Abstract

This study investigates the benefits of gardening, exploring its relevance in an ageing population. A cross-sectional study was conducted with participants aged 30–98 years, who were given a questionnaire with four components for evaluation: sociodemographic characteristics, gardening status and reasons, physical health, and mental health. A total of 386 complete responses were obtained. Participants were categorised into two groups based on gardening frequency. One group included individuals who do not garden or garden occasionally, and the other group being those who garden daily (26.4%). The top reason for gardening was “happiness or satisfaction”, while “insufficient time” was the most cited reason for not gardening. Analysis showed that gardening daily was associated with 43% lower odds of developing poor health, defined as having either anxiety, health limitations, or both (OR = 0.57, 95%CI 0.32–0.99, p = 0.0499). There may also be an association between gardening daily and a reduction in the odds of developing anxiety and health limitations individually, although not statistically significant. Overall, this study shows that gardening daily was associated with better health outcomes, reducing anxiety and health limitations. This supports the promotion of gardening as an activity for healthy ageing.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Global ageing is an important social and medical demographic challenge faced today1, driving interest around the phenomenon of ageing well. The World Health Organisation defines healthy ageing as the “process of developing and maintaining functional ability that enables wellbeing in older age”2.

Gardening involves growing, cultivating and maintaining plants3, either at home or in community gardens. Gardening boasts physical and psychosocial health benefits3, especially in older adults4, showing potential in promoting healthy ageing. Physical benefits include consuming more balanced diets compared to non-gardeners5, and reduced risk of heart disease and cancer6. In the psychosocial context, gardening was found to encourage mental stimulation and psychosocial wellbeing6. Gardening also fosters social connections, reducing feelings of isolation and loneliness7. Self-reported mental and physical health benefits are observed to be proportional to the frequency of gardening activities, peaking at daily gardening8.

In contrast, some literature challenge the positive association between gardening and healthy ageing. For example, one study found no significant differences in physical, emotional, and mental health between gardeners and non-gardeners9. Moreover, certain limitations of gardening can even negatively impact healthy ageing. Age-related frailty may hinder older adults from maintaining their gardens, potentially leading to neglect. This neglect may increase feelings of anxiety and a heightened sense of burden, thereby adversely affecting psychosocial health10.

There is limited literature on home-based gardening among community-dwelling adults across a life course. Firstly, local studies mainly investigated other factors such as therapeutic gardens11 and park use12 instead of home-based gardening. And while these therapeutic gardens and parks were positively associated with mental health, associations with physical health were not investigated as much. Secondly, a separate study on horticultural therapy did not find significant improvements in physical and mental health between interventional and control groups13. It is worth noting that horticultural therapy was a structured gardening programme rather than informal gardening within the home environment, which is our topic of interest. Lastly, most research on gardening benefits were performed outside of Singapore, where gardening practices and research scopes may differ, reducing their relevance locally. Thus, there is a research gap on the association between daily gardening and healthy ageing in Singapore.

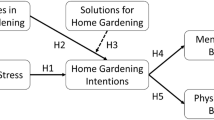

This study aims to examine the association between daily gardening and healthy ageing in Singapore, especially amongst community-dwelling older adults. Healthy ageing is assessed using two dimensions, physical health (presence of any health limitations) and mental health (level of participants’ anxiety). The study seeks to determine the prevalence of gardening among participants, identify the key factors influencing their decisions to engage in or refrain from gardening, and evaluate the association between gardening and participants’ physical and mental health outcomes.

Methods

Study design

This was a cross-sectional survey conducted in Sengkang, a residential town in northeastern region of Singapore. The study aims to better understand the associations between daily gardening and healthy ageing. Conducted from 15th July 2024 to 31st July 2024, the self-administered Qualtrics questionnaire was performed door-to-door. Eligible participants were Singaporeans and Permanent Residents (living in Singapore for more than 6 months in the past year), aged 30–98 years old, staying in Sengkang.

While this study is on healthy ageing, a concept more related with older adults defined by the World Health Organisation to be aged 60 and above, a broader age range was selected. This is to better understand the broader life-course contributions of daily gardening to functional health, exploring how the activity could potentially impact young and mid-life adults as well. Furthermore, our door-to-door recruitment approach also reflected the community’s actual age distribution of gardeners, with many participants starting gardening much earlier in life and continuing into older age. Nonetheless, stratified selected analyses by age groups (below and above the mean age of 53 years) can be found in Online Appendix Tables III–VIII for a better interpretation of age-specific patterns on outcomes.

Letters of Invitation were distributed 2 weeks prior to inform residents about this research study. Participants’ consent was collected before completing the survey. The questionnaire was administered in English and Mandarin to facilitate participants’ understanding of the survey.

With reference to data published in the 2020 Census of Population Survey by the Singapore Department of Statistics (Online Appendix Table I)14, HDB blocks in Sengkang were selected with the goal of surveying the general population living in different flat types14. An overview of the HDB blocks recruited can be found under Online Appendix Figure I.

To ensure representation across the different socioeconomic strata, participants were recruited through purposive sampling. In our area of study, there were only 2 blocks with the smaller 2-room units (Online Appendix Table II), typically occupied by lower-income or older adults living alone14. For adequate coverage of this demographic, these blocks with smaller 2-room units were surveyed first. Following this, blocks with larger 3-, 4-, 5-room, and executive units were selected. HDB flat types in each block were identified using HDB Map Services15. This ensured that participants from various flat types were represented in the study.

When eligible participants were unavailable, another visit was attempted on another day to reduce non-response bias. After randomly selecting the first unit, systematic sampling was utilised, where every alternate unit was surveyed.

Clinical trial number: not applicable.

Sample size calculation

We planned a study of independent cases and controls with one non-gardener per gardener, following previous research that states the prevalence of gardening in Singapore was 50%16. Prior data also indicated that the probability of anxiety among non-gardeners was 65%17. If the true probability of anxiety among gardeners was 46%17, we would need to study 106 gardeners and 106 non-gardeners to reject the null hypothesis with a power of 80%. The Type I error was 5%. We inflated the sample by 25% to account for possible attrition, aiming to complete a total of 283 surveys. Given higher-than-expected response rates, we collected 386 complete responses.

Variables

Participants were surveyed to collect data on different variables. The official questionnaire can be found in Online Appendix Table IX.

Key exposure

Regarding gardening habits, participants were asked if they garden, and the reasons for their choice. Gardeners were further queried about the type of gardening activities and the number of days spent each week gardening.

Gardening status was analysed as a binary exposure. Individuals who do not garden or garden weekly or monthly were grouped as non-daily gardeners, with daily gardeners in a separate group. As daily gardening constitutes a substantially higher level of physical activity and engagement compared to occasional or non-gardening, it is likely to lead to measurable differences in health outcomes.

Outcomes

Health limitations and mental health were the outcomes of interest, specific domains aligning with the WHO healthy ageing framework, specifically functional ability and intrinsic capacity respectively.

To assess health limitations, participants were asked “How much does your health limit you in walking several blocks or carrying groceries?”. We assessed self-declared health limitations as a binary, with mild to severe limitations grouped together.

For mental health, participants were assessed on their anxiety levels based on the Generalised Anxiety Disorder 7-item (GAD-7) scoring, a scoring that is utilised by HealthHub Singapore18. Responses for anxiety were categorised into mild (5–9), moderate (10–14), and severe (15–21) anxiety based on the GAD-7 cutoffs. Similarly, the outcome was analysed as a binary variable, with anxiety defined as having at least mild anxiety.

Other variables and confounders

Demographic data such as age, gender, ethnicity, marital status, HDB flat type, highest education qualification, employment status, and monthly income were collected for analysis and evaluation of confounders. Lifestyle behaviours and chronic health conditions, such as diabetes, hypertension, and hyperlipidaemia were also enquired on.

Quantitative continuous variables such as age were not grouped and were directly analysed as continuous variables. Sensitivity analysis on outcomes were stratified by age groups (below and above the mean age of 53 years) in Online Appendix Tables III–VIII.

Some categorical variables were regrouped. Education level was analysed as a binary variable, with higher education referring to a minimum of A-Level or tertiary education. Income and working status were categorised into not working, working with income less than $5000, and working with income more than $5000. Variables for lifestyle behaviours were mainly analysed as binaries, namely participation in community activities (yes/no), smoking (current/ex-smokers vs. non-smokers), alcohol consumption (current vs. non/ex-drinkers), and having an ideal sleep duration (7–8 h vs. others).

Data management

Missing data included 3 entries for education level, 8 for age, and 13 for monthly income. 18 responses with 2 or more missing data were removed. Responses with one missing data were retained using median imputation for categorical variables like monthly income.

Statistical methods

Data collected was downloaded from Qualtrics and analysed using RStudio (version 4.4.1). Categorical and continuous variables were analysed for both exposure and outcomes of interest.

The association between respondents’ demographics, lifestyle behaviours, and gardening status was investigated using the chi-square test, as all were categorical variables.

Multivariable logistic regression was used to investigate the association between gardening status and three binary outcomes: anxiety, health limitations, and poor health. Five regression models were used, unadjusted and four stepwise models to adjust for the confounding effects of demographic factors, socioeconomic status, lifestyle behaviours, and chronic diseases. The significance level was set at 5%.

Results

Participant flow

The study area comprised 4023 potentially eligible households, all of whom received Letters of Invitation 2 weeks prior to our survey. Over the data collection period, 2576 doors were knocked, where 410 households opened their doors and were examined for eligibility. In total, 404 households met the inclusion criteria and were surveyed (Fig. 1). After data collection completion, there were 18 non-completers, whose responses contained two or more missing data. Hence, the final sample size used for data analysis was 386, with an overall response rate of 15.0%.

Sociodemographic characteristics

Of the 386 respondents, 26.4% garden daily (Table 1). These respondents were more likely to be older (mean = 56.9 vs. 51.2, p = 0.001) and male (70.6% vs. 58.8%, p = 0.047). They were more likely to live in bigger 4-room, 5-room, or executive flats than in smaller 1- to 3-room flats (79.4% vs. 63.7%, p = 0.013) and participate in community activities (40.2% vs. 28.2%, p = 0.034). Lastly, they were more likely not working (57.8% vs. 40.8%, p = 0.012), or less likely to have a high education (47.1% vs. 59.9%, p = 0.034).

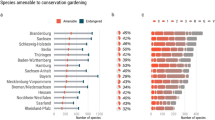

Reasons for gardening and for not gardening

Among respondents who garden daily, the most common reason for gardening was happiness or satisfaction (66.7%), followed by relaxation (52.9%) (Fig. 2). Among respondents who do not garden, insufficient time (30.3%), lack of interest (29.9%), and not having enough space (21.8%) were most cited for not gardening (Fig. 3).

Anxiety

After adjusting for confounders, gardening daily was associated with a 19% reduction in the odds of having anxiety, though not statistically significant (OR = 0.81, CI = 0.41–1.55, p = 0.54) (Table 2). Age was inversely associated with anxiety: every unit increase in age was associated with a 6% reduction in the odds of being anxious (OR = 0.94, CI = 0.91–0.96, p < 0.001). Compared to working respondents with monthly incomes below $5000, those not working had 1.38 times higher odds of being anxious (OR = 2.38, CI = 1.17–4.97, p = 0.018). Respondents with diabetes had 2.51 times higher odds than those without diabetes of being anxious (OR = 3.51, CI = 1.49–8.43, p = 0.005) (Table 2).

When stratified by age group, daily gardening was associated with a 34% reduction in anxiety among individuals aged below the mean age of 53 years (OR = 0.66, 95% CI 0.27–1.54, P = 0.35; Online Appendix Table III), and a 44% increase among those aged 53 years and above (OR = 1.44, 95% CI 0.64–4.41, P = 0.52; Online Appendix Table IV), although neither association was statistically significant.

Health limitations

Similarly, gardening daily was associated with 41% (OR = 0.59, CI = 0.30–1.12, P = 0.116) reduction in the odds of developing health limitations, although not statistically significant (Table 3). Every unit increase in age was associated with a statistically significant 3% increase in the odds of having health limitations (OR = 1.03, CI = 1.00–1.06, P = 0.021). Compared to the working respondents with an income less than $5000, those not working had 1.39 times higher odds of having health limitations (OR = 2.39, CI = 1.18–5.00, P = 0.018).

When stratified by age group, daily gardening was not associated with having health limitations among individuals younger than 53 years (OR = 1.02, 95% CI 0.34–2.83, P = 0.97; Online Appendix Table V). In contrast, it was associated with a statistically significant 59% reduction in the odds of having health limitations among those aged 53 years and above (OR = 0.41, 95% CI 0.17–0.95, P = 0.042; Online Appendix Table VI).

Poor health

Daily gardening was associated with 43% lower odds of poor health outcomes (OR = 0.57, CI = 0.32–0.99, P = 0.0499) (Table 4), though the statistical significance was marginal. Compared to the reference group of those working with a monthly income less than $5000, those not working (no income) had significantly higher odds of having poor health (OR = 2.7, CI = 1.48–5.03, P = 0.001). Having diabetes and hypertension were also associated with significantly higher odds of having poor health. Respondents with diabetes had almost sevenfold the odds of having poor health (OR = 6.66, CI = 3.12–15.15, P < 0.001). For hypertension, respondents were twice as likely to have poor health (OR = 2.1, CI = 1.08–4.13, P = 0.03). As diabetes was associated with increased odds of being anxious (OR = 3.51, P = 0.004), and having either disease was significantly associated with higher odds of having health limitations (OR, diabetes = 5.75, P < 0.001; OR, hypertension = 2.9, P = 0.004), these conditions were also associated with poor health (Table 4).

When stratified by age group, daily gardening was associated with a 37% reduction in poor health among individuals younger than the mean age of 53 years (OR = 0.63, 95% CI 0.27–1.40, P = 0.266; Online Appendix Table VII), and a 48% decrease among those aged 53 years and above (OR = 0.52, 95% CI 0.22–1.18, P = 0.124; Online Appendix Table VIII). Neither association reached statistical significance.

Discussion

Key results and interpretations

In our door-to-door sample, 26.4% were daily gardeners. These respondents were more likely older, male, and living in 4-room, 5-room, or executive flats. They were more likely to not be working, have a lower education level, and participate in community activities. In another local study investigating associations between gardening and mental resilience, those who garden weekly had a median age group of 45–54 years. Those above 55 spent significantly more time gardening than younger respondents19. Another study found that respondents older than 40 have a higher gardening rate (58.7% vs. 42.6%), with more female than male gardeners (56% vs. 44%)20.

Among those who do not garden, insufficient time (30.3%) and interest (29.9%) were cited most as reasons. This is corroborated by our demographic data: non-gardeners tend to be working (59.2% vs. 40.8%) and may have difficulty finding time to cultivate a gardening habit or to care for their plants.

For respondents who garden daily, our regression analysis showed non-significant reductions of 19% and 41% in the odds of developing anxiety and health limitations, respectively. This association between anxiety and gardening daily correlates with our findings for reasons for gardening, where the most common reasons for gardening daily were relaxation, alongside happiness and satisfaction. When interpreted together, these findings suggest a possible correlation between mental well-being and gardening daily. In a UK-based study8, similarly, more than 50% of respondents gardened for “pleasure and enjoyment”, and almost 20% for “calm and relaxation”. Another local study19 found that weekly gardening time was correlated with mental resilience, including emotional regulation. These studies substantiate our findings, supporting the association between gardening and mental well-being.

In our study, when analysing anxiety and health limitations together, gardening daily was significantly associated with a 43% reduction in the odds of having poor health. Another UK-based study8 investigated the impact of gardening frequency on health benefits, measured by mental well-being, stress, and physical activity. Compared to non-gardeners, daily gardeners had 1.84 times higher well-being scores, 1.68 times lower stress scores, and were more physically active by 1.42 days per week. Evaluating these measures together suggests a strong association between gardening and general well-being, consistent with our findings.

While some studies, like one conducted in Scotland, suggest negligible differences in health between gardeners and non-gardeners, they may not consider gardening frequency or duration9. This could possibly account for their lack of association between gardening and health, as opposed to our study observations.

The absence of research focusing on daily gardening in Singapore is worth noting. Nevertheless, local studies repeatedly support the association between gardening and positive health outcomes, notably mental well-being. One such interventional study conducted a 24-session therapeutic horticulture program for seniors, reporting significant increases in happiness with significant reductions in anxiety and depression within the intervention group. There is no statistical difference compared to the control group13.

Additionally, effects of gardening on health outcomes were assessed in a scoping review of studies from countries including Taiwan and Japan7. 32% of these studies reported positive health outcomes, including reduced long-term conditions like diabetes. Another study found cardiovascular disease morbidity and mortality reduced in participants who gardened at moderate to high intensities at least four times weekly6. Hence, there is likely an association between gardening daily and health outcomes.

Lastly, when stratified by age group, our study’s association between daily gardening and healthy ageing appears more pronounced among older adults. This aligns with findings from a prior study in which allotment gardeners aged 62 years and above performed significantly or marginally better on all measures of health and well-being compared to age-matched non-gardening neighbours, while no significant differences were observed among younger individuals21.

Limitations

Firstly, cross-sectional studies have inherent temporal bias. Respondents were surveyed at a fixed point in time. Therefore, this study cannot reliably establish cause-and-effect relationships between exposure and outcomes, such as the protective effects of gardening daily against anxiety, health limitations, or poor health. Further studies, like a cohort study investigating the effect of gardening intensity on health, are recommended to reduce temporal bias.

Furthermore, as the survey was self-reported, recall bias affects the subjectivity of results. Healthier participants who attribute their good health status to their gardening habit may over-report weekly gardening frequency. Furthermore, it is difficult to quantify one’s anxiety accurately. Therefore, the GAD-7 scoring system was used to reduce subjectivity of self-reported anxiety levels. However, opting to explore physical functioning and mental health individually through scoring systems such as GAD-7 rather than an established healthy-ageing scale could be another limitation. Studies incorporating multi-dimensional healthy ageing indices may yield a more comprehensive assessment of participants in the future.

Non-response bias also exists, as some households did not open their doors. Those unwilling to participate in the study may differ from those who were, as non-respondents might be less interested in gardening. Nonetheless, there was an attempt at mitigating this bias, where households who did not open their doors were revisited on another day. Shorter questionnaires with close-ended questions may increase ease of completion, thus reducing non-response bias.

It must also be acknowledged that duration and type of gardening activity could potentially influence health outcomes. However, this study analysed gardening status as a binary exposure with daily gardeners and non-daily gardeners. We initially aimed to examine duration and type of gardening activity in greater detail (Online Appendix Table IX) but due to the relatively small sample size across the varying activity intensities and durations, we were unable to generate robust stratified analyses or dose–response models. Hence, we opted for a binary exposure so as to preserve statistical power and maintain analytical reliability. There is a need for future studies with larger and more granular datasets to examine gardening frequency, duration and activity types more precisely.

Lastly, with a broad age range of 30–98 years, this study did not fully explore age-related heterogeneity in the relationship between gardening and health outcomes. Efforts were made with age-stratified analyses, comparing the associations of daily gardening with anxiety, health limitations and poor health among younger and older gardeners. In general, daily gardening appears to have a protective effect in both age groups, though not statistically significant. This demonstrates a need for further studies that explore how the effects of gardening varies with different age groups.

Generalisability

This survey was conducted in Sengkang among public housing residents. Features of public housing in Sengkang, including the presence of community gardens, limited personal outdoor space, and shared common corridors, are likely to resemble other local public housing neighbourhoods. Likewise, with similar resident demographics to other local neighbourhoods, this study can be applied to most public housing areas. The use of purposive sampling in this study allowed for representation of these various resident demographics in Singapore. This sampling method ensured that lower-income and older single-person households, typically 2-room flats, also participated in the survey. These efforts help support the generalisability of findings.

However, public and private housing differ in both features and resident demographics. Private housing may feature fewer common social areas, more outdoor spaces, and the presence of personal gated property. Comparing public Housing Development Board (HDB) and private apartment residents’ highest qualifications as of 2020, HDB residents had a larger proportion without educational qualifications (11.2% vs. 1.09%) and a smaller percentage of university graduates (24.0% vs. 68.9%)14. This is likely to impact employability and earnings, causing variation in socioeconomic status. Hence, differences in resident demographics and housing features may limit generalisability of the survey across different housing types.

In summary, the study results may be generalisable among public housing residents, but not private housing residents. Nevertheless, 80% of Singapore’s residents stay in public housing22.

Conclusions

In conclusion, gardening daily is associated with better health outcomes, namely reducing the odds of anxiety and health limitation. Thus, gardening has the potential to be an activity that supports healthy ageing. Notable reasons for and against gardening have also been determined, which can be considered for further studies and public health policy. The low prevalence of gardening in the community marks it as an area of untapped potential, which may bring about significant public health benefits with a relatively small increase in prevalence.

Public health policymakers may consider promoting gardening as a tool to assist in healthy ageing, supplementing pre-existing community-based schemes. Policymakers can cater programmes and common practices based on people’s preferences and reasons for gardening, as explored in this study. These changes may lead to healthier ageing, which is essential in our rapidly ageing population. At the individual level, healthy ageing will allow for greater longevity, quality of life and independence. At the population level, it also reduces healthcare burden.

Further studies are recommended to determine the causal relationship that gardening daily has on healthy ageing outcomes and its extent. Changes to health promotion and prevention are not typically made based on the results of one study; therefore, this study can serve as a groundwork for future studies to expand on, potentially altering subsequent programmes.

Data availability

The dataset used during the current study is available from the corresponding author (Cynthia Chen [cynchen@nus.edu.sg]) upon reasonable request.

References

Rudnicka, E. et al. The World Health Organization (WHO) approach to healthy ageing. Maturitas https://doi.org/10.1016/j.maturitas.2020.05.018 (2020).

World Health Organisation (WHO). Healthy Ageing and Functional Ability 2020. (2020) Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/questions-and-answers/item/healthy-ageing-and-functional-ability.

Soga, M., Gaston, K. J. & Yamaura, Y. Gardening is beneficial for health: A meta-analysis. Prev. Med. Rep. 5, 92–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmedr.2016.11.007 (2017).

Wang, D. & MacMillan, T. The benefits of gardening for older adults: A systematic review of the literature. Activ. Adapt. Aging https://doi.org/10.1080/01924788.2013.784942 (2013).

Machida, D. Relationship between community or home gardening and health of the elderly: A web-based cross-sectional survey in Japan. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16081389 (2019).

Scott, T. L., Masser, B. M. & Pachana, N. A. Positive aging benefits of home and community gardening activities: Older adults report enhanced self-esteem, productive endeavours, social engagement and exercise. SAGE Open Med. https://doi.org/10.1177/2050312120901732 (2020).

Howarth, M., Brettle, A., Hardman, M. & Maden, M. What is the evidence for the impact of gardens and gardening on health and well-being: A scoping review and evidence-based logic model to guide healthcare strategy decision making on the use of gardening approaches as a social prescription. BMJ Open 10(7), e036923. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-036923 (2020).

Chalmin-Pui, L. S., Griffiths, A., Roe, J., Heaton, T. & Cameron, R. Why garden? – Attitudes and the perceived health benefits of home gardening. Cities 112, 103118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2021.103118 (2021).

Corley, J. et al. Home garden use during COVID-19: Associations with physical and mental wellbeing in older adults. J. Environ. Psychol. 73, 101545. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2020.101545 (2021).

Same, A., Lee, E. A., McNamara, B. & Rosenwax, L. The value of a gardening service for the frail elderly and people with a disability living in the community. Home Health Care Manag. Pract. 28, 256–261. https://doi.org/10.1177/1084822316652575 (2016).

Olszewska-Guizzo, A. et al. Therapeutic garden with contemplative features induces desirable changes in mood and brain activity in depressed adults. Front. Psychiatry https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.757056 (2022).

Park, S. H. et al. Daily Park use, physical activity, and psychological stress: A study using smartphone-based ecological momentary assessment amongst a multi-ethnic Asian cohort. Ment. Health Phys. Activ. 22, 100440. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mhpa.2022.100440 (2022).

Sia, A. et al. Nature-based activities improve the well-being of older adults. Sci. Rep. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-74828-w (2020).

Department of Statistics Singapore. SingStat Table Builder. (Department of Statistics Singapore, 2021). Available from: https://tablebuilder.singstat.gov.sg/table/CT/17476

Housing Development Board (HDB). HDB Map Services. (Housing Development Board, 2024). Available from: https://services2.hdb.gov.sg/web/fi10/emap.html

Song, S. et al. Home Gardening in Singapore: A feasibility study on the utilization of the vertical space of retrofitted high-rise public housing apartment buildings to increase urban vegetable self-sufficiency. Urban For. Urban Green. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2022.127755 (2022).

Gerdes, M. E. et al. Reducing anxiety with nature and gardening (rang): Evaluating the impacts of gardening and outdoor activities on anxiety among U.S. adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19(9), 5121. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19095121 (2022).

HealthHub. Dealing with Anxiety Disorder. (HealthHub, 2024). Available from: https://www.healthhub.sg/programmes/mindsg/caring-for-ourselves/dealing-with-anxiety-disorder-seniors#home

Sia, A. et al. The impact of gardening on mental resilience in times of stress: A case study during the COVID-19 pandemic in Singapore. Urban For. Urban Green. 68, 127448. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2021.127448 (2022).

Kosorić, V., Huang, H., Tablada, A., Lau, S.-K. & Tan, H. T. W. Survey on the social acceptance of the productive façade concept integrating photovoltaic and farming systems in high-rise public housing blocks in Singapore. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 111, 197–214. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2019.04.056 (2019).

Van Den Berg, A. E. et al. Allotment gardening and health: A comparative survey among allotment gardeners and their neighbours without an allotment. Environ. Health 9, 74. https://doi.org/10.1186/1476-069X-9-74 (2010).

Housing Development Board (HDB). HDB Map Services. (Housing Development Board, 2024). Available from: https://www.hdb.gov.sg/cs/infoweb/about-us/our-role/public-housing-a-singapore-icon

Acknowledgements

The research was supported by the Singapore Ministry of Health’s National Medical Research Council under its HPHSR Clinician Scientist Award (HCSAINV22jul-0005). The funder had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation or report writing.

Funding

The publication fee for this article was supported by Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, NUS. C.C. received support from the Singapore Ministry of Health’s National Medical Research Council under its HPHSR Clinician Scientist Award (HCSAINV22jul-0005, ID: MOH-001304).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.C. conceptualised and designed the research. S.K.M.C., C.W.J.C., and J.X.T. designed the questionnaire. D.S., E.S. and O.M. conducted the literature review. L.L. and X.W. accessed and verified the data. C.C. led Y.C., D.L., E.K. and S.G. in data analysis, interpretation and discussion of results. F.N.F. provided suggestions for the study design and interpreted the findings. A.V., A.C. and J.L. drafted the initial manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

was sought from the Departmental Ethics Review Committee (DERC), National University of Singapore (NUS) (Reference Number: SSHSPH-262; date of approval: 30 May 2024). All procedures were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations from DERC.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chwa, A., Vasudevan, A., Chan, S.K.M. et al. The association of daily gardening and healthy ageing in Singapore. Sci Rep 15, 20531 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03392-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03392-y