Abstract

Deep learning models require large amounts of annotated data, which are hard to obtain in the medical field, as the annotation process is laborious and depends on expert knowledge. This data scarcity hinders a model’s ability to generalise effectively on unseen data, and recently, foundation models pretrained on large datasets have been proposed as a promising solution. RadiologyNET is a custom medical dataset that comprises 1,902,414 medical images covering various body parts and modalities of image acquisition. We used the RadiologyNET dataset to pretrain several popular architectures (ResNet18, ResNet34, ResNet50, VGG16, EfficientNetB3, EfficientNetB4, InceptionV3, DenseNet121, MobileNetV3Small and MobileNetV3Large). We compared the performance of ImageNet and RadiologyNET foundation models against training from randomly initialiased weights on several publicly available medical datasets: (i) Segmentation—LUng Nodule Analysis Challenge, (ii) Regression—RSNA Pediatric Bone Age Challenge, (iii) Binary classification—GRAZPEDWRI-DX and COVID-19 datasets, and (iv) Multiclass classification—Brain Tumor MRI dataset. Our results indicate that RadiologyNET-pretrained models generally perform similarly to ImageNet models, with some advantages in resource-limited settings. However, ImageNet-pretrained models showed competitive performance when fine-tuned on sufficient data. The impact of modality diversity on model performance was tested, with the results varying across tasks, highlighting the importance of aligning pretraining data with downstream applications. Based on our findings, we provide guidelines for using foundation models in medical applications and publicly release our RadiologyNET-pretrained models to support further research and development in the field. The models are available at https://github.com/AIlab-RITEH/RadiologyNET-TL-models.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

There is a consensus among researchers that leveraging pretrained models is the path forward in machine learning (ML)1. In transfer learning (TL), a model is first pretrained on large datasets with sufficient amounts of data, and then retrained or fine-tuned on the actual specific dataset of the target task. This approach can improve model stability, and mitigate the impact of scarcity of annotated data, with the latter being common in medical ML due to the costly and tedious annotation process2.

ImageNet3,4—a dataset consisting of millions of natural images—is one of the most popular datasets for building pretrained models. Although there is research suggesting that it does improve results of downstream medical tasks5,6, there is also evidence to question its applicability in the medical domain7,8,9, and some researchers suggest that domain-specific medical datasets are more appropriate for TL2,10,11. Although this led to a rise of medical foundation models12,13, ImageNet remains a popular choice in medical ML5. Many papers have been published that exploit models previously pretrained on different datasets using various pretraining tasks14,15. However, based on the papers presented in7,8, we find that the motivation behind choosing a particular pretraining dataset is seldom acknowledged, nor is there a justification provided for using a specific method of pretraining. Although some authors do provide their motivation and guidelines for building pretrained models, repositories providing a comprehensive list of different model architectures pretrained in the medical domain are scarce15,16.

RadiologyNET17 is our own custom medical dataset which consists of radiology images acquired through different imaging modalities and depicting an assorted range of anatomical regions.

While RadiologyNET is a large dataset, it was originally unlabelled, and there were no available resources to manually annotate the data with pathological information. To address this limitation, we previously developed a method to identify patterns within the data and generate pseudo-labels17. Pseudo-labels generated through this process were used to pretrain a large number of popular neural network architectures for TL. This study is motivated by the fact that a vast amount of medical data is available, but annotating them is a complex and laborious process which is not feasible for many institutions. Therefore, we aimed to explore whether unannotated data could be leveraged to build pretrained models, achieving performance comparable to models pretrained on large, well-structured datasets like ImageNet4. Existing medical data pretraining efforts often rely on single-modality datasets with fewer than 100,000 images, which can limit the richness of learned feature representations and their generalisability. This raises two key questions: (i) How can we leverage large-scale, unlabelled medical image collections for model pretraining?, and (ii) How do such models compare in downstream performance to those pretrained on large, structured natural image datasets (e.g., ImageNet5)? The motivation for this study stems from the fact that model pretraining mostly relies on labelled and annotated data (which is often unavailable), prompting us to explore the possibility of leveraging unannotated data as a starting point for research. Importantly, this study is not clinically oriented but rather exploratory, with the goal to determine whether unlabelled medical data can be effectively used in this context.

Models used in TL studies are not always state-of-the-art18,19,20,21, but they are widely adopted in the research community due to their ease-of-use. While state-of-the-art performance often relies on highly specialised techniques tailored to specific tasks, TL experiments require models that are easy to configure and adapt to different training objectives22. Based on these considerations, we selected models that had previously achieved strong performance while remaining practical to reuse, and pretrained architectures commonly used in medical ML (ResNet18, ResNet34, ResNet5023, VGG1624, EfficientNetB3, EfficientNetB425, InceptionV326, DenseNet12127, U-Net20, MobileNetV3Small and MobileNetV3Large28). We used the RadiologyNET pretrained models for a comprehensive study of TL on five publicly available medical downstream tasks and challenges29,30,31,32,33,34. To ensure an objective evaluation, the challenges were chosen in a way that covers different problem types (image segmentation, regression, binary classification, and multiclass classification), and a range of different anatomical regions and medical imaging modalities.

In addition to using RadiologyNET, we reviewed other publicly available medical imaging datasets that are, or could be, used for TL in the medical domain. A summary is provided in Table 1, where RadImageNet13 stands out as the most suitable for TL based on its diversity, expert annotations, and large sample size. It consists of 1.35 million images annotated by 20 radiologists across 165 distinct pathologies (labels). Despite the emergence of medical TL models12,13, ImageNet is still a prevalent choice in medical ML, with recent research6 showing that simple fine-tuning of ImageNet models can achieve performance comparable with other medical foundation models. Therefore, in this paper, as a first step of evaluating RadiologyNET foundation models, we chose to compare RadiologyNET with ImageNet and training from randomly initialised weights, deferring comprehensive comparisons with other medical foundation models to future work. Nonetheless, we reflect on the differences between RadiologyNET and RadImageNet (i.e., automatically-generated versus expert-annotated labels) in the Discussion.

To summarise, our primary objective in this study is to compare our own RadiologyNET models (domain specific data) against ImageNet (generic image data), and juxtapose the obtained results against models trained from scratch (i.e. randomly initialised network weights42). Furthermore, we test these models in data-scare conditions, as prior research has shown that the utility of TL becomes less impactful when downstream tasks have sufficient training data6,43. Additionally, we offer our findings on TL in medical ML, which we acquired through this study, and provide our pretrained models to the wider community. The models are publicly available at https://github.com/AIlab-RITEH/RadiologyNET-TL-models.

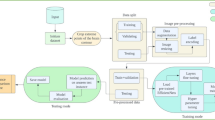

While this work does not introduce a novel technical innovation, its contributions are nonetheless significant in influencing dataset selection and model pretraining—both of which are crucial for advancing medical foundation models development such as CT-FM44 and MI245. Our key contributions are as follows: (i) Pretraining multiple widely used network architectures on the pseudo-labelled RadiologyNET dataset; (ii) Conducting a comprehensive evaluation of RadiologyNET-based foundation models, comparing them to models pretrained on ImageNet and those trained from randomly initialised weights across a range of downstream medical tasks (new insights on dataset and task importance); (iii) Investigating the impact of the pretraining task and domain on downstream performance, offering insights into TL in medical imaging; and (iv) Publicly releasing the RadiologyNET foundation models to the medical ML community, accompanied by guidelines for their application and broader recommendations for leveraging TL in medical ML tasks. The workflow diagram of the conducted research is given in Fig. 1.

Methods

RadiologyNET dataset and TL model pretraining

The RadiologyNET dataset17 is a custom dataset of medical radiology images obtained from Clinical Hospital Centre Rijeka between 2008 and 2017. Ethical approval for conducting research using this dataset was obtained from the competent Ethics Committee. The dataset has been labelled through a fully unsupervised approach described in detail in17, by extracting and combining features from three different data sources: text (diagnoses), images, and tabular data—i.e. attributes found in Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine (DICOM) file headers46. The unsupervised pipeline was used to label a set of 1,337,926 DICOM files into 50 distinct groups. Some of the groups exhibited high heterogeneity in regard to the modality and body-part examined, which was attributed to noise; as such, the final dataset used for pretraining contained 36 distinct groups, whose sizes can be seen in Figure 2. Specifically, after visually inspecting mosaic images composed of randomly selected samples from each cluster, we observed that some clusters lacked a clear relationship between the images, their associated DICOM tags, and diagnoses. However, these clusters were strongly associated with high heterogeneity measures related to imaging modality and the examined body region, which allowed us to exclude them based on this criterion. The available DICOM files were converted into \(224 \times 224\) pixel 8-bit portable network graphics (PNG) format. As some of the DICOM files contained three-dimensional volumes, these volumes were sliced into multiple two-dimensional images. Therefore, the total count of exported PNG images was 1,902,414. We refer the reader to17 for more details.

The RadiologyNET dataset used for pretraining covered multiple imaging modalities: Magnetic Resonance (MR), Computed Tomography (CT), Computed Radiography (CR), X-ray Angiography (XA) and Radio Fluoroscopy (RF) (five in total). The ratios of medical imaging modalities available in the RadiologyNET dataset can be seen in Fig. 3a. The dataset includes multiple anatomical regions and body parts, ranging from hands and ankles to the abdomen and the brain. Figure 3b shows the distribution of the BodyPartExamined attribute found in DICOM file headers, which is input manually by physicians and is therefore prone to errors, but can still provide insight into the distribution of anatomies. As it can be seen in Fig. 3, the RadiologyNET pretraining dataset consisted mostly of chest, abdominal and head images, captured mostly using MR and CT. To emphasize, each of the 36 classes was a cluster which was comprised of the instances that were similar based on the DICOM tags, images, and diagnoses, while body-part examined and modality served as an exclusion criterion for clusters that were too heterogeneous (reduced the initial 50 clusters to the used 36 clusters).

While the ImageNet pretrained models were taken from the PyTorch repositories, a range of different popular architectures were trained on the RadiologyNET dataset. These included: VGG1624, EfficientNets25 (EfficientNetB3 and EfficientNetB4), DenseNet12127, MobileNetV3Small and MobileNetV3Large28, InceptionV326 and ResNets23 (ranging from ResNet18 to ResNet50). RadiologyNET models were pretrained by solving a classification task (predicting one of 36 classes shown in Fig. 2), using cross-entropy loss and AdamW optimiser47. During the models’ pretraining and later on transfer learning, all layers were trainable from the start. The gradually unfreezing of the models’ layers during the pretraining process and later in transfer learning did not yield any improvements. The best reported learning rates (LRs) used in the original papers were used to pretrain the RadiologyNET models. In addition to multi-modality pretraining on the full RadiologyNET dataset, separate models were also pretrained using only MR, CR and CT data, to investigate the viability of multi-modality pretraining versus single-modality pretraining. To address the class imbalance in the training subset, oversampling techniques were used to ensure a more balanced representation of each class. The exemption from the classification pretraining task was U-Net20 pretraining for the semantic segmentation (for both ImageNet and RadiologyNET), where, initially, U-Net was pretrained as an image reconstruction task. As there is not an ImageNet-pretrained U-Net publicly available, the entire ImageNet dataset was downloaded and pretrained for this experiment. In addition to the vanilla U-Net, we also tested multiple approaches inspired by U-Net-ResNet5048,49,50, where the encoder branch was replaced by a classification-pretrained ResNet50, VGG16 or EfficientNetB451.

Regarding the technical setup, the pretraining process for all architectures was conducted entirely on a machine equipped with four NVIDIA RTX A6000 GPUs (48GB each) and 512GB of CPU RAM. The downstream tasks were evaluated on another machine with two NVIDIA L40S GPUs (48GB each) and 1TB of CPU RAM. Pretraining on the RadiologyNET dataset required, on average, approximately seven days per model, with multiple models often trained in parallel. For downstream tasks, each model architecture was typically trained and evaluated within two days.

Selected predictive modelling challenges

Several different publicly available datasets were chosen to test the effectiveness of RadiologyNET pretrained models. These datasets were chosen in a way that covers diverse radiological imaging modalities, various anatomical regions, and different task types (segmentation, regression, binary classification, and multiclass classification).

-

1.

LUng Nodule Analysis Challenge (LUNA)34. This challenge is based on the LIDC-IDRI dataset52 which contains a total of 1,018 CT lung scans. LUNA challenge consists of two parts: nodule classification (detect whether a number of locations in a scan are nodules or not); and nodule segmentation (from a full CT scan, output a mask indicating where the nodules are). The segmentation task was chosen for this study, where the winning solution employed the U-Net20 architecture. Inspired by U-Net-ResNet5048,49,50 (where the encoder branch is replaced by ResNet50), this research utilised several different classification-pretrained models in a U-Net-like topology to segment the nodules. These include the popular architectures VGG1624, EfficientNetB425,51 and ResNet5023.

-

2.

RSNA Pediatric Bone Age Challenge (PBA)29. This dataset consists of 14,236 hand radiographs labelled by expert radiologists, where the goal is to estimate skeletal age—a regression task. The winning architecture consists of InceptionV326 whose output was concatenated with the sex information from the public dataset. The concatenated result is fed into additional dense layers, whose final output represents bone age expressed in months. Given the success of convolutional neural networks (CNNs)29 in this challenge, we evaluated the performance of EfficientNetB3—another CNN architecture—using a similar approach of concatenating its output with the available sex information.

-

3.

GRAZPEDWRI-DX32 consists of 20,327 digital radiographs of wrists annotated by expert radiologists. The available annotations are suitable for different detection and classification tasks; but for the purposes of this research, the goal of classifying osteopenia was chosen, making this challenge a binary classification task. In total, 2,473 images have osteopenia present; thus, undersampling was performed to balance osteopenia versus non-osteopenia cases. The obtained dataset consisting of 4,946 images was randomly split into training (\(75\%\)), validation (\(12.5\%\)) and test (\(12.5\%\)) subsets. Recent research53 showed the performance of different ResNets and DenseNets when classifying osteopenia using the GRAZPEDWRI-DX dataset.

-

4.

The COVID-19 Radiography Database30,31 comprises chest CR images of patients diagnosed with COVID-19 (3,616 images) and instances of normal chest radiographs (10,192 images). Although the dataset also includes images of lung opacity (non-COVID-19 lung infection) and viral pneumonia cases, this study focuses on binary classification between COVID-19 and normal cases. Since there was a case imbalance between normal and COVID-19 cases—similarly to GRAZPEDWRI-DX–random undersampling was performed to lessen its potential impact. The original research31 tested several popular architectures, among which ResNet18 was one of the best performers, with MobileNetV2 achieving a marginally lower score (0.01% difference). Therefore, for this dataset, a newer version of MobileNet (MobileNetV3Large28) and ResNet1823 were tested.

-

5.

Brain Tumor MRI (BTMR)33. This dataset contains 7,023 MR images of the brain with labels for four different classes: glioma, meningioma, pituitary and no tumour—making this a multiclass classification problem. This Kaggle contest contains submissions from various different popular network topologies, ranging from different MobileNets28 to ResNets23. Thus, ResNet50 and MobileNetV3Small were tested here.

The selected challenges covered different problem types: LUNA—segmentation; PBA—regression; GRAZPEDWRI-DX and COVID-19—binary classification; BTMR—multiclass classification). Furthermore, as the RadiologyNET dataset is imbalanced with regard to imaging modalities and anatomical regions (Figure 3), the datasets were chosen to include (i) data which aligns with the pretraining dataset’s domain, and (ii) data which shows less overlap with the original pretraining dataset. GRAZPEDWRI-DX and RSNA PBA had the least overlap in terms of domain relevance, whereas Brain Tumor MRI aligned with the RadiologyNET’s domain the most. It is important to note that overlap in this context refers only to domain relevance, and that the RadiologyNET dataset and downstream tasks were completely independent, i.e. the patient scans found in downstream tasks were not a part of the RadiologyNET dataset.

Additionally, to assess the impact of modality-specific pretraining, we compared MR-only, CR-only and CT-only pretrained versions of architectures tested on BTMR, GRAZPEDWRI-DX, RSNA PBA, COVID-19 and LUNA datasets against their multi-modality pretrained counterparts. For CT, a ResNet50 model was pretrained exclusively on CT images and incorporated as the encoder in a U-Net-ResNet50 architecture for the LUNA segmentation task. For MR, both MobileNetV3Small and ResNet50 models were pretrained on MR-only data and subsequently evaluated on the BTMR classification task. For the GRAZPEDWRI-DX, RSNA PBA, and COVID-19 datasets, CR-only pretraining was performed on DenseNet121, ResNet34, EfficientNetB3, InceptionV3, MobileNetV3Large, and ResNet18 models, followed by evaluation on the corresponding tasks. The performance of these modality-specific models was then compared to that of models pretrained on the full, multi-modality RadiologyNET dataset to examine the impact of pretraining diversity.

Evaluation on downstream tasks

For each of the challenges, we tested three approaches: (i) training from randomly initialised weights, (ii) fine-tuning on ImageNet, and (iii) fine-tuning on RadiologyNET. For simplicity, any model trained from scratch (i.e. randomly initialised weights) will be referred to as Baseline. We followed the original proposed solutions for the individual tasks as closely as possible. This applies to model architecture, optimiser and loss functions, and any changes to the model (e.g. the additional sex information used in the PBA Challenge solution). We note that the aim of this study was not to outperform state-of-the-art, but to compare the performance of different TL models and strategies, while making use of network architectures that performed well on the tasks in previous studies.

All models were trained under equal conditions: with a maximum of 200 epochs, and an early stopping mechanism halting the training process if the validation results did not improve in the span of 10 consecutive epochs. All model parameters were allowed to be fine-tuned during the training process. Each model was trained five times using learning rates logarithmically sampled in the range \([10^{-2}, 10^{-5}]\), with a base-10 step size. Although higher (\(\ge 0.1\)) and lower (\(\le 10^{-6}\)) learning rates were initially tested as well, they were later excluded from the study due to their inferior performance across all models and challenges. With lower learning rates, the models would fail to converge within the maximum number of epochs, whilst higher learning rates brought overall lower scores.

For the LUNA segmentation task, U-Net-based models were pretrained using two approaches. The first approach involved simple reconstruction, where the output image matched the input image, inspired by autoencoders54. In the second approach, the encoder was replaced with a pretrained backbone model (ResNet50, EfficientNetB4, or VGG16) while retaining the original U-Net decoder. Skip connections were preserved by linking intermediate encoder outputs to the corresponding decoder layers, thus preserving U-Net’s signature multi-resolution feature fusion. Both approaches were then trained on the given LUNA segmentation task with the same hyperparameters as mentioned above.

To compare the statistical significance of the obtained results, a Levene test55 was first performed to determine whether significant differences in variance exist. Since the differences were deemed significant (\(p<0.05)\), non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis tests56 were computed, followed by a pairwise Mann–Whitney-U (MWU) tests with Bonferroni correction where the Kruskal-Wallis showed potential significant differences.

For the segmentation task, reported metrics include Intersection-over-Union (IoU) and the Dice score57. Performance on the regression task is reported using Mean Absolute Error (MAE) and Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE), while performance on classification tasks is reported using Precision, Recall, Accuracy, and F1-score. Out of these metrics, the Dice score was used for statistical tests in the segmentation task, MAE for the regression task, and F1-score was used in classification tasks.

The initial findings for GRAZPEDWRI-DX and COVID-19 challenges showed that there are no noticeable differences between ImageNet and RadiologyNET models’ performance. Thus, for RSNA Pediatric Bone Age and Brain Tumor MRI datasets, the codecarbon58 package was used to measure whether there are differences in emissions and energy consumed. As expected, the recorded emissions strongly correlated with the number of epochs required to converge. Consequently, the number of epochs was used as an evaluation metric and is reported in the results, as it is a simpler metric that was already available for the previously tested datasets.

Despite the initial findings showing minimal differences in performance between the three approaches when models reached convergence, there was an observable difference in initial model performance (i.e. in the first few training epochs). For this reason, we hypothesised that the three approaches might behave differently when training time, and resources in general, are heavily reduced. To investigate this influence and possible boosts to initial model training, a small-scale experiment was conducted on the GRAZPEDWRI-DX and Brain Tumor MRI datasets. In this experiment, the training time was reduced to 10 epochs, and the training subsets for these datasets were randomly reduced to 5%, 25%, and 50% of their original size. The validation and test subsets remained unchanged. GRAZPEDWRI-DX was chosen due to its minimal overlap with the RadiologyNET pretraining domain, and Brain Tumor MRI for its closer alignment with the pretraining data. Additionally, Grad-CAM59 heatmaps were visualised to compare the areas of focus for each of the three approaches on the two datasets. The Grad-CAM heatmaps were independently reviewed by two expert radiologists, each based in a different clinical centre, to assess the quality of the models’ focus on relevant areas within the images. Each radiologist evaluated a sample of 20 randomly sampled heatmaps from the GRAZPEDWRI-DX test set (obtained with DenseNet121), and another 20 randomly sampled heatmaps from the BTMR test set (generated with ResNet50). The radiologists rated each heatmap on a scale from 1 to 5, with 1 indicating that the model concentrated on entirely irrelevant areas, and 5 indicating that it focused solely on the relevant regions. In addition to rating the heatmaps, the radiologists were asked to report any observations they might have for each of the presented heatmaps. The source of each heatmap was concealed from the radiologists (i.e. they were labelled as algorithms (a)—RadiologyNET, (b)—ImageNet and (c)—Baseline), to ensure evaluation is based solely on the visual information provided.

Results

The results reported here were obtained on the test subset, and are derived from the models that exhibited the best performance on the validation subset of each respective dataset. The results obtained on the validation set are given in Supplementary Tables S1, S2, S3 and S4. The only exception is LUNA, where the reported results (shown in Table 2) were computed on the validation subset (as reported in60).

The best results for PBA, GRAZPEDWRI-DX, COVID-19 and BTMR are shown in Tables 3, 4, 5 and 6, respectively. Each table contains results averaged across five runs, in addition to overall best recorded performers on the test subset.

The exact p-values for metrics comparison are given in Supplementary Table S5, while the comparison of recorded epochs (i.e. training length) are given in Supplementary Table S6. Additionally, examples of model predictions for BTMR, COVID-19, GRAZPEDWRI-DX, and PBA datasets can be seen in Supplementary Figure S1. The figure shows instances where all models correctly predicted the target class (thus reaching consensus), as well as more challenging cases where predictions were inconsistent or incorrect.

LUng nodule analysis results

Among the results for basic U-Net (shown in Table 2), Baseline outperformed both TL strategies, having attained the highest Dice and IoU scores. ImageNet and RadiologyNET reconstruction-pretrained U-Net models achieved significantly worse results (MWU, \(p=0.024\) and \(p=0.024\) for ImageNet and RadiologyNET against Baseline, respectively). In contrast, U-Net-ResNet50, U-Net-EfficientNetB4, and U-Net-VGG16 faired better than the basic U-Net, achieving higher Dice and IoU scores. While observing U-Net-ResNet50, U-Net-EfficientNetB4 and U-Net-VGG16, the three TL approaches obtained comparable performance with the only statistically significant difference recorded between U-Net-ResNet50 RadiologyNET and Baseline models (MWU, \(p=0.024\)). Figure 4 shows the difference in model outputs between models pretrained as reconstruction tasks, versus models pretrained as classification tasks. The reconstruction-pretrained model merely replicated the input image, despite our efforts to impart valuable features to the model.

Pediatric bone age challenge results

As reported in Table 3, RadiologyNET achieved the best performance on the EfficientNetB3 architecture, outperforming ImageNet models in terms of MAE, while ImageNet models demonstrated significantly faster convergence (ImageNet vs. RadiologyNET, MWU, \(p=0.033\)). When it comes to InceptionV3 and the obtained MAE, ImageNet models outperformed RadiologyNET and Baseline. Similarly to its performance on EfficientNetB3, ImageNet pretrained models required fewer epochs to converge (although the difference was not statistically significant). InceptionV3 models pretrained on RadiologyNET achieved similar results to those Baseline models, exhibiting similar convergence time (RadiologyNET vs. Baseline, MWU, \(p=1.00\)).

GRAZPEDWRI-DX results

The results for GRAZPEDWRI-DX are shown in Table 4. When it comes to DenseNet121, ImageNet’s models achieved higher F1-scores on average, but the differences in the obtained scores between the three approaches were not statistically significant (Kruskal-Wallis, \(p=0.063\)). On the other hand, RadiologyNET models demonstrated fastest convergence, which was not significantly different than ImageNet (ImageNet vs. RadiologyNET, MWU, \(p=0.07\)), but was significantly faster than Baseline models (RadiologyNET vs. Baseline, MWU, \(p=0.033\)).

The performance of Baseline ResNet34 models diverged between runs. When comparing Baseline to ImageNet, the differences in F1-score are significantly different (ImageNet vs. Baseline, MWU, \(p=0.024\)), but the differences in F1-score where not as prominent when comparing Baseline to RadiologyNET (RadiologyNET vs. Baseline, MWU, \(p=0.095\)). When comparing epoch count, there were no statistically significant differences between the approaches (Kruskal-Wallis, \(p=0.199\)).

COVID-19 results

While CR images constitute a minority within the RadiologyNET dataset, chest radiographs were the most prevalent subtype17. Consequently, ImageNet and RadiologyNET exhibited comparable performance on MobileNetV3Large (ImageNet vs. RadiologyNET, MWU, \(p=1.00\)). Models trained from scratch consistently underperformed both ImageNet and RadiologyNET, with statistically lower F1-scores achieved on the test subset (MWU, \(p=0.047\) and \(p=0.024\) for ImageNet and RadiologyNET, respectively). In terms of epochs required to converge, the differences were not statistically significant between the approaches with MobileNetV3Large (Kruskal-Wallis, \(p=0.326\)).

When it comes to the evaluation of ResNet18 models, both ImageNet and RadiologyNET pretrained models exhibited nearly identical F1-score performance, with no statistically significant differences observed between the two (ImageNet vs. RadiologyNET, MWU, \(p=1.00\)). Also, both of the TL approaches performed significantly better than the Baseline models (MWU, \(p=0.035\) for both ImageNet and RadiologyNET). Curiously, all ImageNet models converged at precisely the 16th epoch, which was statistically different than RadiologyNET and Baseline (MWU, \(p=0.020\) and \(p=0.022\) when compared to RadiologyNET and Baseline, respectively). The difference between RadiologyNET vs. Baseline convergence time was not statistically significant (RadiologyNET vs. Baseline, MWU, \(p=0.103\)).

Brain tumor MRI results

The Brain Tumor MRI dataset shares the biggest overlap with the original pretraining dataset, as it contains MR images of the brain, which are prevalent in the RadiologyNET dataset. The results for the Brain Tumor MRI dataset are shown in Table 6. While ImageNet and RadiologyNET achieved almost identical F1-scores with MobileNetV3Small (ImageNet vs. RadiologyNET, MWU, \(p=1.00\)), Baseline models exhibited statistically worse results in terms of classification metrics (MWU, \(p=0.048\)). Similarly to MobileNetV3Small, ImageNet and RadiologyNET achieved comparable performance in terms of metrics (MWU, \(p=1.00\)), with Baseline being statistically worse than the two (MWU, \(p=0.024\) and \(p=0.036\) for ImageNet and RadiologyNET, respectively). However, in this case, RadiologyNET demonstrated an advantage in terms of convergence time, by requiring a significantly lower number of epochs to converge than Baseline (RadiologyNET vs. Baseline, MWU, \(p=0.028\)), but this difference was not significant when compared to ImageNet (ImageNet vs. RadiologyNET, MWU, \(p=0.052\)).

Multi-modality versus single-modality pretraining

Comparison of TL performance between MR-only, CR-only, CT-only and multi-modality pretrained RadiologyNET models. Results are averaged over five independent runs, with mean values and standard deviations indicated on (or above—as is the case in subfigure a) each bar. The p-values are indicated at the top and, where statistically significant differences exist, they are underscored in blue.

Figure 5 shows the performance of single-modality (MR-only, CR-only, and CT-only) versus multi-modality pretrained RadiologyNET models. The results are shown across five independent runs, with statistical differences calculated using Student’s t-test. The result are shown for all tested datasets: PBA (subfigure a and b), LUNA (subfigure c), GRAZPEDWRI-DX (subfigures d and e), COVID-19 (subfigures f and g), and BTMR (subfigures h and i).

Among the tested datasets (and architectures), U-Net-ResNet50 (LUNA dataset) was the only case where no statistically significant differences were observed between single-modality and multi-modality pretrained models. On the other hand, the PBA dataset exhibited mixed results depending on the architecture: for EfficientNetB3, multi-modality pretraining demonstrated significantly better performance than CR-only at all learning rates; while the opposite is true in the case of InceptionV3. In the GRAZPEDWRI-DX dataset, DenseNet121 models pretrained with multi-modality data generally achieved a significantly higher F1-score compared to CR-only models, with similar performance at the highest tested learning rate, \(10^{-3}\). In contrast, ResNet34 models showed comparable performance between multi-modality and CR-only pretraining, with CR-only demonstrating a slight advantage at the lowest tested learning rate, \(10^{-5}\). In the COVID-19 dataset, both multi-modality pretrained architectures (MobileNetV3Large and ResNet18) either outperformed CR-only models, or showed comparable performance with no statistically difference. In the BTMR dataset, MobileNetV3Small models pretrained with multi-modality achieved significantly better performance compared to MR-only models across all tested learning rate settings. For ResNet50, multi-modality pretraining showed superior performance overall, although the differences were less pronounced at the highest tested learning rate, \(10^{-3}\).

A total of 27 statistical comparisons were conducted. Among these, no statistically significant differences were observed in 10 cases. In 4 cases, single-modality pretraining outperformed multi-modality, while in 13 cases, multi-modality pretraining demonstrated better performance compared to single-modality. In MR-only comparisons, multi-modality pretraining outperformed MR-only in 5 out of 6 cases. In CR-only comparisons, single-modality pretraining showed improved performance in 4 out of 18 cases, while multi-modality pretraining was better in 9 cases. In CT-only comparisons on the LUNA dataset, no statistically significant differences were found between CT-only and multi-modality pretraining.

Training progress and resource-limited conditions

As the performances between ImageNet and RadiologyNET seldom statistically differed, additional analyses of the trained models was performed, by analysing the impact of pretrained weights on training progress. The results are shown in Figures 6 and 7.

Both ImageNet and RadiologyNET pretrained models gave overall boosts to performance in the first 10 epochs, which is especially noticeable when compared to Baseline. ImageNet’s most significant boost is visible on the InceptionV3 architecture employed on the RSNA PBA Challenge, where its MAE is lower than the other two approaches. On the other hand, RadiologyNET pretrained weights demonstrated a boost in performance on DenseNet121, ResNet50, and MobileNetV3Small architectures. This suggests that RadiologyNET pretrained weights could be beneficial when training time is limited. However, the extent of this improvement may vary depending on the architecture and task, and it does not consistently translate into statistically significant improvements in final performance. To test the significance of possible performance improvements in resource-limited conditions, a small scale experiment was performed on the GRAZPEDWRI-DX and Brain Tumor MRI datasets, where the original training subsets were randomly downsized to 5%, 25%, and 50% of their original size, and the training duration was capped at 10 epochs. The downsizing process was carried out in a manner that preserved the original class distribution, in order to avoid introducing any additional bias. The models were trained using the learning rates specified in Tables 4 and 6. Each approach underwent five training runs, with the mean F1-scores, along with the standard deviation, shown in Figure 8.

Results of the MobileNetV3Small (BTMR) and DenseNet121 (GRAZPEDWRI-DX) models during 10 epochs of training, when training data is reduced to \(5\%\), \(25\%\) and \(50\%\) of the original training subset. The other subsets remained unchanged. F1-score five-run mean and standard deviation is shown per each epoch.

Grad-CAM evaluation

The radiologists’ evaluation scores are shown in Fig. 9, while samples of generated heatmaps (which were also shown to radiologists) are given in Supplementary Figures S2, S3, S4, S5, S6, and S7. Both radiologists noted that Baseline’s BTMR heatmaps were unreliable, while RadiologyNET’s heatmaps showed the best focus on pathologies present in the images. One radiologist noted that ImageNet’s BTMR heatmaps “seemed to be a little bit offset in some cases,” while the other said that ”it is significantly less accurate in detecting tumour area than [RadiologyNET]”. When it comes to GRAZPEDWRI-DX heatmaps, one radiologist reported that the presence of a cast puzzled all three models, but noted that the Baseline model ”focused a lot on the fracture [near osteopenia], but also the carpal bones, which would be the most relevant to look at.” The other radiologist reported that RadiologyNET’s GRAZPEDWRI-DX heatmaps were probably the most reliable of the three, but with too wide (non-specific) areas of focus; and that ImageNet’s heatmaps were polarising: sometimes being surprisingly specific and accurate, and sometimes missing the relevant area entirely. In their rankings and across both datasets, the radiologists agreed that the three algorithms struggled with images in which diseased/abnormal tissue was not present. However, they noted that heatmaps generated by RadiologyNET models were the most dependable overall, exhibiting the best focus on pathological regions when present.

Discussion

In most cases, RadiologyNET and ImageNet’s peformance was almost identical, especially when the training process was not data or time-constrained. Statistical differences were primarily observed between these two approaches and the Baseline models, whose performance was worse than ImageNet and RadiologyNET foundation models.

When observing each challenge separately, the LUNA dataset showed interesting results. Specifically, reconstruction-pretrained models significantly underperformed compared to those pretrained as classification tasks.

Reconstruction pretraining focused on replicating textures and patterns and did not capture the semantic meaning behind each pixel, leading to results which merely replicate the input image. In contrast, classification-pretrained encoders (like ResNet50, VGG16, and EfficientNetB4) learn features that are better suited for segmentation tasks where pixel-wise semantic meaning is important, as is the case in LUNA nodule segmentation. While reconstruction-pretrained models demonstrated a significant performance gap, there may be another task type where such models would show improved performance. One example could be image compression or denoising, but testing this hypothesis fell out of scope of this study. Despite the suboptimal performance of U-Net pretrained as a reconstruction task, we believe it is important to report failed experiments, as these findings contribute to the broader scientific understanding and may prevent other researchers from investing time and resources into approaches that are less likely to succeed. The other challenges also demonstrated interesting results, where the PBA and GRAZPEDWRI-DX showed how the pretraining domain might influence the results. Namely, the RadiologyNET pretraining dataset consisted mostly of CT/MR images of the head and abdomen, with limited available wrist/hand radiographs. Although ImageNet does not contain medical images, its diverse range of natural images may have enabled ImageNet models to learn more generalisable features compared to RadiologyNET, which is more domain specific. This was further corroborated by the COVID-19 and BTMR results, where RadiologyNET models demonstrated comparable performance to ImageNet, and in some instances, exhibited faster training progress compared to both ImageNet and Baseline (Fig. 7). The observed improvement in training progress may still be beneficial, particularly in resource-constrained settings, but it is also important to acknowledge that RadiologyNET did not consistently outperform ImageNet, which is a limitation of RadiologyNET models in their current form.

In addition, we investigated the impact of single-modality versus multi-modality pretraining by comparing RadiologyNET models pretrained exclusively on MR, CR, or CT images against those pretrained on the full, multi-modality dataset. For the BTMR classification task, models pretrained on MR-only data showed a statistically significant drop in performance compared to multi-modality counterparts. On the other hand, CR-only models show mixed results. In the COVID-19 dataset multi-modality pretrained models (MobileNetV3Large and ResNet18) generally outperformed or matched the performance of CR-only models. In the RSNA PBA dataset, the results were architecture-dependent: EfficientNetB3 benefited from multi-modality pretraining across all learning rates, while InceptionV3 favoured CR-only pretraining. In GRAZPEDWRI-DX, DenseNet121 generally performed better with multi-modality, while ResNet34 showed mixed results. However, for the LUNA segmentation task, where CT is the predominant modality (53.73% of the whole RadiologyNET dataset), no significant difference was observed between CT-only and multi-modality pretrained models. The results indicate that the choice of NN topologies (and their internal mechanisms) could be a factor, but there is also a general trend visible: modality diversity is valuable when the single modality lacks sufficient internal variability or representation. For example, MR images have less variability than CR images, thus being biased towards certain anatomical regions. As a result, MR-only models benefit more from the inclusion of other modalities and, in contrast, CR-only models are less reliant on multi-modality pretraining. In the case of CT-only versus multi-modality comparisons, since the multi-modality dataset is dominated by CT images, adding data from other modalities did not significantly alter the learned representations. Nonetheless, it is worth to noting that different feature extraction schemes such as unsupervised representation learning60 might lead to different clusters and different numbers of clusters, which could significantly impact the obtained results. However, with the presented setup and study settings, the obtained results yield the observations presented above.

The greatest performance differences were observed under resource-limited conditions. As there were cases where Baseline models achieved comparable results when resources were not restricted, this indicates that the original challenges may have had sufficient training data, and that when the training pool is large enough, the advantages of TL become less impactful43. In Fig. 8, it is clear that models where TL was applied show better performance against training from randomly initialised weights. Although RadiologyNET models did not outperform ImageNet in less-restricted resource conditions on the GRAZPEDWRI-DX dataset (i.e. the results shown in Table 4), they showed competitive performance when training data and time were limited. However, it is important to note that as more training data becomes available (e.g. when the dataset is reduced to \(50\%\) instead of \(5\%\) of its original size), the performance differences between RadiologyNET and ImageNet become less pronounced. This suggests that the relative advantage of RadiologyNET pretraining may decrease as the availability of training data increases (as does the advantage of TL in general).

The radiologists’ evaluation of the generated heatmaps indicated that RadiologyNET models were perceived as the most reliable overall, focusing on the present pathologies better than ImageNet and (especially) Baseline. This result raises questions about the influence of TL on model interpretability, as patterns learned during pretraining might help models focus on relevant regions in the downstream tasks. While pretraining on natural images can provide generalisable features, pretraining on medical data may lead to models that are better adapted to the specific characteristics of medical images (e.g. disease-related patterns and abnormalities). However, testing this hypothesis further remains a topic for future research.

In the results presented in the RadImageNet study13, which evaluated transfer learning on a dataset of similar size to RadiologyNET but annotated by expert radiologists, the authors reported statistically significant improvements in model performance, with AUC increases of 1.9%, 6.1%, 1.7%, and 0.9% over ImageNet-pretrained models across five different medical tasks. While RadiologyNET-pretrained models achieved comparable results to ImageNet in our experiments (with notable difference visible in resource-limited conditions), the performance gains reported in the RadImageNet study highlight the value of high-quality expert annotations in enhancing the effectiveness of pretraining. Although both RadiologyNET and RadImageNet contain a similar number of images, RadImageNet includes 165 distinct labels, substantially more than the 36 labels used in RadiologyNET. This makes RadImageNet a more complex and challenging classification task, which likely encourages models to learn richer and more discriminative features. Nevertheless, RadiologyNET achieved competitive performance relative to ImageNet without the need for expert annotations, thereby avoiding the considerable human effort required to construct RadImageNet (an effort that involved 20 radiologists). These observations lead to several key insights: (i) Unsupervised labelling can be a viable strategy for constructing large-scale medical datasets for pretraining, provided that the task includes a sufficiently large number of classes to introduce meaningful complexity; (ii) High-quality labelled data remains the gold standard, but is often impractical due to the high cost and expertise required for annotation. In summary, we argue that a hybrid approach – starting with unsupervised pretraining and selectively annotating a subset of the most diagnostically challenging cases – may offer an effective compromise between scalability and annotation quality, particularly in the context of training medical foundation models61.

From the obtained results, we attempt to answer the following questions: (i) Does the domain of pretrained models affect performance? Yes. While RadiologyNET models demonstrated competitive results, ImageNet models exhibited a slight advantage on the RSNA PBA Challenge and the GRAZPEDWRI-DX dataset. This is likely due to their exposure to a broader range of images (which leads to more generalisable features); and the limited inclusion of wrist radiographs in the RadiologyNET dataset. On the other hand, the Brain Tumor MRI dataset showed that RadiologyNET models achieved faster convergence, likely due to RadiologyNET sharing significant overlap with the downstream task’s domain. To further explore the impact of pretraining domain characteristics, we compared models pretrained on single-modality (MR-only, CR-only and CT-only) data with those pretrained on multi-modality RadiologyNET data, which showed a general trend that incorporating diverse images into the pretraining dataset enables the model to generalise better in cases where intra-domain variability is low. Thus, when choosing pretrained models for medical ML tasks, one should consider the biases present in the dataset (e.g. the distribution of anatomical regions). (ii) Does the pretraining task matter? Yes, the pretraining task may play a key role. When choosing the pretraining task, one may need to consider what kind of features the model should learn. Our results from the LUNA Challenge indicate that classification-pretrained models outperform reconstruction-pretrained models in semantic segmentation tasks, producing vastly different output masks. This raises the issue of determining the most suitable pretraining task for the targeted problem type, as the reconstruction-pretrained models learned different features than those pretrained as classification. Based on the results, using reconstruction as a pretraining task for image segmentation is not ideal. Future research should explore other pretraining approaches, such as contrastive pretraining, to determine if they yield better performance. Moreover, learning generalisable representations from large datasets is fundamental to self-supervised learning, which is the underlying principle for many foundation models, such as Prov-GigaPath62. (iii) Is TL always beneficial? Our findings suggest that TL is generally beneficial, especially in conditions where training pools were reduced and/or training time was limited. However, there were cases where Baseline models achieved comparable performance to those trained from pretrained weights, and there is evidence to show that, when models are not resource-restricted (e.g. there is enough training time/data), the utility of TL becomes less prominent43. Furthermore, in the case of reconstruction-pretrained U-Net, models trained from randomly initialised weights surpassed those of ImageNet and RadiologyNET by a statistically significant margin, meaning that some TL models may even hinder performance. This question is closely tied to questions (i) and (ii), as the benefits of using TL depend on the alignment between the pretraining domain/task and the target domain/task, and (if the domains do not overlap significantly) the generalisability of the learned features in the pretrained models. (iv) What should be considered when collecting data for pretraining medical models for TL? Our findings suggest that a well-structured dataset containing challenging and diverse classes is more beneficial than a homogeneous one. This aligns with observations from the field of language processing, where general-domain corpora have been shown to enhance domain-specific performance. For example, GatorTron63 incorporated data from Wikipedia, and Med-PaLM64 was built on general-purpose language models. These insights suggest that diverse pretraining datasets improve generalisation, and that incorporating heterogeneity (e.g., through natural image datasets such as ImageNet) can be beneficial when developing medical foundation models. This raises a key question for future research: how can diverse data sources (both within and beyond the medical domain) be effectively integrated to optimise the training of medical foundation models? Similarly, the next question which arises from RadiologyNET pseudo-labels is: (v) How to associate labels to cases for effective transfer learning using an unsupervised approach? In case of RadiologyNET as explained in the paper17, the labels were formed as a concatenation of three vectors extracted from the three different sources belonging to same case: diagnosis text, image and DICOM tags. The vectors, or to be precise embeddings, were extracted by using autoencoders-based models54. This yielded representations which can be classified as unsupervised data construction where the case is represented by its compressed version (which can be noisy). It is highly possible that important features of the observed case will not be preserved and its unique and important features, such as tumour presence or fracture, might be lost. On the other hand, unsupervised representation learning60 might be a better way to preserve important clinical features which could lead to more versatile and demanding classes forcing models to learn more complex features. Therefore, one of the limitations of this study is using a small number (36) of potential simple clusters that did not force models to learn complex and advanced features.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates the effectiveness of TL in improving the performance of deep learning models for medical image analysis. While ImageNet models showed better generalisability, RadiologyNET models demonstrated better performance in resource-limited conditions. Furthermore, this study showed how different biases present in the pretraining dataset may influence performance on the downstream task, as RadiologyNET models performed better where the downstream task’s domain aligned closely with the data used during pretraining. Thus, the current version of RadiologyNET foundation models is the most impactful when applied to (i) resource-limited tasks in the medical domain, and (ii) when the downstream task aligns with the RadiologyNET dataset. One major limitation to acknowledge is the nature of the RadiologyNET dataset being single-clinic. By incorporating data from other clinics, the biases currently present in RadiologyNET could be mitigated and future versions of RadiologyNET foundation models could be more efficiently applied to a wider range of downstream medical tasks. The current RadiologyNET foundation models are publicly available at https://github.com/AIlab-RITEH/RadiologyNET-TL-models.

Based on this study’s findings, we strongly suggest researchers clearly state the justification for using pretrained models. To be precise, this includes the pretraining task and its link to the target task, the (potential) biases present in the pretraining dataset, and the (in)sufficiency of samples in the available target dataset.

In future work, we plan to build on our current findings by: (i) augmenting RadiologyNET with additional data sourced from various clinics, (ii) providing a broader range of pretrained RadiologyNET models, (iii) evaluating their robustness in comparison with other foundational models in medical radiology, (iv) exploring effective strategies for model pretraining to enhance transfer learning, (v) extending research on segmentation models by replacing the reconstruction task with contrastive pretraining methods, (vi) merging natural data with medical data in pretraining tasks, and (vii) experimenting with unsupervised representation learning for more complex auto-assigned labels.

Data availability

Due to restrictions imposed by the current Ethics Committee approval, the dataset used in this study is not available for sharing. However, the entire program code and foundation models (i.e. pretrained model weights) used for the experiments are available at https://github.com/AIlab-RITEH/RadiologyNET-TL-models.

References

Han, X. et al. Pre-trained models: Past, present and future. AI Open 2, 225–250. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aiopen.2021.08.002 (2021).

Kim, H. E. et al. Transfer learning for medical image classification: A literature review. BMC Med. Imaging22. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12880-022-00793-7 (2022).

Krizhevsky, A., Sutskever, I. & Hinton, G. E. ImageNet classification with deep convolutional neural networks. Commun. ACM 60, 84–90. https://doi.org/10.1145/3065386 (2017).

Deng, J. et al. ImageNet: A large-scale hierarchical image database. In 2009 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 248–255. https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPR.2009.5206848 (2009).

Ke, A., Ellsworth, W., Banerjee, O., Ng, A.Y. & Rajpurkar, P. CheXtransfer: performance and parameter efficiency of ImageNet models for chest X-Ray interpretation. In Proceedings of the Conference on Health, Inference, and Learning, ACM CHIL ’21. https://doi.org/10.1145/3450439.3451867 (ACM, 2021).

Woerner, S. & Baumgartner, C. F. Navigating data scarcity using foundation models: A benchmark of few-shot and zero-shot learning approaches in medical imaging. In Foundation Models for General Medical AI (Deng, Z. et al., eds), 30–39. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-73471-74 (Springer, 2025).

Qiu, Y., Lin, F., Chen, W. & Xu, M. Pre-training in medical data: A survey. Mach. Intell. Res. 20, 147–179. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11633-022-1382-8 (2023).

Cheplygina, V., de Bruijne, M. & Pluim, J. P. Not-so-supervised: A survey of semi-supervised, multi-instance, and transfer learning in medical image analysis. Med. Image Anal. 54, 280–296. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.media.2019.03.009 (2019).

Atasever, S., Azginoglu, N., Terzi, D. S. & Terzi, R. A comprehensive survey of deep learning research on medical image analysis with focus on transfer learning. Clin. Imaging 94, 18–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinimag.2022.11.003 (2023).

Mustafa, B. et al. Supervised transfer learning at scale for medical imaging. https://doi.org/10.48550/ARXIV.2101.05913 (2021).

Wen, Y., Chen, L., Deng, Y. & Zhou, C. Rethinking pre-training on medical imaging. J. Vis. Commun. Image Represent. 78, 103145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvcir.2021.103145 (2021).

Zhang, S. et al. BiomedCLIP: A multimodal biomedical foundation model pretrained from fifteen million scientific image-text pairs. https://doi.org/10.48550/ARXIV.2303.00915 (2023).

Mei, X. et al. RadImageNet: An open radiologic deep learning research dataset for effective transfer learning. Radiol. Artif. Intell.4. https://doi.org/10.1148/ryai.210315 (2022).

Silva-Rodríguez, J., Dolz, J. & Ayed, I.B. Towards foundation models and few-shot parameter-efficient fine-tuning for volumetric organ segmentation. In Medical Image Computing and Computer Assisted Intervention: MICCAI 2023 Workshops, 213–224. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-47401-921 (Springer, 2023).

Zhou, H.-Y. et al. Comparing to Learn: Surpassing ImageNet pretraining on radiographs by comparing image representations. In Medical Image Computing and Computer Assisted Intervention: MICCAI 2020, 398–407. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-59710-839 (Springer, 2020).

Alzubaidi, L. et al. MedNet: Pre-trained convolutional neural network model for the medical imaging tasks. http://arxiv.org/abs/2110.06512 (2021).

Napravnik, M., Hržić, F., Tschauner, S. & Štajduhar, I. Building RadiologyNET: An unsupervised approach to annotating a large-scale multimodal medical database. BioData Mining17. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13040-024-00373-1 (2024).

Li, X. et al. Ragcn: Region aggregation graph convolutional network for bone age assessment from x-ray images. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 71, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1109/TIM.2022.3190025 (2022).

Li, X. et al. Msfr-net: Multi-modality and single-modality feature recalibration network for brain tumor segmentation. Med. Phys.50, 2249–2262. https://doi.org/10.1002/mp.15933 (2023).

Ronneberger, O., Fischer, P. & Brox, T. U-Net: Convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation. In Medical Image Computing and Computer-Aafssisted Intervention: MICCAI 2015, 234–241. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-24574-4_28 (Springer International Publishing, 2015).

Li, X. et al. Vision-language models in medical image analysis: From simple fusion to general large models. Inf. Fusion 118, 102995. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.inffus.2025.102995 (2025).

Cheplygina, V., de Bruijne, M. & Pluim, J. P. W. Not-so-supervised: A survey of semi-supervised, multi-instance, and transfer learning in medical image analysis. Med. Image Anal. 54, 280–296 (2019).

He, K., Zhang, X., Ren, S. & Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), https://doi.org/10.1109/cvpr.2016.90 (IEEE, 2016).

Simonyan, K. & Zisserman, A. very deep convolutional networks for large-scale image recognition. https://doi.org/10.48550/ARXIV.1409.1556 (2014).

Tan, M. & Le, Q. EfficientNet: Rethinking model scaling for convolutional neural networks. In Proceedings of the 36th International Conference on Machine Learning, vol. 97 of Proceedings of Machine Learning Research, 6105–6114 (PMLR, 2019).

Szegedy, C., Vanhoucke, V., Ioffe, S., Shlens, J. & Wojna, Z. Rethinking the inception architecture for computer vision. In 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR). https://doi.org/10.1109/cvpr.2016.308 (IEEE, 2016).

Huang, G., Liu, Z., Van Der Maaten, L. & Weinberger, K. Q. Densely connected convolutional networks. In 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR). https://doi.org/10.1109/cvpr.2017.243 (IEEE, 2017).

Howard, A. et al. Searching for MobileNetV3. In 2019 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV). https://doi.org/10.1109/iccv.2019.00140 (IEEE, 2019).

Halabi, S. S. et al. The RSNA pediatric bone age machine learning challenge. Radiology 290, 498–503. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.2018180736 (2019).

Rahman, T. et al. Exploring the effect of image enhancement techniques on COVID-19 detection using chest X-ray images. Comput. Biol. Med. 132, 104319. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compbiomed.2021.104319 (2021).

Chowdhury, M. E. H. et al. Can AI help in screening viral and COVID-19 Pneumonia?. IEEE Access 8, 132665–132676. https://doi.org/10.1109/access.2020.3010287 (2020).

Nagy, E., Janisch, M., Hržić, F., Sorantin, E. & Tschauner, S. A pediatric wrist trauma X-ray dataset (GRAZPEDWRI-DX) for machine learning. Sci. Data9. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-022-01328-z (2022).

Nickparvar, M. Brain tumor MRI dataset. https://www.kaggle.com/dsv/2645886. https://doi.org/10.34740/KAGGLE/DSV/2645886 (2021).

Armato, S. G. et al. Validation, comparison, and combination of algorithms for automatic detection of pulmonary nodules in computed tomography images: The LUNA16 challenge. Med. Image Anal. 42, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.media.2017.06.015 (2017).

Yan, K., Wang, X., Lu, L. & Summers, R. M. DeepLesion: Automated mining of large-scale lesion annotations and universal lesion detection with deep learning. J. Med. Imaging 5, 036501. https://doi.org/10.1117/1.JMI.5.3.036501 (2018).

Irvin, J. et al. Chexpert: A large chest radiograph dataset with uncertainty labels and expert comparison. Proc. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell. 33, 590–597. https://doi.org/10.1609/aaai.v33i01.3301590 (2019).

Wang, X. et al. Chestx-ray8: Hospital-scale chest x-ray database and benchmarks on weakly-supervised classification and localization of common thorax diseases. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) (2017).

Johnson, A. E. W. et al. Mimic-cxr, a de-identified publicly available database of chest radiographs with free-text reports. Sci. Data 6, 317. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-019-0322-0 (2019).

Siragusa, I., Contino, S., Ciura, M.L., Alicata, R. & Pirrone, R. Medpix 2.0: A comprehensive multimodal biomedical data set for advanced ai applications with retrieval augmented generation and knowledge graphs (2025). http://arxiv.org/abs/2407.02994.

Rajpurkar, P. et al. Mura: Large dataset for abnormality detection in musculoskeletal radiographs (2018). http://arxiv.org/abs/1712.06957.

Marcus, D. S. et al. Open access series of imaging studies (oasis): Cross-sectional mri data in young, middle aged, nondemented, and demented older adults. J. Cogn. Neurosci.19, 1498–1507. https://doi.org/10.1162/jocn.2007.19.9.1498 (2007).

Glorot, X. & Bengio, Y. Understanding the difficulty of training deep feedforward neural networks. In Proceedings of the Thirteenth International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Statistics, vol. 9, Proceedings of Machine Learning Research, 249–256 (PMLR, 2010).

He, K., Girshick, R. & Dollar, P. Rethinking imagenet pre-training. In 2019 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV). https://doi.org/10.1109/iccv.2019.00502 (IEEE, 2019).

Pai, S. et al. Vision foundation models for computed tomography (2025). http://arxiv.org/abs/2501.09001.

Codella, N. C.F. et al. Medimageinsight: An open-source embedding model for general domain medical imaging (2024). http://arxiv.org/abs/2410.06542.

DICOM Standards Committee. DICOM Standard . https://www.dicomstandard.org/. Accessed 5 Jul 2024.

Loshchilov, I. & Hutter, F. Fixing Weight Decay Regularization in Adam. (2017). http://arxiv.org/abs/1711.05101.

Alam, S., Tomar, N. K., Thakur, A., Jha, D. & Rauniyar, A. Automatic polyp segmentation using u-net-resnet50 (2020). http://arxiv.org/abs/2012.15247.

Aboussaleh, I., Riffi, J., Fazazy, K.E., Mahraz, M.A. & Tairi, H. Efficient U-Net architecture with multiple encoders and attention mechanism decoders for brain tumor segmentation. Diagnostics13 (2023).

Mukasheva, A. et al. Modification of u-net with pre-trained resnet-50 and atrous block for polyp segmentation: Model taspp-unet. Eng. Proc.70. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2024070016 (2024).

Liu, W. et al. Automatic lung segmentation in chest X-ray images using improved U-Net. Sci. Rep.12. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-12743-y (2022).

Armato, S. G. et al. The Lung Image Database Consortium (LIDC) and Image Database Resource Initiative (IDRI): A Completed Reference Database of Lung Nodules on CT Scans. Med. Phys. 38, 915–931. https://doi.org/10.1118/1.3528204 (2011).

Mikulić, M. et al. Balancing performance and interpretability in medical image analysis: Case study of osteopenia. J. Imaging Inf. Med. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10278-024-01194-8 (2024).

Li, P., Pei, Y. & Li, J. A comprehensive survey on design and application of autoencoder in deep learning. Appl. Soft Comput. 138, 110176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asoc.2023.110176 (2023).

Schultz, B. B. Levene’s test for relative variation. Syst. Biol.34, 449–456, https://doi.org/10.1093/sysbio/34.4.449 (1985).

Kruskal, W. H. & Wallis, W. A. Use of ranks in one-criterion variance analysis. J. Am. Stat. Assoc.47, 583–621, https://doi.org/10.1080/01621459.1952.10483441 (1952).

Müller, D., Soto-Rey, I. & Kramer, F. Towards a guideline for evaluation metrics in medical image segmentation. BMC Res.Notes15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-022-06096-y (2022).

Courty, B. et al. mlco2/codecarbon: v2.4.1. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.11171501 (2024).

Selvaraju, R. R. et al. Grad-CAM: Visual explanations from deep networks via gradient-based localization. Int. J. Comput. Vision 128, 336–359. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11263-019-01228-7 (2019).

Saunshi, N., Plevrakis, O., Arora, S., Khodak, M. & Khandeparkar, H. A theoretical analysis of contrastive unsupervised representation learning. In Proceedings of the 36th International Conference on Machine Learning, vol. 97, (Chaudhuri, K. & Salakhutdinov, R., eds) Proceedings of Machine Learning Research, 5628–5637 (PMLR, 2019).

Wu, X. et al. A survey of human-in-the-loop for machine learning. Futur. Gener. Comput. Syst. 135, 364–381. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.future.2022.05.014 (2022).

Xu, H. et al. A whole-slide foundation model for digital pathology from real-world data. Nature 630, 181–188. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-07441-w (2024).

Yang, X. et al. A large language model for electronic health records. NPJ Dig. Med. 5, 194. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-022-00742-2 (2022).

Singhal, K. et al. Towards expert-level medical question answering with large language models (2023). http://arxiv.org/abs/2305.09617.

Acknowledgements

This work has been fully supported by the Croatian Science Foundation [grant number IP-2020-02-3770] and by the University of Rijeka (grant number uniri-mladi-tehnic-23-19 3070). We also gratefully acknowledge the invaluable contribution of Sebastian Tschauner, whose insights and ideas have greatly influenced and guided our research efforts.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.N., F.H. and I.Š. developed the concept and planned the experiment. M.N. and F.H. performed the experiment. M.N., F.H., M.U. and D.M. analysed the data and interpreted the results. D.M and I.Š. provided the data. I.Š. supervised the experiment and acquired the project funding. M.N. wrote the manuscript with input from F.H., M.U. and I.Š. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This research was approved by the competent Ethics Committee of Clinical Hospital Centre Rijeka, Croatia [Class: 003-05/16-1/102, Reg.No. 2170-29-02/1-16-3].

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Napravnik, M., Hržić, F., Urschler, M. et al. Lessons learned from RadiologyNET foundation models for transfer learning in medical radiology. Sci Rep 15, 21622 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-05009-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-05009-w