Abstract

Brain tumors are a critical medical challenge, requiring accurate and timely diagnosis to improve patient outcomes. Misclassification can significantly reduce life expectancy, emphasizing the need for precise diagnostic methods. Manual analysis of extensive magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) datasets is both labor-intensive and time-consuming, underscoring the importance of an efficient deep learning (DL) model to enhance diagnostic accuracy. This study presents an innovative deep ensemble approach based on transfer learning (TL) for effective brain tumor classification. The proposed methodology incorporates comprehensive preprocessing, data balancing through synthetic data generation (SDG), reconstruction and fine-tuning of TL architectures, and ensemble modeling using Genetic Algorithm-based Weight Optimization (GAWO) and Grid Search-based Weight Optimization (GSWO) used to optimize model weights for enhanced performance. Experiments were performed on the Figshare Contrast-Enhanced MRI (CE-MRI) brain tumor dataset, consisting of 3064 images. The proposed approach demonstrated exceptional performance, achieving classification accuracies of 99.57% with Xception, 99.48% with ResNet50V2, 99.33% with ResNet152V2, 99.39% with InceptionResNetV2, 99.78% with GAWO, and 99.84% with GSWO. The GSWO achieved the highest average accuracy of 99.84% across five-fold cross-validation among other DL models. The comparative analysis highlights the superiority of the proposed model over State of Arts (SOA) works, showcasing its potential to assist neurologists and clinicians in making precise and timely diagnostic decisions. The study concludes that the optimized deep ensemble model is a robust and reliable tool for brain tumor classification.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The brain, a vital organ responsible for all voluntary and involuntary bodily functions, is exceptionally intricate and fragile. Brain tumors, among the most lethal brain disorders, arise from abnormal tissue growth within the skull1. They are classified into primary and secondary tumors, with primary tumors accounting for 70% of cases and remaining confined to the brain2. Gliomas, meningiomas, and pituitary tumors are common types, each posing distinct health risks. Pituitary tumors, though typically benign, can cause hormonal imbalances and vision impairment3. Detecting and treating brain tumors presents significant challenges due to their complexity and diagnostic intricacies. The World Health Organization forecasts a 5% annual increase in global brain tumor cases4. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography (CT) scans are preferred clinical tools for identifying brain abnormalities, with MRI being widely utilized across various neurological conditions5. The specific background in Machine Learning (ML) and Deep Learning (DL) techniques highlights their significant potential in neuroscience, particularly for the early detection of brain tumors6. Despite advancements, current diagnostic methods for brain MRI scans need improvements in accuracy and speed, especially as the volume of medical data grows. DL has become a crucial tool, offering the ability to autonomously identify complex patterns in large biomedical datasets, thus enhancing disease diagnosis and classification, including brain tumors7. DL surpasses traditional methods in classification, detection, and other predictive tasks by efficiently extracting and optimizing features directly from raw data. This capability is particularly valuable for biomedical applications and image-based tasks8. Transfer learning (TL) further enhances DL by utilizing pre-trained models to reduce computational demands and speed up model training9. TL adapts pre-trained model weights, especially in convolutional layers, to new tasks, making it efficient for developing specialized models across various applications10.

In the extensive body of related works, each effort stands as a unique approach to the category of brainiac tumors, contributing valuable insights to the field. Moreover, DL techniques have found notable applications in representing and interpreting various medical images11. These methods have empowered machines to effectively assess a wide array of medical data, ranging from multidisciplinary pathology scans to elevated-dimensional image datasets and video recordings, as exemplified in the work of12. Furthermore, the versatility of DL extends its impact beyond medical imaging to encompass disease prediction. Researchers have demonstrated the adaptability of DL techniques in healthcare, offering fresh insights into the intersection of DL and disease prediction. These collective contributions underscore the wide-ranging applications of DL in medical research, providing a strong foundation for our innovative approach to categorizing brain tumors13,14.

The manual assessment and analysis of an extensive collection of brain MRI data is resource-intensive, time-consuming, and prone to errors, given the expertise required for processing and classifying MRI images. The precise diagnosis and categorization of brain tumors are crucial as they inform prognostic predictions and guide medical experts in selecting suitable treatment options. However, the manual evaluation of diverse brain MRI data is prone to inaccuracies and demands considerable expertise. This precision in diagnosis and categorization is imperative, as it underpins predictive insights and empowers medical specialists to make well-informed decisions regarding patient care.

Our research focuses on developing a robust DL model for efficient brain tumor prediction using MRI data. We have established a systematic framework that involves preprocessing, data balancing, fine-tuning and creating ensemble DL models where they are optimized using Genetic Algorithm-based Weight Optimization (GAWO) and Grid Search-based Weight Optimization (GSWO). We have selected pivotal TL architectures such as ResNet50V2, ResNet152V2, Xception, and InceptionResNetV2 for their computational efficiency and proven efficacy in handling the complexities of MRI data, which is essential for processing large brain tumor datasets.

The main contributions of this research are as follows:

-

1.

Optimized deep learning model: This study proposes an advanced DL model tailored for brain tumor classification. The model integrates comprehensive preprocessing, data balancing, TL architecture modifications, fine-tuning techniques, and two optimization-based ensemble methods, significantly enhancing classification accuracy and efficiency.

-

2.

Synthetic data generation for balancing: To address class imbalance, synthetic data generation (SDG) is utilized, ensuring balanced representation across the dataset and improving the robustness of the model.

-

3.

Enhanced transfer learning architectures with fine-tuning: To mitigate overfitting and streamline the classification process, the TL architectures are enhanced with advanced image augmentation technique and performing fine-tuning procedures, ensuring reliable and efficient workflow.

-

4.

Optimization-based ensemble techniques: This study introduces two optimization-based ensemble techniques such as: GSWO and GAWO. GSWO stands out for its rigorous, exhaustive search process, systematically identifying the most effective weight combinations for the ensemble model, which improves accuracy and robustness compared to traditional methods. Our results demonstrate that GSWO significantly outperforms GAWO, setting a new standard for weight optimization in DL applications.

The following sections of the paper are organized as follows: “Literature review” section provides an overview of previous studies on the prediction of brain tumors using deep learning. Section “Methodology” explains our research methodology and dataset in detail. In “Results analysis” section, we present the experimental information and performance evaluation. Section “Discussion” presents the discussion of our proposed model with existing works. Finally, the paper concludes with Section 6 in “Conclusion”.

Literature review

Recent advancements in DL for medical imaging have led to the development of various models that show significant potential in applications in brain tumor classification tasks. The following studies have included brain tumor classification works.

Transfer learning (TL) approaches

Nassar et al.15 presented an automated approach to efficiently classify brain tumors, aiming to assist radiologists by reducing the manual effort required to analyze large volumes of images for accurate diagnoses. The study utilized a dataset comprising 3064 T1-weighted contrast-enhanced brain MR images (T1W-CE MRI) from 233 patients. The proposed system combined the outputs of five distinct models to leverage their collective strengths, resulting in enhanced classification performance. This ensemble-based approach achieved an impressive overall accuracy of 99.31%. Agarwal et al.16 developed an Auto Contrast Enhancer, Tumor Detector, and Classifier for improving the contrast of low-quality MRI images, aiding in the early diagnosis and classification of brain tumors. The system employed a two-phase approach: first, ODTWCHE enhanced the image contrast, and then a deep transfer learning model, Inception V3, further refined the diagnosis. The proposed system outperformed models like AlexNet, VGG-16, and ResNet-50, achieving 98.89% accuracy on a public dataset with varying contrast and brightness levels, demonstrating its robustness in tumor detection and classification. Talukder et al.17 introduced a novel DL approach for categorizing brain tumors. The method involved various steps such as data preprocessing, TL architecture creation, and fine-tuning. They tested different TL models like Xception, ResNet50V2, InceptionResNetV2, and DenseNet201 on the Figshare dataset with 3064 MRI brain tumor images. The results demonstrated high accuracy, with ResNet50V2 achieving the best performance at 99.68%. This outperformed other models and could help doctors diagnose brain tumor patients quickly and accurately. Dahan et al.18 proposed a model with three steps: feature extraction, fusion, and classification. It uses ResNet50 CNN architecture to extract robust features from color-transformed MRI images, focusing on features from the first convolutional layer. A novel feature fusion technique based on the Marine Predator Algorithm (MPA) was introduced to enhance robustness. The model achieved 98.72% accuracy on a complex dataset, surpassing existing methods and effectively detecting brain tumors in camouflage images. Islam et al.19 presented a novel DL approach using the EfficientNet family for enhanced brain tumor classification and detection. Utilizing a dataset of 3064 T1-weighted CE MRI images, the methodology incorporates advanced preprocessing and augmentation techniques to optimize performance. Experiments showed that EfficientNetB0 achieved accuracies ranging from 98.76 to 99.14%. The EfficientNetB3 model, achieving 99.69% accuracy, outperformed many existing state-of-the-art techniques, demonstrating the effectiveness of the approach. Tummala et al.20 employed ImageNet-based Vision Transformer (ViT) models, pre-trained and fine-tuned for brain tumor classification. The ensemble ViT model’s interpretation was assessed using the Figshare brain tumor dataset, specifically for a three-class classification task through cross-validation (CV) and testing. The amalgamation of all ViT variants, such as L/16, B/16, L/32, and B/32, achieved an impressive total testing accuracy of 98.7%. This suggests that a group of ViT models holds the potential to aid in the marker of brain cancers based on MRI images, offering support to radiologists. Abd-Ellah et al.21 developed BTC-fCNN, a DL-based system for efficiently classifying three types of brain tumors-meningioma, glioma, and pituitary tumors-using MRI images from the Figshare dataset. The model, with 13 layers incorporating convolution and 1\(\times\)1 convolution layers, average pooling, fully connected layers, and a softmax layer, underwent five iterations, incorporating TL and five-fold cross-validation. The presented model attained remarkable results, boasting an average accuracy of 98.63% with five iterations and TL, and 98.86% with retrained five-fold cross-validation. BTC-fCNN outperformed existing strategies and other well-known CNNs, significantly advancing the categorization of brain tumors. Maruf et al.22 conducted a thorough assessment of 26 previously developed CNN models designed for general image classification in the context of brain tumors. The evaluation involved retraining these models using 3064 T1-weighted contrast-enhanced MR images. Pre-trained weights from the ImageNet dataset were employed, and the classification accuracies of the CNN models were compared. This comprehensive study examines various state-of-the-art CNN models using a multiclass brain MRI dataset. EfficientNetB3 emerged as the top performer, achieving a categorization accuracy of 98.98% among the 26 models tested. Other models, including DenseNet121, EfficientNetB2, EfficientNetB5, and EfficientNetB4, also demonstrated strong accuracy, with all models surpassing 97% accuracy in identifying the tumor type. This research delivers helpful insight into the efficacy of diverse CNN models for categorizing brain tumors.

Traditional deep learning (DL) approaches

Asif et al.23 designed a brain tumor diagnosis system using DL architectures, including DenseNet121, ResNet152V2, Xception, DenseNet201, and InceptionResNetV2. Modifications to the final layers, incorporating a deep dense block and softmax layer, aimed to enhance classification accuracy. Two experiments were conducted: one involving three-class classification (glioma, meningioma, and pituitary tumors) and another with four classes (including healthy patients). The outcomes emphasize the authority of the presented model based on the Xception architecture, achieving a remarkable 99.67% accuracy in the three-class dataset and 95.87% in the four-class dataset, outperforming state-of-the-art methods. This model holds promise as an automated diagnostic tool for radiologists, enabling accurate decision-making. Nassar et al.24 prepared an efficient automated approach to assist radiologists in classifying brain tumors, intending to save time compared to manual image analysis. The approach utilized 3064 brain MRI images from 233 patients. Drawing on the results of five different models, such as GoogleNet, ShuffleNet, SqueezeNet, AlexNet, and NASNet-Mobile, the system harnessed the integrated potential of numerous models and performed a majority voting technique to acquire favorable outcomes. The offered method demonstrated substantial progress in results, achieving an impressive prevalent accuracy of 99.31%. Saeedi et al.25 developed a 2D CNN and a convolutional autoencoder for brain tumor classification. The 2D CNN had eight convolutional and four pooling layers, utilizing 2\(\times\)2 kernel functions and batch normalization. The autoencoder network combined a convolutional autoencoder and a classification network. The 2D CNN achieved a training accuracy of 96.47%, with an average recall of 95%, while the autoencoder network achieved 95.63% accuracy and 94% recall. The study concluded that the 2D CNN effectively classified brain tumors. To optimize hyperparameters for CNN, Ait Younes et al.26 presented an advanced strategy relying on Bayesian optimization. Tested in the categorization of brain MRI scans into three cancer classes, the CNN, optimized using five pre-trained instances through TL, achieved a remarkable accuracy rate of 98.70% after employing Bayesian optimization. The proposed model surpassed existing works, showcasing the effectiveness of automated hyperparameter optimization. Ayadi et al.27 showcased a CNN-based model with multiple layers for MRI-based categorization of brain tumors. Requiring minimal preprocessing, the intelligent model was evaluated on three distinct brain tumor datasets. Achieving accuracy rates of 94.74% for Figshare, 93.71% for Radiopaedia, and 97.22% for Rembrandt datasets, the proposed scheme demonstrated superior classification and recognition accuracies compared to previous relevant studies on the same data. The summary of the literature review is represented in Table 1.

Methodology

In this study, we propose an optimized DL approach for accurate brain tumor classification on brain MRI images. Our comprehensive framework integrates several key components, including image preprocessing, data balancing, TL architecture modifications, model fine-tuning, and an ensemble learning process enhanced with weight optimization techniques. Key innovations include the use of SDG to balance the dataset, Image augmentation to ensure better generalization and mitigate overfitting, an enhanced fine-tuning process for improved classification accuracy, and the adoption of two weighted ensemble approaches such as GSWO and GAWO to improve model robustness.

The methodology begins with the collection and preprocessing of brain tumor image data, followed by data balancing and the reconfiguration of TL architectures such as ResNet50V2, ResNet152V2, Xception, and InceptionResNetV2. These architectures are expended through fine-tuning by incorporating additional layers, including batch normalization, global average pooling, dense+ReLU, flatten, dropout, and dense+Softmax layers, designed specifically for categorizing brain tumors within the dataset. Finally, two optimization models (GSWO and GAWO) are applied to analyze their performance besides the TL models on brain tumor classification. Figure 1 illustrates the structural design of our proposed classification approach. The following procedural steps outline the operations of our methodology:

Data collection

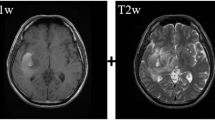

The brain tumor dataset, obtained from28, consists of 3064 T1-weighted contrast-enhanced images from 233 patients diagnosed with three different types of brain tumors: meningioma (708 slices), glioma (1426 slices), and pituitary tumors (930 slices). This comprehensive dataset is conveniently provided in MATLAB file format (.mat files). Each file is organized as a MATLAB structure, containing essential information for each image, including labels: 1 for meningioma, 2 for glioma, and 3 for pituitary tumors. Additionally, the dataset includes the image data, patient ID (PID), and tumor border information. The tumor boundary is carefully traced by hand and represented as a vector of coordinates along the edges of the tumor, allowing for the easy creation of a binary image to serve as a tumor mask. This mask is presented as a binary image, where a series of ones indicates the tumor region.

Image preprocessing

We meticulously prepared the dataset for further analysis in the initial stages of image preprocessing. Since the data was initially stored in Matlab (.mat) file format, we extracted image and label information to facilitate subsequent processing. The image preprocessing journey commenced with resizing all images to a uniform 256 x 256 dimension, enhancing visibility by applying a sharp filter and complementing the images. Further refinement was achieved through histogram equalization, contributing to a more balanced image representation. To ensure compatibility with the DL model, we scaled the images by dividing them by 255. For effective model training and evaluation, we performed k-fold cross-validation where k is five, so the dataset is partitioned into training and testing sets, allocating 80%, and 20%, respectively. Additionally, we applied 1000 shuffling iterations to reduce loss, lower variance, and enhance the model’s generalization. The resultant processed images exhibit heightened sharpness, brightness, and discernible details compared to their original counterparts, making them well-suited for input into the model. This meticulous preprocessing contributes to achieving an outstanding performance compared to contemporary methodologies. Fig. 2 presents images of brain glioma, meningioma, and pituitary tumors before and after preprocessing. The preprocessing enhances image clarity, aiding in improved tumor classification.

Part (a) shows raw MRI images of brain tumors before preprocessing, while part (b) presents theenhanced images after preprocessing techniques. These improvements enhance clarity, making tumor features more distinguishable for accurate classification. Images of brain glioma, meningioma, and pituitary tumors prior to and following image preprocessing.

Moreover, we have enhanced the preprocessing by experimenting with various image augmentation techniques to enrich the robustness and performance of the model. The applied augmentation methods include horizontal flipping, random image rotations (up to 35°), zoom adjustments (up to 25%), contrast variation, and image translations, which significantly increase the dataset’s variability. These augmentations are designed to simulate real-world conditions and improve the model’s ability to generalize across diverse scenarios. Additionally, we rescaled the input images to standardized pixel values (0–1) to ensure optimal conditions for training. These preprocessing enhancements contribute to a more comprehensive training set and improve the overall predictive performance of our deep learning model.

Data balancing using SDG

In medical image classification, particularly in brain tumor detection, the dataset is often imbalanced, where certain classes (e.g., different types of tumors) have fewer samples than others. This imbalance can result in biased models that perform well on the overrepresented classes but poorly on the underrepresented ones. To address this issue, Synthetic Data Generation (SDG) is employed using Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) to balance the dataset by generating new synthetic samples for the underrepresented classes. Specifically, GANs were utilized to generate synthetic samples for the underrepresented classes in the dataset. This approach allows us to create realistic and diverse samples that help balance the dataset, addressing class imbalance and enhancing model performance. By using GANs, we ensure that the generated data captures the underlying patterns of the minority classes, improving the model’s ability to generalize across all tumor types.

Data balancing is crucial in brain tumor classification for several reasons. First, it helps avoid model bias. When the dataset is imbalanced, the model may focus too much on the majority class, leading to poor performance on the minority classes. This is particularly problematic in medical imaging, where underrepresented tumor types might be misclassified, impacting clinical decision-making. Second, by generating synthetic data, we ensure that all classes are sufficiently represented, which allows the model to generalize better across different tumor types. Finally, data balancing reduces the risk of overfitting. An imbalanced dataset may lead to overfitting to the majority class, causing the model to perform poorly on new, unseen data. Balancing the dataset allows the model to learn features from all classes, which leads to improved generalization.

The imbalance ratio of a dataset can be defined as:

where \(D_1, D_2, \dots , D_K\) represent the datasets for each class and \(D_k\) is the number of samples in class \(C_k\). A large imbalance ratio indicates that the dataset is skewed, which can adversely affect the model’s performance. The goal of SDG is to generate synthetic data for the underrepresented classes to balance the dataset. This ensures that all classes have an equal number of samples, \(N_{\text {max}}\), where \(N_{\text {max}}\) is the maximum number of samples in any class. Let \(D_{\text {aug}}\) represent the augmented dataset, which is obtained by applying data augmentation techniques to the underrepresented classes until they reach \(N_{\text {max}}\):

where \(\text {Augment}(D_k)\) refers to the augmentation operation applied to the samples of class \(C_k\).

The data balancing process using SDG follows these steps:

-

1.

Step 1 Split the dataset \(D = \{(x_i, y_i)\}_{i=1}^{N}\) into K classes: \(C_1, C_2, \dots , C_K\).

-

2.

Step 2 Identify the class with the maximum number of samples, \(N_{\text {max}} = \max (D_1, D_2, \dots , D_K)\).

-

3.

Step 3 For each underrepresented class \(C_k\), apply augmentation operations to generate synthetic images until \(D_k = N_{\text {max}}\).

-

4.

Step 4 Merge the original and augmented datasets for each class to create a balanced dataset \(D_{\text {aug}}\).

-

5.

Step 5 Output the balanced dataset \(D_{\text {aug}}\) with equal samples per class.

The algorithmic representation is as follows:

This approach results in a balanced dataset, where all classes have an equal number of samples, thereby allowing the model to generalize across all classes during training.

The use of SDG for data balancing in brain tumor classification addresses the problem of class imbalance and significantly enhances model performance, particularly for underrepresented tumor types. By generating synthetic samples for minority classes, we ensure that the model has a diverse set of examples to learn from, leading to more accurate and reliable predictions. Figure 3 visually illustrates the distribution of the Brain CE-MRI dataset without and with SDG, providing insights into the composition of the three tumor types across the patient cohort.

Reconstruction with fine-tuning of transfer learning architecture

In our experimental endeavor, we undertake the crucial tasks of reconstructing TL models and fine-tuning them to enhance the model’s aptitude for accurately categorizing brain tumors. Within the reconstruction TL architecture framework, we address the inherent challenge posed by pre-trained TL algorithms, originally trained on ImageNet data. To adapt these algorithms for our specific brain tumor dataset, we embark on a reconstruction process to optimize the architecture for better predictions. This reconstruction unfolds in two sequential steps:

-

Image augmentation Initially, we incorporate an image augmentation layer into the input layer of our architecture. This integration allows the architecture to perform on-device image augmentation concurrently with other layers, taking advantage of GPU acceleration for expedited processing. Moreover, by preserving preprocessing layers alongside the model, we ensure instantaneous standardization of images during deployment, eliminating the need for redundant server-side logic.

-

Truncate layers Subsequently, we retain all layers from the TL algorithms, excluding those beyond the last activation layer. This strategic truncation is performed to accommodate the addition of extra layers, optimizing the architecture for efficient brain tumor prediction.

Figure 4 visually illustrates the juxtaposition of the original and reconfigured TL architectures. The original TL architecture highlights the sequential arrangement of layers such as Conv2D, Batch Normalization, ReLU, MaxPooling2D, and the Prediction Layer. The reconfigured TL architecture with fine-tuning, showing the inclusion of additional components such as an Augmentation Layer, Dropout, Flattening, Dense+ReLU, and Dense+SoftMax layers for refined classification of Glioma, Meningioma, and Pituitary brain tumors.

Image augmentation

The image augmentation process is seamlessly integrated into our proposed architecture. Recognizing the pivotal role of image augmentation in enriching dataset scale and diversity, we leverage this technique to amplify the effectiveness of our DL models. Our approach implements image processing techniques on the input images, generating augmented counterparts. The augmentation process encompasses fundamental transformations such as zooming, rotation, contrast adjustment, and horizontal flipping. Additionally, the input images undergo rescaling to a standardized range of 0–1, fostering optimal conditions for model training.

We deliberately incorporated additional random rotations and translations to increase the variety of our augmented dataset and improve the model’s adaptability to different real-world scenarios. The image augmentation process, integrated within the TL architecture, is carried out through carefully adjusted techniques:

-

Horizontal flip function: This function flips the image horizontally at random, applicable to images with a 256 x 256 x 3 dimension, where ’256’ refers to both height and width and ‘3’ signifies the RGB color channels.

-

Random image rotation: Allows the image to rotate randomly, with a limit of 0.25 radians.

-

Image zoom adjustment: Enables random zooming in or out on the image, up to a maximum of 25%.

-

Contrast variation: Alters the contrast of the image randomly, up to a maximum change of 25%.

-

Pixel rescaling: Adjusts the image’s pixel values, rescaling them to a range between 0 and 1.

-

Degree-based image rotation: This function randomly rotates the image, with a maximum rotation of 35°.

-

Image translation with parameters: Randomly shifts the image horizontally and vertically by up to 25% and 35% of the image’s height and width, respectively. The translation uses the ’nearest’ fill mode to handle pixels outside the boundary and ’bicubic’ interpolation for the better visual quality of the transformed image.

In our study, the augmentation techniques were chosen based on a preliminary investigation where we evaluated various augmentation strategies to assess their impact on model training performance. This evaluation included experiments with and without augmentation, as well as comparisons of different augmentation combinations, to measure their influence on accuracy, loss, and generalization capabilities. The selected techniques, such as random rotations, translations, zoom adjustments, and contrast variations, demonstrated significant improvements in validation accuracy (by approximately 2–4%) and reduced overfitting compared to models trained without augmentation. These findings confirmed that the chosen augmentation strategies enhanced the model’s robustness, adaptability to unseen data, and overall performance. Thus, these techniques were integrated into our proposed framework to ensure optimal training conditions.

This meticulously refined augmentation process ensures that the augmented dataset maintains heightened diversity while remaining a faithful representation of original MRI images. The outcome-augmented dataset is the cornerstone for training our presented model, attaining state-of-the-art performance in the targeted task. Consequently, these advanced image-processing strategies augment data proportions and significantly enhance assortment, thereby elevating the overall rendition of DL algorithms.

Fine-tuning process

In the fine-tuning phase, we enhance the architecture by introducing specific layers tailored to the characteristics of brain MRI images. Our refined structural design includes a Global Average Pooling2D layer, two Batch Normalization layers, a Dense layer with ReLU and SoftMax activation, a flattened layer, and a Dropout layer to optimize model performance. The Global Average Pooling2D calculates the average output for each feature map across the entire spatial dimensions, reducing spatial dimensions to 1 x 1, capturing global context, reducing parameter count, and ensuring translation invariance. Batch Normalization standardizes layer inputs, reducing internal covariate shift, enhancing training stability, accelerating convergence, mitigating gradient issues, and providing regularization. The Dense layer followed by ReLU activation introduces non-linearity, enhancing model expressiveness, enabling learning of complex relationships, and capturing intricate patterns. The flattened layer converts the multi-dimensional output into a one-dimensional array, facilitating input compatibility with subsequent layers and ensuring information flow continuity. Dropout randomly deactivates neurons to prevent overfitting, improve generalization, enhance robustness, and reduce overfitting risks. Another instance of Batch Normalization provides additional normalization and regularization, further stabilizing training, enhancing generalization, and contributing to model robustness. The final Dense layer with SoftMax activation produces probability distributions over classes, facilitating accurate classification, and is well-suited for multi-class tasks. Pre-trained trainable weights are incorporated to leverage existing knowledge, and the model is configured with the Adamax optimizer, setting a learning rate of 0.0001 for efficiency in handling embeddings and stability enhancement. The loss function is set to sparse categorical cross-entropy, suitable for integer-form labels obtained through label encoding, with accuracy as the primary performance metric. This comprehensive fine-tuned architecture, with a Flatten and Dropout layer, effectively captures brain MRI data intricacies while addressing overfitting concerns.

Transfer learning algorithms

In our experimentation, we employed four TL algorithms for categorizing brain tumors. Utilizing the knowledge gained from these TL models, we integrated two optimization approaches to tailor the proposed models to our objectives.

-

Xception: The Xception framework, often called “Extreme Inception” is a unique convolutional neural network structure, as described in29. It is distinguished by its depthwise separable convolution layers arranged in a series and the integration of residual connections. The design comprises 36 convolution layers that are grouped into 14 distinct modules. Each module, except for the first and last, is connected through linear residual links. The simplicity of Xception, which is easily implemented using frameworks such as Keras30 or TensorFlow-Slim31, contrasts the complexity of architectures like InceptionV2 or V3.

-

ResNet50V2: The ResNet model, a pioneering neural network introduced by32, has shown remarkable success, notably in the ILSVRC 2015 classification challenge. ResNet50, a variant with 50 layers, uses deep residual networks with “skip connections” for accuracy. The ResNet50V2, an evolution of the original ResNet50, demonstrates better performance on the ImageNet dataset, as noted in33. It introduces an optimized connection structure between blocks, boosting overall performance.

-

ResNet152V2: Building upon the ResNet50 model, ResNet152V2 extends the depth to 152 layers, capturing more complex data features. It maintains the original ResNet’s use of residual blocks and skip connections, proven effective in vision tasks. The model’s design, including skip connections in residual blocks, contributes to its robustness, facilitating the efficient training of deep architectures34.

-

InceptionResNetV2: The InceptionResNetV2 design, an advancement over InceptionResNetV1, combines residual learning with the inception block structure, as outlined in35. It includes various block types like the Stem, InceptionResNet, and Reduction blocks. The network’s depth, achieved through an intricate arrangement of these blocks, ensures high-quality feature extraction and processing, further elaborated in36.

The selection and modification of TL architectures, such as ResNet50V2, ResNet152V2, Xception, and InceptionResNetV2, for brain tumor classification aimed to maximize accuracy while reducing computational complexity. These architectures were chosen for their effectiveness in image classification and ability to capture detailed features. They were adapted to the brain tumor dataset by fine-tuning pre-trained weights and incorporating specific refinements like image augmentation and tailored layers. Rigorous experimentation, including cross-validation and evaluation metrics such as precision, recall, F1-score, and accuracy, validated these modifications. This ensured that the TL architectures effectively captured the nuances of the brain tumor dataset and maintained robust performance.

In our study, we chose Xception and ResNet for their proven success in image classification tasks, particularly in medical imaging, where capturing intricate features is crucial. The Xception architecture, known for its depthwise separable convolution layers and residual connections, was selected due to its efficient representation learning and superior performance on image datasets. Its streamlined design enables effective feature extraction, making it particularly suitable for complex tasks like brain tumor classification. Similarly, ResNet, including its variants ResNet50V2 and ResNet152V2, was chosen for its pioneering use of residual blocks and skip connections, which facilitate the training of deeper networks by mitigating the vanishing gradient problem. The ResNet50V2 and ResNet152V2 models were selected for their ability to capture detailed features from MRI images and their enhanced performance due to improved residual connection structures. These models were adapted for brain tumor classification by fine-tuning pre-trained weights, incorporating image augmentation, and adjusting the architectures to better fit the specific characteristics of the dataset. This careful selection and modification allowed us to achieve high accuracy while reducing computational complexity, ensuring robust and efficient performance in brain tumor classification.

Adopted optimization methods

In our experiment, we use four reconstructed and fine-tuned TL models along with two ensemble approaches: Genetic Algorithm-based Weighted Optimization (GAWO) and Grid Search-based Weighted Optimization (GSWO). These methods enhance prediction accuracy in classifying brain tumors. GAWO leverages natural selection principles, offering a powerful mechanism for exploring complex solution spaces and iteratively adapting model weights. In contrast, GSWO performs an exhaustive search to identify the most effective ensemble combinations. The complementary strengths of these methods drove their selection. GAWO navigates high-dimensional parameter spaces efficiently, meeting the intricate optimization needs of ensemble models. GSWO ensures thorough exploration of potential configurations, increasing the likelihood of finding optimal solutions. By adopting GAWO and GSWO within our ensemble model optimization framework, we aimed to leverage their respective strengths to enhance the accuracy and robustness of our classification system, ultimately contributing to better diagnostic outcomes in the realm of brain tumor classification.

GAWO technique

The GAWO illustrated in Algorithm 1 for constructing an optimal ensemble model for categorizing brain tumors. The objective is to determine the most effective weights for combining predictions from a given set of models to achieve superior accuracy on a designated test dataset. The algorithm initializes with essential parameters, such as the list of models, test dataset, and algorithm-specific settings. Subsequently, it employs a genetic algorithm to iteratively search for the optimal weights by evaluating their impact on ensemble accuracy. The fitness function calculates accuracy based on the weighted average of individual model predictions, emphasizing minimizing negative accuracy in the genetic algorithm. The best weights and their corresponding accuracy are obtained from the genetic algorithm. Finally, the algorithm prints crucial results, including the optimal weights, the best solution’s accuracy, and the ensemble predictions’ accuracy. This approach provides a systematic and automated means of enhancing model performance through weight optimization in ensemble learning scenarios. The weights found using this algorithm are 0.92, 0.87, 0.85, 0.86 for the xception, resnet50v2, resnet152v2 and inceptionresnetv2 respectively.

The fitness function utilized in the genetic algorithm (GA) plays a pivotal role in evaluating potential solutions to the weight optimization problem. Specifically, the fitness function assesses the quality of candidate solutions by quantifying their performance in terms of accuracy on a designated test dataset. For our brain tumor classification task, the fitness function calculates the accuracy of ensemble predictions generated by combining the outputs of individual models weighted according to the candidate solution. The objective is to maximize accuracy, thereby identifying the most effective combination of model weights for achieving superior classification performance. Importantly, the fitness function is designed to assign higher fitness scores to solutions that yield higher ensemble accuracy, incentivizing the GA to converge towards optimal solutions over successive generations.

GSWO technique

The GSWO illustrated in Algorithm 2 for constructing an optimal ensemble model for categorizing brain tumors. The GSWO approach outlines determining optimal weights to construct an ensemble of models with enriched accuracy on a given test dataset. The algorithm takes as input the list of models (modelList), the test dataset (testData), true labels for the test dataset (testLabels), a name parameter (name), and the number of folds for cross-validation (fold). It initializes variables, including the number of models (numModels) and a list of predictions from each model on the test dataset (predictionsList). The algorithm iterates through a grid of weights (weightGrid) generated using linspace and evaluates different weight combinations. For each combination, it calculates ensemble predictions, computes the accuracy of the ensemble, and updates the best weights and accuracy if a higher accuracy is achieved. The final results, including the best weights and accuracy, are printed. This Grid Search-based strategy systematically explores weight combinations to identify the optimal ensemble configuration, offering a straightforward yet effective means of enhancing model performance. The weights found using this algorithm are 0.97, 0.94, 0.91, 0.92 for the xception, resnet50v2, resnet152v2 and inceptionresnetv2 respectively.

While GAs were initially chosen for weight optimization due to their efficiency in exploring complex solution spaces, further experimentation revealed that grid search-based optimization outperformed GAs in terms of both performance and computational time. Grid search systematically evaluates a predefined grid of weight combinations, offering simplicity and transparency in exploring the solution space. This approach proved to be highly effective in identifying optimal ensemble configurations while requiring less computational time compared to GAs. Additionally, grid search exhibited robust performance across different optimization tasks and settings, making it a favorable choice for weight optimization in our ensemble learning framework. Thus, despite the initial consideration of GAs, the superior performance and computational efficiency of grid search ultimately led to its adoption as the preferred optimization technique for weight optimization in our study.

Our hyperparameter tuning process was designed to achieve optimal model performance through a systematic and iterative approach. For our model, we used global average pooling, dense layers, a dropout rate of 0.5, and the softmax activation function. The Adam optimizer was chosen with a learning rate of 1e−4, sparse categorical cross-entropy for the loss function, and a batch size of 32. Hyperparameter tuning was conducted on a predefined set of values to determine the optimal configuration based on validation dataset performance. Additionally, the GAWO and GSWO techniques were applied to fine-tune the weights of the ensemble model, further improving its performance.

Results analysis

Our methodology involves refining the TL architecture by fine-tuning and adding extra layers to boost its efficiency, where we utilized four distinct TL algorithms and developed two ensemble DL models based on optimization techniques. These models were specifically designed to evaluate our approach’s capability in detecting brain tumors. To estimate our strategy’s performance, we used various performance metrics. The following section will provide an in-depth look at the experimental framework, the criteria used for evaluating performance, an analysis of the outcomes, and an extensive review of the results we obtained.

Computational resources

The experiments in this study were conducted on a machine with the following specifications: CPU: Intel Core i7-12700K (12 cores, 20 threads, 3.6 GHz base clock), GPU: NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3090 (24 GB VRAM), RAM: 64 GB DDR4, Storage: 1 TB SSD (NVMe). All models were implemented using Python 3.8 with TensorFlow 2.x and PyTorch libraries for deep learning tasks on Jupyter Notebook. The training and inference processes were performed on the GPU to accelerate model computations, while CPU resources were utilized for data preprocessing and evaluation. Runtime statistics were measured in terms of inference time per image, and the benchmarks were collected after the models were fully trained. This setup provides an efficient environment for conducting large-scale experiments, and the reported inference times are based on this configuration.

Metrics for evaluating

Our methodology’s effectiveness is rigorously evaluated using a range of metrics. These include accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, the confusion matrix, Matthews correlation coefficient (MCC), Kappa, and the Classification Success Index (CSI). Each of these metrics provides a distinct perspective on the model’s ability to classify data accurately.

-

Confusion matrix This matrix format presents the values of True Positives (TP), True Negatives (TN), False Positives (FP), and False Negatives (FN). It serves as a foundation for assessing accuracy, precision, recall, and the F1-score (refer to Table 2).

-

Accuracy This statistical measure evaluates the proportion of correctly identified instances in relation to the overall dataset.

$$\begin{aligned} Accuracy =\frac{TP+TN}{TP+FP+FN+TN} \end{aligned}$$(2) -

Precision This metric calculates the fraction of correctly predicted positive observations out of all the positive predictions made.

$$\begin{aligned} Precision=\frac{TP}{TP+FP} \end{aligned}$$(3) -

Recall Recall, also known as sensitivity, determines the fraction of actual positives that are correctly identified.

$$\begin{aligned} Recall=\frac{TP}{TP+FN} \end{aligned}$$(4) -

F1-score The F1-score is the harmonic mean of precision and recall, providing a balance between these two metrics.

$$\begin{aligned} F1_score=2*\frac{(Recall*Precision)}{(Recall+Precision)} \end{aligned}$$(5) -

Matthews correlation coefficient (MCC) MCC is a reliable statistical rate that evaluates the quality of binary classifications. It ranges from -1 (total disagreement) to 1 (perfect agreement).

$$\begin{aligned} MCC = \frac{(TPTN) - (FPFN)}{\sqrt{(TP+FP)(TP+FN)(TN+FP)*(TN+FN)}} \end{aligned}$$(6) -

Kappa Kappa coefficient indicates the level of consistency between predicted and actual classifications, accounting for random chance.

$$\begin{aligned} Kappa = \frac{(P_o - P_e)}{(1 - P_e)} \end{aligned}$$(7)Here, P_o is the observed agreement, and P_e is the expected agreement by chance.

$$\begin{aligned} P_o = \frac{(TP + TN) }{(TP + TN + FP + FN)} \end{aligned}$$(8)$$\begin{aligned} P_e = \frac{((TP + FP) * (TP + FN) + (TN + FP) * (TN + FN))}{(TP + TN + FP + FN)^2} \end{aligned}$$(9) -

Classification success index (CSI) CSI calculates the ratio of accurately classified instances against the total number of classifications.

$$\begin{aligned} CSI = \frac{TP}{TP+FP+FN} \end{aligned}$$(10) -

Confidence intervals (CI) A CI provides a range of values within which we can be confident that the true performance metric lies, based on the sample test image. The confidence interval gives us an idea of the reliability of the metric calculated from the sample. To calculate the confidence interval for accuracy, we can use the following equation:

$$\begin{aligned} CI = p \pm Z \cdot SE \end{aligned}$$where

-

\(p\) = observed accuracy (as a proportion, \(p = \frac{\texttt {Accuracy}}{100}\))

-

\(Z\) = Z-score corresponding to the desired confidence level (e.g., \(Z = 1.96\) for 95% confidence)

-

\(SE\) = Standard Error, calculated as:

$$\begin{aligned} SE = \sqrt{\frac{p(1 - p)}{n}} \end{aligned}$$where \(n\) is the sample size.

After calculating the standard error, we can derive the lower and upper bounds of the confidence interval:

$$\begin{aligned} \texttt {Lower Bound} = p - Z \cdot SE \\ \texttt {Upper Bound} = p + Z \cdot SE \end{aligned}$$To ensure the confidence interval remains within realistic bounds:

-

Set the lower bound to a minimum of 0%:

$$\begin{aligned} \texttt {Lower Bound} = \max (\texttt {Lower Bound}, 0) \end{aligned}$$ -

Set the upper bound to a maximum of 100%:

$$\begin{aligned} \texttt {Upper Bound} = \min (\texttt {Upper Bound}, 100) \end{aligned}$$

-

-

Paired t-test A paired t-test is a statistical test used to compare the means of two related groups. It is typically used when the same subjects are measured under two different conditions or at two different times. The paired t-test assesses whether the mean difference between paired observations is significantly different from zero. The test statistic for the paired t-test is calculated using the formula:

$$\begin{aligned} t = \frac{\bar{d}}{s_d / \sqrt{n}} \end{aligned}$$Where

-

\(\bar{d}\) is the mean of the differences between paired observations,

-

\(s_d\) is the standard deviation of the differences,

-

\(n\) is the number of pairs.

The null hypothesis is that the mean difference between the pairs is zero, and the alternative hypothesis is that the mean difference is not zero. The test helps determine if there is a statistically significant difference between the two conditions.

-

Evaluation of deep learning models

The performance evaluation of various DL models on brain tumor classification shows significant differences across different configurations, with the models tested under two conditions: with synthetic data generation (SDG) for data balancing and without it (No-SGD). The evaluation metrics include accuracy, precision, recall, F1 score, Kappa, MCC, CSI, confidence intervals, and paired t-test analysis. The results, as presented in Table 3 and Figure 5, demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed models. The GSWO+SDG model consistently outperformed all other configurations in every performance metric. This approach achieved the highest accuracy of 99.84%, precision of 99.84%, recall of 99.84%, F1 score of 99.84%, Kappa of 99.88%, MCC of 99.93%, and CSI of 99.93%. These results highlight the effectiveness of both the GSWO optimization and SDG data balancing techniques in improving the model’s ability to classify brain tumor images accurately. The model’s high accuracy and balanced performance across all metrics make it the most reliable configuration in this study. In comparison, the models without SDG (No-SGD) generally performed at lower levels. For instance, the Xception model, without SDG, achieved an accuracy of 99.42%, precision of 99.43%, recall of 99.42%, and F1 score of 99.43%, showing solid performance but still falling short of the GSWO+SDG configuration. Similarly, ResNet50V2 and ResNet152V2, without SDG, recorded accuracies of 98.37% and 98.22%, respectively. These results suggest that while these models are highly capable, the addition of SDG for data balancing plays a crucial role in enhancing the models’ classification performance. For the models using SDG, there was a noticeable improvement in performance. The ResNet50V2 with SDG achieved an accuracy of 99.48%, precision of 99.48%, recall of 99.48%, and F1 score of 99.48%. The Xception model with SDG reached 99.57% accuracy, precision, recall, and F1 score. While these models demonstrated strong performance, they were still outperformed by the GSWO+SDG approach. GAWO+SDG also performed admirably, with an accuracy of 99.78%, precision, recall, and F1 score of 99.78%, and a Kappa score of 99.86%, further demonstrating the effectiveness of data balancing and optimization techniques.

The paired t-test results reveal a statistically significant improvement in performance when comparing models with and without SDG and optimization techniques. For the GSWO+No-SDG model, the t-statistic is − 2.4370 with a p value of 0.0506, indicating a borderline significance in the difference between the performance of the model with and without SDG. Additionally, for the GSWO+SDG configuration, the t-statistic of − 3.2488 and p value of 0.0227 show a clear and significant enhancement in performance with the combination of SDG and GSWO. These results highlight that while GSWO+No-SDG shows improvement, the addition of SDG provides a more statistically significant boost in the model’s classification accuracy and other performance metrics. In summary, the GSWO+SDG configuration stood out as the top performer across all metrics, achieving the highest classification accuracy and balanced performance. The inclusion of SDG for data balancing played a significant role in improving model performance, as seen with all models that employed it. The GSWO+SDG model not only delivered superior results in terms of accuracy but also in precision, recall, and other important performance metrics, making it the most robust and effective approach for brain tumor classification.

The comparative confusion matrices of the evaluated DL models under two configurations: No-SDG and SDG. In Fig. 6, the models evaluated without synthetic data generation (No-SDG) include Xception, ResNet50V2, ResNet152V2, InceptionResNetV2, GAWO, and GSWO. These confusion matrices reveal that while models like GAWO and GSWO exhibit better performance with fewer misclassifications, models such as Xception and ResNet show higher rates of false positives and false negatives. In Fig. 7, when SDG is applied, significant improvements in model performance are observed. Xception, ResNet50V2, and ResNet152V2, GSWO show more concentrated true positives along the diagonal, indicating improved accuracy. However, the standout performer is GSWO with SDG, which demonstrates superior classification with significantly fewer misclassifications compared to other models. The confusion matrix for GSWO+SDG exhibits minimal off-diagonal values, indicating almost perfect classification across all classes. This indicates that our proposed SDG+GSWO approach outperforms the other models by achieving a higher level of accuracy and significantly reducing misclassifications. Overall, the results from the confusion matrices highlight that the combination of SDG and GSWO provides the most efficient and accurate model for brain tumor classification, outperforming all other models in both true positive predictions and the reduction of misclassifications.

The GSWO model outperforms all other TL and GAWO models, boasting the lowest error rate and high true positive and true negative rates while minimizing false positives and negatives. By systematically exploring weight combinations, GSWO optimally tunes the ensemble, leveraging the strengths of individual models. This exhaustive weight search enhances model synergy, resulting in a finely tuned ensemble that excels in accurately classifying brain tumors and achieving superior performance scores.

The classification report analysis (Table 4) compares the performance of various deep learning models for brain tumor classification under two data configurations: No-SDG and SDG. The table includes precision, recall, and F1-score for the three tumor classes: pituitary, meningioma, and glioma. Under No-SDG, models such as GSWO and GAWO consistently achieve high scores across all classes. GSWO demonstrates exceptional performance with a precision, recall, and F1-score of 99.80 for pituitary and glioma, and 99.60 for meningioma. Other models, like Xception and ResNet50V2, also perform well but show slightly lower values in recall and F1-score, particularly for meningioma. This indicates that while these models are strong, GSWO is the most reliable across all tumor types in the No-SDG configuration. When SDG is applied, there is a noticeable improvement in performance for most models, particularly GSWO, which further enhances its precision, recall, and F1-score to 99.93, 99.80, and 99.87 for pituitary, meningioma, and glioma, respectively. GAWO also improves, with scores reaching 99.87, 99.76, and 99.80, demonstrating its robustness with SDG. Xception, ResNet50V2, and ResNet152V2 show consistent improvements in all metrics, but still lag behind GSWO and GAWO, especially in recall and F1-score for meningioma. Overall, the GSWO with SDG model emerges as the best-performing model across all tumor types, offering superior precision, recall, and accuracy scores, demonstrating the effectiveness of synthetic data generation in improving model performance for brain tumor classification.

Ablation study of our experiment To assess the impact of various components on the performance of our proposed ensemble DL model for brain tumor classification, we conducted an ablation study focusing on model fine-tuning, GAWO, GSWO, and the integration of SDG. First, we evaluated the fine-tuned TL models individually, achieving an accuracy of 99.42%, establishing a strong baseline for brain tumor classification. Incorporating GAWO into the ensemble framework enhanced performance to 99.71%, demonstrating the effectiveness of weight optimization in improving the ensemble model’s learning and generalization capabilities. Next, the application of GSWO further refined the model, yielding an accuracy of 99.76%. GSWO systematically optimized hyperparameters and assigned weights to TL models, resulting in improved balance and precision. The inclusion of SDG brought notable advancements. When SDG was combined with Xception, the performance improved to 99.57%, highlighting its ability to address data imbalance issues. Similarly, combining SDG with GAWO achieved an accuracy of 99.78%, surpassing the prior GAWO results. Finally, the integration of SDG with GSWO achieved the highest accuracy of 99.84%, with enhanced precision, recall, and F1 scores across all tumor classes. The ablation study underscores the incremental benefits of each component. While GAWO and GSWO significantly contribute to optimization, the addition of SDG amplifies the robustness and generalization of the model, particularly in handling class imbalances. These findings validate the synergistic effect of SDG and GSWO, affirming the efficacy of our proposed ensemble DL framework in brain tumor classification.

Performance test measurement Fig. 8 presents an analysis of test performance showcasing our efficient ensemble (SDG+GSWO) model in brain tumor classification tasks. By visualizing the performance for several sample images, we demonstrate the model’s effectiveness, achieving perfect predictions for all samples.

K-fold CV results

K-fold cross-validation is a technique used to assess the generalization ability of a model by splitting the dataset into K subsets and iteratively training and testing the model on different combinations of these subsets. This process helps ensure that the model performs consistently and is not overfitting to a particular subset of the data. In our experiment, we used a 5-fold cross-validation strategy, where each fold comprised an 80% training set and a 20% testing set. To assess the robustness of our model against overfitting and its generalizability across different datasets, we performed K-Fold Cross Validation (CV) with K = 5 on both balanced and imbalanced datasets. This procedure allowed us to validate the model’s performance on multiple subsets of the data, ensuring that it is not overly sensitive to the specific distribution of the data in any one training or validation set. Table 5 presents the results, demonstrating consistent performance across all folds, indicating that the model is not overfitting and can generalize well. For example, when using the No-SDG dataset, the average accuracy of the GSWO model was 99.76%, with accuracy scores ranging from 99.72% to 99.80% across the different folds. Similarly, when using the SDG dataset, the GSWO model achieved an average accuracy of 99.84%, with accuracy scores between 99.82% and 99.86%, further confirming the model’s stability. The inclusion of additional results from cross-validation datasets also highlights the generalizability of the model across different splits of the data. The relatively narrow range of the accuracy scores across the different folds for both the No-SDG and SDG datasets indicates that the model performs consistently well, regardless of the specific data subset used for training or validation. These findings reinforce the effectiveness of our approach and demonstrate that the model is not only accurate but also robust against overfitting, ensuring reliable performance in real-world applications. Furthermore, the results from the SDG dataset, which consistently outperforms the No-SDG dataset, affirm that the use of synthetic data generation enhances the model’s ability to generalize, providing more diverse training examples and improving overall performance. This comprehensive validation through K-Fold CV ensures that our model is both accurate and robust, capable of delivering reliable predictions across a variety of conditions and independent datasets.

Grad-CAM visualization

Gradient-weighted Class Activation Mapping (Grad-CAM) is a visualization technique that highlights the most critical areas in an input image that influence a model’s prediction for a specific class of interest. The process begins by passing the input image through the deep neural network to obtain class prediction scores (forward pass). Next, backpropagation is used to compute the gradients of the target class score concerning the feature maps of the model’s last convolutional layer. These gradients reflect the importance of each feature map, allowing the model to focus on relevant areas of the image that contribute to the classification decision.

In this study, we applied Grad-CAM to several test images and real-time brain tumor images to visualize and classify tumor types. Our goal was to identify and highlight the relevant areas of the image that the model focused on for the tumor classification task. We utilized our ensemble model (SDG+GSWO), based on multiple TL architectures, and selected the final convolutional layer for Grad-CAM implementation. The input images were resized to fit the model’s specifications, and gradients for the target tumor class were computed to weight the feature maps generated from the last convolutional layer. To ensure that only positive contributions to the class score were considered, we applied a ReLU function to the weighted feature maps. The resulting heatmap was then overlaid on the original image to visualize which parts of the brain tumor contributed most significantly to the classification decision. We fine-tuned the transparency of the heatmap to enhance the visibility of the tumor class while minimizing the inclusion of healthy tissue areas. This approach provides a clear and interpretable view of how our model detects and classifies different tumor types. The resulting visualizations not only demonstrate the model’s accuracy but also build trust in its predictions by visually linking them to the specific tumor classifications in the images. Fig. 9 illustrates the Grad-CAM visualizations, highlighting the model’s focus on tumor classes of interest and enhancing the explainability of its decisions.

Evaluation of computational complexity

To assess the computational efficiency of our proposed models, we evaluated their inference times with and without the application of SDG (Synthetic Data Generation). Table 6 displays the effect of SDG on inference times. On average, the models with SDG exhibited slightly higher inference times compared to their counterparts without SDG. For instance, Xception took 18 s for inference without SDG, and 20 seconds with SDG, reflecting a marginal increase in computational demand. Similarly, models like ResNet152V2 and InceptionResNetV2 showed a noticeable rise in inference times with SDG, increasing from 20 to 23 s, and 21–24 s, respectively. However, GSWO demonstrated a smaller increase in inference time, going from 15 to 17 s, indicating its relatively lower computational complexity. These results provide a clear trade-off between model performance and computational cost. While SDG leads to marginally higher inference times, the improvements in model accuracy, justify the additional computational effort for most use cases. The slight increase in inference times with SDG suggests that the proposed models remain computationally feasible for real-world applications while providing superior classification performance.

Discussion

The comparative analysis, presented in Table 7, highlights the performance of our proposed method against several existing state-of-the-art (SOA) approaches for brain tumor categorization using the Brain CE-MRI dataset. Our method, which integrates SDG and GSWO, achieves a remarkable accuracy of 99.84%, outperforming all the referenced works. Notably, methods like EfficientNetB3 used by Islam et al.19 (99.69%) and Sadad et al.11 utilizing NASNet (99.60%) also demonstrate strong performance. However, our approach surpasses these models by effectively addressing data imbalances and optimizing model weights through advanced SDG and GSWO techniques. Ensemble approaches, such as the one by Nassar et al.15 and the Majority Voting method24, achieve accuracies of 99.31%, which is slightly lower than our proposal. While ensemble techniques inherently combine the strengths of multiple models, their computational complexity and inference time often pose challenges, particularly in real-time applications. Moreover, traditional CNN-based approaches like those of Ayadi et al.27 (94.74%) and Saeedi et al.25 (96.47%) yield comparatively lower accuracies, demonstrating the limitations of simpler architectures in handling the complex spatial patterns present in brain tumor images. Similarly, optimized CNNs and NASNet-based methods, despite showing competitive results, fail to match the robustness and generalization capabilities achieved by our ensemble (SDG+GSWO) framework. The incorporation of SDG not only enriches the training data but also addresses class imbalance, a common issue in medical imaging datasets. GSWO further enhances model performance by systematically fine-tuning weights to minimize loss, ensuring both high accuracy and reduced overfitting. Our proposed framework’s superiority in accuracy and generalization is complemented by its computational efficiency. By leveraging advanced techniques, our approach strikes a balance between performance and complexity, making it a strong candidate for real-world applications in medical imaging.

The novelty of our work lies in the integration of advanced SDG techniques and a tailored GSWO framework to enhance brain tumor classification using CE-MRI images. Our approach introduces a reconfigure-and-fine-tuning methodology with enhanced TL architectures, incorporating advanced image augmentation and standardization techniques to mitigate overfitting and streamline the classification process. The GSWO framework optimizes ensemble model weights, ensuring balanced contributions from each model, and thereby improving generalization and accuracy. Additionally, SDG addresses data imbalance by generating synthetic samples, enhancing the representation of underrepresented classes, and enabling robust training. Achieving a state-of-the-art accuracy of 99.84%, our framework surpasses existing methodologies, offering a scalable and effective solution for medical imaging classification with significant implications for improving diagnostic precision and efficiency.

Our ensemble (SDG+GSWO) model demonstrates excellent scalability for real-time applications due to its efficient ensemble optimization approach. By leveraging the GSWO method, the model dynamically adjusts weights across multiple TL architectures, ensuring robust and accurate classification of brain tumors across all classes. This optimization enables the model to maintain high accuracy when applied to real-time test scenarios (Fig. 8). Additionally, the streamlined nature of the GSWO-based ensemble allows for faster inference times. As demonstrated in our experiments (Table 6), the model achieves prediction speeds of 17 seconds, outperforming other architectures such as Xception and ResNet152V2. This makes it highly suitable for real-time detection tasks, where timely and precise diagnosis is critical. The model’s adaptability, combined with its predictive reliability across all classes, ensures scalability and effectiveness, making it a practical solution for real-time medical applications, such as in hospitals or diagnostic centers, where quick and accurate decision-making is essential.

Potential impact in healthcare and society

The core objective of our study is the development of an advanced deep-learning model dedicated to accurately classifying brain tumors, utilizing the strengths of deep learning to discern various tumor types with high precision. The potential impacts of this research are extensive, particularly in neuro-oncology, encompassing several clinically significant applications. Firstly, it offers an improved diagnostic tool for radiologists and medical professionals, aiding in the accurate diagnosis of brain tumors through techniques such as MRI scans. By providing reliable tumor categorization, the model reduces diagnostic errors and promotes early detection, thereby improving patient treatment outcomes. Additionally, the precise identification of tumor types facilitates the formulation of tailored treatment plans, ensuring patients receive targeted therapies that are more effective, thereby enhancing overall healthcare quality. Moreover, the model serves as a critical support tool in clinical decision-making processes, furnishing healthcare professionals with accurate information for better patient management and delivering more personalized patient care. Furthermore, by accurately classifying brain tumors and identifying specific genetic markers or molecular profiles, the model significantly contributes to brain tumor research, aiding in understanding tumor biology, identifying therapeutic targets, and advancing the development of optimized treatments and medications. In summary, our research offers substantial benefits in enhancing brain tumor diagnosis and treatment, supporting clinical decision-making, aiding surgical procedures, and advancing medical research, with the potential to positively influence both patient care and societal health outcomes.

Conclusion

This research presents an innovative DL framework for the accurate classification of brain tumors using CE-MRI images. The proposed methodology integrates advanced preprocessing techniques, SDG to address data imbalances, and fine-tuned ensemble strategy leveraging TL architectures and weights optimization. By utilizing four state-of-the-art TL models-Xception, ResNet50V2, ResNet152V2, and InceptionResNetV2-alongside GSWO and GAWO, our framework achieves exceptional performance on the Figshare CE-MRI brain tumor dataset.

The evaluation encompassed multiple performance metrics, including accuracy, precision, recall, F1 score, confusion matrix, MCC, Kappa, and CSI, underscoring the robustness of our approach. Individual models such as Xception and ResNet50V2 achieved accuracies of 99.57% and 99.48%, respectively, while ensemble techniques demonstrated further improvements, with GAWO achieving 99.78% accuracy and GSWO excelling at 99.84%. The integration of SDG significantly enhanced the representation of underrepresented classes, improving training robustness and contributing to superior overall performance (99.71–99.84%). Thus our Ensemble (SDG+GSWO) model offers promising clinical applications for precise and reliable brain tumor classification, aiding radiologists in early diagnosis and treatment planning by improving accuracy in identifying complex tumor characteristics.

While the proposed model demonstrates high accuracy and reliability, there are opportunities for improvement by exploring more advanced DL techniques such as attention-based models, transformer-based models and deep feature fusion techniques could help perfect way of classification and segmentation tasks of brain tumors.

Future work will focus on addressing these limitations to get better performance models by incorporating more sophisticated attention-based models, transformer-based models and deep feature fusion techniques from recently available brain tumor datasets.

Data availability

The selected datasets are sourced from free and open-access sources such as Figshare MRI Brain tumor Dataset: https://figshare.com/articles/dataset/brain_tumor_dataset/1512427.

Code availability

The source code for this study is publicly accessible at the following repository: https://github.com/alamintalukdercsejnu/BTC-DL.

References

Engelen, T., Solcà, M. & Tallon-Baudry, C. Interoceptive rhythms in the brain. Nat. Neurosci. 26(10), 1670–1684 (2023).

Cinar, N., Kaya, M. & Kaya, B. A novel convolutional neural network-based approach for brain tumor classification using magnetic resonance images. Int. J. Imaging Syst. Technol. 33(3), 895–908 (2023).

Salari, N. et al. The global prevalence of primary central nervous system tumors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Med. Res. 28(1), 39 (2023).

Shamshad, N. et al. Enhancing brain tumor classification by a comprehensive study on transfer learning techniques and model efficiency using MRI datasets. IEEE Access 12, 100407–100418 (2024).

Aljahdali, S. et al. Effectiveness of radiology modalities in diagnosing and characterizing brain disorders. Neurosci. J. 29(1), 37–43 (2024).

Rasa, S. M. et al. Brain tumor classification using fine-tuned transfer learning models on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) images. Digit. health 10, 20552076241286140 (2024).

Alshuhail, A. et al. Refining neural network algorithms for accurate brain tumor classification in MRI imagery. BMC Med. Imaging 24(1), 118 (2024).

Berghout, T. The neural frontier of future medical imaging: A review of deep learning for brain tumor detection. J. Imaging 11(1), 2 (2024).

Priya, A. & Vasudevan, V. Advanced attention-based pre-trained transfer learning model for accurate brain tumor detection and classification from MRI images. Opt. Mem. Neural Netw. 33(4), 477–491 (2024).

Dewi, C., Christanto, H. & Dai, G. Automated identification of insect pests: A deep transfer learning approach using ResNet. Acadlore Trans. Mach. Learn 2(4), 194–203 (2023).

Sadad, T. et al. Brain tumor detection and multi-classification using advanced deep learning techniques. Microsc. Res. Tech. 84(6), 1296–1308 (2021).

Qureshi, I. et al. Medical image segmentation using deep semantic-based methods: A review of techniques, applications and emerging trends. Inf. Fusion 90, 316–352 (2023).

Al-Zoghby, A. M., Al-Awadly, E. M. K., Moawad, A., Yehia, N. & Ebada, A. I. Dual deep CNN for tumor brain classification. Diagnostics 13(12), 2050 (2023).

Emam, M. M., Samee, N. A., Jamjoom, M. M. & Houssein, E. H. Optimized deep learning architecture for brain tumor classification using improved hunger games search algorithm. Comput. Biol. Med. 160, 106966 (2023).

Nassar, S. E., Yasser, I., Amer, H. M. & Mohamed, M. A. A robust MRI-based brain tumor classification via a hybrid deep learning technique. J. Supercomput. 80(2), 2403–2427 (2024).

Agarwal, M. et al. Deep learning for enhanced brain tumor detection and classification. Results Eng. 22, 102117 (2024).

Talukder, M. A. et al. An efficient deep learning model to categorize brain tumor using reconstruction and fine-tuning. Expert Syst. Appl. 230, 120534 (2023).

Dahan, F. Transformation of MRI images to three-level color spaces for brain tumor classification using deep-net. Intell. Autom. Soft Comput. 39(2), 381–395 (2024).

Islam, M. M., Talukder, M. A., Uddin, M. A., Akhter, A. & Khalid, M. BrainNet: Precision brain tumor classification with optimized efficientnet architecture. Int. J. Intell. Syst. 2024(1), 3583612 (2024).

Tummala, S., Kadry, S., Bukhari, S. A. C. & Rauf, H. T. Classification of brain tumor from magnetic resonance imaging using vision transformers ensembling. Curr. Oncol. 29, 7498–7511 (2022).

Abd El-Wahab, B. S., Nasr, M. E., Khamis, S. & Ashour, A. S. BTC-fCNN: Fast convolution neural network for multi-class brain tumor classification. Health Inf. Sci. Syst. 11(1), 3 (2023).

Maruf, A. et al. Evaluating the performance of transfer-learning approaches for multiclass classification of glioma, meningioma and pituitary tumour. Afr. J. Med. Phys. 4(1), 63–68 (2022).

Asif, S., Zhao, M., Tang, F. & Zhu, Y. An enhanced deep learning method for multi-class brain tumor classification using deep transfer learning. Multimed. Tools Appl. 82, 1–28 (2023).

Nassar, S. E., Yasser, I., Amer, H. M. & Mohamed, M. A. A robust MRI-based brain tumor classification via a hybrid deep learning technique. J. Supercomput. 80, 1–25 (2023).

Saeedi, S., Rezayi, S., Keshavarz, H. & Kalhori, S. MRI-based brain tumor detection using convolutional deep learning methods and chosen machine learning techniques. BMC Med. Inf. Decis. Mak. 23(1), 16 (2023).

Ait Amou, M., Xia, K., Kamhi, S. & Mouhafid, M. A novel mri diagnosis method for brain tumor classification based on CNN and Bayesian optimization. In Healthcare, Vol. 10 494. MDPI (2022).

Ayadi, W., Elhamzi, W., Charfi, I. & Atri, M. Deep CNN for brain tumor classification. Neural Process. Lett. 53(1), 671–700 (2021).

Cheng, J. Brain magnetic resonance imaging tumor dataset. Figshare MRI Dataset Version 5 (2017).

Chollet, F. Xception: Deep learning with depthwise separable convolutions. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 1251–1258 (2017).

Joseph, F. J. J., Nonsiri, S. & Monsakul, A. Keras and tensorflow: A hands-on experience. In Advanced Deep Learning for Engineers and Scientists: A Practical Approach (eds Prakash, K. B. et al.) 85–111 (Springer, Berlin, 2021).