Abstract

Urban green spaces (UGSs) deliver vital ecological and social benefits, and their integrated management significantly contributes to ecological sustainability and public well-being. However, existing studies tend to separately examine ecological and social values of various UGS types, lacking comprehensive assessments of their interactions. In response, this study established an integrated biotope classification system based on vegetation structure and conducted extensive field surveys to map urban biotopes in Xi’an city. Ecological values were evaluated through twelve selected indicators, including biodiversity, air quality regulation, and carbon storage. Social values were assessed using the SolVES model across six dimensions: aesthetics, recreation, cultural , spiritual, biodiversity, and therapeutics. The coupling coordination degree (CCD) between ecological and social values was subsequently calculated, and key influencing factors were analyzed via Geodetector. The results reveal that: (1) Xi’an encompasses 28 distinct biotope types, with green spaces occupying the largest area (2.89 km2; 79.97%) and blue spaces the smallest (0.32 km2; 8.72%). (2) The CCD between ecological and social values is on the verge of disorder (0.467), indicating a critical need for improved coordination. (3) Open green spaces with herbaceous vegetation (G O He) exhibit the highest CCD. Conversely, closed one-layer broad-leaved forests primarily covered by hardscape (G C Ha B L-1) and closed multi-layer broad-leaved forests primarily covered by hardscape (G C Ha B L-2) present the lowest coordination levels. (4) Ecological characteristics significantly influence CCD, highlighting the importance of detailed biotope classification. The results emphasize that enhancing spatial configurations and optimizing functional arrangements within UGSs are essential strategies for improving eco-social synergies and coupling coordination. This study provides valuable insights and practical recommendations for targeted urban planning and sustainable development of urban green infrastructure in Xi’an and similar rapidly urbanizing regions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Rapid urbanization has resulted in profound environmental and social challenges globally, particularly within densely populated urban areas1. Urban green spaces (UGSs) play a crucial role in addressing these challenges by providing diverse ecological services and enhancing the quality of urban life through social benefits2. Consequently, increasing attention has been devoted to planning and improving UGSs, especially through government-led initiatives aimed at mitigating public health issues and fostering sustainable urban environments3.

UGSs deliver dual ecological and social benefits, reinforcing their importance in urban development agendas4. Ecologically, UGSs provide significant services, including carbon sequestration, pollutant absorption, biodiversity conservation, and mitigation of urban heat islands5,6,7. Simultaneously, they offer essential social functions such as recreation, aesthetic appreciation, cultural engagement, and health improvement8. Despite these benefits, harmonizing ecological and social objectives often poses substantial challenges9. For instance, recreational activities, while socially beneficial, may adversely impact vegetation and soil integrity. Conversely, conservation measures aiming at ecological preservation may limit recreational accessibility and social engagement opportunities10,11. Achieving a balanced integration of ecological and social functionalities within UGSs is thus essential for enhancing urban sustainability and residents’ quality of life12.

To effectively manage the increasing conflicts between urban expansion and UGS conservation, accurately assessing both ecological and social values of these spaces is crucial. Research on ecological values of UGSs typically emphasizes quantification of ecosystem services such as climate regulation, air quality enhancement, and biodiversity conservation13,14,15,16,17,18. However, the lack of standardized indicators continues to limit comprehensive ecological assessments15,19.

In comparison, the social value of UGSs is frequently assessed as intangible, non-market benefits reflecting residents’ perceptions, including cultural, aesthetic, and recreational services20. Tools such as Public Participation GIS (PPGIS) and the Social Values for Ecosystem Services (SolVES) model have emerged as effective methods for capturing spatial variations in these intangible benefits8,21,22,23. Despite their significance, studies examining both ecological and social dimensions simultaneously are scarce, especially those addressing comprehensive UGS systems rather than focusing narrowly on large parks or scenic areas24,25. This gap reduces the potential for precise, site-specific planning and management interventions.

To overcome these limitations, biotope mapping provides a systematic approach for classifying urban ecosystems, integrating land cover and biological components such as flora and fauna26. While widely applied in urban conservation and planning contexts27, traditional biotope classifications frequently neglect vegetation structure, a key determinant of both ecological functions and social perceptions28,29. Vegetation density and vertical structure significantly influence microclimatic variations between green and non-green urban areas, impacting ecological services and public comfort30. Furthermore, specific vegetation structures, such as tree-shrub-herb layers, critically affect atmospheric particulate matter regulation and negative ion production31. Large, open spaces also significantly enhance residents’ recreational experiences and perceptions32. However, few studies have explored biotopes as the fundamental units for comprehensively analyzing multidimensional values within UGSs.

Addressing the pressing need for sustainable urban development, this study incorporates vegetation structure into a biotope classification system and systematically investigates the coupling coordination between ecological and social values of UGSs in urban historical areas of Xi’an. The objectives of this research are to: (1) develop an integrated biotope classification system through field surveys and cartographic analysis to generate detailed biotope maps; (2) evaluate ecological and social values of different biotopes within UGSs using 12 ecological indicators (including biodiversity, green quantity, air quality regulation, and carbon storage among others) and 6 social indicators (including aesthetics, recreation, spiritual, and culture among others); (3) assess the coupling coordination relationship between these values and identify key influencing factors. Ultimately, the research aims to offer tailored strategies for optimizing UGSs, guiding urban planning, policy-making, and sustainable green infrastructure development.

Study area and data

Study area

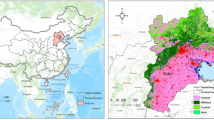

The study area encompasses the historical areas of Xi’an (Fig. 1), situated between 108°55′-108°59′E and 34°15′-34°17′N, covering a total area of 11.07 km2. As the earliest urban center of Xi’an, this region is celebrated for its vibrant commercial activity and rich historical and cultural heritage, which present substantial potential for development33. However, the UGSs in this area face more severe challenges. On one hand, this region is the core area of Xi’an with a large population, leading to a higher demand for the ecological and social value of UGSs. On the other hand, the region needs to balance the protection of historical heritage with the fulfillment of modern urban demands, while being constrained by planning and development limitations. Therefore, how to enhance the ecological and social value of UGSs through conservation and restoration methods within the existing layout of this area is an important task.

Study area.Satellite imagery obtained from Xingqiuditu (https://datacloud.geovisearth.com/) and map created using ArcGIS software (v10.5, Esri, https://www.esri.com/).

Since 2001, various UGSs protection policies have been implemented34, including the establishment of relevant regulations by the government, the definition of indicators for UGSs, the initiation of co-construction and sharing initiatives for UGSs, and the formulation of an UGSs system. The total area of UGSs in the region has expanded to 3.64 km2. This includes prominent parks such as City Ring Park, Revolution Park, Lianhu Park, Children’s Park, and Wuji Park, along with residential land affiliated green space and road and transportation facilities land affiliated green space. These UGSs are primarily characterized as public open spaces, fulfilling essential roles in recreation and therapeutic activities. Studies on Xi’an indicate that UGSs effectively counter urban heat threats through their cooling effects, helping to prevent health risks for residents35. At the same time, UGSs also have an impact on the mental health of the youth population36.

Data sources

Remote sensing imagery data were obtained from the USGS Landsat 8–9 C2 L2SP datasets (https://www.usgs.gov/). Key environmental indicators, including temperature, humidity, normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI), and fractional vegetation cover (FVC), were derived from the processed remote sensing data. Additionally, digital Elevation Model (DEM) data were sourced from the Geospatial Data Cloud (https://www.gscloud.cn/).

Point of Interest (POI) data, which include information on transportation and public facilities, were acquired from Map Lab (https://lbs.amap.com). Road data were downloaded from the OpenStreetMap (https://download.geofabrik.de/) and the 91wemap website (https://www.91wemap.com/). Furthermore, annual average rainfall and temperature data were obtained from the 2022 Statistical Yearbook published by the Xi’an Municipal Bureau of Statistics (http://tjj.xa.gov.cn/). All data utilized in this study pertain to the year 2022, with specific monthly data collected for July and August.

Methods

Urban green space biotope classification

This study commenced with the preliminary processing of 0.5-m resolution remote sensing imagery of Xi’an city, supplemented by field surveys to collect data on the characteristics of UGSs. Based on classification criteria proposed by Qiu et al.37, a biotope classification system that integrates various factors related to vegetation structure was developed, including both horizontal and vertical aspects, as well as tree types (Table 1).

The classification process began by categorizing the study area into gray, green, and blue spaces based on land cover types. Green spaces were further divided into four hierarchical categories: Horizontal Vegetation Structure classifies areas according to the proportion of tree and shrub canopy cover, with categories set at < 10%, 10–30%, 30–70%, and > 70%; Surface Cover Types distinguishes spaces based on their primary cover, which can be either groundcover or hardscape; Vertical Vegetation Structure differentiates areas into one-layer (containing only tree or sub-tree layers) and multi-layer (featuring double tree layers or combinations of trees and shrubs), with open and partly open green spaces further classified by their dominant vegetation type as either herbaceous (including low shrubs < 1 m) or shrubby (shrubs > 1 m); and finally, Species Composition classifies areas according to the tree species present, distinguishing between coniferous, broadleaf, and mixed forests.

Gray spaces were classified according to the percentage of abiotic coverage (60–75%, 75–90%, 90–100%), dominant vegetation (trees, shrubs, herbaceous), species composition (coniferous, broadleaf, or mixed forests), and the type of hard surface. Blue spaces were classified based on waterbody types, such as rivers or ponds.

Once the biotope classification system was established, all biotopes in the study area were surveyed in the field. Data collected from these surveys, along with aerial imagery, were utilized to refine and enhance the preliminary classifications. The data were processed, edited, and analyzed using ArcGIS software (v10.5; ESRI, Redlands, CA), resulting in the creation of a comprehensive biotope map that incorporates various vegetation structure factors. According to relevant studies38,39, the minimum mapping unit for this classification was set at 500 m2.

Ecological value

Existing studies have identified several factors that contribute to the ecological value of UGSs, including plant growth, air regulation, climate regulation, hydrological regulation, carbon sequestration, and carbon storage5,40,41,42,6,43,7,44. Based on the specific conditions of the study area and relevant research, twelve ecological value indicators were identified: vegetation growth condition, green quantity, arbor layer species diversity, dust retention, sulfur dioxide (SO₂) absorption, carbon sequestration, oxygen release, hydrological regulation capacity, temperature regulation capacity, humidity regulation capacity, carbon storage, and noise reduction capacity. The calculation methods for these indicators are detailed below:

Vegetation growth condition

NDVI serves as an effective measure of vegetation growth status and coverage, obtainable through remote sensing image processing45.

Green quantity

The three-dimensional green quantity (3D green biomass) accurately reflects the canopy structure and vegetation density, enhancing the reliability of UGS planning15. It is calculated using the green volume ratio (GVR)46:

where, GVRi is the green volume ratio of biotope I, Ni is the NDVI of biotope I, GQi is the green quantity in cubic meters (m3), and Si is the area of biotope I in square meters (m2).

Arbor layer species diversity

A diverse arbor layer provides habitats for various species and influence herbaceous diversity47. Biodiversity in UGSs is represented by the following formula48:

where, Bi represents arbor layer species diversity, Ni is NDVI, and TC2i and TC3i represent greenness and humidity value of biotope I, respectively.

Dust retention, SO2 absorption, carbon sequestration, oxygen release

UGSs act as natural filters that effectively reduce dust pollution and improve air quality49. The capacities for gas regulation are estimated using the three-dimensional green quantity and established formulas from prior research15,50.

Hydrological regulation capacity

UGSs help regulate stormwater runoff and prevent urban flooding51. The hydrological regulation capacity is estimated by the ratio of impervious surface area to the total area of each biotope, reflecting the capacity of rainwater infiltration.

Temperature regulation capacity, humidity regulation capacity

UGSs provide cooling and humidifying effects52,53. These capacities are represented by the absolute differences in temperature and humidity within each biotope.

Carbon storage

UGSs play a crucial role in carbon accumulation54,55. Carbon density data are calculated based on national averages, adjusted for the study area’s annual rainfall and temperature56,57, see Supplementary Material 1 for details. Total carbon storage is determined by summing the carbon densities for each land use type:

where Ctotali is the total carbon storage of land cover type I, Cabovei, Cbelowi, and Csoili represent aboveground, underground, and soil carbon storage of land cover type i, respectively.CDabovei, CDbelowi, and CDsoili represent the aboveground, underground, and soil carbon densities of land cover type i, respectively. Si is the area of land cover type i in square meters (m2). The carbon content of dead organic matter is not considered due to its negligible contribution58.

Noise reduction capacity

Vegetation barriers are effective in mitigating urban noise pollution59,60. This study employs the area-absorption capacity method, correlating different vegetation types with their respective noise reduction capabilities. Noise reduction capacity is calculated based on the area of each biotope, referencing relevant formulas from Chen et al.61.

To reflect the relationship between biotope types and ecological value, and eliminate the influence of area, the above indicators were calculated using methods such as zonal statistics and other approaches, with the average value of each grid within each biotope taken as its ability to provide ecological value. Subsequently, all ecological value indicators were normalized and combined with equal weights to obtain the overall ecological value of the study area. Similarly, the overall social value of the study area was calculated in the same way as the ecological value.

Social value

The Social Values for Ecosystem Services (SolVES) model provides a framework for assessing the social value of UGSs. This model primarily relies on raster datasets of environmental elements, vector boundary data for the study area, and field survey point data. At its core, the model employs weighted kernel density analysis based on the distribution of respondents’ perceptions regarding the social value of each biotope62,63,64. By analyzing the kernel density surface values of the social value indices, the model explores the relationship between social values and environmental factors, facilitating the visualization of the spatial distribution of social value65.

The reliability of the SolVES model is evaluated using the Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve (AUC), where an AUC value closer to 1 indicates a more accurate and reliable assessment. Conversely, an AUC value of ≤ 0.70 suggests that the model’s performance is suboptimal24,66.

This study aims to synergistically enhance both ecological and social functions to improve human well-being. Accordingly, the social value of UGSs is defined as the experiential functional value related to human use, intentionally excluding considerations such as social equity. Drawing from existing research and the specific characteristics of the study area, six relevant types of social values were identified for evaluation by respondents67,68. To ensure clarity, the definitions of these social values were tailored for better understanding by the respondents (Table 2).

Field survey point data were collected through a questionnaire (see Supplementary Material 2 for details) that comprised the following main components: (1) Personal information of the respondents, including age, gender, education level, and whether they are local residents. (2) The selection of 1–3 points on a map that respondents believe best represent locations exhibiting each type of social value. All participants provided written informed consent to participate in this study, and they were informed about the purpose of the study, the procedures involved, and their right to withdraw at any time. All experiments in this study were conducted in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations and were approved by the Ethics Committee of the College of Landscape Architecture and Arts, Northwest A&F University.

After completing the field survey, it is essential to filter the objective environmental factors. Previous studies have identified several commonly used environmental variables, including digital elevation model (DEM), slope, distance to roads, distance to water bodies, and land cover67,69,70,71,72,73.

In this study, given the focus on UGSs, traditional land cover classifications alone are insufficient to effectively represent the distinctions between biotopes. Consequently, additional factors that better reflect the characteristics of UGSs, such as fractional vegetation cover (FVC) were incorporated. Additionally, considering the socio-economic context, distances to transportation facilities and public amenities were included. Among the newly integrated environmental factors, FVC serves as a crucial indicator of vegetation cover and growth status, while the distances to transportation and public facilities provide insights into location accessibility and usage preferences.

The final selection of environmental factors comprises: DEM, FVC, slope, distance to roads, distance to water bodies, distance to transportation facilities, and distance to public amenities.

Spatial layout and coupling coordination analysis of ecological and social values

This study employs the coupling coordination degree model to illustrate the interdependence and mutual constraints between ecological and social values74,75. This model serves as a valuable tool for assessing the overall level of balanced development within the study area76.

After calculating the ecological and social values, the coupling coordination degree was calculated for each biotope using the following formulas:

where, D represents the coupling coordination degree of ecological and social values, C is the coupling degree, Xe and Xs are the calculated results of ecological and social value, respectively, T is the comprehensive coordination index, \(\alpha\) and \(\beta\) are undetermined weights. Given the equal importance of ecological and social values in UGSs, we set \(\alpha\)=\(\beta\)=0.5.

Subsequently, spatial layout analyses will be conducted for the obtained ecological values, social values, and coupling coordination degrees. First, Moran’s I will be employed to assess spatial autocorrelation, determining whether spatial clustering exists77. Next, the Getis-Ord Gi* index will be utilized for hotspot analysis to identify areas of high-value clusters (hot spots) and low-value clusters (cold spots), thereby clarifying the locations of spatial clustering78. During hotspot analysis, confidence intervals of 90%, 95%, and 99% are used to define meaningful clusters.

Influencing factors of coupling coordination relationship between ecological and social Values

This study employs the Geodetector model to explore the factors influencing the spatial heterogeneity of the coupling coordination relationship between ecological and social values of UGSs. The Geodetector is a well-established statistical method79,80 that detects the consistency between the spatial distribution patterns of the dependent variable and independent variables. It measures the explanatory power of independent variables on the dependent variable81.

The factor detector within the Geodetector framework determines the explanatory degree of each influencing factor, measured by the q-value. A higher q-value indicates a greater impact of the influencing factor on the spatial distribution of the coupling coordination relationship. The calculation formula is given as follows:

where, q represents the explanatory power of each influencing factor, L is the number of samples for the influencing factor, h denotes the classification of the variable or influencing factor, Nh and N represent the number of units in classification h and the total area, respectively; \({\sigma }_{h}^{2}\) and \({\sigma }^{2}\) are the variance of classification h and the total area, respectively.

In selecting influencing factors, secondary processed factors—such as noise reduction capacity, carbon storage, and oxygen release (calculated based on biotope categories and canopy density)—were excluded. Based on relevant literature, a total of 11 influencing factors were ultimately selected for analysis, including:

-

(1)

Ecological Factors: NDVI, arbor layer species diversity, canopy density, distance to water, and biotope category.

-

(2)

Physical Attribute Factors: DEM, slope, and abiotic coverage rate.

-

(3)

Socio-Economic Factors: Distance to roads, distance to public facilities, and distance to transportation facilities.

Each influencing factor was discretized using the natural breaks method. At the same time, the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) index was calculated. When the VIF is less than 5, it indicates that there is no multicollinearity or high correlation issue among the factors82,83.

Framework overview

The framework for evaluating the coordination relationship between ecological and social values of UGSs is illustrated in Fig. 2. This study is organized into five stages:

-

(1)

Biotope Mapping: Identification and classification of various biotopes within the study area based on vegetation structure and land cover.

-

(2)

Ecological Value Assessment: Evaluation of the ecological value of UGSs, considering factors such as plant growth, carbon sequestration, and hydrological regulation.

-

(3)

Social Value Assessment: Analysis of the social values associated with UGSs, focusing on human experiences and preferences as gathered through surveys.

-

(4)

Analysis of the Coupled Coordination Relationship: Examination of the interactions between ecological and social values to assess their mutual influence and overall coordination.

-

(5)

Analysis of Influencing Factors: Investigation of the factors affecting the coupling coordination degree between ecological and social values, utilizing statistical models to identify significant influences.

Result

Biotope mapping

A biotope map of urban green spaces (UGSs) in Xi’an was developed using field survey data and high-resolution remote sensing imagery (Fig. 3). The study identified 28 distinct biotope types. Green spaces accounted for 2.89 km2 (79.97% of the study area) across 1,027 patches. Closed green spaces, mainly those with hardscape surfaces, comprised the largest proportion, occupying 1.59 km2 across 606 patches. Grey and blue spaces covered 0.41 km2 (11.31%) and 0.32 km2 (8.72%), respectively (Table 3).

Biotope map of UGSs in Xi’an. The map created using ArcGIS software (v10.5, Esri, https://www.esri.com/).

Blue spaces were predominantly concentrated around the moat of City Ring Park, while large green patches were primarily found in City Ring Park, Lianhu Park, and Revolution Park. Grey spaces were typically embedded within green areas, such as plazas.

Ecological value of biotopes

The ecological value of UGSs in Xi’an was classified into five levels: extremly low (1.945%), low (26.525%), intermediate (43.018%), high (22.693%), and extremly high (5.819%) (Fig. 4). The overall ecological value score of the UGSs in historical core was 0.509, indicating it’s a intermediate level of ecological function. Spatially, a “high periphery, low center” pattern emerged, with high-value zones located mainly in City Ring Park. In contrast, low-value areas were found near roadsides and in the Bell Tower vicinity, often corresponding to closed green spaces with high hardscapes proportions. Medium-value areas were scattered across street greenery and residential green patches.

Ecological value of biotopes.The map created using ArcGIS software (v10.5, Esri, https://www.esri.com/).

Spatial autocorrelation analysis revealed significant clustering (Moran’s I = 0.137, Z = 8.208), with ecological hotspots around City Ring Park, Revolution Park, Lianhu Park, and the provincial government compound. Cold spots were concentrated near the Bell Tower and Hanguang Gate (Fig. 5).

Ecological value hotspot analysis. The map created using ArcGIS software (v10.5, Esri, https://www.esri.com/).

Biotope-level analysis (excluding types with fewer than 20 samples) revealed significant differences in ecological value (H = 557.107, p < 0.001). Pairwise comparisons with Bonferroni correction (Fig. 6) showed that green spaces had significantly higher ecological value than grey and blue spaces, while the difference between grey and blue spaces was not statistically significant. Biotopes such as partly closed multi-layer mixed forest primarily covered by ground cover (G PC He B & Co L-2), the closed one-layer broad-leaved forest primarily covered by ground cover (G C He B L-1), the closed one-layer mixed forest primarily covered by ground cover (G C He B & Co L-1), the closed multi-layer broad-leaved forest primarily covered by ground cover (G C He B L-2), and the closed multi-layer mixed forest primarily covered by ground cover (G C He B & Co L-2) showed the highest ecological values. In contrast, grey spaces dominated by broad-leaved trees with an abiotic coverage ratio of 75%-90% (H H2 T B), squares (H H3 S), and rivers (W R) were identified as having low ecological value.

Social value of biotopes

Out of 210 distributed questionnaires, 202 valid responses were collected (response rate: 96.19%). Demographically, respondents were slightly male-dominant (59.41%). Age distribution was relatively balanced across youth (18.81%), middle-aged (22.28%), older adults (29.21%), and elderly (29.70%). Educational levels ranged from secondary to postgraduate degrees. (Fig. 7).

Model validation indicated high reliability, with AUC values exceeding 0.85 across all six social value dimensions. Nearest neighbor analysis confirmed spatial clustering for all social values (R < 1, Z highly negative), see Supplementary Material 1 for details.

The spatial distribution of composite social value (Fig. 8) showed that 66.092% of the area had extremly low values, followed by low (15.000%), intermediate (16.500%), high (2.376%), and extremly high (0.036%) levels. The overall average social value score was 0.186, indicating an extremly low level. Social value followed a clearer "high periphery, low center" trend, with elevated values in City Ring Park and four other major parks.

Social value of biotopes. The map created using ArcGIS software (v10.5, Esri, https://www.esri.com/).

Significant clustering of social value was observed (Moran’s I = 0.598, Z = 35.605), with hot spots in City Ring Park and other key parks, and cold spots around the Shaanxi Provincial Government and street tree areas (Fig. 9).

Social value hotspot analysis. The map created using ArcGIS software (v10.5, Esri, https://www.esri.com/).

Further analysis (H = 279.133, p < 0.001) and Bonferroni pairwise comparisons (Fig. 10) showed that open green spaces with herbaceous vegetation (G O He) had the highest social value. Conversely, the closed multi-layer broad-leaved forests primarily covered by hardscape (G C Ha B L-2) had significantly lower values.

Coupling Coordination of Ecological and Social Values

The coupling coordination model revealed five categories: extreme disorder (11.764%), primary disorder (25.229%), on the verge of disorder (34.968%), primary coordination (21.685%), and excellent coordination (6.355%). The overall coupling coordination degree was 0.467, suggesting the system is on the verge of disorder and requires improvement.

The spatial pattern also followed a "high periphery, low center" structure (Fig. 11). Extreme disorder areas were concentrated in the east and southwest, particularly in street tree belts and residential green spaces. Primary coordination was seen in City Ring Park, while Revolution and Lianhu Parks achieved excellent coordination. Clustering was statistically significant (Moran’s I = 0.581, Z = 34.560), with hot spots in City Ring Park and cold spots in the southeastern and southwestern sectors (Fig. 12).

Coupling coordination degree of biotopes. The map created using ArcGIS software (v10.5, Esri, https://www.esri.com/).

Coupling coordination degree hotspot analysis. The map created using ArcGIS software (v10.5, Esri, https://www.esri.com/).

Statistical tests confirmed significant differences in coordination levels among biotopes (H = 250.394, p < 0.001). Open green spaces with herbaceous vegetation (G O He) exhibited significantly higher coordination (classified as primary coordination), while closed one-layer broad-leaved forests primarily covered by hardscape (G C Ha B L-1) and closed multi-layer broad-leaved forests primarily covered by hardscape (G C Ha B L-2) showed significantly lower coordination, falling into the primary disorder category (Fig. 13).

Influencing factors of coupling coordination degree

Using the factor detector of the Geodetector, 11 variables were found to significantly influence the coupling coordination degree (p < 0.05), with all VIF values below 5, confirming no multicollinearity (Table 4). Arbor layer species diversity and distance to water were the most influential, followed by FVC, distance to roads, biotope category, NDVI, abiotic coverage rate, DEM, distance to transportation facilities, distance to public facilities and slope. This indicates that ecological factors are the primary drivers, while spatial accessibility variables also contribute.

Interaction detection further revealed that all two-factor combinations increased explanatory power compared to individual factors. The interaction between FVC and distance to water had the highest explanatory strength, followed closely by the combination of arbor layer species diversity and distance to water (Fig. 14). These findings underscore the dominant role of vegetation structure and spatial layout in determining eco-social coordination.

Discussion

Using biotopes as research units

This study advances previous research by integrating biotope mapping theory into the classification and assessment of urban green spaces (UGSs), incorporating vegetation structure to distinguish biotope types. Two key rationales support this approach.

First, while biotope mapping has traditionally been applied in biodiversity conservation38,37, its utility for assessing ecological and social values and their coupling coordination has been underexplored. Since different vegetation structures yield varied ecological and social benefits, an in-depth understanding of specific biotope contributions is essential.

Second, most existing research focuses on large parks or scenic zones, which limits actionable insights. In contrast, this study demonstrates that different biotopes exhibit unique characteristics and distinct value patterns, greatly influencing eco-social coordination. By integrating biotope theory with value assessment models, our framework enables targeted identification of UGSs requiring renovation.

As more countries develop ecological base maps through biotic surveys27,84, this study bridges biotope mapping with urban planning strategies. This integration provides scientific support and practical recommendations for UGS classification, policy formulation, and site-specific improvements, promoting sustainable planning and community well-being.

In conclusion, the use of biotope mapping as a framework for assessing UGSs represents a significant advancement in understanding the ecological and social dynamics of UGSs. This approach has far-reaching implications for promoting sustainable urban development, enhancing community resilience, and optimizing the ecological and social contributions of urban environments. Future research should continue to explore and refine this framework, deepening our insights into the complex interactions between ecological and social values across diverse urban contexts.

Differences between biotope categories

The analysis reveals distinct differences in ecological and social values among various biotope categories within the study area. Overall, green spaces significantly outperform grey and blue spaces in terms of ecological value, with blue spaces slightly exceeding grey spaces. Notably, the social value of grey spaces has increased substantially, nearly matching that of green spaces. This underscores the indispensable roles that grey spaces play in urban transportation, social interactions, environmental management, and aesthetic enhancement.

However, it is essential to highlight that closed green spaces primarily composed of hardscape exhibit the lowest social value among green spaces. This limitation likely arises from their predominant use of street trees, which have traditionally been selected based on ecological criteria85,86 without sufficient consideration of public preferences87. Consequently, these spaces demonstrate poor coupling coordination due to their low social value relative to their ecological value. In contrast, these green spaces and certain grey spaces show no significant differences in coupling coordination, suggesting that while closed green spaces primarily covered by hardscape may lack social engagement, they nonetheless play a vital role as street tree spaces88,89. Therefore, strategies aimed at optimizing these biotopes are essential.

Focusing on other types of green spaces, the ecological value across different biotope categories shows only minor variations. While a few closed green spaces with one-layer mixed forests primarily covered by ground cover (G C He B & Co L-1) demonstrate exceptionally high ecological value, this highlights the untapped ecological potential of such biotopes. Conversely, open green spaces with herbaceous vegetation (G O He) provide the highest social value, indicating a community preference for spaces that offer moderate openness. This preference likely stems from the restrictive nature of highly enclosed spaces. Relevant studies90 have also shown that urban green open spaces play a crucial role in promoting physical activity, especially among women and the elderly, thereby enhancing public health in China.

For the grey spaces in the urban green areas of Xi’an, there are no significant differences in the ecological value, social value, and coupling coordination degree between squares (H H3 S) and the grey spaces of broad-leaved trees with an abiotic coverage rate of 75%-90% (H H2 T B). This indicates that when the abiotic area is too high, a small number of broad-leaved trees cannot significantly enhance the ecological value of the space. From the perspective of social value, squares (H H3 S) outperform the grey spaces of broad-leaved trees with an abiotic coverage rate of 75%-90% (H H2 T B). This may be closely related to the functional attributes of the squares in the study area. The squares in the study area mainly include public sports venues in park green spaces, such as badminton courts, table tennis courts, and children’s playgrounds, which can more effectively meet the social and recreational needs of the citizens, thereby enhancing their social value. This, in turn, indirectly leads to the ecological-social value coupling coordination degree of the squares being superior to that of the grey spaces of broad-leaved trees with an abiotic coverage rate of 75%-90%.

From the perspective of spatial distribution, biotopes in urban park green spaces, due to their excellent vegetation cover and ecological environment, are often able to provide higher ecological and social values. Additionally, biotopes with a coupling coordination degree of “primary coordination” or above are typically concentrated in well-planned and well-maintained park green spaces, such as Ring City Park, Revolution Park and Lian Hu Park. This result is consistent with previous studies. Chen et al.91 found that the carbon density in the tree layer of park green spaces is significantly higher than that in affiliated green spaces and square green spaces.

In summary, the variations in ecological value, social value, and coupling coordination degree among different biotope categories highlight the necessity of studying specific biotopes. This emphasizes the importance of biotope classification for informed urban planning. Consequently, targeted improvements or transformations of UGSs can be effectively approached through the enhancement or modification of biotope categories.

Recommendations for UGSs planning and development

As urbanization accelerates, UGSs face increasing challenges related to ecological protection and the fulfillment of resident needs92. Addressing how to foster ecological civilization and enhance public well-being through planning and transformation of UGSs is a pressing issue for cities. This study proposes several strategic recommendations from both urban management and localized renovation perspectives:

Participatory approach to UGS planning

The findings indicate that socioeconomic factors, such as the geographical positioning of UGSs (e.g., proximity to water and transport routes) and their connections to surrounding facilities, significantly influence the coupling of ecological and social values. National territorial spatial planning serves as a critical framework for urban development, facilitating rational spatial layouts and regional planning that align with the functional characteristics of various spaces93. Clear guidance on the structure, function, and spatial arrangement of UGSs should be embedded within territorial spatial planning. Structurally, biotope theory should guide the establishment of classification standards for UGS structures. Functionally, decisions regarding the construction, renovation, or removal of UGSs should be informed by their designated functions and corresponding biotope categories. Spatially, it is vital to integrate UGS planning with housing and infrastructure developments, ensuring the construction and enhancement of UGSs in newly developed residential areas, regions with rising housing densities, and core urban renewal zones.

Regional balance of functional values

From a regional perspective, existing developed areas should aim to enhance their ecological or social value based on specific local contexts. In urban ecological residential zones, the ecological value of green spaces should take precedence, primarily addressing essential social needs. Conversely, in densely populated core residential areas, green spaces should not only provide ecological and cultural services8,94 but also maximize social value. Specific types of green spaces should be prioritized based on their intended functional roles. Efforts must also be made to achieve an even distribution of ecological and social values, thereby maximizing the functional potential of UGSs. This approach will create a spatial layout characterized by “balanced regional ecological coverage and conveniently accessible social functions,” promoting the coordinated development of ecological and social values.

Targeted strategies for biotope development

Enhancing Ecological Value: Green spaces can significantly improve biodiversity by diversifying plant species and increasing the complexity of vegetation structures, thereby bolstering their ecological value95. Upgrading closed green spaces dominated by hardscapes can be achieved without altering their designated functions through two strategies: (1) introducing permeable pavements or connecting existing tree pits to form strip grasslands, enhancing hydrological regulation96; and (2) planting understory trees or shrubs to enrich vegetation complexity and ecological value95. In instances where planting is challenging, initiatives like the “ForestaMi” project can serve as references, utilizing mobile forests to increase biodiversity in such areas.

Enhancing Social Value: Closed green spaces primarily covered by hardscapes often exhibit low social value. However, studies suggest that modifications addressing residents’ emotional and practical needs can enhance social value97. This may include adding seating along pedestrian pathways, establishing rest facilities, or planting aesthetically pleasing species such as cherry blossoms or ginkgo trees to create scenic routes98. For other biotopes, a wider variety of activities and amenities should be provided, including fitness equipment, running tracks, public art installations, and educational plant signage.

These strategies are broadly applicable to UGSs. By instituting specialized planning aimed at optimizing the ecological and social values of UGSs through territorial spatial planning and employing urban residential divisions as a framework, the structure and geographical layout of UGSs can be improved. This method will guide the construction and renewal of UGSs, enhance the coupling between ecological and social values, and ultimately foster ecological civilization while improving public well-being.

Using Xi’an as a case study, the following adjustments should be made to urban land use in the city: Align with the latest territorial spatial planning and the specific UGS and open space strategies released by the Xi’an Municipal People’s Government99. Establish classification standards for UGSs and set development goals that prioritize ecological quality while enriching social and cultural experiences. Spatially, efforts should focus on enhancing ecological value in the southern and southeastern regions within the city walls and the northeastern areas of the City Ring Park. Concurrently, social value should be bolstered in the southern, eastern, and southeastern regions inside the city walls, with specific renovation plans aligned with the strategies outlined above.

Conversely, the trade-off between enhancing eco-social values is also a key issue in urban planning. On one hand, prioritizing ecological value by increasing vegetation cover to improve air quality and thermal comfort brings environmental and public health benefits. However, this may reduce the open space available for recreation, activities, social gatherings, or sports. On the other hand, prioritizing social functions by creating large open areas for activities or recreation may limit the ability of UGSs to serve ecological functions.

To address this trade-off, a biotope perspective can be used for optimization. Based on biotope mapping, large UGSs can be finely divided into different zones. This allows UGSs to create multiple spatial types within limited areas, meeting both ecological and social needs. Meanwhile, the detailed division system of biotope enables decision-makers to carry out targeted improvements in smaller areas, enhancing the flexibility of the space.

Additionally, participatory planning can be applied to address the trade-off. Involving local community residents in the design of UGSs ensures that both eco-social values are considered. Furthermore, adaptive management strategies can help monitor, adjust and optimize the use and management of UGSs, continuously improving and adapting to changing needs.

Limitations and future prospects

This study assessed the social value of UGSs using the SolVES model, but certain limitations must be acknowledged. Although the SolVES model provides quantitative and spatially explicit indicators that reflect stakeholders’ preferences, addressing some of the shortcomings associated with economic methods challenges remain69. Despite using smart electronic devices to assess remote sensing images and record spatial coordinate information, which enhances the accuracy of our findings, difficulties persist. In large study areas, residents may struggle to recall all UGSs within a short time frame, leading them to record only the most memorable spaces, which may not accurately represent their overall valuation. This limitation can potentially distort our experimental results.

Additionally, our analysis focused solely on the ecological and social values of UGSs within the city of Xi’an. However, perceptions of UGSs may vary significantly between residents in urban centers and those in suburban areas100. This suggests the necessity for more comprehensive studies that encompass a broader range of contexts.

Most importantly, this research emphasizes the current state of UGSs. However, the spatiotemporal evolution of land use and regional vegetation can lead to fluctuations in the ecological and social values of these ecosystems101,102,103. Therefore, future research should investigate the changes in ecological and social values of UGSs and their coupling coordination relationships over time. Such studies will provide more accurate recommendations for the maintenance and renovation of UGSs, ensuring they meet the evolving needs of urban communities.

Conclusion

This study developed an assessment system for evaluating the coupling and coordination relationship between the ecological and social values of UGSs using biotope mapping theory. By incorporating vegetation structure to classify UGS types, this approach provides valuable insights into the relationship between ecological and social values across different biotope categories.

The study identified 28 biotope types in the old city of Xi’an, covering 2.89 km2 of green spaces, 0.41 km2 of grey spaces, and 0.32 km2 of blue spaces. A consistent pattern of “high outside, low inside” was observed for ecological value, social value, and coupling coordination in spatial distribution, with an overall coordination degree of 0.467, indicating being on the verge of disorder .

Among the biotopes, the ecological value of the partly closed multi-layer mixed forest primarily covered by ground cover (G PC He B & Co L-2), the closed one-layer broad-leaved forest primarily covered by ground cover (G C He B L-1), the closed one-layer mixed forest primarily covered by ground cover (G C He B & Co L-1), the closed multi-layer broad-leaved forest primarily covered by ground cover (G C He B L-2), and the closed multi-layer mixed forest primarily covered by ground cover (G C He B & Co L-2) is significantly higher than that of other biotope types. Besides that, open green spaces dominated by grass (G O He) exhibit significantly higher social value and coupling coordination than the other biotope types.These findings underscore the significant influence of ecological factors on the coupling coordination of biotopes.This study systematically evaluates the relationship between ecological and social values in UGSs, identifies areas needing renovation, and provides targeted improvement plans. The insights gained can guide the construction and renewal of UGSs, promoting ecological sustainability and enhancing public well-being.

The study provides a practical reference for UGS transformation and planning, enabling targeted enhancements based on biotope categories. Future work should focus on tracking temporal dynamics to improve long-term adaptability and planning precision.

Data availability

The datasets used and analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Grimm, N. B. et al. Global Change and the Ecology of Cities. Science 319(5864), 756–760. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1150195 (2008).

Chen, C., Bi, L. & Zhu, K. Study on Spatial-Temporal Change of Urban Green Space in Yangtze River Economic Belt and Its Driving Mechanism. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18(23), 12498. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182312498 (2021).

Bi, Y., Wang, Y., Yang, D., Mao, J. & Wei, Q. Urban green spaces and resident health: An empirical analysis from data across 30 provinces in China. Front. Public Health 12, 1425338. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2024.1425338 (2024).

Cetin, M. Using GIS analysis to assess urban green space in terms of accessibility: Case study in Kutahya. Int. J. Sust. Dev. World 22(5), 420–424. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504509.2015.1061066 (2015).

Aronson, M. F. J. et al. Biodiversity in the city: Key challenges for urban green space management. Front. Ecol. Environ. 15(4), 189–196. https://doi.org/10.1002/fee.1480 (2017).

Jiang, Y., Liu, Y., Sun, Y. & Li, X. Distribution of CO2 Concentration and Its Spatial Influencing Indices in Urban Park Green Space. Forests 14(7), 1396. https://doi.org/10.3390/f14071396 (2023).

Wan, J. & Zhao, Z. Analysis of Landscape Pattern Change and Ecosystem Service Value of Urban Green Space—Taking Beidaihe District as an Example. Fresenius Environ. Bull. 29(7), 5382–5389 (2020).

Huang, R. et al. Social Value of Urban Green Space Based on Visitors’ Perceptions: The Case of the Summer Palace, Beijing China. Forests 14(11), 2192. https://doi.org/10.3390/f14112192 (2023).

Liang, H., Gao, T., Dong, S., & Qiu, L. Lake Wetland Park in Xianyang City Perceptions of Plant Diversity and Recreational Preferences in Small West. Landscape Architecture Academic Journal. 39(11), 51–59. (In Chinese with an English abstract). https://www.gardenmagazine.cn/ylzz/article/pdf/20221107 (2022).

Dearborn, D. C. & Kark, S. Motivations for Conserving Urban Biodiversity. Conserv. Biol. 24(2), 432–440. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1523-1739.2009.01328.x (2010).

Sarah, P. & Zhevelev, H. M. Effect of visitors’ pressure on soil and vegetation in several different micro-environments in urban parks in Tel Aviv. Landsc. Urban Plan. 83(4), 284–293. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2007.05.001 (2007).

Sandstro¨m, U. Green Infrastructure Planning in Urban Sweden. Planning Practice and Research, 17, 373–385. https://doi.org/10.1080/02697450216356 (2002).

Divinski, I., Becker, N., & Bar (Kutiel), P. Opportunity costs of alternative management options in a protected nature park: The case of Ramat Hanadiv, Israel. Land Use Policy, 71, 494–504. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2017.11.015 (2018).

Han, L., Zhang, R., Wang, J. & Cao, S.-J. Spatial synergistic effect of urban green space ecosystem on air pollution and heat island effect. Urban Climate 55, 101940. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.uclim.2024.101940 (2024).

Li, F., Li, M. & Feng, X. Ecological Benefit Analysis of Urban Green Space Based on Three-Dimensional Green Quantity. J. Indian Soc. Remote Sens. 50(11), 2267–2276. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12524-022-01603-x (2022).

Wu, S., Yao, X., Qu, Y. & Chen, Y. Ecological Benefits and Plant Landscape Creation in Urban Parks: A Study of Nanhu Park, Hefei. China. Sustainability 15(24), 16553. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152416553 (2023).

Xu, H. & Zhao, G. Assessing the Value of Urban Green Infrastructure Ecosystem Services for High-Density Urban Management and Development: Case from the Capital Core Area of Beijing China. Sustain. 13(21), 12115. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132112115 (2021).

Zeng, H. et al. Butterfly taxonomic and functional diversity in the UGSs of Hefei city. J. Forestry Res. 35(1), 55. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11676-024-01704-y (2024).

Zhu, C., Ji, P. & Li, S. Effects of urban green belts on the air temperature, humidity and air quality. J. Environ. Eng. Landsc. Manag. 25(1), 39–55. https://doi.org/10.3846/16486897.2016.1194276 (2017).

Wang, R., Zhang, Y., Zhang, H., & Yu, H. Social Value Assessment and Spatial Expression of National Park Ecosystems Based on Residents’ Perceptions. Sustainability, 14(7), Article 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14074206 (2022).

Sherrouse, B. C., Semmens, D. J. & Clement, J. M. An application of Social Values for Ecosystem Services (SolVES) to three national forests in Colorado and Wyoming. Ecol. Ind. 36, 68–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2013.07.008 (2014).

Shi, X. et al. Creating a monetization-SolVES model to visualize the cultural ecosystem services for promoting landscape conservation. J. Nat. Conserv. 77, 126521 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnc.2023.126521 (2024).

Sun, F., Xiang, J., Tao, Y., Tong, C. & Che, Y. Mapping the social values for ecosystem services in urban green spaces: Integrating a visitor-employed photography method into SolVES. Urban Forestry Urban Greening 38, 105–113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2018.11.012 (2019).

Chen, Y., Ke, X., Min, M. & Cheng, P. Disparity in Perceptions of Social Values for Ecosystem Services of Urban Green Space: A Case Study in the East Lake Scenic Area Wuhan. Frontiers Public Health 8, 370. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2020.00370 (2020).

Yan, G. A. O. et al. Assessment of social value of ecosystem services based on SolVES model and visitor’s preference: A case study of Taibai Mountain National Forest Park. Chin. J. Ecol. 36(12), 3564 (2017).

Gao T., Qiu L., Chen C. Development and Application of Biotope Mapping in Nature Conservation and Urban-rural Planning in Foreign Countries. Journal of Natural Resources, 25(6): 978–989. (In Chinese with an English abstract). https://doi.org/10.11849/zrzyxb.2010.06.010 (2010).

Bozkurt, S. G., Akkemik, U. & Kose, N. Determining the effect of urbanization on the vegetation of Gurun district (Sivas) based on biotope mapping and vegetation analysis. Forestist 70(1), 8–18. https://doi.org/10.5152/forestist.2020.19023 (2020).

Campagnaro, T. et al. General, stress relief and perceived safety preferences for green spaces in the historic city of Padua (Italy). Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 52, 126695 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2020.126695 (2020).

Olivero-Lora, S., Rojas-Sandoval, J., Meléndez-Ackerman, E. J. & Orengo-Rolón, J. L. Hurricane driven changes in vegetation structure and ecosystem services in tropical urban yards: A study case in San Juan. Puerto Rico. Urban Ecosystems 25(5), 1431–1444. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11252-022-01236-5 (2022).

Arzberger, S., Egerer, M., Suda, M. & Annighöfer, P. Thermal regulation potential of urban green spaces in a changing climate: Winter insights. Urban Forestry Urban Greening 100, 128488.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2024.128488 (2024).

Niu, X. et al. Understanding vegetation structures in green spaces to regulate atmospheric particulate matter and negative air ions. Atmos. Pollut. Res. 13(9), 101534 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apr.2022.101534 (2022).

Mao, Q., Hu, C., Guo, Q., Li, Y., & Liu, M. How Does Vegetation Landscape Structure of Urban Green Spaces Affect Cultural Ecosystem Services at Multiscale: Based on PLS-SEM Model. Forests, 14(7), Article 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/f14071401 (2023).

Pang, B., Zhao, J., Zhang, J. & Yang, L. Calculating optimal scale of urban green space in Xi’an China. Ecol. Indicators https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2023.110003 (2023).

Wang, X. et al. Spatiotemporal Dynamics of Urban Parks and Their Driving Forces in Xi’an, China from 1949 to 2015. Open House Inter. 42(3), 112–115. https://doi.org/10.1108/OHI-03-2017-B0023 (2017).

Zhang, T., Huang, R., Yang, M., Lin, G., Ma, X., Wang, X., & Huang, Q. Perceptions of the health risk from hot days and the cooling effect of urban green spaces: A case study in Xi’an, China. Front. Public Health, https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1211164 (2023).

Wang, J., Liu, N., Zou, J., Guo, Y., & Chen, H. The health perception of urban green spaces and its emotional impact on young adults: An empirical study from three cities in China. Front. Public Health, https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1232216 (2023).

Qiu, L., Gao, T., Gunnarsson, A., Hammer, M. & Von Bothmer, R. A methodological study of biotope mapping in nature conservation. Urban Forestry Urban Greening 9(2), 161–166. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2010.01.003 (2010).

Gao, T., Qiu, L., Hammer, M. & Gunnarsson, A. The Importance of Temporal and Spatial Vegetation Structure Information in Biotope Mapping Schemes: A Case Study in Helsingborg Sweden. Environ. Manag. 49(2), 459–472. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-011-9795-0 (2012).

Qiu, L., Zhu, L., Wang, J. & Gao, T. Urban biodiversity conservation planning based on biotope mapping: A case study of the urban district in Baoji China. Acta Ecol. Sin. 40(1), 170–180. https://doi.org/10.5846/stxb201811122445 (2020).

Bao, T., Li, X., Zhang, J., Zhang, Y. & Tian, S. Assessing the Distribution of Urban Green Spaces and its Anisotropic Cooling Distance on Urban Heat Island Pattern in Baotou China. ISPRS Inter. J. Geo-Information 5(2), 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi5020012 (2016).

Farinha, M. J. U. S., Berezuk, A. G., Bernardo, L. V. M., & Soares Filho, A. Assessment of Ecosystem Services Provided by a Green Urban Infrastructure in Brazilian Atlantic Forest Biome Areas – Dourados, Mato Grosso Do Sul. Sociedade & Natureza, 35, e68219. https://doi.org/10.14393/sn-v35-2023-68219 (2023).

Gong, X. & Chang, C.-C. Monetized Estimates of the Ecosystem Service Value of Urban Blue and Green Infrastructure and Analysis: A Case Study of Changsha China. Sustainability 14(23), 16092. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142316092 (2022).

Jorgensen, A., & Gobster, P. H. Shades of Green: Measuring the Ecology of Urban Green Space in the Context of Human Health and Well-Being. NATURE + CULTURE, 5(3), 338–363. https://doi.org/10.3167/nc.2010.050307 (2010).

Yu, Y. et al. The Spatial Optimization and Evaluation of the Economic, Ecological, and Social Value of Urban Green Space in Shenzhen. Sustainability 12(5), 2020. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12051844 (1844).

Guo, Y. et al. Spatial and Temporal Changes in Vegetation in the Ruoergai Region China. Forests 12(1), 76. https://doi.org/10.3390/f12010076 (2021).

Fu, K., Yao, C. The Green Plot Ratio (GPR) of Urban Parks in Wuhan. Huazhong Architecture. 38(10), 83–88. (In Chinese with an English abstract). https://link.cnki.net/doi/https://doi.org/10.13942/j.cnki.hzjz.2020.10.019 (2020).

Vockenhuber, E. A. et al. Tree diversity and environmental context predict herb species richness and cover in Germany’s largest connected deciduous forest. Perspectives Plant Ecology Evolution and Syst. 13(2), 111–119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ppees.2011.02.004 (2011).

Zhang, C., Li, W., Hu, Z., Zhu, J., & Yan, Q. Distribution pattern of tree layer species diversity based on RS and GIS: A case study of water conservation forests in montane regions of eastern Liaoning Province of China. Chinese Journal of Ecology. 28(9), 1749–1755. (In Chinese with an English abstract) https://www.cje.net.cn/CN/abstract/abstract16375.shtml (2009).

Zhan, Q., Yang, C., & Liu, H. How do greenspace landscapes affect PM2.5 exposure in Wuhan? Linking spatial-nonstationary, annual varying, and multiscale perspectives. Geo-spatial Information Science, 27(1), 95–110. https://doi.org/10.1080/10095020.2022.2085187 (2024).

Zhou, Y., & Zhou, J. The Urban Eco-environ-mental Estimating System Based on 3-dimensionVegetation Quantity. Chinese Landscape Architecture. 5, 78–80. (In Chinese with an English abstract) https://www.doc88.com/p-95327282431.html (2001).

Rai, A., Minsker, B., Sullivan, W. & Band, L. A novel computational green infrastructure design framework for hydrologic and human benefits. Environ. Model. Softw. 118, 252–261. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsoft.2019.03.016 (2019).

Gal, T., Maho, S. I., Skarbit, N. & Unger, J. Numerical modelling for analysis of the effect of different urban green spaces on urban heat load patterns in the present and in the future. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 87, 101600. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compenvurbsys.2021.101600 (2021).

Zhang, D., Xie, X. & Zhou, C. Spatial influence of exposure to green spaces on the climate comfort of urban habitats in China. Urban Climate 51, 101657. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.uclim.2023.101657 (2023).

Li, N., Deng, L., Yan, G., Cao, M. & Cui, Y. Estimation for Refined Carbon Storage of Urban Green Space and Minimum Spatial Mapping Scale in a Plain City of China. Remote Sens. 16(2), 217. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs16020217 (2024).

Wang, R.-Y. et al. Comparison of the CASA and InVEST models’ effects for estimating spatiotemporal differences in carbon storage of green spaces in megacities. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 5456. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-55858-0 (2024).

Zhang, B., Xia, Q., Dong, J., & Li, L. Research on the Impact of Land Use Change on the Spatio-temporal Pattern of Carbon Storage in Metropolitan Suburbs: Taking Huangpi District of Wuhan City as an Example. Journal of Ecology and Rural Environment. 39(6), 699–712. (In Chinese with an English abstract). http://www.ere.ac.cn/article/doi/https://doi.org/10.19741/j.issn.1673-4831.2022.0332 (2023).

Zhang, C., Xiang, Y., Fang, T., Chen, Y., & Wang, S. Spatio-Temporal Evolution and Prediction of Carbon Storage in Taiyuan Ecosystem under the Influence of LUCC. Safety and Environmental Engineering. 29(6), 248–258. (In Chinese with an English abstract). http://www.ktaq.cbpt.cnki.net/WKE/WebPublication/paperDigest.aspx?paperID=aa2022af-a197-4877-8224-e6a627b861b9 (2022).

Chuai, X., Huang, X., Lai, L., Liao, Q., Lu, J., Zhang, M., & Zheng, Z. Land Use Change and Its Influence on Carbon Storage of Terrestrial Ecosystems in Jiangsu Province. Resources Science, 2011, 33(10): 1932–1939. (In Chinese with an English abstract). https://www.resci.cn/EN/Y2011/V33/I10/1932 (2011).

Dzhambov, A. M. & Dimitrova, D. D. Urban green spaces effectiveness as a psychological buffer for the negative health impact of noise pollution: A systematic review. Noise Health 16(70), 157–165. https://doi.org/10.4103/1463-1741.134916 (2014).

Liu, L., Han, B., Tan, D., Wu, D. & Shu, C. The Value of Ecosystem Traffic Noise Reduction Service Provided by Urban Green Belts: A Case Study of Shenzhen. Land 12(4), 786. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12040786 (2023).

Chen, L., Xie, G., Gai, L., Pei, S., Zhang, C., Zhang, B., & Xiao, Y. Research on Noise Reduction Service of Road Green Spaces—A Case Study of Beijing. Journal of Natural Resources. 26(9), 1526–1534. (In Chinese with an English abstract). (2011).

Phillips, S. J., Anderson, R. P., Dudik, M., Schapire, R. E. & Blair, M. E. Opening the black box: An open-source release of Maxent. Ecography 40(7), 887–893. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecog.03049 (2017).

Phillips, S. J., Anderson, R. P. & Schapire, R. E. Maximum entropy modeling of species geographic distributions. Ecol. Model. 190(3–4), 231–259. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2005.03.026 (2006).

Sherrouse, B. C., Semmens, D. J. & Ancona, Z. H. Social Values for Ecosystem Services (SolVES): Open-source spatial modeling of cultural services. Environ. Model. Softw. 148, 105259. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsoft.2021.105259 (2022).

Zhang, H., Gao, Y., Hua, Y., Zhang, Y. & Liu, K. Assessing and mapping recreationists’ perceived social values for ecosystem services in the Qinling Mountains China. Ecosyst. Serv. 39, 101006. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoser.2019.101006 (2019).

Swets, J. A. Measuring the accuracy of diagnostic systems. Science (New York, N.Y.), 240(4857), 1285–1293. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.3287615 (1988).

Sherrouse, B. C., Clement, J. M. & Semmens, D. J. A GIS application for assessing, mapping, and quantifying the social values of ecosystem services. Appl. Geogr. 31(2), 748–760. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apgeog.2010.08.002 (2011).

Zhou, L., Guan, D., Huang, X., Yuan, X. & Zhang, M. Evaluation of the cultural ecosystem services of wetland park. Ecol. Ind. 114, 106286. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2020.106286 (2020).

Duan, H. & Xu, N. Assessing Social Values for Ecosystem Services in Rural Areas Based on the SolVES Model: A Case Study from Nanjing China.. Forests 13(11), 1877. https://doi.org/10.3390/f13111877 (2022).

Ma, Q., Chen, Z. & Zeng, M. Research on the Social Value of Urban Park Ecosystem Services Based on Population Characteristics Difference. Open J. Soc. Sci. 09, 243–258. https://doi.org/10.4236/jss.2021.912016 (2021).

Makovnikova, J., Kobza, J., Palka, B., Malis, J., Kanianska, R., & Kizekova, M. An Approach to Mapping the Potential of Cultural Agroecosystem Services. Soil and Water Research, 11(1), 44–52. https://doi.org/10.17221/109/2015-SWR (2016).

Petway, J. R., Lin, Y.-P. & Wunderlich, R. F. A Place-Based Approach to Agricultural Nonmaterial Intangible Cultural Ecosystem Service Values. Sustainability 12(2), 699. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12020699 (2020).

van Riper, C. J., Kyle, G. T., Sutton, S. G., Barnes, M. & Sherrouse, B. C. Mapping outdoor recreationists’ perceived social values for ecosystem services at Hinchinbrook Island National Park Australia. Appl. Geogr. 35(1), 164–173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apgeog.2012.06.008 (2012).

Wang, Z., Yu, Y. & Zhou, R. A longitudinal exploration of the spatiotemporal coupling relationship and driving factors between regional urban development and ecological quality of green space. Ecol. Ind. 164, 112134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2024.112134 (2024).

Zhao, W., Shi, P., Wan, Y. & Yao, Y. Coupling and Coordination Relationship between Urbanization Quality and Ecosystem Services in the Upper Yellow River: A Case Study of the Lanzhou-Xining Urban Agglomeration China. Land 12(5), 1085. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12051085 (2023).

Tu, D., Cai, Y. & Liu, M. Coupling coordination analysis and spatiotemporal heterogeneity between ecosystem services and new-type urbanization: A case study of the Yangtze River Economic Belt in China. Ecol. Ind. 154, 110535. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2023.110535 (2023).

Huo, X.-N., Li, H., Sun, D.-F., Zhou, L.-D. & Li, B.-G. Combining Geostatistics with Moran’s I Analysis for Mapping Soil Heavy Metals in Beijing, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 9(3), 995–1017. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph9030995 (2012).

Feng, Y., Cui, L., Chen, X. & Liu, Y. A comparative study of spatially clustered distribution of jumbo flying squid (Dosidicus gigas) offshore Peru. J. Ocean Univ. China 16(3), 490–500. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11802-017-3214-y (2017).

Peng, L., Sun, Y., Zhan, Z., Shi, W. & Zhang, M. FR-weighted GeoDetector for landslide susceptibility and driving factors analysis. Geomat. Nat. Haz. Risk 14(1), 2205001. https://doi.org/10.1080/19475705.2023.2205001 (2023).

Yang, J. et al. New method for landslide susceptibility mapping supported by spatial logistic regression and GeoDetector: A case study of Duwen Highway Basin, Sichuan Province China. Geomorphology 324, 62–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geomorph.2018.09.019 (2019).

Wang, J., & Xu, C. Geodetector: Principle and prospective. Acta Geographica Sinica. 72(1), 116–134. (In Chinese with an English abstract). https://www.geog.com.cn/CN/https://doi.org/10.11821/dlxb201701010 (2017).

Kim, J. H. Multicollinearity and misleading statistical results. Korean J. Anesthesiol. 72(6), 558–569. https://doi.org/10.4097/kja.19087 (2019).

Kyriazos, T. & Poga, M. Dealing with Multicollinearity in Factor Analysis: The Problem, Detections, and Solutions. Open J. Stat. 13(03), 404–424. https://doi.org/10.4236/ojs.2023.133020 (2023).

Kim, T. & Kim, G. Biotope Map Creation Method and Utilization Plan for Eco-Friendly Urban Development. Land 13(5), 699. https://doi.org/10.3390/land13050699 (2024).

Dangulla, M., Abd Manaf, L., Ramli, M. F. & Yacob, M. R. Urban tree composition, diversity and structural characteristics in North-western Nigeria. Urban Forestry Urban Greening 48, 126512. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2019.126512 (2020).

Silvera Seamans, G. Mainstreaming the environmental benefits of street trees. Urban Forestry Urban Greening 12(1), 2–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2012.08.004 (2013).

Kim, S. S., Lee, J.-S., Lee, D. H., & Choi, Y. Citizens’ Preference and Perception of Street Trees of Main Boulevards in Busan, South Korea. Sustainability, 13(6), Article 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13063141 (2021).

Hu, Y. et al. Alternative scenarios for urban tree surveys: Investigating the species, structures, and diversities of street trees using street view imagery. Sci. Total Environ. 895, 165157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.165157 (2023).

Yang, J., Zhou, J., Ke, Y. & Xiao, J. Assessing the structure and stability of street trees in Lhasa China. Urban Forestry Urban Greening 11(4), 432–438. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2012.07.002 (2012).

Wang, H., Dai, X., Wu, J., Wu, X. & Nie, X. Influence of urban green open space on residents’ physical activity in China. BMC Public Health 19(1), 1093. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-7416-7 (2019).

Chen Yongchong, Shi Zhengjun, Zeng Wei, Yuan Fengjun, Wang Yujia, Zeng Chang. Estimation and Distribution Characteristics of Carbon Density in the Arbor Layer of Urban Green Spaces in Shenzhen’s Built Area. Journal of Chinese Urban Forestry, 2024, 22(4): 43–50. (In Chinese with an English abstract). https://doi.org/10.12169/zgcsly.2024.04.19.0002 (2024).

Luo, X., Luan, W., Li, Y. & Xiong, T. Coupling coordination analysis of urbanization and the ecological environment based on urban functional zones. Front. Public Health 11, 1111044. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1111044 (2023).

Zhang, Y., Man, X. & Zhang, Y. From, “Division” to “Integration”: Evolution and Reform of China’s Spatial Planning System. Buildings 13(6), 1555. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings13061555 (2023).

Piaggio, M. The value of public UGSs: Measuring the effects of proximity to and size of UGSs on housing market values in San Jose. Costa Rica. Land Use Policy 109, 105656. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2021.105656 (2021).

Gao, T., Hedblom, M., Emilsson, T. & Nielsen, A. B. The role of forest stand structure as biodiversity indicator. For. Ecol. Manage. 330, 82–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2014.07.007 (2014).

Kia, A., Delens, J. M., Wong, H. S. & Cheeseman, C. R. Structural and hydrological design of permeable concrete pavements. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 15, e00564. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cscm.2021.e00564 (2021).

Lee, B. J., Jang, T. Y., Wang, W. & Namgung, M. Design Criteria for an Urban Sidewalk Landscape Considering Emotional Perception. J. Urban Plann. Devel. 135(4), 133–140. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)UP.1943-5444.0000013 (2009).

Qin, X., Cui, S. & Liu, S. Linking Ecology and Service Function in Scenic Road Landscape Planning: A Spatial Analysis Approach. J. Test. Eval. 46(4), 1297–1312. https://doi.org/10.1520/JTE20170451 (2018).

Xi’an Municipal People’s Government. Xi’an Municipal Bureau of Natural Resources and Planning (Xi’an Municipal Forestry Bureau). Report title: Announcement of the Public Display of the Draft of the "Xi’an Territorial Spatial Master Plan (2021–2035)". Retrieved from http://zygh.xa.gov.cn/web_files/zygh/file/2022/11/08/202211081852155156437.pdf (2022).

Arnberger, A. & Eder, R. The influence of green space on community attachment of urban and suburban residents. Urban Forestry Urban Greening 11(1), 41–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2011.11.003 (2012).

Bian, Z. & Lu, Q. Ecological effects analysis of land use change in coal mining area based on ecosystem service valuing: A case study in Jiawang. Environ. Earth Sci. 68(6), 1619–1630. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12665-012-1855-0 (2013).

Han, W., Chen, D., Li, H., Chang, Z., Chen, J., Ye, L., Liu, S., & Wang, Z. Spatiotemporal Variation of NDVI in Anhui Province from 2001 to 2019 and Its Response to Climatic Factors. Forests, 13(10), Article 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/f13101643 (2022).

Yuan, K., Li, F., Yang, H., & Wang, Y. The Influence of Land Use Change on Ecosystem Service Value in Shangzhou District. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(8), Article 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16081321 (2019).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China [grant numbers: 31971720, 31971722]; the Science and Technology Innovation Program of Shaanxi Academy of Forestry [grant numbers: SXLK2021-0216]; the Research on the Key Technology of Building Strong Carbon Sink Grassland in Guanzhong Area of Shaanxi Province [grant number SXLK2023–02–18].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.S.: Writing -review & editing, Writing—original draft, Visualization, Validation, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. W.W.: Visualization, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation. C.W.: Investigation, Visualization. X.W.: Investigation. D.Y.: Investigation. H.L.: Data curation, Investigation. D.G.: Investigation. L.Q.: Writing -review & editing, Validation, Supervision, Project administration, funding acquisition. T.G.: Writing -review & editing, Supervision, Resources, Project administration, Funding acquisition.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sun, Y., Wang, W., Wang, C. et al. Synergies and trade offs of ecological and social values across different biotopes in urban green spaces: a case study of Xi’an, China. Sci Rep 15, 33835 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-04255-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-04255-2