Abstract

As a population ages rapidly, fractures become a major contributor to hospital visits and increasing healthcare costs. However, the factors influencing healthcare costs among patients with and without fractures in Korea are not well understood. Our study aimed to identify the determinants of medical costs associated with fractures. We utilized the Korean National Health Insurance Service (NHIS)-Senior sample cohort database from 2002 to 2019. Patients with newly diagnosed fractures were classified as having hip fracture, vertebral fracture, non-vertebral non-hip fracture, and/or osteoporosis. We calculated the medical costs and the length of stay (LOS) for the period from 2010 to 2019 using NHIS claims data. Among 208,623 older adults, 78,096 (37.4%) had experienced fractures. Compared to their counterparts without fractures, these patients were predominantly female and older, were more commonly Medical Aid recipients, had lower income, were more likely to have obesity, engaged in less intense physical activity, and had more comorbidities. The mean medical costs for patients with fractures were USD $23,300, compared to $16,000 for those without fractures. Factors contributing to increased medical costs included fracture, male sex, older age, disability, Medical Aid enrollment, higher income, obesity, smoking, and comorbidities (chronic renal disease, arthritis, dementia, and higher Charlson Comorbidity Index). Substantial factors contributing to the rising medical costs and LOS include fracture, older age, Medical Aid enrollment, lower level of physical activity, and comorbidities. Management strategies are required to address these elements.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Fractures and falls are major health concerns for countries with aging populations, as these injuries lead to considerable morbidity and mortality as well as decreased quality of life1. As a population ages, musculoskeletal disorders, including fractures, become increasingly prevalent and costly to manage; these issues substantially impact patients and healthcare systems worldwide2,3,4. Data on the leading causes of disability-adjusted life years (DALYs), provided in the World Health Organization (WHO) Health Estimates 2019, indicate that falls were the 18th most common cause of death and accounted for 496 DALYs per 100,000 population (1.5%)5.

Fractures represent a major public health issue around the world due to the high risk of recurrence following an initial fracture. The incidence of fragility fractures appears to increase beginning in middle age, and a history of fracture is recognized as a risk factor that predisposes older adults to subsequent fracture6. Furthermore, the overall burden of these injuries is considerable.

Among Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development countries, Korea has the fastest rate of aging. In 2018, the nation became an “aged society,” with 14% of its population aged 65 years or older. By 2025, this demographic is projected to reach 20%, marking the transition to a “super-aged society.” In the foreseeable future, Korea is expected to become an ultra-aged society7. In 2022, when 18% of Korea’s population was over 65 years old, the cost of care for older adults constituted 43.1% of total medical expenses8. The leading causes of death are consistent between the general population and older adults—namely, cancer, heart disease, pneumonia, and cerebrovascular disease9. However, in 2022, 71% of patients admitted to emergency rooms for injuries resulting from falls were over 75 years old10. With the proportion of the population aged 65 or older anticipated to rise to 30% by 2035, the incidence of falls among older adults is expected to increase further.

Previous studies from various countries have examined the global burden of hip fracture11, sternal fracture12, and pelvic fracture13 as well as evaluating the costs of care for osteoporotic fracture14,15,16 and vertebral fracture17. A few studies have also investigated the factors associated with higher healthcare costs following hip fractures in the United States18 and the United Kingdom19,20.

However, minimal research has analyzed the determinants of healthcare costs for patients with fractures compared to those without such injuries in Korea. Thus, we examined the determinants of medical costs and the length of stay (LOS) associated with fractures among older adults.

Results

General characteristics

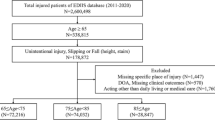

Our cohort included 349,280 individuals aged 65 years or older, of whom 140,657 were excluded due to rare diseases, cancer, and previous fractures. Among the remaining 208,623 older adults, 78,096 (37.4%) had experienced fractures (Fig. 1).

As shown in Table 1, of the patients with fractures, 66.8% were female, which was higher than the proportion among those without fractures (46.8%). The mean age of individuals with fractures was 70.9 years, which was older than that of their counterparts without fractures. The patients with fractures included higher proportions of Medical Aid recipients, members of the lowest income quintile, those who engaged in low physical activity, and those with obesity. Additionally, patients with fractures had higher rates of various medical conditions and high Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) which was score of 2 or above.

Average medical cost of fracture

As shown in Table 2, the average medical costs, LOS, and number of outpatient visits were all significantly higher for patients with fractures (p < 0.0001). The mean 1-year medical cost for patients with fractures was 23,300 ± 28,900 USD, approximately 1.5 times higher than that for those with no fractures ($16,000 ± $24,200). Similarly, the hospital LOS for the fracture group averaged 141.4 days, nearly double the average for the non-fracture group, which was 85.2 days. Additionally, those with fractures had an average of 29.8 outpatient visits, slightly higher than the 24 visits for the non-fracture group.

By fracture site, the greatest number of patients exhibited spinal fractures (n = 37,241), followed by compound fractures (n = 15,091). Regarding medical costs, compound fractures including hip fractures incurred the highest expenses, averaging 8,100 USD, with hip fractures alone following at 6,100 USD. Additionally, the LOS was longest for patients with compound fractures including hip fractures (61.8 days), followed by those with hip fractures alone (44.8 days), as detailed in Table 3.

Drivers of medical costs in patients with fractures

Table 4 summarizes the results of the multivariate regression analysis conducted to identify variables influencing medical costs and LOS. After adjusting for patient characteristics, fractures were found to significantly increase the medical cost per patient (β estimate = $6,300) and the LOS (β estimate = 44.2 days). Other variables associated with higher medical costs included male sex, older age, having a disability, enrollment in Medical Aid, higher income, obesity, smoking, and comorbidities such as chronic renal disease, arthritis, dementia, and a higher CCI. Regarding LOS, covariates linked to an increase in admitted days included female sex, older age, having a disability, receiving Medical Aid, low income, low level of exercise, smoking, and comorbidities such as diabetes mellitus, gastrointestinal disease, arthritis, dementia, and a higher CCI.

In case of hip fractures, after adjusting for patient characteristics, hip fractures were found to significantly increase the medical cost per patient (β estimate = $15,700) and the LOS (β estimate = 170 days).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the medical costs associated with fractures in Korea by considering healthcare utilization through NHI data and individual behavioral factors using data from NHI examinations.

Several studies have reported that fractures contribute to increased medical costs. A systematic review revealed that the estimated costs incurred during the first year after a hip fracture exceed those associated with acute coronary syndrome and ischemic stroke21. While hip fractures appear comparable to cardiovascular diseases in terms of hospitalization, the additional social costs associated with new comorbidities, sarcopenia, diminished quality of life, disability, and mortality are likely higher. A systematic review of the costs of fragility hip fractures estimated that the mean total health and social care costs in the first year following a hip fracture were $43,669 per patient21. Consistent with other research, our study found that fractures significantly increased the medical cost per patient as well as the LOS.

A previous study indicated that factors such as poor mobility, obesity, and the presence of multiple comorbidities are associated with higher total healthcare costs following hip fractures in the United States18. Similarly, research has shown that in the United Kingdom, older patients and those residing in more deprived areas incur higher healthcare costs over the 2 years following a hip fracture19,20. In our study, patient characteristics—male sex, older age, enrollment in Medical Aid, higher income level, and disability—along with clinical factors such as obesity, smoking, and comorbidities (including chronic renal disease, arthritis, dementia, and a higher CCI) were associated with higher costs. Notably, the results regarding age and comorbidities align with findings from previous research.

This study illustrated the number of patients and medical costs according to types of fractures. The number of spinal fractures was 16,674 among 78,069 fracture patients in Korea, while spinal fractures were difficult to detect22. However, this value is consistent with the report of the Korean Society for Bone and Mineral Research (KSBMR)23.

Also, 1-year cost for hip fractures was $6,100 (regression β estimate=$15,700) in our study, whereas $33,975 in the U.S24. Due to the economic level and the difference in the healthcare payment system, fracture costs were non-comparable to the previous study, the study of Korea reported a smaller cost of care. However, it is similar in that the health care costs for hip fractures were higher than fractures of other sites.

Korea’s aging population is anticipated to grow rapidly, which will likely lead to an increase in the number of patients with fractures. This study is meaningful as it analyzed factors contributing to the total healthcare costs and LOS for these patients, as well as the management of medical expenses due to fracture.

The Korean government is facing the risk of insufficient insurance finances due to the rapid aging of the population25, and the need for measures to improve the efficiency of medical expenses is increasing. Korea’s health insurance policy prioritizes reducing the medical expenses of patients suffering from serious diseases such as cancer or rare diseases. Moreover, the benefit schemes of National Health Insurance have focused on treatment rather than prevention or rehabilitation.

This study found that the impact of hip fractures (estimate=$15,700) increased medical costs was greater than that of overall fractures (estimate=$6,300) even after adjusting for other factors. The number of patients with hip joint disease is expected to increase due to aging. In the context of sustainability, it will be necessary to emphasize the significance of exercise, management of obesity, and no smoking. To reduce medical costs, a practical policy will be needed that preventive measures including osteoporosis screening or fall prevention programs and enhancing post-fracture rehabilitation programs.

The study has several strengths. First, we utilized the large-population National Health Insurance claims data to achieve generalizable results. Second, the present study is representative of the entire population of older adults in Korea.

Our study does have certain limitations. While we attempted to adjust for confounding variables that were measurable within the claims database, the internal validity was limited due to the exclusion of unmeasurable variables such as bone density. Additionally, our use of administrative NHI claims data means that the costs of healthcare services not covered by the NHI may not have been included. According to the fracture types, the spectrum of LOS and healthcare costs vary depending on the duration of rehabilitation or the number of complex surgical interventions.

Second, we used the health behavior variables using self-reported values in the national health examination, and thereby there might be errors. In Korea, National Health Insurance covers the overall population, and the national health examination is conducted every two years. Although we used the most recent values to reduce the bias, the intended reporting error might happen.

Third, although inflation might happen over 10 years, we didn’t adjust the inflation rate in calculating overall medical costs across this period. Payment for medical services of the National Health Insurance (NHI) in Korea is the pay-for-service system, and the NHI Service (NHIS) announces the resource-based value score every year. The unit price per score of hospitals and the consumer price increased by an average of 1.8% and 1.7% over 10 years, respectively. However, in this study, the main goal is to compare relative differences in medical expenses between groups with fractures and without fractures, and we compared the medical costs without adjusting for the inflation rate.

In conclusion, as the number of patients with fractures is expected to increase, the prevention and management of medical costs associated with fractures will be crucial in shaping healthcare policies for public health and the sustainability of National Health Insurance finances.

Methods

Data source

In this study, we used the Korean National Health Insurance Service (NHIS)-Senior Sample Cohort database, spanning from 2002 to 2019. This database covered an 8% random sample of the 6,400,000 insured individuals aged 60–80 years in 2008, along with additional randomly sampled older adults from 2009 onwards (total n = 1,057,784). The NHIS-Senior Sample Cohort consists of five databases, which include: (1) information on beneficiaries’ health insurance eligibility, (2) medical utilization in hospitals (treatment), (3) characteristics of the hospitals, (4) medical examinations, and (5) long-term care utilization.

The health insurance eligibility information includes general characteristics of the beneficiary, including age, sex, region, type of health insurance, health insurance premium tier, degree of disability, and death.

The database on medical utilization covers all in-hospital and outpatient visits, thus capturing a range of data that include demographic characteristics, diagnoses, health care utilization (tests, procedures, days of treatment, and expenditures), and medication usage (product name, active ingredient, dose, days of therapy, and drug cost)26. South Korea operates a single-payer National Health Insurance (NHI) system, which ensures coverage for all citizens (51.8 million) and reimburses health care providers on a fee-for-service basis.

Health examinations are categorized into two types: general health and life-transition health examinations. General health examinations include assessments of blood pressure, blood tests for parameters including fasting glucose levels and cholesterol, urine tests, chest X-ray examinations, obesity evaluations, electrocardiograms, assessments of drinking frequency, smoking behavior, and dental screenings. Life-transition health examinations in Korea involve hepatitis B antigen testing and mental health evaluations for individuals at the age of 40 years, as well as bone density tests, physical function tests, and assessments regarding cognitive dysfunction for those 66 years old.

Study population

Among 1,057,784 individuals aged 60–80 years in the cohort database from January 2010 to December 2019—the study population was limited to 349,280 adults who were over 65 years old in 2010.

Patients newly diagnosed with fractures were identified using the following diagnosis codes from the International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision: hip fracture (S72.0, S72.1, S72.2, and S32.4); vertebral fracture (S12, S22, and S32, excluding S32.3-5); non-vertebral non-hip fracture (S22.3-5, S32.3, S32.5, S42.2, S42.4, S52.0-1, S52.3, S52.5-6, S72.3-4, S72.7, S72.9, S82.0-1, and S92.0); and osteoporosis with pathological fracture (M80), between January 2010 and December 2019. To identify new patients, we excluded those with incident fractures from 2002 to 2009. Additionally, we excluded patients with cancer or rare diseases such as Parkinson’s disease which might affect medical costs and length of stay (LOS)27.

During the study period, we compared patients with fractures to those without such injuries.

Outcome measures

The outcome measures were 1-year medical costs and LOS of hospitalization during the study period. Medical costs were determined by calculating the annual medical expenses incurred by the beneficiaries for NHI services. LOS was assessed based on the patient’s date of admission and date of discharge. The medical costs variable had a non-negative nature and heteroskedasticity, in that the variance increases with the mean medical cost. We analyzed these variables by log-transformation and it satisfies normality.

Other covariates

Age was treated as a continuous variable, with the inclusion of an age-squared term. Healthcare coverage was categorized into two groups: NHI enrollees and recipients of Medical Aid, a subsidy program for individuals with low income. Income level was categorized into 10 groups. Disability status was classified as none, moderate, or severe. Overweight was defined as a body mass index over 25.0 kg/m2, while abdominal obesity was indicated by a waist circumference exceeding 85 cm for women and 90 cm for men, in accordance with the criteria set by the Korean Society for the Study of Obesity. The CCI was calculated using primary diagnosis codes from healthcare utilization records to assess the level of comorbidities, with categories of 0, 1, 2, or 3 or more, following the methodology established by Charlson et al.28.

Also, we selected comorbidities using the previous study24. We used comorbidities such as hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes mellitus, cardiac disease, stroke, renal disease, liver disease, lung disease, arthritis, and dementia based on the primary diagnosis code or secondary diagnosis code.

Health behavior were assessed using a self-reported questionnaire. Initially, participants were asked about their history of stroke, heart disease, and hypertension, as well as any family history of diabetes. Subsequently, data on alcohol consumption over the past year, as well as smoking history, were gathered. Regarding physical activity levels, participants were classified into three categories: high (those who engaged in both vigorous and moderate physical activities), medium (those who engaged only in vigorous activities and those who engaged only in moderate activities at least once a week), and low (those who did not engage in either). Vigorous physical activities included running, aerobic exercise, and high-speed bicycling, while moderate activities were exemplified by power walking, playing tennis doubles, and bicycling at a normal speed.

Statistical analysis

The medical costs were analyzed based on the presence or absence of fracture, as well as the fracture site. Descriptive statistical analyses were performed, employing the t-test or chi-square test for comparisons regarding fracture.

Multivariable linear regression models were used to investigate potential differences in (i) total medical costs and (ii) all-cause hospitalization LOS. The results are presented as unstandardized regression coefficients (β) accompanied by p-values. As LOS and medical costs are continuous variables, normality was presumed based on the central limit theorem.

Outcome variables were continuous variables such as medical costs and LOS. We treated these outcome variables by log-transformation and it satisfied the normality of residual. There is some multicollinearity between independent variables as VIF is less than 2, however, we selected the explanatory variables in the model according to previous studies.A two-tailed p-value of less than 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance. SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) was used for the analysis.

The Institutional Review Board of Kongju National University approved the study protocol and waived the requirement for informed consent (reference No. KNU_IRB_2023-24). We confirm that all methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Data availability

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Schene, M. R. et al. Imminent fall risk after fracture. Age Ageing. 52 (10). https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afad201 (2023). Epub 2023/11/06.

Court-Brown, C. M., Clement, N. D., Duckworth, A. D., Biant, L. C. & McQueen, M. M. The changing epidemiology of fall-related fractures in adults. Injury 48 (4), 819–824. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.injury.2017.02.021 (2017). Epub 2017/03/12.

Court-Brown, C. M. & McQueen, M. M. Global forum: Fractures in the elderly. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Am. 98(9), e36. Epub 2016/05/06 (2016). https://doi.org/10.2106/JBJS.15.00793.

Aging and Health [Internet]. (2022). Ahttps://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ageing-and-health

WHO. WHO Methods and Data Sources for Global Burden of Disease Estimates 2000–2015 (WHO, 2017).

Holmberg, A. H. et al. Risk factors for fragility fracture in middle age. A prospective population-based study of 33,000 men and women. Osteoporosis Int. 17(7), 1065-77. Epub 2006/06/08 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-006-0137-7.

Statistics, K. N. Senior Citizen Statistics Data in 2022 (Korea National Statistics Office, 2022).

(HIRA) HIRAS, (NHIS) NHIS. National Health Insurance Statistical Yearbook. Wonju: Annual.

Korea Statistics. Cause of Death Statistics. (Korea Statistics, 2022).

KCDA. Injury Factbook 2023 Published [Internet] (Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency, 2023).

Zhang, Z. X., Xie, L. & Li, Z. Global, regional, and National burdens of facial fractures: a systematic analysis of the global burden of disease 2019. BMC Oral Health. 24 (1), 282. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-024-04048-5 (2024). Epub 2024/02/29.

Proctor, D. W. et al. Trends in the incidence of rib and sternal fractures: A nationwide study of the global burden of disease database, 1990–2019. Injury 55 (4), 111404. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.injury.2024.111404 (2024). Epub 2024/02/15.

Hu, S., Guo, J., Zhu, B., Dong, Y. & Li, F. Epidemiology and burden of pelvic fractures: results from the global burden of disease study 2019. Injury 54 (2), 589–597. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.injury.2022.12.007 (2023). Epub 2022/12/18.

Han, S., Kim, S., Yeh, E. J. & Suh, H. S. Understanding the long-term impact of incident osteoporotic fractures on healthcare utilization and costs in Korean postmenopausal women. Osteoporosis Int. 35(2), 339–352. Epub 2023/10/25 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-023-06934-0.

Wu, J., Qu, Y., Wang, K. & Chen, Y. Healthcare resource utilization and direct medical costs for patients with osteoporotic fractures in China. Value Health Region. Issues 18, 106– 111. Epub 2019/03/26. 10.1016/j.vhri.2018.11.008 (2019).

Taguchi, Y., Inoue, Y., Kido, T. & Arai, N. Treatment costs and cost drivers among osteoporotic fracture patients in Japan: a retrospective database analysis. Archives Osteoporos. 13 (1), 45. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11657-018-0456-2 (2018). Epub 2018/04/27.

Zheng, X. Q. et al. Incidence and cost of vertebral fracture in urban China: A 5-year population-based cohort study. Int. J. Surg. 109(7), 1910-8. Epub 2023/05/03. 10.1097/JS9.0000000000000411.

Schousboe, J. T. et al. Pre-fracture individual characteristics associated with high total health care costs after hip fracture. Osteoporosis Int. 28(3), 889–899. Epub 2016/10/16. (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-016-3803-4.

Soong, C. et al. Impact of an integrated hip fracture inpatient program on length of stay and costs. J. Orthop. Trauma. 30 (12), 647–652. https://doi.org/10.1097/BOT.0000000000000691 (2016). Epub 2016/11/23.

Glynn, J., Hollingworth, W., Bhimjiyani, A., Ben-Shlomo, Y. & Gregson, C. L. How does deprivation influence secondary care costs after hip fracture? Osteoporosis Int. 31(8):1573–1585. Epub 2020/04/03 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-020-05404-1.

Williamson, S. et al. Costs of fragility hip fractures globally: A systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Osteoporosis Int. 28(10), 2791–2800. Epub 2017/07/28 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-017-4153-6.

Zhang, Y., Tang, W., Niu, Y., Zhou, X. & Lin, F. Osteoporotic thoracic vertebral compression fracture: an easily overlooked fracture. World Neurosurg. 192, 242–243. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2024.09.092 (2024). Epub 2024/10/13.

KSBMR. Osteoporosis Fact Sheet. The Korean Society for Bone and Mineral Research (2023).

Williams, S. A. et al. Economic burden of Osteoporosis-Related fractures in the US medicare population. Annals Pharmacotherapy. 55 (7), 821–829. https://doi.org/10.1177/1060028020970518 (2021). Epub 2020/11/06.

OECD Health Statistics [Internet]. OECD Publishing. https://stats.oecd.org/index.aspx?DataSetCode=HEALTH_STAT. Accessed 15 Dec 2023.

Park, D., Lee, H. & Kim, D. S. High-cost users of prescription drugs: National Health Insurance Data from South Korea. J. Gen. Intern. Med. Epub 2021/10/28. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-021-07165-x (2021).

Chae, J., Cho, H. J., Yoon, S. H. & Kim, D. S. The association between continuous polypharmacy and hospitalization, emergency department visits, and death in older adults: a nationwide large cohort study. Front. Pharmacol. 15, 1382990. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2024.1382990 (2024). Epub 2024/08/15.

Charlson, M. E., Pompei, P., Ales, K. L. & MacKenzie, C. R. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J. Chronic Dis. 40 (5), 373–383 (1987).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a research grant from Kongju National University in 2023 (2023-0336-01).

Funding

This work was supported by a research grant from Kongju National University in 2023 (2023-0336-01).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

DSK designed the study and wrote the main article. KC and DSK revised the written article. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Institutional Review Board of Kongju National University approved the study protocol and waived the requirement for informed consent.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chae, K., Kim, DS. Determinants of medical costs in patients with and without fractures using Korean Senior Cohort Study. Sci Rep 15, 21691 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03951-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03951-3