Abstract

Growing concerns about pollution caused by industrial and agricultural wastes have increased interest in converting waste materials into useful products. Bacterial nanocellulose has garnered global interest due to its environmentally friendly production, excellent mechanical properties, and biocompatibility, making it a promising material for various industries. This study explores the production of bacterial nanocellulose (BNC) by Bacillus strains utilizing fruit waste as a sustainable carbon source. Six potential BNC-producing Bacillus strains were isolated and identified. Among them, Bacillus haynesii showing the highest BNC productivity. A Box-Behnken experimental design was employed to optimize cost-effective technique for BNC production. Key factors like temperature, date waste extract percentage, and initial pH level influencing bacterial cellulose production by Bacillus haynesii were optimized. The highest BNC productivity with a value of 2.6 g/L was obtained under optimized conditions of 29 °C, 15% date waste extract, and pH 6. The glass transition temperature of the bacterial nanocellulose ranged from 21.51 to 42.06 °C, with a low negative charge for colloidal stability. Moreover, crystal violet elimination experiments revealed efficient dye removal (84.7%) with adsorbent concentrations of 2 mg/L and a contact time of 60 min. This study concluded that the Bacillus haynesii 9.1AP strain is a promising candidate for sustainable BNC production. To the best of our knowledge, this study represents the initial documentation of Bacillus haynesii’s capability for BNC production, highlighting its potential in environmental and industrial applications, particularly in dye adsorption.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The field of biotechnology provides a robust platform for developing innovative materials, including bacterial nanocellulose (BNC), also known as microbial or bacterial cellulose. This biodegradable extracellular polysaccharide is primarily biosynthesized by acetic acid bacteria1. Due to its outstanding physical and chemical properties—such as eco-friendly synthesis, high mechanical strength, hydrophilicity, superior biocompatibility, and complete biodegradability, BNC has attracted substantial scientific attention over recent decades2. First discovered in 1886, BNC has consistently fascinated researchers owing to its unique structural and functional features. Unlike plant cellulose, BNC exhibits significantly higher degrees of polymerization and crystallinity, typically associated with cellulose type Iα, reaching crystallinity levels as high as 90%. Additionally, its surface is rich in hydroxyl groups, imparting strong hydrophilic characteristics. One of its most distinctive features is its nanofiber diameter, ranging from 20 to 80 nm, which is considerably smaller than most natural or synthetic fibers and enhances its functional versatility3. BNC exhibits remarkable potential across multiple sectors, including textiles, food products, fiber-based paper, packaging, bionanocomposites, and biomedical engineering4. Its biosynthesis is predominantly attributed to acetic acid bacteria5. While several Gram-negative, non-pathogenic bacterial genera, including Xanthococcus, Azotobacter, Pseudomonas, Aerobacter, Rhizobium, and Alcaligenes, have been documented to produce extracellular nanocellulose, the most prolific BNC producers reside within the genus Komagataeibacter (formerly known as Acetobacter or commonly referred to as acetic acid bacteria). On the other hand, only a small number of species, such as Bacillus sp6, Bacillus licheniformis strain ZBT27, Bacillus tequilensis strain SEE-128, B. amyloliquefaciens ZF-79, Leifsonia sp.10, Lactobacillus hilgardii IITRKH15911, Rhodococcus sp. MI-212 have been reported to biosynthesize BNC as considerable efforts have been directed at isolating high-yield BNC-producing strains for industrial applications13.

The culture medium is a critical factor influencing the overall cost of BNC production. As such, one of the key research directions involves identifying inexpensive, nutrient-rich media that can maximize BNC yields while minimizing production costs. Optimal BNC production occurs in media rich in carbon sources such as glucose, fructose, or sucrose, with limited nitrogen content, and under acidic pH (approximately 4.0–6.0) and moderate temperatures (28–30 °C). Oxygen availability is crucial, as BNC synthesis is an aerobic process, typically occurring at the air–liquid interface in static cultures14. The commonly used Hestrin and Schramm (HS) medium, developed in 1954, incorporates glucose (2%) as its primary carbon source15. However, due to the high cost of glucose, the HS medium is impractical for commercial-scale production and contributes significantly to the final product cost16. In recent years, extensive research has focused on optimizing bacterial nanocellulose (BNC) production by refining fermentation parameters and employing cost-effective carbon sources, such as sugarcane, molasses, sucrose, and fruit-derived wastes17. Among these, fruit peels have garnered particular interest due to their abundance of cellulose, hemicellulose, phenolics, and essential nutrients, making them ideal substrates for microbial fermentation18,19. Traditionally disposed of through environmentally harmful methods that contribute to greenhouse gas emissions, fruit peels present a dual opportunity for waste valorization and sustainable BNC production. Despite the promising properties of BNC, large-scale application remains constrained by high production costs and limited yields. Thus, the utilization of agro-industrial residues represents a strategic approach to improve the economic and environmental feasibility of BNC-based technologies20.

Bacterial nanocellulose exhibits exceptional mechanical strength, flexibility, and chemical modifiability, making it a suitable candidate for wastewater treatment applications. In the textile industry alone, over 10,000 types of dyes are used, with approximately 12% of dye lost during production and 20% of that ultimately entering aquatic systems as industrial effluent21. Many of these dyes, along with associated heavy metals, are toxic, carcinogenic, mutagenic, non-biodegradable, and teratogenic, posing significant threats to aquatic ecosystems and public health22,23. Therefore, the removal of such contaminants from wastewater streams is both urgent and essential24. Nanocellulose-based materials are emerging as high-performance biosorbents for water purification due to their advantageous characteristics, including high surface area, modifiable surfaces, eco-compatibility, and reusability25. Current research focuses on enhancing these materials’ performance through strategies such as polymer grafting, surface functionalization, and the synthesis of hybrid composites26. These modifications aim to optimize adsorption capacity and mechanism diversity for efficient contaminant removal. Additionally, efforts are underway to develop BNC-based adsorbents in scalable formats, including membranes, hydrogels, flocculants, and magnetically separable composites for industrial-scale water treatment23,27.

Crystal violet, a widely used cationic triphenylmethane dye, finds applications in leather processing, fabric dyeing, biological staining, veterinary medicine, and the food industry28. However, excessive exposure in humans can lead to serious health complications such as tachycardia, tetraplegia, ocular irritation, and irreversible damage to the corneal epithelium29. Thus, efficient removal of crystal violet from water systems is essential. Various remediation strategies, such as electrochemical degradation, microbial bioremediation, coagulation, membrane separation, advanced oxidation, and photocatalysis, have been explored30. Nevertheless, adsorption stands out for its operational simplicity, cost-effectiveness, high efficiency, and adaptability31,32. Consequently, the present study aims to establish the extensive occurrence of BNC production in Bacillus strains with superior properties and highly potent nanocellulose output. To enhance efficient and cost-effective production techniques by utilizing cheap food industry by-product wastes and plant residue, including dates, oranges, and apple peel wastes as a carbon source to obtain maximum bacterial nanocellulose to meet the demand in diverse applications. In addition, it will explore the structure, purity, and characteristics of the obtained bacterial nanocellulose and its potential in crystal violet elimination from aqueous solutions as an example of a dye used in various applications.

Materials and methods

All chemicals and media used in this study were of analytical grade. Unless otherwise specified, reagents were procured from Merck, with glucose and sodium hydroxide (NaOH) obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. Bacteria were isolated from fresh, semi-dried, and dried fruits, and fruit peels were obtained from local Jeddah stores in Saudi Arabia. The samples were prepared and stored aseptically at 4 °C until they were required for additional experiments.

A modified Hestrin and Schramm (HS) medium, previously described33, served as the primary culture medium for isolating and screening bacteria from various samples. It consisted of (g/L): glucose (20), yeast extract (5), peptone (5), Na2HPO4·7H2O (2.7), and citric acid. (1.15). To promote bacterial nanocellulose (BNC) production by the isolates, the standard HS medium was further supplemented with 0.5% (v/v) ethanol. This addition aimed to suppress the formation of gluconic acid, a by-product of glucose metabolism33. The prepared medium was then adjusted to a pH of 6.0 and autoclaved at 121 °C for 15 min to ensure sterility. For the preparation of solid HS agar plates, 1.5% (w/v) agar was added34.

Sample preparation and bacterial isolation from fruit samples

Nine different fruit samples were used for bacterial isolation, including fresh fruits [grapes (FG), tomato (FT), and peach (FP)], semi-dried fruits [Date (SDD)], dried fruits [fig (DF), date (DD), and raisin (DR)], and fruit peels; [orange peel (OP) and apple peel (AP)]. Seeds were eliminated from semi-dried and dried dates before use. Fresh Fruits were washed with distilled water and peeled to obtain their rinds.

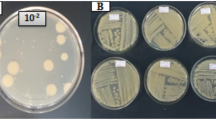

Individual fruit samples were homogenized aseptically using a sterilized homogenizer. Ten grams of each homogenate was subsequently transferred to separate sterile 250 mL conical flasks containing 90 mL of modified HS broth supplemented with 0.5% (v/v) ethanol. The flasks were subjected to vigorous agitation and incubated at 30 °C for 24 h, following the protocol described by33,35. Post-incubation, broth cultures from each fruit sample underwent serial dilution in separate sterile tubes containing 9 mL of sterile 0.85% saline solution36. Aliquots of 0.1 mL from each dilution were then spread onto individual HS agar plates using a sterilized glass spreader. The inoculated plates were incubated at 30 °C for approximately 24–48 h to allow for colony formation. Distinct colonies observed on the agar plates derived from each fruit sample were subsequently sub-cultured for purity verification. Finally, these isolates were cryopreserved in 20% (v/v) glycerol at − 20 °C for further experimentation37.

Screening of production of bacterial nanocellulose (BNC)

Isolated bacterial colonies were evaluated for their BNC production capability. Pure colonies were transferred aseptically into 50 mL conical flasks containing fresh HS medium. These cultures were then incubated at 30 °C for 5 days on a shaking incubator set at 130 rpm35. Subsequently, 10 mL of inoculum was transferred into each 250 mL flask containing 90 mL of freshly prepared HS broth supplemented with 0.5% (v/v) ethanol. These flasks were incubated statically at 30 °C for 10 days. The formation of a floating, gel-like pellicle on the culture medium’s surface served as a preliminary indicator of BNC production by the bacteria38. The isolate exhibiting the most robust BNC production capacity was chosen for further investigation.

Purification of BNC produced by different isolates

Following fermentation, the BNC pellicles formed on the culture medium surface were collected and washed three times with distilled water to remove residual media components. The pellicles were then transferred to flasks and boiled in distilled water at 70 °C for 3 h, following established protocols39. This initial step aimed to detach medium components. Subsequently, the BNC was treated with 0.1 M NaOH solution at 80 °C for three hours. This treatment served to further remove medium components and potentially lyse any bacterial cells trapped within the nanocellulose microfibers40. Notably, the NaOH treatment offers several advantages: elimination of specific metabolites, increased BNC viscosity, enhanced purification efficiency, removal of low-molecular-weight cellulose fractions, and ultimately, improved biomaterial properties. Once the BNC became transparent, the flasks were cooled to room temperature. The BNC pellicles were then subjected to extensive washing with double-distilled water until the filtrate reached a neutral pH. Finally, the purified BNC was transferred to a petri dish and oven-dried at 60 °C until it reached a constant weight. The dry weight was recorded as the BNC yield (g/L) for further analysis as described elsewhere8,41.

Bacterial identification and 16S rRNA gene sequencing

Whole amplification (1500 bp) and sequence of the 16S rRNA gene were achieved to identify the potent BNC producers. Six Pure cultures (1.1SDD, 1.3SDD, 3.2DD, 4.1OP, 9.1AP, and 9.2AP) were sent to Macrogen Company (Korea) in glycerol stock. PCR amplification was conducted using universal primers 27F (5′-AGAGTTTGATCCTGGCTCAG-3′) and 1492R (5′-CGGTTACCTTGTTACGACTT-3′). PCR products were purified and sequenced using primers 785F (5′-GGATTAGATACCCTGGTA-3′) and 907R (5′-CCGTCAATTCMTTTGAGTTT-3′)42. The obtained 16S rRNA sequences were deposited in the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) GenBank nucleotide database to take an accession number.

Phylogenetic analysis

For confirmation of bacterial isolate identity at the species level, the obtained 16S rRNA gene sequences were subjected to a comparative analysis using the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST). The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available in the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST)] repository, [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST]. This search identified closely related bacterial 16S rRNA gene sequences. Subsequently, the retrieved closest sequences were aligned using the CLUSTAL W software (version 1.8.3) to generate a multiple sequence alignment based on maximizing sequence identity. Finally, phylogenetic and molecular evolutionary analyses were performed utilizing Bayesian inference algorithms implemented through MrBayes software (version 3.2)43. This comprehensive approach ensured robust species identification and provided insights into the evolutionary relationships of the isolated bacteria. The appropriate models of molecular evolution to be used in Bayesian inference (BI) were selected using MrModeltest (ver. 2.3)44. The bayesian half-compatible phylogenetic tree was calculated in MrBayes. All clade support was measured using Posterior Probability (PP). Then, the phylogenetic tree was visualized using TreeGraph2 version 2.0.50-314.

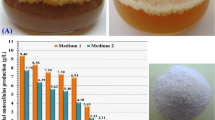

Production of BNC using fruit wastes as a carbon source

The influence of water extracts of three different fruit wastes [Date waste (DA), Orange peel (OR), and apple peel (AP)] as a sheep carbon source for bacterial nanocellulose production was evaluated separately on the most potent bacterial nanocellulose producer isolate (9.1AP). The collected fruit wastes were washed with distilled water, dried in an oven at 60 °C, ground, and stored at room temperature. A 10% fruit waste extract was prepared for each fruit waste powder by boiling it in distilled water and then cooling and filtering it45. The resulting filtrates were used to prepare (DA-HS), (OR-HS), and (AP-HS) in a 250 mL conical flask separately, using the HS broth media with the same formulations except adding glucose, which was replaced by extracts of Date waste (DA), Orange peel waste (OR), or Apple peel waste (AP) extracts respectively. For each flask, 10% (v/v) of the inoculum was used at OD 0.5 and was statically incubated at 30 °C for 7 days45,46. Figure 1 shows the schematic laboratory procedures for the isolation, purification, characterization, and production of bacterial nanocellulose (BNC) using fruit wastes as a carbon source.

Optimization of the bacterial cellulose production by Bacillus haynesii 9.1AP strain using Box–Behnken design

Various parameters were systematically evaluated to enhance growth conditions, aiming to maximize bacterial nanocellulose (BNC) yield from the most efficacious bacterial strain; Bacillus haynesii, which exhibited superior BNC production compared to all other isolated strains. These parameters include carbon source concentrations, growth temperature, and the medium’s pH value. As the broth media (DA-HS) containing the date waste extract gave the highest BNC yield (g/L), different extract concentrations (10%, 15%, and 20%) were tested.

Box-Behnken design (BBD) is a reliable and effective design used for optimization procedures since it reduces the total cost of the experiment by providing enough information to validate the model’s accuracy without needing many experimental runs. To determine the optimum levels for three independent variables as well as their mutual impacts on bacterial cellulose production by B. haynesii, a Box-Behnken design was used. These independent factors include temperature (X1), date waste extract (%) (X2), and initial pH level (X3). In the current study, 15 experimental runs were carried out to optimize the levels and explore the interaction effects among the selected independent variables on the synthesis of bacterial cellulose by B. haynesii. The independent variables were investigated at three levels (− 1, 0, 1). For the experimental design, the zero levels (center values) selected were temperature (29 °C), date waste extract (15%), and initial pH level (6). The center point was repeated three times (runs no. 6, 7, and 15) to determine the experimental error and the lack of fit of the model. Each experiment was duplicated to determine the dependent variable or response (bacterial cellulose production), and the average amount of bacterial cellulose production was determined (Y).

The following second-order polynomial equation was used to fit the experimental data of BBD and to predict the bacterial cellulose production by B. haynesii based on the initial pH level, date waste extract (%), and suitable temperature:

where Xi represents the coded levels of independent factors, and Y is the predicted BC production. The coefficients for regression, linear, quadratic, and interaction are shown by the symbols β0, βi, βii, βij, respectively.

Statistical analysis

The experimental design and the statistical analysis were done using Design Expert version 12 for Windows software. Three-dimensional graphs were generated using STATISTICA software version 8.

Nanocellulose characterization

Fourier transform infrared (FT-IR)

The functional groups of bacterial nanocellulose production by B. haynesii were determined by a Fourier transform infrared spectrometer, Thermo Fisher Nicolet IS10, (Waltham, MA, USA) Spectrometer.

Scanning electron microscope (SEM)

The external shape of nanocellulose production by B. haynesii was observed by scanning electron microscopy operational at 30 kV (SEM, JEOL JSM-6510/v, Tokyo, Japan).

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM)

The size and shape of nanocellulose production by B. haynesii were investigated by Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) (JEOL JSM-6510/v, Tokyo, Japan).

X-ray powder diffraction (XRD)

X-ray diffraction patterns of nanocellulose production by B. haynesii were analyzed by X-ray diffractometer (PAN Analytical X-Pert PRO, spectris plc, Almelo, The Netherlands). The metal content for nanocellulose production by B. haynesii was determined by energy-dispersive spectroscopy (EDS), (JEOL JSM-6510/v, Tokyo, Japan).

Zeta potential analysis

The charge of nanocellulose production by B. haynesii 9.1AP strain and stabilization in the middle of the liquid that it is dispersed in was determined by zeta potential (Malvern Zeta size Nano-Zs90, Malvern, PA, USA).

Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) and thermogravimetric analysis (TGA)

The thermal properties of nanocellulose produced by B. haynesii were studied by DSC and TGA. About 6 mg of B. haynesii was used to determine thermal analysis using TGA (TGA-50H Thermogravimetric analyzer). The sample was scanned at a flow rate of 40 mL/min over a temperature of 800 °C. The DSC technique is used to investigate the sample changes with temperature or time changes. The DSC thermogram behavior was investigated up to 400 °C.

Crystal violet elimination

The efficiency of nanocellulose produced by B. haynesii in eliminating dyes from aqueous solutions was determined by a batch adsorption experiment method. The concentration of CV dye (25 mg/L) solution (100 mL) was transferred in a 250 mL Erlenmeyer flask and then amended with a known concentration of nanocellulose produced by B. haynesii (1 to 5 g/L). The mixture was stirred at a constant speed of 500 rpm with contact times of 30, 60, and 90 min. At the end of time, the solution was separated from the adsorbent (nanocellulose) by centrifuging at 5000 rpm for 10 min, and the separated solution was measured using a UV–Vis spectrophotometer at 590 nm.

The efficiency of the CV dye elimination was measured using the following equation: Elimination % = \(\left( \frac{\text{Abs c }-\text{Abs s}}{\text{Abs c}}\right)*100\)

Abs c is the absorbance of the same concentrations of dye at 590 nm; Abs S is the absorbance of the sample treated by the same concentrations of dye at 590 nm.

Statistical analysis

The effectiveness of B. haynesii produced nanocellulose in removing dyes from aqueous solutions is presented as the mean standard error (SE) and was statistically analyzed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) SPSS 16. A Duncan multiple comparison test examined the post hoc variations between means. A difference was deemed significant when it was p < 0.05.

Results and discussion

Bacterial isolation and screening of bacterial nanocellulose production

Nine different fruit samples were used for bacterial isolation using HS agar. The bacteriological examination revealed that 19 isolates were retrieved from different samples. Eight isolates were shown to produce floating gel-like pellicle formation on the surface of the culture medium, indicating bacterial nanocellulose production. Table 1 shows BNC layer formation by different bacterial isolates for up to ten days.

Bacterial identification and phylogenetic analysis

Six potential BNC producers were characterized as gram + ve, rod-shaped, endospore-forming, and mucoid-creamy colonies on agar plates. 16S rRNA Sequence analysis showed that all identified strains belonged to the genus Bacillus; Three strains were identified as Bacillus velezensis (1.1SDD, 1.3SDD, and 9.2AP). The other three strains were identified as Bacillus amyloliquefaciens (4.1OP), Bacillus haynesii (9.1AP), which gave the highest BNC production among the obtained isolates, and Bacillus sp. (3.2DD). Obtained Sequences were submitted to NCBI and Gene Bank nucleotide sequence database and were deposited under accession numbers (PP064560 to PP064565).

The phylogenetic tree (Fig. 2) was constructed using the retrieved 16S rRNA gene sequences. This analysis effectively resolves the evolutionary relationships among the isolated Bacillus species with a high degree of confidence, providing definitive insights into their taxonomic placement.

Recent research has highlighted the potential of specific Bacillus strains for BNC production. These strains have garnered significant interest due to their efficiency in utilizing submerged fermentation processes and inexpensive, sustainable agricultural residues as carbon sources47. Notably, a marine Bacillus velezensis SMR strain was previously identified to synthesize highly structured BNC using the alga Ulva sp. biomass as the sole carbon source in a seawater-based medium8. Interestingly, while B. velezensis demonstrates BNC production capabilities, several isolates within this bacterial species harbor genes encoding putative lignocellulolytic enzymes. These enzymes enable the bacteria to effectively degrade cellulosic, hemicellulosic, and lignocellulosic materials48,49. This property suggests their potential for utilizing even more cost-effective feedstocks for BNC production in the future.

Further evidence suggests that B. velezensis strain 157 can break down a range of agro-industrial by-products used in the production of biofuels, such as soybean meal, sugarcane bagasse, wheat straw, wheat bran, maize straw, and rice husk50,51. Furthermore, Bacillus haynesii and Bacillus amyloliquefaciens are known to produce microbial exopolysaccharides for food application and suggested further exploration of its potential for various applications52,53. These studies highlight the potential of specific Bacillus strains for BNC production.

Optimization of BNC production by Bacillus haynesii 9.1AP strain through the application of the Box–Behnken approach

The optimal levels for three independent variables and their mutual impacts on BNC production by B. haynesii 9.1AP strain were determined with the use of a Box-Behnken design. These independent factors include temperature (X1), date waste extract (%) (X2), and initial pH level (X3). The plan included 15 separate experimental runs in the current study, and the independent variables were investigated at three distinct levels (1,0, − 1). The central point was replicated three times (runs 6, 7, and 15) to determine the experimental error and model lack of fit. The experiment was carried out twice, and the average production of bacterial cellulose was considered as the dependent variable or response (Y). Table 2 displays the predicted and actual results for BNC production, as well as the residual values. BNC production varies significantly depending on the conditions of the fermentation process. The highest BNC production was recorded in central run number 15, which reached 2.6 g/L at 29 °C, 15% date waste extract concentration, and an initial pH of 6. In run number 14, the lowest BNC production of 0.34 g/L was recorded at 21 °C temperature, using 10% date waste extract, and an initial pH level of 6.

Multiple regression analysis and analysis of variance (ANOVA)

The results of the ANOVA and multiple regression analysis of the Box-Behnken experimental data are shown in Tables 3 and 4. The coefficient of determination (R2) is a metric applied to evaluate the precision of a model. When regression models have an R2-value greater than 0.9, it indicates that there is a good correlation between the experimental and predicted results54. When the R2-value gets closer to 1, a design is thought to be more accurate in predicting the response55. Given that the current model has an R2-value of 0.9978 implies it is able to explain 99.78% of the variation in the BNC production. The estimated adjusted R2 value is 0.9939, suggesting a very high degree of similarity between the predicted and experimental BNC production values. The model’s high predicted R2 value of 0.9745 demonstrates that it is appropriate for predicting the BNC production by B. haynesii (Table 3). To conclude that the model has a high degree of significance and accuracy, the adjusted-R2 and predicted-R2 values must be within 20% of each other56,57. The data interpretation relied on the coefficients’ signs and effects of the variables58,59. Those coefficient values that are positive indicate that the variables have a synergistic interaction and support the enhancement of BNC production by B. haynesii. Table 3 reveals that the linear effect of date waste extract (%) (X2) and the interaction effect between both date waste extract (%) (X2) and initial pH level (X3) have positive coefficients, indicating an increase in bacterial cellulose production by B. haynesii. Conversely, negative coefficient values suggest that the variables negatively impact the BNC production by B. haynesii and reduce it.

Process factors were considered to have significant effects if they had confidence levels of 95 percent or higher and P-values lower than or equal to 0.0560. In the current study, the model terms are significant, with an F-value of 255.50 and a P-value of less than 0.0001. The lack of fit is not statistically significant with a P-value of 0.4249 (Table 3). Moreover, the coefficients P-values demonstrate that all quadratic effects of X1, X2, and X3, interactions between the tested factors (X1 X2 and X1 X3), and linear coefficients of X1, X2, and X3 are significant and have an impact on B. haynesii 's capability to produce bacterial cellulose (Table 3). Additionally, the coefficient of variation is 4.88%, PRESS (residual sum of squares) is 0.25, and the standard deviation is 0.07. The current model’s adequate precision value of 41.97 reflects the model’s accuracy. An adequate precision value is used to evaluate the signal-to-noise ratio; a value greater than four is recommended and indicates the model’s precision61.

To determine the correlation between multiple factors and the highest BNC production by B. haynesii, the estimated coefficients were fitted to a second-order polynomial equation. The following equation predicts BNC production by B. haynesii:

where Y represented the predicted amount of bacterial cellulose produced by B. haynesii, and the independent variables were temperature (X1), date waste extract (%) (X2), and initial pH level (X3).

The results of the fit summary in Table 4 were crucial for selecting an appropriate model for BNC production by B. haynesii. The quadratic model is an appropriate model for BNC production by B. haynesii, with a very low P-value > 0.0001. The lack of fit of the quadratic model is non-significant (F-value = 1.5, P-value = 0.4249), and the smallest standard deviation value of 0.0658. The quadratic model has the greatest adjusted R2 value (0.9939) and predicted R2 value (0.9745).

Model adequacy checking

The residuals are the difference between the predicted and actual response values. The normal probability plot (NPP) of residuals is a critical graphical tool that is applied to analyze the distribution of residuals and evaluate the accuracy of the theoretical model62. The NPP (Fig. 3A) indicates that the residuals have a normal distribution and closely adhere to the diagonal line, validating the model. When residuals deviate from a straight line, it indicates that they are not distributed regularly.

(A) NPP of residuals, (B) Graph comparing predicted to actual values, (C) Box-Cox plot for power transform, and (D) displays a graph comparing the studentized residuals with the predicted BNC production by B. haynesii 9.1AP strain as influenced by temperature (X1), date waste extract (%) (X2) and initial pH level (X3).

The model’s accuracy is confirmed by a strong correlation between the predicted levels of bacterial cellulose production and the actual experimental results, as displayed in Fig. 3B. The graph displays points near the fitted line, which confirms the adequacy and the model’s precision63,64. The Box-Cox model transformation graph, shown in Fig. 3C, depicts the blue line, which represents the optimal current transformation value (λ = 1), and the green line, which represents the best lambda value (λ = 0.81). The red lines represent the range of confidence interval values, with the minimum at 0.58 and the maximum at 1.04. The model is considered appropriate as the blue line represents the current transformation (λ = 1) and lies within the confidence intervals’ range (0.58 and 1.04), meaning no need for data transformation and confirming that it fits well to the experimental data. Figure 3D displays a graph comparing the studentized residuals with the predicted BNC production by B. haynesii. The residuals were distributed equally and randomly around the zero line, confirming constant variance, and demonstrating the model’s precision.

Three-dimensional surface (3D)

Figure 4A–C illustrates the 3D plots that were developed to find the optimal values of temperature (X1), date waste extract concentration (%) (X2), and initial pH level (X3) and the interactions that occur between them for maximum BNC production. To construct the 3D plots, the BNC production by B. haynesii was represented along the Z-axis to the X and Y axes for two independent factors, and the value of the third factor is fixed at the central level. The three variables that were chosen were combined pairwise as follows: X1 X2, X1 X3, and X2 X3.

Figure 4A displays the relationship between BNC production by B. haynesii and temperature (X1) and date waste extract concentration (%) (X2), with the initial pH level (X3) set at zero level. As the temperature and date waste extract concentration increased, it is evident that the BNC production by B. haynesii increased gradually. The highest temperature and moderate date waste extract levels resulted in the highest BNC production. Conversely, it was demonstrated that the highest and lowest concentrations of the date waste extract were associated with a decline in BNC production.

El-Naggar et al.39 reported that the maximum BNC production by Bacillus sp. strain SEE-3 was obtained at 37 °C. On the other hand, other studey found that the maximum bacterial cellulose production by Komagataeibacter bacteria occurred at temperatures between 28 and 30 °C in a cost-effective medium65.

Castro et al.66 and other studies have found that the type of carbon sources affects the production of bacterial cellulose. Researchers have attempted to improve the bioprocess of bacterial growth medium to minimize the overall cost of bacterial cellulose production by finding a cost-effective and sustainable carbon source to enhance the yield of bacterial cellulose67,68. Based on the dry weight, the highest BNC production by B. haynesii was achieved using the date waste extract. Dates contain a high concentration of carbohydrates in addition to a variety of other ingredients, including minerals, proteins, lipids, and vitamins. Various factors, including species, the stage of ripening, harvesting, and post-harvest conditions, among others, can influence the composition of date fruits. Date fruits contain a variety of carbohydrates, the most important of which are soluble sugars including fructose, glucose, and minor amounts of sucrose69. Date fruits also include dietary fiber such as fructans, hemicelluloses, cellulose, and pectin.

It is thought that the three sugars fructose, sucrose, and glucose are appropriate carbon sources for the bacterial production of cellulose. Fruit juices and extracts derived from fruit peels served as an alternate carbon source in the culture media for the acetic bacteria that produced the bacterial cellulose. The fruits have significant amounts of different sugars such as glucose, sucrose, xylose, lactose, and fructose, additionally, their pH is low65. Meanwhile, Güzel and Akpınar70 have shown that Komagataeibacter hansenii GA2016 utilized apple peel hydrolysates to produce the largest amount of bacterial cellulose. According to Kurosumi et al.71, Acetobacter xylinus NBRC 13693 produced the highest amount of bacterial cellulose in HS medium when fruit juices like orange and grape juice were used.

The BNC production is plotted against temperature (X1) and initial pH level (X3) in Fig. 4B, with date waste extract (%) (X2) held at zero level. It is evident that as the temperature and initial pH levels rose, the amount of cellulose produced by bacteria gradually increased. The highest temperature and a moderate pH level were shown to yield the maximum BNC production. Meanwhile, the higher and lower pH levels were shown to be correlated with a reduction in the BNC production.

Prior research by Tahara et al.72 showed that bacterial cellulose production was higher in a medium maintained at a pH of 5 than in a medium with a pH of 4. Velázquez-Riaño and Bojacá65 reported that the Komagataeibacter genus produced the greatest amount of bacterial cellulose when pH values were between 4.5 and 5.5. According to Al-Abdallah and Dahman73, the optimal pH for bacterial cellulose production by G. xylinus ATCC 700178 was pH 2. On the other hand, the optimal pH for bacterial cellulose production using Gluconacetobacter sp. gel_SEA623-2 was pH 3.574. In contrast, Kiziltas et al.69 reported that the optimal pH for the growth and bacterial cellulose production by A. xylinus 23769 was an alkaline pH 8.

Figure 4C shows the BNC production by B. haynesii as a function of the date waste extract (%) (X2), the initial pH level (X3), while temperature (X1) held at zero level. The highest amount of BNC production by B. haynesii was achieved when the levels of both date waste concentrations and the initial pH level were moderate. Meanwhile, it was demonstrated that the lowest and highest levels of both date waste concentrations and the initial pH level were associated with a decline in the formation of bacterial cellulose.

Desirability function (DF)

The DF function of the Design Expert Software (version 12) was applied to determine the optimal predicted values of the variables that would yield the highest achievable response. Prior to the validation of the optimization strategy, the value of the DF is frequently estimated theoretically75. The DF values varied between 1 (desirable) and 0 (undesirable). Figure 5 illustrates the optimization plot and the DF, providing predictions for the optimal values of the variables that result in the highest production of bacterial cellulose. The optimal values were found to be temperature (32.47 °C), date waste extract concentration (14.31%), and initial pH level (4.99) for the highest possible bacterial cellulose production (2.7 g/L).

An experiment was conducted in triplicate under the optimal predicted conditions to validate the production of BNC by B. haynesii. Subsequently, a comparison was made between the obtained experimental production of BNC (2.65 g/L) and the predicted production of BNC (2.7 g/L). The validation test confirmed a significant agreement between the predicted and experimental values of BNC production, indicating the effectiveness of the DF in predicting optimal values for maximum BNC production.

Nanocellulose characterizations

FT_IR spectroscopy analysis

The results in Fig. 6 demonstrate the FT_IR Spectroscopy analysis of bacterial nanocellulose produced by B. haynesii 9.1AP strain. The results show that there are 12 peaks were noticed in B. haynesii—nanocellulose 3415, 2933, 2351, 2153, 1657, 1547, 1399, 1231, 1059, 835, 613, and 544 cm−1. The peak at 3415 cm−1 is assigned to -OH groups present in the cellulose derived from Zea mays husk76. The peak at 2933 cm−1 denoted the stretching vibration of C–H, and was found in nanocrystalline cellulose-reinforced polyvinyl alcohol composite(PVA-NCC)77. The peak at 2351 cm−1 indicates the carboxylic components present in nanocellulose nanocomposite hydrogel78. The 2153 cm–1 peak was appointed to CO hydrogen-bonded79. The intense peak at 1657 cm−1 is appointed to (NO2) nitrate groups, which are accompanied by the CH2 groups of the glucopyranose rings in the nanocellulose80. The intense absorption peak at 1547 cm–1 is assigned to amide II due to CN stretching81. The peak at 1399 cm–1 was due to C–C stretching and ring vibrations in bacterial nanocellulose82. The intense peak at 1231 cm−1 was assigned to a sulfate group) of nanocellulose83. The peak at 1059 cm−1 is attributed to the C–C bands of the nanocellulose84. The peak at 835 cm−1 is assigned to CH285. The peak at 613 cm−1 is allocated to C=C–C bendings86.

FT-IR spectroscopy analysis found and approved all active groups, indicating that the obtained compound is nanocellulose.

SEM and TEM characterization

Morphological studies of the bacterial nanocellulose production by B. haynesii were achieved by SEM, which provides a report about the presence of homogeneity, voids, aggregates, and the distribution of bacterial nanocellulose. Figure 7a and b show the SEM images of nanocelulose- B. haynesii with a sponge, smooth, sheetlike structure, and disagglomeration position. The arrows pointed to the nanocelulose- B. haynesii. Some aggregations were shown in crystalline nanocellulose87. The nanocellulose fiber is rod-shaped; some of them are aggregated in the form of bundles88. The SEM results of bacterial nanocellolose (BNC) produced from Gluconacetobacter xylinus exhibited that BNC has a highly dense fibril structure with coinciding knots, which represents the high surface area, permeability, and crystallinity89. The results of TEM images in Fig. 7 display that nanocelulose- B. haynesii has one-dimensional nanoparticles (rode-like structure), and the average size of width ranged from 55.21 to 17.69 nm (Fig. 7c and d), and the length ranged from 75.66 to 113 nm (Fig. 7e and f). The TEM images of bacterial nanocellulose production by Bacillus sp. strain SEE-3 show needle-shaped particles with widths ranging from 30 to 40 nm and lengths ranging from 560 to 1400 nm. The average diameter of microfibrils of Medusomyces gisevii Sa-12, bacterial nanocellulose, was 97 nm90.

X-ray powder diffraction (XRD)

X-ray diffraction (XRD). The results in Fig. 8 display the X-ray diffraction analysis of nanocellulose produced by B. haynesii. The results demonstrate the seven sharp peaks exposed in the entire diffractogram placed at 2θ values of 25.75°, 31.83°, 32.99, 34.04, 39.73, 46.73, and 49.49°,which corresponding miller index (hkl) 100, 110,101,101,111, 111 and 200. The XRD results demonstrate that the nanocellulose produced by B. haynesii is crystalline. The peaks of nanocrystalline cellulose derived from Ulva lactuca marine alga located at 2θ values of 25.4, 31.6, and 34.691. The crystalline peaks were shown at 2θ 32.282° and 46.252°92.

Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) and differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) of bacterial nanocellulose

The thermogravimetric degradation curve of dried B. velezensis nanocellulose represents the percentage of mass loss in the initial sample as a function of temperature. The initial weight of the sample was 1 mg and slightly decreased as the temperature increased from ambient temperature (25 °C) to 93.37 °C. A second weight loss occurred when the temperature increased to 210.59 °C, with a weight loss percentage of 4.709%. This may be due to the loss of water content. A third weight loss (41.84%) occurred when the temperature increased to 389.61 °C, which could be attributed to cellulose depolymerization and dehydration90. When the temperature increased to 752.63 °C, the weight loss percentage reached 29.66%. At 792.33 °C, the remaining sample weighed 0.01806 mg, representing 2% of the initial weight. These results confirm the high thermal stability of B. velezensis nanocellulose (Fig. 9).

The glass transition (Tg) and melting temperature (Tm) of the bacterial nanocellulose produced by B. haynesii were assessed to determine its thermal behavior. The heat absorbed or emitted by the bacterial nanocellulose as a function of time or temperature is quantified by DSC. The DSC curve derived from the bacterial nanocellulose produced by B. haynesii is illustrated in Fig. 10. The bacterial nanocellulose DSC curve shows three peaks in the curve. The initial pair of peaks, ranging from 21.51 to 42.06 °C, represent the thermal effect of dehydration and water loss from the B. haynesii nanocellulose sample. Barud et al.93 reported that dehydration and water loss result in an endothermic peak between 40 and 100 °C.

The gradual and reversible transformation in an amorphous solid region from a relatively glassy and rigid state to a less viscous and rubbery state with temperature rise is known as the glass transition (Tg). It was determined that the Tg of the bacterial cellulose was approximately 44.28 °C94, or 13.94 °C95. The Tg value of the bacterial nanocellulose produced by B. haynesii, was greater than the value of 13.94 °C reported by George et al.95 but lower than the value of 44.28 °C reported by Mohite and Patel96. The advantage of a material is better when its Tg value is larger since it is expected that the material will undergo minimal aging when stored at temperatures that are lower than its Tg value97. The third peak, an exothermic peak at 153.82 °C, is caused by either the melting of the crystalline phase of cellulose or dehydration and water loss. Auta et al.98 observed that the bacterial cellulose sample changed substantially between 10 and 200 °C caused by evaporation of water content. Meanwhile, George et al.95 reported that at temperatures ranging from 80 to 140 °C, a known change occurs related to the melting of the crystalline phase of cellulose. The exothermic peak and the degradation reaction may be overlapped99.

Zeta potential characterization

The surface charge of B. haynesii- nanocellulose was determined by Zeta potential (Fig. 11). The results demonstrate that the B. haynesii- nanocellulose has a low negative charge (− 13.7). In general, zeta potential values lower than − 15 mV denote the start of particle agglomeration, and values higher than − 30 mV mean sufficient mutual repulsion, ensuing in colloidal stability94.

Energy-dispersive X-ray measurements

Energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) can investigate the abundance of different elements. The results in Fig. 12 and Table 5, demonstrate there are 6 elements present in B. haynesii- nanocellulose: C, O, Na, Si, P, and Cu with weight percentages 40.31, 44.51, 11.52, 0.19, 2.31, and 1.16, respectively. The most predominant elements are carbon, oxygen, and sodium (40.31, 44.51%, and 11.52%, respectively). Energy dispersive X-ray analysis (EDX) of bacterial nanocellulose produced from Gluconacetobacter xylinus BCZM exposed the elements carbon 70.10%, oxygen 23.10%, and sodium 6.8%100. According to EDX analysis of Gluconacetobacter xylinus cellulose membrane composed of Carbon 40.71%, Oxygen 13.98%, Hydrogen 38.6%, Nitrogen 5.41%, and Na 1.3%, these elements may be due to the medium contents and the purification procedure of bacterial nanocelullose101.

Crystal violet elimination

The results in Fig. 13 display the effect of different concentrations of adsorbent bacterial nanocellulose produced by B. haynesii (1 to 5 g/L), with contact times of 30, 60, and 90 min. The results demonstrate a significant difference between the dye elimination percentage with an adsorbent concentration of 1 and 2 g/L at different times. When the adsorbent concentrations increased to more than 2 g/L, no significant change was obtained when the adsorbent concentrations increased, and the contact time increased. The results show that the best concentrations of nanocellulose produced by B. haynesii to eliminate Crystal violet dye are 2 g/L at 60 min. The maximum dye elimination was 84.7%, with adsorbent concentrations of 2 mg/L and a contact time of 60 min. Crystal violet is a cationic dye (+) charge that can be bound to nanocellulose produced by B. haynesii (−) charge until the equilibrium occurs between charges, and then the dye removal reaches a constant value. Superabsorbent polymer nanocomposites (SAPCs) could be successfully used as promising dye adsorbent materials in wastewater102. The percentage of crystal violet removal is 70.8% by nanocellulose, which proved more efficient than native cellulose103. Crystalline nanocellulose (NC) incorporated with polyacrylonitrile (PAN) exhibits the highest CV removal capacity, achieving 91%104. The maximum removal of Crystal violet dye (95%) was obtained by Ag-cellulose nanocomposite derived from Peanut-Husk and Azadirachta indica as a reductant92. Nanocellulose has a large surface area to volume ratio, low cost, high natural abundance, intrinsic environmental inertness, and is a viable alternative adsorbent. Moreover, the easily functionalized surface of nanocellulose makes it easier to incorporate chemical moieties that could improve the pollutants’ ability to bind to the nanocellulose105.

Conclusions

This study underscores the potential of specific Bacillus strains for efficient bacterial nanocellulose (BNC) production, with Bacillus haynesii reported for the first time as a BNC-producing species. Optimization of BNC synthesis by the B. haynesii 9.1AP strain using a Box–Behnken design revealed that temperature, date waste extract concentration, and initial pH significantly influenced cellulose yield. The produced nanocellulose exhibited favorable physicochemical properties, including a glass transition temperature between 21.51 and 42.06 °C and a low negative surface charge, contributing to its colloidal stability. The high predictive accuracy of the regression model (R2 = 0.9745) further validates the experimental outcomes. Future investigations should explore other Bacillus species and alternative carbon sources to enhance the scalability and functional diversity of BNC for industrial applications.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available in the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST)] repository, [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST]. The obtained Sequences were submitted to NCBI and Gene Bank nucleotide sequence database and were deposited under accession numbers (PP064560 to PP064565)

References

Revin, V. V. et al. Production of bacterial exopolysaccharides: Xanthan and bacterial cellulose. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24, 14608 (2023).

Abol-Fotouh, D. et al. Bacterial nanocellulose from agro-industrial wastes: Low-cost and enhanced production by Komagataeibacter saccharivorans MD1. Sci. Rep. 10, 1–14 (2020).

Abdel-Hakim, A. & Mouradb, R. M. Nanocellulose and its polymer composites: preparation, characterization, and applications. Russ. Chem. Rev 92, 4 (2023).

Mohite, B. V. & Patil, S. V. A novel biomaterial: bacterial cellulose and its new era applications. Biotechnol. Appl. Biochem. 61, 101–110 (2014).

Chen, G. et al. Bioconversion of waste fiber sludge to bacterial nanocellulose and use for reinforcement of CTMP paper sheets. Polymers 9, 458 (2017).

Achamyeleh, A. A., Ankala, B. A., Workie, Y. A., Mekonnen, M. L. & Abda, E. M. Bacterial nanocellulose/copper as a robust laccase-mimicking bionanozyme for catalytic oxidation of phenolic pollutants. ACS Omega (2023).

Bagewadi, Z. K., Bhavikatti, J. S., Muddapur, U. M., Yaraguppi, D. A. & Mulla, S. I. Statistical optimization and characterization of bacterial cellulose produced by isolated thermophilic Bacillus licheniformis strain ZBT2. Carbohydr. Res. 491, 107979 (2020).

El-Naggar, N. E., El-Malkey, S. E., Abu-Saied, M. A., & Mohammed, A. A. Exploration of a novel and efficient source for production of bacterial nanocellulose, bioprocess optimization and characterization. Sci. Rep. 12(1), 18533 (2022).

Zhu, H., Zhang, Y., Wang, J., Li, Y. & Lin, W. In Advances in Applied Biotechnology: Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Applied Biotechnology (ICAB 2014)-Volume I. 109–119 (Springer).

Rastogi, A. & Banerjee, R. Production and characterization of cellulose from Leifsonia sp. Process Biochem. 85, 35–42 (2019).

Khan, H., Kadam, A. & Dutt, D. Studies on bacterial cellulose produced by a novel strain of Lactobacillus genus. Carbohydr. Polym. 229, 115513 (2020).

Tanskul, S., Amornthatree, K. & Jaturonlak, N. A new cellulose-producing bacterium, Rhodococcus sp. MI 2: Screening and optimization of culture conditions. Carbohydr. Polym. 92, 421–428 (2013).

Dellaglio, F. et al. Description of Gluconacetobacter swingsii sp. nov. and Gluconacetobacter rhaeticus sp. nov., isolated from Italian apple fruit. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 55, 2365–2370 (2005).

Padmanaban, S., Balaji, N., Muthukumaran, C. & Tamilarasan, K. Statistical optimization of process parameters for exopolysaccharide production by Aureobasidium pullulans using sweet potato based medium. 3 Biotech 5, 1067–1073 (2015).

Huang, C. et al. Using wastewater after lipid fermentation as substrate for bacterial cellulose production by Gluconacetobacter xylinus. Carbohydr. Polym. 136, 198–202 (2016).

Schramm, M. & Hestrin, S. Factors affecting production of cellulose at the air/liquid interface of a culture of Acetobacter xylinum. Microbiology 11, 123–129 (1954).

Jozala, A. F. et al. Bacterial nanocellulose production and application: A 10-year overview. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 100, 2063–2072 (2016).

Pathak, P. D., Joglekar, S. N., Mandavgane, S. A. & Kulkarni, B. D. Fruit peel waste “biorefinery” and sustainability issues. Bioresour. Util. Manag. 217–250 (2021).

Anbu, S., Padma, J., Punithavalli, K. & Saranraj, P. Fruits peel waste as a novel media for the growth of economically important fungi. J. Pharmacogn. Phytochem. 6, 426–428 (2017).

Revin, V., Liyaskina, E., Nazarkina, M., Bogatyreva, A. & Shchankin, M. Cost-effective production of bacterial cellulose using acidic food industry by-products. Braz. J. Microbiol. 49, 151–159 (2018).

Tissera, N. D., Wijesena, R. N., Yasasri, H., de Silva, K. N. & de Silva, R. M. Fibrous keratin protein bio micro structure for efficient removal of hazardous dye waste from water: surface charge mediated interfaces for multiple adsorption desorption cycles. Mater. Chem. Phys. 246, 122790 (2020).

Liu, J. et al. Removal of heavy metal ions and anionic dyes from aqueous solutions using amide-functionalized cellulose-based adsorbents. Carbohydr. Polym. 230, 115619 (2020).

Qiao, A. et al. Advances in nanocellulose-based materials as adsorbents of heavy metals and dyes. Carbohydr. Polym. 272, 118471 (2021).

Peiravi-Rivash, O., Mashreghi, M., Baigenzhenov, O. & Hosseini-Bandegharaei, A. Producing bacterial nano-cellulose and keratin from wastes to synthesize keratin/cellulose nanobiocomposite for removal of dyes and heavy metal ions from waters and wastewaters. Colloids Surf. A 656, 130355 (2023).

Hakimi, M. I. et al. Industrial Applications of Nanocellulose and Its Nanocomposites 409–437 (Elsevier, 2022).

Norrrahim, M. N. F. et al. Nanocellulose: A bioadsorbent for chemical contaminant remediation. RSC Adv. 11, 7347–7368 (2021).

Norfarhana, A., Ilyas, R. & Ngadi, N. A review of nanocellulose adsorptive membrane as multifunctional wastewater treatment. Carbohydr. Polym. 291, 119563 (2022).

Hu, X., Yan, L., Wang, Y. & Xu, M. Freeze-thaw as a route to build manageable polysaccharide cryogel for deep cleaning of crystal violet. Chem. Eng. J. 396, 125354 (2020).

Mahmood, O.A.A.-Q. & Waisi, B. I. Crystal violet dye removal from aqueous water using polyacrylonitrile precursor beads. Mater. Today Proc. 42, 2185–2192 (2021).

Abdelrahman, E. A. et al. Facile synthesis and characterization of novel nanostructures for the efficient disposal of crystal violet dye from aqueous media. Inorganics 11, 339 (2023).

Sağlam, S., Türk, F. N. & Arslanoğlu, H. Use and applications of metal-organic frameworks (MOF) in dye adsorption. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 110568 (2023).

Thakur, V., Sharma, P., Awasthi, A., Guleria, A. & Singh, K. Utility of acrylic acid grafted lignocellulosic waste sugarcane bagasse for the comparative study of cationic and anionic dyes adsorption applications. Environ. Nanotechnol. Monit. Manag. 20, 100824 (2023).

Mohammadkazemi, F., Doosthoseini, K. & Azin, M. Effect of ethanol and medium on bacterial cellulose (BC) production by Gluconacetobacter xylinus (PTCC 1734). Cellul. Chem. Technol 49, 455–462 (2015).

Guhados, G., Wan, W. & Hutter, J. L. Measurement of the elastic modulus of single bacterial cellulose fibers using atomic force microscopy. Langmuir 21, 6642–6646 (2005).

Abba, M., Abdullahi, M., Md Nor, M. H., Chong, C. S. & Ibrahim, Z. Isolation and characterisation of locally isolated Gluconacetobacter xylinus BCZM sp. with nanocellulose producing potentials. IET Nanobiotechnol. 12, 52–56 (2018).

Madigan, M., Martinko, J. & Parker, J. Brock Biology of Microorganisms 10th edn (Pearson, Prentice Hall, New York, 2003).

Yang, Y., Jia, J., Xing, J., Chen, J. & Lu, S. Isolation and characteristics analysis of a novel high bacterial cellulose producing strain Gluconacetobacter intermedius CIs26. Carbohydr. Polym. 92, 2012–2017 (2013).

Jozala, A. F. et al. Bacterial cellulose production by Gluconacetobacter xylinus by employing alternative culture media. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 99, 1181–1190 (2015).

El-Naggar, N.E., Mohammed, A. A. & El-Malkey, S. E. Bacterial nanocellulose production using Cantaloupe juice, statistical optimization and characterization. Sci. Rep. 13, 51 (2023).

Costa, A. F., Almeida, F. C., Vinhas, G. M. & Sarubbo, L. A. Production of bacterial cellulose by Gluconacetobacter hansenii using corn steep liquor as nutrient sources. Front. Microbiol. 8, 2027 (2017).

Beluhan, S., Herceg, F., Leboš Pavunc, A. & Djaković, S. Preparation and structural properties of bacterial nanocellulose obtained from beetroot peel medium. Energies 15, 9374 (2022).

Mao, D.-P., Zhou, Q., Chen, C.-Y. & Quan, Z.-X. Coverage evaluation of universal bacterial primers using the metagenomic datasets. BMC Microbiol. 12, 1–8 (2012).

Ronquist, F. et al. MrBayes 3.2: Efficient Bayesian phylogenetic inference and model choice across a large model space. Syst. Biol. 61, 539–542 (2012).

Nylander, J. MrModeltest ver. 2. Evolutionary Biology Centre, Uppsala University, Sweden (2004).

Sijabat, E. K., Nuruddin, A., Aditiawati, P. & Purwasasmita, B. S. Optimization on the synthesis of bacterial nano cellulose (BNC) from banana peel waste for water filter membrane applications. Mater. Res. Express 7, 055010 (2020).

Padmanabhan, S. K., Lionetto, F., Nisi, R., Stoppa, M. & Licciulli, A. Sustainable production of stiff and crystalline bacterial cellulose from orange peel extract. Sustainability 14, 2247 (2022).

Akhter, S. et al. Biosynthesis and characterization of bacterial nanocellulose and polyhydroxyalkanoate films using bacterial strains isolated from fermented coconut water. Process Biochem. 122, 214–223 (2022).

Chen, L. et al. Comparative genome analysis of Bacillus velezensis reveals a potential for degrading lignocellulosic biomass. 3 Biotech 8, 1–5 (2018).

Chen, L. et al. Complete genome sequence of Bacillus velezensis 157 isolated from Eucommia ulmoides with pathogenic bacteria inhibiting and lignocellulolytic enzymes production by SSF. 3 Biotech 8, 1–10 (2018).

Molina, G. et al. Microbial Bioprocessing of Agri-food Wastes: Industrial Enzymes (CRC Press, 2023).

Venkataraman, S., Rajendran, D. S. & Vaidyanathan, V. K. An insight into the utilization of microbial biosurfactants pertaining to their industrial applications in the food sector. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 33, 245–273 (2024).

Maurya, A. et al. Biofilm formation and extracellular polymeric substance (EPS) production by Bacillus haynesii and influence of hexavalent chromium. Bioresour. Technol. 352, 127109 (2022).

Nguyen, T.-T., Pham, T.-A., Nguyen, L.-H., Le, T. & Chu-Ky, S. Microbial Exopolysaccharides 194–214 (CRC Press, 2024).

El-Naggar, N.E., Soliman, H. M. & El-Shweihy, N. M. Extracellular cholesterol oxidase production by Streptomyces aegyptia, in vitro anticancer activities against rhabdomyosarcoma, breast cancer cell-lines and in vivo apoptosis. Sci. Rep. 8, 2706 (2018).

El-Naggar, N.E. Isolation, screening and identification of actinobacteria with uricase activity: Statistical optimization of fermentation conditions for improved production of uricase by Streptomyces rochei NEAE–25. Int. J. Pharmacol. 11, 644–658 (2015).

El-Naggar, N.E. & Rabei, N. H. Bioprocessing optimization for efficient simultaneous removal of methylene blue and nickel by Gracilaria seaweed biomass. Sci. Rep. 10, 17439 (2020).

Keirsgieter, H. Response Surface Modelling and Investigating into Release Kinetics and in Vivo-Toxicity of Nanocellulose-Based Slow-Release Devices for delivery of Quercetin. (2022).

El-Naggar, N.E. & El-Shweihy, N. M. Bioprocess development for L-asparaginase production by Streptomyces rochei, purification and in-vitro efficacy against various human carcinoma cell lines. Sci. Rep. 10, 7942 (2020).

Martínez, E. et al. 5-Fluorouracil drug delivery system based on bacterial nanocellulose for colorectal cancer treatment: Mathematical and in vitro evaluation. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 220, 802–815 (2022).

El-Naggar, N.E., Rabei, N. H. & El-Malkey, S. E. Eco-friendly approach for biosorption of Pb2+ and carcinogenic Congo red dye from binary solution onto sustainable Ulva lactuca biomass. Sci. Rep. 10, 16021 (2020).

El-Naggar, N.E., Hamouda, R. A., El-Khateeb, A. Y. & Rabei, N. H. Biosorption of cationic Hg2+ and Remazol brilliant blue anionic dye from binary solution using Gelidium corneum biomass. Sci. Rep. 11, 20908 (2021).

El-Naggar, N.E., Hussein, M. H. & El-Sawah, A. A. Phycobiliprotein-mediated synthesis of biogenic silver nanoparticles, characterization, in vitro and in vivo assessment of anticancer activities. Sci. Rep. 8, 8925 (2018).

El-Naggar, N.E., Hussein, M. H. & El-Sawah, A. A. Bio-fabrication of silver nanoparticles by phycocyanin, characterization, in vitro anticancer activity against breast cancer cell line and in vivo cytotxicity. Sci. Rep. 7, 10844 (2017).

Ojembarrena, F. D. B., García, S., Merayo, N., Blanco, A. & Negro, C. Ni (II) and Pb (II) removal using bacterial cellulose membranes. Polymers 15, 3684 (2023).

Velásquez-Riaño, M. & Bojacá, V. Production of bacterial cellulose from alternative low-cost substrates. Cellulose 24, 2677–2698 (2017).

Castro, C. et al. Gluconacetobacter medellinensis sp. nov., cellulose-and non-cellulose-producing acetic acid bacteria isolated from vinegar. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 63, 1119–1125 (2013).

Skiba, E. A., Shavyrkina, N. A., Skiba, M. A., Mironova, G. F. & Budaeva, V. V. Biosynthesis of bacterial nanocellulose from low-cost cellulosic feedstocks: Effect of microbial producer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24, 14401 (2023).

Amorim, L. F., Li, L., Gomes, A. P., Fangueiro, R. & Gouveia, I. C. Sustainable bacterial cellulose production by low cost feedstock: Evaluation of apple and tea by-products as alternative sources of nutrients. Cellulose 30, 5589–5606 (2023).

Kiziltas, E. E., Kiziltas, A., Bollin, S. C. & Gardner, D. J. Preparation and characterization of transparent PMMA–cellulose-based nanocomposites. Carbohydr. Polym. 127, 381–389 (2015).

Güzel, M. & Akpınar, Ö. Preparation and characterization of bacterial cellulose produced from fruit and vegetable peels by Komagataeibacter hansenii GA2016. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 162, 1597–1604 (2020).

Kurosumi, A., Sasaki, C., Yamashita, Y. & Nakamura, Y. Utilization of various fruit juices as carbon source for production of bacterial cellulose by Acetobacter xylinum NBRC 13693. Carbohydr. Polym. 76, 333–335 (2009).

Tahara, N. et al. Degree of polymerization of cellulose from Acetobacter xylinum BPR2001 decreased by cellulase produced by the strain. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 61, 1862–1865 (1997).

Al-Abdallah, W. & Dahman, Y. Production of green biocellulose nanofibers by Gluconacetobacter xylinus through utilizing the renewable resources of agriculture residues. Bioprocess Biosyst. Eng. 36, 1735–1743 (2013).

Kim, S. et al. Gluconacetobacter sp. gel_SEA623-2, bacterial cellulose producing bacterium isolated from citrus fruit juice. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 24, 314–319 (2017).

El-Naggar, N.E., Saber, W. I., Zweil, A. M. & Bashir, S. I. An innovative green synthesis approach of chitosan nanoparticles and their inhibitory activity against phytopathogenic Botrytis cinerea on strawberry leaves. Sci. Rep. 12, 3515 (2022).

Onkarappa, H. et al. Facile synthesis and characterization of nanocellulose from Zea mays husk. Polym. Compos. 41, 3153–3159 (2020).

Sri Aprilia, N. et al. Ultraviolet light exposure degradation effect on the properties of nanocrystalline cellulose-reinforced polyvinyl alcohol composite film. Prog. Rubber Plast. Recycling Technol. 38, 21–37 (2022).

Shafiee, M. R. M., Nejad, P. F. & Ghahfarokhi, Z. S. Synthesis, characterization and evaluation of antibacterial properties of Aloe vera/chondroitin sulfate/nanocellulose nanocomposite hydrogel. Nano Stud. 63–74 (2022).

Nasser, H., Rédey, Á., Yuzhakova, T., Tóth, Z. N. & Ollár, T. FTIR study of CO adsorption on molybdena-alumina catalysts for surface characterization. React. Kinet. Catal. Lett. 92, 329–335 (2007).

Kashcheyeva, E. I. et al. Simultaneous production of cellulose nitrates and bacterial cellulose from lignocellulose of energy crop. Polymers 16, 42 (2023).

Ooi, K. S. et al. Physicochemical characterization of bilayer hybrid nanocellulose-collagen as a potential wound dressing. Materials 13, 4352 (2020).

Naik, M. L. et al. Nanobacterial cellulose production and its antibacterial activity in biodegradable poly (vinyl alcohol) membranes for food packaging applications. ACS Omega 7, 43559–43573 (2022).

Al-Dulaimi, A. A. & Wanrosli, W. Isolation and characterization of nanocrystalline cellulose from totally chlorine free oil palm empty fruit bunch pulp. J. Polym. Environ. 25, 192–202 (2017).

Oh, S. Y. et al. Crystalline structure analysis of cellulose treated with sodium hydroxide and carbon dioxide by means of X-ray diffraction and FTIR spectroscopy. Carbohyd. Res. 340, 2376–2391 (2005).

Mok, C. F. et al. Preparation and characterization study on maleic acid cross-linked poly (vinyl alcohol)/chitin/nanocellulose composites. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 137, 49044 (2020).

Devi, T. R. & Gayathri, S. FTIR and FT-Raman spectral analysis of paclitaxel drugs. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Rev. Res. 2, 106–110 (2010).

Jahan, Z., Niazi, M. B. K. & Gregersen, Ø. W. Mechanical, thermal and swelling properties of cellulose nanocrystals/PVA nanocomposites membranes. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 57, 113–124 (2018).

Lani, N., Ngadi, N., Johari, A. & Jusoh, M. Isolation, characterization, and application of nanocellulose from oil palm empty fruit bunch fiber as nanocomposites. J. Nanomater. 2014, 13–13 (2014).

Nyakuma, B. B. et al. Comprehensive characterisation of the morphological, thermal and kinetic degradation properties of Gluconacetobacter xylinus synthesised bacterial nanocellulose. J. Nat. Fibers 19, 6255–6268 (2022).

Budaeva, V. V. et al. Bacterial nanocellulose nitrates. Nanomaterials 9, 1694 (2019).

Hamouda, R. A., Qarabai, F. A., Shahabuddin, F. S., Al-Shaikh, T. M. & Makharita, R. R. Antibacterial activity of ulva/nanocellulose and ulva/ag/cellulose nanocomposites and both blended with fluoride against bacteria causing dental decay. Polymers 15, 1047 (2023).

Aljeddani, G. S., Alghanmi, R. M. & Hamouda, R. A. Study on the isotherms, kinetics, and thermodynamics of adsorption of crystal violet dye using Ag-NPs-loaded cellulose derived from peanut-husk agro-waste. Polymers 15, 4394 (2023).

Barud, H. et al. Thermal characterization of bacterial cellulose–phosphate composite membranes. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 87, 815–818 (2007).

Morán, J. I., Alvarez, V. A., Cyras, V. P. & Vázquez, A. Extraction of cellulose and preparation of nanocellulose from sisal fibers. Cellulose 15, 149–159 (2008).

George, J., Ramana, K. V., Sabapathy, S. N., Jagannath, J. H. & Bawa, A. S. Characterization of chemically treated bacterial (Acetobacter xylinum) biopolymer: Some thermo-mechanical properties. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 37, 189–194 (2005).

Mohite, B. V. & Patil, S. V. Physical, structural, mechanical and thermal characterization of bacterial cellulose by G. hansenii NCIM 2529. Carbohydr. Polym. 106, 132–141 (2014).

Béchard, S. R., Levy, L. & Clas, S.-D. Thermal, mechanical and functional properties of cellulose acetate phthalate (CAP) coatings obtained from neutralized aqueous solutions. Int. J. Pharm. 114, 205–213 (1995).

Auta, R., Adamus, G., Kwiecien, M., Radecka, I. & Hooley, P. Production and characterization of bacterial cellulose before and after enzymatic hydrolysis. Afr. J. Biotech. 16, 470–482 (2017).

de Carvalho Benini, K. C. C., Voorwald, H. J. C., Cioffi, M. O. H., Rezende, M. C. & Arantes, V. Preparation of nanocellulose from Imperata brasiliensis grass using Taguchi method. Carbohydr. Polym. 192, 337–346 (2018).

Abba, M. et al. Physicochemical, morphological, and microstructural characterisation of bacterial nanocellulose from Gluconacetobacter xylinus BCZM. J. Nat. Fibers 19, 4368–4379 (2022).

Faroun Ahmed, E., Shawkat Ali, W. & Hasan Heider, N. Description and determination of the nanocellulose components produced from acetic acid bacteria. Revis Bionatura 8, 112 (2023).

Hosseinzadeh, S., Hosseinzadeh, H. & Pashaei, S. Fabrication of nanocellulose loaded poly (AA-co-HEMA) hydrogels for ceftriaxone controlled delivery and crystal violet adsorption. Polym. Compos. 40, E559–E569 (2019).

Zhou, Y. et al. Removal of crystal violet by a novel cellulose-based adsorbent: comparison with native cellulose. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 53, 5498–5506 (2014).

Maqbool, Q. et al. Waste‐valorized nanowebs for crystal violet removal from water. Small Sci. 2300286 (2024).

Gopakumar, D. A., Manna, S., Pasquini, D., Thomas, S. & Grohens, Y. New Polymer Nanocomposites for Environmental Remediation 469–486 (Elsevier, 2018).

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the Distinct Research Grant (DRG), University of Jeddah, Jeddah 21959, Saudi Arabia; for providing financial support for laboratory measurements and analysis of this paper under grant number (UJ-20-069-DR).

Funding

This research was funded by the Distinct Research Grant (DRG), University of Jeddah, Jeddah, and grant number (UJ-20-069-DR).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.R.M. performed all the laboratory experiments. R.R.M; N.E.E; and R.A.H contributed to conceptualization, methodology, data curation, original draft, visualization, validation, writing, reviewing, and editing, AM.B. resources, and visualization. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Makharita, R.R., El-Ahmady El-Naggar, N., Baghdadi, A.M. et al. Sustainable production of bacterial nanocellulose from date fruit waste using Bacillus haynesii for waste valorisation and crystal violet dye removal. Sci Rep 15, 25133 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-04711-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-04711-z