Abstract

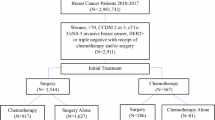

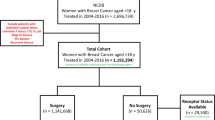

Current guidelines lack definitive recommendations on the use of chemotherapy for early-stage breast cancer in patients aged over 70. Clinical decision-making on chemotherapy for elderly breast cancer remains challenging because of insufficient large-scale, long-term outcomes. We conducted a retrospective cohort study using the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database from 2010 to 2020 to investigate early-stage breast infiltrating ductal carcinoma in patients aged 70 to 79. Propensity score matching (PSM) with a ratio of 1:1 and caliper of 0.02 standard deviation of propensity score was employed to address covariate imbalance. Univariate and multivariate analyses were performed to assess the impact of chemotherapy on breast cancer-specific survival (BCSS) and overall survival (OS). We identified a total of 11,792 patients with complete information about breast cancer, who underwent surgical treatment and received systemic therapy after surgery. Among them, 3,490 patients received chemotherapy. After PSM, we obtained a matched cohort consisting of 3,156 patients where the characteristics between the two groups were balanced except for molecular subtypes. In the matched dataset, no significant differences were observed in BCSS (P = 0.118) and OS (P = 0.119) between the two groups based on Kaplan–Meier survival analysis. Similarly, multivariate COX analysis revealed that chemotherapy did not significantly reduce the risk of BCSS (HR: 1.212; 95% CI: [0.958–1.533], P = 0.109) and OS (HR: 0.888; 95% CI: [0.765–1.031], P = 0.12). Stratified analyses based on molecular subtypes revealed that chemotherapy did not confer a favorable prognosis in patients with hormone receptor (HR)-positive, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2(HER2)-negative breast cancer in stages I and IIa, as well as in patients with HR+HER2+ breast cancer in stages I. Chemotherapy may not confer a discernible benefit for all elderly patients with breast cancer. Nevertheless, de-escalating chemotherapy could be considered as a preferable alternative for older individuals diagnosed with HR+HER2- breast cancer in stages I and IIa or HR+HER2+ breast cancer in stages I.

Similar content being viewed by others

According to the latest statistics, breast cancer ranks first among female malignant tumors1. However, as society ages, there is an increasing proportion of elderly patients with breast cancer2. Historically, due to the short survival expectancy of elderly patients, medical research has focused more on patients under 65 years of age. Consequently, clinical data on elderly patients are scarce compared to other age groups3. Concerns regarding the impact of chemotherapy on cardiac and hepatic function and advancements in endocrine and targeted therapies have resulted in a significantly lower utilization rate of chemotherapy among elderly patients compared to younger counterparts4,5,6. The clinical community has not reached a clear consensus regarding the survival benefits of adjuvant chemotherapy for older adults (aged ≥ 65 years) with early-stage breast cancer (stage I-II), particularly whether certain patients with favorable tumor characteristics could be safely spared chemotherapy without compromising outcomes.

The current study showed different results. A retrospective study using the US National Cancer Database showed that no statistically significant difference in median overall survival was found between the chemotherapy and no chemotherapy groups7. In contrast, a large-sample retrospective study based on the SEER database concluded that chemotherapy reduces the risk of OS by 36% and BCSS by 21%, respectively, after analyzing data on 8360 cases of breast cancer in older adults aged 70 years or older.8. Another study, also based on the SEER database, analyzed data from 32,734 patients aged 70 years or older and concluded that chemotherapy only significantly reduces mortality in older women with ER-negative and lymph node(LN)-positive breast cancer, and that women aged 70 years or older with lymph node-negative or estrogen-receptor-positive disease do not benefit significantly from adjuvant chemotherapy9. However, other studies have suggested that all HR-negative elderly breast cancer patients benefit from adjuvant chemotherapy, independent of LN status10. Two studies further analyzed the population of TNBC aged 70 years or older on the basis of HR-. Data from one of them supported chemotherapy11, while data from the other study suggested that patients with stage I TNBC should be exempted from chemotherapy12. Other studies have also shown that older breast cancer patients do not improve BCSS with chemotherapy and that more patients die from factors other than tumor13,14. These inconsistent findings create great difficulties in decision making for clinicians. Treatment choices also vary widely between centers and physicians15.

Recent reports suggest that by 2030, life expectancy will exceed 80 years per capita16, which has led to a substantial increase in the expected efficacy of chemotherapy. In addition, available data indicate that most elderly patients usually tolerate and respond well to conventional therapy17. For some elderly patients without comorbidities, forgoing chemotherapy can easily lead to inadequate treatment and poor cancer outcomes18. Current guidelines provide limited guidance on chemotherapy in elderly breast cancer patients. Therefore, there is an urgent need for more specific and precise evidence for adjuvant treatment options for elderly patients based on existing molecular typing of breast cancer19. So that those at high risk of recurrence can be adequately treated and those at low risk of recurrence can avoid the adverse effects of chemotherapy.

To answer these queries, we analyzed whether chemotherapy improves the prognosis of elderly patients with early-stage breast cancer using data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database from 2010 to 2020. We balanced the impact of factors other than chemotherapy on prognostic outcomes as much as possible by limiting the age range and pathology type and matching the molecular subtype, stage, tumor size and lymph node status of the two groups of patients by propensity score. And subgroup stratification was performed for the molecular subtypes and stages of tumors to explore the survival benefit of chemotherapy for elderly breast cancer patients under different subtypes and stages.

Study design

This was a retrospective cohort study using the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database. Data from 2010 to 2020 were used to assess BCSS and OS in early-stage elderly breast with and without chemotherapy.

Data sources and patient selection

Patient data were obtained from the SEER database (https://seer.cancer.gov/) using SEER*Stat 8.4.5 software. The SEER database captures approximately 28% of all tumor cases in the United States. Because the SEER database is publicly available, this study did not require informed consent from patients or institutional ethical review. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) women aged 70–79 years; (2) pathological diagnosis of invasive ductal carcinoma of the breast with a pathology code of 8500/3 in the SEER database; (3) surgical treatment without neoadjuvant therapy; (4) systemic therapy after surgery; (5) according to the criteria of the 8th edition of the AJCC for breast cancer: T stage ≤ 2, N stage ≤ 2, and the absence of distant metastases; (6) acquisition of only one malignant tumor. The exclusion criteria were: (1) tumor size smaller than 5 mm in diameter; (2) diagnosed with bilateral breast cancer; (3) missing key information, such as race, marital status, histological grade, lymph node status and molecular subtype; (4) death or loss to follow-up in 6 months after diagnosis.

Outcome indicators

Patients were categorized into chemotherapy and no-chemotherapy groups based on the codes in the SEER database Chemotherapy recode. BCSS was the first endpoint of the study and OS was the second endpoint of the study. BCSS was defined as the time from diagnosis of breast cancer to death due to breast cancer. OS was defined as the time from diagnosis of breast cancer until either death or censoring at last follow-up date. The follow-up period was from 1 January 2010 to 31 December 2020. For patients who remained alive at end-of-follow up period, the duration between disease diagnosis till end-of-study will be considered as their follow-up time. Lost-to-follow up patients’ follow -up times will be calculated starting from disease diagnosis till last contact.

Statistical analyses

The demographic and clinical characteristics of chemotherapy and no-chemotherapy cases in both the whole cohort and 1:1 propensity score-matched (PSM) groups were analyzed using the chi-square test. The Cox proportional hazards regression model was employed to calculate the hazard ratio (HR) along with its corresponding 95% confidence interval (CI), enabling identification of factors associated with outcomes. Variables that demonstrated a significance level of p < 0.05 in univariate analysis were included as candidate variables for multivariate analysis. Proportional hazards assumptions were assessed using the Schoenfeld residual test. To mitigate baseline differences in demographic and clinical characteristics, patients in the chemotherapy and no-chemotherapy groups underwent one-to-one matching through a PSM approach, incorporating age, race, marital status, grading, AJCC stage, ER status, PR status, HER2 status, surgical approach, and radiotherapy status as matched covariates. Nearest neighbor matching method with a caliper distance of 0.02 was utilized for this purpose. Survival curves were generated using the Kaplan–Meier method while statistical significance regarding differences in BCSS and OS between patients receiving chemotherapy versus those not receiving it was determined by means of log-rank tests. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software version 26 and R software version 4.4.3. P values less than 0.05 denoted statistical significance.

Result

Patient demographics and tumor characteristics

A total of 11,792 patients met the enrollment criteria, of whom 3,490 received chemotherapy after surgery and 8,302 did not. The median follow-up time was 83 months. Demographic and clinical case characteristics of the chemotherapy and no-chemotherapy groups are demonstrated in Table 1. Except for marital status, there were significant differences in age, ethnicity, tissue grading, tumor stage, molecular subtype, and treatment between the two groups. Patients in the chemotherapy group were younger, had higher histological tumor grades, larger tumor volumes, a greater number of lymph node metastases, a greater proportion of patients with types other than HR+/HER2-, and a higher proportion of those who underwent total mastectomy without radiotherapy.

Comparison of survival between chemotherapy group and no-chemotherapy group

The results of multifactorial statistical analysis using COX regression for both groups are presented in Table 2. Histological grading of the tumor, tumor size, and lymph node status were identified as influential factors impacting BCSS and OS outcomes. In terms of treatment modalities, the choice between surgery with or without breast-conservation did not significantly affect prognosis. However, radiotherapy was found to decrease BCSS in breast cancer patients, while chemotherapy reduced the risk of OS but did not improve BCSS. To ensure comparability between the two groups, a 1:1 propensity matching analysis was conducted with a caliper value of 0.02 resulting in 1578 matched pairs out of 3156 patients. Chi-square tests were performed on the matched dataset (Table 3), demonstrating that all factors except for slight differences in molecular subtype were well balanced between the two groups. Subsequently, another multifactorial statistical analysis using COX regression was carried out on the matched dataset which revealed that age increased the risk of non-tumor-related death among patients but had no impact on BCSS outcomes. Furthermore, it was observed that chemotherapy did not enhance either BCSS or OS rates in early-stage breast cancer patients (Table 4).

Survival analysis in propensity score matched

Kaplan–Meier survival analysis of the pre- and post-PSM datasets revealed that patients who did not receive chemotherapy in the pre-PSM dataset exhibited a more favorable prognosis compared to those who received chemotherapy. In the no-chemotherapy group compared with the chemotherapy group, the BCSS at 5 years was 97.99% versus 91.49%, and at 10 years was 96.71% versus 88.94%, P < 0.001. However, there was no significant difference in prognosis between patients who received chemotherapy and those who did not in the post-PSM dataset (Fig. 1). In the no-chemotherapy group versus the chemotherapy group, the BCSS at 5 years was 94.42% versus 98.35% and at 10 years was 91.69% versus 96.45%, P = 0.12.

The 95% confidence intervals (derived from simulated hazard estimates), the number of patients at risk at different time points, and the log-rank test for P are displayed on the graphs.

To account for potential confounding effects of molecular subtypes on study outcomes, we further stratified the patients into four subgroups based on their molecular subtypes and performed additional 1:1 propensity score matching analyses within each subgroup. Specifically, we successfully matched 1396 pairs in the HR+/HER2- subgroup, 282 pairs in the HR+/HER2+ subgroup. As demonstrated in Table 1, 98% of patients with HR-HER2- early breast cancer and 95% of patients with HR-HER2+ early breast cancer received chemotherapy. However, due to the limited number of patients who did not undergo chemotherapy, patient pairs following PSM did not provide adequate statistical power for reliable survival analyses. As seen in Fig. 2, chemotherapy benefits differently in different molecular subtypes of early-stage older breast cancer. Furthermore, in order to further investigate the effect of chemotherapy on the efficacy of patients with different stages who were in the HR+/HER2- and HR+HER2+ subgroups, patients in the respective paired datasets of HR+/HER2- and HR+HER2+ were stratified according to the different stages. Within each stratum, Kaplan–Meier survival analysis with breast cancer-specific death as a endpoint was then conducted (see Figs. 3 and 4). Notably from Figs. 3 and 4 is that stage I and II HR+/HER2- elderly breast cancer patients and stage I HR+/HER2+ elderly breast cancer did not derive additional survival benefit from adjuvant chemotherapy.

Discussion

We utilized multicenter, large-scale data from the SEER database to investigate the necessity of chemotherapy in early-stage elderly breast cancer patients, mitigating any bias caused by small-sample data from a single institution. Considering the current average life expectancy of 78–80 years and the potential impact of oncology treatment on patients over 70 years old with an estimated life expectancy of around 5 years, we specifically focused on patients aged 70–79 years. While many studies have set the age threshold for elderly patients at > 65 years, considering their life expectancy exceeding 15 years, it is recommended that this patient group undergo standard postoperative adjuvant treatment20. Additionally, we limited our analysis to patients with pure invasive ductal carcinoma to effectively eliminate confounding effects of different pathological tumor types on recurrence outcomes.

Our findings revealed that approximately 80% of older breast cancers belonged to the HR+HER2- subtype and chemotherapy did not confer any benefit in terms of BCSS for this specific patient subgroup, consistent with gene prognosis-related studies21. Although we regret our inability to obtain 21-gene scores for these elderly patients due to limitations in accessing this type of information in the SEER database, our survival analyses confirm that this particular group is exempt from chemotherapy without relying on gene score.

The majority of patients in this study (about 72.12%) opted for partial mastectomy, while approximately 64.49% received postoperative radiotherapy. A multifactorial statistical analysis revealed that radiotherapy had a significant protective effect on both OS and BCSS among elderly breast cancer patients. Previous studies have suggested an increased risk of cardiopulmonary disease associated with postoperative radiotherapy for breast cancer22. However, since 2000, there have been relatively few cardiac-related deaths reported in Asian or Pacific Islander populations after breast cancer treatment, attributed to advancements in radiotherapy techniques and equipment. Furthermore, the impact of postoperative radiotherapy on cardiac effects has not demonstrated significant significance23. In our study, we observed no significant association between radiotherapy and increased mortality risk in patients; instead, breast-conserving surgery combined with radiotherapy emerged as a preferable alternative to mastectomy.

Patients with HR-/HER2-type exhibited a significantly higher risk of mortality compared to those with the other three subtypes, both before and after matching. 98% patients with HR-/HER2-type received chemotherapy in this dataset. Consequently, there were insufficient matched pairs after propensity score matching (PSM) to draw corresponding conclusions for this particular subtype. However, an analysis conducted on 4696 early-stage HR-/HER2-type breast cancers in individuals aged over 70 years from the SEER database concluded that chemotherapy did not improve survival for stage I, T1N1M0 and grades I-II24. It is evident that not all patients within the HR-/HER2- type, which carries the worst prognosis, require chemotherapy. The remaining three subtypes had similar survival risks relative to the triple-negative subtype, suggesting that targeted therapies could reduce the recurrence rate in the HER2+ subgroup of patients, aligning with current findings25.

Previous studies have proposed divergent perspectives. A total of 11,735 cases of stage I-III breast cancer in the age range of 70–79 years between 2002 and 2012 were documented by Cancer Center UK, revealing that chemotherapy can enhance the Breast Cancer-Specific Survival (BCSS) among high-risk patients. Although the follow-up duration and case numbers were similar to our study, the previous article did not report data on ER or PR status. This discrepancy may be attributed to the reduced significance of chemotherapy in breast cancer treatment due to the increasing popularity of endocrine therapy and targeted therapy, resulting in different conclusions despite similar study designs but varying timelines18. A retrospective cohort study utilizing data from the SEER database involving 33,177 older breast cancer patients over 70 concluded that chemotherapy improved prognosis for all postoperative patients; however, survival curves for the chemotherapy and no-chemotherapy groups intersected at 72 months after surgery8. The proportion of stage III and HR-/HER2-type patients in the post-PSM cases exceeded 20% in this study, whereas their respective percentages were 5% and 1.6% in our study. Several current studies suggest that chemotherapy may provide greater benefits for HR-HER2- patients, while offering little benefit for HR+HER2- patients. Notably, the combination of CDK46 inhibitors and aromatase inhibitors has replaced chemotherapy as the first-line treatment for advanced breast cancer in HR+HER2- patients26,27. Therefore, further data analysis is warranted to delineate distinct treatment strategies for elderly patients with diverse molecular subtypes.

When formulating an antitumor regimen for elderly oncology patients aged 70–79 years, it is crucial to consider both the expected survival and the risk of off-tumor death. Cardiovascular accidents are the leading cause of mortality in this patient population28. Anthracycline-based chemotherapeutic agents and trastuzumab have been clearly shown to damage cardiac function29,30. However, in this study cardiac disease mortality was not significantly different between the two groups of patients, and the 3.53% (294/8332) cardiac disease mortality rate in the no-chemotherapy group was also slightly higher than that in the chemotherapy group at 3.17% (111/3500). Chemotherapy did not increase the risk of cardiac death in patients as expected. Our current privileges do not grant us access to specific dosing regimens for chemotherapy patients from the SEER database. We hypothesize that physician tend to avoid the use of cardiotoxic chemotherapeutic agents in older patients when choosing a treatment regimen. The use of pegylated liposomal doxorubicin, which is less cardiotoxic, instead of conventional anthracycline-based chemotherapy31,32 and the use of Docetaxel-based regimens instead of anthracycline-based regimens33,34 may explain the lack of difference in cardiac mortality between the two groups.

Although the SEER database was utilized to acquire a large-scale, multicenter, and standardized dataset of cases, it is important to acknowledge that retrospective studies inherently possess limitations which introduce unavoidable bias into the results. Despite our efforts to mitigate this bias through statistical methods such as PSM in order to match influential factors as closely as possible, there remains an inherent bias compared to randomized controlled trials. Furthermore, due to the limited availability of data on the HR-HER2+ and HR-HER2- subgroups after PSM, our study was unable to draw reliable conclusions for these specific subtypes. Further research findings are needed to determine whether patients belonging to these two categories can derive benefits from chemotherapy. Additionally, to minimize confounding factors, we specifically focused on invasive ductal carcinoma as the pathological subtype of breast cancer for this study, given its comparable prognosis to that of breast cancer overall. For histologic types with poorer prognoses, direct reference to the conclusions in this study may not be feasible. Instead, it necessitates the physician’s judgment based on a comprehensive evaluation of the patient’s condition and other relevant researches.

Conclusion

Chemotherapy may not be beneficial for all elderly breast cancer patients. However, oncologic outcomes were not affected by the exemption from chemotherapy for HR+/HER2+ elderly breast cancer patients in stage I and HR+/HER2- elderly breast cancer patients in stages I and IIa. By implementing more precise patient segmentation and tailored chemotherapy strategies, it is possible to optimize medical benefits while minimizing potential drawbacks.

Data availability

The data supporting the results of this study are available from the SEER database, but the availability of these data is limited because they were used with permission for this study and are therefore not publicly available. However, we can make these data available if the authors request and obtain permission from the SEER database.

Abbreviations

- PSM:

-

Propensity score matching

- BCSS:

-

Breast cancer-specific survival

- OS:

-

Overall survival

- HR:

-

Hormone receptor

- ER:

-

Estrogen receptor

- HER2:

-

Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2

- TNBC:

-

Triple-negative breast cancer

References

Bray, F. et al. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 74(3), 229–263. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21834 (2024).

Giaquinto, A. N. et al. Breast cancer statistics, 2022. CA Cancer J. Clin. 72(6), 524–541. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21754 (2022).

Freedman, R. A. et al. Accrual of older patients with breast cancer to alliance systemic therapy trials over time: Protocol A151527. J. Clin. Oncol. 35(4), 421–431. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2016.69.4182 (2017).

Muss, H. B. et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy in older women with early-stage breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 360(20), 2055–2065. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa0810266 (2009).

Hamelinck, V. C. et al. A prospective comparison of younger and older patients’ preferences for adjuvant chemotherapy and hormonal therapy in early breast cancer. Clin. Breast Cancer 16(5), 379–388. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clbc.2016.04.001 (2016).

Derks, M. G. M. et al. Impact of comorbidities and age on cause-specific mortality in postmenopausal patients with breast cancer. Oncologist 24(7), e467–e474. https://doi.org/10.1634/theoncologist.2018-0010 (2019).

Tamirisa, N. et al. Association of chemotherapy with survival in elderly patients with multiple comorbidities and estrogen receptor-positive, node-positive breast cancer. JAMA Oncol. 6(10), 1548–1554. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.2388 (2020).

Wu, Y. et al. Effect of adjuvant chemotherapy on the survival outcomes of elderly breast cancer: A retrospective cohort study based on SEER database. J. Evid. Based Med. 15(4), 354–364. https://doi.org/10.1111/jebm.12506 (2022).

Giordano, S. H., Duan, Z., Kuo, Y. F., Hortobagyi, G. N. & Goodwin, J. S. Use and outcomes of adjuvant chemotherapy in older women with breast cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 24(18), 2750–2756. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2005.02.3028 (2006).

Elkin, E. B., Hurria, A., Mitra, N., Schrag, D. & Panageas, K. S. Adjuvant chemotherapy and survival in older women with hormone receptor-negative breast cancer: Assessing outcome in a population-based, observational cohort. J. Clin. Oncol. 24(18), 2757–2764. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2005.03.6053 (2006).

Crozier, J. A. et al. Addition of chemotherapy to local therapy in women aged 70 years or older with triple-negative breast cancer: A propensity-matched analysis. Lancet Oncol. 21(12), 1611–1619. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30538-6 (2020).

Kozak, M. M., Xiang, M., Pollom, E. L. & Horst, K. C. Adjuvant treatment and survival in older women with triple negative breast cancer: A Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results analysis. Breast J. 25(3), 469–473. https://doi.org/10.1111/tbj.13251 (2019).

Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group (EBCTCG). Effects of chemotherapy and hormonal therapy for early breast cancer on recurrence and 15-year survival: An overview of the randomised trials. Lancet 365(9472), 1687–1717. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66544-0 (2005).

Bernardi, D. et al. Treatment of breast cancer in older women. Acta Oncol. 47(2), 187–198. https://doi.org/10.1080/02841860701630234 (2008).

Hurria, A. et al. Role of age and health in treatment recommendations for older adults with breast cancer: The perspective of oncologists and primary care providers. J. Clin. Oncol. 26(33), 5386–5392. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2008.17.6891 (2008).

GBD US Health Disparities Collaborators. Life expectancy by county, race, and ethnicity in the USA, 2000–19: A systematic analysis of health disparities. Lancet 400(10345), 25–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00876-5 (2022).

Schwartzberg, L. S. & Blair, S. L. Strategies for the management of early-stage breast cancer in older women. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. JNCCN 14(5 Suppl), 647–650. https://doi.org/10.6004/jnccn.2016.0182 (2016).

Ward, S. E. et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer in older women: An analysis of retrospective English cancer registration data. Clin. Oncol. 31(7), 444–452. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clon.2019.03.005 (2019).

Goldhirsch, A. et al. Strategies for subtypes–dealing with the diversity of breast cancer: Highlights of the St. Gallen International Expert Consensus on the Primary Therapy of Early Breast Cancer 2011. Ann. Oncol. 22(8), 1736–1747. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdr304 (2011).

Janeva, S. et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy and survival in women aged 70 years and older with triple-negative breast cancer: A Swedish population-based propensity score-matched analysis. Lancet Healthy Longev. 1(3), e117–e124. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2666-7568(20)30018-0 (2020).

Sparano, J. A. et al. Prospective validation of a 21-gene expression assay in breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 373(21), 2005–2014. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1510764 (2015).

Darby, S. C. et al. Risk of ischemic heart disease in women after radiotherapy for breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 368(11), 987–998. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1209825 (2013).

Jingu, K. et al. Recent postoperative radiotherapy for left-sided breast cancer does not increase mortality of heart disease in Asians or Pacific Islanders: SEER database analysis. Anticancer Res. 43(8), 3571–3577. https://doi.org/10.21873/anticanres.16535 (2023).

Huang, K., Zhang, J., Yu, Y., Lin, Y. & Song, C. The impact of chemotherapy and survival prediction by machine learning in early Elderly Triple Negative Breast Cancer (eTNBC): A population based study from the SEER database. BMC Geriatr. 22(1), 268. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-022-02936-5 (2022).

Perez, E. A. et al. Trastuzumab plus adjuvant chemotherapy for human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive breast cancer: Planned joint analysis of overall survival from NSABP B-31 and NCCTG N9831. J. Clin. Oncol. 32(33), 3744–3752. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2014.55.5730 (2014).

Gelmon, K. et al. Efficacy and safety of palbociclib in patients with estrogen receptor-positive/human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-negative advanced breast cancer with preexisting conditions: A post hoc analysis of PALOMA-2. Breast 59, 321–326. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.breast.2021.07.017 (2021).

Johnston, S. et al. MONARCH 3 final PFS: A randomized study of abemaciclib as initial therapy for advanced breast cancer. NPJ Breast Cancer 5, 5. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41523-018-0097-z (2019).

Ahmad, F. B. & Anderson, R. N. The leading causes of death in the US for 2020. JAMA 325(18), 1829–1830. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2021.5469 (2021).

Bhagat, A. & Kleinerman, E. S. Anthracycline-induced cardiotoxicity: Causes, mechanisms, and prevention. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 1257, 181–192. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-43032-0_15 (2020).

Dempsey, N. et al. Trastuzumab-induced cardiotoxicity: A review of clinical risk factors, pharmacologic prevention, and cardiotoxicity of other HER2-directed therapies. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 188(1), 21–36. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-021-06280-x (2021).

Gil-Gil, M. J. et al. Pegylated liposomal doxorubicin plus cyclophosphamide followed by paclitaxel as primary chemotherapy in elderly or cardiotoxicity-prone patients with high-risk breast cancer: Results of the phase II CAPRICE study. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 151(3), 597–606. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-015-3415-2 (2015).

Smorenburg, C. H. et al. A randomized phase III study comparing pegylated liposomal doxorubicin with capecitabine as first-line chemotherapy in elderly patients with metastatic breast cancer: Results of the OMEGA study of the Dutch Breast Cancer Research Group BOOG. Ann. Oncol. 25(3), 599–605. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdt588 (2014).

Jones, S. et al. Docetaxel with cyclophosphamide is associated with an overall survival benefit compared with doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide: 7-year follow-up of US Oncology Research Trial 9735. J. Clin. Oncol. 27(8), 1177–1183. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2008.18.4028 (2009).

Shulman, L. N. et al. Comparison of doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide versus single-agent paclitaxel as adjuvant therapy for breast cancer in women with 0 to 3 positive axillary nodes: CALGB 40101 (Alliance). J. Clin. Oncol. 32(22), 2311–2317. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2013.53.7142 (2014).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.S., Z.X. and W.J. contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by Y.L., X.T. and X.G. The first draft of the manuscript was written by C.S. and C.S. All authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, S., Zhou, X., Yang, L. et al. Long term efficacy of adjuvant chemotherapy in elderly patients with early stage breast cancer assessed through SEER database analysis. Sci Rep 15, 21609 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03592-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03592-6