Abstract

To delineate Gpr109A’s role and mechanisms in modulating the immune microenvironment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Employing Gpr109A-knockout mice and in vitro co-cultures of hepatocellular carcinoma cells with macrophages, this study utilized a suite of techniques, including lentiviral vectors for stable cell line establishment, Western blotting, cell scratch, CCK-8, transwell assays, flow cytometry, immunohistochemistry and phagocytosis assay to assess various cellular behaviors and interactions. Gpr109A deletion markedly reduced the oncogenic potential of H22 cells, both in vivo and when co-cultured with knockout macrophages, impairing their growth, invasion, and migration. In Gpr109A-knockout macrophages, an upregulation of MerTK and a reduction in immunosuppressive cytokine release were observed, indicating a shift towards an M2c macrophage phenotype. This shift is linked to Gpr109A’s role in promoting protease overexpression and inhibiting SHP2 phosphorylation, crucial for enhancing cancer cell proliferation and invasiveness. Gpr109A significantly influences macrophage polarization to the M2c type, augmenting hepatocellular carcinoma cell aggressiveness.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The immunological microenvironment of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) comprises diverse immune cells, cytokines, and immune-related molecules, including T cells, B cells, natural killer cells, macrophages, and dendritic cells1. These cells exhibit dual roles in cancer progression, inhibiting tumor growth by eliminating immunogenic cells while also facilitating immune evasion by modulating tumor immunogenicity2. The cytokines produced and secreted by immune cells, such as Interleukin-10 (IL-10), Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha (TNFα), etc., orchestrate inflammation and immune responses within the tumor microenvironment3,4,5. HCC cells exploit immune checkpoints, such as PD-1 and PD-L1, to evade immune surveillance6,7; And mechanisms within the microenvironment may induce immune tolerance8,9.

Niacin (Vitamin B3) activates the Gpr109A receptor, promoting GRK phosphorylation and PKA overexpression10,11,12,13,14,15; This overexpression of PKA stimulates an increase in PPARγ levels16,17. PPARγ activates the macrophage receptor MerTK, inhibiting M1 macrophage polarization while promoting M2 polarization18,19,20,21,22,23,24. MerTK activation enables TAM receptors to recognize phosphatidylserine on apoptotic cells, facilitating phagocytosis via ligands Gas6 and Protein S, leading to M2C macrophage polarization25,26,27,28.

MerTK also enhances STAT3 and STAT6 phosphorylation, increasing immunosuppressive cytokines like IL-10 and TGF-β29,30,31. The activation of STAT3 can result in a marked increase in the expression levels of IL-10 and PD-L132,33,34; The elevation of IL-10 reflects a trend towards M2 macrophage polarization. M2 macrophages are a class of macrophages classified according to their functional and phenotypic characteristics, and they are commonly associated with tissue repair, immunomodulation and anti-inflammatory responses. Polarisation of M2 macrophages can be further subdivided into several subtypes, the most common of which include M2a, M2b, and M2c, each of which has its own distinctive activation pathways and functional characteristics. M2a macrophages are primarily involved in tissue repair and remodelling that promotes fibrosis and wound healing. M2b macrophages have a strong immunomodulatory capacity and are able to induce T-cell activation through the secretion of cytokines, such as IL-1, IL-6, and TNF-alpha. M2c Macrophages are mainly involved in suppressing inflammatory responses and promoting tissue repair. They inhibit the activation of inflammatory cells, promote phagocytosis and removal of apoptotic cells, and reduce tissue damage by secreting anti-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-10 and TGF-β33,34.

HCC cells activate IRE1a under endoplasmic reticulum stress via PD-1/PD-L1 binding, promoting aberrant protein folding35,36. IRE1a activation enhances cellular adaptation and survival, stimulating tissue protease secretion, which degrades extracellular matrix, promotes angiogenesis, and facilitates immune evasion, aiding HCC growth and metastasis37,38. Phosphorylation of STAT3 can promote p53-mediated suppression of SHP2 expression, thereby inhibiting SHP2’s transcriptional activity towards STAT3 and STAT639,40,41; Macrophages engulf apoptotic tumor cells via MerTK, with Gas6 and Protein S binding TAM receptors, promoting dimerization and downstream signaling42,43,44,45.

Through Efferocytosis, the Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptors (PPARs) can regulate gene expression involved in Efferocytosis, such as the activation of the MERTK nuclear receptor. The nuclear receptor also regulates gene expression related to M2 macrophage polarization, thereby promoting macrophage polarization towards the M2 type and enhancing immune tolerance of hepatocellular carcinoma cells46,47. SHP2 inhibits apoptotic cell phagocytosis by dephosphorylating MerTK48,49, releasing double-stranded DNA fragments into macrophages via P2 × 7R. cGAS binds to these cytoplasmic double-stranded DNA fragments, activating cyclic GMP-AMP synthase (cGAS), producing 2’3’ cyclic GMP-AMP (cGAMP), a second messenger for activating the ER adaptor protein STING50,51. STING recruits EGFR, undergoes autophosphorylation, and relocates to the ER-Golgi intermediate compartment, activating IRF3 and NF-kB to induce IFNβ expression, promoting immune activation52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59. However, the mechanisms and impact of Gpr109A absence in HCC macrophages on tumor proliferation, invasion, and migration remain unclear.

Experimental methodology

Experimental animals

Mice purchased from HSB Co. Gpr109A WT−/− mice were engineered against a C57BL6 backdrop. These mice were obtained through the crossbreeding of Gpr109A WT−/− female and male mice, resulting in the production of both Gpr109A WT mice and Gpr109A−/− mice. Mouse monocyte-macrophage leukemia cells (RAW264.7 cells) and mouse hepatocellular carcinoma cells (H22 cells and Hepa1-6 cells) were acquired from Wuhan Procell Biotechnology Co., Ltd. A statement that all methods are carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Lentivirus construction

The coding sequence (CDS) region of Gpr109A was retrieved from NCBI, along with transcript numbers. Utilizing pSIH1-H1-copGFP-T2A-Puro as a vector, appropriate shRNAs targeting mouse Gpr109A gene knockdown were designed via the GPP Web Portal. The synthesized shRNAs and overexpression of lentiviral sequences were annealed and ligated into the pLKO_005 vector, then inserted into the pHAGE-CD19 vector through PCR amplification and T4 enzyme ligation. The assembled pHAGE-CD19, psPAX2, and pMD2.G plasmids were co-transfected into 293T cells using Lipo8000. The medium was switched to DMEM containing 10% FBS the following day. Cell supernatant was collected 72 h post-transfection, centrifuged at 3000 rpm at 4 °C for 15 min, and the viral fluid was stored at -80 °C. 24 h before infection, H22 cells were seeded at a density of 10^5 cells into 24-well plates. Appropriate viral concentration gradients were set, and the plates were incubated at 37 °C in a serum-free medium. Post-infection, cells underwent selection with puromycin for 14 days. Cell lines within 20 passages were used for subsequent experiments, yielding RAW264.7 cell LV-NC-KD, RAW264.7 cell LV-Gpr109A-KD stable cell lines, RAW264.7 cell LV-NC-OE and RAW264.7 cell Gpr109A-OE stable cell lines, and primary macrophages Gpr109A WT-NC and Gpr109A-OE stable cell lines.

Similarly, the CDS region for MerTK was sourced from NCBI, and its transcript number was identified. The full-length gene fragment of MerTK was synthesized and incorporated into the pHAGE-CD19 vector using the same procedure, followed by co-transfection into 293T cells. Two types of lentiviruses, LV-NC and LV-MerTK-OE, were thus obtained18,19,20.

Macrophage extraction

After the mice were anaesthetised using 3% isoflurane gas, the mice were euthanised using CO2 and placed in a beaker containing an adequate amount of 75% ethanol for 5 min for soaking and sterilisation, and the soaked animals were blotted with paper to remove excess alcohol. The hind limbs were removed with scissors along the greater trochanter at the root of the lower thigh, the muscle tissue was removed and placed in a petri dish containing 75% ethanol for 5 min, and the petri dish was replaced with a new one with 75% ethanol and transferred into an ultra-clean table. The ethanol-soaked leg bones were transferred to cold PBS for soaking to wash away the ethanol on the surface of tibia and femur, and this process could be repeated 3 times. Separate the cleaned femur and tibia and cut the ends of the femur and tibia with scissors, respectively, and blow the bone marrow out of the femur and tibia using a 1mL syringe to draw up cold induction medium, and repeat this process for 3 times until no obvious red colour can be seen inside the leg bone. The medium containing bone marrow cells was blown repeatedly with a 5mL pipette gun to disperse the cell clumps, and then the cells were sieved using a 70 μm cell filter, transferred to a 15mL centrifuge tube, centrifuged at 1500 rpm/min for 5 min, the supernatant was discarded, and resuspended by adding erythrocyte lysates and left to stand for 5 min, and then centrifuged at 1500 rpm/min for 5 min, and the supernatant was discarded to be resuspended with the cold configured bone marrow The supernatant was discarded and resuspended with cold bone marrow cell induction medium, and the plates were spread. The medium was not changed during the cell culture period, half of the bone marrow macrophage induction medium was changed after the third day of culture, and the whole medium was changed on the fifth day, and the cells could be used for subsequent experiments on the seventh day25,26.

Co-culture of tumor-associated macrophages

RAW264.7 cells were centrifuged at 200×g for 10 min, and the cell suspension was adjusted to a concentration of 1 × 10^6 cells/100 µL (minimum 100 µL) for viral infection. The diluted cell suspension was then transferred back to the prepared 12-well plates. Macrophage differentiation was induced using M-CSF (100 ng/ml).

5 × 10^5 engineered mouse hepatocellular carcinoma cells (H22 cells and Hepa1-6 cells) were seeded at the bottom of 6-well plates, and 5 × 10^5 RAW264.7 cells and primary macrophages were seeded at the bottom of the Transwell chambers, respectively. These cells were cultured under standard adherence conditions. After washing twice with PBS, the chambers were combined with the cell culture plates containing cells to establish a bi-layered co-culture system. Cultivation was carried out for 48 h in a complete medium formulated without exosomes29,30,31.

Immunohistochemical staining

Tumour tissue sections were dewaxed by xylene and washed with PBS after gradient alcohol treatment. Endogenous peroxidase was inhibited by 3% hydrogen peroxide. Antigen repair was performed under high temperature and high pressure for 3 min, and the sections were naturally cooled to room temperature. The sections were blocked with 10% normal goat serum at room temperature, and the primary antibody was added and incubated at room temperature for 3 h. After washing with PBS three times, the sections were incubated with goat anti-rabbit lgG in a constant temperature box at 37℃ for 0.5 h. The sections were washed with PBS three times, treated with DAB chromogen for display, and stained with hematoxylin. The sections were then dehydrated with gradient alcohol, made transparent with xylene, and blocked with neutral resin. The results of the staining were observed under a microscope33,34.

Scratch assay

24 h after co-culturing, the experiment was conducted. Equidistant horizontal lines were drawn on the back of 6-well plates using a non-toxic, erasable marker method such as fluorescent marking. Log-phase H22 cells and Hepa1-6 cells were seeded onto 6-well plates, and upon reaching 80% confluence, the next step was performed. A vertical scratch was made along the marked lines using a 200µL plastic pipette tip. The cell monolayer was washed with PBS or another suitable cell culture medium to remove cells suspended in the medium post-scratch. The cells were then treated according to different experimental groups. An inverted microscope was used to observe and photograph the cells at 0 and 48 h post-scratch36,37,38,39.

Transwell assay

The cell invasion assay was conducted using a Transwell chamber with a 24-well plate and a polyethylene terephthalate membrane with 8.0 μm pores. H22 cells and Hepa1-6 cells were seeded at a density of 1 × 10^5 cells/well in 100µL of serum-free medium in the upper chamber, while 600µL of complete growth medium was added to the lower chamber as a chemoattractant. Following incubation at 37℃ for 48 h, the residual cells on the membrane surface were removed using a cotton swab. The migrated cells on the underside were fixed with a 4% paraformaldehyde solution and stained with a 0.1% crystal violet staining solution. Subsequently, the cells were imaged using an inverted fluorescence microscope equipped with a filter. The cell migration assays were performed without polyethylene terephthalate membranes, and other operations were carried out as described above36,37,38,39.

CCK-8 assay

The cell supernatant was aspirated, and 300 ml of PBS pre-warmed to 37℃ was added per tube and resuspended. 100 µL from each of the three tubes was added to the 96-well plate, and CCK-8 was added at 10 µL/well. The OD450 value was detected after incubation at 37℃ for 1 h38,39.

Flow cytometry

The podocytes were digested with trypsin-EDTA digestion solution (0.25%), centrifuged at room temperature (1000 r/min, 5 min), and the supernatant was discarded. The cells were washed with 1xPBS, and approximately 1 × 10^6 H22 cells and Hepa1-6 cells were collected in each group. 500 µL of binding buffer was added, and the cells were blown and mixed evenly. 5 µL of PI and Annexin V-FITC were added respectively, and the mixture was allowed to stand in the dark for 10 min. Apoptosis of H22 cells and Hepa1-6 cells was detected by flow cytometry41,42.

Western blot

For Western blot analysis, tissue and cell samples were washed twice with PBS or another suitable buffer solution, scraped from the culture dishes, and collected by centrifugation. The cell samples were treated with RIPA lysis buffer. Depending on the experimental requirements, 80 to 120 µg of total protein was extracted from each cell and combined with 6× protein loading buffer, followed by boiling at 95℃. The samples were processed by SDS-PAGE electrophoresis and transferred onto PVDF membranes. Specific antibodies were incubated using concentrations recommended by the supplier. Antibodies against PKA, PPARγ, MerTK, p-STAT3, p-STAT6, IL-10, Cathepsin K, Cathepsin S, CD163, CD206, CCL18, IRE1α, PD-L1, P53, p-SYK, SHP2, IFN-β, and GAPDH, all sourced from designated suppliers, were employed. The samples were developed using ECL technology with reagents such as Amersham ECL Prime and exposed using appropriate photographic films. Quantitative analysis was performed using software like ImageJ, and statistical evaluations were conducted42.

Phagocytosis assay

For the phagocytosis assay using fluorescent microspheres, 7.0 × 10^4 cells/cm^2 were seeded in each well. The cells were incubated at 37℃ and 5% CO2 for 24 h until they reached a density of 50–70%. The culture medium was removed, and the GFP fluorescent latex beads were washed with distilled water and centrifuged at 10,000 g for 8 min at room temperature. The beads were resuspended in a solution containing 3% BSA and 25 mM Na3PO4 (pH 6.0) and incubated in a bath sonicator at room temperature for 15 min to ensure the beads remained monodispersed in BSA. The beads were washed once with a medium containing 5% FBS. The bead suspension was adjusted to a concentration of 2.0% with medium and stored in the dark at 4℃. For experiments using 12-well plates, 6 µl of bead stock solution was added to 0.4 ml of medium per well. Each well was washed twice with PBS, and the working solution of the beads (1 ml for 6-well plates and 0.4 ml for 12-well plates per well) was added. The cells were incubated at 37℃ in the dark for 80–120 min. The working solution of the beads was removed, and each well was washed three times with PBS to remove excess beads. After washing, the cells were stained with DAPI and the slides were sealed with glycerol. Images were captured using an Olympus confocal microscope43.

Bioinformatics analysis

RNAseq data of TCGA-LIHC (hepatocellular hepatocellular carcinoma) were downloaded from the TCGA database, and the correlation between SHP2 (PTPN11) and IRE1α (XBP1) was analyzed by Spearman analysis.

Statistical analysis

For statistical analysis, Graph Pad Prism 9.0 software was used. Quantitative data were represented as mean ± standard deviation. The measured data were tested using normal and chi-square tests, and one-way ANOVA was used to compare multiple groups after the data conformed to the normal distribution. The Tukey test was used to compare two groups. Statistical significance was considered at P < 0.05.

Results

Gpr109A−/− mice exhibited a marked reduction in the tumorigenicity of H22 cells in the hepatocellular carcinoma immune microenvironment through the PKA/p-PPARγ/MerTK pathway

After cultivating H22 cells to adjust the cell concentration to 5 × 10^7/ml, inject 0.1 ml of the cell suspension subcutaneously into the backs of both Gpr109A WT and Gpr109A−/− mice, with each group comprising six mice. Upon feeding for three weeks, a significant decrease in tumour weight and tumour volume was observed in Gpr109A−/− mice compared to Gpr109A WT mice (Fig. 1A). Moreover, immunohistochemical staining showed that the relative protein expression of Gpr109A was significantly higher in Gpr109A WT mice than in Gpr109A−/− mice (Fig. 1B).

Effects of Gpr109A Deletion and LV-Gpr109A-KD on H22 Tumor Growth and Protein Expression in Mice. (A) Comparison of tumour weight and tumour volume in Gpr109A wild type (WT) and Gpr109A knockout (−/−) mice 3 weeks after subcutaneous injection of H22 cells. (B) Immunohistochemical staining to detect levels of Gpr109A. Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation; (C) Comparison of tumor volume and weight in nude mice injected with H22 cells co-cultured with LV-NC-KD or LV-Gpr109A-KD RAW264.7 cells. (D) Immunohistochemical staining to detect levels of Gpr109A; (E) Western Blot analysis showing expression levels of PKA, p-PPARγ, and MerTK proteins in LV-NC-KD and LV-Gpr109A-KD RAW264.7 cells co-cultured with H22 cells. GAPDH as control protein; Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation; N = 6; **P < 0.01.

Cultivate the stable cell lines LV-NC-KD and LV-Gpr109A-KD of RAW264.7 cells under the Transwell chambers, and H22 cells under the six-well plates, co-culturing for 96 h before injecting 1 × 10^7 cells from co-cultures with either LV-NC-KD RAW264.7 cells or LV-Gpr109A-KD RAW264.7 cells subcutaneously into the right side of nude mice. After feeding for three weeks, a notable reduction in tumor volume and weight was found in H22 cells co-cultured with LV-Gpr109A-KD RAW264.7 cells compared to those co-cultured with LV-NC-KD RAW264.7 cells (Fig. 1C). Moreover, immunohistochemical staining showed that the relative protein expression of Gpr109A was significantly higher in LV-NC-KD RAW264.7 cells than in LV-Gpr109A-KD RAW264.7 cells (Fig. 1D).

Concurrently, total protein extraction from co-cultured LV-NC-KD RAW264.7 cells and LV-Gpr109A-KD RAW264.7 cells followed by Western Blot analysis revealed a significant decrease in the expression levels of PKA, p-PPARγ, and MerTK in LV-Gpr109A-KD RAW264.7 cells compared to LV-NC-KD RAW264.7 cells (Fig. 1E).

Gpr109A induces the overexpression of cathepsins in M2c-type macrophages

The primary macrophages were then cultured beneath a Transwell apparatus, while H22 cells were cultured at the bottom of a six-well plate, creating a co-culture system of primary macrophages and hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Successful induction of macrophages was followed by treatment with 40µM Niacin for 24 h. The experiment was divided into four groups: Gpr109A WT DMSO, Gpr109A−/− DMSO, Gpr109A WT Niacin-treated, and Gpr109A−/− Niacin-treated. After 96 h of co-culture, total protein from the macrophages was extracted. Western Blot analysis revealed that compared to the Gpr109A WT DMSO group, the Gpr109A−/− DMSO group exhibited significantly lower levels of PKA, p-PPARγ, MerTK, p-STAT3, and p-STAT6. In contrast, the Gpr109A WT Niacin-treated group showed significantly increased levels of these proteins; no significant differences were observed between the Gpr109A−/− DMSO group and the Gpr109A−/− Niacin-treated group. This suggests that Niacin can influence the polarization state of macrophages by affecting the levels of p-STAT3 and p-STAT6 through the PKA/p-PPARγ/MerTK signaling pathway.

Furthermore, the expression levels of M2 macrophage markers and cathepsins were analyzed. Compared to the Gpr109A WT DMSO group, the Gpr109A−/− DMSO group showed significantly lower levels of IL-10, CD163, CD206, CCL18, TGF-β, Cathepsin K, Cathepsin S, and PD-L1. The Gpr109A WT Niacin-treated group exhibited significantly higher levels of these proteins. No significant differences were observed between the Gpr109A−/− DMSO group and the Gpr109A−/− Niacin-treated group, indicating that Gpr109A induces the overexpression of cathepsins in M2c-type macrophages (Fig. 2A,B).

Influence of Gpr109A and Niacin Treatment on Protein Expression in Primary Macrophages Co-cultured with H22 Cells. (A) Protein expression analysis of PKA, p-PPARγ, MerTK, p-STAT3 and p-STAT6 in Gpr109A WT and Gpr109A−/− primary macrophages with or without Niacin treatment; (B) Comparison of the expression levels of IL-10, TGF-β, Cathepsin K, Cathepsin S, CD163, CD206, CCL18, and PD-L1 in Gpr109A WT and Gpr109A−/− primary macrophages with or without Niacin treatment; (C) Comparison of the expression levels of PKA, p-PPARγ, MerTK, and IL-10 in primary macrophages from the Gpr109A WT DMSO group, Gpr109A−/− DMSO group, Gpr109A WT-NC DMSO group, and Gpr109A-OE DMSO group; GAPDH as control protein; Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation; N = 3; **P < 0.01; *P < 0.05.

Subsequently, western blot results showed that the relative protein expression levels of PKA, p-PPARγ, MerTK and IL-10 in the Gpr109A−/− DMSO group were significantly lower than those in the Gpr109A WT DMSO group. The relative protein expression levels of PKA, p-PPARγ, MerTK and IL-10 in the Gpr109A-OE DMSO group were significantly higher than those in the Gpr109A WT-NC DMSO group (Fig. 2C).

Cathepsins promote the migration and invasion of hepatocellular carcinoma cells

With the M2 pro-tumorigenic polarization state of macrophages established, its manifestation in cancer cells needed further determination and analysis. Scratch tests were performed using a previously established co-culture system of primary macrophages with H22 and Hepa1-6 cells, respectively. Compared to the Gpr109A WT DMSO group, the scratch distance significantly widened in the Gpr109A−/− DMSO group significantly narrowed in the Gpr109A WT Niacin-treated group, and widened in both the Gpr109A−/− DMSO group and the Gpr109A−/− Niacin-treated group; no significant differences were observed between the latter two groups.

Simultaneously, a Transwell assay was conducted with and without the addition of a matrix gel to assess cell migration and invasion. Compared to the Gpr109A WT DMSO group, the number of migrating and invading cells significantly decreased in the Gpr109A−/− DMSO group but significantly increased in the Gpr109A WT Niacin-treated group, the Gpr109A−/− DMSO group, and the Gpr109A−/− Niacin-treated group; no significant differences were noted between the last two groups (Fig. 3).

Effect of Gpr109A and Niacin Treatment on hepatocellular carcinoma Cell Migration and Invasion. (A) An increase in scratch distance indicates more significant cell migration. Emphasize the narrowed scratch distance in the Gpr109A WT Niacin-treated group compared to the widened distance in both Gpr109A−/− groups; (B) Significant increase in both migrating and invading cells in the Gpr109A WT Niacin-treated group, with the Gpr109A−/− groups showing similar levels to each other but decreased compared to the Gpr109A WT DMSO group; Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation; N = 3; **P < 0.01; *P < 0.05; nsP>0.05.

Gpr109A promotes proliferation and inhibits apoptosis of hepatocellular carcinoma cells

We then used CCK-8 assay and flow cytometry to detect proliferation and apoptosis of hepatocellular carcinoma cells, respectively. The OD values of the Gpr109A−/− DMSO group were significantly reduced compared to the Gpr109A WT DMSO group, but the OD values of the Gpr109A WT Niacin-treated group were significantly increased relative to those of the Gpr109A−/− DMSO group and the Gpr109A−/− Niacin-treated group; the latter there was no significant difference between the two groups.

The apoptosis rate was significantly increased in the Gpr109A−/− DMSO group compared to the Gpr109A WT DMSO group, but significantly reduced in the Gpr109A WT Niacin-treated group relative to the Gpr109A−/− DMSO group and the Gpr109A−/− Niacin-treated group; there was no significant difference between the latter two groups. there was no significant difference between the two groups (Fig. 4).

Effect of Gpr109A and Niacin Treatment on hepatocellular carcinoma Cell proliferation and apoptosis. (A) OD values were significantly increased in all Gpr109A WT Niacin-treated groups, and were similar in the Gpr109A−/− group, but decreased compared to the Gpr109A WT DMSO group; (B) Apoptosis rates were significantly reduced in both Gpr109A WT Niacin-treated groups, and were similar in the Gpr109A−/− group, but decreased compared with the Gpr109A WT DMSO group; Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation; N = 3; **P < 0.01; *P < 0.05; nsP>0.05.

And we set up LV-NC-OE group and Gpr109A-OE group to verify the effect of Gpr109A overexpression on the behavioural science of H22 cells and Hepa1-6 cells.The results of CCK-8 assay showed that the OD values of H22 cells and Hepa1-6 cells in Gpr109A-OE group were significantly higher than those in LV-NC-OE group at 72 h. In TCGA-LIHC data, the negative correlation between SHP2 (PTPN11) and IRE1α (XBP1) suggested a potential interaction between the two in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). SHP2 was an important signaling enzyme involved in a variety of biological processes, including cell proliferation, differentiation, and survival. Its aberrant expression in various tumors was closely associated with tumor development. IRE1α was a key component in the endoplasmic reticulum stress (ER stress) pathway, which regulated cellular responses to endoplasmic reticulum stress mainly through activation of XBP1. The negative correlation indicated that the activity of IRE1α may have been suppressed when the expression level of SHP2 was elevated, which may have been closely related to the microenvironment of hepatocellular carcinoma and its metabolic status. The results of cell scratch assay showed that the intercellular spacing distance of H22 cells and Hepa1-6 cells in Gpr109A-OE group were significantly lower than that of LV-NC-OE group at 48 h. The results of Transwell assay showed that the number of migrated and infiltrated cells of H22 cells and Hepa1-6 cells in Gpr109A-OE group were significantly higher than that of LV-NC-OE group. The results of flow cytometry experiments showed that the apoptosis rates of H22 cells and Hepa1-6 cells in the Gpr109A-OE group were significantly less than those in the LV-NC-OE group (Fig. 5). Therefore, the above results illustrated that Gpr109A promoted the proliferation, migration and invasion of hepatocellular carcinoma cells and inhibited their apoptosis.

Effects of Gpr109A on proliferation, migration, invasion and apoptosis of hepatocellular carcinoma cells. (A) CCK-8 experimental results of H22 cells and Hepa1-6 cells in the LV-NC-OE group and Gpr109A-OE group; (B) Correlation scatterplot of SHP2 and IRE1α; (C) Cell scratch test results of H22 cells and Hepa1-6 cells in LV-NC-OE group and Gpr109A-OE group, as well as statistical charts of cell spacing distance at 0 h and 48 h; (D) Transwell experimental results of H22 cells and Hepa1-6 cells in the LV-NC-OE group and Gpr109A-OE group, as well as the number of migrating and invading cells; (E) Flow cytometry results and apoptosis rate of H22 cells and Hepa1-6 cells in the LV-NC-OE group and Gpr109A-OE group. Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation; N = 3; **P < 0.01; nsP>0.05.

Gpr109A reverses the differentiation of primary macrophages into an M2c-type immunosuppressive state under the hepatocellular carcinoma microenvironment through the inhibition of SHP2 phosphorylation via the PKA, MerTK, and p-IRE1α signaling pathways

Following the aforementioned methodology, primary macrophages were harvested from Gpr109A WT mice and differentiated into M2 macrophages in a co-culture system with H22 hepatocellular carcinoma cells, divided into four groups: Gpr109A WT, Gpr109A WT Niacin-treated, Gpr109A WT Niacin and PKA inhibitor (H892HCl) co-treated, and Gpr109A WT Niacin and MerTK inhibitor (UNC2881) co-treated.

The Western Blot experiments revealed that compared to Gpr109A WT mice, the Gpr109A WT Niacin-treated group exhibited significant increases in the expression levels of PKA, MerTK, p-STAT3, p-STAT6, p-IRE1α, Cathepsin K, and PD-L1 proteins. Conversely, in comparison to Gpr109A WT mice, the co-treated group with Niacin and the PKA inhibitor (H892HCl) demonstrated marked decreases in the expression levels of PKA, MerTK, p-STAT3, p-STAT6, p-IRE1α, Cathepsin K, and PD-L1 proteins, with a slight decrease in PKA expression levels. Similarly, compared to Gpr109A WT mice, the co-treated group with Niacin and the MerTK inhibitor (UNC2881) exhibited significant reductions in the expression levels of p-STAT3, p-STAT6, p-IRE1α, Cathepsin K, and PD-L1 proteins, while PKA expression levels were restored to levels similar to those of the Gpr109A WT Niacin-treated group, with a slight expression of MerTK protein.

Initially, Gpr109A−/− mice were injected weekly via the tail vein with lentiviruses LV-NC and LV-MerTK-OE for four weeks before the extraction of BMM cells. Subsequently, following the aforementioned method, primary macrophages were extracted and differentiated into M2-type macrophages and co-cultured with hepatocellular carcinoma cells H22. They were divided into four groups: Gpr109A−/− LV-NC, Gpr109A−/− LV-NC Niacin-treated group, Gpr109A−/− LV-NC PKA agonist (Dibutyryl) group, and Gpr109A−/− LV-MerTK-OE group.

The Western Blot experiments revealed that compared to the Gpr109A−/− LV-NC group, there were no significant differences in the expression levels of PKA, MerTK, p-STAT3, p-STAT6, p-IRE1α, Cathepsin K, and PD-L1 proteins in the Gpr109A−/− LV-NC Niacin-treated group. However, in comparison to the Gpr109A−/− LV-NC group, the Gpr109A−/− LV-NC PKA agonist (Dibutyryl) group exhibited significant increases in the expression levels of PKA, MerTK, p-STAT3, p-STAT6, p-IRE1α, Cathepsin K, and PD-L1 proteins. Furthermore, compared to the Gpr109A−/− LV-NC group, the Gpr109A−/− LV-MerTK-OE group showed significant increases in the expression levels of MerTK, p-STAT3, p-STAT6, p-IRE1α, Cathepsin K, and PD-L1 proteins, with a slight expression of PKA. PKA, as the upstream gene of MerTK, was not regulated by it, while Dibutyryl, as an agonist of PKA, could directly promote the expression of PKA (Fig. 6A).

Protein Expression in Gpr109A WT and Gpr109A−/− Primary Macrophages Co-Cultured with H22 hepatocellular carcinoma Cells. (A) Western blot analysis indicating the expression levels of proteins associated with the PKA, MerTK, and p-IRE1α signaling pathways, Cathepsin K, and the immune checkpoint molecule PD-L1 in Gpr109A WT and Gpr109A−/− primary macrophages upon various treatments; (B) Western blot analysis indicating the expression levels of proteins associated with the IL-10, TGFβ, CD163, PPARγ, and P53 in Gpr109A WT and Gpr109A−/− primary macrophages upon various treatments; (C) Western blot analysis indicating the expression levels of proteins associated with the p-SHP2, PPARγ, and P53 in Gpr109A WT and Gpr109A−/− primary macrophages upon various treatments; GAPDH as control protein; Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation; N = 3; **P < 0.01; nsP>0.05.

Subsequently, we assessed the phosphorylation status of SHP2, a key protein involved in the polarization of M2 macrophages and the activation of immune suppression.

The Western Blot experiments revealed that compared to the Gpr109A WT group, the Gpr109A WT Niacin-treated group exhibited significant increases in the expression levels of IL-10, TGFβ, CD163, PPARγ, and P53 proteins while showing a decrease in p-SHP2 expression levels. Conversely, in comparison to Gpr109A WT mice, the co-treated group with Niacin and the PKA inhibitor (H892HCl) demonstrated significant decreases in the expression levels of IL-10, TGFβ, CD163, PPARγ, and P53 proteins, along with an increase in p-SHP2 expression levels. Similarly, compared to the Gpr109A WT group, the co-treated group with Niacin and the MerTK inhibitor (UNC2881) exhibited significant decreases in the expression levels of IL-10, TGFβ, CD163, PPARγ, and P53 proteins, with notable increases in PPARγ and P53 protein expression levels, while showing a decrease in p-SHP2 expression levels (Fig. 6B,C).

Gpr109A has collectively influenced the transition of SHP2-dependent M2c immunomodulatory state through the p-STING, p-SYK, and p-SYK pathways

Based on Western Blot experiments, it is observed that compared to the Gpr109A WT group, the expression levels of P2 × 7R, p-STING, p-SYK, p-SHP2, and IFNβ proteins are significantly reduced in the Gpr109A WT group treated with niacin. Conversely, in comparison to the Gpr109A WT mice, the group co-treated with niacin and PKA inhibitor (H892HCl) exhibited markedly increased expression levels of P2 × 7R, p-STING, p-SYK, p-SHP2, and IFNβ proteins. Similarly, when compared to the Gpr109A WT group, the group co-treated with niacin and MerTK inhibitor (UNC2881) showed significant elevation in the expression levels of P2 × 7R, p-STING, p-SYK, p-SHP2, and IFNβ proteins. Furthermore, in contrast to the Gpr109A WT group, both the Gpr109A−/− LV-NC group and the Gpr109A−/− LV-NC group treated with niacin exhibited significantly increased protein expression levels of P2 × 7R, p-STING, p-SYK, p-SHP2, and IFNβ with no difference observed between the two groups. Conversely, the protein expression levels in the Gpr109A−/− LV-NC PKA agonist (Dibutyryl) group and the Gpr109A−/− LV-MerTK-OE group were markedly decreased with no significant difference observed between the two groups (Fig. 7A).

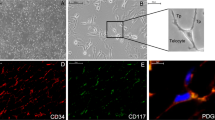

Influence of Gpr109A activation and inhibition on protein expression levels and phagocytic activity. (A) Western blot analysis indicating the expression levels of proteins associated with the P2 × 7R, p-STING, IFNβ, p-SYK, and p-SHP2 in Gpr109A WT and Gpr109A−/− primary macrophages upon various treatments; GAPDH as control protein; (B) Phagocytosis assay results comparing various treatment groups in relation to Gpr109A receptor activity showed: Gpr109A WT Niacin (NA) treatment increased phagocytosis significantly compared to WT group. Conversely, co-treatment with NA and PKA inhibitor (H892HCl) significantly decreased phagocytosis. Moreover, NA co-treatment with MerTK inhibitor (UNC2881) further reduced phagocytosis. Both Gpr109A−/− LV-NC and Gpr109A−/− LV-NC NA-treated groups exhibited significantly decreased phagocytosis compared to WT, with no disparity between them. Notably, compared to Gpr109A−/− LV-NC, Gpr109A−/− LV-NC PKA agonist and Gpr109A−/− LV-MerTK-OE groups demonstrated significant increases in phagocytosis. Red: GFP fluorescent latex beads; Green: CD68; Blue: DAPI; Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation; N = 3; **P < 0.01; nsP>0.05.

The subsequent phagocytosis assay revealed that compared to the Gpr109A WT group, the Gpr109A WT Niacin-treated group demonstrated a significant increase in the phagocytosis of fluorescent microspheres, while the co-treated group with Niacin and the PKA inhibitor (H892HCl) showed a significant decrease in the phagocytosis of fluorescent microspheres. Conversely, the co-treated group with Niacin and the MerTK inhibitor (UNC2881) exhibited a further reduction in the phagocytosis of fluorescent microspheres. Compared to the Gpr109A WT group, both the Gpr109A−/− LV-NC group and the Gpr109A−/− LV-NC Niacin-treated group demonstrated a significant decrease in the phagocytosis of fluorescent microspheres, with no difference between the two groups. Additionally, compared to the Gpr109A−/− LV-NC group, the Gpr109A−/− LV-NC PKA agonist (Dibutyryl) group and the Gpr109A−/− LV-MerTK-OE group showed significant increases in the phagocytosis of fluorescent microspheres (Fig. 7B). Niacin-mediated Gpr109A promotes hepatocellular carcinoma progression by enhancing macrophage polarization to M2c type and hepatocellular carcinoma cell invasiveness, thereby promoting hepatocellular carcinoma progression (Fig. 8).

Discussion

Immune cells within the hepatocellular carcinoma tumor microenvironment, such as M2 macrophages, play a crucial role in tumor development and progression. These immune cells not only recognize and suppress tumor growth but also facilitate tumor progression60,61. In vitro models have demonstrated superior capabilities in replicating the biological characteristics of the hepatocellular carcinoma microenvironment, providing robust support for tumor immunotherapy studies. Clinical and pathological characteristics of hepatocellular carcinoma, including age, grade, stage, and molecular subtype, influence both prognosis and treatment decisions62,63.

Dendritic cells (DCs), essential for bridging innate and adaptive immunity, activate T cells through antigen presentation. The expression of Gpr109A in dendritic cells has been established. Gpr109A activation impacts dendritic cell maturation and function, reduces their secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines, and diminishes their ability to stimulate T cells, potentially preventing excessive immune responses and the development of autoimmune diseases. Regulatory T cells (Tregs) are critical in maintaining immune tolerance and preventing autoimmune reactions. The function of Tregs is closely linked to the activation of Gpr109A, with studies indicating that Gpr109A activation promotes Treg proliferation and functional enhancement, aiding in the suppression of unwanted immune responses. This role is particularly significant for controlling chronic inflammation and autoimmune diseases. Macrophage polarization describes the functional and phenotypic changes macrophages undergo in response to various microenvironmental stimuli. Based on these stimuli, macrophages differentiate into multiple subtypes, with M1 and M2 macrophages being the most common64,65. Activated M1 macrophages primarily induce anti-tumor and antimicrobial immune responses via receptor-mediated signaling pathways, such as Toll-like receptors (TLRs) and cytokine stimulation (e.g., IFN-γ, TNF-α). They express high levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines like IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α, facilitating the clearance of bacteria and pathogens, and promoting anti-tumor immune responses by activating adaptive immune cells66,67,68. Conversely, M2 macrophages are key players in anti-inflammatory and repair processes. Their activation is largely mediated by signals from anti-inflammatory cytokines like IL-4, IL-13, and IL-10, leading to increased expression of anti-inflammatory factors such as IL-10 and TGF-β, as well as factors essential for tissue repair and cellular reconstruction, including VEGF, EGF, and PDGF. M2 macrophages further contribute to angiogenesis, fibrosis, and immunomodulation69,70,71,72. Specifically, M2a macrophages, induced by cytokines like IL-4 and IL-13, exhibit anti-inflammatory, antibacterial, tissue repair, and cell proliferation-promoting functions, playing a central role in immunoregulation73. M2b macrophages, typically induced by TLR activation or IL-10 stimulation, are significant in anti-inflammatory responses and immune regulation74. M2c macrophages, induced by cytokines such as IL-10 and TGF-β, are involved in anti-inflammatory, immunoregulatory, cellular reconstruction, and tissue repair functions, particularly in chronic inflammatory states and tissue repair processes75,76.

Gpr109A holds a significant role within the tumor microenvironment-a complex ecosystem of non-tumor cells, extracellular matrix, and blood vessels surrounding tumor cells. This environment promotes mutual regulation of tumor growth, invasion, metastasis, and drug resistance through interactions among its cellular components77,78. Gpr109A, a G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) with a seven-transmembrane structure, belongs to a large GPCR family with over 800 members79. It is integral to lipid metabolism, anti-inflammatory responses, and anti-tumor functions80. Low doses of niacin can induce macrophage polarization from the M1 (pro-inflammatory) to the M2 (anti-inflammatory) phenotype via Gpr109A81,82.

Experiments with nude mice have shown that hepatocellular carcinoma cells lacking Gpr109A have reduced tumorigenic capabilities. Preliminary findings suggest that macrophages deficient in Gpr109A show decreased M2 polarization, leading to reduced tumorigenicity of hepatocellular carcinoma cells in the tumor microenvironment. This indicates that Gpr109A activation may promote macrophage differentiation into the M2 phenotype, aiding tumor development.

G protein-coupled receptor kinases (GRKs) are a group of serine/threonine kinases capable of phosphorylating and inactivating GPCRs by interacting with activated GPCRs, promoting receptor phosphorylation and downstream signaling83,84. Protein kinase A (PKA), a critical enzyme in cellular signal transduction, consists of regulatory (R) and catalytic (C) subunits, primarily involved in the cyclic AMP (cAMP) signaling pathway85. Gpr109A activation significantly increases PKA levels through GRK activity. MerTK, a receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) expressed in various cell types, including macrophages and dendritic cells, plays a crucial role in signaling pathways involved in phagocytosis, inflammation regulation, immune tolerance, and tissue repair. MerTK contributes to M2 macrophage polarization by binding to ligands such as Gas6 or ProS1, inducing macrophage development into the M2 phenotype and participating in related signaling pathways. In the hepatocellular carcinoma tumor microenvironment, complex interactions among signaling molecules and proteins influence the polarization and function of M2 macrophages86,87,88,89,90,91,92. PKA activation can stimulate PPARγ expression, further influencing macrophage function and promoting M2 polarization93.

Western Blot analysis showed that specific knockdown of Gpr109A in primary macrophages reduced the expression of PKA, p-PPARγ, MerTK, p-STAT3, p-STAT6, IL-10, CD163, CD206, CCL18, TGF-β, Cathepsin K, Cathepsin S, and PD-L1 in them. It suggests that niacin-promoted Gpr109A drives cathepsin overexpression in M2c macrophages via the PKA/p-PPARγ/MerTK/p-STAT3/p-STAT6 pathway.

Activation of PPARγ can enhance the activity of macrophage surface receptors like Tyro3, Axl, and MerTK. MerTK activation, in particular, can inhibit M1 macrophage polarization while promoting M2 macrophage polarization. Additionally, MerTK enhances immune suppression in the tumor microenvironment by promoting the phagocytosis of apoptotic cells. MerTK activation not only promotes macrophage polarization but also stimulates the phosphorylation of STAT3 and STAT6, further inducing the secretion of immunosuppressive cytokines such as IL-10 and TGF-β. The increase in these cytokines supports immune evasion within the tumor microenvironment. This study highlights that MerTK overexpression via lentiviral vectors and the application of inhibitors collectively indicate that MerTK facilitates immune suppression in the M2 polarization state by uniquely engulfing apoptotic hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Comparative analyses between Gpr109A wild-type and knockout mice reveal Gpr109A’s pivotal role within the hepatocellular carcinoma immune microenvironment. Experiments have shown that the hepatocellular carcinoma tumor weight in Gpr109A knockout mice significantly decreases, suggesting its potential role in inhibiting the tumorigenicity of H22 cells. Co-culture experiments further demonstrate that the tumor volume and weight of LV-Gpr109A-KD RAW264.7 cells were substantially reduced.

PKA overexpression can affect multiple downstream signaling pathways via phosphorylation, including PPARγ activation. PKA may indirectly promote M2 macrophage polarization94. Activation of PPARγ supports macrophage polarization towards the M2 phenotype, crucial for tissue repair, inflammation resolution, and tumor growth promotion93. MerTK activation inhibits M1 macrophage functionality while promoting M2 macrophage polarization. Moreover, MerTK enhances immune suppression in the tumor microenvironment by facilitating the phagocytosis of apoptotic cells95,96. Activation of p-STAT3 and p-STAT6 is closely associated with M2 macrophage functionality and polarization, regulating the production of immunosuppressive cytokines like IL-10, thereby promoting tumor immune escape. IL-10, an immunosuppressive cytokine, favors macrophage polarization towards the M2 phenotype, facilitating tumor immune evasion in the hepatocellular carcinoma microenvironment. Cathepsin K/S protease activities in macrophages are linked to tumor aggressiveness and metastasis, potentially promoting tumor cell migration and dissemination through extracellular matrix degradation97. Activation of IRE1α during endoplasmic reticulum stress promotes adaptive cellular responses, aiding tumor cell survival under adverse conditions. IRE1α may also influence the tumor microenvironment by affecting macrophage functionality98. PD-L1 expression on tumor cell surfaces is associated with immune escape mechanisms. By binding to PD-1, PD-L1 inhibits T-cell activation, thereby promoting tumor growth. p-SYK is involved in immune cell activation and signaling and may regulate immune responses within the tumor microenvironment by influencing macrophage function99. SHP2 functions in various cell signaling pathways, including those affecting macrophage polarization and functionality, potentially influencing macrophage phagocytosis by regulating MerTK dephosphorylation. IFN-β, an immunomodulatory factor, can activate the immune system against tumors. In the tumor microenvironment, macrophage status may influence IFN-β production, thereby affecting tumor immune surveillance100.

This comprehensive investigation into Gpr109A’s role within the hepatocellular carcinoma immune microenvironment has elucidated its significant impact on the tumorigenicity of H22 cells and macrophage polarization. The experimental results underscore Gpr109A’s crucial function in regulating macrophage behavior and hepatocellular carcinoma cell dynamics through intricate signaling pathways, notably the PKA/p-PPARγ/MerTK pathway. Gpr109A deletion in mice (Gpr109A-/-) led to a marked reduction in tumor growth, as evidenced by decreased tumor weight and volume compared to wild-type mice. This reduction correlated with lowered expression levels of PKA, p-PPARγ, and MerTK proteins in Gpr109A-/- macrophages, highlighting the pathway’s pivotal role in tumor regulation.

Gpr109A polarizes macrophages and thus promotes tumorigenesis; co-culture scratch assays and Transwell assays demonstrated enhanced cell migration and invasion under Gpr109A-deficient conditions.CCK-8 assays and flow cytometry showed decreased proliferation and increased apoptosis in Gpr109A-deficient hepatocellular carcinoma cells, and niacin treatment reversed this effect. Gpr109A overexpression assays confirmed increased proliferation, migration, invasion, and decreased apoptosis in H22 and Hepa1-6 cells, linking Gpr109A activity to the interaction of SHP2 and IRE1α during hepatocellular carcinoma progression. Western blotting showed that PKA, MerTK, p-STAT3, p-STAT6, p-IRE1α, Cathepsin K, and PD-L1 were significantly increased by Gpr109A WT niacin, but the expression of the above proteins was reduced by the combined effect of H892HCl or UNC2881.Gpr109A-/- PKA, MerTK, p-STAT3, p-STAT6, p-IRE1α, Cathepsin K, and PD-L1 were not significantly different in the LV-NC Niacin group, but were significantly increased in the Gpr109A−/−LV-NC PKA agonist group and the Gpr109A−/−LV-MerTK-OE group.In the Gpr109A WT Niacin group, the expression of IL-10, TGFβ, CD163, PPARγ, and P53 were significantly increased and p-SHP2 was decreased, but p-SHP2 was decreased and increased in the H892HCl or UNC2881 combination treatment groups. The expression of P2 × 7R, p-STING, p-SYK, p-SHP2 and IFNβ was decreased in the niacin-treated Gpr109A WT group compared with the Gpr109A WT group. Meanwhile, combined treatment with H892HCl or UNC2881 significantly increased the levels of these proteins.The protein levels were increased in both Gpr109A−/− LV-NC groups (untreated and niacin-treated groups) and decreased in the Gpr109A−/− LV-NC PKA agonist (dibutyryl) group and the Gpr109A−/− LV-MerTK-OE group. Phagocytosis assays showed that niacin treatment increased fluorescent microsphere uptake in the Gpr109A WT group, but uptake was reduced after co-treatment with H892HCl. Combined use of UNC2881 further decreased phagocytosis. phagocytosis was decreased in both Gpr109A−/− LV-NC groups (untreated and niacin-treated groups), while phagocytosis was increased in the Gpr109A−/− LV-NC PKA agonist (dibutyryl) group and the Gpr109A−/− LV-MerTK-OE group.

Some studies have identified that GPR109A upregulates the expression of the oncogene Hopx and plays a role in inhibiting tumor progression101,102. In this study, we found that Niacin mediated Gpr109A to promote the progression of HCC cells through GRK/PKA/PPARγ/SHP2 signaling pathway. Our data suggest that Gpr109A knockdown significantly upregulated P2 × 7R expression and SYK phosphorylation, possibly through cAMP-PKA-mediated direct phosphorylation of NF-κB and SYK at S297. Activation of P2 × 7R and SYK may be responsible for the enhanced inflammatory response observed in Gpr109A-deficient macrophages.Gpr109A deficiency mediates the PPARγ/P53 signaling pathway, which enhances SHP2 phosphatase activity. Activated SHP2 disrupts metabolic support for M2 polarization by dephosphorylating STAT3 and STAT6, thereby impairing IL-10 signaling and immunosuppression. It provides a new research target for Niacin to mediate the role of Gpr109A on HCC progression. In conclusion, the experimental findings provide compelling evidence of Gpr109A’s central role in the hepatocellular carcinoma immune microenvironment, influencing both macrophage behavior and hepatocellular carcinoma cell progression through sophisticated signaling mechanisms. These insights enhance our understanding of tumor immunology and open avenues for targeted therapeutic strategies that manipulate the Gpr109A pathway to counteract hepatocellular carcinoma progression. Manipulating this pathway holds promise for developing novel cancer treatments aimed at modulating the immune microenvironment to the patient’s advantage. However, this study was conducted in a mouse model or an in vitro cell culture system, and further experimental validation of the results’ full applicability to humans is required. Although Gpr109A shows potential in modulating immune responses under laboratory conditions, translating these findings into clinical therapies still poses significant challenges.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Bicer, F. et al. Advances in immunotherapy for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Curr. Oncol. 30 (11), 9789–9812. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol30110711 (2023).

Revoredo, S. & Del Fabbro, E. Hepatocellular carcinoma and sarcopenia: a narrative review. Ann. Palliat. Med. 12 (6), 1295–1309. https://doi.org/10.21037/apm-23-332 (2023).

Lu, Y. et al. A single-cell atlas of the multicellular ecosystem of primary and metastatic hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat. Commun. 13 (1), 4594. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-32283-3 (2022).

Zhang, Z. et al. IFN-α facilitates the effect of Sorafenib via shifting the M2-like polarization of TAM in hepatocellular carcinoma. Am. J. Transl Res. 13 (1), 301–313 (2021).

Cao, H. & Wang, S. G-CSF promotes the development of hepatocellular carcinoma by activating the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway in TAM. Aging (Albany NY). 16 (13), 10799–10812. https://doi.org/10.18632/aging.205922 (2024).

Meng, J. et al. Tumor-derived Jagged1 promotes cancer progression through immune evasion. Cell. Rep. 38 (10), 110492. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2022.110492 (2022).

BISWAS, S. et al. Mesenchymal stem cells educate breast tumor-associated macrophages to acquire increased immunosuppressive features. J. IMMUNOL. 202 (1_Supple), 13525–13525. https://doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.202.supp.135.25 (2019).

Yuan, H. et al. Resistance of MMTV-NeuT/ATTAC mice to anti-PD-1 immune checkpoint therapy is associated with macrophage infiltration and Wnt pathway expression. Oncotarget 13, 1350–1358. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.28330 (2022).

Babikr, F. et al. Distinct roles but the cooperative effect of TLR3/9 agonists and PD-1 Blockade in converting the immunotolerant microenvironment of irreversible electroporation-ablated tumors. CELL. MOL. IMMUNOL. 18 (12), 2632–2647. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41423-021-00796-4 (2021).

Henderson, L. M. & Niacin Annu. Rev. Nutr. 3 289–307. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.nu.03.070183.001445 (1983).

Santolla, M. F. et al. Niacin activates the G protein Estrogen receptor (GPER)-mediated signaling. CELL. SIGNAL. 26 (7), 1466–1475. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cellsig.2014.03.011 (2014).

Cheong, H. I. et al. Hypoxia sensing through β-adrenergic receptors. JCI Insight. 1 (21), e90240. https://doi.org/10.1172/jci.insight.90240 (2016). Published 2016 Dec 22.

Li, G. et al. Internalization of the human niacin receptor Gpr109A is regulated by G(i), GRK2, and arrestin3. J. BIOL. CHEM. 285 (29), 22605–22618. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M109.087213 (2010).

Han, C. C. et al. CP-25 inhibits PGE2-induced angiogenesis by down-regulating EP4/AC/cAMP/PKA-mediated GRK2 translocation. CLIN. SCI. 134 (3), 331–347. https://doi.org/10.1042/CS20191032 (2020).

Horner, T. J. et al. Phosphorylation of GRK1 and GRK7 by cAMP-dependent protein kinase attenuates their enzymatic activities. J. BIOL. CHEM. 280 (31), 28241–28250. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M505117200 (2005).

Guri, A. J., Hontecillas, R. & Bassaganya-Riera, J. Abscisic acid synergizes with Rosiglitazone to improve glucose tolerance and down-modulate macrophage accumulation in adipose tissue: possible action of the cAMP/PKA/PPAR γ axis. CLIN. NUTR. 29 (5), 646–653. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnu.2010.02.003 (2010).

Flori, E. et al. The α-melanocyte stimulating hormone/peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ pathway down-regulates proliferation in melanoma cell lines. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 36 (1), 142. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13046-017-0611-4 (2017).

Zizzo, G. & Cohen, P. L. The PPAR-γ antagonist GW9662 elicits differentiation of M2c-like cells and upregulation of the MerTK/Gas6 axis: a key role for PPAR-γ in human macrophage polarization. J. Inflamm. (Lond). 12, 36. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12950-015-0081-4 (2015).

Alciato, F. et al. TNF-alpha, IL-6, and IL-1 expression is inhibited by GAS6 in monocytes/macrophages. J. Leukoc. BIOL. 87 (5), 869–875. https://doi.org/10.1189/jlb.0909610 (2010).

Camenisch, T. D. et al. A novel receptor tyrosine kinase, Mer, inhibits TNF-alpha production and lipopolysaccharide-induced endotoxic shock. J. IMMUNOL. 162 (6), 3498–3503 (1999). PMID: 10092806.

Shen, Y. et al. Exogenous Gas6 attenuates silica-induced inflammation on differentiated THP-1 macrophages. ENVIRON. TOXICOL. PHAR. 45, 222–226. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.etap.2016.05.029 (2016).

Kim, S. Y. et al. Liver X receptor and STAT1 cooperate downstream of Gas6/Mer to induce anti-inflammatory arginase 2 expressions in macrophages. Sci. Rep. 6, 29673. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep29673 (2016).

Yeh, H. W. et al. Axl involved in mineral trioxide aggregate induces macrophage polarization. J. ENDODONT. 44 (10), 1542–1548. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joen.2018.07.005 (2018).

MacKinnon, A. C. et al. Regulation of alternative macrophage activation by galectin-3. J. IMMUNOL. 180 (4), 2650–2658. https://doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.180.4.2650 (2008).

Elliott, M. R. et al. Nucleotides released by apoptotic cells act as a find-me signal to promote phagocytic clearance. NATURE 461 (7261), 282–286. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature08296 (2009).

Lauber, K. et al. Apoptotic cells induce the migration of phagocytes via the caspase-3-mediated release of a lipid attraction signal. CELL 113 (6), 717–730. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00422-7 (2003).

Truman, L. A. et al. CX3CL1/fractalkine is released from apoptotic lymphocytes to stimulate macrophage chemotaxis. BLOOD 112 (13), 5026–5036. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2008-06-162404 (2008).

Gude, D. R. et al. Apoptosis induces the expression of sphingosine kinase 1 to release sphingosine-1-phosphate as a come-and-get-me signal. FASEB J. 22 (8), 2629–2638. https://doi.org/10.1096/fj.08-107169 (2008).

Yi, Z. et al. A novel role for c-Src and STAT3 in apoptotic cell-mediated MerTK-dependent immunoregulation of dendritic cells. BLOOD 114 (15), 3191–3198. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2009-03-207522 (2009).

Soliman, E. et al. Efferocytosis is restricted by axon guidance molecule EphA4 via ERK/Stat6/Mertk signaling following brain injury. Res. Sq. https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-3079466/v1 (2023).

Allison, K. et al. Inhibiting efferocytosis in acute myeloid leukemia decreases checkpoint Blockade through decreased CCL5/STAT6 signaling and increases activation through NF-Kb. Blood138 (Supple 1), 1174–1174. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2021-154513 (2021).

Li, D. et al. MiRNA-374b-5p and miRNA-106a-5p are related to inflammatory bowel disease via regulating IL-10 and STAT3 signaling pathways. BMC Gastroenterol. 22 (1), 492. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12876-022-02533-1 (2022).

Zheng, S. et al. LRP8 activates STAT3 to induce PD-L1 expression in osteosarcoma. TUMORI J. 107 (3), 238–246. https://doi.org/10.1177/0300891620952872 (2020).

Qi, L. et al. IL-10 secreted by M2 macrophage promoted tumorigenesis through interaction with JAK2 in glioma. Oncotarget 7 (44), 71673–71685. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.12317 (2016).

Wei, C. Y. et al. PKCα/ZFP64/CSF1 axis resets the tumor microenvironment and fuels anti-PD1 resistance in hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Hepatol. 77 (1), 163–176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2022.02.019 (2022).

Haber, P. K. et al. Molecular markers of response to Anti-PD1 therapy in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology 164 (1), 72–88e18. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2022.09.005 (2023).

Esteban-Fabró, R. et al. Cabozantinib enhances Anti-PD1 activity and elicits a Neutrophil-Based immune response in hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 28 (11), 2449–2460. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432 (2022).

Bednarska, K. et al. The IRE1-XBP1s pathway impairment underpins NK cell dysfunction in hodgkin lymphoma, that is partly restored by PD-1 Blockade. BLOOD 134 (Supple1), 2795–2795. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2019-126372 (2019).

Zheng, H. et al. Induction of a tumor-associated activating mutation in protein tyrosine phosphatase Ptpn11 (Shp2) enhances mitochondrial metabolism, leading to oxidative stress and senescence. J. BIOL. CHEM. 288 (36), 25727–25738. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M113.462291 (2013).

Wörmann, S. M. et al. Loss of P53 function activates JAK2-STAT3 signaling to promote pancreatic tumor growth, stroma modification, and gemcitabine resistance in mice and is associated with patient survival. GASTROENTEROLOGY 151 (1), 180–193e12. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2016.03.010 (2016).

Cai, T. et al. Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase and NADPH oxidase 4 control STAT3 activity in melanoma cells through a pathway involving reactive oxygen species, c-SRC and SHP2. Am. J. Cancer Res. 5 (5), 1610-20. (2015).

Di, Y. X. et al. Tomentosin suppressed M1 polarization via increasing MERTK activation mediated by regulation of GAS6. J. ETHNOPHARMACOL. 314, 116429. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2023.116429 (2023).

Hedrich, V. et al. Intrinsic and extrinsic control of hepatocellular carcinoma by TAM receptors. Cancers (Basel) 13 (21). https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers13215448 (2021).

Hjermstad, S. J. et al. Regulation of the human c-fes protein tyrosine kinase (p93c-fes) by its src homology 2 domain and major autophosphorylation site (Tyr-713). Oncogene 8 (8), 2283-92. (1993).

Ellis, C. et al. A juxtamembrane autophosphorylation site in the Eph family receptor tyrosine kinase, Sek, mediates high-affinity interaction with p59fyn. Oncogene 12 (8), 1727-36. (1996).

Fuentes, L., Roszer, T. & Ricote, M. Inflammatory mediators and insulin resistance in obesity: role of nuclear receptor signaling in macrophages. Mediat. Inflamm. 2010 (219583). https://doi.org/10.1155/2010/219583 (2010).

Pastore, M. et al. Role of Myeloid-Epithelial-Reproductive tyrosine kinase and macrophage polarization in the progression of atherosclerotic lesions associated with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Front. Pharmacol. 10, 604. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2019.00604 (2019).

Hart, K. C., Robertson, S. C. & Donoghue, D. J. Identification of tyrosine residues in constitutively activated fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 involved in mitogenesis, stat activation, and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase activation. MOL. BIOL. CELL. 12 (4), 931–942. https://doi.org/10.1091/mbc.12.4.931 (2001).

Röszer, T. Transcriptional control of apoptotic cell clearance by macrophage nuclear receptors. APOPTOSIS 22 (2), 284–294. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10495-016-1310-x (2017).

Zhou, Y. et al. Blockade of the Phagocytic Receptor MerTK on Tumor-Associated Macrophages Enhances P2X7R-Dependent STING Activation by Tumor-Derived cGAMP. IMMUNITY 52 (2), 357–373e9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.immuni.2020.01.014 (2020).

Gui, X. et al. Autophagy induction via STING trafficking is a primordial function of the cGAS pathway. NATURE 567 (7747), 262–266. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-019-1006-9 (2019).

Wang, C. et al. EGFR-mediated tyrosine phosphorylation of STING determines its trafficking route and cellular innate immunity functions. EMBO J. 39 (22), e104106. https://doi.org/10.15252/embj.2019104106 (2020).

Ni, G., Konno, H. & Barber, G. N. Ubiquitination of STING at lysine 224 controls IRF3 activation. Sci. Immunol. 2 (11), eaah7119. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciimmunol.aah7119 (2017).

Mócsai, A., Ruland, J. & Tybulewicz, V. L. The SYK tyrosine kinase: is a crucial player in diverse biological functions. NAT. REV. IMMUNOL. 10 (6), 387–402. https://doi.org/10.1038/nri2765 (2010).

Ng, G. et al. Receptor-independent, direct membrane binding leads to cell-surface lipid sorting and Syk kinase activation in dendritic cells. IMMUNITY 29 (5), 807–818. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.immuni.2008.09.013 (2008).

Li, X. et al. Circulating VEGF-A, TNF-α, CCL2, IL-6, and IFN-γ as biomarkers of cancer in cancer-associated anti-TIF1-γ antibody-positive dermatomyositis. CLIN. RHEUMATOL. 42 (3), 817–830. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-022-06425-3 (2022).

Liu, Z. et al. Network Pharmacology to investigate the Pharmacological mechanisms of muscone in Xingnaojing injections for the treatment of severe traumatic brain injury. PeerJ 9, e11696. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.11696 (2021).

Khan, A. & Sergi, C. SAMHD1 as the potential link between SARS-CoV-2 infection and neurological complications. Front. Neurol. 11, 562913. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2020.562913 (2020).

Wang, C. et al. STING-Mediated interferon induction by herpes simplex virus 1 requires the protein tyrosine kinase Syk. mBio 12 (6), e0322821. https://doi.org/10.1128/mbio.03228-21 (2021).

Hedrich, V. et al. Intrinsic and extrinsic control of hepatocellular carcinoma by TAM receptors. Cancers (Basel). 13 (21), 5448. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers13215448 (2021).

Hu, X. et al. Glutamine metabolic microenvironment drives M2 macrophage polarization to mediate trastuzumab resistance in HER2-positive gastric cancer. Cancer Commun. (Lond). 43 (8), 909–937. https://doi.org/10.1002/cac2.12459 (2023).

Abe, K., Tani, K. & Fujiyoshi, Y. Systematic comparison of molecular conformations of H+, K+-ATPase reveals an important contribution of the A-M2 linker for the luminal gating. J. Biol. Chem. 289 (44), 30590–30601. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M114.584623 (2014).

Sangro, B. et al. Four-year overall survival update from the phase III HIMALAYA study of Tremelimumab plus durvalumab in unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Ann. Oncol. 35 (5), 448–457. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annonc.2024.02.005 (2024).

Mills, C. D., M1 & Macrophages, M. Oracles of health and disease. Crit. Rev. Immunol. 32 (6), 463–488. https://doi.org/10.1615/critrevimmunol.v32.i6.10 (2012).

Orecchioni, M., Ghosheh, Y., Pramod, A. B. & Ley, K. Macrophage polarization: different gene signatures in M1(LPS+) vs. Classically and M2(LPS-) vs. Alternatively activated macrophages [published correction appears in front Immunol. 2020;11:234]. Front. Immunol. 10, 1084. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2019.01084 (2019). Published 2019 May 24.

Zhang, J. et al. NLRP3 inflammasome mediates M1 macrophage polarization and IL-1β production in inflammatory root resorption. J. Clin. Periodontol. 47 (4), 451–460. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpe.13258 (2020).

Lu, Y. et al. M2 macrophage-secreted exosomes promote metastasis and increase vascular permeability in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cell. Commun. Signal. 21 (1), 299. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12964-022-00872-w (2023).

Lafont, E. et al. TBK1 and IKKε prevent TNF-induced cell death by RIPK1 phosphorylation. Nat. Cell. Biol. 20 (12), 1389–1399. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41556-018-0229-6 (2018).

Rao, L. Z. et al. IL-24 deficiency protects mice against bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis by repressing the IL-4-induced M2 program in macrophages. Cell Death Differ. 28 (4), 1270–1283. (2021).

Gao Zhou, S. & Liu, J. N, et al. Curcumin induces M2 macrophage polarization by secretion of IL-4 and/or IL-13. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 85 131–139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yjmcc.2015.04.025 (2015).

Jung, M. et al. IL-10 improves cardiac remodeling after myocardial infarction by stimulating M2 macrophage polarization and fibroblast activation. Basic. Res. Cardiol. 112 (3), 33. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00395-017-0622-5 (2017).

Kim, K. H. et al. Intermittent fasting promotes adipose thermogenesis and metabolic homeostasis via VEGF-mediated alternative activation of macrophage. Cell. Res. 27 (11), 1309–1326. https://doi.org/10.1038/cr.2017.126 (2017).

Melton, D. W. et al. Dynamic macrophage polarization-specific MiRNA patterns reveal increased soluble VEGF receptor 1 by miR-125a-5p Inhibition. PHYSIOL. GENOMICS. 48 (5), 345–360. https://doi.org/10.1152/physiolgenomics.00098.2015 (2016).

Shabbir, M. et al. Association of CTLA-4 and IL-4 polymorphisms in viral induced liver cancer. BMC Cancer. 22 (1), 518. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-022-09633-x (2022).

Kim, D. et al. Ubiquitin E3 ligase Pellino-1 inhibits IL-10-mediated M2c polarization of macrophages. Thereby Suppressing Tumor Growth IMMUNE NETW. 19 (5), e32. https://doi.org/10.4110/in.2019.19.e32 (2019).

Junior, Lai, Y. S. et al. MERTK+/hi M2c macrophages induced by baicalin alleviate non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22 (19). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms221910604 (2021).

Bardhan, K., Ganapathy, V., Liu, K. & Abstract Constitutive and regulated expression of Gpr109A by DNA methylation and IFN-γ in human colon carcinoma cells. CANCER RES. 3140 (8_Supple), 3140–3140. https://doi.org/10.1158/1538-7445.am2012-3140 (2012).

Kant, S. et al. Enhanced fatty acid oxidation provides glioblastoma cells with metabolic plasticity to accommodate its dynamic nutrient microenvironment. Cell. Death Dis. 11 (4), 253. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41419-020-2449-5 (2020).

Chai, J. T., Digby, J. E. & Choudhury, R. P. Gpr109A and vascular inflammation. Curr. Atheroscler Rep. 15 (5), 325. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11883-013-0325-9 (2013).

Moniri, N. H. & Farah, Q. Short-chain free-fatty acid G protein-coupled receptors in colon cancer. Biochem. Pharmacol. 186, 114483. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bcp.2021.114483 (2021).

Sato, F. T. et al. Tributyrin attenuates metabolic and inflammatory changes associated with obesity through a Gpr109A-dependent mechanism. Cells 9 (9), 2007. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells9092007 (2020).

Wei, H. et al. Butyrate ameliorates chronic alcoholic central nervous damage by suppressing microglia-mediated neuroinflammation and modulating the microbiome-gut-brain axis. Biomed. Pharmacother. 160, 114308. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopha.2023.114308 (2023).

Hosey, M. M., Benovic, J. L., DebBurman, S. K. & Richardson, R. M. Multiple mechanisms involving protein phosphorylation are linked to desensitization of muscarinic receptors. Life Sci. 56 (11–12), 951–955. https://doi.org/10.1016/0024-3205(95)00033-3 (1995).

Duan, J. et al. GPCR activation and GRK2 assembly by a biased intracellular agonist. Nature 620 (7974), 676–681. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-06395-9 (2023).

Wang, W. C., Mihlbachler, K. A., Brunnett, A. C. & Liggett, S. B. Targeted transgenesis reveals discrete attenuator functions of GRK and PKA in airway beta2-adrenergic receptor physiologic signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 106 (35), 15007–15012. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0906034106 (2009).

Zhang, H., Kong, Q., Wang, J., Jiang, Y. & Hua, H. Complex roles of cAMP-PKA-CREB signaling in cancer. Exp. Hematol. Oncol. 9 (1), 32. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40164-020-00191-1 (2020). Published 2020 Nov 24.

Lee, A. K., Kim, D. H., Bang, E., Choi, Y. J. & Chung, H. Y. β-Hydroxybutyrate suppresses lipid accumulation in aged liver through Gpr109A-mediated signaling. Aging Dis. 11 (4), 777–790. https://doi.org/10.14336/AD.2019.0926 (2020). Published 2020 Jul 23.

Maimon, A. et al. Myeloid cell-derived PROS1 inhibits tumor metastasis by regulating inflammatory and immune responses via IL-10. J. Clin. Investig. 131 (10), e126089. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI126089 (2021).

Cai, B. et al. Macrophage MerTK promotes liver fibrosis in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Cell. Metab. 31 (2), 406–421e7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2019.11.013 (2020).

Du, W. et al. KPNB1-mediated nuclear translocation of PD-L1 promotes non-small cell lung cancer cell proliferation via the Gas6/MerTK signaling pathway. Cell. Death Differ. 28 (4), 1284–1300. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41418-020-00651-5 (2021).

Maimon, A. et al. Myeloid cell-derived PROS1 inhibits tumor metastasis by regulating inflammatory and immune responses via IL-10. J. Clin. Invest. 131 (10), e126089. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI126089 (2021).

Giroud, P. et al. Expression of TAM-R in human immune cells and unique regulatory function of MerTK in IL-10 production by tolerogenic DC. Front. Immunol. 11, 564133. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2020.564133 (2020). Published 2020 Sep 25.

Feng, X. et al. Chrysin attenuates inflammation by regulating M1/M2 status via activating PPARγ. BIOCHEM. PHARMACOL. 89 (4), 503–514. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bcp.2014.03.016 (2014).

Wu, H. Y. et al. Both classic Gs-cAMP/PKA/CREB and alternative Gs-cAMP/PKA/p38β/CREB signal pathways mediate exenatide-stimulated expression of M2 microglial markers. J. NEUROIMMUNOL. 316, 17–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneuroim.2017.12.005 (2017).

Wu, A. et al. Abstract 5322: glioma cancer stem cells induce immune suppressive macrophages. CANCER RES. 70 (8_Supple), 5322–5322. https://doi.org/10.1158/1538-7445.am10-5322 (2010).

Liu, L. et al. The role of C/EBP homologous protein (CHOP) in regulating macrophage polarization in THP-1 cells. MICROBIOL. IMMUNOL. 65 (12), 531–541. https://doi.org/10.1111/1348-0421.12937 (2021).

Zhang, C. et al. Cathepsin K promotes the proliferation of hepatocellular carcinoma cells through induction of SIAH1 ubiquitination and degradation. iScience 26 (6), 106852. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2023.106852 (2023).

Shan, B. et al. The metabolic ER stress sensor IRE1α suppresses alternative activation of macrophages and impairs energy expenditure in obesity. NAT. IMMUNOL. 18 (5), 519–529. https://doi.org/10.1038/ni.3709 (2017).

Zhou, Q. et al. SYK is associated with malignant phenotype and immune checkpoints in diffuse glioma. Front. Genet. 13, 899883. https://doi.org/10.3389/fgene.2022.899883 (2022).

Du, M. et al. The specific knockout of macrophage SHP2 promotes macrophage M2 polarization and alleviates renal ischemia-reperfusion injury. iScience 27 (3), 109048. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2024.109048 (2024).

Huang, Y. et al. [GPR109A partly mediates inhibitory effects of β-hydroxybutyric acid on lung adenocarcinoma cell proliferation, migration and invasion]. Nan Fang Yi Ke Da Xue Xue Bao. 43 (10), 1744–1751. https://doi.org/10.12122/j.issn.1673-4254.2023.10.12 (2023). Chinese.

Goncharova, I. A. et al. Changes in DNA methylation profile in liver tissue during progression of HCV-induced fibrosis to hepatocellular carcinoma. Vavilovskii Zhurnal Genet. Selektsii. 27 (1), 72–82. https://doi.org/10.18699/VJGB-23-10 (2023).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Cong Li and Hongan Zhang contributed equally to the study and are recognized as co-first authors. They were responsible for the experimental design, data collection and analysis, and the writing of the paper, and played equally important roles in the study. Yanchun Liu and Ting Zhang made significant contributions to the experimental design and data collection, data analysis and interpretation of results. Feng Gu, was responsible for directing the entire research project, proposing the experimental concept, interpreting the data, and writing the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

All animal protocols were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Hebei North University (HBNU2023041029893).

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, C., Zhang, H., Liu, Y. et al. Gpr109A in TAMs promoted hepatocellular carcinoma via increasing PKA/PPARγ/MerTK/IL-10/TGFβ induced M2c polarization. Sci Rep 15, 18820 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-02447-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-02447-4