Abstract

Accurate classification of biomedical signals is crucial for advancing non-invasive diagnostic methods, particularly for identifying gastrointestinal and related medical conditions where conventional techniques often fall short. An ensemble learning framework was developed by integrating Random Forest, Support Vector Machines (SVM), and Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN) to classify spectrogram images generated from percussion and palpation signals. The framework employs Short-Time Fourier Transform (STFT) to extract spectral and temporal information, enabling accurate signal processing and classification into distinct anatomical regions. The ensemble model combines the strengths of its components: Random Forest mitigates overfitting, SVM handles high-dimensional data, and CNN extracts spatial features within a robust preprocessing pipeline to ensure data consistency. By achieving a classification accuracy of 95.4%, the ensemble framework outperformed traditional classifiers in capturing subtle diagnostic variations. This method offers a robust solution for biomedical signal classification and has potential applications in clinical diagnostics. Future research directions include real-time clinical integration and multi-modal data incorporation to further enhance its applicability.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In clinical environments, biological signal processing is essential for augmenting diagnostic accuracy and boosting patient care. Traditional diagnostic techniques, such as percussion, auscultation, and palpation, remain widely used, but often result in inconsistent and highly variable outcomes, reducing diagnostic reliability1,2. With the increasing complexity of medical conditions, the need for objective, accurate, and less error-prone diagnostic methods continues to grow3,4

Managing spectrogram data from physical tests remains a challenge, despite significant advancements in biomedical signal processing. Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), commonly employed for image classification, frequently encounter challenges in real-time clinical applications, especially when faced with sparse or noisy datasets, due to their substantial computing requirements and vulnerability to overfitting7,8. To overcome these difficulties, it is critical to develop a dependable and precise model capable of processing complex biomedical signals while maintaining consistent performance across multiple datasets.

Biomedical signal classification requires extraction of meaningful features from raw data to achieve accurate and consistent diagnostic results. The Short-Time Fourier Transform (STFT) is a popular technique for converting biological signals into spectrograms, providing a time-frequency representation that captures crucial temporal and spectral properties5,6. Leveraging advanced machine learning techniques such as Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), Random Forest (RF), and Support Vector Machines (SVMs) has shown potential in improving classification accuracy by effectively analyzing these spectrograms6. Such methods can differentiate between various signal patterns, thereby contributing to more objective and reliable diagnostic outcomes.

The ensemble model combines the strengths of Random Forest for reducing overfitting, CNN for spatial feature extraction, and SVM for handling high-dimensional data. This hybrid approach improves classification performance compared to single-model methods, providing a robust solution for analyzing noisy and complex biomedical signals9,10. With a classification accuracy of 95.4%, tested using spectrograms from percussion and palpation signals, the model demonstrated its ability to detect clinically significant patterns11,12.

To ensure data consistency and maximize model performance, this study incorporated a comprehensive preprocessing pipeline, including normalization, resizing, and feature extraction13. These preprocessing methods improve the quality of the input data and reduce variability, hence increasing model reliability. By minimizing subjective errors, this ensemble framework facilitates faster, more objective, and non invasive diagnostic applications, contributing significantly to clinical diagnostics.

This study introduced several aspects. First, it focuses on the classification of percussion and palpation signals, which remains underexplored in biomedical signal research. Second, it uses a hybrid ensemble framework that combines CNN, SVM, and Random Forest classifiers, each with complimentary characteristics that improve the accuracy and robustness of spectrogram categorization. Third, the study used spectrograms obtained from the Short-Time Fourier Transform (STFT), which preserved both temporal and frequency characteristics, to test categorization across eight different anatomical locations using a naturally balanced dataset. These innovations differentiate this study from prior studies that predominantly target auscultation signals or rely on single-model classification approaches.

Despite the increased interest in machine learning for biomedical applications, the classification of biological signals such as those obtained from percussion and palpation is still underexplored. These signals are often noisy, have overlapping frequency characteristics, and vary across individuals, which makes it difficult for traditional models to provide reliable diagnostic support. This problem is further compounded by the lack of standardized, objective interpretation protocols in clinical practice, leading to inconsistent diagnoses. This study was motivated by the need to build an automated, accurate, and interpretable system capable of classifying spectrograms from such signals into anatomical regions. This study intends to improve the diagnostic precision and reliability of non-invasive physical examinations through the use of ensemble learning and spectrogram-based analysis.

Key contributions:

-

A robust ensemble learning framework was developed that incorporates CNN, SVM, and Random Forest classifiers for accurate biomedical signal classification.

-

Achieved a classification accuracy of 95.4%, enhancing diagnostic precision in clinical applications.

-

A comprehensive preprocessing pipeline was establied to ensure dataset consistency, thereby enabling real-time diagnostic applicability.

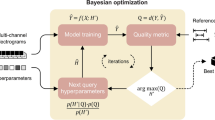

A structured approach is required for good biological signal classification. To increase classification performance, an ensemble learning technique was used, combining CNN, SVM, and Random Forest classifiers. The ensemble learning method explicitly classifies spectrograms into eight anatomical regions, ensuring that region-specific signal patterns can be distinguished accurately. This strategy guarantees the dependable and precise classification of biological signals by integrating the capabilities of different classifiers. The procedure is illustrated in Fig. 1.

The classification framework explicitly distinguishes spectrograms corresponding to distinct anatomical locations, ensuring region-specific categorization for enhanced diagnostic precision. A robust ensemble learning framework was presented for biomedical signal classification, demonstrating high accuracy and clinical relevance. The methodology, experimental outcomes, and implications of this strategy are explored in detail in the following sections.

Literature review

Spectrograms have emerged as a valuable tool for providing time-frequency representations of biomedical signals, particularly for enhancing diagnostic techniques, such as percussion and palpation. These methods, traditionally reliant on subjective clinical assessments, benefit significantly from spectrogram analysis owing to their ability to reduce noise and clarify signal patterns. For instance, spectrogram-based approaches have improved the classification of lung sounds, enhancing the objectivity and diagnostic precision in clinical settings14. Modern advancements such as electronic stethoscopes have further validated the clinical utility of spectrogram processing for enhancing signal-based evaluations15.Comparative studies highlight the effectiveness of incorporating machine learning into signal-based physical examinations, demonstrating that algorithms such as k-nearest neighbors (kNN) and Support Vector Machines (SVMs) can efficiently diagnose respiratory disorders by analyzing pulmonary acoustic signals16.

Machine learning models, such as SVMs and Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), have shown extraordinary efficacy in processing the data received during percussion and palpation. By identifying subtle variations in biological signals, these techniques enhance the reliability of diagnostic assessments, which traditional physical methods often miss. For example, electronic stethoscopes combined with machine learning frameworks have been successfully employed to identify abnormal patterns, thereby improving their practical utility in clinical applications17,18. Advanced wireless devices effectively showcase their efficacy in practical diagnostic applications, including pneumonia diagnosis via signal analysis, thus enhancing the significance of machine learning in physical examinations19,20. These studies have highlighted the importance of using machine learning to improve the precision and objectivity of signal-based diagnostic approaches21.

Ensemble learning methods have become increasingly relevant in biomedical signal processing becasue of their ability to combine predictions from multiple classifiers, thereby improving the classification accuracy. Notably, studies on heart-sound analysis have demonstrated how convolutional deep neural networks enhance the precision of physical examination signals, enabling robust diagnostic outcomes22. Furthermore, portable auscultation devices equipped with machine learning models have shown promise in facilitating the real-time analysis of percussion and palpation signals, supporting their integration into modern diagnostic workflows23,24. Ensemble learning has emerged as an important tool for improving signal-based procedures that produce reliable clinical insights.

Deep learning frameworks, like as CNNs and Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks, improve the interpretation of time-dependent biological signals by detecting critical features in raw data. These models improve the efficiency and accuracy of signal classification, making them ideal sophisticated diagnostic tools. For instance, Bluetooth connected stethoscopes using machine learning algorithms enable real-time analysis and remote monitoring of biological signals, improving clinical accessibility and accuracy25. Similarly, wearable devices intended for continuous surveillance have proven to be beneficial in the long-term analysis of signals, highlighting the growing role of deep learning in enhancing the effectiveness of physical examination techniques26. Hybrid models, which combine classical machine learning and deep learning, have also proven efficacious in identifying aberrant signals such as crackles and rhonchi27.

The accurate classification of biomedical signals, particularly those derived from percussion and palpation, relies heavily on effective preprocessing and feature extraction techniques. Employing techniques such as the Short-Time Fourier Transform (STFT), raw data can be converted into time-frequency representations, facilitating the extraction of essential components necessary for signal classification28. Traditional machine learning models, including SVMs and Gaussian Mixture Models (GMMs), have demonstrated success in distinguishing biological signals based on optimized features, thus improving diagnostic reliability29. Furthermore, the accuracy and clinical usability of these models for signal classification tasks have been further enhanced by the patient-specific fine-tuning of deep neural networks30,31.

Recent advancements in machine learning have further demonstrated its value in biomedical signal classification, addressing challenges such as variability in signal quality and noise. Deep learning frameworks and recurrent neural networks have shown potential for detecting abnormalities and enhancing diagnostic assessments in clinical practice32,33. Robust models that combine convolutional and recurrent architectures have successfully managed noisy signals, paving the way for more reliable diagnostic tools34. These advancements emphasize the importance of integrating machine-learning techniques into signal-based physical examination methods, enabling precise and objective diagnostic outcomes in modern healthcare settings35.

Recent quality-indexed research has focused on hybrid intelligent systems and optimization-driven machine-learning frameworks for disease classification. Several studies have proposed advanced ensemble methods and optimization strategies, such as optuna-based hyperparameter tuning, to enhance the diagnostic performance in heart disease detection74,75. These frameworks show notable improvements in precision and generalization, are often validated through rigorous cross-validation, and are tested under variable train-test ratios76,78. In particular, studies have identified limitations related to class imbalance, overfitting, and the lack of multiclass or region-specific classification. While such models perform well in cardiovascular applications, they do not extend to biomedical signals, such as percussion or palpation, nor do they incorporate spectrogram-based classification frameworks. This study fills this gap by proposing an ensemble framework integrating CNN, SVM, and RF, optimized for multi-region classification using spectrograms from percussion and palpation signals across eight anatomical areas77 (Table 1).

Related work

Deep and ensemble learning techniques have advanced significantly, allowing machine learning methods for biological signal classification to be adopted more widely. Conventional diagnostic techniques, such as auscultation and palpation, depend heavily on the subjective assessments of doctors, leading to considerable variability in diagnostic results. This reliance on subjectivity has intensified the demand for automated and objective methods to improve the diagnostic accuracy and dependability. When integrated with machine learning models like Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) and ensemble classifiers, spectrogram-based algorithms provide reliable solutions for increasing diagnostic consistency and minimizing variability during physical examinations.

Spectrograms provide detailed time-frequency representations of biomedical signals, making them invaluable for analyzing respiratory sounds and other biological data. These representations facilitate the improved interpretability of complex signals and enhance classification accuracy. For example, spectrogram-based approaches have been widely used to study respiratory sounds, allowing for the exact identification of anomalies such as wheezes and crackles36. Such advances emphasize the potential of spectrogram-based methods to deliver objective and accurate diagnostic insights for physical examination.

Improvements in computerized respiratory sound analysis have mitigated the difficulties associated within diagnosing respiratory disorders by increasing the accuracy and objectivity of auscultation methods. Machine learning methods facilitate automatic classification of respiratory sounds and provide consistent and reliable diagnostic instruments37. Additionally, convolutional neural networks have considerably improved the diagnosis of respiratory disorders, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)38,39. These advancements highlight the growing impact of spectrogram-based methodologies on advancing respiratory diagnostics.

Machine learning techniques such as Support Vector Machines (SVMs) and Random Forests have been demonstrated to be effective for respiratory sound classification. These models are capable of handling large datasets and extracting meaningful features, thereby reducing subjectivity in diagnostic processes40. Foundational studies on the mechanisms of lung sounds and the development of objective auscultation tools have laid the groundwork for integrating machine learning techniques into clinical diagnostics41,42. These developments demonstrate the significant role of machine learning inthe enhancement of traditional diagnostic methods.

Ensemble learning techniques, which aggregate predictions from multiple models, have been increasingly applied in biomedical signal analysis to improve the classification accuracy. Such methods are particularly effective for managing the noise and variability associated with biological signals43. For instance, ensemble-based models have successfully analyzed the spectral characteristics of normal breath sounds, demonstrating their ability to extract critical features for classification44. Advances in breath sound recording and analysis have further established ensemble learning as a cornerstone for the development of accurate and reliable diagnostic tools45.

The integration of multi-modal learning approaches, which incorporate data from diverse sources, has proven valuable for improving diagnostic reliability and accuracy. For example, spectral analyses of chest wall breath sounds have provided vital insights into both normal and abnormal respiratory patterns, thus forming the basis for modern diagnostic systems46. Research on inspiratory and expiratory crackle mechanisms has further emphasized the importance of understanding sound generation in refining classification models47. Furthermore, the potential of integrating hardware and software solutions for precise and objective diagnostics has been demonstrated through the automated analysis of crackles in diseases such as interstitial pulmonary fibrosis48.

Feature extraction and preprocessing remain essential for enhancing the capacity of machine-learning algorithms to classify biological inputs. Effective preprocessing approaches are crucial for ensuring the trustworthiness of the input data, as evidenced by studies on fine and coarse crackles49. Foundational research on the functional basis of pulmonary sounds has further underscored the necessity of accurate feature extraction to effectively capture diagnostic information, ultimately improving classification outcomes50.

Methodology

Problem statement

This study examined the shortcomings of conventional diagnostic techniques, which frequently depend on subjective clinical evaluations, especially in the categorization of biological signals produced by percussion and palpation. These procedures may result in diagnostic heterogeneity due to disparities in practitioner knowledge and experience. This study intended to improve diagnostic accuracy and consistency using objective signal classification.

The fundamental challenge is separating signals with overlapping frequency characteristics, which is a prevalent problem in biological data. To solve this, an ensemble learning system was developed, which combines Support Vector Machines (SVM), Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN), and Random Forest classifiers. This hybrid strategy relies on the following:

-

SVM: for its ability to handle high-dimensional data.

-

CNN: for extracting complex spatial and temporal features from spectrogram images.

-

Random Forest: for reducing overfitting and enhancing generalizability.

The methodology specifically focuses on classifying spectrogram images into distinct anatomical regions. By optimizing the hyperparameters through GridSearchCV and implementing preprocessing techniques (e.g., noise reduction and data normalization), the objective was to achieve robust classification performance. The goal was to exceed the classification accuracy of 90% while maintaining consistency across different regions, thereby bridging the gap between subjective and objective diagnostic approaches.

Dataset

The dataset used in this study was collected from the “iApp: An Autonomous Inspection, Auscultation, Percussion, and Palpation Platform”73. This dataset consisted of 18,240 spectrograms generated from biological signals obtained through palpation and percussion across eight distinct anatomical regions. A total of 38 individuals participated in the study, and contributing signals were recorded for both percussion (per) and palpation (pal) protocols.

Participant demographics: Although the dataset does not include detailed demographic metadata, such as age or clinical diagnosis, it contains recordings from both male and female participants, as evident from the original participant IDs (e.g., S01_M_144, S11_F_96). For this study, signals from nine representative subjects (S01–S09) were selected to ensure a balanced coverage of all eight anatomical regions. This subset includes diverse signal patterns derived from varying body compositions and recording contexts, which contribute to the robustness and generalization of the model.

Data collection: The signals were captured using a physiological sound transducer (TSD108, BIOPAC Systems) and a custom-built mechanical actuator for percussion and palpation. The auscultation, percussion, and palpation operations were all handled by a BIOPAC MP150 data collecting device. The dataset included the following:

-

Signal type: The collected signals included sound waves from palpation and percussion, which were processed into spectrograms for classification.

-

Sampling rate: The auscultation signals were sampled at 10,000 Hz, while percussion and palpation signals were sampled at 312 Hz.

-

Recording length: Each measurement lasted for 11.5 seconds.

-

Processing: To guarantee consistent and high-quality data, the raw time-series signals were checked before transformation. The Short-Time Fourier Transform (STFT) was only employed to convert sound information from palpation and percussion into spectrograms51. This process converts time-domain sound data into frequency representations, enabling comprehensive temporal and spectral analyse to improve the classification accuracy.

-

Model input: Each instance fed into the model consist of a single spectrogram image, either from palpation or percussion. The model was trained separately for both signal types to maintain distinct classification pathways.

Table 2 provides a comprehensive summary of the datasets used in the study. The dataset comprised spectrograms converted from raw sound signals obtained via percussion and palpation, covering eight distinct anatomical regions. Each spectrogram was labeled according to a region mapping scheme derived from participant IDs. As shown in the output logs, the dataset includes an approximately equal number of samples per class, making class-balancing unnecessary. This natural balance improves the reliability and generalization of the model without oversampling or synthetic augmentation methods for the class distribution.

This transformation ensures accurate categorization of biological signals by preserving localized frequency variations51. Spectrograms provide important insights into the time-frequency structure of biological signals, helping models distinguish between signals with comparable properties. Incorporating these time-frequency oscillations enables the model to identify subtle patterns that may be missed in the raw time-domain inputs. Spectrograms are particularly useful for distinguishing the overlapping frequency components.

Each spectrogram was labeled based on its corresponding anatomical region, ensuring a well-defined classification structure that reflected regional signal variations.

Label validation: The anatomical region labels used in this study were derived from a structured folder organization within the iApp dataset, where each folder corresponds to a specific palpation or percussion region recorded during data collection. These mappings were based on the standardized region identifiers used in the original acquisition protocol by trained clinical staff. Although direct expert annotation for each spectrogram was not performed during this study, the original dataset was collected under clinical supervision with region-specific naming conventions to ensure anatomical accuracy.

The STFT can be numerically represented as follows:

The window function w(t) retains the localized frequency information over time, whereas the STFT signal x(t) is represented by S(t, f) in this equation. This transformation is a crucial stage of the classification process, as it provides a visual depiction of the frequency components over time52. The dataset helps the model enable diagnostic applications by concentrating on clinically relevant spectrograms that represent eight anatomical areas.

Preprocessing

All spectrograms were scaled to 128 \(\times\) 128 pixels and normalized to a range of [0,1] to ensure uniformity across the dataset. Each spectrogram was assigned a label corresponding to one of the eight anatomical regions, reinforcing the region-specific classification. This labeling was essential for preserving the anatomical distinctions between signals, minimizing intra-class variability, and ensuring robust classification.

To maintain distinct class distributions, preprocessing techniques were applied to prevent potential overlaps in regional signal patterns. Standardization ensured that the frequency characteristics of each spectrogram were preserved, thereby enhancing the reliability of the classification process.

Normalization was carried out using the following formula:

where X is the raw pixel intensity value of the spectrogram and \(\min (X)\) and \(\max (X)\) denote the minimum and maximum pixel values, respectively53. This normalization step was crucial in improving the convergence of machine learning, models during training, ensuring efficient learning and reducing sensitivity to variations in pixel intensity.

Moreover, preprocessing plays a pivotal role in reducing noise artifacts and enhancing the classification accuracy by ensuring consistent input distributions across all eight anatomical regions54. These refinements ultimately strengthen the generalizability of the model while retaining crucial frequency and spatial information.

Data augmentation: To enhance generalization and mitigate overfitting, data augmentation was applied during CNN training using the Keras ImageDataGenerator module. The augmentation pipeline uses random rotations (±10 degrees), width and height changes (±10%), and horizontal flipping. These changes imitate real-world variability in biological signals, increasing model resilience.

Model architecture

The ensemble learning model presented in this framework included three classifiers: Random Forest (RF), Support Vector Machines (SVM), and Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN). This hybrid strategy makes use of each algorithm’s unique advantages: SVM effectively manages high-dimensional data, CNN concentrates on extracting spatial features from spectrogram images, and RF improves resilience by reducing overfitting through ensemble averaging55.

The model selection was based on the complementary strengths of each classifier. CNN is effective at learning hierarchical spatial patterns from spectrogram images, SVM excels in separating classes in high-dimensional feature spaces, and RF provides robustness by reducing variance through ensemble averaging. Their combination ensures a balance between representation learning, decision boundary optimization, and variance reduction.

Convolutional neural network (CNN)

CNNs are well-known for their performance in image classification applications. In this study, a hierarchical CNN architecture is used to extract spatial characteristics from spectrogram images generated by biological signals.

Input shape: Each input to the CNN consisted of a single spectrogram image (either from palpation or percussion) resized to 128 \(\times\) 128 pixels with one grayscale channel. The model was independently trained for palpation and percussion spectrograms.

The convolution operation is mathematically defined as:

where f represents the input signal and g is the convolutional filter or kernel. This operation allows the model to detect patterns, edges, and textures in spectrogram images.

Each convolutional layer is followed by a Rectified Linear Unit (ReLU) activation function, defined as.

Pooling layers, particularly max pooling, are applied to reduce the spatial dimensions while preserving important features. Max pooling is defined as.

where X is the input feature map and Y is the pooled output.

The output of the final dense layer uses the softmax activation function to generate probability distributions across the eight anatomical regions.

where \(z_c\) is the input to the output neuron for class c, and \(K=8\) is the number of output classes.

CNN architecture overview:

-

Two convolutional layers with 32 and 64 filters, each followed by ReLU and max pooling (2\(\times\)2)

-

A flattening layer to convert 2D feature maps into 1D vectors

-

A dense (fully connected) layer with 128 neurons and ReLU activation

-

A dropout layer with a rate of 0.5 to prevent overfitting

-

An output layer with 8 neurons and softmax activation

The model was compiled using the Adam optimizer and trained using categorical cross-entropy as the loss function. Accuracy was used as the primary evaluation metric.

Support vector machine (SVM)

The ensemble model utilizes Support Vector Machines (SVMs) to analyze high-dimensional spectrogram data through a radial basis function (RBF) kernel.

Input Features: The input to the SVM classifier consisted of flattened pixel values from spectrogram images (128 \(\times\) 128 grayscale images, reshaped into a 16,384-dimensional feature vector). No explicit feature extraction was performed before classification, allowing the SVM to learn patterns directly from the raw spectrogram data.

The decision function of the SVM is expressed as:

where:

-

\(\alpha _i\) are the Lagrange multipliers,

-

\(y_i\) are the class labels (\(\in \{-1, 1\}\)),

-

\(x_i\) are the support vectors (training data),

-

\(K(x_i, x)\) is the RBF kernel function56,

-

b is the bias term.

The SVM constructs a hyperplane that maximizes the margin between two classes while allowing for classification errors. The corresponding optimization problem is formulated as follows:

subject to:

where:

-

w is the weight vector defining the hyperplane,

-

b is the bias term,

-

\(x_i\) is the input feature vector,

-

\(y_i\) is the binary class label,

-

\(\xi _i\) are slack variables that allow margin violations,

-

C is the regularization parameter that balances margin maximization and classification error.

Random Forest (RF)

Random Forest (RF) is an ensemble learning technique that integrates predictions from numerous decision trees to obtain conclusive categorization. The ultimate classification was established through a majority vote, with each tree contributing to a prediction.

Input features: Similar to the SVM classifier, the input to the Random Forest model consisted of flattened pixel values from spectrogram images (128 \(\times\) 128 grayscale images reshaped into a 16,384-dimensional feature vector). No explicit feature extraction was performed before classification, allowing the Random Forest model to learn directly from thw raw spectrogram pixel values.

Every decision tree in the Random Forest ensemble (\(T_1, T_2, \dots , T_k\)) is trained on a randomly chosen subset of the dataset. The final classification result was determined by a majority vote from all trees, each offering a class prediction \(T_j(x)\) for input x. A random subset of the data was employed to train each of the 100 decision trees that formed the Random Forest model used in this study. The final classification was determined by the vote of the majority, as follows:

where:

-

\(T_j(x)\) is the class prediction of the j-th decision tree for input x,

-

\(\hat{y}\) is the final predicted class based on majority vote across all k trees.

Alternatively, the probability that instance x belongs to class c can be estimated using vote averaging.

where:

-

\(P(y = c | x)\) is the estimated probability that input x belongs to class c,

-

\(T_j(x)\) is the prediction of the j-th decision tree for input x57,

-

k is the total number of trees in the Random Forest,

-

\(I(\cdot )\) is the indicator function, which equals 1 if \(T_j(x) = c\), and 0 otherwise.

By averaging predictions across several trees, the main benefit of RF is its capacity to lower variance and prevent overfitting.

Feature selection: In this study, no explicit feature selection technique was applied prior to the classification. Instead, the entire spectrogram image (128 \(\times\) 128 grayscale, flattened to 16,384 dimensions) was directly used as the input for the SVM and Random Forest models. The rationale behind this decision was to allow the classifiers to learn from the complete frequency-time representation captured in the spectrograms without discarding potentially informative features. Although dimensionality reduction techniques such as PCA or manual feature selection methods could have been explored, initial experiments showed that the raw pixel-based features yielded high accuracy when processed by the ensemble model. Future work may incorporate feature selection or embedding strategies to reduce computational load and enhance interpretability.

An Ensemble Learning-Based Method for Classifying Biomedical Signals into Eight Anatomical Regions. Percussion and palpation signals are collected at the start of the procedure. After being processed with Short-Time Fourier Transform (STFT) and normalization procedures to produce spectrogram images, these signals are fed into an ensemble of Convolutional Neural Network (CNN), Support Vector Machine (SVM), and Random Forest (RF) classifiers. Predictions are then generated from the ensemble model.

Figure 2 depicts the proposed ensemble learning strategy for classifying biological signals. The process began with the collection of percussion and palpation signals from patients. The signals were investigated using a Short-Time Fourier Transform (STFT), which generates spectrogram images depicting the signals’ time-frequency distributions. The spectrograms were scaled and normalized to ensure consistency throughout the collection period.

The signals are then classified using an ensemble learning model that includes Random Forest (RF), Support Vector Machine (SVM), and Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) classifiers. The ultimate predictions were produced using a soft voting classifier, which integrated the probability outputs from each classifier and averaged them to arrive at a final prediction. This method utilizes the certainty of each model in its predictions, resulting in more reliable and precise classification by combining the advantages of CNN, SVM, and RF. The evaluation of the model involved metrics, including accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score, followed by a thorough review of the findings.

Pseudo-code overview and implementation steps

The main procedures for putting the ensemble learning model used for biomedical signal categorization into practice are described in the pseudocode as follows:

-

Step 1: Dataset Splitting: The dataset was partitioned using subject-wise partitioning to ensure the the model generalized to unseen subjects. This method follows biomedical signal classification standards and is implemented using 5-fold Stratified K-Fold cross-validation. The accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score values reported reflect the mean and standard deviation calculated over the 5-folds.

-

Step 2: Preprocessing: Resize all photos to a consistent 128 \(\times\) 128 pixel scale and then normalize the spectrogram pixel intensities.

-

Step 3: Model Training: Develop three classifiers: a random forest with 100 decision trees, a support vector machine utilizing a Radial Basis Function kernel, and a convolutional neural network for feature extraction.

-

Step 4: Combine Classifiers (Ensemble Method): By merging the predictions of the CNN, SVM, and RF using a voting classifier, the advantages of each model can be leveraged to increase the classification accuracy.

-

Step 5: Hyperparameter Tuning: To discover the optimum model configurations, utilize GridSearchCV to optimize the SVM and Random Forest hyperparameters.

-

Step 6: Performance Evaluation: To evaluate the model’s performance, consider the accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score. Create receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves for additional analyses.

-

Step 7: Output: Generate and show the ROC curves and classification results to understand the model’s effectiveness and potential flaws.

Listing 1. Pseudo-code for biomedical signal classification ensemble learning model.

Hyperparameter tuning and model training

The CNN, SVM, and RF models were trained and evaluated using a subject-wise 70%-30% partitioning strategy, ensuring that test the subjects were excluded from the training phase. Hyperparameter tuning for SVM and RF was performed using GridSearchCV, optimizing classification performance based on accuracy, precision, recall, and an F1-score58. The CNN model’s hyperparameters were manually modified using empirical tuning to achieve convergence and generalization. Justification for GridSearchCV: Although advanced tuning techniques such as Bayesian Optimization, Optuna, or RandomizedSearchCV can offer computational efficiency, GridSearchCV was selected in this study for its exhaustive and reproducible nature. Given that the hyperparameter space for both SVM (C, gamma) and RF (n_estimators, max_depth) was relatively small and well-defined, GridSearchCV ensured a complete evaluation of all parameter combinations, guaranteeing that no potentially optimal pair was missed. Furthermore, its integration with Stratified K-Fold cross-validation improves reliability, which is essential for medical diagnostics. Future work may explore adaptive and Bayesian optimization methods to further enhance the tuning efficiency.

CNN training

An Adam optimizer with a categorical cross-entropy loss function is used to train the CNN model. For the model to successfully learn the spectrogram features, the training process proceeded for 10 epochs with a batch size of 32. A comprehensive summary of the design is presented in section “Model architecture”.

SVM hyperparameters

The following is how the SVM’s hyperparameters were optimized:

-

Regularization parameter: \(C = 1.0\)

-

RBF kernel parameter: \(\gamma = 0.01\)

A variety of C values from 0.1 to 100 and \(\gamma\) values from 0.01 to 1.0 were investigated by GridSearchCV. \(C = 1.0\) and \(\gamma = 0.01\) were shown to be the ideal configurations, offering balanced regularization.

RF hyperparameters

For the Random Forest model, the following parameters were optimized:

-

Number of trees: 100

-

Maximum depth: 10

GridSearchCV tested maximum depths from 10 to infinity and n_estimators from 50 to 200. The optimal setup balanced the model complexity with overfitting prevention by using 100 trees with a maximum depth of 1059.

Evaluation metrics

To evaluate the ensemble model, the following performance metrics were applied:

-

Accuracy:

$$\begin{aligned} \text {Accuracy} = \frac{TP + TN}{TP + TN + FP + FN} \end{aligned}$$(12) -

Precision:

$$\begin{aligned} \text {Precision} = \frac{TP}{TP + FP} \end{aligned}$$(13) -

Recall:

$$\begin{aligned} \text {Recall} = \frac{TP}{TP + FN} \end{aligned}$$(14) -

F1-Score:

$$\begin{aligned} F1 = 2 \times \frac{\text {Precision} \times \text {Recall}}{\text {Precision} + \text {Recall}} \end{aligned}$$(15)

Recall is crucial for minimizing missed diagnoses (false negatives), whereas precision is vital in medical diagnostics to decrease false positives and prevent unnecessary treatment. The F1-score is valuable in contexts where both accuracy and memory errors have significant clinical implications, as they provide a balanced evaluation of both factors. In the context of unbalanced biomedical datasets, these measures are critical for evaluating model performance60.

Experimental setup and environment

The system used for the experiments has the following characteristics:

-

CPU/Processor: Intel CPU Core i9-13900K

-

GPU: NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3060

-

RAM: 128GB

-

Software: Python 3.8, scikit-learn, TensorFlow, and Matplotlib

Using both the CPU and GPU capabilities, this configuration offers sufficient computing power for effective model training and evaluation.

Validation strategy

A 5-fold cross-validation technique was used throughout the model construction phase to ensure reliable and unbiased performance evaluation. In this strategy, the dataset is divided into five equal-sized folds, four for training and one for testing in each iteration. This technique was repeated five times to ensure that each sample was used for training and validation just once. To demonstrate the model’s consistency, the final results are shown as the average performance across all folds, including the standard deviation.

For hyperparameter tuning of the Support Vector Machine (SVM) and Random Forest (RF) models, GridSearchCV from the scikit-learn library was used. This method internally applies Stratified K-Fold cross-validation, which maintains the class distribution across folds, making it particularly suitable for multi-class biomedical signal datasets. The generalization capability of the mdoel was reliably assessed by preserving the proportion of each anatomical region in every fold (Table 3).

Train-test ratio and justification

To ensure model stability while maintaining generalizability, the primary experiments used a 70:30 train-test split. This ratio strikes a balance between sufficient training data for model learning and adequate test data for a thorough evaluation. Experiments were also conducted with 80:20 and 90:10 train test splits to evaluate the model’s consistency across diverse data divisions. The results for each configuration are listed in Table 4. Across all splits, the ensemble model maintained high performance, demonstrating its robustness to data size variation.

Mathematical justification of STFT and signal analysis

This study used the Short-Time Fourier Transform (STFT) to convert non-stationary biological data to time-frequency representations. The Short-Time Fourier Transform (STFT) allows for the discovery of transient features that are not discernible in the time domain. The STFT’s window function w(t) efficiently balances frequency resolution and temporal precision, allowing reliable detection of the signal’s numerous frequency components.

The RBF kernel of the SVM model is perfect for identifying intricate patterns because spectrogram data are high-dimensional. The Random Forest (RF) classifier further improves the decision boundary created by the SVM by lowering the variance through ensemble averaging. By gleaning complex spatial patterns from spectrograms, CNNs enhance analysis and provide model rich feature representations.

Results

Model performance

Spectrogram images from biological data, specifically palpation and percussion, were utilized to assess the efficacy of ensemble learning models including Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN), Support Vector Machines (SVM), and Random Forest. This analysis focuses on four critical performance metrics: accuracy, precision, recall, and the F1-score.

The ensemble model (CNN + SVM + RF) demonstrated superior classification performance, surpassing that of individual classifiers, with an accuracy of 95.4%. Table 5 displays the classification accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score for all the models across the eight anatomical regions.

Spectrogram analysis for biomedical signal classification

The results demonstrated that an ensemble learning architecture combining CNN, SVM, and Random Forest models can effectively classify biological signal spectrograms. The ensemble model’s robust preprocessing and training methods, which generate a high level of classification accuracy across eight anatomical regions, indicate that it is a promising candidate for real-time clinical application. Performance evaluation was conducted per region, ensuring that the classification of each anatomical location was validated separately. Figure 3 shows an example of a spectrogram generated from the biological signal data, highlighting the unique frequency patterns used by the classifiers.

Short-Time Fourier Transform (STFT) was employed to generate spectrograms, transforming biological signals into the frequency domain to capture their temporal and spectral characteristics for precise categorization5,6. This transformation allows models to extract features that distinguish minute variations in signal classes, such as those induced by percussion and palpation. To solve the challenges of analyzing such data, an ensemble learning system integrating Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN), Random Forest (RF), and Support Vector Machines (SVM) classifiers was built. The utilization of this hybrid approach improves the categorization of biological signals into separate anatomical regions, which in turn enables diagnostic conclusions that are clinically meaningful.

Figure 4 depicts a spectrogram of a biological signal, illustrating the temporal-spectral information obtained by STFT. Plotting the frequency components across time reveals important features that can help classification models differentiate between various classes. Changes in amplitude disclose these subtleties, emphasizing the usefulness of time-frequency representations such as spectrograms, in identifying patterns of clinical significance that conventional time-domain analysis may overlook63,64. The ability to visualize frequency patterns over time enables the ensemble model to distinguish key diagnostic features effectively.

Performance analysis of the ensemble model

The precision, recall, and F1-score metrics were used to test the classification performance of the ensemble model across all eight anatomical regions. In addition, Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curves were created to assess the model’s discriminatory performance across classes.

Figure 5 shows the precision, recall, and F1-scores for each identified region. The high precision and recall scores proved the model’s ability to reliably detect relevant signal patterns. Minor variations in recall across regions indicate potential areas for improvement, including enhanced feature extraction techniques and data augmentation strategies65,66.

Figure 6 depicts the ROC curves, which highlight the trade-off between false-positive and true-positive rates at different categorization levels. The ensemble model’s remarkable discriminatory ability is supported by its high area under the curve (AUC) values, which approach 1.0 in most classes (Fig. 7).

Qualitative interpretation of classification results

In addition to quantitative metrics, qualitative analysis was conducted to better understand the model behavior and its diagnostic implications. Examination of spectrograms from different anatomical regions revealed distinct frequency patterns, particularly in percussion signals from the posterior and lateral regions, which were consistently classified with high confidence. Conversely, signals from places with similar auditory features, such as the anterior and epigastric areas, had slightly lower recall, indicating difficulties discriminating between them. This shows that spectrogram variability is important for classification performance and could benefit from improved spatial filtering or domain-specific augmentation.

Moreover, misclassification was predominantly observed between anatomically adjacent regions, highlighting the importance of signal boundary clarity in data acquisition. By inspecting the ROC curves and confusion matrices, it was found that the confidence scores of the ensemble model aligned well with clinical expectations, reinforcing its applicability in real-world diagnostic settings. These observations support the interpretability of the model and suggest that integrating explainable AI techniques in future studies could further enhance clinical adoption.

Mathematical explanation

To optimize the classification performance, the SVM and Random Forest models were fine-tuned using GridSearchCV. The mathematical formulation of the SVM classifier is given by.

where:

-

w represents the weight vector,

-

C denotes the regularization parameter,

-

\(y_i\) is the true class label,

-

\(x_i\) is the feature vector,

-

b is the bias term67.

Similarly, the prediction function of the Random Forest classifier is represented as:

where:

-

T is the total number of decision trees,

-

\(h_t(x)\) is the prediction made by the t-th tree68.

The ensemble model successfully balanced the contributions of CNN, SVM, and RF, achieving a classification accuracy of 95.4%, positioning it as an effective approach for biomedical signal classification.

Discussion

The ensemble model improved classification accuracy significantly by combining Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN), Support Vector Machines (SVM), and Random Forest (RF). This combination effectively uses each classifier’s distinct strengths: CNN obtains spatial characteristics from spectrograms, SVM accurately classifies high-dimensional data, and RF reduces overfitting via ensemble averaging. The complementary nature of these methods ensures robust performance in biomedical signal classification, particularly in distinguishing spectrogram-based signals from different anatomical regions.

Performance evaluation and clinical relevance

According to Table 5, the ensemble model obtained a classification accuracy of 95.4%, outperforming individual classifiers in precision (0.95), recall (0.95), and F1-score (0.95). The enhanced performance is due to the ensemble’s capacity to manage bias-variance trade-offs effectively, optimizing feature extraction and decision boundaries61,62. Unlike conventional single label classifiers, which often suffer from high variance or bias, the ensemble model achieves a well-generalized decision function by integrating multiple learning approaches.

From a clinical perspective, the accurate classification of biomedical signals is crucial for reducing misdiagnoses and improving patient outcomes. Traditional methods of diagnosing conditions based on palpation and percussion signals are highly subjective and rely on physician expertise and experience. The ensemble learning framework introduces an objective and reproducible approach that enhances the diagnostic precision and standardization across different medical practitioners. By effectively distinguishing between anatomical regions using spectrogram-derived biomedical signals, the model has the potential to improve remote diagnostics in telemedicine settings, where real-time classification can aid in clinical decision-making.

Furthermore, using a Short-Time Fourier Transform (STFT) in signal processing ensures the retention of both temporal and spectral properties, boosting the model’s interpretability. This is particularly important for differentiating signals that exhibit subtle variations across regions, which is a challenge for clinical diagnostics69. Consequently, the model’s output can be integrated into computer-aided diagnostic (CAD) systems, allowing healthcare providers to leverage automated classification for faster and more consistent diagnoses. The high classification accuracy of the ensemble framework also suggests that this method could be extended to other biomedical applications, such as cardiovascular or respiratory signal analysis, further strengthening its utility in non-invasive diagnostics.

The ensemble model’s better performance (95.4%) proved the efficiency of combining feature extraction (CNN), non-linear decision boundaries (SVM), and ensemble averaging (RF). Notably, the performance remained consistent even in difficult regions such as the epigastric and lateral zones, as evidenced by the ROC curves and qualitative analysis. This stability across physically different inputs verifies the model’s generalizability in real clinical scenarios.

Comparison with existing models

For additional validation of the ensemble model, a comparison of its performance with established biomedical signal classification methods is presented in Table 6. The ensemble model demonstrates superior performance, achieving an accuracy of 95.4%, surpassing models that utilize CNN exclusively, LSTM networks, and earlier ensemble methods70,71,72,73.

The table indicates that earlier models exhibited challenges related to overfitting, constrained generalization, or inadequate feature extraction. CNN-based models typically do not effectively capture the temporal dependencies in signals. By contrast, RNN-based models require substantial datasets to achieve optimal performance. The ensemble model effectively balances generalization and feature extraction, resulting in state-of-the-art performance.

Computational complexity analysis

The computational complexity of the proposed ensemble model depended on the individual complexities of the CNN, SVM, and Random Forest classifiers. Each contributes differently based on the data dimensionality and training strategy:

CNN: The dominant operations in a CNN involve convolution and pooling layers. The temporal complexity of an input image of size \(n \times n\) with filter size \(f \times f\), k filters, and d layers is roughly.

This is manageable because of the limited spectrogram size (128 \(\times\) 128) and shallow architecture (2 convolutional layers), optimized further with GPU acceleration.

SVM: For n training samples with d-dimensional features, the training time complexity of the kernel-based SVM is between:

Given that we used a moderate training size and linear/RBF kernel, training remains feasible and efficient for 8-class classification:

Random Forest: The time complexity for Random Forest is.

where T is the number of trees, and n is the number of data points. With 100 trees and flattened spectrogram input, the training and prediction phases are fast owing to RF’s parallelisable structure of the RF.

Ensemble Overhead: The soft voting mechanism used for combining predictions adds minimal overhead because it only aggregates class probabilities from the three models.

Overall, the ensemble model balanced accuracy and computational efficiency. The training duration was less than 30 min on an RTX 3060 GPU with 128GB of RAM. The inference time per sample is less than 0.01 seconds, indicating applicability for near-real-time diagnostic applications.

Challenges and limitations

The ensemble learning approach exhibits significant classification accuracy; however, several challenges persist. A significant constraint is the computational expense associated with ensemble learning methodologies. Training the three classifiers (CNN, SVM, and RF) requires more computational resources than standalone deep learning models. However, this can be mitigated using efficient model pruning or knowledge distillation, in which a smaller student model inherits the performance of the ensemble while reducing the inference time.

Another limitation is the generalization of unseen patient data. Although the model achieves high accuracy on the current dataset, real-world biomedical signal variations, such as noise artifacts, device discrepancies, and inter-patient variability, may impact the performance. Domain adaptation techniques or transfer learning approaches can address this issue by fine-tuning the model for different patient groups or sensor types.

In addition, while the model currently classifies signals into eight anatomical regions, certain medical conditions may require finer granularity in classification, distinguishing between more localized sub-regions. Hierarchical classification frameworks should be explored to further refine the classification process and enhance its applicability in clinical practice.

Future directions

Given the promising results of this study, several avenues for future research should be pursued.

-

1.

Integration with real-time systems – Deploying the model in edge computing or cloud-based platforms to enable real-time biomedical signal classification in clinical environments.

-

2.

Transfer learning for generalization – Pre-trained deep learning models are used to enhance generalization to unseen patient datasets.

-

3.

Multi-Modal Data Fusion – Combining spectrogram-based classification with additional physiological data, such as electromyography (EMG) or electrocardiography (ECG) for a comprehensive diagnostic tool.

-

4.

Explainability and Interpretability – Developing explainable AI (XAI) techniques to make the model’s decisions more interpretable for medical professionals, ensuring trust and regulatory approval.

-

5.

Adaptive Ensemble Learning – Introducing dynamically weighted ensemble approaches where model contributions are adjusted based on input complexity or uncertainty.

-

6.

Federated Learning for Privacy-Preserving Models – Implementing decentralized learning techniques to train models across multiple institutions while preserving patient data privacy.

The results confirmed that ensemble learning offers a more robust and reliable approach for biomedical signal classification, particularly when dealing with spectrogram-based medical diagnostics. With further refinement, this model can serve as a foundation for intelligent diagnostic tools in clinical and telemedicine applications. Furthermore, expanding the dataset to include a broader range of patient samples and recording circumstances may improve the robustness and application of ensemble classification frameworks. Addressing these future directions may have a substantial impact on the advancement of AI-driven diagnostic frameworks in healthcare.

Conclusion and future work

Conclusion

This study introduced an ensemble learning framework for the categorization of spectrogram pictures produced from biological signals, specifically percussion and palpation, by combining Support Vector Machines (SVM), Random Forest (RF), and Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN). The framework uses CNNs for feature extraction, SVMs for high-dimensional data handling, and RFs to mitigate noise and overfitting. The model attained a classification accuracy of 95.4% across eight anatomical regions, outperforming individual classifiers and previous ensemble techniques.

The demonstrated success of this approach highlights its potential to advance non invasive diagnostic methods, especially in clinical settings. The model exhibits strong classification capabilities by converting time-domain biological signals into time-frequency representations through the application of a Short-Time Fourier Transform (STFT). This methodology provides a reliable basis for objective data-driven diagnostics that can optimize healthcare delivery. In scenarios where subjective diagnostic methods, such as auscultation and palpation, introduce variability, this ensemble model offers significant advantages by reducing diagnostic errors and increasing accuracy. Furthermore, the model’s potential scalability makes it a useful tool for telemedicine applications and resource-constrained situations, allowing equal access to high-quality diagnostic capabilities. This study emphasizes the growing necessity of incorporating AI-powered technologies into modern healthcare, paving the way for advanced solutions to supplement the traditional diagnostic procedures.

The ensemble model achieved a high classification accuracy of 95.4%, significantly outperforming the individual classifiers. Through robust performance on both quantitative (F1-score, ROC) and qualitative (region-specific signal patterns) evaluations, the model established itself as a promising tool for clinical diagnostics. Incorporating advanced interpretability and broader validation datasets in future studies can further elevate its clinical applicability.

Future work

Even with promising results, several areas warrant further exploration and refinement:

-

1.

Integration with Advanced Deep Learning Models: The ability of the model to discover subtle patterns in biological data can be improved by using advanced designs such as Enhanced Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) and Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs). Applying these approaches to larger and more varied datasets may improve classification and generalization accuracy.

-

2.

Real-Time Clinical Implementation and Scalability: Although the model demonstrated significant accuracy, its computational complexity may hinder real-time clinical applications. Further research should concentrate on the optimization of the model for real-time implementation using hardware accelerators (e.g., GPUs) or the compression of model architectures. In addition, its applicability can be broadened by evaluating its efficacy in resource-constrained settings and telemedicine.

-

3.

Multimodal Data Integration: The diagnostic precision of the model could be further improved by incorporating additional data modalities, such as patient demographics and imaging data (e.g., MRI and ultrasound). The integration of multimodal data can enhance predictive outcomes and facilitate deeper comprehension of patient health.

-

4.

Model Explainability and Trust: Enhancing the model’s transparency is critical for increasing physician trust in an AI-driven diagnosis. Explainable AI tools, such as Shapley Additive Explanations (SHAP) and Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations (LIME), should be implemented in clinical practice to promote the employment of more interpretable decision-making procedures.

Final remarks

The potential of the proposed ensemble learning framework, which integrates CNN, RF, and SVM, as a non-invasive diagnostic instrument that can manage high-dimensional and noisy data, is demonstrated. This research establishes a foundation for AI-based systems that are both scalable and resilient, capable of improving diagnostic accuracy and adapting to a variety of healthcare contexts, such as resource-limited environments and telemedicine. However, real-time clinical deployment and computational efficiency remain the key challenges. Addressing these issues through model optimization, advanced deep learning integration, and explainability will ensure safe and effective adoption of AI-driven diagnostics. Future advancements in these areas can substantially improve patient outcomes, fostering the broader adoption of AI-powered systems in modern healthcare.

Data availibility

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available owing to privacy and ethical concerns. The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, Ic. J., upon reasonable request. Requests to access the datasets were directed to Incheol Jeong at incheol1231@gmail.com.

Abbreviations

- CNN:

-

Convolutional Neural Network

- SVM:

-

Support Vector Machine

- RF:

-

Random Forest

- STFT:

-

Short-Time Fourier Transform

- ROC:

-

Receiver Operating Characteristic

- AUC:

-

Area Under the Curve

- CAD:

-

Computer-Aided Diagnosis

- RBF:

-

Radial Basis Function

- ReLU:

-

Rectified Linear Unit

References

Kligfield, P. et al. Recommendations for the standardization and interpretation of the electrocardiogram: part I: the electrocardiogram and its technology: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Electrocardiography and Arrhythmias Committee, Council on Clinical Cardiology; the American College of Cardiology Foundation; and the Heart Rhythm Society. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 49, 1109–1127 (2007).

Clifford, G. D. et al. Classification of normal/abnormal heart sound recordings: the PhysioNet/Computing in Cardiology Challenge 2016. J. Med. Internet Res. 19, e75 (2017).

He, K., Zhang, X., Ren, S. & Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) 770–778 (2016).

Bengio, Y., Courville, A. & Vincent, P. Representation learning: a review and new perspectives. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 35, 1798–1828 (2013).

Boashash, B. Time-Frequency Signal Analysis and Processing: A Comprehensive Reference (Elsevier, 2015).

Cohen, L. Time-Frequency Analysis (Prentice Hall, 1995).

Krizhevsky, A., Sutskever, I. & Hinton, G.E. ImageNet classification with deep convolutional neural networks. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 1097–1105 (2012).

Simonyan, K. & Zisserman, A. Very deep convolutional networks for large-scale image recognition. arXiv preprint arXiv:1409.1556 (2014).

Breiman, L. Random forests. Mach. Learn. 45, 5–32 (2001).

Cortes, C. & Vapnik, V. Support-vector networks. Mach. Learn. 20, 273–297 (1995).

Hinton, G. et al. Deep neural networks for acoustic modeling in speech recognition: the shared views of four research groups. IEEE Signal Process. Mag. 29, 82–97 (2012).

LeCun, Y., Bengio, Y. & Hinton, G. Deep learning. Nature 521, 436–444 (2015).

Goodfellow, I., Bengio, Y. & Courville, A. Deep Learning (MIT Press, 2016).

Huang, D.-M. et al. Deep learning-based lung sound analysis for intelligent stethoscope. Mil. Med. Res. 10, 44 (2023).

Landge, K., Kidambi, B. R., Singhal, A. & Basha, A. Electronic stethoscopes: brief review of clinical utility, evidence, and future implications. J. Pract. Cardiovasc. Sci. 4, 65 (2018).

Palaniappan, R., Sundaraj, K. & Sundaraj, S. A comparative study of the SVM and k-NN machine learning algorithms for the diagnosis of respiratory pathologies using pulmonary acoustic signals. BMC Bioinform. 15, 223 (2014).

Sakai, T., Kato, M., Miyahara, S. & Kiyasu, S. Robust detection of adventitious lung sounds in electronic auscultation signals. In Proceedings of the 21st International Conference on Pattern Recognition (ICPR2012). Tsukuba, Japan 1993–6 (2012).

Oweis, R. J., Abdulhay, E. W., Khayal, A. & Awad, A. An alternative respiratory sounds classification system utilizing artificial neural networks. Biomed. J. 38, 152–161 (2015).

Huang, D., Wang, L. & Wang, W. A multi-center clinical trial for wireless stethoscope-based diagnosis and prognosis of children community-acquired pneumonia. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 70, 2215–2226 (2023).

Emmanouilidou, D., McCollum, E. D., Park, D. E. & Elhilali, M. Adaptive noise suppression of pediatric lung auscultations with real applications to noisy clinical settings in developing countries. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 62, 2279–2288 (2015).

Mills, G. A., Nketia, T. A., Oppong, I. A. & Kaufmann, E. E. Wireless digital stethoscope using Bluetooth technology. Int. J. Eng. Sci. Technol. 4, 3961–3969 (2012).

Demir, F., Sengür, A., Bajaj, V. & Polat, K. Towards the classification of heart sounds based on convolutional deep neural network. Health Inf. Sci. Syst. 7, 1–9 (2019).

Leng, S. et al. The electronic stethoscope. Biomed. Eng. Online 14, 66 (2015).

Lee, S. H. et al. Fully portable continuous real-time auscultation with a soft wearable stethoscope designed for automated disease diagnosis. Sci. Adv. 8, eabo5867 (2022).

Hirosawa, T. et al. The utility of real-time remote auscultation using a Bluetooth-connected electronic stethoscope: open-label randomized controlled pilot trial. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 9, e23109 (2021).

Yilmaz, G. et al. A wearable stethoscope for long-term ambulatory respiratory health monitoring. Sens. (Basel) 20, 5124 (2020).

İçer, S. & Gengeç, Ş. Classification and analysis of non-stationary characteristics of crackle and rhonchus lung adventitious sounds. Digit. Signal Process. 28, 18–27 (2014).

Palaniappan, R., Sundaraj, K. & Ahamed, N. U. Machine learning in lung sound analysis: a systematic review. Biocybern. Biomed. Eng. 33, 129–135 (2013).

Sen, I., Saraclar, M. & Kahya, Y. P. A comparison of SVM and GMM-based classifier configurations for diagnostic classification of pulmonary sounds. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 62, 1768–1776 (2015).

Zhang, J. et al. Real-world verification of artificial intelligence algorithm-assisted auscultation of breath sounds in children. Front. Pediatr. 9, 627337 (2021).

Acharya, J. & Basu, A. Deep neural network for respiratory sound classification in wearable devices enabled by patient-specific model tuning. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Circuits Syst. 14, 535–543 (2020).

Nguyen, T. & Pernkopf, F. Lung sound classification using co-tuning and stochastic normalization. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 69, 2872–2882 (2022).

Pham, L., McLoughlin, I., Phan, H., Tran, M. & Nguyen, T. Robust deep learning framework for predicting respiratory anomalies and diseases. In Proceedings of the 2020 42nd Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine & Biology Society (EMBC). Montreal, QC, Canada 164–167 (2020).

Perna, D. & Tagarelli, A. Deep auscultation: Predicting respiratory anomalies and diseases via recurrent neural networks. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE 32nd International Symposium on Computer-Based Medical Systems (CBMS). Cordoba, Spain 50–55 (2019).

Altan, G., Kutlu, Y., Pekmezci, A. Ö. & Nural, S. Deep learning with 3D-second order difference plot on respiratory sounds. Biomed. Signal Process. Control. 45, 58–69 (2018).

Pramono, R. X. A., Bowyer, S. & Rodriguez-Villegas, E. Automatic adventitious respiratory sound analysis: a systematic review. PLoS One 12, e0177926 (2017).

Palaniappan, R., Sundaraj, K., Ahamed, N. U., Arjunan, A. & Sundaraj, S. Computer-based respiratory sound analysis: a systematic review. IETE Tech Rev. 30, 248–256 (2013).

Jácome, C. & Marques, A. Computerized respiratory sounds in patients with COPD: a systematic review. J. Chronic Obstr. Pulm. Dis. 12, 104–112 (2015).

Bardou, D., Zhang, K. & Ahmad, S. M. Lung sounds classification using convolutional neural networks. Artif. Intell. Med. 88, 58–69 (2018).

Pasterkamp, H., Kraman, S. S. & Wodicka, G. R. Respiratory sounds: advances beyond the stethoscope. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 156, 974–987 (1997).

Bohadana, A., Izbicki, G. & Kraman, S. S. Fundamentals of lung auscultation. N. Engl. J. Med. 370, 744–751 (2014).

Olson, D. E. & Hammersley, J. R. Mechanisms of lung sound generation. Semin. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 6, 171–179 (1985).

Sarkar, M., Madabhavi, I., Niranjan, N. & Dogra, M. Auscultation of the respiratory system. Ann. Thorac. Med. 10, 158–167 (2015).

Gavriely, N., Palti, Y. & Alroy, G. Spectral characteristics of normal breath sounds. J. Appl. Physiol. 50, 307–314 (1981).

Weiss, E. B. & Carlson, C. J. Recording of breath sounds. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 105, 835–839 (1972).

Gavriely, N., Nissan, M., Rubin, A. H. & Cugell, D. W. Spectral characteristics of chest wall breath sounds in normal subjects. Thorax 50, 1292–1300 (1995).

Vyshedskiy, A. et al. Mechanism of inspiratory and expiratory crackles. Chest 135, 156–164 (2009).

Flietstra, B., Markuzon, N., Vyshedskiy, A. & Murphy, R. Automated analysis of crackles in patients with interstitial pulmonary fibrosis. Pulm. Med. 2011, 590506 (2011).

Munakata, M. et al. Spectral and waveform characteristics of fine and coarse crackles. Thorax 46, 651–657 (1991).

Forgacs, P. The functional basis of pulmonary sounds. Chest 73, 399–405 (1978).

Karthick, P. A., Ghosh, D. M. & Ramakrishnan, S. Surface electromyography-based muscle fatigue detection using high-resolution time-frequency methods and machine learning algorithms. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 71, 103275 (2017).

Merletti, R., Parker, P. A. Electromyography: Physiology, Engineering, and Non-Invasive Applications (Wiley, 2004).

Cifrek, M., Medved, V., Tonkovic, S. & Ostojic, S. Surface EMG-based muscle fatigue evaluation in biomechanics. Clin. Biomech. 24, 327–340 (2009).

Zwarts, M. J., Bleijenberg, G. & van Engelen, M. Clinical neurophysiology of fatigue. Clin. Neurophysiol. 119, 2–10 (2008).

Singh, V. P., Kumar, D. K., Polus, B. & Fraser, S. Strategies to identify changes in SEMG due to muscle fatigue during cycling. J. Med. Eng. Technol. 31, 144–151 (2007).

Zhang, J., Lockhart, T. E. & Soangra, R. Classifying lower extremity muscle fatigue during walking using machine learning and inertial sensors. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 42, 600–612 (2014).

Al-Mulla, M. R., Sepulveda, F. & Colley, M. A review of non-invasive techniques to detect and predict localized muscle fatigue. Sensors 11, 3545–3594 (2011).

Dimitrova, N. A., Arabadzhiev, T. I., Hogrel, J. Y. & Dimitrov, G. V. Fatigue analysis of interference EMG signals obtained from biceps brachii during isometric voluntary contraction at various force levels. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. 19, 252–258 (2009).

Bonato, P., Roy, S. H., Knaflitz, M. & De Luca, C. J. Time-frequency parameters of the surface myoelectric signal for assessing muscle fatigue during cyclic dynamic contractions. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 48, 745–753 (2001).

Rogers, D. R. & MacIsaac, D. T. EMG-based muscle fatigue assessment during dynamic contractions using principal component analysis. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. 21, 811–818 (2011).

Assous, S. & Boashash, B. Evaluation of the modified S-transform for time-frequency synchrony analysis and source localisation. J. Adv. Signal Process. 1, 1–18 (2012).

Stockwell, R. G., Mansinha, L. & Lowe, R. P. Localization of the complex spectrum: the S transform. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 44(4), 998–1001 (1996).

Yan, A. et al. Automatic seizure detection using Stockwell transform and boosting algorithm for long-term EEG. Epilepsy Behav. 45, 8–14 (2015).

Ortigosa, N., Fernández, C., Galbis, A. & Cano, Ó. Phase information of time-frequency transforms as a key feature for classification of atrial fibrillation episodes. Physiol. Meas. 36(4), 409–424 (2015).

Boashash, B. Time Frequency Signal Analysis and Processing: A Comprehensive Reference (Elsevier, 2003).

Knaflitz, M. & Molinari, F. Assessment of muscle fatigue during biking. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng 11(1), 17–23 (2003).

Gonzalez-Izal, M. et al. EMG spectral indices and muscle power fatigue during dynamic contractions. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. 20(2), 233–240 (2010).

Boashash, B., Azemi, G. & O’Toole, J. Time-frequency processing of nonstationary signals: advanced TFD design to aid diagnosis with highlights from medical applications. IEEE Signal Process. Mag. 2013, 108–119 (2013).

Karthick, P. A. & Ramakrishnan, S. Surface electromyography based muscle fatigue progression analysis using modified B distribution time–frequency features. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 26, 42–51 (2016).

Hsu, F. S. et al. Benchmarking of eight recurrent neural network variants for breath phase and adventitious sound detection on a self-developed open-access lung sound database-HF_Lung_V1. PLoS One 16, e0254134 (2021).

Rocha, B. M. et al. An open access database for the evaluation of respiratory sound classification algorithms. Physiol. Meas. 40, 035001 (2019).

Kim, Y. et al. Respiratory sound classification for crackles, wheezes, and rhonchi in the clinical field using deep learning. Sci. Rep. 11, 17186 (2021).

Ryu, S. et al. iApp: an autonomous inspection, auscultation, percussion, and palpation platform. Front. Physiol. 13, 825612 (2023).

Sharma, A. et al. A systematic review on machine learning intelligent systems for heart disease diagnosis. Arch. Comput. Methods Eng. 2025, 1–27 (2025).

Dhanka, S. & Maini, S. HyOPTXGBoost and HyOPTRF: hybridized intelligent systems using Optuna optimization framework for heart disease prediction with clinical interpretations. Multimedia Tools Appl. 83, 72889–72937 (2024).

Dhanka, S., Bhardwaj, V. K. & Maini, S. Comprehensive analysis of supervised algorithms for coronary artery heart disease detection. Expert Syst. 40(7), e13300 (2023).

Viji, D., Dhanka, S., Binda, M. B. & Thomas, M. Hybrid STO-IWGAN method based energy optimization in fuel cell electric vehicles. Energy Convers. Manage. 305, 118249 (2024).

Dhanka, S. & Maini, S. A hybridization of XGBoost machine learning model by Optuna hyperparameter tuning suite for cardiovascular disease classification with significant effect of outliers and heterogeneous training datasets. Int. J. Cardiol 420, 132757 (2025).

Funding

This research was supported by Hallym University Research Fund, 2022(HRF-202205-003).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.K. (First Author) conceived the idea, developed the methodology, and performed formal analysis. S.R. contributed to data curation and experiments and provided valuable input during the formal analysis. Ic. J. (Corresponding Author) supervised the study and reviewed and edited the manuscript. A.K. and S.R. wrote the initial manuscript draft, while Ic. J. provided critical revisions. All authors have reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics statement

Studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Hallym University Institutional Review Board (IRB). All participants provided written informed consent to participate in this study. For further information regarding ethical approval, please contact Hallym University IRB. All methods were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations, as required by the Hallym University Institutional Review Board (IRB) and in compliance with international ethical standards.

Ethical considerations