Abstract

During the El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO), heat wave variations off the High Andean Puna (HAP) cause extreme droughts at high altitudes. A better understanding of the drought susceptibility of HAP Polylepis xeric-species is needed given the increasing frequency of desiccation and tree mortality. We evaluated the tree ring growth and vessel trait plasticity to ENSO intensities (neutral, weak, moderate, and strong) of two Polylepis xeric-species (Polylepis rugulosa and Polylepis tarapacana). We demonstrated annual ring width and vessel trait differences between La Niña and El Niño events for both species. We showed that specific vessel traits exhibit coordination with water-use efficiency in response to ENSO events, thereby reducing vulnerability to hydraulic failure. When assessing the effects of ENSO events on specific vessel traits, special attention should be paid to traits that confer resilience, resistance, and recovery to growth of these species. This knowledge is essential to suggest that this adjustment to ENSO events may increase their capacity to tolerate and adapt to new extreme climatic conditions in the HAPs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Andes are known for their complex climatic patterns, owing to their exceptional topographical features, including high peaks and steep slopes1. Orography and climate are considered key drivers of biodiversity hotspots throughout South America2. These ecosystems are highly vulnerable to climate change and hydric stress3,4. As most High Andean Puna (HAP5) species are acclimated to specific isolated mountain zones, small changes in climate can lead to serious losses of species6,7. A better understanding of the desiccation susceptibility of HAP tree species is needed given the increasing frequency of hydric stress and tree mortality caused by prolonged drought periods6,8. During El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO; El Niño and La Niña phenomena9,10), heat wave oscillations off the coasts of Ecuador and Peru cause torrential rainfall in coastal deserts. Nonetheless, HAP forests above ≈3800 m a.s.l. typically do not experience this ENSO-related moisture influx11,12; whereas La Niña tends to drive cooler and wetter conditions throughout the Andes13.

Recent evidence suggests that wood anatomical adjustments are key to understanding the response of hydraulic architecture to extreme climatic events in terms of hydric safety and efficiency14,15. The HAP Polylepis species occur at high elevations ranging from 3000 to 5000 m a. s. l.16. Polylepis wood is mainly characterized by narrow vessels randomly distributed throughout the growth ring7,17. This vessel distribution provides efficient hydraulic conductivity early in the growing season, as large vessels in earlywood provide how environmental factors affect vessel formation and size7,18,19,20,21. Variation in vessel traits among species can significantly impact habitat preferences, species niche differentiation, and distribution along moisture gradients1,22. For example, vessel traits such as tangential diameter, vessel density, and hydraulic diameter, are strongly linked to ecohydrological functions that allow plants to adjust to hydric stress23,24. The acclimation capacity of HAP tree species to varying soil water conditions is facilitated by their high plasticity in hydraulic-related xylem traits. This enables them to disperse into different xeric habitats and track environmental changes.

Vessel traits are key to hydric plasticity in HAP plant communities. Here, we studied the link between vessel traits and climate in Polylepis species, which is hypothesized to explain vessel trait-acclimation to ENSO events (El Niño and La Niña7,25). Drought-resistant tree species are found in xeric valleys, protecting Peru’s HAP forests from short-term hydric stress. This study investigated the influence of ENSO events, as determined by the plasticity of the wood anatomy of Peruvian Polylepis species (Polylepis rugulosa Bitter and P. tarapacana Phil.). Therefore, the specific aims of this study were to (1) explore Polylepis’ tree-ring growth response to local climatic conditions (i.e., evapotranspiration, precipitation, and temperature); (2) evaluate the effect of ENSO intensities (neutral, weak, moderate, and strong) on vessel traits (tangential diameter, vulnerability index, and hydraulic diameter) for each Polylepis species; and (3) examine how local climatic conditions influence the vessel traits of Polylepis species.

Results

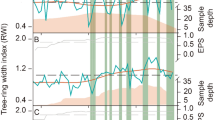

Tree-ring width chronology

The independent residual dendrochronological statistics confirmed the accuracy of the tree-ring chronology analysis (Fig. 1; Table 1). The series of intercorrelations between individuals were high at each site (number of intercorrelations: Polylepis rugulosa = 1770; and P. tarapacana = 1891; Table 1). The expressed population signal (EPS) was above the widely used threshold of 0.85 for all individual chronologies (≥ 0.91; Table 1). The higher mean correlation coefficient among tree-ring series (R-bar values; Table 1) exhibited an accurate measure of the chronology signal (Polylepis rugulosa = 0.282; P. tarapacana = 0.473; Table 1).

Ring-width chronologies: Polylepis rugulosa (A) and P. tarapacana (B). The arrows represent specific ENSO events [El Niño (1958, 1963, 1991 and 1993), and La Niña (1955, 1961, 1975 and 1984)]. The gray area represents the number of series in the chronology. Statistical features are shown by the running Expressed Population Signal (EPS) where the horizontal dashed line shows the 0.85 EPS threshold, and the sample depth through time for each chronology.

Climatic influence on tree-ring width

Our analysis revealed differences in climatic factors that could strongly correlate in influence the intra-annual monthly growth of Polylepis species. Evapotranspiration (EvT) showed a negative correlation (r = − 0.226) from September to October of the previous growing season in Polylepis rugulosa (Fig. 2A), whereas P. tarapacana demonstrated a significant negative correlation (r = − 0.285) in August, although it exhibited a significant positive correlation (r = 0.254) in February of the current growing season (Fig. 2A).

Local correlation between RWI Polylepis and gridded CRU TS 4.0.6. The climatic variables evapotranspiration (A), precipitation (B), maximum temperature (C), mean temperature (D), and minimum temperature (E) had a common period from 1960 to 2015 for each species. The horizontal dotted line represents 95% confidence intervals.

For P. rugulosa, precipitation (Prcp) displayed a significant positive correlation in June (r = 0.223) and February (r = 0.206) during the current growing season, whereas in P. tarapacana, the Prcp from December to January of the previous growing season had a positive correlation (r = 0.292), whereas the Prcp from February to March of the current growing season showed a negative correlation (r = − 0.323; Fig. 2B).

The maximum temperature (Tmax) in P. rugulosa exhibited a negative correlation (r = − 0.19) in March of the current growing season (Fig. 2C); nevertheless, Tmean and Tmin (Fig. 2D,E) correlated in the two growing seasons for P. rugulosa. In P. tarapacana, Tmax was negatively correlated (r = − 0.278) from June to October but positively correlated (r = 0.307) from December to March of the current growing season (Fig. 2C). The Tmean from June to April of the previous growing season showed negative (r = − 0.274) and positive (r = 0.285) correlations from October to May in the current growing season (Fig. 2D). The Tmin from October to April during the previous growing season was negatively correlated (r = − 0.279), while from September to May of the current growing season showed a positive correlation (r = 0.236) (Fig. 2E).

Xylem vessel trait acclimation

A total of 16,521 vessels were measured directly from the selected digital images of wood cores (4452 from Polylepis rugulosa, and 12,069 for P. tarapacana). The vessel traits (DT, VI, and DH) were influenced by specific ENSO intensities (Fig. 3). During the neutral La Niña events, the DT fluctuated from 10 to 100 μm for Polylepis rugulosa and from 8 to 90 μm for P. tarapacana; during the weak La Niña event, the DT ranged from 5 to 35 μm for P. rugulosa and from 9 to 20 μm for P. tarapacana; during the moderate La Niña event, the DT ranged from 3 to 30 μm for P. rugulosa and from 2 to 18 μm for P. tarapacana; and during the strong La Niña event, the DT ranged from 10 to 120 μm for P. rugulosa but from 8 to 10 μm for P. tarapacana (Fig. 3A). The VI values during neutral, weak, and moderate La Niña events differed in vessel architecture plasticity for both species (P. rugulosa ranged from 1 to 11, and P. tarapacana ranged from 1 to 6). During strong events, the VI ranged from 1 to 7 for P. rugulosa and from 0.5 to 1 for P. tarapacana (Fig. 3B). The DH values for P. rugulosa were wider during neutral (1–55 μm), weak (1–20 μm), moderate (1–30 μm), and strong (10–120 μm) events, whereas P. tarapacana was highly plastic during neutral (5–45 μm), weak (10–20 μm), moderate, and strong (5–20 μm) events (Fig. 3C).

During neutral El Niño events, the DT ranged from 10 to 30 μm for P. rugulosa and 10 to 90 μm for P. tarapacana. DT during weak and moderate events was highly plastic in P. rugulosa (15–150 μm) and P. tarapacana (15–70 μm). Finally, no significant differences in DT were found between species during moderate events (10–30 μm) (Fig. 3D). The VI during neutral and strong events showed no significant differences between species (ranging from 1 to 5); nevertheless, P. rugulosa showed VI values from 1 to 25, whereas P. tarapacana ranged from 1 to 3. During moderate events, the VI of P. tarapacana was greater (from 1 to 15) than that of P. rugulosa (from 1 to 4) (Fig. 3E). Finally, during neutral events, the DH values ranged from 1 to 10 μm for P. rugulosa and from 1 to 80 μm for P. tarapacana; nonetheless, no significant differences in the DH values were found between the species during weak and moderate events (ranging from ≈2 to 150 μm) or strong events (from ≈2 to 10 μm) between species (Fig. 3B).

Influence of ENSO events on vessel architecture traits

In exploratory canonical correspondence analysis (CCA), climatic factors and vessel traits exhibited a moderate relationship across ENSO intensities between species. La Niña events indicated that Axis 1 (eigenvalue = 0.412) and Axis 2 (eigenvalue = 0.147) showed canonical correlations of 0.556 and 0.379, respectively (Fig. 4A). During El Niño events, Axis 1 (eigenvalue = 0.643) and Axis 2 (eigenvalue = 0.394) exhibited canonical correlations of 0.799 and 0.579, correspondingly (Fig. 4B). La Niña event demonstrated that P. tarapacana was more influenced by Prcp and EvT, whereas P. rugulosa was determined by Tmin and Tmax. Conversely, during El Niño event, P. rugulosa was influenced by EvT and Tmin, while P. tarapacana was shaped by Tmean and Tmin.

Ordination plot of RWI and vessel traits (brown triangles) and climatic factors (green and blue vectors) in P. rugulosa (red circles) and P. tarapacana (black circles) species sampling units. La Niña events (A); and El Niño events (B). Species code: R = P. rugulosa, T = P. tarapacana. ENSO intensity code: n = neutral, w = weak, m = moderate; and s = strong.

Conversely, during La Niña event, no discernible impact on DH from any climate variable was detected. Similarly, DT was marginally affected by EvT, while VI was influenced by Prcp and Tmin. Finally, RWI was negatively shaped by Tmin. In the context of El Niño event, Tmean and Tmin influenced on DT and DH, whereas VI and RWI are determined by Prcp and Tmin. It is noteworthy that the vessel traits were situated at the center of the coordinates. To ascertain the impact of climatic variables on vessel traits, we employed GLMM and fourth-corner analysis.

In correlation analysis, throughout all La Niña events, DT and DH were positively correlated with Prcp, Tmax and Tmean; whereas VI for EvT, Tmax and Tmean; while RWI with Tmin in P. rugulosa (Fig. 5A). Nonetheless, for P. tarapacana, DT, VI, and DH were negatively correlated with Prcp, EvT, Tmax, Tmin and Tmean, respectively; and RWI was positively correlated with Prcp (Fig. 5B). During El Niño events, we found that DT was positively correlated with EvT and Tmin; VI with Prcp, EvT, Tmax, Tmin, Tmean, whereas DH with Tmin, Prcp and EvT, and RWI were positively correlated with Tmin, Prcp for P. rugulosa (Fig. 5C). Finally, for P. tarapacana, DT, VI and DH were positively correlated with Prcp and Tmin; while RWI was positively correlated for Prcp (Fig. 5D) (Supplementary Table 1).

Pearson correlation and average model coefficients that influence wood anatomical traits; best models that were statistically significant (p < 0.05) between La Niña and El Niño events for each Polylepis species. (A and E) P. rugulosa vs La Niña; (B and F) P. tarapacana vs La Niña; (C and G) and P. rugulosa vs El Niño; (D and H) P. tarapacana vs El Niño. (A, B, C, and D) = Pearson correlation graphs. (E, F, G, and H) = Average model coefficient graphs. Asterisks represent significant correlations (p < 0.05).

Overall, across all La Niña intensities (neutral, weak, moderate, and strong), we observed that the DH, DT and VI were influenced by Tmin, Tmean and Tmax and RWI by Tmin for P. rugulosa (Fig. 5E). Furthermore, the DH of P. tarapacana was determined by Tmax; nonetheless, Tmax and Tmin significantly influenced the DH, VI and DT (Fig. 5F). During El Niño (neutral, weak, moderate, and strong), the RWI, DH, VI and DT were affected by Tmax, Tmin and Tmean; moreover, DH and VI were influenced by EvT for P. rugulosa (Fig. 5G). Finally, for P. tarapacana, DH, VI and DT were significantly influenced by Tmax, Tmin and Tmean for DT, and Tmean was affected by DH (Fig. 5H) (Supplementary Table 2).

GLMM and fourth-corner analyses revealed that climatic factors distinctly influenced vessel traits at different ENSO intensities (neutral, weak, moderate, and strong). In La Niña events for P. rugulosa, DT was significantly influenced by Tmax (β = − 0.026, p = 0.041) and Prcp (β = − 0.001, p = 0.039), whereas DH was influenced by Tmean (β = − 0.105, p = 0.041) at neutral intensities. In addition, the RWI was affected by Tmean (β = − 1.137, p = 0.043) and Tmax (β = 1.696, p = 0.045) only at high intensities and by Prcp at weak (β = 0.003, p = 0.040), moderate (β = − 0.005, p = 0.047), and strong (β = 0.003, p = 0.035) intensities (Supplementary Table 3).

For P. tarapacana, we observed that DT was influenced by Tmean (β = 0.009, p = 0.001), Tmax (β = − 0.014, p = 0.001) and Prcp (β = 0.001, p = 0.001); likewise, DH showed that Tmean (β = 0.035, p = 0.024) and Tmax (β = − 0.032, p = 0.025) were significantly affected at neutral intensities. VI demonstrated that Tmean (β = 3.201, p = 0.014), Tmax (β = 0.683, p = 0.016) and Prcp (β = − 0.001, p = 0.047) together determined the best model at moderate intensities, and Prcp (β = − 0.002, p = 0.039) and Tmean (β = − 1.650, p = 0.027) determined the best model for RWI in P. tarapacana during strong events (Supplementary Table 3).

During moderate El Niño events, the DT, DH and VI of P. rugulosa were influenced by Tmean (β = − 0.004, p = 0.039; β = − 0.090, p = 0.047; β = − 1.136, p = 0.016; respectively), whereas the RWI was shaped by Tmin (β = − 3.113, p = 0.044), Tmean (β = − 1.978, p = 0.047) and EVT (β = − 0.004, p = 0.020). Furthermore, during strong intensities, the DH values exhibited a significant effect on Tmin (β = − 0.102, p = 0.034), and RWI with Tmax. (β = − 0.781, p = 0.043). For P. tarapacana, DT was affected by Tmin (β = 0.029, p = 0.0102) and Tmax (β = − 0.046, p = 0.011) only at strong intensities and was influenced at weak and strong intensities by Prcp (β = 0.001, p = 0.039; β = − 0.001, p = 0.010; respectively).

In addition, we observed that DH was influenced by Tmean (β = 0.075, p = 0.034) only at weak intensities, while weak and strong intensities by Tmax (β = − 0.006, p = 0.037; β = − 0.038, p = 0.034; respectively) and Prcp (β = 0.001, p = 0.028; β = 0.001, p = 0.041; respectively). In contrast, the VI was influenced weak and moderate intensities by Tmean (β = 1.700, p = 0.020; β = − 0.757, p = 0.044; respectively), Tmax (β = − 1.583, p = 0.021; β = 0.499, p = 0.038; respectively) and Prcp (β = 0.001, p = 0.025; β = 0.001, p = 0.046; respectively); nevertheless, Tmin (β = -2.180, p = 0.044) was affected only by strong intensities. Finally, in neutral intensities for RWI were affected by Tmin (β = − 0.491, p = 0.038), Tmean (β = 1.025, p = 0.042) and Prcp (β = 0.002, p = 0.038), while strong intensities Tmin (β = − 1.226, p = 0.022), Tmax (β = 5.076, p = 0.015), and EvT (β = − 2.959, p = 0.013) significantly influenced the RWI (Supplementary Table 3).

Discussion

In the Andes, local climate patterns, such as ENSO events, have a variety of effects on HAP range26, triggering eco-wood climate adaptation1. ENSO events imply a decrease in precipitation or increase in temperature in the Andes25,27, which could lead to the ecophysiological and vessel trait-acclimation of Polylepis28,29.

Our results showed that the statistics traditionally used in tree-ring studies confirmed the quality of our chronologies. The mean sensitivity (MS > 0.30) for both chronologies showed not only high intra-annual variation in the annual rings but also high EPS values for each chronology. These data indicate a common growth signal among the trees, thus indicating a good representation of the population of ring chronologies. The high EPS values recorded were previously documented in other Polylepis species from the HAP (Bolivia, Peru, Chile, Ecuador, and Argentina)25,30.

Successful cross-dating of the ring-width patterns of P. rugulosa and P. tarapacana demonstrated that annual rings developed and that a common climatic factor strongly influenced ring development in these HAP tree xeric-species. Overall, the Polylepis species tended to have similar growth patterns12,31; however, the growth of both species exhibited different correlations with EvT, Prcp, Tmax, Tmean, and Tmin. Warmer and drier conditions directly influence ecophysiological adjustment, as shown for the current growing season of P. tarapacana25. The correlation between P. tarapacana growth and rainfall is inverse, but it does not always demonstrate a negative impact. Trees exhibit physiological resilience that allow them to respond quickly to high temperatures, including water availability32,33. Additionally, trees can develop stress memory capacity as an acclimation strategy when faced with conditions that limit their growth during drought periods. Following a period of initial stress, the plants were able to recover when the conditions improved. Notwithstanding, when future hydric stress episodes occur, the initial stress leaves a lasting imprint on the plant, altering its response to subsequent stress episodes34,35.

In addition, the growth of P. rugulosa is weakly related to climatic signals, most likely to specific ecohydric plasticity and genetic variation among trees36, which could increase the ability of plants to reshape their growth. Previous studies based on physiological analyses of P. rugulosa and P. tarapacana demonstrated that cold and drought conditions during the dry season can trigger a period of inactivity in the vascular cambium and that frozen plant tissues can take a long time to thaw before metabolic activity resumes37,38. The low climatic signal for growth rings (i.e., P. rugulosa) may be due to better physiological adjustments (e.g., vitrification during desiccation processes), biochemical, and eco-wood adjustment39,40. This can be linked to surviving xeric conditions and could influence hydric stress tolerance to severe local and global climatic events41,42.

The importance of ENSO oscillations in tree-ring width variation in Peruvian tree species has long been recognized12,25,27. The assessment of how La Niña and El Niño events influence vessel trait plasticity and water availability effect is relatively new.1,12,12,27,38,43,44,45,46,47Nevertheless, specific Polylepis xeric-species directly adjust functional and structural tree-ring characteristics that allow them to be climate resilient to pre-disturbance growth rates7,43. Furthermore, cooler, and wetter conditions during La Niña events are not always more severe in denser stands because of greater environmental stress. Our findings demonstrate that during La Niña events, RWIs from Polylepis species provide additional evidence of the specific effects of climate variation. Interestingly, dividing La Niña events into four intensities (neutral, weak, moderate, and strong) resulted in specific RWI variations in the study species. In this context, the present study provides new relevant data on the wood-plastic responses of two xeric Polylepis species to local ENSO fluctuations. The observed differences in vessel hydraulic architecture between species have important ecological implications, as they suggest specific wood-anatomical plasticity reflected as a differential hydraulic functional reduction in vessel traits during El Niño compared with La Niña. Although each of the Polylepis species responded differently to ENSO events, this could be observed in the vessel traits that decreased during El Niño events, suggesting a greater restriction of hydric stress compared to the vessel traits that developed during La Niña. Cooler environmental conditions (during La Niña events) influence on the vessel architecture related to hydraulic efficiency (e.g., VI and DH48) and increase the vessel acclimation linked to hydraulic safety (e.g., DT). Narrower vessels suggest high acclimation of xylem tissue to hydric stress to avoid embolism or cavitation49. The xylem architecture can be hydraulically regulated by specific climatic factors48,50.

This shows that both Polylepis species can thrive under suboptimal soil conditions even in the moisture zones of its range27. Nevertheless, the assessment of ENSO events on tree-ring anatomical features in high Andean species has received recent attention30,51, which helps us understand how drought triggers a growth ring response52. Our results showed that the vessel traits of two Polylepis species with similar xeric environments exhibited different ENSO wood anatomical effects. Temperature had strong effects on vessel architecture for both Polylepis species during strong ENSO intensities. This may be because temperature is a limiting factor in maintaining hydraulic safety20, thereby maximizing wood plasticity of the two species to extreme temperatures, implying greater drought53.

Nonetheless, during ENSO events, the Prcp and EvT rates were minimal in the two study forests, indicating that the climate of these high Andean forests is influenced by high radiation and aridity54. This may have directly influenced the ecophysiological strategy of using dew water to maintain hydraulic efficiency41,55. Our results showed that the ring width of both species was affected during strong ENSO events, modifying the hydraulic architecture to maintain greater hydric safety during extreme climatic events. This is reflected in the semiring or ring porosity of both Polylepis species, as water limitation reduces the hydric security of the narrow vessels of latewood, compromising the xylem hydrological system during periods of drought48. Such a wood-anatomical risk-taking ecological strategy results in trees that are well acclimated to hydric stress over long periods46, making them less vulnerable to recurrent ENSO stress. Nevertheless, rapid recovery after a stress event may influence the long-term eco-wood adjustment of Polylepis forests.

Methods

Andean Puna mountain study areas

This study was conducted at two Peruvian APM forests (Tarata locality, Tacna district; 17°26′5’’S, 69°57′49’’W; 4200 m a.s.l.; and Paucarani volcano, 17°34′22’’S, 69°45′42’’W; 4700 m a.s.l., Supplementary Fig. S1A). These monospecific Polylepis forests display heights of trees from 1 to 5 m, as they are located at high elevations (> 4000 m a.s.l). These sites experience cold arid climates (BWk56) characterized by high daily temperature amplitudes, a cool dry season from late April to early November, and a wet cool season from late December to late March (Supplementary Fig. S1B). The mean annual temperature ranges from 2.6 to 6 °C, and the annual precipitation ranges from 180 to 210 mm, with volcanic rock slopes > 20°. The soils at these sites are Leptosol-Lithic outcrops (LPd-ANz57).

Sample collection and chronology development

We randomly sampled 30 Polylepis rugulosa trees from Tarata and 30 P. tarapacana trees from Paucarani volcano. Tree species were identified by T. Boza using specific monograph of the genus Polylepis7,17 and the vascular plant species nomenclature was updated at the Tropicos website (Missouri Botanical Garden; http://www.tropicos.org). The specimens were deposited in the Selva Central Oxapampa Herbaria-(HOXA), Missouri Botanical Garden, Oxapampa, Pasco, Peru. Plant collection code numbers are not available for the specimens used in this study. The samples were collected under the regulations of Servicio Nacional Forestal y de Fauna Silvestre (SERFOR) from Peru, Resolution 037-2017-SERFOR/DGGSPFFS.

We collected two cross-sections from the basal stem per tree (about 1.3 m), because they are multi-stemmed. A total of 31 (for P. rugulosa) and 62 (for P. tarapacana) cross-sections were collected using a chainsaw (Notch™ Standard Chainsaw Chaps, Forestry Suppliers). The cross-sections were dried at room temperature (≈1 week) and polished with eight successive coarse grits (80, 120, 180, 220, 240, 320, 420, and 600) and five finer grits (800, 1000, 1200, 1500, and 2000) until the annual rings were visible (Supplementary Fig. S2)58. The tree ring series were dated by assigning calendar years according to the Schulman Conversion for the Southern Hemisphere59. The ring widths were measured using a stereoscopic microscope (OMAX®) and a Velmex Tree-Ring Measuring System (Velmex, Inc., Bloomfield, NY, USA) with an accuracy of 0.001 mm. Possible measurement problems (false and/or missing rings) and cross-correlations between individual tree-ring series were verified using COFECHA software60. COFECHA software calculates Pearson correlations (r) in 50-year segments with a 25-year overlap with the following segment at a 99% significance level61.

To obtain residual ring-width indices (RWIs) that preserve the high-frequency signal62, we standardized the raw ring-width data by fitting an exponential curve for each individual RWI series to remove autocorrelation and ontogeny effects using the software R v.4.0.5 with the dplR package63. We assessed the quality of the chronology using the expressed population signal (EPS > 0.8564) as a measure of the total signal present in the chronology and the mean correlation coefficient among the tree-ring series (R-bar65). Wood core samples were preserved according to Speer66 and deposited at Dendrochronology Lab, Universidad Continental, Huancayo, Peru.

ENSO event identification, cross-sections and tree-ring digitalization

We categorized historical annual ENSO events (El Niño and La Niña for 3.4 SST data27) into neutral, weak, moderate, and strong intensities (Supplementary Table 4) according to the Oceanic Niño Index (ONI) classification67,68.

We measured 200 previously cross-dated tree rings from each Polylepis species (MS > 0.2; sensitive tree-ring series66). The measurements were based on wood quality, series length, and correlation with the master chronology. We used a stereoscopic microscope equipped with a digital camera (Leica DFC 490, Leica Microsystems, Guadalajara, Mexico) (Supplementary Fig. 2). The historical annual ENSO years were identified for each tree-ring in the digital images. Consecutive droughts were considered independent. The area containing tree-ring widths before, during, and after each ENSO event ranged between two wood rays (an average of 0.21 mm width × 0.62 mm length). Each digital cross-sectional image was acquired using a stereoscopic microscope with a field between 12.9 and 50.3 µm. Images were captured using a digital camera and saved in TIFF format with a 1.3 μm per pixel resolution7.

Climate-growth correlations

To identify the climate signal on growth69, we assessed the influence of the local climate on Polylepis growth, monthly evapotranspiration, precipitation, and temperature (maximum, minimum and average) data for a common period (from 1960 to 2015) obtained from the nearest Climatic Research Unit grid cell (CRU TS 4.0.6; https://climexp.knmi.nl/). We analyzed the relationships between the Polylepis RWI and climatic variables using Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r) with the corrplot R package70. To determine whether growth is influenced by several months prior to ring formation, climate-growth relationships were examined over a 24-month period from June of the previous growing season to May of the current growing season71. Climatic conditions for two complete growing seasons (previous and current) were considered by integrating these months25,44,52,72,73.

Vessel trait measurements

To assess the effects of ENSO events (La Niña and El Niño) on specific vessel traits (tangential diameter, DT; vulnerability index, VI; and hydraulic diameter, DH; see Supplementary Table 5), we selected five previously cross-dated cores from each Polylepis species (200 tree rings for each species). Each ENSO event was categorized into neutral, weak, moderate, and strong intensities (40 tree rings per cross section). Likewise, the vessel traits selected may provide a better understanding of the hydraulic conductivity and safety that these high-elevation forests develop in the face of drought events20,74. All vessel traits (DT, VI, and DH) were quantified and measured in specific growth rings that developed two years before, during, and two years after each ENSO event using ImageJ software75. To assess whether the values of the vessel traits displayed a notable difference between ENSO events and non-ENSO years for both species, we performed two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and post-hoc Tukey tests with vegan72 and ggplot273 R packages.

Effect of climate on vessel traits

To evaluate the effect of climate on vessel traits at each ENSO intensity (neutral, weak, moderate, and strong), we performed a canonical correspondence analysis (CCA). Matrix 1 consisted of vessel traits (DT, VI, and DH) for each Polylepis species; matrix 2 included climatic variables (EvT, Prcp, Tmax, Tmean, and Tmin). The analysis was performed using CANOCO v 5.076.

Furthermore, we assessed the climatic influence of ENSO events on Polylepis wood anatomic traits using generalized linear mixed modeling (GLMM) with gamma distributions77 and fourth-corner analysis78. For these analyses, vessel traits were considered response variables, climatic variables were considered explanatory factors (fixed effects), and ENSO-year events were considered random factors. The explanatory factors were tested for collinearity, data normality (Wilcoxon-Mann‒Whitney test), homogeneity (χ2 test), and randomization to assess whether they were statistically significant. Pearson correlation (r) was also performed to evaluate the degree of association between explanatory factors and vessel traits using corrplot70 and car79 R-packages.

For the GLMM analysis, we first fitted 28 models for each response variable and then used multimode inference to evaluate the effects and significance of each explanatory factor. Using the corrected Akaike information criterion (AICc) and Bayesian information criterion (BIC), we selected the best model for each, which was defined as having AICc = 0. The analyses were performed using lme480 and performance R packages81. Finally, for the fourth-corner analysis, we generated average model coefficients as our prediction model using the manyglm technique in the Mvabund R package82.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ENSO:

-

El Niño southern oscillation

- HAP:

-

High Andean Puna

References

Pérez-Escobar, O. A. et al. The Andes through time: Evolution and distribution of Andean floras. Trends Plant Sci. 27, 364–378 (2022).

Killeen, T. J., Douglas, M., Consiglio, T., Jørgensen, P. M. & Mejia, J. Dry spots and wet spots in the Andean hotspot. J. Biogeogr. 34, 1357–1373 (2007).

Garzione, C. N. et al. Rise of the Andes. Science 1979(320), 1304–1307 (2008).

Rahbek, C. et al. Building mountain biodiversity: Geological and evolutionary processes. Science 1979(365), 1114–1119 (2019).

Baied, C. A. & Wheeler, J. C. Evolution of high Andean puna ecosystems: Environment, climate, and culture change over the last 12 000 years in the central Andes. Mt. Res. Dev. 13, 145–156 (1993).

Peters, J. M. R. et al. Living on the edge: A continental-scale assessment of forest vulnerability to drought. Global Change Biol. 27, 3620 (2021).

Rodríguez-Ramírez, E. C., Crispín-DelaCruz, D. B., Ticse-Otarola, G. & Requena-Rojas, E. J. Assessing the hydric deficit on two Polylepis species from the Peruvian Andean mountains: Xylem vessel anatomic adjusting. Forests 13, 1–12 (2022).

Choat, B. et al. Triggers of tree mortality under drought. Nature 558, 531–539 (2018).

Garreaud, R. D. The Andes climate and weather. Adv. Geosci. 22, 3–11 (2009).

Salazar, P. C. et al. Effect of climate and ENSO events on Prosopis pallida forests along a climatic gradient. Forestry 91, 552–562 (2018).

Garreaud, R. D. & Aceituno, P. Interannual rainfall variability over the South American Altiplano. J. Clim. 14, 2779–2789 (2001).

Morales, M. S. et al. Drought increased since the mid-20th century in the northern South American Altiplano revealed by a 389-year precipitation record. Clim. Past Discuss. 1–32 (2023).

Humanes-Fuente, V. et al. Two centuries of hydroclimatic variability reconstructed from tree-ring records over the Amazonian Andes of Peru. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 125, (2020).

Fonti, P. & Jansen, S. Xylem plasticity in response to climate. New Phytol. 195, 734 (2012).

Fajardo, A., Piper, F. I. & García-Cervigón, A. I. The intraspecific relationship between wood density, vessel diameter and other traits across environmental gradients. Funct. Ecol. 36, 1585–1598 (2022).

Kessler, M. Bosques de Polylepis. Botánica Económica de los Andes Centrales 110–120 (2006).

Boza, T. & Kessler, M. A monograph of the genus Polylepis (Rosaceae). PhytoKeys 203, 1–274 (2022).

Souto-Herrero, M., Rozas, V. & García-González, I. Earlywood vessels and latewood width explain the role of climate on wood formation of Quercus pyrenaica Willd. across the Atlantic-Mediterranean boundary in NW Iberia. For. Ecol. Manage 425, 126–137 (2018).

García-González, I., Souto-Herrero, M. & Campelo, F. Ring-porosity and earlywood vessels: A review on extracting environmental information through time. IAWA J. 37, 295–314 (2016).

Lourenço, J. et al. Hydraulic tradeoffs underlie local variation in tropical forest functional diversity and sensitivity to drought. New Phytol. https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.17944 (2022).

von Arx, G., Kueffer, C. & Fonti, P. Quantifying plasticity in vessel grouping - Added value from the image analysis tool ROXAS. IAWA J. 34, 433–445 (2013).

Mosquera, G. M. et al. Science of the total environment ecohydrological assessment of the water balance of the world’s highest elevation tropical forest (Polylepis). Sci. Total Environ. 941, 173671 (2024).

Lens, F. et al. Functional xylem characteristics associated with drought-induced embolism in angiosperms. New Phytol. https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.18447 (2022).

Rodríguez-Ramírez, E. C. et al. Exploring monsoon precipitation signal in the Peruvian tropical montane cloud forest: Andean Walnut wood anatomy plasticity. IAWA J. 17, 63–81 (2023).

Crispín-DelaCruz, D. B. et al. High ENSO sensitivity in tree rings from a northern population of Polylepis tarapacana in the Peruvian Andes. Dendrochronologia 71, 125902 (2022).

Lavado-Casimiro, W. S., Felipe, O., Silvestre, E. & Bourrel, L. ENSO impact on hydrology in Peru. Adv. Geosci. 33, 33–39 (2013).

Christie, D. A. et al. El Niño-Southern Oscillation signal in the world’s highest-elevation tree-ring chronologies from the Altiplano, Central Andes. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 281, 309–319 (2009).

Valladares, F., Gianoli, E. & Gómez, J. Ecological limits to plant phenotypic plasticity. New Phytol. 176, 749–763 (2007).

Rodriguez-Morata, C. et al. Revealing Polylepis microphylla as a suitable tree species for dendrochronology and quantitative wood anatomy in the Andean montane forests. Dendrochronologia 76, 125995. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dendro.2022.125995 (2022).

Alvites, C. et al. Dendrochronological analysis and growth patterns of Polylepis reticulata (Rosaceae) in the Ecuadorian Andes. IAWA J 40, 331–351 (2019).

Requena-Rojas, E. J. et al. Temporal growth variation in high-elevation forests: Case study of Polylepis forests in Central Andes. Latin Am. Dendroecol. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-36930-9 (2020).

Buckley, M. L., Lowe, R. J., Hansen, J. E., Van Dongeren, A. R. & Storlazzi, C. D. Mechanisms of wave-driven water level variability on reef-fringed coastlines. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 123, 3811–3831 (2018).

Steppe, K., Vandegehuchte, M. W., Tognetti, R. & Mencuccini, M. Sap flow as a key trait in the understanding of plant hydraulic functioning. Tree Physiol. 35, 341–345 (2015).

Prasad, P. V. V., Djanaguiraman, M., Jagadish, S. V. K. & Ciampitti, I. A. Drought and high temperature stress and traits associated with tolerance. Sorghum: State of the Art and Future Perspectives 241–265 (2019) https://doi.org/10.2134/agronmonogr58.2014.0065.

Saatchi, S. et al. Detecting vulnerability of humid tropical forests to multiple stressors. One Earth 4, 988–1003 (2021).

Rundel, P. W. et al. Ecological and ecophysiological patterns in a pre-altiplano shrubland of the Andean Cordillera in northern Chile. Plant Ecol 169, 179–193 (2002).

Azócar, A., Rada, F. & García-Núñez, C. Functional characteristics of the arborescent genus Polylepis along a latitudinal gradient in the high Andes. Interciencia 32, 663–668 (2007).

Jomelli, V. et al. Analysis of the dendroclimatic potential of Polylepis pepei, Polylepis subsericans and Polylepis rugulosa in the tropical Andes (Peru-Bolivia). Tree Ring Res. 68, 91–103 (2012).

Zuidema, P. A., Brienen, R. J. W. & Schöngart, J. Tropical forest warming: Looking backwards for more insights. Trends Ecol. Evol. 27, 193–194 (2012).

Borghetti, M., Gentilesca, T., Leonardi, S., Van Noije, T. & Rita, A. Long-term temporal relationships between environmental conditions and xylem functional traits: A meta-analysis across a range of woody species along climatic and nitrogen deposition gradients. Tree Physiol. 37, 4–17 (2017).

Hertel, D. & Wesche, K. Tropical moist Polylepis stands at the treeline in east Bolivia: The effect of elevation on stand microclimate, above- and below-ground structure, and regeneration. Trees – Struct. Funct 22, 303–315 (2008).

Toivonen, J., Horna, V., Kessler, M., Ruokolainen, K. & Hertel, D. Interspecific variation in functional traits in relation to species climatic niche optima in Andean Polylepis (Rosaceae) tree species: Evidence for climatic adaptations. Funct. Plant Biol. 41, 301–312 (2014).

Guerra, A., Ames-Martínez, F. N. & Rodríguez-Ramírez, E. C. Wood anatomical acclimation in the endemic genus Polylepis in Peruvian Andean forests. J Mt Sci 21, 2986–3000 (2024).

Lloret, F., Keeling, E. G. & Sala, A. Components of tree resilience: Effects of successive low-growth episodes in old ponderosa pine forests. Oikos 120, 1909–1920 (2011).

Argüelles-Marrón, B. et al. Adaptation potential of Neotropical montane oaks to drought events: Wood anatomy sensitivity in Quercus delgadoana and Quercus meavei. Funct. Ecol. 37, 2040–2055 (2023).

Wojtyla, Ł., Paluch-Lubawa, E., Sobieszczuk-Nowicka, E. & Garnczarska, M. Drought stress memory and subsequent drought stress tolerance in plants. In Priming-mediated stress and cross-stress tolerance in crop plants (ed. Academic Press) 115–131 (2020).

Mu, Y., Lyu, L., Li, Y. & Fang, O. Tree-ring evidence of ecological stress memory. Proc. Royal Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 289, 20221850 (2022).

Ewers, F. W., Jacobsen, A. L. & López-Portillo, J. Carlquist’s indices for vulnerability and mesomorphy of wood: are they relevant today? IAWA J 0, 1–13 (2023).

Hacke, U. G., Sperry, J. S. & Pittermann, J. Drought Experience and Cavitation Resistance in Six Shrubs from the Great Basin, Utah Basic and Applied Ecology. Basic Appl. Ecol. 1 http://www.urbanfischer.de/journals/baecol (2000).

Rodríguez-Ramírez, E. C., Vázquez-García, J. A., Alcántara-Ayala, O. & Luna-Vega, I. Drought effects on vessel plasticity of two endemic Magnolia species in the tropical montane cloud forests of eastern Mexico. Ann. For. Sci. 34, 1. https://doi.org/10.20944/preprints201811.0282.v1 (2018).

Andreu-Hayles, L. et al. Dendrochronological advances in the tropical and subtropical Americas: Research priorities and future directions. Dendrochronologia 81, 126124 (2023).

Anderegg, W. & Meinzer, F. Wood anatomy and plant hydraulics in a changing climate. Funct. Ecol. Xylem Anatomy 1–281 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-15783-2.

Hacke, U. G., Jacobsen, A. L. & Pratt, R. B. Vessel diameter and vulnerability to drought-induced embolism: Within-tissue and across-species patterns and the issue of survivorship bias. IAWA J. 105, 1–16 (2022).

Garreaud, R., Vuille, M. & Clement, A. C. The climate of the Altiplano: Observed current conditions and mechanisms of past changes. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 194, 5–22 (2003).

García-Plazaola, J. I., Rojas, R., Christie, D. A. & Coopman, R. E. Photosynthetic responses of trees in high-elevation forests: Comparing evergreen species along an elevation gradient in the Central Andes. AoB Plants 7, (2015).

Peel, M. C., Finlayson, B. L. & McMahon, T. A. Updated world map of the Köppen–Geiger climate classification. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 11, 1633–1644 (2007).

Minam,. Mapa Nacional de Cobertura Vegetal (Peru, 2015).

Orvis, K. H. & Grissino-Mayer, H. D. Standardizing the reporting of abrasive papers used to surface tree-ring samples. Tree Ring Res. 58, 47–50 (2002).

Schulman, E. Dendroclimatic changes in semiarid America (University of Arizona Press, 1956).

Grissino-Mayer, H. D. Evaluating crossdating accuracy: A manual and tutorial for the computer program COFECHA. Tree Ring Res. 57, 205–221 (2001).

Holmes, R. L. Computer-assisted quality control in tree-ring dating and measurement. Tree-ring Bull. 43, 69–78 (1983).

Aliste Moreno, D. Desarrollo de una cronología de ancho de anillos para Fitzroya cupressoides ((Molina) Johnston) y su relación con la variabilidad climática, en la Cordillera de la Costa, sector Los Pabilos (Región de Los Lagos, 2016).

Bunn, A. G. A dendrochronology program library in R (dplR). Dendrochronologia 26, 115–124 (2008).

Briffa, K. R. & Jones, P. D. Basic dendrochronology statistics and assessment. In Methods of dendrochronology Applications in the Environmental Sciences (ed. A. Cook, E., K.) 146–152 (1990).

Wigley, T. M. L., Briffa, K. R. & Jones, P. D. On the average value of correlated time series, with applications in dendroclimatology and hydrometeorology. J. Climate Appl. Meteorol. 23, 201–213 (1984).

Speer, B. J. H. Fundamentals of tree-ring research. 509, 453 (2010) https://doi.org/10.1002/gea.20357.

Huang, B. et al. Extended reconstructed Sea surface temperature, Version 5 (ERSSTv5): Upgrades, validations, and intercomparisons. J. Clim. 30, 8179–8205 (2017).

Null, J. El Niño and La Niña Years and Intensities Based on Oceanic Niño Index (ONI). 1–2 http://ggweather.com/enso/oni.htm (2024).

Oladi, R., Emaminasab, M. & Eckstein, D. The dendroecological potential of shrubs in north Iranian semi-deserts. Dendrochronologia 44, 94–102 (2017).

Wei, T. & Simko, V. R package ‘corrplot’: Visualization of a correlation matrix. (Version 0.92). https://github.com/taiyun/corrplot (2021).

Fritts, H. Tree rings and climate (Elsevier, 2012).

Oksanen, J. et al. vegan: Community Ecology R Package, version 2.3–5. vegan: Community Ecology Package. R package version 2.4–1. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=vegan vol. 8 732–740 Preprint at https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/vegan/index.html. (2016).

Wickham, H. et al. Package ggplot2: Create elegant data visualizations using the grammar of graphics. Preprint at https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/ggplot2/index.html (2021).

Scholz, A., Klepsch, M., Karimi, Z. & Jansen, S. How to quantify conduits in wood?. Front Plant Sci. 4, 1–11 (2013).

Schneider, C. A., Rasband, W. S. & Eliceiri, K. W. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat. Methods 9, 671–675 (2012).

Šmilauer, P. & Lepš, J. Multivariate analysis of ecological data using Canoco 5 (Cambridge University Press, 2014).

Ver Hoef, J. & Boveng, P. L. Quasi-Poisson versus negative binomial regression: How should we model overdispersed count data?. Ecology 88, 2766–2772 (2007).

Brown, A. M. et al. The fourth-corner solution-using predictive models to understand how species traits interact with the environment. Methods Ecol. Evol. 5, 344–352 (2014).

Fox, J. & Weisberg, S. car: An R Companion to Applied Regression (version 3.1–2). Preprint at https://socialsciences.mcmaster.ca/jfox/Books/Companion/ (2019).

Bates, D., Mächler, M., Bolker, B. & Walker, S. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J. Stat. Softw. 67, 1–48 (2015).

Lüdecke, D. et al. Performance: Assessment of regression models performance. Preprint at (2022).

Wang, Y., Naumann, U., Wright, S. T. & Warton, D. I. Mvabund- an R package for model-based analysis of multivariate abundance data. Methods Ecol. Evol. 3, 471–474 (2012).

Acknowledgements

This work was carried out with resources from the Dendrochronology and Wood Anatomy Laboratories, Universidad Continental, Huancayo, Peru. The wood samples used in this study were partially funded by the 047-2015-Fondecyt-DE and CONICET PIP 11220130100584 project. We thank Cassiana Alves-Ferreira for wood anatomical assistance. We are grateful to Gregg Dieringer for the English style review

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AG, FN-AM, DBC-C, EOM, and ECR-R: conceptualization, methodology. AG, FN-AM, EJRR, and ECR-R: writing, review and editing. AG, EJRR: fieldwork. AG, AG, FN-AM, DBC-C, and ECR-R analysis data. ECR-R: supervision. The authors read and approved the final manuscript. AG prepared Figs. 1 and 2 FN-AM prepared Figs. 3, 4 and 5 ECR-R prepared Fig. 3 and Figure S1 All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Guerra, A., Ames-Martínez, F.N., Crispín-DelaCruz, D.B. et al. Polylepis wood acclimation strategies to ENSO events. Sci Rep 15, 19236 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-04422-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-04422-5