Abstract

Sense of coherence (SOC) is a global orientation that represents a core concept of the salutogenic model of health. No Polish version of the SOC questionnaire currently exists that has been validated on a representative sample. The aim of this study was to validate the Polish adaptation of the SOC-13 Scale, and to determine the role of sociodemographic variables and health situation on SOC. The study was cross-sectional with a longitudinal component. The sample comprised 1053 individuals and was representative of the Polish population with respect to age and sex. Confirmatory factor analysis and measurement equivalence analysis were conducted. The total group was divided into subgroups according to sex, age, marital status, occupational status, place of residence, and chronic condition for the sake of comparison. The time stability of the measurement was established using the test-retest method. The three-factor, nine-item version of the SOC-9-PL was found to exhibit the best psychometric properties. The analyses support the metric invariance of the scale structure across sex, age, education, and marital status. The SOC-9-PL achieves full measurement invariance across employment status, place of residence, time of measurement, and the presence of chronic disease. The overall measure is reliable (α = 0.82) and demonstrates high stability over a three-month interval (r = .69, p < .001). There is a positive correlation between SOC and age (r = .30, p < .001). Men have slightly stronger SOC than women (pdifference = 0.007, Cohen’s d = 0.16), employed persons exhibited stronger SOC than unemployed persons (pdifference = 0.002, Cohen’s d = 0.42), single persons declared weaker SOC than other marital groups (pdifference < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 0.62). When controlling for the age and sex of respondents, presence of chronic disease (β = − 0.12, p < .001) and single status (β = − 0.15, p < .001) were negatively correlated with SOC. The SOC-9-PL scale is a valid and reliable method for measuring sense of coherence. It can be used in the adult population, including both healthy individuals and those with chronic illnesses, and it can be applicable regardless of the sociodemographic status. The application of calculated for sex- and age-specific sten norms can be useful in the interpretation of results.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Sense of coherence (SOC) is a global orientation that represents a core concept of the salutogenic model of health1. According to the salutogenic model of health, an individual’s propensity for maintaining optimal health and well-being is contingent upon their sociocultural, historical context, general resiliency resources, and a sense of coherence2. SOC provides the individual with a sense of confidence that: (1) incoming stimuli from the internal and external environment are structured, predictable and explainable (comprehensibility); (2) resources are available to enable the individual to cope with the demands and stresses caused by the stimuli (manageability); (3) coping with demands and stresses is meaningful, and a challenge worth the effort and commitment (meaningfulness)1. SOC is shaped by life experiences, and an important role in its development is played by various socio-cultural factors that determine one’s life situation2, such as place of residence, age, sex, health, education, work, and family situation. Given the multidimensionality of SOC and the complexity of its underlying factors, its operationalization presents a considerable challenge. The present study is of need because, in Poland, differently than in other countries, there is a lack of contemporary studies on the salutogenic model of health, especially in representative samples, and on the operationalization of SOC. The Polish adaptation of the Sense of Coherence scale (SOC-29) was published in 19933. In Europe, the salutogenic approach is currently undergoing exploration and development. A review of the extant literature has emphasized the explanatory value of the salutogenic model of health and the positive relationship between SOC and subjective health and well-being4,5. The extant literature has demonstrated the applicability of the salutogenic approach and its predictive reliability in terms of SOC, particularly in the context of healthcare6, counseling7, employment8, and education9.

One of the most popular SOC measurement tools is the SOC-29 questionnaire1, consisting of 29 questions and statements about daily life. A shorter version is the SOC-13 questionnaire, which comprises thirteen questions and statements from the SOC-29, selected by Antonovsky10. Recent literature suggests that both tools are reliable and accurate11,12. Current research on the measurement of SOC has attempted to refine the SOC-29 Life Orientation Questionnaire and the SOC-13 short version10. In Poland, research on SOC has been primarily based on the SOC-29. However, (1) no Polish version of the SOC questionnaire currently exists that has been validated on a representative sample; (2) recent studies indicate the need for further validation of scales measuring SOC, especially the SOC-1313; (3) although previous studies have focused on the relationship between SOC, subjective health assessment and well-being14, less attention has been paid to the relationship between SOC and sociodemographic variables and indicators of health.

Study aim and hypotheses

The main aim of this study is to determine the psychometric properties of the Polish version of the SOC-13 scale and to examine the relationships between the SOC and the sociodemographic variables and chronic conditions reporting.

The first studies of the factorial validity of the SOC-29 scale in the Polish population were conducted on a sample of 523 women hospitalized after childbirth3, and on a sample of 1023 nurses15. The results suggest that the SOC-29 has a two-factor structure, i.e. with distinct meaningfulness and comprehensibility, which includes items from the manageability dimension. A further Polish study based on a sample of 983 adolescents identified one second-order factor and three primary factors, which corresponds to the theoretically-postulated scale structure1; the author recommends that the dimensions of comprehensibility and manageability can be interpreted as a single factor16. However, no coefficient was provided for the strength of the relationship between these two factors. These results highlight the need for a revision of the scale to improve its low theoretical and predictive validity, particularly in the context of health17. The SOC-13 has been found to exhibit a three-factor structure18, with the dimensions of comprehensibility and manageability exhibiting a strong correlation with each other. As previous research tends to suggest a three-factor structure for the SOC-13, our first hypothesis is:

H1

The three-factor model of the Polish SOC-13 scale will provide an acceptable fit to the data.

A crucial, yet frequently overlooked, indicator of measurement reliability is the invariance of the scale across sociodemographic variables. A confirmation of measurement equivalence irrespective of factors, such as age and sex, indicates that respondents exhibit a comparable comprehension of the assessed construct and questionnaire items. Additionally, the pattern of associations between scale items or subscales should remain consistent across diverse subgroups of respondents. Testing for measurement invariance is important because SOC could be determined by socioeconomic status and educational background1. Confirmation of construct and metric invariance could support the assumption that respondents from different social and cultural environments have a similar understanding of the scale items and measure construct. The test of scalar invariance is important to make a reliable comparison of SOC strength between people from different groups, such as employed and unemployed respondents. To date, no Polish studies have been conducted to verify the measurement equivalence of the SOC-13 scale. However, studies from other countries have demonstrated that the two-factor structure of the SOC-13 scale (meaningfulness, comprehensibility-manageability) is invariant across age and sex19,20. Given that SOC is a disposition shaped by social, economic, and cultural contexts, the present study aims to determine the full measurement invariance of SOC-13 with regard to sex, age, education level, marital status, occupational status, place of residence and time of measure. As SOC is known to be influenced by health indicators4,21, the structure of the SOC-13 scale was also compared between individuals with and without chronic illness to confirm full measurement invariance. To further understand the measurement equivalence of the SOC-13 scale, we have formulated an additional hypothesis:

H2

The three-factor structure of the SOC scale is full invariant with regard to sex, age, education level, marital status, employment status, place of residence, presence of chronic condition, and time of measurement.

According to the salutogenic model, the SOC is influenced by a variety of factors, including biological dispositions, personality traits, family and social roles22. The dependent variable on the aforementioned factors is sex. The difference in interpretation and response to life’s experiences, as well as in the assessment of available resources, is related to sex, and this is because women and men have different emotional responses to external stimuli23. Research has demonstrated that men tend to exhibit higher levels of self-esteem, self-efficacy, and internal locus of control compared to their women counterparts24. It is our contention that these differences may be significant in influencing the development of SOC. Indeed, research on adults indicates that men exhibit a stronger SOC than women12,25 and that a stronger SOC manifests in the male population as early as adolescence26. A comprehensive review of extant studies suggests that, in two-thirds of the studies reviewed, men had stronger SOC than women27. The hypothesis is as follows:

H3

The mean SOC is higher in men than in women.

The positive relationship between age and SOC has been extensively documented in the literature12,25,28. SOC itself is shaped by life experiences, with most change observed during younger life, and it believed to stabilize around the age of 301. More recent publications confirm that important life events can strengthen or weaken current SOC, but through learning processes, long-term SOC is positively related to age7. Studies on adult populations indicate that SOC is weakest in individuals approximately 20 years of age25, and it is assumed that individuals in middle adulthood may possess a stronger SOC than those in younger age groups. This may be attributed to the fact that individuals in middle adulthood have achieved a greater degree of stability in their professional and personal lives. In contrast, younger individuals may perceive the world and their place within it as less stable and consistent, perhaps because the period of young adulthood is characterised by a process of identity formation and the establishment of a stable self-image, as well as the formation of expectations regarding the self and others. In light of this aforementioned evidence, the following hypothesis was formulated:

H4

SOC is positively correlated with age.

Work activity, and its related self-esteem, security and stability, along with the resources gained from work, are important factors determining SOC29. Other studies have demonstrated a positive association between strong SOC with higher job satisfaction and work engagement30. Strong SOC is positively associated with stable employment and an upward career trajectory, while weak SOC is positively related with unemployment31,32. Previous Polish research among unemployed workers has focused on coping with unemployment and determinants of job search behavior33. The relationship between unemployment and SOC has not been studied in the Polish population. Hence, one aspect of the present study is to examine the differences in SOC between individuals who are currently employed and those who are not. The subsequent hypothesis is as follows:

H5

The mean SOC is higher in people who are employed than those who are not.

As a consequence of the increase in life expectancy, chronic diseases have become a more prevalent cause of mortality than acute diseases in developed countries34. Hence, the United Nations has highlighted the challenge posed by chronic diseases for sustainable development35. According to the salutogenic model, we can assume that chronic disease is related to life conditions and people’s experiences4. Chronic everyday illness can affect how someone sees their whole life and their own resources. People with long-term health problems probably have a harder time dealing with daily stress. Some of their negative experiences could be related to a weaker SOC. Prior research on a sample of persons diagnosed with chronic disease has demonstrated a positive correlation between SOC and psychological well-being, positive affect and meaning in life14. Nevertheless, the study did not explicitly address the relationship between SOC and the presence of chronic disease. In light of this possible relationship between general living situation, health, and SOC1, the present study examines whether the presence of chronic disease may be related to SOC. As such, we propose the following hypothesis:

H6

The presence of chronic disease is negatively related with SOC.

Methods

Study design and data collection

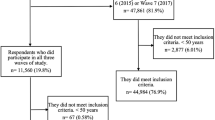

The study uses a self-reported design, and is both cross-sectional with a longitudinal component. Participants were recruited by an agency specializing in social research. Participation in the study was based on an online survey. No payment was made to participants for their participation in this study. The questionnaires have been designed so that answering all questions is mandatory. Failure to answer a question resulted in the survey being abandoned. Recruitment was based on the following criteria. The inclusion criteria comprised at least 18 years of age, Polish citizenship, permanent residence in Poland, use of Polish as a native language, consent to participate in the study. The exclusion criteria comprised incorrect response to attention check question and failure to complete all questionnaires. The attention check question was at the middle of the survey and was: “We want to make sure that your answers are correct and reliable. To do that, we need to check that you are focusing on this survey. If you are paying attention to this question, please choose number three”. We used the A-priori Sample Size Calculator for Structural Equation Models to calculate the sample size36. With an assumed effect size of 0.15, a desired statistical power of 0.80, and a significance level below 0.01, the recommended required count was 1046 observations. The final sample included 1053 individuals, indicating that the sample size was adequate. In these parameters, the minimum sample size was 100 observations. The following data were collected at two points separated by an interval of three months: SOC-13 score, sex, age, education, marital status, occupational status, place of residence and the presence or absence of a chronic disease, as indicated by the respondent. The data collected during the first measurement (T1) were used to check the factor validity and internal consistency of the SOC-13 scale, and to establish the relationship between the SOC score, and the sociodemographic variables and the declaration of chronic disease. The second measurement (T2) was collected to determine the temporal stability of the validated scale. To ensure the accuracy of the results, they were controlled for sex, age, education level, marital status, occupational status, place of residence, and declaration of chronic disease. Data collection occurred between May and August 2024. The study was conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Participants

The study sample consisted of N = 1053 people at time point T1, the sample being representative of the Polish population in terms of age and sex, and N = 853 people at point T2. All study participants were of legal age, were informed about the purpose of the study and the possibility of withdrawing. The study was voluntary and anonymous. All participants gave their informed written consent to participate in the study. The detailed sociodemographic characteristics of the study participants are presented in Table 1.

Measures

Sociodemographic variables and information on the declaration of the presence of chronic diseases were collected using a questionnaire of our own design. The SOC was measured with the SOC-13 questionnaire1, which in a previous study had been translated into Polish and approved by the author of the original version. The SOC-13 questionnaire consists of 13 items on various aspects of life. Five items deal with comprehensibility, e.g., “Do you have the feeling that you are in an unfamiliar situation and don’t know what to do?” Four items deal with manageability, e.g. “How often do you have feelings that you’re not sure you can keep under control?” Four items measure meaningfulness, e.g. “How often do you have the feeling that there’s little meaning in the things you do in your daily life?” Answers are given on a 7-point Likert-type scale. Some questions are reverse coded. The higher the score, the stronger the SOC.

Data analysis

Data analysis was performed using IBM SPSS and AMOS software. Data were examined using recommended statistical tests and cut-offs (e.g., skewness, kurtosis) and visual inspection of graphs (e.g., histograms and residual plots). No normality problems were found. Since the data were continuous, we used maximum likelihood to estimate the model. In the first step, the factor structure of the SOC-13 scale was checked using confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). The degree of model fit was assessed using the χ2/df, IFI (incremental fit index), TLI (Tucker-Lewis index), CFI (comparative fit index), RMSEA (root mean square error of approximation), SRMR (standardized root mean square residual), and the χ2 significance test. The convergent and discriminant validity of the latent variables was assessed by using the average variance extracted (AVE)37, and heterotrait-monotrait ratio of correlations (HTMT)38 coefficients. In the next step, the scale was subjected to measurement invariance analysis due to sex, age, education level, marital status, occupational status, place of residence, presence of chronic disease, and time using multi-group confirmatory factor analysis (MGCFA). The measurement invariance test compared the significance of the change in fit between the models tested due to the indicators Δχ2/df, ΔCFI. ΔRMSEA and ΔSRMR. Measurement invariance is assumed if Δχ2/df is not statistically significant, or ΔCFI ≤ -0.010, ΔRMSEA ≤ 0.015, ΔSRMR ≤ 0.03039. As initial testing found the presence of chronic disease to vary with age and sex, the subgroups were based on the remaining sociodemographic variables were then tested for consistency. In the final step, a series of intergroup comparisons were performed using Student’s t-test and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Sheffe’s test. In these comparisons, the scores were compared with regard to sex, age, education, marital status, occupational status, place of residence, and presence of chronic disease. The construct reliability was evaluated using Cronbach’s α, McDonald’s ω, and composite reliability (CR) measures. After establishing measurement invariance between the T1 and T2 measurements, the temporal stability of the scale was assessed using r-Pearson correlation coefficients. After establishing the structure of the scale and its relationship to the variables under study, the stens norms were calculated.

Results

The results of the factor validity and measurement invariance analyses

In the CFA, the SOC-13 scale was initially tested in a series of factor variants (Models 1a-e, as detailed in Table 2). The results of the CFA for the SOC-13 scale indicated that items 1–3 and 11 did not meet the requisite criteria for inclusion in subsequent stages of scale validation in the Polish version. Given the unsatisfactory fit indices of the SOC-13 scale and the factor loadings of items 1–3 and 11 (λ < 0.40), the abbreviated nine-item version of the scale was included in subsequent analyses (Models 2a-c, Table 2). The results of the CFA indicated that the most appropriate version of the validated scale was a nine-item version with a three-factor structure and correlated covariance errors, comprising items 5 and 6, and items 7 and 10 (numbering from SOC-13); this version was designated SOC-9-PL (Model M3, Table 2). The hypothesis that the best-fitted structure for the SOC-13 scale would be a three-factor structure was partially supported, as the best-fitting solution was a modified three-factor structure with four items removed. The removed items collectively explained a relatively small percentage of the SOC variance, as indicated by their low factor loadings and the high correlation between the SOC-13 scale and the SOC-9-PL scale (r = .95, p < .001). Although the three-factor structure had a satisfactory fit to the data, the dimensionality of the SOC-9-PL should be considered according to the limitations. The average variance extracted (AVE) was as follows: comprehensibility = 0.51, manageability = 0.32, meaningfulness = 0.36. Furthermore, the heterotrait-monotrait ratio of correlations (HTMT) was as follows: comprehensibility-manageability = 1.06, comprehensibility-meaningfulness = 0.62, manageability-meaningfulness = 0.89. According to recommendations38 HTMT should be less than 0.90, so this results suggest the very strong relationship between comprehensibility and manageability. The results of the factor analysis are presented in Table 2. The proposed structure of the SOC-9-PL scale is illustrated in Fig. 1.

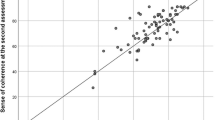

The results of the measurement invariance analysis demonstrated that the three-factor structure of the SOC-9-PL scale is invariant (metric invariance) with regard to sex, age, education level, marital status, occupational status, place of residence, presence of chronic disease, and time of measurement. The results of the analyses demonstrated that the SOC-9-PL scale is a reliable instrument (α = 0.82, ω = 0.83, CR = 0.85) and exhibits high temporal stability (r = .69, p < .001). The reliability indices for the subscales were as follows: comprehensibility (α = 0.74, ω = 0.76, CR = 0.75), manageability (α = 0.59, ω = 0.60, CR = 0.58), and meaningfulness (α = 0.59, ω = 0.60, CR = 0.60). The raw score for the SOC-9-PL scale is calculated by summing the scores for the individual items and dividing by the number of scale items. The range of possible raw scores for the overall SOC-9-PL scale thus ranges from 1 to 7. The results of the measurement equivalence analysis are provided in more detail in Table 3, and the items of the SOC-9-PL scale are presented in Table 4.

Preliminary analyses

The preliminary analyses indicated a positive correlation between SOC and age (r = .30, p < .001); however, after controlling for age, no statistically significant intergroup differences in SOC were observed with regard to place of residence or level of education. Interestingly, significant differences in SOC score were also observed between men and women; therefore, further analyses were performed to ascertain whether sex differences in SOC were also associated with age, education, marital status, occupational status, place of residence, or the declaration of a chronic disease. The analysis demonstrated that sex did not have any significant effect on the tested sociodemographic variables or the prevalence of chronic disease. Hence, no notable differences in SOC level were noted between men and women due to age, education level, marital status, occupational status, place of residence, or presence of chronic disease.

SOC, sociodemographic variables and prevalence of chronic disease

Women exhibited a slightly weaker SOC (M = 4.32, SD = 0.99) than men (M = 4.47, SD = 0.88, pdifference = 0.007, Cohen’s d = 0.16). The results of the one-way ANOVA revealed significant differences in SOC levels with regard to age: post hoc comparisons using Sheffe’s test found subjects aged ≥ 55 to have stronger SOC (M = 4.70, SD = 0.92) than persons aged 18–34 years (M = 3.99, SD = 0.85, pdifference < 0.001), 35–44 years (pdifference < 0.001), and 45–54 years (pdifference < 0.001). Respondents aged 45–54 years had significantly stronger SOC (M = 4.26, SD = 1.00) than those aged 18–34 (M = 3.99, SD = 0.85, pdifference < 0.036). Those aged 35–44 years had significantly stronger SOC (M = 4.28, SD = 0.86) than those aged 18–34 (M = 3.99, SD = 0.85, pdifference < 0.013). In multigroup comparison analyses, we compared four marital groups. We found significant differences in SOC between the group of single persons and persons in the other three groups. The single respondents have weaker SOC (M = 3.89, SD = 0.93), than persons with other marital status (M = 4.48, SD = 0.92, pdifference < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 0.62).

The analysis of the relationship between occupational status and SOC demonstrated that employed persons have a stronger SOC (M = 4.31, SD = 0.89) than those who are economically inactive (M = 3.89, SD = 1.07, pdifference = 0.002, Cohen’s d = 0.42). The presence of a chronic disease is negatively correlated with SOC (β = − 0.12, p < .001, 95% CI [0.112, 0.342]), and that being single was negatively associated with SOC (β = − 0.15, p < .001, 95% CI [0.249, 0.562]). Due to the modest, yet significant, differences in SOC strength between men and women, and the positive correlation between SOC and age, it was possible to establish norms for sex and age (Tables 5 and 6).

Discussion

This study determined the psychometric properties of the Polish version of the SOC-13 scale and estimated the relationship between total SOC score, sociodemographic variables and the presence of a chronic disease.

Hypothesis H1 posited that a three-factor structure of the SOC-13 would be the best fit to the data. Our findings partially support this hypothesis. Four items in the Polish version of the SOC-13 were found to demonstrate low factor loadings and so were excluded; the resulting nine-item pool was found to be the most accurate in a representative Czech sample12, and three of these four items were also excluded from the Norwegian version of the SOC-1340. The four excluded items in the Polish and Czech versions included “Until now your life has had: no clear goals and purpose/very clear goals and purpose” from the meaningfulness factor, while in the Norwegian version, this item was replaced with “Do you have the feeling that you don’t really care about what goes on around you?”. The latter was included in the Norwegian version despite its very low factor loading (λ = 0.20), which was confirmed in earlier studies41. The results of the CFA demonstrate that the best-fitting structure for measuring SOC in the Polish population is a three-factor scale consisting of nine items, with three items for each dimension. The reliability coefficients for manageability and meaningfulness are low, but they are still acceptable. The low Cronbach’s alpha for these two subscales could be due to the fact that some items are not well-correlated with the whole scale. For example, item 4 (item 1 in SOC-9-PL): “Until now, your life has had: (1 = No clear goals or purpose; 7 = Very clear goals and purpose)”. We saw that this item had the lowest factor loading. We did not exclude it like in the Norwegian version because we wanted to focus on the theoretical validity of the whole scale. This item is intuitive and closely related to meaningfulness. To put it simply, most people think that having goals in life means having a meaningful life. From a psychological perspective, having goals in life is one of the most important factors in human happiness and well-being42. The low reliability coefficients for manageability and meaningfulness may be attributable to the reversed coding of one item in each subscale. Studies show that reversed items are harder to understand, which can decrease the psychometric properties of the factor43. In similar language contexts, this item has satisfactory factor loading in the Slovenian18 and Czech12 versions of the SOC-13. In contrast, item 1 from SOC-13 had the lowest factor loading, similar to our study. The low factor loadings of the exluded items (1–3) could be due to the same reason, because these items are reverse coded and, according to the cited article, their consistency with other positions in the scale was poor. Low factor loading of excluded items could be due to low content accuracy. For example, item 11 (“When something happened, you generally found that:”), could be understood by participants as not related to the general meaning of comprehensibility or the sense of coherence in general. The content of the item could be the issue in other exluded intems e.g. item 3 (“Has it happened that people whom you counted on disappointed you?”). Antonovsky has created SOC scale items based on theoretical background and intuitions about the content of items that should reflect the SOC1. Previous studies using EFA16 or CFA12 have shown that not all items are empirically adequate for the SOC scale. Our study’s results are similar to those of earlier research. These findings also indicate that the operationalization of SOC needs to be clearer and more precise. We had to find a balance between the theoretical validity of the scale and its psychometric reliability. After looking at the results, we decided to remove some of the items with low loadings and low content adequacy.

The next finding to be discussed is that the three-factor model was modified by adding a correlation between errors. Correlated residuals were allowed for two pairs of items in SOC-9-PL: 2 (manageability) and 3 (comprehensibility), and 4 (meaningfulness) and 7 (manageability). The two pairs of items are from different factors, and the pattern of these relationships is similar to that described in previous research. Earlier studies suggest that the weakest extracted factor with the lowest reliability in the three-factor SOC-2916 or SOC-1318 is manageability. The intercorrelations can be interpreted within the framework of the salutogenic model. According to Antonovsky, the SOC is a multidimensional construct. However, it is important to note that the results of the SOC scales should be interpreted holistically, as the items share a common element1,10. The common element shared by items 2 and 3 is their focus on the social functioning of the person. The content of both items is centered on individual perception of social interactions and coping with the results of these interpretations. The correlation between items 4 and 7 can be explained by the fact that both items are focused on the assessment of successful coping with tasks. The content of both items could be interpreted as an assessment of self-effectiveness and feelings connected with this evaluation. The successful doing of things can be a source of pleasure and the feeling of a winner. The AVE coefficient for manageability and comprehensibility was lower than suggested (0.50). This could be due to the fact that one item in the comprehensibility and manageability subscale is reversed coded. When combinations of positive and reversed items are used in the same scale, the reliability of the whole scale or subscale is reduced and the unidimensionality of the factor is threatened by secondary sources of variance44. It is recommended that regular and reversed items be combined to control for response style bias, but cited work and our own case results have shown that the variance of scores is reduced in mixed-coded questionnaires. Therefore, the multidimensionality of SOC-9-PL is disputable, the HTMT for comprehensibility-manageablity factors was greater than 0.90. According to the results, we can say that the discriminant and convergent validity of the three factors were not fully supported. However, this solution fit the data relatively well, and the CR coefficients for all factors were at or close to the recommended level of 0.6037.

Our findings provide support for the proposed three-factor structure of the SOC scale, with strong correlations being found between the dimensions of comprehensibility and manageability, and manageability and meaningfulness18,41. The results confirm that the three dimensions of SOC are interrelated, and that the SOC-9-PL score should be interpreted as a total score for the sake of determining SOC10. Our findings are in accordance with the recent empirical evidence, which indicates that SOC should be conceptualized as a complex system composed of cognitive (comprehensibility), behavioral (manageability), and motivational dimensions (meaningfulness), which are intimately connected and not necessarily discrete45.

Hypothesis H2 states that the three-factor structure of the scale is fully invariant across sex, age, education, marital status, occupational status, place of residence, time of measurement and presence of chronic disease. The results partially support this hypothesis. The three-factor structure of the SOC-9-PL scale showed metric invariance for all tested sociodemographic variables, as well as the presence of a chronic disease and time of measurement. This suggests that all respondents have a similar understanding of the study construct and the SOC-9-PL test items, irrespective of sex, age, education, marital status, occupational status, place of residence, time of measurement and presence of chronic disease. Given that SOC scales are very often used in health and quality of life research4, it is of paramount importance to ascertain the residual invariance associated with the presence of chronic disease. The findings indicate that the SOC-9-PL scale is applicable to both respondents with chronic disease and those without. Similarly, scalar invariance was observed for occupational status, place of residence or the presence of a chronic disease, thus permitting a comparison of the mean SOC-9-PL scores between these groups46. However, the indicators of change in model fit do not provide definitive confirmation as to whether sex, age and education level also demonstrate scalar invariance. Current literature places the decision to confirm or reject measurement invariance at the discretion of the researcher, but recommend that such a decision should be based on a comparison of different model fit indices, taking into account inter alia model size, sample sizes, sizes of compared subgroups and statistical power47. The above results suggest unquestionable confirmation of metric invariance by sex, age, educational level, and marital status, and full invariance by employment status, place of residence, chronic disease, and time of measurement. Accordingly, the results of intergroup comparisons based on variables without confirmed scalar invariance should be interpreted with caution.

Hypothesis H3, stating that men demonstrate higher SOC scores than women was supported. Our results are in line with existing knowledge on sex differences in SOC12,25,27. While the effect was significant, it was also small, suggesting that the differences between men and women in SOC strength are minor. No significant differences were observed between men and women according to sociodemographic variables; i.e. the difference in SOC between sexes is not influenced by age, education, marital status, occupational status, place of residence or presence of chronic disease. It may be assumed that the observed differences in SOC strength in the study population are due to inter-sex differences in cognitive and social functioning23. One possible explanation may be the more frequent use of positive reformulation as a coping strategy by men48, and their less frequent use of strategies involving avoidance or denial behaviour compared to women49. Probably, men have a more stable and positive self-esteem. They are more sure that they have enough resources to deal with everyday stressors. The differences in how strong the SOC is between men and women can be explained by personality factors. Specifically, men tend to have stronger core self-evaluations24 and stronger social self-concept, persons’ beliefs about their abilities and confidence in social situations50. The observed differences in SOC strength may be attributable to disparities in affective dispositions among men and women. In nonclinical samples, women and girls reported higher levels of trait anxiety and depression symptoms48,51. To summarize, according to the salutogenic model, sex differences in SOC can be explained by the notion that men have a more coherent self-concept, lower emotional reactivity and a stronger belief that experiences and stimuli can be managed, comprehended, and given meaning.

Hypothesis H4 states that SOC is positively associated with age. Our results fully support this hypothesis, and these findings are consistent with those of previous studies12,40. The results indicate the strongest SOC among the ≥ 55 age group, and the weakest in the 18–34 age group. These findings agree with previous reports suggesting that the most pronounced differences in SOC strength are observed between the youngest and oldest age groups25. The results presented here confirm reports of a systematic increase in SOC after entering middle adulthood1. In the present study respondents aged 35–54 have stronger SOC than those aged 18–34, but their SOC is weaker than those aged ≥ 55. Arguably, this trend in SOC with age can be explained by the lower stability of psychological and socioeconomic variables among the 18–34 cohort. From the perspective of personality development, people with age rely more on their positive experiences and strengths, and less on the opinions of those around them. The prerequisites for the ability to adapt are an understanding of the world, competence and a sense of purpose.

Similarly, hypothesis H5 states that employed people have stronger SOC than unemployed people. Stability of employment is highly related to age, and those younger than 35 years may be particularly susceptible to labor market fluctuations. The results of our study confirm previous findings31, and underline the importance of job stability and related resources in shaping SOC29. The negative relationship between unemployment and SOC could be caused by the psychosocial consequences of unemployment. Unemployed people could have weaker SOC because of loss of benefits from employment such as income, social connections and status, and structured daily activities52. Unemployment can be understood as loss of control experience with is positively related with psychological state strongly interfering with psychological as well as social functioning e.g. apathy, disengagement and lower motivation for control-regaining efforts53.

Hypothesis H6 states that the presence of chronic disease is negatively related to SOC, regardless of sex and age. Our results support the existing literature on the significant relationships between SOC and subjective health assessment54,55. The observed negative association between chronic illness and SOC may be due to a lower quality of life among the chronically ill. Individuals who deal with health impairment on a daily basis may perceive their lives as harder and, in particular, less controllable. Single status was negatively associated with SOC. According to the salutogenic model, resources for coping with stress a.o. come from social support2. In light of the multidimensional nature of social support56, lack of partner support may be associated with lower health status57 and subjective well-being58. Being single may be positively associated with loneliness, which may be a potential stressor negatively associated with SOC59. Existing literature documented negatively relationship between lower perceived social support, emotional well-being, and single status60. Previous research has shown the positive relationships between perceived social support and SOC, and the negative correlation of these variables with depressive and anxiety symptoms61. Our findings indicate that presence of chronic disease, being unemployed or single are negatively related with SOC; this confirms the importance of resilience resources, such as objective health indicators and satisfaction of the need for interpersonal closeness, in building SOC2,7.

Strengths and limitations

The study’s principal strength is that the results are based on a representative sample of adult Polish citizens. The sample was selected in a manner that accurately reflects the characteristics of the Polish population. The study also controls for significant sociodemographic variables, eliminating alternative explanations for the hypotheses being verified. In addition, it ensures measurement reliability by confirming invariance in response to sociodemographic variables, and measurement stability by employing a longitudinal approach.

The present study is not without its limitations. One limitation of this study could be the questionnaire and the online nature of this study. This is especially the case as we investigated variables that are theoretically related to health. Our results were based on people’s subjective reports, such as whether they have a chronic condition. To reduce this bias, we used reliable statistical methods and followed rigorous research procedures. For example, we added an attention check question. These attention checks are especially important in online surveys, and we made the attention check question more reliable by giving a complete reason for it62. The potential issue is that the invariance analysis and the comparisons between groups may not have enough statistical power. For example, the number of people in some groups, like widowed people, might be smaller than what the sample calculator suggests. However, the results of the multigroup confirmatory factor analyses suggest that the tested models fit the data well. However, it’s important to remember that the results of these tests and comparisons should be generalizable within the context of the mentioned limitations. A next limitation of this study is that the differences in SOC strength between sexes and age groups have relatively weak effects and can be explained by variables that were not included in the study. Hence, it is important to exercise caution when generalizing differences, particularly between men and women. It is important to note that the presence of a chronic condition was declared by respondents, and no specific information on the type of diseases was collected. Another limitation is that the study does not assess the criterion and predictive accuracy of the SOC-9-PL scale. Given the longitudinal nature of this type of research and the constraints on the volume of scientific papers, this topic will be revisited in future studies by our team.

Conclusions

The short SOC-9-PL scale is a reliable questionnaire for measuring the general SOC construct. However, due to the highly correlated nature of the SOC model, the discriminant and convergent validity of the three factors were not fully supported. Despite these limitations, the psychometric properties of the SOC-9-PL were strengthened by analysis of measurement invariance, confirming that the scale is minimally biased by sociodemographic variables. Its full measurement invariance in the face of chronic disease and occupational status encourages its use in Occupational Health Psychology. Future research may focus on the relationship of SOC, as measured by the SOC-9-PL scale, with health and well-being. The SOC-9-PL has the potential to serve as a valuable instrument for psychologists and other healthcare professionals engaged in health and well-being research in various contexts.

Data availability

Some or all data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Antonovsky, A. Unraveling the Mystery of Health: How People Manage Stress and Stay Well (Jossey-Bass, USA, 1987).

Mittelmark, M. B. & Bauer, G. F. Salutogenesis as a theory, as an orientation and as the sense of coherence. In The Handbook of Salutogenesis (eds Mittelmark, M. B. et al. et al.) 11–17 (Springer, 2022).

Dudek, B. & Makowska, Z. Psychometric characteristics of the Orientation to Life Questionnaire for measuring the sense of coherence. Pol. Psychol. Bull. 24, 309–318 (1993).

Eriksson, M. The sense of coherence: The concept and its relationship to health. In The Handbook of Salutogenesis (eds Mittelmark, M. B. et al. et al.) 61–68 (Springer, 2022).

Eriksson, M. & Lindstrom, B. Antonovsky’s sense of coherence scale and its relation with quality of life: A systematic review. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 61, 938–944 (2007).

da Silva-Domingues, H. et al. Relationship between sense of coherence and health-related behaviours in adolescents and young adults: A systematic review. BMC Public Health 22, 477 (2022).

Langeland, E., Vaandrager, L., Nilsen, A. B. V., Schraner, M. & Meier Magistretti, C. Effectiveness of interventions to enhance the sense of coherence in the life course. In The Handbook of Salutogenesis (eds Mittelmark, M. B. et al. et al.) 201–219 (Springer, 2022).

Jenny, G. J. et al. Applying salutogenesis in the workplace. In The Handbook of Salutogenesis (eds Mittelmark, M. B. et al. et al.) 321–336 (Springer, 2022).

Omiya, T., Deguchi, N. K., Togari, T. & Yamazaki, Y. A study on the examination of sense of coherence-related factors in Japanese junior high school students and their mothers. Sci. Rep. 12, 4208 (2022).

Antonovsky, A. The structure and properties of the sense of coherence scale. Soc. Sci. Med. 36, 725–733 (1993).

Eriksson, M. Validity of Antonovsky’s sense of coherence scale: a systematic review. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 59, 460–466 (2005).

Tušl, M., Šípová, I., Máčel, M., Cetkovská, K. & Bauer, G. F. The sense of coherence scale: psychometric properties in a representative sample of the Czech adult population. BMC Psychol. 12, 293 (2024).

Eriksson, M. & Contu, P. The sense of coherence: Measurement issues. In The Handbook of Salutogenesis (eds Mittelmark, M. B. et al. et al.) 79–91 (Springer, 2022).

Krok, D. Sense of coherence and psychological well-being among coronary heart disease patients: A moderated mediation model of affect and meaning in life. Curr. Psychol. 41, 4828–4836 (2022).

Koniarek, J., Dudek, B. & Makowska, Z. Kwestionariusz Orientacji Życiowej. Adaptacja the Sense of Coherence Questionnaire (SOC) A. Antonovsky’ego. Przegląd Psychol. 36, 491–502 (1993).

Zwoliński, M. Kontrowersje dotyczące struktury czynnikowej Kwestionariusza Orientacji Życiowej (skali SOC) A. Antonovsky’ego. Przegląd Psychol. Logiczny 43, 291–298 (2000).

Gruszczyńska, E. Discriminant validity of sense of coherence vs trait anxiety in explaining emotional state in an experimental task. Psychol. Rep. 115, 228–241 (2014).

Stern, B., Socan, G., Rener-Sitar, K., Kukec, A. & Zaletel-Kragelj, L. Validation of the Slovenian version of short sense of coherence questionnaire (SOC-13) in multiple sclerosis patients. Slov. J. Public Health 58, 31–39 (2019).

Grevenstein, D. & Bluemke, M. Measurement invariance of the SOC-13 sense of coherence scale across gender and age groups. Eur. J. Psychol. Assess. 38, 61–71 (2022).

Sirkiä, C. et al. Sense of coherence, its components and depressive and anxiety symptoms in expecting women and their partners—A FinnBrain Birth Cohort Study. Sex Reprod. Healthc. 39, 100930 (2024).

Bauer, G. & Jenny, G. J. Development, implementation and dissemination of occupational health management (OHM) putting Salutogenesis into Practice. In Occupational Health Psychology (eds McIntyre, S. & Houdmondt, J.) 219–250 (Ismai, 2007).

Antonovsky, A. The salutogenic model as a theory to guide health promotion. Health Promot. Int. 11, 11–18 (1996).

Proverbio, A. M. Sex differences in the social brain and in social cognition. J. Neurosci. Res. 101, 730–738 (2023).

Gang, H., Anderson, M. H. & Summers, J. Sex differences in core self-evaluation: A meta-analytic review. Acad. Manag. Proc. 2020, 17871 (2020).

Lindmark, U., Stenström, U., Gerdin, E. W. & Hugoson, A. The distribution of “sense of coherence” among Swedish adults: A quantitative cross-sectional population study. Scand. J. Public Health 38, 1–8 (2010).

Moksnes, U. K. & Lazarewicz, M. The association between self-esteem and sense of coherence in adolescents aged 13–18 years—The role of sex and age differences. Personal. Individ. Differ. 90, 150–154 (2016).

Rivera, F., García-Moya, I., Moreno, C. & Ramos, P. Developmental contexts and sense of coherence in adolescence: A systematic review. J. Health Psychol. 18, 800–812 (2013).

Meier Magistretti, C. The sense of coherence in the life course. In The Handbook of Salutogenesis 2nd edn (eds Mittelmark, M. B. et al. et al.) (Springer, 2022).

Antonovsky, A. Health promoting factors at work: The sense of coherence. In Psychosoc Factors Work Their Relat Health (eds Kalimo, R. et al.) 153–167 (WHO, 1987).

Derbis, R. & Jasiński, A. M. Work satisfaction, psychological resiliency and sense of coherence as correlates of work engagement. Cogent Psychol. 5, 1451610 (2018).

Liukkonen, V. et al. Employment trajectories and changes in sense of coherence. Eur. J. Public Health 20, 293–298 (2010).

Goren, G., Sarid, O., Philippou, P. & Taylor, A. Sense of coherence mediates the links between job status prior to birth and postpartum depression: A structured equation modeling approach. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17, 6189 (2020).

Ślebarska, K. & Flakus, M. Career self-management of unemployed workers: The role of proactive coping in job-to-job transition. Balt. J. Manag. 16, 135–153 (2020).

World Health Organization. Noncommunicable diseases. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/noncommunicable-diseases#:~:text=Noncommunicable%20diseases%20%28NCDs%29%2C%20also%20known%20as%20chronic,diseases%2C%20are%20not%20passed%20from%20person%20to%20person (2024).

World Health Organization. Global action plan for the prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases 2013–2020. Available from: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/94384/9789241506236_eng.pdf?sequence=1 (2013).

Soper, D. S. A-priori Sample Size Calculator for Structural Equation Models [Software]. Available from: https://www.danielsoper.com/statcalc (2025).

Fornell, C. & Larcker, D. F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 18, 39 (1981).

Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M. & Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 43, 115–135 (2015).

Chen, F. F. Sensitivity of goodness of fit indexes to lack of measurement invariance. Struct. Equ. Model Multidiscip. J. 14, 464–504 (2007).

Klepp, O. M., Mastekaasa, A., Sørensen, T., Sandanger, I. & Kleiner, R. Structure analysis of Antonovsky’s sense of coherence from an epidemiological mental health survey with a brief nine-item sense of coherence scale. Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. 16, 11–22 (2007).

Gana, K. & Garnier, S. Latent structure of the sense of coherence scale in a French sample. Personal. Individ. Differ. 31, 1079–1090 (2001).

Seligman, M. E. P. Authentic Happiness: Using the New Positive Psychology to Realize Your Potential for Lasting Fulfillment (Free Press, 2002).

Kam, C. C. S. Why do regular and reversed items load on separate factors? Response difficulty vs. item extremity. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 83, 1085–1112 (2023).

Suárez-Álvarez, J. et al. Using reversed items in Likert scales: A questionable practice. Psicothema 2, 149–158 (2018).

Portoghese, I. et al. A network perspective to the measurement of sense of coherence (SOC): An exploratory graph analysis approach. Curr. Psychol. 43, 16624–16636 (2024).

Putnick, D. L. & Bornstein, M. H. Measurement invariance conventions and reporting: The state of the art and future directions for psychological research. Dev. Rev. 41, 71–90 (2016).

Kyriazos, T. A. Applied psychometrics: Sample size and sample power considerations in factor analysis (EFA, CFA) and SEM in general. Psychology 09, 2207–2230 (2018).

Kelly, M. M., Tyrka, A. R., Price, L. H. & Carpenter, L. L. Sex differences in the use of coping strategies: Predictors of anxiety and depressive symptoms. Depress. Anxiety 25, 839–846 (2008).

Komorowska-Pudło, M. The attachment style and stress coping strategies in adult men and women. Pol. Forum Psychol. https://doi.org/10.14656/PFP20160405 (2016).

Miles, J. A. & Naumann, S. E. Gender differences in intentions to seek personal counselling: The mediating role of social self-concept. Br. J. Guid. Couns. 52, 732–744 (2024).

Anderson, A. S. et al. Youth coping and symptoms of anxiety and depression: Associations with age, gender, and peer stress. Curr. Psychol. 43, 12421–12433 (2024).

Warr, P. Work, Unemployment, and Mental Health (Oxford University Press, 1987).

Soral, W. et al. Prolonged unemployment is associated with control loss and personal as well as social disengagement. J. Pers. 92, 1704–1725 (2024).

Rakoczy, J., Kostyła, M., Binder-Olibrowska, K. W. & Wrzesińska, M. A. Coping with challenges of the first months of COVID-19 pandemic among medical university community: A mixed-method study from Poland. Int. J. Occup. Med. Environ. Health 36, 365–378 (2023).

Galletta, M. et al. Sense of coherence and physical health–related quality of life in Italian chronic patients: The mediating role of the mental component. BMJ Open 9, e030001 (2019).

Zimet, G. D., Dahlem, N. W., Zimet, S. G. & Farley, G. K. The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. J. Pers. Assess. 52, 30–41 (1988).

Umberson, D. & Karas, M. J. Social relationships and health: A flashpoint for health policy. J. Health Soc. Behav. 51, S54-66 (2010).

Buszman, K. & Przybyła-Basista, H. Polska adaptacja wielowymiarowej skali spostrzeganego wsparcia społecznego. Pol. Forum Psychol. https://doi.org/10.14656/PFP20170404 (2017).

Limarutti, A., Maier, M. J. & Mir, E. Exploring loneliness and students’ sense of coherence (S-SoC) in the university setting. Curr. Psychol. 42, 9270–9281 (2023).

Adamczyk, K. & Segrin, C. Perceived social support and mental health among single vs. partnered Polish young adults. Curr. Psychol. 34, 82–96 (2015).

Li, Q. et al. Sense of coherence mediates perceived social support and depressive and anxiety symptoms in cervical cancer patients: A cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry 23, 312 (2023).

Silber, H., Roßmann, J. & Gummer, T. The issue of noncompliance in attention check questions: False positives in instructed response items. Field Methods 34, 346–360 (2022).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr. Avishai Antonovsky for agreeing to validate the SOC-13 scale on a Polish sample and for his kind words about the study idea.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.J. wrote original draft and played a lead role in conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, methodology, project administration, and writing-review and editing. R.D. played a lead role in funding acquisition, and supporting role in supervision, data curation, methodology, writing-review and editing. J.R. played a supporting role in conceptualization, methodology, writing-review and editing. M.W. played a lead role in funding acquisition, and supporting role in supervision, conceptualization, methodology, writing-review and editing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study design was reviewed and approved by the University of Opole Research Ethics Committee (Decision No. 10/2024). All participants were over 18 years of age. All participants gave written consent to participate in this anonymous, voluntary study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jasiński, A.M., Derbis, R., Rakoczy, J. et al. The sense of coherence scale and relationships between sense of coherence, sociodemographic variables and chronic disease. Sci Rep 15, 18289 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-02998-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-02998-6