Abstract

Berberine hydrochloride (Ber) is the primary active compound in the traditional Chinese medicine ‘Huanglian’. Ursolic acid (UA) and oleanolic acid (OA) are the main triterpenoids extracted from ‘Tengligen’. Notably, both Ber and UA/OA exhibit antitumour activity. This study aimed to investigate the role of Ber and UA/OA in N-methyl-N′-nitro-N-nitrosoguanidine (MNNG)-induced malignant transformation of the human gastric mucosal epithelium and explore the underlying mechanism. Using network pharmacology and molecular docking, we analysed the molecular mechanisms of Ber and UA/OA in treating precancerous lesions of gastric cancer (PLGC). Our results revealed that Ber and UA/OA regulate the phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)/protein kinase B (AKT) pathway. To simulate PLGC, we established malignant cells (MCs) as an in vitro cellular model using MNNG. Our results showed that Ber and UA/OA significantly inhibited the epithelial-mesenchymal transition in MCs. Notably, UA/OA more effectively inhibited MC-colony formation and cell invasion and induced MC apoptosis than Ber. Mechanistically, UA/OA significantly suppressed the PI3K/AKT/nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB) p65/NACHT, LRR, and pyrin domain-containing protein 3 (NLRP3) pathway. However, the PI3K/AKT agonist 740YP reversed these effects and attenuated UA/OA-induced apoptosis. In conclusion, UA/OA significantly inhibited cell-clone formation and invasion, induced apoptosis, and inhibited the malignant transformation of MCs by regulating the PI3K/AKT/NF-κB p65/NLRP3 pathway.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Gastric cancer is the fifth most common cancer and the fifth leading cause of cancer-related deaths worldwide. In 2022, over 968,350 cases of gastric cancer were diagnosed, leading to 659, 853 deaths1. The Correa model suggests that gastric cancer develops in multiple stages, beginning with inflammation of the normal gastric mucosa caused by Helicobacter pylori (Hp) infection and other factors. This progression leads to atrophy, intestinal metaplasia, intraepithelial neoplasia, and ultimately gastric adenocarcinoma2. Precancerous lesions of gastric cancer (PLGC), such as gastric intraepithelial neoplasia, predispose tissues to transform into cancer. Some researchers classify atrophy, intestinal metaplasia, and dysplasia as PLGC3. Preventing or reversing PLGC development is a key strategy for reducing gastric cancer incidence4. For Hp-positive patients, eradication therapy remains the standard treatment. Additional therapies, including anti-acid drugs, mucosal protectants, and folic acid supplemented with vitamin C, are used for symptom management and prevention. Therefore, discovering effective and safe treatments to suppress or reverse PLGC remains a major focus of research.

Berberine hydrochloride (Ber), the primary active compound in the traditional Chinese medicine Huanglian, exhibits strong biological activities, including anti-inflammatory, immunomodulatory, antioxidant, and antitumour effects. It has also been shown to reverse mucosal atrophy and prevent intestinal metaplasia5. Ursolic acid (UA) and oleanolic acid (OA), the main triterpenoids extracted from Tengligen, are key contributors to its antitumour properties. Notably, Actinidia chinensis, a plant rich in UA and OA, has demonstrated potent antitumour effects. Studies have shown that UA and OA can induce apoptosis and inhibit viability, proliferation, migration, and metastasis of gastric cancer cells, suggesting their potential in gastric cancer prevention and treatment6,7,8,9.

N-methyl-N′-nitro-N-nitrosoguanidine (MNNG), a human carcinogen classified as a group 2 A compound by the International Agency for Research on Cancer7, is commonly used to induce gastric precancerous lesions in vitro. Treating human gastric mucosal epithelial cells (GES-1) with MNNG establishes a model of precancerous lesion cells, referred to as malignant cells (MCs)6, which simulate the progression of gastric precancerous changes4,10,11.

In this study, we utilised network pharmacology and molecular docking to analyse the signalling pathways through which Ber and UA/OA exert anti-PLGC effects. Additionally, MNNG was used to induce malignant transformation of GES-1 cells into MCs. We aimed to evaluate the effects of Ber and UA/OA on the epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT), invasiveness, apoptosis, and associated target pathways in MCs and to explore the underlying mechanisms at the cellular level.

Results

Potential targets of Ber, UA, and OA in the treatment of PLGC

Through network pharmacology analysis using the SwissTarget Prediction and BATMAN-TCM databases, 215 potential targets of Ber, OA, and UA were identified. Additionally, 4,155 disease-related targets associated with PLGC were obtained from the Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM) and GeneCards databases. A Venn diagram analysis revealed 153 overlapping targets, representing potential therapeutic targets of Ber, UA, and OA against PLGC (Fig. 1a). A monomer-target network was visualised using Cytoscape (Fig. 1b). These 153 targets were input into the STRING database to generate a protein–protein interaction (PPI) network (Fig. 1c), where higher-degree nodes indicated greater interaction relevance. Key targets included protein kinase B serine/threonine kinase 1 (AKT1), tumour protein p53, interleukin (IL)−6, tumour necrosis factor alpha, B-cell lymphoma-2 (Bcl-2), caspase 3, and signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3). Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis of 36 core proteins revealed 39 significantly enriched GO terms, particularly within biological regulation, cellular and immune system processes, and molecular function categories (Fig. 1d). Kyoto Encyclopaedia or Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway analysis indicated that the phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3 K)/AKT pathway is likely the primary signalling pathway modulated by the three monomers in the treatment of PLGC (Fig. 1e).

Network-pharmacological screening of Ber and UA/OA against PLGC. (a) Venn diagram for the targets of Ber and UA/OA and PLGC (A total of 153 associated genes were obtained). (b) Visual relationship-network mapping of disease targets and Ber and UA/OA. (c) PPI mapping of target-intersection relationships. (d) GO terms of Ber and UA/OA against PLGC. (e) KEGG pathways of Ber and UA/OA against PLGC. (f). Network diagram of Pathway-target-compound. Ber, berberine; UA, ursolic acid; OA, oleanolic acid; PLGC, precancerous lesion of gastric cancer; PPI, protein–protein interaction; GO, Gene Ontology; KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopaedia of Genes and Genomes.www.kegg.jp/kegg/kegg1.html.

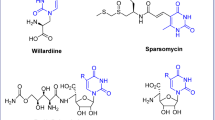

Molecular docking results demonstrated that Ber, UA, and OA exhibited binding energies below 5 kcal/mol with both AKT1 and phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase catalytic subunit alpha (PIK3 CA), indicating strong binding affinities (Fig. 2a–f). Notably, UA and OA showed lower binding energies to AKT1 and PIK3 CA than Ber, suggesting stronger interactions (Table 1). These findings preliminarily confirm that Ber, UA and OA have binding potential with key targets AKT1 and PIK3 CA within the PI3 K/AKT signalling pathway.

Docking modes of compound and core targets. (a) Ber-AKT1 (binding sites: GLN104 and GLN61). (b) Ber-PIK3 CA (binding sites: VAL125). (c) UA-AKT1 (binding sites: ARG25 and ASN53). (d) UA-PIK3 CA (binding sites: LYS924, GLN928, and GLU172). (e) OA-AKT1 (binding sites: ARG25 and ASN53). (f) OA-PIK3 CA (binding sites: LYS468, GLN682, and ARG683). AKT1, protein kinase 1; PIK3 CA, phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase catalytic subunit alpha.

Establishing the MC model

To establish the MC model, GES-1 cells were treated with MNNG. The 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)−2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assays showed that MNNG significantly reduced GES-1 cell viability at concentrations above 25 µM (p < 0.01) (Fig. 3a). Western blot analysis revealed that treatment with 5 and 10 µM MNNG increased N-cadherin and phosphorylated STAT3 (p-STAT3) expression while significantly decreasing E-cadherin levels compared with that in the untreated GES-1 group (p < 0.05), with the strongest effects observed at 10 µM (p < 0.01) (Fig. 3b–e). Based on these findings, 10 µM of MNNG was selected to induce the MC model in subsequent experiments.

Establishing MC models. (a) MTT assays were performed to examine the effects of different doses of MNNG on the activity of GES-1 cells. (b) Western blotting was performed to detect the expression levels of the EMT-related proteins N-cadherin, E-cadherin, and p-STAT3. (c–e). Statistical analysis of the optical densities of the western blot bands. **P < 0.01, *P < 0.05, compared with results from the GES-1 group. MC, malignant cells; MNNG, N-methyl-N’-nitro-N-nitrosoguanidine; EMT, epithelial–mesenchymal transition; p-STAT3, phosphorylated signal transducer and activator of transcription 3.

Effects of Ber and UA/OA on MCs

Western blot analysis showed that Ber and UA/OA significantly reduced the protein expression of N-cadherin, p-STAT3, vimentin, and alpha-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) in MCs (Fig. 4a-e, p < 0.05). However, Fig. S1a indicates that Ber and UA/OA did not induce significant inhibition of GES-1 cell proliferation across a concentration range of 1–50 µM. Among the treatments, UA/OA demonstrated the most pronounced inhibitory effect (p < 0.01), as demonstrated in Fig. S1b and S1c, confirming the consistent inhibitory effects of both Ber and UA/OA in 2D and 3D culture systems (p < 0.01). To further asses cellular behaviour, Transwell assays (Fig. 4f), colony-formation assays (Fig. 4g), and flow cytometry (Fig. 4h) were conducted to evaluate cell invasion, cell viability, and apoptosis, respectively. Both Ber and UA/OA significantly inhibited cell invasion and colony formation (p < 0.01) and promoted apoptosis (p < 0.01) at concentrations of 10 and 30 µM (Fig. 4i–k). Notably, 10 µM of UA/OA exhibited the strongest effect in reducing invasion and colony formation while inducing apoptosis.

Effects of Ber and UA/OA on MC. (a) The levels of EMT-related proteins and p-STAT3 in cells treated with 30 µM Ber and UA/OA, as detected by western blotting. (b–e) Statistical analysis of the optical density values of the western blot bands. (f) Transwell assays were performed to analyse cell-invasion abilities following the indicated treatments. (g) Plate colony-formation assays. (h) Flow cytometric analysis of apoptosis levels. (i) Statistical analysis of the quantitative Transwell assay results. (j) Statistical analysis of the quantitative results of the plate colony-formation assays. (k) Quantitative analysis of apoptosis detection by flow cytometry. **P < 0.01, *P < 0.05, compared with the control group; ##P < 0.01, #P < 0.05, compared with the MC group. Ber, berberine; UA, ursolic acid; OA, oleanolic acid; MC, malignant cells; EMT, epithelial–mesenchymal transition; p-STAT3, phosphorylated signal transducer and activator of transcription 3.

UA/OA inhibit MNNG-induced malignant transformation by regulating the PI3 K/AKT signalling pathway

Our network pharmacology analysis indicated that the PI3 K/AKT pathway is the primary pathway influenced by Ber and UA/OA. This finding was confirmed through western blotting (Fig. 5a and b), which showed that UA/OA inhibited the phosphorylation of PI3 K/AKT, nuclear factor-κappa B p65 (NF-κB p65), NACHT, LRR, and PYD domains-containing protein 3 (NLRP3) (p < 0.05). Reversibility studies using the PI3 K/AKT agonist 740YP (Fig. 5c and d) revealed that UA/OA downregulated the expression of PI3 K, AKT, NF-κB p65, and NLRP3 proteins in MNNG-treated GES-1 cells (p < 0.01). Moreover, UA/OA upregulated the pro-apoptotic Bax protein while downregulating the anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 protein. Notably, 740YP effectively activated the PI3 K/AKT pathway, reversing the regulatory effects of UA/OA on these proteins (p < 0.05). Furthermore, 740YP reversed the downregulation of N-cadherin, vimentin, and α-SMA proteins induced by UA/OA (Fig. 6). To further substantiate the binding of UA/OA to key components of the PI3 K/AKT pathway, the Cellular Thermal Shift Assay (CETSA) was performed. The results of this experiment, shown in Fig. S2, demonstrate that UA/OA bind directly to AKT, leading to an increase in the thermal stability of the protein. This finding provides direct evidence of the interaction between UA/OA and AKT, further supporting their role in regulating the PI3 K/AKT signalling pathway.

UA/OA regulated the PI3 K/AKT pathway to inhibit MNNG-induced malignant transformation. (a) Western blot analysis of PI3 K, AKT, NF-κB p65, and NLRP3 protein expression levels. (b) Statistical analysis of the optical density bands of the western blots (**P < 0.01, *P < 0.05, compared with the control group; ##P < 0.01, ##P < 0.05, compared with the MNNG group). (c) Western blotting was performed to detect the effects of PI3 K/AKT-pathway agonist, 740YP, on the expression of PI3 K, AKT, NF-κB p65, and NLRP3 and apoptosis-related proteins regulated by UA/OA. (d) Statistical analysis of the optical density bands detected of the western blots (**P < 0.01, *P < 0.05, compared with the control group; ##P < 0.01, ##P < 0.05, compared with the two groups). PI3 K, phosphoinositide 3-kinase; AKT, protein kinase B; NF-κB, nuclear factor-kappa B cells; NLRP3, NOD-, LRR- and pyrin domain-containing protein 3.

UA/OA inhibited MNNG-induced EMT. (a) Western blot analysis of N-cadherin, vimentin, and α-SMA protein expression levels. (b–d) Statistical analysis of the optical density bands of the western blots. **P < 0.01, *P < 0.05, compared with the control group; ##P < 0.01, ##P < 0.05, compared with two groups. UA, ursolic acid; OA, oleanolic acid; EMT, epithelial–mesenchymal transition; α-SMA, alpha-smooth muscle actin.

Discussion

In this study, GES-1 cells treated with MNNG showed significant upregulation of invasion and single-cell clone formation, along with the induction of the EMT process. These findings align with those reported by Cai and Ji4,11. Both Ber and UA/OA inhibited the expression of EMT-related proteins, such as vimentin and α-SMA, and reduced proliferation, invasion, single-cell viability, and EMT in malignant cells. Notably, UA/OA exhibited a stronger regulatory effect than Ber, particularly in inhibiting vimentin and αSMA expression. These results highlight the significant role of UA/OA in reducing the malignancy of GES-1 cells.

Based on network pharmacology analysis, Ber and UA/OA exert their effects primarily by regulating the PI3 K/AKT pathway. Notably, UA has been shown to inhibit breast cancer progression by downregulating PI3 K/AKT12, and Meng et al. demonstrated that UA induces apoptosis in prostate cancer cells via PI3 K/AKT and Bcl-2 inhibition13. Similarly, OA can inhibit the progression of hepatocellular cancer14 and gastric cancer9 by regulating the PI3 K/AKT pathway. These findings support the potential of UA and OA against PLGC via PI3 K/AKT regulation. To confirm this postulate, we used the PI3 K/AKT agonist 740YP, which reversed the inhibitory effects of UA/OA on PI3 K/AKT and reduced UA/OA-induced apoptosis.

Inflammation is a key factor in cancer development and progression15, with chronic inflammation strongly linked to tumourigenesis16. Many cancer-inducing signals from NF-κB can initiate carcinogenesis in normal cells, driving cancer development17. The NLRP3 inflammasome, a central component of innate immunity, mediates the secretion of proinflammatory cytokines, playing a crucial role in regulating inflammation by interacting with other cells18. In addition, NLRP3 promotes tumour growth in gastric cancer by stimulating the production of cyclin-D1 and IL-1β19. The NF-κB/NLRP3 pathway is essential in precancerous cells and plays a crucial role in tumourigenesis20. NF-κB, activated downstream of the PI3 K/AKT pathway, can induce EMT21. In this study, 740YP reversed the effects of UA/OA on reducing N-cadherin, vimentin, and α-SMA protein levels, confirming that activation of the PI3 K/AKT pathway is associated with EMT occurrence. Additionally, NF-κB induces NLRP3 expression during inflammation, and inhibiting NLRP3 can reduce the NF-κB-mediated inflammatory response22. Our western blot results revealed that UA/OA inhibited the expression of the proinflammatory proteins NF-κB p65 and NLRP3.However, cotreatment with 740YP significantly reversed the inhibitory effects of UA/OA on NF-κB p65 and NLRP3. These results suggest that blocking the NF-κB p65/NLRP3 pathway may be a potential mechanism by which UA/OA inhibit the malignant transformation of GES-1 cells. Nonetheless, further studies are needed to fully explore this possibility. Additionally, since NF-κB p65 and NLRP3 expression are closely linked to the PI3 K/AKT pathway, further investigation is required to clarify the relationship between the PI3 K/AKT pathway and inflammatory response.

Conclusion

In this study, we confirmed that UA/OA exhibited prominent activity against invasion and single-cell clone formation by MCs compared with Ber. Our findings also suggest that UA/OA induced apoptosis in MCs and inhibited the expression of NF-κBp65 and NLRP3 and malignant transformation of GES-1 cells through the PI3 K/AKT pathway. Together, the study results verified and clarified the mechanism of action of UA/OA against PLGC at the cellular level. However, further research, including animal experiments, is needed to clarify the pharmacological mechanism of UA/OA in reversing PLGC and to provide a theoretical basis for the development and clinical application of new drugs.

Methods

Network pharmacology analysis

We retrieved the SMILE numbers for Ber, UA, and OA from PubChem (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.NIH.gov/) and entered them into SwissTarget Prediction (http: swisstargetprediction.Ch/) to identify potential targets for these three monomers. After supplementing, merging, and removing duplicates using the BATMAN-TCM database (http://bionet.ncpsb.org.cn/batmantcm/), we obtained three potential target libraries for the monomers.

Using the OMIM database and GeneCards (https://www.genecards.org/), we searched “gastric mucosal dysplasia” and “gastric mucosal intraepithelial neoplasia” to identify disease-associated targets.

Drugs and disease targets were entered separately into the Venny 2.1 platform to generate a Venn diagram, revealing the intersection of both datasets. We then queried these monomer and disease targets in the STRING database (https://string-db.org/) using Cytoscape 3.7.2 software to identify potential PPIs and functional relationships. The protein type was set to ‘Homo sapiens’, with a minimum interaction threshold of 0.4. The target interaction data were imported into Cytoscape to generate a PPI network diagram.

Based on the median degree, further screening identified core targets, which were subsequently for GO and KEGG enrichment analyses23,24. Enrichment analysis was performed with significance thresholds set at p < 0.05 and q < 0.05.

Molecular docking simulation verification

Based on the PPI results from network pharmacology, pathway-related target proteins were selected for molecular docking validation with Ber, UA, and OA. First, we downloaded the two-dimensional structures of the compounds from PubChem and the three-dimensional structures of the target proteins from the PDB database. The protein structures were then processed using the PyMOL 2.4.0 software. Molecular docking was performed with AutoDockTools 1.5.6, and the results were visualised using PyMOL 2.4.0 for further analysis.

Cell culture

The GES-1 cell line was purchased from Zhejiang Ruyao Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Ningbo, China) and cultured in Roswell Park Memorial Institute-1640 (RPMI-1640) medium, supplemented with 10% foetal bovine serum (FBS, Gibco, Massachusetts, USA). The cells were incubated at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere.

Cell-viability assay

GES-1 cells were seeded in 96-well plates at a density of 1 × 104 cells/well. After 24 h of incubation, the cells were treated with varying concentrations of MNNG (0, 1, 5, 10, 25, 50, or 100 µM; purity ≥ 98.0%, MedChemExpress) for 48 h. Following treatment, a 5 mg/mL MTT solution was added to each well, and the cells were incubated for 4 h at 37 °C. Subsequently, 100 µL of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) was added to each well to dissolve the formazan crystals. After shaking at 200 rpm for 5 min, the absorbance was measured at 570 nm using a microplate reader (CMax Plus, Molecular Devices, California, USA). The cell viability inhibition rate was calculated using the 0 µM MNNG group as the control.

Western blotting

Cells (5 × 106) were collected and lysed using radio immunoprecipitation assay lysis buffer containing a phosphatase inhibitor cocktail. The protein lysates were denatured by adding 5× loading buffer and heating the samples at 100 °C for 5 min. Then, 50 µg of protein was separated via sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred onto polyvinylidene fluoride membranes. After blocking with 5% skimmed milk powder at 25 °C for 2 h, the membranes were incubated with primary antibodies (N-cadherin, E-cadherin, p-STAT3, STAT3, vimentin, α-SMA, NLRP3, p-NF-κB p65, NF-κB p65, p-AKT, AKT, p-PI3 K, PI3 K, Bax, and Bcl-2) diluted 1:500 for 2 h at 37 °C. Following this, the membranes were incubated with a secondary horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G antibody (1:2,000 dilution) for 2 h at room temperature. Luminescence detection was performed using an enhanced chemiluminescent substrate, and images were acquired using the ChemiDoc-It Imaging System (UVP, California, USA). β-actin (R1207-1, Huabio Biotechnology Co. Ltd., hangzhou, China) was used as an internal reference protein for normalisation. The optical density of each band was quantified using the ImageJ software (version 1.8.0).

Transwell experiment

The lower chambers of Transwell plates were prepared by adding 600 µL of medium containing 10% FBS to each well. Cell suspensions (5 × 104 cells/well, Corning, Inc., New York, USA) were inoculated into the upper chambers of the Transwell plates, which had an 8 μm pore size. The experimental groups included: GES-1 (control group), MC (model group), MC + UA/OA (5 µM group), MC + UA/OA (10 µM group), MC + UA/OA (30 µM group), MC + Ber (5 µM group), MC + Ber (10 µM group), and MC + Ber (30 µM group). Ber (purity ≥ 98.0%, HY-N0716), UA (purity 99.66%, HY-N0140), and OA (purity ≥ 98.0%, HY-N0156) were all purchased from MCE, with a molar ratio of 8:125. After incubation at 37 °C with 5% CO2 for 48 h, the cells remaining on the upper surface of the membrane were gently removed using a cotton swab. The cells on the bottom surface of the membrane were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and stained with 1% crystal violet. The invasive capacity of the cells was assessed by counting the number of cells in three different fields of view under a microscope, with the cell count performed using the ImageJ software.

Cell-based colony-formation assay

Cell suspensions were grouped as described above and seeded into 6-well plates at a density of 1,000 cells/well. The cells were treated as per the experimental groupings outlined in transwell experimentand incubated in a 37 °C incubator with 5% CO2 for 14 days. The medium was replaced every 3 days without altering the treatment conditions. After 14 days, the colonies formed were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min at room temperature and stained with a 1% crystal violet solution for 15 min. The results were photographed, and the number of colonies was quantified using the Image-Pro Plus software (version 6.0). Three replicate wells were tested for each group.

Apoptosis assay

The cells were grouped as described in transwell experiment and treated with different concentrations of compounds for 48 h. Approximately 1 × 106 cells were harvested by trypsin digestion, washed twice with pre-chilled phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and resuspended in 100 µL of binding buffer provided in the Solarbio Apoptosis Assay Kit (Beijing, China). The cells were then incubated for 15 min with 5 µL of Annexin V-FITC, followed by the addition of 5 µL of propidium iodide for 8 min. After adding additional buffer, apoptosis was analysed using an Attune NxT flow cytometer (Applied Biosystems,, Massachusetts, USA).

Regulation of the PI3 K/AKT pathway in MCs by UA/OA

Group 1 consisted of the control, MC, and UA/OA groups, of which the latter two were treated with 10 µM MNNG and 10 µM UA/OA (8:1 molar ratio), respectively. Group 2 included the control, MC, UA/OA, and UA/OA + 740YP groups, of which the latter two were treated with 10 µM MNNG plus 10 µM UA/OA (8:1 molar ratio) and 20 µM 740YP (a PI3 K/AKT pathway agonist).

After 48 h of treatment with the dosing compounds, cells (5 × 106) were collected for western blotting assays. The following antibodies were used in the assays: AKT, NF-κB, p-NF-κB (phospho-S529), NLRP3, Bcl-2, Bax (Huabio Biotechnology Co. Ltd., hangzhou, China), PI3 K, p-PI3 K (phospho-Ser244/249), and p-AKT (phospho-Ser473) (Signalway Antibody, Minnesota, USA).

Cell viability assays in 2D and 3D cell culture

Cell viability assays were conducted to assess the growth inhibitory effects of UA, OA, and Ber onMCs in both 2D and 3D culture systems. For the 2D culture, MCs were seeded at a density of 1 × 10⁴ cells per well in 96-well plates. The cells were treated with different concentrations (1, 5, 10, 25, and 50 µM) of UA/OA, and Ber for 48 h. Cell viability was assessed using the MTT assay, where 20 µL of MTT reagent (5 mg/mL) was added to each well, followed by incubation for 4 h at 37 °C. The formazan product was dissolved in 150 µL of DMSO, and the absorbance was measured at 570 nm using a microplate reader. For the 3D culture system, MCs were cultured in poly(2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate)-coated plates to prevent cell adhesion and allow the formation of multicellular spheroids. The cells were treated with different concentrations of UA/OA or Ber and cultured for 5 days. The inhibition of spheroid formation and growth was evaluated using the CCK-8 assay, where the cell viability in the spheroids was measured by adding CCK-8 reagent and quantifying the absorbance at 450 nm.

Cellular thermal shift assay

The MCs were seeded in 6-well plates at a density of 1 × 106 cells per well and incubated in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium supplemented with 10% FBS at 37 °C for 48 h in 5% CO2. After treatment with DMSO (control group) or 10 µM UA/OA for 48 h, the cells were washed twice with cold PBS and scraped off. The cell pellets were resuspended in PBS and subjected to protein extraction using a lysis buffer containing a protease inhibitor cocktail. The cell lysates were then aliquoted into polymerase chain reaction tubes and subjected to a temperature gradient ranging from 37 °C to 72 °C for 3 min at each temperature increment. After heating, the samples were immediately cooled in liquid nitrogen, and centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 15 min to collect the supernatant containing soluble proteins. Protein expression levels of AKT were assessed using western blotting. The protein bands were quantified using ImageJ software; CETSA curve analysis was performed using the Biphasic Sigmoidal equation in GraphPad Prism 8.0. The experiment was conducted in triplicate.

Statistical analysis

All data generated in this study are presented as the mean ± standard deviation from three independent replicates. Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism Software (version 8, GraphPad Software, Inc.). The Shapiro–Wilk test was used to assess the normality of the data. For data with a normal distribution, one-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey’s post-hoc test was applied. For data that did not conform to a normal distribution, the Kruskal–Wallis test was used. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed in the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Bray, F. et al. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 74, 229–263 (2024).

Li, S., Guo, Y., Liu, X. & Chen, Y. Helicobacter pylori plus N-methyl-N’-nitro-N-nitrosoguanidine: DNA damage and repair: malignant transformation of human esophageal epithelial cells. Mutat. Res. Genet. Toxicol. Environ. Mutagen. 888, 503636 (2023).

Xu, W., Li, B., Xu, M., Yang, T. & Hao, X. Traditional Chinese medicine for precancerous lesions of gastric cancer: A review. Biomed. Pharmacother. 146, 112542 (2022).

Ji, R. et al. miR-374 mediates the malignant transformation of gastric cancer-associated mesenchymal stem cells in an experimental rat model. Oncol. Rep. 38, 1473–1481 (2017).

Liu, Q. et al. Multi-step actions on the Correa’s cascade underlie its therapeutic effects. Pharmacol. Res. 184, 106440 (2022).

Xiang, F. et al. Ursolic acid inhibits the proliferation of gastric cancer cells by targeting Mir-133a. Oncol. Res. 22, 267–273 (2015).

Li, Y., Xu, Q., Yang, W., Wu, T. & Lu, X. Oleanolic acid reduces aerobic glycolysis-associated proliferation by inhibiting yes-associated protein in gastric cancer cells. Gene 712, 143956 (2019).

Piet, M. & Paduch, R. Ursolic and oleanolic acids as potential anticancer agents acting in the Gastrointestinal tract. Mini Rev. Org. Chem. 16, 78–91 (2019).

Lee, J. H. et al. Oleanolic acid induces apoptosis and autophagy via the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway in AGS human gastric cancer cells. J. Funct. Foods. 87, 104854 (2021).

Badr El-Din, N. K., Fattah, A., Pan, S. M., Tolentino, D., Ghoneum, M. & L. & Chemopreventive activity of MGN-3/Biobran against chemical induction of glandular stomach carcinogenesis in rats and its apoptotic effect in gastric cancer cells. Integr. Cancer Ther. 15, NP26–NP34 (2016).

Cai, J. et al. N-methyl-N-nitro-N’-nitrosoguanidine induces the expression of CCR2 in human gastric epithelial cells promoting CCL2-mediated migration. Mol. Med. Rep. 13, 1083–1090 (2016).

Luo, J., Hu, Y. L. & Wang, H. Ursolic acid inhibits breast cancer growth by inhibiting proliferation, inducing autophagy and apoptosis, and suppressing inflammatory responses via the PI3K/AKT and NF-κB signaling pathways in vitro. Exp. Ther. Med. 14, 3623–3631 (2017).

Meng, Y. et al. Ursolic acid induces apoptosis of prostate cancer cells via the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway. Am. J. Chin. Med. 43, 1471–1486 (2015).

Shi, Y. et al. Oleanolic acid induced autophagic cell death in hepatocellular carcinoma cells via PI3K/Akt/mTOR and ROS-dependent pathway. Korean J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 20, 237–243 (2016).

Karki, R. et al. NLRC3 is an inhibitory sensor of PI3K–mTOR pathways in cancer. Nature 540, 583–587 (2017).

Karki, R. & Kanneganti, T. D. Diverging inflammasome signals in tumorigenesis and potential targeting. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 19, 197–214 (2019).

Karin, M. NF-kappaB and cancer: mechanisms and targets. Mol. Carcinog. 45, 355–361 (2006).

Dupaul-Chicoine, J. et al. The Nlrp3 inflammasome suppresses colorectal cancer metastatic growth in the liver by promoting natural killer cell tumoricidal activity. Immunity 43, 751–763 (2015).

Hai Ping, P., Feng Bo, T., Li, L., Nan Hui, Y. & Hong, Z. IL-1β/NF-kb signaling promotes colorectal cancer cell growth through miR-181a/PTEN axis. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 604, 20–26 (2016).

Aranda, F. et al. Immune effectors responsible for the elimination of hyperploid cancer cells. Oncoimmunology 7, e1463947 (2018).

Ahmad, A. et al. Targeted regulation of PI3K/Akt/mTOR/NF-κB signaling by Indole compounds and their derivatives: mechanistic details and biological implications for cancer therapy. Anticancer Agents Med. Chem. 13, 1002–1013 (2013).

Boaru, S. G., Borkham-Kamphorst, E., Van de Leur, E., Lehnen, E. & Weiskirchen, R. NLRP3 inflammasome expression is driven by NF-κB in cultured hepatocytes. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 458, 700–706 (2015).

Kanehisa, M. et al. KEGG as a reference resource for gene and protein annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, D457–D462 (2016).

Kanehisa, M. & Goto, S. KEGG. Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 28, 27–30 (2000).

Xu, C., Zhang, G., Lou, Z., Xu, H. & Shen, L. Effects of effective component of Kiwi root on Inhibition of proliferation and migration of gastric cancer cell BGC-823. J. Nanjing Univ. Tradit Chin. Med. 34, 602–606 (2018).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Xiao-Lei Ye for his technical guidance in the cellular experiments.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 82174352, Zhen Liu, China), Major Research and Development Project of Science and Technology Innovation Engineering of Chinese Academy of Traditional Chinese Medicine (CI2021 A00806, Yuning Bai, China).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: Y.B.,M.L. Writing-original draf: M.L.,Y.B.,J.D., Writing-review and editing: Y.B.,W.L.,L.W.,Y.L.,Q.W.,Q.Z.,X.Z.,N.Y.,R.Z.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, M., Dong, J., Wang, L. et al. Ursolic and oleanolic acids suppress MNNG induced malignant transformation of human gastric mucosal epithelium by regulating the PI3 K/AKT pathway. Sci Rep 15, 21623 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03606-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03606-3