Abstract

Risk factors and reasons for romosozumab nonadherence remain unclear. This study compared patients who adhered to romosozumab therapy with those who did not to identify possible risk factors and reasons for treatment nonadherence. This case-control study included all eligible patients diagnosed with osteoporosis who received romosozumab therapy at our hospital between February 2022 and March 2024. The patients were divided into adherence and nonadherent groups. Nonadherence was defined as failure to follow the monthly injection schedule for 12 injections over a one-year period, without transitioning to other antiosteoporotic medications. Relevant data were retrospectively collected from the patients’ medical records. Univariate and logistic regression analyses were performed to identify the associations of patient characteristics with romosozumab nonadherence. A subgroup analysis was performed to identify the associations between the reasons for nonadherence and the type of payment for romosozumab therapy. The adherence and nonadherent groups comprised 62 and 69 patients, respectively. Male patients had a 9.03-fold higher risk of nonadherence than did female patients (P = .041). Self-payment for medications was associated with a 2.756-fold higher risk of nonadherence than was receiving a full subsidy (P = .024). The most common reasons for nonadherence were patient-related factors (87.0%, 60 of the 69 patients in the nonadherent group), followed by medicine-related factors (8.7%, 6 patients) and health system–related factors (4.3%, 3 patients). Male sex and self-payment for medications are risk factors for romosozumab nonadherence. Patient-related factors appear to be the most common reasons for nonadherence. These results can aid healthcare providers in implementing appropriate interventions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Romosozumab is a sclerostin antibody used for treating osteoporosis. Its mechanism of action differs from those of conventional medications. Bisphosphonates and receptor activator of nuclear factor-κB ligand inhibitors primarily function by inhibiting bone resorption, whereas teriparatide focuses solely on promoting bone growth. By contrast, romosozumab exhibits a dual mechanism of action by simultaneously promoting bone formation and inhibiting bone resorption. This dual action substantially increases bone mineral density within a short period1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12. Clinical trials have demonstrated the efficacy and safety of romosozumab in the treatment of osteoporosis3,13,14,15,16,17. After 12 months of romosozumab therapy in postmenopausal women, rapid reductions were observed in the risks of vertebral, clinical, and nonvertebral fractures; these risks decreased by 73%, 36%, and 25%, respectively, in the treatment group compared with corresponding risks in the placebo group18.

In the treatment of osteoporosis, patient adherence is essential for ensuring that medications exert their optimal effects. Previous studies have identified numerous factors affecting treatment adherence—for example, treatment cost, drug side effects, drug administration methods, patients’ understanding of the disease and their expectations from treatment, access to health-care facilities, family support, patients’ disease- and treatment-related perceptions, physical and mental functions, education levels, medical history, and comorbidities19,20,21,22,23. For romosozumab therapy, 12 consecutive monthly injections is recommended, requiring patients to visit the clinic once every month. Furthermore, because of the strict criteria for full subsidy under Taiwan’s National Health Insurance (NHI) scheme, many patients have to bear the cost of romosozumab therapy by themselves.

With the increasing use of romosozumab since 2019, identifying potential risk factors for nonadherence and implementing preventive measures have become crucial. To the best of our knowledge, no previous studies have analyzed the characteristics of patients nonadherent to romosozumab therapy. Thus, in this study, we compared patients adherent to romosozumab therapy with those who are not to identify risk factors and reasons for nonadherence. We hypothesized that romosozumab cost subsidies and recent histories of fracture and orthopedic surgery would be associated with adherence. Patients who pay for the medications by themselves would exhibit increased adherence. Furthermore, patients with a history of fracture or orthopedic surgery, either recently or during romosozumab therapy, would be vigilant regarding their bone health, with their physicians likely exhibiting increased attentiveness. Identifying the reasons for romosozumab nonadherence may enable health-care providers to better address patient needs, improve treatment adherence, and optimize clinical outcomes.

Materials and methods

Study design and ethical considerations

This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. The study design was approved by Ditmanson Medical Foundation Chia-Yi Christian Hospital institutional review board (approval no.: 2024056). The requirement for informed consent was waived by Ditmanson Medical Foundation Chia-Yi Christian Hospital institutional review board because of the retrospective nature of this study.

Patients

This case-control study included all eligible patients diagnosed with osteoporosis based on clinical assessment, who received at least one dose of romosozumab therapy at our hospital between February 2022 and March 2024. The patients were stratified by adherence to adherent group (patients who either completed 12 doses of romosozumab or transitioned to other antiosteoporotic medications before completing 12 doses) and nonadherent group (patients who did not follow the monthly injection schedule for romosozumab and did not transition to anti-resorptive medications). Notably, patients who had insufficient follow-up time to complete 12 doses were excluded from this study. To determine adherence, a refill gap of up to 14 days was allowed between two consecutive injections. Before initiating romosozumab therapy, patients underwent clinical evaluation for cardiovascular conditions, and high-risk individuals were not prescribed romosozumab based on physician judgment.

Data collection

Relevant data were collected from the patients’ electronic medical records (Ditmanson Research Database) and included information on patient age, sex, bone mass density (T-score, the lowest value among the lumbar spine L1–L4, total hip, or femoral neck), type of payment for romosozumab therapy (full subsidy under the NHI scheme or self-payment), history of fracture within one year before romosozumab therapy, history of orthopedic surgery (general, spine, or arthroplasty) within one year before or during romosozumab therapy, number of doses completed, and reasons for nonadherence. In addition, adverse events associated with romosozumab therapy were recorded.

Raw data on reasons for discontinued romosozumab doses were collected through unstructured responses during the follow-up period. Then we categorized these answers into 10 items across 3 domains. The first domain, patient-related factors, included the following reasons: (1) the patient or family members perceived no major changes after treatment; (2) the patient forgot to attend follow-up appointments; (3) the patient continued antiosteoporotic treatments at another hospital; (4) the patient faced logistical challenges, such as time and distance constraints, in returning for appointments; (5) the patient was receiving treatment for other diseases, such as dental procedure; and (6) the patient expired. The second domain, medicine-related factors, included the following reasons: (1) the patient experienced adverse events after romosozumab injection—for example, cardiovascular events, hypersensitivity, hypocalcemia, osteonecrosis of the jaw, atypical subtrochanteric and femoral shaft fractures, fatigue, arthralgia, and injection site reactions (pain, swelling, and redness) and (2) the patient was financially unable to afford romosozumab therapy. The third domain, health system–related factors, included the following reasons: (1) the physician did not remind the patient to continue treatment and (2) the physician deemed further treatment unnecessary.

To mitigate the effect of reporting bias from economic factors on adherence, before romosozumab therapy, the patients were thoroughly informed about the consecutive 12-dose course and provided with the option to switch to alternative osteoporosis treatments during the treatment course.

Statistical analysis

Patient characteristics were compared between the adherence and nonadherent groups to identify potential risk factors. Between-group differences in continuous and categorical variables were assessed using the t, Mann-Whitney U, or chi-square test. Logistic regression analysis was performed to calculate odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the identified risk factors. Factors that were nonsignificant in the univariate analysis were still included in the multivariate analysis to adjust for potential confounders. Because T-score data were missing for five patients in the nonadherent group, T-scores were excluded from the logistic regression model. Age was categorized into four subgroups (< 60, 60 to 69, 70 to 79, and ≥ 80 year) to investigate the association between age and romosozumab nonadherence. Furthermore, a subgroup analysis was performed for nonadherent patients to identify the associations of the three domains of reasons for nonadherence with the type of payment for romosozumab therapy. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (version 28.0.1.0; IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

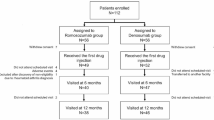

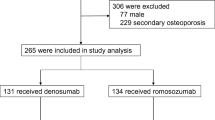

Between February 2022 and March 2024, we enrolled 221 patients who received romosozumab therapy. After the exclusion of patients with insufficient follow-up time to complete 12 doses, 131 patients were included in the final analysis. The adherence and nonadherent groups comprised 62 and 69 patients, respectively (Fig. 1). Among the 62 patients in the adherent group, 29 (46.8%) transitioned to other anti-resorptive agents, including denosumab (Prolia) or ibandronate (Bonviva), during the course of romosozumab therapy, based on physician judgment. Table 1 presents the baseline characteristics of the study groups. The nonadherent group had significantly higher proportions of men and patients who self-paid for romosozumab compared to the adherent group.

Regarding adverse events, five patients (3.8%) had pain and swelling at the injection site but required no interventions for these problems. All of these five patients were in the nonadherent group. Three (2.3%) patients had new fractures in the thoracic spine during romosozumab therapy. One patient who had discontinued treatment after two doses sustained a new fracture 100 days after the first injection. This patient had an initial T-score of -1.6 and a history of multiple lumbar spine surgeries. Serial radiographs revealed progressive bone loss over time, supporting the decision to initiate anti-osteoporotic treatment. Furthermore, two adherent patients sustained new fractures on the 33rd and 97th days after the first injection, with initial T-scores of -4.7 and − 2.2, respectively. Both of these patients had a history of compression fractures in the thoracic and lumbar spine.

Associations between patient characteristics and romosozumab nonadherence were investigated using a logistic regression model; the results are presented in terms of crude and adjusted ORs (Table 2). The model included age, sex, type of payment for romosozumab therapy, history of fracture before romosozumab therapy, and history of orthopedic surgery before and during romosozumab therapy. The risk of nonadherence was 9.03-fold higher in men than in women. Self-payment for medications was associated with a 2.756-fold higher risk of nonadherence than was receiving a full subsidy under the NHI scheme. No significant association was observed between romosozumab nonadherence and a history of fracture or orthopedic surgery.

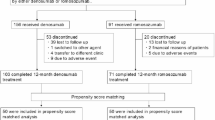

Romosozumab nonadherence occurred most commonly after the first dose, regardless of whether the medication was fully subsidized or self-paid (Fig. 2). The percentage of adherence for each dose was relatively high in the full subsidy cohort. Figure 3 presents the reasons for nonadherence. The distributions of these reasons were similar between the full subsidy and self-payment cohorts. The most common reason for nonadherence was forgetting to attend follow-up appointments, followed by patients or their family members perceiving no major changes after treatment. Patient-related factors emerged as the primary reasons for nonadherence in both groups. No significant association was observed between the three domains of reasons for nonadherence and the type of payment for romosozumab therapy.

Discussion

We found self-payment for romosozumab and male sex to be significant risk factors for nonadherence. Most patients discontinued treatment after the first dose. The primary reasons for romosozumab nonadherence were patient-related factors, accounting for > 80% of all cases.

The association between subsidized medications and adherence has been demonstrated in previous studies. Two out of three studies showed a positive relationship between full subsidy and adherence, supporting our findings of a similar positive association24,25. Although one study reported no significant difference in adherence between subsidized and self-paying cohorts26, the overall evidence highlights the potential impact of subsidized medications on improving adherence. Another study on osteoporosis therapy reported increased persistence in patients with insurance coverage during the first year of treatment but not in the second year, suggesting a short-term positive effect of treatment coverage on adherence27. In the present study, patients were eligible for full subsidies for romosozumab therapy if they met the following criteria: (1) postmenopausal women with a T-score below − 3 who had sustained two or more fractures in the spine or hip or (2) patients who were unable to tolerate side effects or who developed at least one new fracture despite the continuous use of antiresorptive agents for at least 12 consecutive months. The risk of nonadherence was significantly higher in the self-payment cohort than in the full subsidy cohort in this study. The discrepancy between our findings and those of other studies may be attributable to differences in patient populations, medications, diseases, and economic factors. In the present study, only one patient cited financial inability as the reason for nonadherence. Therefore, the cost of romosozumab therapy may not be the primary risk factor for nonadherence. However, the possibility of a reporting bias cannot be ignored because financial problems are sensitive topics and may be underreported. Furthermore, we found that nonadherence occurred most commonly after the first dose, particularly among self-paying patients. Contrary to our hypothesis, self-paying patients did not exhibit high levels of motivation to continue treatment. Therefore, effective communication and patient education are needed to prevent early discontinuation of romosozumab therapy.

Sex may influence the risk of nonadherence among self-paying patients; in our study, all male patients paid for romosozumab therapy by themselves. Of the 14 men included in this study, 13 were nonadherent. Age was similar between these 13 men (10 of 13 patients were ≥ 70 years old, 76.9%) and nonadherent patients. Among the 13 nonadherent men, one patient (7.7%) had a history of fracture before romosozumab therapy, four (30.8%) had a history of orthopedic surgery before romosozumab therapy, and three (23.1%) had a history of orthopedic surgery during romosozumab therapy. The average T-score was high at − 2.9 ± 0.9. The most common reasons for nonadherence among these men were patient-related factors, accounting for nonadherence in 10 patients (76.7% [10/13]); this result is consistent with the overall findings for all nonadherent patients. Because of the limited number of male patients in this study, a subgroup analysis by sex could not be performed. Several studies have reported that male patients are less likely than female patients to adhere to osteoporosis therapy28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36. However, some studies have concluded otherwise37,38. Therefore, further studies are needed to confirm the association between male sex and poor adherence to osteoporosis therapy. Our findings indicate that improving medication adherence in men should follow the same approach as that adopted for other patients. The focus should be on establishing effective communication regarding treatment goals.

A systematic review indicated that whether a history of falls and fractures is associated with poorer adherence to osteoporosis therapy remains unclear23. Our findings did not support the hypothesis that patients with a history of fracture before romosozumab therapy and those with a history of orthopedic surgery before or during romosozumab therapy would be highly motivated to adhere to osteoporosis therapy. The inconsistency in results among previous studies may be attributable to differences in factors associated with adherence and the full models used for regression analysis. Current evidence indicates there are risk factors more significant than a history of falls and fractures; such risk factors should be addressed through targeted interventions.

Our findings indicated that the risk of romosozumab nonadherence generally decreased with the increasing number of completed doses. However, after the sixth dose, the patients were likely to discontinue therapy, likely because of their perceptions of the treatment outcomes. Before initiating romosozumab therapy, we inform our patients regarding its rapid effects on bone mass density; lumbar spine bone mass density increases by 7.2% and 9.8% within 6 and 12 months, respectively, after the initiation of this therapy16. Thus, some patients and their family members believe that six doses are sufficient and that completing the remaining six doses is not cost-effective. In some cases, patients even refuse to transition to other antiosteoporotic medications. Thus, clinicians must ensure that patients, particularly older patients, and their family members fully understand the treatment goals and the optimal duration of therapy. Although we found no association between age and nonadherence, older patients often require additional family support, indicating the importance of family involvement in ensuring treatment adherence. Many patients and their family members expressed frustration over the absence of noticeable improvement in bone density immediately after treatment. Regular bone density examinations may help address this problem. However, the wait time for dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry can range from days to weeks, requiring patients to schedule additional appointments. Furthermore, patients may need to bear the cost of these examinations, which can further reduce their willingness to comply with treatment. These factors may ultimately increase the risk of nonadherence to osteoporosis therapy. Optimizing the scheduling process for bone density examinations and providing financial subsidies for these examinations should be considered to enhance adherence.

In the present study, the most common reason for nonadherence was forgetting to attend follow-up appointments. This problem may be resolved through osteoporosis liaison services, which can enhance adherence by implementing active and regular monitoring programs39. Health system–related factors can be improved through similar approaches. Members of the health-care team can address any points that the physician might have overlooked during the treatment process, thereby ensuring effective collaboration.

A study investigating the incidence of adverse events in 230 patients after romosozumab treatment reported a total of 64 adverse events in the study cohort (27.8%)40. Injection site reactions constituted the most common adverse event (32 of 230 patients, 13.9%). In our study, adverse events were observed in five patients (3.8%), all of whom developed injection site reactions. The lower incidence of adverse events in our study than in the aforementioned study may be attributable to differences in definitions: the previous study reported > 20 types of adverse events, not all of which were directly associated with romosozumab. Because older patients often have multiple comorbidities, determining whether an adverse event is specifically associated with romosozumab therapy is challenging. Therefore, the incidence of adverse events might have been underestimated in our study. Although adverse events can reduce patients’ willingness to continue treatment, they are difficult to predict and can only be addressed with increased monitoring during follow-up. Physicians should ensure that treatment options and potential risks are thoroughly communicated to patients.

The association between receiving concomitant treatments for comorbidities and adherence remains unclear. However, certain comorbidities have been associated with adherence—for example, hepatobiliary and liver diseases, malabsorption syndrome, digestive disorders, inflammatory bowel disease, celiac disease, mucositis, arthrosis, osteopenia, metabolic bone disease, chronic pulmonary disease, and collagen diseases23. In our study, eight patients discontinued osteoporosis therapy because of concomitant treatments for other diseases. Among them, four patients discontinued treatment for dental procedures because dentists exercise additional caution when managing patients receiving antiosteoporotic medications. Therefore, before initiating osteoporosis therapy, clinicians must confirm their patients’ comorbidities and communicate effectively regarding treatment goals and considerations.

Reporting bias might have influenced the investigation of reasons for nonadherence because patients might have been hesitant to disclose sensitive reasons (e.g., financial difficulties), leading to the underestimation of the effect of economic factors on adherence. To address this issue, we ensured that patients were clearly informed in advance about the expected duration and cost of romosozumab treatment. For self-paying patients, this early discussion allowed them to assess their financial readiness in advance, which likely reduced the likelihood that economic factors contributed to nonadherence.

Our results may be generalizable to patients receiving romosozumab therapy. However, some limitations of our study should be considered. First, investigating the association between specific reasons of nonadherence and patient characteristics was difficult because of the limited number of nonadherent patients. Second, certain personal and sensitive factors, such as education level, income, and distance between the patient’s residence and the hospital, were not analyzed in this study, which might have introduced an omitted variable bias. Third, although we investigated the association between subsidized medications and adherence, a risk of bias persists because subsidies may not accurately reflect the effect of socioeconomic status. Fourth, accessibility to health care is essential for treatment adherence; however, the risk of bias related to patient location appeared to be low in this study. Only two patients reported difficulties in returning for appointments; therefore, distance between the patient’s residence and the hospital is not the primary reason for nonadherence. Fifth, although many potential risk factors for nonadherence to osteoporosis therapy have been reported previously, we included only some of them, which might have introduced bias due to unaccounted confounders. Sixth, in the adherent group, some patients were excluded from the analysis because their follow-up duration was insufficient to complete the full 12 doses of romosozumab treatment. Seventh, the effect of male sex on romosozumab nonadherence remains unclear, necessitating large-scale studies involving male patients. Eighth, we were unable to include patients’ prior osteoporosis treatments in our analysis. Some patients had received osteoporosis care at other institutions, making it difficult to accurately verify their previous medication history. This limitation may have affected our ability to assess the potential influence of prior treatments, such as bisphosphonates, on adherence. Finally, in this study, we did not create a separate semi-adherent group, primarily because the transition to other anti-resorptive medications was driven by medical necessity rather than non-compliance with romosozumab treatment. Given that romosozumab is typically prescribed for a 12-month course, transitioning to another anti-resorptive therapy is considered part of standard clinical practice rather than nonadherence. Therefore, these patients were included in the adherent group to better reflect appropriate continuation of osteoporosis management. Subdividing the groups could have further reduced sample sizes, potentially compromising the stability of statistical analyses. Therefore, we believe that maintaining the current binary classification (adherence vs. nonadherence) allows for a more accurate assessment of the study’s primary objective—identifying the risk factors and reasons for nonadherence.

Conclusion

Our findings suggest that male sex and self-payment for medications increase the risk of romosozumab nonadherence. Regardless of sex or payment type, the primary reasons for treatment discontinuation are patient-related factors. Effective communication between patients and clinicians as well as active monitoring programs may improve adherence to romosozumab therapy. Although some potential risk factors which may associated with nonadherence were not analyzed in the present study, it is not always feasible to collect such detailed data from patients in clinical practice, particularly sensitive personal information such as socioeconomic status and place of residence. Overall, our findings clarify the reasons for romosozumab nonadherence and may aid health-care providers in implementing appropriate interventions.

Data availability

The dataset used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Boyce, R. W., Niu, Q. T. & Ominsky, M. S. Kinetic reconstruction reveals time-dependent effects of Romosozumab on bone formation and osteoblast function in vertebral cancellous and cortical bone in cynomolgus monkeys. Bone 101, 77–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bone.2017.04.005 (2017).

Kim, S. W. et al. Sclerostin antibody administration converts bone lining cells into active osteoblasts. J. Bone Min. Res. 32, 892–901. https://doi.org/10.1002/jbmr.3038 (2017).

McClung, M. R. et al. Romosozumab in postmenopausal women with low bone mineral density. N Engl. J. Med. 370, 412–420. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1305224 (2014).

Nioi, P. et al. Transcriptional profiling of laser capture microdissected subpopulations of the osteoblast lineage provides insight into the early response to sclerostin antibody in rats. J. Bone Min. Res. 30, 1457–1467. https://doi.org/10.1002/jbmr.2482 (2015).

Ominsky, M. S., Boyce, R. W., Li, X. & Ke, H. Z. Effects of sclerostin antibodies in animal models of osteoporosis. Bone 96, 63–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bone.2016.10.019 (2017).

Ominsky, M. S. et al. Differential Temporal effects of sclerostin antibody and parathyroid hormone on cancellous and cortical bone and quantitative differences in effects on the osteoblast lineage in young intact rats. Bone 81, 380–391. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bone.2015.08.007 (2015).

Ominsky, M. S., Niu, Q. T., Li, C., Li, X. & Ke, H. Z. Tissue-level mechanisms responsible for the increase in bone formation and bone volume by sclerostin antibody. J. Bone Min. Res. 29, 1424–1430. https://doi.org/10.1002/jbmr.2152 (2014).

Ominsky, M. S. et al. Two doses of sclerostin antibody in cynomolgus monkeys increases bone formation, bone mineral density, and bone strength. J. Bone Min. Res. 25, 948–959. https://doi.org/10.1002/jbmr.14 (2010).

Taylor, S. et al. Time-dependent cellular and transcriptional changes in the osteoblast lineage associated with sclerostin antibody treatment in ovariectomized rats. Bone 84, 148–159. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bone.2015.12.013 (2016).

Baron, R. & Kneissel, M. WNT signaling in bone homeostasis and disease: from human mutations to treatments. Nat. Med. 19, 179–192. https://doi.org/10.1038/nm.3074 (2013).

Sølling, A. S. K., Harsløf, T. & Langdahl, B. The clinical potential of Romosozumab for the prevention of fractures in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. Ther. Adv. Musculoskelet. Dis. 10, 105–115. https://doi.org/10.1177/1759720x18775936 (2018).

Padhi, D., Jang, G., Stouch, B., Fang, L. & Posvar, E. Single-dose, placebo-controlled, randomized study of AMG 785, a sclerostin monoclonal antibody. J. Bone Min. Res. 26, 19–26. https://doi.org/10.1002/jbmr.173 (2011).

Kendler, D. L. et al. Bone mineral density gains with a second 12-month course of Romosozumab therapy following placebo or denosumab. Osteoporos. Int. 30, 2437–2448. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-019-05146-9 (2019).

Cosman, F. et al. Romosozumab FRAME study: A post hoc analysis of the role of regional background fracture risk on nonvertebral fracture outcome. J. Bone Min. Res. 33, 1407–1416. https://doi.org/10.1002/jbmr.3439 (2018).

Saag, K. G. et al. Romosozumab or alendronate for fracture prevention in women with osteoporosis. N Engl. J. Med. 377, 1417–1427. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1708322 (2017).

Langdahl, B. L. et al. Romosozumab (sclerostin monoclonal antibody) versus teriparatide in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis transitioning from oral bisphosphonate therapy: a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet 390, 1585–1594. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(17)31613-6 (2017).

Lewiecki, E. M. et al. A phase III randomized Placebo-Controlled trial to evaluate efficacy and safety of Romosozumab in men with osteoporosis. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 103, 3183–3193. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2017-02163 (2018).

Cosman, F. et al. Romosozumab treatment in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. N Engl. J. Med. 375, 1532–1543. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1607948 (2016).

DiMatteo, M. R. Social support and patient adherence to medical treatment: a meta-analysis. Health Psychol. 23, 207–218. https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-6133.23.2.207 (2004).

Horne, R. & Weinman, J. Patients’ beliefs about prescribed medicines and their role in adherence to treatment in chronic physical illness. J. Psychosom. Res. 47, 555–567. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0022-3999(99)00057-4 (1999).

Nieuwlaat, R. et al. Interventions for enhancing medication adherence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. Cd000011, (2014). https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD000011.pub4 (2014).

Osterberg, L. & Blaschke, T. Adherence to medication. N Engl. J. Med. 353, 487–497. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra050100 (2005).

Yeam, C. T. et al. A systematic review of factors affecting medication adherence among patients with osteoporosis. Osteoporos. Int. 29, 2623–2637. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-018-4759-3 (2018).

Batavia, A. S. et al. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy in patients participating in a graduated cost recovery program at an HIV care center in South India. AIDS Behav. 14, 794–798. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-009-9663-6 (2010).

Sears, C. L., Lewis, C., Noel, K., Albright, T. S. & Fischer, J. R. Overactive bladder medication adherence when medication is free to patients. J. Urol. 183, 1077–1081. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.juro.2009.11.026 (2010).

Aziz, H. et al. A comparison of medication adherence between subsidized and self-paying patients in Malaysia. Malays Fam Physician. 13, 2–9 (2018).

Yu, S. F. et al. Non-adherence to anti-osteoporotic medications in taiwan: physician specialty makes a difference. J. Bone Min. Metab. 31, 351–359. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00774-013-0424-2 (2013).

Hansen, C., Pedersen, B. D., Konradsen, H. & Abrahamsen, B. Anti-osteoporotic therapy in Denmark–predictors and demographics of poor refill compliance and poor persistence. Osteoporos. Int. 24, 2079–2097. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-012-2221-5 (2013).

Yun, H. et al. Patterns and predictors of osteoporosis medication discontinuation and switching among medicare beneficiaries. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 15, 112. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2474-15-112 (2014).

Tanaka, I. et al. Adherence and persistence with once-daily teriparatide in japan: a retrospective, prescription database, cohort study. J. Osteoporos. 2013 (654218). https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/654218 (2013).

García-Sempere, A. et al. Primary and secondary non-adherence to osteoporotic medications after hip fracture in spain. The PREV2FO population-based retrospective cohort study. Sci. Rep. 7, 11784. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-10899-6 (2017).

Ideguchi, H., Ohno, S., Takase, K., Ueda, A. & Ishigatsubo, Y. Outcomes after switching from one bisphosphonate to another in 146 patients at a single university hospital. Osteoporos. Int. 19, 1777–1783. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-008-0618-y (2008).

Curtis, J. R., Yun, H., Matthews, R., Saag, K. G. & Delzell, E. Adherence with intravenous zoledronate and intravenous ibandronate in the united States medicare population. Arthritis Care Res. (Hoboken). 64, 1054–1060. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.21638 (2012).

Casula, M. et al. Assessment and potential determinants of compliance and persistence to antiosteoporosis therapy in Italy. Am. J. Manag Care. 20, e138–145 (2014).

Lee, Y. K., Nho, J. H., Ha, Y. C. & Koo, K. H. Persistence with intravenous zoledronate in elderly patients with osteoporosis. Osteoporos. Int. 23, 2329–2333. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-011-1881-x (2012).

Sheehy, O., Kindundu, C. M., Barbeau, M. & LeLorier, J. Differences in persistence among different weekly oral bisphosphonate medications. Osteoporos. Int. 20, 1369–1376. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-008-0795-8 (2009).

Curtis, J. R. et al. Improving the prediction of medication compliance: the example of bisphosphonates for osteoporosis. Med. Care. 47, 334–341. https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0b013e31818afa1c (2009).

Kyvernitakis, I., Kostev, K., Kurth, A., Albert, U. S. & Hadji, P. Differences in persistency with teriparatide in patients with osteoporosis according to gender and health care provider. Osteoporos. Int. 25, 2721–2728. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-014-2810-6 (2014).

Chang, C. B. et al. One-year outcomes of an osteoporosis liaison services program initiated within a healthcare system. Osteoporos. Int. 32, 2163–2172. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-021-05859-w (2021).

Kobayakawa, T. et al. Real-world effects and adverse events of Romosozumab in Japanese osteoporotic patients: A prospective cohort study. Bone Rep. 14, 101068. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bonr.2021.101068 (2021).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the help from the Clinical Data Center, Ditmanson Medical Foundation Chia-Yi Christian Hospital for providing administrative and technical support. This study is based in part on data from the Ditmanson Research Database (DRD) provided by Ditmanson Medical Foundation Chia-Yi Christian Hospital. The interpretation and conclusions contained herein do not represent the position of Ditmanson Medical Foundation Chia-Yi Christian Hospital. The authors appreciate the assistance of the case managers (H.-Y. C., Y.-C. H., C.-H. T., Y.-C. L., H.-Y. W., C.-L. L.) at Chia-Yi Christian Hospital in data collection.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, C.-Y. W and Y.-C. C.; methodology, C.-Y. W, C.-H. L., Y.-S. Y. and Y.-C. C.; formal analysis, C.-H. L.; investigation, C.-H. L and Y.-S. D.; writing—original draft preparation, T.-C. T.; writing—review and editing, C.-Y. W, Y.-S. Y., C.-H. L, Y.-C. C. and C.-H. C.; supervision, C.-Y. W.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

This study was approved by Ditmanson Medical Foundation Chia-Yi Christian Hospital institutional review board (approval no. 2024056). Patient consent was waived by Ditmanson Medical Foundation Chia-Yi Christian Hospital institutional review board due to the retrospective study design.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tsai, TC., Yen, YS., Lin, CH. et al. Risk factors and reasons for romosozumab nonadherence in a case-control study. Sci Rep 15, 22548 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-04595-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-04595-z