data from the database, analyzes machining performance and updates simulation model parameters through parameter identification module. If the machining quality still fails to meet requirements, the feedrate and toolpath can be further optimized using methods from the reference30,38,39,40 to enhance the accuracy of subsequent machining processes.

Digital twin for contour error control

Architecture of the digital twin

The functional architecture of the digital twin developed in this paper is shown in Fig. 3. The software was developed using C + + on the Visual Studio 2019 platform, with the visualization interface implemented using Qt 5.

Servo dynamic model

Currently, the servo feed axis commonly employs proportional-proportional-integral (PPI) control. The control model of servo axis is illustrated in Fig. 4.

Where \(\:{K}_{\text{p}}\) is the proportional gain coefficient of the position loop. \(\:{K}_{\text{v}}\) is the proportional gain coefficient of the velocity loop. \(\:{K}_{\text{i}\text{v}}\) is the integral gain coefficient of the velocity loop. \(\:{K}_{\text{t}}\:\)is the torque constant of motor. \(\:{J}_{\text{m}}\) is the equivalent mass. \(\:{C}_{m}\) is the equivalent damping coefficient and \(\:{r}_{\text{g}}\) is the transmission coefficient. \(\:{T}_{\text{l}\text{o}\text{a}\text{d}}\) is the external load torque including Coulomb friction \(\:{f}_{\text{c}}\). \(\:{p}_{\text{c}\text{m}\text{d}}\) is the command input position, \(\:{p}_{\text{a}\text{c}\text{t}}\) is the actual response position, \(\:{\omega\:}_{\text{a}\text{c}\text{t}}\) is the actual angular velocity, \(\:{o}_{\text{a}\text{c}\text{t}}\) is the output of the velocity loop integrator. Let the state vector be \(\:\varvec{x}={\left[\begin{array}{ccc}{p}_{\text{a}\text{c}\text{t}}&\:{\omega\:}_{\text{a}\text{c}\text{t}}&\:{o}_{\text{a}\text{c}\text{t}}\end{array}\right]}^{\text{T}}\), output vector be \(\:\varvec{y}=\left[{p}_{\text{a}\text{c}\text{t}}\right]\), input vector be \(\:\varvec{u}=\left[{p}_{\text{c}\text{m}\text{d}}\right]\) and disturbance vector be \(\:\varvec{d}=\left[{T}_{\text{l}\text{o}\text{a}\text{d}}\right]\), the above system can be described as Eq. (1).

where

Assuming that \(\:\varvec{u}\) and \(\:\varvec{d}\) remain constant in an interpolation cycle, the system described by Eq. (1) can be discretized using a zero-order hold (ZOH). The resulting discrete system can be expressed as Eq. (2):

where

The position loop proportional gain coefficient, velocity loop proportional gain coefficient, velocity loop integral gain coefficient, and torque constant in the above model can typically be obtained directly from the servo driver. Parameters such as mass, viscous friction, and Coulomb friction can be identified using the methods described in references4,41.

Machine tool kinematic model

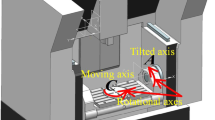

As illustrated in Fig. 5, this paper uses an AC head-type CNC machine tool as an example. The forward and inverse kinematics transformations are established using the method described in reference42.

Let the tool tip coordinates be denoted as \(\:{\left[{p}_{\text{t}x},{p}_{\text{t}y},{p}_{\text{t}z}\right]}^{\text{T}}\), the tool orientation vector as \(\:{\left[{O}_{\text{t}i},{O}_{\text{t}j},{O}_{\text{t}k}\right]}^{\text{T}}\). and servo axis coordinates as \(\:{\left[{p}_{\text{m}x},{p}_{\text{m}y},{p}_{\text{m}z},{p}_{\text{m}a},{p}_{\text{m}c}\right]}^{\text{T}}\) The forward kinematics transformation is expressed in Eq. (3).

where \(\:{x}_{0},{y}_{0},{z}_{0},{a}_{0},{c}_{0}\) are the zero offsets from the workpiece coordinate system (WCS) to the machine coordinate system (MCS).\(\:L\) is the tool length and in this paper \(\:L=75\:\text{m}\text{m}\).

From Eq. (3), the inverse kinematics equations can be obtained as Eq. (4).

Combined contour error control method

Definition of contour error

As shown in Fig. 6, \(\:\varvec{C}\left(u\right)\) is the ideal tool tip position path, and \(\:{\varvec{P}}_{\text{r}\text{t}},{\varvec{O}}_{\text{r}\text{t}}\) are the ideal interpolation tool tip position (TTP) and tool orientation (TORI) vectors. \(\:{\varvec{P}}_{\text{a}\text{t}}\left(k\right),{\varvec{O}}_{\text{a}\text{t}}\left(k\right)\) represent the actual TTP and TORI at the k-th cycle. The five-axis contour error encompasses both TTP error and TORI error. In current research, contour error is often defined as the shortest distance or normal distance from the actual position to the ideal trajectory. The point on the ideal trajectory closest to the actual position is identified as the foot point \(\:{\varvec{P}}_{\text{f}}\), with the corresponding tool orientation being \(\:{\varvec{O}}_{\text{f}}\). Considering computational stability and efficiency, this paper employs the iterative method proposed in reference1 to find \(\:{\varvec{P}}_{\text{f}}\).

Since the interpolation cycle is typically very short, the command trajectory between two adjacent interpolation points can be approximated as a straight line. At this time, \(\:{\varvec{P}}_{\text{f}}\) lies on the line \(\:\overrightarrow{{\varvec{P}}_{\text{r}\text{t}}\left(i-1\right){\varvec{P}}_{\text{r}\text{t}}\left(i\right)}\) formed by the two adjacent interpolation points \(\:{\varvec{P}}_{\text{r}\text{t}}\left(i-1\right),{\varvec{P}}_{\text{r}\text{t}}\left(i\right)\), and can be expressed as

where

From the geometric relationship, it is known that \(\:\overrightarrow{{\varvec{P}}_{\text{a}\text{t}}\left(k\right){\varvec{P}}_{\text{f}}}\perp\:\overrightarrow{{\varvec{P}}_{\text{r}\text{t}}\left(i-1\right){\varvec{P}}_{\text{r}\text{t}}\left(i\right)}\), i.e., \(\:{\left(\overrightarrow{{\varvec{P}}_{\text{a}\text{t}}\left(k\right){\varvec{P}}_{\text{f}}}\right)}^{\text{T}}\cdot\:\left(\overrightarrow{{\varvec{P}}_{\text{r}\text{t}}\left(i-1\right){\varvec{P}}_{\text{r}\text{t}}\left(i\right)}\right)=0\). Substituting into Eq. (5), we have

During the search process, the value of \(\:{h}_{i}\) can be categorized into five cases, as illustrated in Fig. 7. When \(\:0\le\:{h}_{i}\le\:1\), it indicates that \(\:{\varvec{P}}_{\text{f}}\) lies between \(\:{\varvec{P}}_{\text{r}\text{t}}\left(i-1\right),{\varvec{P}}_{\text{r}\text{t}}\left(i\right)\). If \(\:{h}_{i}<0\) occurs, the search is restarted forward to determine whether \(\:{\varvec{P}}_{\text{f}}\) is located between \(\:{\varvec{P}}_{\text{r}\text{t}}\left(i-2\right),{\varvec{P}}_{\text{r}\text{t}}\left(i-1\right)\), and this iteration continues until the situations shown in Fig. 7(a) or (d) are satisfied. Conversely, if \(\:{h}_{i}>1\), the search proceeds backward until the conditions shown in Fig. 7(a) or (e) are satisfied. The process can start from the current cycle command point and the previous cycle command point, \(\:{\varvec{P}}_{\text{r}\text{t}}\left(k\right)\) and \(\:{\varvec{P}}_{\text{r}\text{t}}\left(k-1\right)\).

After identifying the interval where \(\:{\varvec{P}}_{\text{f}}\) lies, the value of \(\:{\varvec{P}}_{\text{f}}\) can be determined by Eq. (5). The tool orientation vector \(\:{\varvec{O}}_{\text{f}}\) corresponding to \(\:{\varvec{P}}_{\text{f}}\) can be obtained through spherical linear interpolation of the tool orientation at the two interpolation points in the interval, as shown in Eq. (7)

where \(\:\theta\:\) is the angle between \(\:{\varvec{O}}_{\text{r}\text{t}}\left(i-1\right)\) and \(\:{\varvec{O}}_{\text{r}\text{t}}\left(i\right)\).

After obtaining \(\:{\varvec{P}}_{\text{f}}\) and \(\:{\varvec{O}}_{\text{f}}\), the TTP contour error and TORI contour error can be calculated by Eq. (8)

Contour error model predictive pre-compensation control

The principle of model predictive pre-compensation control is shown in Fig. 8. In the digital twin, the predictive controller reads the interpolation commands from the interpolator, optimizes axis commands via predictive control and then outputs the pre-compensated commands for the real-time controller.

As analyzed in the previous section, the tool contour error is not equivalent to the tool tracking error. It depends not only on the command point but also on the characteristics of the nearby curve. And calculating the contour error often requires information from several adjacent command points and iterative computations, making it impossible to express it as a linear combination of the position of each axis. However, since the tool command posture must lie on the ideal contour, the tracking error of the current point \(\:{\varvec{P}}_{\text{a}\text{t}}\left(k\right)\) relative to its corresponding command point \(\:{\varvec{P}}_{\text{r}\text{t}}\left(k\right)\:\)serves as the upper bound of its contour error. Therefore, reducing the tool tracking error remains beneficial for minimizing the tool contour error. Additionally, the tool tracking error can be conveniently linearized to facilitate pre-compensation control.

Assuming that the disturbance changes slowly compared to the sampling control cycle, the incremental form can be used to eliminate its influence. Define \(\:\varDelta\:{\varvec{u}}_{q}\left(k\right)={\varvec{u}}_{q}\left(k\right)-{\varvec{u}}_{q}\left(k-1\right),\varDelta\:{\varvec{x}}_{q}\left(k\right)=\:{\varvec{x}}_{q}\left(k\right)-{\varvec{x}}_{q}\left(k-1\right),\:\:\varDelta\:{\varvec{y}}_{q}\left(k\right)=\:{\varvec{y}}_{q}\left(k\right)-{\varvec{y}}_{q}\left(k-1\right),(q=X,Y,Z,A,C)\). Then Eq. (2) can be written as Eq. (9):

For a machine tool with five coordinate axes(X/Y/Z/A/C), let its state be \(\:{\varvec{x}}_{\text{m}}={\left[{\varvec{x}}_{X}^{\text{T}}\:\:{\varvec{x}}_{Y}^{\text{T}}\:\:{\varvec{x}}_{Z}^{\text{T}}\:\:{\varvec{x}}_{A}^{\text{T}}\:\:{\varvec{x}}_{C}^{\text{T}}\right]}^{\text{T}}\), the output be the positions of each coordinate axis, i.e., \(\:{\varvec{y}}_{\text{m}}={\left[{\varvec{y}}_{X}^{\text{T}}\:\:{\varvec{y}}_{Y}^{\text{T}}\:\:{\varvec{y}}_{Z}^{\text{T}}\:\:{\varvec{y}}_{A}^{\text{T}}\:\:{\varvec{y}}_{C}^{\text{T}}\right]}^{\text{T}}\), and the input be the command positions of each axis, i.e., \(\:{\varvec{u}}_{\text{m}}={\left[{\varvec{u}}_{X}^{\text{T}}\:\:{\varvec{u}}_{Y}^{\text{T}}\:\:{\varvec{u}}_{Z}^{\text{T}}\:\:{\varvec{u}}_{A}^{\text{T}}\:\:{\varvec{u}}_{C}^{\text{T}}\right]}^{\text{T}}\). Then, expressing the machine state in incremental form, we have

where

Since the rotational axes generally rotate at a slower speed, it is assumed that the angular increment within an interpolation cycle is very small. Under this assumption, the approximations \(\:\text{s}\text{i}\text{n}\left(\theta\:+\varDelta\:\theta\:\right)\approx\:\text{s}\text{i}\text{n}\theta\:+\varDelta\:\theta\:\text{c}\text{o}\text{s}\theta\:\) and \(\:\text{c}\text{o}\text{s}\left(\theta\:+\varDelta\:\theta\:\right)=\text{c}\text{o}\text{s}\theta\:-\varDelta\:\theta\:\text{s}\text{i}\text{n}\theta\:\) can be applied. Taking \(\:{p}_{\text{t}x}\) in Eq. (3) as an example, we obtain

Since the angular increment is very small, \(\:\varDelta\:{p}_{\text{m}a}\varDelta\:{p}_{\text{m}c}\) can be regarded as higher-order infinitesimal quantities relative to the angular increment. Therefore, Eq. (11) can be approximated as Eq. (12).

Equation (3) can be approximated and expressed in incremental form as shown in Eq. (13).

Equation (13) can be written as Eq. (14):

where

Then the incremental form of the system can be written as Eq. (15).

This paper employs MPC method to implement pre-compensation control. By looking ahead N steps and using the incremental form, the system state can be expressed as Eq. (16).

Let the N-step ahead prediction state be defined as \(\:{\varvec{X}}_{\text{m}}\left(k+N\right)={\left[\begin{array}{cccc}{\varvec{x}}_{\text{m}}^{\text{T}}\left(k+1\right)&\:{\varvec{x}}_{\text{m}}^{\text{T}}\left(k+2\right)&\:\cdots\:&\:{\varvec{x}}_{\text{m}}^{\text{T}}\left(k+M\right)\end{array}\right]}^{\text{T}}\), and the N-step ahead control command as \(\:{\varvec{U}}_{\text{m}}\left(k+N\right)={\left[\begin{array}{cccc}{\varvec{u}}_{\text{m}}^{\text{T}}\left(k+1\right)&\:{\varvec{u}}_{\text{m}}^{\text{T}}\left(k+2\right)&\:\cdots\:&\:{\varvec{u}}_{\text{m}}^{\text{T}}\left(k+M\right)\end{array}\right]}^{\text{T}}\). Then we have

where

The N-step ahead output incremental state can be described as Eq. (18):

where

The N-step ahead output states are:

Therefore, we have

where

Define pre-compensation increment \(\:\varvec{v}{\left(k\right)}_{5N\times\:1}\), the final reference command is defined as \(\:{\varvec{u}}_{\text{r}}\left(k\right)={\varvec{u}}_{\text{m}}\left(k\right)+\varvec{v}\left(k\right)\). Equation (20) can be rewritten as:

where \(\:\varvec{V}\left(k+N\right)={\left[\begin{array}{cccc}{\varvec{v}}^{\text{T}}\left(k\right)&\:{\varvec{v}}^{\text{T}}(k+1)&\:\cdots\:&\:{\varvec{v}}^{\text{T}}(k+N)\end{array}\right]}^{T}\)

Let the desired positions of each axis and the desired tool posture be denoted as \(\:{\varvec{Y}}_{\text{m}\text{r}}\left(k+N\right),{\varvec{Y}}_{\text{m}\text{t}}\left(k+N\right)\), respectively. The cost function is taken as

where \(\:{\left\{{\varvec{Q}}_{\text{m}}\right\}}_{5N\times\:5N},{\left\{{\varvec{Q}}_{\text{t}}\right\}}_{6N\times\:6N},{\left\{{\varvec{Q}}_{\text{u}}\right\}}_{5N\times\:5N}\) are weight matrices. The diagonal elements of these matrices represent the weights assigned to each predicted quantity, all of which are real numbers greater than 0, while the off-diagonal elements are set to 0.

Equation (22) indicates that the cost function incorporates the tracking errors of each axis, the tool tracking errors, and the pre-compensation increment. The next step involves determining its minimum value.

Let

Taking the derivative of Eq. (22), we have

Let \(\:\partial\:J/\partial\:\varvec{V}=0\), we have

In each cycle, only the first set of commands in \(\:\varvec{V}\left(k\right)\) is taken as the output for the current cycle. Therefore, the final reference command for this cycle is

where

Contour error online feedback control

After obtaining the pre-compensation command, this paper further designs an online contour error feedback controller to achieve more precise control of contour error. In the real-time controller, the foot point can be located using the contour error calculation method described earlier. Once the tool position and orientation at the foot point, \(\:{\varvec{P}}_{\text{f}}\) and \(\:{\varvec{O}}_{\text{f}}\), are obtained, the corresponding positions of each axis can be determined through inverse kinematics using Eq. (4). The difference between these positions and the current axis coordinates yields the components of the contour error projected onto each servo axis, denoted as \(\:{\varvec{\epsilon\:}}_{\text{m}}={\left[\begin{array}{ccccc}{\epsilon\:}_{x}&\:{\epsilon\:}_{y}&\:{\epsilon\:}_{z}&\:{\epsilon\:}_{a}&\:{\epsilon\:}_{c}\end{array}\right]}^{\text{T}}\).

This component is utilized as the compensation amount \(\:\varDelta\:{u}_{\text{e}}\). To prevent system oscillation, a gain coefficient \(\:{K}_{\text{c}\text{e}}\:\)is introduced, and a limiter is applied to ensure system stability. The final reference control increment is:

The principle of online feedback control is shown in Fig. 9:

Experiment

To validate the method proposed in this paper, an experimental system was constructed, as illustrated in Fig. 10. The system includes a five-axis motion platform, a real-time controller, and a digital twin. The control system of this platform is developed by TwinCAT 3 and runs on a Windows 7 industrial computer with an Intel® Core™ i7-6700 CPU @ 3.40 GHz. And the control cycle sets to 2ms.The digital twin platform runs on a workstation with Windows 11, powered by an Intel® Core™ i9-12900 CPU @ 2.40 GHz.

The model parameters of the five-axis motion control platform are shown in Table 1:

This paper adopts an S-shaped curve as the input curve as depicted in Fig. 11. And the curve information is shown in Appendix A, Table A1.The interpolator and the velocity, acceleration, and jerk constraints for each axis are configured according to the settings described in reference43. The feedrate is set to 50 mm/s. The interpolation results are illustrated in Figs. 12 and 13.

As indicated in reference44, the MPCC prediction control cycle should exceed the system time constant to achieve optimal control performance. Therefore, in the offline MPCC stage, the prediction step length is set to \(\:N=10\), \(\:{\varvec{Q}}_{\text{m}}=5{\varvec{I}}_{50\times\:50},{\varvec{Q}}_{\text{t}}=5{\varvec{I}}_{60\times\:60},{\varvec{Q}}_{\text{u}}={\varvec{I}}_{60\times\:60}\). For online control \(\:\varDelta\:{u}_{\text{m}\text{a}\text{x}q}\) is set to 0.02 mm (or rad). The linear encoder resolution of X, Y and Z are both 0.1 μm while the rotator encoder resolution of A and C are 220 pulses/rev and 217 pulses/rev. The sampling period is 0.002 s.

To verify the effectiveness of the control methods and the impact of the online feedback control gain \(\:{K}_{\text{c}\text{e}}\) on the control results, the following groups of experiments are compared: (1) no compensation is performed (case 1); (2) only MPCC (case 2); (3) MPCC and online feedback control with \(\:{K}_{\text{c}\text{e}}=0.1\)(case 3) ; (4) MPCC and online feedback control with \(\:{K}_{\text{c}\text{e}}=0.2\) (case 4); (5) MPCC and online feedback control with \(\:{K}_{\text{c}\text{e}}=0.25\) (case 5); (6) MPCC and online feedback control with \(\:{K}_{\text{c}\text{e}}=0.3\) (case 6). The final tool positions and orientations of those cases are shown in Fig. 14.

The tool tracking error is presented in Table 2; Fig. 15. Here, the TTP tracking error and TORI tracking error are defined according to Eq. (8), with the foot point replaced by the command of the current cycle.

It can be observed that after pre-compensation, the tool tracking error of case 2 is significantly reduced than case 1, which achieves the goal of pre-compensation. However, since online feedback control does not account for tool tracking errors, no further improvement in tool tracking error is observed in case 3 – case 6. In terms of average TORI tracking error, case 3 – case 6 have a slight increment compared to case 2. This situation is caused by the different objectives of contour error control and tracking error control. If the dynamic performance of a certain axis is poor, tracking error control will not adjust the response of other axes. However, contour error control will adjust the response of other axes to minimize the contour error, such as reducing the speed of other axes, which may result in a larger tracking error. Considering that tool contour error is a more effective indicator of machining quality, the slight increase in the average tool orientation tracking error is considered acceptable.

The contour error is illustrated in Fig. 16; Table 3. Compared to case 1, pre-compensation significantly reduces TTP contour error and TORI contour error. Specifically, the maximum TTP error is reduced by 72.71%, and its average value is reduced by 80.00%. Similarly, the maximum TORI error is reduced by 74.95%, and its average value is reduced by 83.43%.

Compared to the results of case 2, online control can further reduce the contour error. As \(\:{K}_{\text{c}\text{e}}\) increases, the contour error control effect improves. However, when \(\:{K}_{\text{c}\text{e}}\) is set to 0.3, the system oscillates. Therefore, in this experiment, \(\:{K}_{\text{c}\text{e}}\) = 0.25 (case 5) is more reasonable. The maximum TTP error of case 5 is reduced by 18.58% compared to case 2, and its average value is reduced by 19.48%. The maximum TORI error is reduced by 16.37%, and its average value is reduced by 19.47%. Using this combined method, compared to the uncompensated scenario, the maximum TTP error is reduced by 77.78%, its average value is reduced by 83.90%, the maximum TORI error is reduced by 79.05%, and its average value is reduced by 86.66%. These results demonstrate that the method proposed in this paper effectively reduces contour error. Meanwhile, the iterations required to calculate the contour error are reduced after MPCC, as shown in Table 4. It indicates that pre-compensation control can provide a better basis for online control, effectively reducing the computational load of online control and enhancing the applicability of the control system.

Conclusion

Digital twin has garnered significant attention from both academia and industry. This paper proposes a combined contour error control method for five-axis machine tools based on digital twin. The digital twin established in this paper includes NURBS interpolator, machine kinematic model and servo dynamic model. When get tool path as input, the digital twin process interpolation and model predictive pre-compensation control, generating the pre-compensated command to reduce modeled error. The pre-compensated command with interpolated command and other required commands are sent to the real-time controller. An online feedback control is designed to reduce the unmodeled error. Using the S-shaped curve as an example, the method proposed in this paper reduces the maximum tool tip position contour error by 77.78% and its average value by 83.90%. Similarly, the maximum tool orientation contour error is reduced by 79.05%, and its average value is reduced by 86.66%. Additionally, real-time data (axis position, axis velocity, axis current, etc.) is also transmitted to the digital twin for analyzing machining performance and updating simulation model parameters. For situations where precision requirements are not met, the digital twin can adjust the feedrate during subsequent machining to achieve an overall closed-loop optimization. In this study, a smaller proportional gain was employed to prevent system oscillation, which somewhat limited the effectiveness of online control. Future research could explore more robust online control methods. Furthermore, future work could integrate tool path planning and speed planning into the digital twin closed-loop optimization framework to further enhance performance. Meanwhile, considering cutting force during the MPCC stage can enhance contour error control during actual machining and improve machining accuracy.

Data availability

The datasets used or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Yang, J. & Altintas, Y. A generalized on-line Estimation and control of five-axis contouring errors of CNC machine tools. Int. J. Mach. Tools Manuf. 88, 9–23 (2015).

Yang, M., Yang, J. & Ding, H. A high accuracy on-line Estimation algorithm of five-axis contouring errors based on three-point Arc approximation. Int. J. Mach. Tools Manuf. 130–131, 73–84 (2018).

Chen, H. R., Cheng, M. Y., Wu, C. H. & Su, K. H. Real time parameter based contour error Estimation algorithms for free form contour following. Int. J. Mach. Tools Manuf. 102, 1–8 (2016).

Pi, S., Liu, Q. & Liu, Q. A novel dynamic contour error Estimation and control in high-speed CNC. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 96, 547–560 (2018).

Liu, Y., Wan, M., Xiao, Q. B. & Qin, X. B. Combined predictive and feedback contour error control with dynamic contour error Estimation for industrial Five-Axis machine tools. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 69, 6668–6677 (2022).

Yang, X., Seethaler, R., Zhan, C., Lu, D. & Zhao, W. A novel contouring error Estimation method for contouring control. IEEEASME Trans. Mechatron. 24, 1902–1907 (2019).

Wang, Z., Hu, C. & Zhu, Y. Accelerated iteration algorithm based contouring error Estimation for multiaxis motion control. IEEEASME Trans. Mechatron. 27, 452–462 (2022).

Li, X., Zhao, H., Zhao, X. & Ding, H. Dual sliding mode contouring control with high accuracy contour error Estimation for five-axis CNC machine tools. Int. J. Mach. Tools Manuf. 74–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmachtools.2016.05.007 (2016).

Ghaffari, A. & Ulsoy, A. G. Dynamic contour error Estimation and feedback modification for High-Precision contouring. IEEEASME Trans. Mechatron. 21, 1732–1741 (2016).

Yang, J., Zhang, H. T. & Ding, H. Contouring error control of the tool center point function for five-axis machine tools based on model predictive control. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 88, 2909–2919 (2017).

Lu, Y. et al. Research on a novel integrated control strategy for contour error compensation of biaxial CNC machining. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 130, 385–402 (2024).

Zhao, H., Zhu, L. & Ding, H. Cross-coupled controller design for triaxial motion systems based on second-order contour error Estimation. Sci. China Technol. Sci. 58, 1209–1217 (2015).

Xu, Z. et al. Intelligent contour error compensation of ultraprecision machining using hybrid Mechanism-Data-Driven model assisted with IoT framework. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inf. 20, 11815–11824 (2024).

Wang, Z., Hu, C., Zhu, Y. & Zhu, L. Prediction-Model-Based contouring error iterative precompensation scheme for precision multiaxis motion systems. IEEEASME Trans. Mechatron. 26, 2274–2284 (2021).

Yang, X., Seethaler, R., Zhan, C., Lu, D. & Zhao, W. A model predictive contouring error precompensation method. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 67, 4036–4045 (2020).

Wang, Z., Hu, C. & Zhu, Y. Dynamical model based contouring error Position-Loop feedforward control for multiaxis motion systems. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inf. 15, 4686–4695 (2019).

Pi, S., Liu, Q., Sun, P. & Tong, X. Five-axis contour error control considering milling force effects for CNC machine tools. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 98, 1655–1669 (2018).

Lyu, D., Ye, X., Zhang, H. & Liu, H. Offline fast modification of position loop gains for five-axis machining. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 127, 3951–3963 (2023).

Duong, T. Q., Rodriguez-Ayerbe, P., Lavernhe, S., Tournier, C. & Dumur, D. Contour error pre-compensation for five-axis high speed machining: offline gain adjustment approach. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 100, 3113–3125 (2019).

Kang, Z. J., Zhao, K., Li, S. & Liu, Z. Design of a real-time three-axis controller for contour error reduction based on model predictive control. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part. C J. Mech. Eng. Sci. 236, 9241–9254 (2022).

Margolis, B. W. L. & Farouki, R. T. Inverse dynamics toolpath compensation for CNC machines based on model predictive control. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 109, 2155–2172 (2020).

Wang, Y. W., Zhang, W. A., Dong, H. & Yu, L. A GESO based MPC approach to contour error control of networked motion control system. Int. J. Syst. Sci. 50, 2216–2225 (2019).

Zhang, X., Shi, T., Wang, Z., Geng, Q. & Xia, C. Generalized predictive contour control of the biaxial motion system. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 65, 8488–8497 (2018).

Zhang, L., Liu, J. & Zhuang, C. Digital twin modeling enabled machine tool intelligence: A review. Chin. J. Mech. Eng. 37, 47 (2024).

Wang, J., Niu, X., Gao, R. X., Huang, Z. & Xue, R. Digital twin-driven virtual commissioning of machine tool. Robot Comput. -Integr Manuf. 81, 102499 (2023).

Sun, X., Zhang, F., Niu, X. & Wang, J. A digital twin commissioning method for machine tools based on scenario simulation. J. Manuf. Syst. 77, 697–707 (2024).

Li, R., Zhao, L., Zhou, B. & Zhao, W. Research on machining error control method driven by Digital-twin model of dynamic characteristics of machining system. Integr. Ferroelectr. 237, 321–335 (2023).

Ward, R. et al. Machining digital twin using real-time model-based simulations and Lookahead function for closed loop machining control. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 117, 3615–3629 (2021).

Tong, X., Liu, Q., Zhou, Y. & Sun, P. A digital twin-driven cutting force adaptive control approach for milling process. J. Intell. Manuf. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10845-023-02193-2 (2023).

Kim, H. & Okwudire, C. E. Intelligent feedrate optimization using a physics-based and data-driven digital twin. CIRP Ann. 72, 325–328 (2023).

Tong, X., Liu, Q., Pi, S. & Xiao, Y. Real-time machining data application and service based on IMT digital twin. J. Intell. Manuf. 31, 1113–1132 (2020).

Lu, Y. et al. Digital Twin-driven smart manufacturing: connotation, reference model, applications and research issues. Robot Comput. -Integr Manuf. 61, 101837 (2020).

Zi, X., Gao, S. & Xie, Y. An online monitoring method of milling cutter wear condition driven by digital twin. Sci. Rep. 14, 4956 (2024).

Guo, M., Fang, X., Hu, Z. & Li, Q. Design and research of digital twin machine tool simulation and monitoring system. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 124, 4253–4268 (2023).

Sa, G. et al. A digital twin synchronous evolution method of CNC machine tools associated with dynamic and static errors. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 134, 2753–2763 (2024).

Tripura, T., Desai, A. S., Adhikari, S. & Chakraborty, S. Probabilistic machine learning based predictive and interpretable digital twin for dynamical systems. Comput. Struct. 281, 107008 (2023).

Zhang, C. et al. A multi-access edge computing enabled framework for the construction of a knowledge-sharing intelligent machine tool swarm in industry 4.0. J. Manuf. Syst. 66, 56–70 (2023).

Liu, Y., Chen, M. & Sun, Y. Global toolpath modulation–based contour error pre-compensation for multi-axis CNC machining. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 125, 3171–3189 (2023).

Huang, X. et al. Real-time estimate and control contour errors for five-axis local smoothed toolpaths based on airthoid splines. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 127, 1483–1504 (2023).

Xiao, Q. B., Wan, M., Zhang, W. H. & Yang, Y. Tool orientation optimization for the five-axis CNC machining to constrain the contour errors without interference. J. Manuf. Process. 76, 46–56 (2022).

Chen, M. Research on Feedrate Scheduling and Contour Error Pre-compensation for Five-axis Machining Based on Constrained Linear Optimization (Dalian University of Technology, 2021).

Sun, P., Liu, Q., Wang, J., Yin, Z. & Wang, L. Rotation-Angle solution and singularity handling of Five-Axis machine tools for dual NURBS interpolation. Machines 11, 281 (2023).

Wang, L. et al. Dynamic look-ahead feedrate scheduling method based on sliding mode velocity control. Sci. Rep. 14, 15424 (2024).

Tang, L. & Landers, R. G. Predictive contour control with adaptive feed rate. IEEEASME Trans. Mechatron. 17, 669–679 (2012).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.W.: conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, software, validation, original draft, review and editing; R.Y.: validation, software, review and editing; S.L.: methodology, review and editing; Z.Y.: validation, software, review and editing; S.X.: software, review and editing; Y.L.: conceptualization, supervision; Q.L.: conceptualization, supervision;

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, L., Yang, R., Lv, S. et al. Combined contour error control method for five-axis machine tools based on digital twin. Sci Rep 15, 17809 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-02047-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-02047-2