Abstract

Children are particularly vulnerable to the toxic effects of environmental exposure to heavy metals and metalloids (HM/MTs), which can impact red blood cells (RBCs) and platelets. This study aimed to evaluate the relationship between urinary levels of 19 HM/MTs and RBCs and platelet-related hematologic parameters in school-aged children residing in the central western state of Colima, Mexico. A cross-sectional pilot biomonitoring study was conducted, and 91 participants were enrolled. Multiple linear regression models were used to calculate regression coefficients (\(\:\beta\:\)) and 95% confidence intervals. After adjusting for sex, age, nutritional status, and locality of residence, tin was found to be negatively correlated with red cell distribution width (\(\:\beta\:\) = − 0.06, 95% CI − 0.11 to − 0.01). Additionally, each unit increase in urinary lead levels was associated with a 0.6% increase in mean corpuscular hemoglobin (\(\:\beta\:\) = 0.006, 95% CI 0.002 to 0.010). Similarly, each unit increase in tellurium levels was associated with a 55% increase in mean platelet volume (\(\:\beta\:\) = 0.55, 95% CI 0.08 to 1.02). These results suggest that environmental exposure to HM/MTs may be related to alterations in some of the evaluated hematologic parameters in the analyzed school-aged children. Further research, including larger sample sizes and longitudinal studies, is needed to reduce environmental health risks in this vulnerable population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Children are especially susceptible to the harmful health impacts of heavy metals and metalloids (HM/MTs) due to their developing bodies and immature detoxification systems1. Exposure to these potentially toxic elements can occur through various pathways, including ingestion, inhalation, and dermal contact2.

In the state of Colima, located in the central-western region of Mexico, a series of anthropogenic activities is carried out that have the potential to release HM/MTs into the environment. These potentially contaminating activities include a seaport3, a thermoelectric power plant4, cement production5, large-scale agriculture6, sugar cane processing7, and mining8.

The mechanisms of toxicity of most HM/MTs include the inactivation of specific enzymes, the production of reactive oxygen species, the disruption of antioxidant defenses, and an increase in oxidative stress9. Specifically within the hematopoietic system, these substances may directly harm bone marrow precursors by inhibiting enzymes related to cell division and maturation, impairing the transport of red blood cells (RBC) and causing immune-mediated cell destruction10. In addition, the induction of oxidative stress and inflammation mediated by HM/MTs may also produce impaired platelet function and production11.

Currently, there are limited data available on the relationship between HM/MTs exposure and RBC and platelet parameters in children, as well as the number of evaluated substances: lead12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19, mercury20,21,22, cadmium23,24, and arsenic23,25. To the best of our knowledge, only one published study has analyzed this relationship in the Mexican population, and only silicon, chromium, lead, titanium, vanadium, nickel, arsenic, manganese, and cadmium were assessed25.

This study aimed to evaluate the relationship between a large set of HM/MTs exposure and RBC (namely hemoglobin, hematocrit, mean corpuscular volume [MCV], mean corpuscular hemoglobin [MCH], and red cell distribution width [RDW]), and platelet-related parameters (platelet count and mean platelet volume [MPV]) in a group of children living in areas with HM/MTs contamination. The results aim to identify potential health risks correlated with HM/MTs exposure in this vulnerable population.

Methods

Study design

A cross-sectional pilot biomonitoring study was conducted in the second half of 2023, focusing on nine urban and rural areas within the state of Colima, Mexico. The selected sites included the metropolitan area of Colima-Villa de Álvarez (the state’s capital), along with Tecomán, Caleras, Armería, Manzanillo, Campos, Quesería, Paticajo, and Minatitlán. The selection of these specific locales was based on their pre-existing classification as high-risk environmental and health zones. This classification primarily reflected the prevalence of industrial, energy-related, or agricultural activities in these regions, indicating increased exposure to HM/MTs, as previously documented26.

Study population

This study included school-aged children (5 to 12 years old) who had resided in the study areas for at least five years, according to their parent or legal guardian. Children with chronic degenerative diseases were excluded to avoid confounding effects on hematological parameters and HM/MT-related responses, while those who had consumed processed foods within 24 h before to urine collection were excluded to prevent alterations in HM/MT levels or biomarker measurements27,28.

Participant selection followed a non-probabilistic, multistage approach. First, elementary schools located in high environmental risk areas were identified. Eligible children attending these schools were identified. Parents or legal guardians of eligible children received written invitations to an informative workshop that detailed the study’s purpose and procedures. Participation required written informed consent from the parents or legal guardians and assent from the child. All children who attended with a parent or guardian and met the eligibility criteria were enrolled.

Data collection

Anthropometric measurements were taken to assess the participants’ nutritional status. Z scores for body-mass-index-for-age (BMI) were calculated. The WHO’s Child Growth Standards were used29.

Laboratory methods

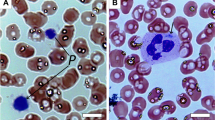

Blood samples (2 mL) were obtained via peripheral venipuncture and collected into sterile vacutainer tubes containing ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA). Subsequently, the blood samples were loaded into the automated hematology analyzer (DxH 900 Beckman Coulter, CA, USA) and processed according to the manufacturer’s specifications.

In this study, we assessed six parameters related to the red blood cell line: hemoglobin (g/dL), hematocrit (%), mean corpuscular volume (MCV, fL), mean corpuscular hemoglobin (MCH, pg), red cell distribution width (RDW, %), platelet count (cells/µL), and mean platelet volume (MPV, fL). Reference ranges for hematologic parameters in the Mexican population (stratified by sex) were used to compare the observed RBC and platelet-related measurements30.

First-morning void urine samples were collected in sterile containers (150 mL) and refrigerated at 4 °C until analysis. HM/MTs levels were quantified using inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS; NexION 300D, PerkinElmer, MA, USA) following a validated method (CINVESTAV, Mexico). All samples were analyzed in randomized duplicate, with inter-assay CVs < 10%. Accuracy was verified using INSPQ multi-element urine standards (QM-U-Q2104–115), yielding recoveries of 80–120%. Results were adjusted for specific gravity.

Statistical analysis

Summary statistics were computed. Spearman’s correlation coefficients (\(\:rho\)) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) were used to evaluate the relationship between the hematologic parameters and urinary HM/MTs levels. Children with urinary levels of any substance below the limit of detection (LOD) were excluded from the respective correlation and regression analyses. Missing values were excluded as follows: mercury and strontium (1 each); nickel, tin, and titanium (2 each); aluminum, cobalt, and copper (4 each); and arsenic (6).

Multiple generalized linear regression models estimated adjusted relationships (β coefficients with 95% CIs) between HM/MTs and erythrocyte parameters. All HM/MTs with significant Spearman correlations were included; one model was constructed per parameter (excluding MCV, which lacked significant correlations). Models were adjusted for sex, age, BMI-for-age, locality of residence, and relevant HM/MTs (selected via literature review and confounder assessment).

Model diagnostics revealed nonnormal distributions of studentized residuals for MCH (Model 5) and MPV (Model 6), which were log-transformed to achieve normality. No violations of linear regression assumptions (heteroscedasticity, multicollinearity) or influential outliers were detected.

Ethical considerations

All methods were performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from each parent or legal guardian and assent from the children. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee for Health Research under the Ministry of Health in the state where the study was conducted (approval CBCANCL2306023-PRONAII-17).

Results

Data from 91 school-aged children (46 girls [50.5%] and 45 boys [49.5%]) were analyzed. The mean age was 8.2 ± 1.5 years, with no significant difference observed between sexes (\(\:p\) = 0.582). The distribution of enrolled children per locality of residence was as follows: Armería, 9; Caleras, 9; Campos, 7; Colima – Villa de Álvarez, 10; Manzanillo, 11; Minatitlán, 4; Paticajo, 12; Quesería, 20; and Tecomán, 9.

According to the Z score, most of the studied children (\(\:n\) = 55/91) had a normal BMI-for-age. The prevalence of overweight or obesity was 37.4% (\(\:n\) = 34/91), and only 2 children (2.2%) were categorized as having a low BMI-for-age.

The evaluated event and exposure biomarkers are summarized in Table 1. The 93.4% (\(\:n\) = 85/91) of enrolled children had hemoglobin levels within the expected range (females, 12.2–16.1 g/dL; males, 12.5–16.0 g/dL), and prevalence of low levels was 5.5% (\(\:n\) = 5/91).

Biomarker results are summarized in Table 1. Hemoglobin levels were normal (females: 12.2–16.1 g/dL; males: 12.5–16.0 g/dL) in 93.4% (\(\:n\) = 85/91) of children, with low levels in 5.5% (\(\:n\) = 5/91). Hematocrit was normal (37.1–48.0% for both sexes) in 84.6% (\(\:n\) = 77/91), with one case (1.1%) of hemoconcentration ( > 48.0%). MCV was normal (females: 79.0–92.9 fL; males: 78.7–91.2 fL) in 80.2% (\(\:n\) = 73/91) and low in 19.8% (\(\:n\) = 17/91), with no high MCV cases. MCH was normal in only one female participant (31.0–34.4 pg), while 98.9% (\(\:n\) = 90/91) showed subnormal values (females: < 31.0 pg; males: < 31.6 pg). All children had normal RDW (females: 12.0–17.7%; males: 11.8–17.6%).

Thrombocytopenia (platelet count < 147,000/µL in females; < 167,000/µL in males) was observed in 3 children (3.3%), while thrombocytosis (> 431,000/µL in females; > 384,000/µL in males) was found in 15 children (16.5%). Nearly one-quarter of participants (23.1%, \(\:n\) = 21/91) showed elevated mean platelet volume (MPV > 10.0 fL), with the remainder (76.9%, \(\:n\) = 70/91) within normal range (6.8–10.0 fL).

Ten HM/MTs (barium, cadmium, cesium, iron, lead, lithium, molybdenum, selenium, tellurium, and zinc) were detected in all analyzed children. Detectable levels of mercury (LOD ≤ 0.079 ng/mL) and strontium (LOD ≤ 0.529 ng/mL) were found in 98.9% (\(\:n\) = 90/91) of participants. Nickel (LOD ≤ 0.043 ng/mL), tin (LOD ≤ 0.131 ng/mL), and titanium (LOD ≤ 0.174 ng/mL) were present in 97.8% (\(\:n\) = 89/91) of children. Aluminum (LOD ≤ 0.045 ng/mL), cobalt (LOD ≤ 0.053 ng/mL), and copper (LOD ≤ 0.112 ng/mL) were detectable in 95.6% (\(\:n\) = 87/91) of participants. Arsenic (LOD ≤ 0.041 ng/mL) was measurable in 93.4% (n = 85/91) of children.

Our analysis identified several significant relationships between urinary metal concentrations and erythrocyte parameters (Table 2). Copper levels correlated inversely with hematocrit (\(\:rho\) = − 0.22, 95% CI − 0.43 to − 0.01, \(\:p\) = 0.037), suggesting that higher copper exposure relates to decreased hematocrit values. Lead exposure showed the most complex pattern, with significant negative correlations for both hemoglobin (\(\:rho\) = − 0.21, 95% CI − 0.41 to − 0.01, \(\:p\) = 0.048) and hematocrit (\(\:rho\) = − 0.24, 95% CI − 0.44 to − 0.05, \(\:p\) = 0.021), while positively correlating with MCH (\(\:rho\) = 0.21, 95% CI 0.01 to 0.42, \(\:p\) = 0.043). These findings suggest lead’s effects may relate differently to various hematological indices.

Mercury concentrations correlated negatively with hemoglobin levels (\(\:rho\) = − 0.23, 95% CI − 0.43 to − 0.04, \(\:p\) = 0.028). Strontium showed the strongest positive correlation, with its levels relating most strongly to increased MCH values (\(\:rho\) = 0.28, 95% CI 0.07 to 0.50, \(\:p\) = 0.007). For tin, we observed a significant negative correlation with RDW (\(\:rho\) = − 0.22, 95% CI − 0.44 to − 0.01, \(\:p\) = 0.033), though the clinical relevance of this relationship warrants further investigation.

The correlation analysis revealed significant correlations between HM/MTs and platelet parameters (Table 3). Barium showed a positive correlation with platelet count (\(\:rho\) = 0.24, 95% CI 0.04 to 0.44, \(\:p\) = 0.021), while lead exhibited an inverse relationship (\(\:rho\) = − 0.22, 95% CI − 0.41 to − 0.02, \(\:p\) = 0.040). Furthermore, tellurium levels correlated positively with MPV (\(\:rho\) = 0.31, 95% CI 0.12 to 0.49, \(\:p\) = 0.003), indicating a potential relationship between tellurium exposure and platelet size.

The multiple linear regression results for Models 1–4 (analyzing hemoglobin, hematocrit, platelet count, and RDW, respectively) are presented in Table 4. After adjusting for the metals included in each model, age, sex, nutritional status, and residential location, only Model 4 (RDW) demonstrated a statistically significant linear association. This model revealed an inverse relationship between tin levels and RDW (\(\:\beta\:\) = − 0.06, 95% CI − 0.11 to − 0.01, \(\:p\) = 0.038), indicating that higher tin concentrations correlated with lower RDW values. All observed RDW measurements fell within normal physiological ranges despite this association.

The log-transformed regression analysis (Table 5) revealed two significant dose-response relationships. First, each unit increase in urinary lead concentration was associated with a 0.6% increase in MCH (Model 4: \(\:\beta\:\) = 0.006, 95% CI 0.002 to 0.010, \(\:p\) = 0.001). Tellurium showed a robust positive relationship with MPV, where each unit increment in tellurium levels corresponded to a 55.0% elevation in the blood biomarker (\(\:\beta\:\) = 0.55, 95% CI 0.08 to 1.02, \(\:p\) = 0.023).

Discussion

Our results suggest that environmental exposure to HM/MTs may be related to alterations in some of the evaluated RBC and platelet-related parameters in the analyzed school-aged children. Furthermore, this relationship appears to be independent of sex, age, nutritional status (as indicated by BMI-for-age), and locality of residence. However, it is important to consider the methodological limitations inherent in the study design when interpreting our findings. Supplementary Figure S1 presents the directed acyclic graph (DAG) illustrating the hypothesized causal pathways between environmental HM/MT exposure and hematologic outcomes in the study population.

The inverse association between urinary tin levels and RDW in children may arise from tin’s capacity to reduce oxidative stress, a key contributor to erythrocyte size variability. Certain tin compounds exhibit antioxidant properties in vitro31. However, human data remain limited, and the underlying mechanisms, if confirmed, require further clarification.

The RDW indicates a variation in erythrocyte size, which implies that some red blood cells have abnormal sizes despite having other normal erythrocyte indices. Although all children had normal RDW, this parameter is considered an indicator of impaired iron transport32. In the multiple regression analysis, we observed a negative relationship between urinary tin levels and RWD (\(\:\beta\:\) = − 0.06, 95% CI − 0.11 to − 0.01, \(\:p\) = 0.038) (Table 4). To the best of our knowledge, there are not published studies evaluating the potential effect of environmental tin exposure on RDW in children.

Lead levels in our study exhibited a positive linear relationship with the log-transformed MCH. Specifically, for each unit increase in urinary levels of this heavy metal, the hematologic parameter increased by 0.6% (\(\:\beta\:\) = 0.006, 95% CI 0.002 to 0.010, \(\:p\) = 0.001) (Table 5). Increased MCH by lead exposure have been described on animal models33. A significant negative relationship has been documented among Chinese children34,35,36. We consider that this discrepancy may result, at least partially, from high lead concentrations in the Chinese population. The lead blood levels in these studies were as high as 10 µg/L, while the highest concentration in our population was 3.2 µg/L.

About 99% of lead is within erythrocytes37; thus, plasma levels are relatively low in comparison, making it likely that urinary lead reflects plasma concentrations38. It’s important to note that the observed lead levels in our study sample were lower than those previously documented in unexposed populations (80 ng/mL)39.

Discrepancies in the relationship between lead levels and mean corpuscular hemoglobin (MCH) could arise from differences in the timing and duration of exposure captured by these biomarkers. Nevertheless, it is remarkable that despite low concentrations, effects on hematological parameters were found. In our model, hemoglobin was not significantly affected by lead (Model 1), but MCH was not measured directly; it was calculated based on the hemoglobin value, which was altered in nearly 7% of enrolled children. Therefore, in our population, lead seems to be related to hemoglobin alterations.

We observed a consistent positive relationship between lead levels and MCH in our study population, with each unit increase in urinary lead corresponding to a 0.6% rise in log-transformed MCH values (\(\:\beta\:\) = 0.006, 95% CI 0.002–0.010, \(\:p\) = 0.001). This finding presents an interesting paradox when viewed against existing literature. While animal models similarly report lead-induced increases in MCH33, human studies from Chinese populations have documented the opposite effect, a significant inverse relationship between lead exposure and MCH34,35,36.

The resolution to this apparent contradiction likely lies in several key factors. Most notably, the Chinese cohorts exhibited higher lead exposure levels (up to 10 µg/dL) compared to our population’s maximum of 3.2 µg/dL. This exposure gradient suggests a potential threshold effect, where lower lead concentrations may stimulate erythropoietic activity while higher levels overwhelm compensatory mechanisms and impair hemoglobin synthesis through inhibition of δ-aminolevulinic acid dehydratase in the heme biosynthesis pathway40.

The biological interpretation of these findings requires careful consideration of lead’s pharmacokinetics. With approximately 99% of bodily lead sequestered in erythrocytes37, urinary measurements primarily reflect the small plasma fraction41. Interestingly, even our highest recorded levels (below 80 ng/mL39) fell substantially lower than those reported in unexposed populations, making the detectable hematological effects noteworthy.

Methodological considerations further inform these observations. While we found no direct correlations between lead and total hemoglobin levels, the significant MCH findings suggest lead influence hemoglobinization processes independently of gross hemoglobin concentration. This underscores the importance of examining multiple hematologic parameters when assessing HM/MTs exposure effects.

The concentration of tellurium exhibits a positive linear relationship with mean platelet volume (MPV). An increase in MPV is an indicator of thrombocytopenia, which aligns with previous studies. It has been described that tellurium acts as an inhibitor of heparin binding to active sites by forming covalent bonds with sulfhydryl groups. Additionally, it affects the enzyme squalene monooxygenase42. Moreover, evidence exists of platelet aggregation induction by Tellurium Quantum Dots in both no-flow and underflow conditions43. These findings suggest that tellurium could inhibit the action of enzymes involved in platelet aggregation44.

A recently published study conducted by Zhu and colleagues documented a positive association between MPV and urinary levels of iron, zinc, cadmium, antimony, and lead. Additionally, in the same study, a mediation analysis identified that MPV was associated with a 10-year risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease45.

One major strength of this study is the implementation of multivariate analyses, as most published studies have conducted bivariate evaluations46. The presented estimators were adjusted for sex, age, and place of residence, which are potential sources of epidemiological confounding in this type of studies47,48.

The inherent limitations of a cross-sectional study design should be carefully considered when interpreting our findings. A key limitation of this study is the potential constraints of the statistical model. While adjustments were made for sex, age, BMI, and residence, other confounders like diet, iron intake, anemia history, inflammatory status, and additional environmental exposures (e.g., air and water pollution) were not included. The adjusted determination coefficient (R²), with a median value of 0.121, suggests that the model explains a modest proportion of the variability in the hematological parameters, highlighting the potential influence of unaccounted confounders. Future research should incorporate more potential confounders to test the robustness of the model.

Additionally, children with HM/MT levels below the LOD were excluded from the analysis. We chose exclusion over imputation because our aim was not to estimate the mean or median levels. This decision was further justified by the observation that the excluded children were randomly distributed across key variables, including the evaluated HM/MTs, locality of residence, age, and sex, suggesting that their exclusion did not systematically bias the results.

Moreover, we utilized a self-recruitment strategy within schools where eligible children received education, potentially leading to a sample of girls and boys that may not fully represent the source population. As participation was voluntary, our sample may overrepresent children from families with greater health awareness or socioeconomic advantage, a potential “healthy volunteer” bias. While we lacked individual-level socioeconomic data, the participating schools served mixed-income neighborhoods, providing some population diversity. However, we acknowledge that families facing greater socioeconomic deprivation may have been less likely to participate. This could lead to underestimation of true exposure-effect relationships if more highly exposed children were systematically excluded.

The selection of urine over other biological fluids (e.g., blood) for assessing exposure to HMs/MTs depends on the toxicokinetic properties of each element49. In this study, we focused solely on urine samples, as they are particularly suitable for quantifying xenobiotics with rapid excretion (e.g., tin, lead, and tellurium) and provide a reliable indicator of recent exposure50. However, urine samples are not the first choice for quantifying essential elements (e.g., copper, zinc, or iron) or when estimating long-term body burden, as blood or serum biomarkers better reflect systemic accumulation51.

Nonetheless, our study may offer valuable insights into the relationship between HM/MTs exposure and hematologic biomarkers related to RBCs and platelets in school-aged children. This highlights the necessity for further research to validate and build upon our results.

Conclusion

The results suggest that environmental exposure to HM/MTs¿ may influence certain hematologic parameters in school-aged children. To better understand and mitigate these environmental health risks in this vulnerable population, future studies should employ larger sample sizes and longitudinal designs. These approaches would strengthen our understanding of HM/MT exposure effects on hematologic outcomes, ultimately informing targeted interventions and preventive strategies.

Data availability

Data requests should be sent to the corresponding author and will be reviewed by lead investigators and the funding council.

References

Bair, E. C. A narrative review of toxic heavy metal content of infant and toddler foods and evaluation of united States policy. Front. Nutr. 9, 919913 (2022).

Zhang, H. et al. Multiple exposure pathways and health risk assessment of heavy metal(loid)s for children living in fourth-tier cities in Hubei Province. Environ. Int. 129, 517–524 (2019).

Hossain, M. B. et al. Contamination and ecological risk assessment of metal (loid) s in sediments of two major seaports along Bay of Bengal Coast. Sustainability 14 (19), 12733 (2022).

Kapoor, D. & Singh, M. P. Heavy metal contamination in water and its possible sources, in Heavy metals in the environment. Elsevier. pp. 179–189. (2021).

Olatunde, K. et al. Distribution and ecological risk assessment of heavy metals in soils around a major cement factory, Ibese, Nigeria. Sci. Afr. 9, e00496 (2020).

Alengebawy, A. et al. Heavy metals and pesticides toxicity in agricultural soil and plants: ecological risks and human health implications. Toxics 9 (3), 42 (2021).

Castro-Gerardo, G. A. et al. Concentration and distribution of heavy metals in Ash emitted by the sugar factory La Gloria, Veracruz, Mexico. Revista Int. De Contaminación Ambiental. 36 (2), 275–285 (2020).

Azamar-Alonso, A. & Téllez-Ramírez, I. Introducción, in Minería en México: Panorama social, ambiental y económico, A. Azamar-Alonso and I. Téllez-Ramírez, Editors. 2022, Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana: Ciudad de México. pp. 13–23.

Balali-Mood, M. et al. Toxic mechanisms of five heavy metals: Mercury, lead, chromium, cadmium, and arsenic. Front. Pharmacol. 12, 643972 (2021).

Anka, A. U. et al. Potential mechanisms of some selected heavy metals in the induction of inflammation and autoimmunity. Eur. J. Inflamm. 20, 1721727X221122719 (2022).

Sani, A. et al. Heavy metals mixture affects the blood and antioxidant defense system of mice. J. Hazard. Mater. Adv. 11, 100340 (2023).

Guo, Y. et al. Iron status in relation to Low-Level lead exposure in a large population of children aged 0–5 years. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 199 (4), 1253–1258 (2021).

Hegazy, A. A. et al. Relation between anemia and blood levels of lead, copper, zinc and iron among children. BMC Res. Notes. 3, 133 (2010).

Kutllovci-Zogaj, D. et al. Correlation between blood lead level and hemoglobin level in Mitrovica children. Med. Arch. 68 (5), 324–328 (2014).

Liu, J. et al. Low blood lead levels and hemoglobin concentrations in preschool children in China. Toxicol. Environ. Chem. 94 (2), 423–426 (2012).

Mitra, A. K., Ahua, E. & Saha, P. K. Prevalence of and risk factors for lead poisoning in young children in Bangladesh. J. Health Popul. Nutr. 30 (4), 404 (2012).

Ngueta, G. Assessing the influence of age and ethnicity on the association between iron status and lead concentration in blood: results from the Canadian health measures survey (2007–2011). Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 171, 301–307 (2016).

Rondó, P. H. C. et al. Iron deficiency anaemia and blood lead concentrations in Brazilian children. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 105 (9), 525–530 (2011).

Zolaly, M. A. et al. Association between blood lead levels and environmental exposure among Saudi schoolchildren in certain districts of Al-Madinah. Int. J. Gen. Med., : pp. 355–364. (2012).

Kempton, J. W. et al. An assessment of health outcomes and Methylmercury exposure in Munduruku Indigenous women of childbearing age and their children under 2 years old. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 18 (19), 10091 (2021).

Manjarres-Suarez, A. & Olivero-Verbel, J. Hematological parameters and hair mercury levels in adolescents from the Colombian Caribbean. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 27 (12), 14216–14227 (2020).

Weinhouse, C. et al. Hair mercury level is associated with anemia and micronutrient status in children living near artisanal and small-scale gold mining in the Peruvian Amazon. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 97 (6), 1886 (2017).

Kordas, K. et al. Prevalence and predictors of exposure to multiple metals in preschool children from Montevideo. Uruguay Sci. Total Environ. 408 (20), 4488–4494 (2010).

Nassef, Y. E. et al. Trace elements, heavy metals and vitamins in Egyptian school children with iron deficiency anemia. J. Pediatr. Biochem. 4 (3), 171–179 (2014).

Lopez-Rodriguez, G. et al. Blood toxic metals and hemoglobin levels in Mexican children. Environ. Monit. Assess. 189 (4), 179 (2017).

Mendoza-Cano, O. et al. Metal Concentrations and KIM-1 Levels in school-aged Children: a Crosssectional Study (Sci Rep [Article in press], 2024).

Shenkut, M. et al. Assessment of the hematological profile of children with chronic kidney disease on follow-up at St. Paul’s hospital millennium medical college and Tikur Anbessa specialized hospital in addis Ababa, Ethiopia. BMC Nephrol. 25 (1), 44 (2024).

Scutarasu, E. C. & Trinca, L. C. Heavy metals in foods and beverages: global situation, health risks and reduction methods. Foods, 12(18). (2023).

World Health Organization. Chilld growth standards: Body mass inder-for-age (BMI-for-age). Available at: (2024). https://www.who.int/toolkits/child-growth-standards/standards/body-mass-index-for-age-bmi-for-age(accessed on Jun 25,).

Piedra, P. D. et al. Determinación de Los Intervalos de referencia de biometría hemática En Población Mexicana. Revista Mexicana De Patología Clínica Y Med. De Laboratorio. 59 (4), 243–250 (2012).

Hadi, A. G., Hassen, T. F. & Mahdi, I. J. Synthesis, characterization, and antioxidant material activities of organotin (IV) carboxylates with tin-para methoxy benzoic acid.Mater. Today: Proc., 49: pp. 2797–2801. (2022).

Animasahun, B. A. & Itiola, A. Y. Iron deficiency and iron deficiency anaemia in children: physiology, epidemiology, aetiology, clinical effects, laboratory diagnosis and treatment: literature review. J. Xiangya Med., 6. (2021).

Manuhara, Y. S. W. et al. The comparison toxicity effects of lead and cadmium exposure on hematological parameters and organs of mice. Ecol. Environ. Conserv. 26 (4), 1842–1846 (2020).

Kuang, W. et al. Adverse health effects of lead exposure on physical growth, erythrocyte parameters and school performances for school-aged children in Eastern China. Environ. Int. 145, 106130 (2020).

Li, C. et al. Dose-response relationship between blood lead levels and hematological parameters in children from central China. Environ. Res. 164, 501–506 (2018).

Dai, Y. et al. Elevated lead levels and changes in blood morphology and erythrocyte CR1 in preschool children from an e-waste area. Sci. Total Environ. 592, 51–59 (2017).

Collin, M. S. et al. Bioaccumulation of lead (Pb) and its effects on human: A review. J. Hazard. Mater. Adv. 7, 100094 (2022).

Sallsten, G. et al. Variability of lead in urine and blood in healthy individuals. Environ. Res. 212 (Pt C), 113412–p (2022).

Choudhury, T. R. et al. Status of metals in serum and urine samples of chronic kidney disease patients in a rural area of Bangladesh: An observational study. Heliyon, 7(11). (2021).

La-Llave-León, O. et al. Association between blood lead levels and delta-aminolevulinic acid dehydratase in pregnant women. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 14 (4), 432 (2017).

Sallsten, G. et al. Variability of lead in urine and blood in healthy individuals. Environ. Res. 212, 113412 (2022).

Wagner-Recio, M., Toews, A. D. & Morell, P. Tellurium blocks cholesterol synthesis by inhibiting squalene metabolism: Preferential vulnerability to this metabolic block leads to peripheral nervous system demyelination. J. Neurochem. 57 (6), 1891–1901 (1991).

Samuel, S. P. et al. CdTe quantum Dots induce activation of human platelets: Implications for nanoparticle hemocompatibility. Int. J. Nanomed. 10, 2723–2734 (2015).

Nyska, A. et al. Toxicity study in rats of a tellurium based Immunomodulating drug, AS-101: A potential drug for AIDS and cancer patients. Arch. Toxicol. 63, 386–393 (1989).

Zhu, C. et al. Mean platelet volume mediated the relationships between heavy metals exposure and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk: A community-based study. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 27 (8), 830–839 (2020).

Capitao, C. et al. Exposure to heavy metals and red blood cell parameters in children: A systematic review of observational studies. Front. Pediatr. 10, 921239 (2022).

Gligoroska, J. P. et al. Red blood cell variables in children and adolescents regarding the age and sex. Iran. J. Public. Health. 48 (4), 704 (2019).

Kwon, J. Y. et al. Association between levels of exposure to heavy metals and renal function indicators of residents in environmentally vulnerable areas. Sci. Rep. 13 (1), 2856 (2023).

Fairbrother, A. et al. Framework for metals risk assessment. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 68 (2), 145–227 (2007).

Martinez-Morata, I. et al. A State-of-the-Science review on metal biomarkers. Curr. Environ. Health Rep. 10 (3), 215–249 (2023).

Wallace, M. A., Kormos, T. M. & Pleil, J. D. Blood-borne biomarkers and bioindicators for linking exposure to health effects in environmental health science. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health B Crit. Rev. 19 (8), 380–409 (2016).

Acknowledgements

We extend our gratitude to the Ministry of Science, Humanities, Technology and Innovation (SECIHTI) of Mexico for their support through the National Strategic Programs (PRONACES), which facilitated the execution of this research. The founding source played no role in the design of the study, data collection, analysis, interpretation, drafting of the report, or decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

OMC conceived and designed the study. Data collection was conducted by MRS, IEGC, AACdlC, MFRG, JAAB, HBCA, ALQM, MAMP, PRA, AGHL, and JMUR. The data analysis was performed by VBG and EMZ. The results were interpreted by OMC, VBG, and EMZ. The first draft of the manuscript was written by OMC, VBG, and EMZ. MRS, IEGC, AACdlC, MFRG, JAAB, HBCA, ALQM, MAMP, PRA, AGHL, and JMUR, reviewed and edited the final manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The study protocol underwent a thorough review and received approval from the Committee of Ethics in Health Research of the Ministry of Health in the state where the study was conducted (approval CBCANCL2306023-PRONAII-17).

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mendoza-Cano, O., Ríos‐Silva, M., Gonzalez-Curiel, I.E. et al. Hemoglobin and mean platelet volume abnormalities in children exposed to heavy metals and metalloids in a pilot biomonitoring study. Sci Rep 15, 29000 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03410-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03410-z