Abstract

Persian cumin (Bunium persicum) is a widely used plant in Iranian cuisine, valued for its aromatic and therapeutic compounds, primarily monoterpenoids such as γ-terpinene, cuminaldehyde, and p-cymene. Many ambiguities surround the exact process by which monoterpenoids are synthesized in plants. This study investigates the key genes and biosynthetic pathways involved in monoterpenoid production during fruit development. To achieve this, RNA sequencing and GC-MS analysis were performed on two tissues (inflorescence and stem) to identify differentially expressed genes associated with volatile compound biosynthesis. Our findings revealed four highly expressed genes, terpinene synthetase (TPS1, and TPS2), and two geraniol hydroxylases—correlated with γ-terpinene and cuminaldehyde production. We also propose that cuminaldehyde biosynthesis from p-cymene likely involves two hydroxylation steps mediated by cytochrome P450 enzymes (CYP76B) family genes. Additionally, we identified other candidate genes, including those from the P450 family, alcohol dehydrogenases, and hydroxylases, that may contribute to the pathway of cuminaldehyde biosynthesis. Ultimately, this study presents a comprehensive analysis of Bunium persicum’s transcriptome and proposes potential key genes involved in the biosynthesis of cuminaldehyde and γ-terpinene.

Similar content being viewed by others

Bunium persicum (Boiss.) B. Fedtsch. is a perennial medicinal plant of the Apiaceae family with 14 diploid somatic chromosomes (2n = 14). Although it shares the same chromosome number with Cuminum cyminum L. (cumin), it belongs to a different genus and exhibits distinct genetic and biochemical characteristics. In contrast, Carum carvi L. (caraway), another species with a comparable essential oil composition, has 2n = 20 chromosomes, highlighting its greater genetic divergence from B. persicum1. Various names have been given to this species, including black cumin, black caraway, Persian cumin, kalazira, and wild cumin2. It is typically found in temperate to arid climates and mountainous regions. The plant grows to a height of 40–80 cm, has small leaves, and produces umbrella-shaped flowers with white florets in the third year after fruit planting. It generally matures within three months in both vegetative growth and fruit production3. Due to limited knowledge regarding its domestication and commercial cultivation, along with high market demand and uncontrolled wild harvesting, this species faces the risk of extinction4. Given the frequent confusion between this plant and other species, we provide an illustrative photograph of the entire plant and its fruits in Fig. 1 to aid in accurate identification.

Iranians, Indians, and other cultures have long incorporated the fruits of this plant into their diet due to its aromatic scent and medicinal properties. In addition to dietary use, the fruits are also essential in the food industry5. Studies have shown that black cumin fruits exhibit various medicinal properties, including antidiarrheal, anticancer, and antimicrobial effects6,7,8. Furthermore, black cumin fruits are widely reported to contain a diverse range of phytochemicals, particularly monoterpenoids4,5.

Plants produce a highly diverse array of monoterpenes, with over 1000 structurally distinct compounds identified so far. This diversity is evident in species from the Apiaceae family, such as Foeniculum vulgare Mill. (fennel), as well as other aromatic plants like Mentha spicata L. (spearmint), Bunium persicum (Persian cumin), and Thymus vulgaris L. (thyme), which synthesize various volatile compounds contributing to their characteristic aromas. Final stages of monoterpene production pathways are still unclear and poorly defined. It has been suggested that the production of monoterpenes is divided into four stages, the first and second stages producing the geranyl pyrophosphate (GPP, which is a precursor agent for terpenoid production) through both mitochondrial and cytoplasmic pathways9,10. The cytoplasmic The mevalonate (MEV) pathway exhibits greater activity in the production of sesquiterpenes, alkanes, and triterpenes, whereas the plastidial methylerythritol phosphate (MEP) pathway is responsible for synthesizing monoterpenes, diterpenes, and tetraterpenes11. Stage three monoterpenoids producing involves the production of intermediate agents of monoterpenoids, which are produced by terpene synthase (TPSs) and CYP family proteins12. The enzymes required for this stage have been identified to some extent13,14,15. In the final step, as a result of oxidase and dehydrogenase enzymes like CYP P450, the intermediate compounds are converted into a wide variety of monoterpenes10. Despite many uncertainties, some studies have identified the precise mechanism by which monoterpenoid compounds such as carvacrol and linalool are formed16. However, in our knowledge, no reports have been made regarding the formation of cuminaldehyde, the most abundant compounds of B. persicum.

In this study, we aimed to provide a comprehensive understanding of the monoterpenoid biosynthetic pathway in B. persicum by integrating transcriptomic and metabolomics data (GC-MS). First, we introduced the fundamental transcriptomic statistics and provided an overall description of B. persicum transcriptome enrichment and differential expression patterns between the stem and inflorescence, with a particular focus on the monoterpenoid biosynthetic pathway. In the second part of the study, we specifically focused on identifying the genes involved in cuminaldehyde production. We conducted a literature review and examined the chemical structure and functional groups of these compounds. Based on this analysis, we hypothesize that cuminaldehyde is the final product of the main monoterpenoid pathway in B. persicum. According to this prediction, γ-terpinene undergoes aromatization to form p-Cymene, which is then oxidized in two sequential steps to produce cuminaldehyde. This transformation likely involves hydroxylation or oxidation processes to convert an alkane group into an aldehyde. Finally, by integrating transcriptomic data with metabolomics data (GC-MS), we explored the biosynthetic pathways of monoterpenoids in B. persicum, with a specific focus on the synthesis of cuminaldehyde and γ-terpinene.

Result

De novo transcriptome assembly and quality evaluation

The sequencing and assembly of raw reads yielded high-quality and reliable data. In total, approximately 178 million raw reads were obtained across all samples. Nearly 94–96% of the reads remained after trimming, with a Q30 quality score ranging from 94.30 to 95.98%. The GC content varied between 43.95% and 44.76%, aligning with expected values for plant transcriptomes. After trimming, approximately 1.45–3.23% of the reads were discarded, primarily due to adapter contamination and low-quality sequences (Table 1). More than 70% of the contigs were longer than 500 bp, while 50% were longer than 1000 bp (Fig. 2B). Transcriptome completeness analysis revealed that 80% of the contigs were of high quality, 6% were fragmented, and the remaining 14% were either missing or of low quality (Fig. 2A). The assembled transcriptome was clustered into 46,156 groups. The N50 and mean length of the contigs were 1,450 and 1,191, respectively. Overall, these results suggest that the assembly and resulting unigenes are of good quality and can be relied upon for further analysis.

Functional annotation, gene ontology classification, and enrichment analysis

An analysis of seven databases revealed that 91.7% of unigenes were present in at least one database. A high percentage of unigenes were annotated in the NR (Non-Redundant Protein Database) and NT (Nucleotide Database), with 89.6% and 80%, respectively, while the lowest percentage was associated with KOG at 23.36% (Fig. 3A). Based on an evaluation of annotated unigene terms in NR, 89% showed similarity to Daucus carota L., followed by Vitis vinifera L. (4.8%) (Fig. s1).

GO analysis indicated that a significant portion of the transcriptome was involved in metabolic and cellular processes within the biological process category. Binding and catalytic activities constituted the majority of the molecular function category. In the cellular component category, the terms “cell,” “cell part,” “membrane,” “organelle,” and “membrane part” had the highest number of unigenes (Fig. 3B).

Differential gene expression between stem and inflorescence tissues

The analysis of gene expression levels between stem and inflorescence samples revealed distinct expression patterns. The mapping of each sample’s reads to the de novo assembled reference transcriptome was reliable, with over 85% of each sample successfully mapped (Table 2). Principal Component Analysis (PCA) indicated clear differences in gene expression patterns between the two groups (Fig. 4A). Additionally, overall gene expression levels were higher in the inflorescence compared to the stem (Fig. 4B). Differential expression analysis identified approximately 20,000 genes, with around 10,000 genes significantly more highly expressed in each group (Fig. 4C).

KEGG pathway enrichment of DEGs highlighting monoterpenoid biosynthesis

Through meticulous analysis of both shared and differentially expressed genes, we determined that gene clusters are more abundant in nearly all metabolic processes in the inflorescence compared to the stem (Fig. 5). This disparity is particularly pronounced in metabolic pathways related to secondary metabolites. A detailed breakdown of the BLAST processing, focusing on pathways directly or indirectly involved in the production of monoterpenoids, is presented in Table 3. It is observed that, in nearly all processes related to the production of terpenoids, and particularly monoterpenoids, the inflorescence exhibits a greater number of gene clusters. Accordingly, out of approximately 200 blasted clusters (including 163 KO-terms) involved in the production of monoterpenoids and polyketides, 188 clusters (72 KO-terms) were found in both inflorescence and stem tissues. As with other processes, the inflorescence contained more clusters than the stem (122 clusters and 54 KO-terms), while the stem contained 86 clusters (37 KO-terms)17,18.

Expression analysis and validation of monoterpenoid biosynthesis pathway

Earlier, it was noted that the inflorescence was more active in producing secondary metabolites, especially monoterpenoids, than the stem. The BLAST results revealed that at least one cluster per gene was identified for both the cytoplasmic and mitochondrial pathways of terpenoid backbone biosynthesis (Fig. s2). Upon analyzing the expression levels of unigenes derived from sequencing for the first and second steps of the monoterpenoid pathway, which culminate in GPP production, the average expression levels of the clusters in the inflorescence were significantly higher than in the stem (Fig. 6A). Real-time PCR analysis of genes such as Mevalonate kinase (MVK) and Isopentenyl shikimate kinase (ISPH) further confirmed the sequencing results, showing that the inflorescence exhibited significantly higher gene expression levels compared to the stem (Fig. 6B)17.

Terpenoids precursor production pathway expressions of B. persicum. (A) Illustration cytoplasmic and mitochondrial pathways of terpenoid precursor (GPP) production based on mean of Log2 FPKM (Fragments per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads) of inflorescences and stems of B. persicum. (B) The results of real-time PCR for confirmation of the sequencing results. ***, indicates the significant level of 0.001.

Prediction of cuminaldehyde biosynthesis pathway and essential oil analysis by GC-MS

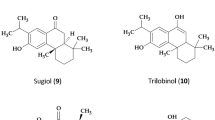

Reviewing of the previous research indicated that there was a meaningful relation between the B. persicum essential compound composition. Based on this relation and considering their chemical structure, we predicted a possible model of cuminaldehyde biosynthesis in B. persicum fruit (Fig. 7A; Table 4). In this mean, two steps are proposed to convert p-Cymene to cuminaldehyde, which includes two steps of oxidation on the alkane group to convert this group to an aldehyde group, and as a result, p-Cymene convert to cuminaldehyde.

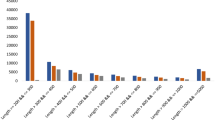

In the present study, the results of GC-MS showed a significant difference in the composition of compounds in stem and inflorescence essential oils (Table s1a and s1b). Based on the results, it appears that the inflorescence produces significantly elevated levels of cuminaldehyde and γ-terpinene than the stem. In contrast, the stem contains predominantly germacrene D and caryophyllene (Fig. 8). Considering the amount of dry tissue used for essential oil preparation, both stems and inflorescences are active in producing cuminaldehyde, but evidently, inflorescence produce much greater levels than stem.

Final candidate genes identified through keyword-based search and correlation analysis. (A) Clustering and correlation of the selected genes. (B) Positioning of the selected genes on the volcano plot of differentially expressed genes (DEGs). Cumin cuminaldehyde, Dehydro dehydrogenase, Hydro hydrogenase, C-alcohol cuminic alcohol, Cyt cytochrome, Gamma T γ-Terpinene.

It should be noted that, based on a review of past studies and the results from the GC-MS analysis in this study (Fig. 9), there is a discrepancy regarding the expected levels of cuminic alcohol, which are lower than anticipated (around 10%). However, some studies have reported amounts of this compound that align with the predictions and expectations of this study19,24. This discrepancy, however, warrants further detailed investigation.

Keyword-based search in the annotation data file and correlation analysis

Through correlation analysis and keyword-based searches in the annotation data file (Additional File 1), 31 genes were identified as final candidates for the predicted pathway. Correlating compound levels in each tissue with gene expression levels revealed that each cluster had similar term categories (Fig. 8A). The volcano plot (Fig. 8B) showed that all selected genes were positioned in the upper right quadrant, indicating their significant differential expression. Notably, four genes (Cluster-2027.18783, Cluster-2027.16027, Cluster-2027.17744, and Cluster-2027.16026) were identified among the final gene list as the most likely candidates involved in the predicted cuminaldehyde biosynthesis pathway, based on their functional annotation and previous studies (Table 5). Additionally, several other selected genes appear to be promising candidates for facilitating specific reactions within this pathway. For instance, alcohol dehydrogenases (ADHs) and short-chain dehydrogenases/reductases (SDRs) have been previously reported to play a role in monoterpenoid transformation and biosynthesis16,25.

Final pathway proposal and gene validation in cuminaldehyde biosynthesis

As mentioned above, the final gene list is potentially capable of catalyzing each reaction in the pathway. However, the selection of the best candidate for each reaction was based on a review of the literature, differences in FPKM levels between the inflorescence and stem, and the levels of the compounds of interest (Fig. 7A). In the end, two genes, TPS1 and TPS2 (GTS), were selected as final candidates for catalyzing the conversion of GPP to γ-terpinene. This prediction has also been suggested in previous studies, indicating that this pathway requires two enzymatic reactions. Furthermore, for the downstream pathway following p-Cymene formation, which has not been previously studied, our results identified two genes from the CYP76B family as potential candidates, ultimately leading to the production of cuminaldehyde.

he gene expression results from real-time PCR align well with the sequencing data, showing significantly higher expression in the inflorescence than in the stem (Fig. 7B, C). Additionally, band density analysis confirms both gene expression and the quality of the assembled transcriptome (Fig. s3)17,26. Of note, the primers were developed using the shared region of the two CYP76B fragments.

Differential abundance of transcription factors in inflorescence and stem tissues

In the inflorescence tissue of B. persicum, a comprehensive analysis of transcription factors (TFs) revealed a total of 2505 TFs. Among these, the MYB, SNF2, C2H2, and C3H families were identified, with respective counts of 18, 12, 11, and 11. Additionally, the AP2, MYB, WRKY, and bZIP families were predominant in stem tissues, with counts of 30, 22, 21, and 20, respectively (Fig. 10).

Discussion

Several studies have investigated the compounds in B. persicum fruit essential oil, and the majority have identified cuminaldehyde, γ-terpinene, and p-Cymene as the three most abundant constituents (Table 4). However, the biosynthetic pathway of cuminaldehyde has not been proposed until now. In the current study, the essential oil of B. persicum stem and inflorescence was analyzed using GC-MS during fruit development, revealing distinct monoterpene compositions between the two tissues. Despite the significant presence of cuminaldehyde in the inflorescence, the stem produced negligible amounts of this metabolite. Instead, it predominantly contained Caryophyllene and Germacrene D. Interestingly, Caryophyllene, which is abundant in the stem, has been reported to have therapeutic benefits27,28.

As evidenced by qualitative and quantitative analysis of the read lengths and the annotation of contigs in different databases, the raw data and assembled contigs of this study were highly reliable for further transcriptomic investigations of this plant. After de novo transcriptome assembly, approximately 46,000 unigenes were yielded from the transcriptome of this plant. The BUSCO results and quality control analysis conducted prior to assembly demonstrate that the resulting reads are of high quality and reliable for further analysis. In line with previous studies examining the transcriptomes of plants in the Apiaceae family, this study found the transcriptome to be most similar to that of carrot, as carrot is the only plant in the Apiaceae family with a complete genome sequence29. The study of green cumin (Cuminum cyminum L.), a species closely related to B. persicum, confirmed that cumin has a similar unigene count of 53,10330.

Our analysis of the cytoplasmic and mitochondrial pathways involved in terpenoid backbone biosynthesis in B. persicum revealed that all key genes were expressed in both the stem and inflorescence. Hereupon, study of Zeidabadi et al., has reported that two genes of both mitochondrial and cytoplasmic pathways (HMGR and IPI) were actively expressed during different growth stage of B. persicum fruit31. However, real-time PCR and sequencing data showed significantly higher expression levels in the inflorescence, suggesting a more active terpenoid biosynthesis in this tissue. This pattern is consistent with findings in other Apiaceae species, where fruits and seeds serve as major sites for terpenoid biosynthesis. For instance, in Cuminum cyminum L. (cumin), terpenoid accumulation is significantly higher in seeds compared to vegetative tissues, as these metabolites contribute to seed protection and dispersal32. Similarly, in Foeniculum vulgare Mill. (fennel), the fruit is the primary site of essential oil production, with key terpenoid biosynthetic genes showing higher expression compared to stems33. Our results reinforce the idea that reproductive structures, particularly fruits and seeds, prioritize terpenoid biosynthesis, likely due to their ecological roles in seed dispersal, defense, and germination success.

One of the most abundant compounds found in B. persicum and other Apiaceae family is γ-terpinene21. As of yet, a suggestion has been made for the production of γ-terpinene from geranyl pyrophosphate (GPP). In this process, the linalyl diphosphate is initially created by re-adding pyrophosphate to the Geranyl cation. Afterward, a linalyl cation is produced through ionization and isomerization of linalyl diphosphate. Next, the α-Terpinyl cation is created through 1,6 ring closure from a linalyl cation34. Finally, to produce γ-terpinene via a γ-terpinene synthase activity, the α-Terpinyl cation must first be converted to Terpinen-4-yl cation35. The driving genes of this reaction, according to reports and suggestions, are TPS1 and TPS2. While TPS1 proceed the initial part of the pathway, the creation of α-Terpinyl cation36 γ-terpinene synthase, which is a TPS2, catalyze the conversion of Terpinen-4-yl cation into γ-terpinene37. In line with our findings, some researchers have identified the γ-terpinene synthetase (TPS2) responsible for the production of γ-terpinene37,38,39. Our transcriptomic analysis identified two terpene synthase genes, TPS1 and TPS2, that exhibited significant expression in the inflorescence, the tissue with the highest γ-terpinene content. Previous studies have reported similar findings in other plants. The functional roles of these genes were supported by studies on other plants, where γ-terpinene synthase genes have been shown to play crucial roles in the biosynthesis of monoterpenes. For instance, Nigella sativa L. (black cumin), a plant known for its medicinal potential, has been found to produce γ-terpinene as a precursor to thymoquinone, the key bioactive compound in its seeds. In this plant, a γ-terpinene synthase (NsTPS1) was functionally characterized and shown to catalyze the conversion of geranyl diphosphate (GDP) into γ-terpinene38. Similarly, in Thymus vulgaris L. (thyme), the γ-terpinene synthase gene (Ttps2) has been sequenced and shown to play a key role in the production of thymol, a major essential oil compound in thyme species37. The co-expression of TPS1 and TPS2 with γ-terpinene accumulation in B. persicum inflorescence in our study supports their functional role in γ-terpinene biosynthesis from GPP, similar to findings in these other species.

Currently, some specific details regarding the biosynthesis of terpenoids, particularly monoterpenoids, remain unknown40,41. Since the enzymes responsible for the final stages of monoterpenoid production have not been well characterized10 still some uncertainty remains for downstream biosynthesis stages of monoterpenoids from GPP42. In general, however, cytochromes P450 enzymes and TPSs are the main candidates that could be the most potential candidate to advance the synthesis of these compounds43. Studies in the past somehow predicted the formation of p-Cymene from γ-terpinene16 however, the formation of cuminaldehyde from γ-terpinene in different plants have not been proposed. There has only been limited research reporting the conversion of the C-10 alkane group of p-Cymene to an aldehyde group in the past. However, this pathway was found only in bacteria, which is interestingly similar to our proposed pathway for producing cuminaldehyde from p-Cymene. In this process, which involves two oxidation steps, oxygenation and alcohol dehydrogenation, the alkane group is converted into aldehyde44,45. In the current study, four genes were proposed based on their relatively high expression and the high correlation between their differences in expression and differences in γ-terpinene and cuminaldehyde content in two tissues as candidate genes for accomplishing the proposed pathway. For this means, the results indicated that there were two Geraniol hydroxylase, belonging to the CYP76B and CYP76C family highly correlated with cuminaldehyde and γ-terpinene. Previous research showed that these genes could convert geraniol biphosphate into cyclic monoterpenoid intermediates through hydroxylation of an aldehyde group of acyclic compounds like geranyl cation46,47. Notably, the proposed reaction in current study needs conversion of an alkane group into an aldehyde of a cyclic compound (p-Cymene). To support this claim, a study has reported that this genes were also able to perform such rection on a cyclic compound a-terpineol and convert it into a 10-hydroxy-a-terpineol48. In addition, the carbon number 10 which is the target al.dehyde group of p-Cymene to be converted to cuminaldehyde has been shown to be hydroxylated by CYP76B and CYP76C family46,48.

Transcription factors (TFs) play a crucial role in regulating gene expression by modulating the expression levels of their target genes. Recent advancements in Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) techniques have facilitated the identification of TFs and their associated target proteins across diverse species49,50. In the context of terpenoid synthesis, the overexpression of specific TFs, such as MYB, bHLH, and NMN, has been observed to affect gene expression patterns, ultimately influencing the production of final terpenoid compounds51,52,53. Notably, our current research highlights a significant upregulation of the MYB family in B. persicum fruit, suggesting its potential role as a key enhancer in volatile compound production.

The distinct volatile compound compositions between the stem and inflorescence of B. persicum provide a valuable framework for studying the relationship between metabolite production and gene expression. In this study, we proposed candidate genes involved in the biosynthetic pathway of cuminaldehyde based on their expression levels and correlation with γ-terpinene and cuminaldehyde content. While CYP76B and CYP76C family genes emerged as the strongest candidates, it is important to acknowledge that other enzymes, such as neomenthol dehydrogenase and CYP76AE8, which exhibit alcohol dehydrogenase activity, could theoretically contribute to the conversion of cuminic alcohol into cuminaldehyde25,54. However, based on prior studies and correlation analyses, CYP76B and CYP76C were identified as the most plausible candidates. Nevertheless, we recognize that our conclusions are based on transcriptomic and metabolomic correlations rather than direct enzymatic assays. Additionally, the limited sample size (four biological replicates) may not fully capture the complexity of monoterpenoid biosynthesis in B. persicum. Further experimental validation, including enzyme functional characterization and a broader sampling approach, is necessary to confirm the proposed pathway and refine our understanding of cuminaldehyde biosynthesis.

Conclusions

This study provides the first comprehensive analysis of B. persicum’s transcriptome, identifying key genes involved in the biosynthesis of its volatile compounds, including cuminaldehyde. We found that the inflorescence, with higher expression of terpenoid biosynthetic genes, is more active in metabolite production, potentially linked to ecological functions like pollination and defense. Our data suggest that CYP76B and CYP76C genes are likely responsible for the final stages of cuminaldehyde production, while two terpene synthases (TPS1 and TPS2) play a crucial role in the conversion of γ-terpinene from GPP. However, further experimental validation is needed to confirm these findings.

These results offer valuable insights into B. persicum’s metabolic pathways and lay the groundwork for future research focused on optimizing its volatile compound production. A more comprehensive study, including larger sample sizes and functional validation, would be crucial not only to confirm these results but also to support the domestication and conservation of this endangered plant, potentially enhancing its productivity and essential oil yield. Additionally, a deeper understanding of the environmental factors that may influence the production of targeted metabolites would further enrich the findings and guide more effective cultivation strategies for this valuable species.

Materials and methods

Plant collection and RNA extraction

In late spring, we collected the aerial parts of Bunium persicum from the foothills of Kerman, while the fruits were in the middle stages of maturation (Fig. 1C). The collected samples were immediately transferred to liquid nitrogen. After brief disinfection, RNA extraction was performed according to the protocol of the Zist-Asia RNA extraction kit. Finally, the quality and quantity of RNA were measured using a 1% agarose gel, and the ratio of OD260/280 and OD260/230 was assessed with a NanoDrop spectrophotometer.

The botanical specimens were authenticated by Dr. Seyed Mansour Mirtadzadini, a botanist at the herbarium within the Shahid Bahonar University of Kerman’s biology department. The assigned specimen number is MIR: 4551 (https://biol.uk.ac.ir/). The specimens were obtained in accordance with governmental regulations.

cDNA library construction and sequencing

Four samples of B. persicum (two inflorescences and two stems) were sequenced by the Beijing Genomes Institute (China). First, their quality was checked using a Bioanalyzer, and samples with the highest RIN (above 8) were selected for sequencing. cDNA was synthesized using poly-A selection and then sequenced using the standard Illumina kit. Sequencing was performed with a read depth of 6 gigabases (per sample) in paired-end mode with a read length of 150 bp.

RNA sequencing data availability

Raw RNA sequencing data generated in this study have been deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) under the BioProject accession number PRJNA1105724. The corresponding SRA accession numbers are SRR28827920, SRR28827918, SRR28827917, and SRR28827919. All data are publicly available and can be accessed at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/PRJNA1105724.

Data processing and de novo transcriptome assembly

The quality control of the reads was checked before and after trimming by FastQC software (Version 0.11.9)55 in the Linux operating system environment. The raw reads were trimmed by Trimmomatic56 software (Version 0.37), and low-quality adapters and reads were removed. Due to the lack of a reference genome for B. persicum, the de novo assembled transcriptome for high quality reads was created by Trinity software (v2.13.2)57 and K-mer 32 was used to assemble the reads and the rest of its parameters were set to default. After that, CORSET58 software was applied to remove the redundance and them clustering the Trinity results. Hierarchical clustering performs based on multiple mapping events and expression pattern.

Functional annotation of assembled transcriptome

After assembling, to evaluate the quality of the reconstructed transcript, the unigenes were analyzed using BUSCO tool59. To perform functional annotation of unigenes, the nucleotide sequences were first converted to amino acid sequences by Trans-Decoder software60 (an ORF prediction software) with default parameters. Subsequently, for gaining functional annotation of unigenes, all unigenes were blasted against databases such as NR61 NT62 SwissProt63 KOG64 and KEGG65 with the BLASTx66 program (E-value ≤ 1e-5). Data were analyzed utilizingBlast2GO67 to acquire GO annotation of the unigenes. Metabolic pathways were achieved based on the KEGG (KAAS68 and BlastKOALA65) pathway database. In the study, the PlantTFDB (http://planttfdb.gao-lab.org) was employed to identify and classify transcription factors (TFs) associated with B. persicum69.

Differential gene expression analysis

To evaluate the gene expression, the number of Illumina reads was measured employing Bowtie 270 with default parameters, which characterized each unigene expression level of each sample. The quantities of assembled transcripts were calculated by the RSEM software71. First, the reads were aligned back to the de novo assembled transcriptome utilizing Bowtie, after that the RSEM was used to calculate the number of aligned reads for each sample. To standardize the expression of genes, the expression values of the unigenes were computed based on fragments per kilobase of transcript per million aligned reads (FPKM > 1) by RSEM software.

Differentially expressed contigs were identified from the count’s matrix estimated by RSEM through the edgeR using Rstudio. The TMM normalization were applied to adjust for any differences in sample composition. To obtain the differentially expressed genes (DEGs), a threshold false discovery rate (FDR) of ≤ 0.001 and an absolute value of log2 fold ratio ≥ 2 were used.

Identification of unigenes and gene families related to terpenoid biosynthesis

To elucidate the cuminaldehyde production pathway, we initially reviewed several studies that investigated the quantification of volatile compounds in B. persicum fruit. Then, based on the possibility of chemical conversion between compounds, a pathway for producing and converting compounds was suggested. For finding the target genes and due to the fact that there is little information on the function of genes involved in monoterpenoid production, this study attempted to introduce genes associated with the production pathway of black cumin’s most important compounds, First, by performing a keyword-based search in the annotation data file (keywords: P450, CYP, Cytochrome, Monooxygenase, Hydrogenases, Hydrolase, Dehydrogenase, TPS, Terpenoid synthase) to identify potential genes related to monoterpenoid biosynthesis. Next, following the selection of the most relevant genes, correlation analysis, and Euclidean relationships were determined between the level of gene expression and the level of metabolite production produced in the stem and inflorescence (using COR function and Pheatmap package in R). Finally, to identify conclusive candidate genes, we considered terminology, the feasibility of advancing the reaction by consulting various databases, the highest correlation, and the closest Euclidean relationship (Fig. 11).

Real time PCR

Three biological and three technical replicates were utilized to perform the qRT-PCR assay. The data were analyzed using SPSS software, employing the comparative threshold cycle (ΔCT) method to ascertain the relative gene transcription level. The primer sequences are available in Table s2.

Essential oil extraction and GC-MS analysis

Briefly, a Clevenger apparatus was used to prepare the essential oil. GC-MS analysis was performed with helium gas flowing at a rate of 1 mL/min, and the injector temperature was set at 250 °C. The oven temperature was maintained at 50 °C for 2 min before gradually increasing by 10 °C per minute, reaching 250 °C after 15 min. A Thermo Finnigan Trace DSQ GC-MS system was used for this analysis, with a 70 eV ionization energy, and the column operated using a DB-5 capillary column and helium as a carrier gas. The composition of the compounds was determined by comparing the relative retention times (RT) and mass spectra with those in standards, the NIST, Wiley, and Adam’s libraries of the GC-MS system, as well as from literary sources. Notably, to achieve an equivalent quantity of essential oil, varying weights of different tissues were required. Specifically, to yield 1 milliliter of essential oil, approximately 18 g of dry inflorescence tissue were used, while the same amount of essential oil required 100 g of dry stem tissue.

Data availability

Raw RNA sequencing data generated in this study have been deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) under the BioProject accession number PRJNA1105724. The corresponding SRA accession numbers are SRR28827920, SRR28827918, SRR28827917, and SRR28827919. All data are publicly available and can be accessed at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/PRJNA1105724.

Abbreviations

- Inflor:

-

Inflorescence

- GPP:

-

Geranyl pyrophosphate

- TPS:

-

Terpene synthases

- GTS:

-

γ-Terpinene synthetase

- B. persicum :

-

Bunium persicum

References

Sheidai, M., Ahmadian, P. & Poorseyedy, S. Cytological studies in Iran zira from three genus: Bunium, carum and cuminum. Cytologia (Tokyo). 61, 19–25 (1996).

Sofi, P. A., Zeerak, N. A. & Singh, P. Kala zeera (Bunium persicum Bioss.): A Kashmirian high value crop. Turk. J. Biol. 33, 249–258 (2009).

Bansal, S. et al. A comprehensive review of Bunium persicum: A valuable medicinal spice. Food Rev. Int. 39, 1184–1202 (2023).

Singh, S., Kumar, V. & Ramesh. Biology, genetic improvement and agronomy of Bunium persicum (Boiss.) fedtsch.: A comprehensive review. J. Appl. Res. Med. Aromat. Plants. 22, 100304 (2021).

Hassanzad Azar, H., Taami, B., Aminzare, M. & Daneshamooz, S. Bunium persicum (Boiss.) B. Fedtsch: An overview on phytochemistry, therapeutic uses and its application in the food industry. J. Appl. Pharm. Sci. 8, 150–158 (2018).

Ebada, M. E. Cuminaldehyde: A potential drug candidate. J. Pharmacol. Clin. Res. 2, 1–4 (2017).

Rustaie, A. et al. Essential oil composition and antimicrobial activity of the oil and extracts of Bunium persicum (Boiss.) B. Fedtsch.: Wild and cultivated fruits. Pharm. Sci. 22, 296–301 (2016).

Jalilzadeh-Amin, G., Nabizadeh, H. & Maham, M. Inhibitory effect of Bunium persicum Boiss essential oil on castor-oil induced diarrhea. J. Kerman Univ. Med. Sci. 21, 139–150 (2014).

Kumar, A. et al. Isoprenyl diphosphate synthases of terpenoid biosynthesis in rose-scented geranium (Pelargonium graveolens). Plant. Physiol. Biochem. 210, 108590 (2024).

Mahmoud, S. S. & Croteau, R. B. Strategies for transgenic manipulation of monoterpene biosynthesis in plants. Trends Plant. Sci. 7, 366–373 (2002).

Davis, E. M. & Croteau, R. Cyclization enzymes in the biosynthesis of monoterpenes, sesquiterpenes, and diterpenes. Biosynth. Aromat. Polyketid. Isopren. Alkaloids 209, 53–95 (2000).

Chen, F., Tholl, D., Bohlmann, J. & Pichersky, E. The family of terpene synthases in plants: A mid-size family of genes for specialized metabolism that is highly diversified throughout the kingdom. Plant. J. 66, 212–229 (2011).

Liu, L. et al. Integrating RNA-seq with functional expression to analyze the regulation and characterization of genes involved in monoterpenoid biosynthesis in Nepeta tenuifolia Briq. Plant. Physiol. Biochem. 167, 31–41 (2021).

Li, M. et al. Genome-wide identification and analysis of terpene synthase (TPS) genes in celery reveals their regulatory roles in terpenoid biosynthesis. Front. Plant. Sci. 13, 1010780 (2022).

Weitzel, C. & Simonsen, H. T. Cytochrome P450-enzymes involved in the biosynthesis of mono-and sesquiterpenes. Phytochem Rev. 14, 7–24 (2015).

Krause, S. T. et al. The biosynthesis of thymol, carvacrol, and thymohydroquinone in Lamiaceae proceeds via cytochrome P450s and a short-chain dehydrogenase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 118, e2110092118 (2021).

Kanehisa, M. & Goto, S. KEGG: Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 28, 27–30 (2000).

Kanehisa, M. Toward understanding the origin and evolution of cellular organisms. Protein Sci. 28, 1947–1951 (2019).

Chizzola, R., Saeidnejad, A. H., Azizi, M., Oroojalian, F. & Mardani, H. Bunium persicum: Variability in essential oil and antioxidants activity of fruits from different Iranian wild populations. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 61, 1621–1631 (2014).

Kareshk, A. T. et al. Efficacy of the Bunium persicum (Boiss) essential oil against acute toxoplasmosis in mice model. Iran. J. Parasitol. 10, 625 (2015).

Oroojalian, F., Kasra-Kermanshahi, R., Azizi, M. & Bassami, M. R. Phytochemical composition of the essential oils from three apiaceae species and their antibacterial effects on food-borne pathogens. Food Chem. 120, 765–770 (2010).

Jamshidi, A., Khanzadi, S., Azizi, M., Azizzadeh, M. & Hashemi, M. Modeling the growth of Staphylococcus aureus as affected by black zira (Bunium persicum) essential oil, temperature, pH and inoculum levels. Vet. Res. Forum Int. Q. J. 5, 107 (2014).

Hajhashemi, V., Sajjadi, S. E. & Zomorodkia, M. Antinociceptive and anti-inflammatory activities of Bunium persicum essential oil, hydroalcoholic and polyphenolic extracts in animal models. Pharm. Biol. 49, 146–151 (2011).

Sharififar, F., Yassa, N. & Mozaffarian, V. Bioactivity of major components from the seeds of Bunium persicum (Boiss.) FEDTCH. Pak J. Pharm. Sci. 23, 300–304 (2010).

Colonges, K. et al. Two main biosynthesis pathways involved in the synthesis of the floral aroma of the Nacional cocoa variety. Front. Plant. Sci. 12, 681979 (2021).

Kanehisa, M., Furumichi, M., Sato, Y., Matsuura, Y. & Ishiguro-Watanabe, M. KEGG: biological systems database as a model of the real world. Nucleic Acids Res. 53, D672–D677 (2025).

Fidyt, K., Fiedorowicz, A., Strządała, L. & Szumny, A. β-caryophyllene and β‐caryophyllene oxide—Natural compounds of anticancer and analgesic properties. Cancer Med. 5, 3007–3017 (2016).

Scandiffio, R. et al. Protective effects of (E)-β-caryophyllene (BCP) in chronic inflammation. Nutrients 12, 3273 (2020).

Soltani Howyzeh, M., Noori, S. A. S., Shariati, V. & Amiripour, M. Comparative transcriptome analysis to identify putative genes involved in thymol biosynthesis pathway in medicinal plant Trachyspermum ammi L. Sci. Rep. 8, 1–19 (2018).

Sadeghi, D., Mortazavian, M. M. & Bakhtiyarizadeh, M. R. Transcriptome analysis of Cumin (Cuminum cyminum L.) using RNA-Seq. Agric. Biotechnol. J. 9, 101–116 (2018).

Zeidabadi, D. D., Javaran, M. J., Dehghani, H., Monfared, S. R. & Baghizadeh, A. An investigation of the HMGR gene and IPI gene expression in black caraway (Bunium persicum). 3 Biotech 8, (2018).

Bahraminejad, A., Mohammadi-Nejad, G., Abdul Kadir, K., Bin Yusop, M. R. & Samia, M. A. Molecular diversity of Cumin (‘Cuminum cyminum’ L.) using RAPD markers. Aust J. Crop Sci. 6, 194–199 (2012).

Telci, I., Demirtas, I. & Sahin, A. Variation in plant properties and essential oil composition of sweet fennel (Foeniculum vulgare Mill.) fruits during stages of maturity. Ind. Crops Prod. 30, 126–130 (2009).

Srividya, N., Davis, E. M., Croteau, R. B. & Lange, B. M. Functional analysis of (4 S)-limonene synthase mutants reveals determinants of catalytic outcome in a model monoterpene synthase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 112, 3332–3337 (2015).

Lima, A. S. et al. Genomic characterization, molecular cloning and expression analysis of two terpene synthases from Thymus caespititius (Lamiaceae). Planta 238, 191–204 (2013).

Gao, Y., Honzatko, R. B. & Peters, R. J. Terpenoid synthase structures: A so far incomplete view of complex catalysis. Nat. Prod. Rep. 29, 1153–1175 (2012).

Tohidi, B., Rahimmalek, M., Arzani, A. & Trindade, H. Sequencing and variation of terpene synthase gene (TPS2) as the major gene in biosynthesis of thymol in different thymus species. Phytochemistry 169, 112126 (2020).

Elyasi, R. et al. Identification and functional characterization of a γ-terpinene synthase in Nigella sativa L (black cumin). Phytochemistry 202, 113290 (2022).

Rudolph, K. et al. Expression, crystallization and structure elucidation of γ-terpinene synthase from Thymus vulgaris. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. F Struct. Biol. Commun. 72, 16–23 (2016).

Nagegowda, D. A. & Gupta, P. Advances in biosynthesis, regulation, and metabolic engineering of plant specialized terpenoids. Plant. Sci. 294, 110457 (2020).

Yang, P. et al. Chromosome-level genome assembly and functional characterization of terpene synthases provide insights into the volatile terpenoid biosynthesis of Wurfbainia villosa. Plant. J. 112, 630–645 (2022).

Lu, X. et al. Cyclization mechanism of monoterpenes catalyzed by monoterpene synthases in dipterocarpaceae. Synth. Syst. Biotechnol. 9, 11–18 (2024).

Hao, D. L. et al. Function and regulation of ammonium transporters in plants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21, 3557 (2020).

Eaton, R. W. p-Cymene catabolic pathway in Pseudomonas putida F1: Cloning and characterization of DNA encoding conversion of p-cymene to p-cumate. J. Bacteriol. 179, 3171–3180 (1997).

Agullo, L., Romero-Silva, M. J., Domenech, M. & Seeger, M. p-Cymene promotes its catabolism through the p-cymene and the p-cumate pathways, activates a stress response and reduces the biofilm formation in Burkholderia xenovorans LB400. PLoS One. 12, e0169544 (2017).

Zhu, X., Zeng, X., Sun, C. & Chen, S. Biosynthetic pathway of terpenoid Indole alkaloids in Catharanthus roseus. Front. Med. 8, 285–293 (2014).

Ilc, T., Parage, C., Boachon, B., Navrot, N. & Werck-Reichhart, D. Monoterpenol oxidative metabolism: Role in plant adaptation and potential applications. Front. Plant. Sci. 7, 509 (2016).

Höfer, R. et al. Dual function of the cytochrome P450 CYP76 family from Arabidopsis thaliana in the metabolism of monoterpenols and phenylurea herbicides. Plant. Physiol. 166, 1149–1161 (2014).

Liu, Z. et al. Identification of novel regulators required for early development of vein pattern in the cotyledons by single-cell RNA‐sequencing. Plant. J. 110, 7–22 (2022).

Soltani, N., Firouzabadi, F. N., Shafeinia, A., Shirali, M. & Sadr, A. S. De novo transcriptome assembly and differential expression analysis of catharanthus roseus in response to salicylic acid. Sci. Rep. 12, 17803 (2022).

Dong, Y. et al. The transcription factor LaMYC4 from lavender regulates volatile terpenoid biosynthesis. BMC Plant. Biol. 22, 289 (2022).

Van Moerkercke, A. et al. The bHLH transcription factor BIS1 controls the iridoid branch of the monoterpenoid indole alkaloid pathway in Catharanthus roseus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 112, 8130–8135 (2015).

Zhang, H. et al. The basic helix-loop‐helix transcription factor CrMYC2 controls the jasmonate‐responsive expression of the ORCA genes that regulate alkaloid biosynthesis in Catharanthus roseus. Plant. J. 67, 61–71 (2011).

Ikeda, H. et al. Acyclic monoterpene primary alcohol: NADP + oxidoreductase of Rauwolfia serpentina cells: The key enzyme in biosynthesis of monoterpene alcohols. J. Biochem. 109, 341–347 (1991).

Andrews, S. FastQC: A quality control tool for high throughput sequence data. Available at: https://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/ (2010).

Bolger, A. M., Lohse, M. & Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: A flexible trimmer for illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 30, 2114–2120 (2014).

Grabherr, M. G. et al. Full-length transcriptome assembly from RNA-Seq data without a reference genome. Nat. Biotechnol. 29, 644–652 (2011).

Davidson, N. M. & Oshlack, A. Corset: enabling differential gene expression analysis for de novo assembled transcriptomes. Genome Biol. 15, 1–14 (2014).

Seppey, M., Manni, M. & Zdobnov, E. M. BUSCO: Assessing genome assembly and annotation completeness. Methods Mol. Biol. 1962, 227–245 (2019).

Haas, B. J. et al. De novo transcript sequence reconstruction from RNA-seq using the trinity platform for reference generation and analysis. Nat. Protoc. 8, 1494–1512 (2013).

Benson, D. A. et al. GenBank. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, D36–D42 (2012).

Wheeler, D. L. et al. Database resources of the national center for biotechnology information. Nucleic Acids Res. 36, D13–D21 (2007).

Bairoch, A. & Apweiler, R. The SWISS-PROT protein sequence database and its supplement trembl in 2000. Nucleic Acids Res. 28, 45–48 (2000).

Tatusov, R. L., Galperin, M. Y., Natale, D. A. & Koonin, E. V. The COG database: A tool for genome-scale analysis of protein functions and evolution. Nucleic Acids Res. 28, 33–36 (2000).

Kanehisa, M., Sato, Y. & Morishima, K. BlastKOALA and ghostkoala: KEGG tools for functional characterization of genome and metagenome sequences. J. Mol. Biol. 428, 726–731 (2016).

Altschul, S. F., Gish, W., Miller, W., Myers, E. W. & Lipman, D. J. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 215, 403–410 (1990).

Conesa, A. et al. Blast2GO: A universal tool for annotation, visualization and analysis in functional genomics research. Bioinformatics 21, 3674–3676 (2005).

Moriya, Y., Itoh, M., Okuda, S., Yoshizawa, A. C. & Kanehisa, M. KAAS: An automatic genome annotation and pathway reconstruction server. Nucleic Acids Res. 35, W182–W185 (2007).

Jin, J., Zhang, H., Kong, L., Gao, G. & Luo, J. PlantTFDB 3.0: A portal for the functional and evolutionary study of plant transcription factors. Nucleic Acid Res. 42, D1182–D1187. (2014). https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkt1016

Langmead, B. & Salzberg, S. L. Fast gapped-read alignment with bowtie 2. Nat. Methods. 9, 357–359 (2012).

Li, B. & Dewey, C. N. RSEM: Accurate transcript quantification from RNA-Seq data with or without a reference genome. BMC Bioinform. 12, 1–16 (2011).

Funding

The authors state that they did not receive any financial support for conducting the research, writing the article, or publishing it.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

E.L and M.R.S.B: The experiments were designed and planned. M.R.S.B, B.K, M.H and K.E.S: performed the data analysis experiments. M.R.S.B, M.H and N.S: performed dry-lab experiment. M.R.S.B, K.E.S and E.L: wrote the manuscript. Each author made contributions to the manuscript’s final version.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Samandari-Bahraseman, M.R., Hajibarati, M., Khorsand, B. et al. Deciphering the biosynthesis pathway of gamma terpinene cuminaldehyde and para cymene in the fruit of Bunium persicum. Sci Rep 15, 22438 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-05415-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-05415-0