Abstract

Kombucha tea is a fermented tea that produced by acetic acid bacteria and yeast. In this study, the kombucha tea from white, green and black tea was studied for its microbial composition, chemical profile, and biological activities during 15-day fermentation period. HPLC analysis revealed key organic acids, including acetic, gluconic, and glucuronic acids in kombucha tea. In this study, white tea kombucha showed the highest glucuronic acid content. Green tea kombucha demonstrated the highest antioxidant activity by ABTS and FRAP assays. Moreover, white tea kombucha exhibited the strongest DPPH scavenging activity and high phenolic content. Additionally, kombucha tea could inhibit the growth of pathogenic bacteria, including Escherichia coli, E. coli O157:H7, Salmonella Typhi, Shigella dysenteriae, and Vibrio cholerae. Furthermore, green tea kombucha significantly inhibited nitric oxide production on LPS-stimulated RAW264.7 cells and demonstrated the strongest anti-inflammatory effect. These findings highlight a potential of kombucha tea as a functional beverage with antioxidant, antibacterial, and anti-inflammatory properties.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In recent years, there has been growing the interest in alternative health and wellness practices. Certain fermented food products contain high nutritional value. Among these are kefir, sauerkraut, kimchi, yogurt, and kombucha tea, and all of which are widely applied for their health benefits. Among the diverse array of fermented foods and beverages attracting health of consumers, kombucha tea stands out as a particularly probiotic beverage. Kombucha tea has gained substantial popularity as a favoured option for a refreshing and health-promoting beverage. The fermentation can extend the shelf life of food, enhance its flavour and texture, and encourage the growth of beneficial microbes that contribute to overall health1.

Kombucha tea is a fermented beverage made from tea and sugar through fermentation process of tea fungus2,3. Kombucha tea is frequently consumed as a healthy alternative to sugary drinks and is thought to have potential health benefits, including immune system stimulation and gut health improvement4.Nevertheless, recipe and brewing method directly affect its health benefits. Thus, further research is needed for a comprehensive understanding. In the kombucha tea fermentation process, sucrose serves as the primary carbon source for acetic acid bacteria and yeast. This fermented tea is produced by fermenting tea with sucrose through a symbiotic interaction between acetic acid bacteria and yeast5,6. During primary fermentation, yeast breaks down disaccharides into glucose and fructose, producing ethanol as a by-product7. As the alcohol concentration increases, it stimulates the growth of acetic acid bacteria, which produces beneficial organic acids such as acetic acid and gluconic acid, both of which have been reported to possess antimicrobial properties8. Additionally, Acetobacter xylinum produces cellulose, forming a film on the surface of the tea that facilitates yeast and bacteria attachment9. As a result, the alcohol concentration in fermented tea remains low compared to traditional alcoholic beverages10,11. Kombucha tea contains both carbon dioxide and alcohol, giving it a cider-like character6. This fermentation process results in a slightly carbonated, tangy, and sweet beverage that is rich in probiotics and antioxidants12,13. In addition, fermented tea offers several health benefits, including immune system enhancement, anticancer, anti-oxidative, anti-inflammatory, and antibacterial activities10,14,15,16.

Although many commercial brands produce ready-made kombucha tea in a variety of flavours and brewing methods, there are a few scientific reports on microbial and biochemical changes during the kombucha tea fermentation process. In this study, microbial and biochemical changes in different types of kombucha tea, including white, green, and black kombucha tea were investigated throughout the fermentation process. Additionally, the antibacterial and anti-inflammatory activities of different kombucha tea types were assessed. Thus, the aims of this study were to explore microbial and biochemical changes during kombucha tea fermentation, as well as its antioxidant, antibacterial, and anti-inflammatory activities.

Materials and methods

The tea leaves and kombucha starter culture

Tea leaves (Camellia sinensis) and starter culture were kindly provided by Tea Gallery Group (Thailand) Co., Ltd. in Chiang Mai, Thailand. Kombucha tea was prepared using 1% (w/v) tea leaves and 10% (w/v) sucrose. The starter culture, consisting of both yeast and acetic acid bacteria, was used as a consortium culture with yeast and acetic acid bacteria levels of 8.0–9.0 log CFU/mL.

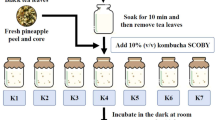

Preparation of kombucha tea

Kombucha tea was prepared using three different types of tea, including white tea, green tea, and black tea17. 1% (w/v) of dried tea leaves was added to sterile distilled water and boiled for 15 min. Then, 10% (w/v) sucrose was added, and the mixture was filtered into a sterilized container. The kombucha starter culture, at a concentration of 10% (v/v), was then inoculated into the tea solution. Fermentation was carried out at room temperature for 15 days, with microbial and chemical analysis at 0, 3, 6, 9, 12, and 15 days.

Culture-dependent microbial growth investigation

The total count of acetic acid bacteria and yeasts in kombucha tea were quantified using the spread plate technique18,19. Kombucha samples were spread on yeast peptone mannitol agar (YPM agar) supplemented with 25 µg/mL amphotericin B as an antifungal agent for the selective enumeration of acetic acid bacteria. Similarly, yeast populations were quantified by plating kombucha samples on yeast malt agar (YM agar) containing 100 µg/mL chloramphenicol as an antibacterial agent. The culture plates were incubated at 30 °C for 72 h, after which colonies were counted and expressed as colony forming units per millilitre (CFU/mL).

Chemical analysis of kombucha tea

The pH, titratable acidity, organic acids, total soluble solids, alcohol content, and metabolic profiles of kombucha tea were analysed at various time points during the fermentation process, specifically at 0, 3, 6, 9, 12, and 15 days.

pH and titratable acidity analysis

The pH of kombucha tea was determined by electronic pH meter (OHAUS, Parsippany, New Jersey, United States). The total acidity was determined by titration technique with 0.1 M NaOH. The volume of NaOH used was calculated and compared to acetic acid and the results were expressed as grams of acetic acid per litre of sample using this formulation:

VNaOH = volume of NaOH used in titration. MNaoH = molarity of NaOH. MWAcetic acid = molecular weight of acetic acid = 60.05 g/mol. VSample = volume of kombucha sample used for titration (litre).

High-performance liquid chromatography analysis of organic acids composition

The main organic acids present in kombucha tea were detected using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). Metabolic organic acids were analyzed using gradient HPLC system equipped with a conventional C18 column. Authentic standards of organic acids that commonly found in kombucha tea were used for comparison, including glucuronic acid (Sigma-Aldich, Darmstadt, Germany), gluconic acid (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany), D-saccharic acid 1,4-lactone (DSL) (Sigma-Aldich, Germany), acetic acid (Merck, Germany), ascorbic acid (Merck, Germany), lactic acid (Loba Chemie, India), citric acid (Fisher Scientific, United states), and succinic acid (Merck, Germany). A 10 µL of sample, filtered through a 0.45 μm PTFE microfilter, was injected into HPLC system (Agilent Technologies 1,200 series, Santa Clara, CA, USA). The system was adjusted according to Kaewkod et al. (2019) with modifications17. Briefly, chromatography was performed using an Inertsil ODS-3 C18 column (4.6 × 150 mm, 5 μm; GL Sciences, Tokyo, Japan) at a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min. The column temperature was maintained at 25 °C, and detection was carried out at 210 nm using a UV detector. The HPLC system was operated with 20 mM KH₂PO₄ (pH 2.4) as mobile phase A and methanol as mobile phase B. The HPLC gradient program (30 min) was as follows: starting with 100% 20 mM KH2PO4 (pH 2.4), methanol was increased to 5% at 3 min and then completely removed by 25 min. Finally, 100% 20 mM KH2PO4 (pH 2.4) was eluted and maintained for 5 min to equilibrate the column. The total HPLC gradient run time was 30 min.

Total soluble solid (°Brix)16

The total soluble solids (°Brix) were measured by refractometer (RHB-62ATC, JEDTO, Halden, Norway).

Gas chromatography analysis of alcoholic content

Preparation of standard solutions

Absolute ethanol, procured from RCI Labscan, was used as the standard. The standard solution was prepared by diluting with deionized water and filtering the mixture through a 0.45 μm disposable syringe filter. The resulting working standard solution underwent a 2-fold serial dilution, ranging from 0.1563 to 10.0 g/L.

GC analyses

Gas chromatography was used to determine the ethanol content in kombucha tea. The analysis was performed on an Agilent 7890B Gas Chromatography system, equipped with an HP-5 column (30 m x 0.320 mm x 1 μm) (Santa Clara, CA, USA). Helium was used as the mobile phase and the temperature program was set as follows: an initial temperature of 35 °C for 2 min, followed by a ramp of 25 °C/min to 90 °C with a 4.3-minute hold, then a 100 °C/min ramp to 250 °C with a 3-minute hold, resulting in a total run time of 13.1 min. The instrument condition is summarized in Table 1.

Determination of total phenolics content

The total phenolics content of the kombucha tea was determined using the Folin-Ciocalteu assay, with gallic acid as the standard. The reaction mixture consisted of 25 µL of sample, diluted with 125 µL of deionized H2O, 12.5 µL of 50% Folin-Ciocalteu reagent, and 25 µL of 95% ethanol. After 5 min, 5% Na2CO3 was added. The suspension was incubated for 1 h and the absorbance was measured at 725 nm. A calibration curve was established by plotting the absorbance at 725 nm for gallic acid at various concentrations (10–100 µg/mL). The antioxidant activity was reported as milligrams of gallic acid equivalent per millilitre of kombucha tea(mg GAE/mL kombucha tea).

Determination of total flavonoids content

The total flavonoids content of the kombucha tea was determined using the aluminum chloride colorimetric assay, with quercetin as the standard. The reaction mixture consisted of 20 µL of the sample diluted with 60 µL of methanol, 4 µL of 10% (w/v) aluminum chloride, 4 µL of 1 M potassium acetate, and 112 µL of deionized water. After 30 min of incubation, the absorbance was measured at 415 nm. A calibration curve was established by plotting the absorbance at 415 nm for quercetin at various concentrations (7.8125–125 µg/mL). The total flavonoids content was reported as milligrams of quercetin equivalent per millilitre of kombucha tea (mg QE/ mL kombucha tea).

Antioxidant activity

DPPH radical scavenging activity assay

The in vitro free radical scavenging activity was assessed using 2,2′- diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) assay20 with minor modification. The reaction mixture consisted of 50 µL of sample and 150 µL of 0.1 mM DPPH. After 15 min of incubation, the absorbance was measured at 517 nm. A calibration curve was established by plotting the absorbance at 517 nm for gallic acid at various concentrations (1–10 µg/mL). The antioxidant activity was reported as milligrams of gallic acid equivalent per millilitre of kombucha tea (mg GAE/mL kombucha tea), and the resulting 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) values were calculated.

ABTS radical scavenging activity assay

The antioxidant activity of kombucha tea from white tea, green tea, and black tea was determined using the ABTS assay21. The 2,2′-azinobis (3-ethylbenzthiazoline-6-sulphonic acid) or ABTS cation was dissolved in deionized water at a concentration of 7 mM. To prepare the ABTS reagent, 7 mM ABTS was mixed with 2.45 mM potassium persulfate (K2S2O8) at a 1:1 ratio. The working solution of the ABTS reagent was adjusted to an absorbance of 0.7 ± 0.002 at 734 nm by diluting with deionized water after incubation at room temperature for 12–16 h. The reaction mixture consisted of 5 µL of sample and 195 µL of adjusted ABTS reagent. The mixture was analyzed at a 734 nm after incubation for 10 min. A calibration curve was established by plotting the absorbance at 734 nm for trolox at various concentrations (25–450 µg/mL), and the antioxidant activity was reported as milligrams of trolox equivalent per millilitre of kombucha tea (mg TE/ mL kombucha tea). The 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) values were then calculated.

FRAP (ferric reducing antioxidant power) assay

The antioxidant power of fermented tea was measured using the FRAP assay22. The method is based on the reduction of Fe3+ - TPTZ (2,4,6-tripyridyl-s-triazine) complex (FRAP reagent) to the ferrous (Fe2+) form. Briefly, the FRAP reagent was prepared by mixing 300 mM acetate buffer (pH 3.6), 10 mM TPTZ solution in 40 mM HCl and 20 mM FeCl3 at a 10:1:1 ratio. The reaction mixture consisted of 50 µL of sample and 100 µL of FRAP reagent. The resulting suspension was analyzed at a wavelength of 593 nm after 15 min. A calibration curve was established by plotting the absorbance at 593 nm for trolox at various concentrations (10–100 µg/mL), and the antioxidant activity was reported as milligrams of Trolox equivalent per millilitre of kombucha tea (mg TE/mL kombucha tea). The resulting 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) values were then calculated.

Antibacterial activity

The antibacterial activity was assessed using the broth dilution technique to determine the minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) and minimal bactericidal concentration (MBC). Mueller-Hinton broth (Difco™, USA) was pipetted into a sterile 96-well culture plate with a round bottom, 100 µL per well. A 100% kombucha tea solution was added in equal volume into the first well, followed by 2-fold serial dilutions of kombucha tea. Pathogenic bacteria, including Escherichia coli, E. coli O157:H7 DMST 12,743, Shigella dysenteriae DMST 1511, Salmonella Typhi DMST 22,842, and Vibrio cholerae were kindly provided by the Division of Microbiology, Department of Medical Technology, Faculty of Associated Medical Sciences, Chiang Mai University, Chiang Mai, Thailand. All tested bacteria were cultured for 24 h, adjusted to 1.0 × 108 CFU/mL, and added at 100 µL per well. After 24 h of incubation, the MIC value was determined by identifying the lowest concentration at which no bacterial growth, with an untreated well used as a reference. The suspension from each well was streaked on Mueller-Hinton agar and incubated for an additional 24 h to determine the MBC value, which was identified from the well showing no bacterial colony growth. Gentamicin was used as a positive control, and unfermented tea was tested in parallel.

Anti-inflammatory activity

Cell culture

Murine macrophage RAW264.7 cell were cultured in Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM) (Gibco, Grand Island, NY, USA) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (100 U/mL penicillin and 100 µg/mL streptomycin) under humidified condition with 5% CO2 at 37 °C.

Cell viability assay

The cytotoxicity of kombucha tea on murine macrophage RAW264.7 cells was determined using the MTT assay. RAW264.7 cells were seeded at 1.0 × 105 cells per well into a 96-well cell culture plate with a flat bottom. The kombucha tea solution was 2-fold serially diluted, ranging from 0.31 to 10%, in c-DMEM, and 100 µL was added to the cells. After 24 h of incubation, cell viability was observed by measuring mitochondrial activity using an MTT solution at 2 mg/mL. After 4 h of incubation, DMSO was added to dissolve the formazan crystals. The absorbance was measured at 540 and 630 nm using a microplate reader (EZ Read 2000, Biochrom, Cambridge, UK). The percentage of cell viability was calculated, with non-treated cells serving as a reference. Cell cytotoxicity above 80% (CC80) was used for further experiment.

Inhibition of nitric oxide production

The effect of kombucha tea on nitric oxide production in LPS-stimulated RAW264.7 cells was determined using the Griess reagent. Murine macrophage RAW264.7 cells were seeded at 1.0 × 105 cells per well into a 96-well flat-bottom cell culture plate. Kombucha tea at non-toxic doses was diluted in c-DMEM, with or without 5 ng/mL LPS, and 100 µL of the solution was added to each well. After 24 h of incubation, the culture medium was transferred to a new 96-well plate and mixed with 100 µL of Griess reagent. The colorimetric reaction was measured at 540 nm using a microplate reader after a 10-minute incubation at room temperature. The percentage of inhibition was calculated relative to non-treated LPS-stimulated cells.

Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis was performed using Prism 9.5.0 for macOS. The experiments were conducted in triplicate, and the data are presented as mean ± standard deviation. Statistical comparisons were made using One-Way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA), Two-Way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) and Pearson Correlation Coefficient (r).

Results

Physical characteristic alteration of Kombucha tea

Kombucha tea was prepared using white tea, green tea, and black tea. After 15 days of fermentation, the kombucha tea prepared from white tea exhibited a dark brown colour, while kombucha tea made from black tea was slightly darker. In contrast, kombucha tea prepared from green tea had a yellowish-brown colour. Additionally, during the fermentation process, a thin layer of cellulose formed on the surface of the suspension. This cellulose layer is a result of the metabolism of acetic acid bacteria (Fig. 1).

Culture-dependent microbial growth investigation

The fermentation of kombucha tea is carried out by the combined metabolic activity of yeasts, acetic acid bacteria (AAB) and lactic acid bacteria (LAB) in starter culture. In this study, sucrose was used as a carbon source. The three types of tea leaves (white tea, green tea, and black tea) used in this study did not significantly affect the growth of yeast and acetic acid bacteria during kombucha tea fermentation process. The dynamic of microbial change during fermentation are shown in Fig. 2A. At the initiation of fermentation, the number of acetic acid bacteria colonies was 6.968, 7.062, and 6.504 log CFU/mL for white, green, and black tea, respectively, upon the addition of 10% kombucha starter. Additionally, the total yeast cells at the initiation of the fermentation were 6.033, 6.363, and 6.111 log CFU/mL for white, green, and black tea, respectively.

With an extension in the duration of the fermentation process, a notable increase in the population of bacterial and yeast cells was observed compared to the initial stages of fermentation. This finding suggests that fermentation time significantly influences the of microbial populations, as shown in Fig. 2. Additionally, kombucha tea prepared from white tea exhibited the highest count of both acetic acid bacteria and yeast, with respective values of 9.496 and 9.412 log CFU/mL, compared to the other tea samples. In contrast, after 15 days of fermentation, the total count of acetic acid bacteria in kombucha tea from green and black tea was 9.061 and 9.384 log CFU/mL, respectively. The total count of yeast cells in green and black tea kombucha was 9.102 and 9.384 log CFU/mL, respectively.

Chemical analysis of kombucha tea

pH and titratable acidity analysis

The alterations in pH values during the kombucha tea fermentation process, with significant difference from initial pH values, were analysed, and the results are presented in Fig. 3A. At the end of the 15-day fermentation period, the pH of the kombucha tea prepared from green tea was significantly lower than that of black tea, with a recorded value of 2.380. The pH values of kombucha tea prepared from white and black tea were 2.483 and 2.650, respectively. Moreover, the investigation of titratable acidity during the kombucha tea fermentation process revealed a significant increase compared to the initial day, as shown in Fig. 3B. The highest total titratable acidity was observed from white tea kombucha, with a concentration of 27.16 g/L, which was higher than that of green tea kombucha (27.16 g/L) and black tea kombucha (22.48 g/L).

High performance liquid chromatography analysis of organic acids composition

The alteration of organic acids in kombucha tea from white tea, green tea, and black tea during the fermentation process was investigated using the HPLC technique. Eight organic acids commonly found in kombucha tea, including glucuronic acid, gluconic acid, D-saccharic acid 1,4-lactone (DSL), acetic acid, ascorbic acid, lactic acid, citric acid, and succinic acid, were eluted at different retention times, as shown in Fig. 4.

The quantification of organic acids composition in kombucha tea at different fermentation stages (0, 3, 6, 9, 12, and 15 days) was conducted using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), with results presented in supplementary data (supplementary Table S1). The dynamic changes in organic acids content over time were visualized using a colour gradient, ranging from purple (low concentration) to yellow (high concentration) (Fig. 5). The lowest concentration of each organic acids across all time points and kombucha tea types was set to 0%, while the highest concentration was set to 100%. This normalization allows for direct comparison of relative changes in organic acids levels over timeand their percentage is independent of their absolute concentrations. Acetic acid was identified as the predominant metabolite, with significantly higher concentrations compared to other organic acids across all tea types. The final acetic acid content in white, green, and black tea kombucha reached 23.86 ± 0.88 g/L, 23.15 ± 0.10 g/L, and 20.19 ± 0.08 g/L, respectively. White tea kombucha exhibited the highest concentrations of glucuronic acid (0.55 ± 0.03 g/L), acetic acid (23.86 ± 0.88 g/L), and succinic acid (2.76 ± 0.90 g/L), suggesting a distinct metabolic profile. In contrast, green tea kombucha demonstrated higher levels of gluconic acid (2.89 ± 0.03 g/L), ascorbic acid (0.34 ± 0.00 g/L), and citric acid (0.62 ± 0.02 g/L), indicating potential differences in microbial metabolism. Black tea kombucha displayed high gluconic acid concentrations from day 6 onward, while D-saccharic acid 1,4-lactone (DSL) peaked at day 9 before declining. These fermentation patterns highlight the differences in organic acids metabolism among kombucha tea types, which may influence their functional properties and health benefits.

The alteration of eight organic acids is presented during kombucha tea fermentation process. The dynamic changes in organic acids content over time are visualized using a colour gradient, ranging from purple (low concentration) to yellow (high concentration). The lowest concentration of each organic acids across all time points and types is set to 0%, while the highest concentration is set to 100%.

Total soluble solid (°Brix)

The total soluble solid in all kombucha sample was determined at various fermentation stages (0, 3, 6, 9, 12, and 15 days). A significantly decreased in total soluble solids was observed in kombucha tea prepared from white, green, and black tea (Fig. 6). Green and black tea showed a slight decrease from 10°Brix to 6°Brix, after 15 day of fermentation. In particular, the kombucha tea prepared from white tea exhibited the most substantial reduction, with a significant decrease from 10°Brix to 3°Brix.

Alcohol content

Ethanol production during the kombucha tea fermentation process was investigated using a Gas chromatography technique. The retention time for ethanol was observed to be 1.4 min, as shown in Fig. 7.

The chromatograms and corresponding ethanol levels are shown in Fig. 8 and summarized in supplementary Table S2. The ethanol concentration at day 15 was found to be higher than on the initial day, with significantly higher levels in kombucha tea prepared from white tea and black tea. The highest ethanol concentration was observed on day 12 of the fermentation, with values of 5.737, 2.381, and 3.396 (g/L) from white, green, and black tea kombucha, respectively. White tea kombucha revealed a statistically significant the highest concentration of ethanol concentration. On day 15, the ethanol levels were 4.575, 2.293, and 3.232 (g/L) for white, green, and black tea kombucha, respectively.

Determination of total phenolics content

The total phenolics content in different types of white, green and black tea kombucha was evaluated using the Folin-Ciocalteu assay, with gallic acid as the standard, after 15 days of fermentation. Moreover, the total phenolics content of unfermented tea was evaluated for comparison. The results were illustrated in Fig. 9A and summarized in supplementary Table S3. The total phenolic content of white and green tea kombucha was significantly higher than that in unfermented tea. Among the kombucha tea types, green tea kombucha exhibited the highest phenolics content, with a value of 1.182±0.04 mg GAE/ mL kombucha tea, followed by white tea (0.834±0.04 mg GAE/ mL kombucha tea) and black tea (0.339±0.02 mg GAE/ mL kombucha tea).

Determination of total flavonoids content

The total flavonoids content in different types of kombucha tea was evaluated using the aluminum chloride colourimetric assay, with quercetin as the standard, after 15 days of fermentation. Moreover, the total flavonoids content of unfermented tea was assessed for comparison. The results were illustrated in Fig. 9B and summarized in supplementary Table S3. The total flavonoids content of all types of kombucha tea revealed a slight decrease compared to the corresponding unfermented tea. Among the kombucha tea types, black tea kombucha exhibited the highest flavonoids content, with a value of 0.039±0.003 mg QE/ mL kombucha tea, followed by green tea (0.034±0.004 mg QE/ mL kombucha tea) and white tea (0.022±0.005 mg QE/ mL kombucha tea).

Total phenolics content (A) and total flavonoids content (B) of kombucha tea at 15 days of fermentation period and unfermented tea by Folin-Ciocalteu assay and aluminum chloride colourimetric assay, respectively. * Indicates significant difference between different type of kombucha (p < 0.05) and # Indicates significant difference compared to unfermented tea (p < 0.05).

Antioxidant activity

DPPH radical scavenging activity assay

The in vitro assessment of free radical scavenging activity was performed using 2,2′- diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) assay, and the 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) values were calculated. The antioxidant activity was reported as milligrams of Gallic acid equivalent per millilitre of kombucha tea (mg GAE/mL kombucha tea). The free radical scavenging activity of unfermented tea was also evaluated for comparison. The results of antioxidant activity were illustrated in Fig. 10A and summarized in supplementary Table S4. Kombucha tea prepared from white tea and green tea exhibited significantly higher antioxidant activity than unfermented tea. Conversely, the antioxidant activity of black tea kombucha did not differ significantly from unfermented black tea. The IC₅₀ values were 4.205 ± 0.357% (v/v) for white tea kombucha, 4.630 ± 0.511% (v/v) for green tea kombucha, and 22.891 ± 1.801% (v/v) for black tea kombucha. White and green tea kombucha demonstrated significantly higher DPPH scavenging activity, with values of 1.059 ± 0.087 and 0.965 ± 0.112 mg GAE/mL kombucha tea, respectively, compared to black tea kombucha (0.194 ± 0.015 mg GAE/mL kombucha tea).

ABTS radical scavenging activity assay

The free radical scavenging activity of kombucha tea was determined using 2,2′-azino-bis (3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) (ABTS) radical cation-based assay, and the 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) values were calculated. The antioxidant activity was reported as milligrams of Trolox equivalent per gram of millilitre of kombucha tea (mg TE/mL kombucha tea) as revealed in Fig. 10B and Table S4. The highest ABTS scavenging activity was obtained from kombucha tea prepared from green tea, which exhibited significantly higher antioxidant activity than unfermented green tea, with an IC₅₀ value of 4.044 ± 0.246% (v/v). Conversely, kombucha tea prepared from white tea and black tea did not show significant differences compared to their unfermented tea, with IC₅₀ values of 5.385 ± 0.087% and 19.312 ± 0.971% (v/v), respectively. Green tea kombucha demonstrated significantly higher ABTS scavenging activity, with a value of 4.878 ± 0.30 mg TE/mL kombucha tea, followed by white tea (3.655 ± 0.06 mg TE/mL kombucha tea) and black tea (1.021 ± 0.05 mg TE/mL kombucha tea).

FRAP (ferric reducing antioxidant power) assay

The antioxidant activity of the fermented tea was evaluated using the FRAP assay, which is based on the reduction of the Fe³⁺-TPTZ (2,4,6-tripyridyl-s-triazine) complex (FRAP reagent) to the ferrous (Fe²⁺) form. The results were reported as milligrams of Trolox equivalent per millilitre of kombucha tea (mg TE/mL kombucha tea). Moreover, the free radical scavenging activity of unfermented tea was evaluated for comparison. The result show that all type of kombucha tea revealed dramatically higher antioxidant activity compared to unfermented tea. Among the samples, kombucha tea prepared from green tea demonstrated the highest antioxidant activity, with values of 8.216 ± 0.20 mg TE/mL, followed by white tea (7.839 ± 0.11 mg TE/mL) and black tea (4.379 ± 0.15 mg TE/mL), as shown in Fig. 10C and Table S4.

Antibacterial activity

The antibacterial activity of kombucha tea was determined using the broth dilution method and unfermented tea was also determined for comparison. The results indicated that all kombucha tea varieties exhibited antibacterial activity against the pathogenic bacteria, including Escherichia coli, E. coli O157:H7, Salmonella Typhi, Shigella dysenteriae, and Vibrio cholerae (Table 2). However, unfermented tea showed very low antibacterial activity (Table 2). Among the kombucha samples, white tea kombucha (WK) displayed the strongest antibacterial activity, with the lowest MIC values of 6.25% v/v and MBC values of 25% v/v against Escherichia coli and E. coli O157:H7. It also showed moderate inhibition against Salmonella Typhi, Shigella dysenteriae, and Vibrio cholerae with MIC values of 12.5% v/v and MBC values of 50% v/v. Green tea kombucha (GK) demonstrated strong inhibition against Shigella dysenteriae with MIC values of 6.25% v/v and MBC values of 25% v/v but exhibited slightly higher MIC values of 12.5% v/v and MBC values of 50% v/v for the other bacteria. Black tea kombucha (BK) showed a consistent MIC value of 12.5% v/v and MBC values of 50% v/v across all tested bacterial strains, indicating moderate antibacterial activity.

Cell viability assay

The effect of kombucha tea on cell viability was measured using the MTT assay. Cell viability was assessed after incubation with different types of kombucha tea at concentrations of 0.63%, 1.25%, 2.5%, 5%, and 10% (v/v). The results indicated that RAW264.7 Cell viability remained above 80% when treated with kombucha tea at a concentration of 10% (v/v) (Fig. 11). Based on these findings, all kombucha tea were tested at a concentration of 10% (v/v) in subsequent experiments.

Anti-inflammatory activity

The inhibition of nitric oxide production by kombucha tea was assessed in LPS-stimulated RAW264.7 cells using Griess assay. Murine macrophage RAW264.7 cells were treated with kombucha tea at a concentration of cell cytotoxicity above 80% (CC80). The results demonstrated that kombucha tea reduced nitric oxide production in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 12). Green tea kombucha exhibited the highest inhibition at 81.72 ± 1.57%, followed by white tea kombucha at 68.60 ± 1.92%, and black tea kombucha at 46.80 ± 2.77%.

Correlation between organic acids, antioxidant, antioxidative, and phytochemical content

The correlation matrix provided insights into the relationships between organic acids, antioxidant activity (DPPH, ABTS, and FRAP assays), phenolics and flavonoids content (Fig. 13). Strong positive correlations were observed between acetic acid and the antioxidant assays, suggesting its significant contribution to antioxidant capacity. Similarly, NO inhibition showed a strong positive correlation with acetic acid, ABTS assay, and FRAP assay, reinforcing the link between antioxidant potential and NO inhibition. D-saccharic acid 1,4-lactone also exhibited a strong positive correlation with ABTS, FRAP, and NO inhibition highlighting its potential role in antioxidant mechanisms. Additionally, citric acid content demonstrated positive correlation with antioxidant activity, while the glucuronic acid content showed positive correlation with both DPPH and FRAP assays.

Conversely, several strong negative correlations indicated inverse relationships in metabolic processes. Glucuronic acid was negatively correlated with gluconic acid and ascorbic acid suggesting that these compounds may be produced through opposing pathways. D-saccharic acid 1,4-lactone was negatively correlated with acetic acid and citric acid. Interestingly, flavonoids content exhibited a negative correlation with DPPH, ABTS, and FRAP assays, while phenolics content showed strong positive correlations with these assays.

Discussion

Kombucha tea is fermented beverage prepared using a symbiosis starter culture of acetic acid bacteria and yeast cells. The alteration of microbial community and chemical properties during kombucha tea fermentation process were demonstrated in this study as well as their antioxidant, antibacterial, and anti-inflammatory activities. During the fermentation process, cellulose production by the acetic acid bacteria, particularly Acetobacter xylinum, was observed from day 3 to day 15 of fermentation23. The production of cellulose is crucial during the fermentation process as it facilitates the attachment of bacteria and yeast, which contributes to the medicinal effects of beverage, including anti-inflammatory, antibacterial, and antioxidant activities24. In this study, the kombucha tea fermentation process was performed for 15 days due to the level of acidity, and the presence of major components of tea fungus metabolites still being detected as well as their antioxidant capacity25. The prolonged fermentation time can lead to excessive production of organic acids and lead to harmful effects if consumed directly10,26.

The bacterial community in kombucha tea is predominantly composed of acetic acid bacteria (AAB), with the most prevalent genera such as Acetobacter, Komagataeibacter, and Gluconacetobacter27. These bacteria are crucial in producing acetic acid, which imparts the characteristic vinegar-like taste to kombucha tea28. The yeast population in kombucha tea is also diverse, with commonly detected genera such as Brettanomyces, Saccharomyces, Zygosaccharomyces, and Pichia29. Interestingly, Gluconacetobacter was found to be more abundant in black tea kombucha, whereas Acetobacter was more dominant in green tea kombucha. Additionally, Pichia was more abundant in black tea kombucha, while Saccharomyces was more prevalent in green tea kombucha30. During fermentation, the invertase enzyme from yeast hydrolyses disaccharides into monosaccharide and ethanol31. Glucose is metabolised into gluconic acid, while ethanol is converted into acetic acid, which is major organic acids present in kombucha tea14. The number of bacterial and yeast cells increases significantly when the fermentation period is extended. However, the types of tea, including white tea, green tea, and black tea, did not significantly affect the total bacterial and yeast cells. Among the three types of kombucha tea, white tea kombucha had the highest total count of bacteria and yeast, which might be attributed to its preparation steps. White tea is made from fresh buds and young leaves of Camellia sinensis with minimal oxidation. Additionally, white tea typically has the lowest caffeine content when compared to green tea and black tea. The diversity of microorganism found in white tea is also higher than in the other types of tea32.

The pH of all kombucha tea types significantly decreased due to organic acids production through bacterial metabolism. Green tea kombucha exhibited the lowest pH, which was significantly different from black tea, while white tea kombucha did not show a significant difference from green tea. This indicates that tea type alone does not fully determine pH changes. On the other hand, titratable acidity, mainly from acetic acid, was the highest in white tea, followed by green and black tea. Microorganisms metabolised sucrose to produce organic acids, resulting in a reduction of total soluble solids. Variations in titratable acidity were associated with the microbial populations, with the most abundant acetic acid bacteria and yeast in white tea kombucha. The higher organic acids content, particularly acetic and gluconic acids, contributed to the lower pH and influenced microbial growth, highlighting the direct relationship between microbial activity and organic acids production33.

HPLC analysis of kombucha tea fermentation revealed variations in organic acids, including glucuronic acid, gluconic acid, D-saccharic acid 1,4-lactone (DSL), acetic acid, ascorbic acid, lactic acid, citric acid, and succinic acid, which were separated and based on their hydrophobicity, size, and polarity34. The organic acids were eluted from C18 column in this order; glucuronic acid, gluconic acid, DSL, ascorbic acid, lactic acid, acetic acid, citric acid, and succinic acid. Furthermore, acetic acid was commonly found at higher levels in vinegar but glucuronic acid was present in limited amounts35. Moreover, glucuronic acid was found very low level in water kefir36. Predominantly, gluconic acid, succinic acid, and acetic acid were detected in kombucha tea. White tea kombucha exhibited the highest levels of glucuronic and acetic acids, while black tea kombucha contained the highest concentration of DSL. Acetic acid has been shown to reduce hyperglycaemia in mice by AMPK activation37. Glucuronic acid is known for its detoxifying38 and vitamin C biosynthesis39. It binds to toxins in the liver, facilitating their excretion from the body. This process may aid in detoxification and support liver health. While, DSL offers potential health benefits, including antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties and improved glucose tolerance. DSL has been found to enhance glucose tolerance in animals, indicating its potential benefits for people with diabetes or risk of developing diabetes40.

Although kombucha tea is generally considered non-alcoholic, trace amount of alcohol is produced during fermentation through yeast metabolism. Gas chromatography with a flame ionization detector revealed that white tea kombucha had the highest alcohol content, which correlated with higher yeast and acetic acid bacteria. However, by day 15, the alcohol level slightly decreased from day 12, which was likely due to acetic acid bacteria converting ethanol into acetic acid41. While excessive alcohol consumption poses health risks, but moderate intake has been associated with potential benefits, such as reduced cardiovascular disease risk, improved cognitive function, and lower diabetes and cancer risks42,43.

The total phenolic content of different types of kombucha tea was assessed using the Folin-Ciocalteu assay, revealing significantly higher levels in white and green tea kombucha when compared to unfermented tea. Green tea kombucha had the highest phenolics content, followed by white and black tea. This is likely due to the naturally higher phenolic compounds in green tea leaves, such as catechins and flavonols. While fermentation can enhance phenolic content through microbial metabolism, the initial concentration in tea plays a crucial role. The higher phenolic content in green tea kombucha aligned with previous studies that reported higher levels of phenolic content in green tea compared to white and black tea44,45. Green tea contained higher amounts of catechins, flavonols, and phenolics acids, which attributed to its minimal oxidation during processing46,47,48. Phenolic compounds exhibit antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties and potentially prevent various diseases by modulating gene expression in inflammatory pathways49,50. Additionally, glucuronic and acetic acid regulate blood sugar levels and enhance insulin sensitivity. Acetic acid can improve endothelial and mitochondrial function. While the high phenolic content in kombucha tea may offer health benefits, further research is needed to assess its bioavailability and therapeutic effectiveness.

The total flavonoid content of kombucha tea was decreased after fermentation due to flavonoids transformation. Despite this reduction, flavonoid-rich kombucha tea continues to offer health benefits. Among the different kombucha tea types, black tea kombucha contained the highest flavonoids levels, followed by green and white tea kombucha. Flavonoids are known for their antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, neuroprotective, and anti-cancer properties. Their intake has been linked to a lower risk of chronic diseases such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and cancer51,52,53,54.

Antioxidant activity was evaluated using DPPH, ABTS, and FRAP assays. White and green tea kombucha exhibited significantly higher DPPH scavenging activity than unfermented tea, whereas black tea kombucha showed no significant difference. This may be attributed to the lower phenolic content in black tea, which limits the effective of fermentation in enhancing its antioxidant activity. Green tea kombucha had the highest ABTS scavenging activity, significantly differing from unfermented tea, while no significant differences were observed in white and black tea kombucha. The FRAP assay indicated that all kombucha tea types had significantly higher ferric reducing activity than unfermented tea. Green tea kombucha showed the highest activity followed by white and black tea. These results suggest that fermentation enhances antioxidant activity. Moreover, the type of tea playing a key role and differences in processing methods affect the bioactive compound content in white tea, green tea, and black tea.

The antibacterial activity of kombucha tea was assessed using the broth dilution method. Enteric bacterial infections, including gastroenteritis and diarrhoea, have become more prevalent due to changing dietary habits, particularly in developing countries55. Common diarrhoeal pathogens such as Escherichia coli, E. coli O157:H7, Salmonella Typhi, Shigella dysenteriae, and Vibrio cholerae, pose significant health risks. However, the increasing prevalence of multi-drug-resistant strains has made treatment more costly and less effective56. Underscoring the urgent need to explore natural products, including traditional foods and medicines, as alternative antimicrobial agents to combat drug-resistant bacteria is required57. Interestingly, various natural substances, such as tea extracts, Zingiber officinale, and Euphorbia hirta, have been reported to exhibit antimicrobial activity against enteric pathogens58,59. Black and green tea kombucha demonstrated antibacterial effects against E. coli, V. cholerae, and Staphylococcus aureus6061. Despite kombucha tea’s widespread consumption as a functional beverage for its potential health benefits, scientific evidence on kombucha tea prepared from white and green tea remains a few. This study evaluates the antibacterial activity of white, green, and black tea kombucha after 15 days of fermentation.

Antimicrobial activity of kombucha tea is attributed to its bioactive components, including organic acids (acetic, gluconic, and glucuronic acids), bacteriocins, proteins, enzymes, and tea polyphenols10,62. Acetic acid is predominantly responsible for distinctive sour taste of kombucha tea and possesses antimicrobial properties, which can inhibit the growth of harmful bacteria such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa63. Moreover, succinic acid showed antibacterial activity on Salmonella64.

Our findings revealed that fermentation process enhanced antibacterial activity. White tea kombucha exhibited the strongest antibacterial activity, with the lowest minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) and minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC) against E. coli O157:H7, a pathogen responsible for acute haemorrhagic diarrhoea. The MIC and MBC values of white tea kombucha were twice and three times lowerthan those of green and black tea kombucha, respectively. This enhanced antibacterial activity is correlated with the higher levels of organic acids, particularly glucuronic and acetic acid, found in white tea kombucha, as determined by HPLC analysis.

The toxicity of kombucha tea was assessed on murine macrophage RAW264.7 cells using the MTT assay. At a 10% concentration, cell viability remained above 80% for all types tested. Non-cytotoxic concentrations were then used to evaluate nitric oxide (NO) production via the Griess assay. NO plays a crucial role in immune defence, inflammation, and neurotransmission; however, excessive production can induce inflammation65,66. When kombucha tea was co-incubated with LPS, NO release was inhibited in a dose-dependent manner, with the strongest suppression that observed in green tea kombucha, followed by white and black tea kombucha. The higher inhibitory effect of green tea kombucha is likely due to its elevated catechin, epicatechin, and EGCG content. These compounds are known for their potent anti-inflammatory properties and antioxidant activity67,68. These findings suggest that these substances may downregulate both iNOS gene expression and protein levels. In the future, further studies, such as immunoblotting analysis, are needed to confirm the precise molecular mechanisms underlying this effect.

The correlation between organic acids, antioxidants, and phytochemical content was analysed using the Pearson correlation coefficient. The matrix reveals that acetic acid and D-saccharic acid 1,4-lactone are key contributors to antioxidant activity and NO inhibition of kombucha tea, as they strongly correlate with antioxidant assays (DPPH, ABTS, FRAP) and NO inhibition. Conversely, negative correlations suggest opposing metabolic pathways, with glucuronic acid inversely related to gluconic and ascorbic acids, and D-saccharic acid 1,4-lactone negatively correlated with acetic and citric acids. While phenolics content positively correlates with antioxidant activity, flavonoids content shows a negative correlation, suggesting a limited role. These findings highlight potential bioactive compounds that are responsible for the antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects of kombucha tea.

Kombucha tea is widely recognized as a probiotic beverage with potential health benefits, such as promoting gut health, boosting the immune system, and exhibiting antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties69,70. However, it is also important to consider the potential risks associated with its consumption69. One key concern is contamination by harmful microorganisms71, particularly if proper hygiene and brewing techniques are not followed. Additionally, over-fermentation can lead to an increase of alcohol content, which may be undesirable72. High acidity of kombucha tea can also be harmful to the digestive system. It can cause irritation in individual with sensitive stomach26. However, when kombucha tea is prepared and consumed properly, these risks are relatively low compared to the potential health benefits. Maintaining strict hygiene practices, ensuring an appropriate fermentation period, and storing kombucha tea under suitable conditions can effectively minimize these risks73. Nevertheless, further research is needed to fully understand its long-term health effects and any potential risks associated with excessive consumption.

Conclusion

This study provided insights into the microbial and biochemical changes that occurred during the fermentation of different types of kombucha tea including white tea, green tea, and black tea. The results suggested that the choice of tea leaves (Camellia sinensis) significantly influenced the organic acids composition, while the fermentation process enhanced the total phenolic content and antioxidant activity of the beverage. Additionally, kombucha tea exhibited the potential antibacterial and anti-inflammatory activities. However, further research is needed to fully elucidate the health effects and potential benefits of kombucha tea.

Data availability

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

References

Paul Ross, R., Morgan, S. & Hill, C. Preservation and fermentation: past, present and future. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 79, 3–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0168-1605(02)00174-5 (2002).

Bishop, P., Pitts, E. R., Budner, D., Thompson-Witrick, K. A. & Kombucha: Biochemical and Microbiological impacts on the chemical and flavor profile. Food Chem. Adv. 1, 100025. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.focha.2022.100025 (2022).

Greenwalt, C. J., Steinkraus, K. H. & Ledford, R. A. Kombucha, the fermented tea: microbiology, composition, and claimed health effects. J. Food Prot. 63, 976–981. https://doi.org/10.4315/0362-028x-63.7.976 (2000).

Afsharmanesh, M. & Sadaghi, B. Effects of dietary alternatives (probiotic, green tea powder, and Kombucha tea) as antimicrobial growth promoters on growth, ileal nutrient digestibility, blood parameters, and immune response of broiler chickens. Comp. Clin. Pathol. 23, 717–724. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00580-013-1676-x (2014).

Chen, C. & Liu, B. Y. Changes in major components of tea fungus metabolites during prolonged fermentation. J. Appl. Microbiol. 89, 834–839. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2672.2000.01188.x (2000).

Teoh, A. L., Heard, G. & Cox, J. Yeast ecology of Kombucha fermentation. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 95, 119–126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2003.12.020 (2004).

Gaggìa, F. et al. Kombucha beverage from green, black and Rooibos teas: A comparative study looking at microbiology, chemistry and antioxidant activity. Nutrients 11, 1 (2019).

Al-Mohammadi, A. R. et al. Chemical constitution and antimicrobial activity of Kombucha fermented beverage. Molecules 26, 5026 (2021).

Laavanya, D., Shirkole, S. & Balasubramanian, P. Current challenges, applications and future perspectives of SCOBY cellulose of Kombucha fermentation. J. Clean. Prod. 295, 126454. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.126454 (2021).

Greenwalt, C. J., Steinkraus, K. H. & Ledford, R. A. Kombucha, the fermented tea: microbiology, composition, and claimed health effects. J. Food. Prot. 63, 976–981. https://doi.org/10.4315/0362-028X-63.7.976 (2000).

Malbaša, R., Lončar, E., Djurić, M. & Došenović, I. Effect of sucrose concentration on the products of Kombucha fermentation on molasses. Food Chem. 108, 926–932. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2007.11.069 (2008).

Ahmed, R. F., Hikal, M. S. & Abou-Taleb, K. A. Biological, chemical and antioxidant activities of different types Kombucha. Annals Agricultural Sci. 65, 35–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aoas.2020.04.001 (2020).

Liu, Y., Zheng, Y., Yang, T., Mac Regenstein, J. & Zhou, P. Functional properties and sensory characteristics of Kombucha analogs prepared with alternative materials. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 129, 608–616. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tifs.2022.11.001 (2022).

Dufresne, C., Farnworth, E. & Tea, Kombucha, and health: a review. Food Res. Int. 33, 409–421. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0963-9969(00)00067-3 (2000).

Zheng, Y. et al. Comprehensive evaluation of quality and bioactivity of Kombucha from six major tea types in China. Int. J. Gastronomy Food Sci. 36, 100910. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijgfs.2024.100910 (2024).

Silva, K. A. et al. Kombucha beverage from non-conventional edible plant infusion and green tea: characterization, toxicity, antioxidant activities and antimicrobial properties. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 34, 102032. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bcab.2021.102032 (2021).

Kaewkod, T., Bovonsombut, S. & Tragoolpua, Y. Efficacy of Kombucha obtained from green, Oolong, and black teas on Inhibition of pathogenic bacteria, antioxidation, and toxicity on colorectal Cancer cell line. Microorganisms 7, 700 (2019).

De Vero, L., Gullo, M. & Giudici, P. Acetic Acid Bacteria. 193–209 (CRC Press, 2017).

de Souza, A. C., Simões, L. A., Schwan, R. F. & Dias, D. R. (Springer, 2021).

Chan, E. W., Soh, E. Y., Tie, P. P. & Law, Y. P. Antioxidant and antibacterial properties of green, black, and herbal teas of Camellia sinensis. Pharmacognosy Res. 3, 266 (2011).

Wang, L., Ahmad, S., Wang, X., Li, H. & Luo, Y. Comparison of antioxidant and antibacterial activities of camellia oil from Hainan with camellia oil from Guangxi, Olive oil, and peanut oil. Front. Nutr. 8, 667744 (2021).

Genskowsky, E. et al. Determination of polyphenolics profile, antioxidant activity and antibacterial properties of Maqui [Aristotelia chilensis (Molina) Stuntz] a Chilean blackberry. J. Sci. Food. Agric. 96, 4235–4242 (2016).

Zhu, C., Li, F., Zhou, X., Lin, L. & Zhang, T. Kombucha-synthesized bacterial cellulose: preparation, characterization, and biocompatibility evaluation. J. Biomedical Mater. Res. Part. A. 102, 1548–1557. https://doi.org/10.1002/jbm.a.34796 (2014).

Sreeramulu, G., Zhu, Y. & Knol, W. Kombucha fermentation and its antimicrobial activity. J. Agric. Food Chem. 48, 2589–2594. https://doi.org/10.1021/jf991333m (2000).

Muhialdin, B. et al. Effects of sugar sources and fermentation time on the properties of tea fungus (kombucha) beverage. Int. Food Res. J. 26, 481–487 (2019).

Jayabalan, R., Subathradevi, P., Marimuthu, S., Sathishkumar, M. & Swaminathan, K. Changes in free-radical scavenging ability of Kombucha tea during fermentation. Food Chem. 109, 227–234. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2007.12.037 (2008).

Landis, E. A. et al. Microbial diversity and interaction specificity in Kombucha tea fermentations. Msystems 7, e00157–e00122 (2022).

Kaashyap, M., Cohen, M. & Mantri, N. Microbial diversity and characteristics of Kombucha as revealed by metagenomic and physicochemical analysis. Nutrients 13 https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13124446 (2021).

Njieukam, J. A. et al. Microbiological, functional, and Chemico-Physical characterization of artisanal Kombucha: an interesting reservoir of microbial diversity. Foods 13, 1947 (2024).

Coton, M. et al. Unraveling microbial ecology of industrial-scale Kombucha fermentations by metabarcoding and culture-based methods. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 93, fix048 (2017).

Gaggìa, F. et al. Kombucha beverage from green, black and rooibos teas: A comparative study looking at microbiology, chemistry and antioxidant activity. Nutrients 11 (2019).

Hilal, Y. & Engelhardt, U. Characterisation of white tea – Comparison to green and black tea. J. Für Verbraucherschutz Und Lebensmittelsicherheit. 2, 414–421. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00003-007-0250-3 (2007).

Hur, S. J., Lee, S. Y., Kim, Y. C., Choi, I. & Kim, G. B. Effect of fermentation on the antioxidant activity in plant-based foods. Food Chem. 160, 346–356. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2014.03.112 (2014).

Bélanger, J. M. R., Jocelyn Paré, J. R. & Sigouin, M. in Techniques and Instrumentation in Analytical Chemistry (Eds. Paré, J. R. J. & Bélanger, J. M. R.). Vol. 18. 37–59 (Elsevier, 1997).

Lynch, K. M., Zannini, E., Wilkinson, S., Daenen, L. & Arendt, E. K. Physiology of acetic acid bacteria and their role in vinegar and fermented beverages. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 18, 587–625 (2019).

Nguyen, N. K., Dong, N. T., Le, P. H. & Nguyen, H. T. Evaluation of the glucuronic acid production and other biological activities of fermented sweeten-black tea by Kombucha layer and the co-culture with different Lactobacillus Sp. strains. Int. J. Mod. Eng. Res. 4, 12–17 (2014).

Sakakibara, S., Yamauchi, T., Oshima, Y., Tsukamoto, Y. & Kadowaki, T. Acetic acid activates hepatic AMPK and reduces hyperglycemia in diabetic KK-A(y) mice. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 344, 597–604. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.03.176 (2006).

Martínez-Leal, J., Ponce-García, N. & Escalante-Aburto, A. Recent evidence of the beneficial effects associated with glucuronic acid contained in Kombucha beverages. Curr. Nutr. Rep. 9, 163–170. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13668-020-00312-6 (2020).

Vīna, I., Linde, R., Patetko, A. & Semjonovs, P. Glucuronic acid from fermented beverages: biochemical functions in humans and its role in health protection. Int. J. Res. Rev. Appl. Sci. 14, 217–230 (2013).

Bhattacharya, S., Manna, P., Gachhui, R. & Sil, P. C. d-Saccharic acid 1,4-lactone protects diabetic rat kidney by ameliorating hyperglycemia-mediated oxidative stress and renal inflammatory cytokines via NF-κB and PKC signaling. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmcol. 267, 16–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.taap.2012.12.005 (2013).

Gullo, M., Verzelloni, E. & Canonico, M. Aerobic submerged fermentation by acetic acid bacteria for vinegar production: process and biotechnological aspects. Process Biochem. 49, 1571–1579. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procbio.2014.07.003 (2014).

Nova, E., Baccan, G. C., Veses, A., Zapatera, B. & Marcos, A. Potential health benefits of moderate alcohol consumption: Current perspectives in research. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 71, 307–315 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1017/S0029665112000171

Le Daré, B., Lagente, V. & Gicquel, T. Ethanol and its metabolites: update on toxicity, benefits, and focus on Immunomodulatory effects. Drug Metab. Rev. 51, 545–561. https://doi.org/10.1080/03602532.2019.1679169 (2019).

Zhao, C. N. et al. Phenolics profiles and antioxidant activities of 30 tea infusions from green, black, Oolong, white, yellow and dark teas. Antioxidants 8 (2019).

Rusak, G., Komes, D., Likić, S., Horžić, D. & Kovač, M. Phenolics content and antioxidative capacity of green and white tea extracts depending on extraction conditions and the solvent used. Food Chem. 110, 852–858. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2008.02.072 (2008).

Lorenzo, J. M. & Munekata, P. E. S. Phenolics compounds of green tea: health benefits and technological application in food. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Biomed. 6, 709–719. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apjtb.2016.06.010 (2016).

Joe, A. V. Black and green tea and heart disease: A review. BioFactors 13, 127–132 (2000).

Graham, H. N. Green tea composition, consumption, and polyphenol chemistry. Prev. Med. 21, 334–350. https://doi.org/10.1016/0091-7435(92)90041-F (1992).

Azuma, Y., Ozasa, N., Ueda, Y. & Takagi, N. Pharmacological studies on the Anti-inflammatory action of phenolics compounds. J. Dent. Res. 65, 53–56. https://doi.org/10.1177/00220345860650010901 (1986).

Costa, G., Francisco, V., Lopes, C., Cruz, M. T., Batista, T. & M. & Intracellular signaling pathways modulated by phenolics compounds: application for new anti-inflammatory drugs discovery. Curr. Med. Chem. 19, 2876–2900 (2012).

Maleki, S. J., Crespo, J. F. & Cabanillas, B. Anti-inflammatory effects of flavonoids. Food Chem. 299, 125124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2019.125124 (2019).

Batra, P. & Sharma, A. K. Anti-cancer potential of flavonoids: recent trends and future perspectives. 3 Biotech. 3, 439–459. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13205-013-0117-5 (2013).

Yao, L. H. et al. Flavonoids in food and their health benefits. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 59, 113–122. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11130-004-0049-7 (2004).

Wang, H., Provan, G. J. & Helliwell, K. Tea flavonoids: their functions, utilisation and analysis. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 11, 152–160. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0924-2244(00)00061-3 (2000).

Cliver, D. O. & Riemann, H. P. Foodborne Infections and Intoxications (Elsevier, 2011).

Barman, S. et al. Plasmid-mediated streptomycin and sulfamethoxazole resistance in Shigella flexneri 3a. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 36, 348–351 (2010).

Bhattacharya, D. et al. Antibacterial activity of polyphenolics fraction of Kombucha against enteric bacterial pathogens. Curr. Microbiol. 73, 885–896 (2016).

Abubakar, E. Antibacterial activity of crude extracts of Euphorbia hirta against some bacteria associated with enteric infections. J. Med. Plants Res. 3, 498–505 (2009).

Kaewkod, T., Songkhakul, W. & Tragoolpua, Y. Inhibitory effects of tea leaf and medicinal plant extracts on enteric pathogenic bacteria growth, oxidation and epithelial cell adhesion. Pharmacogn. Res. 14 (2022).

Lacerda, U. V. et al. Antioxidant, antiproliferative, antibacterial, and antimalarial effects of Phenolic-Rich green tea Kombucha. Beverages 11, 7 (2025).

Barbosa, C. D. et al. Evaluation of antibacterial activity of black and green tea kombucha. Sci. Plena 18 (2022).

Jayabalan, R., Malbaša, R. V., Lončar, E. S., Vitas, J. S. & Sathishkumar, M. A review on Kombucha tea—microbiology, composition, fermentation, beneficial effects, toxicity, and tea fungus. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 13, 538–550 (2014).

Halstead, F. D. et al. The antibacterial activity of acetic acid against biofilm-producing pathogens of relevance to burns patients. PloS One. 10, e0136190 (2015).

Mohan, A. & Purohit, A. S. Anti-Salmonella activity of pyruvic and succinic acid in combination with oregano essential oil. Food Control. 110, 106960. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodcont.2019.106960 (2020).

Liang, C. F. et al. Endothelium-derived nitric oxide inhibits the relaxation of the Porcine coronary artery to natriuretic peptides by desensitizing big conductance calcium-activated potassium channels of vascular smooth muscle. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 334, 223–231 (2010).

Sharma, J. N., Al-Omran, A. & Parvathy, S. S. Role of nitric oxide in inflammatory diseases. Inflammopharmacology 15, 252–259. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10787-007-0013-x (2007).

Malbaša, R. V., Lončar, E. S. & Kolarov, L. A. TLC analysis of some phenolics compounds in kombucha beverage. Acta Period. Technol. 199–205 (2004).

Zhou, D. D. et al. Fermentation with tea residues enhances antioxidant activities and polyphenol contents in Kombucha beverages. Antioxidants 11, 155 (2022).

Coelho, R. M. D., Almeida, A. L., Amaral, R. Q. G., Mota, R. N. & Sousa, P. H. M. Kombucha: review. Int. J. Gastronomy Food Sci. 22, 100272. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijgfs.2020.100272 (2020).

Villarreal-Soto, S. A., Beaufort, S., Bouajila, J., Souchard, J. P. & Taillandier, P. Understanding Kombucha tea fermentation: A review. J. Food Sci. 83, 580–588. https://doi.org/10.1111/1750-3841.14068 (2018).

Nyhan, L. M., Lynch, K. M., Sahin, A. W. & Arendt, E. K. Advances in Kombucha tea fermentation: A review. Appl. Microbiol. 2, 73–103 (2022).

Watawana, M. I., Jayawardena, N., Gunawardhana, C. B. & Waisundara, V. Y. Health, wellness, and safety aspects of the consumption of Kombucha. J. Chem. 2015 (591869). https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/591869 (2015).

Kapp, J. M. & Sumner, W. Kombucha: a systematic review of the empirical evidence of human health benefit. Ann. Epidemiol. 30, 66–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annepidem.2018.11.001 (2019).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank National Research Council of Thailand (NRCT), Research and Researchers for Industrial (RRI) Fund, the Department of Biology, Faculty of Science, the Graduate School, Chiang Mai University, Thailand. The Tea Gallery Group (Thailand) Co., Ltd. is also thoughtfully acknowledged.

Funding

This research was carried out with the support of the Teaching Assistant and Research Assistant (TA/RA) Scholarship, the Graduate School Chiang Mai University, Chiang Mai, Thailand. This project is funded by National Research Council of Thailand (NRCT) and Research and Researchers for Industrial (RRI) Fund, grant number N23G660002. Moreover, this research project was also funded by the Fundamental Fund 2025, Chiang Mai University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization was carried by N.C. and Y.T.; methodology was performed by N.C., T.K., V.I. and P.N.; formal analysis was corrected by N.C. and Y.T.; investigation and writing—original draft was prepared by N.C.; writing—review and editing were carried by N.C., T.K., S.S. and Y.T.; funding acquisition was provided by Y.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cheepchirasuk, N., Kaewkod, T., Suriyaprom, S. et al. Functional metabolites and inhibitory efficacy of kombucha beverage on pathogenic bacteria, free radicals and inflammation. Sci Rep 15, 19187 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03545-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03545-z

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Functional properties of hard kombucha brewed with deep ocean water using Lachancea thermotolerans

Scientific Reports (2025)