Abstract

We aimed to determine the spinopelvic profile types of ambulatory adolescents and adults with diplegic CP, and their relationship with functional ability (Gross Motor Function Classification System [GMFCS]), pain, and previous orthopaedic treatments. We measured anatomical variables on radiographs from 77 individuals with CP (mean age, 28.4, SD, 11.9 years), GMFCS levels I–III. We applied a non-supervised hierarchical ascendant classification followed by k-medoids analysis to 5 key anatomical variables. We compared radiological and clinical variable values between the spinopelvic profiles identified. Three spinopelvic profiles emerged, according to whether the pelvis was anteverted (sacral slope ≥ 38°) or retroverted (< 38°) and whether this was concordant with the pelvic incidence (≥ 54° for anteversion and < 54° for retroversion). Most (61/77, 79%) participants had anteversion, concordant for only 28/61 (46%); 16/77 (21%) had retroversion, concordant for 14/16 (88%). More participants with concordant anteversion experienced pain than participants with discordant anteversion (P = 0.03). Rates of previous treatments did not differ between concordant and discordant anteversion. More participants with GMFCS level III had discordant anteversion than those with levels I–II (P = 0.02). Categorising the spinopelvic profile is the first step to understanding pain causes and proposing targeted interventions and/or rehabilitation programs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Spinopelvic alignment1 may be altered in children and adolescents with cerebral palsy (CP). Proper spinopelvic alignment is economical in terms of the mechanical effects on the body and the associated muscle energy requirements2,3. Spinopelvic imbalance has been suggested to cause spinal degeneration4. The prevalence of osteoarthritis is higher in individuals with than without CP5 and may be a cause of pain6,7.

Spinopelvic alignment and the factors that influence spinal-pelvic organisation have been little studied in adults with CP. Very few studies have been performed in ambulatory individuals with diplegic or quadriplegic CP: the results showed significant differences in pelvic variables and lumbar lordosis between people with and without CP8,9.

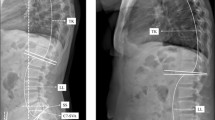

Spinopelvic alignment is often evaluated by measuring 3 main variables: pelvic incidence (PI), sacral slope (SS) and pelvic tilt (PT). PI is an anatomical parameter, whereas SS and PT define the orientation of the pelvis in relation to the vertical or horizontal planes (Fig. 1). Previous studies demonstrated how PI defines the sagittal curves of the spine1,10,11: the greater the PI, the greater the overhang between the sacrum and the femoral heads and the more pronounced the lumbar lordosis, which allows the centre of gravity to be maintained between the femoral heads and the sacral plate.

Illustration of pelvic variables and their relationships11. PI pelvic incidence, PT pelvic tilt, SS: sacral slope.

In healthy individuals, Roussouly et al. found a strong correlation between PI and SS. Individuals with an SS < 35° had a low PI and a relatively flat, short lordosis while those with an SS > 45° had a high PI and a long, curved lordosis1. However, in our clinical experience, the physiological parameters of the pelvis and spinal shape frequently do not match in individuals with CP: many individuals with a low PI have a high SS. Therefore, the pelvis is inappropriately anteverted (usually with a large lordosis), resulting in an unbalanced spinopelvic complex.

Accurate data on spinopelvic balance would be useful to both researchers and clinicians to highlight the functional repercussions of different spinal types. This could guide early rehabilitation and orthopaedic treatment to limit the consequences of CP on spinal development, spinal ageing and pain.

Methods

Aim

This exploratory study was based on the clinical hypothesis that specific spinopelvic profiles exist among ambulatory adolescents and adults with diplegic CP. The specific aims were (1) to describe and classify the spinopelvic profiles of ambulatory adolescents and adults with diplegic CP, and (2) to describe pain, functional level (Gross Motor Function Classification System [GMFCS]), the gait pattern and previous orthopaedic-type treatments for each spinopelvic profile identified.

Design

We conducted a retrospective, cross-sectional single-centre study between April 2014 and February 2020. Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee of Catholic University of Lille (Université Catholique de Lille) on 19 December 2019 (No. CIER-2019-44). The study was performed in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki. Due to the retrospective nature of the study, the Ethics Committee of the Catholic University of Lille waived the need for obtaining informed consent. All individuals who attend our centre are informed that their data may be used for research purposes and can refuse this. The study is reported according to the STROBE guidelines.

Recruitment

Participants were recruited from one rehabilitation centre of excellence for both CP and spinal problems. We used the PMSI (program for the medicalisation of information systems) coding system to identify potentially eligible participants.

Inclusion criteria were age between 16 and 70 years, with spastic, diplegic CP, GMFCS levels I, II or III (ambulatory), and with available sagittal, standing radiographs of sufficient quality for a complete analysis.

Procedure

Evaluations were performed at the time that full radiographic data were available for the individual.

Imaging

Radiographic imaging was performed as part of the usual follow-up. A standardized protocol was used, including sagittal images of the whole spine and proximal femur.

The images were analysed by experienced physiatrists and an orthopaedic surgeon using Keops® software12. Only the femoral obliquity angle was obtained by direct measurement using a free measurement software function.

Data collection

We collected the following anatomical variables:

Pelvic variables

-

pelvic incidence (PI): the angle between the perpendicular of the sacral plate and the line joining the middle of the sacral plate and the hip axis. In asymptomatic individuals, the mean (SD) value is 55° (10°)10,13. PI is considered an anatomical constant, and it determines the capacity of adaptation to spinal shape: a large PI allows a large degree of posterior pelvic tilt, whereas a small PI does not.

-

pelvic tilt (PT): the angle between the vertical line and the line joining the middle of the sacral plate and the hip axis. In asymptomatic individuals, the mean angle is 13° (6°)13.

-

sacral slope (SS): the angle between the sacral plate and the horizontal line. In asymptomatic individuals, the mean value is 41° (8°)13.

The relationship between these 3 variables is summarised by the formula PI = SS + PT.

Spinal variables

-

functional lumbar lordosis angle: sagittal Cobb angle measurement from the sacral endplate to the superior end plate of the first vertebra included in the lumbar lordosis, which may not be L1, as the inflexion point may be above or below T12 and L114

-

number of vertebrae included in the functional lordosis and functional kyphosis

Spinal alignment variable

-

spinal sacral angle (SSA): the angle between the superior surface of the sacrum and the horizontal line. In asymptomatic individuals, the mean angle is 135° (SD 8°)15. This variable provides an overall description of spinopelvic alignment.

Lower limb variable

-

femoral obliquity angle (FAO): the angle between an axis through the shaft of the femur and a line perpendicular to the intercondylar plane. The normal value is around 0°.

Demographic and clinical data

We collected anthropometric data, GMFCS level and gait-type (video analysis)16, pain ratings for lower limbs or back pain (VAS from 0 to 10), and previous treatment for the lower limbs or back from medical records.

Statistical analysis

Unsupervised classification

An unsupervised classification was performed to define clusters of homogeneous participants. We included 5 variables: 3 commonly used anatomical variables to describe spinopelvic alignment, PI, SS and PT1, and 2 variables that we considered to be relevant descriptors of spinopelvic balance and position: respectively, SSA and FOA.

First, a hierarchical ascendant classification (HAC) (based on Euclidean distance and Ward’s method) was performed. To determine the number of clusters, the elbow method was used. This consists of plotting the explained variation at each step of the HAC and identifying the elbow of the curve as the number of optimal clusters to use. The K-medoids method was then applied, beginning with the HAC redistribution, to further validate and specify the results of the HAC. The clusters obtained from the unsupervised classification were compared using analysis of variance (ANOVA).

Allocation rule

To determine a rule for allocating a participant to the cluster obtained from the unsupervised classification, a classification tree method (supervised classification) was used with the same 5 variables. This method created binary decision rules that split the data into groups, which could then be used to assign new individuals to those groups.

Comparison of subgroups

Subgroups were defined from the rules issued from the classification tree: ante- and retroversion were defined according to the SS value, and concordant and discordant anteversion were defined according to the PI value.

These subgroups were compared using a Student t test if variables were normally distributed and Wilcoxon-Mann-Witney tests otherwise. For quantitative variables, a Chi-square test was used, or in case of low numbers, a Fisher exact test.

Participants with GMFCS levels I and II were grouped together (both levels indicate independent walking ability) and compared to those with GMFCS level III (requiring gait aids).

Statistical analyses were carried out using R software (version 3.6.1) and P < 0.05 was considered significant for all analyses.

Results

Among the 96 individuals with CP followed in our cohort, 2 had GMFCS level IV, 2 had an uncertain diagnosis, 13 did not have radiographs of the full spinal column, 1 had radiographs in sitting and 1 had non-centred sagittal radiographs; therefore 77 individuals were included.

Spinopelvic classification

This analysis was performed on the 71 participants without missing data. The elbow method, based on the scree plot of the interclass inertia variation, distinguished 3 groups. The resulting distribution of the participants was then consolidated with the k-medoids method. The 3 groups are compared in Table 1.

Allocation rule

A classification tree was used to determine the best rules to allocate a participant to one of the 3 groups. The rules were all based on PI or PI and SS because no pattern was identifiable for PT, SSA or FOA:

-

Group 1: PI ≥ 54°

-

Group 2: PI < 54°, SS ≥ 38°

-

Group 3: PI < 54°, SS < 38°

In clinical terms,

-

SS ≥ 38° indicates pelvic anteversion and < 38° indicates pelvic retroversion.

-

Anteversion is concordant if PI ≥ 54°. Retroversion is concordant if PI < 54°.

Therefore the 3 profiles were:

-

Concordant anteversion

-

Discordant anteversion

-

Concordant retroversion

This rule was then applied to the total sample of 77 participants. Most participants had pelvic anteversion (n = 61, 79%), which was concordant for almost half (n = 28). Of the 16 participants with retroversion, it was mostly concordant (n = 14).

Clinical characteristics of the whole sample of 77 participants (Table 2)

Most participants had pain. Most walked independently with a true equinus or crouch gait. Most had undergone previous orthopaedic surgery and around half had received botulinum toxin injections.

Comparison of variables between the ante- and retroversion groups (Table 2)

Functional lumbar lordosis was more pronounced in the group with anteversion than the group with retroversion (P < 0.0001), and more vertebrae were included in the lordosis. SSA was also greater (P < 0.0001) and FOA smaller, though not significantly (P = 0.06).

Pain ratings, previous treatments and the gait pattern did not differ between the ante- and retroverted groups.

The proportion of individuals with anteversion was higher in the group with GMFCS levels I and II than level III (P = 0.02).

Comparison of variables between concordant and discordant anteversion (Table 3)

SSA was higher (P = 0.003), and lumbar lordosis was larger (P = 0.005) in the group with CA than in the group with DA.

The proportion of participants with pain was higher in the group with CA (P = 0.03).

There was no difference in previous treatments or the gait pattern between the CA and DA profiles.

The proportion of participants with DA was significantly higher in those with GMFCS level III than those with levels I–II (P = 0.02).

Discussion

This study confirmed a clinical observation that distinct spinopelvic profiles could be identified in adults and adolescents with diplegic CP. PI and SS best distinguished between profiles, with specific threshold values. We identified 3 types of spinopelvic profiles according to whether the pelvis was anteverted or retroverted and whether this was concordant with the PI or not (for anteversion only). Most participants had pelvic anteversion, despite a low PI value, which is physiologically discordant.

The HAC and k-medoids analysis found a threshold value for SS of 38°. This is very close to the 35° defined by Roussouly et al.1, demonstrating that this cut-off value can be used to define ante- and retroversion in people with CP.

Comparison of our results with data in the literature was limited by the few available studies of spinopelvic alignment in adolescents and adults with CP. The values of the PI, SS, LL and SSA were similar to those found by Suh et al.8.

Of those with pelvic anteversion, more than half had a low PI. Therefore, the anteversion was physiologically discordant and certainly caused by the pathology. Similar findings have been reported in children with CP17. The non-physiological anteversion is likely caused by a shortening of the hip flexor muscles and weakness of the hip extensors. Anteversion could also compensate for abnormal positioning of the flexion/extension force vector at the knee due to distal impairment (equinus) to maintain balance.

Although not statistically significant, a higher proportion of participants with retroversion had a crouch gait. Several hypotheses can explain this. These individuals typically use a walker and gait with a walker reduces the need for pelvic anteversion to project the centre of gravity anteriorly. Furthermore, crouch gait is usually associated with hamstring contractures which could contribute to pelvic retroversion.

A high proportion (62%) of the participants had spine and/or lower limb pain. This finding is consistent with other reports6,18. Unexpectedly, pain was more frequent in those with CA than DA. This could be explained by the high SS and associated large lordosis that increases shear stresses on the posterior joints, particularly at the lumbosacral junction. Excessive anteversion and an SS > 45° increase the risk of spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis19. Pain may also be caused by the considerable eccentric work of the posterior muscles to maintain posture and balance. Furthermore, the group with CA had better functional abilities; they could walk without assistance (GMFCS levels I and II). A higher level of mobility likely puts higher levels of strain on the lower limbs and spine. This is supported by the fact that spondylolisthesis appears to be more common in individuals with higher levels of ability20 than those who have never been ambulatory21. Future studies should investigate the effects of targeted rehabilitation programs involving muscle strengthening on pain in this group.

A higher proportion of participants with GMFCS levels I–II had anteversion than those with level III (Table 2). Furthermore, a higher proportion of those with GMFCS levels I–II had CA (Table 3). These findings are in accordance with the results of a study in children with CP (mean age 12 years) that showed that mean pelvic tilt was anterior for GMFCS levels I and II and posterior for levels III and IV22, as these children are mostly seated.

The proportion of participants who had undergone orthopaedic surgery or botulinum toxin injections was similar across the profile groups. Although deep analysis of this was beyond the scope of the study, the high prevalence of DA suggests that these treatments may have been insufficient to restore or maintain coherent spinopelvic alignment, for example by reducing the progression of hip flexor contractures during growth. However, they did not seem to destabilise the spinopelvic balance since there were no differences between the CA group and DA groups regarding previous surgery. Some evidence suggests that early and prolonged treatment could reduce discordance between PI and SS23. Future studies should investigate the effects of long-term treatments to improve DA, such as repeated botulinum toxin injections into the hip flexor muscles and the use of a brace over several years. During decision making for multisite orthopaedic surgery at adolescence, hip flexor muscle lengthening to improve DA might be considered.

This study has several limitations. The sample was relatively small (n = 77); therefore, we may not have captured the full scope of the possible radiographic profiles. We performed multiple statistical comparisons without correction which may have affected the results for the associations between GMFCS level and pain and type of anteversion. Furthermore, although it was relatively homogeneous in terms of ambulatory capacity, the distribution of spinopelvic profile types was heterogeneous and prevented comparison between all the groups, particularly those with retroversion. However, this distribution may reflect the reality of the prevalence of each spinopelvic profile type in adolescents and adults with CP. This should be confirmed by further research on a larger cohort. Using the SSA as the only sagittal balance parameter was limiting because it does not account for compensations in the pelvis, knees, and ankles, which are common in people with cerebral palsy. The SSA is a pragmatic choice in standard radiography for people with cerebral palsy where spinal and pelvic deformities can make it difficult to measure other parameters like CAH-HA or T1 tilt, which require precise anatomical landmark definitions. The sagittal vertical axis would have been a better “functional” indicator, however, the SSA provides an initial indication of sagittal balance for a static, reproducible, global analysis, which was the aim of our study.

Conclusions

Using the PI and SS, this study found 3 categories of spinopelvic profile (CA, DA and CR) in ambulatory adolescents and adults with diplegic CP. Anteversion was most common in those with higher levels of function (GMFCS I–II); however, this group also had the highest frequency of pain.

It is important to identify spinopelvic profiles, particularly non-physiological profiles such as DA, in young children to apply appropriate treatments early. Those with CA may have a significantly higher risk of developing pain; early targeted rehabilitation programmes involving muscle strengthening should be proposed.

Longitudinal studies should evaluate specific spinopelvic profiles to better understand the development of discordant profiles, the impact of childhood treatments on spinopelvic balance in adulthood, loss of function, and the need for surgery.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Roussouly, P., Gollogly, S., Berthonnaud, E. & Dimnet, J. Classification of the normal variation in the sagittal alignment of the human lumbar spine and pelvis in the standing position. Spine 30, 346–353 (2005).

Duval-Beaupere, G., Schmidt, C. & Cosson, P. A barycentremetric study of the safittal shape of spine and pelvis: The conditions required for an economic standing position. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 20, 451–462 (1992).

Duval-Beaupere, G. et al. Sagittal profile of the spine prominent part of the pelvis. Stud. Health Technol. Inform. 88, 47–64 (2002).

Roussouly, P. & Pinheiro-Franco, J. L. Biomechanical analysis of the spino-pelvic organization and adaptation in pathology. Eur. Spine J. 20(Suppl 5), 609–618 (2011).

French, Z. P., Torres, R. V. & Whitney, D. G. Elevated prevalence of osteoarthritis among adults with cerebral palsy. J. Rehabil. Med. 51, 575–581 (2019).

Mckinnon, C. T., Morgan, P. E., Harvey, A. R. & Antolovich, G. C. Prevalence and characteristics of pain in children and young adults with cerebral palsy: A systematic review. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. https://doi.org/10.1111/dmcn.14111 (2018).

Jahnsen, R., Villien, L., Aamodt, G., Stanghelle, J. K. & Holm, I. Musculoskeletal pain in adults with cerebral palsy compared with the general population. J. Rehabil. Med. 36, 78–84 (2004).

Suh, S. W., Suh, D. H., Kim, J. W., Park, J. H. & Hong, J. Y. Analysis of sagittal spinopelvic parameters in cerebral palsy. Spine J. 13, 882–888 (2013).

Massaad, A. et al. Three-dimensional evaluation of skeletal deformities of the pelvis and lower limbs in ambulant children with cerebral palsy. Gait Posture 49, 102–107 (2016).

Legaye, J., Duval-Beaupère, G., Hecquet, J. & Marty, C. Pelvic incidence: A fundamental pelvic parameter for three-dimensional regulation of spinal sagittal curves. Eur. Spine J. 7, 99–103 (1998).

Le Huec, J. C., Thompson, W., Mohsinaly, Y., Barrey, C. & Faundez, A. Sagittal balance of the spine. Eur. Spine J. 28, 1889–1905 (2019).

Maillot, C., Ferrero, E., Fort, D., Heyberger, C. & Le Huec, J. C. Reproducibility and repeatability of a new computerized software for sagittal spinopelvic and scoliosis curvature radiologic measurements: Keops®. Eur. Spine J. 24, 1574–1581 (2015).

Vialle, R. et al. Radiographic analysis of the sagittal alignment and balance of the spine in asymptomatic subjects. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Ser. A 87, 260–267 (2005).

Stagnara, P. et al. Reciprocal angulation of vertebral bodies in a sagittal plane: approach to references for the evaluation of kyphosis and lordosis. Spine 7, 335–342 (1982).

Barrey, C., Jund, J., Noseda, O. & Roussouly, P. Sagittal balance of the pelvis-spine complex and lumbar degenerative diseases. A comparative study about 85 cases. Eur. Spine J. 16, 1459–1467 (2007).

Rodda, J. & Graham, H. K. Classification of gait patterns in spastic hemiplegia and spastic diplegia: A basis for a management algorithm. Eur. J. Neurol. 8, 98–108 (2001).

Deceuninck, J. et al. Sagittal X-ray parameters in walking or ambulating children with cerebral palsy. Ann. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 56, 123–133 (2013).

Cornec, G. et al. Determinants of satisfaction with motor rehabilitation in people with cerebral palsy: A national survey in France (ESPaCe). Ann. Phys. Rehabil. Med. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rehab.2019.09.002 (2019).

Britz, E., Langerak, N. G. & Lamberts, R. P. A narrative review on spinal deformities in people with cerebral palsy: Measurement, norm values, incidence, risk factors and treatment. South African Med. J. 110, 767 (2020).

Langerak, N. G. et al. Incidence of spinal abnormalities in patients with spastic diplegia 17 to 26 years after selective dorsal rhizotomy. Child’s Nerv. Syst. 25, 1593–1603 (2009).

Rosenberg, N. J., Bargar, W. L. & Friedman, B. The incidence of spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis in nonambulatory patients. Spine 6, 35–38 (1981).

Bernard, J. C. et al. Motor function levels and pelvic parameters in walking or ambulating children with cerebral palsy. Ann. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 57, 409–421 (2014).

Chaléat-Valayer, E., Bernard, J.-C., Deceuninck, J. & Roussouly, P. Pelvic-spinal analysis and the impact of onabotulinum toxin a injections on spinal balance in one child with cerebral palsy. Child Neurol. Open. https://doi.org/10.1177/2329048X16679075 (2016).

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by the Association de Recherche des Massues who had no involvement in any part of the research or publication process. We thank Johanna Robertson, PT, PhD for writing assistance.

Funding

The authors did not receive support from any organization for the submitted work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ECV, CV and SV contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by all the authors. The first draft of the manuscript was written by ECV and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Consent statement

Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee of Catholic University of Lille (Université Catholique de Lille) on 19 December 2019 (No. CIER-2019-44). Due to the retrospective nature of the study, the Ethics Committee of the Catholic University of Lille waived the need for obtaining informed consent.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chaléat-Valayer, E., Vernez, C., Verdun, S. et al. Classification of spinopelvic balance in ambulatory adolescents and adults with cerebral palsy: a cross-sectional study. Sci Rep 15, 19903 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03762-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03762-6