Abstract

Shape memory alloys (SMAs) show exceptional potential in actuator design due to their shape memory effect and superelasticity, yet their thermoelectric hysteresis challenges accurate modeling. This study proposes a hybrid framework integrating long short-term memory (LSTM) networks with physical kinematics to predict SMA actuator responses. Unlike conventional approaches, our method decouples material behavior prediction from actuator geometry: A single-layer LSTM network processes voltage-time sequences to predict SMA wire’s temperature and resistance dynamics, while a physics-based model computes angular displacement through phase transformation and constitutive equations. Trained on 10 experimental conditions (1–2 °C/s heating rates) and tested on 3 unseen cases (0.8 °C/s), the model achieves a mean absolute error of < 5% in angular displacement prediction, with root mean square errors of 2.5 × 10−5 for temperature/resistance outputs. The modular architecture eliminates neural network retraining during structural iterations—only ordinary differential equation parameters require adjustment. This approach advances rapid actuator optimization, demonstrating faster computational efficiency compared to full-physics models. Our findings establish a computationally sustainable paradigm for smart material-based actuation systems, extensible to piezoelectric and magnetostrictive materials through constitutive parameter substitution.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

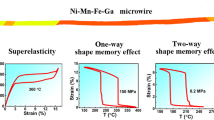

Smart materials have demonstrated significant potential in engineering applications, particularly in actuator design, owing to their exceptional power-to-weight ratio and lightweight characteristics. As a representative smart material, Shape Memory Alloys (SMAs) have attracted considerable attention due to their unique Shape Memory Effect (SME)1. SMA structures can recover their initial configuration through thermal stimulation when deformed by external forces. This distinctive property endows them with broad application prospects in diverse fields including aerospace2,3, automation4, and mechanical engineering5. At the microscopic level, SMAs exhibit multiple metallic phases: the Austenite phase (A) stabilized at elevated temperatures, the Twinned-Martensite phase (TM) under low-temperature/low-stress conditions, and the Detwined-Martensite phase (DM) under low-temperature/high-stress conditions. The fundamental mechanism of SME originates from temperature- and stress-induced phase transitions, representing the mutual transformation between these crystalline phases.

As intelligent actuators, SMAs can replace conventional motors through thermally induced recovery forces, substantially enhancing the lightweight characteristics of driving systems, particularly suitable for actuator applications requiring high power-to-weight ratios6,7. However, the actuation response of SMAs exhibits pronounced nonlinear hysteresis, which constrains their control precision.

Constitutive modeling serves as the cornerstone for revealing SMA actuation mechanisms8. In early research, scholars established various phenomenological models based on macroscopic theories to describe their thermodynamic behaviors: from Tanaka’s single-variant exponential model using martensite volume fraction9, to Liang and Rogers’ cosine-type phase transformation function10, and subsequently Brinson’s dual-variant decomposition theory11. These progressive developments have refined the description of phase transformation kinetics and enhanced the generalization capability of constitutive relationships. In an alternative theoretical framework, Ivshin and Pence12 established a system of differential equations incorporating stress, strain, temperature, and austenite volume fraction based on thermodynamic potentials, enabling continuous dynamic characterization of phase transition processes. The evolutionary trajectory of these models demonstrates a paradigm shift from single-phase transformation descriptions to coupled multi-mechanism modeling. Recent advances have further refined these models through incorporation of plasticity and creep mechanisms13,14,15, while considering practical physical factors such as cyclic loading16,17, strain rate18, and thermomechanical coupling19,20, thereby extending model applicability.

The refined constitutive models surmount numerous limitations inherent in traditional phenomenological approaches, significantly broadening their applicability. However, the intricate physical parameters within these models necessitate experimental calibration and exhibit pronounced sensitivity to environmental and loading conditions, thereby posing substantial challenges in engineering implementation. Contemporary researchers predominantly rely on experimental techniques or finite element methodologies, which inevitably introduce computational inefficiencies and prolonged processing durations. The considerable temporal and resource expenditures associated with conventional investigation approaches not only sustain elevated research costs but also protract product development cycles.

Recent years have witnessed burgeoning interest in employing neural networks and deep learning architectures to address diverse nonlinear problems, particularly catalyzing exploratory efforts to implement artificial intelligence in material behavior simulation21. Notably, Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks demonstrate exceptional proficiency in processing sequential data, rendering them particularly advantageous for predicting material responses with hysteretic characteristics.

Bhargaw et al.22 developed a self-sensing displacement estimation framework through deep neural networks (DNN) incorporating multi-layered LSTM architecture. Zakerzadeh et al.23 achieved precise prediction of angular variations in SMA rotary actuators under diverse input conditions using LSTM networks, with both single-step and multi-step ahead prediction experiments demonstrating the efficacy of this methodology in enhancing control precision. Raczka et al.24 successfully implemented LSTM-based neural networks for accurate simulation and prediction of SMA actuator behaviors. Through comparative analysis of 1-Dimensional Convolutional Neural Networks (1D-CNN) and LSTM models in position estimation utilizing the self-sensing properties of shape memory alloy wire actuators, Singh et al.25 substantiated the superior potential and advantages of LSTM architectures in such applications.

The implementation of LSTM neural networks enables high-precision prediction of nonlinear responses in SMA materials. However, existing data-driven models exhibit strong structural coupling with actuator configurations. Structural parameter modifications during iterative optimization processes may induce mismatches between pre-trained neural networks and redesigned actuators, necessitating recurrent retraining that substantially impedes developmental efficiency.

This study proposes a thermoelectric coupling response prediction methodology integrating LSTM neural networks with actuator physical characteristics: The LSTM network predicts real-time thermoelectric responses of SMA wires, while computational determination of actual actuator displacements is achieved through synergistic integration of predictions with phase transformation relationships, constitutive laws, and kinematic differential equations. Distinct from prior investigations, this approach decouples material response prediction from structural parameters, as the LSTM network exclusively forecasts SMA wire behaviors independent of specific actuator configurations. This architecture eliminates redundant network retraining across iterative design modifications. The proposed framework provides an efficient modeling paradigm for intelligent actuation systems, demonstrating critical engineering significance for compressing development cycles through enhanced computational sustainability.

Method

Recurrent neural network architecture and LSTM units

The Recurrent Neural Network (RNN) possesses memory in its hidden state, which allows it to predict future states based on previously remembered states26. The RNN unit exhibits the characteristic of being “unrolled” in time, meaning that each time step has an input xt and an output yt Here, ht represents the hidden state, and f denotes the recurrent connection of the RNN. One major drawback of the standard RNN model is its susceptibility to the problems of gradient vanishing and gradient explosion, which prevent it from learning long-term time series. The Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) further introduces memory cells and gating mechanisms, enabling it to effectively capture dependencies over longer time steps27. It has been widely applied in various time-related prediction tasks. Figure 1 shows the schematic diagram of an LSTM unit, where each unit comprises three gates that can be regarded as the storage elements of the neural network26, and each gate receives and utilizes the input information.

The mathematical expressions of the LSTM unit are given by Eq. (1) to (5), where Sig denotes the sigmoid activation function, tanh represents the hyperbolic tangent activation function, w is the weight matrix, and b is the unit bias:

Equation (1) defines the forget gate (ft), which determines which data in the memory cell should be retained or discarded at the current moment. An output of 0 means completely forgetting the previous information, while an output of 1 means completely retaining it. Equations (2) and (3) define the input gate, responsible for deciding how much new information at the current moment should be added to the state. Equation (4) defines the cell state (Ct). The output gate generates the current hidden state (Eq. (5)). Replacing the RNN units with LSTM units can significantly improve the performance of neural networks in making predictions based on long sequence datasets.

The properties of SMA exhibit significant temperature dependence. Research indicates that the temperature variation pattern of SMA is not only related to the current input voltage but also significantly influenced by historical voltage inputs, demonstrating a long-term dependency between temperature and voltage. To address the challenges in modeling the thermoelectric coupling hysteresis characteristics of SMA, this paper proposes the use of LSTM neural networks for predicting its thermo-electric coupling response. Specifically, an LSTM neural network model is constructed to predict the dynamic responses of temperature and resistance of SMA wires. The LSTM layer employs a sliding window of d time steps, with network inputs comprising voltage, temperature, and resistance values from the previous d time steps, along with the current voltage. Feature extraction is performed through a single-layer LSTM network, and predictions for the current temperature and resistance values are output through a fully connected layer containing 32 hidden units. The detailed structure of the model is illustrated in Fig. 2.

SMA rotary actuator model

This paper presents a differential rotary actuator based on SMA wire, whose actuation principle is illustrated in Fig. 3.

When the SMA wire is heated under voltage excitation, it undergoes austenite phase transformation, which macroscopically manifests as a reduction in length, thereby generating a driving force. This driving force overcomes the spring tension, causing the shaft to rotate. When the power supply is turned off and the temperature drops below the starting temperature of the martensite phase transformation, the driving force of the SMA wire disappears, and it returns to the initial state under the action of the spring, with the actuator’s rotation angle resetting to zero. The physical model of the SMA actuator can be divided into four parts: the electrothermal model, phase transformation model, mechanical constitutive relationship, and kinematic relationship22. Among these, the electrothermal model describes the temperature variation of the SMA wire under external electrical excitation, which can be replaced by the LSTM network model constructed in the previous section.

The phase transformation model describes the overall progress of the material’s phase transformation through the change in the martensite volume fraction (M). The hysteresis phenomena exhibited by SMA under different mechanical loading or temperature stimulation are closely related to the phase transformation model. Taking the martensite volume fraction as an example, the two processes can be respectively described as:

In the formula, x represents the volume fraction of martensite, with a value range of [0,1]. When x is 0, it indicates that the material is entirely in the austenite phase, and when x is 1, it indicates that the material is entirely in the martensite phase. Ms、Mf represent the start and finish temperatures of the martensite transformation, respectively. As、Af represent the start and finish temperatures of the austenite transformation, respectively.

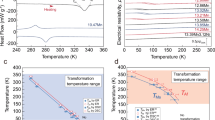

In some Ni-Ti alloys, the transformation between the martensite phase (B19’) and the austenite phase (B2) usually involves the participation of the intermediate R phase. Its phase transformation path is martensite phase ↔ R phase ↔ austenite phase, showing the characteristics of a two - step phase transformation, and the phase - transformation characteristics of the two stages are different28. The formation of the R phase is mainly due to the following reasons: Ni-rich composition (Ni > 50.5 at%) or the nano - precipitates of Ni-Ti alloy generated during thermomechanical treatment will cause local titanium depletion in the matrix, forming a composition gradient and stress concentration, which promotes the preferential nucleation of the rhombohedral R phase29. The characteristics of the R phase are significantly different from those of traditional phase transformations. It has a narrow phase transformation temperature hysteresis and low phase transformation stress, showing high reversibility, but the phase transformation strain is relatively small30.

Compared with the martensite phase (B19’), the lattice distortion of the rhombohedral R phase is significantly reduced, the atomic arrangement is more ordered, and the electron scattering is weakened, resulting in a lower resistivity. The resistance of the R phase is between that of the martensite phase and the austenite phase. Therefore, the phase transformation process of shape memory alloys can be analyzed through the resistance change curve.

Taking the heating process as an example, Fig. 4 shows the resistance change curve of a NiTi alloy wire during the heating process. When the alloy wire is heated, its resistance goes through four stages from ① to ④. In stages ① and ④, the resistance value increases slowly with the rise of temperature, corresponding to the period before the phase transformation occurs and after the phase transformation is basically completed, respectively. In stage ②, the resistance value decreases rapidly with the increase of temperature, indicating that most of the phase transformation from the martensite phase to the R phase is completed in this stage. In stage ③, the resistance value decreases slowly with the increase of temperature, indicating that the phase transformation from the R phase to the austenite phase mainly occurs in this stage.

In the two-phase model given by Eqs. (6) and (7), only the transformation between martensite and austenite is considered. The influence of temperature on the phase transformation process is described by a simple cosine relationship. However, as can be seen from the above analysis, the introduction of the R phase will increase the complexity of the phase transformation process. In this case, it is difficult for the traditional model to accurately describe the phase transformation law shown in Fig. 4.

Based on the experimental observation results of Ni-Ti alloys and the existing two-phase model, this paper proposes an exponential two-step phase transformation model, as shown in Eqs. (8) and (9). The remarkable feature of this model is that the phase transformation process is clearly divided into two stages: the transformation between the martensite phase and the R-phase is completed relatively quickly with temperature changes; while the transformation between the R-phase and the austenite phase is relatively slow.

In the formula, MR and AR represent the transformation temperatures of the intermediate phase, respectively. k1 ~ k4 are the transformation rate control coefficients for the two-step phase transformation, and w is the smoothing coefficient for the phase transformation process.

Figure 5 shows the evolution of the martensite volume fraction in the two-step phase transformation model under heating conditions. Its change law is highly consistent with the phase transformation process shown in stage ② and stage ③ in Fig. 4, which verifies the rationality of the model we proposed.

The constitutive relationship describes the relationship between the stress and strain of the SMA wire. The Reuss model (shown in Fig. 6) assumes that each phase in the material bears the same magnitude of load, and the macroscopic strain of the mixed phase is the superposition of the corresponding strains, which is:

The subscript M denotes the parameters of the martensite phase, and the subscript A denotes the parameters of the austenite phase. E represents the Young’s modulus of SMA in the pure martensite or pure austenite phase. dtr is the maximum phase transformation strain. c represents the coefficient of thermal expansion of the SMA. And T0 is the reference temperature. Assuming the initial state of the SMA wire is pure martensite phase, according to Equations (11), the initial strain \({\varepsilon _0}={\delta _{tr}}\).

In order to build the kinematics model of the rotary actuator, its structure was simplified, and the actuation principle obtained is shown in Fig. 7.

The right end of the SMA wire and the reset spring are fixed to a common point, while the left ends are fixed to points A and B on the upper and lower sides of the pulley, respectively. It is assumed that the forces exerted by the two on the pulley are F1 and F2. According to the design scheme, in the initial state, the lengths of the SMA wire and the spring are equal, with F1 = F2, keeping the pulley stationary. When the SMA wire is stimulated externally, it contracts and recovers, leading to F1 > F2, creating a torque M that acts on the pulley and causes it to rotate around the axis by an angle θ. Defining the displacement of point A, the left end of the SMA wire, to the right as x, then the angle θ through which the pulley has rotates and its second derivative can be expressed as:

In the formula, l represents the length of the SMA wire, and rp represents the radius of the pulley. The negative sign in the formula indicates that a positive deflection of the shaft corresponds to an increase in the displacement x, at which time the SMA wire contracts and its strain e decreases.

Knowing the pulley’s moment of inertia is J, we can determine that under the action of torque M, its angular velocity is:

The tensile force experienced by the SMA wire is numerically equal to the force it exerts on the pulley, F1. Rearranging the above equation and substituting Eq. (13), we can find the magnitude of the tensile force on the SMA wire:

Assuming that during the rotation of the pulley, the extension of the reset spring is equal to the contraction of the SMA wire, both being x, and the initial extension of the spring is 0. Let k be the stiffness coefficient of the reset spring, in this study, the spring stiffness coefficient k = 261 N/m, then the tensile force on the SMA wire is:

Further, we can determine the magnitude of the stress experienced by the SMA wire during contraction:

The kinematics model of the actuation response of the SMA rotary actuator can be obtained:

In the formula, Emix represents the Young’s modulus of the mixed phase, which is related to the volume fraction of martensite and is given by:

Equation (18) indicates that the actuation response of the SMA rotary actuator is jointly determined by the phase transformation and temperature. Due to the strong coupling between the electro-thermal model and the phase transformation model, the mathematical expressions are complex, which limits the practicality of pure physical models. On the other hand, if all four parts of the physical model are replaced with neural networks, issues such as weak generalization capability and long training time will arise: whenever the actuator structure is modified, new experiments must be conducted to collect data, and the entire network must be retrained, resulting in significant time and economic costs.

To address the aforementioned issues, this paper proposes a hybrid model that integrates neural networks with physical mechanisms to predict the actuation response of SMA actuators. The model employs an artificial neural network with an LSTM layer to predict the thermoelectric response of the SMA, outputting the temperature and resistance values of the SMA wire under voltage excitation. These outputs are then combined with the physical model of the actual actuator to estimate the angular displacement of the actuator. When the geometric structure of the actuator is modified, only the form and parameters of the ordinary differential equations in the physical model need to be adjusted, eliminating the need to retrain the neural network. This approach significantly improves efficiency and reduces computational costs. The principle is illustrated in Fig. 8.

First, the voltage and temperature data of the SMA wire during the experiment are collected and input into the trained LSTM neural network model. Subsequently, the neural network model takes the current voltage, along with the voltage, resistance, and temperature from the previous d time steps, as inputs to calculate the temperature and resistance of the SMA wire at the next time step. The physical model consists of differential equations that describe the response characteristics of the rotary actuator. By solving these ordinary differential equations, the angular displacement of the rotary actuator is obtained. The left side of Fig. 8 illustrates the training process of the LSTM neural network, while the right side depicts the solving process of the physical model. The loss function used during training is the Mean Squared Error (MSE).

A longer window time step size d may help improve the prediction accuracy of the model. However, it will also lead to an increase in the computational amount during the training of the LSTM model, and at the same time, increase the risk of overfitting. In order to determine the appropriate window time step size, the performance of the model was systematically tested when the value of d was in the range of 1 to 5. The results are shown in Table 1.

The test results show that when the window step size is greater than 3, the training duration increases by 6–8% for each additional step, while the improvement in the test MSE is less than 0.5 × 10−5 It can be seen that increasing the time step size leads to an increase in the training duration, but it has no significant effect on improving the prediction accuracy. From the perspective of practical applications, this additional resource consumption is unnecessary. Therefore, in this study, the window time step size is set to 3.

The input of the neural network includes the voltage, temperature, and resistance values of the previous 3 time steps, as well as the voltage at the current moment, with a total of 10 features. The output is the temperature and resistance at the current moment, with a total of 2 features. The parameter settings are shown in Table 2.

Experimental setup

In this study, a thermoelectric experimental system was designed to obtain the data required for training and validating the model. The thermoelectric experimental system consists of a differential SMA rotary actuator, a direct current (DC) power supply, a heating drive module, a control module, thermocouple sensors, an RS232 data acquisition module, and a computer configuration, as shown in Fig. 9.

DC power supply provides power to both the control module and the heating module. Within the control module, control signals are calculated based on the feedback temperature information. The SMA wire is pivoted with the driver shaft, with both ends connected to the positive and negative poles of the heating module, respectively. The heating module applies voltage to the SMA wire, and the experimental system collects temperature data of the SMA wire through a thermocouple, while the angle sensor rotates the actual output of the driver. During the experiment, the output voltage and current data of the heating module, as well as the collected temperature data of the SMA wire, are all uploaded to the computer through an RS232 data acquisition module.

Figure 10 shows the physical appearance of the SMA rotary actuator. The Ni-Ti alloy wires used in the experiment has a diameter of 0.2 mm. The material parameters of the SMA and the geometric parameters of the rotary actuator are provided in Table 3. The SMA wire is fixed to the pivot of the actuator’s rotating shaft, which can withstand temperatures above 200 °C. The two ends of the SMA wire are connected to the positive and negative outputs of the control module, respectively. A thermocouple is attached axially to the SMA wire using high-temperature tape to collect temperature data changes in the SMA wire during the process. An angle sensor is installed on the rotating shaft to measure the actual output angle of the rotary actuator.

During the experiment, the SMA wire heats up and undergoes an austenite phase transformation under electrical voltage excitation. The higher the applied voltage, the faster the heating rate, the higher the material temperature, and the shorter the actuation response time. It should be noted that prolonged overheating can cause thermal fatigue damage to the SMA wire, leading to a weakening or even loss of its shape memory properties. Therefore, the temperature settings in the experiment are all below 120 °C.

This section conducts a total of 13 experimental conditions for neural network training and model validation, with specific condition settings seen in Table 4. Among them, the data from Experiments 1 to 10 are used for training the LSTM recurrent neural network, with the training and validation sets divided in an 8:2 ratio. The data from Experiments 11 to 13 serve as the test set, utilizing heating rates outside the training range to verify the overall actuation response model. Figure 11(a) and Fig. 11 (b) show the curves of the SMA wire temperature and the output angle of the rotary actuator as functions of time in Experiments 11 ~ 13.

Result analysis

Figure 12(a), (b), and (c) respectively present the ANN model’s predictions of temperature and resistance values for three test sets. The ANN predictions in Fig. 12 show high agreement with the experimental data, indicating that the model effectively captures the thermoelectric coupling response characteristics of SMA materials under different voltage excitations.

In terms of temperature response, the temperature variation predicted by the model aligns almost perfectly with the experimental data. During the initial stage of the experiment, the amount of information remembered by the LSTM layer is still relatively low, resulting in a certain deviation between the predicted results and the experimental data within the first 50 time steps. Particularly, when the temperature approaches the set value, the output voltage becomes unstable due to the performance limitations of the control module, causing fluctuations in the SMA temperature near the set point. At this time, the ANN can capture this characteristic and predicts its behavior with minimal error.

Regarding resistance prediction, while the resistance of conventional metals typically increases with temperature, the resistivity of SMA materials drops sharply when the temperature reaches the austenite transformation start point due to the occurrence of the austenite phase transformation. After the phase transformation is complete, the resistance resumes its increasing trend with temperature. According to the temperature curves, the SMA wire in the experiment maintains the set temperature for a period before the input voltage decreases, causing the temperature to gradually drop, and the resistance follows suit. The three sets of resistance variation curves in Fig. 12 fully demonstrate this pattern, indicating that the model’s predictions of resistance values are highly accurate.

During the training, the MSE was used as the loss function, with the average MSE across the three test sets being 2.5 × 10−5. The top-left corner of each subplot in Fig. 12 displays the Mean Absolute Error (MAE) and Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) for the calculation results of each test set.

Figure 13(a), (b), and (c) present the scatter plots comparing the prediction results of three test sets with the ground truth. On the left side is the comparison of temperature data, and on the right side is the comparison of resistance data. The overall distribution of the scatter points is relatively dense, clustering around the perfect line with small deviations, indicating a strong linear relationship between the model prediction results and the true values. Among them, the scatter points of the temperature prediction data points cluster more closely around the perfect line, while the scatter points of the resistance prediction are relatively more dispersed. Through calculation, the correlation coefficient of the temperature prediction is 0.999894, which is closer to 1, and the correlation coefficient of the resistance prediction is 0.996917. This clearly shows that the model performs better in predicting temperature than in predicting resistance.

In order to eliminate the influence of the dataset division on the model’s prediction performance, an additional k-fold cross-validation was carried out on the model to evaluate its generalization ability. All the data of the test sets and training sets were combined and randomly and evenly divided into 5 subsets of similar sizes. Each time, one of the subsets was selected as the test set, and the remaining 4 subsets were used as the training set. After 5 times of training and testing using this method, the final RMSE obtained were 5.5 × 10−3, 8.1 × 10−3, 5.5 × 10−3, 5.5 × 10−3 and 4.0 × 10−3 respectively. The results of the cross-validation show that the model can provide reliable predictions under different experimental conditions and has good robustness.

To further enhance model performance, the sources of error were analyzed from two perspectives: experimental setup and model structure. On one hand, errors may exist in the training data due to experimental instabilities, such as minor fluctuations in power supply output or measurement errors from temperature sensors, which introduce uncertainties into the training data. These uncertainties can cause deviations during the neural network’s learning process and ultimately affect the prediction results. On the other hand, the sensitivity of simulation results to LSTM network parameters can significantly impact prediction errors. For example, if the time step of the window width is set too small, it may fail to fully capture the thermoelectric coupling hysteresis characteristics of SMA materials over long time sequences; if set too large, it increases computational complexity and may lead to overfitting, reducing the model’s generalization ability and making it difficult to accurately predict SMA responses under different operating conditions.

Based on the above analysis, future research should focus on the following aspects: First, optimize experimental condition control by calibrating data acquisition equipment before experiments to improve measurement accuracy and minimize errors caused by external factors. Second, after completing the neural network modeling, sensitivity analysis of model parameters should be conducted using techniques such as cross-validation. By testing the performance of different parameter combinations on various datasets, the optimal parameter settings can be determined to enhance the model’s adaptability. Through these methods, prediction errors can be further reduced, and the reliability of SMA thermoelectric coupling response predictions can be improved.

Figure 14(a), (b), and (c) show the angular displacement curves of the rotary actuator under different voltage excitations, where the diamond markers indicate the errors between the simulation results and experimental values at different time points.

The angular displacement trends obtained from the simulation calculations are generally consistent with the experimental data, with average relative errors of 4.10%, 3.66%, and 2.83% during the response process. This indicates that the physical model constructed in this study can accurately describe the actuation response of the designed rotary actuator. From the three curves, it can be observed that the starting points of the angular changes in the simulation results align almost perfectly with the experimental results, and the agreement is high during the rising phase. This suggests that, given accurate input temperatures, the physical model can effectively predict the response time of the rotary actuator.

It is worth noting that, except for the results of Experiment 11 (Fig. 14(a)), the steady-state values of the simulation results for the other two curves are slightly lower than the experimental values. This discrepancy is primarily due to the assumption of ideal phase transformation and constitutive relationships in the physical model: it assumes that once the temperature reaches the austenite transformation finish temperature, the martensite in the material can completely transform into austenite, and the transformation strain is fully recovered. However, in practice, not only is the austenite transformation finish temperature influenced by external loads9, but the SMA also exhibits thermal fatigue characteristics due to cyclic actuation, leading to changes in the recovery force and maximum transformation strain. Additionally, the physical model constructed in this study does not account for incomplete transformation between martensite and austenite or partial plastic deformation, making it unable to fully simulate the angular displacement changes under real conditions. These are the main reasons for the errors between the experimental and predicted results in Fig. 14. In future research, various influencing factors can be gradually incorporated into the prediction model to further enhance its completeness and prediction accuracy.

Conclusions and discussion

This study proposes and validates a hybrid modeling framework integrating Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) neural networks with actuator dynamic physics for predicting the response of SMA rotary actuators, achieving multi-physical field coupling state (temperature, resistance) monitoring and angular displacement prediction. A series of comparative experiments demonstrate the reliability and robustness of the proposed method, yielding the following conclusions:

Key findings

-

(1)

A hierarchical modeling strategy was developed based on SMA’s thermoelectric coupling mechanism: The electrothermal-phase transformation coupling process was abstracted into a single-layer LSTM module to predict dynamic temperature and resistance responses from voltage inputs. Concurrently, a system of ordinary differential equations (ODEs) incorporating constitutive relationships and kinematic equations was established to characterize angular displacement evolution. The synergistic solution of neural networks and physical equations enables high-precision angular displacement prediction under various voltage stimuli.

-

(2)

Validation on test datasets demonstrates that the model attains a root mean square error (RMSE) of 2.5 × 10−5 for temperature and resistance predictions, with an average angular displacement prediction error below 5%.

-

(3)

The innovation of this model lies in its modular architecture: When actuator geometric parameters are modified, only ODE parameters require adjustment while the neural network module remains unchanged, enabling direct reuse. This approach significantly reduces retraining costs compared to conventional methods, offering a novel paradigm for rapid iterative actuator design.

Discussion

-

(1)

A discrepancy of approximately 7% between experimental and predicted maximum angular displacements is observed, primarily attributed to two factors: First, the current model simplifies thermal hysteresis effects during cyclic phase transformations; second, training data lacks thermal fatigue damage under prolonged cyclic loading, which notably alters austenite-martensite phase transformation thresholds16. Future studies should incorporate fatigue constitutive models to enhance the physical constraints of the neural network.

-

(2)

Through error analysis encompassing training data uncertainty, model parameter sensitivity, and completeness of phase transformation influencing factors, this work identifies future research priorities: refined experimental condition control, systematic parameter sensitivity evaluation, and enhanced phase transformation modeling. These advancements are expected to improve model completeness and simulation accuracy.

-

(3)

The hybrid modeling framework demonstrates promising cross-material extensibility. By replacing material parameter modules in constitutive equations, the methodology can be generalized to smart actuation systems employing piezoelectric ceramics, magnetostrictive materials, or other multifunctional materials, thereby providing a universal tool for designing smart actuators.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Guo, Z., Pan, Y., Wee, L. B. & Yu, H. Design and control of a novel compliant differential shape memory alloy actuator. Sens. Actuators A. 225, 71–80 (2015).

Leester-Schädel, M., Hoxhold, B., Lesche, C. & Demming, S. Büttgenbach. Micro actuators on the basis of thin SMA foils. Microsyst. Technol. 14, 697–704 (2008).

Jiannan, Y. et al. Bi-direction and flexible multi-mode morphing wing based on antagonistic SMA wire actuators. Chin J. Aeronaut. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cja.2024.06.030 (2024).

Luchetti, T., Zanella, A., Biasiotto, M. & Saccagno, A. Electrically actuated antiglare rear-view mirror based on a shape memory alloy actuator. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 18, 717–724 (2009).

Elahinia, M. H., Koo, J. H. & Tan, H. Improving robustness of tuned vibration absorbers using shape memory alloys Shock Vib. 12 349–361 (2005).

Kim, M. S. et al. Ahn. Shape memory alloy (SMA) actuators: the role of material, form, and scaling effects. Adv. Mater. 35, e2208517 (2023).

Khan, A. M., Kim, Y., Shin, B., Moghadam, M. H. & Mansour, N. A. Modeling and control analysis of an arc-shaped SMA actuator using PID, sliding and integral sliding mode controllers. Sens. Actuators A. 340, 113523 (2022).

Elahinia, M. H. & Ahmadian, M. An enhanced SMA phenomenological model: I. The shortcomings of the existing models. Smart Mater. Struct. 14, 1297 (2005).

Tanaka, K. A thermomechanical sketch of shape memory effect:One-dimensional tensile behavior. Res. Mech. 18, 251–263 (1986).

Liang, C. & Rogers, C. A. One-dimensional thermomechanical constitutive relations for shape memory materials. J. Intell. Mater. Syst. Struct. 8, 285–302 (1990).

Brinson, L. C. One-dimensional constitutive behavior of shape memory alloys: thermomechanical derivation with non-constant material functions and redefined martensite internal variable. J. Intell. Mater. Struct. 4, 229–242 (1993).

Ivshin, Y. & Pence, T. J. A thermomechanical model for a one variant shape memory material. J. Intel Mat. Syst. Str. 5, 455–473 (1994).

Kumar, P. K. & Lagoudas, D. C. Experimental and microstructural characterization of simultaneous Creep, plasticity and phase transformation in Ti50Pd40Ni10 high-temperature shape memory alloy. Acta Mater. 58, 1618–1628 (2010).

Yan, W., Wang, C. H., Zhang, X. P. & Mai, Y-W. Theoretical modeling of the effect of plasticity on reverse transformation in superelastic shape memory alloys. Mater. Sci. Eng. A. 354, 146–157 (2003).

Kato, H. & Sasaki, K. Transformation-induced plasticity as the origin of serrated flow in an NiTi shape memory alloy. Int. J. Plast. 50, 37–48 (2013).

Khalil, W. et al. Experimental analysis of Fe-based shape memory alloy behavior under thermomechanical Cyclic loading. Mech. Mater. 63, 1–11 (2013).

Hartl, D. J. & Lagoudas, D. C. Constitutive modeling and structural analysis considering simultaneous phase transformation and plastic yield in shape memory alloys. Smart Mater. Struct. 18, 104017 (2009).

Helbert, G. et al. Experimental characterisation of three-phase NiTi wires under tension. Mech. Mater. 79, 85–101 (2014).

Dorian, D., Anne, M., Karine, L. T. & Olivier, H. Thermomechanical modelling of a NiTi SMA sample submitted to displacement-controlled tensile test. Int. J. Solids Struct. 51, 1901–1922 (2014).

Sun, Q. P., Zhao, H., Zhou, R., Saletti, D. & Yin, H. Recent advances in micromechanics of materials recent advances in Spatiotemporal evolution of thermomechanical fields during the solid-solid phase transition. Comptes Rendus Mecanique. 340, 349–358 (2012).

Wang, F. Neural network model for hysteretic characteristic of shape memory alloy. Mater. Today Commun. 35, 105963 (2023).

Hari, N., Bhargaw, S., Singh, S., Singh, S. A. & Akbar, S. A. R. Hashmi and Poonam Sinha. Deep neural Network-Based Physics-Inspired model of Self-Sensing displacement Estimation for antagonistic shape memory alloy actuator. IEEE SENS. J. 22, 3254–3262 (2022).

Zakerzadeh, M. R., Naseri, S. & Naseri, P. Modelling hysteresis in shape memory alloys using LSTM recurrent neural network. J. Appl. Math. 2024, 1–14 (2024).

Waldemar, Rączka & Marek Sibielak. Model of Shape Memory Alloy Actuator with the Usage of LSTM Neural Network Materials 17 3114 (2024).

Samarth Singh, Hari, N., Bhargaw, M., Jadhav, P. & John A comparative analysis between deep neural network-based 1D-CNN and LSTM models to Harness the self-sensing property of the shape memory alloy wire actuator for position Estimation. Smart Mater. Struct. 33, 085045 (2024).

Hochreiter, S. & Schmidhuber, J. Long short-term memory. Neural Comput. 9, 1735–1780 (1997).

Jozefowicz, R. & Zaremba, W. and I. Sutskever An empirical exploration of recurrent network architectures Proc. Int. Conf. Mach. Learn. 2342–2350 (2015).

Helbert, G. et al. A uniaxial constitutive model for superelastic NiTi SMA including R-phase and martensite transformations and thermal effects. Smart Mater. Struct. 26, 025007 (2017).

Zhu, J. et al. Influence of Ni4Ti3 precipitation on martensitic transformations in NiTi shape memory alloy: R phase transformation. Acta Mater. 207, 116665 (2021).

Bo Feng, X. et al. In-situ synchrotron high energy X-ray diffraction study of micro-mechanical behaviour of R phase reorientation in nanocrystalline NiTi alloy. Acta Mater. 194, 565–576 (2020).

Acknowledgements

This work was sponsored by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 12372085).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.D. wrote the main manuscript text. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ding, S., Liu, L., Zhang, S. et al. An LSTM-driven thermoelectric coupling response prediction method for shape memory alloy actuators. Sci Rep 15, 17642 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-02306-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-02306-2