Abstract

Tryptophol (TOH) is an aromatic alcohol, a natural compound, which is produced by various microorganisms. TOH has been reported to have sleep-inducing effects, anti-microbial activities as well as immunoregulatory properties. While TOH was shown to suppress proinflammatory cytokine production in a variety of cell types, in vivo evidence supporting the immunosuppressive effect of TOH remains sparse. Here, we report that TOH reduced the severity of skin inflammation in a mouse model of imiquimod (IMQ)-induced psoriasis. The results revealed that the TOH-containing emulgel decreased the pathological score of the psoriasis area and severity index (PASI). Topical administration of TOH-containing emulgel inhibited keratinocyte proliferation in IMQ-treated skin as indicated by reduced immunoreactivity for Ki67 and decreased mRNA expression of K6, K16 and K17. Skin of TOH-containing emulgel-treated IMQ mice displayed fewer Giemsa-positive cells and CD4+ cells than those of emulgel-treated IMQ mice, suggesting a decreased dermal infiltration of mast cells and CD4+ T cells, respectively. RT-qPCR results showed that interleukin (IL)-17A, IL-23 and IL-33 were downregulated in psoriatic skin of TOH-containing emulgel-treated IMQ mice. Western blot analysis demonstrated that phosphorylation of JAK2 and STAT3, downstream signaling molecules of IL-17A and IL-23, was decreased in TOH-containing emulgel-treated IMQ mice. Additionally, TOH-containing emulgel dermal application alleviated IMQ-induced splenomegaly and suppressed expression of TNFα, IL-1 and IL-6 in spleen and axillary lymph nodes. This study revealed that a TOH-containing emulgel attenuates IMQ-induced inflammation in psoriatic mice and could be a new therapeutic agent for managing psoriasis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Psoriasis is a chronic inflammatory skin disease that affects approximately 2–3% of the population. Psoriasis commonly manifests as dry, itchy, erythematous, scaly plaques on the skin surface1,2,3. The manifestation of psoriasis is orchestrated by inflammatory responses that regulate keratinocyte proliferation and differentiation1,2,3. Psoriasis inflammation is driven by IL-23 cytokine produced by myeloid cells in the lesions4. IL-23 activates JAK/STAT signaling in naïve CD4+ T cell and promotes the release of IL-17, which is known to be an inducer of keratinocyte proliferation4,5,6,7. While IL-23 inhibitors and IL-17 inhibitors are now available for treating psoriasis, most of these medications have shown undesirable side effects, including increased risk of infections and inflammatory disease8. For these reasons, many efforts are attempted to identify a biologic agent that has a therapeutic effect on psoriasis9. The combined use of the natural compound with a reduced dosage of standard drugs may help maintain high treatment efficacy and diminish the probability of side effects.

Tryptophol (TOH) is a tryptophan metabolite produced by microorganisms, including those that reside in human tissue10. TOH has antimicrobial properties against several pathogenic bacteria10,11 and apoptosis-inducing effect on blood cancer cells12,13. TOH was also known to modulate immune response through the regulation of cytokine production14. A previous study reported that TOH suppressed severe inflammation in a mouse model of LPS-induced sepsis15. However, the anti-inflammatory activity of TOH in the development of other immunological disorders is yet to be reported. As tryptophan metabolites was shown to inhibit production of key cytokines in psoriasis, such as, IL-17, IL-23 and TNFα16, it is possible that TOH may reduce inflammatory response and alleviate pathological hallmarks of psoriasis. Therefore, this study aims to investigate the potential effect of this TOH-containing emulgel on IMQ-induced psoriasis in mice.

Results

The TOH-containing emulgel ameliorated psoriasis-like symptoms in IMQ-induced mice

Following daily IMQ treatment for 7 days, emulgel-treated mice developed psoriasis-like symptoms, such as skin thickening, scaling and erythema (Fig. 1a). The severity of these symptoms was assessed and displayed as the psoriasis area and severity index (PASI) score in Fig. 1b–e. Our results showed that erythema, scaling, skin thickening and cumulative PASI score were significantly decreased in TOH-containing emulgel-treated IMQ mice (IMQ + Tryptophol group) compared to those of emulgel-treated IMQ mice (IMQ + Emulgel group). We also found that TOH-containing emulgel treatment attenuated IMQ-induced weight loss during days 2–4 of the treatment (Fig. 1f).

TOH-containing emulgel ameliorates psoriasis symptoms in IMQ-induced psoriatic mice. (a) Comparison of dorsal skin lesions on the 7th day among different groups of mice. (b–e) PASI scores, including erythema (b), scaling (c), skin thickness (d), and total PASI score, of mouse dorsal skin in all groups of mice were evaluated daily (n = 8). (f) The weights of the mice in all groups were measured daily (n = 8). The data are presented as the means ± SD. Statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA. **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

The alleviation of IMQ-induced histopathology in the skin of TOH-containing emulgel treatment mice

To analyze IMQ-induced histopathology, skin sections were stained with H&E. As shown in Fig. 2a, the skins of emulgel-treated mice displayed the presence of nucleated keratinocytes in the stratum corneum (parakeratosis) and epidermal thickening, whereas both parakeratosis and epidermal thickening were noticeably improved in TOH-containing emulgel-treated IMQ mice. Quantitative measurement confirmed that epidermal thickness was significantly decreased in TOH-containing emulgel-treated IMQ mice compared with emulgel-treated IMQ mice (Fig. 2b, p < 0.001). Since the thickening of epidermis is known to be caused by increased keratinocyte proliferation3, we next examined expression of cell proliferation marker, Ki67, along with K6, K16 and K17. As expected, immunohistochemistry for Ki67 demonstrated that the epidermis of TOH-containing emulgel-treated IMQ mice had fewer Ki67-positive cells than that of emulgel-treated IMQ mice (Fig. 2c,d). in addition, RT-qPCR analysis revealed that K6, K16, and K17 were significantly reduced in the skin of TOH-containing emulgel-treated IMQ mice (Fig. 2e–g). Furthermore, the skins of TOH-containing emulgel-treated IMQ mice showed decreased expression of involucrin (Fig. 2h, p < 0.05), a structural protein which is known to mediate the formation of psoriatic plaque17.

TOH-containing emulgel alleviated epidermal hyperplasia and decreased keratinocyte differentiation in IMQ-induced psoriatic mice. (a) Representative H&E sections of the dorsal skin of the mice in all the groups. Histological analysis revealed greater severity of parakeratosis and acanthosis in the psoriatic mice treated with emulgel (IMQ + Emulgel group) than in the psoriatic mice treated with TOH-containing emulgel (IMQ + Tryptophol group). Representative images of skin sections were taken at ×10 magnification, with a scale bar of 100 μm. (b) Quantification of epidermal thickness in all groups (n = 8). (c) Representative Ki67 immunostaining of the dorsal skin of all groups of mice. Ki67+ cells are indicated by black arrows. Representative images of skin sections were taken at ×10 magnification (scale bar: 100 μm), and the inset images were taken at ×40 magnification (scale bar: 50 μm). (d) Quantification of Ki67-positive cells (n = 8). (e–h) RT-qPCR analysis of the keratinocyte differentiation markers including K6 (e), K16 (f), K17 (g), and involucrin (h) (n = 4). The data are expressed as fold changes relative to the cream base groups. All the data are presented as the means ± SD. Statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA analysis. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.001.

TOH-containing emulgel suppressed IMQ-induced cytokine production in mouse skin

Psoriasis is closely linked to overexpression of cytokines that drive inflammation and keratinocyte proliferation. We considered that the milder pathology observed in TOH-containing emulgel-treated IMQ mice may be attributed to decreased cytokine production. To investigate this possibility, we evaluated the levels of inflammatory cytokine TNFα and IL-1β using the ELISA technique. The results showed significantly lower levels of TNFα (Fig. 3a, p < 0.001) and IL-1β (Fig. 3b, p < 0.001) in TOH-containing emulgel-treated IMQ mice compared to emulgel-treated IMQ mice. Additionally, the expression of IL-17A and IL-23 was assessed in both psoriatic mice skin and blood serum. The results demonstrated that the TOH-containing emulgel-treated mice exhibited significantly decreased IL-17A level compared to the emulgel-treated IMQ mice, both in skin tissue (Fig. 3c, p < 0.01) and blood serum (Fig. 3d, p < 0.001). The expression of IL-23 showed a significant decrease in TOH-containing emulgel-treated IMQ mice compared to the emulgel-treated IMQ mice (Fig. 3e, p < 0.001) and blood serum (Fig. 3f, p < 0.001). In comparison to control mice (cream base group), normal mice treated with TOH-containing emulgel (Tryptophol group) exhibited a decrease in the expression of IL-17A in the skin (Fig. 3c, p < 0.001) as well as decreased expression of IL-23 in the skin (Fig. 3e, p < 0.001) and blood serum (Fig. 3f, p < 0.001). These findings suggested that the release of TNFα, IL-1β, IL-17A and IL-23 was significantly reduced in TOH-containing emulgel-treated IMQ mice.

TOH-containing emulgel reduced skin inflammation. ELISA was performed to evaluate the expression level of TNFα (a), IL-1β (b), IL-17A (c), and IL-23 (e) in the skin tissue (n = 5). (d and f) The expression level of IL-17A and IL-23 was measured in the blood serum (n = 5). All the data are presented as the means ± SD. Statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.001.

TOH-containing emulgel reduced mast cell infiltration and activation in the skin of IMQ mice

In the early stage of psoriasis, mast cells become activated and undergo degranulation, releasing mediators that contribute to disease progression18. Given that mast cells are known to be an important source of IL-17—a key player in the inflammatory cascade of psoriasis19—we considered that the reduced production of IL-17A observed in TOH-containing emulgel-treated IMQ mice could potentially be explained by impaired mast cell recruitment. To investigate this, we performed Giemsa staining on skin sections to assess mast cell infiltration. Our results showed that lesions of TOH-containing emulgel-treated IMQ mice contained fewer mast cells than those of emulgel-treated IMQ mice (Fig. 4a and b, p < 0.001), suggesting that TOH-containing emulgel reduced mast cells infiltration. To explore whether TOH-containing emulgel also affects mast cell activity, we next assessed expression of IL-33, a critical inducer of mast cell activation. ELISA and RT-qPCR analysis revealed that IL-33 levels were significantly reduced in the skins of TOH-containing emulgel-treated IMQ mice (Fig. 4c, p < 0.05; Fig. 4d, p < 0.001, respectively). In addition, a decreased expression of ST2, the receptor for IL-33, was noted in lesions of TOH-containing emulgel-treated IMQ mice.

TOH-containing emulgel reduced mast cell infiltration in IMQ-induced psoriatic mice. (a) Representative images of Giemsa-stained dorsal skin from all groups of mice. Representative images of skin sections were taken at ×10 magnification (scale bars: 100 μm), and inset images were taken at ×40 magnification (scale bars: 50 μm). (b) Quantification of mast cell accumulation in the dorsal skin of the mice in all the groups (n = 8). (c) The mRNA expression levels of IL-33 were measured via RT-qPCR (n = 4). (d) Cytokine expression levels of IL-33 in the dorsal skin of mice in all groups were measured using ELISA (n = 5). (e) The mRNA expression levels of ST2 were measured via RT-qPCR (n = 4). All the data are presented as the means ± SD. Statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001.

Decreased CD4+ cell recruitment in TOH-containing emulgel-treated IMQ mice

IL-17 and IL-23 play a central role in the pathogenesis of psoriasis by promoting keratinocyte proliferation and recruiting T cells to psoriatic skin20. Since these cytokines were downregulated in the skins of TOH-containing emulgel-treated IMQ mice, we next investigated whether TOH-containing emulgel could affect dermal infiltration of T cells. Immunohistochemistry for CD4 showed that the number of CD4+ cells was significantly lower in the skins of TOH-containing emulgel-treated IMQ mice, compared to that of emulgel-treated IMQ mice (Fig. 5a and b, p < 0.001). This result suggested that TOH-containing emulgel reduced the CD4+ cell recruitment into skin lesions.

TOH-containing emulgel reduced CD4+ T-cell infiltration into psoriatic mice treated with TOH-containing emulgel. (a) Representative images of immunohistochemical staining of CD4+ cells in the dorsal skin of the mice in all the groups. Representative images of skin sections were taken at ×10 and ×40 magnification (scale bars: 100 μm and 50 μm, respectively). The CD4+ cells are indicated by a black arrow. (b) Quantification of CD4+ cells in all groups (n = 5). The data are presented as the means ± SD. Statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001.

The activation of the JAK2/STAT3 pathway was inhibited in skin of TOH-containing emulgel-treated IMQ mice

IL-17 and IL-23 exert their pro-inflammatory functions through activation of the JAK/STAT signaling pathway21. It is possible that the reduction in IL-17 and IL-23 observed in TOH-containing emulgel-treated IMQ mice may influence JAK/STAT pathway activation. To test this, we analyzed the expression and phosphorylation of JAK2 and STAT3. Immunohistochemical staining of JAK2 and STAT3 showed that the number of JAK2- and STAT3-expressing cells in the epidermis of TOH-containing emulgel-treated IMQ mice was notably lower than that in emulgel-treated IMQ mice (Fig. 6a–c). RT-qPCR analysis revealed reduced JAK2 expression in the skin of TOH-containing emulgel-treated IMQ mice, while STAT3 expression remained comparable between the two groups (Fig. 6d,e). Surprisingly, the western blot results indicated that total protein levels of JAK2 and STAT3, as well as their phosphorylated form (pJAK2 and pSTAT3), were unchanged between the groups (Fig. 6f–i and Supplementary Figs. S1–S4). To further assess activation of JAK2/STAT3 pathway activation, we stained the skin sections with antibodies specific to pJAK2 and pSTAT3. The number of pJAK2-positive cells and pSTAT3-positive cells was significantly decreased in TOH-containing emulgel-treated IMQ mice (Fig. 6a, j and k), suggesting impaired activation of the JAK2/STAT3 pathway. Consistent with these findings, reduced expression of BCL2 and CCND1—target genes of the JAK/STAT pathway—was observed in the skin of TOH-containing emulgel-treated IMQ mice (Fig. 6l and6m).

The TOH-containing emulgel alleviated activation of the JAK2/STAT3 pathway in inflammation and cell proliferation. (a) Immunohistochemical staining for JAK2, pJAK2, STAT3, and pSTAT3 on the skin section of all groups was performed. Representative images of skin sections were taken at ×40 magnification (scale bars: 50 μm). (b,c) Quantification of JAK2, and STAT3 positive cells in all groups (n = 4). (d,e) The mRNA expression of JAK2 and STAT3. (f) Protein expression of JAK2, pJAK2, STAT3 and pSTAT3 evaluated by western blot. (g,h) Relative protein expression levels of pJAK2 and pSTAT3 normalized to total JAK2 and STAT3, respectively (n = 4). (j,k) Quantification of pJAK2, and pSTAT3 positive cells in all groups (n = 4). (l,m) The mRNA expression of BCL2 and CCND1 were analyzed by RT-qPCR (n = 4). The data are presented as the means ± SD. Statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001.

IMQ-induced organomegaly and cytokine expression were attenuated in the secondary lymphoid organs of TOH-containing emulgel-treated IMQ mice

To investigate whether TOH-containing emulgel could affect systemic inflammation induced by IMQ, we weighed spleens and axillary lymph nodes and measured mRNA expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines TNFα, IL-1 and IL-6 (Fig. 7). While splenic mass of TOH-containing emulgel-treated IMQ mice was significantly lower than that of emulgel-treated IMQ mice (Fig. 7a,b, p < 0.01), there was no difference in relative lymph node weight index between TOH-containing emulgel-treated and emulgel-treated IMQ mice (Fig. 7c,d). RT-qPCR analysis showed that transcripts TNFα, IL-1 and IL-6 were reduced in both spleens (Fig. 7e, p < 0.05; Fig. 7f, p < 0.001 and Fig. 7g, p < 0.001, respectively) and lymph nodes (Fig. 7h, p < 0.05; Fig. 7i, p < 0.01; and Fig. 7j, p < 0.05, respectively) of TOH-containing emulgel-treated IMQ mice compared to those of emulgel-treated mice. These results support the notion that TOH-containing emulgel reduced systemic inflammation in the IMQ-induced mouse model of psoriasis.

The TOH-containing emulgel reduced IMQ-induced systemic inflammation. (a) Representative image of the spleen at the end of the experiment. (b) Relative spleen weights of the mice in all groups (n = 5). (c) Representative image of right axillary lymph nodes at the end of the experiment. (d) Relative right axillary lymph node weights of the mice in all groups (n = 5). (e–g) The mRNA expression of TNFα, IL-1, and IL-6 in the spleens of all groups of mice (n = 4). (h–j) The mRNA expression of TNFα, IL-1, and IL-6 in the lymph nodes of all groups of mice (n = 4). The data are presented as the means ± SD. Statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001.

Discussion

While TOH has been shown to suppress the release of many inflammatory cytokines in various cell lineages22, in-vivo data supporting the immunosuppressive effect remain generally lacking. Therefore, in the current study, we investigated the potential therapeutic benefit of TOH in a mouse model of IMQ-induced psoriasis. Topical application of TOH-containing emulgel reduced erythema, hyperkeratosis and scaling in the skin of IMQ-treated mice, suggesting reduced severity of the inflammatory disease. Our results also demonstrated that TOH-containing emulgel significantly reduced the extent of spleen inflammation and weight loss induced by IMQ. Notably, weight loss is indicative of disease severity and can be a symptom of spleen inflammation. Previous studies have suggested that IMQ-induced weight loss resulted from IL-17A-mediated response and subsequent accumulation of T cells23,24. In this study, serum level of IL-17A and splenic expression of TNFα, IL-1β and IL-6 was reduced in TOH-containing emulgel-treated IMQ mice. We therefore speculate that reduced IL-17A production and alleviation of spleen inflammation may contribute to a lesser degree of weight loss in TOH-containing emulgel-treated mice. Taken together, our data indicated that TOH-containing emulgel displayed a protective effect against IMQ-induced psoriasis-like pathology in mice.

IL-23 has been strongly implicated in the development and progression of psoriasis7,20,21,25,26,27. Along with IL-1β, IL-23 is essential for the generation and expansion of Th17 cells, which play a significant role in the pathogenesis of psoriasis28. Th17 cells secrete Th17-related cytokines, such as IL-17 and TNFα26,29 which promote dermal infiltration and activation of various immune cells, leading to exacerbation of skin inflammation30. In the present study, we found that TOH-containing emulgel treatment suppressed the release of IL-23, IL-1β, IL-17 and TNFα in the skin of IMQ mice. These data are consistent with the previous studies suggesting that TOH is an inhibitor of cytokine production15. In line with these findings, decreased infiltration of CD4+ T cells was observed in the skin of TOH-containing emulgel-treated IMQ mice. Given that IL-23, IL-17, IL-1β and TNFα are well-known for their contribution to the hallmark features of psoriasis20,21,26, we therefore considered that impaired production of these cytokines may be responsible for attenuation of IMQ-induced psoriasis-like pathology in TOH-containing emulgel-treated mice.

IL-17 and IL-23 regulate immune activation and inflammation through the JAK/STAT signaling4,5,6,7,25. Inhibition of the JAK/STAT pathway has been shown to reduce psoriatic inflammation31 and JAK2/STAT3 signaling has been associated with alleviated IMQ-induced pathology in several mouse model studies32,33. In this study, we found that mRNA expression JAK2 was decreased in the skin of TOH-containing emulgel-treated IMQ mice and the number of keratinocytes expressing JAK2, pJAK2, STAT3 and pSTAT3 was significantly reduced following TOH-containing emulgel treatment. These findings suggested that TOH-containing emulgel inhibited the activation of the JAK2/STAT3 pathway during the development of psoriasis. We also found that TOH-containing emulgel-treated IMQ mice exhibited reduced dermal expression of BCL2, suggesting decreased function of the JAK2/STAT3 pathway. It should be noted that the total protein levels of JAK2, pJAK2, STAT3 and pSTAT3 were comparable between the TOH-containing emulgel-treated and emulgel-treated groups. The discrepancy between this western blot and immunohistochemical staining results is likely attributed to the use of whole skin for the western blot analysis. It is possible that many cells in the dermis may be insensitive to TOH-containing emulgel and may not show a reduced JAK2/STAT3 signaling, leading to unchanged protein levels in skin samples. Collectively, our findings suggested that TOH-containing emulgel inhibited the activation of the JAK2/STAT3 pathway during the development of psoriasis.

Mast cells are regarded as initial responders that initiate and amplify inflammatory response in psoriatic skin18,19. They are not only the source of cytokines strongly implicated in psoriasis pathogenesis but also interact with other cells in the affected area, influencing the development and maintenance of psoriasis18,19. Mast cells are activated early in the formation of psoriatic lesions through induction of the IL-33/ST2 signaling pathway18. Our results showed that IL-33 production and ST2 expression were reduced in the skins of TOH-containing emulgel-treated mice, suggesting that TOH-containing emulgel may inhibit mast cell activation. We also found that TOH-containing emulgel-treated IMQ mice exhibited a lower number of mast cells in skin lesions than emulgel-treated IMQ mice. These findings suggested that impaired mast cell recruitment and activation in TOH-containing emulgel-treated mice may hamper skin inflammation and impede the development of IMQ-induced psoriasis.

In our study, a reduced expression of TNFα, IL-1β and involucrin was observed in the skin of TOH-containing emulgel-treated IMQ mice. Numerous studies have provided evidence supporting the roles of TNFα, IL-1β and involucrin during the development of psoriasis28. TNFα and IL-1β have been shown to upregulate the expression of keratin, including K6, K16 and K17 and promote proliferation of keratinocytes in psoriatic lesions34,35,36. Involucrin is a structural protein essential for forming the cornified cell envelope in keratinocytes17,30,37. It has been shown that involucrin is upregulated in keratinocytes of psoriatic patients and animal models30,38,39,40. While involucrin is not a direct driver of proliferation, its expression can be induced by factors that promote keratinocyte proliferation, suggesting it serves as a downstream marker of proliferation in psoriasis. Upregulation and aberrant localization of involucrin are indicative of disrupted differentiation of keratinocytes, as observed in the scaly plaques of psoriatic patients and mouse model17,38,39. Based on this information, we therefore consider that a reduction in keratinocyte proliferation and psoriatic skin lesions may be attributed to the inhibitory effects of TOH-containing emulgel on TNFα, IL-1β and involucrin expression.

Conclusion

This study demonstrated that a TOH-containing emulgel alleviates IMQ-induced psoriasis in mice by reducing inflammatory cell accumulation and cytokine secretion, primarily through suppression of the IL-23/IL-17 axis via regulation of the JAK2/STAT3 pathway. Given its effectiveness in treating psoriasis and its non-irritating properties in healthy mice, the TOH-containing emulgel appears to be a promising therapeutic agent for alleviating psoriasis. However, further in-depth investigations to explore other components of the JAK/STAT pathway and to assess both acute and chronic toxicity for a comprehensive safety profile and future clinical application.

Materials and methods

Materials

Tryptophol (TOH; C10H11NO) and bovine serum albumin (BSA) (Cat no. 9048-46-8) were purchased from Sigma‒Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Mayer’s haematoxylin (Cat no. 05-06002/L) and eosin Y plus alcoholic solution (Cat no. 05-11007/L) were purchased from Bio-Optica Milano Spa (San Faustino, Milano, Italy). Absolute ethanol (Cas no.64-17-5), xylene (Cas no. 1330-20-7) and formaldehyde 35–40% (Cas no. 50-00-0) were purchased from RCI Labscan (Pathumwan, Bangkok, Thailand). Giemsa stain solution (RA-002-05) was purchased from Biotech Reagent (Bangkok, Thailand). Toluene mounting media (Cas no. 108-88-3) was purchased from Fisher Chemical (Geel, Belgium, UK). An ELISA MAX™ Deluxe Set Mouse IL-1β Kit (Cat no. 432604), ELISA MAX™ Deluxe Set Mouse TNFα Kit (Cat no. 430904), ELISA MAX™ Deluxe Set Mouse IL-17A Kit (Cat no. 432504), ELISA MAX™ Deluxe Set Mouse IL-23 Kit (Cat no. 433704) and LEGEND MAX™ Mouse IL-33 ELISA Kit (Cat no. 436407) were purchased from BioLegend (San Diego, California). A rabbit monoclonal anti-β-actin (13E5) antibody (#4970S), rabbit monoclonal anti-phosphor-Stat3 (Tyr705) antibody (D3A7), rabbit monoclonal anti-Jak2 antibody (D2E12) were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, Massachusetts, USA). A rabbit polyclonal anti-STAT3 antibody (AB31370), rabbit polyclonal anti-Ki67 antibody (ab15580), rabbit monoclonal anti-Jak2 (phosphoY1007 + Y1008) antibody (AB32101), rabbit monoclonal anti-CD4 antibody (EPR19514) and protein blocking solution (AB64226) were purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, UK). The secondary antibody peroxidase AffiniPure goat polyclonal antibody to rabbit IgG (H&L) (111-035-003) was purchased from Jackson ImmunoResearch (West Grove, Pennsylvania, USA). The peroxidase (HRP) substrate Vector NovaRed (SK-4800) was purchased from Vector Laboratories (Newark, California). TRI Reagent® (Cat no. TR118) was purchased from Molecular Research Center, Inc. (Montgomery Rd., Cincinnati, OH, USA). ReverTra Ace™ qPCR RT Master Mix with gDNA Remover was purchased from TOYOBO Research Reagents (Osaka, Japan). A SensiFAST™ SYBR® No-ROX kit (BIO-98050, Bioline) was purchased from Meridian Bioscience (River Hills Drive, Cincinnati, OH, USA). T-PER™ tissue protein extraction reagent (REF 78510) was purchased from Pierce Biotechnology (Rockford, USA). Protease inhibitors (Roche cOmplete™, Mini Protease Inhibitor Cocktail, REF 04 693 159 001), chloroform (Cas no. 67-66-3) and 2-propanol (MilliporeSigma™, 1.09634) were purchased from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany). QubitTM protein assay kit (Invitrogen, REF Q33211) was purchased from Life Technologies Corporation (Eugene, Oregon, USA). BioTrace hydrophobic polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes with 0.45 μm pores (Pall no.66543) were purchased from Pall Corporation (Pensacola, USA). BD Difco™ skim milk (Ref 232100) was purchased from Becton Dickinson and Company (Sparks, Maryland, USA). The Colorcode prestain protein marker (Abbkine, Cat no. BMM3001) and superKine™ West Pico PLUS chemiluminescent substrate (Abbkine, Cat no. BMU101-EN) were purchased from CliniSciences (Nanterre, France). Petroleum jelly (Vaseline) was purchased from Unilever (London, UK). Five percent imiquimod cream (Aldara™) was purchased from Ensign Laboratories Pty Ltd. (Australia).

Preparation of the TOH-containing emulgel

Due to TOH is typically dissolved in organic solvents such as ethanol, and repeated topical application can induce skin irritation and contact dermatitis. Therefore, a TOH-containing emulgel was formulated to avoid these adverse effects and effectively deliver TOH to the skin, where it can be absorbed11. The emulgel formulation and emulgel containing TOL (100 µM) were prepared as previously described11. The concentration of TOL used was chosen on the basis of in vitro cell viability assays. The HaCat cell culture method is described in Supplementary Data 1, and the results for cell viability are shown in Supplementary Fig. S5.

Animal experiments

Healthy male BALB/c mice (6–8 weeks of age, weight 27 ± 1.37 g) were purchased from Nomura International Siam (Thailand). All the mice were housed under specific pathogen-free (SPF) conditions with the appropriate humidity and temperature and a 12-h light/dark cycle. The mice were allowed access to a standard pellet diet and drinking water ad libitum throughout the experiment. All experimental protocols and animal protocols used were approved by the ethical committee of the University of Phayao, Thailand (Approval Number 1-020-65).

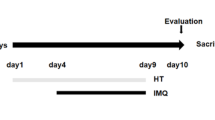

Establishment of IMQ-induced psoriasis-like lesions in mice

Thirty-two mice were randomly divided into four groups (n = 8 mice per group): (1) the control cream base group (Cream base), (2) the control TOH-containing emulgel group (Tryptophol), (3) the psoriatic mice treated with emulgel as a vehicle (IMQ + Emulgel), and (4) the psoriatic mice treated with TOH-containing emulgel (IMQ + Tryptophol). Before starting the experimental treatment for one day, the dorsal skin of the mice was shaved.

Experimental treatment

In the Cream base group, petroleum jelly (100 µl) was applied to the shaved areas of mice at 7:00 am, followed by application of the emulgel without TOH (100 µl) at 1:00 pm and 7:00 pm for 7 consecutive days.

In the TOH group, petroleum jelly (100 µl) was applied to the shaved areas of mice at 7:00 am, followed by application of the TOH-containing emulgel (100 µl) at 1:00 pm and 7:00 pm for 7 consecutive days.

In the IMQ + Emulgel group, 5% IMQ cream (topical dose, 62.5 mg) was applied to the shaved areas of mice at 7:00 am, followed by application of the emulgel without TOH (100 µl) at 1:00 pm and 7:00 pm for 7 consecutive days.

In the IMQ + TOH group, 5% IMQ cream (topical dose, 62.5 mg) was applied to the shaved areas of mice at 7:00 am, followed by application of the TOH-containing emulgel (100 µl) at 1:00 pm and 7:00 pm for 7 consecutive days.

After 7 days of treatment, all mice were anesthetized with isoflurane and sacrificed by cervical dislocation. Blood collection was performed via cardiac puncture. Skin lesions, lymph nodes, and spleens were collected for further analysis.

Assessment of skin inflammation severity

The severity of the skin lesions was investigated by a modified human scoring system, the PASI. The mice were assessed daily and individually for erythema, scaling, and skin thickening. Each parameter was scored independently on a scale from 0 to 4 (0, none; 1, mild; 2, moderate; 3, marked; and 4, obvious). The cumulative score, which combines erythema, scaling, and skin thickening, was used to evaluate the severity of skin inflammation24,30.

Histological analysis

H&E staining

The skin lesions were collected and preserved in 4% paraformaldehyde, embedded in paraffin, and then cut into 4 μm-thick sections with a rotary microtome. Following standard H&E staining procedures, the tissue sections were rehydrated, stained with H&E, dehydrated, cleared, mounted on slides, and coverslipped for pathological observation by light microscopy. Epidermal thickness was accurately measured with ImageJ software.

Giemsa staining

The skin sections were deparaffinized and rehydrated with a decreasing series of ethanol and distilled water. These sections were subsequently stained with Giemsa solution for 45 min, after which the excess dye was washed away with distilled water. The sections were dehydrated in an ethanol series and cleared with xylene. Finally, the sections were mounted on slides and coverslips. These skin sections were observed and photographed under a microscope. The mast cells were counted in 5 areas per 10× field.

Immunohistochemistry

After nonspecific antigens were blocked with protein blocking solution, the tissue sections were incubated with anti-CD4 (dilution 1:50), anti-Ki67 (dilution 1:100), anti-JAK2 (dilution 1: 500), anti-pJAK2 (dilution 1:50), and anti-STAT3 (dilution 1:50) and anti-pSTAT3 (dilution 1:100) antibodies at room temperature for 3 h. After washing, the tissue sections were incubated with the appropriate secondary antibody (dilution 1:500) for 1 h at room temperature. The slides were washed, and positive signals were subsequently visualized with NOVA Red, followed by counterstaining with Mayer’s haematoxylin. For quantitative analysis, the slides were imaged at a magnification of 10x. The CD4+, Ki67, JAK2, pJAK2, STAT3, and pSTAT3-positive cells were counted in 4 areas per 10X field.

Body weight and lymphatic organ weight

The mice’s body weight was recorded on days 1, 3, 5, and 7. The mice’s right axillary lymph nodes and spleens were removed, cleaned, and weighed after sacrifice on the 8th day. The right axillary lymph node weight and spleen weight were normalized to the body weight to obtain the organ index.

Cytokine analysis by ELISA

Serum and skin tissue preparation

The dorsal skin of the control or experimental mice was collected, the attached connective tissue was removed, and 0.1 cm3 of tissue was added to 1 ml of normal saline. Subsequently, the tissue was cut and ground thoroughly in a homogenizer to obtain a tissue suspension. The homogenized tissue was centrifuged at 4 °C at 3000 rpm for 15 min. The supernatant was removed and stored at − 20 °C for the ELISA experiments41.

The blood samples were allowed to clot at room temperature for 30 min and centrifuged at 2500×g at 4 °C for 15 min to collect the serum. The serum was collected and stored at − 20 °C for the ELISA experiments.

The levels of IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-17A, IL-23, and IL-33 in the dorsal skin and serum samples from the control and experimental groups were measured using commercial ELISA kits following the manufacturer’s instructions. The absorbance was measured at 450 nm using a spectrophotometer (VersaMax™ Microplate Reader, Molecular Devices, San Jose, CA, USA). The data were calculated and analyzed using the SoftMax Pro software version 6 (Molecular Devices).

RNA isolation and cDNA synthesis

Total RNA from the spleens, lymph nodes, and dorsal skin of control and experimental mice was isolated using TRIzol Reagent® according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The amount and quality of RNA were measured with a Nanodrop One (Thermo Fisher Scientific). From each sample, 1 μg of RNA was reverse transcribed into cDNA with cDNA synthesis kits according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The cDNA mixture was stored at − 20 °C for further analysis.

Analysis of gene expression by quantitative real-time PCR

The relative expression levels of the genes encoding TNFα, IL-1, IL-6, IL-33, ST2, K6, K16, K17, involucrin, JAK2, BCL2, CCND1, and STAT3, as well as TNFα, IL-1 and IL-6, in the dorsal skin of control and experimental mice as well as TNFα, IL-1 and IL-6 in the spleens and lymph nodes were measured via quantitative real-time PCR (RT‒qPCR) via a QIAquant Real-Time PCR Thermal Cycler (Qiagen, USA). The amplification was performed on a 96-well plate with a 20 μL reaction mixture consisting of 1 μL of cDNA from each tissue, 10 μL of SYBR, 0.4 μL of specific primers (10 μM/μL), and 8.2 μL of sterile distilled water. The thermal cycle profile for RT‒qPCR was as follows: one cycle at 95 °C for 3 min; 40 cycles at 95 °C for 3 s for denaturation and 60 °C for 20 s for annealing/extension; and one cycle at 95 °C for 15 s, 60 °C for 1 min, 95 °C for 30 s, and 60 °C for 15 s, respectively. All reactions were analysed in triplicate, and β-actin was amplified as an internal control. The details of the primers used in this experiment are presented in Supplementary Table 1. The comparative CT method (2−ΔΔCT method) was used to analyse the relative expression levels of inflammatory cytokine genes according to Livak and Schmittgen42. The target gene expressed was normalized to β-actin expression.

Western blot analysis

The dorsal skin of the mice (50 mg/sample) was homogenized and extracted with tissue protein extraction reagent supplemented with a protease inhibitor. The protein concentration was determined using a Qubit™ protein assay kit and Qubit™ 4 Fluorometer (Invitrogen, REF Q3326, Life Technologies Holding Pte Ltd, Singapore). Protein samples (100 μg/each) were separated by 7.5% and 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and then transferred to PVDF membranes (0.45 μm). The membranes were incubated with protein blocking buffer (3% skim milk and 2% BSA in 0.05% PBST) overnight at 4 °C and subjected to incubation with primary antibodies for 3 h at room temperature. The antibodies used to detect specific proteins included anti-JAK2 (dilution 1:1000), anti-pJAK2 (dilution 1:1000), anti-STAT3 (dilution 1:500), anti-pSTAT3 (Dilution 1:2000) and anti-β-actin (dilution 1:2000) antibodies. All the antibodies were diluted with blocking buffer. Afterwards, the blots were washed with PBST 3 times (5 min each) and subsequently incubated with secondary antibody (dilution 1:5000). Then, the blots were visualized using an enhanced chemiluminescence detection system (S1060; Azure Biosystems). Finally, the protein bands were quantified using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, USA).

Statistical analysis

The results of this study are presented as the means ± standard deviation (SD). Differences were assessed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) or Student’s t test. All the statistical analyses and graphs were generated with GraphPad software version 9.1.0. Statistical significance was considered at p values less than 0.05.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Guo, J. et al. Signaling pathways and targeted therapies for psoriasis. Signal. Transduct. Target Ther. 8(1), 437. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41392-023-01655-6 (2023).

Nestle, F. O., Kaplan, D. H. & Barker, J. Psoriasis. N. Engl. J. Med. 361, 496–509. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra0804595 (2009).

Zheng, T. et al. p38α deficiency ameliorates psoriasis development by downregulating STAT3-mediated keratinocyte proliferation and cytokine production. Commun. Biol. 7(1), 999. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-024-06700-w (2024).

Di, T. T. et al. Astilbin inhibits Th17 cell differentiation and ameliorates imiquimod-induced psoriasis-like skin lesions in BALB/c mice via Jak3/Stat3 signaling pathway. Int. Immunopharmacol. 32, 32–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intimp.2015.12.035 (2016).

Calautti, E., Avalle, L. & Poli, V. Psoriasis: a STAT3-centric view. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 19(1), 171. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms19010171 (2018).

Yang, X. O. et al. STAT3 regulates cytokine-mediated generation of inflammatory helper T cells. J. Biol. Chem. 282(13), 9358–9363. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.C600321200 (2007).

Bugaut, H. & Aractingi, S. Major role of the IL17/23 axis in psoriasis supports the development of new targeted therapies. Front. Immunol. 12, 621956. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2021.621956 (2021).

Jairath, V., Felquer, M. L. A. & Cho, R. J. IL-23 inhibition for chronic inflammatory disease. Lancet 404(10463), 1679–1692. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(24)01750-1 (2024).

Cather, J. C. & Crowley, J. J. Use of biologic agents in combination with other therapies for the treatment of psoriasis. Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 15(6), 467–478. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40257-014-0097-1 (2014).

Palmieri, A. & Petrini, M. Tryptophol and derivatives: natural occurrence and applications to the synthesis of bioactive compounds. Nat. Prod. Rep. 36(3), 490–530. https://doi.org/10.1039/c8np00032h (2019).

Kitisin, T., Muangkaew, W., Thitipramote, N., Pudgerd, A. & Sukphopetch, P. The study of tryptophol containing emulgel on fungal reduction and skin irritation. Sci. Rep. 13(1), 18881. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-46121-z (2023).

Inagaki, S. et al. Isolation of tryptophol as an apoptosis-inducing component of vinegar produced from boiled extract of black soybean in human monoblastic leukemia U937 cells. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 71(2), 371–379. https://doi.org/10.1271/bbb.60336 (2007).

Kosalec, I. et al. Genotoxicity of tryptophol in a battery of short-term assays on human white blood cells in vitro. Basic. Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 102(5), 443–452. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1742-7843.2007.00204.x (2008).

Schirmer, M. et al. Linking the human gut microbiome to inflammatory cytokine production capacity. Cell 167(4), 1125–1136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2016.10.020 (2016).

Malka, O. et al. Tryptophol acetate and tyrosol acetate, small-molecule metabolites identified in a probiotic mixture, inhibit hyperinflammation. J. Innate Immun. 15(1), 531–547. https://doi.org/10.1159/000529782 (2023).

Wang, H. et al. Gut Microbiota-derived tryptophan metabolites alleviate allergic asthma inflammation in ovalbumin-induced mice. Foods. 13(9), 1336. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods13091336 (2024).

Gnanaraj, P. et al. Downregulation of involucrin in psoriatic lesions following therapy with propylthiouracil, an anti-thyroid thioureylene: immunohistochemistry and gene expression analysis. Int. J. Dermatol. 54(3), 302–306. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijd.12565 (2015).

Zhou, X. et al. IL-33-mediated activation of mast cells is involved in the progression of imiquimod-induced psoriasis-like dermatitis. Cell Commun. Signal. 21(1), 52. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12964-023-01075-7 (2023).

Lin, A. M. et al. Mast cells and neutrophils release IL-17 through extracellular trap formation in psoriasis. J. Immun. 187(1), 490–500. https://doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.1100123 (2011).

Menter, A. et al. Interleukin-17 and interleukin-23: a narrative review of mechanisms of action in psoriasis and associated comorbidities. Dermatol. Ther. 11, 385–400. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13555-021-00483-2 (2021).

Li, H. & Tsokos, G. C. IL-23/IL-17 axis in inflammatory rheumatic diseases. Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol. 60(1), 31–45. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12016-020-08823-4 (2021).

Niwa, T., Kato, Y. & Osawa, T. In vitro anti-inflammatory activity of tyrosol and tryptophol: metabolites of yeast via the ehrlich pathway. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 48(2), 115–118. https://doi.org/10.1248/bpb.b24-00625 (2025).

Li, Q., Liu, W., Gao, S., Mao, Y. & Xin, Y. Application of imiquimod-induced murine psoriasis model in evaluating interleukin-17A antagonist. BMC Immunol. 22, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12865-021-00401-3 (2021).

Griffith, A. D. et al. A requirement for slc15a4 in imiquimod-induced systemic inflammation and psoriasiform inflammation in mice. Sci. Rep. 8(1), 14451. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-32668-9 (2018).

Liu, T. et al. The IL-23/IL-17 pathway in inflammatory skin diseases: from bench to bedside. Front. Immunol. 11, 594735. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2020.594735 (2020).

Di Cesare, A., Di Meglio, P. & Nestle, F. O. The IL-23/Th17 axis in the immunopathogenesis of psoriasis. J. Investig. Dermatol. 129(6), 1339–1350. https://doi.org/10.1038/jid.2009.59 (2009).

Chen, L. et al. Skin expression of IL-23 drives the development of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis in mice. Sci. Rep. 10(1), 8259. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-65269-6 (2020).

Cai, Y. et al. A critical role of the IL-1β–IL-1R signaling pathway in skin inflammation and psoriasis pathogenesis. J. Investig. Dermatol. 139(1), 146–156. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jid.2018.07.025 (2019).

Tesmer, L. A., Lundy, S. K., Sarkar, S. & Fox, D. A. Th17 cells in human disease. Immunol. Rev. 223(1), 87–113. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00628.x (2008).

Chen, Y. et al. Esculetin ameliorates psoriasis-like skin disease in mice by inducing CD4+ Foxp3+ regulatory T cells. Front. Immunol. 9, 2092. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2018.02092 (2018).

Furtunescu, A. R., Georgescu, S. R., Tampa, M. & Matei, C. Inhibition of the JAK-STAT pathway in the treatment of psoriasis: A review of the literature. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 25(9), 4681. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms25094681 (2024).

Wu, P., Liu, Y., Zhai, H., Wu, X. & Liu, A. Rutin alleviates psoriasis-related inflammation in keratinocytes by regulating the JAK2/STAT3 signaling. Skin Res Technol. 30(8), e70011. https://doi.org/10.1111/srt.70011 (2024).

Zhang, M. et al. Rosmarinic acid protects mice from imiquimod induced psoriasis-like skin lesions by inhibiting the IL-23/Th17 axis via regulating Jak2/Stat3 signaling pathway. Phytother. Res. 35(8), 4526–4537. https://doi.org/10.1002/ptr.7155 (2021).

Yang, L., Fan, X., Cui, T., Dang, E. & Wang, G. Nrf2 promotes keratinocyte proliferation in psoriasis through up-regulation of keratin 6, keratin 16, and keratin 17. J. Investig. Dermatol. 137(10), 2168–2176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jid.2017.05.015 (2017).

Komine, M. et al. Inflammatory versus proliferative processes in epidermis: tumor necrosis factor α induces K6b keratin synthesis through a transcriptional complex containing NFκB and C/EBPβ. J. Biol. Chem. 275(41), 32077–32088. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M001253200 (2000).

Romashin, D. D. et al. Keratins 6, 16, and 17 in health and disease: A summary of recent findings. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 46(8), 8627–8641. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb46080508 (2024).

Chen, J. Q. et al. Regulation of involucrin in psoriatic epidermal keratinocytes: the roles of ERK1/2 and GSK-3β. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 66, 523–528. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12013-012-9499-y (2013).

Iizuka, H. & Takahashi, H. Psoriasis, involucrin, and protein kinase C. Int. J. Dermatol. 32, 333–338. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-4362.1993.tb01467.x (1993).

Peng, J., Sun, S. B., Yang, P. P. & Fan, Y. M. Is Ki-67, keratin 16, involucrin, and filaggrin immunostaining sufficient to diagnose inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus? A report of eight cases and a comparison with psoriasis vulgaris. An. Bras. Dermatol. 92, 682–685. https://doi.org/10.1590/abd1806-4841.20176263 (2017).

Burger, C. et al. Blocking mTOR signaling with rapamycin ameliorates imiquimod-induced psoriasis in mice. Acta. Derm. Venereol. 97, 1087–1094. https://doi.org/10.2340/00015555-2724 (2017).

Zhang, S. et al. Hyperforin ameliorates imiquimod-induced psoriasis-like murine skin inflammation by modulating IL-17A-producing Γδ T Cells. Front. Immunol. 12, 635076. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2021.635076 (2021).

Livak, K. J. & Schmittgen, T. D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2− ΔΔCT method. Methods 25(4), 402–408. https://doi.org/10.1006/meth.2001.1262 (2001).

Acknowledgements

We are very grateful to the Laboratory Animal Research Center, University of Phayao for the animal facility as well as School of Medical Sciences, University of Phayao, Department of Microbiology and Immunology, Faculty of Tropical Medicine, Centex Shrimp and Department of Anatomy, Faculty of Science, Mahidol University for laboratory facility. We would like to express our sincere gratitude to Asst. Prof. Dr. Sitthisak Thongrong, Division of Anatomy, School of Medical Sciences, University of Phayao, for his invaluable technical assistance, as well as Asst. Prof. Dr. Somyoth Sridurongrit, Department of Anatomy, Faculty of Science, Mahidol University, for his invaluable technical assistance and suggestions.

Funding

This project is funded by a grant from the National Research Council of Thailand (NRCT): Contract number N42A660825 awarded to Arnon Pudgerd and a grant from the Health Systems Research Institute (Grant number: HSRI 67-027) awarded to Passanesh Sukphopetch.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.P. conceptualized, designed, and performed the study; participated in data collection and analysis; validated the data; performed formal analyses; and wrote the original draft of the manuscript. K.J. performed the study; collected the data; and performed the data analysis. L.P., S.J. and T.C. contributed to the data collection. W.M. and P.S. performed the cell culture and TOH cytotoxicity tests and prepared the emulgel and TOH-containing emulgel. R.V performed the study; validated the results; and interpreted the data. P.S. conceptualized and performed the study; interpreted the data; supervised the study; and reviewed and edited the manuscript. All the authors reviewed the manuscript and approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Accordance and ARRIVE guidelines

Accordance: We confirmed that all the experiments in this study were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. All the procedures of the study followed the ARRIVE guidelines.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pudgerd, A., Jongsomchai, K., Muangkaew, W. et al. A tryptophol-containing emulgel ameliorates imiquimod-induced mice psoriasis. Sci Rep 15, 19398 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-04431-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-04431-4