Abstract

Intestinal fibrosis represents a clinically intractable complication in colitis management. This study elucidates the regulatory mechanisms by which bone mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes (BMSC-Exo) modulate the myofibroblastic transdifferentiation of intestinal fibroblast. BMSC-Exo was isolated and characterized. RNA sequencing was performed on TGF-β-activated CCD-18Co fibroblasts following BMSC-Exo intervention. Histopathology, immunoblotting, migration assays, and imaging techniques (immunofluorescence/immunohistochemistry) were employed to quantify extracellular matrix (ECM) deposition and fibrotic responses in both in vitro and murine models. Human colonic specimens from Crohn’s disease (CD) patients with structuring complications were analyzed for fibrotic components. BMSC-Exo was successfully isolated. BMSC-Exo treatment significantly attenuated fibroblast activation and migratory capacity, concomitant with downregulating collagen I and N-cadherin expression. In vivo, histological fibrosis score, collagen deposition, and α-SMA expression were significantly decreased after BMSC-Exo administration. Transcriptomic profiling revealed significant enrichment of ECM remodeling pathways following BMSC-Exo intervention, with connective tissue growth factor (CCN2) identified as a pivotal mediator. Functional validation through CCN2 overexpression demonstrated the mechanistic dependence of BMSC-Exo’s anti-fibrotic effects on the CCN2-TGF-β axis. Clinical specimens revealed a marked increase in collagen fiber deposition and co-upregulation of CCN2 in stenotic CD tissues compared to non-strictured regions. BMSC-Exo exerts potent anti-fibrotic effects through the suppression of fibroblast differentiation, mediated by targeted inhibition of the CCN2-TGF-β signaling nexus. These findings establish exosome-based therapy as a novel therapeutic strategy for intestinal fibrosis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Intestinal fibrosis is recognized as a maladaptive pathological process of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) progression, driving irreversible tissue remodeling through extracellular matrix (ECM) deposition and architectural distortion. Clinical epidemiology reveals that approximately 50% of Crohn’s disease (CD) patients develop fibrostenotic complications or penetrating disease phenotypes1. Fibrostenotic CD correlates with elevated hospitalization rates, increased likelihood of corticosteroid dependence, and higher healthcare costs. Postoperative recurrence rates remain high despite optimized medical therapy2. Intestinal fibrogenesis in ulcerative colitis (UC) has been historically underappreciated compared to CD. However, Gordon IO et al. conducted a systematic histopathological evaluation of 706 surgically resected colonic sections from 89 UC colectomy specimens, demonstrating the universal presence of submucosal fibrosis in areas with active inflammation3. These findings underscore the fact that intestinal fibrosis is one of the most important clinical challenges in IBD.

Fibroblasts, serving as principal effector cells in gastrointestinal fibrogenesis and tissue repair, undergo pathogenic activation acquiring pro-fibrotic characteristics4. Emerging evidence delineates their pleiotropic roles in: (i) ECM homeostasis regulation, (ii) mucosal crypt morphogenesis maintenance, and (iii) immunomodulatory network coordination5,6. Fibroblast subpopulations and lineages within murine models exhibiting excessive collagen fiber deposition show upregulated expression of genes encoding matrix regulatory factors and ECM components5. Soluble mediators including growth factors and inflammatory cytokines collectively mediate fibroblast recruitment, phenotypic activation, and expansion to orchestrate mucosal restitution7. TGF-β emerges as the predominant molecular driver of fibrogenic programming. Mechanistically, N-cadherin-mediated intercellular adhesion facilitates targeted trafficking of activated myofibroblasts to sites of mucosal injury8. Therapeutic strategies directly inhibiting fibroblast-centric ECM dysregulation pathways warrant prioritized investigation.

Emerging evidence demonstrates that mesenchymal stem cell (MSC)-based therapies exert multifaceted therapeutic benefits in IBD, particularly through tissue regeneration and immunomodulatory mechanisms9. Preliminary investigations suggest MSC transplantation holds promise for mitigating intestinal fibrogenesis10,11,12. In a pivotal clinical trial involving CD patients, Panés et al. reported adipose-derived allogeneic MSCs significantly enhanced complex fistula closure rates10. Although clinical data remain limited, extant studies implicate MSC-mediated paracrine signaling in attenuating fibrotic progression. However, translational challenges persist, including oncogenic risks, immunogenicity concerns, and scalability limitations, driving increased focus on MSC-derived exosomes as cell-free therapeutic alternatives.

Exosomes are nanoparticulate extracellular vesicles (40–160 nm diameter) characterized by a phospholipid bilayer structure13. The anti-fibrotic potential of MSC-derived exosomes has been demonstrated across hepatic, cardiac, renal, and pulmonary systems12,14,15. Mechanistic studies reveal MSC-exosomes inhibit fibroblast activation and motility through targeted pathway modulation. BMSC-Exo specifically attenuates hypertrophic scar pathogenesis by regulating dermal fibroblast migration and suppressing profibrotic markers (α-SMA; COL1A1)16. While bone marrow-derived exosomes represent a readily accessible therapeutic source, their mechanistic role in intestinal fibrogenesis requires systematic elucidation.

This study posits that BMSC-Exo may attenuate intestinal fibrogenesis through targeted molecular modulation. We systematically investigated the therapeutic efficacy of BMSC-Exo in suppressing fibroblast-to-myofibroblast transition and colitis-driven fibrotic remodeling. Mechanistic analyses revealed BMSC-Exo administration significantly reduced ECM deposition within murine mucosal/submucosal compartments via selective inhibition of the CCN2-TGF-β signaling axis, a regulator of fibroblast activation. These findings establish BMSC-Exo as a novel biologics-based strategy for intestinal fibrosis intervention.

Materials and methods

BMSC isolation

Specific pathogen-free (SPF) sprague dawley (SD) male rats (4-week-old, 90–100 g body weight) were procured from HFK Bioscience (Beijing, China). BMSCs were aseptically isolated from femoral and tibial bone marrow using established protocols17. Cells were cultured in DMEM/F12 medium (Corning) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (HyClone) under standard culture conditions (37 °C, 5% CO2, 95% humidity). Medium replacement was performed every 48–72 h. Primary BMSCs (passage 0, P0) were defined as adherent cells remaining after initial medium replacement (48-hour post-plating). Cells underwent passage at 80–90% confluence using 0.25% trypsin-EDTA (Sigma), with fourth-passage (P4) cells utilized for subsequent experimentation.

BMSC-Exo isolation and characterization

P4 BMSCs were cultured in serum-free medium for 48 h. Exosomes were purified from conditioned supernatant via differential ultracentrifugation following Yuan et al.‘s protocol18. Sequential centrifugation included: 1000 × g for 10 min (cellular removal), 8000 × g for 30 min (debris clearance), and 130,000× g for 70 min (4 °C; Beckman Optima XE) with phosphate buffered saline (PBS)-washed pellet resuspension. Exosomal protein concentration was quantified using BCA assay (Beyotime, Shanghai) and stored at -80 °C.

For ultrastructural analysis, adsorbed exosomes were stained (2% phosphotungstic acid) and visualized by TEM (Hitachi HT-7800). Nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA; Beckman Coulter NS300) determined size distribution profiles (1:1000 dilution). Exosomal identity was confirmed via immunoblotting of conserved markers (CD9/TSG101).

BMSC-Exo labeling and cellular internalization assay

Exosomes were labeled with lipophilic fluorescent tracer DiI (Beyotime, Shanghai) at a 1:50 (dye: exosome) mass ratio under light-protected incubation for 20 min, followed by PBS dilution. Labeled exosomes were purified via ultracentrifugation (130,000 × g, 80 min, 4 °C; Beckman Optima XE). Fibroblasts seeded in 12-well plates were co-cultured with DiI-BMSC-Exo for 24 h. Post-incubation, cells were washed with PBS and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 20 min. Cellular membranes were permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 (Sigma), followed by nuclear counterstaining with DAPI (AntGene, Wuhan) and F-actin visualization using FITC-phalloidin (Beyotime, Shanghai). Internalization was assessed by confocal microscopy (Leica TCS SP8) using anti-fade mounting medium (Beyotime, Shanghai).

CCD-18Co cell culture and transfection

The CCD-18Co human intestinal fibroblast cell line (ATCC, https://www.atcc.org) was maintained in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM; Gibco) supplemented with 10% FBS (Gibco) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Gibco) under standard culture conditions (37 °C, 5% CO2). Experimental groups included: Control: Untreated cells; TGF-β group: 10 ng/ml recombinant human TGF-β1 (Peprotech) stimulation for 48 h; TGF-β + BMSC-Exo group: Co-treatment with TGF-β1 and BMSC-derived exosomes (20 µg/ml) for 48 h. For CCN2 overexpression, cells at 70% confluence were transfected with CCN2 overexpression plasmid (Genechem, Shanghai) using Lipofectamine™ 3000 (Invitrogen) per manufacturer’s protocol. Post-transfection, cells received designated treatments according to experimental groupings. All experiments were performed in triplicate with independent biological replicates.

Wound healing assay

CCD-18Co cells were seeded in 12-well plates and cultured to 80–90% confluence. Uniform linear wounds were created using a 200 µL sterile pipette tip under aseptic conditions. Following PBS washing, three experimental groups were established: Serum-free DMEM; 10 ng/ml TGF-β1 in serum-free DMEM; 20 µg/ml exosomes and 10 ng/ml TGF-β1 in serum-free DMEM. Phase-contrast microscopy (Olympus IX83) documented wound closure at baseline (T0) and 24 h post-treatment. Cells were fixed with methanol and stained with 1% crystal violet (Sigma) for migratory front visualization. Wound closure kinetics were quantified using ImageJ software (Media Cybernetics) via linear measurement of inter-wound distances.

Transcriptomic profiling

Total RNA was isolated from TGF-β/BMSC-Exo-treated cells using TRIzol™ Reagent (Invitrogen). RNA integrity (RIN > 8.0) and purity (A260/280 ≥ 1.8) were validated via Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies) and NanoDrop™ 2000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific), respectively. Strand-specific RNA-seq libraries were constructed with the VAHTS™ Universal V5 RNA-seq Library Prep Kit (Vazyme Biotech) following manufacturer specifications.

Paired-end sequencing was performed on Illumina NovaSeq 6000 (Illumina). Raw FASTQ files were quality-filtered using fastp. HISAT2 aligned clean reads to reference genome, with gene expression quantified as FPKM. Principal component analysis (PCA) of normalized counts was conducted in R (v3.2.0) using DESeq2-normalized data.

Differential expression analysis (|log2FC|>1, adjusted p < 0.05) was performed via DESeq2. Hierarchical clustering of significant DEGs (q < 0.05) employed Euclidean distance with complete linkage. GO and KEGG Pathway enrichment analysis of DEGs based on the hypergeometric distribution algorithm was used to filter for significantly enriched functional entries. Visualization included volcano plots, pathway bubble charts, and protein-protein interaction networks (STRING; https://string-db.org). Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) evaluated pathway-level perturbations. Raw sequencing data are deposited in NCBI SRA (PRJNA1211361).

Mouse model and experimental design

A murine model of colitis-associated fibrosis was established using 8-10-week-old male C57BL/6J mice (23–25 g; HFK Bioscience) randomly allocated into three experimental cohorts under specific pathogen-free conditions (n = 4). The DSS and DSS + BMSC-Exo group received four cycles of 3% dextran sulfate sodium (36,000–50,000 Da; MP Biomedicals) administered ad libitum for 7 days followed by 7-day recovery periods, while the control group maintained standard drinking water19. The DSS + BMSC-Exo cohort received intraperitoneal injections of 200 µg BMSC-Exo suspended in PBS every 72 h starting from day 14 post-induction, with vehicle controls administered to DSS and control groups. All animals were housed in controlled environments (22 ± 1 °C, 60–70% humidity, 12 h light/dark cycle) with free access to autoclaved feed and water. Terminal tissue collection was performed via cervical dislocation four days post-final DSS cycle. Distal colonic segments were either fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for paraffin embedding (histopathological analyses: hematoxylin & eosin (H&E), Masson’s trichrome, immunohistochemistry) or snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen for molecular assessments (qRT-PCR, Western blot). Experimental protocols received ethical approval from the Animal Ethics Committee of Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology (No.2022–3299), with strict adherence to ARRIVE guidelines and institutional animal care standards (https://arriveguidelines.org).

Live-animal imaging

Exosomes were labeled with lipophilic near-infrared fluorescent tracer DiR (Umibio, Shanghai) at a 10:1 (exosome: dye) mass ratio per manufacturer’s protocol through 30-minute incubation at 37 °C. Labeled exosomes were purified via ultracentrifugation (130,000 × g, 80 min, 4 °C; Beckman 70Ti rotor) to remove unbound dye, followed by PBS resuspension and protein re-quantification using BCA assay (Thermo Scientific). For biodistribution analysis, DIR-BMSC-Exo (200 µg/mouse) were intraperitoneally administered with longitudinal tracking via live imaging system (Bruker) at 24 h post-injection. Following terminal imaging, animals were humanely euthanized for organ-specific exosome localization assessment (small intestine/colon) using the same imaging platform. Distal colonic segments were cryosectioned for fluorescence microscopy to validate intracellular exosome localization via DiR signal.

Human tissue acquisition and processing

Surgically resected intestinal specimens were collected from 3 CD patients undergoing bowel resection. Tissue samples were obtained from macroscopically defined stenotic regions and adjacent non-stenotic areas (≥ 5 cm from stricture margin). Tissue segments were immediately fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) on ice for 24 h prior to paraffin embedding for histopathological evaluation (H&E, Masson’s trichrome) and immunohistochemical (IHC) analysis. The remainder was snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C. All experimental protocols were rigorously performed in accordance with internationally recognized ethical guidelines and institutional regulatory standards, following approval by the Independent Ethics Review Board of Wuhan Union Hospital (Approval No. 2018-S425). Written informed consent was obtained from all study participants prior to their inclusion in the research.

Histological assessment

Colonic tissues were processed through fixation, graded ethanol dehydration, and paraffin embedding. Serial Sect. (5 μm thickness) were prepared using a microtome and subjected to standard histological protocols. Deparaffinized sections were stained with H&E using Harris hematoxylin for nuclear basophilic staining and eosin Y for cytoplasmic counterstaining, followed by Masson’s trichrome staining to visualize collagen deposition through selective aniline blue binding. All stained sections were imaged under an Olympus BX53 brightfield microscope equipped with a digital camera. Collagen fractional area quantification was performed using ImageJ software (NIH) via color threshold analysis of aniline blue-positive regions. Fibrosis severity was histologically evaluated based on established criteria assessing collagen deposition patterns, tissue architectural remodeling, and mucosal-submucosal interface integrity20.

Immunofluorescence staining

Cells were cultured in 24-well plates and subjected to three 5-minute PBS washes. Sequential fixation (4% paraformaldehyde, 30 min) and permeabilization (0.3% Triton X-100, 30 min) were performed at room temperature. Non-specific binding sites were blocked with 1% donkey serum for 60 min at ambient temperature. Primary antibodies targeting α-SMA (Proteintech, 1:200) and CCN2 (Proteintech, 1:200) were applied overnight at 4 °C in a humidified chamber. Following PBS washes, Alexa Fluor-conjugated secondary antibodies (Proteintech, 1:200) were incubated for 1 h protected from light. Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI. Fluorescent images were acquired using an inverted microscope.

Western blotting

Cellular and murine intestinal tissue proteins were extracted using RIPA (Beyotime, Shanghai) supplemented with protease/phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (Epizyme, Shanghai). Protein concentration was quantified via BCA assay (Hycezmbio, Wuhan). Equal protein loads (30 µg/lane) were resolved on 10% SDS-PAGE gels (Vazyme, Nanjing) under reducing conditions and electrotransferred onto 0.45 μm PVDF membranes (Millipore, MA). Membranes were blocked with 5% non-fat dry milk in TBST (Tris-buffered saline with 0.1% Tween-20) for 1 h at room temperature. Primary antibodies against CD9 (Abmart, ), TSG101 (Abmart), N-cadherin (Proteintech), collagen I (Cell Signaling Technology), α-SMA (CST), TGF-β (CST), TGFβRII (CST, ), and CCN2 (Proteintech) were incubated overnight at 4 °C. After TBST washes, membranes were probed with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (anti-rabbit/mouse, CST) for 1 h at 25 °C. Protein bands were visualized using Chemiluminescent Substrate (Vazyme, Nanjing) and imaged on a chemiluminescence Imaging System (CLiNX, Shanghai) with automatic exposure optimization.

Quantitative reverse transcription PCR (qRT-PCR)

Freshly dissected colonic tissues were homogenized in TRIzol™ Reagent (Invitrogen) for total RNA isolation following the manufacturer’s protocol. RNA integrity was verified by spectrophotometric quantification (NanoDrop 2000, Thermo Scientific) with A260/280 ratios ≥ 1.8. First-strand cDNA synthesis was performed using PrimeScript™ RT Reagent Kit (Takara, Shiga) under optimized thermal cycling conditions. Quantitative PCR amplifications were conducted in triplicate using SYBR Green PCR Master Mix(Vazyme, Nanjing) on a LightCycler® 480 System (Roche). GAPDH (NM_002046) served as the endogenous control for normalization. Relative mRNA expression was calculated via the 2 − ΔΔCT method with geometric mean normalization. Primer sequences (Additional File 1: Table S1) were designed using NCBI Primer-BLAST.

IHC analysis

Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded colonic Sect. (4 μm) were subjected to deparaffinization through xylene gradients and rehydration via descending ethanol series. Antigen retrieval was performed by microwave heating in sodium citrate buffer (pH 6.0, 95 °C) for 20 min. Endogenous peroxidase activity was quenched with 0.3% H2O2 in methanol, followed by blocking with goat serum (AntGene, Wuhan) for 30 min. Primary antibodies against CCN2 (Proteintech) and TGF-β (Abcam) were applied overnight at 4 °C in a humidified chamber. Sections were incubated with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (AntGene) for 1 h at 25 °C. Diaminobenzidine (DAB) chromogenic development was performed for 5-minute incubation with hematoxylin counterstaining. Digital images were acquired using an Olympus BX53 microscope. Semiquantitative analysis of DAB-positive areas was conducted via ImageJ software.

Statistical analysis

Quantitative data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Intergroup comparisons were conducted using two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test, while multi-group comparisons were performed with one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). All statistical computations were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics 21 (v21.0, IBM Corp.) with α = 0.05 defining statistical significance. Cellular experimental data represent three independent biological replicates. Data visualization executed through GraphPad Prism 9.

Ethics statement

This study was reviewed and approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of Huazhong University of Science and Technology, and the Independent Ethics Review Board of Wuhan Union Hospital. As described in the ARRIVE guidelines and the declaration of Helsinki, all experiments were conducted in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Results

Successful isolation and fibroblast internalization of BMSC-Exo

BMSC-derived exosomes were purified to a concentration of 1.7 × 10¹¹ particles/mL. Transmission electron microscopy confirmed characteristic exosomal morphology with intact lipid bilayer membranes and cup-shaped ultrastructure (Fig. 1A). NTA demonstrated monodisperse distribution with peak hydrodynamic diameter at 134.6 nm (Fig. 1B). Immunoblot validation confirmed conserved exosomal markers CD9 and TSG101 expression (Fig. 1C), collectively verifying successful exosome isolation. Cellular internalization was assessed through DiI-labeled BMSC-Exo co-culture with CCD-18Co fibroblasts for 24 h. Fluorescence microscopy revealed intracellular accumulation of DiI + vesicles (Fig. 1D).

Characterization and internalization of BMSC-derived exosomes. (A) Morphology of BMSC-Exo observed by electron microscopy (scale bar = 100 nm). (B) Nanoparticle tracking analysis of BMSC Exo demonstrates a single-peak pattern. (C) Western blot analysis of BMSC-Exo protein markers TSG101 and CD9. (D) Confocal images of human fibroblasts CCD-18CO incubated with PBS, 10 ug/ml, 20 µg/ml PKH26-labeled BMSC-Exo for 24 h.

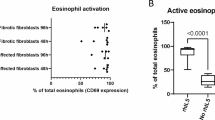

BMSC-Exo suppresses activation and migratory capacity of fibroblasts

To evaluate TGF-β-mediated fibroblast migration modulation, CCD-18Co cells were subjected to 10 ng/mL TGF-β stimulation with/without BMSC-Exo co-treatment. Quantitative wound closure analysis revealed TGF-β induced a 2.41-fold increase in migratory velocity (vs. control), which was attenuated by 2.1 times with BMSC-Exo intervention (vs. TGF-β group; Fig. 2A). Immunoblot analysis demonstrated concomitant downregulation of N-cadherin expression in BMSC-Exo-treated groups compared to TGF-β groups (Fig. 2B), indicating impaired migration progression.

BMSC-Exo treatment suppresses migration and activation in CCD-18Co fibroblasts. (A) Representative images showing the migration ability of fibroblasts (magnification, ×200). (B) The protein expressions of N-cadherin were determined using western blot analysis. (C) Representative images showing immunofluorescence staining for and quantification of α-SMA. (D)The protein expressions of collagen I, α-SMA, TGFβ, and TGFβR-II were determined using western blot analysis. n = 3; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Fibroblast activation status was interrogated through α-SMA immunofluorescence and fibrogenic protein profiling. TGF-β stimulation induced pronounced α-SMA expresson, which was substantially abrogated by BMSC-Exo treatment (Fig. 2C). Western blot quantification confirmed BMSC-Exo-mediated suppression of key fibrogenic effectors: collagen I, α-SMA, TGF-β, and TGFβRII compared to TGF-β controls (Fig. 2D). These findings collectively demonstrate BMSC-Exo exerts potent anti-fibrotic effects through dual inhibition of fibroblast activation and motility.

BMSC-Exo ameliorates dss-induced colitis-associated intestinal fibrosis

To investigate the anti-fibrotic mechanism of BMSC-Exo in vivo, a murine model of intestinal fibrosis associated with chronic colitis was established through DSS administration. BMSC-Exo labeled with the fluorescent dye DiR were intraperitoneally injected to evaluate biodistribution, with fluorescence imaging demonstrating successful intestinal targeting at 24 h post-injection (Fig. 3A). Immunofluorescence confirmed exosome distribution within intestinal tissues (Fig. 3B). BMSC-Exo administration significantly mitigated DSS-induced pathological features, including reduced body weight loss (Fig. 3C), attenuated colon shortening (Fig. 3D), and decreased colon weight-to-length ratio (Fig. 3E).

The therapeutic effect of BMSC-Exo on DSS-induced intestinal fibrosis in mice. (A) Representative images of DiR-labeled exosomes aggregated in the intestine using the Bruker platform. (B) Detection of DiR-labeled exosomes in the colon tissue slices by immunofluorescence staining. (C) The changes in body weight of mice from day 0 to day 54. (D,E) Colon length (D) and weight (E) of mice. (F) Images of H&E and Masson staining analysis of colon tissue sections. (G,H) Statistical chart of Masson-positive area (G) and fibrosis histology score (H) on colon samples of mice. (I) The mRNA expression levels of COL1α1, Timp1, and Fn in the colon from different groups. (J) Representative images showing IHC analysis of α-SMA in colonic sections (original magnification, ×200). n = 4; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Histopathological analysis via H&E and Masson’s trichrome staining revealed that BMSC-Exo intervention preserved mucosal architecture, and decreased collagen deposition compared to DSS-treated controls (Fig. 3F). Quantitative assessment of Masson’s staining indicated a significant reduction in collagen-rich areas (blue-stained regions) and fibrosis scores in the BMSC-Exo group (Fig. 3G, H). qRT-PCR analysis demonstrated downregulation of fibrosis-related markers, including collagen Iα1, TIMP1, and fibronectin, in BMSC-Exo-treated mice (Fig. 3I). Furthermore, BMSC-Exo markedly reduced α-SMA deposition in the colonic mucosa and submucosa (Fig. 3J), corroborating its ability to suppress fibrotic progression. These findings collectively indicate that BMSC-Exo attenuates intestinal fibrosis and pathological remodeling in DSS-induced chronic colitis.

BMSC-Exo modulates fibrosis-related genes in activated CCD-18CO

The observed suppression of fibroblast activation in CCD-18Co cells by BMSC-Exo prompted transcriptomic profiling to delineate TGF-β-mediated molecular alterations. RNA sequencing revealed distinct clustering patterns between TGF-β-stimulated and BMSC-Exo-treated groups through principal component analysis (Fig. 4A). Comparative analysis identified 416 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) meeting stringent thresholds (|log2FC|>0.58, p < 0.05), comprising 164 upregulated and 252 downregulated transcripts in BMSC-Exo-treated fibroblasts versus TGF-β controls (Fig. 4B). Hierarchical clustering of these DEGs demonstrated complete segregation between experimental groups, with heatmap visualization confirming regulation of BMSC-Exo (Fig. 4C).

mRNA-sequencing analysis of TGF-β-induced CCD-18Co treated with or without BMSC-Exo. (A) Principal component analysis (PCA) plot of TGF-β and TGF-β + BMSC-Exo groups. (B) Volcano plot of TGF-β and TGF-β + BMSC-Exo groups. (C) Heat map showing the genes among the TGF-β and TGF-β + BMSC-Exo groups. High-expression genes are indicated by orange bars in the figure, whereas low-expression genes are indicated by blue bars. (D) GO enrichment analysis plot of genes down-regulated by TGF-β + BMSC-Exo over the TGF-β group. (E) GSEA analysis of DEGs associated with fibrosis terminology. n = 3.

Functional annotation of downregulated DEGs through gene ontology (GO) enrichment analysis identified seven fibrosis-relevant terms among the top 30 enriched categories, including collagenous extracellular matrix, structural components of extracellular matrix, extracellular matrix, extracellular matrix organisation, cellular adhesion, stress fibres, and and cytoskeleton (Fig. 4D). Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) corroborated these findings, demonstrating significant negative regulation (FDR < 0.25) of core fibrotic pathways: extracellular matrix (GO: 0031012), collagen-containing extracellular matrix (GO: 0062023), stress fiber (GO: 0001725), and extracellular matrix structural constituent (GO: 0005201) (Fig. 4E). This multi-layered omics approach substantiates BMSC-Exo’s capacity to reprogram activated fibroblasts toward a quiescent phenotype.

CCN2 overexpression weakens the effect of BMSC-Exo on TGF-β-induced fibroblasts

To delineate the molecular mechanisms underlying BMSC-Exo’s anti-fibrotic effects, KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of downregulated genes identified critical signaling cascades including ECM-receptor interaction, TGF-β signaling, PI3K-Akt, and Hippo pathways and so on (Fig. 5A). Heatmap visualization of fibrosis-associated subgene clusters revealed coordinated downregulation of key mediators: CCN2, THBS1, FN1, TGFB1, TGFBAR1, SNAIL, SPEPINE1 and so on (Fig. 5B). Among these dysregulated mRNAs, CCN2, SERPINE1, and POSTN emerged as central hub nodes within the protein-protein interaction (PPI) network (Fig. 5C). Gene ontology (GO) analysis revealed CCN2 enrichment in fibrosis-associated biological processes, including extracellular region, extracellular space, cell-matrix adhesion, cell migration, extracellular matrix, collagen-containing extracellular matrix, and extracellular matrix constituent secretion.

The effect of BMSC-Exo on antagonistic fibrosis is related to CCN2. (A) Bubble diagrams showing the top 20 pathways between the TGF-β and TGF-β + BMSC-Exo groups (down-regulated genes). (B) The heap map of DEGs associated with fibrogenesis. (C) PPI interaction network map of critical genes. (D,E) The expression level of CCN2 was detected by Western blotting (D) and immunofluorescence (E) and quantified by ImageJ. n = 3; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Subsequent validation studies demonstrated TGF-β robustly induced CCN2 expression in CCD-18Co fibroblasts, which was significantly attenuated by BMSC-Exo treatment via immunoblotting (Fig. 5D) and immunofluorescence quantification (Fig. 5E). Functional interrogation through CCN2 overexpression (ov-CCN2) via plasmid transfection confirmed significant elevation of CCN2 protein expression compared to vector controls (ov-NC; Fig. 6A). Interestingly, ov-CCN2 significantly augmented TGF-β levels (Fig. 6B), suggesting CCN2 overexpression contributes to TGF-β aggregation. Strikingly, BMSC-Exo’s suppression of TGF-β-induced fibrotic markers - N-cadherin, α-SMA, and collagen I - was substantially abrogated by CCN2 overexpression (Fig. 6C). These data mechanistically position the CCN2-TGF-β axis as the critical signaling nexus through which BMSC-Exo exerts its anti-fibrotic effects.

BMSC-Exo inhibits CCD-18Co activation via CCN2 in vitro as evidenced by Western blotting analysis. (A,B) CCD-18Co representative immunoblot bands for the CCN2 (A) and TGF-β (B) proteins in fibroblasts between ov-NC and ov-CCN2 groups. (C) Western blot analysis of the Collagen I, N-cadherin, and α-SMA after CCN2 overexpression and stimulation of fibroblasts with TGF-β and BMSC-Exo. n = 3; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

CCN2-TGF-β axis underlies BMSC-Exo-mediated protection against intestinal fibrosis

To delineate the CCN2-TGF-β axis as the mechanistic cornerstone of BMSC-Exo’s anti-fibrotic activity, regulation of these mediators was investigated in DSS-challenged murine colons. IHC profiling demonstrated progressive CCN2 and TGF-β accumulation from mucosal to submucosal compartments in DSS-treated mice compared to non-fibrotic controls (Fig. 7A). BMSC-Exo intervention markedly reduced TGF-β+/CCN2 + cell populations, recapitulating in vitro findings of pathway suppression (Fig. 7B). Immunoblot quantification confirmed BMSC-Exo’s capacity to downregulate fibrotic effectors: collagen I, α-SMA, and N-cadherin in colonic tissues (Fig. 7C). These translational data conclusively establish BMSC-Exo-mediated inhibition of CCN2-TGF-β signaling as the pivotal mechanism attenuating intestinal fibrogenesis.

CCN2 plays a significant role in the anti-fibrosis process in vivo. (A) Detection of CCN2 and TGF-β expression by immunohistochemistry staining in the three different groups of mice. (B) Representative bands showing the expression of CCN2 and α-SMA in colonic sections. (C) Western blot and quantification results of Collagen I, N-cadherin, and α-SMA and Arg1 in mice. n = 4; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Enhanced collagen deposition and CCN2 overexpression in stenotic CD tissues

To validate clinical relevance, surgical specimens from CD patients were analyzed. Histopathological evaluation revealed significant crypt architectural distortion in stenotic regions, including focal crypt dropout and widened intervillous spacing (H&E; Fig. 8A). Masson’s trichrome staining demonstrated pronounced submucosal collagen accumulation (blue-stained regions) in stenotic segments (Fig. 8A). IHC profiling identified marked CCN2 upregulation in stenotic zones (Fig. 8B). Spearman correlation analysis revealed a significant positive correlation (r = 0.94, p = 0.02) between CCN2 immunoreactivity intensity and collagen deposition area (Fig. 8C), establishing a robust positive linear relationship between CCN2 expression and fibrotic burden in human CD tissues.

CCN2 expression is increased in the stenotic colonic tissues of patients with CD. (A) Representative images of H&E staining (×25), Masson’s trichrome staining (×25) in colon sections from non-stenotic and stenotic areas of patients with CD. (B) IHC staining for CCN2 in colon sections from non-stenotic control and stenotic areas of patients with CD (up × 100; down × 200). (C) Spearman’s correlation analysis of CCN2 expression level in intestinal tissues with the area of Masson staining-positive areas. n = 3; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

Discussion

This study demonstrates that BMSC-Exo effectively attenuate TGF-β-driven fibroblast activation and migratory capacity. Transcriptomic profiling revealed BMSC-Exo-mediated suppression of pro-fibrotic gene networks and critical regulatory pathways associated with ECM remodeling. In vivo investigations confirmed BMSC-Exo’s capacity to inhibit collagen deposition within mucosal and submucosal compartments, thereby mitigating intestinal fibrogenesis through targeted modulation of the CCN2-TGF-β signaling axis.

BMSC-Exo were isolated via differential ultracentrifugation and characterized using multimodal validation: NTA confirmed monodisperse vesicle populations (130 nm diameter approximately), TEM revealed canonical cup-shaped morphology, and immunoblotting verified enrichment of exosomal markers (CD9/TSG101). Fluorescent tracer studies demonstrated efficient fibroblast internalization in vitro and systemic biodistribution to intestinal tissues in vivo, establishing BMSC-Exo’s bioavailability for therapeutic targeting.

Intestinal fibrogenesis is principally driven by fibroblast activation and phenotypic transition. Extensive evidence implicates TGF-β as a master regulator of fibroblast migratory capacity through mechanotransductive signaling. Our findings demonstrate BMSC-Exo intervention effectively suppresses TGF-β-induced fibroblast motility concomitant with significant downregulation of N-cadherin, a calcium-dependent cadherin superfamily member critical for cell-cell adhesion and migratory plasticity21. This aligns with Burke et al.’s clinical observations of elevated N-cadherin expression in fibroblasts isolated from fibrostenotic Crohn’s disease lesions, correlating with enhanced migratory propensity22. While these data establish N-cadherin modulation as a key anti-fibrotic mechanism of BMSC-Exo, future investigations are warranted to delineate the specific exosomal cargo components mediating this regulatory effect.

Our data reveal BMSC-Exo treatment reverses TGF-β-induced α-SMA overexpression and collagen I deposition - a novel finding in fibroblast pathobiology. GSEA demonstrated coordinated downregulation of core matrisome components including collagen-containing ECM and ECM structural constituents. KEGG pathway analysis identified significant enrichment of TGF-β/Smad and Hippo signaling cascades - established mediators of fibrotic progression23,24,25. These multi-omics findings provide conclusive evidence that BMSC-Exo attenuates TGF-β-driven intestinal fibroblast activation through transcriptional reprogramming of profibrotic signaling networks.

Bioinformatic prioritization identified CCN2 as a central mechanistic node exhibiting statistically robust differential expression, positioning it as a prime therapeutic target. Functional annotation revealed CCN2 involvement in Hippo signaling and extracellular matrix restructuring pathways, consistent with its established role as a matricellular protein regulating cell proliferation, adhesion, and ECM remodeling across fibrotic pathologies24. The central pathogenic role of CCN2 in fibrotic disease progression has garnered significant scientific interest due to its prominent therapeutic implications. Convergent evidence from renal, cardiac, hepatic, and pulmonary fibrotic models demonstrates that CCN2 drives fibrogenesis through pleiotropic mechanisms26,27. For instance, conditional CCN2 knockout (cKO) murine models exhibit attenuation of folate-induced renal fibrosis via EGFR signaling axis modulation28. Clinically, a high-quality clinical trial demonstrated that anti-CCN2 monoclonal antibody therapy reduced idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis patients29, validating its therapeutic potential.

In gastrointestinal pathophysiology, CCN2 overexpression correlates with fibrostenotic progression in CD and UC30. Cross-disease meta-analysis identifies CCN2 as a conserved fibrotic node across eight distinct fibrotic disorders31, with mechanosensitive CCN2 production by intestinal smooth muscle cells driving collagen deposition32. Our data demonstrate BMSC-Exo suppresses TGF-β-induced CCN2 upregulation in activated fibroblasts, establishing CCN2 as the pivotal mediator bridging exosomal therapy to anti-fibrotic efficacy.

CCN2 expression is transcriptionally regulated by multifactorial inputs, including cytokine networks, hormonal axes, and growth factor cascades, with TGF-β emerging as a principal upstream regulator26. Critical functional studies establish CCN2 as a mediator of TGF-β-driven fibrotic responses33. Mechanistically, the von Willebrand factor type C (VWC) domain of CCN2 directly interacts with TGF-β, functioning as a co-chaperone to potentiate TGF-β signaling34. Our data demonstrate that TGF-β induces CCN2 upregulation in intestinal fibroblasts, establishing a feedforward loop whereby CCN2 amplifies TGF-β bioactivity. These mechanistic insights led us to hypothesize that BMSC-Exo attenuates intestinal fibroblast activation and ECM production through targeted disruption of the CCN2-TGF-β signaling circuit. Functional rescue experiments confirm this axis - CCN2 overexpression restoring TGF-β levels, nullifies BMSC-Exo’s anti-fibrotic effects and collagen deposition. These findings position the CCN2-TGF-β regulatory circuit as the linchpin mechanism through which BMSC-Exo attenuates fibroblast activation and ECM dysregulation.

In vitro investigations demonstrated that BMSC-Exo significantly attenuated colonic fibrogenesis in murine models. IHC profiling revealed the localization of CCN2 and TGF-β expression within mucosal/submucosal lamina propria, correlating with collagen-rich fibrotic niches identified by Masson’s trichrome histomorphometry. BMSC-Exo treatment significantly downregulated CCN2 and TGF-β expression in fibrotic colonic tissues compared to DSS groups. Concurrently, BMSC-Exo suppressed myofibroblast activation markers: α-SMA, collagen I, and N-cadherin. These translational findings mirror in vitro observations, mechanistically linking BMSC-Exo’s anti-fibrotic efficacy to targeted suppression of the CCN2-TGF-β signaling axis. To validate the clinical relevance of CCN2 in intestinal fibrogenesis, fibrostenotic CD surgical specimens were analyzed. IHC quantification demonstrated significant CCN2 upregulation in stenotic regions compared to adjacent non-stenotic tissues. Spearman correlation analysis revealed a strong correlation between CCN2 expression levels and collagen fiber deposition, establishing CCN2 as an actionable therapeutic target for mitigating intestinal fibrosis progression.

The therapeutic effects of mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) therapy are predominantly mediated through paracrine signaling mechanisms. Naoki Ishiuchi et al. demonstrated that hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) knockout in BMSCs significantly attenuated their capacity to inhibit TGF-β/Smad signaling, thereby diminishing their anti-fibrotic efficacy in renal fibrosis35. In proximal tubular epithelial cells, HGF acts as an upstream modulator to suppress CCN2 production, partially counteracting TGF-β-induced fibrotic responses36. However, whether analogous HGF-CCN2 crosstalk exists in MSC-mediated mitigation of intestinal fibrosis requires further experimental validation.

Extracellular vesicles (EVs), as key paracrine effectors, transfer bioactive cargo—including proteins, nucleic acids, and lipids—to target cells, orchestrating diverse biological processes. The low immunogenicity of MSC-derived EVs (MSC-EVs) has propelled their therapeutic exploration in graft-versus-host disease (GVHD), where EV-encapsulated miRNAs (e.g., miR-21, miR-223, miR-125, miR-1246) and proteins (PD-L1, Galectin-1, TGF-β, IL-10, IL-13, HLA-G) regulate adaptive T-cell responses and innate immune activation37. In fibrotic pathologies, MSC-EV-mediated anti-fibrotic effects are largely attributed to miRNA cargoes such as miR-21, miR-101a, miR-29a, and miR-let-7, which modulate fibroblast activation, epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), and immune regulation15. For instance, BMSC-EVs delivering miR-200b suppress intestinal fibrosis by targeting ZEB1 and ZEB2 to reverse EMT38. While the present study did not profile BMSC-Exo cargo, existing proteomic39 and miRNA-seq40 datasets catalog thousands of EV-associated biomolecules, providing a roadmap for mechanistic interrogation. Notably, CCN2 has been identified as a direct target of EV-encapsulated miR-15b-5p and miR-290a-5p41, and miR-214-3p suppresses uterine fibrosis via CCN2 3’UTR binding42, suggesting conserved miRNA-CCN2 regulatory axes across fibrotic contexts. Systematic characterization of BMSC-Exo cargo and its interplay with intestinal fibrogenic pathways remains critical to elucidate precise therapeutic mechanisms.

It is critical to emphasize the intricate interplay between fibrosis and inflammatory cascades in intestinal pathophysiology. MSC-EVs and their miRNA cargo have been extensively documented to downregulate pro-inflammatory cytokine production in IBD models9. However, clinical evidence indicates that anti-inflammatory monotherapy fails to alter the natural progression of established intestinal fibrosis20, suggesting MSC-EVs-mediated fibrotic mitigation involves mechanisms extending beyond immunomodulation. Our study elucidates the mechanistic basis for MSC-EVs anti-fibrotic activity. In vitro experiments demonstrated BMSC-Exo suppresses TGF-β-induced fibroblast activation and ECM synthesis, effects substantially abrogated by CCN2 overexpression. While MSC-EVs-mediated inflammation resolution may synergistically contribute to fibrosis attenuation, their capacity to directly modulate fibroblast activation states independent of inflammatory contexts remains to be definitively characterized. Further studies delineating the autonomy of MSC-EVs anti-fibrotic effects from immunomodulatory functions are warranted.

Notwithstanding these mechanistic insights, several limitations warrant consideration. First, the absence of CCN2-overexpressing murine models precludes definitive assessment of its role in BMSC-Exo-mediated anti-fibrotic effects in vivo, limiting mechanistic depth. Second, while the DSS-induced murine model recapitulates select fibrotic features, inherent species-specific differences create a translational gap between murine fibrogenesis and human fibrotic pathophysiology. Clinical validation of BMSC-Exo therapeutic efficacy in human intestinal fibrosis remains pending. Third, comprehensive exosomal cargo profiling is essential to delineate BMSC-Exo’s active ingredients. Systematic cargo-function mapping through loss/gain-of-function approaches (e.g., CRISPR-edited exosomes) could identify dominant anti-fibrotic mediators. Future investigations integrating multi-omics cargo analysis with human organoid-based fibrotic models may bridge these knowledge gaps while enhancing therapeutic translatability.

Conclusions

This study establishes CCN2 high expression as a pathological hallmark of intestinal fibrosis, observed in both fibrotic colonic tissues and activated fibroblasts. Therapeutic administration of BMSC-Exo significantly attenuated fibrotic progression through targeted modulation of the CCN2-TGF-β signaling axis, suppressing fibroblast migration, phenotypic activation, and profibrotic mediator synthesis. These findings position BMSC-Exo as a novel biological therapy capable of intercepting fibrogenic signaling cascades. Further preclinical optimization and human translational studies are imperative to advance this cell-free approach toward clinical application for fibrostenotic bowel diseases.

Data availability

The data presented in this study are all contained within the main body and supplementary information.

References

Wang, J. et al. Novel mechanisms and clinical trial endpoints in intestinal fibrosis. Immunol. Rev. 302, 211–227 (2021).

Dehghan, M. et al. Worse outcomes and higher costs of care in fibrostenotic Crohn’s disease: a real-world propensity-matched analysis in the USA. BMJ Open. Gastroenterol. 8, e000781 (2021).

Gordon, I. O. et al. Fibrosis in ulcerative colitis is directly linked to severity and chronicity of mucosal inflammation. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 47, 922–939 (2018).

Henderson, N. C., Rieder, F., Wynn, T. A. & Fibrosis From mechanisms to medicines. Nature 587, 555–566 (2020).

Jasso, G. J. et al. Colon stroma mediates an inflammation-driven fibroblastic response controlling matrix remodeling and healing. PLoS Biol. 20, e3001532 (2022).

Kinchen, J. et al. Structural remodeling of the human colonic mesenchyme in inflammatory bowel disease. Cell 175, 372–386e17 (2018).

Hayashi, Y. & Nakase, H. The molecular mechanisms of intestinal inflammation and fibrosis in Crohn’s disease. Front. Physiol. 13, 845078 (2022).

Jiang, D. et al. Injury triggers fascia fibroblast collective cell migration to drive Scar formation through N-cadherin. Nat. Commun. 11, 5653 (2020).

Tian, C. M. et al. Stem cell therapy in inflammatory bowel disease: A review of achievements and challenges. J. Inflamm. Res. 16, 2089–2119 (2023).

Panés, J. et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of stem cell therapy (Cx601) for complex perianal fistulas in patients with Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology 154, 1334–1342e4 (2018).

Lian, L. et al. Anti-fibrogenic potential of mesenchymal stromal cells in treating fibrosis in Crohn’s disease. Dig. Dis. Sci. 63, 1821–1834 (2018).

Gu, H., Li, J. & Ni, Y. Sinomenine improves renal fibrosis by regulating mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes and affecting autophagy levels. Environ. Toxicol. 38, 2524–2537 (2023).

Kalluri, R. & LeBleu, V. S. The biology, function, and biomedical applications of exosomes. Science 367, eaau6977 (2020).

Brigstock, D. R. Extracellular vesicles in organ fibrosis: mechanisms, therapies, and diagnostics. Cells 10, 1596 (2021).

Huang, Y. & Yang, L. Mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles in therapy against fibrotic diseases. Stem Cell. Res. Ther. 12, 435 (2021).

Zhang, H. et al. Exosome derived from mesenchymal stem cells alleviates hypertrophic Scar by inhibiting the fibroblasts via TNFSF-13/HSPG2 signaling pathway. Int. J. Nanomed. 18, 7047–7063 (2023).

Fan, M. et al. Glutamate regulates gliosis of BMSCs to promote ENS regeneration through α-KG and H3K9/H3K27 demethylation. Stem Cell. Res. Ther. 13, 255 (2022).

Yuan, M. et al. GelMA/PEGDA microneedles patch loaded with HUVECs-derived exosomes and Tazarotene promote diabetic wound healing. J. Nanobiotechnol. 20, 147 (2022).

Zeng, C., Liu, X., Xiong, D., Zou, K. & Bai, T. Resolvin D1 prevents epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and reduces collagen deposition by stimulating autophagy in intestinal fibrosis. Dig. Dis. Sci. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-021-07356-w (2022).

Johnson, L. A. et al. Intestinal fibrosis is reduced by early elimination of inflammation in a mouse model of IBD: impact of a ‘Top-Down’ approach to intestinal fibrosis in mice. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 18, 460–471 (2012).

Choi, S., Yu, J., Kim, W. & Park, K. S. N-cadherin mediates the migration of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells toward breast tumor cells. Theranostics 11, 6786–6799 (2021).

Burke, J. P., Cunningham, M. F., Sweeney, C., Docherty, N. G. & O’Connell, P. R. N-cadherin is overexpressed in Crohn’s stricture fibroblasts and promotes intestinal fibroblast migration. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 17, 1665–1673 (2011).

Li, J. et al. Pathogenesis of fibrostenosing Crohn’s disease. Translational Res. 209, 39–54 (2019).

Warren, R., Lyu, H., Klinkhammer, K. & De Langhe S. P. Hippo signaling impairs alveolar epithelial regeneration in pulmonary fibrosis. eLife 12, e85092.

Mia, M. M. et al. Loss of Yap/Taz in cardiac fibroblasts attenuates adverse remodelling and improves cardiac function. Cardiovasc. Res. 118, 1785–1804 (2022).

Fu, M., Peng, D., Lan, T., Wei, Y. & Wei, X. Multifunctional regulatory protein connective tissue growth factor (CTGF): A potential therapeutic target for diverse diseases. Acta Pharm. Sin B. 12, 1740–1760 (2022).

Ren, M. et al. Connective tissue growth factor: regulation, diseases, and drug discovery. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 25, 4692 (2024).

Rayego-Mateos, S. et al. Connective tissue growth factor induces renal fibrosis via epidermal growth factor receptor activation. J. Pathol. 244, 227–241 (2018).

Richeldi, L. et al. Pamrevlumab, an anti-connective tissue growth factor therapy, for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (PRAISE): a phase 2, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Respir Med. 8, 25–33 (2020).

di Mola, F. F. et al. Differential expression of connective tissue growth factor in inflammatory bowel disease. Digestion 69, 245–253 (2004).

Gu, C. et al. Identification of common genes and pathways in eight fibrosis diseases. Front. Genet. 11, 627396 (2021).

Lin, Y. M. et al. Mechanical stress-induced connective tissue growth factor plays a critical role in intestinal fibrosis in Crohn’s-like colitis. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 327, G295–G305 (2024).

Lipson, K. E., Wong, C., Teng, Y. & Spong, S. CTGF is a central mediator of tissue remodeling and fibrosis and its Inhibition can reverse the process of fibrosis. Fibrogenesis Tissue Repair. 5, S24 (2012).

Zaykov, V. & Chaqour, B. The CCN2/CTGF interactome: an approach to Understanding the versatility of CCN2/CTGF molecular activities. J. Cell. Commun. Signal. 15, 567–580 (2021).

Ishiuchi, N. et al. Serum-free medium and hypoxic preconditioning synergistically enhance the therapeutic effects of mesenchymal stem cells on experimental renal fibrosis. Stem Cell. Res. Ther. 12, 472 (2021).

Inoue, T. et al. Hepatocyte growth factor counteracts transforming growth factor-beta1, through Attenuation of connective tissue growth factor induction, and prevents renal fibrogenesis in 5/6 nephrectomized mice. FASEB J. 17, 268–270 (2003).

Fujii, S. & Miura, Y. Immunomodulatory and regenerative effects of MSC-Derived extracellular vesicles to treat acute GVHD. Stem Cells. 40, 977–990 (2022).

Yang, J. et al. miR-200b-containing microvesicles attenuate experimental colitis associated intestinal fibrosis by inhibiting epithelial-mesenchymal transition. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 32, 1966–1974 (2017).

Xu, X. et al. Quantitative proteomic analysis of exosomes from umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells and rat bone marrow stem cells. Proteomics 23, 2200204 (2023).

Lai, G. et al. BMSC-derived Exosomal miR-27a-3p and miR-196b-5p regulate bone remodeling in ovariectomized rats. PeerJ 10, e13744 (2022).

Yu, L. et al. Embryonic stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles rejuvenate senescent cells and antagonize aging in mice. Bioact Mater. 29, 85–97 (2023).

Zhang, Y. et al. Down-regulation of Exosomal miR-214-3p targeting CCN2 contributes to endometriosis fibrosis and the role of exosomes in the horizontal transfer of miR-214-3p. Reprod. Sci. 28, 715–727 (2021).

Funding

This work is supported by National Key R&D Program of China (2023YFC2507300), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82170547 and 82470562), Guangxi Natural Science Foundation (2024GXNSFBA010039 and 2024GXNSFBA010253).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

FL and WY contributed equally to this work. FL, WY performed the experiments and wrote the paper. WY conducted the bioinformatics analysis. FL and YC were responsible for the mouse feeding and model establishment. MY and JL were involved in data curation and analysis. JW guided the writing of the manuscript. LZ conceptualized the study and revised the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ling, F., Yang, W., Yuan, M. et al. Delivery of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes into fibroblasts attenuates intestinal fibrosis by weakening its transdifferentiation via the CCN2-TGF-β axis. Sci Rep 15, 18048 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-02971-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-02971-3

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Exploring the therapeutic potential of MSC-derived secretomes in neonatal care: focus on BPD and NEC

Stem Cell Research & Therapy (2025)