Abstract

This study investigated the effect of the application of apatite (Ap), some amendments (zeolite and molasses), and some microbial inoculations (plant-growth-promoting microorganisms; including Claroideoglomus etunicatum, Serendipita indica, Enterobacter cloacae, and Brevundimonas sp) on P in organic (Po) and P in inorganic (Pi) fractions, alkaline phosphatase activity, and Sorghum bicolor L. (Speedfed cultivar) growth in sandy soil with pH 7.8. A factorial pot experiment in a completely randomized design was performed with three replications, using microbial inoculants (non-inoculated, Claroideoglomus etunicatum, Serendipita indica, Enterobacter cloacae, and Brevundimonas sp) and four amendments levels (control, Ap, Ap-Z (Ap-zeolite), and Ap-M (Ap-molasses)). Ap application increased all mineral fractions of P as follows: Ca10-P > Ca8-P > Ca2-P > Olsen P. Application of Ap-Z led to the increase of Olsen-P and Ca2-P to 1.21 and 1.67 fold as compared to Ap. Po was very low in soil, which was increased significantly with the application of amendments. In Ap-M treatments, the moderately labile Po and moderately non-labile Po increased significantly as compared to Ap treatments. Application of Ap-Z reduced pH more than Ap and Ap-M treatments. Furthermore, the largest amount of alkaline phosphatase was observed in Ap-M treatments. These findings show various mechanisms of microorganisms for using Ap in their metabolism in the presence of different amendments. Microbial inoculation (especially C. etunicatum) resulted in a decrease in pH and an increase in alkaline phosphatase. Application of amendments (Ap-Z and then Ap-M) resulted in better growth of Sorghum compared to control and Ap treatments. Application of Ap with zeolite and then molasses along with inoculation with plant-growth-promoting microorganisms were two useful solutions to improve the productivity of sandy soils.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

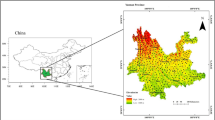

Khuzestan is a vast (64,057 km2) agricultural province in southwestern Iran. It has calcareous soils with low organic matter (0.1–1 percent). The province has five rivers, and most of the agricultural lands around the rivers are sandy. In sandy soils, several problems including the leaching of fertilizers into groundwater sources, low microbial population, low organic matter, low soil fertility, and low plant nutrition (especially P) limit crop productivity. Phosphorus is necessary for plants and plays an important role in the transfer of energy, photosynthesis, biosynthesis of macromolecules, and respiration1.

Apatite (Ap) (Ca10 (PO4)6 (OH, F, Cl)2) is the primary inorganic source of P is naturally present in most calcareous soils and is usually converted to different types of P fertilizers in industrial factories. Although Iran has P sources (such as Ap), it annually imports 1.5 million tons of phosphate rock for the production of P fertilizers2. Although the low solubility of Ap has discouraged its direct use as a P source in high pH soils3, but has the advantage that reduces P leaching in sandy soils. This study investigates the possibility of direct application of Ap and increasing its solubility using some chemical fertilizers or bio-fertilizers. Amendments such as zeolite and molasses are abundant in Iran and are relatively cheap (compared to phosphorus fertilizers which are likely to affect Ap solubility. Also, bio-fertilizers such as bacteria and fungi that have the potential to increase phosphorus availability could be a good choice for use with Ap.

Zeolites are crystalline hydrated aluminosilicate (clinoptilolite) minerals with high water-holding capacity in free channels and high adsorption capacity, making it especially interesting for agricultural purposes4. Some researchers have shown that zeolite can be used to reduce the need for phosphorus fertilizer in Zea mays L. cultivation5.

Molasses, an organic matter resulting from sugar extraction from sugarcane, can influence P availability by stimulating microbial activity, increasing immobilization and then mineralization of P, producing organic anions that could dissolve Ap, and covering soil surfaces that reduce P sorption on soil6. Molasses could increase soil organic P (Po) that plays an important role in the P cycle and is a source of P for plants7. Because of the large number of sugarcane factories in Khuzestan province, Iran, molasses could be used in agriculture at a very low cost.

Phosphate solubilizing microorganisms (PSMs), a group of soil microorganisms, play a key role in converting the insoluble P to soluble forms and in making them available for plants and microorganisms8. PSMs are divided into two groups including phosphate solubilizing bacteria and phosphate solubilizing fungi9. The mechanisms involved in phosphate solubilization take place via various microbial processes including the production of phosphatase enzymes and organic acids (such as lactic, malic, acetic, oxalic, and gluconic are produced by different bacterial species such as Bacillus sp., Azospirillum sp., Serratia sp. and Enterobacter sp.)10,11,12,13,14 and the extrusion of protons15. Microorganisms used for this study are PSMs, including Enterobacter bacterium16,17, Brevundimonas sp bacterium18, Claroideoglomus etunicatum fungus19,20, and Serendipita indica fungus21,22. Enterobacter cloacae and Brevundimonas sp were identified as plant growth promoting bacteria in previous studies23,24. Also Claroideoglomus etunicatum and Serendipita indica were identified as plant growth promoting fungi in a previous study (Jamili et al., 2025).

Sorghum bicolor L. (Speedfed cultivar) is a fast growth plant cultivated in Khuzestan province. Sorghum could forms symbiosis with mycorrhiza.

The aims of this study were: (1) to investigate the possibility of using Ap as P source in sandy soils, (2) to investigate the effects of amendments (molasses and zeolite) and the effect of microorganisms (C. etunicatum, S. indica, E. cloacae, and Brevundimonas sp) on organic (Po) and inorganic (Pi) P fractionation, and (3) to investigate the interaction of amendments and microorganisms on solubilizing inorganic P (Ap) in such soils and on Sorghum growth and P uptake by it.

Materials and methods

Soil sampling and amendments application

Pot culture experiment was conducted using a factorial experiment with two factors including microorganisms inoculation (non-inoculated, C. etunicatum, S. indica, E. cloacae, Brevundimona sp) and amendments (control, Ap (0.15%), Ap-Z (Ap (0.15%) + zeolite (0.3%)), and Ap-M (Ap (0.15%) + molasses (0.1%))) in a completely randomized design with three replications.

The soil was collected from a 0–30-cm depth of a sandy soil with low P content (total and Olsen P). Soil texture was determined using the hydrometer method25, calcium carbonate equivalent was determined according to26,Chapter 4), organic matter (OM) was determined by wet oxidation method27, pH and electrical conductivity (EC) were determined in 1:1 extract28, chapter 3), available P was determined by extraction with sodium bicarbonate29, total P was determined using the NClO4 digestion method30, and cation exchange capacity (CEC) was determined using the ammonium acetate method31. The physicochemical characteristics of the soil are presented in Table 1.

The major compounds contained in zeolite and Ap were measured using an inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometer (ICP-MS) at the central laboratory of Shahid Chamran University of Ahvaz. The elemental composition of zeolite and Ap are shown in Table 2. Zeolite was obtained from Afrazand mineral production company, Semnan province, Iran. X-ray diffraction (central laboratory of Shahid Chamran University of Ahvaz) properties show that zeolite includes 82.5% clinoptilolite, 8.6% quartz, 5.3% illite, and 3.5% feldspar. Phosphate rock (Ap) with particle size of 0.1–0.2 mm (95%) was obtained from Yazd’s Asfoordi phosphate mine, Yazd province, Iran.

Molasses was obtained from Karun agro-industriy of Shushtar, Khuzestan provine, Iran. Molasses is a by-product of sugar production from sugarcane. The total nitrogen content of molasses was measured using Kjeldahl method32. The organic carbon was measured using digestive method33. Electrical conductivity (EC) and pH were determined in 1:2.5 extract28, Chapter 3). Sample dehydration and subsequent furnace burning34 were used to measure the ash content. The properties of molasses are presented in Table 3.

Mineral amendments were applied to the soil and samples were moistened to field capacity and incubated for 30 days to achieve equilibrium. Molasses was applied after seed sowing with irrigation.

Microbial treatments

Sterile seeds (were sterilized using 50% hypochlorite sodium solution) of Sorghum bicolor L. (Speedfed cultivar) were germinated in sterile sands until roots grew up to 5 cm long. For the mycorrhiza-inoculated treatments, 5 spores (C. etunicatum species obtained from Turan Biotech Company, Shahrood, Iran) were placed on roots.

The endophytic fungus, S. indica, was provided by the department of plant pathology, Tarbiat modares University, Tehran, Iran (accession no.: IRAN 3239C). This fungus was propagated on potato dextrose agar medium (PDA medium) for 10 days. Then 10 mm mycelial discs were cut from 10-day-old PDA culture, and put in 100 ml of autoclaved potato dextrose broth medium and incubated for 7 days at 28 °C temperature (with continuous shaker) until a dense mycelial suspension was generated. Spores and mycelia were washed for removing PDB medium and were floated in distilled sterile water. For each 4 kg pot, a 3 ml inoculant containing 104 spores (cfu ml−1) was inoculated beneath the germinated seeds.

Brevundimonas sp. 16E (with an accession number of MN227292) and E. cloacae strain sug_1 (with an accession number of KX262849) were obtained from Shahid Chamran University of Ahvaz, Iran. The bacteria were reproduced in nutrient broth media (NB media) for 24 h and a 3 ml inoculant containing 106 (cfu ml−1) bacteria was inoculated beneath the germinated seeds. A 3 ml bacterial inoculant was sterilized and added to each of the control and fungal treatments.

Plant cultivation

Pots with 20 cm diameter and 25 cm height and capacity to contain 4 kg soil were chosen.

Pots were planted with 5 germinated seeds of Sorghum bicolor and were then transferred to a greenhouse with 28–40 °C air temperature and 14/10 h light/dark periods for 90 days (May to August) in 2019. Irrigation during the growing season was done each 6 days with deionized water. Irrigation was done at 70% of field capacity to prevent the draining of water from the pots. Soil moisture was measured using destructive pots during the plant growth. In such a way that by measuring the weight and humidity of the destructive pots, the amount of water needed to bring the soil to 70% of field capacity was calculated.

The chlorophyll index was measured (on day 60) using a portable electronic instrument (SPAD 502-Plus Chlorophyll Meter), and five readings were taken of leaves of the middle third of Sorghum shoots35. Plants were harvested (on day 90) and shoots and roots were separated and washed with distilled water. Parts of roots were stained with trypan blue and evaluated for fungal colonization (arbuscules, Vesicles, Hyphae and intraradical spors) by grid-line intersects method36. The shoots and the remaining parts of the roots were oven-dried at 70 °C for 72 h, weighed, powdered (0.5 mm), digested with 4 M nitric acid at 95 °C, and filtered with whatman 42 filter paper37. The P concentration of plant digests was measured by the vanadate-molybdenum approach using a spectrophotometer (APEL PD-3500-301) at 470 nm38. Standard solutions were prepared using K2HPO4 and used for spectrophotometer calibration. Ten blanks and ten selected samples were analyzed in duplicate for analytical QA/QC.

Analysis of soil properties

Soil samples were air-dried and the concentration of available P was determined by extraction with sodium bicarbonate29. Also, EC and pH of soil solutions were measured in a water-soil ratio of 1:1,28.

Total content of P in soil treatments was determined using nitric-hydrofluoric acid decomposition and molybdovanadate reagent method spectrophotometrically39,40.

Phosphatase determination

Alkaline phosphatases in soil samples were measured by adding 4 mL modified universal buffer with pH 11, adding p-nitrophenyl phosphate (as substrate) and toluene, incubating for 1 h at 37 ± 1 °C, extracting, and determining the p-nitrophenyl spectrophotometerically at 410 nm41.

Measurement of microbial biomass P

Microbial biomass P (Pmic) was measured by fumigating and extracting soil samples with 0.5 M NaHCO342,43. Determining the P concentration in extracts was done using the ascorbic acid method and the concentration of P is determined by spectrophotometrically at 882 nm44. Pmic was calculated as the difference between the P content of fumigated (by chloroform) and non-fumigated samples.

Inorganic P fractionation

Inorganic P fractionation in soil was determined using Jiang and Gu’s45 procedure as given in Table 4. After each step, the supernatant was centrifuged, filtered, and P concentration was determined in the extracts using the ascorbic acid method by spectrophotometrically at 882 nm44.

Organic P (Po) fractionation

Po fractionation was determined according to Boman and Cole’s (1978) procedure, modified by Ivanoff et al.46, and described by Zhang and Kovar47. A summary of the procedure is provided in Table 5.

Statistical analysis

The data were checked for normality (Shapiro–Wilk test) and homogeneity of variance (Levene’s test) and a two-way analyses of variance was done using SPSS (16.0) software. Duncan’s multiple range test (P < 0.05) was performed to test the significance of differences between the treatments.

Results

Figure 1 shows successful fungal colonization of Sorghum roots. Also, colonization for non-inoculated treatments was evaluated, which was minor probably because of using sandy and unfertile soil.

Phosphorus fractions

The means of total P contents of treatments were 34.1, 242.4, 238.7, and 234.3 mg kg−1 for Ap, Ap-Z,and Ap-M respectively. The sums of P fractions (except of Olsen P that has overlap with Ca2-P) were calculated. The recovery of P ranged from 93.2 to 106.7% indicated the efficiency of fractionation procedure.

The initial P content of sandy soil was very low (12–13 mg kg−1 inorganic and 17–28 mg kg−1 organic P) and with the application of Ap (Ap non-inoculated treatment), all P fractions increased significantly (the sum of 204 mg kg−1 for inorganic and 30 mg kg−1 for organic P) compare to control-non inoculated treatment (Table 6). The soil had a low content of organic matter and the application of Ap (Ap non-inoculated treatment) resulted in a distribution of P mainly in inorganic forms as Ca10-P (Ap phosphate) (48%), Ca8-P (octacalcium phosphate) (37%), Ca2-P (di calcium phosphate) (8%), Olsen P (7%). Also, the application of Ap (Ap non-inoculated treatment) resulted in a distribution of Po as non-labile R Po (residual Po) (35%), moderately labile Po (HCl-NaOH extracted organic P) (21%), moderately non-labile Po (fulvic acid organic P) (19.5%), labile Po (NaHCO3 extracted organic P) (17%), and non-labile H Po (humic acid organic P) (7.5%). Microbial inoculation of Ap treatments resulted in increases in Po (31–43 mg kg−1), especially for Enterobacter-inoculated treatment where non-labile H Po and moderately labile Po fractions increased significantly compare to Ap-non inoculated treatment. Moreover, microbial inoculation of Ap treatments resulted in significant increases in Ca2-P (especially in Enterobacter-inoculated treatment) and Olsen P (especially in C. etunicatum-inoculated treatment), but resulted in significant decreases in Ca10-P (particularly in Enterobacter-inoculated treatment) compare to Ap-non inoculated treatment.

Application of Ap-Z did not result in significant changes in Po fractions compared to corresponding Ap treatments (an exception is the moderately labile Po fraction which increased in Brevundomonas-inoculated treatment significantly). Ap-Z application resulted in significant increases in Ca2-P (especially in Enterobacter-inoculated treatment) and Olsen P (especially in Enterobacter- and C. etunicatum-inoculated treatments), but resulted in significant decreases in Ca10-P compared to corresponding Ap treatments.

Application of Ap and molasses (Ap-M) led to increases in total Po content of soil (62–71 mg kg−1) compared to the control (17–28 mg kg−1), Ap (30–43 mg kg−1), and Ap-Z (32–44 mg kg−1) treatments. Significant increases in Po fractions were observed in moderately labile Po and moderately non-labile Po fractions compared to corresponding Ap treatments. While Ap-M application resulted in significant increases in Ca2-P, it resulted in significant decreases in Ca10-P compared to corresponding Ap treatments.

Microbial inoculation resulted in significant decreases in Ca10-P, but resulted in significant increases in Ca2-P, Olsen P, and moderately labile Po fractions compared to corresponding non-inoculated treatments.

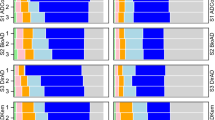

Relative contribution of P in Pi and Po (Fig. 2) shows that in control the most of p is as Po but by adding the Ap and Ap-Z, P concentrated much more in Pi. Although in Ap-M P concentrated in Pi, but the portion of Po is considerable.

Alkaline phosphatase and microbial biomass P

Alkaline phosphatase was increased significantly in the non-inoculated Ap treatment compared to the non-inoculated control (Table 7). Alkaline phosphatase did not show significant increases in Ap microbial inoculated treatments compared to corresponding control treatments (Table 7). Alkaline phosphatase was increased significantly in Ap-M treatments compared to control and Ap treatments.

Alkaline phosphatase was decreased in Enterobacter-, Brevundomonas-, and C. etunicatum- inoculated Ap-Z treatments compared to corresponding control treatments. Of all microbial treatments, Enterobacter- inoculated treatments showed the highest content of alkaline phosphatase.

Although Ap application did not cause a significant change in the content of microbial biomass P, Ap-Z application resulted in increases in microbial biomass P of non-inoculated (41.47%) and S. indica (5.54%) inoculated treatments compared to corresponding control treatments. Application of molasses resulted in a significant increase in microbial biomass P in the non-inoculated treatment (compared to the non-inoculated control). The application of Ap-M resulted in decreases in microbial biomass P compared to corresponding control, Ap, and Ap-Z treatments.

Microbial inoculation resulted in increases in microbial biomass P compared to non-inoculated treatments.

Soil pH

The pH of soil samples after plant harvesting was measured and the results (Fig. 3) show that pH decreased in P amendment treatments. Although zeolite was alkaline, Ap-Z treatments showed the lowest pH. Inoculation with Enterobacter (in control treatment; without amendments) and inoculation with C. etunicatum (in Ap and Ap-M treatments) caused a significant decrease in pH compared to non-inoculated treatments.

Effects of experimental treatments on plant characteristics.

Chlorophyll indices

Control treatments showed the lowest chlorophyll indices while the application of minerals, organic matter, and microorganisms caused a significant increase in this index (Fig. 4). Significant increases of chlorophyll indices were observed in Ap-Z and Ap-M treatments, which were higher than those of the control and Ap treatments. Inoculation with microorganisms resulted in a significant increase in chlorophyll compared to non-inoculated treatments in some cases. There was no significant difference between microbial inoculation treatments in any of the amendments.

Plant dry weight and P uptake

The results showed that microbial inoculation and the application of amendments significantly increased plant biomass and P concentration of shoot and root tissues compared to control treatments (Fig. 5). The application of Ap-Z showed the highest amounts of plant biomass, P concentration, and P uptake by plant tissues. There were increases in shoot and root dry weights, P concentration, and P uptake in microbial inoculated treatments compared to non-inoculated treatments. Inoculation with C.etunicatum, S. indica, and Entrobacter was more efficient in increasing the dry biomass of root and shoot compared to Brevundimonas and non-inoculation treatments.

The comparison of means of dry weight of root and shoot, P concentrations of root and shoot, and P uptake (mean ± (Sd)) of root and shoot in different amendments-inoculation interactions. The same letter indicates non-significant differences at P < 0.05. Ap, Ap (0.15%); Ap_Z, Ap (0.15%) + zeolite (0.3%); and Ap-M, Ap (0.15%) + molasses (0.1%).

Discussion

Phosphorus fractions

At this study soil had low content of P that was concentrated in Po (control treatments, Fig. 2). Also soil had low content of organic matter and by adding Ap (a mineral P source), P was concentrated in Pi fraction in Ap and Ap-Z treatments (Table 1 and Fig. 2). Although in Ap-M also P was concentrated in Pi, but the portion of Po is considerable. This indicates the importance of organic matters that affects distribution of P in organic or inorganic forms.

Pi fractions

Inorganic P fractionations45 include Ca2-P, Ca8-P, Al-P, Fe-P, O-P, and Ca10-P. Ca2-P (di-calcium phosphate) is more soluble fraction of P that can be readily taken up by plants and somewhat has overlap with Olsen P. The Ca2-P includes mono-calcium phosphate [Ca(H2PO4)2] and di-calcium phosphate (CaHPO4·2H2O) in the forms of water-soluble P, citrate-soluble P and partial surface-adsorbed P. Ca8-P (octa-calcium phosphate) (Ca8H2(PO4)6·5H2O) belonging to poorly soluble phosphorus that has lower solubility than Ca2-P, but its solubility is higher than Ca10-P (apatite-phosphate). Ca8-P can be used to some extent by plants. The Al-P (Al phosphates) and Fe–P (Fe phosphates) have low solubility in calcareous soils and also have limited plant bioavailability. O-P (occluded phosphorus) refers to phosphorus present within the mineral matrix of discrete mineral phases. O-P and Ca10-P (Ca10(PO4)6·(OH)2) fractions are difficult to be used by plants48,49.

At this study the Pi concentration in soil was as follows: Ca10-P > Ca8-P > Ca2-P > Olsen P. The concentration of trapped P in Al and Fe Oxides (O-P) was observed to be negligible. Hanley and Murphy50 investigated the distribution of inorganic P forms in the particles of some Irish soils and they found that Al-P, Fe-P, and Ca-P forms are high in clay and low in sand. Al-bound phosphate is a large source of P for herbaceous plants and can be depleted from soil by cultivating these plants51. Ma et al.52 reported significant depletion of Al-P in rice rhizosphere compared to uncultivated soil.

In this study, sandy soil with low P content, low CEC capacity, and low organic matter content was used. Application of Ap, Ap-Z, and Ap-M resulted in an increase in all mineral and organic P fractions. Xiao et al.53 showed that the application of phosphate rock resulted in an increase in the soluble P in the medium. The application of Ap-Z showed higher Ca2-P concentration compared to the control, Ap, and Ap-M treatments. Probably, this effect had been due to the type of zeolite (calcium type zeolite): its application along with Ap increases the possibility of the formation of unstable calcium phosphates. Application of Ap-M resulted in a significant increase of Olsen P and Ca2-P and a significant decrease in Ca8-P and Ca10-P (compared to Ap) (Table 6). In the current study, Ap was distributed mainly in Ca10-P and Ca8-P fractions that are insoluble forms, and plant available forms (Olsen-P and Ca2-P) had the lowest concentrations. It could be due to plant P uptake that is mainly of Olsen and Ca2-P types. Samadi54 showed that in the cultivated calcareous soil, Ca2-P form had the largest reduction due to plant uptake. Application of Ap-Z and Ap-M alongside microbial inoculation resulted in an increase of Olsen and Ca2-P forms and a decrease of Ca10-P form. Because of low clay content of sandy soil used in this study, the capacity for Olsen P is limited in this soil55,56. Therefore, the application of zeolite and molasses and microbial inoculation resulted in sharper changes in Ca2-P rather than Olsen P. Fan et al.57 used phosphate rock powders, active minerals (zeolite, kaolin, bentonite) and P-solubilizing microorganisms (Pseudomonas fluorescens, Aspergillus niger). Their results showed that the combined effect of phosphate rock powder and P-solubilizing bacteria led to a decrease in soil pH, promoted the release of available phosphorus, and consequently transformed soil phosphorus fractions and improved the use of phosphate rock powders.

Po fractions

Po includes labile, moderately labile, moderately non-labile, non-labile H, and non-labile R Po distributed in the forms of nucleic acids, phospholipids, inositol phosphates, sugar phosphates, condensed P, etc. Labile Po and then after moderately labile Po are the most active form of Po, which have high biological efficiency and can be hydrolyzed or mineralized, decomposed into soluble small molecule organic phosphorus or soluble phosphates. Other Po fractions have lower solubility and lower bioavailability58,59.

At this study Po increased following the application of Ap, Ap-Z, and Ap-M. Po forms were higher for Ap-M treatment (especially in labile, moderately labile, and moderately non-labile Po). Khan et al.,60 reported that the application of organic fertilizers along with rock phosphate significantly increased moderately labile Po in soil. Various studies have shown that organic fertilizers can increase labile Po in soil61,62. Saleque et al.63 stated that chemical and organic P fertilizers increase organic labile P. Moderately non-labile Po was also increased in Ap-M treatments. Reddy et al.64 and Yang et al.65 reported that organic fertilizers increase moderately non-labile Po in soil. These results indicate the effect of molasses on changing non-soluble P forms and translocation P into organic and Ca2-P forms. The negligible decline of Olsen P concentration in molasses treatments, as compared to Ap-Z treatments (Table 6), can be due to P immobilization. Biological immobilization is a short-term process which prevents long-term P stabilization by minerals. Akhtar et al.’s66 studies, examining the effect of organic materials on different forms of P, showed that adding organic matter to soil resulted in increases in organic P content. Generally, it seems that whereas adding phosphate rock powder (Ap) to soil increases its Ca10-P (Ap) content, the application of high ion-exchange adsorbents such as zeolite and organic matter such as molasses converts this form of P to more soluble forms.

Inoculation of microorganisms had no significant effects on Po forms compared to non-inoculated treatments. The only exception was Enterobacter which was more effective in increasing moderately labile and non-labile H Po forms compared to non-inoculated (in control, Ap, and Ap-Z) treatments. Considering the sum of all Po forms, the effect of microbial inoculation was significant in the increase of Po compared to non-inoculated treatments.

Moderately non-labile Po includes P associated with fulvic acid. This pool of P has no significant role in P nutrition64. Also, the P present in humic acids can be considered as non-labile Po, which does not easily get affected by mineralization processes, and for the same reason, it can not play a significant role in plant P nutrition67. No significant increase in non-labile H Po was observed because of the application of Ap, Ap-Z, and Ap-M treatments compared to the control treatment.

It seems that the application of Ap and soil amendments has led to decrease in soil pH; probably because of the release of anions into the soil. However, using organic matter (molasses) along with phosphate rock (Ap) seems to be a more effective way to increase soil organic P compared to a the application of a mineral (zeolite). Organic labile P, which can be adsorbed by minerals or organic matter in soils, is very dynamic in soils, plays an important role in P cycling, and can be easily affected by mineralization processes68. Therefore, a slight increase in this form can play a significant role in further mineralization and provides P for the plants69. While non-labile R Po is associated with highly stable organic constituents such as lignin and organometallic components, the organic P in this system is relatively stable. This may limit non-labile R Po mineralization and also reduce the contribution of this pool as a nutrient source70. Non-labile Po fraction can be considered as a long-term P storage but the labile Po is more likely to be readily mineralized to available forms for plant uptake71,72.

Alkaline phosphatase, microbial biomass P, and Soil pH

According to Table 7, microbial inoculation significantly increased microbial biomass P. Microorganisms, with their fast growth, can rapidly absorb P and concentrate it in their biomass73. Among amendments, Ap-Z followed by Ap-M showed the highest biomass P, and the least microbial biomass P was obtained in control and Ap treatments. This indicates the better condition of Ap-Z and Ap-M for microbial growth.

Molasses is an organic material and it is expected that Ap-M treatments would show higher microbial biomass and higher phosphorus availability, but they were higher in Ap-Z treatments. This could have several reasons, for example, molasses has a high EC (Table 3) which has negative effects on microorganisms, but zeolite has a high CEC which has positive effects on microorganisms. However, zeolite and then molasses treatments show high biomass phosphorus (Table 7); but probably have different types of microorganisms, which cause increased alkaline phosphatase in molasses and lower pH in zeolite.

Microorganisms significantly increased the alkaline phosphatase activity (Table 7). Such activities were observed significantly higher in the Ap-M and then the Ap treatments as compared to the control and the Ap-Z treatments. Rawat et al.74 in a review paper provides insights into the mechanisms used by phosphorus solubilizing microorganisms (PSMs) (including Enterobacter) to solubilize insoluble phosphates in soil. PSMs, employ various strategies such as secretion of organic acids, enzyme production, and excretion of siderophores to chelate metal ions and make phosphates available for plant uptake. These microbes not only enhance phosphorus solubilization but also promote plant growth by producing growth-promoting hormones and improving plant resistance to stress conditions74.

Although microbial P biomass was higher in Ap-Z, alkaline phosphatase in Ap-Z treatments showed no significant change (in non-inoculated and S. indica inoculated treatments) or was decreased (in Enterobacter, Brevundimonas, and C. etunicatum treatments) compared to Ap similar treatments. There might be three explanations for the decrease of alkaline phosphatase in Ap-Z treatments. First, clay minerals such as zeolite with high CEC could adsorb the enzymes on their exchange sites, which resulted in the reduction of enzyme activity. Gianfreda and Bollag75 stated that the adsorption of enzymes on the exchangeable surfaces of minerals is associated with a significant decrease in the activity of these enzymes. Zhu et al.76 showed that when goethite or montmorillonite was added to a phosphatase-containing solution, these enzymes were immediately adsorbed to minerals, so they suggested that some minerals could adsorb enzymes quickly and efficiently. Second, using the zeolite with high pH resulted in the decrease of pH probably because of acid and anion secretion and proton extrusion by plant roots and microorganisms. Crop growth is another factor which causes localized soil acidification as a result of nutrient uptake. Plants take up nutrients from the soil solution in ionic form with a preference for cations over anions, which leads to cation reduction in the soil77. To counteract the effect of charge imbalance, plants release H+ from roots to the rhizosphere, hence lowering soil pH. In addition, roots naturally exude organic acids which cause acidification of the soil77. In Ap-Z treatments, decrease of pH is probably more efficient in providing P compared to the production of alkaline phosphatase. The third explanation is that the largest amount of available P forms (Olsen and Ca2-P,Table 6) in all amendments associated with Ap-Z (due to high cation exchangeable capacity, other properties of zeolite, and a decrease in pH). So microorganisms did not need to produce large amounts of phosphatase enzyme in this treatment. In other words, microorganisms could recognize it was better to decrease pH in Ap-Z treatment rather than consume their energy to produce alkaline phosphatase. Widdig et al.78 stated that, inorganic P addition can reduce phosphatase activity in soils because organisms stop producing phosphatase when supplied with inorganic P. Thier study highlights the impact of nutrient additions (including inorganic P) on soil microbial communities and their functional genes related to P cycling.

The application of molasses, as an organic modifier, along with Ap showed the largest increase in alkaline phosphatase activity. Especially for Ap-M inoculated with Enterobacter, it was significantly higher as compared to other treatments. Wu et al.79 indicated the effects of different fertilization methods on phosphorus (P) forms and bacterial communities during the seedling stage of sugarcane. These researchers found that combined application of chemical fertilizer with moderate molasses increased phosphatase activity and sugarcane biomass and promoted the utilization of soil stable organic P by altering the bacterial community and soil properties. Also, Abdelgalil et al.80 indicated that sugarcane molasses as a low-cost and readily available raw material can be used for production of bacterial alkaline phosphatase in lab-scale.

Molasses may enhance phosphatase activity by microbial stimulation. When molasses is added to the soil, it serves as a food source for beneficial microorganisms that leads to higher production of phosphatase enzymes. Molasses indirectly influences Organic P availability by promoting microbial activity and organic matter breakdown. This makes molasses a valuable addition to soil for promoting nutrient cycling and plant health.

A decrease in pH could be because of higher plant growth in amendment treatments (Fig. 5) as well as higher microbial biomass in these treatments (Table 7). It is known that certain crop practices and plant species can influence soil acidity. Sorghum, being a C4 plant, has a high rate of photosynthesis and produce organic acids as part of their metabolic processes. Among the organic acids produced by sorghum, malic acid, citric acid, and oxalic acid are common81,82. Xiao et al.83 reported that using Aspergillus niger and phosphate rock significantly reduced pH, increased soluble P, and improved Sorghum growth. They attributed the decrease in pH mainly to the increase of organic acids produced by the fungus. Naryanasamy and Biswa84 reported that, during the decomposition process, the organic matter emits CO2 and produces carbonic acid, which causes a decrease in the pH, dissolves the phosphate rock, and increases the P supply from phosphate rock.

Effects of experimental treatments on plant characteristics

Chlorophyll indices

The increase in chlorophyll indices due to the used mineral (Ap) shows that the application of phosphate source in sandy soil can increase P and improve the chlorophyll indices of the plant’s leaves. Colomb et al.85 showed that application of P amendments resulted in an increase in plant growth, leaf area index, chlorophyll, and photosynthesis indices and subsequently caused yield increase. The increase of chlorophyll indices due to microbial inoculation could be the result of increasing the P uptake by the plants in these treatments. Fungi and bacteria inoculation increased plant photosynthesis by improving the availability of nutrients and water absorption, thereby increasing plant chlorophyll. Babadi et al.86, in their investigating of Sorghum under Cd stress, and Elhindi et al.87, by studying sweet basil (Ocimum basilicum L.) under salinity tension, reported that mycorrhizal fungi inoculation increased the chlorophyll indices compared to non-inoculated plants. Farghaly et al.88, in their study inoculated wheat (Triticum aestivum) plants with native mycorrhizal fungi. Their results indicated mycorrhizal inoculation significantly increased chlorophyll content of wheat and improved growth parameters, photosynthetic pigments, and nutrient availability, and mitigated the detrimental effects of alkalinity stress. The study of Liu et al.,89 indicated that arbuscular mycorrhizal colonization enhanced chlorophyll levels and improved plant growth and leaf gas exchange in both salt and non-salt stress conditions.

Plant dry weight and P uptake

Although the application of Ap increased plant dry biomass and P uptake compare to control (Fig. 5), but the application of Ap-Z and Ap-M resulted in higher increases in plant dry biomass and P uptake compare to Ap treatments. This indicate the effectiveness of using zeolite and molasses (especially zeolite) to increase plant availability of phosphorus from Ap. Bernardi et al.90 stated that the use of zeolite enrichment with Ap, in addition to reducing the leaching of nutrients in sandy soils, improves the efficiency of nutrients for plants.

The increase in root P amount due to C. etunicatum and S. indica inoculation may be because of the increased root uptake zone by fungal mycelium infiltration in soil which allowed the fungi, and thereby the plant, to access more soil elements especially P91.

In total, application of amendments in cultivated soil significantly increased all the fractions of inorganic P compared to control treatments. Using stimulants, especially zeolite followed by molasses, was very effective in increasing Ap solubilizing and better growth and P uptake of the plant. Even though mineral application (Ap-Z) increases inorganic P fractions, using organic amendments along with phosphate rock (Ap-M) seems to be a more effective way for increasing organic P in the soil. Also, the highest phosphatase activity was observed in the Ap-M treatment and the least was observed in the Ap-Z treatment. Changes in soil P fractions due to the inoculation of the plant with P solubilizing microbes indicate that these strains are efficient in dissolving phosphate rock. All microorganisms reduced soil pH and produced phosphatase enzymes. Enterobacter, C. etunicatum, and S. indica were more efficient in dissolving unsoluble P compounds and in increasing plant growth and P uptake compared to Brevundimonas. These strains converted the insoluble Ap to more soluble forms of P. Therefore, applying Ap and appropriate amendments such as modifiers and organic matter along with inoculating phosphate solubilizing microorganisms is an appropriate way of using Ap directly in nutrient-poor soils.

Conclusion

Regarding the sandy soil and the type of Ap used in this study, the results show that it is possible to increase soil productivity by direct use of Ap; this reduces the chemical processing costs of phosphate rock. Using a modifier with high cation exchange capacity (zeolite) or an organic amendment (molasses) along with phosphate rock is one way for dissolving and releasing P from Ap in Sorghum cultivation in calcareous soils. The results of this study indicate that using zeolite and then molasses as amendment along with using phosphate solubilizing microorganisms for dissolving and releasing P from Ap can be proposed as an effective method to enhance P efficiency in calcareous sandy soils. Since only one type of sandy soil was used in this study, it is recommended that these approaches be tested with other soil types, other plant species, and with different types of Ap.

Data availability

The data that support this study will be shared upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

References

Khan, M. S., Zaidi, A., Ahemad, M., Oves, M. & Wani, P. A. Plant growth promotion by phosphate solubilizing fungi–current perspective. Arch. Agron. Soil Sci. 56, 73–98. https://doi.org/10.1080/03650340902806469 (2010).

Salehi, F. et al. An evaluation of rose (rosa l. hybrids var. black magic) phosphorus feeding from different sources of iranian apatites in long periods in zeoponic culture. Aust. J. Basic Appl. Sci. 3(4), 4392–4396 (2009).

Sabah, N. U. et al. Biosolubilization of phosphate rock using organic amendments: An innovative approach for sustainable maize production in aridisols—A review. Sarhad J. Agric. 38(2), 617–625 (2022).

Mumpton, F. Uses of natural zeolite in agriculture and industry. Proc. Natl. Acad. U. S. A. 96, 3467–3470. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.96.7.3463 (1999).

Hasbullah, N. A., Ahmed, O. H. & Ab Majid, N. M. Effects of amending phosphatic fertilizers with clinoptilolite zeolite on phosphorus availability and its fractionation in an acid soil. Appl. Sci. https://doi.org/10.3390/app10093162 (2020).

Palm, C. A., Myers, R. J. K., & Nandwa, S.M. Combined use of organic and inorganic nutrient sources for soil fertility maintenance and replenishment. in replenishing soil fertility in africa. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. Spec. Publ. 51, 193–217. https://doi.org/10.2136/sssaspecpub51.c8 (1997).

Vincent, A. G., Turner, B. L. & Tanner, E. V. J. Soil organic phosphorus dynamics following perturbation of litter cycling in a tropical moist forest. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 61, 48–57. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2389.2009.01200.x (2010).

Whitelaw, M. A. Growth promotion of plants inoculated with phosphate-solubilizing fungi. Adv. Agron. 69, 99–151. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2113(08)60948-7 (2000).

Tallapragda, P. & Seshachala, U. Phosphate-solubilizing microbes and their occurrence in the rhizospheres of piper betel in Karnataka, India. Turk. J. Biol. 36(1), 25–35. https://doi.org/10.3906/biy-1012-160 (2012).

Behera, B. C. et al. Phosphate solubilization and acid phosphatase activity of Serratia sp. isolated from mangrove soil of mahanadi river delta, Odisha, India. J. Genet. Eng. Biotechnol. 15, 169–178 (2017).

Liang, J. L. et al. Novel phosphate-solubilizing bacteria enhance soil phosphorus cycling following ecological restoration of land degraded by mining. Int. Soc. Microb. Ecol. 14, 1600–1613 (2020).

Osorio, N.W., & Habte, M. Strategies for utilizing arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and phosphate-solubilizing microorganisms for enhanced phosphate uptake and growth of plants in the soils of the tropics. In Microbial Strategies for Crop Improvement, 325–351. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-01979-1_16 (Springer, 2009).

Tahir, M. et al. Isolation and identification of phosphate solubilizer Azospirillum, bacillus and Enterobacter strains by 16srrna sequence analysis and their effect on growth of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Aust. J. Crop Sci. 7, 1284–1292 (2013).

Wei, Y. et al. Effect of organic acids production and bacterial community on the possible mechanism of phosphorus solubilization during composting with enriched phosphate-solubilizing bacteria inoculation. Biores. Technol. 247, 190–199. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2017.09.092 (2017).

Khan, A., Jilani, G., Akhtar, M. S., Naqvi, M. S. & Rasheed, M. Phosphorus solubilizing bacteria: Occurrence, mechanisms and their role in crop production. Agric. Biol. Sci. 1(11), 48–58 (2009).

Borham, A., Blal, M., Metwaly, S. & Gremy, E. Phosphate solubilization by Enterobacter cloacae and its impact on growth and yield of wheat plants. J. Sustain. Agric. Sci. 43(2), 89–103. https://doi.org/10.21608/jsas.2017.1035.1004 (2017).

Singh, M. Isolation and characterization of insoluble inorganic phosphate solubilizer rice rhizosphere strain Enterobacter cloacae bau3. J. Appl. Nat. Sci. 10(4), 1204–1209. https://doi.org/10.31018/jans.v10i4.1929 (2018).

Ryan, M. P. & Pembrok, J. T. Brevundimonas spp: Emerging global opportunistic pathogens. Virulence 9(1), 480–493. https://doi.org/10.1080/21505594.2017.1419116 (2017).

Becquer, A., Trap, J., Irshad, U., Ali, M. A. & Claud, P. From soil to plant, the journey of P through trophic relationships and ectomycorrhizal association. Front. Plant Sci. 5, 548. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2014.00548 (2014).

Johri, A. K. et al. Fungal association and utilization of phosphate by plants: Success, limitations, and future prospects. Front. Microbiol. 6, 984. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2015.00984 (2015).

Xu, L., Wang, A., Wang, J., Wei, Q., and Zhang, W. Piriformospora indica confers drought tolerance on Zea mays L. through enhancement of antioxidant activity and expression of drought-Related genes. Crop J. 5(3), 251–258. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoleng.2008.04.001 (2017)

Zhang, F., Liu, M., Li, Y., Che, Y. & Xiao, Y. Effects of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi, biochar and cadmium on the yield and element uptake of medicago sativa. Sci. Total Environ. 655, 1150–1158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.11.317 (2018).

Pirhadi, M., Enayatizamir, N., Motamedi, H. & Sorkheh, K. Screening of salt tolerant sugarcane endophytic bacteria with potassium and zinc for their solubilizing and antifungal activity. Biosci. Biotechnol. Res. Commun. 9, 530–538 (2016).

Rezaeinasab, F., Enayatizamir, N., Zalaghi, R. & Moradi, N. Impact of phosphate dissolution microorganisms on mineral and organic forms of soil phosphorus and its availability under maize cultivation (Zea mays L). Appl. Soil Res. 9(1), 102–116 (2021).

Bouyoucos, C. J. Hydrometer method improved for making particle size analyses of soils. Agron. J. 54(5), 464–465 (1962).

Jackson, M. L. Soil Chemical Analysis (Prentice-hall, 1958).

Walkley, A. & Black, I. A. An examination of the degtjareff method for determining soil organic matter, and a proposed modification of the chromic acid titration method. Soil Sci. 37(1), 29–38. https://doi.org/10.1097/00010694-193401000-00003 (1934).

Gupta, I. C., Yaduvanshi, N. P. S. & Gupta, S. K. Standard Methods for Analysis of Soil, Plant, and Water (Scientific Publishers, 2012).

Olsen, S. R. Estimation of Available Phosphorus in Soils by Extraction with Sodium Bicarbonate (United States Department of Agriculture, 1954).

Bender, M.R., and Wood, C.W. 2000 Total phosphorus in soil. In 2000 Methods of phosphorous analysis for soils, sediments, residuals, and waters. Southern Cooper. Ser. Bull., vol. 396 (ed. Pierzynski, G. M.) 45–49.

Thomas, G. W. Exchangeable cations. In Methods of Soil Analysis, Part 2, Chemical and Microbiological Properties (eds Page, A. L. et al.) 159–165 (American Society of Agronomy and Soil Science Society of America, 1982).

Bremner, J. M. & Shaw, K. Denitrification in soil. I. Methods of investigation. J. Agric. Sci. 51, 22–39 (1958).

Wu, L., Ma, L. Q. & Martinez, G. A. Comparison of methods for evaluating stability and maturity of biosolids compost. J. Environ. Qual. 29, 424–429 (2001).

FSSAI. 2015. Manual of methods of analysis of food beverages (coffee, tea, cocoa, chicory) sugar and sugar products and confectionery products. Food Safety and Standards Authority of India, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare Government of India, New Delhi.

de Fatima Pedroso, D. et al. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi favor the initial growth of Acacia mangium, Sorghum bicolor, and Urochloa brizantha in soil contaminated with Zn, Cu, Pb, and Cd. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 101(3), 386–391. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00128-018-2405-6 (2018).

Grace, C. & Stribley, D. P. A safer procedure for routine staining of vesicular-arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. Mycol. Res. 95(10), 1160–1162 (1991).

Sposito, G. L., Lund, J. & Chang, A. C. Trace metal chemistry in aridzone field soils amended with sewage sludge: I. Fractionation of Ni, Cu, Zn, Cd, and Pb in solid phases. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 46, 260–265 (1982).

Chapman, H. D., Pratt, P. F. Methods of Analysis for Soils, Plants and Waters 62–66 (University of California’s Division of Agricultural Sciences, 1961).

Kitson, R. E. & Mellon, M. G. Colorimetric determination of phosphorus as molybdivanadophosphoric acid. Ind. Ind. Eng. Chem. Anal. Ed. 16, 379–383 (1944).

Sherrell, C. G. & Saunders, W. M. H. An evaluation of methods for the determination of total phosphorus in soils. N. Z. J. Agric. Res. 9(4), 972–979. https://doi.org/10.1080/00288233.1966.10429356 (1966).

Tabatabai, M. A. Soil Enzyme, Methods in Soil Analysis, Part 2: Microbiological and Biochemical Properties. https://doi.org/10.2136/sssabookser5.2.c37 (1994).

Brookes, P. C., Powlson, D. S. & Jenkinson, D. S. Measurement of microbial biomass phosphorus in soil. Soil Biol. Biochem. 14, 319–329. https://doi.org/10.1016/0038-0717(82)90001-3 (1982).

Jenkinson, D. S. & Pawlson, D. S. The effect of biocidal treatments on metabolism in soil.V. A method for measuring soil biomass. Soil Biol. Biochem. 8, 167–177. https://doi.org/10.1016/0038-0717(76)90005-5 (1976).

Murphy, J. & Riley, J. P. A modified single solution method for the determination of phosphate in natural waters. Anal. Chem. Acta J. 27, 31–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0003-2670(00)88444-5 (1962).

Jiang, B. & Gu, Y. A suggested fractionation scheme for inorganic phosphorus in calcareous soil. Fertil. Res. 20, 150–165. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01054551 (1989).

Ivanoff, D. B., Reddy, K. R. & Robinson, S. Chemical fractionation of organic phosphorus in selected histosols. Soil Sci. 163, 36–45 (1998).

Zhang, H., & Kovar, J. L. Fractionation of soil phosphorus. In 2009 Methods of phosphorus analysis for soils, sediments, residuals, and waters, 2nd ed. (eds. Kovar, J.L., and Pierzynski, G.M.). Southern Cooperative Series Bulletin No 408 (Virginia The University Press, 2009).

Khan, A. A., Jilani, G., Akhtar, M. S., Islam, M. & Naqvi, S. M. S. Potential of phosphorus solubilizing microorganisms to transform soil P fractions in sub-tropical Udic Haplustalfs soil. J. Biodivers. Environ. Sci. 7(3), 220–227 (2015).

Schrijver, A. D. et al. Four decades of post–agricultural forest development have caused major redistributions of soil phosphorus fractions. Oecologia, Springer Switzerland 169(1), 221–234 (2012).

Hanley, P. K. & Murphy, M. D. Phosphorus forms in particle size separate of irish soils in relation to drainage and parent materials. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. Proc. 34, 587–590. https://doi.org/10.2136/sssaj1970.03615995003400040015x (1970).

Grigg, J. L. Changes in Forms of Soil Inorganic phosphorus in lismore stony silt loam due to application of super phosphate to pasture. N. Z. J. Agric. Res. 9, 182–190. https://doi.org/10.1080/00288233.1966.10420772 (1966).

Ma, B., Zhou, Z. Y., Zhang, C. P., Zhang, G. & Hu, Y. J. Inorganic phosphorus fractions in the rhizosphere of xerophytic shrubs in the alxa desert. J. Arid Environ. 73, 55–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaridenv.2008.08.006 (2009).

Xiao, C. Q. et al. Optimization for rock phosphate solubilization by phosphate-solubilizing fungi isolated from phosphate mines. Ecol. Eng. 33, 187–193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoleng.2008.04.001 (2008).

Samadi, A. Contribution of inorganic phosphorus fractions to plant nutrition in alkaline calcareous soils. J. Agric. Sci. Technol. 8, 77–89 (2006).

Cao, N., Chen, X., Cui, Z. & Zhang, F. Change in soil available phosphorus in relation to the phosphorus budget in China. Nutr. Cycl. Agroecosyst. 94, 161–170 (2012).

Zhang, W. et al. The response of soil olsen-P to the P budgets of three typical cropland soil types under long-term fertilization. PLoS ONE 15(3), e0230178 (2020).

Fan, T. et al. Effect of phosphate rock powder, active minerals, and phosphorus solubilizing microorganisms on the phosphorus release characteristics of soils in coal mining subsidence areas. Polish J. Environ. Stud. 33(4), 4071–4082. https://doi.org/10.15244/pjoes/177435 (2024).

Wan, J., Yuan, X., Han, L., Ye, H. & Yang, X. Characteristics and distribution of organic phosphorus fractions in the surface sediments of the inflow rivers around Hongze lake, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17, 648. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17020648 (2020).

Worsfold, P. J. et al. Characterisation and quantification of organic phosphorus and organic nitrogen components in aquatic systems: A review. Anal. Chim. Acta 624, 37–58 (2008).

Khan, K. et al. Phosphorus solubility from rock phosphate mixed compost with sulphur application and its effect on yield and phosphorus uptake of wheat crop. Open J. Soil Sci. 7, 401–429 (2017).

Lopez-Pineiro, A., Cabrera, D. & Pena, D. Phosphorus adsorption and fractionation in a two-phase Olive mill waste amended soil. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 73, 1539–1544. https://doi.org/10.2136/sssaj2009.0035 (2009).

Verma, S., Subehia, S. K. & Sharma, S. P. Phosphorus fractions in an acid soil continuously fertilized with mineral and organic fertilizers. Biol. Fertil. Soils 41(4), 295–300. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00374-004-0810-y (2005).

Saleque, M. A. et al. Inorganic and organic phosphorus fertilizer effects on the phosphorus fractionation in wetland rice soil. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 68, 1635–1644. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0960-8524(00)00050-X (2004).

Reddy, D. D., Rao, A. S. & Rupa, T. R. Effects of continuous use of cattle manure and fertilizer phosphorus on crop yields and soil organic phosphorus in a vertisol. Bioresour. Technol. 75, 113–118. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0960-8524(00)00050-X (2005).

Yang, Ch., Yang, L. & Jianhua, L. Organic phosphorus fractions in organically amended soils in continuously and intermittently flooded conditions. J. Environ. Qual. 35(4), 1142–1150. https://doi.org/10.2134/jeq2005.0194 (2006).

Akhtar, M. S., Richards, B. K., Medrano, P. A., Degroot, M. & Steenhuis, T. S. Dissolved phosphorus from undisturbed soil cores: Related to adsorption strength, flow rate, or soil structure. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 67, 458–470. https://doi.org/10.2136/sssaj2003.4580 (2003).

Sharpley, A. N. Phosphorus cycling in unfertilized and fertilized agricultural soils. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 49, 905–911. https://doi.org/10.2136/sssaj1985.03615995004900040023x (1985).

Vu, D. T., Tang, C. & Armstrong, R. D. Changes and availability of p fractions following 65 years of p application to a calcareous soil in a mediterranean climate. Plant Soil 304, 21–33. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-007-9516-x (2008).

Cross, A. & Schlesinger, W. Biological and geochemical controls on phosphorus fractions in semiarid soils. Biogeochemistry 52, 155–172. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1006437504494 (2001).

Perkins, R. G. & Underwood, G. J. C. The potential for phosphorus release across the sediment-water interface in an eutrophic reservoir dosed with ferric sulphate. Water Res. 35, 1399–1406. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0043-1354(00)00413-9 (2001).

Cade-Menun, B. J. Characterizing phosphorus in environmental and agricultural samples by 31p nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Talanta 66, 359–371. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.talanta.2004.12.024 (2005).

Turner, B. L., Mahieu, N. & Condron, L. M. Phosphorus-31 nuclear magnetic resonance spectral assignments of phosphorus compounds in soil NaOH–EDTA extracts. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 67, 497–510. https://doi.org/10.2136/sssaj2003.4970 (2003).

Oberson, A., Friesen, K. D., Rao, I. M., Buhler, S. & Frossard, E. Phosphorus transformations in an oxisol under contrasting land-use systems: The role of the soil microbial biomass. Plant Soil 237(2), 197–210. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1013301716913 (2001).

Rawat, P., Das, S., Shankhdhar, D. & Shankhdhar, S. C. Phosphate-solubilizing microorganisms: mechanism and their role in phosphate solubilization and uptake. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 21(1), 49–681 (2021).

Gianfreda, L. & Bollag, J. M. Influence of natural and anthropogenic factors on enzyme activity in soil. In Soil Biochemistry (eds Stotzky, G. & Bollag, J. M.) 123–193 (Marcel Dekker Inc, 1996).

Zhu, Y. Y., Wu, F., Feng, W., Liu, Sh. & Giesy, P. Interaction of alkaline phosphatase with minerals and sediments: Activities, kinetics and hydrolysis of organic phosphorus. Colloids Surf. A 495, 46–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colsurfa.2016.01.056 (2016).

Tang, C., & Rengel, Z. Role of plant cation/anion uptake ratio in soil acidification. In Handbook of Soil Acidity (ed. Rengel, Z.) 57–81 (Marcel Dekker, 2003).

Widdig, M. et al. Nitrogen and phosphorus additions alter the abundance of phosphorus-solubilizing bacteria and phosphatase activity in grassland soils. Front. Environ. Sci. 7, 185. https://doi.org/10.3389/fenvs.2019.00185 (2019).

Wu, Q. et al. Combined chemical fertilizers with molasses increase soil stable organic phosphorus mineralization in sugarcane seedling stage. Sugar Tech. 25, 552–561 (2023).

Abdelgalil, S. A., Soliman, N. A., Abo-Zaid, G. A. & Abdel-Fattah, Y. R. Dynamic consolidated bioprocessing for innovative lab-scale production of bacterial alkaline phosphatase from Bacillus paralicheniformis strain apso. Sci. Rep. 11, 6071 (2021).

Ishikawa, S., Wagatsuma, T., Sasaki, R. & Ofei-Manu, P. Comparison of the amount of citric and malic acids in Al media of seven plant species and two cultivars each in five plant species. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 46(3), 751–758 (2000).

Panchal, P., Miller, A. J. & Giri, J. Organic acids: versatile stress-response roles in plants. J. Exp. Bot. 72(11), 4038–4052 (2021).

Xiao, C., Zhang, H., Fang, Y. & Chi, R. Evaluation for rock phosphate solubilization in fermentation and soil–plant system using a stress-tolerant phosphate-solubilizing aspergillus niger whak1. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 169(1), 123–133. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12010-012-9967-2 (2013).

Naryanasamy, G. & Biswa, D. S. Rock phosphate enriched compost: An approach to improve low-grade indian rock phosphate. Biores. Technol. 97(18), 2243–2251. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2006.02.004 (2006).

Colomb, B., Kinivy, R. & Debaeke, P. H. Effect of soil phosphorus on leaf development and senescence dynamics of field-grown maize. Agron. J. 25, 428–435. https://doi.org/10.2134/agronj2000.923428x (2000).

Babadi, M., Zalaghi, R. & Taghavi, M. A non-toxic polymer enhances sorghum-mycorrhiza symbiosis for bioremediation of Cd. Mycorrhiza 29(4), 375–387. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00572-019-00902-5 (2019).

Elhindi, K. H. M., Sharaf El-din, A. M., & Elgorban, A. The impact of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in mitigating salt-induced adverse effects in sweet basil (Ocimum basilicum l.). Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 170–179. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sjbs.2016.02.010

Farghaly, F. A., Nafady, N. A. & Abdel-Wahab, D. A. The efficiency of arbuscular mycorrhiza in increasing tolerance of Triticum aestivum L. to alkaline stress. BMC Plant Biol. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-022-03790-8 (2022).

Liu, M. Y. et al. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi inoculation impacts expression of aquaporins and salt overly sensitive genes and enhances tolerance of salt stress in tomato. Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40538-022-00368-2 (2023).

Bernardi, A. C., Oliviera, P., de Melo Monte, M. & Souza-Barros, F. Brazilian sedimentary zeolite use in agriculture. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 167, 16–21 (2013).

Devi, S. H., Bhupenchandra, I., Sinyorita, S., Chongtham, S., & Devi, E. L. Mycorrhizal fungi and sustainable agriculture. In Nitrogen in Agriculture, Physiological, Agricultural and Ecological Aspects (eds. Ohyama, T., & Inubushi, K.) (Intech Open, 2021). https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.99262.

Jamili, S., Zalaghi, R. & Mehdi Khanlou, K. Changes in microRNAs expression of flax (Linum usitatissimum L.) planted in a cadmium-contaminated soil following the inoculation with root symbiotic fungi. Int. J. Phytoremediat. 26(8), 1221–1230 (2024).

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to express their gratitude to Shahid Chamran University of Ahvaz, Iran, for their financial support of this work (Grant number: SCU.AS1400.28572). The authors also thanks Dr. Nader Rokni for providing the S. indica fungi.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

F.H. and R.Z. were done the experiment. R.Z. wrote the manuscript. N.E. reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hashemi, F., Zalaghi, R. & Enayatizamir, N. Using zeolite, molasses, and PGP microorganisms to improve apatite solubility and increase phosphorus uptake by Sorghum bicolor L. (Speedfed cultivar). Sci Rep 15, 19352 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-02511-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-02511-z