Abstract

Depression is a common mood disorder characterized by persistent sadness, loss of interest or pleasure, and a range of cognitive and physical symptoms such as gastrointestinal dysfunction that significantly impair daily functioning. Electroconvulsive Therapy (ECT) remains the treatment of choice and a critical last-resort intervention for patients with severe, treatment-resistant depression, particularly those at high risk of suicide. Evidence suggests that the gut-brain axis, a complex bidirectional communication network, plays a key role in the development of these multifaceted symptoms. This study explores the possibility that ECT may exert its therapeutic effects by modulating gastrointestinal function. In clinical investigation, a notable proportion of patients with major depressive disorder experienced significant alleviation of gastrointestinal symptoms, particularly constipation, following ECT. In preclinical research, Electroconvulsive Shock (ECS) is commonly applied to animal models as an experimental analogue to explore the mechanisms and efficacy of ECT. Complementary experiments in mice revealed that daily ECS not only reversed depressive-like behaviors but also restored colonic motility. This effect was closely associated with the normalization of neural activity in the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus (PVN), a key brain region involved in autonomic nervous regulation. Importantly, these benefits were abolished by subdiaphragmatic vagotomy, underscoring the pivotal role of the vagus nerve in mediating gut-brain interactions. These findings offer insights into the neural pathways underpinning the gut-brain connection, highlighting the potential of ECT not only as a last line of defense against severe depression but also as a means to address associated gastrointestinal dysfunction.

Similar content being viewed by others

Depression is a mood disorder characterized by persistent feelings of sadness, loss of interest or pleasure in activities, and a range of physical and cognitive symptoms1. Globally, it stands as a leading cause of disability affecting individuals across all demographics2. Beyond psychological manifestations, depression is associated with physical health issues, including gastrointestinal disruptions3. Functional disorders of the digestive system, such as irritable bowel syndrome, often co-occur with affective disorders like depression, anxiety, panic, and post-traumatic stress disorder3. Gastrointestinal symptoms, such as constipation, usually accompany depression. Research indicates that individuals with depression are more susceptible to experiencing gastrointestinal disturbances and changes in bowel habits, including constipation4,5. Large-scale cross-sectional studies have reported that 9–40% of individuals with depression also experience constipation6,7. Furthermore, commonly prescribed antidepressant medications, such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and tricyclic antidepressants, are known to induce gastrointestinal side effects, including constipation, which can exacerbate the burden of depression8.

Electroconvulsive Therapy (ECT), a well-established treatment for major depressive disorder (MDD) and other psychiatric disorders, involves inducing controlled seizures in the brain using electrical currents9,10. Despite its effectiveness, the precise mechanisms underlying ECT’s therapeutic effects remain incompletely understood11. ECT modulates neurotransmission processes and influences the expression and release of various neurochemicals in the brain, including neurotransmitters, neurotrophic factors, and hormones12. ECT induces alterations in multiple brain regions, notably affecting the prefrontal cortex, hippocampus, amygdala, and thalamus13. These cerebral areas are pivotal not only in emotional and cognitive processes but also in regulating gastrointestinal function 14,15. However, while ECT is recognized for its impact on neurotransmitter levels and neuroplasticity, its specific effects on gastrointestinal function, particularly in alleviating constipation, are not thoroughly elucidated16. This study aims to investigate these specific effects, supported by clinical observations indicating the therapeutic efficacy of ECT in ameliorating gastrointestinal symptoms associated with depression. We propose that ECT modulates distal colonic motility through interactions involving the thalamus and the subdiaphragmatic vagus nerve, thereby advancing our understanding of the central nervous system’s role in gastrointestinal dynamics during depression treatment.

Results

ECT improves gastrointestinal symptoms and constipation in MDD patients

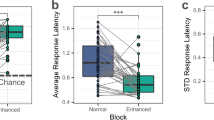

In this study, 111 patients (57 males and 54 females) were included. The mean age of the participants was 40.05 ± 9.64 years, with an average educational level of 11.28 ± 3.18 years. The mean illness duration was 24.50 ± 10.10 months, and patients received an average of 8.23 ± 2.83 ECT sessions. The baseline HAMD scores averaged 23.46 ± 5.96, which significantly decreased to 3.98 ± 2.14 post-ECT (Table 1). Among the 111 patients, 51 (45.95%) exhibited gastrointestinal symptoms. The GSRS score was 8.96 ± 10.06 before ECT and 7.73 ± 8.72 after ECT, indicating that ECT improved gastrointestinal symptoms in MDD patients (p < 0.0001). Factor- analysis indicated that the constipation syndrome score changes primarily contributed to the GSRS score difference. Specifically, 36(32.43%) patients reported constipation. Among these, 28 patients (77.78%) showed improvement in constipation symptoms following ECS treatment, while 8 patients (22.22%) did not show significant improvement. The GSRS-constipation score was 1.56 ± 2.49 before ECT and 0.83 ± 1.65 after ECT, showing significant improvement after ECT (p < 0.0001) (Fig. 1).

Gastrointestinal symptoms and constipation in patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) after Electroconvulsive Therapy (ECT) treatment. Note: (A) Changes in Gastrointestinal Symptom Rating Scale (GSRS) scores between the pre-ECT and post-ECT groups. (B) Changes in GSRS-constipation scores between the pre-ECT and post-ECT groups. (C) Factor analysis of GSRS. ****p < 0.0001.

ECS improves depressive-like behaviors in mice

The CRS model was used to induce depressive-like behavior in mice. After a 7-day acclimatization period, the mice were divided into three groups: HC-Sham, CRS-Sham, and CRS-ECS. Mice in the CRS groups were subjected to restraint stress for 8 h daily for 21 days. On the 22nd day, the CRS-ECS group received ECS once daily for 5 days (Fig. 2A).

ECS improves depressive-like behaviors in CRS mice. Note: (A) Schematic representation of the experimental procedure for chronic restraint stress (CRS) mice subjected to Electroconvulsive Shock (ECS) and subsequent behavioral and distal colon motility tests. (B,C) time spent in center of the HC-Sham group, the CRS-sham group, and the CRS-ECS group mice in open field test (OFT), as well as (C) count into center. (D) The preference for sucrose (amount of sucrose consumed/total water intake in 48 h of the mice between the HC-Sham group, the CRS-sham group, and the CRS-ECS group. (E and F) The immobility (immobile time per minute) of the mice in the TST and FST between the HC-Sham group, the CRS-sham group, and the CRS-ECS group. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA followed by appropriate post hoc tests (Tukey’s multiple comparisons test) to assess differences among groups, n = 10. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001.

Behavioral assessments revealed that the CRS group showed reduced time/count spent in the center of the OFT, lower SPT indices, and prolonged immobility times in both TST and FST compared to the control group. After ECS treatment, the CRS-ECS group exhibited behaviors similar to the healthy control group, indicating that ECS effectively improves depressive-like behaviors in mice (Figs. 2B–F).

ECS improves distal colon motility in CRS mice

To examine ECS’s impact on colonic motility, colon transit times were measured. CRS-Sham mice had longer colon transit times compared to HC-Sham mice, in which ECS sessions over five days effectively improved colonic motility (Fig. 3B). Mice were divided into subgroups receiving varying frequencies of ECS (1, 3, 5, 8). ECS improved colonic motility in CRS mice, with higher frequencies accelerating recovery (Fig. 3A–C). Due to the structural specificity of the gastrointestinal tract, it can be further divided into the stomach and different segments of the intestine. To more precisely understand the affected specific regions of the intestine, we assessed the gastric emptying ability and fecal water content in mice to evaluate the regional motility of the stomach and intestines. The results showed that there were no statistically significant differences in gastric emptying ability and fecal water content among the groups (Fig. 3–E).

ECS improves distal colon motility in CRS mice. Note: (A) Schematic representation of the experimental procedure for chronic restraint stress (CRS) mice subjected to varying frequencies of Electroconvulsive Shock (ECS) and subsequent distal colon motility tests. (B,C) Bead latency test to measure colon transit time. (D,E) Results showing no statistically significant differences between groups in gastric emptying capacity and fecal water content. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA followed by appropriate post hoc tests (Tukey’s multiple comparisons test) to assess differences among groups, n = 10. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001.

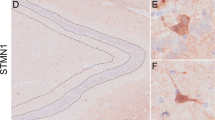

ECS reduces c-Fos activation in the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus (PVN) of CRS mice

c-Fos staining was performed to assess neural activation in the PVN brain region. CRS-Sham mice exhibited excessive c-Fos activation compared to HC-Sham mice. However, CRS-ECS mice showed a reversal of this overactivation, suggesting ECS’s role in modulating brain regions associated with gastrointestinal function (Fig. 4).

Electroconvulsive shock (ECS) attenuates c-Fos activation within the paraventricular nucleus in chronic restraint stress (CRS) mice. Note: c-Fos staining in the PVN of the HC-Sham group, the CRS-sham group, and the CRS-ECS group mice. The number of c-Fos-expressing neurons in the Hypothalamic Paraventricular nucleus (PVN) (n = 3). *p < 0.05.

Vagotomy blocks ECS-induced improvement in colon motility

To explore the role of the vagus nerve, mice underwent subdiaphragmatic vagotomy. CRS-sdVx-ECS mice did not show ECS-induced improvements in colonic motility, indicating the vagus nerve’s involvement in mediating ECS effects on gastrointestinal function (Fig. 5A–C).

Vagotomy blocks the improvement of colon motility disorder by ECS in mice. Note: (A) Schematic representation of the experimental procedure for chronic restraint stress (CRS) mice subjected to subdiaphragmatic vagotomy (sdVx) and Electroconvulsive Shock (ECS), followed by subsequent gastrointestinal (GI) motility tests. (B) Images of the stomach in the sham and vagotomy groups. (C) Bead latency test to measure colon transit time. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA followed by appropriate post hoc tests (Tukey’s multiple comparisons test) to assess differences among groups, n = 10. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

Discussion

This study is the first to systematically evaluate the direct effects of ECT on gastrointestinal function in MDD patients and explore the role of the PVN. The results indicate that ECT significantly improves gastrointestinal function, particularly alleviating constipation, which is common in MDD patients. It was found that 45.95% of patients reported gastrointestinal symptoms, and ECT significantly improved these symptoms in MDD patients, as evidenced by a reduction in GSRS scores following treatment. Factor analysis further revealed that constipation syndrome contributed most to the overall GSRS score change. Specifically, 32.43% of patients reported constipation, and their GSRS-constipation scores significantly decreased after ECT, indicating a substantial alleviation of constipation symptoms. Supporting evidence from animal studies shows that ECS improves colonic motility in CRS mice, and this effect is dose-dependent. These results are consistent with epidemiological evidence demonstrating a strong association between depression and gastrointestinal dysfunction. In a prospective UK Biobank cohort, individuals with premorbid constipation had a 48% higher risk of developing depression5, while cross-sectional NHANES data show that patients with moderate-to-severe depressive symptoms report significantly increased odds of gastrointestinal complaints-including constipation, diarrhea, and stomach illness-compared with non-depressed individuals17. ECS may indirectly improve gastrointestinal function by modulating brain electrical activity. Furthermore, ECT could directly enhance gastrointestinal symptoms by altering the activity of specific brain regions, particularly through the modulation of areas such as the PVN.

Further mechanistic exploration revealed that ECS modulates PVN activity. c-Fos staining demonstrated significantly elevated PVN activity in CRS mice, which was reduced following ECS, suggesting that PVN modulation is central to ECS-induced gastrointestinal improvements. This is consistent with the role of the PVN in regulating gastrointestinal motility and its involvement in stress responses and emotional regulation. Previous study has demonstrated that the PVN plays a crucial role in regulating gastrointestinal motility17,18,19. Corticotropin-releasing factor receptors within the PVN can influence colonic function through the CRF/CRF1 signaling pathway, modulating both behavioral and autonomic responses. Furthermore, studies have indicated that the injection of CRF9–41, a synthetic peptide antagonist of corticotropin-releasing factor, into the PVN can regulate colonic motility and defecation responses20,21. Additionally, the PVN collaborates with the sacral parasympathetic nucleus to activate neurons that control colonic function, further influencing colonic motility21. Through these mechanisms, the PVN plays a pivotal role in regulating colonic motility and its stress response. In addition to gastrointestinal motility regulation, the PVN is also closely linked to emotional regulation22. These findings provide new insights into the treatment of gastrointestinal-related disorders. Moreover, the PVN’s involvement in stress responses and emotional regulation may indirectly modulate colonic motility via neuroendocrine pathways, including the release of corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH)23,24,25. To clarify the PVN’s role in colonic motility and its connection to the brain-gut axis, we performed subdiaphragmatic vagotomy to determine whether its effects are mediated via the vagus nerve24,26.

The vagus nerve serves as a critical connection between the brain and the gastrointestinal system, playing a vital role in regulating gastrointestinal functions. Studies have shown that the vagus nerve modulates gastrointestinal smooth muscle contractions, facilitating the movement of food and waste; it also influences the secretion of digestive enzymes and maintains healthy gut motility27. In this study, the role of the vagus nerve in ECT-induced gastrointestinal improvement was explored through subdiaphragmatic vagotomy. We found that ECS improved colonic motility in CRS mice, but this effect was lost in vagotomized mice, indicating that ECT may improve gastrointestinal function through the vagus nerve pathway. These results are consistent with findings from Breit et al., who demonstrated the crucial role of the vagus nerve in activating gastrointestinal smooth muscles and promoting the movement of food and waste28. The vagus nerve’s functions extend beyond motility regulation, influencing the secretion of digestive enzymes and the maintenance of gastrointestinal health28,29. Additionally, the vagus nerve, through its feedback mechanism with the brain, plays a key role in regulating gastrointestinal functions, forming an essential part of the brain-gut axis. Therefore, the mechanisms by which ECS improves gastrointestinal function may be closely related to its modulation of gastrointestinal smooth muscle activity and digestive enzyme secretion through the vagus nerve.

Traditional oral antidepressants often take longer to produce therapeutic effects and come with side effects, including gastrointestinal symptoms like constipation8. The brain-gut axis links depression to gut physiology, often resulting in gastrointestinal dysfunction that reduces the quality of life30,31. Despite its efficacy in treating depression, ECT is associated with discomfort and cognitive side effects32,33. Given these concerns, exploring additional treatments that address both depression and gastrointestinal symptoms is crucial. While ECT offers rapid relief, further understanding of its mechanisms may pave the way for developing less invasive neural modulation techniques. This study is the first to systematically evaluate the direct effects of ECT on these symptoms, providing new insights and data that build on existing literature. Targeting specific brain regions like the PVN, in combination with traditional antidepressants, may offer more effective treatments with fewer side effects for patients with depression.

This study is the first to assess the direct effects of ECT on gastrointestinal function in MDD patients and explore the role of the PVN. However, the underlying mechanisms remain unclear. Future research should focus on animal studies to better understand how the PVN and vagus nerve regulate gastrointestinal function. Larger clinical trials are also needed to confirm ECT’s efficacy and safety in treating gastrointestinal symptoms in MDD. As non-invasive brain stimulation techniques evolve, personalized treatments addressing both depression and gastrointestinal issues may emerge.

To further dissect the precise mechanisms by which ECS modulates gastrointestinal motility, future studies could employ optogenetic or chemogenetic manipulation of CRF-expressing PVN neurons to test causality, record vagal nerve activity in parallel with colonic motility recordings, combine c-Fos mapping with cell-type markers or single-cell transcriptomics to pinpoint responsive cell populations, and use germ-free or antibiotic-treated mouse models to evaluate microbiota contributions.

Conclusion

Both clinical and animal studies have demonstrated that ECT significantly improves gastrointestinal symptoms in MDD, particularly in relieving constipation. Subsequent studies have shown that ECT improves of colonic motility is associated with modulation of PVN activity and its subdiaphragmatic vagus nerve pathways. These findings highlight the potential of ECT as an effective treatment for both depression and its associated gastrointestinal disorders.

Methods

Human

A total of 111 patients diagnosed with major depressive disorder were recruited from Anhui Mental Health Center between June 2013 and March 2022. Diagnosis was conducted by two psychiatrists based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-5 (DSM-5) criteria34. Exclusion criteria were predefined as follows: (1) age younger than 18 years or older than 65 years; (2) pregnancy, substance abuse, severe physical illness, current or past neurological disorders, or other psychiatric comorbidities (e.g., schizophrenia, bipolar I or II disorder, and Axis II disorders) assessed using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5 (SCID-5); (3) received fewer than 5 or more than 12 ECT sessions (n = 6). Ultimately, 111 participants were included in this study (Table 1).

This study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical approval was obtained from the local ethics committee of Anhui Medical University (Study No. 84230095). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants before their inclusion in the study.

Clinical assessment

The MDD patients were interviewed face-to-face by trained psychiatrists. To improve the objectivity and reliability of the measurements, all the interviewers were psychiatrists with at least 5 years of experience in clinical practice and were well-trained for this project. Basic socio-demographic and clinical data were collected, and participants completed a self-administered questionnaire. The questionnaire was administered at baseline, 12–24 h before the first ECT session, and at follow-up, 24–72 h after the final ECT session.

Depression severity was evaluated using the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAMD-17). Patients completed the Gastrointestinal Symptom Rating Scale (GSRS), a self-administered questionnaire consisting of 15 multiple-choice items. The GSRS assesses five gastrointestinal symptom domains: abdominal pain (including abdominal pain, hunger pains, and nausea), reflux syndrome (heartburn and acid regurgitation), diarrhea syndrome (diarrhea, loose stools, and an urgent need for defecation), indigestion syndrome (borborygmus, abdominal distension, eructation, and increased flatus), and constipation syndrome (constipation, hard stools, and a feeling of incomplete evacuation)35.

Animals

All animals (C57BL/6J (B6), male, aged 6–7 weeks) used in this study were purchased from Gempharmatech, China. Unless otherwise noted, all the mice were housed in groups of four/five and kept on a 12/12 h light/dark cycle in a temperature-controlled environment (22 ± 1 °C) and had free access to food and drinking water throughout the experiment. In total, approximately 140 male mice were used across all experimental procedures. Mice were anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection with 2% sodium pentobarbital at a dose of 40 mg/kg, followed by euthanasia via cardiac perfusion. All animal procedures were approved by the Laboratory Animal Ethics Committee of Anhui Medical University, and were conducted in accordance with the relevant institutional guidelines and regulations, including the ARRIVE guidelines (https://arriveguidelines.org) and the AVMA Guidelines for the Euthanasia of Animals (2020).

Chronic restraint stress (CRS)

Mice were restrained in a plastic, air-accessible cylinder for 8 h daily (9:00–17:00) over 21 consecutive days. The size of the cylinder was similar to that of the animal, which made the animal almost immobile in the cylinder.

Electroconvulsive shock (ECS)

ECS was administered using auricular electrodes (Ugo Basile SRL, Gemonio VA, Italy) under anesthesia36. Mice were treated with 2% isoflurane. Thirty minutes later, ECS (100 Hz, 12 mA, pulse width 0.5 ms, duration 1 s) was administered using an electrical stimulator and an isolator. ECS induced visible tonic–clonic seizures lasting for 10–20 s37. ECS was performed once daily, 5 times in 5 days. For mice in the sham groups, only 2% isoflurane was administered using similar auricular electrodes without electrical stimulation.

Open field test (OFT)

The open field test was conducted in a rectangular plastic box (50 cm × 50 cm × 50 cm) divided into 16 (4 × 4) identical sectors (12.5 cm × 12.5 cm)38. The field was subdivided into peripheral and central sectors, where the central sector included 4 central squares (2 × 2), and the peripheral sector was the remaining squares. The mouse was placed into the center of an open field and allowed to explore for 6 min. The apparatus was thoroughly cleaned with diluted 75% ethanol between each trial. A video tracking system (Shanghai Xinruan Information Technology Co., Ltd; China) was used to analyze locomotor activity by tracking the distance traveled. Time spent and entries into the center were measured as indicators of anxiolytic behavior.

Sucrose preference test (SPT)

A sucrose preference test was performed as previously described: mice were acclimated to two bottles of water for 24 h while single-housed, followed by a 24-h water deprivation period. Subsequently, a 48-h testing period (starting at 14:00) involved providing mice with one bottle of 1% sucrose (w/v) and one bottle of water. The position of the two bottles was switched at 24 h. The percentage of sucrose preference was calculated as the following calculation method: % Sucrose preference = ((the consumption of 1% sucrose/the total liquid consumed (water and sucrose))) × 10039.

Tail suspension test (TST)

Mice were suspended by their tails from a lever in a 30 × 15 × 15 cm enclosure. Movements were recorded for 5 min in a quiet environment40. Animal behavior was recorded using a side camera for 5 min, and immobility duration during the last 5 min was quantified by two blinded, trained experimenters. Data were presented as immobility time across different groups.

Forced swim test (FST)

Mice were placed in a glass beaker (30 cm tall, 20 cm diameter) filled with water at a height of 15 cm and maintained at 30 ± 1 °C. Mice were allowed to swim for 6 min41, and a video camera was in front of the beakers so that every beaker was in a way that allowed the clear observation of the animals’ behavior later on while viewing the footage. Immobility was quantified independently by two blinded, trained experimenters. Code the duration spent as “Immobile” if the mouse is floating without any movement except for those necessary for keeping the nose above water. Code the duration of time spent as “Swimming” if the movement of forelimbs or hind limbs in a paddling fashion is observed. Data were expressed as immobility time (min) in different groups.

Bead latency

Distal colonic motility was evaluated by a modified bead expulsion test. Under brief isoflurane anesthesia, a lubricated glass bead (2 mm in diameter) was carefully inserted into the distal colon at a depth of approximately 2 cm from the anus using a smooth glass rod. Following insertion, mice were individually housed in clean cages without access to food or water and closely observed. The time required for bead expulsion was recorded for each animal. A longer latency to expel the bead was interpreted as reduced colonic propulsive activity42.

Gastric emptying test

To assess gastric motility, mice were fasted for 12 h prior to the experiment with free access to water. During the formal testing phase, each mouse was placed in a separate clean cage and provided with a measured amount of standard pellet feed (the initial weight was recorded accurately). The feeding period lasted for 6 h, during which the mice had free access to food. After feeding, the remaining food was weighed to calculate the net intake (initial weight—remaining weight). The food was then removed, and the mice were left undisturbed for 2 h. After euthanasia, the stomach was rapidly excised and the contents were weighed for their wet weight. Gastric emptying efficiency was calculated using the following formula: Gastric Emptying Rate (%) = [1 − (stomach contents weight / food intake)] × 10043.

Fecal moisture content test

Fresh fecal samples were collected at a fixed time (10:00 AM), immediately weighed to obtain their wet weight, and recorded. The samples were then dried at a constant temperature of 60 °C for 24 h before determining the dry weight. The moisture content was calculated using the following formula: Fecal Moisture Content (%) = [(Wet weight − Dry weight)/Wet weight] × 100.

c-Fos staining

c-Fos staining was conducted following established protocols. Fixed brains were cut into 50-μm-thick slices using a cryostat. The brain slices were transferred into 12-well plates and washed 4 times with PBS for 10 minutes each time. Slices were loaded into 12-well plates, permeated with 0.3% Triton X-100 in PBS, then blocked in blocking solution (5% donkey serum (w/v), 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS) for 1 h and then incubated with primary antibody (Rabbit-anti-c-Fos (9F6) antibody, dilution 1:1000) in blocking solution overnight in 4 °C, followed by washing in PBS three times for 10 minutes each. The slices were then incubated in secondary antibody (Anti-Rabbit IgG (H + L), CF 488A antibody, dilution 1:200) at room temperature for 5 h, followed by washing in PBS three times. Finally, the slices of an entire mouse brain were mounted onto a customized slide by slicing with the same surface upward. Images were analyzed using ImageJ software44.

Vagotomy

Subdiaphragmatic vagotomy (sdVx) was performed as previously described45,46. Briefly, mice were anesthetized with inhaled isoflurane and placed supine. A midline incision was made on the upper abdomen (approx. 2 cm) was created to expose the stomach and lower esophagus. Both vagus nerve branches in front of and behind the esophagus and the surrounding connective tissue were dissected.For mice in the sham groups, only laparotomy was performed. All surgical procedures were conducted under a microscope by a single researcher. Animals were monitored postoperatively and allowed to recover for 21 days before subsequent procedures. The completeness of VX was verified during postmortem examination of vagal nerve endings using a microscope47.

Statistical analysis

GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software) was used for statistical analysis, with normal distribution and variations evaluated. Levene’s test was performed to calculate variance equality. When appropriate, if the sample data followed normal distributions assessed by the Shapiro–Wilk test, significance between groups was assessed using unpaired/paired two-sided t-tests. Otherwise, the non-parametric Mann–Whitney tests or Wilcoxon tests were used. For comparisons among multiple groups, one-way ANOVA was performed, followed by appropriate post hoc tests such as Tukey’s test to determine specific group differences if normality assumptions were met. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001. Unless otherwise stated, all statistical tests are two-tailed.

Data availability

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Disner, S. G., Beevers, C. G., Haigh, E. A. & Beck, A. T. Neural mechanisms of the cognitive model of depression. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 12, 467–477. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn3027 (2011).

Friedrich, M. J. Depression is the leading cause of disability around the world. JAMA 317, 1517. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2017.3826 (2017).

Mayer, E. A., Craske, M. & Naliboff, B. D. Depression, anxiety, and the gastrointestinal system. J. Clin. Psychiatry. 62 Suppl 8, 28–36 (2001). discussion 37.

Barberio, B., Judge, C., Savarino, E. V. & Ford, A. C. Global prevalence of functional constipation according to the Rome criteria: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 6, 638–648. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-1253(21)00111-4 (2021).

Yun, Q. et al. Constipation preceding depression: A population-based cohort study. EClinicalMedicine 67, 102371. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2023.102371 (2024).

Ballou, S. et al. Chronic diarrhea and constipation are more common in depressed individuals. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 17, 2696–2703. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2019.03.046 (2019).

Adibi, P. et al. Relationship between depression and constipation: Results from a large cross-sectional study in adults. Korean J. Gastroenterol. 80, 77–84. https://doi.org/10.4166/kjg.2022.038 (2022).

Oliva, V. et al. Gastrointestinal side effects associated with antidepressant treatments in patients with major depressive disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry. 109, 110266. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pnpbp.2021.110266 (2021).

Duxbury, A. et al. What is the process by which a decision to administer electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) or not is made? A grounded theory informed study of the multi-disciplinary professionals involved. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 53, 785–793. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-018-1541-y (2018).

Rojas, M. et al. Electroconvulsive therapy in psychiatric disorders: A narrative review exploring neuroendocrine-immune therapeutic mechanisms and clinical implications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms23136918 (2022).

Hoy, K. E. & Fitzgerald, P. B. Brain stimulation in psychiatry and its effects on cognition. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 6, 267–275. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrneurol.2010.30 (2010).

Segi-Nishida, E. Exploration of new molecular mechanisms for antidepressant actions of electroconvulsive seizure. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 34, 939–944. https://doi.org/10.1248/bpb.34.939 (2011).

Leaver, A. M. et al. Mechanisms of antidepressant response to electroconvulsive therapy studied with perfusion magnetic resonance imaging. Biol. Psychiatry. 85, 466–476. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2018.09.021 (2019).

Browning, K. N. & Travagli, R. A. Central nervous system control of gastrointestinal motility and secretion and modulation of gastrointestinal functions. Compr. Physiol. 4, 1339–1368. https://doi.org/10.1002/cphy.c130055 (2014).

Levinthal, D. J. & Strick, P. L. Multiple areas of the cerebral cortex influence the stomach. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 117, 13078–13083. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2002737117 (2020).

Singh, A. & Kar, S. K. How electroconvulsive therapy works?? Understanding the Neurobiological mechanisms. Clin. Psychopharmacol. Neurosci. 15, 210–221. https://doi.org/10.9758/cpn.2017.15.3.210 (2017).

Monnikes, H. et al. Neuropeptide Y in the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus stimulates colonic transit by peripheral cholinergic and central CRF pathways. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 12, 343–352. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2982.2000.00212.x (2000).

Monnikes, H. et al. Involvement of CCK in the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus in the CNS regulation of colonic motility. Digestion 62, 178–184. https://doi.org/10.1159/000007811 (2000).

Tache, Y., Larauche, M., Yuan, P. Q. & Million, M. Brain and gut CRF signaling: Biological actions and role in the gastrointestinal tract. Curr. Mol. Pharmacol. 11, 51–71. https://doi.org/10.2174/1874467210666170224095741 (2018).

Tache, Y. & Million, M. Role of corticotropin-releasing factor signaling in Stress-related alterations of colonic motility and hyperalgesia. J. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 21, 8–24. https://doi.org/10.5056/jnm14162 (2015).

Stengel, A. & Tache, Y. Neuroendocrine control of the gut during stress: Corticotropin-releasing factor signaling pathways in the spotlight. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 71, 219–239. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.physiol.010908.163221 (2009).

Wang, J. et al. Role and mechanism of PVN-sympathetic-adipose circuit in depression and insulin resistance induced by chronic stress. EMBO Rep. 24, e57176. https://doi.org/10.15252/embr.202357176 (2023).

Wang, X. Y. et al. A neural circuit for gastric motility disorders driven by gastric dilation in mice. Front. Neurosci. 17, 1069198. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2023.1069198 (2023).

Kirouac, G. J. Placing the paraventricular nucleus of the thalamus within the brain circuits that control behavior. Neurosci. Biobehav Rev. 56, 315–329. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2015.08.005 (2015).

Kirouac, G. J. The paraventricular nucleus of the thalamus as an integrating and relay node in the brain anxiety network. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 15, 627633. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnbeh.2021.627633 (2021).

Cho, D. et al. Paraventricular thalamic MC3R circuits link energy homeostasis with anxiety-related behavior. J. Neurosci. 43, 6280–6296. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0704-23.2023 (2023).

Prescott, S. L. & Liberles, S. D. Internal senses of the vagus nerve. Neuron 110, 579–599. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2021.12.020 (2022).

Breit, S., Kupferberg, A., Rogler, G. & Hasler, G. Vagus nerve as modulator of the brain-gut axis in psychiatric and inflammatory disorders. Front. Psychiatry. 9, 44. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00044 (2018).

Furness, J. B. The enteric nervous system and neurogastroenterology. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 9, 286–294. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrgastro.2012.32 (2012).

Liu, L. et al. Gut microbiota and its metabolites in depression: From pathogenesis to treatment. EBioMedicine 90, 104527. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ebiom.2023.104527 (2023).

Brushett, S. et al. Gut feelings: The relations between depression, anxiety, psychotropic drugs and the gut Microbiome. Gut Microbes. 15, 2281360. https://doi.org/10.1080/19490976.2023.2281360 (2023).

Trifu, S., Sevcenco, A., Stanescu, M., Dragoi, A. M. & Cristea, M. B. Efficacy of electroconvulsive therapy as a potential first-choice treatment in treatment-resistant depression (Review). Exp. Ther. Med. 22, 1281. https://doi.org/10.3892/etm.2021.10716 (2021).

Porter, R. J. et al. Cognitive side-effects of electroconvulsive therapy: What are they, how to monitor them and what to tell patients. BJPsych Open. 6, e40. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2020.17 (2020).

Spiegel, D. et al. Dissociative disorders in DSM-5. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 9, 299–326. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050212-185531 (2013).

Tian, P. et al. Multi-probiotics ameliorate major depressive disorder and accompanying gastrointestinal syndromes via serotonergic system regulation. J. Adv. Res. 45, 117–125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jare.2022.05.003 (2023).

Weber, T. et al. Genetic fate mapping of type-1 stem cell-dependent increase in newborn hippocampal neurons after electroconvulsive seizures. Hippocampus 23, 1321–1330. https://doi.org/10.1002/hipo.22171 (2013).

Nakamura-Maruyama, E. et al. Ryanodine receptors are involved in the improvement of depression-like behaviors through electroconvulsive shock in stressed mice. Brain Stimul. 14, 36–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brs.2020.11.001 (2021).

Sakata, K., Jin, L. & Jha, S. Lack of promoter IV-driven BDNF transcription results in depression-like behavior. Genes Brain Behav. 9, 712–721. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1601-183X.2010.00605.x (2010).

An, K. et al. A circadian rhythm-gated subcortical pathway for nighttime-light-induced depressive-like behaviors in mice. Nat. Neurosci. 23, 869–880. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41593-020-0640-8 (2020).

Cryan, J. F., Mombereau, C. & Vassout, A. The tail suspension test as a model for assessing antidepressant activity: Review of pharmacological and genetic studies in mice. Neurosci. Biobehav Rev. 29, 571–625. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2005.03.009 (2005).

Porsolt, R. D., Anton, G., Blavet, N. & Jalfre, M. Behavioural despair in rats: A new model sensitive to antidepressant treatments. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 47, 379–391. https://doi.org/10.1016/0014-2999(78)90118-8 (1978).

Lee, J. Y., Tuazon, J. P., Ehrhart, J., Sanberg, P. R. & Borlongan, C. V. Gutting the brain of inflammation: A key role of gut Microbiome in human umbilical cord blood plasma therapy in Parkinson’s disease model. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 23, 5466–5474. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcmm.14429 (2019).

Nobis, S. et al. Delayed gastric emptying and altered antrum protein metabolism during activity-based anorexia. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 30, e13305. https://doi.org/10.1111/nmo.13305 (2018).

Hu, J. et al. Amino acid formula induces microbiota dysbiosis and depressive-like behavior in mice. Cell. Rep. 43, 113817. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2024.113817 (2024).

Wang, S. et al. Ingestion of Lactobacillus intestinalis and Lactobacillus reuteri causes depression- and anhedonia-like phenotypes in antibiotic-treated mice via the vagus nerve. J. Neuroinflammation. 17, 241. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12974-020-01916-z (2020).

Zhang, J. et al. A key role of the subdiaphragmatic vagus nerve in the depression-like phenotype and abnormal composition of gut microbiota in mice after lipopolysaccharide administration. Transl Psychiatry. 10, 186. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-020-00878-3 (2020).

Liu, Y., Sanderson, D., Mian, M. F., McVey Neufeld, K. A. & Forsythe, P. Loss of vagal integrity disrupts immune components of the microbiota-gut-brain axis and inhibits the effect of Lactobacillus rhamnosus on behavior and the corticosterone stress response. Neuropharmacology 195, 108682. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropharm.2021.108682 (2021).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all participants for their contributions to this study.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 32071054) and Anhui Provincial Science Fund for Distinguished Young Scholars (1808085J23).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Mengyao Dai, Yanzhang Li, and Yanghua Tian provided the conception of the research design; Mengyao Dai and Yanghua Tian conducted the formal analysis and writing original draft; Mengyao Dai, Yanzhang Li and Yanghua Tian participated writing-review and editing process; All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Dai, M., Li, Y. & Tian, Y. Electroconvulsive therapy improves distal colonic motility via the subdiaphragmatic vagus nerve in depressive-like mice. Sci Rep 15, 19597 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-04114-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-04114-0