Abstract

Ultra-wideband (UWB) positioning in coal mines faces severe accuracy degradation due to non-line-of-sight (NLOS) errors. To address this, we propose the Chan Based on Reference Coordinate (CBORF) algorithm, which integrates dynamic error compensation and adaptive parameter tuning to achieve centimeter-level accuracy with minimal computational overhead. Unlike existing methods (e.g., Chan-Taylor, Kalman-Chan), CBORF introduces a reference label-guided correction mechanism, statistically analyzing deviations between estimated and actual reference coordinates to compensate for systemic offset and dispersion errors. Simulations under exponential-distributed NLOS noise demonstrate CBORF’s superiority: RMSE of 0.026 m (stationary) and 0.075 m (moving targets), outperforming Chan (0.48 m) and Taylor (0.38 m) by 1–2 orders of magnitude. It also maintains the efficiency of the Chan algorithm and avoids iterative filtering (e.g., particle resampling in PF-Chan), which is a significant advantage over other algorithms. This work advances the state-of-the-art by resolving the long-standing trade-off between accuracy and computational complexity in NLOS-prone environments. Unlike filtering-dependent approaches (e.g., PF-Chan, Kalman-Chan), CBORF eliminates the need for iterative particle resampling or linear-Gaussian assumptions, ensuring reliability in high-noise, nonlinear conditions. Its parameter-driven design further enhances adaptability across diverse underground layouts, offering a practical and scalable solution for real-time personnel tracking in coal mines.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Coal mining operations mainly rely on underground activities, especially operations. Ensuring the safety of underground workers is a critical issue for safe coal mine production1. Ultra-wideband (UWB) positioning technology has become essential for underground coal mine safety systems, providing centimeter-level accuracy and robustness against multipath interference2. However, non-line-of-sight (NLOS) errors in complex underground environments remain a significant challenge, reducing positioning reliability and limiting practical deployment.

UWB positioning methods are mainly categorized into two types: Time of Arrival (TOA) and Time Difference of Arrival (TDOA) based positioning. Unlike the TOA method, which necessitates system-wide clock synchronization, the TDOA method only requires synchronization between base stations. This simplifies implementation and enhances its popularity3,4,5. Chan algorithm, while computationally efficient, falters under non-Gaussian NLOS noise6, whereas the Taylor algorithm achieves higher accuracy but suffers from convergence instability, high dependence on initial values and high computational demands7,8,9. Hybrid approaches (e.g., Chan-Taylor, Kalman-Chan, PF-Chan) aim to overcome these limitations but introduce new challenges, such as iterative filtering complexity, sensitivity to initial values, and particle degeneracy in PF-based methods, all of which hinder real-time performance and scalability10,11,12,13. While these methods partially address NLOS challenges, they fail to resolve the core trade-off: high accuracy requires significant computational overhead, while low-complexity methods lack robustness.

With the rise of 5G and IoT-driven smart mining, UWB positioning is poised for integration with high-precision time synchronization (5G) and AI-driven error mitigation (e.g., deep learning for NLOS identification)14,15,16. Meanwhile, emerging 5G-UWB fusion frameworks leverage 5G’s high-precision time synchronization to enhance TDOA measurements. While promising and indeed providing localization accuracy, these approaches necessitate costly infrastructure upgrades and struggle with dynamic NLOS scenarios15,17. These advancements often require substantial hardware upgrades or data-intensive training, limiting feasibility in resource-constrained mines. Take deep learning-enhanced methods as an example, they demand extensive labeled datasets and high-power hardware, limiting feasibility in resource-constrained mines14,18,19,20.

To address these gaps, we propose the Chan Based on Reference Coordinate (CBORF) algorithm, which achieves centimeter-level accuracy in NLOS environments while retaining the computational simplicity of the original Chan method. By deploying a reference node with known coordinates, CBORF quantifies systemic NLOS errors (offset and dispersion) and compensates target positions in real time, eliminating reliance on iterative filtering or particle resampling. Tunable coefficients dynamically adjust error correction intensity based on environmental noise, avoiding overfitting issues seen in fixed-parameter hybrids. Unlike data-intensive deep learning methods, CBORF operates as a lightweight, hardware-agnostic solution, aligning with 5G-driven trends in low-latency edge computing for smart mines.

Chan based on reference coordinate

TDOA algorithm positioning principle

The TDOA positioning algorithm relies on a key assumption: clock synchronization across all base stations. In this scenario, the target transmits UWB pulse signals to different base stations. The system records both the time of signal arrival at each base station and the time when the label transmits the signal. The target’s location is then determined by calculating the time differences between signals received at different base stations.

First, identify the reference base station. The distance difference \(\:\varDelta\:r\) between the target and the reference base station is calculated based on the time difference between signal reception at the reference and other base stations, and the speed of electromagnetic wave propagation (assuming air conditions and approximating the speed of light as c), as

Next, a coordinate system is established, and a hyperbola is defined with the two base stations as its foci. Based on the properties of the hyperbola, the target’s position lies on one of its branches. The following equation relates the coordinates of the base stations to the time difference between the received signals:

However, these equations alone cannot determine which branch of the hyperbola the target is located. Therefore, additional base stations are needed to generate more equations, allowing for the precise determination of the target’s location, as shown in Fig. 1.

The following system of equations relates the coordinates of each base station to the time differences between the received signals:

Here, \(\:\varDelta\:{r}_{n,1}\) represents the distance between the \(\:n\)th station and the 1st station. The target’s coordinates can then be solved.

Principles of Chan algorithm

The Chan algorithm solves a system of non-recursive hyperbolic equations to obtain an analytical solution21. This section discusses the localization method using more than three base stations6.

The distance between the \(\:i\)th base station and the target can be expressed as:

The distance difference and sum between the target and the reference base station (with the first base station as the reference by default) and the \(\:i\)th base station are calculated and multiplied to obtain:

To simplify the calculation, let \(\:{k}_{i}^{2}={x}_{i}^{2}+{y}_{i}^{2}\), and Eq. (5) reduces to

where \(\:{r}_{i}^{2}-{r}_{1}^{2}\) can be rewritten as

By combining Eq. (7) with Eq. (6), we get

Converting this into matrix form yields:

This matrix equation can be expressed as

The solution of the equation can be viewed as the sum of \(\:{r}_{1}\) times the solution of \(\:AX=C\) plus the solution of \(\:AX=D\). The least squares method is used to solve for \(\:AX=C\) and \(\:AX=D\), respectively, yields a 3 × 1 matrix \(\:N\) and a 3 × 1 matrix \(\:M\). Applying Cramer’s rule, we obtain

where \(\:{n}_{i}\) represents each component of matrix \(\:N\) and \(\:{m}_{i}\) represents each component of matrix \(\:M\). According to Eq. (4), we can get

Among them,

The final solution is given by

If \(\:\sqrt{{P}^{2}-QR}>0\), then the system of equations has a solution. However, the solution \(\:{r}_{1}\) has two possible values, which introduces the possibility of a pseudo-solution. Therefore, selecting the true solution becomes necessary.

To select the appropriate solution, we denote the two potential solutions as \(\:X1\) and \(\:X2\) in this paper. The more accurate solution is determined by comparing the difference between the actual distance \(\:{d}_{actual}\) and the expected distance \(\:{d}_{expected}\) from each solution to all base stations. The actual distance \(\:{d}_{actual,i}\) between the estimated label coordinate estimate \(\:{{(x}_{X,}{y}_{X},z}_{X})\) and the \(\:i\)th base station is given by the following equation:

Where, \(\:i=\text{2,3},\dots\:,n\), \(\:n\) is the number of base stations. The expected distance \(\:{d}_{expected,i}\) between the estimated label coordinate estimate \(\:{{(x}_{X,}{y}_{X},z}_{X})\) and the \(\:i\)th base station is calculated using the TDOA algorithm. The expression for this distance is given by:

This formula indicates that the expected distance between the label and the base station is the sum of the distance between the estimated coordinates and the reference base station, plus the difference calculated theoretically. The difference between \(\:{d}_{actual,i}\) and \(\:{d}_{expected,i}\) is summed, and the absolute value is taken to obtain:

The two solutions are compared based on their index values, and the solution with the smaller index is selected as the true solution.

The Chan algorithm offers advantages such as computational simplicity, fast response times, and high positioning accuracy when the observation error follows a Gaussian distribution with zero mean. However, in real-world measurements, the observation error often deviates from a zero-mean Gaussian distribution, causing the performance of the Chan algorithm to degrade, particularly in NLOS environments.

Principle of Chan based on reference coordinates

In this paper, the error in the Chan algorithm is categorized into two types: offset error, which represents the deviation of the mean positioning data from the true position, and discrete error, which reflects the variation in positioning data points. This paper proposes a Chan algorithm based on reference coordinates, which determines a compensation strategy by analyzing the error between the reference coordinates and real coordinates to correct the positioning results of the target labels. As a case study, this paper uses two-dimensional data, where the target label coordinates are denoted as (\(\:x,y\)) and the reference label coordinates as (\(\:{x}_{0},{y}_{0}\)), and describes the positioning process for both stationary and moving targets.

Positioning of stationary targets

-

1.

Acquisition of raw data and valid data.

The Chan algorithm is first applied to localize both the target and reference labels, producing localization data set \(\:{X}_{o}\) for the target and \(\:{X}_{r}\) for the reference. The data in \(\:{X}_{o}\) exhibits large localization errors and may contain extreme values, which must be preprocessed for removal.

First, compute the mean value of \(\:{X}_{o}\), denoted as \(\:\stackrel{-}{{X}_{o}}\). Then, calculate the geometric distance from each localization point to \(\:\stackrel{-}{{X}_{o}}\) to form the error set \(\:{e}_{o}\). Next, compute the mean \(\:\stackrel{-}{{e}_{o}}\) and standard deviation \(\:{\sigma\:}_{{e}_{o}}\) of \(\:{e}_{o}\) to determine the error threshold \(\:{e}_{t}\) as

$$\:\begin{array}{c}{e}_{t}=\:\stackrel{-}{{e}_{o}}+{k}_{e}*{\sigma\:}_{{e}_{o}}\end{array}$$(18)The error threshold coefficient \(\:{k}_{e}\) is an adjustable parameter modified based on specific requirements. Localization points with errors less than \(\:{e}_{t}\) are filtered to form the valid data set \(\:X\) for further processing.

-

2.

Determination of the offset compensation value \(\:{c}_{offset}\)

The offset compensation value \(\:{c}_{offset}\) adjusts the positioning data to align more closely with the true coordinates of the target label, thereby reducing the offset. \(\:{c}_{offset}\) consists of two components: the offset compensation factor \(\:{f}_{offset}\) and the offset compensation coefficient \(\:{k}_{offset}\).

\(\:{f}_{offset}\) is determined by the mean value of the difference between the measured positioning data of the reference label and its actual coordinate, as follows:

$$\:\begin{array}{c}{f}_{offset}\left\{\begin{array}{c}{f}_{offset,x}=\frac{\sum\:_{i=1}^{n}{x}_{r,i}}{n}-{x}_{0}\\\:{f}_{offset,y}=\frac{\sum\:_{i=1}^{n}{y}_{r,i}}{n}-{y}_{0}\end{array}\right.\end{array}$$(19)Here, \(\:{x}_{r,i}\) and \(\:{y}_{r,i}\) represent the horizontal and vertical coordinates of the ith element of \(\:{X}_{r}\) respectively, and \(\:n\) is the number of elements of \(\:{X}_{r}\). From this, \(\:{f}_{offset,x}\) in the horizontal direction and \(\:{f}_{offset,y}\) in the vertical direction can be obtained.

\(\:{k}_{offset}\) is also divided into two parts: \(\:{k}_{offset,x}\) in the horizontal direction and \(\:{k}_{offset,y}\) in the vertical direction. These values can be adjusted based on environmental factors affecting the positioning. Using \(\:{f}_{offset}\) and \(\:{k}_{offset}\), \(\:{c}_{offset}\) is obtained as:

$$\:\begin{array}{c}{c}_{offset}={k}_{offset}*{f}_{offset}\:\end{array}$$(20) -

3.

Determination of the discrete compensation value \(\:{c}_{discrete}\)

The discrete compensation value \(\:{c}_{discrete}\) aims to centralize the localization data and reduce discretization. \(\:{c}_{discrete}\) is likewise composed of a discrete compensation factor \(\:{f}_{discrete}\) and a discrete compensation coefficient \(\:{k}_{dicrete}\).

The first is determining \(\:{f}_{discrete}\). The absolute difference between each element in \(\:{X}_{r}\) and the actual coordinates of the reference label is calculated and averaged to obtain

$$\:\begin{array}{c}{e}_{discrete}=\frac{\sum\:_{i=1}^{n}\left|{X}_{r,i}-({x}_{0},{y}_{0})\right|}{n}\end{array}$$(21)Here, \(\:n\) represents the number of elements of \(\:{X}_{r}\), \(\:{X}_{r,i}\) is the \(\:i\)th element of \(\:{X}_{r}\). Next, the average distance \(\:{d}_{m}\) from the reference label coordinate to each base station is calculated as

$$\:\begin{array}{c}{d}_{m}=\:\frac{\sum\:_{i=1}^{m}\sqrt{{\left({x}_{s,i}-{x}_{0}\right)}^{2}+{\left({y}_{s,i}-{y}_{0}\right)}^{2}}}{m}\end{array}$$(22)where \(\:m\) is the number of base stations. \(\:{x}_{s,i}\) and \(\:{y}_{s,i}\) represent the horizontal and vertical coordinates of the \(\:i\)th base station, respectively. The normalized \(\:{f}_{discrete}\) is obtained by dividing \(\:{e}_{discrete}\) and \(\:{d}_{m}\) as follows:

$$\:\begin{array}{c}{f}_{discrete}=\:\frac{{e}_{discrete}}{{d}_{m}}\end{array}$$(23)Using only \(\:{f}_{discrete}\) for compensation cause further discretization of data near the center, while data farther from the center may not be effectively compensated, reducing the overall compensation accuracy. Therefore, the compensation process must be controlled by the discrete \(\:{k}_{dicrete}\). A distinct \(\:{k}_{dicrete,i}\) is calculated for each data point as

$$\:\begin{array}{c}{k}_{dicrete,i}={X}_{i}-\stackrel{-}{X}\end{array}$$(24)Here, \(\:i=\text{1,2},\cdots\:,n\), where \(\:n\) is the number of elements of \(\:X\), \(\:{X}_{i}\) is the \(\:i\)th element of \(\:X\), \(\:\stackrel{-}{X}\) is the mean value of all the elements in \(\:X\). \(\:{k}_{dicrete,i}\) is a two-dimensional vector with horizontal \(\:{k}_{dicrete,x,i}\) and vertical \(\:{k}_{dicrete,y,i}\). This enables the automatic adjustment of \(\:{k}_{dicrete,i}\) for each data point.

\(\:{c}_{discrete}\) is calculated using the \(\:{f}_{discrete}\) and the \(\:{k}_{dicrete}\), as follows:

$$\:\begin{array}{c}{c}_{discrete}=\:{k}_{dicrete}*{f}_{discrete}\end{array}$$(25) -

4.

Compensation and smoothing of valid data.

After obtaining \(\:{c}_{offset}\) and \(\:{c}_{discrete}\), \(\:X\) can be compensated to obtain the compensated data set \(\:{X}_{comp}\). The compensation is performed as follows:

$$\:\begin{array}{c}{X}_{comp,x,i}={X}_{x,i}-{k}_{offset,x}*{f}_{offset,x}-\:{k}_{dicrete,x,i}*{f}_{discrete}\end{array}$$(26)$$\:\begin{array}{c}{X}_{comp,y,i}={X}_{y,i}-{k}_{offset,y}*{f}_{offset,y}-\:{k}_{dicrete,y,i}*{f}_{discrete}\end{array}$$(27)After compensation, the data in \(\:{X}_{comp}\) can be further smoothed. In this paper, we apply the moving average method to process the data as follows22:

$$\:\begin{array}{c}{X}_{smooth,i}=\frac{1}{w}\sum\:_{j=i}^{i+w-1}{X}_{comp,j}\end{array}$$(28)Here, \(\:{X}_{smooth,i}\) represents the \(\:i\)th element of \(\:{X}_{smooth}\), \(\:{X}_{comp,j}\) represents the \(\:j\)th element of \(\:{X}_{comp}\) and \(\:w\) represents the window size, which can be adjusted based on specific requirements.

As shown above, when applying this algorithm to localize stationary targets, the key parameters to set are the error threshold coefficient \(\:{k}_{e}\), the offset compensation coefficient \(\:{k}_{offset}\), and the window size \(\:w\). Selecting appropriate values for these parameters is critical for enhancing localization accuracy. The following is a pseudo-code description of stationary target localization.

Positioning of moving targets

In contrast to stationary targets, the trajectories of moving targets are complex and irregular, which complicates their processing. To simplify processing, we divide the total distance traveled by the target into segments, assuming that the movement direction remains constant within each segment. The processes for acquiring raw and valid data, as well as for compensating and smoothing the valid data, follow the same procedure as for stationary targets and are not repeated here. This section primarily focuses on the determination of compensation parameters and methods.

-

1.

Fitting of motion trajectories.

The purpose of fitting the motion trajectory is to obtain an initial trajectory, which facilitates data processing. This paper uses polynomial fitting to model the target’s motion trajectory, with common methods including least squares, Lagrange interpolation, and Newton interpolation23,24,25,26. Given the specific conditions of the downhole environment, the least squares method is chosen for polynomial fitting. This choice is based on four considerations: first, the large amount of localization data, which may cause Lagrange interpolation to be affected by the Runge phenomenon24; second, significant noise in the NLOS environment, which makes the Newtonian interpolation method less effective26; third, the distance is segmented, and the target’s movement direction remains fixed within each segment, simplifying the data distribution; and fourth, the high computational efficiency of the least squares method improves response speed.

By fitting polynomials separately for the horizontal and vertical directions, the adjusted coordinates, \(\:{x}_{fit}\) and \(\:{y}_{fit}\), can be obtained. However, if the target moves only in the horizontal direction, the vertical coordinate is fixed and unnecessary to fit, as fitting could lead to incorrect results due to noise, and vice versa. Therefore, under certain conditions, fitting only one direction is sufficient, which also improves computational speed.

In this paper, the fitting direction is determined by analyzing the ratio of the standard deviations of the horizontal and vertical data. The sample variances for the horizontal and vertical directions are calculated as follows:

$$\:\begin{array}{c}Var\left(x\right)=\frac{1}{n-1}\sum\:_{i=1}^{n}\left({x}_{i}-\stackrel{-}{x}\right)\end{array}$$(29)$$\:\begin{array}{c}\:Var\left(y\right)=\frac{1}{n-1}\sum\:_{i=1}^{n}\left({y}_{i}-\stackrel{-}{y}\right)\end{array}$$(30)Here, \(\:{(x}_{i},{y}_{i})\) is each element in \(\:X\), and \(\:\stackrel{-}{x}\) and \(\:\stackrel{-}{y}\) represent the mean values of the horizontal and vertical coordinates, respectively. Define a discriminant \(\:R\) for the motion direction, if \(\:\frac{\sqrt{Var\left(x\right)}}{\sqrt{Var\left(y\right)}}>R\), the target’s motion is considered mainly horizontal, and fitting should be performed in the vertical direction to obtain \(\:{y}_{fit}\); if \(\:\frac{\sqrt{Var\left(y\right)}}{\sqrt{Var\left(x\right)}}>R\), the motion is considered mainly vertical, and fitting should be performed in the horizontal direction to obtain \(\:{x}_{fit}\). If neither of the above conditions is satisfied, the target is considered to be moving diagonally, and both horizontal and vertical directions are fitted to obtain both \(\:{x}_{fit}\) and \(\:{y}_{fit}\).

-

2.

Determination of compensation parameters.

The offset compensation factor \(\:{f}_{offset}\), the offset compensation coefficient \(\:{k}_{offset}\) and the discrete compensation factor \(\:{f}_{discrete}\) are determined in the same manner as for stationary targets, and will not be repeated here. The error compensation is discussed in three cases based on the direction of motion.

-

1.

Target moves only in the horizontal direction.

For targets moving only in the horizontal direction, the theoretical vertical coordinate \(\:{y}_{fit}\) is obtained by fitting the horizontal coordinates. The vertical coordinate of each data point is then compared with \(\:{y}_{fit}\) to compute the discrete compensation coefficient.

$$\:\begin{array}{c}{k}_{dicrete,y,i}={y}_{i}-{y}_{fit}\end{array}$$(31)Here \(\:i=\text{1,2},\cdots\:,n\), \(\:n\) is the number of elements of \(\:X\), and \(\:{y}_{i}\) is the value of the vertical coordinate of the \(\:i\)th element. Since the target moves only horizontally, offset compensation is applied only to the horizontal direction.

-

2.

Target moves only in the vertical direction.

For targets moving only in the vertical direction, the theoretical horizontal coordinate \(\:{x}_{fit}\) is obtained by fitting the vertical coordinates. The horizontal coordinate of each data point is then compared with \(\:{x}_{fit}\) to compute the discrete compensation coefficient.t

$$\:\begin{array}{c}{k}_{dicrete,x,i}={x}_{i}-{x}_{fit}\end{array}$$(32)Here \(\:i=\text{1,2},\cdots\:,n\), \(\:n\) is the number of elements of \(\:X\), and \(\:{x}_{i}\) is the value of the horizontal coordinate of the \(\:i\)th element. Since the target moves only vertically, offset compensation is applied only to the vertical direction.

-

3.

Target moves obliquely.

When the target moves obliquely, it moves both horizontally and vertically. In this case, both the horizontal and vertical directions must be fitted simultaneously to obtain \(\:{x}_{fit}\) and \(\:{y}_{fit}\) resulting in the fitted set \(\:{X}_{fit}\). The discrete compensation coefficient is then determined as

$$\:\begin{array}{c}{k}_{dicrete,i}={X}_{i}-{X}_{fit}\end{array}$$(33)Here \(\:i=\text{1,2},\cdots\:,n\) \(\:n\) is the number of elements of \(\:X\) and \(\:{X}_{i}\) is the \(\:i\)th element.

From the above, it is clear that in addition to the error threshold coefficient \(\:{k}_{e}\), the offset compensation coefficient \(\:{k}_{offset}\), and the window size \(\:w\), the following parameters must also be set: the discriminant factor \(\:R\), then a suitable distance segmentation strategy. The following is a pseudo-code description of moving target localization.

Reference coordinate setting and theoretical accuracy

2.3.1 and 2.3.2 highlight that reference labels are central to the CBORF algorithm and play a critical role in compensating both offset and discretization errors. The following principles should guide the setting of reference labels.

First, the coordinates of the reference labels must be precise and minimally affected to ensure accuracy. The core of the CBORF algorithm involves statistically determining the systematic error in the NLOS environment and deriving compensation parameters from the deviation between the true coordinates and the measured coordinates of the reference labels. If the reference labels’ position is uncertain, it will reduce the accuracy of the compensation parameters and introduce additional errors, further decreasing positioning accuracy.

Second, the spatial correlation between the reference and target labels determines the generalization capability of the compensation parameters. If the reference label is placed in a region different from the target, its error distribution will differ from that of the target label, causing the compensation parameters to lose their reference value and degrading the algorithm’s performance.

After verifying that the reference label settings meet the above requirements, we proceed to analyze the theoretical accuracy of the CBORF algorithm. We define the error resulting from the algorithm’s localization as

Here, \(\:\varDelta\:{X}_{smooth}\) represents the localization error of the algorithm, \(\:\varDelta\:{X}_{t}\) represents the localization error of the Chan algorithm. As mentioned above, we decompose \(\:\varDelta\:{X}_{t}\) into two components: \(\:\varDelta\:{X}_{offset}\) and \(\:\varDelta\:{X}_{discrete}\). We assume that \(\:\varDelta\:{X}_{offset}\) is perfectly correlated with \(\:{f}_{offset}\) and \(\:\varDelta\:{X}_{discrete}\) is perfectly correlated with \(\:{f}_{discrete}\). Thus, there is a quantitative relationship of \(\:\varDelta\:{k}_{1}\:\)between \(\:\varDelta\:{X}_{offset}\) and of \(\:\varDelta\:{k}_{2}\) between \(\:\varDelta\:{X}_{discrete}\) and \(\:{f}_{discrete}\), respectively, Eq. (34) can then be simplified to

Furthermore, we assume that \(\:{k}_{offset}\) and \(\:{f}_{discrete}\:\)are independent. The variance is then given by:

where \(\:{{\sigma\:}_{offset}}^{2}\) represents the variance of \(\:{f}_{offset}\) and \(\:{{\sigma\:}_{discrete}}^{2}\) represents the variance of \(\:{f}_{discrete}\). It is clear that when \(\:(1-\varDelta\:{k}_{1}{k}_{offset)}=0\) and \(\:\left(1-\varDelta\:{k}_{2}{k}_{dicrete}\right)=0\), \(\:{{\sigma\:}_{smooth}}^{2}\) is minimized to 0.

In an ideal Gaussian noise environment, the localization accuracy of the CBORF algorithm is constrained by the geometric dilution accuracy of the reference node. The relationship between the minimum GDOP value and the number of base stations in a two-dimensional environment is given by27:

where \(\:n\) represents the number of base stations. Since GDOP is defined as the geometric layout of base stations in relation to localization error, the measurement error caused by TDOA errors is given by:

where \(\:c\) represents the speed of light and \(\:{\sigma\:}_{TDOA}\) represents the TDOA measurement error. Assuming six base stations and a \(\:{\sigma\:}_{TDOA}\) value of 0.1ns, the minimum \(\:\varDelta\:TDOA\) is 0.024 m. This represents the theoretical localization accuracy limit for the current scenario.

However, it is important to note that all the above conditions represent ideal cases, which may not hold in practice. For instance, \(\:\varDelta\:{X}_{offset}\) is not perfectly correlated with \(\:{f}_{offset}\) and \(\:\varDelta\:{X}_{discrete}\) is not perfectly correlated with \(\:{f}_{discrete}\), causing \(\:{{\sigma\:}_{smooth}}^{2}\) to be non-negligible. Furthermore, the value of \(\:{\sigma\:}_{TDOA}\) is not fixed, and the value of \(\:GDOP\) may be affected by the clock offset. Therefore, we must adjust the algorithm parameters based on the actual conditions and establish appropriate reference labels to maximize its performance.

Simulation study

Initial algorithm selection and preliminary study of algorithm performance

This section presents simulation experiments to evaluate the performance of algorithms in NLOS environments. It focuses on assessing the Chan algorithm’s effectiveness as an initial approach and conducting a preliminary analysis of the performance of various algorithms. The algorithms analyzed include the Chan, Taylor, Chan-Taylor, Kalman-Chan, and PF-Chan algorithms.

The simulation assumes a regular hexagonal base station layout, with six stations positioned at the hexagon’s vertices and one at its center. The target lies within the hexagon. The coordinates of the base stations are\(\:\left(\text{0,0}\right)\), \(\:\left(\text{2.5,2.5}\sqrt{3}\right)\), \(\:\left(\text{7.5,2.5}\sqrt{3}\right)\), \(\:\left(\text{10,2.5}\sqrt{3}\right)\), \(\:(7.5,-2.5\sqrt{3})\), \(\:(2.5,-2.5\sqrt{3})\), \(\:\left(\text{5,0}\right)\), and the label coordinate is \(\:\left(\text{1.5,1}\right)\). All coordinates are given in meters, as depicted in Fig. 2.

In the NLOS environment, the noise may obey the following distributions: uniform, delta, or exponential distribution28. To simulate the complex conditions found in mining environments, exponential distribution noise (EDRN) is incorporated into the simulation. The mathematical expression for EDRN is given as:

Here \(\:{\tau\:}_{NLOS}\) represents the root-mean-square time-delay extension, which is significantly influenced by the communication environment. In complex communication environments, \(\:{\tau\:}_{NLOS}\) can be extended as

where\(\:\:d\) is the distance between two localized nodes, \(\:{T}_{1}\) is the median value of \(\:{\tau\:}_{NLOS}\) when d=1 km, and takes a fixed value. The parameter \(\:\epsilon\:\) is a constant within the range \(\:\left[\text{0.5,1}\right]\), and \(\:\xi\:\) is a random variable following a lognormal distribution.

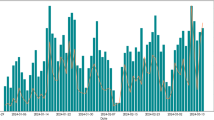

In this section, \(\:{T}_{1}\) is set to be 0.5s, \(\:\epsilon\:\) is randomly generated within the range \(\:\left[\text{0.5,1}\right]\), and \(\:\xi\:\) follows an exponential normal distribution with a mean of 0 and a variance of 0.5 m. A total of 2000 localization simulation experiments were conducted. The algorithms analyzed include the Chan, Taylor, Chan-Taylor, Kalman-Chan, and PF-Chan algorithms. The results are presented in Figs. 3 and 4.

Simulation results show that the PF-Chan algorithm fails to perform localization in NLOS environments. The localization error in Kalman-Chan is significant, suggesting that it cannot complete localization successfully. Kalman-Chan requires both the system dynamic model and the observation model to be linear, with noise following a Gaussian distribution. However, its performance degrades significantly when noise deviates from a Gaussian distribution, failing when the noise effect is too large. In PF-Chan, the number of effective particles decreases dramatically after resampling due to the Chan error, which causes most particle weights to converge to zero, leaving only a small number of particles with significant weights. Figuratively speaking, the weight of a particle is determined by its degree of aggregation. A more aggregated particle has a higher weight, and vice versa. In the NLOS environment, the large error in the Chan algorithm leads to particles that do not exhibit significant aggregation properties. As a result, most particles are underweighted, leading to weight spillover. Only a small number are resampled, causing a loss of particle diversity and failure to represent the true state. Once the particle swarm aggregates in an incorrect region, the particle spreading range in the subsequent prediction step is constrained.

Figure 4 shows that for algorithms that successfully localize, the performance difference in NLOS environments is minimal, with no significant advantage over the Chan algorithm. In summary, considering algorithm performance, implementation simplicity, and computational cost, the Chan algorithm is selected as the primary method for localization. Its low computational cost, ease of implementation, and faster execution speed in NLOS environments enhance response efficiency, as demonstrated in Fig. 5.

Figure 5 shows the time cost of each algorithm. The Chan and CBORF algorithms demonstrate significantly superior performance compared to both the Taylor and Chan-Taylor algorithms. While significantly improving localization accuracy, the CBORF algorithm does not require a notable increase in time cost compared to the Chan algorithm, while maintaining high computational efficiency.

Alter the noise environment to evaluate the performance of the CBORF algorithm under various noise conditions, and perform a preliminary comparison of all algorithms. Introduce noise following a uniform distribution (UDN) and mixed noise (combining both EDRN and UDN), respectively. The mathematical expression for EDRN is as follows:

Where the value of \(\:{\tau\:}_{NLOS}\) remains as shown in Eq. (40). The error threshold coefficient is \(\:{k}_{e}=0.5\), the offset compensation coefficient \(\:{k}_{offset}\) is \(\:\left\{\begin{array}{l}{k}_{offset,x}=2\\\:{k}_{offset,y}=\left\{\begin{array}{l}25,\stackrel{-}{y}>0\\\:-25,\stackrel{-}{y}<0\end{array}\right.\end{array}\right.\), and the window size is \(\:w=8\). where \(\:\stackrel{-}{y}\) represents the mean vertical component of valid data, keeping the above simulation conditions unchanged. The results are shown in Table 1.

Chan-Valid represents the localization results derived from the Chan algorithm after filtering valid data. As shown in Table 1, the CBORF algorithm demonstrates a clear advantage over other algorithms, regardless of the environment. The noise following an exponential distribution has the most significant impact on positioning accuracy. To simulate the real downhole environment, the simulations in Sect. 3.2 and 3.3 utilize noise following the EDRN model.

Study for localizing stationary targets

This section simulates the CBORF, Chan, Taylor, and Chan-Taylor algorithms in a downhole environment to evaluate their localization performance for stationary targets. The Kalman-Chan and PF-Chan algorithms failed to localize successfully in previous simulations, and are therefore excluded from the following comparison. The base station coordinates are \(\:\left(\text{0,0}\right)\), \(\:\left(\text{0,10}\right)\), \(\:\left(\text{5,10}\right)\), \(\:\left(\text{5,0}\right)\), \(\:(5,-10)\),\(\:\:(0,-10)\), while the target label is located at \(\:\left(\text{1.5,3}\right)\) in meters. To account for real-world complexities where reference coordinates may vary due to operational movement, the reference point is set at the same coordinates as the base station (0,0) to eliminate this effect, as shown in Fig. 6.

The noise conditions in the simulated downhole environment are consistent with those of the NLOS environment described in Sect. 3.1. The CBORF algorithm is also parameterized in the same way as in Sect. 3.1. A total of 2000 localization simulations were performed, with results shown in Figs. 7 and 8.

Figures 7 and 8 demonstrate that the CBORF algorithm produces tightly clustered and uniformly distributed localization results around the target. Both the offset and discretization error are smaller than those of other algorithms.

Table 2 shows that the RMSE error of the CBORF algorithm is significantly reduced, with all indices greatly improved. This indicates that in most scenarios, the localization results of CBORF are closer to the real value, with a low standard deviation, reflecting good stability and minimal sensitivity to environmental noise. Additionally, 90% of the localization errors are within 0.31 m, demonstrating that CBORF maintains high reliability even in adverse scenarios.

To evaluate the impact of target position on localization error, the target label coordinates were varied, and the RMSE was calculated. The results are presented in Table 3.

Table 3 shows that the CBORF algorithm achieves positioning accuracy within 0.1 m. However, errors at points \(\:\left(\text{1.5,0}\right)\), \(\:\left(\text{2.5,0}\right)\) and \(\:\left(\text{3.5,0}\right)\) are relatively higher. This discrepancy arises because the Chan algorithm’s low original localization error causes the applied parameter settings to overcompensate, thereby reducing the effectiveness of the CBORF algorithm’s compensation mechanism. Simulation results confirm that the CBORF algorithm achieves accurate localization with the appropriate parameter settings. However, suboptimal settings can lead to under-compensation or overcompensation, which hinders accuracy improvements and may increase localization error. This will be further discussed in Sect. 3.4.

Study for localizing moving targets

In this section, simulations use the same base station layout and environmental conditions as in Sect. 3.2 to evaluate the localization performance of the two algorithms for moving targets. The target label starts at \(\:\left(\text{2,5}\right)\) and follows a trajectory divided into four journeys. Figure 9 illustrates the base station layout, reference label position, and target label motion trajectory.

For each journey, 500 localizations were performed. The error threshold coefficient is \(\:{k}_{e}=1.5\), the offset compensation coefficient \(\:{k}_{offset}\) is \(\:\left\{\begin{array}{l}{k}_{offset,x}=1\\\:{k}_{offset,y}=\left\{\begin{array}{l}20,\stackrel{-}{y}>0\\\:-20,\stackrel{-}{y}<0\end{array}\right.\end{array}\right.\). Here \(\:\stackrel{-}{y}\) represents the mean vertical component of valid data. The window size was \(\:w=6\), the discriminant factor is \(\:R=1.5\). The localization results are shown below.

From Figs. 10, 11, 12, 13, 14 and 15, it is evident that the CBORF algorithm outperforms other algorithms in localization accuracy. The majority of the localization data has an error within 0.5 m, whereas most of the valid data from the Chan algorithm has an error within 1 m. Additionally, the Taylor and Chan-Taylor algorithms have the most localization errors within 1.5 m. As shown in Table 4, the CBORF algorithm demonstrates a significant advantage across all performance indicators, with an RMSE of only 0.055 m, achieving centimeter-level accuracy. This represents an improvement of 1–2 orders of magnitude compared to other algorithms, and the standard deviation of 0.141 m is the lowest in the table, with a dispersion 71% lower than that of the Chan-Valid. Additionally, the 90% error of 0.35 m reflects the algorithm’s reliability in complex environments.

In practical scenarios, varying sampling frequencies and target movement speeds necessitate adjustments to the number of localizations per journey. To investigate this effect, the number of localizations was varied between 100 and 1000, in increments of 10, while other conditions were kept constant. The resulting RMSE changes for the CBORF algorithms are shown in Fig. 16.

The results show that the RMSE of the CBORF algorithm tends to decrease as the number of localizations increases. The RMSE stabilizes within 0.1 m when the number of localizations per group exceeds 400. Considering the randomness of the noise, it can be assumed that the algorithm’s performance has stabilized, and further increases in the number of localizations per group have little effect on performance.

Parameter sensitivity analysis

This section discusses the impact of each parameter on the CBORF algorithm’s performance. First, we analyze the impact of each parameter on the algorithm’s performance when the target is stationary, based on the simulation conditions from Sect. 3.2. The result is shown in Fig. 17.

As shown in Fig. 17, the effect of \(\:{k}_{e}\) and error is nearly linear, with the localization error of the CBORF algorithm increasing as \(\:{k}_{e}\) increases. This is because \(\:{k}_{e}\) is used to filter valid data in the Chan algorithm. If \(\:{k}_{e}\) is too large, the validity of the obtained data will be reduced, leading to reduced localization accuracy. However, for stationary target localization, data validity is crucial. Therefore, selecting the smallest possible \(\:{k}_{e}\) can enhance localization accuracy. As seen in Fig. 7 and in comparison of Figs. 11 and 12, as well as data in the tables, selecting the appropriate \(\:{k}_{e}\) effectively filters valid data.

\(\:{k}_{offset,x}\:\) and \(\:{k}_{offset,y}\) do not have a simple linear relationship with RMSE. As mentioned in Sect. 3.2, if \(\:{k}_{offset,x}\) and \(\:{k}_{offset,y}\) are too small, they cannot be compensated effectively while if too large, they cause overcompensation, both leading to reduced positioning accuracy. Therefore, the most effective approach is to calibrate the algorithm before formal use and find the optimal \(\:{k}_{offset,x}\:\)and \(\:{k}_{offset,y}\) to ensure optimal performance.

Next, we analyze the effect of each parameter on algorithm performance during target motion, based on the simulation conditions outlined in Sect. 3.3. The results are shown in Fig. 18.

The trends in RMSE with respect to changes in \(\:{k}_{offset,x}\:\) and \(\:{k}_{offset,y}\)are similar to those observed for stationary targets, whereas \(\:{k}_{e}\) exhibits a distinct trend. This is because when \(\:{k}_{e}\) is too small, there is insufficient valid data to localize a moving target, as shown in Fig. 19. Therefore, for the moving target, prioritizing the selection of \(\:{k}_{e}\) is crucial to ensure sufficient valid data before considering its impact on positioning accuracy.

Conclusion

The CBORF algorithm addresses the critical challenge of NLOS-induced errors in UWB-based underground localization, achieving centimeter-level accuracy (RMSE: 0.026 m for stationary targets, 0.075 m for moving targets) while maintaining low computational complexity. In recent years, several algorithms have been developed to achieve accurate localization results. For example, the algorithm in27 achieves an average localization error of 10.3 cm, while the algorithm in28 achieves an RMSE of 0.0137 m. Both algorithms are able to achieve similar localization accuracies as the algorithm in this paper. However, improving localization accuracy inevitably leads to higher computational and hardware costs. The algorithm in27 employs a joint approach, with its algorithmic time cost shown in Fig. 5. The algorithm in28 uses ELPSO and PSO-BPNN, which result in significant computational and time costs29. More importantly, the environments in which they are implemented are not as challenging as those considered in this paper. The only ambient noise they add is Gaussian noise. In contrast, in more demanding environments, the CBORF algorithm achieves excellent localization accuracy while maintaining low computational and hardware costs, demonstrating its superiority.

CBORF leverages a reference coordinate-guided compensation mechanism and adaptive parameter tuning to eliminate the need for resource-intensive filtering or strict linear Gaussian assumptions, outperforming existing hybrid algorithms in both accuracy and efficiency. Its lightweight design aligns with industrial demands for real-time, low-cost deployment in coal mines, offering a scalable solution for safety-critical applications.

This work resolves the longstanding trade-off between accuracy and complexity, setting a new benchmark for scalable, real-time underground localization with direct implications for safety-critical mining applications and beyond. As 5G and IoT technologies evolve, UWB positioning is increasingly integrated with AI-driven frameworks for adaptive NLOS mitigation. CBORF provides a foundational architecture for these integrations. Its parameter-driven design enables future integration with neural networks for dynamic coefficient optimization, bridging the gap between low-cost deployment and cutting-edge innovation.

While simulation results validate CBORF’s theoretical superiority, future work will focus on real-world validation in operational coal mines to assess its robustness against practical challenges. Underground environments exhibit time-varying electromagnetic noise from machinery and dense infrastructure. To mitigate this, CBORF’s adaptive coefficients will be optimized using real-time noise profiling, along with hardware-level shielding for UWB transceivers. Moreover, the optimal placement of reference labels and base stations is critical. We will explore topology optimization strategies to minimize blind zones while ensuring compatibility with existing mine communication frameworks.

Data availability

The datasets used and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Wu, B. et al. Development, effectiveness, and deficiency of China’s coal mine safety supervision system. Resour. Policy 82,103524 (2023).

Wang, F., Tang, H. & Chen, J. Survey on NLOS identification and error mitigation for UWB indoor positioning. Electronics 12, 1678 (2023).

Liu, Y. UWB ranging error analysis based on TOA mode. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 1939, 012001 (2021).

Kim Geok, T. et al. Review of indoor positioning: radio wave technology. Appl. Sci. 11, 279 (2020).

Farid, Z., Nordin, R. & Ismail, M. Recent advances in wireless indoor localization techniques and system. J. Comput. Netw. Commun. 2013, 185138 (2013).

Jiang, R., Yu, Y., Xu, Y., Wang, X. & Li, D. Improved Kalman filter indoor positioning algorithm based on CHAN. J. Commun. 44(2) (2023).

Cong, L. & Zhuang, W. Non-line-of-sight error mitigation in TDOA mobile location. GLOBECOM’01 IEEE Global Telecommun Conf. 1, 680–684 (2001).

Yassin, A. et al. Recent advances in indoor localization: A survey on theoretical approaches and applications. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutorials. 19, 1327–1346 (2016).

Cheng, Y. & Zhou, T. UWB indoor positioning algorithm based on TDOA technology. In Proc. Int. Conf. Inf. Technol. Med. Educ. 214–218 (2019).

Dabove, P. et al. Indoor positioning using ultra-wide band (UWB) technologies: Positioning accuracies and sensors’ performances. In Proc. IEEE/ION PLANS 333–342 (2018).

Doucet, A., Godsill, S. & Christophe Andrieu. On sequential Monte Carlo sampling methods for bayesian filtering. Stat. Comput. 10, 197–208 (2000).

Chen, Z. Bayesian filtering: from Kalman filters to particle filters, and beyond. Statistics 182, 1–69 (2003).

Hua, C. et al. Multipath map method for TDOA based indoor reverse positioning system with improved Chan-Taylor algorithm. Sensors 20, 3223 (2020).

Wang, W. et al. Deep learning-based localization with urban electromagnetic and geographic information. Wirel. Commun. Mob. Comput. 2022, 9680479 (2022).

Liu, J., Deng, Z. & Hu, E. An Nlos ranging error mitigation method for 5 g positioning in indoor environments. Appl. Sci. 14, 3830 (2024).

Zhang, H. et al. Research on high precision positioning method for pedestrians in indoor complex environments based on UWB/IMU. Remote Sens. 15, 3555 (2023).

Mendrzik, R. et al. Harnessing NLOS components for position and orientation estimation in 5G millimeter wave MIMO. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 18, 93–107 (2018).

Park, J. W. et al. Improving deep learning-based UWB LOS/NLOS identification with transfer learning: an empirical approach. Electronics 9, 1714 (2020).

Kim, D. H., Farhad, A. & Pyun, J. Y. UWB positioning system based on LSTM classification with mitigated NLOS effects. IEEE Internet Things J. 10, 1822–1835 (2022).

Qin, Y. et al. An efficient convolutional denoising Autoencoder-Based BDS NLOS detection method in urban forest environments. Sensors 24, 1959 (2024).

Li, S. & Wu, J. Research on NLOS error suppression in UWB based on RICT algorithm. Measurement 244, 116463 (2025).

Merigó, J. M. & Yager, R. R. Aggregation operators with moving averages. Soft Comput. 23, 10601–10615 (2019).

Sanchez, J. M. Linear calibrations in chromatography: the incorrect use of ordinary least squares for determinations at low levels, and the need to redefine the limit of quantification with this regression model. J. Sep. Sci. 43, 2708–2717 (2020).

Ibrahimoglu, B. Ali. Lebesgue functions and Lebesgue constants in polynomial interpolation. J. Inequal. Appl. 2016, 1–15 (2016).

Gasca, M. & Sauer, T. Polynomial interpolation in several variables. Adv. Comput. Math. 12, 377–410 (2000).

Eğecioğlu, Ö., Gallopoulos, E. & Koç, Ç. K. A parallel method for fast and practical high-order Newton interpolation. BIT 30, 268–288 (1990).

Wang, C. et al. Optimized deployment of anchors based on GDOP minimization for ultra-wideband positioning. J. Spat. Sci. 67, 455–472 (2022).

Bellusci, G. et al. Model of distance and bandwidth dependency of TOA-based UWB ranging error. Proc. IEEE Int. Conf. UWB 3, 1–4 (2008).

Lakshmi, Y. V. et al. Improved Chan algorithm based optimum UWB sensor node localization using hybrid particle swarm optimization. IEEE Access. 10, 32546–32565 (2022).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Zecheng Li and Zhipeng Li developed the overall framework of the study and wrote the main manuscript text, conducted the simulation experiments and analyzed the data, contributed to the algorithm design and optimization, assisted in the literature review and provided insights on the TDOA algorithm. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, Z., Li, Z. Reference coordinate based Chan algorithm for UWB personnel localization in underground coal mines. Sci Rep 15, 17922 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03007-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03007-6

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Deep bayesian neural networks for UWB phase error correction in positioning systems

Scientific Reports (2025)