Abstract

Mental health disorders, including depression, anxiety, and stress, are a growing global public health concern, with their prevalence influenced by various sociodemographic and contextual factors. Among these, the role of educational attainment in shaping mental health outcomes has received limited attention, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA). Given the potential impact of education on psychological well-being, this study examines the prevalence of mental health conditions. It explores how different levels of education influence depression, anxiety, and stress among university students and staff across selected SSA countries. Data from 3,227 participants across four African countries were analysed using logistic regression models to explore the relationship between educational attainment and depression, anxiety, and stress. Models were categorized into univariate, adjusted, and interaction models, controlling for age, gender, and occupation. The study further examined interactions between these variables. Higher educational attainment was consistently associated with lower odds of depression and anxiety. Postgraduate qualifications showed significantly lower odds of depression (OR = 0.60, 95% CI [0.47, 0.76]) and anxiety (OR = 0.60, 95% CI [0.47, 0.77]) compared to those with a Bachelor’s degree. Secondary school certification was linked to increased odds of depression (OR = 1.29, 95% CI [1.09, 1.54]) and anxiety (OR = 1.78, 95% CI [1.15, 2.76]). Gender differences were observed, with females exhibiting higher vulnerability to depression and stress than males. Occupation also influenced mental health outcomes, with non-academic staff showing lower odds of depression compared to students. This study highlights that higher educational attainment reduces the odds of depression and anxiety among African populations. Gender and occupation were also significant factors, emphasizing the need for targeted mental health interventions for individuals with lower educational attainment and those in vulnerable job roles. These findings suggest that increasing access to higher education may improve mental health outcomes in the region. Future research should explore causal mechanisms and consider cultural and socioeconomic factors to inform more effective mental health policies and interventions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Mental health conditions such as depression, anxiety, and stress are among the leading contributors to the global burden of disease, affecting individuals’ well-being, productivity, and overall quality of life1,2. Increasingly, good mental health is understood not merely as the absence of disorder, but as a state of holistic well-being, encompassing the ability to enjoy life and cope with routine challenges3. Mental disorders collectively account for nearly one-third of years lived with disability (YLD) worldwide3and are often comorbid with chronic conditions such as cardiovascular disease, obesity, and chronic pain4. Depression and anxiety—two of the most prevalent mental health disorders globally—affect approximately one in eight individuals4 posing a significant public health challenge, particularly in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs).

Although mental health affects people across the lifespan, its impact is especially pronounced among those navigating the demands of higher education and professional life. Academic settings expose students and staff to high levels of stress due to academic workloads, long hours, social pressure, and financial strain5,6. This study seeks to examine how educational attainment—a well-established social determinant of health—relates to the prevalence of depression, anxiety, and stress among university students and academic staff in four African countries: Ghana, Malawi, Mozambique, and Nigeria.

The central hypothesis of this study is that higher educational attainment is associated with lower prevalence of depression, anxiety, and stress, after accounting for demographic and socioecological factors. This hypothesis builds on previous research showing a complex, bidirectional relationship between education and mental health. For instance, while lower education levels have been linked to increased vulnerability to mental illness7,8early-onset mental disorders can also disrupt educational achievement and career progression9,10.

However, existing literature on this topic presents mixed findings. Some studies suggest a protective effect of higher education on mental health, while others show inconsistent results depending on gender, socioeconomic background, and geographic region11,12,13. For example, in Ghana, diploma-holding psychiatric nurses reported higher levels of depression than their more educated counterparts12 while an Iranian study found no significant association between educational level and depression or anxiety among students5. Gender disparities are also notable, with females generally reporting higher rates of mental health issues than males14,15 potentially due to intersecting effects of socioeconomic status, educational opportunity, and exposure to stressors16,17.

In LMICs, such as those in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), the challenges are further compounded by barriers to mental healthcare access, including limited mental health infrastructure, a shortage of professionals, stigma, and high out-of-pocket costs7,18,19,20,21. These factors result in treatment gaps as high as 90% in some regions7 reinforcing the importance of upstream interventions, such as understanding how education levels influence psychological outcomes.

To guide our investigation, we draw upon the Socio-Ecological Model (SEM) and established theoretical frameworks in mental health. The SEM offers a lens through which mental health can be understood as the product of dynamic interactions between individual, interpersonal, community, and societal factors22,23. For example, individual traits (e.g., coping mechanisms), social support networks, institutional settings, and broader societal influences (e.g., stigma, health policy) all play a role in determining mental well-being. From a psychosocial stress perspective, models such as the job demand-control model and diathesis-stress theory further explain how excessive demands and low perceived control, common in academic environments, can lead to stress, burnout, and related disorders, especially in individuals with underlying vulnerabilities.

Despite the established importance of education in shaping life outcomes, there remains limited empirical evidence from SSA that explores how educational attainment influences mental health outcomes in higher education contexts. Most existing studies either aggregate mental health data across general populations or focus on students alone, without including academic staff or examining cross-country differences.

This study aims to fill this gap by addressing the following research question:

What is the relationship between educational attainment and the prevalence of depression, anxiety, and stress among university students and staff in Ghana, Malawi, Mozambique, and Nigeria? Understanding this relationship is crucial for developing tailored, evidence-based interventions that address the unique mental health challenges faced by academic communities in SSA. The findings could also inform national mental health strategies and educational policy in these countries, with broader implications for the global agenda on health equity and educational advancement.

Methodology

Study design

This study is a web-based cross-sectional survey of university students and staff in Ghana, Malawi, Mozambique, and Nigeria conducted between April 16th to November 18th, 2024. Reporting of this study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guideline for cross-sectional studies.

Study population

The participants in this study consist of students and staff from various universities and colleges in Ghana, Malawi, Mozambique, and Nigeria. A convenience sampling technique was employed for participant recruitment. The sample size for this study was calculated assuming a 50% response rate, as no similar study had been conducted in Africa. Using a desired precision of 2% and a 5% significance level for a two-sided test, this method resulted in a sample size of 2,684 respondents, which is sufficient to detect statistical differences in an online cross-sectional study on mental health symptoms of university staff and students in four selected African countries.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Eligible participants were Africans who were studying or working in a tertiary institution in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) at the time of the study and were able to provide consent. Individuals who were not affiliated with an African university as students or staff during the study period or who could not provide consent were excluded. Additionally, only responses from participants who completed all items on the DASS-21 survey were included in the final analysis24. Also, we received responses from some individuals outside Ghana, Malawi, Mozambique, and Nigeria who have accessed the survey through social media. Their responses were also excluded during analysis due to the very low responses received.

Data collection tool

A validated self-administered survey was adapted with minor modifications to suit the objectives of this study. The modification was to include demographic variables and the consent statement as a preamble. The first section of the survey inquired about the participants’ sociodemographic characteristics including age, gender, country of origin, name of institution, year of study, and school [students were asked about the course of study, while staff reported the school where they were employed], the highest level of qualification, marital status, faculty level [student, academic or non-academic staff]). The second section of the survey measured the mental health condition, and it’s described below.

The DASS-21 (Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale-21) questionnaire was used for the data collection. It is a validated questionnaire used for assessing depression, anxiety, and stress25. The tool is capable of differentiating symptoms of anxiety, and stress, and each of the three DASS-21 scales contains 7 items, divided into subscales with similar content scored on a Likert scale from 0 to 3 (0: did not apply to me at all, 1: applied to me to some degree, 2: applied to me to a considerable degree, 3: applied to me very much). For depression, a score of 0–9 in the depression subscale was considered normal, 10–13 as mild, 14–20 as moderate, 21–27 as severe, and 28 and above as extremely severe. For anxiety, a score of 0–7 was regarded as normal, 8–9 as mild, 10–14 as moderate, 15–19 as severe, and 20 and above as extremely severe for persons with anxiety. For stress, a score of 0–14 was regarded as normal, 15–18 as mild, 19–25 as moderate, 26–33 as severe, and 34 and above as extremely severe for participants who had experienced stress.

Data collection procedure

The final questionnaire shown in Supplementary File 1 was deployed in both Portuguese and English using Google Forms across SSA countries. A team member from Mozambique, in collaboration with their university’s language school, conducted the forward and backward translation of the survey into Portuguese, ensuring the retention of its original meaning. The Portuguese version of the questionnaire was designed to ensure the participation of non-English speakers of Lusophone countries where Portuguese is spoken, like Mozambique. Other non-English speaking versions of the survey such as Arabic or French, were not developed due to limited resources and the absence of a local collaborator for translation and distribution. Notwithstanding, at least one non-English speaking questionnaire was necessary to obviate the limitations that have been reported in previous survey research8,9. Before data collection, the questionnaire was pretested on 30 participants who were not included in the final survey deployment. Based on the feedback obtained from the pre-test, an appropriate modification was made to the questionnaire. The Cronbach’s alpha (α) coefficient of the DASS-21 scale was 0.82 (all items).

For ease of distribution and access, an e-link of the survey was posted on social media platforms [WhatsApp and Facebook] commonly used by Africans and sent via email contacts of the authors. The survey distribution relied strongly on snowballing using virtual networks to reach the target population composed of social media users and users of other online platforms. Ostensibly, an online survey provides time and cost-saving measures for data collection10,24. In short, the use of an online survey ensured that the survey could reach a large cohort of prospective respondents across SSA within time and with monetary constraints.

This study methodology exposes our findings to certain biases and sample representation limitations. The reliance on a web-based survey may have introduced selection bias, as access was limited to individuals with internet connectivity and digital literacy, potentially underrepresenting disadvantaged populations. Additionally, the use of convenience sampling and snowball recruitment may have led to sampling bias, with participants more engaged in mental health discussions being overrepresented. Excluding incomplete responses on the DASS-21 scale may also contribute to attrition bias, as individuals with severe mental health challenges might be less likely to complete the survey. Furthermore, the reliance on self-reported data introduces the possibility of recall and social desirability biases. The absence of qualitative data limits a deeper understanding of cultural and institutional influences on mental health.

Ethical consideration

Ethical approval was obtained from several institutions, including the Research Ethics Committee of the Federal University of Technology Owerri, Nigeria (FUT/SOHT/REC/vol. 4/2), the Research Ethics Committee of Abia State University Uturu, Nigeria (ABSU/REC/OPT/002/2024), the Health Research Ethics Committee of Ahmadu Bello University Kano, Nigeria (NHREC/BUK-HREC/476/10/2311) and the Committee on Human Research, Publication and Ethics, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Ghana (CHRPE/AP/374/24). Prior to data collection, participants were provided with detailed information about the study, including its nature and purpose, through an online preamble. Informed written consent was obtained electronically from all participants and the study adhered to the Helsinki Declaration. Participants were assured about the anonymity and confidentiality of the information provided.

Data analysis

The sample characteristics were presented using frequencies and percentages, followed by an analysis of the prevalence of anxiety, depression, and stress by confounding factors. The outcome variables were treated as binary outcomes (Yes and No), with a depression score of 0–9 indicating no depression and a score of 10 or higher indicating major depression. For anxiety, scores 0–7 were categorised as No, 8 or higher as Yes. For Stress: scores of 0–14 were categorised as No, and 15 or higher as Yes. To identify factors associated with anxiety, depression, and stress, odds ratios (OR) were calculated using univariate analysis to assess the association with educational attainment (1a, 2a and 3a). Adjusted odds ratios (AORs) and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were obtained from the adjusted multivariable logistic regression model without interaction (1b, 2b and 3b) and with interaction (1c, 2c and 3c) to measure the factors associated with the outcome measures. The test of statistical significance was set at 5% and results were reported using ORs, AORs, and their Cis rather than p value as these are recommended26. The choice not to report exact p-values alongside odds ratios and confidence intervals is to enhance interpretability and avoid overemphasizing arbitrary thresholds of statistical significance. Presenting odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals offers a more meaningful understanding of the magnitude, direction, and precision of associations, particularly for applied audiences such as policymakers and institutional stakeholders. This approach is in line with best practices recommended by leading reporting guidelines and statistical bodies (e.g., STROBE, the American Statistical Association), which advocate for prioritizing effect sizes and confidence intervals over sole reliance on p-values. Additionally, this reporting strategy supports more robust and contextually grounded interpretation, especially in subgroup comparisons such as between African and broader international student populations.

Results

Characteristics of the study population

The flowchart in Fig. 1 presents the data selection process for participants’ inclusion in the study following data organising. Only data for four countries namely: Nigeria, Ghana, Mozambique, and Malawi were included in the final analysis.

The final analysis included data for 3,221 participants, 57.2% females (n = 1,845) and 42.0% males (n = 1,352), with a small percentage of non-binary/genderqueer participants (0.2%) and those who preferred not to disclose their gender identity (0.6%). The breakdown of the participants by their demographic characteristics is detailed in Table 1.

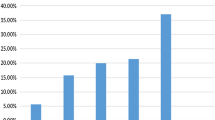

Prevalence of mental health outcomes by educational level

Figure 2 presents the prevalence of depression, anxiety, and stress across different educational qualification levels. Participants with secondary school or lower qualifications reported the highest prevalence of all three adverse mental health outcomes. In contrast, those with postgraduate qualifications consistently reported lower rates of depression, anxiety, and stress.

Depression: The highest prevalence of depression was observed among participants with secondary school or lower education, while the lowest prevalence was found among those with postgraduate qualifications.

Anxiety: Similar to depression, anxiety was most prevalent in participants with lower education levels, while those with postgraduate qualifications reported the lowest prevalence.

Stress: Stress prevalence followed the same trend, with higher rates among participants with lower educational qualifications and lower rates among those with postgraduate qualifications.

Association between educational attainment and mental health outcomes

Results of the logistic regression models, exploring the association between educational attainment and incidents of depression, stress, and anxiety among study participants, were shown in Table 2. Three classes of models were developed to assess the association of each of these mental health outcomes with educational attainment.

In the univariate model (1a) examining the association of depression and education, participants with a postgraduate qualification (e.g., a Master’s or PhD) had significantly lower odds of experiencing depression compared to those with a Bachelor’s degree (OR = 0.60, 95% CI [0.47, 0.76]). Conversely, those with a secondary school certificate had increased odds of depression relative to those with a Bachelor’s degree (OR = 1.29, 95% CI [1.09, 1.54]). Also, the univariate model (2a) assessing anxiety as an outcome of education, showed similar protective effects for postgraduate education, where individuals with higher degrees had lower odds of anxiety (OR = 0.60, 95% CI [0.47, 0.77]). The secondary school certificate level also approached significance, suggesting a potential increase in anxiety risk but without crossing the significance threshold. Stress outcomes (3a) did not exhibit significant associations across educational levels. While postgraduate qualification showed a protective trend against stress, this association was not statistically significant.

Controlling for age, gender, and occupation (1b, 2b, and 3b) strengthened these findings. In model 1b, the lower odds of depression (OR = 0.60, 95% CI [0.47, 0.76]) and anxiety (OR = 0.69, 95% CI [0.49, 0.98]), among those with postgraduate degrees remained significant as did the higher odds of depression among participants with only secondary school certificates (OR = 1.25, 95% CI [1.05, 1.50]). This suggests that higher education is consistently associated with a decreased likelihood of depression and anxiety. Similarly, being male had a protective effect against stress in model 3b (OR = 0.71, 95% CI [0.61, 0.83]) and against anxiety (OR = 0.81, 95% CI [0.70, 0.94]).

The impact of occupation on mental health conditions varied across the models for depression, anxiety, and stress. In the model examining depression, being employed as a non-academic staff member was associated with significantly lower odds of depression (OR = 0.54, 95% CI: 0.32–0.88) compared to other being a student. Being an academic staff, however, did not show a significant association with depression. Similarly, in the expanded model incorporating interaction effects, non-academic staff continued to exhibit reduced odds of depression (OR = 0.55, 95% CI: 0.32–0.92), suggesting a potential protective effect of certain job roles on depression risk.

Models with interaction terms reveal nuanced interactions between age, gender, and educational level. For example, in 1c, young adults with a secondary school certificate had significantly higher odds of depression (OR = 2.12, 95% CI [1.37, 3.29]) This pattern held in model 3c for stress, with young adults holding a secondary school certificate showing increased odds of stress (OR = 1.79, 95% CI [1.15, 2.79]). In model 2c, similar interactions were seen for anxiety, where young adults with a secondary school certificate had higher odds of anxiety (OR = 1.78, 95% CI [1.15, 2.76]).

Discussion

The results of this study reveal significant gender and educational disparities in depression, anxiety, and stress among university staff and students in four selected African countries, which are consistent with a growing body of knowledge that underscores the impact of educational attainment, gender, and age on mental health outcomes. Significant gender disparities were observed, with females exhibiting higher susceptibility to depression and stress compared to males. This aligns with prior research and may be attributed to gender-related stressors, such as social roles and caregiving responsibilities, societal expectations, and potential hormonal influences relevant in the Sub-Saharan African context27. This suggests that gender-related stressors, such as social roles and caregiving responsibilities, contribute to mental health vulnerabilities among women28,29,30. The fact that anxiety levels did not differ significantly between genders suggests that factors beyond gender might influence anxiety more strongly, aligning with studies indicating other complex determinants31,32,33.

Furthermore, the traditional gender roles in many SSA societies often place a heavier burden of caregiving and domestic responsibilities on women27. This, combined with potential exposure to gender-based discrimination and violence, can contribute to increased stress and vulnerability to mental health issues34. Additionally, cultural factors might influence help-seeking behaviours, with women potentially facing greater stigma or barriers to accessing mental health support35. This gender disparity in mental health underscores the need for gender-specific interventions, especially in contexts where women face significant cultural and economic challenges35.

Higher educational attainment emerged as a significant protective factor against depression and anxiety, with postgraduate qualifications associated with lower odds compared to a Bachelor’s degree. This protective effect may be mediated by factors such as socioeconomic advantages, enhanced coping mechanisms, and stronger social support networks often associated with higher education levels34,36,37,38. Conversely, participants with secondary school certificates or lower demonstrated the highest prevalence of depression, anxiety, and stress. This vulnerability may stem from challenges like limited job opportunities and heightened financial stress, as corroborated by existing literature36,37. Having financial security could provide individuals with greater control over their lives and a sense of stability34leading to improved mental well-being39. Also, the process of higher education may equip individuals with better problem-solving and critical-thinking skills, which can translate into more effective coping mechanisms when facing challenges40. Educational achievements can also boost self-esteem and confidence, contributing to a more positive self-image and improved mental health41. Additionally, higher education often provides opportunities for building social connections and support networks, which are crucial for navigating life stressors42.

It is notable that while univariate analysis showed a protective trend for postgraduate education against stress, this relationship was not statistically significant in adjusted models. Furthermore, logistic regression analysis indicated that educational level did not have a statistically significant effect on anxiety. These findings suggest that while higher education offers substantial protection against depression, other factors like personality traits or personal circumstances may play a larger role in influencing stress and anxiety. This aligns with previous research, which suggests that anxiety could be influenced by a variety of interacting factors beyond just socioeconomic influences43,44.

Regarding the impact of age, the adjusted models revealed nuanced interactions, particularly showing that young adults (≤ 24 years) with a secondary school certificate had significantly higher odds of experiencing depression, anxiety, and stress. This finding underscores the specific vulnerability of individuals with lower educational qualifications during the transition phase of young adulthood within the university environment, where academic and professional pressures are high. Contrary to some existing literature45age did not significantly influence mental health outcomes in our study. This may suggest that within the specific population of university staff and students in SSA, other factors, such as educational attainment or gender, exert a stronger influence, or that factors like resilience developed over time or differing exposure to academic/career pressures across age groups within this setting may play a role.

The findings of this study have potential policy implications and open areas for future research. The findings underscore the need for targeted mental health interventions aimed at improving mental health literacy access, awareness, understanding, and decision-making related to one’s mental health, especially for individuals with lower educational attainment who are more vulnerable to depression, anxiety, and stress. In line with similar recommendations46educational institutions should consider offering staff and students mental health resources and support to help them cope with stressors, particularly those from disadvantaged backgrounds who may face heightened financial and academic pressures. Furthermore, the protective effect of higher education on mental health suggests that policies aimed at increasing access to higher education could yield long-term public health benefits by improving mental health outcomes47.

Future research should investigate the mechanisms by which educational attainment, gender, and age affect mental health disparities, and the impact of specific educational factors (for example, field of study and academic pressure) on mental health outcomes. Longitudinal studies could examine how variations in these factors impact mental health outcomes over time, offering insights into causal relationships and changing risks. Furthermore, incorporating psychological and social variables—such as resilience, personality traits, and social support—could enhance our understanding of the intricate interactions between education, gender, and mental health. By exploring these associations in various cultural and socioeconomic contexts, future research could lead to more tailored and culturally relevant mental health interventions while also informing policies aimed at addressing educational and gender disparities in mental health. Further qualitative research to learn about the experiences of students and staff with different educational backgrounds and their thoughts on mental health support services is underway.

Strengths and limitations

The study has numerous strengths, including its robust design, which is highlighted by a significant sample size of 3,227 participants from four sub-Saharan African (SSA) countries. This strengthens the reliability and diversity of the findings, increases the ability to detect true associations, reduces the likelihood of Type II errors, and the findings are more likely to represent the target population which improves the external validity of the study. Utilising the validated DASS-21 questionnaire ensured consistent assessment of depression, anxiety, and stress, contributing to accurate data collection. By offering the survey in both English and Portuguese, the study expanded its reach to include participants from various linguistic backgrounds who may have been ignored in previous online studies48,49,50. Additionally, ethical rigour was maintained through approvals from multiple respected institutions, reinforcing the study’s integrity. Despite these strengths, the study faced certain limitations. The reliance on convenience sampling may have introduced selection bias, potentially affecting the generalizability of results to the broader population. The cross-sectional nature of the study limits the ability to establish cause-and-effect relationships. Self-reported data can be susceptible to bias, while the online format might have excluded those with limited internet access, impacting representativeness. Although adjustments were made for confounding factors, unmeasured variables like socioeconomic status could still influence outcomes. Additionally, language and literacy differences, even with the Portuguese version, might have posed challenges to some participants’ understanding and response accuracy. While the study purports to address educational and mental health across SSA writ large, the study participants hail largely if not almost exclusively from four of the twenty-four countries in SSA which limits the geographic representation. Although this study was conducted post-COVID-19 and controlled for key sociodemographic factors, it did not account for the potential lingering effects of the pandemic on mental health. Given the significant impact of COVID-19 on psychological well-being, the absence of this variable may limit the comprehensiveness of our findings. Additionally, the cross-sectional design remains a major limitation, as it prevents the establishment of causal relationships between educational attainment and mental health outcomes. Without longitudinal data, the directionality and temporal effects of these associations cannot be determined, leaving room for alternative explanations.

Conclusion

This study highlights the complex interplay between educational attainment, gender, and mental health outcomes. The findings suggest that higher educational attainment offers significant protection against mental health challenges, while those with lower educational qualifications are more vulnerable to depression, anxiety, and stress. As a result, organizations and employers can play a pivotal role in supporting employees’ mental health by fostering a supportive and inclusive work environment. Offering mental health services and programs tailored to employees with lower educational qualifications could be a crucial step in reducing the mental health burden. Moreover, providing mental health training for managers and supervisors can ensure that they recognise early signs of mental health struggles among employees, creating a more proactive and supportive workplace. For young adults, especially those with only a secondary school certificate, providing mentorship, career guidance, and accessible resources in the workplace can offer both emotional and professional support, thereby reducing stress and improving mental well-being. These workplace interventions, combined with educational support, can help create a more holistic approach to reducing mental health disparities. A study looking at the outcomes between students and further research to understand the underlying mechanisms and factors that contribute to the differences is warranted. Overall, the findings from this discussion highlight the importance of considering educational attainment when examining mental health outcomes and developing interventions to improve mental health in SSA and globally.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- SSA:

-

sub-Saharan Africa

- DASS-21:

-

Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale-21

- AOR:

-

Adjusted odd ratio

- OR:

-

Odd ratios

References

Shah, S. M. A. et al. Psychological responses and associated correlates of depression, anxiety and stress in a global population, during the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic. Community Ment Health J. 57, 101–110 (2021).

Varma, P., Junge, M., Meaklim, H. & Jackson, M. L. Younger people are more vulnerable to stress, anxiety and depression during COVID-19 pandemic: A global cross-sectional survey. Prog Neuro-Psychopharmacology Biol. Psychiatry 109, 110236, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pnpbp.2020.110236(2021).

Wittenborn, A. K., Lachmar, E. M., Huerta, P., Mitchell, E. A. & Tseng, C. F. Global epidemiology, etiology, and treatment: depressive and anxiety disorders across the lifespan. Handb. Syst. Fam Ther. Set. 4–4, 245–265 (2020).

Osborn, T. L., Wasanga, C. M. & Ndetei, D. M. Transforming Mental Health all BMJ doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.o1593. (2022).

Rezvan, A. F., Srimathi, N. L. & Srimathi, N. L. Impact of levels of education on depression and anxiety in Iranian students. Pakistan J. Psychol. Res. 37, 67–78 (2022).

Di Mario, S., Rollo, E., Gabellini, S. & Filomeno, L. How stress and burnout impact the quality of life amongst healthcare students: an integrative review of the literature. Teach. Learn. Nurs. 000, 1–9 (2024).

Kondirolli, F. & Sunder, N. Mental health effects of education. Health Econ. 31, 22 (2022).

Breslau, J. et al. Mental disorders and subsequent educational attainment in a US National sample. J. Psychiatr Res. 42, 708–716 (2008).

Esch, P. et al. The downward spiral of mental disorders and educational attainment: A systematic review on early school leaving. BMC Psychiatry. 14, 1–13 (2014).

Riglin, L. et al. ADHD and depression: investigating a causal explanation. Psychol. Med. 51, 1890–1897 (2021).

Bjelland, I. et al. Does a higher educational level protect against anxiety and depression? The HUNT study. Soc. Sci. Med. 66, 1334–1345 (2008).

Opoku Agyemang, S., Ninnoni, J. P. & Enyan, N. I. E. Prevalence and determinants of depression, anxiety and stress among psychiatric nurses in ghana: a cross-sectional study. BMC Nurs. 21, 1–11 (2022).

Jamison, D. T. et al. Global health 2035: a world converging within a generation. Lancet 382, 1898–1955 (2013).

Gupta, R. et al. Depression and HIV in botswana: A population-based study on gender-specific socioeconomic and behavioral correlates. PLoS One 5(12), e14252, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0014252 (2010).

Tomlinson, M., Grimsrud, A. T., Stein, D. J., Williams, D. R. & Myer, L. The epidemiology of major depression in South africa: results from the South African stress and health study. South. Afr. Med. J. 99, 368–373 (2009).

Kraft, P. & Kraft, B. Explaining socioeconomic disparities in health behaviours: A review of biopsychological pathways involving stress and inflammation. Neurosci. Biobehav Rev. 127, 689–708 (2021).

Reiss, F. et al. Socioeconomic status, stressful life situations and mental health problems in children and adolescents: results of the German BELLA cohort-study. PLoS One. 14, 1–16 (2019).

Muhorakeye, O. & Biracyaza, E. Exploring barriers to mental health services utilization at Kabutare district hospital of rwanda: perspectives from patients. Front Psychol 12, 638377, https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.638377(2021).

Bruwer, B. et al. Barriers to mental health care and predictors of treatment dropout in the South African stress and health study. Psychiatr Serv. 62, 774–781 (2011).

Colizzi, M., Lasalvia, A. & Ruggeri, M. Prevention and early intervention in youth mental health: is it time for a multidisciplinary and trans-diagnostic model for care? Int. J. Ment Health Syst. 14, 1–14 (2020).

Bantjes, J., Kessler, M. J., Hunt, X., Stein, D. J. & Kessler, R. C. Treatment rates and barriers to mental health service utilisation among university students in South Africa. Int. J. Ment Health Syst. 17, 1–16 (2023).

Bakhtari, F., Sarbakhsh, P., Daneshvar, J., Bhalla, D. & Nadrian, H. Determinants of depressive symptoms among rural health workers: an application of socio-ecological framework. J. Multidiscip Healthc. 13, 967–981 (2020).

Ifeoma, O. A. & New Perspective on Mental Illness Prevention Strategy. : Utilizing the Socio-Ecological Model Prevention Approach with Nigerian University Students. 7, (2022).

Russell, D. W. UCLA loneliness scale (Version 3): reliability, validity, and factor structure. J. Pers. Assess. 66, 20–40 (1996).

Dreyer, Z., Henn, C. & Hill, C. Validation of the depression anxiety stress Scale-21 (DASS-21) in a non-clinical sample of South African working adults. J. Psychol. Afr. 29, 346–353 (2019).

Cumming, G. Replication and p intervals: p values predict the future only vaguely, but confidence intervals do much better. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 3, 286–300 (2008).

Hirsh, C. E., Treleaven, C. & Fuller, S. Caregivers, gender, and the law: an analysis of family responsibility discrimination case outcomes. Gend. Soc. 34, 760–789 (2020).

Tsukamoto, R. et al. Gender differences in anxiety among COVID-19 inpatients under isolation: A questionnaire survey during the first and second waves of the COVID-19 pandemic in Japan. Front. Public. Heal. 9, 708965 (2021).

Sharma, N., Chakrabarti, S. & Grover, S. Gender differences in caregiving among family - caregivers of people with mental illnesses. World J. Psychiatry. 6, 7 (2016).

Eugene, D. et al. Mental health during the Covid-19 pandemic: an international comparison of gender-related home and work-related responsibilities, and social support. Arch. Womens Ment Health. https://doi.org/10.1007/S00737-024-01497-3 (2024).

Harrison, O. et al. Gender differences in the association between anxiety and interoceptive insight. Authorea Prepr. https://doi.org/10.22541/AU.171647268.89829982/V1 (2024).

Alabi, O. J., Olonade, O. Y. & Complexities Dynamism, and changes in the Nigerian contemporary family structure. 99–112 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1108/S1530-353520220000018008/FULL/PDF

Meijer, S. S., Sileshi, G. W., Kundhlande, G. & Catacutan, D. The role of gender and kinship structure in household Decision-Making for agriculture and tree planting in Malawi. J. Gend. Agric. Food Secur. 1, 54–76 (2015).

Asadi, K., Yousefi, Z. & Parsakia, K. The role of family in managing financial stress and economic hardship. J. Psychosociological Res. Fam Cult. 2, 11–19 (2024).

Akiki, R. R. Stressors in Modern West African Marriages: Economic, Cultural, and Health Challenges. 3, 66–71 (2024).

Al-Shehri, M. M., Harazi, N. M., Elmagd, M. H. A., Alshmemri, M. & T, M. A. & Prevalence of depression, anxiety and stress among secondary school students in Jeddah City. ASEAN J. Psychiatry. 23, 1–12 (2022).

Barnawi, M. M., Sonbaa, A. M., Barnawi, M. M., Alqahtani, A. H. & Fairaq, B. A. Prevalence and Determinants of Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Among Secondary School Students. Cureus 15, (2023).

Jarego, M. et al. Socioeconomic status, social support, coping, and fear predict mental health status during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic: a 1-year longitudinal study. Curr. Psychol. 1–14 (2024) (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/S12144-024-06553-W

HASSAN, M. F. & SAID, Y. M. HASSAN, N. M., KASSIM, E. S. U. Financial wellbeing and mental health: A systematic review. Stud Appl. Econ 39(1–24), http://doi.org/10.25115/eea.v39i4.4590(2021).

Li, X., Gao, Z. & Liao, H. The effect of critical thinking on translation technology competence among college students: the chain mediating role of academic Self-Efficacy and cultural intelligence. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 16, 1233 (2023).

Abdulghani, A. H. et al. Does self-esteem lead to high achievement of the science college’s students? A study from the six health science colleges. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 27, 636–642 (2020).

Al-Shaer, E. A., Aliedan, M. M., Zayed, M. A., Elrayah, M. & Moustafa, M. A. Mental health and quality of life among university students with disabilities: the moderating role of religiosity and social connectedness. Sustain. 2024. 16, Page 644 (16), 644 (2024).

Yousaf, A., Naveed, A. P. & Traits Coping strategies and social support in patients with depression and anxiety. Artic Int. J. Sci. Res. Manag. 3, 2321–3418 (2023).

Thuy, N. T. Personality traits and anxiety disorders of Vietnamese early adolescents: the mediating role of social support and Self-Esteem. Open. Psychol. J. 16, 1–8 (2023).

Li, L. et al. Successful aging was negatively associated with depression and anxiety symptoms among adults aged 65 years and older in ningbo, China. (2024). https://doi.org/10.21203/RS.3.RS-4093183/V1

Tomas, N., Poroto, A. & Mangundu, A. M. Institutional barriers to the healthy promoting of universities in higher education in Africa. 293–316 (2024). https://doi.org/10.4018/979-8-3693-8860-0.CH012

Waqar, Y., Rashid, S., Anis, F. & Muhammad, Y. Inclusive education and mental health: addressing the psychological needs of students in Pakistani schools. Res. J. Soc. Issues. 6, 46–60 (2024).

Osuagwu, U. L. et al. Misinformation about COVID-19 in sub-saharan africa: evidence from a cross-sectional survey. Heal Secur. 19, 44–56 (2021).

Langsi, R. et al. Prevalence and Factors Associated with Mental and Emotional Health Outcomes among Africans during the COVID-19 Lockdown Period—A Web-based Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. Vol. 18, Page 899 18, 899 (2021). (2021).

Osuagwu UL, Agho KE, Ekpenyong BN, Mashige KP, Ishaya, T, editors. Africa’s knowledge bridge: empowering global access to research resources in a COVID world [Internet]. Sydney (AU): Western Open Books; 2024 [cited 14 March 2025]Available from https://doi.org/10.61588/VBOX7053

Acknowledgements

We wish to express our sincere gratitude to all the participants who contributed to this study. We also thank the members of Professor Kelechi Ogbuehi, Professor Tuwani Rasengane, and Dr Godwin Ovenseri-Ogbomo of the Centre for Eyecare and Public Health Intervention Initiative (CEPHII) for their support in establishing the mental health research group.

Funding

This work was funded by a grant from the Commonwealth of Australia, represented by the Department of Health (Grant Activity 4-DGEJZ1O/4-CW7UT14). There are no financial motivations or conflicts of interest that could have impacted the design, conduct, or reporting of this study. The integrity of the research process and its findings remains our top priority, and we affirm that our work has been conducted in an unbiased manner, free from any external influences.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: NEE, NM, and ULO; Methodology: All authors; Software: EEJ, MAK, KEA and ULO; Validation: All authors; Formal analysis: EEJ; Investigation: TSSM, EEJ, ED-N, MOO, IOO, NW, MM, OUA, UEU, GOO, KPM, BNE, MAK, NJE, NEE, NM, KEA, ULO; Resources: NEE, NM and ULO; Data curation: ED-N, MOO, IOO, OUA, UEU, GOO, BNE, NEE, NM, IIBdS and ULO; Project administration: NEE, NM, IIBdS, and ULO., Writing original draft: TSSM, EEJ, ED-N, MOO, IOO, NW, MM, GOO, MAK, NJE, NEE, and ULO., Writing-review, and editing: All authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval for this study was secured from several institutions, including: The Research Ethics Committee of the Federal University of Technology, Owerri, Nigeria (FUT/SOHT/REC/vol. 4/2), the Research Ethics Committee of Abia State University, Uturu, Nigeria (ABSU/REC/OPT/002/2024), the Health Research Ethics Committee of Ahmadu Bello University, Kano, Nigeria (NHREC/BUK-HREC/476/10/2311) and the Committee on Human Research, Publication and Ethics at Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Ghana (CHRPE/AP/374/24). Before data collection, participants received detailed information about the study through an online preamble and electronically provided informed consent. The study complied with the Helsinki Declaration, ensuring the anonymity and confidentiality of all participant information.

Clinical trial number

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Magakwe, T.S.S., John, E.E., Daniel-Nwosu, E. et al. Association between educational attainment and mental health conditions among Africans working and studying in selected African countries. Sci Rep 15, 20578 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-05831-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-05831-2