Abstract

Biosurfactants offer good advantages over synthetic counterparts, including biodegradability, environmentally friendly and low toxicity. This study employed a yeast Meyerozyma guilliermondii MX strain for bioconversion of lignocellulosic xylose and palm oil to valuable glycolipid biosurfactant with desirable properties. The objective was to elucidate metabolic pathways related to production of glycolipids and its functional properties. To enhance de novo glycolipid production, manipulation of responsible enzymatic genes was conducted using media and environmental means in comparison to the industrial glycolipid producer, Candida bombicola. Proteomic profiles of yeast cells grown with or without palm oil uncovered novel key metabolic enzymes, namely fatty acid biosynthetic enzymes, leading to formation of glycolipid precursors. qRT-PCR identified some cluster genes responsible for biosynthesis of desirable glycolipids. Finally, LC-MS-based lipidomics of glycolipid fraction identified 15-(2′-O-β-d-glucopyranosyl-β-d-glucopyranosyloxy)hexadecanoic acid 1′,4″-lactone 6′,6″-diacetate (663.4525 m/z) as a major product. Using co-carbon substrates in the presence of salt and zinc, maximum glycolipid yield was achieved (55.72 g/L) with 55.30% emulsification activity and 10 mg/L of CMCs. Mixed glycolipids demonstrated antibiofilm activity against Candida albicans shown by reduction of metabolic activity. The novel biosurfactant-producing yeast M. guilliermondii MX is a promising cell factory of new antibiofilm glycolipids with potential for industrial-scale up.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Biosurfactants are amphiphilic compounds containing both hydrophilic and hydrophobic moieties and are thus used interchangeably to describe surface active biomolecules. A variety of these compounds are produced extra-cellularly, including those used for biosurfactant producing microbes. For example, Pseudomonas spp., Acinetobacter spp., Bacillus spp., and Candida spp.1. These biomolecules tend to reduce the interfacial and/or surface tension of a system, thereby allowing solubilization of hydrophobic substrates2,3. Biosurfactants are ideal candidates for various biochemical and biotechnological applications because, according to several studies, their critical micelle concentration (CMC) value is lower than that of synthetic ones4.

Glycolipids are major class of microbial-derived surfactant. Yeast glycolipids are partly derived from lipid metabolism, which takes place in the cytosol and requires acetyl-CoA as the core precursor. In non-oleaginous yeasts, acetyl-CoA originates from the mitochondria, whereas in oleaginous yeasts, citrate is the acetyl donor for fatty acid biosynthesis5. Among oil-producing microorganisms, the cofactor NADPH is mainly produced through the pentose phosphate pathway, which plays an important role in intracellular lipid synthesis6. Among glycolipidic biosurfactants, sophorolipids (SLs) are the most notable family, synthesized in high concentrations by several non-pathogenic yeast species with potential industrial applications7. SLs are amphiphilic molecules that interact using with hydrophilic sophorose head consisting of two β-1,2 linked glucose molecules, and a hydrophobic fatty acid with chain length of 16–18 mers8. SLs occur as a mixture of compounds that differ in their acetylation pattern, lactonization, extent of unsaturation, and position of hydroxylation9. The production of SLs or other glycolipids is mainly associated with yeasts closely related to Candida such as C. bombicola. Recently, several new SL producing strains have been discovered, including Wickerhamiella domercqiae, Pichia anomala and some members of the genus Candida namely C. batistae, C. riodocensis, C. stellata and Candida sp. Y-27,208. Additionally, Rhodotorula bogoriensis, a basidiomycete, has also been reported as SL producer10,11,12,13.

Optimal medium composition and co-substrate utilization are effective approach to enhance biosurfactant yield and reduce the production cost. Previously, the ratio and concentration of carbon and nitrogen sources are determined to increase SL yields in yeast Starmerella riodocensis GT-SL1R sp. nov. strain14,15. Impressive SL yields of 26.41–22.34 g/L for S. riodocensis GT-2564R and 21.40–19.91 g/L for S. bombicola BCC5426 are obtained by cultivating these yeasts in flasks with 1% yeast extract or soybean meal as a nitrogen source, at pH 4.5 15. When both strains are cultured for the upscaled production in 5 L bioreactors using soybean meal as a substitute nitrogen source in glucose containing media, SL yields increasing to 36.6–40.82 g/L and a high productivity of 0.22–0.24 g/L · h15. SL yields increased by 35–43% following scale-up, and the product included both lactonic and acetic forms. The main component of the hydroxy fatty acid composition is found to be 17-hydroxy oleic acid (42.91–45.94%), followed by 15-hydroxy palmitic acid (35.74–38.34%), precursors for bioplastics14. Recently, S. riodocensis GT-SL1R sp. nov. strain produced maximum SLs productivities at 0.8 g/L · h in mixed forms of lactonic and acidic SLs16.

Promising production of glycolipids calls for active search of involved biosynthetic pathways and key enzymes. A whole-genome analysis of S. riodocensis identified novel gene clusters, including CYP52M1, UGTA1, UGTB1, SLAT, and SBLE15 with some similarity to those identified for S. bombicola17,18. Five genes are involved in SLs production. Two enzymes, UDP glucosyltransferase A1 and UDP glucosyltransferase B1, encode UGTA1 and UGTB1, and SLAT, the gene that mediate acetylation reactions using acetyl coenzyme A (AcCoA)19. In the biosynthesis of secondary metabolite, cytochrome P450 monooxygenase, encoded by the CYP52M1 gene, initiates the conversion of fatty acids to hydroxy fatty acids. Furthermore, the SBLE gene encodes a lactone esterase enzyme which is involved in protein turnover, chaperoning, and posttranslational modification17.

Among others, M. guilliermondii YK32 is optimized for biosurfactant production, using supplemented 8% (w/v) glucose, 8% (v/v) olive oil, 1.5% (w/v) ammonium sulfate, 1.5% (w/v) yeast extract, 1.5% (w/v) urea, and 3% (w/v) NaCl at pH 6.0 at 30 °C for 6 days in a rotary flask shaker at 150 rpm. The biosurfactant glycolipid type produced the maximum oil displacement of 8.8 cm20 which is the highest length reported. Recently, we identify a potential biosurfactant yeast producer namely M. guilliermondii strain MX for efficient xylose utilization. It is capable of generating valuable sweetening compound xylitol from a pentose sugar, with a yield of 0.49 g/g of xylose consumed21. Additionally, the strain can also tolerate high osmotic stress and concentrated lignocellulosic furfural inhibitor at 1.2 g/L21. Thus, M. guilliermondii MX strain might be a suitable and robust cell factory to produce high glycolipid biosurfactant. As previously reported for members of Pichia anamola11, using co-substrates glucose and palm oil produced biosurfactant with a reduced surface tension of 28 mN/m. Previous report, xylolipids (XLs) biosurfactant production from yeast Pichia caribbica, the maximum productivity of 0.04 g/L h (7.5 g/L of XL) is obtained using 100 g/L xylose and 4% (v/v) oleic acid22.

Our study first compared the lipid biosynthetic pathways of M. guillermodii to in the model yeast strains to and applied insights from this work and existing literature to identify key biosynthetic and regulatory steps in xylolipid biosynthesis. We investigated the prospective utilization of co-carbon substrates xylose, a lignocellulosic sugar, and palm oil as abundant substrate by M. guilliermondii MX strain for biosurfactant production. Omic approach was applied to uncover novel biosynthetic enzymes and explored upscaling fermentation process and potential applications.

Materials and methods

Preparation of yeast inoculum and fermentation medium

The yeast M. guilliermondii MX strain was grown and maintained on YPD medium (10 g/L yeast extract, 20 g/L bacto-peptone and 20 g/L dextrose) at 30 °C under shaking condition at 150 rpm for 24 h, following the method by14. The fermentation medium was supplemented with 8% (w/v) xylose, 8% (v/v) palm oil, 1.5% (w/v) ammonium sulfate, 1.5% (w/v) yeast extract, 1.5% (w/v) urea, and 3% (w/v) NaCl in 1 L, with the pH adjusted to 6.0. To measure the dry weight of the yeast cells (CDW), 50 mL of fermentation broth was centrifuged at 6000g for 5 min. The pellet was washed twice cold distilled water at a 1:1 ratio and dried at 65 °C in a hot air oven for 24 h. Productivity was calculated using the formula below:

\({\text{Productivity}}={\text{Amount}}\;{\text{of}}\;{\text{GLs}}\;{\text{produced}}\;\left( {{\text{g}}/{\text{L}}} \right)/{\text{CDW }}\left( {{\text{g}}/{\text{L}}} \right) \cdot {\text{Time}}\;{\text{taken }}\left( {{\text{in hours}}} \right)\)

Batch fermentation

For biosurfactant production, M. guilliermondii MX with an OD600 of 1.0 or cell dry weight (CDW) of 0.23 g/L, was incubated in 50 mL of fermentation medium at 30 °C for 10 days in a rotary flask shaker at 150 rpm. The fermentation broth was tested every 48 h to detect the concentration of xylose, cell biomass, and xylolipid yield. Based on the shaking flask experiment, the optimized fermentation strategy was further verified in a 5 L stirred fermenter (Winpact FS-05 fermenter), and compared with the performance of conventionally optimized medium. Next, in a 4 L capacity fermenter, the fermentation medium was incubated at 30 °C with a stirring speed of 150 and 300 rpm, and an aeration rate of 1.0 vvm. The dissolved oxygen (DO) concentration was maintained at 20% after 24 h by keeping the agitation speed constant at 300 rpm with aeration rate of 1.0 vvm. The fermentation broth was tested every 48 h to detect the concentration of xylose, cell biomass, and xylolipid yield.

Gene induction and quantitative RT-PCR (RT-qPCR)

The M. guilliermondii MX strain was grown and maintained on YPD medium (10 g/L yeast extract, 20 g/L bacto-peptone and 20 g/L dextrose). For gene expression under palm oil or NaCl stress, the M. guilliermondii MX strain was cultured in fermentation medium containing 8% (w/v) xylose, 8% (v/v) palm oil, 1.5% (w/v) ammonium sulfate, 1.5% (w/v) yeast extract, 1.5% (w/v) urea, and 3% (w/v) NaCl with pH adjusted to 6.0. Cultures were grown with and without palm oil to an approximate OD600 of 1.0 for 48 h before RNA extraction and purification using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). The cDNA synthesis was carried out with the qPCRBIO cDNA synthesis kit. The qRT-PCR assays analysis and data were performed using a CFX Connect™ Real-Time PCR System (Bio-Rad, CA, USA). The reaction mixtures contained the Luna® Universal One-Step RT-qPCR Kit. The relative quantification of each transcript was calculated using the 2−∆∆Ct method23. All experiments were performed in triplicate, with the GAPDH1 gene used as internal control, presented in Table 1.

Protein digestion for gel-free based proteomics

To investigate the protein expression profile of different treatment conditions, the extracted proteins were prepared according to previous studies24. Briefly, yeast cells samples were lysed by lysis buffer solution containing 0.5% Triton X-100, 10 mM DTT, 10 mM NaCl in 50 mM HEPES-KOH (pH 8.0). the extracted proteins were precipitated using ice-cold acetone and stored at − 20 °C for 16 h. After precipitation, the protein pellet was reconstituted in 0.25% RapidGest SF (Waters, UK) in 10 mM ammonium bicarbonate. Protein concentrations were determined using the Bradford Reagent assay kit (Sigma, USA), with bovine serum albumin as the standard. The total protein content of 30 µg was subjected to trypsin digestion. Sulfhydryl bonds were reduced using 10 mM DTT in 10 mM ammonium bicarbonate at 62 °C for 20 min, and alkylation of sulfhydryl at room temperature for 25 min in the dark. The solution was then cleaned using desalting column (Thermo Scientific, USA). The flow-through solution was enzymatically digested by trypsin (Thermo Scientific, LT) at a ratio of 1:50 (enzyme: protein) and incubated at 37 °C for 3 h. The digested peptides were reconstituted in 0.1% formic acid and transferred to a TruView LCMS vial (Waters, UK).

LC–MS/MS setting for proteomics analysis

A total of 1.0 µg peptides were subjected to LC-MS/MS. Spectral data were collected in a positive mode on a SCIEX TRIPLE TOF-6600 + mass spectrometer (ABSCIEX, Germany) combined with an EASY-nLC1000 nano-liquid chromatography (LC) system (Thermo Scientific, USA) equipped with a nano analytical column (75 μm i.d. × 15 cm, packed with Acclaim PepMap™ C18) (Thermo scientific, Germany). The LC conditions were as follows: Mobile phase A and B were used, with mobile phase A composed of 0.05% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) in water and mobile phase B comprised of 80% acetonitrile with 0.04% TFA. The samples were loaded onto the nano analytical column and separated using linear gradient from 3 to 35% B over 95 min at a constant flow rate of 300 nL/min. The analytical column was regenerated at 90% B for 10 min and re-equilibrated at 5% B for 15 min.

The eluted peptides were analyzed using LC-MS/MS. The MS acquisition time was set from gradient time zero to 120 min, and the MS1 spectra were collected in the mass range of 400 to 1500 m/z with 250 ms acquisition time in “high sensitivity” mode. Further fragmentation of each MS1 spectrum occurred with a maximum of 30 precursors per cycle. The switching criteria used were as the follows: charge of 2 + to 5+, intensity threshold of 500 cps and dynamic exclusion for 15 s.

SWATH-MS data for individual samples were acquired on LC-MS/MS exactly as described previously. SWATH acquisition was conducted in a data-independent acquisition (DIA) mode. The MS1 spectra were collected in the mass range of 400 to 1250 m/z in “high sensitivity” mode. The variable Q1 isolation windows were optimized based on the spectral library using SWATH Acquisition Variable Window Calculator25. Collision energy was different for each window. Single injections of biological triplicates were performed.

The raw MS-spectra files resulting (.wiff) file were extracted and annotated with protein sequences using the Paragon™ Algorithm by ProteinPilot™ Software26. The M. guilliermondii protein database (5,798 sequences), retrieved from UniProtKB and used in Paragon™, was assembled in FASTA format and downloaded in August 2022. The protein data were filtered with a threshold of [Unused ProtScore (Conf)] ≥ 0.05, with a 1% false discovery rate (FDR) and ≥ 10 peptides/protein. The protein and peptide comparisons showing > 20% coefficient of variation (C.V.) between the replicates were rejected. Both library and the SWATH-MS data were imported into SWATHTM processing micro application in PeakView® software.

Glycolipid biosurfactant characterization

Purified glycolipid was collected after eluted with gradient system (eluted 20% methanol in chloroform). 100 mg/mL of purified GLs was characterized by HPLC (Shimadzu, Japan) with a UV detector (207 nm) and a UPS C18 column (VertiSep ™, 5 μm, 4.6 × 250 mm using gradient elution. The mobile phase was a linear gradient of 20% acetonitrile in water for 15 min, followed by 20–80% acetonitrile for 25 min, and then 80–100% acetonitrile for 10 min. The final mobile phase was 100% acetonitrile for 20 min at a flow rate of 0.5 ml/min27. For acid-alkaline hydrolysis was conducted by 5 µL of 37% (w/v) HCL mixed with 1 mL of purified GL into a glass tube. Then, the solution was boiled for 5 min at 100 °C in boiling water and add 12 µL of 5 M KOH as adapted from Rietschel et al.28. Cells samples were collected from fermentation media and centrifuged at 6,000 rpm for 15 min at room temperature. The resulting cell pellets were used to estimate biomass production during biosurfactant production. The pellets were dried to constant weight at 65 °C in a hot air oven for 24 h. Xylose consumption was measured by using HPLC (Shimadzu, Japan) with an Aminex HPX-87 H ion-exchange column (300 × 7.8 mm i.d.) (Bio-Rad). The mobile phase consisted of 5 mM H2SO4 at a flow rate of 0.68 ml/min for 45 min and a column temperature of 60 °C29.

Measurement of emulsion stability and oil spreading

The emulsification index of the culture supernatant was determined using palm oil. Equal volumes (2 mL) of cell-free supernatant and palm oil were mixed in a test tube, vortexed for 2 min and allowed to stand for 24 h at room temperature. The height (cm) of the emulsified layer formed at the interface of palm oil and cell-free supernatant was then recorded. The results were compared with 0.2% SDS and distilled water as positive controls and negative control, respectively. The stability of the emulsion layer was calculated as EI24% by dividing the total height of the emulsion by the total height of the aqueous layer and then multiplying the result by 100 30. These experiments were carried out in triplicate.

Water (20 mL) was to a culture dish with a diameter of 11 cm. Then, 10 µL of engine oil was added by droplets. After the stable oil film was formed, 10 µL of cell-free supernatant (CFS) was added onto the center of the film. The diameter of the spreading oil was measured31. The experiment was carried out in triplicate.

Critical micelle concentration (CMC)

A stock solution of M. guilliermondii-synthesized glycolipid biosurfactant (100 mg/L) was prepared in MilliQ water and diluted to give final concentrations within the range of 10 mg/L to 100 mg/L. Surface tension was measured, at 25 °C, using the DY-300 surface tension meter (KYOWA, Japan). The surface tensions of the desired solutions were measured, according to the tensiometer operating manual. All surface tension measurements were averaged from 4 readings recorded at an interval of 30 s15.

FTIR for functional group identification

The presence of different functional groups in the mixture of glycolipids was determined by Fourier Transform infrared (FTIR spectroscopy (PerkinElmer). The FTIR spectra were performed in the 550–4000 cm−1 region in attenuated total refectance (ATR) mode.

Liquid chromatography and mass spectrometry

The metabolites were separated and measured using a Vanquish UHPLC coupled to an Orbitrap Exploris 480 mass spectrometer (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) equipped with heat-electrospray ionization (HESI) probes. Chromatographic separations were performed using Ascentis® Express 160 Å C30 (4.6 mm ID × 10 cm, 2.7 μm particle size) at a flow rate of 0.4–0.45 mL/min. A column temperature of 60 °C and injection volume of 5.0 µL. The mobile phase system consisted of 50%acetonitrile/water (A) and 90% iso-propanol/10%acetonitrile (B), both acidified with 0.1% of formic acid and 10mM ammonium formate (freshly prepared), Gradient starting conditions were 95% MP: A and 2% MP: B. Starting conditions were held for 2 min before raising to 55% MP: B over 18 min. The column was flushed with 99% MP: B for 2 min before returning to starting conditions. The total time of each analysis was 30 min. Small molecule for monoisotopic peak determination was used. The MS acquisition in positive and negative mode with 20 number of dependent scans. The LC-MS/MS data was obtained through a data-dependent acquisition approach using the AcquireX mode, with background removal algorithm by Xcalibur software (Thermo Fisher Scientific). To provide a concise overview, two independent LC runs were carried out using blank samples, incorporating both full scan MS (SIM) and DDA modes. Following these runs, the Xcalibur software was utilized to generating exclusion mass lists for subsequent subtraction in the testing sample.

Data processing for identification and quantification metabolites

The identification and quantification of lipids were performed using Lipid search™ 5.1 (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The acquired raw MS files underwent both positive and negative mode data processing, which included peak identification, peak alignment, and peak feature extraction. Product was selected as the identification type, the quality deviation of precursor ion and product ion in library was 5 ppm, and the response threshold was set as the relative response deviation of product ion 5.0%; The quantitative parameter was set to calculate the peak areas of all identified lipids, and the mass deviation of peak extraction was set to 5 ppm; The filter is set as top rank, all isomer peak, FA priority, M- score was set as 5.0, c-score was set as 2.0, and the identification level was selected as “A”, “B”, “C” and “D”. All lipid categories were selected for identification; Adduct forms of positive ion mode were [M + H]+, [M + NH4]+, [M + Na]+, and of negative ion mode were [M-H]- and [M-2 H]- and [M-HCOO]-. All lipids with identified results were peak-aligned, and results not marked as “rejected” were considered for further analysis. The peak alignment method was set as Mean, the retention time deviation was set as 0.1 min, the peak filtering was set as top rank, and all isomer peaks. The analysis of differential metabolites was visualized using a volcano plot, which was generated based on differential fold change and adjusted p-values. The metabolites with area lower than 5 × 107 will be rejected.

Anti-biofilm activity of GLs against Candida albicans

The metabolic and biofilm inhibition activities of crude and purified glycolipid mixture against Candida albicans biofilms was evaluated using the XTT reduction and crystal violet assays. Initially, C. albicans (ATCC 90028) was cultured overnight in RPMI 1640 medium in the presence of 10% glucose at 37 °C with constant shaking at 150 rpm. Flat-bottomed 96-well plates were used to develop Candida biofilms. A cell suspension prepared in RPMI 1640 medium was standardized to a density of 1 × 106 CFU/mL. This suspension was added to the microplate wells, filling each with a total volume of 100 µL. For young biofilm formation, the plates were incubated at 37 °C for 90 min, while for mature biofilms, a 24 h incubation period was used. Following the incubation step, any non-adherent cells were eliminated by washing the wells with 0.15 M sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Glycolipid solutions were prepared at varying concentrations with a max concentration of 1024 µg/mL) in RPMI 1640 medium and subsequently added (100 µL/well) to the pre-formed biofilms. Untreated biofilm wells served as the control group. The plates were then incubated at 37 °C for an additional 24 h to determine the impact of glycolipids on Candida biofilms.

Quantification of metabolic activity (XTT assay)

Following treatment, the biofilm supernatant was removed, and the wells were washed gently with PBS to eliminate residual glycolipids and any non-adherent cells. The XTT reduction assay was performed by preparing an XTT-menadione solution composed of 1 mg/mL XTT (2,3-bis-(2-methoxy-4-nitro-5-sulfophenyl)-2 H-tetrazolium-5-carboxanilide)32. Then, 100 µL of this solution was added to each well, followed by incubation in the dark at 37 °C for 2 h. Metabolically active biofilm cells reduced the XTT, resulting in a colored formazan product, which was quantified by measuring absorbance at 490 nm using a Multiskan Sky microplate reader (Thermo Scientific, USA).

Biofilm Inhibition (CV assay)

The biofilm inhibition of Candida albicans by glycolipids was assessed using the crystal violet33 assay as previously described32. Following treatment of glycolipids as mentioned above, the wells were gently washed with sterile PBS to remove any residual glycolipids and non-adherent cells. The remaining biofilm was stained with 0.1% crystal violet solution (200 µL per well) and incubated at room temperature for 45 min. The plates were then air-dried. Subsequently, 200 µL of 95% ethanol was added to each well to solubilize the bound crystal violet, and the absorbance was measured at 590 nm using a microplate reader.

Data analysis

Each experiment was carried out independently at least twice, and three duplicates of each condition were tested. Presented as mean ± standard deviation are the results. The statistical analysis was conducted with GraphPad Prism 8.0.0 for Windows. (GraphPad Software, San Diego, California, USA; www.graphpad.com), employing one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s pairwise comparison. Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05.

Results

Proteomic analysis of yeast M. guilliermondii MX strain during glycolipid production

Despite increasing applications of yeast derived-glycolipid biosurfactants, less is known regarding its biosynthesis. Limited numbers of potential yeast producers have been reported for economical upscaling of glycolipids; therefore, new knowledge is imperative to enhance the glycolipid production. The focus of this study is the involved metabolic pathways and responsible glycolipid biosynthetic enzymes.

Given that palm oil is an abundant bioresource with low selling price, it can be used as a key hydrophobic carbon substrate for glycolipid production. This study first aimed to compare protein expression during xylose-palm oil co-utilization to identify essential enzymes/proteins. Proteomic analysis annotated key proteins in a yeast culture media supplemented with and without palm oil as a source of fatty acids after 48 h of cultivation in the early stage of xylose fermentation. The identification of 856 intracellular proteins from the yeast cells of M. guilliermondii MX strain was analyzed by LC-MS/MS. The complete list of identified proteins can be found in Supplementary Table 1.

The proteomic analysis showed significantly increased expression levels of proteins in many cellular pathways, including primary and secondary metabolism. For examples, the ribosomes, TCA cycle, respiratory chain, unfolded protein binding, alcohol dehydrogenases, COPI vesicle coat, branched-chain amino acid biosynthetic process, proteasome-mediated ubiquitin-dependent protein catabolic process, pyridoxal phosphate binding, thioredoxin, biotin/lipoyl attachment, aminoacyl-tRNA biosynthesis, proton-transporting ATP synthase activity, Arp2/3 protein complex, PHB, GTP binding, 4 iron, 4 sulfur cluster binding, ATP-grasp folding, protein importation into mitochondrial matrix, FMN binding, oxidoreductase activity, fatty acid metabolism, D-threo-aldose 1-dehydrogenase activity, proteasome regulatory particle, thiamine pyrophosphate binding, AMP-dependent synthetase/ligase, aldehyde/histidinol dehydrogenase, and mitochondrial carrier domain were found (Fig. 1A). These proteins play key roles in stress response pathways involving antioxidation and maintaining redox homeostasis. In contrast, some proteins such as protein kinase, peroxisomal membrane protein, sphingolipid 4-desaturase, dolichyl-phosphate-mannose-protein mannosyltransferase showed reduced expression levels of more than 2-folds (Fig. 1A).

Given that glycolipids produce highly during the stationary phase of growth, the protein levels were then compared between the early fermentation phase (48 h) and the late stationary phase (at 192 h) of xylose-palm oil fermentation. Increased protein expression levels were observed for proteins in the proteasome, pyridoxal phosphate-dependent transferase, chaperone, aminoacyl-tRNA biosynthesis, AAA + ATPase domain, tricarboxylic acid cycle, FMN binding, electron transport, polyketide synthase, enoyl reductase, thioredoxin domain, NAD, valine, leucine, and isoleucine biosynthesis, valine, leucine, and isoleucine degradation, UBA-like, aldo/keto reductase subgroup, lysine degradation, proton-transporting ATP synthase activity, 4 iron, 4 sulfur cluster binding, fatty acid metabolism, protein import into mitochondrial matrix, ATP-grasp folding, subdomain 1, L-aspartase-like, Snf7, PHB, Superoxide dismutase activity, oxidoreductase activity, biotin/lipoyl attachment, and Thiamine pyrophosphate (Fig. 1B).

Conversely, some protein clusters showed a more than 2-fold decrease in expression levels in the ribosome, ATP-binding, proteasome, aminoacyl-tRNA biosynthesis, GTP binding, ABC transporter, aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase, valine, leucine, and isoleucine biosynthesis, lipid biosynthesis, cellular amino acid biosynthetic process, aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase, chaperonin-containing T-complex, ATP-grasp fold, pyruvate carboxyltransferase, cellular bud neck (Fig. 1A). Thus, late stationary at 192 h of fermentation significantly reduced the level of acyl CoA, leading to a corresponding decrease in GLs yield (Supplementary Table 2). These proteins are important for amino biosynthesis and cellular protein synthesis as well as maintaining energy and cellular homeostasis.

At day 2 of palm oil induction, protein of biosynthesis of cofactors, PPP, oxidative stress, fatty acid elongation, and longevity regulating pathway were upregulated (Fig. 1C). The protein–protein interaction (PPI) network of visualized by STRING was analyzed. The results showed an enrichment map of KEGG and GO genes of pentose and glucuronate interconversions, biosynthesis of cofactors, stress adaptation, and fatty acid elongation linked to fatty acid biosynthesis34,35,36. The results showed interactions between many proteins in various pathways, indicating that palm oil influences key metabolic and stress adaptation processes. This suggests an integrated response to metabolic pathways, stress adaptation, and lipid metabolism are modulated, likely help in cellular adaptation to the palm oil presence. Furthermore, specific proteins, like Dolichyl-phosphate-mannose-protein mannosyltransferase, peroxisomal membrane proteins, and certain protein kinases, were downregulated (Fig. 1C), which could imply a shift in cellular resource allocation or reduced activity in specific pathways as the organism adapts to palm oil-rich in early stationary phase.

At day 8, Fatty acid metabolism, AAA + ATPase domain and electron transport were upregulated (Fig. 1D) with palm oil induction. Fatty acid metabolism continues to be upregulated, likely to process the increased lipid content from palm oil. This may indicate sustained or increased fatty acid catabolism and modifications. AAA + ATPase Domain Proteins, these proteins often participate in various cellular activities, including protein unfolding, DNA replication, and cellular stress responses, suggesting an ongoing adaptation or stress response to palm oil-rich. Upregulation of electron transport components might reflect an increase in energy requirements for fatty acid metabolism and associated cellular processes. Moreover, protein of ribosomal, proteosome, aminoacyl-tRNA biosynthesis, fatty acid metabolism, cellular bud neck, and ABC transporter were downregulated (Fig. 1D). Ribosomal and proteasomal pathways reduced activity in protein synthesis and degradation pathways could indicate a shift in cellular resources, possibly due to an adaptation phase where the cell focuses more on metabolic processing than growth or protein turnover. Downregulation of Aminoacyl-tRNA biosynthesis, this may indicate reduced protein synthesis demands, as seen with ribosomal activity. Cellular bud neck, a decline in cellular bud neck-related proteins might suggest a reduced rate of cell division or structural remodeling. Downregulation of ABC transporter imply altered nutrient or metabolite transport priorities as the cell adapts to palm oil in late stationary phase. Proteins such as xylose reductase (Xyl1), mitochondria carrier, and TCA cycle enzymes were upregulated during palm oil induction (Fig. 1E). Overall, the dramatic changes in protein expression occurred during co-carbon substrate utilization and generated stress, pushing forward to xylose reduction, respiration and de novo fatty acid synthesis (Fig. 1E).

Proteomic profiles of M. guilliermondii during fermentation of 8% xylose, 8% palm oil, 1.5% ammonium sulphate, 1.5% yeast extract, 1.5% urea, and 3% NaCl were compared under conditions of 8% palm oil versus no palm oil on Day 2. Protein expression cluster analysis of the M. guilliermondii MX strain during palm oil addition on Day 2 showed upregulated (in green) and downregulated (in red) proteins (A). Proteomic profiles of M. guilliermondii were also compared for the condition induced with 8% palm oil on Day 8 (late stationary phase) and Day 2 (early stationary phase) (B). A protein–protein interaction (PPI) network was visualized using STRING, with an enrichment map of KEGG and GO genes linked to fatty acid biosynthesis when induced with palm oil in the M. guilliermondii MX strain on Day 2 (C) and Day 8 (D). Palm oil induced the expression of proteins involved in xylose metabolism, the PPP, the TCA cycle, fatty acid metabolism, and the ER stress response (fold change) (E). The KEGG database (https://www.kegg.jp/kegg/kegg1.html) was queried to identify proteins involved in glycolipid biosynthesis.

Sequence analysis of the ITS1-5.8 rDNA-ITS2 region and comparative identification of proteins

The relationships between M. quilliermondii culture CBS:2084 and M. quilliermondii MX strain, which is obtained from the NCBI database, are displayed by sequence analysis of the ITS1-5.8 rDNA-ITS2 region, with 100% identity (Supplementary Fig. 1). To uncover key enzymes involved in GLs biosynthesis, we then performed comparative genome analysis of M. guilliermondii and other yeast species including S. bombicola known to produce high levels of glycolipids. The number of genes that were differentially expressed between the comparison groups was shown using a Venn diagram, and additional analysis was done on the differentially expressed genes that overlapped. There were fifty-six overlapping differentially expressed genes in S. bombicola and M. guilliermondii. There were forty-seven overlapping differentially expressed genes in P. sorbitophila and M. guilliermondii.

Protein sequence alignments of cytochrome P450 monooxygenase (M. guilliermondii) that has 45.9% sequence similarity to cytochrome P450 monooxycytogenase (S. bombicola), mannan polymerase II complex ANP1 subunit (M. guilliermondii) that has 83.8% sequence similarity to glucosyltransferase (P. sorbitophila), maltose/galactoside acetyltransferase (M. guilliermondii) that has 45.9% sequence similarity to acetyltransferase (S. bombicola), glycolipid transfer protein (M. guilliermondii) that has 80.7% sequence similarity to MDR transporter (P. sorbitophila), ceramide glucosyltransferase (M. guilliermondii) that has 55.6% sequence similarity to lactonesterase (P. sorbitophila), respectively (Fig. 2A).

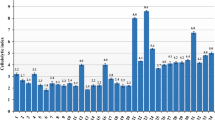

Next, to confirm the role of these putative enzymes in the production of glycolipids (GLs) from xylose-palm oil fermentation, gene expression analysis via qRT-PCR was conducted using M. guilliermondii cells. Expression of potential GL biosynthetic genes in M. guilliermondii was dramatically up-regulated in palm oil induction, after 48 h, including cytochrome P450 monooxygenase (CYP52M1) (193.9- fold), Mannan polymerase II complex Anp1 subunit (ANP1) (117.8- fold), Maltose/galactoside acetyltransferase (UGTA1) (567.1- fold), Glycolipid transfer protein (GLPT) (114.2- fold) and Ceramide glucosyltransferase (UGCG) (138.7-fold), respectively (Fig. 2B).

After, induction of zinc sulfate and dissolved oxygen (DO) controlling at 20% were found to significantly increase the expression of genes involved in GLs biosynthesis. These include the identified enzymes encoding by CYP52M1 (38.5-fold), ANP1 (9.0-fold), UGTA1 (104.0-fold), GLPT (30.04-fold) and UGCG (32.2-fold), respectively (Fig. 2C) during zinc sulfate induction and CYP52M1 (320.7-fold), ANP1 (17.8-fold), UGTA1 (783.5-fold), GLPT (108.5-fold) and UGCG (117.4-fold), respectively, (Fig. 2C) during DO controlling at 20%. Thus, the results indicated key factors for promoting gene expression of GLs biosynthetic enzymes. Also, expression of lipid droplet biosynthetic genes, such as AYR1 (encoding NADPH-dependent 1-acyldihydroxyacetone phosphate reductase), GPD1 (encoding glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase), and PDS2 (encoding Phosphatidylserine decarboxylase proenzyme 1) were dramatically upregulated by palm oil and NaCl induction (Fig. 2D). These genes encoded proteins involved in lipid metabolism to increase the lipid accumulation capacity of this yeast.

Comparison of amino acid sequences between Starmerella bombicola, Pichia sorbitophila and M. quilliermondii (A). The alignment analysis was performed by using BLAST (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi). Positions of identical residues are highlighted with in purple on the aligned sequences. Residues without highlights indicate difference in properties, and the alignments show the percentage of similarity. Comparison of sophorolipid biosynthesis in S. bombicola and glycolipid biosynthesis in M. quilliermondii, including with enzyme synthesis pathways, such as cytochrome P450 monooxygenase, mannan polymerase II complex ANP1 subunit, maltose/galactoside acetyltransferase, glycolipid transfer protein and ceramide glucosyltransferase, respectively in M. guilliermondii (B). Relative expression of M. guilliermondii genes was analyzed via qRT-PCR. The M. guilliermondii was induced with palm oil, zinc sulfate, with fixed DO at 20% for 48 h for glycolipid biosynthesis genes (C), and with 8% palm oil and 3% NaCl for 48 h for lipid droplet biosynthesis genes (D). The relative mRNA levels of the induced cells were compared to the non-induced cells and normalised with a housekeeping gene, GAPDH1. At least two independent qRT-PCR experiments were performed in triplicates.

GLs production in M. guilliermondii in shaking flask or 5-L bioreactor

Next, the production of glycolipids was investigated to identify suitable culture condition for upscale production. GLs were produced either in a shaking flask (240 h) or in a 5 L bioreactor with controlled 20% DO for 120 h–48 h. These conditions produced the highest yields of 84.67, 159.42, and 95.09 g/L of crude GLs with productivities of 0.97, 1.14, and 3.07 (g/g CDW∙h), respectively (Tables 2, 3). M. guilliermondii MX strain completely consumed xylose within 240, 120, and 48 h, respectively, under condition. The result showed that, xylose was consumed fastest in 5 L bioreactor with controlled DO at 20% and the end of fermentation ending after 48 h (Table 3). After purification of the crude GLs were purified by 20% methanol, given 37.97, 78.53 and 44.43 g/L of purified GLs (Tables 2, 3). Thus, GLs yields were improved with a higher oxygen utilization rate, which is beneficial for GLs production by M. guilliermondii. The lower fermentation product concentrations at 192 and 240 h. may be due to depletion of nutrients such as carbon and nitrogen sources that can limit microbial growth and the production of GL biosurfactants. Changes in surface tension, toxicity, the regulation of metabolic feedback, or high concentrations of product s could also be inhibiting factor in GL production.

Lipid characterization by orbitrap-based LC-MS/MS

High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) was performed to identify crude (Fig. 3A) and purified glycolipid fraction (Fig. 3B) obtained from the fermentation medium supplemented with xylose and palm oil as co-substrate. The extracted lipid fraction of M. guillermondii MX strain was compared using the acidic and lactonic (lactonic di-acetylated) standards (Carbosynth Ltd) of the model yeast C. bombicola. For HPLC analysis, peaks were recorded at retention times (RT) of 56.717, 58.724, and 64.004 min in purified glycolipids corresponding those of lactonic form (Fig. 3B) as shown in previous report15.

After acid-alkaline hydrolyzed, HPLC showed a peak corresponding to the peak at RT value 9.808 min (Fig. 3D). The xylose concentration approximately was quantified to contain 0.414 mg/mL of xylose released after the purified glycolipid fraction was broken down by acid-alkaline hydrolysis. No peak at the same RT was found in the non-hydrolyzed fraction (Fig. 3E). The result indicated the release of this xylose, suggesting that the formation of GLs that may contain the monomeric xylose or xylose-based linkages as structural components. Low xylose concentration may imply limited amount of xylose in the GLs biosynthesis as xylose might have been converted to other upstream metabolites during the metabolism of xylose and in the PPP.

Additionally, other lipid classes were identified with MS2 spectra from single orbitrap scans of purified glycolipid fraction as small peaks were also detected by HPLC (Fig. 3F) including exact mass (m/z) of 241.2028, 460.2689, 241.2037, 353.2659, 663.44525, 565.5665, 850.7875, and 549.5435 respectively. These included Cer (Ceramides) in sphingolipids class, DG (Diacylglycerol) and PG (Phosphatidylglycerols) in glycerophospholipid class, MG (Monoacylglycerol), MGDG (Monogalactosyldiacylglycerol) and TG (Triacylglycerol) in Glycerolipid class, SPH (Sphingosines) in Sphingolipids class, and WE (wax ester) in phospholipids class (Fig. 3G and H).

Characterization of crude (A) and purified (B) glycolipids isolated from M. quilliermondii MX strain cultured in xylose and palm oil-containing media on Day 2 was performed by high Performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), separated on a UPS C18 column, VertiSep™ (Reverse phase column, 5 μm, 4.6 × 250 mm) with a UV detector (207 nm). Gradient elution (acetonitrile and water) at a total flow rate of 0.5 mL/min was used, the chromatograms at 207 nm were analysed and compared. The concentration of xylose after acid-alkaline hydrolysis was detected by HPLC, separated on an Aminex HPX-87 H ion-exchange column, Bio-Rad (7.8 × 300 mm), with a mobile phase consisting of 5 mM H2SO4 at a flow rate of 0.68 ml/min and, a refractive index detector. The retention time of the xylose standard was 9.806 min (C). The addition of acid-alkaline hydrolysis showed a retention time of xylose at 9.808 min (D) and non-hydrolyzed (E). The chromatogram of lipid profiles in purified glycolipid was obtained by Orbitrap-based LC–MS/MS, calculating m/z of molecular ions (F), classes of lipids identifying (G) and lipid structure (H). Cer ceramide, DG diglyceride, MG monoacylglycerol, MGDG monogalactosyldiacylglycerol, PG phosphatidylglycerol, SPH sphingolipids, TG triacylglycerols.

Potential chemical structures of GLs from the partially purified fraction

First, investigation of key functional groups of glycolipids was performed using FTIR spectroscopy on partially purified fraction (Fig. 4A). The first peak at 3006.78 cm−1 represented alkenes (= C–H stretch). The IR peaks of 2922.18 cm−1 and 2852.97 cm−1 corresponded to methylene groups (C–H stretch). Interestingly, FTIR spectroscopy of glycolipid SLs produced by S. bombicola BCC5426 and by S. riodocensis GT-SL1R strain16 exhibited similar features to the partially purified glycolipids produced by M. guilliermondii MX strain (Fig. 4A). Additionally, esters, lactones, or acids were present owing to the C=O stretch at the absorption peak of 1742.65 cm−1. The C–O–H in-plane bending of carboxylic acid (–COOH) was also identified at 1463.36 cm−1. The C–O stretch absorption band could be found at 1237.79 cm−1, contributing to acetyl esters, while the stretch at 1160.34 cm−1 is related to the C–O band of C(–O)–O–C in lactones. Furthermore, the C–O stretch of the C–O–H group of sugar could be observed at 1097.62 cm−1. The structural details of both FTIR spectra were similar as previously reported37. The potential structure of GLs included C16 fatty acid, also known as hexadecanoic acid or palmitic acid, making up the core structure, and glycoside that is a glycolipid containg glucose moieties (glucopyranosyl groups). Lactone ring comprised of a cyclic ester, which could affect biological activity, suggested to be the 1′,4″-lactone. Acetate group which determines solubility and bioavailability may be impacted by the ester-like characteristics of the 6′,6″-diacetate (–OCOCH3) functional group (Fig. 4B), corresponding to sophorolipids (C32H54O14). Moreover, according to LC–MS–MS lipidomic database, an exact mass of 663.4525 m/z was found for the partially purified glycolipid fraction with the chemical structure of sophorolipid 16-(2′-O-β-d-glucopyranosyl-β-d-glucopyranosyloxy)hexadecanoic acid 1′,4″-lactone 6′,6″-diacetate (https://www.lipidmaps.org/databases) as shown (Fig. 4B). Overall, the biochemical and structural data suggested that the partial purified glycolipids contain SLs in majority and low level of GLs which may difficult for detection. Additional structural characterization of glycolipid derivatives using NMR study will be essential; nevertheless, the purification of glycolipid fraction must be first achieved to elucidate multiple derivatives. Nevertheless, this study provided the first stepping stone toward the production and application of high potential glycolipid biosurfactant.

Identification and characterization of partially purified glycolipids determined by FTIR (A) and the potential structure of 16-(2′-O-beta-d-glucopyranosyl-beta-d-glucopyranosyloxy)hexadecanoic acid 1′,4″-lactone 6′,6″-diacetate (B) that was created using Chemical Sketch Tool (https://www.rcsb.org/chemical-sketch).

Emulsification index (EI24) and critical micelle concentration (CMC)

The emulsifying activity of the GLs biosurfactant produced by M. guilliermondii strain MX was also determined by measuring of the emulsion index (EI24). The emulsion index of the glycolipid biosurfactant produced by MX strain after 48, 96, 144, 192, and 240 h of incubation in a 250 mL shaking flask was 52.26%, 52.15%, 55.54%, 58.55% and 56.46%, respectively. These results indicated that the optimum production and activity of biosurfactant, in terms of emulsification layer, were achieved after 192 h, with highest oil displacement activity (6.87 cm) and reduced surface tension from 72.5 to 46 mN/m (Table 4). Meanwhile, the emulsion index of the GLs biosurfactant produced by M. guilliermondii MX strain after 24, 48, 72, 96, and 120 h without DO control in a 5 L bioreactor was 47.27%, 47.58%, 51.97%, 52.37%, and 53.65%, respectively. These results indicated that the optimum production and activity of the biosurfactant were achieved after 120 h, with highest oil displacement activity (7.15 cm) and reduced surface tension from 72.5 to 46 mN/m (Table 4). Additionally, the emulsion index of the GLs biosurfactant produced by M. guilliermondii MX strain after 12, 24, 36, and 48 h during controlled DO at 20% in a 5 L bioreactor was 49.25%, 50.89%, 51.04%, and 55.30%, respectively. These results indicate that the optimum production and activity of the biosurfactant, in terms of the emulsification layer, were achieved after 48 h, with highest oil displacement activity (6.53 cm) and reduced surface tension from 72.5 to 45 mN/m (Table 4).

Moreover, the critical micelle concentration (CMC), or which is the concentration at which surfactant molecules undergo in cooperative self-assembly in solution, is a crucial characteristic of a surfactant. The critical micelle concentration (CMC) of the GLs biosurfactant produced in flask after 192 h was 10 mg/L which was comparable to S. bombicolar and S. riodocensis15.

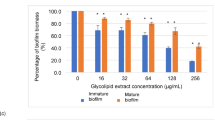

The inhibitory effect of antimicrobial glycolipid GLs on C. albicans biofilm

The C. albicans biofilm was evaluated using the XTT assay, comparing two types of young and old biofilms. The young biofilm was formed after 90 min of incubation and pre-formed biofilms developed over a 24 h period (Fig. 5A and B). The results revealed a concentration-dependent inhibition of biofilm formation and metabolic activity for both young and mature biofilms, as indicated by the percentage inhibition. At lower concentrations of glycolipids, the results showed limited inhibition of metabolic activities and biofilm, suggesting that a minimum effective concentration is required to disrupt biofilm integrity by half at approximately 256 to 512 µg/mL for the young and old biofilm, respectively (Fig. 5). However, at increasing concentrations, there was a significant reduction in metabolic activities, demonstrating the potent antibiofilm property of the purified GLs (Fig. 5C and B).

Effects of glycolipid (GL) treatments on young Candida albicans biofilms. Comparison of metabolic activity (A), and anti-biofilm activity (B) of crude versus purified GL against young C. albicans biofilms. Additionally, comparison of metabolic activity (C), and anti-biofilm activity (D) of crude versus purified GL against preformed C. albicans biofilms. The percentage inhibition of biofilm activity in treated biofilms was compared to untreated controls. Significant differences between crude and purified GL at each concentration are indicated by *, with p < 0.05.

Discussion

Proteins of xylose reductase (Xyl1), mitochondria carrier, and TCA cycle enzymes were upregulated during palm oil induction. This upregulation promoted carbon metabolism, lipid metabolism, and acetyl-CoA accumulation in the yeast cells, leading to an increased flux of carbon for glycolipid biosynthesis. Additionally, the upregulation of ATP synthase activity (Atp enzymes) provided the energy required for the entire metabolic processes of glycolipid synthesis from xylose. This was accompanied by an increased expression of AMP-dependent synthetase/ligase (long-chain acyl-CoA synthetase) and, coat protein I, which is38 that is a coated transport of proteins and lipids in the early secretory pathway. Indeed, the optimizing cultivation media has been found to significantly improve yields of SLs through key pathways of lipid metabolism, utilizing citrate as the acetyl donor in the fatty acid biosynthesis5. Recent, proteomic analysis of yeast S. cerevisiae revealed that xylose-induced pathways also significantly affect major processes, including ribosome biogenesis, mitochondrion metabolism, cytoplasmic translation, isopeptide bond, amino acid biosynthesis, tricarboxylic acid cycle, sterol biosynthesis, and CDR ABC transportation29, suggest that xylose serve as key alternative substrate in lipid biosynthesis and accumulation, with NADPH also playing a crucial role in the lipid biosynthesis pathways, as shown in the SL biosynthesis pathway.

In a previous report, in the early secretory pathway, protein and lipid transport was found to be mediated by coat protein I-coated transport vesicles38. Based on the reconstruction of COPI-coated vesicle formation from chemically defined liposomes, the fundamental machinery required for the formation of these transport intermediates has been clarified39. The coat components, including coatomer and GTP-bound ADP-ribosylation factor (ARF), along with p23, a membrane-bound receptor for COPI coat proteins, were demonstrated to be both sufficient and necessary in this experimental system to promote the formation of COPI-coated vesicles40. Initially, the removal of MFE-2 from the β-oxidation pathway resulted in the build-up of cytoplasmic acyl-CoA, which in turn impeded the function of ATP: citrate lyase. Additionally, previous work showed that the extremely low ratio of acetylated glycolipid SLs and low efficiency of secretion, are caused by the significantly reduced supply of cytoplasmic acetyl-CoA, led to a decrease titer of SLs upon cultivation. Thus, acyl transferase is a crucial enzyme that is linked to the lipid production pathway41.

Thus, we discovered high levels of novel and crucial enzymes which associated with enhanced glycolipid biosynthesis in M. guilliermondii, including cytochrome P450 monooxygenase, mannan polymerase II complex (ANP1) subunit, maltose/galactoside acetyltransferase, glycolipid transfer protein and ceramide glucosyltransferase. Previous reports suggested that Glycolipid transfer protein (GLTP) may functions as a reporter or sensor of glycolipid levels on the cytosolic side of the plasma membrane or the endoplasmic reticulum42. Long-chain acyl-CoA synthetase (dAcsl), which catalyzes the conversion of fatty acids into acyl-coenzyme as (acyl-CoAs), plays a critical role in regulating systemic lipid homeostasis43. The conserved regulon of heat shock factor 1 in budding yeast includes chaperones for general protein folding as well as zinc-finger protein Zpr1, whose essential role in archaea and eukaryotes remains unknown44.

Lipid classes of crude glycolipids were identified, we found diacylglycerols are intermediates in lipid metabolism and act as signaling molecules in cells, cell membrane biophysics and immunomodulators45. Monoacylglycerols are used as emulsifiers due to their amphiphilic structure, which helps disperse hydrophobic substances in water28 and signaling molecules and anti-inflammatory properties46. Triacylglycerols are less commonly used as biosurfactants but can serve as feedstocks for microbial degradation and breakdown28 and anti-inflammatory activity47. Ceramides and sphingosine are important in cell membrane structure and signaling particularly in immune responses48. Also, wax esters are important in anti-inflammatory and anti-obesogenic actions49.

The surface tension of distilled water was from 72.5 to 45 mN/m at the CMC value of 10 mg/L was found in the GLs. The reduction in surface tension demonstrated the efficiency of the biosurfactant and its excellent activity to displace oil, as compared to S. bombicola (1.17 cm)50. The results also indicate that controlling DO at 20% with an air aeration rate of 1.0 vvm increased surface tension because oxygen levels impact on the formation of biosurfactants by microorganisms51. High oil displacement property and efficient surface tension reduction in oil remediation allow glycolipids to be used as biosurfactants in the environmental sector such as oil spill cleanup. They can effectively reduce the surface tension between oil and water, which aids in the breakdown and dispersion of oil slicks52. Glycolipids can form stable emulsions with metals and assist in the bioremediation of heavy metals from contaminated soils and wastewater53. They could reduce interfacial tension and help mobilize residual oil in reservoirs to enhanced oil recovery54. For environmental applications such as soil washing, they can also help remove hydrophobic organic compounds and heavy metals from contaminated soils by binding with contaminants and facilitating their extraction from soil particles55. In wastewater treatment, they can aid in breaking down and removing organic pollutants, oils, and greases from wastewater, improving the efficiency of treatment processes56. Thus, versatile applications of glycolipids could be further explored.

As mentioned, the early-stage C. albicans biofilms were more susceptible to GL treatment. This could be due to the immature extracellular matrix and loosely adhered cells in young biofilms, making them more vulnerable to antimicrobial agents. In contrast, pre-formed biofilms displayed comparatively lower inhibition percentages, even at higher concentrations of GLs, which aligns with the well-documented resistance of mature biofilms due to their robust matrix and higher cell density57. Our findings suggested that GLs could be more effective when administered at the initial stages of biofilm formation, potentially serving as a preventive antifungal strategy against the pathogenic yeasts including C. albicans. These amphiphilic nature of the GLs attributed to their unique lipid structures, possibly enabling them to target and disrupt fungal cell membranes. The antifungal mechanisms of GLs against Candida may involve direct interaction with the cell membrane, leading to increased membrane permeability and subsequent cell lysis. Further work will be required to elucidate GLs action to inhibit Candida biofilm formation, a critical virulence factor that enhances fungal resistance to antifungal treatments32. Nevertheless, the ability of GLs to disrupt biofilms is noteworthy, as biofilm-associated infections are notoriously difficult to treat due to their resistance to conventional antifungal and antimicrobial therapies.

Conclusion

The yeast M. guilliermondii MX strain produced valuable glycolipids biosurfactant from xylose and palm oil fermentation. Glycolipid (GLs) production was achieved using the co-carbon substrates xylose and palm oil at a maximum yield of 55.72 g/L and productivity of 3.76 g/g CDW h or 4.64 g/L · h under a controlled dissolved oxygen (DO) level of 20%. Key factors for enhanced GL production include addition of palm oil, NaCl, and Zn2+, as well as good aeration at 20% DO. Palm oil induces cellular responses due to the accumulation of toxic polar lipids, including glycolipids. The activation of genes and corresponding proteins involved in fatty acid and triglycerides metabolism, lipid droplets (LDs) formation, transporters, and stress responses is noted. Fermentation of xylose and palm oil by M. guilliermondii exhibits promising qualities in the novel GL biosurfactant, paving the way for the development of innovative products that exhibit a variety of useful properties and applications beyond traditional fields. Their biochemical properties, critical micelle concentration (CMC), and ionic performance also make GLs valuable as emulsifiers and in cosmetic or therapeutic agents, where they can be used to dissolve key bioactive ingredients. Importantly, GLs demonstrate potent antifungal activity through metabolic and biofilm inhibition which is unique for a bio-emulsifying agent compared to the synthetic counterparts. Selecting unique xylose-utilising yeasts to efficiently metabolize hemicellulosic hydrolysates or lignocellulosic sugars could enable sustainable use of biomass and agro-industrial waste. Thereby, engineering strains of M. guilliermondii offer promising opportunities for cost-effective and efficient biotechnological processes in xylose-palm oil fermentation for future industrial and medical applications.

Data availability

All data are available either in the main text or in the supplementary information.

Abbreviations

- CDW:

-

Cell dry weight

- CMCs:

-

Critical micelles concentration

- CYP52M1 :

-

Starmerella bombicola cytochrome P450 monooxygenase

- DO:

-

Dissolved oxygen

- FA:

-

Fatty acid

- HPLC:

-

High performance liquid chromatography

- LC–MS/MS:

-

Liquid chromatography mass spectrometry

- MDR :

-

Starmerella bombicola Sophorolipid transporter

- NaCl:

-

Sodium chloride

- PO:

-

Palm oil

- RT-PCR:

-

Real-time reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction

- SBLE :

-

Starmerella bombicola lactone esterase

- SLAT :

-

Starmerella bombicola acetyltransferase

- SLs:

-

Sophorolipids

- UGTA1 :

-

Starmerella bombicola glucosyltransferase I

- UGTB1 :

-

Starmerella bombicola glucosyltransferase II

- GLs:

-

Glycolipids

- Zn2+ :

-

Zinc sulphate

References

Sachdev, D. P. & Cameotra, S. S. Biosurfactants in agriculture. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 97, 1005–1016. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00253-012-4641-8 (2013).

Markande, A. R., Acharya, S. R. & Nerurkar, A. S. Physicochemical characterization of a thermostable glycoprotein bioemulsifier from Solibacillus silvestris AM1. Process. Biochem. 48, 1800–1808. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procbio.2013.08.017 (2013).

Ashby, R. D., Solaiman, D. K. Y. & Foglia, T. A. Property control of sophorolipids: influence of fatty acid substrate and blending. Biotechnol. Lett. 30, 1093–1100. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10529-008-9653-1 (2008).

Qamar, S. A. & Pacifico, S. Cleaner production of biosurfactants via bio-waste valorization: a comprehensive review of characteristics, challenges, and opportunities in bio-sector applications. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 11, 111555. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jece.2023.111555 (2023).

Jezierska, S., Claus, S. & Van Bogaert, I. Yeast glycolipid biosurfactants. FEBS Lett. 592, 1312–1329. https://doi.org/10.1002/1873-3468.12888 (2018).

Ratledge, C. The role of malic enzyme as the provider of NADPH in oleaginous microorganisms: a reappraisal and unsolved problems. Biotechnol. Lett. 36, 1557–1568. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10529-014-1532-3 (2014).

Daverey, A., Dutta, K., Joshi, S. & Daverey, A. Sophorolipid: a glycolipid biosurfactant as a potential therapeutic agent against COVID-19. Bioengineered 12, 9550–9560. (2021). https://doi.org/10.1080/21655979.2021.1997261

De Clercq, V., Roelants, S. L. K. W., Castelein, M. G., De Maeseneire, S. L. & Soetaert, W. K. Elucidation of the natural function of sophorolipids produced by Starmerella Bombicola. J. Fungi (Basel). 7, 917. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof7110917 (2021).

Van Bogaert, I. N. et al. Microbial production and application of sophorolipids. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 76, 23–34. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00253-007-0988-7 (2007).

Chen, J., Song, X., Zhang, H. & Qu, Y. Production, structure Elucidation and anticancer properties of sophorolipid from Wickerhamiella domercqiae. Enzyme Microb. Technol. 39, 501–506. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enzmictec.2005.12.022 (2006).

Thaniyavarn, J. et al. Production of sophorolipid biosurfactant by Pichia anomala. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 72, 2061–2068. https://doi.org/10.1271/bbb.80166 (2008).

Kurtzman, C. P., Price, N. P. J., Ray, K. J. & Kuo, T. M. Production of sophorolipid biosurfactants by multiple species of the Starmerella (Candida) Bombicola yeast clade. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 311, 140–146. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1574-6968.2010.02082.x (2010).

Van Bogaert, I. N. A., Zhang, J. & Soetaert, W. Microbial synthesis of sophorolipids. Process. Biochem. 46, 821–833. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procbio.2011.01.010 (2011).

Intasit, R. & Soontorngun, N. Enhanced palm oil-derived sophorolipid production from yeast to generate biodegradable plastic precursors. Ind. Crops Prod. 192, 116091. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indcrop.2022.116091 (2023).

Taowkrue, E., Songdech, P., Maneerat, S. & Soontorngun, N. Enhanced production of yeast biosurfactant sophorolipids using yeast extract or the alternative nitrogen source soybean meal. Ind. Crops Prod. 210, 118089. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indcrop.2024.118089 (2024).

Alfian, A. R., Watchaputi, K., Sooklim, C. & Soontorngun, N. Production of new antimicrobial palm oil-derived sophorolipids by the yeast Starmerella riodocensis Sp. Nov. against Candida albicans hyphal and biofilm formation. Microb. Cell. Factories. 21, 163. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12934-022-01852-y (2022).

Van Bogaert, I. N. A. et al. The biosynthetic gene cluster for sophorolipids: a biotechnological interesting biosurfactant produced by Starmerella Bombicola. Mol. Microbiol. 88, 501–509. https://doi.org/10.1111/mmi.12200 (2013).

Saerens, K. M., Van Bogaert, I. N. & Soetaert, W. Characterization of sophorolipid biosynthetic enzymes from Starmerella Bombicola. FEMS Yeast Res. 15 https://doi.org/10.1093/femsyr/fov075 (2015).

Saerens, K. M. J., Saey, L. & Soetaert, W. One-step production of unacetylated sophorolipids by an acetyltransferase negative Candida Bombicola. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 108, 2923–2931. https://doi.org/10.1002/bit.23248 (2011).

Sharma, P., Sangwan, S. & Kaur, H. Process parameters for biosurfactant production using yeast Meyerozyma guilliermondii YK32. Environ. Monit. Assess. 191, 531. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10661-019-7665-z (2019).

Zahoor, F., Sooklim, C., Songdech, P., Duangpakdee, O. & Soontorngun, N. Selection of potential yeast probiotics and a cell factory for xylitol or acid production from honeybee samples. Metabolites 11 https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo11050312 (2021).

Joshi-Navare, K., Singh, P. K. & Prabhune, A. A. New yeast isolate Pichia caribbica synthesizes xylolipid biosurfactant with enhanced functionality. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 116, 1070–1079. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejlt.201300363 (2014).

Livak, K. J. & Schmittgen, T. D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods 25, 402–408. (2001). https://doi.org/10.1006/meth.2001.1262

Krobthong, S. et al. The anti-oxidative effect of Lingzhi protein hydrolysates on lipopolysaccharide-stimulated A549 cells. Food Biosci. 41, 101093. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fbio.2021.101093 (2021).

Schilling, B., Gibson, B. W. & Hunter, C. L. Generation of High-Quality SWATH(®) acquisition data for Label-free quantitative proteomics studies using TripleTOF(®) mass spectrometers. Methods Mol. Biol. (Clifton N J). 1550, 223–233. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4939-6747-6_16 (2017).

Shilov, I. V. et al. The Paragon algorithm, a next generation search engine that uses sequence temperature values and feature probabilities to identify peptides from tandem mass spectra. Mol. Cell. Proteom. MCP. 6, 1638–1655. https://doi.org/10.1074/mcp.T600050-MCP200 (2007).

Kim, J. H. et al. Valorization of waste-cooking oil into sophorolipids and application of their methyl hydroxyl branched fatty acid derivatives to produce engineering bioplastics. Waste Manag.. 124, 195–202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2021.02.003 (2021).

Rietschel, E. T., Gottert, H., Lüderitz, O. & Westphal, O. Nature and linkages of the fatty acids present in the lipid-A component of Salmonella lipopolysaccharides. Eur. J. Biochem. 28, 166–173. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1432-1033.1972.tb01899.x (1972).

Songdech, P. et al. Increased production of Isobutanol from xylose through metabolic engineering of Saccharomyces cerevisiae overexpressing transcription factor Znf1 and exogenous genes. FEMS Yeast Res. 24 https://doi.org/10.1093/femsyr/foae006 (2024).

Araújo, S. et al. MBSP1: a biosurfactant protein derived from a metagenomic library with activity in oil degradation. Sci. Rep. 10 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-58330-x (2020).

Archana, K., Sathi Reddy, K., Parameshwar, J. & Bee, H. Isolation and characterization of sophorolipid producing yeast from fruit waste for application as antibacterial agent. Environ. Sustain. 2, 107–115. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42398-019-00069-x (2019).

Watchaputi, K., Jayasekara, L., Ratanakhanokchai, K. & Soontorngun, N. Inhibition of cell cycle-dependent hyphal and biofilm formation by a novel cytochalasin 19,20–epoxycytochalasin Q in Candida albicans. Sci. Rep. 13, 9724. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-36191-4 (2023).

Carneiro, C., de Paula, E. S. F. C. & Almeida, J. R. M. Xylitol production: identification and comparison of new producing yeasts. Microorganisms https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms7110484 (2019).

Kanehisa, M., Furumichi, M., Sato, Y., Matsuura, Y. & Ishiguro-Watanabe, M. KEGG: biological systems database as a model of the real world. Nucleic Acids Res. 53, D672–D677. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkae909 (2024).

Kanehisa, M. Toward Understanding the origin and evolution of cellular organisms. Protein Sci. 28, 1947–1951. https://doi.org/10.1002/pro.3715 (2019).

Kanehisa, M. & Goto, S. KEGG: Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 28, 27–30. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/28.1.27 (2000).

Ma, X. J., Li, H., Shao, L. J., Shen, J. & Song, X. Effects of nitrogen sources on production and composition of Sophorolipids by Wickerhamiella domercqiae Var. Sophorolipid CGMCC 1576. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 91, 1623–1632. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00253-011-3327-y (2011).

Goodrow, S. M., Ruppel, B., Lippincott, R. L., Post, G. B. & Procopio, N. A. Investigation of levels of perfluoroalkyl substances in surface water, sediment and fish tissue in new Jersey, USA. Sci. Total Environ. 729, 138839. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138839 (2020).

Tsvetanova, N. G. The secretory pathway in control of endoplasmic reticulum homeostasis. Small GTPases. 4, 28–33. https://doi.org/10.4161/sgtp.22599 (2013).

Reinhard, C., Schweikert, M., Wieland, F. T. & Nickel, W. Functional reconstitution of COPI coat assembly and disassembly using chemically defined components. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 100, 8253–8257. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1432391100 (2003).

Yang, L. et al. Metabolic profiling and flux distributions reveal a key role of acetyl-CoA in sophorolipid synthesis by Candida Bombicola. Biochem. Eng. J. 145, 74–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bej.2019.02.013 (2019).

Mattjus, P. Glycolipid transfer proteins and membrane interaction. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA) Biomembr. 1788, 267–272. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbamem.2008.10.003 (2009).

Li, J. et al. Long-chain acyl-CoA synthetase regulates systemic lipid homeostasis via glycosylation-dependent lipoprotein production. Life Metab. 3 https://doi.org/10.1093/lifemeta/loae004 (2024).

Sabbarini, I. M. et al. Zinc-finger protein Zpr1 is a bespoke chaperone essential for eEF1A biogenesis. Mol. Cell. 83, 252–265e213. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2022.12.012 (2023).

Eichmann, T. O. & Lass, A. DAG Tales: the multiple faces of diacylglycerol—stereochemistry, metabolism, and signaling. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 72, 3931–3952. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00018-015-1982-3 (2015).

Lopes, G., Daletos, G., Proksch, P., Andrade, P. B. & Valentão, P. Anti-inflammatory potential of Monogalactosyl diacylglycerols and a monoacylglycerol from the edible brown seaweed Fucus spiralis Linnaeus. Mar. Drugs. 12, 1406–1418. https://doi.org/10.3390/md12031406 (2014).

Castoldi, A. et al. Triacylglycerol synthesis enhances macrophage inflammatory function. Nat. Commun. 11, 4107. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-17881-3 (2020).

Lee, M., Lee, S. Y. & Bae, Y. S. Functional roles of sphingolipids in immunity and their implication in disease. Exp. Mol. Med. 55, 1110–1130. https://doi.org/10.1038/s12276-023-01018-9 (2023).

Schots, P. C., Pedersen, A. M., Eilertsen, K. E., Olsen, R. L. & Larsen, T. S. Possible health effects of a wax ester rich marine oil. Front. Pharmacol. 11, 961. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2020.00961 (2020).

Yalçın, H. T., Ergin-Tepebaşı, G. & Uyar, E. Isolation and molecular characterization of biosurfactant producing yeasts from the soil samples contaminated with petroleum derivatives. J. Basic. Microbiol. 58, 782–792. https://doi.org/10.1002/jobm.201800126 (2018).

Banat, I. M. et al. Microbial biosurfactants production, applications and future potential. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 87, 427–444. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00253-010-2589-0 (2010).

Ng, Y. J. et al. Recent advances and discoveries of microbial-based glycolipids: prospective alternative for remediation activities. Biotechnol. Adv. 68, 108198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biotechadv.2023.108198 (2023).

Castelein, M. et al. Bioleaching of metals from secondary materials using glycolipid biosurfactants. Min. Eng. 163, 106665. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mineng.2020.106665 (2021).

Aghaei, S. et al. A micromodel investigation on the flooding of glycolipid biosurfactants for enhanced oil recovery. Geoenergy Sci. Eng. 230, 212219. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoen.2023.212219 (2023).

Zhang, X., Zhang, X., Wang, S. & Zhao, S. Improved remediation of co-contaminated soils by heavy metals and PAHs with biosurfactant-enhanced soil washing. Sci. Rep. 12, 3801. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-07577-7 (2022).

Malkapuram, S. T. et al. A review on recent advances in the application of biosurfactants in wastewater treatment. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 48, 101576. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seta.2021.101576 (2021).

Trubenová, B., Roizman, D., Moter, A., Rolff, J. & Regoes, R. R. Population genetics, biofilm recalcitrance, and antibiotic resistance evolution. Trends Microbiol. 30, 841–852. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tim.2022.02.005 (2022).

Acknowledgements

Facility uses are supported by Biochemical Technology division, School of Bioresources and Technology, King Mongkut’s University of Technology Thonburi. The authors thank Dr. W. Samakkarn and members of the excellent research laboratory of Yeast innovation and biochemical technology division for kind assistance.

Funding

This research project is supported by King Mongkut’s University of Technology Thonburi (KMUTT), Thailand Science Research and Innovation (TSRI), and National Science, Research and Innovation Fund (NSRF) Fiscal year 2025 (No. 68A306000081), National Research Council of Thailand (NRCT) and King Mongkut’s University of Technology Thonburi for Mid-Career Researcher grant (No. N42A650315), Excellent Research Laboratory for Yeast Innovation of Fiscal Year 2023 (No. 6620864), and King Mongkut’s University of Technology Thonburi’s Postdoctoral Fellowship (No. 27586).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, PS and NS; methodology, PS, YY, LA and NS; formal analysis, PS, LA, YY, CB, and NS; investigation, PS, KW, YY, CB and NS; resources, CB and NS; writing—original draft preparation, PS, LA, and YY; writing—review and editing, NS; supervision, NS; project administration, NS; funding acquisition, NS. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

All authors have given their consent for the publication of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Songdech, P., Jayasekara, L.A.C.B., Watchaputi, K. et al. Elucidating a novel metabolic pathway for enhanced antimicrobial glycolipid biosurfactant production in the yeast Meyerozyma guilliermondii. Sci Rep 15, 18233 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03061-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03061-0

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Overcoming Candida albicans biofilm drug resistance via azole-sophorolipid synergy

Scientific Reports (2026)

-

Yeast-derived glycolipids disrupt Candida biofilm and inhibit expression of genes in cell adhesion

Scientific Reports (2025)