Abstract

The primary aim of this study was to analyse the influence of honeybee venom on various aspects of Drosophila melanogaster physiology and to assess the efficacy of adipokinetic hormone (AKH) in mitigating venom toxicity. We examined the harmful effects of venom on the thoracic muscles and central nervous system of Drosophila, as well as the potential use of AKH to counteract these effects. The results demonstrated that envenomation altered AKH levels in the Drosophila CNS, promoted cell metabolism, as evidenced by an increase in citrate synthase activity in muscles, and improved relative cell viability in both organs incubated in vitro. Furthermore, venom treatment reduced the activity of two key antioxidative stress enzymes, superoxide dismutase and catalase, and modified the expression of six genes encoding immune system components (Keap1, Relish, Nox, Eiger, Gadd45, and Domeless) in both organs. The venom also disrupted muscle cell ultrastructure, specifically myofibrils, and increased the release of arginine kinase into the incubation medium. Notably, when administered alongside the venom, AKH influenced the majority of these changes. AKH was the most effective in minimising damage to the ultrastructure of muscle cells and preventing the release of arginine kinase from muscles to the medium; however, in other parameters, the effect was modest or minimal. Given that honeybee venom often affects humans, understanding its actions and potential ways to reduce or eliminate them is valuable and could lead to the development of pharmacologically important compounds that may have clinical relevance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Honeybee (Apis mellifera) venom is produced in the venom gland and stored in the venom sac. Once a bee stings, the stinger is fixed in the tissue with rearward facing barbs1,2 and the venom is pumped into the victim through the venom canal by muscle movement, the activity of which is controlled by the nerve ganglion at the end of the abdomen3,4. The venom is a colourless, odourless liquid with an acidic pH (4.5 to 5.5) and contains a wide range of biologically active substances/toxins: peptides (e.g. melittin, apamin, mast cell degranulation peptide, and tertiapin), proteins (enzymes) (e.g. phospholipases, hyaluronidase, and phosphatases), biogenic amines (histamine, dopamine, noradrenaline, and serotonin), amino acids, sugars (glucose and fructose), minerals and volatile substances4,5,6.

Bee venom toxins induce a variety of physiological and biochemical reactions in the bodies of victims. These effects are compounded, increasing the overall effect of the venom, which manifests as classic injection site symptoms, such as pain, redness, swelling, and itching. This basic toxicity is caused by a cascade of events involving melittin, phospholipases, hyaluronidase, and biogenic amines. Melittin and phospholipases damage and destroy the victim’s cells by cleaving membrane phospholipids7,8, while hyaluronidase creates gaps between cells, allowing the venom to travel more quickly through tissues9. Biogenic amines (present in the venom and secreted from injured tissues) increase heart activity, which allows venom to be distributed more quickly throughout the body, increase capillary permeability (swelling), stimulate immune reactions (inflammation), and contribute to increased injection pain10,11. Other components of the venom (apamin, mast cell degranulation peptide, tertiapin, and cardiopep) support these basic effects12. Additionally, bee venom also affects the nervous13,14, muscular15, immune16 and kidney systems17,18.

Bee venom has also been documented to affect insects, including bees themselves; it makes sense, when bees first appeared on Earth (120–130 million years ago), mammals and birds were not the major animal groups19,20. Recently, the effect of bee venom was monitored using two insect model species: the American cockroach Periplaneta americana21 and the firebug Pyrrhocoris apterus22. The results revealed significant changes in body functions after envenomation including changes in the ultrastructure of thoracic muscles and levels of vitellogenin and nutrients in the haemolymph. Furthermore, venom treatment increased the levels of adipokinetic hormone (AKH) in the central nervous system (CNS) of both experimental species, indicating that this hormone plays an important role in the insect body’s protective antistress mechanism21,22. AKHs are peptide neurohormones produced in the corpora cardiaca, a small endocrine gland situated close to the insect brain. They activate antistress responses and maintain homeostasis in insects, primarily through the modulation of energy metabolism23. However, they also influence a range of accompanying activities, such as neural signalling, muscle tonus, general locomotion, heartbeat, digestive processes, immune systems, and antioxidative defence strategies24,25. AKH levels serve as an excellent marker of stress conditions in the insect body25.

In the present study, the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster was used as a model species to assess the effects of honeybee (AM) venom on an insect model. The fruit fly is a suitable species for studying hormonally controlled defence strategies against envenomation and other stressors, not only from a theoretical perspective but also for practical applications26. Further, Drome-AKH has been extensively studied. It encodes a hormone precursor that is 79 amino acids long. This precursor contains the active AKH octapeptide (pGlu-Leu-Thr-Phe-Ser-Pro-Asp-Trp-NH2)27 which is readily synthesised commercially. Although AKH is an insect hormone, recent research has demonstrated its activity in mammals. Studies have shown that AKH injections in mice enhance locomotor activity, inhibit neurodegeneration, reduce depression and anxiety, and have therapeutic potential for various nervous system disorders28,29. The activity of insect AKH in mammals can be explained by two key factors: (1) AKH signal transduction in insects is mediated by a G-protein-coupled receptor structurally related to the vertebrate gonadotropin-releasing hormone receptor—a member of receptor subgroup A30, and (2) the AKH molecule is not immunogenic when injected into a mammalian system (Kodrík, unpublished observation).

The primary goal of this study was to elucidate the defence mechanisms against AM venom poisoning using molecular, biochemical, physiological, and ultrastructural markers.

Materials and methods

Model organism and organ incubation

The stock of fruit flies, D. melanogaster (w1118 strain), was maintained on a standard cornmeal-yeast-agar medium following established Drosophila maintenance protocols (at 25 °C with a 12-h light/12-h dark cycle).

For the experiments, 7-day-old female flies were anaesthetised using CO2, collected in tubes, and kept on ice to prevent them from waking. Drosophila thoraxes (muscle tissue) were dissected in filtered Ringer’s saline solution by removing the head, abdomen, wings, legs, and viscera. Similarly, heads (CNS tissue) were prepared by removing the mouthparts, resulting in head capsules with exposed nervous tissues. The dissected tissues (either thoracic muscle or CNS tissues) were pooled together, washed in Schneider’s Insect Medium (Sigma-Aldrich, MO, USA) with 1% antibiotic mixture (10,000 U/mL penicillin – 10 mg/mL streptomycin; Sigma-Aldrich), and then used for the organ incubation process (see Sect. Organ incubation for details).

AM venom and Drome-AKH

The AM venom used in the experiments was a kind gift from Dr. J. Danihlík (Palacký University Olomouc, Czech Republic). This venom was harvested in large quantities from worker honeybees via electric stimulation. To standardise protein toxins across different venom samples, the protein content was measured using the bicinchoninic acid assay method, as described by31. Based on21, 33.3 µg venom protein equivalent per incubation well was identified as the optimal dose for testing AM venom effects in thoracic muscle or CNS tissues (see Sect. Organ incubationfor details). The corresponding venom aliquots were stored at − 80 °C until use.

The D. melanogaster AKH Drome-AKH27 was synthesised commercially by Vidia company (Praha, Czech Republic).

Organ incubation

Organ incubation was performed in a sterile flow box sanitised with 70% ethanol and UV light. Dissected thoracic muscle (5 thoraces per well) or CNS (15 heads per well) tissues were placed in fresh, sterile Schneider’s Insect Medium (Sigma-Aldrich) with a 1% antibiotic mixture (10.000 U/mL penicillin – 10 mg/mL streptomycin; Sigma-Aldrich) in a 96-well F-base cultivation plates (TPP®). The total volume per well was 125 µL. The tested substances were added as follows: Drome-AKH (25 pmol, according to32), AM venom (33.3 µg of protein equivalent), and a combination of Drome-AKH and AM venom (25 pmol + 33.3 µg of protein equivalent). These doses corresponded to 5 pmol Drome-AKH and/or 6.66 µg protein toxins, or 1.66 pmol Drome-AKH and/or 2.22 µg protein toxins per thoracic muscle or head, respectively. The control group included organs incubated in only the medium, whereas the contamination control consisted of the medium with AM venom and Drome-AKH but no tissue. Incubation was carried out at 25 °C for 24 h, after which the samples were either frozen at − 80 °C for subsequent analyses or transferred to a fixative solution for electron microscopy (see Sect. Ultrastructure observation using scanning and transmission electron microscopy for details).

Organ incubation relative viability assessment

To evaluate the relative viability of the tissues, 10 µL of alamarBlue™ Cell Viability Reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA) was added to the incubation wells during the final 3 h of organ incubation (see Sect. Organ incubation for details). After the 3-h incubation period (total of 24 h), 100 µL of the medium was collected, and the fluorescence of the resulting resorufin (λex 560 nm/λem 590 nm) was measured using a Synergy™ 4 Hybrid Microplate Reader (BioTek, VT, USA). The results were expressed as a percentage of difference from the control group (considered 100%) compared with the treated groups (AM venom, Drome-AKH, and Drome-AKH + AM venom). Medium containing AM venom and Drome-AKH without tissue was used as the blank.

Determination of Drome-AKH level in CNS (competitive ELISA)

After a 24-hour incubation, cultured heads were collected (two heads per reaction), and endogenous Drome-AKH was isolated from the CNS using 80% methanol, sonication, and centrifugation33. The supernatant containing Drome-AKH was then evaporated in a vacuum concentrator, and the resulting pellet was stored at − 80 °C until further analysis. The amount of Drome-AKH was measured using a competitive enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), following the method described by Zemanová et al.34. A known dilution series of synthetic Drome-AKH (Vidia, Prague, Czech Republic) was used as a reference to quantify the amount of Drome-AKH in the experimental samples.

Citrate synthase activity

Mitochondria were extracted from five incubated thoraces per sample (approximately 2 mg tissue; see Sect. Organ incubation for details) using ice-cold isolation buffer (250 mM sucrose, 1 mM EDTA, and 10 mM Tris-HCl; pH 7.4), followed by homogenisation and differential centrifugation at 600 × g for 10 min at 4 °C to pellet debris and nuclei and 7 000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C to pellet mitochondria. The obtained mitochondria were resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Subsequently, citrate synthase activity was measured in technical duplicates (2.5 thorax equivalent per reaction) using a Citrate Synthase Activity Assay Kit (Sigma-Aldrich) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The results were calculated using the kinetic data of the reaction.

Analysis of superoxide dismutase (SOD) and catalase (CAT) activity

After 24 h of incubation (see Sect. Organ incubation for details), 5 thoraxes (muscle tissue) or 15 heads (CNS tissue) were homogenised and sonicated in 50 mM K-PBS with 6.3 mM EDTA (pH 7). The homogenate was then centrifuged at 7000 × g for 15 min at 4 °C, and the supernatants were transferred to new tubes. SOD activity was assessed in technical duplicates using the Superoxide Dismutase Activity Assay Kit (Sigma-Aldrich) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, with a custom standard curve ranging from 200 to 0.001 U/mL of SOD (Sigma-Aldrich). CAT activity was measured in technical triplicates using the Amplex™ Red Catalase Assay Kit (Invitrogen™, Thermo Fisher Scientific) following the manufacturer’s instructions.

Measurement of immune-related gene expression using RT-qPCR

The expression of six immune-related genes (Keap1, Relish, Nox, Eiger, Gadd45, and Domeless) was monitored. After incubation, total RNA was extracted from thoracic muscles or CNS tissues (5 thoraxes or 15 heads per sample; see Sect. Organ incubation for details) via homogenisation in TriReagent solution (Sigma-Aldrich), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The isolated RNA was treated with Takara Recombinant DNase I (Clontech Laboratories Inc., CA, USA) and purified using pure ethanol and 3 M sodium acetate. The quality of the extracted, DNase-treated, and purified RNA samples was evaluated via spectrophotometry using a Take3 Microvolume Plate (BioTek). cDNA was synthesised using the iScript cDNA Synthesis Kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories, CA, USA). Quantitative real-time PCR was carried out on a QuantStudio™ 6 Flex System (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA) with the following thermal cycling conditions: an initial hot start at 95 °C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 15 s, primer annealing at 60 °C for 1 min, and extension at 72 °C for 30 s, with data acquired at the end of each extension step. Each PCR included Power SYBR™ Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems™), 10 ng cDNA, and 400 nM primers. The primer sequences for the immune-related genes were used according to35 and are provided in Table S1. After completion of the PCR, dissociation and melting curve analyses were performed. Samples were analysed in technical triplicates, and data were calculated using the 2−ΔΔCT method36. mRNA levels were normalised to those of the housekeeping gene rp4937. Relative gene expression levels in the untreated controls were set to 1. The mean values of relative gene expression in the heat maps (Fig. 7) were logarithmised and normalised to the mean value of the control.

Ultrastructure observation using scanning and transmission electron microscopy

After 24 h of organ incubation (see Sect. Organ incubation for details), thoracic muscle samples were immersed in a fixative solution containing 2.5% glutaraldehyde (electron microscopy grade) in 0.2 M PBS (pH 7.4) for 3 d at 4 °C. The samples were then washed thrice for 15 min in 0.1 M PBS with 4% glucose (pH 7.4). Next, the samples underwent post-fixation with 2% osmium tetroxide in 0.1 M PBS with 4% glucose for 2 h at room temperature to amplify ultrastructure preservation and contrast. The samples were then washed (3 × 15 min) and dehydrated using a graded series of acetone solutions ranging from 30 to 100% for 15 min each.

For scanning electron microscopy (SEM), samples in 100% acetone were dried using a critical point dryer (Ted Pella Inc., CA, USA). The dried specimens were mounted onto aluminium holders, sputter-coated with gold, and examined using an HR SEM JEOL JSM-7401 F scanning electron microscope (JEOL, Tokyo, Japan). The results were analysed using the ImageJ open-source software.

For transmission electron microscopy (TEM), acetone-dehydrated samples were infiltrated with Epon-Araldite resin (EMbed 812; Electron Microscopy Sciences, PA, USA) mixed with pure acetone at ratios of 1:2, 1:1, and 2:1 for 1 h each. The samples were then embedded overnight in pure resin under vacuum in a desiccator. Polymerisation was performed in an incubator at 62 °C for 48 h. Ultrathin Sect. (70 nm) were prepared using an Ultracut UCT microtome (Leica Biosystems, Germany) equipped with a diamond knife (Diatome Ltd., Switzerland) and were collected on Cu 300 Mesh Thin Bar grids. The sections were stained with alcoholic uranyl acetate for 30 min, followed by staining with lead citrate for 20 min. Images were captured using a 120 kV JEM-1400 Flash transmission electron microscope (JEOL) with a high-sensitivity sCMOS camera (Matataki Flash; JEOL), and the photographs were processed using the ImageJ open-source software.

Relative quantification of arginine kinase (ARK) released from muscle cells into the medium

After 24 h of incubation of the muscles, the medium in the wells of respective groups was collected (500 µL per sample) and frozen at -80 °C until use. Upon use, the stored medium samples (500 µL for each experimental group) were thawed, and the protein content was purified using Micro Spin SpeExtra MSPE C18P columns (Chromservis s.r.o., Prague) with solutions of 0.11% trifluoracetic acid (TFA), 60% methanol + 0.1% TFA, and 100% acetonitrile. The acetonitrile protein solution was then dried using a vacuum concentrator. The obtained pellet was stored at -20 °C until subsequent analysis.

The presence of ARK in the pellets and its relative amounts were determined using western blotting. The samples were dissolved in PBS with NuPAGE® LDS Sample Buffer (Invitrogen™, Thermo Fisher Scientific) and freshly added 1 M dithiotreithol (Thermo Fisher Scientific), followed by heating to 80 °C for 10 min and a brief frost-shock. Thereafter, lithium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (LDS-PAGE) was performed under reducing conditions using Mini-PROTEAN TGX Stain-Free Gels (Bio-Rad Laboratories) and PageRuler Plus Pre-stained Protein Ladder (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Then, the presence of the separated proteins was confirmed using Bio-Rad stain-free gel technology. The proteins were transferred onto a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane using a tank transfer system with borate buffer containing 10% methanol. Afterwards, the membrane was blocked overnight in TBST (Tris-buffered saline + 0.1% Tween 20) + 5% bovine serum albumin (fraction V) + 5% skim milk solution. The following day, the membrane was incubated with primary ARK Polyclonal Antibody (Thermo Fisher Scientific) (diluted 1:1000 in TBST) for 2 h, followed by washing with TBST (4 × 5 min). Subsequently, the membrane was incubated with Goat anti-Rabbit IgG (H + L) Secondary Antibody, HRP (diluted 1:100 000 in TBST) for 1 h and then washed with TBST (4 × 5 min). ARK bands were visualised on the ChemiDoc™ MP Imaging System (Bio-Rad Laboratories) using a chemiluminescent Clarity™ Western ECL Substrate (Bio-Rad Laboratories). The signal had an exposure time of 500 s (50 s/snapshot). The results were analysed using Image Lab Software 6.1 (Bio-Rad Laboratories).¨.

Statistical analysis of data

Data analyses were conducted using the Prism 8.0.1 software (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). Bar graphs display the mean ± standard deviation, with the number of replicates (n) indicated in the figure legends. Initially, outliers in the datasets were identified using the 1.5 × interquartile range method. The Shapiro–Wilk test was used to assess the normal distribution of the data. Statistical differences were analysed using unpaired Student t-test (Fig. 1), one-way analysis of variance with Tukey’s post-hoc test (Figs. 2, 3, 4 and 10B) and the one-way analysis of variance with Dunnett’s post-hoc test (Figs. 5 and 6), which was applied because of the focus on the evaluation of upregulation and downregulation trends while correcting for multiple comparisons. Figures 8 and 9 were processed using the ImageJ open-source software. Figure 10A was analysed using Image Lab Software 6.1 (Bio-Rad Laboratories) and contrasted using ImageJ open-source software.

Level of endogenous Drome-AKH in CNS of 7-day-old females D. melanogaster after 24 h incubation in the presence of AM venom; the data are expressed per one organ. Statistically significant differences between the groups (mean ± SD, n = 8) are assessed by unpaired Student t-test at the 0.1% level and indicated by ***. The number above the AM column represents fold-difference in comparison to the control group.

Relative viability assay expressed as a percentage of the difference between untreated control and treated groups (Drome-AKH, AM venom, and AM venom + Drome-AKH) in the thoracic muscle (A) and CNS (B) tissue of 7-day-old females D. melanogaster after 24 h incubation. Statistically significant differences among the groups (mean ± SD, n = 7–12) are assessed by one-way ANOVA with Tukey post-test at the 5% level and are indicated by different letters above the columns (a, b, c, d). The numbers above the columns represent fold-difference in comparison to the control group.

Citrate synthase activity in thoracic muscle of 7-day-old females D. melanogaster after 24 h incubation in the following tested groups: control, Drome-AKH, AM venom, and AM venom + Drome-AKH. Statistically significant differences among the groups (mean ± SD, n = 4–5) are assessed by one-way ANOVA with Tukey post-test at the 5% level and are indicated by different letters above the columns (a, b, c). The numbers above the columns represent fold-difference in comparison to the control group.

Level of oxidative stress markers – superoxide dismutase (A, C) and catalase (B, D) in thoracic muscles (A, B) and CNS (C, D) of 7-day-old females D. melanogaster after 24 h incubation in the following tested groups: control, Drome-AKH, AM venom, and AM venom + Drome-AKH. The enzyme activity in thoracic muscles is expressed per mg of tissues, in CNS per organ. Statistically significant differences among the groups (mean ± SD, n = 4–5 (A, B), n = 6–8 (C, D)) are assessed by one-way ANOVA with Tukey post-test at the 5% level and are indicated by different letters above the columns (a, b, c). The numbers above the columns represent fold-difference in comparison to the control group.

Relative gene expression of Keap1 (A), Relish (B), Nox (C), Eiger (D), Gadd45 (E), and Domeless (F) in thoracic muscles of 7-day-old females D. melanogaster after 24 h incubation in the following tested groups: control, Drome-AKH, AM venom, and AM venom + Drome-AKH. Statistically significant differences to the control group (mean ± SD, n = 5–13) are assessed by one-way ANOVA, followed by Dunnett’s post-hoc test and indicated by asterisks above zig-zag lines (*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001). The numbers above the columns represent fold-difference in comparison to the control group.

Relative gene expression of Keap1 (A), Relish (B), Nox (C), Eiger (D), Gadd45 (E), and Domeless (F) in CNS of 7-day-old females D. melanogaster after 24 h incubation in the following tested groups: control, Drome-AKH, AM venom, and AM venom + Drome-AKH. Statistically significant differences to the control group (mean ± SD, n = 5–12) are assessed by one-way ANOVA, followed by Dunnett’s post-hoc test and indicated by asterisks above zig-zag lines (*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001). The numbers above the columns represent fold-difference in comparison to the control group.

Results

The experimental phase of the study began with the determination of Drome-AKH levels in the CNS of 7-day-old Drosophila females incubated in vitro for 24 h. The application of AM venom was found to cause a significant 3.5-fold reduction in hormone levels (Fig. 1). In the next experiments, the relative viability of the incubated organs was evaluated (Fig. 2). Both thoracic muscle (Fig. 2A) and CNS (Fig. 2B) tissues showed significant increases in relative viability after all treatments compared with the control group (medium only): Drome-AKH (in graphs abbreviated to AKH), AM venom, and Drome-AKH + AM venom co-treatment. Drome-AKH increased the relative viability 1.3 times in both incubated organs. Interestingly, incubation with AM venom increased the relative viability by 2.9-fold (Fig. 2A) and 1.7-fold (Fig. 2B) in the thoracic muscle and CNS tissues, respectively. When AM venom was applied together with Drome-AKH, the most pronounced effects were observed, with a 3.6-fold increase in thoracic muscle and a 1.9-fold increase in CNS compared with the control. Compared with venom alone, the increase was only significant in the thoracic muscle (Fig. 2A).

Additionally, citrate synthase activity was analysed in the thoracic muscles (Fig. 3). This enzyme, belonging to the acyltransferase group, catalyses the first reaction of the Krebs cycle, in which acetyl coenzyme A condenses with oxaloacetate to form citrate and coenzyme A38. Thus, Drome-AKH or its combination with AM venom had no or a small but significant effect, respectively, whereas AM venom alone significantly increased citrate synthase activity by 1.5-fold compared with the control. No significant difference was observed between the venom and AKH + venom groups.

The superoxide dismutase (SOD) and catalase (CAT) play a crucial role in protecting against oxidative stress. These enzymes scavenge free radicals: SOD converts the superoxide anion radical (O2−•) to hydrogen peroxide, while CAT transforms hydrogen peroxide into water and oxygen39,40. Accordingly, SOD (Fig. 4A and C) and CAT (Fig. 4B and D) in the thoracic muscle (Fig. 4A and B) and CNS (Fig. 4C and D) tissues exhibited severely decreased activities following AM venom intoxication. As expected, Drome-AKH administered alone had no significant effect on any of the tested tissues or oxidative stress markers, and when the venom was combined with AKH, the inhibitory effect of the venom remained unchanged.

Relative immune-related gene expression analysis in the muscle tissue (Fig. 5) demonstrated that Drome-AKH treatment downregulated all analysed genes, however, just Relish (Fig. 5B) was significantly downregulated, whereas the others did not show significant changes in expression. In terms of the AM venom effect, Keap1, Relish, Nox, and Eiger (Fig. 5A, B, C, and D) were significantly upregulated, and Gadd45 and Domeless (Fig. 5E and F) were only marginally affected. Finally, administration of AM venom with Drome-AKH resulted in significant upregulation of all immune-related genes studied (Fig. 5A–F).

Analysis of the expression of the same genes in the CNS (Fig. 6) yielded interesting results. Overall, Drome-AKH treatment showed similar results to those in the muscle tissue. Thus, the majority of the analysed genes, namely Keap1, Relish, Gadd45, and Domeless, were downregulated although not significantly (Fig. 6A, B, E, and F), with the exception of the significantly downregulated Eiger (Fig. 6D) and slightly upregulated Nox (Fig. 6C). Interestingly, the AM venom-treated group showed contrasting outcomes. Keap1, Relish, Eiger, Gadd45, and Domeless (Fig. 6A–F) were notably downregulated, whereas only Nox (Fig. 6C) was upregulated although not significantly. Genes affected by the co-administration of AM venom and Drome-AKH were mainly downregulated, either significantly (Keap1, Eiger, and Domeless [Fig. 6A, D, F]) or not significantly (Relish and Gadd45 [Fig. 6B, E]), and Nox (Fig. 6C) was significantly upregulated.

All data used to analyse the gene expression of immune response markers in the thoracic muscle and CNS tissues, as described in the previous two paragraphs, are summarised in Fig. 7.

Heat maps summarizing the relative gene expression of studied genes in thoracic muscles (A), see Fig. 5) and CNS (B), see Fig. 6) tissue. Mean values of determined relative gene expressions were logarithmized and normalized to control. Color coding of the squares in comparison to the control group – white = basal gene expression, spectrum of red = up-regulation, and spectrum of blue = down-regulation. For statistic details see Figs. 5 and 6.

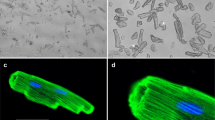

In addition to biochemical and molecular assays, SEM (Fig. 8) and TEM (Fig. 9) were employed to study the AM envenomation effect on muscle tissue at the (ultra)structural level. The data obtained indicated that the muscles treated with AM venom exhibited significant (ultra)structural changes (Figs. 8C and 9C), resulting in a structure different from that of the control group (Figs. 8A and 9A). In particular, the membrane and myofibril structures were damaged and disintegrated following venom administration. Although the Z-discs of myofibrils, where actin filaments are anchored, appeared to have suffered only minor damage, the central parts of the sarcomeres, composed of heavy meromyosin and actin filaments, were severely disrupted (Fig. 9C). Envenomation also caused an increase in vacuolisation, with vacuoles forming inside myofibrils (Fig. 9C), whereas in the controls (Fig. 9A), a significantly smaller number of vacuoles was observed just outside the myofibrils. This demonstrates the venom’s overall disintegrative effect on the ultrastructure of muscle cells. Interestingly, the co-administration of Drome-AKH and AM venom (Figs. 8D and 9D) restored the myofibril structure to a state similar to that of the control group. As expected, Drome-AKH treatment alone (Figs. 8B and 9B) resulted in no significant changes.

TEM photos of thoracic muscles from 7-day-old females D. melanogaster after 24 h incubation in (A) only medium (control), (B) Drome-AKH, (C) AM venom, and (D) AM venom + drome-AKH. mf myofibril, mt mitochondria, tr trachea. Green arrowheads pointing to Z lines define the sarcomere; blue arrowheads point to the vacuole. Scale bars in the Figs = 2 μm.

To support the SEM and TEM observations, the levels of ARK in the medium containing incubated muscle tissue were examined. ARK is an important enzyme in energy metabolism, catalysing a reaction between ATP and L-arginine. It occurs predominantly in invertebrates41 but is also present in eukaryotes generally42. The multichannel photograph of the western blot (Fig. 10A) and the graph of the processed data (Fig. 10B) show that the medium containing AM venom-treated thoracic muscles had the significantly highest relative ARK level. In contrast, the relative ARK levels in the other groups were comparable.

Relative arginine kinase (ARK; m.w. = 40 kDa) amount released into the medium from thoracic muscles of 7-day-old females D. melanogaster after 24 h incubation in the following tested groups: control, Drome-AKH, AM venom, and AM venom + Drome-AKH. (A) Multichannel photo of western-blotted membrane; green colour = ladder (colorimetric) and red colour = ARK in tested groups (chemiluminometric). (B) Graph quantifying the ARK bands from 3 independent western-blotted membranes. Statistically significant differences among the groups (mean ± SD, n = 3) are assessed by one-way ANOVA with Tukey post-test at the 5% level and are indicated by different letters above the columns (a, b). The numbers above the columns represent fold-difference in comparison to the control group.

Discussion

The toxicological properties of AM venom have been studied extensively over the last several decades43,44,45; however, some details of its molecular and biochemical mechanisms remain to be elucidated. The majority of relevant experiments were performed on mammalian models; however, our recent studies have revealed that insect models offer an interesting alternative21,22. This idea is not entirely novel, as research on the effects of bee venom or its fractions in Drosophila was conducted more than 50 years ago46,47. The possibility of model variability can be explained by the universal mechanisms of the main bee venom toxins. This is primarily due to melittin and its ability to bind to the phospholipid bilayer of cell membranes to form pores and activate various enzymes. Consequently, melittin-activated phospholipases break down cell membrane phospholipids, resulting in cell destruction6,7 and mitochondrial damage and collapse47,48. Melittin is a multitoxic peptide that affects several organ systems, including the cardiovascular, immune, and neural systems49. Although melittin is known bind to the myosin light chain and elicit myonecrosis/rhabdomyolysis in both vertebrates15,50,51 and insects21, its effect on the muscular system is not well studied. Therefore, we investigated the interactions of bee venom primarily with the muscular system in the universal insect model D. melanogaster, as well as the effect of bee venom on the CNS since the muscular system is closely associated with the neural system.

Effect of the honeybee venom on AKH level, metabolic characteristics and oxidative stress

The findings of the present study indicated that AM venom significantly reduced the level of Drome-AKH in the CNS incubated in vitro. As AKH is a characteristic anti-stress hormone, this result appears unexpected, particularly given that the injection of AM venom into the bodies of P. americana21 or P. apterus22 resulted in an increase in AKH in the CNS. Nonetheless, AKH activity is likely to be more complex when an insect is envenomated, and the reaction may be species-specific or differ between in vivo and in vitro conditions. Similarly to this study, venom from the wasp Habrobracon hebetor reduced the level of AKH in Drosophila CNS in vitro35. Drome-AKH is probably released into the medium; however, we are unable to confirm this at present, as the concentration of AKH in the medium is quite low, and AKH may be degraded by AM venom activity. The absence of internal organs under in vitro conditions, and thus the lack of positive feedback from them, may also affect AKH levels in the CNS.

Further, both Drome-AKH and AM venom treatment enhanced the relative cell viability in the thoracic muscle and CNS tissues. This may appear surprising at first glance, particularly for AM venom, but this can be explained by the results of the alamarBlue® test conducted. The essence of this test (see Sect. Organ incubation relative viability assessment for details) is the conversion of resazurin to resorufin and the evaluation of the electron transport chain in oxidative processes. This generally assesses the intensity of cellular metabolism. As a result, tissue envenomation triggers antistress defence mechanisms associated with increased metabolism. This reaction was found to be lower in the CNS than in muscles, which are more metabolically active organs. Administration of Drome-AKH resulted in a significant increase in metabolism, which is not surprising given the role of AKHs in mobilising energy resources, increasing metabolism, and maintaining homeostasis23,25. The combination of both substances resulted in no significant alterations, except in the muscles, wherein metabolism significantly increased although not exceptionally.

The positive effect of AM on the viability and metabolism of muscle cells was supported by the citrate synthase data. Administration of AM venom significantly increased the activity of this enzyme that play a substantial role in energy metabolism38; however, the effect of AKH alone or in combination with the venom was minimal to none. Moreover, citrate synthase activity is regulated by various factors. Metformin, an antidiabetic drug, increases citrate synthase activity in rat muscles52, thyroid hormone levels in the liver of whitefish (Coregonus clupeaformis)53, and insulin levels in the human body54. To the best of our knowledge, no data are available on the direct stimulation of citrate synthase in insects following the administration of any substance. Thus, our discovery of this enzyme activation by bee venom appears to be novel. Nonetheless, this finding is consistent with the enzyme’s broad functions in animal immunological defence. Citrate synthase is known to exert an antibacterial effect55, play a role in general immune metabolism56, and have other immunological functions57.

Many venoms and toxins have been shown to trigger oxidative stress when reactive oxygen species production exceeds the capacity of antioxidative systems. This may substantially disrupt key biochemical and physiological processes by destroying physiologically active molecules, such as nucleic acids, proteins, or lipids58. The present study demonstrated that AM venom significantly reduced the activity of two key antioxidant enzymes, SOD and CAT, which play a crucial role in protecting organisms from oxidative stress59. Our findings of the AM venom suppression of oxidative stress enzymes and almost no effect of AKH may have two causes: (1) venom treatment reduces oxidative stress, resulting in decreased enzyme activity; and (2) venom treatment enhances oxidative stress and selectively eliminates enzyme activity via mechanisms such as protein carbonylation of the enzyme molecules. In addition, co-administration of AKH and oxidative stressors is known to reduce stress-induced changes in the activity of antioxidative enzymes60,61,62,63. However, this was not found in the present study, which might point to the novel possibility of the above-mentioned explanation of the AKH vs. enzyme results: the reduction of oxidative stress. This conclusion is corroborated by studies on mammals64,65,66, which established the antioxidative activity of AM venom and/or its toxins. It is also indirectly supported by the stimulatory effect on citrate synthase activity (discussed above), as citrate synthase activity is negatively correlated with antioxidative enzymes67. The failure of venom to generate oxidative stress was also observed in the cockroach P. americana21. Meanwhile, reduction of SOD and CAT activities elicited by Drosophila envenomation by administration of venom from a braconid wasp H. hebetor was partially eliminated by co-administration with AKH35.

Immune responsible factors in thoracic muscles and the CNS

The expression levels of genes linked to the immune response in the thoracic muscles showed a distinct response to the toxicity of venom alone or with AKH. The expression levels of Keap1, Relish, Nox, Eiger, Gadd45, and Domeless were examined after treatment with AM venom alone, AKH alone, or venom + AKH. The products of these genes play important roles in the Drosophila immune system. Keap1 is an inhibitor of NF-E2-related factor 2 (Nrf2), a transcription factor from the leucine zipper family. Keap1/Nrf2 signalling regulates cellular responses to electrophilic xenobiotics and to oxidative stress68. Relish (encoding analogue of nuclear factor kappa B) plays a significant role in inducing the humoral innate immune response in Drosophila via activation of Imd pathway, which involves antifungal, antibacterial, and possible antivenom factors69,70. Nox is involved in the regulation of muscle contraction, Ca2+ signalling, and modulation of reactive oxygen species. Eiger (analogue of tumour necrosis factor alpha) can induce cell death and functions as a physiological ligand for the c-Jun kinase (JNK) pathway71. Gadd45 is a component of the JNK signalling pathway and is involved in cell senescence, DNA repair, and apoptosis. It can be activated as a cellular response to various nongenotoxic and genotoxic substances71,72. Domeless encodes a transmembrane receptor, which is crucial to the Janus kinase (JAK)/signal transducers and activators of transcription (STAT) signalling cascade in response to cytokines73. Treatment with honeybee venom increased the expression of the Keap1, Relish, Nox and Eiger genes in the thoracic muscles. Thus, hypothetically, an increase in Keap1 expression indicates a decrease in the antioxidant response. Among the signalling pathways susceptible to target-specific reactive electrophile species and reactive oxygen species (ROS) regulation—such as those involved in immune response, DNA damage, apoptosis, and transcription—the Keap1/Nrf2 pathway is one of the most evolutionarily conserved. In its simplest form, Nrf2 is a transcription factor that upregulates cytoprotective genes essential for safeguarding against numerous reactive molecules, while Keap1 is its inhibitor. However, under conditions where cellular stresses overwhelm the defence system, Keap1 expression may be augmented, thereby inhibiting Nrf2 expression74. We hypothesise that a similar mechanism could be at play in thoracic muscles exposed to AM venom. Additionally, the relative expression of Keap1 corresponded with SOD and CAT activity observed in this study. In muscle tissue, Keap1 was upregulated, which may have caused a decrease in SOD and CAT activity, whereas in the CNS, the opposite pattern was observed. Further, increased Relish gene expression should indicate a defense anti-toxic reaction, as similar increases in this gene expression were observed when the locust Locusta migratoria was treated with Bacillus thuringiensis toxins75 or the beetle Octodonta nipae was infected with various nematodes or their bacteria76. Changes in the levels of the other gene expressions are rather unclear, and any conceivable explanation would be speculative.

In conclusion, assessing the impact of a complex xenobiotic such as honeybee venom on immune-related genes is challenging. According to the literature, various substances have documented immunotoxic effects in insect species. Moreover, the immune response, including the up- or down-regulation of immune-related genes, is species-, tissue-, and dose-dependent (for details, see77,78). Furthermore, the immune system is closely linked to ROS production, either directly (through pathogen/toxin neutralisation) or indirectly (via cell signalling), meaning they can influence each other79. Accordingly, the immunotoxic effects of honeybee venom require further investigation.

Interestingly, the stimulatory effect was maximal when the venom was combined with Drome-AKH; nevertheless, the hormone alone had mostly no effect, with the exception of Relish, where certain inhibition was observed. However, this is not surprising as the role of AKH is known to be mostly realised only when a stressor is present; when a stressor is missing, AKH action is featureless or nonexistent. For instance, applying AKH to the cotton leafworm Spodoptera littoralis or the firebug P. apterus eliminated oxidative stress caused by treatments with tannic acid or hydrogen peroxide, respectively, whereas AKH by itself had no direct effect61. Other examples of this were documented when AKH was co-applied with insecticides25.

Studies have revealed that the effects of venom on gene expression in the CNS is mostly opposite to that in muscles. Venom treatment resulted in significant (Keap1, Relish, Eiger, Domeless) or non-significant (Gadd45) downregulation, with the exception of Nox, which was marginally up-regulated. The application of AKH alone resulted in a slight but mainly nonsignificant decrease in gene expression.

To summarise, a distinct tissue-specific response in immunomodulatory genes was observed upon AM venom treatment and co-application of AKH. Envenomation of thoracic muscles increased the expression of a suite of genes while inhibiting them in the CNS, suggesting a tissue-specific reaction. In both systems, AKH could at least partially alter this effect. There are currently no satisfactory explanations for the differences between muscles and the CNS. Notably, recent research on the venom of the wasp H. hebetor in a comparable Drosophila system revealed no distinction in immune gene expression between the CNS and muscles; in both cases, envenomation resulted in the downregulation of the target genes35. The distinct modes of action of the two venoms could be a possible explanation for this variation. In contrast to bee venom, wasp venom causes complete muscle paralysis, rendering the victim immobile and further suppressing both cellular and humoral immunity80,81,82. Nonetheless, additional research is required to understand the differing characteristics of the two venoms.

Ultrastructure of thoracic muscles and ARK activity

Although the muscles do not appear to be the major target of AM venom, some venom toxins can impair muscle structure and function. The major toxin melittin binds to the myosin light chain and influences its action50. Experimental treatment with melittin causes disruption and disorganisation of human skeletal muscles in cell culture83 and mouse skeletal muscle myofibrils84. Additionally, AM venom was reported to cause skeletal muscle spasm in a mouse model85, likely through the disruption of sarcoplasmic reticulum and vast release of calcium ions. Interestingly, results documenting the negative effect of AM venom on muscles have also been recorded in insects, wherein venom administration to the cockroach P. americana resulted in severe damage to the muscle ultrastructure, with the organisation of myofibrils being the primary target21. The findings of this research support the results of the present study; envenomation of the Drosophila thoracic muscles resulted in significant damage to the myofibril ultrastructure, which appeared to be disintegrated. Overall, it is well-established that bee venom contains a variety of enzymes, including those with proteolytic activity86. Thus, it is possible that the activity of these enzymes led to the digestion of the actin and myosin molecular structures, thereby causing damage to their striated structure. Further, the muscle appeared to be in tension (spasm), whereas mitochondria did not appear to be damaged. This conclusion was supported by the citrate synthase data, which revealed the maximum activity of this mitochondrial enzyme in the venom-treated Drosophila group. In addition, the overall effect of the venom on muscle cells is also demonstrated by the results of ARK analysis (this study)—the increase in the release of ARK from AM venom-treated muscles in vitro indicates damage to the muscle cell membrane and, consequently, an increased release of ARK into the medium (ARK is primarily located in the cytoplasm)87. Interestingly, a test based on similar findings is utilised in medicine, in which the ARK homologue creatine kinase serves as a marker of stroke, heart attack, and/or rhabdomyolysis88,89. In general, ARK regulates cellular ATP levels, making it an important enzyme in invertebrate energy metabolism90; it is typically found in muscles91 and has strong allergic properties [92,93]. Notably, in a related experiment using D. melanogaster muscles, the venom from H. hebetor destroyed the mitochondrial structure35, in contrast to the AM venom which primarily targeted myofibrils.

Interestingly, all the above-mentioned ultrastructural alterations, such as deleterious structural changes in thoracic muscles after AM venom treatment (this study) as well as after Habrobracon venom treatment35 and reduced ARK levels in the incubation medium (this study), were mitigated or abolished by co-administration with AKH. The mechanism of AKH activity is unknown; however, it is consistent with known AKH activities that maintain homeostasis25.

In conclusion, this study found that administration of honeybee A. mellifera venom into a medium in which Drosophila thoracic muscle or CNS tissues are incubated resulted in significant physiological, biochemical, and structural alterations in the examined organs. The treatment reduced AKH level in Drosophila CNS, increased metabolism, as evidenced by increased cell viability in both organs and increased citrate synthase activity in thoracic cells. Envenomation also influenced oxidative stress; it decreased SOD and CAT activity in both the thoracic muscle and CNS tissues. The effect of venom on immune gene expression was variable: in the thoracic muscles, it either raised the expression or had no effect, whereas in the CNS, it mostly resulted in downregulation (except for Nox). The venom also damaged the ultrastructure of muscle cells, specifically myofibril organisation, and increased the levels of ARK released in the incubation medium. Most of the indicated changes were modified by Drome-AKH when co-administered with venom. The greatest impact was observed in the cell ultrastructure which was mitigated, and a significant suppression of ARK release was observed; in other parameters, the hormonal effect was moderate or minimal. The mutual interactions between bee venom and AKH in the victims’ bodies appear to be challenging; however, any investigation of pharmacologically important compounds with a venom-protective function is worth examining for theoretical and practical reasons in the future.

Data availability

Any data of the MS are available on request. Contact the corresponding author: Dalibor Kodrík - E-mail: kodrik@entu.cas.cz.

Change history

12 January 2026

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33452-2

Abbreviations

- AM venom:

-

Apis mellifera venom

- ANOVA:

-

Analysis of variance

- ARK:

-

Arginine kinase

- CAT:

-

Catalase

- CNS:

-

Central nervous system

- CPD:

-

Critical point dryer

- CS:

-

Citrate synthase

- Drome-AKH:

-

Drosophila melanogaster adipokinetic hormone

- ELISA :

-

Enzyme linked immunosorbent assay

- JNK:

-

c-Jun-Kinase

- Keap1:

-

Kelch like ECH-associated protein 1

- Nox:

-

NADPH oxidase

- Nrf2:

-

NF-E2-related factor 2

- SEM:

-

Scanning electron microscope

- SOD:

-

Superoxide dismutase

- TEM:

-

Transmission electron microscope

References

Weyda, F. & Kodrík, D. New functionally ultrastructural details of honey bee stinger tip: serrated edge and pitted surface. J. Apicult Res. 60, 875–878 (2021).

Černý, J., Weyda, F., Perlík, M. & Kodrík, D. Functional ultrastructure of hymenopteran stingers: devastating spear or delicate syringe. Microsc Microanal. 28, 1808–1818 (2022).

Snodgrass, R. E. Anatomy and Physiology of the Honeybee 1st edn (McGraw-Hill Book Company, 1925).

Bogdanov, S. Bee Venom: Production, Composition, Quality. 1. The Bee Venom Book (Muehlethurnen, 2016).

Moreno, M. & Girald, E. Three valuable peptides from bee and Wasp venoms for therapeutic and biotechnological use: Melittin, Apamin and mastoparan. Toxins 7, 1126–1150 (2015).

Lubawy, J. et al. The influence of bee venom Melittin on the functioning of the immune system and the contractile activity of the insect heart - a preliminary study. Toxins 11, 494 (2019).

Chen, J. & Lariviere, W. R. The nociceptive and anti-nociceptive effects of bee venom injection and therapy: A double-edged sword. Prog Neurobiol. 92, 151–183 (2010).

Lee, M. T., Sun, T. L., Hung, W. C. & Huang, H. W. Process of inducing pores in membranes by melittin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 14243–14248 (2013).

Vetter, R. S., Visscher, P. K. & Camazine, S. Mass envenomations by honey bees and wasps. West. J. Med. 170, 223–227 (1999).

Ziai, M. R., Russek, S., Wang, H. C., Beer, B. & Blume, A. J. Mast cell degranulating peptide: a multi-functional neurotoxin. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 42, 457–461 (1990).

França, F. O. et al. Severe and fatal mass attacks by killer bees (Africanized honey bees-Apis mellifera scutellata) in Brazil: clinicopathological studies with measurement of serum venom concentrations. Q. J. Med. 87, 269–282 (1994).

Khalil, A., Elesawy, B. H., Ali, T. M. & Ahmed, O. M. Bee Venom: from venom to drug. Molecules 26, 4941 (2021).

Lamy, C. et al. Allosteric block of KCa2 channels by Apamin. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 27067–27077 (2010).

Teshima, K., Kim, S. H. & Allen, C. N. Characterization of an apamin-sensitive potassium current in Suprachiasmatic nucleus neurons. Neuroscience 120, 65–73 (2003).

Betten, D. P., Richardson, W. H., Tong, T. C. & Clark, R. F. Massive honey bee envenomation-induced rhabdomyolysis in an adolescent. Pediatrics 117, 231–235 (2006).

Moolenaar, W. H. Bioactive lysophospholipids and their G protein-coupled receptors. Exp. Cell. Res. 253, 230–238 (1999).

Grisotto, L. S. D. et al. Mechanisms of bee venom-induced acute renal failure. Toxicon 48, 44–54 (2006).

Honda, N. et al. Acute renal failure and rhabdomyolysis. Kidney Int. 23, 888–898 (1983).

Culliney, T. W. Geological history and evolution of the honey bee. Am. Bee J. 123, 580–585 (1983).

Engel, M. S. Fossil honey bees and evolution in the genus Apis (Hymenoptera: Apidae). Apidologie 29, 265–281 (1998).

Bodláková, K. et al. Insect body defence reactions against bee venom: do adipokinetic hormones play a role? Toxins 14, 11 (2022).

Ondřichová, A. et al. Physiological responses to honeybee venom poisoning in a model organism, the firebug Pyrrhocoris apterus. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. C. 270, 109657 (2023).

Gäde, G., Hoffmann, K. H. & Spring, J. H. Hormonal regulation in insects: facts, gaps, and future directions. Physiol. Rev. 77, 963–1032 (1997).

Kodrík, D. Adipokinetic hormone functions that are not associated with insect flight. Physiol. Entomol. 33, 171–180 (2008).

Kodrík, D., Bednářová, A., Zemanová, M. & Krishnan, N. Hormonal regulation of response to oxidative stress in insects - an update. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 16, 25788–25816 (2015).

Gáliková, M., Klepsatel, P., Xu, Y. J. & Kühnlein, R. P. The obesity-related adipokinetic hormone controls feeding and expression of neuropeptide regulators of Drosophila metabolism. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 119, 1600138 (2017).

Schaffer, M. H., Noyes, B. E., Slaughter, C. A., Thorne, G. C. & Gaskell, S. J. The fruitfly Drosophila melanogaster contains a novel charged adipokinetic hormone-family peptide. Biochem. J. 269, 315–320 (1990).

Mutlu, O. et al. Effects of adipokinetic hormone/red pigment-concentrating hormone family of peptides in olfactory bulbectomy model and posttraumatic stress disorder model of rats. Peptides 134, 170408 (2020).

Mutlu, O. et al. Effects of the adipokinetic hormone/red pigment-concentrating hormone (AKH/RPCH) family of peptides on MK-801-induced schizophrenia models. Fundam Clin. Pharmacol. 32, 589–602 (2018).

Gäde, G. & Auerswald, L. Mode of action of neuropeptides from the adipokinetic hormone family. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 132, 10–20 (2003).

Stoscheck, C. M. Quantitation of protein. In Methods in enzymology, 182, 50–68. Academic (1990).

Ibrahim, E., Dobeš, P., Kunc, M., Hyršl, P. & Kodrík, D. Adipokinetic hormone and adenosine interfere with nematobacterial infection and locomotion in Drosophila melanogaster. J. Insect Physiol. 107, 167–174 (2018).

Goldsworthy, G. J. A quantitative study of the adipokinetic hormone of the firebug, Pyrrhocoris apterus. J. Insect Physiol. 48, 1103–1108 (2002).

Zemanová, M., Stašková, T. & Kodrík, D. Role of adipokinetic hormone and adenosin in the anti-stress response in Drosophila melanogaster. J. Insect Physiol. 91, 39–47 (2016).

Černý, J., Krishnan, N., Hejníková, M., Štěrbová, H. & Kodrík, D. Modulation of response to braconid Wasp venom by adipokinetic hormone in Drosophila melanogaster. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. C. 285, 110005 (2024).

Livak, K. J. & Schmittgen, T. D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2 – ∆∆CT method. Methods 25, 402–408 (2001).

Hanna, M. E. et al. Perturbations in dopamine synthesis lead to discrete physiological effects and impact oxidative stress response in Drosophila. J. Insect Physiol. 73, 11–19 (2015).

Wiegand, G. & Remington, S. J. Citrate synthase: structure, control, and mechanism. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biophys. Chem. 15, 97–117 (1986).

Mendis, E., Rajapakse, N. & Kim, S. K. Antioxidant properties of a radical-scavenging peptide purified from enzymatically prepared fish skin gelatin hydrolysate. J. Agric. Food Chem. 53, 581–587 (2005).

Burlakova, E. B. et al. Biomarkers of oxidative stress and smoking in cancer patients. J. Cancer Res. Ther. 6, 47–53 (2010).

Suzuki, T., Yamamoto, Y. & Umekawa, M. Stichopus japonicus arginine kinase:: gene structure and unique substrate recognition system. Biochem. J. 351, 579–585

Wakim, B. T. & Aswad, G. D. Ca(2+)-calmodulin-dependent phosphorylation of arginine in histone 3 by a nuclear kinase from mouse leukemia cells. J. Biol. Chem. 269, 2722–2727 (1994).

Haberman, E. Chemical structure and biological action of components of bee venom. Angew Chem. Int. Ed. 12, 83–84 (1973).

Isidorov, V., Zalewski, A., Zambrowski, G. & Swiecicka, I. Chemical composition and antimicrobial properties of honey bee venom. Molecules 28, 4135 (2023).

Gajski, G., Leonova, E. & Sjakste, N. Bee Venom: composition and anticancer properties. Toxins 16, 117 (2024).

Lowy, P. H., Sarmiento, L. & Mitchell, H. K. Polypeptides minimine and Melittin from bee venom - effects on Drosophila. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 145, 338–343 (1971).

Mitchell, H. K., Lowy, P. H., Sarmiento, L. & Dickson, L. Melittin - toxicity to Drosophila and Inhibition of acetylcholinesterase. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 145, 344–348 (1971).

Florea, A., Varga, A. P. & Matei, H. V. Ultrastructural variability of mitochondrial Cristae induced in vitro by bee (Apis mellifera) venom and its derivatives, Melittin and phospholipase A2, in isolated rat adrenocortical mitochondria. Micron 112, 42–54 (2018).

Pucca, M. B. et al. Bee updated: current knowledge on bee venom and bee envenoming therapy. Front. Immunol. 10, 2090 (2019).

Malencik, D. A. & Anderson, S. R. Association of Melittin with isolated myosin light-chain. Biochemistry 27, 1941–1949 (1988).

Florea, A. & Craciun, C. Bee (Apis mellifera) venom produced toxic effects of higher amplitude in rat thoracic aorta than in skeletal muscle—An ultrastructural study. Microsc Microanal. 18, 304–316 (2012).

Suwa, M., Egashira, T., Nakano, H., Sasaki, H. & Kumagai, S. Metformin increases the PGC-1alpha protein and oxidative enzyme activities possibly via AMPK phosphorylation in skeletal muscle in vivo. J. Appl. Physiol. 101, 1685–1692 (1985).

Zak, M. A., Regish, A. M., McCormick, S. D. & Manzon, R. G. Exogenous thyroid hormones regulate the activity of citrate synthase and cytochrome C oxidase in warm- but not cold-acclimated lake Whitefish (Coregonus clupeaformis). Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 247, 215–222 (2017).

Ortenblad, N. et al. Reduced insulin-mediated citrate synthase activity in cultured skeletal muscle cells from patients with type 2 diabetes: evidence for an intrinsic oxidative enzyme defect. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1741, 206–214 (2005).

Williams, N. C. O’Neill, L.A.J. A role for the Krebs cycle intermediate citrate in metabolic reprogramming in innate immunity and inflammation. Front. Immunol. 9, 141 (2018).

Grunert, T. et al. A comparative proteome analysis links tyrosine kinase 2 (Tyk2) to the regulation of cellular glucose and lipid metabolism in response to poly(I:C). J. Proteom. 74, 2866–2880 (2011).

Liu, X. C. et al. Effects of Recombinant Toxoplasma gondii citrate synthase i on the cellular functions of murine macrophages in vitro. Front. Microbiol. 8, 1376 (2017).

Halliwell, B. & Gutteridge, J. M. C. Free Radicals in Biology and Medicine 3rd edn (Oxford University Press, 1999).

Farooqui, T. & Farooqui, A. A. (eds) Oxidative Stress in Vertebrates and Invertebrates: Molecular Aspects of Oxidative Stress on Cell Signalling (Wiley-Blackwell, 2011).

Plavšin, I. et al. Hormonal enhancement of insecticide efficacy in Tribolium castaneum: oxidative stress and metabolic aspects. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. C. 170, 19–27 (2015).

Večeřa, J., Krishnan, N., Mithöfer, A., Vogele, H. & Kodrík, D. Adipokinetic hormone-induced antioxidant response in Spodoptera littoralis. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. C. 155, 389–395 (2012).

Bednářová, A. et al. Adipokinetic hormone counteracts oxidative stress elicited in insects by hydrogen peroxide: in vivo and in vitro study. Physiol. Entomol. 38, 54–62 (2013).

Velki, M., Kodrík, D., Večeřa, J., Hackenberger, B. K. & Socha, R. Oxidative stress elicited by insecticides: a role for the adipokinetic hormone. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 172, 77–84 (2011).

Nguyen, C. D. & Lee, G. Neuroprotective activity of melittin—the main component of bee venom—against oxidative stress induced by Aβ25–35 in in vitro and in vivo models. Antioxidants 11, 1654 (2021).

Kim, B. Y., Lee, K. S. & Jin, B. R. Antioxidant activity and mechanism of action of Amwaprin: a protein in honeybee (Apis mellifera) venom. Antioxidants 13, 469 (2024).

Mao, Y. R. et al. Melittin alleviates oxidative stress injury in Schwann cells by targeting interleukin-1 receptor type 1 to downregulate nuclear factor kappa b-mediated inflammatory response in vitro. Cureus J. Med. Sci. 16, e65721 (2024).

Li, B. B. et al. Relationship between wooden breast severity in broiler chicken, antioxidant enzyme activity and markers of energy metabolism. Poult. Sci. 103, 103877 (2024).

Motohashi, H. & Yamamoto, M. Nrf2-Keap1 defines a physiologically important stress response mechanism. Trends Mol. Med. 10, 549–557 (2004).

Hedengren, M. et al. Relish, a central factor in the control of humoral but not cellular immunity in Drosophila. Mol. Cell. 4, 827–837 (1999).

Igaki, T. et al. Eiger, a TNF superfamily ligand that triggers the Drosophila JNK pathway. EMBO J. 21, 3009–3018 (2002).

Bgatova, N. et al. Gadd45 expression correlates with age-dependent neurodegeneration in Drosophila melanogaster. Biogerontology 16, 53–61 (2015).

Camilleri-Robles, C., Serras, F. & Corominas, M. Role of D-GADD45 in JNK-dependent apoptosis and regeneration in Drosophila. Genes 10, 378 (2019).

Moore, R. et al. Integration of JAK/STAT receptor–ligand trafficking, signalling and gene expression in Drosophila melanogaster cells. J. Cell. Sci. 133, jcs246199 (2020).

Long, M. J. C., Huang, K. T. & Aye, Y. Keap it in the family: how to fish out new paradigms in keap1-mediated cell signaling. Helv. Chim. Acta. 106, e202300154 (2023).

Yin, Y. et al. Bt Cry1Ab/2Ab toxins disrupt the structure of the gut bacterial community of Locusta migratoria through host immune responses. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 238, 113602 (2022).

Sanda, N. B., Hou, B. F., Muhammad, A., Ali, H. & Hou, Y. M. Exploring the role of relish on antimicrobial peptide expressions (AMPs) upon nematode-bacteria complex challenge in the Nipa palm hispid beetle, Octodonta Nipae Maulik (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae). Front. Microbiol. 10, 2466 (2019).

Zibaee, A. & Malagoli, D. The potential immune alterations in insect pests and pollinators after insecticide exposure in agroecosystem. Invertebrate Survival J. 17, 99–107 (2020).

Lisi, F. et al. Pesticide immunotoxicity on insects—Are agroecosystems at risk? Sci. Total Environ. 175467 (2024).

James, R. R. & Xu, J. Mechanisms by which pesticides affect insect immunity. J. tInvertebr Pathol. 109, 175–182 (2012).

Beckage, N. E. & Gelman, D. B. Wasp parasitoid disruption of host development: implications for new biologically based strategies for insect control. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 49, 299–330 (2004).

Sláma, K. & Lukáš, J. Myogenic nature of insect heartbeat and intestinal peristalsis, revealed by neuromuscular paralysis caused by the Sting of a braconid Wasp. J. Insect Physiol. 57, 251–259 (2011).

Pennacchio, F., Caccia, S. & Digilio, M. C. Host regulation and nutritional exploitation by parasitic wasps. Curr. Opin. Insect Sci. 6, 74–79 (2014).

Fletcher, J. E., Hubert, M., Wieland, S. J., Gong, O. H. & Jiang, M. S. Similarities and differences in mechanisms of cardiotoxins, Melittin and other myotoxins. Toxicon 34, 1301–13011 (1996).

Ownby, C. L., Powell, J. R., Jiang, M. S. & Fletcher, J. E. Melittin and phospholipase A2 from bee (Apis mellifera) venom cause necrosis of murine skeletal muscle in vivo. Toxicon 35, 67–80 (1997).

Prado, M., Solano-Trejos, G. & Lomonte, B. Acute physiopathological effects of honeybee (Apis mellifera) envenoming by subcutaneous route in a mouse model. Toxicon 56, 1007–1017 (2010).

Choo, Y. M. et al. Dual function of a bee venom Serine protease: prophenoloxidase-activating factor in arthropods and fibrin(ogen)olytic enzyme in mammals. Plos One. 5, e10393 (2010).

Munneke, L. R. & Collier, G. E. Cytoplasmic and mitochondrial arginine kinases in Drosophila: evidence for a single gene. Biochem. Genet. 26, 131–141 (1988).

Gupta, A., Thorson, P., Penmatsa, K. R. & Gupta, P. Rhabdomyolysis: revisited. Ulster Med. J. 90, 61–69 (2021).

Kume, H. et al. Cardiocerebral infarction presenting in a neurosurgical emergency: a case report and literature review. Cureus J. Med. Sci. 16, e65124 (2024).

Uda, K. et al. Evolution of the arginine kinase gene family. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. D. 1, 209–218 (2006).

Rahman, A. M. A., Kamath, S. D., Lopata, A. L., Robinson, J. J. & Helleur, R. J. Biomolecular characterization of allergenic proteins in snow crab (Chionoecetes opilio) and de Novo sequencing of the second allergen arginine kinase using tandem mass spectrometry. J. Proteom. 74, 231–241 (2011).

Ruethers, T. et al. Seafood allergy: A comprehensive review of fish and shellfish allergens. Mol. Immunol. 100, 28–57 (2018).

Ribeiro, J. C., Sousa-Pinto, B., Fonseca, J., Fonseca, S. C. & Cunha, L. M. Edible insects and food safety: allergy. J. Insects Food Feed. 7, 833–847 (2021).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the BC CAS core facility LEM supported by the Czech-BioImaging large RI project (LM2023050 and OP VVV CZ.02.1.01/0.0/0.0/18_046/0016045 funded by MEYS CR) for their support with obtaining scientific data presented in this paper. We are grateful to Dr. F. Weyda for consulting the SEM and TEM results. The English grammar and stylistics were checked by the Editage Author Services.

Funding

This study was supported by the projects No. 24–10662 S (Czech Science Foundation; DK). Work of JČ on the study was supported by the project No. 063/2022/P (Grant Agency of University of South Bohemia) and his stay at Mississippi State University was supported by Fulbright scholarship (Fulbright Commission, Czech-American governmental organization).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.Č.:Writing original draft, Investigation, Formal analysis; N.K.: Writing original draft, Formal analysis; N.P.: Investigation, Formal analysis; H.Š.: Investigation; D.K.: Writing original draft, Supervision, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original online version of this Article was revised: The original version of this Article contained an error in Figure 2. Full information regarding the corrections made can be found in the correction for this Article.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Černý, J., Krishnan, N., Prokůpková, N. et al. Elimination of certain honeybee venom activities by adipokinetic hormone. Sci Rep 15, 18638 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-02285-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-02285-4