Abstract

Few studies explored air pollution’s role in female infertility, especially with temperature factors. Investigating these effects is essential given global climate change and declining fertility rates. This retrospective study, conducted in Chengdu, China, included 1158 patients with primary infertility, 804 patients with secondary infertility, and 1809 fertile women who visited outpatient clinics between 2018 and 2023. Individual exposure levels to six air pollutants and temperatures were determined based on residential addresses. Multinomial logistic regression assessed the associations between air pollutants, temperature, and female infertility across five exposure windows (3–36 months before diagnosis). A stratified analysis by age was performed, and the interactions and combined exposure effects were further evaluated. Exposure to NO2 during 6 and 24 months before diagnosis was associated with a higher risk of primary infertility [OR (95% CI) = 1.17 (1.06–1.28); 1.08 (1.03–1.14)], exposure to PM10 during 24 months before diagnosis was associated with a higher likelihood of primary infertility (OR = 1.32 [1.04–1.57]). Exposure to PM2.5 during the 3 months before diagnosis had a higher risk of secondary infertility (OR = 1.32 [1.08–1.56]), as well as during the 36 months before diagnosis (OR = 1.08 [1.01–1.13]). PM10 exposure during the 3 months, 12, and 36 months before diagnosis (OR = 1.09 [1.01–1.17]; 1.21 [1.05–1.38]; 1.14 [1.03–1.23]), was associated with a higher risk of secondary infertility. Higher temperature exposure in the 3 months before diagnosis was associated with a lower risk of both primary and secondary infertility [OR = 0.92 (0.85–0.96); 0.91 (0.83–0.95)]. Women under 32 years of age exhibited increased sensitivity to NO2, CO, and temperature exposure. Additionally, co-exposure to low temperatures and high concentrations of SO2 or NO2 heightened the risk of primary infertility during the 3 months before diagnosis [OR = 1.86 (1.12–3.04); 1.62 (1.13–2.33)]. Co-exposure to low temperatures and high concentrations of PM10 increased the risk of secondary infertility during 3, 12, and 36 months before diagnosis [OR = 1.51 (1.13–2.03); 1.48 (1.07–2.21); 1.71 (1.13–2.52)]. This study emphasizes the potential for mitigating female infertility risk through reduced exposure to NO2, PM10, and PM2.5, and by appropriately adjusting environmental temperatures.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Infertility is defined as the inability to achieve pregnancy after one year or more of regular, unprotected intercourse, with this period shortened to 6 months for women aged 35 years and above1. Based on pregnancy history, infertility is categorized into two major types: primary and secondary. Primary infertility was defined as infertility in women who had not previously been pregnant, while secondary infertility referred to women with a prior pregnancy who subsequently experienced infertility2. The global lifetime prevalence of infertility is approximately 17.5%3. In China, around 25% of women attempting to conceive have experienced infertility4. Given the high prevalence of female infertility and the unique challenges it poses to reproductive health interventions, this issue has garnered significant research attention.

Most cases of infertility in women can be attributed to organic diseases or functional reproductive disorders, such as endometriosis, diminished ovarian reserve, and tubal or pelvic diseases5. However, many cases remain unexplained, even in the absence of any diagnosed physiological or pathological basis6. Epidemiological and animal studies suggest that environmental factors, particularly air pollution, may contribute significantly to unexplained infertility cases7.

Previous studies have reported the adverse effects of air pollution on various aspects of female reproductive health, including pregnancy outcomes8, birth outcomes9, miscarriage rates10, and ovarian function11. A negative correlation exists between human fertility and increased air pollution exposure12. To date, only two studies have directly examined the association between air pollutants and human infertility. These studies indicate that exposure to particulate matter across all size fractions and traffic-related air pollution are associated with a higher incidence of infertility13, with exposure to PM2.5 linked to a 20% higher likelihood of infertility14. Three additional studies on the same topic have examined the effects of air pollution on fertility15,16,17. These studies provide further evidence of the impact of air pollution on reproductive health, indicating that both long-term and short-term exposures to air pollutants may reduce fecundability. Collectively, they support the crucial premise that when investigating the effects of pollutants on infertility risk, it is essential to consider the temporal characteristics of pollution exposure. Additionally, air pollution appears to accelerate reproductive aging, being associated with both earlier menarche and earlier menopause, potentially shortening the reproductive lifespan in women18,19.

In addition to air pollution, temperature is a crucial environmental factor that has garnered increasing attention in epidemiology, public health, and environmental sciences. Several studies have revealed that ambient temperature profoundly impacts human fertility, with these effects potentially extending into subsequent generations20. Prolonged exposure to extreme heat may impair the human reproductive system, affecting ovarian function and ovulation cycles and consequently leading to adverse outcomes for female reproductive health21. Pregnant women are particularly susceptible to the effects of temperature changes22. Exposure to extreme heat has been linked to declining fertility rates after nine months23. However, to the best of our knowledge, few studies have specifically examined the association between ambient temperature and human infertility24. Recent research has begun to explore related aspects, such as the influence of temperature on ovarian reserve and outcomes following ovarian stimulation and IVF25.

Temperature variations not only impact an individual’s physical health but may also exacerbate the adverse effects of air pollutants by altering the body’s sensitivity. Limited evidence on the interaction between temperature changes and air pollutants has primarily focused on respiratory diseases26, overall population mortality27,28, infectious diseases29, and cardiovascular health30. For example, co-exposure to high temperatures and air pollution during the prenatal and postnatal periods increases the risk of asthma in early childhood26. A study conducted in Germany and Portugal demonstrated that the interaction between air pollutants such as O3 and PM10 and high temperatures led to increased population mortality26,31. Most studies on environmental exposure and infertility have primarily focused on the isolated effects of air pollution. Given that fluctuations in air pollution and temperature often occur simultaneously and may have complex interactions, it is crucial to investigate their potential joint effects on female infertility.

In addition, a large number of studies have highlighted the important impact of age on female fertility32. Given that female fertility naturally declines with age, particularly after the age of 3233, stratifying by age allows for a better understanding of how environmental exposures interact with age-related changes in reproductive health. Comparing the effects of air pollution and temperature across two distinct age groups, provides a clearer insight into how these factors may influence infertility risk at different stages of life. Based on medical records from a gynecology hospital, this retrospective study was conducted in Chengdu, a megacity in China (population: 21.4 million), to assess the independent and joint associations between air pollutants, temperature, and female infertility.

Materials and methods

Study sample

This study collected personal information, pregnancy history, and gynecological diagnostic data from women of reproductive age who visited Chengdu Women’s and Children’s Central Hospital between May 2018 and December 2023. Personal information included detailed residential addresses (down to street and community levels), age, height, weight, and date of diagnosis. Gynecological diagnoses included infertility, polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), tubal and pelvic diseases, endometriosis, and uterine fibroids, while pregnancy information included pregnancy, delivery, and miscarriage histories. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Chengdu Women’s and Children’s Central Hospital [Ethics Approval No. 2023(129)]. All data used in this study were fully anonymized, and participants provided informed consent. The data collection, analysis, and methodological execution of this study adhered to the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and the Ethical Review Measures for Biomedical Research Involving Humans, issued by the former National Health and Family Planning Commission of the People’s Republic of China in 2016. Additionally, the study complied with the relevant laws and regulations of China.

To refine the sample, we first excluded 809 women residing outside Chengdu’s administrative boundaries and 413 women with missing personal information, diagnostic data, or pregnancy history from the initial pooled sample (5314 cases). The inclusion criteria for infertility cases were as follows: (1) infertility clinically diagnosed as female-factor infertility, and (2) age between 20 and 42 years. A total of 3505 eligible women with infertility were included. Subsequently, we excluded 370 cases of infertility following in vitro fertilization (IVF) and two cases of tubal ligation. Women diagnosed with any of the following gynecological conditions were also excluded to control organic or functional infertility: (1) PCOS (235 cases); (2) tubal or pelvic diseases, including blockages, adhesions, hydrosalpinx, and ovulation disorders (204 cases); (3) ovarian dysfunction (114 cases); (4) endometriosis (384 cases); and (5) uterine fibroids (234 cases).

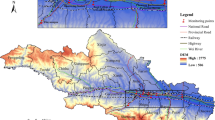

Fertile patients included women who visited outpatient clinics during the same period. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) normal sexual activity and a history of spontaneous pregnancy or childbirth, (2) no history of infertility or related chief complaints, and (3) age between 20 and 42 years. Ultimately, 3771 valid female samples were included in the study, consisting of 1158 cases of primary infertility, 804 cases of secondary infertility, and 1809 fertile women. The distribution of samples across different areas of Chengdu is shown in Fig. 1, with most participants residing in central Chengdu (3418 women, 90.64%).

Air pollutants and temperature exposure

This study first collected data from the National Urban Air Quality Real-time Publishing Platform of the China National Environmental Monitoring Centre (https://air.cnemc.cn:18007/) on the 24-hour average concentrations of SO2, PM10, NO2, CO, PM2.5, and the 8-hour rolling average of O3 across monitoring stations in Chengdu from January 2017 to December 2023. The monthly average concentrations of each pollutant were aggregated and calculated. We used the inverse distance weighting (IDW) method of spatial interpolation to project data from the monitoring stations (locations shown in Fig. 1) onto the entire study area with a spatial resolution of 100 m × 100 m to estimate the monthly pollutant exposure levels at each participant’s residence10,34. In this process, we utilized the Baidu Maps application interface (https://lbsyun.baidu.com/products/search) to match the geographic coordinates and convert each participant’s specific residential address into spatial coordinates.

In this study, monthly temperature data for each sample were extracted from the 1-km monthly mean temperature dataset for China (1901–2023) published by35 and available from the National Tibetan Plateau/Third Pole Environment Data Center (https://data.tpdc.ac.cn/home). This dataset, based on the 30′ Climatic Research Unit time-series dataset and the high-resolution climatology dataset released by WorldClim, was created using the delta spatial downscaling approach to produce monthly temperature data for China. Its reliability has been validated using data from 496 meteorological observation stations nationwide.

Since the specific effects of air pollutants and temperature during different exposure periods on infertility remain unclear13,14, this study calculated the monthly moving average levels of pollutants and temperature for each participant during five different exposure windows based on the date of diagnosis to comprehensively assess the effects of individual exposure in both the short and long term. The five exposure windows were 3 months prior to diagnosis (period 1), 6 months prior (period 2), 12 months prior (period 3), 24 months prior (period 4), and 36 months prior (period 5).

Covariates

Referring to previous studies4, we included covariates, such as body mass index (BMI), age, employment status, ethnicity, residential region, and history of miscarriages. In addition, we considered surrounding greenness (measured by the monthly normalized difference vegetation index, [NDVI]), traffic conditions (distance from the main road), and meteorological conditions (monthly rainfall) as covariates, as these factors may be closely related to an individual’s exposure to pollutants or temperature13,36. Moreover, socioeconomic conditions related to place of residence, including community housing prices, building age, surrounding population density, and gross domestic product (GDP) per square kilometer, were also included as background covariates.

Specifically, we obtained 250 m high-resolution NDVI data from the MOD13A3 dataset regularly released by the US National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) (https://lpdaac.usgs.gov/products/mod13q1v006/)37. After processing, NDVI values ranged from − 1 to 1, with values closer to 1 indicating higher vegetation coverage. Traffic conditions were assessed using ArcGIS 10.8 to calculate each participant’s distance to the nearest main roads, including major, secondary, elevated, expressways, and branch roads. Road network data were sourced from OpenStreetMap (https://www.openstreetmap.org). Monthly rainfall data were obtained from the same source as the temperature data, with NDVI and rainfall exposure levels calculated for each exposure window in alignment with air pollutant data. Community housing prices and building age data for residential areas were sourced from the Anjuke platform (https://chengdu.anjuke.com/), where the average values of community housing prices and building ages were calculated within a 100 × 100 m grid. Population density data were derived from the 100 m gridded spatial dataset from China’s seventh national census published by38 (https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.24916140.v1). GDP data were sourced from 2020 raster data at a 1-km resolution, representing the spatial distribution of GDP within the study area39, downloaded from the Geographic Data Sharing Infrastructure, Global Resources Data Cloud (http://www.gis5g.com). Based on existing studies, we created a 500 m radius buffer around each participant’s residence to extract the average values of NDVI, community housing prices, building age, population density, and GDP40.

Statistical analysis

The independent-sample t-tests (for continuous variables) and chi-square tests (for categorical variables) were first used to analyze differences in characteristics between the groups. Pearson’s correlation analysis evaluated the correlation between air pollutants and temperature exposure among the samples. Subsequently, multinomial logistic regression models were employed to investigate the associations between ambient air pollutants, temperature exposure, and female infertility (fertility = 0, primary infertility = 1, secondary infertility = 2). The models were used to calculate odds ratios (ORs), 95% confidence intervals (CIs), and p values. The model for each category of infertility (Yk) can be expressed as:

In the model, P(Y = k) represents the probability of the outcome Y being in category k, where k corresponds to different infertility types. β0 is the constant term, βi are the coefficients for the predictors (pollutants and temperature), and Xi denotes the air pollutants and temperature exposure variables. The interaction term Xi·Z captures the combined effect of air pollutants and temperature, and ε is the error term.

To further explore the differences across subgroups, we conducted stratified analyses based on age (< 32 years and ≥ 32 years). The interaction effects of air pollutants and temperature exposure were assessed by adding interaction terms (product terms) for each air pollutant and temperature to the models and testing for statistical significance41. Further analyses categorized exposure levels into low and high groups based on the 50 th percentiles of pollutant concentration and temperature within each exposure window, creating new variables. Samples with low exposure levels for both air pollutants and temperature served as the reference group, and detailed analyses were conducted on the joint effects of different exposure combinations42. In the final models, the following covariates were adjusted: age (< 32 and ≥ 32), BMI, employment status (employed and unemployed), ethnicity (Han and others), residential region (Central area and Non-central area), history of miscarriage (with and without a history of miscarriage), NDVI, distance from the main road (< 100 m and ≥ 100 m), rainfall, community housing price, building age, surrounding population density, and GDP per km².

All statistical analyses were conducted using Stata 18.0, and spatial calculations were performed using ArcGIS 10.8. R version 4.4.1 was utilized to (1) convert all residential address information into spatial coordinates; and (2) calculate the monthly moving averages of pollutant concentrations, temperatures, NDVI, and rainfall for each exposure window. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

The following sensitivity analyses were conducted to assess the robustness of the model results: (1) running two multinomial logistic regression models, with the second model excluding patients who had experienced miscarriages (both induced and spontaneous) to evaluate the stability of the main effects; (2) performing the stratified analysis was conducted according to age (< 32 years and ≥ 32 years).

Results

Characteristics of the study population

The characteristics of the samples are listed in Table 1. The average age of the overall sample was 31.45 years. Compared to the primary infertility group, the secondary infertility group had a higher average age [32.82 (3.95) vs. 30.75 (3.58)] and BMI [21.32 (2.93) vs. 20.93 (2.73)]. As expected, the number of pregnancies [0.00 (0.00) vs. 1.82 (1.11)] and live births [0.00 (0.00) vs. 0.32 (0.50)] in the primary infertility group were zero, differing from the secondary group. The proportion of employed individuals was greater in the primary infertility group, and a larger proportion of women in this group reported a history of miscarriage [219 (18.91%) vs. 309 (38.43%)]. No marked differences were observed between groups in terms of ethnicity, residential region, distance to the main road, housing price, building age, GDP per km², NDVI, population density, or rainfall.

The exposure levels to each type of pollutant and temperature for the total sample across different exposure windows are presented in Table 2. Correlation tests indicated that exposure to temperature and the six types of air pollutants in the sample were significantly correlated from 2018 to 2023 (Table S1).

Associations of ambient air pollution and temperature exposure with infertility

The results of the multinomial logistic regression, adjusted for all confounding factors, are presented in Table 3. The study found that women exposed to SO2 during the 3 months prior to diagnosis had a significantly higher risk of primary infertility [OR (95% CI) = 1.31 (1.13 − 1.64)]. Similarly, women exposed to NO2 during the 6 and 24 months prior to diagnosis showed an increased risk of primary infertility [OR (95% CI) = 1.17 (1.06–1.28); 1.08 (1.03–1.14)]. Exposure to PM10 in the 24 months prior to diagnosis was associated with a higher likelihood of primary infertility [OR (95% CI) = 1.32 (1.04–1.57)]. For secondary infertility, women exposed to PM2.5 during the 3 months prior to diagnosis had a significantly higher risk [OR (95% CI) = 1.32 (1.08–1.56)], as well as during the 36 months prior to diagnosis [OR (95% CI) = 1.08 (1.01–1.13)]. Additionally, PM10 exposure during the 3 months [OR (95% CI) = 1.09 (1.01–1.17)], as well as during the 12 [OR (95% CI) = 1.21 (1.05–1.38)] and 36 months [OR (95% CI) = 1.14 (1.03–1.23)] prior to diagnosis, were all associated with an increased risk of secondary infertility. Regarding ambient temperature, exposure during the 3 months prior to diagnosis was associated with a lower risk of both primary [OR (95% CI) = 0.92 (0.85–0.96)] and secondary infertility [OR (95% CI) = 0.91 (0.83–0.95)].

After excluding samples from women who had experienced miscarriages, the overall trends remained largely consistent (Table S2). Increased exposure to PM10 [OR (95% CI) = 1.04 (1.01–1.11); 1.22 (1.07–1.44)] and NO2 [OR (95% CI) = 1.04 (1.02–1.08); 1.18 (1.04–1.33)] during the 6 and 24 months prior to diagnosis was still significantly associated with an elevated risk of primary infertility. However, the association between SO2 exposure and risk of primary infertility was no longer significant. For secondary infertility, increased exposure to PM2.5 (during the 3, 24, and 36 months prior to diagnosis) and PM10 (during the 3, 12, and 36 months prior) was significantly associated with elevated risk. Similarly, significant associations between temperature exposure and both primary and secondary infertility were observed during the 3 months prior to diagnosis.

The results of the age-stratified analysis (stratified by the age of 32 years) are shown in Fig. 2. Overall, the regression results for both age groups were similar to those of the main-effects model (Table 3). However, we observed that women under 32 years demonstrated greater sensitivity to NO2, CO, and temperature exposure concerning infertility risk. Specifically, women younger than 32 had a significantly higher risk of primary infertility when exposed to CO during the 24 and 36 months prior to diagnosis [OR (95% CI) = 1.29 (1.11–1.49); 1.04 (1.01–1.11)]. Exposure to NO2 during the 6 and 24 months prior to diagnosis was also significantly associated with a higher risk of primary infertility [OR (95% CI) = 1.08 (1.02–1.15); 1.08 (1.01–1.17)]. Additionally, among women under 32, exposure to temperature during the 3 and 24 months prior to diagnosis was significantly associated with an increased risk of primary infertility [OR (95% CI) = 1.04 (1.01–1.09); 1.20 (1.08–1.34)]. Similarly, exposure to temperature during the 3 months prior to diagnosis was significantly associated with an elevated risk of secondary infertility [OR (95% CI) = 1.05 (1.02–1.10)]. In contrast, among women over 32, no significant associations were observed between CO, NO2, or temperature exposure and the risk of infertility in any exposure window. Furthermore, significant associations between PM2.5, PM10, and SO2 exposure and infertility risk were observed in both age groups across the relevant exposure windows.

Association between exposure to air pollutants and temperature and infertility in female subgroups aged above 32 (blue) and below 32 (orange). The dots indicate odds ratios, and the lines are the corresponding 95% confidence intervals. Asterisks indicate significant results: * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001. T refers to temperature. The model adjusted for covariates, including BMI, ethnicity, employment status, residential region, history of miscarriage, normalized difference vegetation index, distance from the main road, rainfall, community housing prices, building age, surrounding population density, and gross domestic product per square kilometer.

The interaction effects of air pollutants and temperature on infertility

The overall interaction effects across these windows are shown in Table S3. During the 3 months prior to diagnosis, the interaction between NO2 and temperature was significantly associated with a slight reduction in the risk of primary infertility [OR (95% CI) = 0.98 (0.93–0.99)]. Additionally, interactions between PM10 and temperature during the 3- and 12-month periods before diagnosis were significantly associated with a slight reduction in the risk of secondary infertility [OR (95% CI) = 0.97 (0.91–0.99); 0.93 (0.80–0.98)].

Further analyses assessed the joint effects of six air pollutants and temperature on infertility risk based on combined exposure levels; the results are presented in Fig. 3. Compared to other combinations, women co-exposed to high concentrations of SO2 or NO2 along with low temperatures during the 3 months prior to diagnosis had the highest risk of primary infertility [OR (95% CI) = 1.86 (1.12–3.04); 1.62 (1.13–2.33)]. Regarding secondary infertility, women co-exposed to high concentrations of PM10 and low temperatures during the 3-month, 12-month, and 36-month periods prior to diagnosis had the highest risk [OR (95% CI) = 1.51 (1.13–2.03); 1.48 (1.07–2.11); 1.71 (1.13–2.52)]. After excluding women with a history of miscarriage, the results remained relatively robust (Table S4 and Table S5). In the 3 months prior to diagnosis, women who were simultaneously exposed to high concentrations of SO2 or NO2 and low temperatures still had the highest risk of primary infertility [OR (95% CI) = 2.39 (1.37, 4.59); 2.34 (1.41, 3.77)]. In the 12 and 36 months prior to diagnosis, women simultaneously exposed to high concentrations of PM10 and low temperatures still had the highest risk of secondary infertility [OR (95% CI) = 1.62 (1.10, 2.68); 1.72 (1.31, 2.92)].

Joint effect of air pollutants and temperature on primary infertility (a) and secondary infertility (b). The black squares represent odds ratios, and the lines are the corresponding 95% confidence intervals. Red text with asterisks indicates significant results: * p < 0.05 ** p < 0.01 *** p < 0.001. Odds ratios, confidence intervals, and P-values were estimated by continuous increments in pollutant and temperature levels. The model adjusted for all covariates, including age, BMI, ethnicity, employment status, residential region, history of miscarriage, normalized difference vegetation index, distance from the main road, rainfall, community housing prices, building age, surrounding population density, and gross domestic product per square kilometer.

Discussion

With the ongoing challenges of global climate change and declining fertility rates, understanding the relationship between environmental exposures and infertility among women has become critical in epidemiology, environmental science, and public health. This retrospective cohort study aimed to examine the associations between exposure to ambient air pollutants and temperature and the risks of primary and secondary infertility in women considering both short- and long-term periods (ranging from 3 months to 3 years before diagnosis). This study explored associations between multiple ambient air pollutants exposures and female infertility across different exposure periods. The findings reveal some pollutant- and time-specific patterns, as well as possible interactions with temperature.

The study found that both short-term (within 1 year prior to diagnosis) and long-term (2 years or more prior to diagnosis) exposure to PM10 and NO2 were significantly associated with a higher risk of primary infertility, while exposure to PM2.5 and PM10 was significantly associated with an increased risk of secondary infertility. These findings align with existing research on the relationship between air pollution and infertility13,14 or fertility outcomes15,16,17. In a cohort study of pregnancy planners, Wesselink et al. (2022) observed that exposure to PM2.5 and PM10 was linked to reduced fertility17. Similarly, Li et al. (2021) reported that with every 10 µg/m3 increase in PM2.5 exposure, the likelihood of infertility increased by 20%14. Mahalingaiah et al. (2016) also identified associations between exposure to PM2.5, PM2.5–10, PM10, and traffic-related air pollution with infertility risk13. Their study reported significant associations between these pollutants and infertility across the overall sample, while no heterogeneity was found in the association between air pollutants and infertility in the subdivided primary and secondary infertility groups13. In contrast, our study found differing results in these subgroups, which may be attributed to differences in study design, such as the inclusion of additional pollutants (NO2, CO, O3, and SO2) in our analysis, and differences in exposure levels. For example, the 2-year mean PM2.5 exposure value for the sample in Mahalingaiah et al.’s study was 14.5 µg/m3, compared to 41.80 µg/m3 in our study (Table 2).

Although the biological mechanisms by which air pollutants impact female infertility are not fully understood, compelling evidence suggests that PM2.5, PM10, and NO2 are strongly associated with reproductive health issues12,43. PM2.5 and PM10 are inhalable particles suspended in the air, while NO2 primarily originates from vehicle exhaust and industrial emissions. These pollutants can trigger chronic inflammation, endocrine disruption, and oxidative stress44, which may impair follicular development and ovulation, consequently affecting female fertility45. It is important to note that our study excluded women with diagnosed gynecological conditions such as PCOS, endometriosis, or uterine fibroids to minimize the impact of organic or functional infertility and better isolate associations with environmental exposures. Nonetheless, subclinical inflammation, oxidative stress, or hormonal dysregulation could still contribute to infertility in women without overt diagnoses. For instance, ambient pollutants may impair endometrial receptivity or interfere with oocyte quality even in women without diagnosed reproductive disorders46. In addition, women who had never been pregnant appeared more susceptible to ambient exposure of PM10 and NO2 (Table 3). We hypothesize that, due to its smaller particle size, PM2.5 can penetrate deeper into the microcirculation of the reproductive system, potentially making it more challenging for previously pregnant women to conceive again8.

Contrary to our hypothesis and previous studies suggesting that higher temperatures increase infertility risk21,47, we observed that higher temperature exposure was significantly associated with a reduced risk of both primary and secondary infertility, particularly during short-term exposure (within 3 months prior to diagnosis) (Table 3). This finding indicates that short-term exposure to higher temperatures may have a protective effect against infertility. One possible explanation is that, in regions like Chengdu—which is characterized by a mild, humid climate with an average annual temperature of around 16 °C, high relative humidity (~ 80%), and limited sunshine48—moderate warming may help alleviate cold-related physiological stress, improve peripheral circulation, and enhance reproductive function. A moderate rise in temperature may improve circulation and metabolic function, potentially benefiting reproductive health and fertility. Based on our findings, we propose that there may be a threshold effect of temperature on infertility, suggesting that local climate conditions should be considered when interpreting these results. The study by Jensen et al. (2021) offers valuable reference, demonstrating that elevated temperatures negatively impact fertility when monthly maximum temperatures exceed 15–20 °C, while moderate temperature increases in colder climates may improve fertility outcomes20.

In addition, our findings suggest that the associations between ambient air pollutants and infertility vary by exposure window, indicating that both timing and duration of exposure may modify environmental effects on reproductive health. This temporal heterogeneity could reflect distinct biological processes. Short-term exposures (e.g., within 3 months) may predominantly affect functional aspects such as ovulation or implantation through transient inflammatory responses15. Long-term exposures (e.g., 2–3 years) might influence structural or cumulative outcomes like ovarian reserve depletion11. These patterns align with existing evidence that acute and chronic pollution exposures operate through different pathways49, though our study design cannot confirm specific mechanisms. Future research should prioritize defining exposure windows based on reproductive biology (e.g., folliculogenesis periods). Additionally, unmeasured early-life or in utero exposures may affect long-term associations, as air pollution has been shown to impair the development of fetal germ cells—an issue not addressable in our study50.

In this study, we observed that women under the age of 32 exhibited heightened sensitivity to the risk of infertility due to exposure to NO2, CO, and temperature. This finding is consistent with the results of previous studies51,52, which may be related to physiological differences and reproductive health status. The reproductive system of younger women tends to be more active and sensitive53, making them more susceptible to the effects of environmental factors such as air pollution and temperature compared to older women. Younger women also experience greater fluctuations in hormone levels, and their immune systems may respond more intensely to environmental pollutants, thereby increasing the risk to their reproductive health54. Moreover, as young women are typically in the early stages of their reproductive years and are less likely to have experienced fertility-related health issues, environmental factors may have a more pronounced impact on their fertility when no other health problems are present55.

Notably, our study revealed the interaction of combined exposure to air pollution and low temperatures on the risk of female infertility. Although substantial evidence suggests that interactions between temperature fluctuations, including low temperatures, and air pollutants may pose health risks or increase the likelihood of disease27,28, to the best of our knowledge, no epidemiological studies have specifically explored the interaction effects of air pollution and temperature on infertility. Our findings are supported by another study conducted in Chengdu, which showed that the interaction between PM2.5, PM10, and SO2 at low temperatures increased the risk of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, with the highest attributable fraction occurring under low-temperature conditions56. The temperature and air pollutant levels in their study were similar to those in the present study. Furthermore, a study conducted in the cold climate of Lanzhou, China, found that the impact of PM10, SO2, and NO2 on hospital admissions for respiratory diseases was more pronounced on cold days than on warmer days57.

From environmental and biological perspectives, the synergistic effect between low temperatures and high concentrations of air pollutants can be explained by several mechanisms, all of which may help mitigate the negative effects of air pollution on fertility and lower the risk of infertility. First, higher temperatures can reduce cold stress responses in the body, helping to maintain hormonal balance and reproductive function20. In contrast, air pollution may exacerbate cold stress by impairing respiratory and cardiovascular function, particularly in colder environments where pollutants tend to accumulate58. Thus, the combination of low temperatures and high pollution levels may amplify stress responses, whereas higher temperatures may mitigate these effects. Second, while warmer climates may encourage outdoor activities, which can enhance metabolism and immunity59, increased outdoor exposure in polluted environments may also elevate inhalation of harmful pollutants60. Therefore, the interaction between temperature and air pollution is crucial: higher temperatures may improve air quality through better pollutant dispersion61, reducing the risk of exposure during outdoor activities, particularly in urban areas where cold weather often traps pollutants near the ground62.

Our study has several limitations. First, estimating individual exposure levels based on the spatial matching of patients’ home addresses may introduce bias because we lacked information on the home-living environment, time spent at home, and occupational exposure. Similar to many other studies51,63, the IDW method was used to estimate the pollutant concentrations in the study area, which may have led to spatial inaccuracies in the exposure estimates. Second, this study used the diagnosis date as the starting point for each exposure period; however, there may be a time lag between the actual onset of infertility and the patient’s hospital diagnosis, which may affect the accuracy of the exposure window classification. Third, although our study assessed exposure windows of up to 36 months prior to diagnosis to capture relatively short- and medium-term effects, it did not account for early-life or in utero exposures. Given the potential links between such exposures and reproductive health, this represents a limitation of our analysis. Notably, the study period included the COVID-19 pandemic, during which increased stress levels may have negatively affected female fertility. However, psychosocial stress was not directly measured, and this unmeasured confounder may have influenced the observed associations. Fourth, the data were derived from medical records, limiting access to detailed individual-level information, such as smoking habits and personal income. Finally, this study did not distinguish seasonal temperature variations, which may have limited the interpretation of the temperature effects. Our model treated temperature as a continuous linear variable, which may have limited its ability to capture the nonlinear effects of extreme cold and heat. Future studies should consider nonlinear or threshold-based temperature modeling to better understand its impact on fertility.

Conclusion

This retrospective study conducted in the Chinese megacity of Chengdu contributes to the limited understanding of the association between air pollution, temperature factors, and female infertility. This exploration is crucial, given the growing challenges of global climate change and declining fertility rates. The findings revealed that exposure to PM10 and NO2 was associated with an increased risk of primary infertility, while exposure to PM10 and PM2.5 was linked to secondary infertility. In contrast, exposure to high temperatures was associated with a reduced risk of infertility. Furthermore, women under the age of 32 were found to be more sensitive to air pollutants and temperature changes. This study also highlighted a synergistic effect between air pollution and low-temperature exposure, which increased the risk of female infertility. These findings emphasize the importance of women avoiding exposure to harmful air pollutants (mainly PM2.5, PM10, and NO2) and adjusting ambient temperatures under appropriate conditions to reduce infertility risk. These results provide a foundation for the development of effective preventive measures. We recommend that the government, along with meteorological and environmental protection agencies, strengthen air pollution monitoring under varying temperature conditions and promptly issue relevant forecasts or warnings, particularly for vulnerable populations, to mitigate infertility risk. Future research using prospective cohort studies is essential to confirm the causal relationship between ambient exposure and infertility. In addition, it is crucial to explore the biological mechanisms by which ambient exposure contributes to infertility. Targeted investigations into specific toxicants such as black carbon particles and volatile compounds from paint may provide deeper insights into biologically relevant exposures.

Data availability

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

References

WHO & Infertility https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/infertility

Zegers-Hochschild, F. et al. The international glossary on infertility and fertility care, 2017. Hum. Reprod. 32, 1786–1801. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/dex234 (2017).

WHO. Infertility prevalence estimates, 1990–2021. World Health Organization (2023).

Zhou, Z. et al. Epidemiology of infertility in China: a population-based study. Bjog: Int. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 125, 432–441. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.14966 (2018).

Carson, S. A. & Kallen, A. N. Diagnosis and management of infertility: a review. Jama-J Am. Med. Assoc. 326, 65–76. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2021.4788 (2021).

Raperport, C. et al. The definition of unexplained infertility: a systematic review. Bjog: Int. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 131, 880–897. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.17697 (2024).

Checa Vizcaíno, M. A., González-Comadran, M. & Jacquemin, B. Outdoor air pollution and human infertility: a systematic review. Fertil. Steril. 106, 897–904. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2016.07.1110 (2016).

Wang, L. et al. Effects of PM2.5 exposure on reproductive system and its mechanisms. Chemosphere 264, 128436. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2020.128436 (2021).

Quraishi, S. M. et al. Association of prenatal exposure to ambient air pollution with adverse birth outcomes and effect modification by socioeconomic factors. Environ. Res. 212, 113571. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2022.113571 (2022).

Sun, X. et al. Associations of ambient temperature exposure during pregnancy with the risk of miscarriage and the modification effects of greenness in Guangdong, China. Sci. Total Environ. 702, 134988. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.134988 (2020).

Feng, X. et al. Association of exposure to ambient air pollution with ovarian reserve among women in Shanxi Province of North China. Environ. Pollut. 278, 116868. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2021.116868 (2021).

Nieuwenhuijsen, M. J. et al. Air pollution and human fertility rates. Environ. Int. 70, 9–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2014.05.005 (2014).

Mahalingaiah, S. et al. Adult air pollution exposure and risk of infertility in the nurses’ health study II. Hum. Reprod. 31, 638–647. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/dev330 (2016).

Li, Q. et al. Association between exposure to airborne particulate matter less than 2.5 Μm and human fecundity in China. Environ. Int. 146, 106231. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2020.106231 (2021).

Nobles, C. J. et al. Time-varying cycle average and daily variation in ambient air pollution and fecundability. Hum. Reprod. 33, 166–176. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/dex341 (2018).

Slama, R. et al. Short-Term impact of atmospheric pollution on fecundability. Epidemiology 24 https://doi.org/10.1097/EDE.0b013e3182a702c5 (2013).

Wesselink, A. K. et al. Air pollution and fecundability: results from a Danish preconception cohort study. Paediatr. Perinat. Ep. 36, 57–67. https://doi.org/10.1111/ppe.12832 (2022).

Namvar, Z. et al. Association of ambient air pollution and age at menopause: a population-based cohort study in Tehran, Iran. Air Qual. Atmos. Health. 15, 2231–2238 (2022).

Hood, R. B. et al. Exposure to particulate matter air pollution and age of menarche in a nationwide cohort of U.S. Girls. Environ. Health Persp. 131, 107003. https://doi.org/10.1289/EHP12110 (2023).

Jensen, P. M., Sørensen, M. & Weiner, J. Human total fertility rate affected by ambient temperatures in both the present and previous generations. Int. J. Biometeorol. 65, 1837–1848. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00484-021-02140-x (2021).

Samuels, L. et al. Physiological mechanisms of the impact of heat during pregnancy and the clinical implications: review of the evidence from an expert group meeting. Int. J. Biometeorol. 66, 1505–1513. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00484-022-02301-6 (2022).

Kuehn, L. & McCormick, S. Heat exposure and maternal health in the face of climate change. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 14, 853. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14080853 (2017).

Geruso, M., LoPalo, M., Spears, D., Abbott, G. & Temperature In, Humidity, and human fertility: evidence from 58 developing countries. (2020).

Segal, T. R. & Giudice, L. C. Systematic review of climate change effects on reproductive health. Fertil. Steril. 118, 215–223. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2022.06.005 (2022).

LaPointe, S. et al. Ambient temperature in relation to ovarian reserve and early outcomes following ovarian stimulation and in vitro fertilization. Environ. Res. 271, 121117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2025.121117 (2025).

Lu, C. et al. Interaction effect of prenatal and postnatal exposure to ambient air pollution and temperature on childhood asthma. Environ. Int. 167, 107456. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2022.107456 (2022).

Sun, S. et al. Temperature as a modifier of the effects of fine particulate matter on acute mortality in Hong Kong. Environ. Pollut. 205, 357–364. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2015.06.007 (2015).

Qin, R. X. et al. The interactive effects between high temperature and air pollution on mortality: A time-series analysis in Hefei, China. Sci. Total Environ. 575, 1530–1537. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.10.033 (2017).

Du, Z. et al. Interactions between climate factors and air pollution on daily HFMD cases: A time series study in Guangdong, China. Sci. Total Environ. 656, 1358–1364. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.11.391 (2019).

Chen, F. et al. Does temperature modify the effect of PM10 on mortality? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Environ. Pollut. 224, 326–335. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2017.02.012 (2017).

Burkart, K. et al. Interactive short-term effects of equivalent temperature and air pollution on human mortality in Berlin and Lisbon. Environ. Pollut. 183, 54–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2013.06.002 (2013).

García, D., Brazal, S., Rodríguez, A., Prat, A. & Vassena, R. Knowledge of age-related fertility decline in women: A systematic review. Eur. J. Obstet. Gyn R B. 230, 109–118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejogrb.2018.09.030 (2018).

No., C. O. Female age-related fertility decline. Fertil. Steril. 101, 633–634. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013.12.032 (2014).

Chen, F. & Liu, C. Estimation of the Spatial rainfall distribution using inverse distance weighting (IDW) in the middle of Taiwan. Paddy Water Environ. 10, 209–222. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10333-012-0319-1 (2012).

Peng, S., Ding, Y., Liu, W. & Li, Z. 1 km monthly temperature and precipitation dataset for China from 1901 to 2017. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 11, 1931–1946, doi:https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-11-1931-2019. (2019).

Zhang, H. et al. Ambient air pollution exposure and gestational diabetes mellitus in Guangzhou, China: A prospective cohort study. Sci. Total Environ. 699, 134390. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.134390 (2020).

Didan, K. MOD13Q1 MODIS/Terra vegetation indices 16-day L3 global 250m SIN grid V006. Nasa Eosdis Land. Processes Daac. 10. https://doi.org/10.5067/MODIS/MOD13Q1 (2015).

Chen, Y., Xu, C., Ge, Y., Zhang, X. & Zhou, Y. A 100-m gridded population dataset of China’s seventh census using ensemble learning and geospatial big data. Earth System Science Data Discussions 2024, 1–19, (2024). https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-16-3705-2024

Zhao, N., Liu, Y., Cao, G., Samson, E. L. & Zhang, J. Forecasting China’s GDP at the pixel level using nighttime lights time series and population images. Gisci Remote Sens. 54, 407–425. https://doi.org/10.1080/15481603.2016.1276705 (2017).

Cusack, L., Larkin, A., Carozza, S. E. & Hystad, P. Associations between multiple green space measures and birth weight across two US cities. Health Place. 47, 36–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2017.07.002 (2017).

Knol, M. J. et al. Estimating measures of interaction on an additive scale for preventive exposures. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 26, 433–438. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-011-9554-9 (2011).

Zhang, Y. et al. Associations of ambient air pollution exposure and lifestyle factors with incident dementia in the elderly: A prospective study in the UK biobank. Environ. Int. 190, 108870. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2024.108870 (2024).

Conforti, A. et al. Air pollution and female fertility: a systematic review of literature. Reprod. Biol. Endocrin. 16, 117. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12958-018-0433-z (2018).

Li, H. et al. Particulate matter exposure and stress hormone levels: a randomized, double-blind, crossover trial of air purification. Circulation 136, 618–627. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.026796 (2017).

Carré, J., Gatimel, N., Moreau, J., Parinaud, J. & Léandri, R. Does air pollution play A role in infertility? A systematic review. Environ. Health-Glob. 16, 82. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12940-017-0291-8 (2017).

LaPointe, S. et al. Ambient traffic related air pollution in relation to ovarian reserve and oocyte quality in young, healthy oocyte donors. Environ. Int. 183, 108382. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2023.108382 (2024).

Lam, D. A. & Miron, J. A. The effects of temperature on human fertility. Demography 33, 291–305. https://doi.org/10.2307/2061762 (1996).

Online, W. W. Chengdu Annual Weather Averages. https://www.worldweatheronline.com/chengdu-weather-averages/sichuan/cn.aspx (accessed on 2024/10/6).

Franchini, M. & Mannucci, P. M. Air pollution and cardiovascular disease. Thromb. Res. 129, 230–234. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.thromres.2011.10.030 (2012).

Zupo, R. et al. Air pollutants and ovarian reserve: a systematic review of the evidence. Front. Public. Health. 12, 1425876 (2024).

Shi, W. et al. Association between ambient air pollution and pregnancy outcomes in patients undergoing in vitro fertilization in Shanghai, China: A retrospective cohort study. Environ. Int. 148, 106377. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2021.106377 (2021).

Wu, S. et al. Poor ovarian response is associated with air pollutants: A multicentre study in China. Ebiomedicine 2022, 81, 104084, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ebiom.2022.104084

Merklinger-Gruchala, A., Jasienska, G. & Kapiszewska, M. Effect of air pollution on menstrual cycle Length—A prognostic factor of women’s reproductive health. In Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health, ; 14. (2017).

Eddie-Amadi, B. F., Dike, C. S. & Ezejiofor, A. N. Public health concerns of environmental exposure connected with female infertility. Ips J. Public. Health 1. (2022).

Björvang, R. D. et al. Persistent organic pollutants, pre-pregnancy use of combined oral contraceptives, age, and time-to-pregnancy in the SELMA cohort. Environ. Health-Glob. 19, 67. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12940-020-00608-8 (2020).

Qiu, H. et al. The burden of COPD morbidity attributable to the interaction between ambient air pollution and temperature in Chengdu, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15030492 (2018).

Zhen, W. M., Shan, Z., Gong, W. S., Yan, T. & Zheng, S. K. The weather temperature and air pollution interaction and its effect on hospital admissions due to respiratory system diseases in Western China. Biomed. Environ. Sci. 26, 403–407. https://doi.org/10.3967/0895-3988.2013.05.011 (2013).

Cheng, Y. & Kan, H. Effect of the interaction between outdoor air pollution and extreme temperature on daily mortality in Shanghai, China. J. Epidemiol. 22, 28–36. https://doi.org/10.2188/jea.JE20110049 (2011).

Xie, F. et al. Association between physical activity and infertility: a comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Transl Med. 20, 237. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12967-022-03426-3 (2022).

Zajchowski, C. A., South, F., Rose, J. & Crofford, E. The role of temperature and air quality in outdoor recreation behavior: a social-ecological systems approach. Geogr. Rev. 112, 512–531 (2022).

Cichowicz, R., Wielgosiński, G. & Fetter, W. Dispersion of atmospheric air pollution in summer and winter season. Environ. Monit. Assess. 189, 605. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10661-017-6319-2 (2017).

Hoehne, C. G. et al. Heat exposure during outdoor activities in the US varies significantly by City, demography, and activity. Health Place. 54, 1–10 (2018).

Wang, L. et al. Increased risk of preterm birth due to heat exposure during pregnancy: exploring the mechanism of fetal physiology. Sci. Total Environ. 931, 172730. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2024.172730 (2024).

Acknowledgements

We are very grateful for the time and work of the handling editor(s) and four reviewers, whose processing and comments greatly helped to improve this manuscript.

Funding

This work was financially supported by the Chengdu Medical Scientific Research Project (2023004), the Yingcai Scheme, Chengdu Women’s and Children’s Central Hospital (YC2023010), the Yingcai Scheme, Chengdu Women’s and Children’s Central Hospital (YC2021003), and the JST SPRING (JPMJSP2136).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Kaili Zhang conceived and designed the study, and Kaili Zhang, Wei Chen, and Shasha Xing prepared software and performed the statistical analysis. Kaili Zhang prepared the manuscript. Prasanna Divigalpitiya assisted with editing of the paper and provided critical comments. Kaili Zhang and Shasha Xing revised it for important intellectual content. Erdan Luo supervised the research and verified its validity. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Chengdu Women’s and Children’s Central Hospital [Ethics Approval No. 2023(129)]. All data used in this study were fully anonymized, and participants provided informed consent.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, K., Chen, W., Divigalpitiya, P. et al. A retrospective study on the association of ambient air pollutants and temperature co-exposure with female infertility risk in Chengdu, China. Sci Rep 15, 18605 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03601-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03601-8