Abstract

Skeletal muscle preservation during midlife is critical for preventing sarcopenia in aging populations. While calcium and vitamin D are recognized for their musculoskeletal benefits, their specific associations with muscle mass in middle-aged women remain unclear. This cross-sectional study analyzed data from 2,496 women aged 40–59 years in the NHANES (2011–2018). Multivariable linear regression models adjusted for demographics, lifestyle factors, and comorbidities evaluated associations between dietary calcium, vitamin D intakes and appendicular lean mass index (ALMI), with subgroup analyses by menopausal status and other covariates. After full adjustment, neither dietary calcium nor vitamin D intake showed significant associations with ALMI. Null findings persisted across all subgroups. Dietary calcium and vitamin D intake were not independently associated with ALMI in middle-aged women. These results highlight the need to investigate broader nutritional patterns or synergistic mechanisms influencing muscle health during midlife.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Preserving skeletal muscle integrity is crucial for maintaining physical function, metabolic homeostasis, and independence, especially in aging populations1,2. The progressive decline in muscle mass, driven by menopausal hormonal changes and intrinsic aging processes, often culminates in sarcopenia, a syndrome marked by severe mobility impairment, increased frailty, and heightened vulnerability to chronic diseases3,4. Although sarcopenia typically manifests clinically in older age, its pathophysiological underpinnings often begin decades earlier, underscoring midlife as a critical window for interventions aimed at preserving muscle mass and mitigating long-term health consequences5,6.

Nutritional interventions targeting muscle preservation have increasingly emphasized the roles of calcium and vitamin D, micronutrients with dual functions in musculoskeletal health7,8. Calcium, beyond its well-documented role in skeletal mineralization, is a key regulator of muscle contraction dynamics and protein synthesis pathways9,10. Vitamin D, meanwhile, has been consistently linked to muscle strength and functional performance, though its association with muscle mass retention remains less clearly defined11,12. While the skeletal benefits of these nutrients are well established, their specific contributions to muscle maintenance require further investigation13,14.

Emerging evidence suggests that calcium and vitamin D intake may positively influence muscle mass indices in older adults15,16, yet their impact specifically in middle-aged women remains inadequately explored. This study investigates the associations between dietary calcium and vitamin D intake and appendicular lean mass index (ALMI)—a widely utilized metric for muscle mass assessment in sarcopenia research17—among middle-aged women. Special emphasis is placed on elucidating potential effect modifications by menopausal status and other clinically significant population subgroups.

Methods

Study design and population

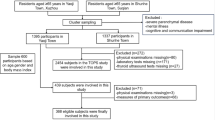

This cross-sectional analysis utilized data from four cycles (2011–2018) of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), a comprehensive biennial assessment of the U.S. population health status administered by the National Centre for Health Statistics (NCHS). The study included women aged 40–59 years (n = 3,908), with 2,496 participants remaining after excluding those with missing dietary intake measurements, ALMI data, or relevant covariates (Fig. 1). All protocols received approval from the NCHS Ethics Review Board, and all participants provided written informed consent.

Study variables

Dietary calcium and vitamin D intake were assessed through two 24-hour dietary recalls conducted by trained interviewers, the first in-person at the Mobile Examination Center and a follow-up via telephone 3–10 days later. Nutrient values were derived from the US Department of Agriculture USDA Food and Nutrient Database for Diet Studies18, with final analyses using the average intake values from both recall days.

The primary outcome, ALMI, was calculated by dividing appendicular lean mass (combined lean tissue mass of arms and legs) by height squared. Appendicular lean mass was quantified using whole-body dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry scans (QDR 4500 A fan-beam densitometer, Hologic, Inc.) following standardized manufacturer protocols.

In our analysis, a multifaceted array of potential confounding variables that could modulate the intricate relationship between dietary calcium and vitamin D intake and ALMI were incorporated: age, race, menstrual status, educational level, body mass index (BMI), sedentary behavior, calcium supplement use, vitamin D supplement use, dietary energy, dietary protein, and history of hypertension, diabetes, and cance. Postmenopausal status was defined as the absence of menstruation for ≥ 12 months. Sedentary behavior was defined as no self-reported moderate or vigorous physical activity. Detailed methodologies are available at wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/.

Statistical analyses

For normally distributed continuous data, means and standard deviations were reported, while non-normally distributed variables were summarized using medians and interquartile ranges. Categorical variables were presented as proportions. Baseline characteristics were compared by menstrual status, and associations between dietary calcium and vitamin D intakes with ALMI were examined using multivariate linear regression models following STROBE guidelines19. The analytical approach employed three progressive adjustment models: Model 1 (unadjusted), Model 2 (adjusted for age, race, menstrual status and BMI), and Model 3 (fully adjusted for all screened covariates). To identify potential effect modifications, stratified linear regression analyses were performed across participant subgroups. Non-linear relationships were explored using smooth curve fitting techniques and generalized additive models. All statistical analyses were performed using Empowerstats (www.empowerstats.com) and R software (version 3.4.3), with statistical significance defined as p < 0.05.

Results

The demographic and clinical characteristics of the 2,496 study participants stratified by menstrual status are presented in Table 1. Postmenopausal women were significantly older and showed higher prevalence of chronic conditions including hypertension, diabetes, and cancer. Sedentary behavior was more common among postmenopausal women. Dietary intake of energy, protein, and calcium was significantly lower in postmenopausal women, who conversely showed higher utilization of calcium supplements > 100 mg/30d. ALMI was significantly lower in postmenopausal women.

The associations between dietary calcium and vitamin D intake with ALMI across three statistical models are shown in Table 2. In the unadjusted analysis (Model 1), neither dietary calcium nor vitamin D showed significant associations with ALMI. After adjusting for age, race, menstrual status, and BMI (Model 2), significant positive associations emerged for both calcium and vitamin D. However, in the fully adjusted model (Model 3), these associations were attenuated and became non-significant for both calcium and vitamin D. The exploration of potential non-linear relationships (Figs. 2 and 3) further supported these findings.

The association between dietary calcium intake and appendicular lean mass index. (a) Each black point represents a sample. (b) Solid red line represents the smooth curve fit between variables. Blue bands represent the 95% of confidence interval from the fit.

Age, race, menstrual status, educational level, body mass index, sedentary behavior, calcium supplement use, vitamin D supplement use, dietary energy, dietary protein, dietary vitamin D, and history of hypertension, diabetes, and cance were adjusted.

The association between dietary vitamin D intake and appendicular lean mass index. (a) Each black point represents a sample. (b) Solid red line represents the smooth curve fit between variables. Blue bands represent the 95% of confidence interval from the fit.

Age, race, menstrual status, educational level, body mass index, sedentary behavior, calcium supplement use, vitamin D supplement use, dietary energy, dietary protein, dietary calcium, and history of hypertension, diabetes, and cance were adjusted.

Comprehensive subgroup analyses (Figs. 4 and 5) revealed consistently non-significant associations between dietary calcium or vitamin D intake and ALMI across all examined population strata. For calcium intake, effect estimates remained minimal in both premenopausal (β = 0.023, 95% CI: -0.091, 0.136) and postmenopausal women (β = 0.027, 95% CI: -0.074, 0.128), with no meaningful differences observed by menstrual status. Among racial/ethnic groups, non-Hispanic Whites exhibited the most positive, albeit non-significant association (β = 0.069, 95% CI: -0.062, 0.201), while participants with cancer history demonstrated the strongest inverse relationship (β=-0.195, 95% CI: -0.466, 0.076). For vitamin D intake, similarly non-significant patterns emerged, though with notable directional divergence between premenopausal (β = 3.464, 95% CI: -5.533, 12.461) and postmenopausal women (β=-3.385, 95% CI: -9.951, 3.182). The strongest negative association was observed among Mexican Americans (β=-8.879, 95% CI: -21.846, 4.088), whereas cancer patients exhibited the most positive relationship (β = 13.219, 95% CI: -8.383, 34.820).

Subgroup analysis of the association between dietary calcium intake and appendicular lean mass index.

Age, race, menstrual status, educational level, body mass index, sedentary behavior, calcium supplement use, vitamin D supplement use, dietary energy, dietary protein, dietary vitamin D, and history of hypertension, diabetes, and cance were adjusted. In the subgroup analysis, the model is not adjusted for the stratification variable itself.

Subgroup analysis of the association between dietary vitamin D intake and appendicular lean mass index.

Age, race, menstrual status, educational level, body mass index, sedentary behavior, calcium supplement use, vitamin D supplement use, dietary energy, dietary protein, dietary calcium, and history of hypertension, diabetes, and cance were adjusted. In the subgroup analysis, the model is not adjusted for the stratification variable itself.

Further examination of potential non-linear relationships in these subgroups (Fig. 6) confirmed the absence of significant associations across the spectrum of calcium and vitamin D intake levels within each menstrual status category.

The association of dietary calcium and vitamin D intake with appendicular lean mass index, stratified by menstrual status.

Age, race, menstrual status, educational level, body mass index, sedentary behavior, calcium supplement use, vitamin D supplement use, dietary energy, dietary protein, dietary calcium, dietary vitamin D, and history of hypertension, diabetes, and cance were adjusted. Dietary calcium or dietary vitamin D is not adjusted for the analysis variable itself.

Discussion

Our study revealed no significant associations between dietary calcium or vitamin D intake and ALMI in middle-aged women—a finding robust across all subgroup analyses and consistent despite transient positive signals in preliminary models. The consistency of our null results across diverse population strata further challenges the hypothesis that dietary calcium or vitamin D independently influences ALMI in midlife women, emphasizing the need to reconsider their presumed mechanistic roles in muscle preservation during this critical transitional period.

The epidemiological landscape of calcium’s musculoskeletal effects remains complex and multifaceted. Previous research presents divergent perspectives: Seo et al.20 documented inverse associations between calcium intake and sarcopenia risk in elderly Koreans, while longitudinal data from the same population21 revealed sex-specific preservation effects exclusively among women. Our findings harmonize with European studies demonstrating negligible calcium-muscle mass relationships22,23. Critically, the overall nutritional context emerges as a crucial moderator of calcium’s physiological impact. Protein intake, for instance, appears fundamental in optimizing calcium’s muscle health benefits, with emerging evidence suggesting that protein can simultaneously enhance calcium absorption and muscle anabolism24,25. More research is needed to fully understand how dietary calcium interacts with other nutrients and biological factors to influence muscle health.

The relationship between vitamin D intake and muscle physiology presents an equally nuanced narrative. Existing evidence reveals a complex, often inconclusive picture26. A cross-sectional analysis of 1,989 community-dwelling women reported no significant association between low dietary vitamin D intake and reduced muscle mass27, a finding consonant with our current observations. Similarly, a randomized controlled trial involving overweight older adults with moderate vitamin D insufficiency demonstrated that dietary vitamin D supplementation offered no substantial benefits for muscle mass or sarcopenia prevention28. These persistent discrepancies likely stem from methodological variations, including differences in study design, sample characteristics, participant selection criteria, and the spectrum of adjusted confounding factors.

Paradoxically, while calcium and vitamin D are generally perceived as promoters of muscle function, our study unexpectedly observed a non-significant correlation with ALMI in middle-aged women. This apparent contradiction may be explained by recognizing that the relationship between dietary calcium, vitamin D, and muscle mass is governed by broader dietary patterns and energy balance, rather than isolated nutrient intake. Notably, high dietary calcium intake in the absence of caloric restriction may trigger increased fecal excretion of fat and energy, potentially indirectly modulating muscle mass through systemic body composition alterations29. Furthermore, vitamin D’s effect on muscle mass may be intricately mediated through insulin resistance mechanisms, with pronounced relevance in specific metabolic contexts such as diabetes or metabolic syndrome30,31. The potential risks associated with excessive calcium and vitamin D supplementation warrant careful consideration against their purported benefits32,33. Future investigative efforts should prioritize controlled interventional studies and advanced molecular approaches to comprehensively elucidate the multifaceted roles of calcium and vitamin D in maintaining muscle mass across women’s diverse life stages.

Despite the strengths of our study, including a large, nationally representative sample and the use of dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry for precise body composition measurements, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, The cross-sectional study design inherently limits causal inference between dietary calcium, vitamin D intake and appendicular lean mass index, preventing definitive mechanistic conclusions about nutrient-muscle mass relationships in middle-aged women. Second, Reliance on self-reported 24-hour dietary recalls introduces potential recall bias and measurement imprecision. Although the study utilized averaged recalls to enhance accuracy, this method may not comprehensively capture long-term dietary patterns or represent participants’ habitual nutrient consumption. Third, despite rigorous statistical adjustments, unaccounted confounding factors, particularly hormonal variations and metabolic parameters, might obscure nuanced relationships between nutritional intake and muscle mass composition. Fourth, while our study utilized a large, nationally representative sample of middle-aged women in the United States, the findings may not be generalizable to other populations with different dietary patterns, educational backgrounds, or geographical locations.

Conclusion

This study examined the relationship between dietary calcium, vitamin D, andALMI in middle-aged women. After full adjustment, no significant associations emerged, with consistent null findings across all subgroups. The observed data highlight the need for more comprehensive research to systematically explore nutritional mechanisms in midlife muscle metabolism.

Data availability

The data of this study are publicly available on the NHANES website (https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/index.htm).

References

Anagnostou, D. et al. Sarcopenia and cardiogeriatrics: The links between skeletal muscle decline and cardiovascular aging. Nutrients 17(2) (2025).

Betts, J. A. et al. Physiological rhythms and metabolic regulation: Shining light on skeletal muscle. Exp. Physiol. (2025).

Sriramaneni, N. et al. Quality of life in postmenopausal women and its association with sarcopenia. Menopause 31 (8), 679–685 (2024).

Lu, L. & Tian, L. Postmenopausal osteoporosis coexisting with sarcopenia: The role and mechanisms of estrogen. J. Endocrinol. 259(1). (2023).

Thornton, M. et al. Nutrition interventions on Muscle-Related components of sarcopenia in females: A systematic review of randomized controlled Trials[J]. Calcif Tissue Int. 114 (1), 38–52 (2024).

Park, J. M. et al. Effect size of dietary supplementation and physical exercise interventions for sarcopenia in Middle-Aged Women. Prev. Nutr. Food Sci. 26 (4), 380–387 (2021).

Tong, T. et al. Editorial: role of nutrition in skeletal muscle atrophy and sarcopenia. Front. Nutr. 11, 1395491 (2024).

Mithal, A. et al. Impact of nutrition on muscle mass, strength, and performance in older adults. Osteoporos. Int. 24 (5), 1555–1566 (2013).

Terrell, K., Choi, S. & Choi, S. Calcium’s role and signaling in aging muscle, cellular senescence, and mineral interactions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24(23). (2023).

Whitmore, C. et al. The ERG1a potassium channel increases basal intracellular calcium concentration and Calpain activity in skeletal muscle cells. Skelet. Muscle. 10 (1), 1 (2020).

Beaudart, C. et al. The effects of vitamin D on skeletal muscle strength, muscle mass, and muscle power: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 99 (11), 4336–4345 (2014).

Krasniqi, E. et al. Association between polymorphisms in vitamin D pathway-related genes, vitamin D status, muscle mass and function: A systematic review. Nutrients 13(9) (2021).

Cianferotti, L. et al. Nutrition, vitamin D, and calcium in elderly patients before and after a hip fracture and their impact on the musculoskeletal system: A narrative review. Nutrients 16(11) (2024).

Kirk, B., Prokopidis, K. & Duque, G. Nutrients to mitigate osteosarcopenia: the role of protein, vitamin D and calcium. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care. 24 (1), 25–32 (2021).

Fonte, F. K. et al. Relationship of protein, calcium and vitamin D consumption with body composition and fractures in oldest-old independent people. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN. 59, 398–403 (2024).

Capozzi, A., Scambia, G. & Lello, S. Calcium, vitamin D, vitamin K2, and magnesium supplementation and skeletal health. Maturitas 140, 55–63 (2020).

Guimarães, L. T. et al. Reliability between sarcopenia diagnosis by EWGSOP 1 and EWGSOP 2 criteria and association with clinical parameters in maintenance hemodialysis patients. J. Ren. Nutr. (2025).

Ahuja, J. K. et al. USDA food and nutrient databases provide the infrastructure for food and nutrition research, policy, and practice. J. Nutr. 143 (2), 241s–249s (2013).

von Elm, E. et al. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet 370 (9596), 1453–1457 (2007).

Seo, M. H. et al. The association between daily calcium intake and sarcopenia in older, non-obese Korean adults: the fourth Korea National health and nutrition examination survey (KNHANES IV) 2009. Endocr. J. 60 (5), 679–686 (2013).

Kim, Y. S. et al. Longitudinal observation of muscle mass over 10 years according to serum calcium levels and calcium intake among Korean adults aged 50 and older: the Korean genome and epidemiology study. Nutrients 12(9) (2020).

Verlaan, S. et al. Nutritional status, body composition, and quality of life in community-dwelling sarcopenic and non-sarcopenic older adults: A case-control study. Clin. Nutr. 36 (1), 267–274 (2017).

Ter Borg, S. et al. Differences in nutrient intake and biochemical nutrient status between sarcopenic and nonsarcopenic older Adults-Results from the Maastricht sarcopenia Study. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 17 (5), 393–401 (2016).

Gaffney-Stomberg, E. et al. Increasing dietary protein requirements in elderly people for optimal muscle and bone health. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 57 (6), 1073–1079 (2009).

Mangano, K. M., Sahni, S. & Kerstetter, J. E. Dietary protein is beneficial to bone health under conditions of adequate calcium intake: an update on clinical research. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care. 17 (1), 69–74 (2014).

Zhang, F. & Li, W. Vitamin D and sarcopenia in the senior people: A review of mechanisms and comprehensive prevention and treatment Strategies. Ther. Clin. Risk Manag. 20, 577–595 (2024).

Dupuy, C. et al. Dietary vitamin D intake and muscle mass in older women. Results from a cross-sectional analysis of the EPIDOS study. J. Nutr. Health Aging. 17 (2), 119–124 (2013).

Jabbour, J. et al. Effect of high dose vitamin D supplementation on indices of sarcopenia and obesity assessed by DXA among older adults: A randomized controlled trial. Endocrine 76 (1), 162–171 (2022).

An, H. J. & Seo, Y. G. Differences in Fat-Free mass according to serum vitamin D level and calcium intake: Korea National health and nutrition examination survey 2008–2011. J. Clin. Med. 10(22). (2021).

Takahashi, F. et al. Vitamin intake and loss of muscle mass in older people with type 2 diabetes: A prospective study of the KAMOGAWA-DM cohort. Nutrients 13(7) (2021).

Kim, Y. C. et al. Recent advances in nutraceuticals for the treatment of sarcopenic obesity. Nutrients 15(17) (2023).

Li, K. et al. The good, the bad, and the ugly of calcium supplementation: a review of calcium intake on human health. Clin. Interv Aging. 13, 2443–2452 (2018).

Muscogiuri, G. et al. Calcium and vitamin D supplementation. Myths and realities with regard to cardiovascular Risk. Curr. Vasc Pharmacol. 17 (6), 610–617 (2019).

Acknowledgements

The authors appreciate the time and effort given by participants during the data collection phase of the NHANES project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ZWL, FJ and CMZ contributed to data collection, analysis and writing of the manuscript. ZXZ contributed to study design, analysis, writing and editing of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The ethics review board of the National Center for Health Statistics approved all NHANES protocols and written informed consents were obtained from all participants.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lai, Z., Jin, F., Zhu, C. et al. No independent association between dietary calcium/vitamin D and appendicular lean mass index in middle-aged women: NHANES cross-sectional analysis (2011–2018). Sci Rep 15, 17290 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-02505-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-02505-x