Abstract

This study investigated the relationship between serum Alpha-Klotho (α-Klotho) levels and bone mineral density (BMD) in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) using data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2011–2016. A population of 781 CKD patients aged ≥ 40 years was analyzed using multiple linear regression models to examine the association between serum α-Klotho levels and BMD at different skeletal sites, with adjustments for demographic, lifestyle, and clinical factors. Results showed that serum α-Klotho levels were significantly correlated with BMD at thoracic spine (β = 0.004 g/cm2, p = 0.00264), total BMD (β = 0.003 g/cm2, p = 0.02591), and trunk BMD (β = 0.002 g/cm2, p = 0.03708), while no significant associations were observed at the left leg, lumbar spine, or pelvis. Stratified analyses showed that the association was more pronounced in men, non-Hispanic whites, those with a body mass index greater than 29.9 kg/m2, and those without hypertension and diabetes. The inconsistent associations observed across different skeletal sites suggest that it remains unclear whether serum α-Klotho levels are consistently associated with BMD in CKD patients. Additionally, the cross-sectional design precludes any determination of causality in the observed site-specific associations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

CKD has increasingly become a critical global public health issue. Recent epidemiological investigations reveal a global landscape of CKD, with approximately 18.99 million new cases and an estimated 697.29 million prevalent cases reported in 20191. An estimated 14.0% of American adults currently experience CKD2. More alarmingly, over 90% of individuals with CKD are unaware of their condition3. The maintenance of BMD is regulated by various factors, and its disruption in CKD patients is well documented4. CKD mineral and bone disorder (CKD-MBD) is a common and serious complication in CKD patients, characterized by a progressive increase in fracture and disability risks concurrent with renal function deterioration5. CKD-MBD significantly compromises patient well-being and prognosis, while demonstrating a profound correlation with increased cardiovascular and all-cause mortality risks6. Therefore, a comprehensive investigation of the relationship between CKD and BMD holds substantial clinical significance.

The klotho protein, originally identified for its anti-aging characteristics, also functions as a significant regulator of mineral metabolism, with its primary expression localized in the kidney7. As a critical co-receptor for fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF23), the protein significantly maintains calcium and phosphorus metabolic equilibrium7,8. While traditional CKD-MBD markers such as FGF23 and PTH have been extensively studied and incorporated into clinical practice, α-Klotho deserves particular focus for several distinct reasons. First, unlike FGF23 and PTH which primarily serve as downstream indicators of disturbed mineral metabolism, α-Klotho functions as a fundamental regulator at the crossroads of mineral homeostasis and bone metabolism pathways9. Second, while the relationship between elevated FGF23/PTH and bone abnormalities is relatively well-characterized, the independent role of α-Klotho in bone health remains considerably underexplored despite its critical position as an FGF23 co-receptor10. Third, preliminary evidence suggests α-Klotho possesses direct bone-protective properties through mechanisms separate from its FGF23-related functions, including inhibition of osteoclastogenesis and promotion of osteoblast differentiation11. These unique properties become particularly relevant in the context of CKD, where significant alterations in α-Klotho expression occur.

Serum klotho levels demonstrate markedly reduced concentrations among CKD patients, with those in CKD stages 3–4 exhibiting approximately 30–50% lower serum klotho levels than healthy controls12. Existing literature presents conflicting evidence concerning the clinical relationship between klotho protein and BMD, with some studies suggesting a potential positive correlation. Research by Zheng et al.13 showed a substantial correlation linking klotho levels with BMD in maintenance hemodialysis patients. Investigating end-stage renal disease (ESRD) patients across middle and advanced age groups, Huang et al.14 further confirmed a positive correlation between klotho protein concentrations and BMD, suggesting that high Klotho levels may act as a protective factor. However, Marchelek-Mysliwiec15 reported no significant association between klotho protein and BMD in chronic renal failure patients. In a study by Lee16, α-Klotho was found to have no correlation with BMD in chronic hemodialysis patients. More controversially, some research indicates that klotho levels may be negatively correlated with BMD. For example, research encompassing 59 renal transplant patients demonstrated an inverse correlation between α-Klotho protein and lumbar spine BMD17. These controversial findings indicate the critical need for comprehensive exploration of the klotho-BMD relationship across more expansive and more diverse population cohorts.

This study analyzed the relationship between α-Klotho and BMD in patients aged 40 years and older, utilizing data from three cycles of the NHANES (https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/) conducted between 2011 and 2016. Based on the available evidence, we hypothesized that serum α-Klotho levels are positively associated with BMD in patients with CKD, with varying effects across different population subgroups. The study focused on examining the association between α-Klotho and BMD in various body regions among patients with CKD. Through stratified analyses by gender, age, ethnicity, BMI, and the presence of chronic diseases, we evaluated the potential of serum α-Klotho as a predictive indicator for bone loss and osteoporosis in patients with CKD.

Methods and materials

Study population

This study utilized data from the 2011–2016 cycle of the NHANES, a national program led by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to assess the health and nutritional status of the U.S. population. Comprehensive health indicators are collected through questionnaires, physical examinations, and laboratory tests, providing nationally representative data on demographic characteristics, biochemical parameters, and physical examinations. Over the three survey cycles, we excluded 22,041 individuals lacking α-Klotho measurements, 4,186 individuals with incomplete BMD data, and 2,894 individuals without CKD from the initial 29,902 participants, resulting in a final analytic sample of 781 participants (Fig. 1).

Participant Selection Flowchart for the Study Cohort. This study began with 29,902 participants from the NAHANSE 2011–2016 survey and sequentially excluded participants who did not meet the participants who did not meet the inclusion criteria. CKD was defined using KDIGO guideline criteria and calculated by the CKD-EPI formula.

Independent variable and dependent variables

In this study, serum α-Klotho was designated as the independent variable. Samples were measured by the University of Washington Northwest Lipid Metabolism and Diabetes Research Laboratory using ELISA kits. Data analysis incorporated the averaged results from repeated sampling. The dependent variables included left leg BMD, trunk bone BMD, thoracic spine BMD, lumbar spine BMD, pelvic BMD, and total BMD. BMD data were measured using a dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) scanner (Hologic Discovery DEXA Scanner, Hologic, Inc., Bedford, MA, USA) and scans were analyzed using APEX 4.1.

Collection of covariates

We collected and integrated various demographic and clinical characteristics of the participants. Continuous variables included age, BMI, ALP, AST, ALT, total serum calcium, creatinine, albumin, blood phosphorus, blood urea nitrogen, glomerular filtration rate (GFR), dietary vitamin D2 + D3, dietary calcium and 25(OH)vitamin D; categorical variables included gender, race, income poverty ratio, alcohol use, education level, smoking status, physical activity and comorbid diabetes and hypertension.

Of these, Income levels were categorized based on family poverty ratio: low income (< 1.3), middle income (1.3–3.5), and high income (≥ 3.5). Smoking status was categorized as: non-smokers (less than 100 lifetime cigarettes), ex-smokers (≥ 100 lifetime cigarettes, currently non-smokers), and current smokers (≥ 100 lifetime cigarettes, currently smokers). Alcohol ues was classified as none (lifetime consumption of < 12 drinks), moderate (1 drink per day for women, 1–2 drinks per day for men), and heavy (≥ 2 drinks per day for women, ≥ 3 drinks per day for men). Physical activity was converted to metabolic equivalent (MET) minutes per week of moderate to vigorous exercise18. According to the Physical Activity Guidelines for Adults19, participants were classified as meeting recommendations (≥ 600 MET-minutes/week, equivalent to 150 min/week of moderate-intensity or 75 min/week of vigorous-intensity physical activity) or not meeting recommendations (< 600 MET-minutes/week). Dietary vitamin D and calcium intake were assessed using two 24-hour dietary recalls: one in-person and one by telephone 3–10 days later. Intake values were calculated by averaging both recalls or using only the first when second recalls were missing. Data were collected using the automated multiple pass method and structured interviews. Presence of hypertension and diabetes was determined through self-reported physician diagnoses obtained during structured interviews.

Diagnosis of CKD

CKD was diagnosed based on either (1) a GFR < 60 ml/min/1.73 m2 (G3a-G5), or (2) a GFR ≥ 60 ml/min/1.73 m2 (including both G1 and G2 stages) in conjunction with an elevated urinary albumin-to-creatinine ratio (ACR) > 30 mg/g (A2 or A3)20. GFR was estimated using the CKD-EPI (Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration) formula that combines serum creatinine, race, and gender21. Serum creatinine was measured using the IDMS-calibrated Jaffe rate method according to the NHANES protocol. Because of the cross-sectional design of NHANES, the diagnosis of CKD was based on a single measurement of serum creatinine and ACR rather than multiple measurements over a three-month period, as clinically recommended, which is consistent with previous epidemiologic studies utilizing NHANES data for CKD research.

Statistical methods

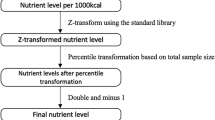

To enhance the representativeness of the NHANES data, we employed sample weights to account for its complex multistage sampling design in all analyses. These weights adjust for unequal selection probabilities, non-response bias, and post-stratification to match sample demographic characteristics with the U.S. general population, thereby ensuring results reflect the target population characteristics rather than merely the sample distribution. Specifically, we utilized the Mobile Examination Center (MEC) weights provided by NHANES, adjusted for the pooled six-year period (2011–2016) by dividing the weights by 3. For descriptive statistics, study subjects were stratified into quartiles based on α-Klotho protein levels. Continuous variables were reported as mean ± standard deviation, whereas categorical variables were expressed as percentages. Multiple linear regression models were subsequently utilized to analyze the association between serum α-Klotho levels and BMD. For clinical interpretation, serum α-Klotho levels underwent a linear transformation (divided by 100), expressed as α-Klotho/100 (pg/mL), where regression coefficients represent changes in BMD per 100 pg/mL increment in serum α-Klotho. Three progressive adjustment models were developed for the study: Model I, an unadjusted model; Model II, adjusted for basic demographic characteristics including race, age, and gender; Model III, a fully adjusted model that included all covariate adjustments from Table 1. In addition, stratified analyses based on race, gender, age, BMI, and comorbid diabetes and hypertension were performed to assess the relationship of serum α-Klotho levels with BMD in CKD patients across different populations. All statistical analyses were conducted using Empower Stats (version 4.2) and R software (version 4.2.0) with the “survey” package (version 4.1.1) to properly incorporate the complex survey design elements, with significance levels indicated by *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01.

Results

Basic characteristics of the study population

The demographic and clinical characteristics of the study population were stratified and presented in Table 1 according to serum α-klotho (pg/ml) protein quartiles: Q1 (289.20-667.70), Q2 (667.80-811.40), Q3 (811.50-1012.50), and Q4 (1016.90–2453.00). Among all participants, there were more females (72.72%) than males (27.28%), and the mean age was 50.40 ± 5.57 years. The racial distribution was predominantly white African-Hispanic (67.64%). However, gender, age, and racial distribution were not statistically different between quartiles of alpha-klotho levels (p > 0.05).

Significant associations were mainly in metabolic and renal function indices. As α-klotho levels increased from the lowest quartile (Q1) to the highest quartile (Q4), BMI values showed a significant decreasing trend (p < 0.001) from 32.81 ± 7.99 kg/m2 in Q1 to 30.11 ± 7.39 kg/m2 in Q4. Renal function-related indices also demonstrated significant associations, with serum creatinine levels decreasing significantly (p < 0.001) with increasing α-klotho levels, from 82.20 ± 55.43 umol/L in Q1 to 68.35 ± 25.71 umol/L in Q4; similarly, uric acid levels showed a significant decreasing trend (p < 0.001) from 336.06 in Q1 ± 85.56 umol/L to 289.05 ± 82.82 umol/L in Q4.Blood urea nitrogen likewise showed a trend of negative correlation (p = 0.006) with α-klotho level from 5.13 ± 2.33 mmol/L in Q1 to 4.57 ± 1.67 mmol/L in Q4.

In contrast, ALP activity increased significantly (p = 0.001) with increasing α-klotho levels, from 68.03 ± 23.13 IU/L in Q1 to 75.45 ± 29.72 IU/L in Q4.AST levels showed a similar increasing trend (p = 0.025), from 25.95 ± 10.99 U/L in Q1 to 31.09 ± 29.51 U/L in Q4.

Regarding lifestyle factors, α-klotho level showed a significant association with smoking status (p_trend = 0.013), with 60.71% of non-smokers in the highest α-klotho level group (Q4), compared to only 49.24% in the lowest group (Q1). Alcohol intake pattern also differed significantly among the groups (p = 0.0043), with a higher proportion of heavy drinkers (Q2:58.53%, Q3:46.65%) in the intermediate quartile groups (Q2-Q3) compared to a lower proportion (39.25%) in the highest quartile group (Q4).

The prevalence of diabetes mellitus differed significantly between groups with different alpha-klotho levels (p = 0.0054), but did not show a clear linear trend, with the lowest prevalence in Q3 (3.10%) and the highest in Q2 (12.65%). The proportion of income poverty was also statistically different between the groups (p = 0.0357), particularly in the changes in the distribution of the middle-income and high-income groups.

Correlation of serum α-klotho with BMD

Table 2 evaluates the association between serum α-Klotho levels and BMD. serum α-klotho levels demonstrated significant positive associations with BMD at multiple skeletal sites in the fully adjusted model (Model III). Each 100 pg/mL increment in serum α-Klotho was associated with increases of 0.004 g/cm2 (95% CI: 0.002, 0.007; p = 0.00264) in thoracic spine BMD, 0.002 g/cm2 (95% CI: 0.000, 0.005; p = 0.03708) in trunk BMD, and 0.003 g/cm2 (95% CI: 0.000, 0.005; p = 0.02591) in total BMD. Quartile analysis further confirmed these associations, with the strongest relationship observed in the thoracic spine: compared to the lowest quartile, the Q2, Q3, and Q4 quartiles showed progressively higher BMD values (Q2: β = 0.028 g/cm2, 95% CI: 0.006, 0.050; Q3: β = 0.036 g/cm2, 95% CI: 0.013, 0.059; Q4: β = 0.048 g/cm2, 95% CI: 0.024, 0.071; p for trend = 0.0001). Similar linear associations were observed for trunk and total BMD (Q4 vs. Q1: trunk β = 0.025 g/cm2, p = 0.01224; total BMD β = 0.029 g/cm2, p = 0.00845), with significant linear trends (p for trend = 0.02110 and 0.01561, respectively). It is important to note that no significant associations were found between serum α-Klotho levels and BMD at the left leg (β = 0.001, p = 0.29042), lumbar spine (β = 0.001, p = 0.41913), or pelvis (β = 0.002, p = 0.27368) in the Model III. As illustrated in Fig. 2, the multivariate-adjusted smoothed curve-fit analysis reflects the relationship between serum α-Klotho and BMD at each anatomic site. Although some of the curves were not visually correlated enough, the statistical analysis did support the existence of significant positive correlations at multiple anatomical sites, particularly thoracic spine, trunk, and total BMD.

Correlation of serum α-klotho/100 levels with site-specific BMD. Analyzing linear and nonlinear relationships between α-Klotho and BMD using generalized additive models. The solid red line represents the smooth curve fit between variables. Blue bands represent the 95% confidence interval of the fit. Race, gender, age, education, income poverty ratio, alcohol, smoking, ALP, AST, ALT, total calcium, creatinine, globulin, phosphorus, hypertension, BMI, HGB, PLT, Hba1c, physical activity, dietary vitamin D, dietary calcium and 25(OH)vitamin D were adjusted.

Stratified analysis

Table 3 presents stratified analyses by age, gender, race, BMI, and comorbidities (diabetes and hypertension) to evaluate the associations between serum α-Klotho and BMD across different CKD patient subgroups. Gender-specific analyses revealed stronger associations in males, particularly for thoracic spine BMD (β = 0.009 g/cm2, 95% CI: 0.003, 0.015; P = 0.0016), compared to females (β = 0.004 g/cm2, 95% CI: 0.000, 0.007; P = 0.028), although the interaction was not significant (p for interaction = 0.0821). Age-stratified (≤ 50 vs. > 50 years) analyses showed that this association was not significantly different between age groups (P > 0.05 for all interactions). Younger patients (≤ 50 years) showed statistically significant positive associations in thoracic spine and trunk BMD. Among racial groups, Non-Hispanic Whites demonstrated the most consistent positive associations across multiple skeletal sites, with a significant race interaction observed for total BMD (p for interaction = 0.0380). BMI-stratified analyses showed significant associations exclusively in obese individuals (BMI > 29.9) for thoracic spine BMD (β = 0.005 g/cm2, 95% CI: 0.001, 0.010; P = 0.0187). Similarly, in diabetes-stratified analyses, significant associations were found only in non-diabetic individuals for thoracic spine BMD (β = 0.004 g/cm2, 95% CI: 0.001, 0.007; P = 0.0074), while diabetic patients showed no significant associations.

Notably, hypertension status significantly modified the relationship between α-Klotho and BMD, particularly in thoracic spine and pelvis (P for interaction = 0.0177 and 0.0386, respectively). The positive association was more pronounced in non-hypertensive individuals (thoracic spine: β = 0.005 g/cm2, P = 0.0029) compared to those with hypertension (β=-0.002 g/cm2, P = 0.5469).

Subgroup analysis by CKD pathophysiology

We further divided CKD patients into two subgroups according to pathophysiologic mechanisms: the group with decreased renal function (GFR < 60 ml/min/1.73 m2) and the group with preserved renal function but proteinuria (GFR ≥ 60 ml/min/1.73 m2 + ACR > 30 mg/g), in order to investigate the α-Klotho-BMD relationship in different CKD subtypes. Distinct patterns of association were observed in these two subgroups: in the group with decreased renal function, α-Klotho showed a positive correlation with BMD at multiple sites, whereas in the group with preserved renal function but proteinuria, a trend toward a negative correlation was observed. Detailed results of the subgroup analyses are shown in Tables S2 and S3 of the Supplementary Material.

These findings represent associations observed in a cross-sectional analysis and do not imply causality.

Discussion

Main associations and potential threshold values

In this study, we investigated the association between serum α-Klotho levels and BMD at multiple anatomical sites using data from 781 patients with CKD from the NHANES database from 2011 to 2016. Through a comprehensive multivariate adjusted analysis, we found significant positive correlations between serum α-Klotho levels and BMD at specific skeletal sites, with the most pronounced correlation in the thoracic spine region (β = 0.004 g/cm2, p = 0.00264), and a significant positive correlation between serum α-Klotho levels and BMD at total BMD (β = 0.003 g/cm2, p = 0.02591) and trunk BMD (β = 0.002 g/cm2, p = 0.03708), and this association is more extensive and stronger in specific populations (such as males, non-Hispanic whites, obese patients, and those without hypertension and diabetes).

These findings align with and extend previous research in this field. Based on our quartile analysis, we can also propose potential reference values of serum α-Klotho for bone health in CKD patients. Our quartile analysis showed a significant association between serum α-Klotho levels and BMD in patients with CKD. The observed dose-response relationship permits two interpretations: The transition points between quartiles, particularly between Q2-Q3 (360–480 pg/mL) (non-transformed values, pg/mL), could serve as hypothetical reference values. The significant improvement in BMD observed from Q2 onwards suggests that the lower limit of Q3 may represent a level beneficial for bone health. Concurrently, the significant positive correlation of α-Klotho as a continuous variable with BMD indicates a potential “higher is better” pattern, rather than a specific threshold. The biological mechanisms underlying the observed association between α-Klotho and BMD are supported by several lines of evidence.

Differential effects based on CKD pathomechanism

Although these associations represent the overall findings, the relationship between α-Klotho and BMD showed significant differences when CKD patients were categorized into the group with decreased renal function and the group with normal renal function but proteinuria. In the group with decreased renal function (GFR < 60 ml/min/1.73 m2), high α-Klotho levels were associated with thoracic spine (Q2: β = 0.045, p = 0.00231; Q3: β = 0.040, p = 0.00653), pelvis (Q2: β = 0.059, p = 0.00264) and trunk BMD (Q2: β = 0.040, p = 0.00164) were significantly positively correlated. However, in the group with preserved renal function but concomitant proteinuria (GFR ≥ 60 ml/min/1.73 m2 + ACR > 30 mg/g), high α-Klotho levels showed a negative correlation with lumbar spine (Q2-Q4: β=-0.051 to -0.067, p < 0.05) and pelvic BMD (Q3: β=-0.054, p = 0.03283).

It should be noted that the association of α-Klotho with lumbar spine BMD should be interpreted with caution. Lumbar spine DXA measurements are susceptible to degenerative changes, vascular calcification, and osteoarthritis, which are common in CKD patients, and may lead to measurement artifacts that artificially elevate BMD values. In addition, CKD-associated alterations in bone metabolism affect the lumbar spine, which is dominated by cancellous bone, differently from other sites, which are dominated by cortical bone, which may explain the site-specific variability in the results we observed.

This contrasting phenomenon suggests that the role of α-Klotho in bone metabolism may vary depending on the pathomechanism of CKD. In patients with decreased renal function, α-Klotho may exert osteoprotective effects by regulating mineral metabolism and PTH signaling pathway; whereas, in patients with proteinuria, systemic inflammation and oxidative stress may alter the physiological function of α-Klotho, leading to negative correlation with BMD, while proteinuria may promote α-Klotho urinary loss and affect its bioavailability.

These findings elucidate the complex relationship between α-Klotho and bone metabolism in patients with chronic renal failure, provide possible explanations for inconsistent results in previous studies, and underscore the need for individualized bone health strategies based on chronic renal failure subtypes.

Comparison of the literature and its underlying molecular mechanisms

Our findings are consistent with some of the previous reports in the literature, and there are also discrepancies, which need to be understood by comparing a wide range of related studies. Zheng et al. conducted a cross-sectional study involving 125 patients on maintenance hemodialysis, demonstrating significant positive correlations between serum klotho protein levels and BMD at the lumbar spine and femoral neck. Multivariate linear regression analysis indicated that serum klotho represents a primary determinant of BMD13. Similarly, among 87 patients with end-stage renal disease, serum klotho demonstrated a positive relationship with BMD in a clinical study14. Cailleaux et al.22 in a 4.3-year longitudinal study, found that bone loss in nondialysis CKD patients occurred predominantly in the proximal radius, providing a temporal dimension to our observation of regional BMD associated with α-Klotho. In addition, Silva et al.23 showed that α-Klotho was not only associated with bone mineral metabolism but also strongly correlated with cardiovascular risk in nondialysis CKD patients, suggesting that the overall cardiovascular status of the patient needs to be taken into account when assessing the relationship between α-Klotho and BMD. Recently, Fan et al.24 confirmed a significant correlation between low levels of soluble Klotho and increased risk of CKD-MBD in CKD patients, further supporting our findings.

The basic mechanism by which klotho affects BMD involves binding to the fibroblast growth factor receptor (FGFR), resulting in the formation of a high-affinity receptor that targets FGF23. FGF23 is an endocrine signaling protein originating from osteocytes and osteoblasts, primarily responsible for regulating serum 1,25-(OH)2D and phosphate levels, thereby maintaining phosphate homeostasis25. Additionally, FGF23 can suppress osteoclast activity and promote osteoblastogenesis. Klotho serves as a co-receptor for FGF23, forming the Klotho/FGF23 axis and significantly increasing the affinity of FGF23 with FGFR, thereby regulating calcium-phosphate metabolism and decelerating bone mass loss26,27,28. Soluble klotho, distributed across blood, urine, and cerebrospinal fluid, demonstrates β-glucuronidase functionality and modulates diverse cellular receptors and ion transport proteins, playing a critical role in protecting renal and skeletal functions29,30,31. Klotho shows high sensitivity to both chronic and acute renal damage, with its levels notably declining early in kidney disease patients and CKD experimental models32,33. This reduction limits the regulatory effects on FGF-23, consequently making hyperphosphatemia a primary factor in FGF-23 secretion. The elevated FGF-23 expression indirectly induces and exacerbates hypocalcemia, subsequently increasing parathyroid hormone (PTH) levels. The combined action of PTH and FGF-23 enhances bone resorption, ultimately leading to osteoporosis34,35.

Experimental studies have revealed that klotho protein expression deficiency is a key factor in kidney injury and significant BMD reduction in CKD mouse models36. When the Klotho gene is knocked out in mice, abnormalities in osteoblast differentiation to osteocytes are observed. However, mature osteoclasts retain their resorptive activity, resulting in pathological osteoporotic changes. This suggests that Klotho protein simultaneously participates in bone metabolism regulation37. Consequently, the decreased expression of klotho protein emerges as a crucial factor driving the pathogenesis of osteoporosis within CKD38.

Although our study provides clinical evidence for the relationship between α-Klotho and BMD in patients with CKD, it is critical to understand the relationship between these findings and the mechanisms revealed in animal studies. Our observation of a positive correlation between α-Klotho and BMD in human CKD patients may reflect the fact that the role of Klotho in the regulation of bone metabolism revealed in animal experiments has a similar mechanism in humans. However, it is important to recognize that there are significant species-specific differences between rodent models and human bone metabolism, including the influence of the bone remodeling cycle, the complexity of hormonal regulatory networks, and clinical factors. This makes the direct causal relationships observed in animal studies potentially more complex to manifest in humans.

However, some studies have reported different findings. A cross-sectional study demonstrated that klotho and fibroblast FGF-23 were associated with bone trabecular scores in the initial stages of CKD, but not with BMD39. Additionally, among individuals experiencing chronic renal failure, klotho protein has no relationship with lumbar spine and femoral neck BMD15. Within a Canadian stratified case-cohort investigation, linear analysis demonstrated no significant correlation between α-Klotho and BMD during the intermediate phases of CKD40. In contrast to Ribeiro’s research revealing an inverse U-shaped pattern linking α-Klotho levels and fracture incidence41, Chalhoub’s investigation within the Healthy ABC cohort found no association between klotho, BMD, and fracture risk in an elderly population aged 70–79 years42. These discrepancies might originate from fundamental differences in population characteristics, sample size, and methods of klotho detection43. It is worth emphasizing that this study primarily included non-dialysis CKD patients with relatively preserved renal function. In contrast, end-stage CKD patients and those receiving dialysis treatment exhibit more complex pathophysiological states, including severe imbalance of the PTH-vitamin D-FGF23 axis44, significant metabolic disturbances, exacerbated oxidative stress responses45, decreased erythropoietin secretion, and various effects from the dialysis treatment itself. These additional pathological factors may interfere with and complicate the intrinsic association between α-Klotho and BMD. The relative absence of these confounding factors in our study population may be one reason we were able to observe a more consistent positive correlation between serum α-Klotho and BMD, particularly in the thoracic spine region.

Subgroup analyses

Adhering to the methodological guidelines of the STROBE statement46, this study systematically identified subgroups within the population that exhibited differential trends by stratifying the analysis. The findings showed that α-Klotho was significantly and positively associated with thoracic spine, trunk bone, and total BMD in non-Hispanic whites, which is consistent with previous studies’ findings regarding the positive association of klotho gene polymorphisms with BMD in white and Japanese menopausal women47. Significant differences in vitamin D metabolism between races have been demonstrated, and non-Hispanic whites have specific differences in genetic polymorphisms of vitamin D-binding proteins compared with other races, which affect vitamin D bioavailability and thus regulate α-Klotho mediated calcium metabolism and bone formation processes, possibly explaining the race-specific associations we observed48.

Our study found that the association between α-Klotho and BMD was stronger in males than in females. This gender difference may originate from the differential regulation of α-Klotho expression by androgens. Zhang et al.49 demonstrated that in U.S. males aged 40–79 years, total testosterone was significantly positively correlated with serum α-klotho levels, and this association remained robust after adjusting for multiple confounding factors. Testosterone may enhance FGF23 signaling pathway sensitivity and optimize calcium-phosphorus balance by upregulating α-Klotho expression, thus exhibiting a stronger correlation with BMD in males.

After adjusting for BMI, we observed a significant positive correlation exclusively in the obese population with a BMI ≥ 29.9 kg/m2. This BMI threshold effect can be explained from two perspectives50: from a biomechanical standpoint, the increased mechanical load in obese individuals directly stimulates bone tissue remodeling; from a molecular mechanism perspective, inflammatory factors secreted by adipose tissue in obesity may activate the anti-inflammatory regulatory pathway of α-Klotho, thereby influencing bone metabolism. This is consistent with previous research showing that BMD positively correlates with BMI52, with α-Klotho potentially serving as a key regulatory factor in this relationship, especially in high BMI states53.

After stratification by comorbidities, we found that in non-hypertensive individuals, α-Klotho shows significant positive correlations with thoracic spine BMD and trunk bone BMD, while in hypertensive patients, these correlations disappear, with interaction analyses showing statistical significance in the thoracic spine and pelvis regions. This phenomenon reflects the complex changes in the relationship between α-Klotho and bone metabolism under hypertensive conditions. Abnormal Klotho protein expression and function are closely associated with various adverse cardiovascular outcomes, including inflammatory processes, arterial calcification, and endothelial dysfunction54. Persistent inflammation in hypertensive patients produces TNF-α that can directly damage Klotho protein, while increased ROS from oxidative stress not only interferes with Klotho activity but also disrupts the bone microenvironment55. Furthermore, elevated angiotensin II due to hypertension inhibits Klotho expression56, while metabolic disorders and FGF23-Klotho axis imbalance work together to mask or even reverse the potential physiological relationship between α-Klotho and BMD.

In diabetes stratification analysis, we found that the positive correlation between α-Klotho and BMD was significant only in thoracic spine of non-diabetic patients (β = 0.004 g/cm2, p = 0.007), with no association observed in diabetic patients. The mechanism may involve hyperglycemia directly inhibiting bone formation and promoting bone resorption, insulin resistance interfering with FGF23/FGFR signaling pathway, inflammatory cytokines disrupting bone metabolic balance, and microvascular complications affecting bone blood supply and calcium-phosphorus metabolism, collectively weakening the positive correlation between α-Klotho and BMD57,58.

Clinical implications of personalized BMD management

Our findings suggest several important clinical applications. First, we observed that patients with α-Klotho levels above certain ranges (360–480 pg/mL) showed higher BMD values, as patients above this range showed significantly higher BMD values, which may be useful in identifying patients with CKD who require closer monitoring. Second, our analyses showed stronger correlations in specific subgroups (men, non-Hispanic whites, patients with a BMI greater than 29.9 kg/m2, and patients without hypertension/diabetes), providing an opportunity for a more targeted management approach. In addition, we found different associations based on the pathophysiologic mechanisms of CKD (decreased renal function versus preserved renal function with proteinuria), which underscores the need for mechanism-specific strategies rather than a generalized approach. Finally, the strongest associations were seen at the thoracic spine site, suggesting the particular value of monitoring this site for the early detection of bone changes that may respond to α-Klotho pathway interventions. Collectively, these findings highlight the potential utility of α-Klotho as a biomarker for bone health in CKD patients, though longitudinal studies are needed to fully establish its predictive value for osteoporosis risk.

Strengths and limitations

When interpreting our findings, several methodological strengths and limitations should be considered. This study possesses several notable strengths: Firstly, it leveraged the large-scale NHANES 2011–2016 database, encompassing 781 patients with CKD and comprehensively assessed changes in BMD at multiple anatomical sites. This large sample improves the representativeness of the results compared to previous studies. Secondly, a multilevel multivariate adjustment model was employed to control for confounding factors, including demographic characteristics, socioeconomic factors, and biochemical indicators, which bolsters the internal validity of the findings. Thirdly, the heterogeneity of the association between klotho protein and BMD among CKD populations was elucidated through stratified analyses of subgroups defined by age, gender, and race. This provides valuable molecular epidemiological evidence for the development of personalized medicine. Finally, through statistical processing, such as logarithmic transformation, the study effectively reduced data distribution bias and enhanced the accuracy of the analysis.

At the same time, the research presents several limitations. Firstly, the study population was limited to CKD patients aged ≥ 40 years, as NHANES measured serum α-Klotho levels only in participants in this age group. This limitation may affect the generalizability of the study results to younger patients, as younger CKD patients (< 40 years of age) often have different etiologies (e.g., congenital disorders, primary glomerulonephritis) and bone metabolic characteristics. Future studies specifically targeting younger CKD patients would be valuable to determine whether the associations we observed extend to the entire age range of CKD. Secondly, as a cross-sectional observational design, it could only reveal associations between α-Klotho and BMD, yet precluded establishing conclusive causal determination. Despite controlling for multiple confounding factors through multivariate modeling, the possibility of residual confounding cannot be completely eliminated. For example, we were unable to isolate vitamin D supplementation and bone resorption inhibitors as confounders because of the large amount of missing data and the insufficient number of users in the study population. The NHANES database is limited by the design of cross-sectional measurements at a single time point, and therefore it is not possible to track the dynamic relationship between α-Klotho levels, BMD, and dynamic changes in α-Klotho and various metabolic parameters, including mineral metabolism. In addition, our study population consisted mainly of patients with CKD stage 2 or early stage 3, in which certain metabolic disturbances may not yet be clearly manifested because the compensatory mechanisms of renal function are still relatively well-established. These complex physiologic regulatory mechanisms may need to be fully elucidated by a longitudinal study design. Despite the large sample size, the statistical power for certain subgroups after stratified analysis may be inadequate, and larger prospective studies are needed for further validation in the future. Additionally, CKD classification was based on a single measurement of eGFR and albuminuria, which may misclassify transient reductions in kidney function as CKD. This limitation is inherent to the cross-sectional design of NHANES and should be considered when interpreting our findings.

Conclusions and future directions

In conclusion, this study found that serum α-Klotho levels were significantly associated with BMD at thoracic spine, total body, and trunk sites in CKD patients, but not at lumbar spine, pelvis, or legs. The inconsistent associations across different skeletal sites suggest that it remains unclear whether serum α-Klotho levels are associated with BMD in CKD patients, as no correlation was observed at three out of the six sites measured. This highlights the complexity of bone metabolism in CKD and the need for further research to elucidate these site-specific differences. However, the cross-sectional design further limits causality inferences. Future efforts should focus on validating these site-specific associations in larger cohorts with diverse CKD stages. Subsequently, longitudinal and interventional studies could further explore the potential relationship between α-Klotho and bone metabolism, as well as the biological mechanisms underlying any site-specific effects. Elucidation of these mechanistic pathways is prerequisite to establishing the clinical significance of α-Klotho in skeletal homeostasis among CKD patients.

Data availability

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. These data can be found here: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/.

References

Dong, B. et al. Epidemiological analysis of chronic kidney disease from 1990 to 2019 and predictions to 2030 by Bayesian age-period-cohort analysis. Ren. Fail. ;46(2):2403645. doi: 10.1080/0886022X.2024.2403645. (2024). Epub 2024 Sep 19.

Johnson, H. N. & Prasad-Reddy, L. Updates in chronic kidney disease. J. Pharm. Pract. 37 (6), 1380–1390. https://doi.org/10.1177/08971900241262381 (2024). Epub 2024 Jun 14.

Florea, A. et al. Chronic kidney disease unawareness and determinants using 1999–2014 National health and nutrition examination survey data. J. Public. Health (Oxf). 44 (3), 532–540. https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdab112 (2022).

Lloret, M. J. et al. Evaluating osteoporosis in chronic kidney disease: Both bone quantity and quality matter. J. Clin. Med. 13 (4), 1010. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13041010 (2024).

Hsu, C. Y., Chen, L. R. & Chen, K. H. Osteoporosis in patients with chronic kidney diseases: A systemic review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21 (18), 6846. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21186846 (2020).

Rroji, M., Figurek, A. & Spasovski, G. Should we consider the cardiovascular system while evaluating CKD-MBD? Toxins (Basel). 12 (3), 140. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins12030140 (2020).

Prud’homme, G. J. & Wang, Q. Anti-Inflammatory role of the Klotho protein and relevance to aging. Cells 13 (17), 1413. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells13171413 (2024).

Sun, F., Liang, P., Wang, B. & Liu, W. The fibroblast growth factor-Klotho axis at molecular level. Open. Life Sci. 18 (1), 20220655. https://doi.org/10.1515/biol-2022-0655 (2023).

Chen, G. et al. α-Klotho is a non-enzymatic molecular scaffold for FGF23 hormone signalling. Nature 553 (7689), 461–466 (2018).

Komaba, H. et al. Klotho expression in osteocytes regulates bone metabolism and controls bone formation. Kidney Int. 92 (3), 599–611 (2017).

Fan, Y. et al. Klotho in Osx+-mesenchymal progenitors exerts pro-osteogenic and anti-inflammatory effects during bone remodeling and repair. Signal. Transduct. Target. Ther. 7 (1), 167 (2022).

Kim, H. R. et al. Circulating α-klotho levels in CKD and relationship to progression. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 61 (6), 899–909. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.ajkd.2013.01.024 (2013). Epub 2013 Mar 27.

Zheng, S. et al. Correlation of serum levels of fibroblast growth factor 23 and Klotho protein levels with bone mineral density in maintenance Hemodialysis patients. Eur. J. Med. Res. 23 (1), 18. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40001-018-0315-z (2018).

Huang, T. et al. The relationship between serum fibroblast growth factor 23 and Klotho protein and low bone mineral density in Middle-Aged and elderly patients with End-Stage renal disease. Horm. Metab. Res. 56 (2), 142–149. https://doi.org/10.1055/a-2168-5089 (2024).

Marchelek-Mysliwiec, M. et al. Association between plasma concentration of Klotho protein, osteocalcin, leptin, adiponectin, and bone mineral density in patients with chronic kidney disease. Horm. Metab. Res. 50 (11), 816–821. https://doi.org/10.1055/a-0752-4615 (2018). Epub 2018 Nov 5.

Lee, W. T. et al. Serum intact fibroblast growth factor 23 levels are negatively associated with bone mineral density in chronic Hemodialysis patients. J. Clin. Med. 12 (4), 1550. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12041550 (2023).

Matei, A. et al. Body composition, adipokines, FGF23-Klotho and bone in kidney transplantation: is there a link? J. Nephrol. 35 (1), 293–304. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40620-021-00972-9 (2022). Epub 2021 Feb 9.

World Health Organization Global Physical Activity Questionnaire (GPAQ). Analysis Guide. [(accessed on 11 October 2021)]; Available online: https://www.who.int/ncds/surveillance/steps/resources/GPAQ_Analysis_Guide.pdf

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans. [(accessed on 19 October 2021)];Available online: https://health.gov/paguidelines/guidelines/chapter5.aspx

Chen, T. K., Knicely, D. H. & Grams, M. E. Chronic kidney disease diagnosis and management: A review. JAMA 322 (13), 1294–1304. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2019.14745 (2019).

Levey, A. S. et al. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med. ;150(9):604 – 12. (2009). https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-150-9-200905050-00006. Erratum in: Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(6):408.

Cailleaux, P. E. & NephroTest study group et al. Longitudinal bone loss occurs at the radius in CKD. Kidney Int. Rep. 6 (6), 1525–1536. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ekir.2021.03.874 (2021).

Silva, A. P. et al. Plasmatic Klotho and FGF23 levels as biomarkers of CKD-Associated cardiac disease in type 2 diabetic patients. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20 (7), 1536. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms20071536 (2019).

Fan, Z. et al. Correlation between soluble Klotho and chronic kidney disease-mineral and bone disorder in chronic kidney disease: a meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 14 (1), 4477. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-54812-4 (2024).

Simic, P. & Babitt, J. L. Regulation of FGF23: Beyond bone. Curr. Osteoporos. Rep. 19 (6), 563–573 (2021).

Milovanova, L. Y. et al. Low serum Klotho level as a predictor of calcification of the heart and blood vessels in patients with CKD stages 2-5D. Ter. Arkh. 92 (6), 37–45 (2020). Russian.

Kuro-o, M. Klotho and the aging process. Korean J. Intern. Med. 26 (2), 113 (2011).

Navarro-García, J. A. et al. PTH, vitamin D, and the FGF-23-klotho axis and heart:going beyond the confines of nephrology. Eur. J. Clin. Invest. 2018, 48(4).https://doi.org/10.1111/eci.12902

Dërmaku-Sopjani, M. et al. Downregulation of NaPi-IIa and NaPi-IIb Na-coupled phosphate transporters by coexpression of Klotho. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 28 (2), 251–258. https://doi.org/10.1159/000331737 (2011). Epub 2011 Aug 16.

Xu, Y. & Sun, Z. Molecular basis of Klotho: From gene to function in aging. Endocr. Rev. 36 (2), 174–193. https://doi.org/10.1210/er.2013-1079 (2015). Epub 2015 Feb 19.

Doi, S. et al. Klotho inhibits transforming growth factor-beta1 (TGF-beta1) signaling and suppresses renal fibrosis and cancer metastasis in mice. J Biol Chem. ;286(10):8655–8665. (2011). https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M110.174037. Epub 2011 Jan 5.

Koh, N. et al. Severely reduced production of Klotho in human chronic renal failure kidney. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 280 (4), 1015–1020. https://doi.org/10.1006/bbrc.2000.4226 (2001).

Sakan, H. et al. Reduced renal α-Klotho expression in CKD patients and its effect on renal phosphate handling and vitamin D metabolism. PLoS One. 9 (1), e86301. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0086301 (2014).

Hruska, K. A., Sugatani, T., Agapova, O. & Fang, Y. The chronic kidney disease - Mineral bone disorder (CKD-MBD): advances in pathophysiology. Bone 100, 80–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bone.2017.01.023 (2017). Epub 2017 Jan 22.

Cejka, D. et al. Sclerostin and Dickkopf-1 in renal osteodystrophy. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 6 (4), 877–882. https://doi.org/10.2215/CJN.06550810 (2011). Epub 2010 Dec 16.

Lin, W. et al. Klotho preservation via histone deacetylase Inhibition attenuates chronic kidney disease-associated bone injury in mice. Sci. Rep. 7, 46195. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep46195 (2017).

Yuan, Q. et al. Deletion of PTH rescues skeletal abnormalities and high osteopontin levels in Klotho-/- mice. PLoS Genet. 8 (5), e1002726. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1002726 (2012). Epub 2012 May 17.

Komaba, H. & Lanske, B. Role of Klotho in bone and implication for CKD. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. ;27(4):298–304. (2018). https://doi.org/10.1097/MNH.0000000000000423. PMID: 29697410.

Kužmová, Z. et al. Fibroblast growth factor 23 and Klotho are associated with trabecular bone score but not bone mineral density in the early stages of chronic kidney disease: Results of the Cross-Sectional study. Physiol. Res. 70 (Suppl 1), S43–S51. https://doi.org/10.33549/physiolres.934773 (2021).

Desbiens, L. C., Sidibé, A., Ung, R. V. & Mac-Way, F. FGF23-Klotho Axis and fractures in patients without and with early CKD: A Case-Cohort analysis of cartagene. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 107 (6), e2502–e2512. https://doi.org/10.1210/clinem/dgac071 (2022).

Ribeiro, A. L. et al. FGF23-klotho axis as predictive factors of fractures in type 2 diabetics with early chronic kidney disease. J. Diabetes Complications. 34 (1), 107476. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2019.107476 (2020). Epub 2019 Oct 31.

Chalhoub, D. et al. Association of serum Klotho with loss of bone mineral density and fracture risk in older adults. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 64 (12), e304–e308. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.14661 (2016).

Heijboer, A. C. et al. Laboratory aspects of Circulating α-Klotho. Nephrol. Dial Transpl. 28 (9), 2283–2287. https://doi.org/10.1093/ndt/gft236 (2013).

Komaba, H. Roles of PTH and FGF23 in kidney failure: A focus on nonclassical effects. Clin. Exp. Nephrol. 27 (5), 395–401. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10157-023-02336-y (2023).

Donate-Correa, J. et al. Oxidative stress, and mitochondrial damage in kidney disease. Antioxid. (Basel). 12 (2), 239. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox12020239 (2023).

Elm, E. V. et al. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancent 370 (9596), 1453–1457. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61602-X (2007).

Kawano, K. et al. Klotho gene polymorphisms associated with bone density of aged postmenopausal women. J. Bone Min. Res. 17 (10), 1744–1751. https://doi.org/10.1359/jbmr.2002.17.10.1744 (2002).

Gutiérrez, O. M., Farwell, W. R., Kermah, D. & Taylor, E. N. Racial differences in the relationship between vitamin D, bone mineral density, and parathyroid hormone in the National health and nutrition examination survey. Osteoporos. Int. 22 (6), 1745–1753. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-010-1383-2 (2011).

Zhang, Z. et al. Association between testosterone and serum soluble α-klotho in U.S. Males: a cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatr. 22 (1), 570. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-022-03265-3 (2022).

Gkastaris, K., Goulis, D. G., Potoupnis, M., Anastasilakis, A. D. & Kapetanos, G. Obesity, osteoporosis and bone metabolism. J. Musculoskelet. Neuronal Interact. 20 (3), 372–381 (2020). PMID: 32877973.

Xiao, F. et al. Inverse association between low-density lipoprotein cholesterol and bone mineral density in young- and middle-aged people: the NHANES 2011–2018. Front. Med. (Lausanne). 9, 929709. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2022.929709 (2022).

Zhang, Q. et al. Detecting causal relationship between metabolic traits and osteoporosis using multivariable Mendelian randomization. Osteoporos. Int. 32 (4), 715–725. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-020-05640-5 (2021).

Komaba, H. et al. Klotho expression in osteocytes regulates bone metabolism and controls bone formation. Kidney Int. 92 (3), 599–611. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.kint.2017.02.014 (2017). Epub 2017 Apr 8.

Donate-Correa, J. et al. Klotho in cardiovascular disease: Current and future perspectives. World J. Biol. Chem. 6 (4), 351–357. https://doi.org/10.4331/wjbc.v6.i4.351 (2015).

Courbebaisse, M. & Lanske, B. Biology of fibroblast growth factor 23: From physiology to pathology. Cold Spring Harb Perspect. Med. 8 (5), a031260. https://doi.org/10.1101/cshperspect.a031260 (2018).

Kanbay, M. et al. Klotho in pregnancy and intrauterine development-potential clinical implications: A review from the European renal association CKD-MBD working group. Nephrol. Dial Transpl. 39 (10), 1574–1582. https://doi.org/10.1093/ndt/gfae066 (2024).

Isidro, M. L. & Ruano, B. Bone disease in diabetes. Curr. Diabetes Rev. 6 (3), 144–155. https://doi.org/10.2174/157339910791162970 (2010).

Raska, I. Jr & Broulík, P. The impact of diabetes mellitus on skeletal health: an established phenomenon with inestablished causes? Prague Med. Rep. 106 (2), 137–148 (2005).

Funding

This work was supported by the Innovation Training Project for College Students in Anhui Province (S202410367124).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.N.Z. and R.Q. collected and analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript. X.W.L., J.L., and X.Y.Z collected and reviewed data and contributed to data analysis. L.Y.W. was responsible for the research design of the entire study and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The survey protocol was approved by the NCHS Institutional Review Board, before conducting the survey, and all participants provided informed consent in their own name or a legally authorized representative. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations of the NCHS Institutional Review Board.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, Y., Qi, R., Luo, X. et al. Serum alpha-klotho levels associate with bone mineral density in chronic kidney disease patients from NHANES 2011 to 2016. Sci Rep 15, 18760 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-04024-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-04024-1