Abstract

The gut dysbiosis has been observed in gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM). However, changes in bacterial population are different among various countries due to genetic, environmental, and dietary differences. We compared the gut dominant phylum and some genus in GDM versus normo-glycemic pregnant in Iranian population, considering dietary intake. In this case-control study, 50 women diagnosed with GDM and 50 healthy pregnant, aged 18–35 yrs, during spring and summer, were participated. GDM was diagnosed based on the International Association of Diabetes and Pregnancy Groups criteria. The bacterial populations were determined based on 16SrRNA gene expression. Actinomycetota (p = 0.02), and Bifidobacterium spp. (p = 0.001) was significantly higher in the gut of healthy mothers than the GDM. However, bacteroides was significantly higher in the gut of GDM mothers than the healthies (p = 0.02). Daily calorie intake showed a negative correlation with population of Bacteroidota (p = 0.04) and Actinomycetota (p = 0.009), but dietary carbohydrate and fat showed a positive correlation. Increase in dietary intake of mono- and poly-unsaturated fatty acids (MUFAs and PUFAs) was associated with higher Bacteroidota in the gut (p = 0.02 and p = 0.04). However, dietary cholesterol showed a negative correlation with population of Bacteroidota and Bifidobacterium spp. (p = 0.003 and p = 0.02). GDM was correlated with the gut dysbiosis. Daily calorie and cholesterol intake was positively associated with dysbiosis. However total intake of carbohydrates, MUFAs and PUFAs showed a protective effect.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM), as a complex metabolic disorder, occurs during the second half of pregnancy, with an alarming increase throughout the world1. Due to the maternal and fetal side effects, this disorder is considered one of the most important problems during pregnancy2. Recently, the role of gut dysbiosis has been suggested in pathogenesis of GDM3. The gut-liver axis plays a major role in the pathophysiologic and therapeutic aspects of metabolic diseases. Role of the gut in hormone production involved in macronutrient metabolism makes this organ more prominent to study about novel diagnostic or prognostic markers4. The gut microbiota can use undigested carbohydrates, especially fibers, and produce short-chain fatty acids (SFCAs) which play key roles in human metabolism. Previously, it is reported that SFCA improves insulin sensitivity and dyslipidemia, prevents weight gain, and increases energy expenditure in diet-induced obesity5. The human gut bacteria are classified into phyla, classes, orders, families, genera, and species6. The dominant gut microbial phyla are Firmicutes, Bacteroidota, Actinomycetota, and Proteobacteria which include more than 95% of the gut bacterial population which varies in a person at different stages of life in response to the lifestyle, environmental, and clinical conditions7,8. Increasing evidence proposed the critical role of gut microbiota on glucose homeostasis and insulin resistance9. The underlying mechanisms are related to the low-grade endotoxemia that lead to destruction of the gut barrier, imbalance in the production of SCFAs, and disruption in bile acid metabolism9,10,11,12. Our recent cohort study on Iranian population showed that a higher Bacteroidota and Actinomycetota population in the gut of mothers at the first trimester of pregnancy was associated with lower risk of GDM in the screening time. Higher Firmicutes to Bacteroidota ratio in the gut of mothers was associated with fasting and 1-h glucose intolerance13. Dietary composition, especially daily intake of calorie and macronutrients, directly effect on the gut population of bacteria14 which justify the various results have been shown in previous studies due to the differences in eating habits. Herein, we assessed the dominant gut phylum in mothers with GDM at 24–28 weeks of pregnancy compared to the normo-glycemic mothers, considering anthropometric measures, and dietary intake in Zanjan city, as a mountainous area in Iran.

Materials and methods

The present study ethically approved by the ethic committee of Islamic Azad University, Zanjan Branch, under the code of IR.IAU.Z.REC.1401.067. All methods were performed in accordance with the Helsinki guidelines for human studies. Sampling was performed during spring and summer to omit the potential effects of seasonal alterations on the gut microbiota.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

In the present case-control study, one-hundred women aged 18–35 years, at 24–28 weeks of pregnancy, living in Zanjan city were participated. Cluster sampling was used based on the geographical distribution and with the aim to cover all areas of the city. Participants were included in the study after obtaining oral and written informed consent.

In case of unwillingness to participate in the study, consumption of probiotic, prebiotic, symbiotic and antibiotics at present or at least during the past two months, suffering from liver, kidney, heart, immune system, chronic gastrointestinal diseases, diabetes type 1 or 2, cancer, hypothyroidism, and malabsorptive disorders such as celiac disease, inflammatory bowel diseases were not included. Pregnant women with a previous history of GDM were excluded.

Pregnant women who were athlete were not included. All of the participants with mild physical activity up to 3 MET (milliliters of oxygen consumed per kilogram (kg) of body weight) per minute including sleeping, watching TV, writing, desk work, typing, walking up to 4 km/h were included.

Diagnosis of GDM

Based on the results of oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT), participants were categorized into the GDM or normal group. The diagnosis of GDM was made if there was at least one abnormal value (≥ 92, 180 and 153 mg/dl for fasting, one-hour and two-hour plasma glucose concentration respectively), after a 75 g dextrose15. In total, 50 women with GDM and 50 normo-glycemic healthy pregnant women were included.

Stool samples were gathered and immediately transferred to a −80 °C refrigerator for final analysis.

Demographic, dietary and anthropometric assessment

The demographic and anthropometric measures of the participants including education, age, height, pre-pregnancy weight, current weight at the time of sampling, and the number of delivery were recorded. Weight was measured using a calibrated scale (Seca, Germany), with minimal clothing and without shoes. Height was recorded using an inflexible meter (Seca, Germany), without shoes in a standing state, look forward. Then the body mass index (BMI) was calculated by dividing the weight (kilograms) by the square of the height (in meters). A validated food frequency questionnaire (FFQ)16 was completed for all participants who are validated by three-day food diary (two regular days, and one holiday).

DNA extraction and polymerase chain reaction

In the pre-treatment step, the samples were centrifuged at 8000 rpm for 5 min and the supernatant was gathered. Then, 100 µl of supernatant was mixed with 250 µl of phosphate- buffered saline (PBS). After adding 40 µl of proteinase K, the mixture was kept at 55 °C for 24 h. The suspension was kept at 95 °C for 15 min in a greenhouse to inactivate the proteinase K. Again, samples were centrifuged at 8000 rpm for 5 min, and DNA was extracted using the Roche kit (NBST, Iran), after supernatant depletion. At a sterile micro tube, 200 µl of PBS and 15 µl of lysozyme were added to the sediment, vortexed and incubated at 37 °C for 15 min. Then, 200 µl of tissue lysis buffer and 40 µl of proteinase K were added, vortexed immediately and kept in 70 °C for 15 min. Isopropanol (100 µl) was added, and micro tube was centrifuged at 8000 rpm for 1 min. The sediment liquid was removed after adding 500 µl of removal, washing buffer, and centrifuged at 8000 rpm for 1 min. Finally, an elution buffer was added and centrifuged at 8000 rpm for 1 min to extract DNA. DNA quality was examined by running a small amount on the agarose gel and concentration of the extracted DNA was determined by a Nanodrop 2000c spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, USA). The extracted DNA was kept in −20 °C refrigerator to final analysis. DNA amplification of 16SrRNA gene was done by quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) method using universal bacterial primers (Table 1). The reactions were performed using the SYBR green Master Mix High ROX (Amplicon, Denmark), in duplicated runs using positive (16SrRNA) and negative (purified water free of DNA and RNA) controls to increase the accuracy and reliability of the results. To prove the absence of DNA contamination, one well was considered as template for each reaction mixture which had no sample (NTC). The NTC without any product was considered as free of DNA contamination. Finally, the quantitative values were determined through the ABI StepOne sequence detection system (Applied Biosystems, California, USA).

Primers were designed based on the previous published articles. After preparation, their quality was checked. The desired length, Tm temperature, the percentages of GC base, and absence of any mutation in the designed primers were checked. Moreover, self-dimer, Homo-dimer and hairpin were checked in the primers. These primers were verified in the primer-BLAST database of the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI).

In each reaction, 20 µL micro tubes containing 10 µL of SYBR Green Master Mix, 4 µL of DNA template, and 0.5 µL of each forward and reverse primer were used. 5 µL purified water free of DNA and RNA was added. As described previously, a positive and negative control was used for each reaction.

The cycle threshold (CT) values were normalized against 16SrRNA as a positive control. The initial denaturation included one cycle: 95 °C for 10 min. The amplification profile included 40 three-step cycles including denaturation, annealing and extension steps: 95 °C for 30 s, 60 °C for 30 s and 72 °C for 30 s. The final extension was provided in one cycle: 72 °C for 30 s. The results were generated and analyzed using the 2^−∆∆Ct method in which ∆∆CT was computed as follows:

Sample size and statistical analysis

To determine differences between the gut Firmicutes to Bacteroidota ratio between mothers with GDM vs. healthy-one, the study of Chen et al.17, was used. Considering the power of 80% and 95% confidence level, fifty participants were counted. All samples were gathered in the spring and summer to omit the potential effects of seasonal alterations on the gut bacterial population. Dietary information was inserted to the N4 software (Nutritionist 4, USA). Dietary intake converted to grams per day and data transferred to SPSS software, version 18. The Kolmogorov Smirnoff test was used to assess the distribution form of data. In normal distributed data, an independent sample t-test was used to determine differences between the two groups. However, non-parametric tests were used for non-normal distributed data (quantitative values for phylum and species). Qualitative variables were compared by the chi2 square test. A mixed regression model was used to determine the effect of each parameter on the bacterial population.

Results

Demographic and baseline data of participants have been shown in Table 2. As shown, fasting, 1 h- and 2 h- plasma glucose were significantly higher in the GDM group (p < 0.001). GDM patients were older than the healthy mothers (p = 0.004). Moreover, pre-pregnancy BMI was significantly higher in the GDM than the healthy mothers (p = 0.005).

Dietary intake has been compared between the groups. As shown, there was no significant difference on daily calorie and macronutrient intake between the GDM and healthy groups (Table 3).

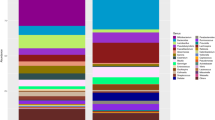

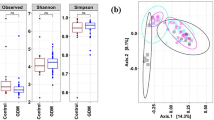

The gut dominant phyla have been compared between the two groups. As shown in Table 4, there was no significant difference about the population of Bacteroidota and Firmicutes between the two groups. However, the Actinomycetota population was significantly higher in the healthy mothers than the GDM (p = 0.02). In the species level, Bacteroides population were higher in the gut of GDM than the healthy group (p = 0.02). In addition, population of Bifidobacterium spp. were significantly higher in the gut of healthy mothers than the GDM (p = 0.001).

To determine the correlation between the baseline and dietary factors with the gut phyla and some species, a linear mixed regression model was used. Higher calorie intake was correlated with lower Bacteroidota population (OR= −7.3, p = 0.04). However higher carbohydrate intake was correlated with higher population of Bacteroidota in the gut (OR = 4.55, p = 0.004). Dietary fat intake showed a positive correlation with the Bacteroidota population (p = 0.03). Dietary MUFA and PUFA were correlated with 1.04- and 0.5-folds higher Bacteroidota population, respectively (p = 0.02 and p = 0.04). Dietary cholesterol showed a negative correlation with the Bacteroidota population (OR= −0.62, p = 0.003) (Table 5). None of the assessed parameters showed a significant correlation with the gut Firmicutes population (Table 6). Participant’s age and education showed a significant correlation with the Actinomycetota population (p = 0.01 and p = 0.02, respectively). Increase in daily calorie intake was correlated with lower Actinomycetota population in the gut (OR = 9.9, p = 0.009). Higher dietary carbohydrate intake was correlated with higher Actinomycetota population (OR = 5.9, p = 0.01). Dietary fat showed a significant positive correlation with Actinomycetota population in the gut (p = 0.001) (Table 7). Only, current weight showed a significant association with the Proteobacteria population (p = 0.04) (Table 8). The correlation of each parameter was assessed on some of species belonging to the assessed phyla. Serum 2 h-PG (OR = 0.42, 95%CI: 0.001, 0.06, p = 0.04), and maternal education (OR= −0.39, 95%CI: −2.3, −0.15, p = 0.02) showed a significant correlation with E.coli population. Moreover, dietary cholesterol showed a negative correlation with Bifidobacterium spp. population (OR=−0.5, 95%CI: −0.04, −0.003, p = 0.02). None of the assessed parameters showed any significant correlation with the population of Clostridium IV and Bacteroides in the gut.

Discussion

In the present study, a novel gut dysbiosis was observed in pregnant mothers with GDM in the second trimester versus healthy-one. At the phyla level, Actinomycetota population was significantly higher in the gut of healthy mothers than the GDM. At the genus level, Bacteroides was significantly higher in the gut of GDM mothers than the healthy-one. However, Bifidobacterium spp., as a beneficial gut flora was significantly lower in the gut of mothers with GDM compared with healthies. Daily calorie intake showed a negative correlation with the Bacterioidetes and Actinomycetota population, but dietary carbohydrate and fat sowed a positive effect on their habitat. Type of dietary oil showed an important effect on the population of Bacteroidota. Dietary MUFA and PUFA were correlated with higher Bacteroidota population. However, dietary cholesterol showed a negative correlation with the Bacteroidota and Bifidobacterium spp. population in the gut. Only, maternal current weight showed a significant correlation with the Proteobacteria population. Serum 2 h-PG and maternal education showed a significant correlation with E.coli population. Schematic overview of the present study has been shown in Fig. 1.

Pregnancy, as a complex physiological process, is accompanied by several alterations in metabolic pathways, hormonal production, immune system and microbiome to support the growth and development of fetus18. Maternal experiences including pre-pregnancy weight, gestational weight gain, pregnancy complications and metabolic abnormalities, diet, environmental exposures, stress, and drugs impact persistent modifications on fetal metabolism by epigenetic and the gut microbial alterations19,20,21,22. Some scholars have found that gestational age > 35 years is a risk factor for GDM23. Participants in the present study were under 35 years old. However, women with GDM were significantly older than the healthy mothers. In the adjusted models, age only showed a significant correlation with Actinomycetota population. Our results showed that older age is associated with the gut dysbiosis in term of lower Actinomycetota abundance, as the beneficial phyla. Recent evidence proposed that alterations in the maternal microbiome may play a role in the pathogenesis of GDM however the causal relationship is not clear24. During the first trimester, the dominant gut microbiome is gram- positive Firmicutes and gram-negative Bacteroidota, followed by Actinomycetota, Proteobacteria, Verrucomicrobia, Euryarchaeota and Faecalibacterium is similar to the healthy, non-pregnant women25. However, the composition and structure shifts over the periods of pregnancy26,27. Herein, some of the proposed mechanisms of glucose control by the gut microbes, compositionally and financially, are discussed. Chronic inflammation is a key feature of GDM which happens by modulating lipopolysaccharide–induced inflammatory responses through the gut microbes28. Chronic inflammation is associated with insulin resistance by destroying the intestinal barrier and increasing circulating endotoxin levels29. Diet can modulate the production of lipopolysaccharide-producing bacteria which in turn alter insulin sensitivity, systemic inflammation and immune responses30. Microbial metabolites, especially SCFAs, improve the cellular glucose metabolism. Amount of metabolites vary depending on the dietary intake of fiber and indigestible carbohydrates31. Bile acid metabolism is another effective pathway on blood glucose which is influenced by the gut bacterial population32. Bile acids can control a network of signaling pathways including glucose, lipid, steroid, xenobiotic metabolism as well as energy, through the activation of different bile acid receptors33. In previous studies comparing the microbiome profile of mothers with GDM vs. non-GDM women, decrease in Pseudomonadales, Dialister, Akkermansia, Roseburia, Bacteroides, Methanobrevibacter smithii, Eubacterium species, Alistipes species and beneficial bacteria, such as Bifidobacterium spp. and Lactobacillus have been reported33,34. Moreover, increase in the Firmicutes, Klebsiella variicola, Collinsella, Rothia, Ruminococcus, Actinomycetota, Parabacteroides distasonis, and Desulfovibrio populations have been observed in the GDM mothers compared to the normo-glycemic group33,35. Our results are opposite in term of the Actinomycetota and Bacteroides, but in accordance in term of Bifidobacterium spp. population with the previous studies. In the present study, the Firmicutes and Bacteroidota population showed no significant difference between the two groups. Dietary calorie and cholesterol intake showed negative effects on the gut bacterial population, but carbohydrates, MUFA and PUFA affected positively their community. Several human studies have suggested that a high-fat diet increases the counts of Bacteroides36,37. Investigation of the effects of different types of dietary fat on human gut flora, showed only the incremental effect of saturated fatty acids on Faecalibacterium prausnitzii population. No effect was observed for MUFA and PUFA on the gut bacterial genera36. Herein, dietary fat intake increased Bacteroidota population by 3.1-folds. Dietary MUFA and PUFA increased Bacteroidota population by 1.04- and 0.5-folds, respectively, but saturated fats showed no effect on none of the assessed phyla and genus. Dietary cholesterol decreased the Bacteroidota population in the gut by 38%. In animal model studies, the destructive effect of high fat diet was observed on the gut flora38,39. Source of dietary fat is the most important factor on the composition of the gut microbiome. One previous human study reported that dietary carbohydrate increased Bifidobacterium spp. population but decreased Bacteroides40. In our study, dietary carbohydrate showed a positive correlation with the Bacteroidota and Actinomycetota population, but no correlation was observed with Bifidobacterium spp. and Bacteroides. Differences among studies may be due to sample size, study design, and week of gestation in sampling time. Ethnicity and dietary habits are other various factors which effect on the gut microbiome in different studies. Confounding factors, including maternal pre-pregnancy BMI, weight gain during gestation, environmental factors, and antibiotic intake, influence the microbial composition of pregnant women and may account for the inconsistencies reported in the findings of previous studies. The present study had some limitations. Selection and recall bias are the most important of them. The small sample size and the cross-sectional design restrict the ability of the present study to draw causal conclusions. Moreover, the results of this study cannot be generalized to other regions of Iran because race, geographical environment, and food consumption can effect on the results. In addition, included women with diabetes diagnosed at 24–28 weeks of pregnancy, and individuals who may develop diabetes in the third trimester were not evaluated. We didn’t measure serum inflammatory markers to evaluate their association with the gut flora. Therefore, replicating of these studies in other countries is encouraged to validate the observed results, discover the underlying metabolic pathways, and assess its clinical application. Future studies on infants to evaluate association between maternal gut flora with the.

Data availability

Data will be available by the corresponding author based on request.

References

Dłuski, D. F. et al. Evolution of gestational diabetes mellitus across continents in 21st century. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 19 (23), 15804 (2022).

Kc, K., Shakya, S. & Zhang, H. Gestational diabetes mellitus and macrosomia: a literature review. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 66, 14–20 (2015).

Li, X. et al. The Intestinal Dysbiosis of Mothers with Gestational Diabetes Mellitus (GDM) and Its Impact on the Gut Microbiota of Their Newborns. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol. ; 2021: 3044534. (2021).

Crudele, L., Gadaleta, R. M., Cariello, M. & Moschetta, A. Gut microbiota in the pathogenesis and therapeutic approaches of diabetes. EBioMedicine 97, 104821 (2023).

Lu, Y. et al. Short chain fatty acids prevent high-fat-diet-induced obesity in mice by regulating g protein-coupled receptors and gut microbiota. Scientific Reports ; (2016). Article ID 37589.

Laterza, L., Rizzatti, G., Gaetani, E., Chiusolo, P. & Gasbarrini, A. The gut microbiota and immune system relationship in human graft-versus-host disease. Mediterr. J. Hematol. Infect. Dis. 8, e2016025 (2016).

Arumugam, M. et al. Enterotypes of the human gut Microbiome. Nature 473, 174–180 (2011).

Bai, J., Hu, Y. & Bruner, D. W. Composition of gut microbiota and its association with body mass index and lifestyle factors in a cohort of 7–18 years old children from the American gut project. Pediatr. Obes. 14 (4), e12480 (2018).

Palmnäs-Bédard, M. S. A. et al. The human gut microbiota and glucose metabolism: a scoping review of key bacteria and the potential role of SCFAs. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 116, 862–874 (2022).

Ye, D. et al. Integrative metagenomic and metabolomic analyses reveal gut microbiota-derived multiple hits connected to development of gestational diabetes mellitus in humans. Gut Microbes. 15, 1–17 (2023).

Bielka, W., Przezak, A. & Pawlik, A. The role of the gut microbiota in the pathogenesis of diabetes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23, 480 (2022).

Cai, J., Rimal, B., Jiang, C., Chiang, J. Y. & L, Patterson, A. D. Bile acid metabolism and signaling, the microbiota, and metabolic disease. Pharmacol. Ther. 237, 108238 (2022).

Mousavi, S. N. et al. Higher gut Bacteroidetes and Actinobacteria population in early pregnancy is associated with lower risk of gestational diabetes in the second trimester. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 25 (1), 106 (2025).

Haji-Ghazi Tehrani, L., Mousavi, S. N., Chiti, H. & Afshar, D. Effect of Atkins versus a low-fat diet on gut microbiota, and cardiometabolic markers in obese women following an energy-restricted diet: randomized, crossover trial. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 32 (7), 1734–1741 (2022).

Karagiannis, T., Bekiari, E., Manolopoulos, K., Paletas, K. & Tsapas, A. Gestational diabetes mellitus: why screen and how to diagnose. Hippokratia 14 (3), 151–154 (2010).

Mirmiran, P., Esfahani, F. H., Mehrabi, Y., Hedayati, M. & Azizi, F. Reliability and relative validity of an FFQ for nutrients in the Tehran lipid and glucose study. Public. Health Nutr. 13 (5), 654–662 (2010).

Chen, T. et al. Relationships between gut microbiota, plasma glucose and gestational diabetes mellitus. J. Diabetes Invest. 12 (4), 641–650 (2021).

Nuriel-Ohayon, M., Neuman, H. & Koren, O. Microbial changes during pregnancy, birth, and infancy. Front. Microbiol. 7, 1031 (2016).

Neri, C., Serafino, E., Morlando, M. & Familiari, A. Microbiome and gestational diabetes: interactions with pregnancy outcome and long-term infant health. J. Diabetes Res. 2021, 364 (2021).

Wang, J. et al. Dysbiosis of maternal and neonatal microbiota associated with gestational diabetes mellitus. Gut 67, 1614–1625 (2018).

Mousavi, S. N. et al. Extra Virgin Olive oil in maternal diet increases osteogenic genes expression, but high amounts have deleterious effects on bones in mice offspring at adolescence. Iran. J. Basic. Med. Sci. 19 (12), 1299–1307 (2016).

Zakaria, Z. Z. et al. Physiological changes and interactions between Microbiome and the host during pregnancy. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 12, 124 (2022).

Hiersch, L. et al. DOH-NET (Diabetes, obesity and hypertension in pregnancy research Network); SOON (Southern Ontario Obstetrical Network) Investigators. Gestational diabetes mellitus is associated with adverse outcomes in twin pregnancies. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 220, 102e1–102e8 (2019).

Dias, S., Pheiffer, C. & Adam, S. The maternal Microbiome and gestational diabetes mellitus: cause and effect. Microorganisms 11 (9), 2217 (2023).

Edwards, S. M., Cunningham, S. A., Dunlop, A. L. & Corwin, E. J. The maternal gut Microbiome during pregnancy. Am. J. Matern Child. Nurs. 42, 310–317 (2017).

Koren, O. et al. Host remodeling of the gut microbiome and metabolic changes during pregnancy. Cell. 150, 470–480 (2012).

Yang, H. et al. Systematic analysis of gut microbiota in pregnant women and its correlations with individual heterogeneity. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes 6, 32 (2020).

Pinto, Y. et al. Gestational diabetes is driven by microbiota-induced inflammation months before diagnosis. Gut 72, 918–928 (2023).

Hann, M. et al. Anti-inflammatory activity of isomaltodextrin in a C57BL/6NCrl mouse model with lipopolysaccharide-induced low-grade chronic inflammation. Nutrients 11, 2791 (2019).

Ferrarese, R., Ceresola, E. R., Preti, A. & Canducci, F. Probiotics, prebiotics and synbiotics for weight loss and metabolic syndrome in the Microbiome era. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 22, 7588–7605 (2018).

Cronin, P., Joyce, S. A., O’Toole, P. W. & O’Connor, E. M. Dietary fibre modulates the gut microbiota. Nutrients 13, 1655 (2021).

Kiriyama, Y. & Nochi, H. The biosynthesis, signaling, and neurological functions of bile acids. Biomolecules 9, 232 (2019).

Kuang, Y. S. et al. Connections between the human gut Microbiome and gestational diabetes mellitus. Gigascience 6, 1–12 (2017).

Collado, M. C., Isolauri, E., Laitinen, K. & Salminen, S. Distinct composition of gut microbiota during pregnancy in overweight and normal-weight women. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 88, 894–899 (2008).

Crusell, M. K. W. et al. Gestational diabetes is associated with change in the gut microbiota composition in third trimester of pregnancy and postpartum. Microbiome 6, 89 (2018).

Hasain, Z. et al. Gut microbiota and gestational diabetes mellitus: A review of host-gut microbiota interactions and their therapeutic potential. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 10, 188 (2020).

Fava, F. et al. The type and quantity of dietary fat and carbohydrate alter faecal Microbiome and short-chain fatty acid excretion in a metabolic syndrome at-risk population. Int. J. Obes. (Lond). 37, 216–223 (2013).

Wu, G. D. et al. Linking long-term dietary patterns with gut microbial enterotypes. Science 334, 105–108 (2011).

Lecomte, V. et al. Changes in gut microbiota in rats fed a high fat diet correlate with obesity-associated metabolic parameters. PLoS ONE. 10, e0126931 (2015).

Cani, P. D. et al. Changes in gut microbiota control metabolic endotoxemia-induced inflammation in high-fat diet-induced obesity and diabetes in mice. Diabetes 57, 1470–1481 (2008).

Acknowledgements

All authors are very thankful from pregnant women who were participated in the present study.

Funding

No funding received.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SN. M conceptualized and supervised the project, data analysis, and interpretation, and revise of the manuscript. R. Sha. conceptualized and supervised the project and contributed to data interpretation. R.S carried the project and the manuscript. S.H. and R. Sho advised the project and contributed to data interpretation and the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The present study ethically approved by the ethic committee of Zanjan Islamic Azad University under the code of IR.IAU.Z.REC.1401.067.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sohrabi, R., Mousavi, S.N., Shapouri, R. et al. The gut dysbiosis of mothers with gestational diabetes and its correlation with diet. Sci Rep 15, 18566 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03767-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03767-1