Abstract

This study aimed to compare two deep learning reconstruction (DLR) techniques (AiCE mild; AiCE strong) with two established methods—iterative reconstruction (IR) and filtered back projection (FBP)—for the detection of monosodium urate (MSU) in dual-energy computed tomography (DECT). An ex vivo bio-phantom and a raster phantom were prepared by inserting syringes containing different MSU concentrations and scanned in a 320-rows volume DECT scanner at different tube currents. The scans were reconstructed in a soft tissue kernel using the four reconstruction techniques mentioned above, followed by quantitative assessment of MSU volumes and image quality parameters, i.e., signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) and contrast-to-noise ratio (CNR). Both DLR techniques outperformed conventional IR and FBP in terms of volume detection and image quality. Notably, unlike IR and FBP, the two DLR methods showed no positive correlation of the MSU detection rate with the CT dose index (CTDIvol) in the bio-phantom. Our study highlights the potential of DLR for DECT imaging in gout, where it offers enhanced detection sensitivity, improved image contrast, reduced image noise, and lower radiation exposure. Further research is needed to assess the clinical reliability of this approach.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In recent years, dual-energy computed tomography (DECT) has gained an increasing role in the noninvasive detection and quantification of monosodium uric acid (MSU) tophi in gouty arthritis1,2 owing to its ability to characterize different materials based on their specific attenuation at different energy levels. This allows differentiation of MSU and bone and calcium depositions from surrounding tissues3. DECT can diagnose gouty arthritis with high accuracy and can differentiate gout from other crystal arthropathies, which has been reflected in the ACR/EULAR guidelines since 20154. As an inherently quantitative modality, DECT can be used both for initial assessment and for monitoring therapeutic responses in gout patients5.

The diagnostic accuracy of DECT is particularly high in patients with established gout, where its sensitivity is approximately 90%; however, it is much lower in those with recent-onset gout, with an approximate sensitivity ranging from 35 to 55%1,6. The sensitivity of DECT is limited by the detection threshold that is defined to distinguish MSU from soft tissues with similar dual-energy properties and sets a balance between true-positive and false-positive detections that may occur5. It has been demonstrated that it is possible to lower this detection threshold by reducing image noise, e.g., by using iterative reconstruction (IR) instead of standard filtered back projection (FBP)7. Recent phantom studies in other fields have shown that deep learning reconstruction (DLR) can further enhance image quality and thus improve detectability compared with IR8,9. DLR is an expanding image reconstruction technique that uses trained artificially intelligent algorithms that recognize patterns in the raw or image data and create an optimized image10. Such algorithms therefore harbor the potential to lower radiation exposure in DECT examinations. However, to the best of our knowledge, the effect of DLR on gouty tophi detection in DECT imaging has not yet been investigated.

Therefore, the purpose of our study was to analyze the performance of state-of-the-art DLR compared with standard IR and FBP in the detection of tophi using an established phantom protocol. Based on previous experience, we hypothesize that DLR may increase the detected MSU volumes by reducing image noise and consequently improve sensitivity, reduce radiation exposure, or a combination of both.

Materials and methods

Approval by the institutional review board was not required due to the phantom-based nature of our study. No live animals were involved in this research. The specimens used were obtained from animals slaughtered for food production and sourced from a licensed abattoir.

Phantom models

Two different phantoms were investigated in the study: an ex vivo bio-phantom and a raster phantom, both fabricated according to an established protocol (Fig. 1)7. To simulate gouty tophi of different concentrations, four 2-ml syringes were prepared, each containing MSU (linear formula: C5H3N4O3Na; molecular weight, 190.09; Zeff, 7.7; Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) in a different concentration (35%, 40%, 45%, and 50%) in a suspension with ultrasound gel. An additional syringe filled with pure ultrasound gel served as a negative control. The selection of the four MSU concentrations was based on previous studies7,11.

Raster phantom (a) and bio-phantom (b) . Raster phantom consisting of syringes arranged in a grid-like container, which was subsequently immersed in water. In this study, only the syringes in the front row were analyzed. Porcine foreleg with four syringes containing different MSU concentrations and one negative control, placed around the elbow joint. The negative control is positioned at the 12 o’clock position while the other syringes are arranged clockwise in ascending order of MSU concentrations (35%, 40%, 45%, and 50%).

In the raster phantom, the five samples were arranged in a grid-like plastic container immersed in water. The bio-phantom consisted of a porcine foreleg, fresh from the slaughterhouse, in which five pockets for the syringes were created around the elbow joint. Bone, muscle, and cutaneous and subcutaneous tissues were kept intact to simulate gouty tophi in realistic anatomical surroundings.

DECT protocol and image reconstruction

The raster phantom and the ex-vivo bio-phantom were scanned in a 320-row volume detector CT scanner (Aquillion One Prism; Canon Medical Systems, Japan), implemented in 2021. A total of 10 scans per phantom were acquired in volume mode using the rotate-rotate method, with each scan consisting of two sequential acquisitions: one at the lower tube voltage of 80 kVp and one at the higher tube voltage of 135 kVp. The series of 10 scans per phantom was obtained within a rotation time of 0.275 s. The same tube current settings were applied to both phantoms in ascending order to ensure a comprehensive range of measurement points: 2.75/16.5, 4.125/24.75, 5.5/30.25, 8.25/46.75, 11/63.25, 13.75/79.75, 19.25/110, 24.75/140.25, 30.25/173.25, and 38.5/220 mAs for the 135 kVp and 80 kVp acquisitions, respectively. Acquisition was performed with full z-axis coverage of 16 cm and without table movement. The dose-length-product (DLP) and the CT dose index (CTDIvol) were recorded, and the estimated effective dose (EED) was calculated using a conversion coefficient for upper extremities of 0.0004 mSv/(mGy*cm)12.

Source images as raw-data based material pairs with water/iodine and water/calcium properties were reconstructed using four different methods: FBP, IR (AIDR3Dstrong: adaptive iterative dose reduction at strong iteration level), and two strengths of DLR: AiCE (Advanced intelligent Clear-IQ Engine) in mild and strong versions. Primary reconstruction was performed with a slice thickness of 0.5 mm, an interval of 0.25 mm, and an in-plane resolution of 0.5 × 0.5 mm, using a medium soft tissue kernel without beam hardening compensation as required by restrictions of the postprocessing software. For FBP and IR, the FC16 kernel was applied, while a soft tissue kernel was used for DLR.

To assess the image quality, 80 kVp source datasets for FBP and IR were reconstructed and compared to virtual monoenergetic images (VMIs) for DLR at 60 keV, as the reconstruction of 80 kVp images was not possible for DLR due to software restrictions.

Image postprocessing

The dual-energy datasets underwent secondary postprocessing to reconstruct material maps for each group (object formula: 100/200 Hounsfield Units (HU), gradient: 1.07). For DLR (AiCE), a standard scanner software (Spectral Analysis Version 7.14) was employed on a stand-alone Vitrea solution (Version 7.14.2.227, Vital Images, Canon Medical Systems, Japan). For IR (AIDR) and FBP, DE Image View (Version 6) on the CT console was used.

Image quality assessment

To compare the image quality between the different reconstruction methods, the no-reference metrics signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) and contrast-to-noise ratio (CNR) were used. Image quality was assessed based on 80 kVp image data for FBP and IR, and 60 keV monochromatic data for DLR on 0.5 mm sections. For computation of the SNR and CNR as image quality parameters, regions of interest (ROIs) were manually placed for each scan of each reconstructed group according to the following procedure: For signal measurements, 17.5 mm2 ROI were selected within the 50% MSU syringe. Contrast was quantified as the difference between the signal in the ROI and a corresponding ROI situated in muscle tissue (for the bio-phantom) or in water (for the raster phantom), with both ROIs located in an identical spatial region. Noise was evaluated using the standard deviation calculated within a defined area of 1213.4 mm2 ROI within air, also in an identical location across scans and reconstructions.

SNR was calculated by dividing the signal by the noise, while CNR was defined as the contrast divided by the noise. For each model, the SNR and CNR values for all 10 current levels were averaged within each reconstruction group.

Volumetric analysis

Volumetric analysis was performed using material decomposition with the specified software (Horos v.2.2.0, The Horos Project), which applies threshold-based segmentation. Voxels inside a user-defined ROI that fall within the specified HU range are automatically identified and aggregated to compute the total volume. Threshold values were set between 100 HU and 5000 HU to ensure clear differentiation of MSU crystals from soft tissue. The ROI, defined as the syringe containing the specific MSU concentration, was manually selected based on its predetermined position within the models. In cases where false-positive volumes were detected, the threshold was adjusted until no artifacts were visible. The volume [cm3] detected per syringe was calculated by the software, and the resulting data were later used to manually compute the total detected volume and the mean detected volume in cm3 for each individual scan of the respective tube current per model. To determine the total mean volume per reconstruction method, these 10 individual mean volumes per scan were then combined and manually averaged to obtain the overall mean volume per group.

Statistics

Statistical analysis was conducted using Prism (Version 10, GraphPad, La Jolla, CA) and IBM SPSS Statistics for macOS (Version 29.0). To compare the mean and individual MSU volumes across different concentrations, as well as to compare mean SNR and CNR values between the four reconstruction methods, the non-parametric Friedman test for matched data was used, followed by Dunn’s multiple comparisons test for pairwise comparisons between the groups. The Shapiro-Wilk test for small sample sizes was used to assess normal distribution. Spearman’s correlation was applied for the correlation of non-normally distributed variables. A corrected p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Images and figures

Images used in this study were edited and combined using Canva (Canva Pty Ltd, Sydney, Australia). Tables were created using Microsoft Word 2021 and Microsoft Excel 2021 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, Washington, United States).

Results

DLP ranged from 7.4 mGy*cm to 100.9 mGy*cm; the corresponding EED ranged from 0.003 to 0.04 mSv. Acquisition and dose parameters are summarized in Table 1. Examples of reconstructed images are shown in Fig. 2. An overview of the mixture compositions used to obtain the specific mass fractions of MSU (35%; 40%; 45%; 50%, and 0% as a negative control) is provided in Table 2.

Material maps of DECT scans reconstructed with different reconstruction methods and corresponding CT images (80 kVp image data for FBP and IR, 60 keV monochromatic data for DLR). The color lookup table ‘Rainbow 2’ provided by the software (Horos v.2.2.0, The Horos Project) was used for parts a–c and g–i, with a window level of 220 and a window width of 220, corresponding to a range of 110 HU to 330 HU. Upper section (raster phantom): Concentration-color-coded 3D images of the MSU maps and corresponding CT images reconstructed with FBP (a, d), IR (b, e), and DLR (strong, c, f). The syringes, presented from left to right, contain MSU concentrations in descending order (50%, 45%, 40%, and 35%). Lower section (bio-phantom): Concentration-color-coded 3D images of the MSU maps and corresponding CT images reconstructed with FBP (g, j), IR (h, k), and DLR (strong, i, l). The syringes, containing different MSU concentrations, are arranged around the elbow joint in ascending clockwise order. An increase in true-positive detections with a decrease in false-positive artifacts is seen for DLR as compared with FBP and IR.

Image quality

SNR and CNR differed significantly between the four reconstruction methods for both phantoms (P < 0.0001). The results are presented in Table 3.

Volumetric analysis

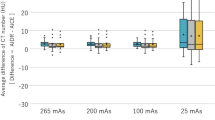

Significant differences in detected MSU volumes were observed between the four reconstruction methods (FBP, IR, and DLR in mild and strong version) in the raster phantom (P < 0.0001) and the bio-phantom (P < 0.0001). Mean detected MSU volumes are shown in Fig. 3.

Mean detected MSU volumes using the four reconstruction techniques investigated in our experimental study. Both DLR methods (AiCE1 – DLR mild; AiCE2 – DLR strong) detected significantly higher amounts of MSU (monosodium uric acid) than FBP (filtered back projection) and IR (iterative reconstruction: AIDR strong).

All four reconstruction methods successfully detected the MSU volume in the syringe with the lowest MSU concentration of 35% in both phantoms, even at the lowest tube current of 2.75/16.5 mAs, as shown in Fig. 4 for the bio-phantom. The supplementary materials provide a comprehensive overview of the detected MSU volumes, including descriptive statistics, statistical analyses, and normality test results for each reconstruction method and phantom. For the raster phantom, the mean MSU volumes detected using the four reconstruction methods across the different MSU concentrations are provided online in Supplementary Figure S1. Detailed results of descriptive statistics and statistical analyses per reconstruction method and phantom are available online in Supplementary Tables S1, S2, S3 and S4. The results of the Shapiro-Wilk tests for normal distribution are provided in Supplementary Table S5.

Mean MSU volumes detected with the four reconstruction methods for different MSU concentrations in the bio-phantom. FBP and IR (AIDR strong) detected significantly smaller MSU volumes, and there were more noticeable variations in detected volumes at different tube currents compared with the two DLR methods (AICE1 - DLR mild version; AICE2 - DLR strong version).

In Fig. 5, mean detected MSU volumes are plotted as a function of the applied CTDIvol for both phantoms. In both phantoms, all four reconstruction methods showed a plateau at higher CTDIvol values. Results in the raster phantom showed a significant positive correlation between the mean detected volume and the CTDIvol across all four reconstruction techniques (FBP: r = 0.733, P = 0.016; IR: r = 0.709, P = 0.022; DLR, mild version: r = 0.879, P < 0.001; DLR, strong version: r = 0.830, P = 0.003). In the bio-phantom, MSU detection correlated less strongly with the applied radiation dose than observed in the raster phantom, and a significant positive correlation between the mean detected volume and the CTDIvol was found only for FBP and IR reconstructions (FBP: r = 0.952, P < 0.001; IR: r = 0.891, P < 0.001), while no such correlation was observed for DLR images (DLR in mild version: r = 0.588, P = 0.074; DLR in strong version: r = 0.394, P = 0.26).

Discussion

This study aimed to evaluate two DLR techniques (AiCE mild; AiCE strong) against two established reconstruction methods, IR and FBP, for the detection of MSU. DLR detected more MSU compared with FBP and IR across all four concentrations investigated in both phantoms. Use of the DLR technique resulted in considerably higher MSU volumes as well as better SNR and CNR values. With all four reconstruction techniques, there was a plateau in MSU volume detection at higher CTDIvol values. In addition, all four reconstruction methods showed a positive correlation of mean detected volumes with CTDIvol in the raster phantom, while no such correlation was observed for the two DLR techniques in the bio-phantom. The major results of our study - MSU volume detection, sensitivity, and image quality - were consistent across both phantoms under equal radiation exposure conditions, suggesting that, due to lower image noise, DLR might improve sensitivity for tophi detection, reduce radiation dose reduction, or both. Interestingly, the lack of correlation between the applied radiation dose and the detected volume for both DLR techniques we investigated indicates that MSU detection in the bio-phantom is less dependent on the applied radiation dose when DLR is used, suggesting that there is a potential for further radiation dose reduction when DECT is used in conjunction with DLR. The plateau in MSU volume detection at higher CTDIvol values suggests that, above a certain threshold, higher doses will no longer improve MSU detection.

MSU detection by DECT imaging can generally be limited by specific characteristics of the tophus, such as lower density, smaller size, and enhancement, if contrast agent is administered7,13,14. Although DLR is increasingly applied in DECT imaging, we are unaware of any study investigating how DLR affects diagnostic performance in patients with gout. However, previous phantom studies and clinical research in other fields have shown results that align with ours15,16,17. For example, Chu et al. reported higher SNR and CNR values, along with improved detectability confidence, when comparing DLR with IR for hepatic lesions in DECT imaging16. Similarly, lower image noise and significantly enhanced diagnostic conspicuity were demonstrated in a study comparing DLR and IR in DECT imaging of pancreatic cancer17. In the setting of musculoskeletal imaging, Gong et al. equally observed a considerable reduction of image noise and artifacts in DECT scans acquired for evaluating the bone marrow of patients suffering from multiple myeloma18. Therefore, and in line with our own results, DLR holds the potential to improve MSU detection sensitivity. This could enable the detection of lower-density gouty tophi, such as in early disease or in patients responding to urate-lowering therapy. For clinical practice, it seems crucial to apply the same reconstruction algorithm for follow-up scans to ensure consistency in the volumetric analysis of tophi. Spatial resolution, a key factor influencing image sharpness and noise, should remain the same in serial scans for reproducible results19. Temporal resolution, total scan time, and spectral projection delay are equally important since higher temporal resolution minimizes spectral projection delay, leading to better synchronization and more accurate spectral data reconstruction and hence reliable comparison between initial and follow-up scans20,21.

To further improve MSU detection, particularly in early gout, post-processing protocols provide an additional avenue for optimization22. While lower thresholds increase the risk of artifact formation and/or false-positive detection, studies have shown that reducing the threshold improves the MSU detection rate23. Research on the effect of DLR in both DECT and single-energy computed tomography (SECT) imaging has demonstrated its ability to reduce the variability of iodine concentration and minimize artifacts17,24. Nevertheless, further clinical research is needed to develop optimized postprocessing protocols for patients with gout that incorporate the effects of DLR on image quality and artifact reduction.

Another key challenge for gout imaging with DECT is selecting a tube current setting that ensures an optimal balance between achieving sufficient image quality and minimizing patient radiation exposure25. Concerns about higher radiation exposure in DECT can be countered, as it has been demonstrated that the combination of DLR and low-dose DECT, compared to standard-dose SECT, allows significant dose reduction while maintaining the image quality essential for diagnostic accuracy20,26,27,28. Potentially, the use of DLR for tophi identification in DECT imaging might even further pave the way for additional tube current adjustment and improved radiation protection of patients. This is particularly crucial in patients with chronic gouty arthritis, who may need repeated imaging examinations.

Ultimately, our findings may expand the already broad application of DLR in DECT imaging of soft tissues, as they align with previous research demonstrating its superiority in reducing image noise, improving image contrast and overall image quality, and enabling dose reduction 15,16,17,26,27,28. Our study found no consistent significant differences between the mild and strong versions of DLR for MSU detection at the concentrations investigated. Notably, studies comparing high-strength DLR (DLR-H) with medium-strength DLR (DLR-M) in abdominal SECT reported minor blurring for very small lesions when using DLR-H24 and no improved visualization of target structures despite reduced image noise with DLR-H29. Further research is needed to explore the subtle effects of DLR-H on the detection of hypoattenuating target structures and how these effects may vary across different radiation dose levels24.

As for limitations, our findings derived from using the rotate-rotate method can only be transferred to other scanners and DECT techniques to a certain extent, as applied reconstructions and tube currents may vary significantly, which can greatly influence tophus detection25. We analyzed a restricted set of MSU concentrations based on our group’s experience. However, our data suggest that lower MSU concentrations might be detectable. We did not compare DLR from different or independent vendors, so our results are confined to the scanners and reconstructions used in our study. Additionally, our DECT scanner does not allow generation of standard 80 kVp images with DLR from a DECT dataset, so 60 keV virtual monochromatic images were used as surrogates for 80 kVp acquisitions, with all inherent limitations. Furthermore, primary input data reconstructed with DLR and IR/FBP are not compatible with all software versions for further postprocessing. However, as material formulas and gradients for postprocessing were the same, we suspect no severe confounders from the different software versions. Challenges in manufacturing crystal suspensions hinder a dependable measurement of syringe volumes. Consequently, no definitive reference for volume metrics can be provided. We acknowledge that the absence of similarity metrics in our evaluation is a limitation. Further studies incorporating these metrics are necessary to validate the trends observed in our results. As our results are derived from phantom experiments, replication in patients is needed before DLR can be safely used for gout imaging in clinical practice.

Our data suggest that DLR allows more sensitive detection of MSU deposits compared with IR and FBP by reducing image noise and detection thresholds. Use of DLR of DECT has the potential to identify tophi with lower density while simultaneously reducing radiation exposure. Importantly, the same reconstruction methods should be used for follow-up examinations to ensure comparability of findings. Yet, this is an explorative phantom approach of applying a deep learning algorithm for DECT image reconstruction that requires clinical validation in patients before it can be used routinely.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Gamala, M., Jacobs, J. W. G. & van Laar, J. M. The diagnostic performance of dual energy Ct for diagnosing gout: A systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Rheumatol. (Oxford). 58, 2117–2121. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/kez180 (2019).

Kotlyarov, M., Hermann, K. G. A., Mews, J., Hamm, B. & Diekhoff, T. Development and validation of a quantitative method for estimation of the urate burden in patients with gouty arthritis using dual-energy computed tomography. Eur. Radiol. 30, 404–412. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00330-019-06350-1 (2020).

Davies, J., Riede, P., van Langevelde, K. & Teh, J. Recent developments in advanced imaging in gout. Ther. Adv. Musculoskelet. Dis. 11, 1759720x19844429. https://doi.org/10.1177/1759720x19844429 (2019).

Neogi, T. et al. 2015 Gout classification criteria: An American college of rheumatology/european league against rheumatism collaborative initiative. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 74, 1789–1798. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2015-208237 (2015).

Sudoł-Szopińska, I., Afonso, P. D., Jacobson, J. A. & Teh, J. Imaging of gout: Findings and pitfalls. A pictorial review. Acta Reumatol Port. 45, 20–25 (2020).

Jia, E., Zhu, J., Huang, W., Chen, X. & Li, J. Dual-energy computed tomography has limited diagnostic sensitivity for short-term gout. Clin. Rheumatol. 37, 773–777. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-017-3753-z (2018).

Diekhoff, T., Kotlyarov, M., Mews, J., Hamm, B. & Hermann, K. G. A. Iterative reconstruction may improve diagnosis of gout: An ex vivo (bio)phantom dual-energy computed tomography study. Invest. Radiol. 53, 6–12. https://doi.org/10.1097/rli.0000000000000402 (2018).

Zhong, J. et al. Evaluation of image quality and detectability of deep learning image reconstruction (dlir) algorithm in single- and dual-energy Ct. J. Digit. Imaging. 36, 1390–1407. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10278-023-00806-z (2023).

Li, H. et al. Performance evaluation of deep learning image reconstruction algorithm for dual-energy spectral Ct imaging: A Phantom study. J. Xray Sci. Technol. 32, 513–528. https://doi.org/10.3233/xst-230333 (2024).

Koetzier, L. R. et al. Deep learning image reconstruction for ct: Technical principles and clinical prospects. Radiology 306, e221257 https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.221257 (2023).

Diekhoff, T. et al. Detection and characterization of crystal suspensions using single-source dual-energy computed tomography: A Phantom model of crystal arthropathies. Invest. Radiol. 50, 255–260. https://doi.org/10.1097/rli.0000000000000099 (2015).

Saltybaeva, N., Jafari, M. E., Hupfer, M. & Kalender, W. A. Estimates of effective dose for Ct scans of the lower extremities. Radiology 273, 153–159. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.14132903 (2014).

Melzer, R., Pauli, C., Treumann, T. & Krauss, B. Gout Tophus detection-a comparison of dual-energy Ct (dect) and histology. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 43, 662–665. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semarthrit.2013.11.002 (2014).

Bongartz, T. et al. Dual-energy Ct for the diagnosis of gout: An accuracy and diagnostic yield study. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 74, 1072–1077. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-205095 (2015).

Zhong, J. et al. Deep learning image reconstruction algorithm reduces image noise while alters radiomics features in dual-energy Ct in comparison with conventional iterative reconstruction algorithms: A Phantom study. Eur. Radiol. 33, 812–824. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00330-022-09119-1 (2023).

Chu, B. et al. A deep learning image reconstruction algorithm for improving image quality and hepatic lesion detectability in abdominal dual-energy computed tomography: Preliminary results. J. Digit. Imaging. 36, 2347–2355. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10278-023-00893-y (2023).

Noda, Y. et al. Deep learning image reconstruction algorithm for pancreatic protocol dual-energy computed tomography: Image quality and quantification of iodine concentration. Eur. Radiol. 32, 384–394. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00330-021-08121-3 (2022).

Gong, H. et al. Deep learning-based virtual noncalcium imaging in multiple myeloma using dual-energy Ct. Med. Phys. 49, 6346–6358. https://doi.org/10.1002/mp.15934 (2022).

Forghani, R., De Man, B. & Gupta, R. Dual-energy computed tomography: Physical principles, approaches to scanning, usage, and implementation: Part 1. Neuroimaging Clin. N Am. 27, 371–384. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nic.2017.03.002 (2017).

Borges, A. P., Antunes, C. & Curvo-Semedo, L. Pros and cons of dual-energy Ct systems: One does not fit all. Tomography 9, 195–216. https://doi.org/10.3390/tomography9010017 (2023).

Parakh, A. et al. Recognizing and minimizing artifacts at dual-energy Ct. Radiographics 41, 509–523. https://doi.org/10.1148/rg.2021200049 (2021).

Klauser, A. S. et al. Impact of dual-energy computed tomography (dect) postprocessing protocols on detection of monosodium urate (msu) deposits in foot tendons of cadavers. Diagnostics (Basel). https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics13132208 (2023).

Dubief, B. et al. Optimization of dual energy computed tomography post-processing to reduce lower limb artifacts in gout. Quant. Imaging Med. Surg. 12, 539–549. https://doi.org/10.21037/qims-21-321 (2022).

Jensen, C. T. et al. Image quality assessment of abdominal Ct by use of new deep learning image reconstruction: Initial experience. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 215, 50–57. https://doi.org/10.2214/ajr.19.22332 (2020).

Kotlyarov, M., Hermann, K. G. A., Mews, J., Hamm, B. & Diekhoff, T. Dual-energy computed tomography: Tube current settings and detection of uric acid Tophi. Eur. J. Radiol. 139, 109692. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejrad.2021.109692 (2021).

Cui, E. Reducing radiation dose in routine Ct scans: An ai-driven approach with deep learning-based dual-energy Ct reconstruction. Eur. Radiol. 34, 26–27. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00330-023-10066-8 (2024).

Noda, Y. et al. Radiation and iodine dose reduced thoraco-abdomino-pelvic dual-energy Ct at 40 Kev reconstructed with deep learning image reconstruction. Br. J. Radiol. 95, 20211163. https://doi.org/10.1259/bjr.20211163 (2022).

Lyu, P. et al. Deep learning reconstruction Ct for liver metastases: Low-dose dual-energy vs standard-dose single-energy. Eur. Radiol. 34, 28–38. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00330-023-10033-3 (2024).

Jiang, J. M. et al. The value of deep learning image reconstruction in improving the quality of low-dose chest Ct images. Diagnostics (Basel). https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics12102560 (2022).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Ms. Bettina Herwig for language editing.

Large Language Models (LLMs)

OpenAI’s ChatGPT (version based on GPT-4 architecture, September 2024) and DeepL Translator (2024) were used for language support in drafting and editing parts of the manuscript. The model’s role was limited to refining the clarity and style of the text. All conceptual work, analysis, and final revisions were carried out by the authors.

Funding

The Department of Radiology has received a research grant from Canon Medical Systems.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.A.S. had primary responsibility for data curation, formal analysis, investigation, validation, visualization, and writing (original draft). T.D. was primarily responsible for funding acquisition and was equally involved in conceptualization and visualization. He also played a supporting role in formal analysis, investigation, methodology, and writing (review and editing). J.M. had primary responsibility for software and was equally involved in investigation, resources, and writing (review and editing). He also had a supporting role in conceptualization, methodology, and supervision. K.K. was equally involved in writing (review and editing). M.K. had a leading role in data acquisition, project administration, supervision, writing (review and editing), and visualization. He was also equally involved in conceptualization and played a supporting role in formal analysis, investigation, and methodology.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

J.M. is employed by Canon Medical Systems Europe BV. However, the corresponding author (S.A.S.), who is not affiliated with the company, had complete control over the data and information submitted for publication. The company did not influence or authorize the results or the publication of our research. The remaining authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Ethics approval, consent to participate, and consent to publish were not required for this study due to its phantom nature.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Schmolke, S.A., Diekhoff, T., Mews, J. et al. Deep learning reconstruction enhances tophus detection in a dual-energy CT phantom study. Sci Rep 15, 18687 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03012-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03012-9