Abstract

This study investigated the antioxidant capacity, biochemical composition, nutrient content, and morphological traits of 21 mulberry genotypes grown under the same ecological conditions in Türkiye. These genotypes, representing Morus alba, M. nigra, M. rubra, and unidentified species, were cultivated to evaluate their genetic diversity and potential for functional applications. The genotype ‘Gosho Erami’ exhibited the highest performance across total antioxidant activity (87%), phenolic contents (40.58 mg GAE/100 g), and flavonoid contents (6.48 mg QE/100 g), while ‘Hatay Dörtyol Mordut’ had the lowest values (50.61%, 20.33 mg GAE/100 g, and 2.11 mg QE/100 g, respectively). Among nutrients, calcium content ranged from 5733 (‘Şelale Karadut’) to 32.525 mg/kg (‘44 MRK 01’), iron content changed between 59.45 (‘Mersin Köy Hizmetleri Mordut’) and 101.99 mg/kg (‘Topu Beyaz-2 (24-03)’), and zinc content varied between 7.50 (‘Kastamonu Beyaz’) and 16.37 mg/kg (‘Topu Beyaz-2 (24 − 03)’). Leaf morphology showed significant variation, with leaf length ranging from 65.4 (‘Amasya Beyaz’) to 135.3 mm (‘44 BA 05’) and petiole length from 13.38 (‘Erzincan Karadut’) to 46.36 mm (‘44 BA 05’). Principal component analysis revealed that the first three components accounted for 56.05% of the total variation, with PC1 (26.85%) being primarily influenced by potassium (0.35), sodium (0.32), manganese (0.30), zinc (0.30), aluminum (0.26), and leaf length (0.26). Multiple regression analysis showed that manganese significantly influenced total phenolics (β = 0.38, p < 0.03) and total flavonoids (β = 0.75, p < 0.00). Heat map analysis clustered the genotypes ‘Gosho Erami’ and ‘44 BA 05’ with total phenolics, flavonoids, and antioxidant capacity, highlighting their biochemical superiority. This study has shown that different origin mulberry genotypes grown in Türkiye exhibit significant genetic diversity and have important potential for nutritional supplements and functional food applications. Our study’s 21 quantitative data sets revealed that the genotypes with the highest overall values were ‘25 UZ 08’, ‘Ichinose’, and ‘44 BA 05’, while those with the lowest values were ‘44 MRK 01’, ‘Ship Yeoung’, and ‘Şelale Karadut’. These findings emphasize the importance of integrating biochemical, nutritional, and morphological analyses to maximize the agricultural and economic benefits of mulberry resources.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Throughout history, humans relied on natural resources. Due to their richness in nutrients and functional compounds, plants serve as food, medicine, and for various other uses. Among these, mulberry stands out as one of the most valuable trees1. Mulberry (Morus), a characteristic plant of East Asia, belongs to the family Moraceae. It is a perennial tree or shrub of significant economic value. The plant thrives in diverse ecological and geographical regions, ranging from intensive cultivation in temperate, subtropical, and tropical zones to its natural presence in forests worldwide2. This widespread adaptability highlights mulberry’s strong morphological and physiological resilience to environmental fluctuations. Mulberry can be cultivated in various forms, such as bush, dwarf, or tree, and each form can be sustained through distinct cultural practices3. The genus Morus primarily comprises three key species: white mulberry (Morus alba), red mulberry (M. rubra), and black mulberry (M. nigra)4. Mulberry leaves are vibrant green, arranged alternately, and feature a heart-shaped base, a pointed tip, serrated margins, and a slender petiole. The length and shape of the leaves vary greatly, even on the same tree. Some leaves remain simple, while others exhibit a lobed, almost palmate structure5.

Mulberry leaves, widely recognized as the primary feed for silkworms, have also been a key component of traditional Chinese medicine for over 3000 years. Historically, they have been used to treat ailments such as colds, diabetes, and various other conditions6,7. Today, the Ministry of Public Health of China has officially approved mulberry leaves as a pharmaceutical and food resource. In recent years, they have gained commercial popularity as a unique type of tea across countries like China, Japan, Korea, Thailand, and other parts of Asia8,9. Additionally, in certain regions of China, tender shoots and young mulberry leaves are consumed as a specialty vegetable.

The nutritional value of vegetables is largely influenced by their protein, carbohydrate, vitamin, nutrient, and dietary fiber content. However, when used in functional foods or specialty teas, the focus often shifts to the bioactive compounds they contain and their associated bioactivities. Mulberry leaves are an exceptional food resource due to their rich composition of protein, carbohydrates, vitamins, nutrient elements, and dietary fiber10,11. Furthermore, studies have shown that mulberry leaves are abundant in bioactive compounds such as phenolic acids, flavonoids, alkaloids, and γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA)10,12. These compounds are known to provide numerous health benefits, including antioxidant activity13, blood sugar reduction14, antihypertensive effects15, prevention of atherosclerosis16, and anti-inflammatory properties17.

One of the most notable bioactive compounds found in mulberry leaves is 1-deoxynojirimycin (DNJ), a powerful α-glycosidase inhibitor. DNJ has demonstrated promising therapeutic effects on various conditions, particularly type II diabetes8,18.

Although the beneficial properties of mulberry leaves have been well documented, comprehensive investigations into their biochemical composition, antioxidant potential, and nutrient profile within the context of Türkiye’s diverse genetic resources remain limited. This study seeks to fill this research gap by systematically evaluating the antioxidant activity, biochemical constituents, nutrient levels, and morphological characteristics of mulberry leaves derived from a broad range of genotypes within Türkiye’s mulberry germplasm. By adopting a holistic assessment approach, the research aims to advance our understanding of mulberry as a multifunctional crop and to generate valuable data for its prospective utilization in agricultural, nutritional, and health-related sectors.

Materials and methods

Plant material

The study was carried out in the ‘Mulberry Genetic Resources Parcel’ located in the Central district of Malatya province (38° 19’ 26" N, 38° 17’ 09" E), affiliated to the Malatya Apricot Research Institute Directorate of the General Directorate of Agricultural Research and Policies of the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry of the Republic of Türkiye, in 2022 and 2023 (Fig. 1). Malatya Province is characterized by a climate of hot, arid summers and cold, rainy winters, with an average annual precipitation of 350 mm and a mean temperature of 14 °C. Chemical composition, nutrient content, and morphological traits were analyzed using the leaves of 21 mulberry genotypes belonging to different species. This study is part of a long-term mulberry selection project. As part of this program, superior genotypes have been selected based on preliminary evaluations and transferred to a field collection plot for further characterization studies. Additionally, several genotypes from different countries have been incorporated into the selection program, aiming to conserve genetic diversity and ensure its sustainable utilization. Detailed information about the genotypes used in the study is presented in Table 1. Of the 21 mulberry genotypes examined within the scope of the study, 8 belong to the M. alba, 4 to the M. nigra, and 2 to the M. rubra. Studies to determine the species of the 7 genotypes whose species are unknown are continuing within the scope of a separate project19. The genotypes, aged between 15 and 25 years, were cultivated at 3 × 5 m planting intervals and were in good health, exhibiting full fruit development. Standard cultural practices, including fertilization, irrigation, pest management, and disease control, were meticulously performed throughout the study.

The formal identification of the samples was performed by Dr. Yazgan Tunç.

Chemical characteristics

Sample preparation

Biochemical analyses were performed with three replications, each consisting of 50 leaves. For the biochemical analyses, leaves of various sizes were carefully collected from different orientations of the tree to ensure that the samples were representative of the entire canopy. This sampling strategy was designed to capture the potential variability within each tree and to provide reliable and comprehensive data for the analyses. Sample preparation was carried out using the method outlined by Hannachi et al.20. The biochemical components were extracted using a maceration technique with agitation for 24 h at 25 °C, employing 80% methanol as the extraction solvent. The resultant extract was filtered and then subjected to centrifugation (Hettich H-1650R, Tuttlingen, Germany) at 11,200×g for 15 min. The methanolic extracts derived from mulberry leaves were subsequently utilized to assess the biochemical content.

Total antioxidant activity (TAA)

The total antioxidant activity (TAA) of mulberry leaves was assessed using the procedure outlined by Sharma and Bhat21. A 0.26 mM DPPH (1,1-diphenyl-2-picryl-hydrazyl) solution was employed for the assay. For each mulberry genotype, 100 µL of leaf extract was mixed with 2900 µL of ethanol and 1 mL of DPPH solution. The mixture was shaken and incubated in the dark for 30 min. Following incubation, the absorbance of the sample was measured at 517 nm using a spectrophotometer (Systonic 119 UV-VIS, Haryana, India), and the absorbance of the leaf extract [A(sample)] was recorded. A blank solution, which contained no mulberry extract, served as a control, and its absorbance [A(blank)] was also measured22. The antioxidant activity was calculated using the formula presented in Eq. 123.

Total phenolics (TPs)

The total phenolics (TPs) in mulberry leaves were determined through the Folin-Ciocalteu method as described by Lamuela-Raventós24. 500 µL of fresh leaf extract was mixed with 4.1 mL of distilled water and then 100 µL of Folin-Ciocalteu reagent and 2% sodium carbonate (Na2CO3) were added. The solution was incubated for two hours in darkness and subsequently analyzed at 760 nm using a spectrophotometer. Absorbance values were converted to gallic acid equivalents (GAE) based on a standard curve constructed with gallic acid and reported as mg/100 g FW (fresh weight).

Total flavonoids (TFs)

The total flavonoids (TFs) in mulberry leaves were evaluated according to the methodology described by Demir et al.25. A 1000 µL sample from each genotype was mixed with 3.3 mL of methanol, followed by the addition of 0.1 mL of a 10% aluminum chloride hexahydrate (AlCl3·6H2O) solution and potassium acetate (CH3COOK). The mixtures were then analyzed using a spectrophotometer at a wavelength of 415 nm. The flavonoid content was quantified as quercetin equivalents (QE) and expressed in mg/100 g25.

Nutritional content characteristics

The mineral analysis of mulberry leaves [Aluminum (Al), Boron (B), Calcium (Ca), Carbon (C), Iron (Fe), Potassium (K), Magnesium (Mg), Manganese (Mn), Sodium (Na), Nickel (Ni), Phosphorus (P), Lead (Pb), Sulfur (S), Zinc (Zn)] was performed with three replicates, using 100 leaves for each replicate26. The nutrient evaluation involved healthy leaves selected as representative of varietal traits from four different sections of the tree. The samples were initially ground, and 0.25 g of this ground plant material was digested using 0.5 ml of nitric acid (HNO3) and 2 ml of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) according to the method described by Miller27. After digestion, the leaf samples were dried in an oven at 68 °C for 48 h (Nükleon NKD1000, Ankara, Türkiye)28. The dried and digested samples were then processed in an oven (Refsan, RK55, Kütahya, Türkiye) following a three-step procedure as described by Mertens (2005): (1) 5 min at 145 °C with 75% relative humidity, (2) 10 min at 180 °C with 90% relative humidity, and (3) 10 min at 100 °C with 40% relative humidity. Finally, the nutrient concentrations in the processed samples were determined in mg/kg using an inductively coupled plasma spectrophotometer (ICP) (Perkin-Elmer, Optima 2100 DV, ICP/OES, Shelton, CT 06484 − 4794, USA)29.

Morphological characteristics

Leaf morphology was analyzed in three replicates, with each replicate consisting of 100 leaves. The measured parameters included leaf length, leaf width, petiole length, and petiole width. All measurements were taken using a digital caliper from the Insize brand (model 1108 − 150). To ensure precision, the measurements were conducted under standardized laboratory conditions. The digital caliper provided accurate readings of leaf and petiole dimensions, and all data were recorded in millimeters (mm).

Statistical analysis

The research was carried out in 2022 and 2023. To enhance reliability and minimize the effects of temporal variations, statistical analyses were performed using the averaged data from both years. The statistical evaluations for leaf antioxidant capacity, biochemical composition, nutrient content, and morphological characteristics were conducted using JMP® Pro 17 software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA)30. The significance of the findings was determined with the TUKEY multiple comparison test, applying a significance level of 5% (p < 0.05). All datasets were presented as mean ± standard deviation31.

For multivariate analyses, correlation matrix analysis, principal component analysis, and heat map analysis were performed with Origin Pro® 2024b software32. The Pearson correlation coefficient (r) was used in the correlation matrix analysis (CMA) to determine the strength and direction of relationships between variables. Principal component analysis (PCA) utilized the Varimax rotation method with Kaiser Normalization to enhance the clarity of the components. A two-dimensional biplot was created to represent the first and second principal components (PC1/PC2) for visualizing genotype distribution and their associated variables. In addition, principal component scores of different mulberry genotypes were extracted and interpreted to quantify their relative positioning within the multivariate space and to support clustering and trait-association inferences. Ward’s method combined with heat map analysis (HMA) based on Euclidean distance coefficients was applied to cluster genotypes and variables, providing an in-depth visualization of their relationships.

Additionally, multiple regression analysis (MRA) was used to identify the traits influencing key leaf characteristics, with certain leaf traits treated as dependent variables. The MRA was performed using the ‘‘stepwise’’ method within the ‘‘linear regression analysis’’ option of SPSS® software [SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA33,34,35. The application of these multivariate statistical methods enabled a comprehensive understanding of the interrelationships among leaf antioxidant capacity, biochemical composition, nutrient content, and morphological traits, providing significant insights into the categorization and classification of mulberry genotypes.

Results and discussion

Descriptive statistics among genotypes

The detailed TUKEY analysis results for the statistical descriptive parameters of biochemical traits among mulberry genotypes are presented in Table 2, demonstrating significant differences in total antioxidant activity, total phenolic content, and total flavonoid content (One-way ANOVA, p < 0.05). These variations were observed among 21 mulberry genotypes cultivated under identical ecological and climatic conditions within the same experimental parcel, reflecting the genetic and biochemical diversity inherent to the studied genotypes.

The genotype ‘Gosho Erami’ emerged as the highest-performing genotype, achieving the highest values across all measured parameters, including antioxidant activity (87%), phenolic content (40.58 mg GAE/100 g), and flavonoid content (6.48 mg QE/100 g). These superior results indicate an enhanced ability of this genotype to synthesize bioactive compounds, which are critical for oxidative stress management and overall metabolic efficiency. This exceptional performance may be attributed to the genotype’s genetic potential, efficient physiological processes, or optimized resource utilization under the specific environmental conditions of the study. Consequently, ‘Gosho Erami’ presents itself as a promising candidate for nutraceutical applications and breeding programs aimed at improving functional food properties.

In contrast, the genotype ‘Hatay Dörtyol Mordut’ recorded the lowest performance, with significantly reduced antioxidant activity (50.61%), phenolic content (20.33 mg GAE/100 g), and flavonoid content (2.11 mg QE/100 g). These findings suggest potential limitations in its metabolic pathways for secondary metabolite production or a weaker adaptation to the study’s environmental conditions. While this genotype may have limited use in high-value applications, its agronomic traits could still make it suitable for purposes such as biomass production or traditional uses.

The observed variability in biochemical traits among the genotypes highlights the influence of genetic and environmental factors on the synthesis of secondary metabolites. Antioxidant activity is strongly linked to phenolic and flavonoid content36, as these compounds are key contributors to a plant’s ability to neutralize reactive oxygen species37. The significant differences between genotypes underline the need for targeted genotype selection to optimize the desired biochemical properties in mulberry cultivation38. Additionally, genotypes with high bioactive compound content, such as ‘Gosho Erami’, could serve as valuable resources for industries focused on functional foods, pharmaceuticals, and health supplements39.

In a study conducted on mulberry in China, total antioxidant activity was reported to range between 43.57 and 81.41%, while total phenolics varied from 24.43 to 39.38 mg GAE/100 g40. Our findings are consistent with those reported by these researchers. Total flavonoid content was reported to range between 9.84 and 26.6 mg QE/100 g in the study conducted in China41 and between 0.90 and 67.37 mg QE/100 g in Serbia42. The total flavonoid results in our study fall within the range reported by Radojković et al.42 but are lower than those documented by Zhishen et al.41. This discrepancy could be attributed to differences in genotypes, environmental conditions, and cultivation practices, which are known to significantly influence the synthesis and accumulation of secondary metabolites in plants43.

These findings provide important insights into the biochemical diversity of mulberry genotypes and highlight the significance of genetic factors in shaping these traits. Future research should aim to uncover the biochemical pathways underlying these traits and assess the role of environmental interactions in their modulation. Additionally, further studies are needed to determine whether the potential of low-performing genotypes can be enhanced through environmental or agricultural interventions. Ultimately, these findings demonstrate the value of integrating genotype selection with biochemical profiling to maximize the agricultural and industrial benefits of mulberry genotypes.

Analysis of the nutrient content in 21 mulberry genotypes showed considerable variation, as confirmed by statistical analysis (One-way ANOVA, p < 0.05) (Table 3). This diversity has noteworthy implications, impacting not only agricultural practices but also human nutrition and health. The concentration of aluminum ranged from 51.53 (‘44 MRK 01’) to 115.80 mg/kg (‘23 MRK 09’), with an average of 79.52 ± 15.13 mg/kg. Aluminum in small quantities may not have a direct nutritional role, but excessive levels can pose risks to human health, particularly in neural and renal functions44. Excessive aluminum can be toxic to plants, inhibiting root development and nutrient uptake, especially in acidic soils45. Boron levels were recorded between 15.15 (‘Şelale Karadut’) and 39.06 mg/kg (‘Yong Choen Choe’), with an average of 28.19 ± 6.35 mg/kg. Boron plays a vital role in bone health and metabolic activities, including magnesium and calcium utilization46. Boron is important for plants, as it supports cell wall formation and helps in reproductive processes such as pollen tube growth and seed development47. Calcium content ranged from 5733.05 (‘Şelale Karadut’) to 32525.52 mg/kg (‘44 MRK 01’), with an average of 14082.45 ± 9520.17 mg/kg. Calcium is essential for strong bones and teeth, as well as for muscle function and nerve signaling48. In plants, calcium is a structural element in cell walls and membranes, providing strength and influencing signal transduction and growth processes49. Carbon levels varied between 5.83 (‘Mersin Köy Hizmetleri Mordut’) and 10.64 mg/kg (‘Şelale Karadut’), with an average of 8.09 ± 1.47 mg/kg. Carbon is a structural element in organic compounds but does not directly contribute to nutrition as a standalone element. For plants, carbon is absorbed from CO2 during photosynthesis and is a fundamental building block of carbohydrates, proteins, and lipids50. Iron levels were found to range from 59.45 (‘Mersin Köy Hizmetleri Mordut’) to 101.99 mg/kg (‘Topu Beyaz-2 (24 − 03)’), with an average of 76.69 ± 11.93 mg/kg. Iron is critical for hemoglobin production and oxygen transport in the blood, preventing anemia51. Iron is a key component in chlorophyll synthesis in plants and is essential for their photosynthetic processes52. Potassium concentrations varied between 1428.94 (‘Kastamonu Beyaz’) and 3086.85 mg/kg (‘25 UZ 08’), with an average of 2145.60 ± 523.56 mg/kg. Potassium helps regulate blood pressure, fluid balance, and muscle contractions53,54. In plants, potassium is involved in enzyme activation, water regulation, and maintaining turgor pressure, contributing to overall plant vitality55. Magnesium levels ranged from 1251.68 (‘Şelale Karadut’) to 3660.91 mg/kg (‘Gümüşhacıköy Hortum’), with an average of 2283.22 ± 604.43 mg/kg. Magnesium supports energy production, nerve function, and bone health56. Magnesium in plants is vital for chlorophyll production and is a cofactor in many enzyme reactions that support growth and development57. Manganese concentrations were recorded between 11.48 (‘Kastamonu Beyaz’) and 28.17 mg/kg (‘25 UZ 08’), with an average of 15.99 ± 3.95 mg/kg. Manganese is essential for bone development, enzyme function, and antioxidant defense58. Manganese is involved in photosynthesis and respiration in plants, where it acts as a cofactor for several key enzymes59. Sodium levels varied between 142.71 (‘Kolik Dut (24 − 11)’) and 283.56 mg/kg (‘Topu Beyaz-2 (24 − 03)’), with an average of 193.24 ± 34.47 mg/kg. Sodium plays a key role in maintaining fluid balance and transmitting nerve signals60. While sodium is not required by most plants in large quantities, it can be beneficial for certain halophytic species and plays a role in osmoregulation and stress tolerance61. Nickel levels ranged from 0.52 (‘Hatay Dörtyol Mordut’) to 1.43 mg/kg (‘Gosho Erami’), with an average of 0.84 ± 0.25 mg/kg. In humans, nickel plays a role in certain metabolic processes, but excessive intake can lead to toxicity and pose significant health risks62. For plants, nickel is essential in small amounts, particularly for nitrogen metabolism, but excessive levels can negatively affect growth and development63. Phosphorus levels ranged from 1122.26 (‘Kastamonu Beyaz’) to 2036.66 mg/kg (‘Şelale Karadut’), with an average of 1545.45 ± 286.47 mg/kg. Phosphorus is crucial for bone health, energy production, and cellular repair64. In plants, phosphorus is an integral part of ATP, DNA, and RNA, and it plays a critical role in energy transfer, root development, and flowering65. Lead concentrations ranged between 0.16 (‘Yong Choen Choe’) and 0.48 mg/kg (‘23 MRK 09’), with an average of 0.33 ± 0.11 mg/kg. Lead has no known nutritional value and is toxic at any level, potentially causing severe health issues66. Lead is harmful to plants, as it can disrupt photosynthesis, inhibit root growth, and reduce overall plant vitality, particularly in high concentrations67. Sulfur levels varied between 281.52 (‘Ship Yeoung’) and 609.09 mg/kg (‘Topu Beyaz-2 (24 − 03)’), with an average of 429.03 ± 81.41 mg/kg. Sulfur is essential for protein synthesis and is a structural component of amino acids like cysteine and methionine68. Sulfur is required by plants for the synthesis of amino acids, coenzymes, and vitamins, influencing growth and resistance to stress69. Zinc concentrations ranged from 7.50 (‘Kastamonu Beyaz’) to 16.37 mg/kg (‘Topu Beyaz-2 (24 − 03)’), with an average of 10.94 ± 2.62 mg/kg. Zinc supports immune function, wound healing, and DNA synthesis70. Zinc in plants plays a critical role in enzyme activation, protein synthesis, and maintaining membrane stability, contributing to overall plant health71.

Lamiaa72 reported that among minerals, calcium content was 1493.22 mg/100 g, iron content was 27.06 mg/100 g, and zinc content was 2.18 mg/100 g. The magnesium, phosphorus, sodium, and potassium contents were 533.24, 370.91, 58.62, and 1239.07 mg/100 g, respectively. Adeduntan and Oyerinde73 detected that zinc levels in their samples ranged from 34.4 to 57.5 mg/kg, sodium from 1069 to 1526 mg/kg, manganese from 14.83 to 24.37 mg/kg, calcium from 944 to 1467 mg/kg, potassium from 1684 to 2170 mg/kg, iron from 129.70 to 238.00 mg/kg, and magnesium from 1450 to 2196 mg/kg. Our findings, in part, correspond to those obtained in a similar study conducted in Korea74. Moreover, Koyuncu et al.75 investigated the chemical characteristics of mulberry leaves from various genotypes and found that the leaves were abundant in sodium, calcium, and potassium, thereby supporting our results. The differences observed may be due to variations in the genetic makeup, environmental factors, and cultivation methods, which are known to influence the mineral content of plant tissues.

The nutrient content analysis of the 21 mulberry genotypes revealed considerable variation in the concentrations of essential elements, with notable differences observed in aluminum, boron, calcium, iron, and other key nutrients. From a human health perspective, these variations highlight the potential of mulberry leaves as a valuable source of bioactive compounds, particularly for antioxidant, mineral, and nutritional supplementation. Elements such as calcium, iron, potassium, and magnesium are critical for human health, contributing to bone strength, blood circulation, muscle function, and cellular metabolism. At the same time, the observed differences between genotypes suggest that mulberry leaves may offer varying nutritional benefits, depending on the specific genotype and growing conditions.

From a plant perspective, the nutrient levels also provide insights into the physiological requirements of mulberry trees, with elements like calcium, magnesium, and potassium playing essential roles in plant growth, development, and stress tolerance. These nutrients contribute to strong root systems, robust cell walls, and efficient photosynthesis. The data indicate that mulberry genotypes exhibit a diverse range of nutrient profiles, which may influence their adaptability to environmental conditions and overall health. Therefore, understanding these nutrient variations is crucial for optimizing both human health benefits and agricultural productivity.

The TUKEY statistical test revealed significant variations in all measured parameters of leaf morphology among mulberry genotypes (One-way ANOVA, p < 0.05) (Table 4).

Accordingly, leaf length ranged from 65.44 (‘Amasya Beyaz’) to 135.30 mm (‘44 BA 05’), with an average of 89.06 ± 24.99 mm. Leaf width varied between 45.34 (‘Amasya Beyaz’) and 98.76 mm (‘44 MRK 01’), with a mean value of 71.02 ± 16.34 mm. Petiole length was observed to range from 13.38 (‘Erzincan Karadut’) to 46.36 mm (‘44 BA 05’), with an average of 26.91 ± 12.43 mm. Petiole width was recorded between 0.48 (‘Yong Choen Choe’) and 2.60 mm (‘Ship Yeoung’), with a mean of 1.24 ± 0.87 mm.

In a comprehensive study conducted in Türkiye, the morphological traits of leaves exhibited significant variation, with leaf length ranging from 71.23 to 160.35 mm, leaf width spanning from 48.61 to 121.61 mm, petiole length varying between 16.75 and 46.92 mm, and petiole width recorded between 1.17 and 5.12 mm19. In another study conducted in Türkiye, leaf length ranged from 86.6 to 138.4 mm, leaf width from 58.9 to 118.8 mm, petiole length from 25.8 to 49.6 mm, and petiole thickness from 0.73 to 2.03 mm76. Similarly, research from India determined the combined length of the leaf and petiole reaching up to 178 mm, with leaf width measuring between 53 and 98 mm77. It was determined that in Iran, the leaf length ranged from 56.62 to 183.25 mm, the leaf width varied between 45.72 and 146.56 mm, and the petiole length changed between 19.55 and 58.56 mm78. Similar value ranges have also been reported in the study by Hosseini et al.79. These findings demonstrate a remarkable alignment with our results, highlighting the consistency of leaf morphological traits across diverse geographic regions and environmental conditions. The leaf morphology images of the 21 genotypes are presented in Fig. 2.

Correlation matrix analysis (CMA)

Correlation matrix analysis (CMA) is a method used to examine the relationships between variables. The Pearson correlation coefficient (r) measures the degree of linear relationship between two continuous variables, yielding a value between − 1 and + 1. A value of + 1 represents a perfect positive linear relationship, −1 indicates a perfect negative linear relationship, and 0 suggests the absence of a linear relationship. The Pearson correlation is calculated using a formula that incorporates the standard deviations and means of both variables80. The results are visualized in the form of a correlation matrix. This analysis is an effective method for understanding the relationships among multiple variables and is considered a powerful tool for linear relationships81,82. Simple correlations between the traits examined in the mulberry genotypes are presented in Fig. 3.

The strong correlation between total flavonoids and total phenolics (r = 0.66**) highlights the interconnected nature of these secondary metabolites, both of which are recognized for their antioxidant properties. Phenolics and flavonoids are crucial in combating oxidative stress, which is implicated in various chronic diseases, including cardiovascular diseases, cancer, and neurodegenerative disorders. The positive correlation suggests that enhancing one may proportionally increase the other, amplifying their collective health benefits.

Calcium’s significant correlations with boron (r = 0.60**), potassium (r = 0.45*), magnesium (r = 0.48*), and sodium (r = 0.47*) reflect its broad physiological relevance. Calcium is essential for bone health, muscle function, and nerve signaling. The correlation with magnesium is particularly noteworthy, as magnesium assists in calcium absorption and regulation, further supporting skeletal health. Potassium and sodium are critical for maintaining fluid balance and blood pressure, highlighting a possible synergistic role of these elements in cardiovascular health.

Iron exhibits strong correlations with aluminum (r = 0.81**), sodium (r = 0.62**), and lead (r = 0.68**). Iron is a vital component of hemoglobin and is necessary for oxygen transport in the body. However, the correlation with lead raises potential concerns, as lead is a toxic heavy metal that can interfere with iron absorption and utilization, exacerbating conditions like anemia. The correlation with sodium could indicate a physiological relationship where iron metabolism is influenced by ionic homeostasis.

Potassium shows significant correlations with carbon (r = 0.52*), manganese (r = 0.57**), sodium (r = 0.52*), nickel (r = 0.68**), phosphorus (r = 0.62**), and zinc (r = 0.69**). Potassium is essential for maintaining electrolyte balance and reducing hypertension risk. Its correlation with zinc, a critical element for immune function and wound healing, suggests a potential interplay between these elements in supporting cellular processes. The relationship with phosphorus highlights potassium’s role in energy metabolism, while its correlation with manganese suggests a connection to enzymatic activity important for nutrient metabolism.

Magnesium’s correlations with sodium (r = 0.53*) and sulfur (r = 0.85**) emphasize its critical role in metabolic health. Magnesium is involved in over 300 enzymatic reactions, including those related to energy production and DNA repair. Its strong correlation with sulfur underscores their joint participation in antioxidant defense systems, particularly through the synthesis of sulfur-containing compounds like glutathione, a key cellular antioxidant.

Phosphorus and zinc (r = 0.54*) exhibit a moderate correlation, pointing to their combined roles in cellular metabolism. Phosphorus is a core component of ATP, the primary energy carrier in cells, while zinc supports enzymatic activity and structural stability in biomolecules. Together, they contribute to processes essential for growth, repair, and immune defense.

Leaf length correlates with manganese (r = 0.49*), zinc (r = 0.47*), leaf width (r = 0.60**), and petiole length (r = 0.60**). Morphological traits such as these may indirectly relate to nutrient density in plants, as larger leaves might indicate an increased surface area for photosynthesis and metabolite synthesis. Zinc and manganese, critical for enzymatic and structural roles in plants, may enhance the nutritional quality of edible plant tissues, indirectly benefiting human health.

Petiole width correlates with total phenolics (r = 0.56**) and leaf width (r = 0.52*). Wider petioles may be associated with increased phenolic content, suggesting a potential relationship between plant morphology and the accumulation of health-promoting compounds. Total phenolics, in particular, are known for their protective effects against oxidative damage in the human body.

The findings obtained from the Pearson correlation are consistent with the results reported in previous studies conducted in China43and India77. The data obtained reveal the presence of similar relationships across different geographical regions, demonstrating that our observations are globally valid and consistent.

Overall, these correlations highlight the intricate relationships between biochemical, mineral, and morphological traits that influence the nutritional and medicinal value of plants. From a human health perspective, elements such as calcium, iron, potassium, magnesium, phosphorus, and zinc, as well as secondary metabolites like phenolics and flavonoids, play critical roles in maintaining physiological balance and preventing disease. The potential interplay between toxic elements like lead and essential nutrients warrants further investigation to ensure optimal health outcomes. These findings emphasize the importance of understanding plant-based nutrient profiles to enhance dietary quality and health benefits.

Multiple regression analysis (MRA)

Multiple regression analysis (MRA) was conducted using the stepwise method within the framework of linear regression analysis, as described by Draper and Smith83. Briefly, this statistical approach allows for the identification of the most significant predictor variables by systematically adding or removing independent variables based on predefined criteria, such as their p-values. The stepwise method begins by including the variable with the highest correlation to the dependent variable and then progressively evaluates additional variables for inclusion or exclusion based on their incremental contribution to the model. This iterative process ensures that only statistically significant predictors are retained in the final model, optimizing the balance between explanatory power and simplicity. Before the analysis, the dataset was assessed for multicollinearity using variance inflation factor (VIF) values, and variables with high collinearity were excluded to enhance the robustness of the results. The analysis was performed under the assumption that the residuals were normally distributed, homoscedastic, and independent. The final regression model provides a comprehensive understanding of the relationship between the dependent variable and the most influential predictors, enabling reliable and interpretable insights into the data84,85.

Initially, after calculating the simple correlation coefficients, total phenolics, total flavonoids, calcium, iron, and zinc were considered as dependent variables, and the direct and indirect effects of the independent variables on these key traits were analyzed. The MRA results indicated that total phenolics were associated with two traits, total flavonoids with one trait, calcium with five traits, iron with three traits, and zinc with two traits (Table 5).

The multiple regression analysis conducted reveals the complex interactions between biochemical and mineral components in plants. Positive correlations were found between phenolic compounds, flavonoids, and manganese (β = 0.74, p < 0.00; β = 0.38, p < 0.03), indicating that manganese may influence the biosynthesis of both phenolic compounds and flavonoids. Manganese plays a significant role in photosynthesis and enzymatic processes in plants, thereby supporting the production of these compounds. A strong correlation between flavonoids and manganese (β = 0.75, p < 0.00) further emphasizes manganese’s role in secondary metabolite production in plants.

Calcium showed positive correlations with boron (β = 0.47, p < 0.00), magnesium (β = 0.35, p < 0.02), and potassium (β = 0.68, p < 0.00), while displaying negative correlations with phosphorus (β=–0.49, p < 0.01) and iron (β=–0.30, p < 0.04). These findings highlight calcium’s role in cell wall stability and metabolic processes, while also emphasizing the competitive interactions between phosphorus and iron uptake.

Iron exhibited a positive correlation with aluminum (β = 0.76, p < 0.00) and sodium (β = 0.35, p < 0.00), but a negative correlation with phosphorus (β=–0.44, p < 0.00). Aluminum and sodium may facilitate the transport of iron, while elevated phosphorus levels seem to inhibit its uptake. Zinc showed positive correlations with potassium (β = 0.65, p < 0.00) and sulfur (β = 0.44, p < 0.00), reflecting its dependency on these minerals for physiological functions. These results suggest that zinc is reliant on potassium and sulfur for its physiological roles, and these minerals positively affect plant health and stress tolerance. The bold values are supported by the statistically significant correlations from the correlation matrix analysis.

Overall, the relationships observed in this study highlight the interconnectedness of biochemical and mineral components in plants, emphasizing their significance for both plant health and human nutrition.

To our knowledge, there is no study based on multiple regression analysis where similar analyses are used together, therefore the results obtained are interpreted and discussed independently by considering each relationship in detail. Although the multiple regression model provides a comprehensive perspective in understanding how various characteristics are related to each other, the lack of comparable studies made it necessary to analyze the results separately. Discussing each relationship independently provided a clear understanding of the individual effects and emphasized the importance of these relationships in the context of the study.

Principal component analysis (PCA)

Principal component analysis (PCA) was performed using the Varimax rotation method with Kaiser Normalization. Varimax rotation is an orthogonal technique aimed at simplifying and enhancing the interpretability of the factor structure by maximizing the variance of squared loadings of a factor on all variables. This method allows each variable to have a strong correlation with one or more components while minimizing correlations between the components themselves85,86. Kaiser Normalization was applied during the rotation process to standardize the variance of the loadings, ensuring that the sum of squared loadings for each component is equal, thus preventing any single component from disproportionately influencing the results and allowing for a more balanced representation of the data87. Additionally, the analysis was conducted by extracting components with eigenvalues greater than 1, a common criterion in PCA, to ensure that only components that explain a substantial portion of the variance were retained. This approach effectively captures the most meaningful factors, leading to a clearer understanding of the underlying structure of the data87. In this context, the first 7 principal components with an eigenvalue greater than 1 were considered in the study, accounting for 85.37% of the total variation (Table 6).

PC1 represents 26.85% of the total variation, with the highest contributions coming from potassium (0.35), sodium (0.32), manganese (0.30), zinc (0.30), aluminum (0.26), and leaf length (0.26). This indicates that these elements and traits play a significant role in explaining the overall variability captured by the first principal component, highlighting their prominence in the dataset. The high loadings of potassium, sodium, and manganese suggest that these minerals, along with the leaf length, are closely associated with the major variation in the dataset.

PC2 accounts for 17.7% of the total variation, with the strongest contributions from total phenolics (0.38), total flavonoids (0.33), leaf width (0.33), petiole width (0.33), and phosphorus (0.26). The prominence of phenolic compounds and flavonoids in PC2 reflects the importance of these biochemical components in the variability captured by the second principal component. Furthermore, the association of leaf and petiole dimensions with these compounds indicates potential links between plant structure and biochemical content, reinforcing the significance of plant morphological traits in explaining variance.

PC3 represents 11.5% of the total variation, with the highest contributions from lead (0.51), iron (0.42), and aluminum (0.40). These elements are strongly associated with the third principal component, suggesting that they are key factors in explaining this portion of the variation. The high contribution of lead, in particular, indicates that trace metals play a crucial role in the variation captured by PC3.

Together, the first three principal components account for 56.05% of the total variation, indicating that these components capture the majority of the variability present in the dataset. Furthermore, the analysis revealed that the first three principal components are statistically significant at the p < 0.01 level, suggesting that they reliably represent the underlying structure of the data. This result underscores the importance of these components in explaining the complex relationships between the variables in the study, providing valuable insights into the interactions among mineral and biochemical traits in plants.

PCA analysis has been used to evaluate mulberry genetic resources in different countries before and our findings are partially similar to the findings of researchers77,78,79,88. The observed differences are likely due to ecological variations and the diversity of genotypes studied89.

Principal component scores are numerical values that represent the projection of each observation (such as an individual, genotype, or sample) onto the newly defined axes (principal components) generated through PCA. These components are linear combinations of the original variables and are constructed to capture the maximum variance present in the dataset. The scores indicate the relative position of each observation along each component, thereby summarizing its multivariate profile in a reduced-dimensional space. Because the first few principal components usually account for the majority of the total variance, principal component scores are especially useful for visualizing complex data structures in two or three dimensions. They provide insights into patterns of similarity or divergence among observations, facilitating the identification of clusters, outliers, or gradients of variation. These scores are often used in conjunction with biplots to interpret both the relationships between variables and the distribution of observations across principal component axes. The interpretability and efficiency of principal component scores make them indispensable tools in multivariate statistical analysis, particularly in studies of phenotypic diversity, classification, and selection. They provide a compact, orthogonal representation of multidimensional data that enhances the detection of structure and supports further exploratory or inferential analyses90,91.

Table 7 presents the principal component (PC) scores and a composite performance index for twenty-one mulberry genotypes, derived from seven principal components. These scores encapsulate the multivariate trait architecture of each genotype, enabling a synthetic evaluation of their overall performance based on the combined influence of the measured variables.

The genotypes with the highest composite scores—‘Topu Beyaz-2 (24 − 03)’ (1.64), ‘25 UZ 08’ (1.45), and ‘23 MRK 09’ (1.26)— emerge as top performers. These accessions consistently exhibit strong positive loadings, particularly along the first and second principal components (PC1 and PC2), suggesting superior multivariate profiles. Their positioning at the upper end of the composite scale implies that these genotypes possess a favorable combination of traits contributing cumulatively to their agronomic or nutritional potential. High PC1 scores in these genotypes reflect the coordinated expression of the dominant variables in the analysis, while positive contributions from subsequent PCs reinforce their multi-dimensional strength.

In contrast, genotypes such as ‘44 MRK 01’ (−1.00), ‘Şelale Karadut’ (−1.08), and ‘Mersin Köy Hizmetleri Mordut’ (−1.10) occupy the lower end of the composite score distribution. These negative scores indicate relatively weaker overall performance across the evaluated trait space. Their negative PC1 and lower PC2–PC3 scores suggest deficiencies in multiple trait dimensions. However, this does not necessarily imply inferiority in all aspects—some of these genotypes may still harbor unique or context-dependent advantages, such as stress resilience or adaptation to specific environments.

Genotypes with mid-range composite scores—particularly ‘Ayaş Böğürtlen Bağı’ (− 0.02), ‘Hatay Dörtyol Mordut’ (− 0.21), and ‘Gosho Erami’ (− 0.30)—represent phenotypically balanced profiles. These accessions are positioned near the centroid of the multivariate space, reflecting moderate expression across the principal components without extreme dominance or deficiency in any specific trait dimension. Their intermediate placement suggests average or stable performance, making them potentially valuable for maintaining genetic diversity and contributing to breeding strategies focused on trait stability and environmental adaptability. Although not ranked among the top performers, such genotypes may play a complementary role in hybridization programs where trait buffering and consistency are prioritized.

The consistent influence of PC1 in shaping the composite scores underscores its central role in defining genotype differentiation. Genotypes positioned positively on PC1 also tend to rank higher overall, suggesting that the traits heavily loaded on PC1 serve as key discriminators within this mulberry population. The contributions of PC2 and PC3 to performance stratification further confirm the multidimensional nature of trait variation and provide deeper resolution in distinguishing genotypic strengths and weaknesses.

Overall, the multivariate approach used to generate Table 7 effectively identifies elite genotypes and highlights the phenotypic spectrum within the evaluated germplasm. By integrating composite trait performance, this analysis supports a holistic and data-driven framework for genotype selection in mulberry improvement programs—enhancing efforts in conservation, breeding, and the development of nutritionally or functionally superior cultivars.

A PCA biplot is a graphical representation used to interpret the results of PCA. It combines both the scores of the samples and the loadings of the variables in a two-dimensional plot, allowing for a comprehensive visualization of the relationships among samples and variables. The axes of the biplot correspond to the first two principal components, which explain the majority of the variation in the dataset. Sample points are displayed as markers, and variables are represented as vectors, where the direction and length of the vectors indicate their contribution to the principal components. Longer vectors suggest stronger contributions, while the angle between vectors reflects the correlation between variables92. Samples positioned closer to a variable vector are more strongly associated with that variable. PCA biplots are particularly valuable for identifying clusters, trends, and patterns in multidimensional datasets, making them a widely used tool in exploratory data analysis and interpretation. Additionally, advanced methodologies, such as nonlinear PCA using auto-associative neural networks, have been developed to capture more complex patterns and relationships in datasets93. The PC1/PC2 distribution biplot of the studied mulberry genotypes and variables is visualized in Fig. 4. According to the analysis, PC1 (26.85%) and PC2 (17.70%) together account for 44.55% of the total variation. The 21 variables were distributed across three regions of the biplot, while the 21 genotypes were spread across four regions.

In cluster 1, the variable petiole width was associated with the genotypes ‘Şelale Karadut’, ‘44 MRK 01’, ‘Ship Yeoung’, and ‘Mersin Köy Hizmetleri Mordut’, indicating a shared characteristic likely driven by this morphological trait.

Cluster 2 included the genotypes ‘Gosho Erami’, ‘44 BA 05’, and ‘Ayaş Böğürtlen Bağı’, which were closely associated with total antioxidant activity, total phenolics, total flavonoids, carbon, potassium, manganese, nickel, phosphorus, zinc, leaf length, leaf width, and petiole length. This grouping highlights the biochemical and morphological similarities among these genotypes, particularly their high antioxidant content and related traits.

Cluster 3 encompassed the genotypes ‘Amasya Beyaz’, ‘Angut-009’, ‘Arapgir-0012’, ‘Erzincan Karadut’, ‘Hatay Dörtyol Mordut’, ‘Kastamonu Beyaz’, ‘Kokusa 27’, ‘Kolik Dut (24 − 11)’, and ‘Yong Choen Choe’. The absence of significant association with specific variables in this group suggests a broader diversity in their biochemical and morphological profiles, potentially reflecting local adaptations or genetic variability.

Finally, cluster 4 comprised the genotypes ‘23 MRK 09’, ‘25 UZ 08’, ‘Gümüşhacıköy Hortum’, ‘Ichinose’, and ‘Topu Beyaz-2 (24 − 03)’, which were associated with aluminum, boron, calcium, iron, magnesium, sodium, lead, and sulfur. This cluster suggests a strong link between these genotypes and soil nutrient uptake or environmental conditions influencing elemental composition.

The fact that the total phenolics, potassium, and sodium variables are outside the 95% confidence ellipse on the biplot may indicate that the relationships of these variables with the genotypes they are associated with are lower compared to others, or it may suggest a potential superiority of these variables for these genotypes. In other words, these variables could represent a more distinct difference in the biochemical and nutritional content characteristics of these genotypes. In a biplot, the 95% Confidence ellipse represents an area that encompasses the majority of the data, indicating that a given variable is expected to fall within this region. Data points outside the ellipse may suggest that they differ from the others or possess an outlier value. Therefore, data sets outside the 95% Confidence ellipse should be further investigated, warranting separate studies for a more detailed analysis94.

These results demonstrate clear patterns of variability among the genotypes based on both morphological and biochemical traits. The distinct clustering highlights the potential influence of genetic background and environmental factors, as well as the interplay between morphology, biochemistry, and nutrient uptake. Such findings provide valuable insights for breeding programs and the selection of genotypes with specific desirable traits for cultivation or further research.

Heat map analysis (HMA)

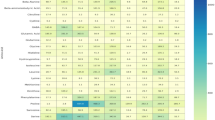

The Ward method is a hierarchical clustering technique widely used in data analysis to group similar objects or observations95. This method is particularly effective in identifying natural groupings within the data by minimizing the total within-cluster variance at each step. When combined with heat map analysis (HMA), the Ward method helps visualize patterns and relationships among variables or genotypes. HMA represents the values of variables through a color-coded matrix, which facilitates the detection of trends, correlations, or clusters within the data. Euclidean distance coefficients are used to measure the straight-line distance between data points, and the Ward method ensures that clusters are formed based on the overall similarity between the data96. The combination of the Ward method with heat map analysis based on Euclidean distances allows for a comprehensive understanding of the data structure, revealing hidden patterns that may not be detected through standard analyses97. Visualization of clustering patterns of mulberry genotypes and variables using a heat map is shown in Fig. 5.

The variables were initially divided into two groups, A and B. Subsequently, each group was further subdivided into two subgroups: A1 and A2, and B1 and B2. The A1 subgroup includes total antioxidant activity, aluminum, iron, leaf length, leaf width, sodium, sulfur, total phenolics, boron, petiole length, total flavonoids, carbon, zinc, and manganese, while the A2 subgroup includes nickel, petiole width, and lead. The B1 subgroup contains only calcium, whereas the B2 subgroup consists of potassium, magnesium, and phosphorus.

The genotypes were similarly divided into two groups, C and D, and each group was further divided into two subgroups: C1 and C2, and D1 and D2. The C1 subgroup includes the genotypes ‘Mersin Köy Hizmetleri Mordut’, ‘Gümüşhacıköy Hortum’, and ‘Erzincan Karadut’, while the C2 subgroup includes ‘Ship Yeoung’, ‘Şelale Karadut’, and ‘44 MRK 01’. The D1 subgroup consists of ‘44 BA 05’ and ‘25 UZ 08’, while the D2 subgroup contains ‘Kolik Dut (24 − 11)’, ‘Hatay Dörtyol Mordut’, ‘Kastamonu Beyaz’, ‘Amasya Beyaz’, ‘Kokusa 27’, ‘Gosho Erami’, ‘Ayaş Böğürtlen Bağı’, ‘Yong Choen Choe’, ‘Ichinose’, ‘Arapgir-0012’, ‘Angut-009’, ‘Topu Beyaz-2 (24 − 03)’, and ‘23 MRK 09’.

Grouping the variables into categories A and B under the same ecological conditions for all genotypes highlights two critical aspects of plant physiology: Group A focuses on biochemical health and stress responses, while Group B emphasizes the content of macronutrients. The A1 subgroup, containing antioxidants, phenolic compounds, and essential minerals like zinc and manganese, emphasizes factors related to the plant’s defense mechanisms and its response to environmental stress. On the other hand, the A2 subgroup, which includes nickel, petiole width, and lead, suggests a focus on potential stressors like heavy metals and how these plants might tolerate or accumulate such elements. The B group, with its focus on essential macronutrients like calcium, potassium, magnesium, and phosphorus, reveals how nutrient distribution affects plant growth, metabolism, and productivity.

The differentiation of genotypes into subgroups C1 and C2, and D1 and D2, provides further insight into how these genotypes perform under similar ecological conditions. The genotypes in the C1 subgroup such as ‘Mersin Köy Hizmetleri Mordut’, ‘Gümüşhacıköy Hortum’ and ‘Erzincan Black Mulberry’ and the C2 subgroup including the genotypes ‘Ship Yeoung’, ‘Şelale Black Mulberry’ and ‘44 MRK 01’ show positive responses in plant growth and stress responses. D1 and D2 subgroups, which have more genotype diversity, better reflect diversity in terms of genetic resources and adaptability under the same ecological conditions. D2, in particular, with its broader set of genotypes, may provide a better perspective on variability in stress resilience and overall performance.

As a result, heat map analysis of these variables and genotypes reveals how biochemical, physiological, and nutritional factors interact within the same ecological conditions. This analysis may guide future breeding programs of these genotypes.

Multivariate statistical analysis methods serve as powerful tools for the comprehensive evaluation of plant genetic resources in terms of morphological, phytochemical, and biochemical attributes. These approaches are frequently employed to reveal genetic variation, classify genotypes, and identify superior materials. Notably, such analyses have been effectively applied in studies on various plant species. For instance, they have been used to assess seed oil fatty acid profiles and bioactive compound content in Rosa canina genotypes98, to classify Equisetum arvense L. ecotypes based on silicon content, phytochemical composition, and morphological traits99, and to determine the agromorphological characteristics, metabolite profiles, and anticancer potential of Tribulus terrestris L. populations100. Additionally, chemometric analyses were successfully employed to investigate the essential oil composition, phenolic compounds, and antibacterial activity of Grammosciadium platycarpum101. These studies demonstrate the value of multivariate analyses in elucidating genetic diversity and interpreting biological characteristics across a wide range of plant species.

Conclusions

This study reveals significant genetic diversity among mulberry genotypes in Türkiye, with notable variations in biochemical composition, antioxidant capacity, nutrient content, and morphology. The genotypes ‘Gosho Erami’ and ‘Mersin Köy Hizmetleri Mordut’ stood out for their superior antioxidant and phenolic profiles, making them ideal candidates for the development of functional foods, dietary supplements, and pharmaceutical formulations with health-promoting properties. In contrast, ‘Hatay Dörtyol Mordut’ showed lower bioactive content, suggesting a need for targeted agricultural improvements to enhance its quality traits.

Multivariate analyses (PCA and HMA) highlighted strong correlations among biochemical, mineral, and morphological traits, emphasizing the value of integrated selection approaches in breeding programs. Key nutrients like calcium, potassium, and zinc were identified as critical not only for plant development but also for addressing human nutritional deficiencies, which can be particularly valuable for the design of fortified food products. Meanwhile, the presence of toxic elements (e.g., lead) necessitates further investigation and mitigation strategies, especially for safe food and pharmaceutical use.

Genotypes ‘25 UZ 08’, ‘Ichinose’, and ‘44 BA 05’ exhibited the highest overall performance across multiple traits, making them promising candidates for commercial cultivation and value-added product development. On the other hand, genotypes like ‘44 MRK 01’, ‘Ship Yeoung’, and ‘Şelale Karadut’ ranked lowest, indicating limited immediate applicability but the potential for improvement through breeding or biotechnological interventions.

These findings provide actionable insights for mulberry breeding, germplasm conservation, and cultivar selection, directly supporting the development of ecologically adapted and industry-oriented varieties. Future research should explore the molecular mechanisms underlying key traits and develop adaptive strategies to enhance mulberry cultivation under varying environmental conditions. Integrating biochemical profiling with advanced breeding techniques holds strong potential to maximize the crop’s economic, ecological, nutritional, and pharmacological value.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the co-corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

References

Ma, G., Chai, X., Hou, G., Zhao, F. & Meng, Q. Phytochemistry, bioactivities and future prospects of mulberry leaves: A review. Food Chem. 372, 131335. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.131335 (2022).

Hashemi, S. & Khadivi, A. Morphological and Pomological characteristics of white mulberry (Morus alba L.) accessions. Sci. Hort. 259, 108827. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scienta.2019.108827 (2020).

Benavides, J. E., Lachaux, M. & Fuentes, M. Efecto de La Aplicación de estiércol de Cabra En El Suelo sobre La Calidad y producción de Biomasa de Morera (Morus sp). Árboles Y Arbustos Forrajeros En América Cent. 2, 495–514 (1994).

Yigit, D., Akar, F., Baydas, E. & Buyukyildiz, M. Elemental composition of various mulberry species. Asian J. Chem. 22 (5), 3554–3560 (2010).

Chan, E. W. C., Phui-Yan, L. Y. E. & Siu-Kuin, W. O. N. G. Phytochemistry, pharmacology, and clinical trials of Morus alba. Chin. J. Nat. Med. 14 (1), 17–30. https://doi.org/10.3724/SP.J.1009.2016.00017 (2016).

Arabshahi-Delouee, S. & Urooj, A. Antioxidant properties of various solvent extracts of mulberry (Morus indica L.) leaves. Food Chem. 102 (4), 1233–1240. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2006.07.013 (2007).

Gryn-Rynko, A., Bazylak, G. & Olszewska-Slonina, D. New potential phytotherapeutics obtained from white mulberry (Morus alba L.) leaves. Biomed. Pharmacother. 84, 628–636. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopha.2016.09.081 (2016).

Hu, X. Q. et al. Quantitative determination of 1-deoxynojirimycin in mulberry leaves from 132 varieties. Ind. Crops Prod. 49, 782–784. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indcrop.2013.06.030 (2013).

Vichasilp, C. et al. Development of high 1-deoxynojirimycin (DNJ) content mulberry tea and use of response surface methodology to optimize tea-making conditions for highest DNJ extraction. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 45 (2), 226–232. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lwt.2011.09.008 (2012).

Butt, M. S., Nazir, A., Sultan, M. T. & Schroën, K. Morus alba L. nature’s functional tonic. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 19 (10), 505–512. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tifs.2008.06.002 (2008).

Srivastava, S., Kapoor, R., Thathola, A. & Srivastava, R. P. Nutritional quality of leaves of some genotypes of mulberry (Morus alba). Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 57 (5–6), 305–313. https://doi.org/10.1080/09637480600801837 (2006).

Devi, B., Sharma, N., Kumar, D. & Jeet, K. Morus alba linn: A phytopharmacological review. Int. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 5 (2), 14–18 (2013).

Katsube, T. et al. Antioxidant flavonol glycosides in mulberry (Morus alba L.) leaves isolated based on LDL antioxidant activity. Food Chem. 97 (1), 25–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2005.03.019 (2006).

Jeszka-Skowron, M. et al. Mulberry leaf extract intake reduces hyperglycaemia in streptozotocin (STZ)-induced diabetic rats fed high-fat diet. J. Funct. Foods. 8, 9–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jff.2014.02.018 (2014).

Yang, N. C., Jhou, K. Y. & Tseng, C. Y. Antihypertensive effect of mulberry leaf aqueous extract containing γ-aminobutyric acid in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Food Chem. 132 (4), 1796–1801. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2011.11.143 (2012).

Harauma, A. et al. Mulberry leaf powder prevents atherosclerosis in Apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 358 (3), 751–756. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.04.170 (2007).

Park, E., Lee, S. M., Lee, Kim, J. H. & J., & Anti-inflammatory activity of mulberry leaf extract through Inhibition of NF-κB. J. Funct. Foods. 5 (1), 178–186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jff.2012.10.002 (2013).

Hu, X. Q. et al. Metabolic effect of 1-deoxynojirimycin from mulberry leaves on db/db diabetic mice using liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry based metabolomics. J. Agric. Food Chem. 65 (23), 4658–4667. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jafc.7b01766 (2017).

Çöçen, E. Phenological, pomological and morphological characterization of mulberry genotypes in Malatya mulberry genetic resources. Master’s thesis. Erciyes University, Graduate School of Natural and Applied Sciences. Kayseri, Türkiye. (2017).

Hannachi, H. et al. Chemical profiles and antioxidant activities of leaf, pulp, and stone of cultivated and wild Olive trees (Olea europaea L). Int. J. Fruit Sci. 20 (3), 350–370. https://doi.org/10.1080/15538362.2019.1644574 (2020).

Sharma, O. P. & Bhat, T. K. DPPH antioxidant assay revisited. Food Chem. 113 (4), 1202–1205. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2008.08.008 (2009).

Dawidowicz, A. L., Wianowska, D. & Olszowy, M. On practical problems in estimation of antioxidant activity of compounds by DPPH method (Problems in Estimation of antioxidant activity). Food Chem. 131 (3), 1037–1043. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2011.09.067 (2012).

Bektaş, B., Özer, S. & Karaman, S. Investigation of biochemical, textural, bioactive and sensory properties of muffin cakes produced with the addition of cranberry (Cornus mas L.) fruit at different concentrations. Harran J. Agricultural Food Sci. 27 (3), 415–423. https://doi.org/10.29050/harranziraat.1187931 (2023).

Lamuela-Raventós, R. M. Folin–Ciocalteu method for the measurement of total phenolic content and antioxidant capacity. Measurement of antioxidant activity & capacity: recent trends and applications, 107–115. (2018). https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119135388.ch6

Demir, B. et al. Biochemical composition and shape-dimensional traits of rosehip genotypes. Folia Horticulturae. 33 (2), 293–308. https://doi.org/10.2478/fhort-2021-0022 (2021).

Milošević, T., Moreno, M. Á., Milošević, N. & Milinković, M. Regulation of yield, fruit size, and leaf mineral nutrients of the ‘šumadinka’sour cherry cultivar with help of rootstocks. J. Plant Growth Regul. 42 (9), 5587–5599. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00344-023-10939-8 (2023).

Miller, R. O. Reference methods for plant analysis, pp 57–63. (1998).

Çoban, F. et al. Antioxidant activity and mineral nutrient composition of Polygonum cognatum-a potential wild edible plant. Indian J. Traditional Knowl. 20 (1), 221–229 (2021).

Kızılkaya, D. et al. Investigation of biochemical and molecular changes in wheat genotypes under alkaline salt stress. Acta Physiol. Plant. 46 (12), 115. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11738-024-03742-9 (2024).

JMP®. https://www.jmp.com/en_us/home.html. (Accessed 28 November 2024).

Ahmed, I. A. M., Özcan, M. M., AlJuhaimi, F. & Albakry, Z. The monitoring of accumulations of elements in apple, pear, and quince fruit parts. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12011-024-04223-3 (2024).

OriginLab®. https://www.originlab.com/. (Accessed 28 November 2024).

Efe, E., Bek, Y. & Şahin, M. Statistical Methods II. Republic of Türkiye Kahramanmaraş Sütçü, 1–214 (İmam University Rectorate, 2000).

Norusis, M. J. SPSS/PC Advanced Statistics (SPSS Inc., 1998).

SPSS, I. SPSS Statistics Base 17.0 User’s Guide, 210 (SPSS Inc., 2009).

Kaurinovic, B. & Vastag, D. Flavonoids and Phenolic Acids as Potential Natural Antioxidants, pp. 1–20 (IntechOpen, 2019).

Dumanović, J., Nepovimova, E., Natić, M., Kuča, K. & Jaćević, V. The significance of reactive oxygen species and antioxidant defense system in plants: A concise overview. Front. Plant Sci. 11, 552969. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2020.552969 (2021).

Serio, G. et al. Comparative profiling of secondary metabolites and antioxidant properties of twelve Morus varieties: insights into the diversity of M. alba and M. nigra grown in Sicily. Food Bioscience. 61, 104782. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fbio.2024.104782 (2024).

Jimenez-Garcia, S. N. et al. Functional properties and quality characteristics of bioactive compounds in berries: biochemistry, biotechnology, and genomics. Food Res. Int. 54 (1), 1195–1207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodres.2012.11.004 (2013).

Hao, J. Y. et al. Effect of different planting areas on the chemical compositions and hypoglycemic and antioxidant activities of mulberry leaf extracts in Southern China. PloS One. 13 (6), e0198072. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0198072 (2018).

Zhishen, J., Mengcheng, T. & Jianming, W. The determination of flavonoid contents in mulberry and their scavenging effects on superoxide radicals. Food Chem. 64 (4), 555–559. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0308-8146(98)00102-2 (1999).

Radojković, M., Zeković, Z., Vidovic, S., Kočar, D. & Mašković, P. Free radical scavenging activity and total phenolic and flavonoid contents of mulberry (Morus spp. L. Moraceae) Extracts. https://doi.org/10.2298/HEMIND111111002R (2012).

Yu, Y. et al. Nutritional and functional components of mulberry leaves from different varieties: evaluation of their potential as food materials. Int. J. Food Prop. 21 (1), 1495–1507. https://doi.org/10.1080/10942912.2018.1489833 (2018).

Nieboer, E., Gibson, B. L., Oxman, A. D. & Kramer, J. R. Health effects of aluminum: A critical review with emphasis on aluminum in drinking water. Environ. Reviews. 3 (1), 29–81. https://doi.org/10.1139/a95-002 (1995).

Sade, H. et al. Toxicity and tolerance of aluminum in plants: tailoring plants to suit to acid soils. Biometals 29, 187–210. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10534-016-9910-z (2016).

Khaliq, H., Juming, Z. & Ke-Mei, P. The physiological role of boron on health. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 186, 31–51. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12011-018-1284-3 (2018).

Day, S. & Aasim, M. Role of Boron in growth and development of plant: deficiency and toxicity perspective. Plant. Micronutrients: Defic. Toxic. Manage. 435–453. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-49856-6_19 (2020).

Pravina, P., Sayaji, D. & Avinash, M. Calcium and its role in human body. Int. J. Res. Pharm. Biomedical Sci. 4 (2), 659–668 (2013).

Wolf, S. Cell wall signaling in plant development and defense. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 73 (1), 323–353. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-arplant-102820-095312 (2022).

Anastassiadis, S. G. Carbon sources for biomass, food, fossils, biofuels and biotechnology-review Article. World J. Biology Biotechnol. 1 (1), 1–32. https://doi.org/10.33865/wjb.001.01.0002 (2016).

Gupta, C. P. Role of iron (Fe) in body. IOSR J. Appl. Chem. 7 (11), 38–46 (2014).

Rout, G. R. & Sahoo, S. Role of iron in plant growth and metabolism. Reviews Agricultural Sci. 3, 1–24. https://doi.org/10.7831/ras.3.1 (2015).

Fenn, W. O. & Cobb, D. M. The potassium equilibrium in muscle. J. Gen. Physiol. 17 (5), 629. https://doi.org/10.1085/jgp.17.5.629 (1934).

Haddy, F. J., Vanhoutte, P. M. & Feletou, M. Role of potassium in regulating blood flow and blood pressure. Am. J. Physiology-Regulatory Integr. Comp. Physiol. 290 (3), R546–R552. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpregu.00491.2005 (2006).

Pandey, G. K. & Mahiwal, S. Role of potassium in plants (Vol. 49). Cham, Switzerland: Springer. (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-45953-6

Faryadi, Q. The magnificent effect of magnesium to human health: a critical review. Int. J. Appl. 2 (3), 118–126 (2012).

Guo, W., Nazim, H., Liang, Z. & Yang, D. Magnesium deficiency in plants: an urgent problem. Crop J. 4 (2), 83–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cj.2015.11.003 (2016).

Erikson, K. M. & Aschner, M. Manganese: its role in disease and health. Met. Ions Life Sci. 19 (1), 253–266 (2019).

Schmidt, S. B. & Husted, S. The biochemical properties of manganese in plants. Plants 8 (10), 381. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants8100381 (2019).

Pohl, H. R., Wheeler, J. S. & Murray, H. E. Sodium and potassium in health and disease. Interrelations between Essent. Metal Ions Hum. Dis. 29–47. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-7500-8_2 (2013).

Arif, Y., Singh, P., Siddiqui, H., Bajguz, A. & Hayat, S. Salinity induced physiological and biochemical changes in plants: an omic approach towards salt stress tolerance. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 156, 64–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plaphy.2020.08.042 (2020).

Zambelli, B. & Ciurli, S. Nickel and human health. Interrelations between essential metal ions and human diseases, 321–357. (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-7500-8_10

Yusuf, M., Fariduddin, Q., Hayat, S. & Ahmad, A. Nickel: an overview of uptake, essentiality and toxicity in plants. Bull. Environ Contam. Toxicol. 86, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00128-010-0171-1 (2011).

Serna, J. & Bergwitz, C. Importance of dietary phosphorus for bone metabolism and healthy aging. Nutrients 12 (10), 3001. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12103001 (2020).

Fathi, A. & Mehdiniya Afra, J. Plant growth and development in relation to phosphorus: A review. Bulletin of the university of agricultural sciences & veterinary medicine Cluj-Napoca. Agriculture 80 (1). https://doi.org/10.15835/buasvmcn-agr:2022.0012 (2023).

Ara, A. & Usmani, J. A. Lead toxicity: a review. Interdisciplinary Toxicol. 8 (2), 55–64. https://doi.org/10.1515/intox-2015-0009 (2015).

Dikilitas, M., Karakas, S. & Ahmad, P. Effect of lead on plant and human DNA damages and its impact on the environment. In Plant metal interaction (pp. 41–67). Elsevier. (2016). https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-803158-2.00003-5

Brosnan, J. T. & Brosnan, M. E. The sulfur-containing amino acids: an overview. J. Nutr. 136 (6), 1636S–1640S. https://doi.org/10.1093/jn/136.6.1636S (2006).

Narayan, O. P., Kumar, P., Yadav, B., Dua, M. & Johri, A. K. Sulfur nutrition and its role in plant growth and development. Plant Signal. Behav. 18 (1), 2030082. https://doi.org/10.1080/15592324.2022.2030082 (2023).

Bonaventura, P., Benedetti, G., Albarède, F. & Miossec, P. Zinc and its role in immunity and inflammation. Autoimmun. Rev. 14 (4), 277–285. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autrev.2014.11.008 (2015).

Umair Hassan, M. et al. The critical role of zinc in plants facing the drought stress. Agriculture 10 (9), 396. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture10090396 (2020).

Lamiaa, M. Nutritive value and hypolipidrmic effects of mulberry leaves powder. Indian J. Appl. Res. 4, 7–12 (2014).

Adeduntan, S. A. & Oyerinde, A. S. Evaluation of chemical and antinutritional characteristics of obeche (Triplochition scleroxylon) and some mulberry (Morus alba) leaves. Int. J. Biol. Chem. Sci. 3 (4). https://doi.org/10.4314/ijbcs.v3i4.47177 (2009).

Kim, I. et al. Variation of mineral compositions in the regional, varietal, and seasonal mulberry leaves. Int. J. Industrial Entomol. 2 (1), 27–35 (2001).

Koyuncu, F., Çetinbas, M. & Erdal, İ. Nutritional constituents of wild-grown black mulberry (Morus Nigra L). J. Appl. Bot. Food Qual., 87 (2014).

Sümbül, A. Characterization of genetic diversity of mulberry (Morus alba) genotypes growing naturally in Northeastern Türkiye (Kelkit Valley) using morphological, biochemical, and molecular markers. Horticulturae 11 (3), 298. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11030298 (2025).

Krishna, H. et al. Morphological and antioxidant characteristics of mulberry (Morus spp.) genotypes. J. Saudi Soc. Agricultural Sci. 19 (2), 136–145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jssas.2018.08.002 (2020).

Khadivi, A., Hosseini, A. S. & Naderi, A. Morphological characterizations of Morus nigra L., M. alba L., and M. alba L. var. nigra. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 71 (4), 1635–1642. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10722-023-01727-0 (2024).

Hosseini, A. S., Akramian, M., Khadivi, A. & Salehi-Arjmand, H. Phenotypic and chemical variation of black mulberry (Morus nigra) genotypes. Ind. Crops Prod. 117, 260–271. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indcrop.2018.03.007 (2018).

Pearson, K. I. Mathematical contributions to the theory of evolution.—VII. On the correlation of characters not quantitatively measurable. Philosophical Trans. Royal Soc. Lond. Ser. Containing Papers Math. Or. Phys. Character. 195 (262–273), 1–47. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsta.1900.0022 (1900).

Larson, R. & Farber, B. Elementary Statistics: Picturing the World (6th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson. ISBN-13:978-0321911216 & ISBN-10:0321911210 (2014).

Tabachnick, B. G., Fidell, L. S. & Ullman, J. B. Using Multivariate Statistics6497–516 (pearson, 2013).

Draper, N. R. & Smith, H. Applied Regression Analysis (Wiley, 2014).

Cohen, J., Cohen, P., West, S. G. & Aiken, L. S. Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences. Routledge. (2013). https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203774441

Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J. & Anderson, R. E. Multivariate Data Analysis. 7th Edition. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson. (2010).

Jolliffe, I. T. Principal component analysis for special types of data (pp. 338–372). Springer New York. (2002). https://doi.org/10.1007/0-387-22440-8_13

Kaiser, H. F. The application of electronic computers to factor analysis. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 20 (1), 141–151. https://doi.org/10.1177/001316446002000116 (1960).

Chang, C. M. W., TzerKaun, H., Huang, H. T., ChiouLan, H. C., ShuTu, W. & W. S Intraspecific variation of wild mulberry (Morus acidosa Griff.) in Taiwan. J. Agric. Forestry. 49 (3), 65–75 (2000).

Toplu, C., Uygur, V. & Yildiz, E. Leaf mineral composition of olive varieties and their relation to yield and adaptation ability. J. Plant Nutr. 32 (9), 1560–1573. https://doi.org/10.1080/01904160903094321 (2009).

Velicer, W. F. The relation between factor score estimates, image scores, and principal component scores. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 36 (1), 149–159. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164476036001 (1976).

Jolliffe, I. T. & Cadima, J. Principal component analysis: a review and recent developments. Philosophical Trans. Royal Soc. A: Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 374 (2065), 20150202. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsta.2015.0202 (2016).

Cleveland, W. S. Visualizing Data (Hobart, 1993).

Kramer, M. A. Nonlinear principal component analysis using autoassociative neural networks. AIChE J. 37 (2), 233–243. https://doi.org/10.1002/aic.690370209 (1991).

Gower, J. C., Lubbe, S. G. & Le Roux, N. J. Understanding Biplots (Wiley, 2011).

Ward, J. H. Hierarchical grouping to optimize an objective function. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 58 (301), 236–244. https://doi.org/10.1080/01621459.1963.10500845 (1963).