Abstract

This article introduces a novel deep-learning based framework, Super-resolution/Denoising network (SDNet), for simultaneous denoising and super-resolution of swept-source optical coherence tomography (SS-OCT) images. The novelty of this work lies in the hybrid integration of data-driven deep-learning with a model-informed noise representation, specifically designed to address the very low signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) and low-resolution challenges in SS-OCT imaging. SDNet introduces a two-step training process, leveraging noise-free OCT references to simulate low-SNR conditions. In the first step, the network learns to enhance noisy images by combining denoising and super-resolution within noise-corrupted reference domain. To refine its performance, the second step incorporates Principle Component Analysis (PCA) as self-supervised denoising strategy, eliminating the need for ground-truth noisy image data. This unique approach enhances SDNet’s adaptability and clinical relevance. A key advantage of SDNet is its ability to balance contrast-texture by adjusting the weights of the two training steps, offering clinicians flexibility for specific diagnostic needs. Experimental results across diverse datasets demonstrate that SDNet surpasses traditional model-based and data-driven methods in computational efficiency, noise reduction, and structural fidelity. The framework excels in improving both image quality and diagnostic accuracy. Additionally, SDNet shows promising adaptability for analyzing low-resolution, low-SNR OCT images, such as those from patients with diabetic macular edema (DME). This study establishes SDNet as a robust, efficient, and clinically adaptable solution for OCT image enhancement addressing critical limitations in contemporary imaging workflows.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Retinal optical coherence tomography (OCT) is a non-invasive imaging modality that enables high-resolution, cross-sectional visualization of retinal layers1. It operates by acquiring millions of depth-resolved measurements, or A-scans, within millimeter-scale volumes at MHz sampling rates. By arranging these A-scans into 2D images, or B-scans, OCT constructs a 3D volumetric view of retinal structures, facilitating in vivo screening of various retinal diseases, such as diabetic macular edema (DME), age-related macular degeneration (AMD), and choroidal neovascularization (CNV)2,3. Additionally, recent researches indicate that OCT can serve as a valuable tool for identifying early markers of neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, dementia, and multiple sclerosis4,5,6.

Despite these advantages, OCT imaging is challenged by multiple sources of degradation, including sampling limitations, eye movement, blinking, and variability across devices. These factors frequently result in low signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) and low-resolution images, complicating the diagnostic process. Given the large volume of low-quality images clinicians must interpret, effective OCT image enhancement is crucial for improving diagnostic accuracy, extending the field of view, and enabling disease-focused analysis of specific B-scans7.

Enhancing images is an inverse problem due to the absence of clean data and undegraded images, which must be reconstructed from noisy observed images. Solutions to this issue can be approached from different perspectives, broadly categorized into data-driven and model-driven methods. In data-driven approaches, the solution is derived by analyzing various data samples and learning a mapping to extract a clean image, often through a deep learning network operating in either a supervised or unsupervised paradigm. In the supervised paradigm with paired-data, the network is trained using a clean image corresponding to a noisy image. Clean image can be obtained through multiple frame averaging in OCT8,9,10,11. However, these approaches have two main drawbacks: firstly, they require multiple registered image acquisitions from a single physical location, and secondly, while averaging multiple frames can mitigate additive noise, speckle noise which is multiplicative, remains a challenge12,13.

Generative modeling and image-to-image translation methods can address the need for paired-data by utilizing unpaired noisy and noise-free image sets. These models consist of a generator that translates images from noisy domain to the noise-free domain and a discriminator that ensures the validity of the translation. Nevertheless, effective generative domain translation requires large datasets from both domains to generate valid images, and the retinal structure varies across different domains14,15,16,17. These challenges can lead to suboptimal reduction of speckle noise, resulting in residual noise in the final image7.

Model-driven methods rely on physical modeling of image acquisition and degradation processes, using this foundation to apply noise-reduction techniques. Generally, model-driven method approaches suggest filtering methods, such as block-matching 3D or 4D (BM3D/BM4D) filters and sparse decomposition methods like KSVD18,19,20. Also, due to stochastic properties of degradation, statistical modeling approaches are also introduced for solving image restoration tasks. These methods define statistical priors for degradation or noise-free image and try to estimate desired image through an optimization problem. For OCT images, several priors have been defined, such as the symmetric α-stable model21,22, non-symmetric Laplace-Gaussian23,24, and Bessel K-form models13, to further refine the restoration process by encoding OCT-specific noise characteristics. While model-driven methods have demonstrated progress, they often face limitations, such as incomplete models, restrictive assumptions, and the need for iterative processing, making them challenging to deploy in clinical practice.

In contrast, data-driven approaches use large datasets of paired noisy and noise-free images to train parametric models, notably deep learning architectures, for OCT enhancement. Although deep learning methods yield superior results, their reliance on vast amounts of annotated data remains a constraint, especially in medical imaging where ground-truth images are scarce. This need is exacerbated when low-SNR and low-resolution samples are coupled with ground truth requirements25.

Hybrid models combine the strengths of both approaches, incorporating prior knowledge of image characteristics into learnable models. Techniques such as denoising priors, deep image priors, and diffusion models have proven effective in inverse problems and image generation tasks. They accompanied by a plug-and-play (PnP) method such as alternative direction of multipliers method (PnP-ADMM) to allow iterative refinement of the generated image, conditioned on prior constraints. This prior can models using scored based diffusion model and a data fidelity norm26,27.

Although such models offer promising outcomes, their dependence on iterative sampling remains a practical limitation. In medical imaging, Noise2Noise28,29, Noise2Void30,31, and Noise2Self32 have emerged as hybrid solutions, addressing noise elimination through self-supervised methods. However, these techniques often produce overly smooth outputs, which may obscure critical textures needed for clinical interpretation27. Table 1 shows summary of literature on OCT image denoising.

This study aims to develop a hybrid deep learning model that incorporates OCT-specific noise and texture characteristics to enhance low-SNR, low-resolution images while preserving essential textural details. The proposed method uses a noise-free OCT dataset as a reference, at the first step of the training process. The domains of the noise-free dataset aligned on and the noisy images domain. In this step, the SDNet was trained on pair of noise-free and their corrupted version to learn domain transformation. While, this step focuses only on the noise, in second step, network will be trained to learn structure of retina texture from noisy dataset. At this step, SDNet was trained to map noisy low-resolution SS-OCT images to slightly low-noised counterpart providing by Principle Component Analysis (PCA). This self-supervised training on noisy dataset, enforces SDNet to preserve its fidelity to structural context of noisy-dataset. These two steps lead to separate training weights. By mixing these weights, it makes a tunable flow for trade-off between texture & contrast based on clinician usage and needs. The key contributions of this work can be listed as follows:

-

A new hybrid model-aware deep-learning method for low-SNR /low resolution OCT enhancement is presented.

-

Introduction of a novel self-supervised approach for transforming domain of noisy images into domain of noise-free dataset.

-

This method is adjustable for denoising based on contrast-texture tradeoff.

-

Introduction of a new method which is easily applicable on various OCT dataset as shown in our experiments.

-

Producing enhanced image which are more similar to OCT image by meaning of kernel inception distance.

Additionally, we evaluate quality of the enhanced images by employing multiple-instance learning (MIL) for subject-level classification. This classification highlights disease-relevant B-scans, enhancing interpretability for clinicians and supporting the clinical utility of the enhanced images.

The structure of this paper is as follows: “Methodology” details the dataset, task definitions, and solution methodology. “Experiments” and “Results” present experimental results and analysis, and “Discussion” and “Conclusion” concludes the work with key findings and future directions.

Methodology

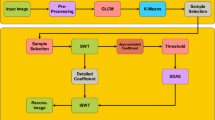

As illustrated in Fig. 1, training of the proposed method was performed at two phases: (1) training on images from Noise-Free domain when degradation is added using noise model from noisy dataset to learn increased contrast on noisy image, (2) training on noisy domain while coarse noise reduction is used, to enhance texture fidelity on noisy domain.

A. Datasets

This study utilizes two datasets: a high-quality noise-free dataset (HCIRAN)33 and a noisy, lower-quality dataset (Basel SS-OCT). The HCIRAN dataset, captured with a Heidelberg OCT-Spectralis imaging device, serves as the noise-free reference. It comprises 3,858 B-scans from 79 healthy individuals, providing high-quality, high-resolution images for the enhancement process.

The noisy Basel SS-OCT dataset includes images from 100 patients, divided into three groups: 40 healthy individuals, 30 with diabetic macular edema (DME), and 30 with other retinal diseases (non-DME)21. These groups make up the training dataset, while an additional 18 patients form the test set. The training images have low SNR and a resolution of 300 × 300 pixels 34. The test dataset images are not only low SNR but also exhibit lower resolution (150 × 320 or 200 × 300 pixels), as some A-scans have been uniformly dropped. For training, we used the SS-OCT training set al.ong with the HCIRAN dataset, while the SS-OCT test dataset was reserved for evaluation. Table 2 summarizes the key characteristics of these datasets.

While this work focuses on low-SNR images from SS-OCT dataset, we additionally testing the proposed method on three additional datasets; these datasets are from different capturing device vendors and image qualities. These additional datasets will be introduced in Additional Datasets section.

B. Noise model in SS-OCT dataset

Different device vendors and imaging configuration results in varied OCT image quality in terms of texture, noise, and SNR. The literature includes numerous studies modeling OCT images or OCT noise. For instance, in some 3D-OCT Topcon devices, the image speckle manifests as a salt-and-pepper-like texture, which can be modeled using the Poisson-Gaussian model 35. Other imaging devices, such as the Heidelberg SD-OCT, exhibit multiplicative noise that follows a generalized scaled Gaussian mixture model, incorporating Gamma distribution noise and Gaussian mixture to represent the retina13,37. Using sparse representation via wavelet transformation and relaxing the Poisson-Gaussian model, OCT images can be modeled using combination of Laplace and Gaussian noise23,38.

The SS-OCT dataset images exhibit significant noise that predominates the image structure, particularly in non-retinal regions such as the Vitreous, where the absence of retinal features results in pure noise. Figure 2 provides examples of SS-OCT training data was manually separated. As shown in Fig. 2, the histogram of the Vitreous region is compared with Gaussian distribution when the image is scaled to the range (0,1). The third-row image illustrates the mean and standard deviation (std) of the Vitreous region relative to the entire image, with a bounding line indicated. We assumed a Gaussian distribution with a mean and std calculated within the range (75%, 95%) and (50%, 90%) of the mean and standard deviation of the entire image, respectively.

Since retinal region in SS-OCT images are different than HCIRAN images, for noise synthesis on the HCIRAN dataset, preprocessing included cropping and resizing the images to match the dimensions and size characteristics of retina in the SS-OCT dataset. First, the retinal region in each HCIRAN image was extracted through thresholding followed by morphological closing. The area around the retina was then cropped with a random margin between 50 and 100 pixels above and below the retinal boundary box. This cropped image was resized to 300 × 300 pixels. Gaussian noise, matching the characteristics modeled from the SS-OCT dataset, was then added to the images to simulate low-SNR conditions. Figure 3 illustrates the pre-processing workflow.

Here, we assume the operator \(\:G\left(x\right)\) converts image \(\:x\in\:HCIRAN\) to resized version of ground-truth image in Fig. 3. Then the operator \(\:N\left(G\right(x\left)\right)\) add noise as states in Fig. 3 to the \(\:G\left(x\right)\). The first phase of training can formulate as \(\:\genfrac{}{}{0pt}{}{min}{{W}_{h}}{\mathbb{E}}_{x\in\:HCIRAN} || F\left(N\left(G\left(x\right)\right);{W}_{h}\right)-G\left(x\right) || \:\); when \(\:{F(.,;\:W}_{h})\) is network with training parameters \(\:{W}_{h}\).

C. Preprocessing for super-resolution task

In the SS-OCT test dataset, images suffer from low resolution due to a reduced A-scan sampling rate, similar to the training dataset. The goal of the super-resolution task is to reconstruct these dropped A-scans by interpolating between the observed ones, effectively restoring the full image details.

To achieve this, we initially fill the missing A-scans with noise generated according to the SS-OCT image noise model described in Section B. This step produces low-resolution images with the same dimensions as high-resolution reference images, but with a portion of their A-scans containing only noise rather than retinal details. As shown in Fig. 4, this method converts the super-resolution task into a form of denoising. Consequently, both the denoising and super-resolution tasks can be addressed within a unified framework, allowing the model to handle noise suppression and resolution enhancement in a single step.

This integrated approach enables the proposed platform to learn and refine the underlying retinal structure while discarding noise and filling in missing A-scan information, ultimately yielding high-quality images suitable for clinical use and further analysis.

D. Principle component analysis for coarse noise reduction

the HCIRAN dataset contains high-resolution, noise-free images, enables supervised pretraining of the model. However, fine-tuning the network on the SS-OCT training dataset, which lacks noise-free samples, presents a challenge. To enable fine-tuning while preserving the original texture of the SS-OCT images, we employ a self-supervised approach that generates a “noise-less” target image from the image itself.

The primary goal of this section is to replicate the ability of simple denoising methods to reduce a small amount of noise in low-SNR SS-OCT images while simultaneously allowing the network to learn the important retinal textures in this dataset. Technically, the denoiser, \(\:D(.;\alpha\:)\) with denoising rate \(\:\alpha\:\) can be any method, such as BM3D18, GT-SC-GMM 38, or wavelet denoiser 39. For simplicity and experimentation on different methods, we adopt PCA due to its rapid volume denoising and adjustable denoising rate \(\:\alpha\:\). This training stage can be formulated as \(\:\genfrac{}{}{0pt}{}{min}{{W}_{s}}{\mathbb{E}}_{y\in\:SS-OCT} || F\left(y;{W}_{s}\right)-D(y;\alpha\:) ||\); where the network parameters, \(\:{W}_{s}\) are initialized by \(\:{W}_{h}\). This leads to a self-supervised training method on SS-OCT dataset.

This “self-supervised noise-less” image is obtained by removing uncorrelated noise components using PCA. By only retaining principal components with the highest energy, PCA effectively filters out most of the noise while preserving the key structural elements of the image.

The steps for this process are as follows: each individual’s B-scans are aligned along one axis, resulting in an initial transformation into a matrix of 45,000 vectors (300 × 150 or 60,000 for 300 × 200 pixels per B-scan). Each vector represents a single point in a space with a dimension equal to the number of B-scans, typically ranging from 50 to 300. PCA is then applied to this high-dimensional space, and only the top 15% of principal components (those with the most energy) are retained for reconstruction. This selective reconstruction significantly reduces noise while maintaining essential image texture.

The detailed procedure is illustrated in Algorithm 1.

This approach ensures that the fine-tuning stage is guided by images that have reduced noise but still retain essential retinal texture. By leveraging PCA for targeted noise removal, the model is better equipped to learn meaningful features and preserve critical structural details of the SS-OCT dataset during denoising. Figure 5 shows two sets image before and after PCA noise reduction. As seen in this figure, PCA may lead to shadowy blurred image.

E. Proposed method for super-resolution and denoising task

In this study, we propose the Super-resolution/Denoising Network (SDNet), a modified U-Net-based 40 architecture specifically designed for the dual tasks of super-resolution and denoising in OCT images. The primary reason for selecting U-Net as the backbone of SDNet is its ability to achieve perfect reconstruction. However, the forward path of U-Net consists of pooling and unpooling layers, which capture primarily low-frequency components. While the skip connections pass both low and high-frequency components to the decoder, this leads to a limitation in achieving perfect reconstruction 41. Additionally, since OCT images have high-frequency texture, we have added new components to U-Net to correct the weighting between low and high-frequency components. SDNet incorporates several key enhancements over traditional U-Net models to ensure effective noise reduction and preservation of fine retinal texture during resolution enhancement.

As illustrated in Fig. 6, SDNet consists of an encoder-decoder architecture with four levels of depth in both the encoder and decoder paths. Each level in the encoder comprises three residual blocks 42, designed to capture and retain essential image features while allowing effective gradient flow through skip connections. These residual blocks help mitigate vanishing gradients and facilitate the extraction of detailed, multi-scale features critical for both denoising and resolution recovery. Through trial-and-error, we determined that three residual blocks at each stage provided the best performance for both reconstruction error and visually preserving OCT texture.

To better retain spatial and textural information, SDNet includes three skip connections, after each residual block, that directly transfer feature maps from each encoder stage to its corresponding decoder stage. These connections enable the network to reuse fine-grained spatial details lost during down-sampling.

Furthermore, to enhance the network’s ability to focus on relevant regions and maintain the texture fidelity of the reconstructed OCT images, each stage in the decoder incorporates a self-attention layer. Self-attention helps the network selectively emphasize high-frequency details from the texture of retinal layers in the image by observing different images from the dataset during training, which is particularly beneficial in the training process 43.

For conclusion, Algorithm 2 shows the training phases and inferencing procedure of the proposed method.

Experiments

All experiments in this study were conducted using Python 3.12 with TensorFlow 2.18 as the deep learning framework on a computer with Ubuntu 24.04 as operating system, two installed NVIDIA GTX 1080ti on, with Intel® Core™ i7 7800 × 12 CPU, and 48 GB RAM. The training procedures utilized the HCIRAN and SS-OCT training datasets, with results evaluated on the SS-OCT test dataset. The method was trained using Adam optimizer with learning rate between 10− 4 decayed to 10− 5 after 100 epochs of training 45.

A. Evaluation metrics

The evaluation process for this study comprises two approaches tailored to specific tasks. For the image enhancement component, we define three metrics to quantitatively assess the quality of enhancement: (1) Contrast-to-Noise Ratio (CNR), (2) Mean-to-Standard-Deviation Ratio (MSR), (3) Texture Preservation (TP), and (4) peak-signal-to-noise ratio. The formulations for each metric are detailed in (1) through (3), defined as follows:

Contrast-to-Noise Ratio (CNR): The CNR is defined as

where, \(\:{\mu\:}_{b}\) and \(\:{\sigma\:}_{b}\) represent the mean and standard deviation of the background region of interest (ROI), respectively, while \(\:{\mu\:}_{f}\) and \(\:{\sigma\:}_{f}\) are the corresponding values for the foreground ROI. This metric is critical for assessing contrast improvements between different regions.

Mean-to-Standard-Deviation Ratio (MSR): The MSR, formulated in (2), is specifically calculated for the foreground ROI within relevant retinal layers:

This metric provides an understanding of the balance between signal mean and variability in key areas of the retina.

Texture preservation (TP): The TP shown in Eq. 3, measures the retention of image texture after denoising:

where, M denotes the number of selected ROIs within retinal layers. Two parameters \(\:{\sigma\:}_{m}\) and \(\:{\sigma\:}_{m}^{{\prime\:}}\) represent the standard deviations of the denoised and noisy ROIs, respectively, while \(\:{\mu\:}_{m}\) and \(\:\:{\mu\:}_{m}^{{\prime\:}}\) stand for the mean of the denoised and noisy ROIs, respectively. TP quantifies the model’s capability to maintain texture fidelity, ensuring that the enhanced image remains true to the original in fine details.

Peak-signal-to-noise ratio (PSNR): The PSNR, formulated in (4), compares maximum of denoised image value to noise standard deviation.

when \(\:{I}_{max}\) indicates maximum value of the denoised image, and \(\:{\sigma\:}_{n}\) denotes standard deviation of noisy ROI in original image. For those metrics that need noise properties, the vitreous region can be considered as pure noise on the OCT images as shown in Fig. 2.

These metrics allow for a comprehensive assessment of enhancement effectiveness across contrast, clarity, and texture preservation, essential for evaluating improvements in SS-OCT image quality.

Structural similarity index measure (SSIM): SSIM is a measurement to evaluate how each method preserve texture of denoised image to the original image 46.

Kernel inception distance (KID): unlike previous metrics, this measurement evaluates how likely the output of each method can be similar to noise-less OCT images 47.

B. Additional datasets

To have better understanding of the model performance on diverse dataset, three additional datasets are also evaluated in this paper. The dataset 3D-OCT-1000 48 contains 3D-OCT volumes from normal subjects or diagnosed to have retinal Pigment Epithelial Detachment. Bioptigen (Durham, NC, USA) is the second dataset captured OCT images using SD-OCT Bioptigen device 49. The third dataset is a part of A2A SD-OCT dataset contains images in size 512 × 1000 pixels3.

C. Noise model on additional datasets and training

Since the image texture, noise model, and retina appearance in additional datasets differ from those in the SS-OCT dataset, the noise augmentation and denoising procedures used for SS-OCT are not generalizable to other datasets. For this experiment, we focused on part of the training images from the 3D-OCT-1000 dataset, as it contains more images than the other two datasets. Additionally, the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) for all these additional datasets is higher than that of SS-OCT, resulting in clearer retina structures compared to the low-SNR SS-OCT images.

The primary differences between the HCIRAN and 3D-OCT-1000 datasets lie in image size and lamination. To ensure consistency, we first adjusted the histogram of the HCIRAN dataset to match that of the 3D-OCT-1000 dataset by randomly selecting images from the latter. Next, we generated noise based on the histogram of 3D-OCT-1000 and added it to the resized, histogram-matched HCIRAN images to create noisy samples similar to those in the 3D-OCT-1000 dataset.

The first stage of training was performed on pairs of noisy and augmented HCIRAN images, while the second phase involved training on pairs of 3D-OCT-1000 images and their denoised PCA versions. Since the SNR of 3D-OCT-1000 data is higher than that of SS-OCT and has fewer B-scans per volume, we preserved 70% of the PCA components. The Bioptigen and A2A datasets were used solely for evaluation purposes. 3D-OCT-1000 dataset consists of 33,314 image B-scans from 984 OCT volumes. From this dataset, 100 subjects are randomly selected for training, and this selection remain similar for all comparative methods.

D. Hyperparameter tuning

As described earlier, the pretraining phase for SDNet was conducted on the HCIRAN dataset, producing the pretrained weight set \(\:{W}_{h}\). In parallel, training the network on the SS-OCT dataset resulted in a separate set of trained weights \(\:{W}_{s}\). Given that the first stage of training has access to noise-free images, it enhances image contrast, while the second stage, focused on SS-OCT, emphasizes fidelity to the specific texture of SS-OCT data.

To balance smoothness with texture preservation, we apply a weighted average of these two sets of weights, allowing SDNet to achieve an optimal blend of noise reduction and texture retention. In the current setup, SDNet uses a final weight setting defined as \(\:{W}_{final}=0.9{W}_{s}+0.1{W}_{h}\). Figure 7 visualizes the impact of adjusting this weight mix on the denoising outcomes, illustrating the trade-off between smoothing and texture detail.

E. Comparison methods

To evaluate the denoising performance of the proposed method, it is compared with several established approaches. These methods include both model-driven and data-driven approaches, chosen to represent different strategies and techniques in image denoising.The model-driven methods include:

-

Total generalized variation decomposition (TGVD): A variational denoising technique using second-order total generalized variation for structured noise reduction.

-

BM3D: A widely used general-purpose denoising algorithm based on block matching18.

-

BM4D: Newly modified version of BM3D19.

-

Weighted nuclear norm minimization (WNNM): A convex relaxation of low-rankness constrained optimization of OCT image denoising 50.

-

Domain-aware recurrent neural network with generative adversarial network (DARG): A patch-based RNN-GAN framework designed for few-shot supervised OCT noise reduction, leveraging domain adaptation principles to improve speckle suppression while maintaining structural integrity 51.

-

• GT-SC-GMM: OCT specific modeling for Gaussian transformation of data 38.

For data-driven approaches, we included:

-

Noise2Self: A general-purpose neural network for self-supervised denoising, adapted here for OCT images32.

-

MIMIC-Net: An OCT-specific data-driven deep learning model that mimics the GT-SC-GMM 38 model-driven approach to enhance the denoising performance 52.

-

Noise2Noise (N2N): A general method for self-supervised denoising28 used in 53.

-

Blind2UnBlind (B2U): Modified N2N method for OCT image denoising29.

By comparing SDNet with these established methods, we aim to provide a thorough evaluation of its performance across both general and OCT-specific denoising techniques.

F. Evaluation: enhancing clinical classification with multiple instance learning

To demonstrate how the proposed denoising and super-resolution methods enhance clinical utility, we used a classification framework based on multiple instance learning (MIL) 54. As shown in Fig. 8, this approach uses a pre-trained classifier for image vectorization and label aggregation among input vectors. Due to large number of B-scans for each individual, it needs to pre-tokenization for each B-scan.

Image tokenization using pre-trained InceptionV3: To address computational constraints and efficiently process patient-level data, a pre-trained on ImageNet data of InceptionV3 network was used for image tokenization. Each B-scan was turned into 2048-dimensional latent vector, preserving critical spatial and textural features. These vectors, shaped a 2D matrix, served as compact tokens for subsequent classification tasks, with N rows indicating number of B-scans.

Multiple instance learning for disease classification: Given the dataset’s individual-level labeling, an MIL strategy was employed: Healthy/DME/Non-DME Classification: tokenized B-scan were aggregated into a “bag of vectors” for each patient and processed using weighted attention mechanism (WAM). This approach linked diseased-specific labels to individual scans, emphasizing those most indicative of disease features, as shown in Fig. 8.

Results

Figure 9; Table 3 present a quantitative comparison of the proposed SDNet’s performance on the denoising task, as measured by the evaluation metrics, against other baseline methods. Notably, SDNet simultaneously addresses both denoising and super-resolution tasks, whereas the comparative methods only perform denoising on the full-resolution test datasets.

Comparison results among different methods and data sets. For datasets SS-OCT, 3D-OCT1000 and Bioptigen, we used 60 reference images and for A2A using 18 images for ROI selection. First 2 rows show value of metrics over each dataset. KID metric to show how much output of each method can be realistzic.

This added functionality highlights SDNet’s efficiency in enhancing image quality while preserving structural details. Figure 10 provides a visual comparison, illustrating the qualitative differences in output across methods, more samples are provided in Supplementary Table S1.

Table 4 summarizes the confusion matrix for the classification task, detailing the accuracy across the three classes: Healthy, DME, and Non-DME, in two scenarios: with or without image enhancement. Figure 11 shows receiver operating characteristic curve (ROC) and corresponding area under the curve (AUC) for comparison between two scenarios. Additionally, Table 5 presents the specific B-scans that were highlighted as relevant to the diseased condition through the weighted attention mechanism (WAM), further illustrating SDNet’s capacity to identify critical scans associated with disease indicators. According to the confusion matrix, the F1-score for binary classification (healthy/diseased) was 84.61% before denoising and 92.30% after denoising by SD-Net. For three-class classification, the F1-scores were 50% before denoising and 72.22% after denoising.

A. Inference time and processing

To evaluate the comparison methods, the N2N, N2S, and B2U networks adopt the same architecture as SDNet, but their training paradigms follow the protocols stated in their respective literature. All networks—SDNet, N2N, N2S, and B2U—are trained on the same fraction of training sets, with the exception of SDNet, which incorporates HCIRAN as part of its training strategy.

The comparison of denoising time depends on several factors, including image size, processor type, and implementation method. For BM3D and BM4D, we utilized their officially released code in Python. MimicNet, GT-SC-GMM, and TGVD were implemented using the authors’ provided code. Network models were evaluated on an Nvidia 1080 Ti graphics card, while model-based methods were implemented on a CPU. Figure 12 compares the inference times of™ the different methods.

Discussion

A. Analyzing evaluation metrics

The evaluation metrics for image enhancement in the literature of OCT denoising are divided into two categories: quantitative and qualitative measurements. The quantitative methods used in this study—CNR, MSR, TP, and PSNR—are all related to region of interest (ROI) selection. In these measurements, contrast is calculated as the difference between the mean intensities of two retinal layer regions, such as RNFL, GCL/IPL, or RPE. Noise parameters are determined using the Vitreous region. TP requires measurements before and after denoising. Despite these statements and their formulations in (1)-(4), these metrics alone cannot fully evaluate the denoising results. Figure 13 illustrates a case of a noisy SS-OCT sample, its denoised version by BM3D and SDNet, and a less noisy version. The right column shows the corresponding ROIs. As seen in this figure, the BM3D-denoised image loses most of the retinal texture, resulting in smooth regions for each layer and the Vitreous, leading to higher contrast but minimal texture preservation. Conversely, the less noisy version preserves texture better than other methods but remains noisy. This case demonstrates that these metrics, without visual investigation, cannot infer distinguishable results.

Visual results are valuable for comparison but require expert interpretation and are not feasible for the entire test dataset, only useful for a small fraction of data. In this study, we mimic expert evaluation using a trained classifier on SS-OCT data before and after denoising, to demonstrate how denoising can be useful and beneficial for machine evaluation in place of an expert.

It is crucial for a denoising method to produce images that remain realistic and similar to the OCT image domain. While this criterion traditionally requires human raters, it can be simulated using a large trained classifier such as the InceptionV3 55 model, as discussed in the literature model 56. This in-distribution distance can be evaluated using the kernel inception distance (KID), which calculates the kernel maximum mean discrepancy distance on the \(\:K\left(x,y\right)={\left(\frac{1}{2048}{x}^{T}y+1\right)}^{3}\). Here, the feature vector of InceptionV3 is 2048, and \(\:x\), \(\:y\) are feature vectors related to denoised OCT images and real OCT images, respectively. This metric evaluates how realistic and similar the denoised images are to the usual noise-free OCT dataset such as HCIRAN. For better evaluation, we used two KID metrics: one on InceptionV3 pretrained on the ImageNet dataset, commonly used in the literature to simulate human raters, and another using an autoencoder trained on HCIRAN, calculating KID on feature vectors from this autoencoder separately.

B. Discussion of results

This study introduces a hybrid model- and data-driven approach for denoising and super-resolution in low-SNR OCT imaging, leveraging both noise modeling and contextual image information. As illustrated in Fig. 7, the dual-training framework on separate datasets, combined with learned noise modeling, equips the network with adaptability and tunability. This flexibility empowers clinicians to adjust the contrast-texture balance to meet specific diagnostic needs, enhancing the model’s practical utility in diverse clinical scenarios. By increasing impact of the first phase of training in inference stage, the model results images with more contrast, while increasing impact of second phase of training leads to more texture preservation results.

In the second stage of training, we employed PCA as a coarse denoising method, followed by fine-tuning SDNet on the denoised images. The rationale for selecting PCA is multifaceted. Firstly, PCA’s fast implementation makes it suitable for use during the training process. Secondly, PCA does not require prior information for denoising. Thirdly, despite potential issues with blurring or shadowing effects, PCA effectively preserves image texture, unlike other denoising methods such as BM3D.

In our initial experiments, SDNet was trained solely using PCA denoising, without the initial training stage on the HCIRAN dataset. Under this setup, the network processes two inputs: the noisy image and the denoising rates. Figure 14 illustrates three samples from the SS-OCT dataset, demonstrating SDNet’s capability to denoise images at any desired rate within the range (0, 1). Denoising rates between 0.70 and 0.80 produced results comparable to those reported in Table 3.

The primary motivation for incorporating the first stage of training on the HCIRAN dataset is PCA’s limitation in generalizing denoising results across different datasets. While the SS-OCT dataset consists of 50–300 B-scans per volume, other datasets typically have fewer than 50 B-scans per volume. Consequently, in dense OCT volumes, PCA leads to increased blurring and shadowing effects. To address this issue, we augmented the dataset with initial noise-augmented training data (HCIRAN).

The comparative results presented in Figs. 9 and 10 highlight the advantages of integrating domain-specific knowledge into data-driven tasks. Our findings reveal that methods incorporating OCT-specific noise and structural features significantly outperform general-purpose model-driven methods. For example, while BM3D—a widely used general-purpose approach—delivers robust baseline results, GT-SC-GMM achieves superior performance by capitalizing on OCT-specific characteristics. Deep-learning-based models such as B2U and SDNet further distinguish themselves by producing noise-free images in a single prediction cycle, an essential feature for real-time applications in clinical workflows. In contrast, iterative methods like GT-SC-GMM and TGVD, while effective, lack the efficiency necessary for fast-paced diagnostic environments.

Metrics reported in Fig. 9 demonstrate SDNet’s capability to effectively suppress noise while maintaining consistent performance across evaluation criteria. Notably, methods like BM3D exhibit a “cartoonization” effect, where layer textures are overly smoothed, leading to reduced standard deviation but inflated MSR values. Conversely, approaches like N2N and N2S exhibit lower MSR values, indicative of residual noise within the retinal layers. SDNet strikes an optimal balance, preserving fine texture details without introduction artifacts, which is critical for retaining diagnostically relevant information.

Additionally, the results based on KID metric underscore SDNet’s ability to generate noise-free OCT images that are perceptually realistic. This metric, computed across all image outputs, further validates SDNet’s superiority in both denoising and super-resolution task in producing realistic images compared to other methods.

The classification outcomes in Table 4 further validate SDNet’s role as a robust tool for data cleaning and enhancement, especially for low-SNR SS-OCT devices. Remarkably, SDNet’s denoising and super-resolution capabilities effectively emphasize disease-specific features, as evidenced by its performance in identifying conditions such as diabetic macular edema (DME). Clinically, DME is characterized by fluid accumulation and macular swelling, often presenting as convex bulges rather than typical concave structure 58,59. Similarly, features associated with age-related macular degeneration (AMD), such as large confluent drusen and abnormal choroidal neovascularization, are effectively highlighted by SDNet. These pathological changes, including retinal edema and caviation in the Bruch’s membrane, align with the model’s capacity to detect subtle yet critical diseased-related pattern 60.

As shown in Table 5, SDNet frequently identifies subtle of macular disruptions, further underscoring its potential as a screening tool. Additionally, other marked B-sans often exhibit deformation below the RPE, drusen, detachments, or cavities above the RPE, providing clinicians with valuable insights for focused diagnostic evaluation.

In summary, SDNet, demonstrates exceptional adaptability and efficiency, balancing denoising and resolution enhancement while addressing clinically relevant features. This adaptability positions it as a promising tool for real-world applications, offering flexibility that benefits both current SS-OCT devices and other imaging vendors. By bridging model-driven and data-driven approaches, SDNet contributes to advancing OCT imaging and diagnostic capabilities.

C. Further discussion of denoising and super-resolution

Training SDNet for the dual tasks of denoising and super-resolution, by selectively omitting some columns of the image, enables the network to adapt to variations in OCT image structure. As an extended study, we evaluated SDNet’s performance solely on denoising and compared its results with those of super-resolution. In terms of qualitative measurements, SDNet performs similarly on both denoising and the combined tasks of denoising and super-resolution. This comparison is supported by the data presented in Table 6. Consequently, comparing SDNet’s results with other denoising methods is fair, given that SDNet demonstrates comparable performance in both tasks.

D. Further analysis on contrast-texture trade off and detection rates

As previously discussed, the two-stage training procedure of SDNet enables a contrast-texture trade-off. This is achieved by adjusting the training weights using a parameter \(\:\mu\:\in\:\left[\text{0,1}\right]\:\)as\(\:{W}_{s}*\mu\:+{W}_{h}*(1-\mu\:)\). The plot at the top of Fig. 15 illustrates the F1-score for two-class (Healthy vs. Diseased) and three-class (Healthy vs. DME vs. non-DME) classifications. The figure demonstrates that for binary classification, the maximum F1-score (96%) corresponds to a mixing parameter \(\:\mu\:=0.4\) or \(\:\mu\:=0.5\). In contrast, for three-class classification, the maximum F1-score is achieved with a mixing parameter \(\:\mu\:\ge\:0.9\). Using a middle value for the mixing parameter can improve the detection of Healthy and Diseased cases, while a higher mixing parameter is more effective in distinguishing diseased cases.

The bottom of Fig. 15 presents a sample B-scan identified by SDNet as a DME case. As shown, when SDNet preserves the image texture, a clinician can clearly observe a hole in the retina around the Macula region, indicating the possibility of DME in this subject. Additionally, with a mixing rate higher than 0.7, layers such as GCL and IPL become distinguishable. In contrast, with a mixing rate between 0.5 and 0.4, the middle layers are not distinguishable, and only the macular hole is visible. At lower mixing rates, only cavitation and edema in the Macula region are apparent.

Conclusion

This study focused on enhancing very low-SNR, low-resolution images captured by a custom-built swept-source OCT (SS-OCT) device developed at the Biomedical Engineering Department of Basel University.

We introduced a model-informed-data-driven approach, SDNet, designed for denoising and super-resolution tailored to the low-SNR dataset. Our results demonstrate that incorporating OCT-specific noise modeling with a deep-learning architecture yields substantial improvements in image quality, enhancing both contrast and texture preservation. However, while these results are promising, certain limitations remain that warrant further investigation.

The current model relies on PCA as a self-supervised denoising baseline, but PCA can introduce blurring effects, and selecting the optimal number of components for consistent denoising across all scans is challenging. Also, noise modeling and retina shape structure can be varied in different datasets, so the proposed method hardly adaptable on new datasets. As it can be seen the results of SDNet on SS-OCT dataset is better than SDNet results on other datasets, but still comparable by other methods. This limitation highlights the need for more sophisticated priors tailored to OCT images. Future work could explore alternative OCT-specific priors—such as Bessel K-form (BKF) or symmetric α-stable models, which have shown potential in existing literature13,22,37—to create a fully self-supervised framework with improved fidelity and adaptability. While the classification results gain more specificity on Healthy detection, but this work didn’t focus on classification. Then, more exploration on robust classifications can be beneficial. Another view for future work, we may plan to extend our study by incorporating OCT angiography (OCTA) data, which is currently unavailable in our datasets. While our comparison with methods such as N2N, N2S, and B2U have provided valuable insights using OCT data alone, a self-supervised approach like SSN2V that leverages both OCT and OCTA has the potential to further enhance denoising performance. Integrating OCTA could open new avenues for improving image quality and diagnostic accuracy in fast 4D-OCT, and will be an important direction for subsequent studies7.

In conclusion, while SDNet presents a compelling solution for SS-OCT image enhancement, further refinement with OCT-specific priors could make this method more robust, adaptable, and ultimately beneficial for clinical applications.

References

Drexler, W. & Fujimoto, J. State-of-the-art retinal optical coherence tomography. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 27, 45–88 (2008).

Srinivasan, P. P. et al. Fully automated detection of diabetic macular edema and dry age-related macular degeneration from optical coherence tomography images. Biomed. Opt. Express 5, 3568 (2014).

Chiu, S. J. et al. Validated Automatic Segmentation of AMD Pathology Including Drusen and Geographic Atrophy in SD-OCT Images. Investigative Opthalmology & Visual Science 53, 53 (2012).

Ashtari, F. et al. Optical Coherence Tomography in Neuromyelitis Optica spectrum disorder and Multiple Sclerosis: A population-based study. Multiple Sclerosis and Related Disorders 47, 102625 (2021).

Khodabandeh, Z. et al. Discrimination of multiple sclerosis using OCT images from two different centers. Multiple Sclerosis and Related Disorders 77, 104846 (2023).

Bai, T. et al. A novel Alzheimer’s disease detection approach using GAN-based brain slice image enhancement. Neurocomputing 492, 353–369 (2022).

Schottenhamml, J. et al. SSN2V: unsupervised OCT denoising using speckle split. Sci. Rep. 13, 10382 (2023).

Shi, F. et al. DeSpecNet: a CNN-based method for speckle reduction in retinal optical coherence tomography images. Phys. Med. Biol. 64, 175010 (2019).

Gour, N. & Khanna, P. Speckle denoising in optical coherence tomography images using residual deep convolutional neural network. Multimed Tools Appl 79, 15679–15695 (2020).

Devalla, S. K. et al. A Deep Learning Approach to Denoise Optical Coherence Tomography Images of the Optic Nerve Head. Sci Rep 9, 14454 (2019).

Halupka, K. J. et al. Retinal optical coherence tomography image enhancement via deep learning. Biomed. Opt. Exp. BOE 9, 6205–6221 (2018).

Mullissa, A. G., Marcos, D., Tuia, D., Herold, M. & Reiche, J. deSpeckNet: Generalizing Deep Learning-Based SAR Image Despeckling. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 60, 1–15 (2022).

Samieinasab, M., Amini, Z. & Rabbani, H. Multivariate Statistical Modeling of Retinal Optical Coherence Tomography. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 39, 3475–3487 (2020).

Wang, M. et al. Semi-Supervised Capsule cGAN for Speckle Noise Reduction in Retinal OCT Images. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 40, 1168–1183 (2021).

Guo, Y. et al. Structure-aware noise reduction generative adversarial network for optical coherence tomography image. in Ophthalmic Medical Image Analysis (eds. Fu, H., Garvin, M. K., MacGillivray, T., Xu, Y. & Zheng, Y.) 9–17 (Springer, 2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-32956-3_2.

Ma, Y. et al. Speckle noise reduction in optical coherence tomography images based on edge-sensitive cGAN. Biomed. Opt. Exp. BOE 9, 5129–5146 (2018).

Yu, A., Liu, X., Wei, X., Fu, T. & Liu, D. Generative adversarial networks with dense connection for optical coherence tomography images denoising. In 2018 11th International Congress on Image and Signal Processing, BioMedical Engineering and Informatics (CISP-BMEI). 1–5 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1109/CISP-BMEI.2018.8633086.

Chong, B. & Zhu, Y. K. Speckle reduction in optical coherence tomography images of human finger skin by wavelet modified BM3D filter. Optics Communications 291, 461–469 (2013).

Maggioni, M., Katkovnik, V., Egiazarian, K. & Foi, A. Nonlocal transform-domain filter for volumetric data denoising and reconstruction. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 22, 119–133 (2013).

Kafieh, R., Rabbani, H. & Selesnick, I. Three Dimensional Data-Driven Multi Scale Atomic Representation of Optical Coherence Tomography. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 34, 1042–1062 (2015).

Tajmirriahi, M., Amini, Z., Hamidi, A., Zam, A. & Rabbani, H. Modeling of Retinal Optical Coherence Tomography Based on Stochastic Differential Equations: Application to Denoising. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 40, 2129–2141 (2021).

Tajmirriahi, M., Amini, Z. & Rabbani, H. Local Self-Similar Solution of ADMM for Denoising of Retinal OCT Images. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 73, 1–8 (2024).

Amini, Z., Rabbani, H. & Selesnick, I. Sparse Domain Gaussianization for Multi-Variate Statistical Modeling of Retinal OCT Images. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 29, 6873–6884 (2020).

Jorjandi, S., Rabbani, H., Kafieh, R. & Amini, Z. Statistical modeling of optical coherence tomography images by asymmetric normal Laplace mixture model. In Proceedings of the Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society, EMBS. 4399–4402 (Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc., 2017). https://doi.org/10.1109/EMBC.2017.8037831.

Nienhaus, J. et al. Live 4D-OCT denoising with self-supervised deep learning. Sci. Rep. 13, 5760 (2023).

Hu, D., Tao, Y. K. & Oguz, I. Unsupervised denoising of retinal OCT with diffusion probabilistic model. In Medical Imaging 2022: Image Processing. Vol. 12032. 25–34 (SPIE, 2022).

Li, S., Higashita, R., Fu, H., Yang, B. & Liu, J. Score Prior Guided Iterative Solver for Speckles Removal in Optical Coherent Tomography Images. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 29, 248–258 (2025).

Lehtinen, J. et al. Noise2Noise: Learning image restoration without clean data. In 35th International Conference on Machine Learning, ICML 2018 7, 4620–4631 (2018).

Yu, X. et al. Self-supervised Blind2Unblind deep learning scheme for OCT speckle reductions. Biomed. Opt. Exp. BOE 14, 2773–2795 (2023).

Song, T.-A., Yang, F. & Dutta, J. Noise2Void: unsupervised denoising of PET images. Phys. Med. Biol. 66, 214002 (2021).

Prakash, M., Lalit, M., Tomancak, P., Krul, A. & Jug, F. Fully Unsupervised Probabilistic Noise2Void. In Proceedings - International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging 2020, 154–158 (2020).

Batson, J. & Royer, L. Noise2Self: Blind denoising by self-supervision. In Proceedings of the 36th International Conference on Machine Learning. 524–533 (PMLR, 2019).

Kafieh, R., Rabbani, H., Hajizadeh, F., Abramoff, M. D. & Sonka, M. Thickness Mapping of Eleven Retinal Layers Segmented Using the Diffusion Maps Method in Normal Eyes. Journal of Ophthalmology 2015, 1–14 (2015).

Available Datasets | Medical Image and Signal Processing Research Center, ICIP2024-VIP CUP-dataset. https://misp.mui.ac.ir/en/MISPDataBase.

Zhang, Y. et al. A Poisson-Gaussian denoising dataset with real fluorescence microscopy images. in 2019 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR). 11702–11710 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPR.2019.01198.

Hu, Y., Ren, J., Yang, J., Bai, R. & Liu, J. Noise reduction by adaptive-SIN filtering for retinal OCT images. Sci Rep 11, 19498 (2021).

Jorjandi, S., Amini, Z., Samieinasab, M. & Rabbani, H. Retinal OCT image denoising based on adaptive bessel K-form modeling. In 2023 30th National and 8th International Iranian Conference on Biomedical Engineering (ICBME). 376–380 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1109/ICBME61513.2023.10488570.

Amini, Z. & Rabbani, H. Optical coherence tomography image denoising using Gaussianization transform. J. Biomed. Opt. 22, 1 (2017).

Rabbani, H., Sonka, M. & Abramoff, M. D. Optical Coherence Tomography Noise Reduction Using Anisotropic Local Bivariate Gaussian Mixture Prior in 3D Complex Wavelet Domain. Int. J. Biomed. Imaging 2013, 1–23 (2013).

Ronneberger, O., Fischer, P. & Brox, T. U-Net: Convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation. in Lecture Notes in Computer Science (including subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence and Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics) Vol. 9351. 234–241 (Springer, 2015).

Ye, J. C., Han, Y. & Cha, E. Deep Convolutional Framelets: A General Deep Learning Framework for Inverse Problems. SIAM J. Imaging Sci. 11, 991–1048 (2018).

He, K., Zhang, X., Ren, S. & Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR). Vol. 2016-Decem. 770–778 (IEEE, 2016).

Abraham, N. & Khan, N. M. A novel focal Tversky loss function with improved attention U-Net for lesion segmentation. In 2019 IEEE 16th International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging (ISBI 2019). Vol. 2019. 683–687 (IEEE, 2019).

Liu, H., Liao, P., Chen, H. U. & Zhang, Y. I. ERA-WGAT: Edge-enhanced residual autoencoder with a window-based graph attention convolutional network for low-dose CT denoising. Biomed. Opt. Exp. 13(11), 5775–5793 (2022).

Kingma, D. P. & Ba, J. Adam: A method for stochastic optimization. In 3rd International Conference on Learning Representations, ICLR 2015 - Conference Track Proceedings (2014).

Wang, Z., Bovik, A. C., Sheikh, H. R. & Simoncelli, E. P. Image quality assessment: from error visibility to structural similarity. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 13, 600–612 (2004).

Jayasumana, S. et al. Rethinking FID: Towards a Better Evaluation Metric for Image Generation. 9307–9315 (2024).

Ghaderi Daneshmand, P. & Rabbani, H. Total variation regularized tensor ring decomposition for OCT image denoising and super-resolution. Comput. Biol. Med. 177, 108591 (2024).

Fang, L. et al. Fast Acquisition and Reconstruction of Optical Coherence Tomography Images via Sparse Representation. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 32, 2034–2049 (2013).

Gu, S., Zhang, L., Zuo, W. & Feng, X. Weighted nuclear norm minimization with application to image denoising. in 2014 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. 2862–2869 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPR.2014.366.

Pereg, D. Domain-Aware Few-Shot Learning for Optical Coherence Tomography Noise Reduction. MDPI Journal of Imaging 9, 237 (2023).

Tajmirriahi, M., Kafieh, R., Amini, Z. & Rabbani, H. A Lightweight Mimic Convolutional Auto-Encoder for Denoising Retinal Optical Coherence Tomography Images. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 70, 1–8 (2021).

Li, Y., Fan, Y. & Liao, H. Self-supervised speckle noise reduction of optical coherence tomography without clean data. Biomed. Opt. Exp. BOE 13, 6357–6372 (2022).

Ilse, M., Tomczak, J. & Welling, M. Attention-based deep multiple instance learning. In Proceedings of the 35th International Conference on Machine Learning. 2127–2136 (PMLR, 2018).

Szegedy, C., Vanhoucke, V., Ioffe, S., Shlens, J. & Wojna, Z. Rethinking the Inception Architecture for Computer Vision. 2818–2826 (2016).

Bińkowski, M., Sutherland, D. J., Arbel, M. & Gretton, A. Demystifying MMD GANs. arXiv e-prints Preprint https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1801.01401 (2018).

Sarafijanovic-Djukic, N. & Davis, J. Fast distance-based anomaly detection in images using an inception-like autoencoder. In Discovery Science (eds. Kralj Novak, P., Šmuc, T. & Džeroski, S.). 493–508 (Springer, 2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-33778-0_37.

Yanoff, M., Fine, B. S., Brucker, A. J. & Eagle, R. C. Pathology of human cystoid macular edema. Surv. Ophthalmol. 28, 505–511 (1984).

Otani, T., Kishi, S. & Maruyama, Y. Patterns of diabetic macular edema with optical coherence tomography. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 127, 688–693 (1999).

Cheung, C. M. G. et al. Myopic Choroidal Neovascularization: Review, Guidance, and Consensus Statement on Management. Ophthalmology 124, 1690–1711 (2017).

Zarbin, M. A. Current Concepts in the Pathogenesis of Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Arch. Ophthalmol. 122, 598–614 (2004).

Guymer, R., Luthert, P. & Bird, A. Changes in Bruch’s membrane and related structures with age. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 18, 59–90 (1999).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by the Isfahan University of Medical Sciences under Grant number 3401797.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SR, AH, and AA implemented the method, SR also wrote main manuscript, MP provided clinical discussion, MT and FS applied methodological supports, HR was supervisor. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rakhshani, S., Arbab, A., Habibi, A. et al. Self-supervised model-informed deep learning for low-SNR SS-OCT domain transformation. Sci Rep 15, 17791 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-02375-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-02375-3