Abstract

Idiopathic short state (ISS) demotes a condition of diminished height in children lacking identifiable pathological etiologies, emering as a prominent elements, can precipitate ISS. We explored the prevalence, variability, organization, and contribution of gut microbiota in children affected by ISS. This study selected 58 ISS individuals aged 6–12, serving as the experimental group, 58 non-ISS children constituted the control group. Subsequent to the collection of fresh fecal specimens from both groups, 16 S rRNA gene sequencing facilitated an analysis and juxtaposition of species abundance, species richness, diversity, uniformity, structure, and composition within the intestinal microbiota of the childrens. There were significant differences in the abundance, species richness, diversity, evenness, and colony structure of gut microbiota between the two groups(P < 0.05). Compared with non-ISS children, ISS children have significantly reduced abundance, species richness, diversity, and evenness of their gut microbiota. Upon scrutinizing the gut microbiota composition, In children with ISS, there were 17 increased microorganisms and 13 decreased microorganisms at the three taxonomic levels of families, genus and species.The dominant bacteria in ISS mainly include Peptostreptococcaceae, Prevotella and Porphyromonas bennonis. The abundance, species richness, diversity, and evenness of the gut microbiota decrease, the surge in pro-inflammatory bacteria and key opportunistic pathogens, alongside the reduction of beneficial bacteria and certain opportunistic pathogens, may be linked to the occurrence and development of ISS disease.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Idiopathic short stature (ISS) denotes a condition characterized by a diminished stature in the absence of identifiable pathological etiology, accompanied by normal levels of growth hormone (GH). Despite inhabiting comparable environments, children with ISS manifest a height that is 2 standard deviations (-2SD) below the mean stature of the age-matched peers of the same gender and ethnicity1. This condition stands as a prevalent factor contributing to short stature among children, encompassing a substantial proportion, ranging from 33.69 to 59.05%, of all instances of dwarfism2,3. Presently, ISS lacks definitive therapeutic modalities, with the subcutaneous administration of exogenous recombinant human growth hormone (rhGH) emerging as the most efficacious approach to managing ISS4. However, the efficacy and outcomes of rhGH therapy for ISS remain contentious. Parents not only confront elevated treatment expenses but also confront the prospect of diminished cost-effectiveness stemming from variations in treatment response, which could impact their overall health outcomes. Consequently, exploring the pathogenesis of ISS and discerning early diagnostic markers hold pivotal importance in formulating rational treatment strategies and enhancing longitudinal stature outcomes.

Various studies have indicated that a multitude of factors influence the occurrence, progression, and outcome of ISS in children. These factors include genetic compoents such as family history, birth status, as well as acquired factors including diet, sleep, exercise, living conditions, and treatment regimens5. It has been observed that genetic predisposition dictates growth potential thereby showcasing distinct growth trajectories for each individual. The etiology of ISS remains to be completely elucidated, however, contemporary research endeavors have commenced shedding light on its potential pathophysiological underpinnings. Notably, Cianfarani et al. highlighted the complexities inherent in delineating ISS and appraising the effectiveness of therapeutic interventions1. Furthermore, a study in southern Thailand by Saengkaew et al. identified diverse factors contributing to ISS2. Recent research has highand alterations in gut microbiota composition, which could significantly impact the manifestation of ISS6,7,8,9,10. Notably, investigations by Million et al.11revealed that malnourished children exhibit modifications in gut microbiota, potentially leading to growth delays. Similarly, Gehriget et al.12 established a link between reduced gut microbiota diversity and the severity of growth impairment in children. Gough et al.’study13 proposed that diminished gut microbiota diversity and overgrowth of the Acidaminococcus sp. could hinder the growth of malnourished children. Collectively, these studies underscore the pivotal role of gut microbiota in children’s growth processes, providing valuable insights into the etiology and treatment of ISS. However, the existing literature on the gut microbiota of ISS children, both nationally and internationally, remains limited to preliminary explorations.

The early evidence of the impact of gut microbiota on host growth and development originated from fruit flies, studies in fruit flies have found that fruit flies without colonized gut microbiota develop slower than those that are traditionally raised14. Li et al.6 observed a decrease in the abundance of gut microbiota in children with ISS compared to non-ISS children, coupled with significant alterations in microbiota structure. This suggests that changes in the intestinal microbiota structure may be a contributory factor in the pathogenesis of ISS. Miao et al.7demonstrated alterations in the gut microbiota of children with ISS, showing a rise in the abundance of bacteria associated with intestinal inflammation. Prevotella, Bacteroides, Bifidobacterium, and Subdoligranulum were identified as potential diagnostic biomarkers. Furthermore, Li et al.‘s study8 shed light on the gut microbiota and metabolic profiles of ISS children with varying GH levels, offering fresh insights for the early detection and prognosis of short stature cases with abnormal GH levels. Additionally, Lazar et al.9observed substantial differences in the gut microbiota of ISS children compared to their height-normal siblings, while Yan et al.‘s10findings indicated a role of microbiome and microbiota-derived metabolites in the growth of ISS children. These studies present novel avenues for advancing the understanding of ISS mechanisms; however, research on the gut microbiota’s involvement in ISS remains constrained, emphasizing the necessity for further investigations encompassing diverse geographical regions to bridge this knowledge gap.

This study aims to characterize the gut microbiota profiles in children with idiopathic ISS by comparing the abundance, diversity, evenness, structure, and composition of gut microbiota between ISS and non-ISS children. The findings may contribute to understanding microbial signatures associated with ISS and provide a basis for future mechanistic studies.

Materials and methods

Research participants

Fifty-eight children diagnosed with ISS following growth hormone stimulation tests at a specialized women’s and children’s hospital in Sichuan Province between May 2022 and October 2022 were chosen as the case group. Simultaneously, 58 non-ISS children who received regular health assessments at the hospital’s physical examination center were selected as the control cohort. All participants in both cohorts were residents of Chengdu, Sichuan Province, of Han ethnicity, comparable in age, and with a balanced gender distribution, and similar lifestyle habits such as diet, sleep, and exercise.

Diagnostic criteria

The Diagnosis and Treatment Guidelines for Short stature Children15and the Standardized Growth Curve for Height and Weight of Chinese Children and Adolescents aged 0–1816 were used in this study. The diagnostic criteria for ISS group are: height below − 2SD or above the average height of non-ISS children of the same gender, age, and race, or below the 3rd percentile of the growth curve of non-ISS children; However, during delivery and infancy, there is a normal short stature without underlying pathological conditions, normal GH stimulation test, and no growth retardation caused by genetic metabolic diseases or various chronic diseases.On the other hand, the diagnostic criteria for control group are: height within ± 1SD of the average normal reference value for the same gender, age, region, and race, and without organic diseases or deformities.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

ISS group: Inclusion criteria: Height meets the ISS diagnostic criteria; Between the ages of 6 and 12; No organic diseases, genetic diseases, deformities, or chronic diseases, and no gastrointestinal inflammation or examination within the past 3 months; Children and parents are willing to participate in this study. Exclusion criteria: precocious puberty and simple early breast development; Using antibiotics or probiotics within the past 3 months; Psychological disorders or severe emotional disorders; The research participant exhibited non-compliance with the researcher’s examination and sample procurement procedures, resulting in an unsatisfactory test outcome. Consequently, the study was prematurely concluded due to the absence of over 20% of critical observation metrics.

Control group: inclusion criteria: height within ± 1SD of the average normal reference value for the same gender, age, region, and race; Between the ages of 6 and 12; No organic diseases, genetic diseases, deformities, or chronic diseases, and no gastrointestinal inflammation or examination within the past 3 months; Children and parents are willing to participate in this study. Exclusion criteria: Premature infants; Birth length and/or weight outside ± 1SD; Using antibiotics or probiotics within the past 3 months; Psychological disorders or severe emotional disorders; The research subject cannot cooperate with the researcher’s inspection and sample collection; The test specimen test result is unqualified; Terminate the study midway; More than 20% of the main observation indicators are missing.

Sample size calculation

The current investigation utilized the 1:1 pairing estimation algorithm commonly employed in case-control research and incorporated findings from Vonaesch et al.17 to compute a requisite sample size of 46 cases per cohort. Anticipating a potential attrition rate of 10–20%, the study aimed to enroll approximately 50–56 cases per group. After thorough review of pertinent literature and careful consideration of the study’s specific circumstances, a decision was made to include a total of 58 cases in each group, resulting in a combined sample size of 116 cases across the ISS and control groups.

Collection of fecal specimens, DNA extraction, and sequencing

Fresh fecal samples (3 g) were obtained from ISS and control groups and promptly preserved in the Boyou TM 11901-50 fecal nucleic acid preservation solution by Shanghai Bohao Biotechnology Co., Ltd (https://www.shbio.com/products/3033). The samples were capable of stored at room temperature for 14 days, and for extended periods at – 20 °C and − 80 °C. Transportation to the laboratory was carried out by specialized personnel within 2–3 days, with subsequent storage at – 80 °C.

Genomic DNA was extracted using the CTAB (Cetyltrimethylammonium Bromide) method18, followed by assessment of DNA purity and concentration through agarose gel electrophoresis. Post extraction, an appropriate amount of DNA was placed in a centrifuge tube and diluted to 1 ng with sterile water/µ L. Subsequently, the V3-V4 region of 16 S rRNA gene sequencing was amplified through PCR, utilizing the following primers: 341 F-CCTAYGGGRBGCASCAG; 806R-GGACTACNNGGGTATCTAAT. The PCR product underwent 2% agarose gel electrophoresis for detection, followed by recovery of the target strip (corresponds to the expected size range of 450–550 bp as visualized by ethidium bromide staining on a 2% agarose gel electrophoresis) using the gel recovery kit produced from Qiagen Company (Tiangen, catalog number DP214, Beijing, China). Library construction was performed using the NEBNext ® Ultra ™ The IIDNA Library PreP Kit, with quantification of the constructed library carried out via Qubit and q-PCR. Once the library was qualified, sequencing was conducted using the NovaSeq6000 platform. After removal of barcode and primer sequences from the split sample data, concatenation of samples was achieved using FLASH software (V1.2.11, https://www.ccb.jhu.edu/software/FLASH/). Sequencing raw reads were processed through a quality control pipeline using fastp (version 0.19.6). The filtering parameters included: adapter trimming disabled (-A), polyG tail trimming enabled (-g), minimum base quality score of Q19 (-q 19), maximum 15% low-quality bases permitted per read (-u 15), and exclusion of reads containing ≥ 5 ambiguous bases (-n 5). Subsequent analyses were performed using the obtained high-quality clean reads. Finally, Vsearch software was used to compare Clean reads with the database for chimeras detection and removal, ultimately obtaining the final valid data. Sequencing services encompassing library preparation and high-throughput sequencing utilizing the NovaSeq 6000 platform were rendered by Beijing Nuohe Zhiyuan Biotechnology Co., Ltd., a distinguished entity recognized for its proficiency in genomic sequencing and bioinformatics analysis. This company undertook the task of producing the primary sequence data pivotal to our investigative endeavors, guaranteeing the integrity and dependability of the sequencing outcomes.

Bioinformatics analysis

We utilized Quantitative Insights into Microbial Ecology version 2(QIME2) and R software package (v3.6.0) for data analysis. Use the DADA2 module in QIIME2 software to denoise “Effective reads” which are high-quality sequence reads that have passed the quality control and denoising steps, and filter out sequences with an abundance less than 5, in order to obtain the final Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs) and feature table. Subsequently, these ASVs were cross-referenced with the database via QIIME2 to acquire species information linked to each ASV, with species annotation sourced from the Silva138.1 database. Furthermore, the alpha diversity, encompassing metrics such as Observed species, Chao 1, Shannon, Simpson, and Pielou’s evenness, was assessed for each sample utilizing the QIIME2 platform. These metrics offer a thorough evaluation of species richness (as demonstrated by Observed species and Chao 1), diversity (reflected in Shannon index and Simpson index), and evenness (illustrated by Pielou-e index) within the microbiota communities. To compare the alpha diversity index between the ISS and control group, the non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test was utilized, which is appropriate for comparing rank differences across groups without assuming a normal distribution. The significance level chosen for the test was α = 0.05, and post hoc pairwise comparisons were adjusted for multiple testing using the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure to maintain control over the false discovery rate. Beta Diversity was utilized to delineate the relative distinctions among samples, with Unifrac distance being calculated using QIIME2, and Principal Co-ordinates Analysis (PCoA) and Non-Metric Multi-Dimensional Scaling (NMDS) analysis executed in R software. To identify differential bacterial communities, the study employed linear discriminant analysis effect size (LEfSe), supported by Kruskal Wallis and Wilcoxon tests for analysis. Subsequently, linear discriminant analysis was employed to reduce data dimensionality, producing Linear discriminant analysis scores (LDA scores). Any LDA score exceeding an absolute value of 4 was considered statistically significant.

Data analysis

IBM SPSS Statistics 26.0 software was used for both data input and statistical analysis. The particulars concerning children, family, and the historical background of children are delineated through the application of frequency, percentage, mean, standard deviation, median, and quartile measurements. The quantitative data underwent assessments for normality through Kolmogorov-Smirnov (K-S) tests, with normally distributed data scrutinized using independent sample t-tests, and non-normally distributed data analyzed using Mann-Whitney U-tests. Qualitative data is examined through chi-square testing. Inspection level α = 0.05, P-value < 0.05 indicates a statistically significant difference.

Ethical considerations and quality control

Approval for this study was granted by the Medical Ethics Committee of West China Second University Hospital, Sichuan University, with the ethical code of Medical Research 2022 Lun Approval No. (110), and all participants provided informed consent. Strictly adhere to the principles of informed consent, confidentiality, harmlessness, and benefit during the research process. To ensure research quality, strict quality control is implemented during the research design, implementation, and statistical analysis stages.

Results

General information

The present study characterized the gender ratio of two groups of children as moderate and comparable in age. The ISS group exhibited an average age of (9.38 ± 1.80) years and an average height of (120.99 ± 9.60) cm, while the control group had an average age of (9.35 ± 1.82) years and an average height was (137.97 ± 12.98) cm. There was no statistically significant variances in age, genetic target height, and birth length between the two groups (P > 0.05); however, a statistically significant contrast was observed in height, weight, Height SD、Height SDS、Weight SD、Weight SDS and BMI (P < 0.05) (Table 1).

Sequencing data results and quality evaluation

The raw sequencing data (Raw Data) may contain some interfering data (Dirty Data). To ensure the accuracy and reliability of the analysis results, Raw Data is concatenated and filtered to obtain valid data (Clean Data), which is then denoised using DADA2 to filter out sequences with relative abundance less than 5, and finally obtain the final ASV19.

This study included a total of 116 samples, with 1,876,010 high-quality sequences measured in the ISS group and the control group, with an average of 32,345 sequences per sample. ASV clustering was performed on the valid data of all samples, resulting in a total of 12,746 ASVs. There are a total of 4509 ASVs unique to ISS, 6154 ASVs unique to the control group, and 2083 ASVs common to both groups of children. According to the sequencing results, the proportion annotated to the boundary level was 99.2%, resulting in a total of 44 phyla (98.3%), 111 classes (98.1%), 256 orders (96.8%), 435 families (92.9%), 1060 genera (76.0%), and 849 species (15.8%).

Alpha diversity analysis

The results indicated a decreased level of alpha diversity within the ISS group compared to the control group. Specifically, the Observed species and Chao 1, which are measures of species richness, as well as the Shannon index, Simpson index, and Pielou-e index were all significantly lower in the ISS group (P = 0.016, P = 0.016, P = 0.007, P = 0.012, and P = 0.025, respectively) as opposed to the non-ISS group. These differences were deemed statistically significant (P < 0.05) (Fig. 1; Table 2).

Box plot of inter group differences in alpha diversity index. The horizontal axis of the box chart represents grouping, and the vertical axis represents the corresponding alpha diversity value. (A) Observed species (a measure of species richness), (B) Chao 1 (a measure of species richness), (C) Shannon index, (D) Simpson index, (E) Pielou-e index.

Differences in bacterial composition between groups

The Beta polymorphism investigation conducted in this study revealed distinct dissimilarities in gut microbial communities between the ISS group and the control group, with inter-group discrepancies surpassing intra-group variations, as illustrated in Fig. 2A. Additionally, NMDS analysis displayed a clustering of species from the two children groups into distinct clusters, with a Stress value of 0.13, underscoring disparities in microbial community composition among the sampled cohorts (Fig. 2B).

Beta polymorphism analysis: Based on Weighted Unifrac distance, Each point represents one sample, and the distance between points represents the degree of difference. (A)PCoA diagram: the percentage represents the contribution of the principal component to the sample difference; (B)NMDS diagram: Stress < 0.2 indicates that NMDS can accurately reflect the degree of difference between samples.

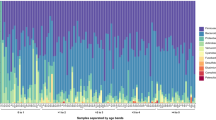

Relative species abundance

In the context of species abundance at the family level, an examination of the top 10 species with an average relative abundance ranking in the two distinct groups of children, as compared to the control group, revealed notable differences. Specifically, within the intestinal tract of ISS children, there was a significant increase in the average relative abundance of Peptostreptococcaceae (32.12% VS 0.49%, P < 0.001), Prevotellaceae (15.66% vs. 5.73%, P < 0.001), and Porphyromonadaceae (8.49% VS 0.11%, P < 0.001), while the difference in Lactobacillaceae (0.85% VS 0.18%, P = 0.152) was not statistically significant. However, the average relative abundance of Enterobacteriaceae (2.62% VS 19.64%, P < 0.001), Lachnospiraceae (4.74% VS 16.43%, P < 0.001), Bacteroidaceae (5.61% VS 16.54%, P < 0.001), Ruminococcaceae (4.42% VS 14.40%, P < 0.001), Bifidobacteriaceae (0.75% VS 3.06%, P = 0.001), and Selenomonadaceae (0.19% VS 1.32%, P = 0.025) exhibited a decrease (Fig. 3A).

In comparison to the control group, the species abundance at the genus level among ISS children displayed notable variation. Prevotella (15.54% VS 5.28%, P < 0.001), Ezakiella (6.47% VS 0.07%, P < 0.001), Anaerococcus (4.05% VS 0.05%, P < 0.001), Fenollaria (9.72% VS 0.19%, P < 0.001), and Porphyromonas (8.49% VS 0.11%, P < 0.001) exhibited increased average relative abundance rankings at the genus level, whereas Bacteroides (5.61% VS 16.54%, P < 0.001), Subdolibranulum (0.41% VS 1.76%, P = 0.019), Faecalibacterium (3.42% VS 10.70%, P < 0.001), Bifidobacterium (0.74% VS 3.06%, P = 0.001), and Escherichia/Shigella (0.75% VS 8.11%, P < 0.001) decreased average relative abundance (Fig. 3B).

In terms of species abundance at the species level, a comparison was made among the top 10 species with an average relative abundance ranking at the species level in two distinct groups of children in relation to the control group. The results indicated that ISS children exhibited an average increase in relative abundance by 8 species, specifically Prevotella bivia (1.99% VS 0.04%, P = 0.038), Prevotella disiens (4.03% VS 0.03%, P < 0.001), Prevotella corporis (1.69% VS 0.01%, P = 0.016), Prevotella timonensis (3.92% VS 0.07%, P < 0.001), Porphyromonas bennonis (6.34% VS 0.05%, P < 0.001), Campylobacter humis (3.28% VS 0.04%, P < 0.001), Lactobacillus fermentum (0.36% VS < 0.01%, P = 0.312), and Anaerococcus vaginalis (1.88% VS 0.01%, P < 0.001). Conversely, the average relative abundance of Prevotella copri (1.02% VS 4.00%, P = 0.017) showed a significant decrease, while Bacteroides fragilis (0.69% VS 1.09%, P = 0.416) exhibited no statistically significant change (Fig. 3C).

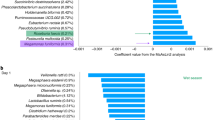

Analysis of inter group microbial diversity

The utilization of the LEfSe method for constructing evolutionary branching diagrams (Fig. 4A) and LDA value distribution histograms (Fig. 4B) led to the identification of LDA absolute values exceeding 4, indicating statistical significance in the LDA value distribution histograms. By assessing the magnitude of LDA absolute values, this study investigated differences in species and predominant bacterial communities between the ISS group and the control group. The analysis revealed a total of 20 dominant bacterial communities at the family, genus, and species levels in the ISS group, contrasting with 11 dominant bacterial communities in the control group. Notably, at the family level, the enriched dominant bacteria in the ISS group primarily included Peptostreptococcaceae (LDA = 5.20), along with genus-level taxa Prevotella (LDA = 4.70) and species-level Porphyromonas bennonis (LDA = 4.49), while the control group predominantly exhibited Enterobacteriaceae (family level, LDA = 4.94), Bacteroides (LDA = 4.74), and Prevotella copri (LDA = 4.19).

In the context of family-level analysis, ISS children demonstrate the presence of 5 dominant bacterial communities, namely Prevotellaceae, Peptostreptococcaceae, Veillonellaceae, Campylobacteraceae, and Porphyromonaceae. Conversely, non-ISS children exhibit 5 distinct species including Enterobacteriaceae, Lachnospiraceae, Bacteroidaceae, Ruminococcaceae, and Bifidobacteriaceae. Upon delving into the genus level, ISS children showcase 9 dominant bacterial communities such as Dialester, Finegodia, Campylobacter, Anaerococcus, Ezakiella, Peptoniphilus, Porphyromonas, Fenollaria, and Prevotella, whereas their non-ISS counterpart manifest 4 species, notably Bacteroides, Escherichia/Shigella, Faecalibacterium, and Bifidobacterium. At the species level, ISS children harbor 6 dominant bacterial communities like Prevotella disiens, Prevotella buccalis, Prevotella temporonensis, Porphyromonas bennonis, Campylobacter humis, and Dialister propionicifaciens. In contrast, non-ISS children possess 2 prevalent species, Bacteroides vulgatus and Prevotella copri (Fig. 4B).

Discussion

The past few years have witnessed a growing global focus on short stature as a significant issue. This pioneering study investigates the gut microbiota of children with ISS in Chengdu, located in southwestern China. Findings reveal that ISS children exhibit diminished abundance, diversity, and evenness of gut microbiota compared to their control group. Noteworthy distinctions emerge in the structure and composition of gut microbiota between the two cohorts, indicating alterations in the gut microbiota composition of ISS children that could potentially impact their growth and developmental processes.

The research presented significant variations in the species richness, diversity, and evenness of gut microbiota observed in two distinct groups of children. In comparison to the control group, the group of ISS exhibited notably diminished levels of the species richness, diversity, and evenness, suggesting a significantly lower alpha diversity in the intestinal microbiota of ISS children compared to the non-ISS group. This disparity may be correlated with the onset and progression of ISS-related conditions. Alterations in alpha diversity are commonly recognized as indicative of dysbiosis in the human gut microbiota, with reduced alpha diversity linked to deteriorating health conditions. A higher intestinal alpha diversity is essential in maintaining the homeostasis of the gut environment, signifying a crucial marker of gastrointestinal health. Conversely, reduced alpha diversity may signify an imbalanced gut microbiota, diminished health, or the presence of diseases6,20,21,22. In a related study, Li et al.6 noted lower species abundance in the ISS group compared to the non-ISS children group, albeit without a significant diversity distinction between the two groups, a finding that slightly deviates from the outcomes of the present study. This discrepancy may be attributed to two plausible factors. Firstly, Li et al.‘s research was conducted in Shanghai, East China, whereas the current study was conducted in Chengdu, Southwest China, where children exhibit notable dietary differences (e.g., spicy diet in Chengdu versus light diet in Shanghai), potentially influencing gut microbiota metrics. Secondly, Li et al. focused on children aged 4–8 as the ISS population, whereas this study concentrated on children aged 6–12 (a group with a higher incidence of diagnosis). Variations in age may also impact the diversity of gut microbiota alpha diversity.

The analysis findings from both PCoA and NMDS revealed substantial distinctions in the gut microbiota structure between the ISS and the control group cohorts. It was observed that the intra-group variance was less pronounced than the inter-group dissimilarity, suggesting the validity of the grouping methodology employed in this study. Notably, the intestinal microbiota composition of the ISS children exhibited discernible alterations in comparison to the control group, aligning with previous research findings6,23. The marked reduction in species richness, diversity, and evenness of gut microbiota in ISS children compared to their non-ISS counterparts, coupled with significant structural modifications, lead us to postulate that the notable changes in gut microbiota diversity and composition in ISS children could potentially contribute to the etiology and progression of ISS-related conditions.

The human gut microbiota exerts a profound influence on health and disease states, being likened to a novel physiological “organ“24.Analyzing the microbial composition and variations within the gut at various taxonomic hierarchies is instrumental in discerning the pathogenic and symbiotic bacteria present. It was noted during the course of this study that children with ISS exhibited a marked increase in the prevalence of pro-inflammatory microorganisms and significant opportunistic pathogens within the gastrointestinal tract. Conversely, the levels of beneficial bacteria and specific opportunistic pathogens were markedly reduced in comparison to the control cohort.

The research conducted demonstrated that the relative abundance of Prevotellaceae and Prevotella in the intestinal tract of children with ISS was higher compared to the control group. Prevotella is a Gram-negative anaerobic bacterium prevalent on various mucosal surfaces in the human body, including the oral, respiratory, intestinal, and urogenital tracts25,26. Previous studies have indicated that elevated levels of Prevotella in the oral cavity are linked to early stunted growth in children27. It is postulated in this study that the over representation of Prevotella in the intestines of ISS children may initiate a chronic inflammatory response, leading to intestinal mucosal damage, systemic inflammation, and subsequent impacts on growth. While this association suggests a potential contributing factor to ISS, the precise underlying mechanisms require further investigation and elucidation.

Compared to the control group, the average relative abundance of Porphyromonadaceae and Porphyromonas in the intestinal microbiota of children with ISS was found to be higher. Porphyromonas, a Gram negative, rod-shaped specialized anaerobic bacterium prevalent in the oral cavity, is recognized as a significant pathogen in periodontitis28. Studies have demonstrated that Porphyromonas colonization in the oral cavity can compromise innate host defenses, inciting oral inflammation and leading to alterations in the subgingival microbiota composition, fostering ecological imbalances29. Notably, Bifidobacterium has been shown to enhance the absorption and utilization of vitamin K, a vital factor influencing Porphyromonas, with competition for this substrate potentially restraining pathogen proliferation30. The analysis of gut microbiota in ISS children revealed elevated Porphyromonas levels and diminished Bifidobacterium content. This observation supports the notion that reduced Bifidobacterium presence in ISS children might impede vitamin K absorption and utilization, consequently elevating Porphyromonas levels. Additionally, findings from Donley et al.31 suggest that age plays a pivotal role in immune responses to Porphyromonas related microorganisms, with this study cohort falling within the school-age range, a period conducive to Porphyromonas enrichment. Thus, the augmented average relative abundance of Porphyromonas in ISS children could potentially be linked to the etiology of ISS.

In this study, the comparison between the ISS and the control groups revealed elevated the average relative abundance levels of Campylobacteracea and Campylobacter in the ISS children cohort. Campylobacter, a zoonotic pathogen known as a primary culprit of bacterial foodborne illnesses in humans, is typically transmitted through various pathways including consumption of undercooked poultry meat or raw dairy, direct contact with animals, contaminated water sources, fecal-oral routes, and environmental pollutants32,33. Rogowski et al.34 demonstrated a negative association between Campylobacter and children’s growth, emphasizing its significant impact on developmental progress. Mitigating exposure to Campylobacter could potentially alleviate global developmental delays. Lee et al.35 identified an link between both symptomatic and asymptomatic Campylobacter infections and growth impairments in children within a nine-months period post-infection. Additionally, Sanchez et al.36 reported a detrimental correlation between Campylobactor and child growth in urban Bangladeshi cities, highlighting the adverse effects on children’s development in such environment. The notable presence of Campylobacter in the gastrointestinal tract of ISS children in this study suggests a potential disruption of their gut microbiota, which in turn could influence their growth patterns.

The research revealed that the mean relative abundance of Anaerococcus, an intestinal opportunistic pathogen, was notably elevated in children diagnosed with ISS compared to those in the control group. Anaerococcus is commonly found colonizing the human skin and gastrointestinal mucosa, being a crucial element of the typical bacterial microbiota. In conditions where the body’s tissues suffer from ischemia, hypoxia, necrosis, or infection by aerobic bacteria, the local oxygen levels decrease, potentially triggering a surge in Anaerococcus levels, thereby heightening the risk of systemic infection37. The study by Tall et al.38 demonstrated in their study the discovery of a novel species of Anaerococcus in the fecal samples of malnourished children from Nigeria, a finding that aligns with the current investigation’s outcomes. The research suggests a plausible association between Anaerococcus and the onset and progression of ISS, although the precise underlying mechanism necessitates further elucidation.

The relative abundance of Veillonellaceae in the intestinal tract of children with ISS demonstrated a notable increase compared to the control group. Veillonellaceae, a prevalent oral microbiota commonly found on dental plaques, exhibits a rise in species count with diminishing levels of oral hygiene39. Previous studies have suggested a potential correlation between oral Veillonellaceae and developmental delays in children40. Consequently, the elevated levels of Veillonellaceae in ISS children may signify a decline in oral hygiene practices, potentially influencing dietary choices and nutrient intake, thereby contributing to growth retardation among ISS children. Future investigations could involve the collection of oral saliva samples alongside fecal samples to substantiate this hypothesis. Furthermore, the average relative abundance of opportunistic intestinal pathogens Peptostreptococcaceae, Fenollaria, and Ezakiella in the ISS children group significantly exceeded that of the control group. These findings warrant further exploration of the underlying reasons and mechanisms in forthcoming research endeavors.

The study revealed a notable disparity in the relative abundance of Enterobacteriaceae between the ISS children group and the control group, despite both falling under the category of opportunistic pathogens. Pathogenic members of the Enterobacteriaceae family are recognized as key causative agents in foodborne enteritis and zoonotic infections, and have been implicated in sporadic to pandemic outbreaks of human diseases. Its widespread presence in food sources has contributed to significant health and environmental concerns particularly in developing nations41. Previous research has established a correlation between reduced levels of Enterobacteriaceae and the incidence of infectious diseases both within and beyond the gastrointestinal trac42,43. Consequently, the substantial reduction in Enterobacteriaceae relative abundance observed in the intestinal microbiota of ISS children in this investigation suggests a potential heightened susceptibility to intestinal infections, thereby contributing to the pathogenesis of related diseases.

The mean relative abundance of Bacteroidaceae and Bacteroides in the group of children aboard the ISS was found to be lower compared to the control group. Bacteroides, a Gram-negative bacillus known as a potential colonizing bacterium of the human colon, can exhibit both beneficial and pathogenic characteristics depending on its localization within the host44,45. The mean relative abundance of Bacteroidaceae and Bacteroides in the group of children aboard the ISS was found to be lower compared to the control group. Bacteroides, a Gram-negative bacillus known as a potential colonizing bacterium of the human colon, can exhibit both beneficial and pathogenic characteristics depending on its localization within the host45. This process aids in food digestion, nutrient and energy production necessary for growth and development, immune regulation, and prevention of bacterial and viral infections. The reduction in the average relative abundance of Bacteroides in ISS children suggests a potential weakening of its roles in providing essential nutrients and energy for growth, immune modulation, and defense against infections, which could possibly impact the growth of ISS children. This observation may present another contributing factor to the onset and progression of ISS.

The findings indicated a noteworthy reduction in the average relative abundance of species belonging to the Ruminococcaceae and Lachnospiraceae families. within the intestinal composition of children diagnosed with ISS when compared to the control group. Both taxa are recognized as beneficial microbiota residents in the gut ecosystem, known for their capacity to generate short-chain fatty acids (SCFA), facilitate the proliferation of probiotic microorganisms, enhance immune system functionality, and confer favorable effects on overall physiological well-bein46,47. Particularly, Ruminococcaceae plays a pivotal role in facilitating carbohydrate assimilation and exhibits commendable cellulose digestive capabilities, thereby bearing significant implications for ameliorating malnutrition, fostering weight gain, and sustaining optimal health status48. Moreover, Kane et al.49 outlined the microbial composition of the pediatric gut and reported an average relative abundance of Lachnospiraceae at around 16.8%. In the context of this study, the ISS group displayed a significantly lower average relative abundance of Lachnospiraceae, at 4.74% compared to 16.43% in the control group. Consequently, it is postulated that the diminished presence of Ruminococcaceae and Lachnospiraceae in the intestines of ISS children may lead to reduced SCFA production, consequently impacting the role of SCFA in the body’s metabolic processes. This observation could potentially contribute to the etiology and progression of idiopathic short stature.

Compared to the control group, ISS children exhibited a reduced relative abundance of Bifidobacteriaceae in their intestinal tract. Bifidobacteriaceae, a crucial beneficial microorganism in the human gut, plays a significant role in various physiological functions including maintaining the biological barrier, providing nutrition, enhancing gastrointestinal function, and boosting immunity for human health50. Studies have indicated that the positive impacts of probiotics on human health are closely linked to the fermentation metabolites produced by bacteria, such as SCFA, which can modulate the intestinal microbiota, improve intestinal epithelial barrier function, suppress the production of antimicrobial peptides, stimulate the secretion of inflammatory mediators, strengthen immunity, exhibit anti-inflammatory and anti-allergic effects, and prevent pathogen infiltration into the body51,52. Furthermore, the average relative abundance of Lactobacillaceae in the intestinal microbiota of ISS children has increased, primarily due to the rise in the average relative abundance of Lactobacillaceae in their intestines. Nonetheless, there was no statistically significant variance in the average relative abundance of Lactobacillaceae in the intestines between the two groups of children. Probiotics containing Bifidobacteriaceae and Lactobacillaceae have been broadly employed to modulate gut microbiota, enhance immunity, display anti-inflammatory and anti-allergic effects, inhibit pathogen invasion, fortify the intestinal immune barrier, and reduce the generation of pro-inflammatory cytokines53. Therefore, it is hypothesized that the reduction of Bifidobacteriaceae in the intestines of ISS children may impact the production of their metabolic product SCFA, impede their nutritional metabolism, and compromise their intestinal immune barrier function. The decline in beneficial bacteria could also be associated with the onset and progression of ISS. Despite alterations in their intestinal function, further investigation is warranted to explore the relationship between the two phenomena.

Conclusions

This research, conducted for the first time, centered on children with ISS and non-ISS children in Chengdu, Sichuan Province. By utilizing 16 S rRNA gene sequencing technology, the study investigated the abundance, species richness, diversity, evenness, structure, and composition of gut microbiota in both groups. The findings revealed a significant decrease in abundance, species richness, diversity, and evenness of gut microbiota in children with ISS compared to the non-ISS children. Moreover, notable differences were observed in the structure and composition of gut microbiota between the two groups, particularly at the family, genus, and species levels. Notably, the relative abundance of pro-inflammatory bacteria and major opportunistic pathogens in the intestinal tract of children with ISS was notably higher, while beneficial bacteria and some opportunistic pathogens exhibited a significant decrease in relative abundance when compared to the non-ISS children group. These alterations in gut microbiota could potentially play a role in the onset and progression of ISS.

However, there are limitations in the current study, including the single-center design which may not fully capture the nationwide diversity of gut microbiota in children with ISS. Additionally, establishing a causal relationship between ISS and gut microbiota in case-control studies proves challenging. The study mainly focuses on the gut microbiota profile at the time of ISS diagnosis, overlooking the dynamic changes and mechanisms occurring before and after rhGH treatment. To address these gaps, the research group plans to conduct multi-center, longitudinal studies investigating the dynamic alterations in gut microbiota at 3 months, 6 months, and 1 year post-diagnosis of ISS in children. In future studies, we will aim to acquire a more extensive array of data and information from individuals with ISS, encompassing detailed clinical records, lifestyle particulars, genetic profiles, environmental influences, among others. This endeavor seeks to facilitate a deeper comprehension of the intricate determinants contributing to ISS. Concurrently, leveraging the wealth of information gathered, we will endeavor to devise strategies for mitigating the onset of ISS and tailoring treatment regimens to enhance efficacy and foster a higher standard of living for those affected by ISS. Furthermore, cohort studies and animal experiments will be employed to delve deeper into these relationships and potentially regulate gut microbiota through probiotics and lifestyle interventions, offering novel avenues for the prevention, treatment, and personalized care of ISS.

Data availability

The microbiome sequencing data generated in this study are available in the CNGB Sequence Archive (CNSA) of China National GeneBank DataBase (CNGBdb) under accession number CNP0005704 [https://db.cngb.org/search/?q=CNP0005704]. Additional data are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Inzaghi, E., Reiter, E. & Cianfarani, S. The challenge of defining and investigating the causes of idiopathic short stature and finding an effective therapy. Horm. Res. Paediatr. 92 (2), 71–83. https://doi.org/10.1159/000502901 (2019).

Saengkaew, T., McNeil, E. & Jaruratanasirikul, S. Etiologies of short stature in a pediatric endocrine clinic in Southern Thailand. J. Pediatr. Endocrinol. Metab. 30 (12), 1265–1270. https://doi.org/10.1515/jpem-2017-0205 (2017).

Li, X. et al. Analyzing the etiology of 1 496 children with short stature and Establishing the predict model of growth hormone deficiency using IGF-1 levels. J. Clin. Pediat. 30 (12), 1110–1115. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1000-3606.2012.12.003 (2012).

Miller, B. S., Velazquez, E. & Yuen, K. C. J. Long-Acting growth hormone Preparations - Current status and future considerations. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 105 (6), e2121–e33. https://doi.org/10.1210/clinem/dgz149 (2020).

Rogol, A. D. & Hayden, G. F. Etiologies and early diagnosis of short stature and growth failure in children and adolescents. J. Pediatr. 164 (5 Suppl), S1–14e6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2014.02.027 (2014).

Li, L. et al. Characteristics of gut Microbiome and its metabolites, short-Chain fatty acids, in children with idiopathic short stature. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 13, 890200. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2022.890200 (2022).

Miao, J. et al. Characteristics of intestinal microbiota in children with idiopathic short stature: a cross-sectional study. Eur. J. Pediatr. 182 (10), 4537–4546. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-023-05132-8 (2023).

Li, L. et al. Impact of different growth hormone levels on gut microbiota and metabolism in short stature. Pediatr. Res. 96 (1), 115–123. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-024-03140-4 (2024).

Lazar, L. et al. Children with idiopathic short stature have significantly different gut microbiota than their normal height siblings: a case-control study. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 15, 1343337. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2024.1343337 (2024).

Yan, L. et al. Gut microbiota and metabolic changes in children with idiopathic short stature. BMC Pediatr. 24 (1), 468. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-024-04944-3 (2024).

Million, M., Diallo, A. & Raoult, D. Gut microbiota and malnutrition. Microb. Pathog. 106, 127–138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.micpath.2016.02.003 (2017).

Gehrig, J. L. et al. Effects of microbiota-directed foods in gnotobiotic animals and undernourished children. Science 365, 6449 . https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aau4732 (2019).

Gough, E. K. et al. Erratum to: Linear growth faltering in infants is associated with Acidaminococcus sp. and community-level changes in the gut microbiota. Microbiome 4, 5. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40168-016-0149-2 (2016).

Shin, S. C. et al. Drosophila Microbiome modulates host developmental and metabolic homeostasis via insulin signaling. Science 334 (6056), 670–674. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1212782 (2011).

The Subspecialty Group of Endocrinologic, Hereditary and Metabolic Diseases, The Society of Pediatrics, Chinese Medical Association. Guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of children with short stature. Chin. J. Pediatr. 46 (6), 428–430. https://doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.issn.0578-1310.2008.06.107 (2008).

Li et al. Height and weight standardized growth charts for Chinese children and adolescents aged 0 to 18 years. Chin. J. Pediatr. 47 (7), 487–442. https://doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.issn.0578-1310.2009.07.003 (2009).

Vonaesch, P. et al. Stunted childhood growth is associated with decompartmentalization of the Gastrointestinal tract and overgrowth of oropharyngeal taxa. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 115 (36), E8489–E98. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1806573115 (2018).

Murray, M. G. & Thompson, W. F. Rapid isolation of high molecular weight plant DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 8 (19), 4321–4325. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/8.19.4321 (1980).

Li, M. et al. Signatures within esophageal microbiota with progression of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Chin. J. Cancer Res. 32 (6), 755–767. https://doi.org/10.21147/j.issn.1000-9604.2020.06.09 (2020).

Kim, B. R. et al. Deciphering diversity indices for a better Understanding of microbial communities. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 27 (12), 2089–2093. https://doi.org/10.4014/jmb.1709.09027 (2017).

Ren, Z. et al. Gut Microbiome analysis as a tool towards targeted non-invasive biomarkers for early hepatocellular carcinoma. Gut 68 (6), 1014–1023. https://doi.org/10.1136/gutjnl-2017-315084 (2019).

Agus, A., Clément, K. & Sokol, H. Gut microbiota-derived metabolites as central regulators in metabolic disorders. Gut 70 (6), 1174–1182. https://doi.org/10.1136/gutjnl-2020-323071 (2021).

Gao, X. et al. A study of the correlation between obesity and intestinal flora in school-age children. Sci Rep. ;8(1):14511. Published 2018 Sep 28. (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-32730-6

Baquero, F. & Nombela, C. The Microbiome as a human organ. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 18 (Suppl 4), 2–4. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-0691.2012.03916.x (2012).

Könönen, E. & Gursoy, U. K. Oral Prevotella species and their connection to events of clinical relevance in Gastrointestinal and respiratory tracts. Front. Microbiol. 12, 798763. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2021.798763 (2022). Published 2022 Jan 6.

Tett, A. et al. Prevotella diversity, niches and interactions with the human host. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 19 (9), 585–599. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41579-021-00559-y (2021).

Coker, M. O. et al. Metagenomic analysis reveals associations between salivary microbiota and body composition in early childhood. Sci. Rep. 12 (1), 13075. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-14668-y (2022).

Janssen, E. M. et al. Analysis of patient preferences in lung Cancer - Estimating acceptable tradeoffs between treatment benefit and side effects. Patient Prefer Adherence. 14, 927–937. https://doi.org/10.2147/PPA.S235430 (2020).

Reyes, L. Porphyromonas gingivalis. Trends Microbiol. 29 (4), 376–377. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tim.2021.01.010 (2021).

Hojo, K. et al. Distribution of salivary Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium species in periodontal health and disease. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 71 (1), 152–157. https://doi.org/10.1271/bbb.60420 (2007).

Donley, C. L. et al. IgG antibody levels to Porphyromonas gingivalis and clinical measures in children. J. Periodontol. 75 (2), 221–228. https://doi.org/10.1902/jop.2004.75.2.221 (2004).

Epping, L., Antão, E. M. & Semmler, T. Population biology and comparative genomics of Campylobacter species. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 431, 59–78. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-65481-8_3 (2021).

Kaakoush, N. O. et al. Global epidemiology of Campylobacter infection. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 28 (3), 687–720. https://doi.org/10.1128/CMR.00006-15 (2015).

Rogawski, E. T. et al. Use of quantitative molecular diagnostic methods to investigate the effect of enteropathogen infections on linear growth in children in low-resource settings: longitudinal analysis of results from the MAL-ED cohort study. Lancet Glob Health. 6 (12), e1319–e28. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30351-6 (2018).

Lee, G. et al. Symptomatic and asymptomatic Campylobacter infections associated with reduced growth in Peruvian children. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 7 (1), e2036. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0002036 (2013).

Sanchez, J. J. et al. Campylobacter infection and household factors are associated with childhood growth in urban bangladesh: an analysis of the MAL-ED study. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 14 (5), e0008328. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0008328 (2020).

Murphy, E. C. & Frick, I. M. Gram-positive anaerobic cocci–commensals and opportunistic pathogens. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 37 (4), 520–553. https://doi.org/10.1111/1574-6976.12005 (2013).

Tall, M. L. et al. Anaerococcus Marasmi sp. nov., a new bacterium isolated from human gut microbiota. New. Microbes New. Infect. 35, 100655. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nmni.2020.100655 (2020).

Djais, A. A. et al. Identification and phylogenetic analysis of oral Veillonella species isolated from the saliva of Japanese children. F1000Res 8, 616. https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.18506.5 (2019).

Theodorea, C. F. et al. Characterization of oral Veillonella species in dental biofilms in healthy and stunted groups of children aged 6–7 years in East Nusa Tenggara. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 19, 21. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192113998 (2022).

Janda, J. M. & Abbott, S. L. The changing face of the family Enterobacteriaceae (Order: Enterobacterales): New Members, Taxonomic Issues, Geographic Expansion, and New Diseases and Disease Syndromes. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 34, 2. https://doi.org/10.1128/CMR.00174-20 (2021).

Gasaly, N., Hermoso, M. A. & Gotteland, M. Butyrate and the Fine-Tuning of colonic homeostasis: implication for inflammatory bowel diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22063061 (2021).

Vallianou, N. et al. Understanding the role of the gut Microbiome and microbial metabolites in Non-Alcoholic fatty liver disease: current evidence and perspectives. Biomolecules 12, 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom12010056 (2021).

Wexler, H. M. Bacteroides: the good, the bad, and the nitty-gritty. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 20 (4), 593–621. https://doi.org/10.1128/CMR.00008-07 (2007).

Zafar, H. & Saier, M. H. Jr Gut Bacteroides species in health and disease. Gut Microbes. 13, 1. https://doi.org/10.1080/19490976.2020.1848158 (2021).

Den Besten, G. et al. The role of short-chain fatty acids in the interplay between diet, gut microbiota, and host energy metabolism. J. Lipid Res. 54 (9), 2325–2340. https://doi.org/10.1194/jlr.R036012 (2013).

Lopez-Siles, M. et al. Faecalibacterium prausnitzii: from microbiology to diagnostics and prognostics. ISME J. 11 (4), 841–852. https://doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2016.176 (2017).

Wu, H. et al. Fucosidases from the human gut symbiont Ruminococcus gnavus. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 78 (2), 675–693. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00018-020-03514-x (2021).

Deering, K. E. et al. Characterizing the composition of the pediatric gut Microbiome. Syst. Rev. Nutrients. 12, 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12010016 (2019).

La Fata, G., Weber, P. & Mohajeri, M. H. Probiotics and the gut immune system: indirect regulation. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins. 10 (1), 11–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12602-017-9322-6 (2018).

Hill, C. et al. Expert consensus document. The international scientific association for probiotics and prebiotics consensus statement on the scope and appropriate use of the term probiotic. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 11 (8), 506–514. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrgastro.2014.66 (2014).

Araújo, M. M. et al. Effects of Bifidobacterium animalis subspecies lactis supplementation on Gastrointestinal symptoms: systematic review with meta-analysis. Nutr. Rev. 80 (6), 1619–1633. https://doi.org/10.1093/nutrit/nuab109 (2022).

Inoue, Y. & Shimojo, N. Microbiome/microbiota and allergies. Semin Immunopathol. 37 (1), 57–64. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00281-014-0453-5 (2015).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all participants for participating in this clinical trial.

Funding

This study was funded by the 2023 Horizontal Project (23H0527) of Sichuan University in China and the 2021 Basic Research Project (HLBKJ202121) of the Nursing Department of West China Second Hospital of Sichuan University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Qin Zeng design research, collect fecal samples, conduct data analysis, and draft manuscripts; Yanling Hu and Jing Chen assist in collecting fecal samples; Xianqiong Feng, Shaoyu Su and Bi Ru Luo designed research, obtained funding, and provided supervision.All authors have made significant contributions to the knowledge content of the paper and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics statement

The study was approved by the Ethical Committee of the West China Second Hospital of Sichuan University (2022110). All methods were performed consistent with the relevant guidelines and regulations of the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients for being included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zeng, Q., Feng, X., Hu, Y. et al. Dysbiosis of gut microbiota with enriched pro-inflammatory species in children with idiopathic short stature: a case-control study. Sci Rep 15, 19779 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-04569-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-04569-1