Abstract

The Western U.S. is undergoing notable transformations in its hydrological patterns, distinguished by rising variability and recurrent “whiplash” shifts between extreme wet and dry phases. Our comprehensive analysis of 469 streamflow stations from 1981 to 2023 reveals a substantial increase in hydrological whiplash events, with a peak of 206 stations experiencing dry-to-wet whiplash in the early 1990s. We establish strong links between these streamflow extremes and sub-seasonal to seasonal teleconnection factors, particularly the Western Pacific Oscillation (WP) and Eastern Pacific/North Pacific Oscillation (EPO). Additionally, we demonstrate the combined impacts of the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) and the Madden-Julian Oscillation (MJO), with MJO Phases 2/3 showing a positive relationship (correlation coefficients = 0.45) with wet conditions in the Pacific Southwest from October to December. Future projections using CMIP5 and CMIP6 models indicate increasing precipitation variability across the region. Notably, the CMIP5 RCP 8.5 scenario projects more volatile conditions than other scenarios. The results emphasize the pressing need for water management strategies that are both adaptive and flexible, to cope with the growing unpredictability of the hydrological cycle in the Western U.S.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Hydroclimatology in the western United States (US) has shown significant interannual variability and distinct regional streamflow patterns1. This variability results from complex interactions involving temperature2 precipitation combined with spring snowmelt3 multidecadal changes in streamflow regimes4 and atmospheric circulation5. Human-related factors, such as land use changes, reservoir operations, and irrigation activities6 also potentially contribute to modifying regional hydrological cycles and atmospheric conditions. Furthermore, both interannual climate patterns like the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO, 2–7 year cycle) and intraseasonal climate patterns such as the Madden-Julian Oscillation (MJO, 30–60 day cycle) have impacts throughout the year on the interaction of atmospheric rivers (ARs) and precipitation7,8,9 and streamflow patterns10,11.

ENSO significantly influences the position and strength of the jet stream, thereby altering storm track patterns across the western United States. During El Niño events, the subtropical jet stream typically strengthens and shifts southward, leading to increased precipitation in Southern California and the Southwest, while the Pacific Northwest often experiences drier conditions. Conversely, La Niña conditions generally cause the jet stream to shift northward, resulting in wetter conditions in the Pacific Northwest and drier conditions in the Southwest12. MJO also affects precipitation in the western U.S. by generating Rossby wave trains that propagate from the tropical Pacific, modifying mid-latitude circulation patterns. These atmospheric disturbances can influence the frequency and intensity of precipitation events in regions such as California13. Specific phases of the MJO are associated with varying precipitation patterns in California. For instance, MJO phases 1 and 8, as well as phases 6 and 7, have been linked to significant increases in the frequency of extreme wet events in California. These phases correspond to enhanced convection over the Pacific, which can lead to increased moisture transport into the region14. Reference15 showed the effect of El Niño changing snowfall intensity in the west US, followed by which river stream flow decreases when you move further away from the Pacific Ocean. MJO has been found to influence the precipitation and temperature dynamics in the Western US. Reference16 showed the impacts of MJO on North American weather systems with changes in precipitation and temperature anomalies, which are crucial for understanding the hydrological variability.

The influence of ARs on streamflow patterns has also been studied in the western U.S. Reference17 investigated the spatial and fractional contributions of ARs to annual peak flows, showing that the Pacific Northwest and the northern California coast had the highest proportion of AR-induced peaks (> 80%), while the interior regions experienced limited influence from ARs. AR activity also co-relates with MJO situations in the Western Pacific which sees an increase in the frequency of AR events as the MJO conditions are set up over the Western Pacific Ocean, contributing to the AR events being formed in the West Coast regions13.

Recent observations suggest increasing streamflow variability, with less predictable streamflow behavior18 and more severe droughts (Bureau of Reclamation, 2021). It was observed with earlier spring peak flows, lower snow water equivalents20 and early snowpack melt21,22. These shifts contribute to a possible “low-to-no snow future”23 creating challenges for traditional water management infrastructure and practices24. Such changes may result in hydrological extremes, including “hydrological whiplash”—rapid transitions between drought and flood conditions, posing significant challenges for water managers who must balance water storage needs during dry periods with flood mitigation during wet periods25. Recent catastrophic events, such as California’s 2012–2016 extreme drought followed by the record-breaking wet winter of 2016–2017, resulted in billions of dollars in economic damages and the evacuation of communities due to the infrastructure damage such as Oroville Dam crisis26. Hydrological whiplash in the Western U.S. is also disproportionately impacting communities with higher vulnerability and lower adaptive capacity27.

Despite substantial advancements in understanding hydrological dynamics in this critical region, a need remains for a comprehensive analysis of hydrological whiplash patterns and their connections to multi-scale atmospheric teleconnection patterns. Through this research, we aim to explore the region’s hydrological variability, emphasizing the role of teleconnections and the growing incidence of hydrological whiplashes. Specifically, we address the following research questions: (1) What are the historical patterns and frequency of hydrological whiplash events across different basins in the western U.S.? (2) How do atmospheric teleconnection patterns, including both seasonal and intraseasonal oscillations, influence the occurrence and severity of these whiplash events and related atmospheric river activity? (3) How might precipitation variability, and consequently hydrological whiplash potential, change under future climate scenarios? By addressing these questions, we provide a thorough assessment of historical trends and potential future risks related to hydrological extremes in the western U.S.

Materials and methods

Data

This study leveraged multiple data sources to analyze hydrological variations and teleconnection patterns. Streamflow data was obtained from the United States Geological Survey (USGS) National Water Information System (NWIS: https://waterdata.usgs.gov/nwis). Daily streamflow records (469 total) from 1981 to 2023 covered Western US basins based on Hydrologic Unit Code (HUC) 2 levels: Colorado River Basin (HUC14 and HUC15 combined), Great Basin (HUC16), Columbia River Basin (HUC17), and California River Basin (HUC18). Stations with long-term, continuous records were selected to enhance result reliability and avoid data interpolation.

Monthly teleconnection patterns data, including Southern Oscillation Index (SOI), North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO), Eastern Pacific/Northern Pacific Oscillation (EP/NP), El Niño 3 Region Index (NINO3), Oceanic Niño Index (ONI), El Niño 1 + 2 Region Index (NINO12), El Niño 4 Region Index (NINO4), El Niño 3.4 Region Index (NINO34), Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO), Arctic Oscillation (AO), Western Pacific Oscillation (WP), Pacific-North American Pattern (PNA), Quasi-Biennial Oscillation (QBO), were obtained from NOAA Physical Sciences Laboratory (PSL) Monthly Atmospheric and Ocean Time Series28 from 1980 to 2023. This study also utilizes the RMM (Real-time Multivariate MJO) indices29 to characterize the phase and amplitude of the MJO, accessible without missing values since 1980.

The study utilized AR data from the University of California San Diego, covering the years 1981 to 2018 for the west coast of North America. This dataset, developed using the Scripps Institution of Oceanography Reanalysis 1 (SIO-R1) based on the National Centers for Environmental Prediction (NCEP) Reanalysis, offers information about the magnitude, landfall location, and timing of ARs impacting the region. As highlighted by30characterizing the intensity and frequency of ARs is crucial for water management, flood risk assessment, and ensuring resilience against the impacts of climate change.

To examine future fluctuations in precipitation, the study employed bias-corrected climate projections from the NASA Earth Exchange Global Daily Downscaled Climate Projections (NASA-NEX GDDP) dataset, utilizing both the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 5 (CMIP5) and Phase 6 (CMIP6) scenarios. Specifically, we used RCP 4.5 and RCP 8.5 from CMIP5, and SSP2-4.5 and SSP5-8.5 from CMIP6. The NASA-NEX GDDP data31 provides higher resolution (0.25-degree) daily climate variables that have been bias-corrected to enhance reliability for local and regional studies. These downscaled projections are essential for simulating future climate conditions, particularly to anticipate variations in basin-scale wet and dry conditions. Using both CMIP5 and CMIP6, the study gains insight into potential future scenarios, allowing for robust risk assessments and adaptation strategies. Detailed descriptions of the CMIP5 and CMIP6 model members and more information are presented in Supplementary Tables S1 and S2.

Methods

Developing of normalized streamflow Indicator

This study uses a normalized streamflow as the indicator for various water year types and evaluate teleconnection impacts on streamflow conditions across the Western U.S. A water year is defined as the 12-month period from October 1 of the previous year to September 30 of the named year. This definition is used by the U.S. Geological Survey and other hydrological agencies to better represent the annual hydrological cycle, as it typically begins with the start of the wet season in the western United States. We retrieved USGS streamflow data to calculate a streamflow indicator (Ind(n)) for each station using the following equation:

where Q(n) is the annual water year streamflow volume for year n, and Qmean (1981–2020) is the 40-year streamflow volume average from 1981 to 2020. Ind(n) represents streamflow anomalies, with positive values indicating wetter than average conditions and negative values indicating drier conditions.

To normalize indicators across stations with varying baseflow levels, we divided each Ind(n) by the 1981–2020 mean:

We calculate the normalized indicator (NInd(n)) for each station from 1981 to 2023 using Eq. (2).

Defining water year types and whiplash patterns

Historically, the California Department of Water Resources (CDWR) developed the Sacramento Valley Index (SVI) in 1989, which aggregates estimated unimpaired streamflow from key gauges and applies predefined thresholds to classify year types. They categorize years into five types: Wet, Above Normal, Below Normal, Dry, and Critical, allocating 30%, 20%, 20%, 15%, and 15% of the historical record to each category, respectively. Following methodologies similar to those used by the California Department of Water Resources (CDWR) Sacramento Valley Index (SVI)32 and the San Joaquin Valley Index (SJI)33, we also categorize water years into five types: Wet (30% of historical record), Above Normal (20%), Below Normal (20%), Dry (15%), and Critical (15%). The historical record used for this categorization spans from 1981 to 2020. By summing the normalized indicator values across a given period, we capture the overall impact of prolonged hydrological extremes, providing insights into their severity and duration. We also use this indicator (NInd(n) from Eq. 2) to analyze streamflow whiplash events, defined as transitions between Wet and Critical water years (wet-to-dry whiplash) or Critical to Wet water years (dry-to-wet whiplash)27. By focusing on transitions between these extreme categories (top 30% and bottom 15% of the historical record), we identify substantial hydrological shifts that exceed normal interannual variability and represent significant challenges for water management operations.

We employ several statistical methods to explore the relationship between teleconnection patterns and hydrological whiplash conditions, including Pearson correlation coefficient (r) and Linear regression (Ordinary Least Squares, OLS) based R2. These methods examine the significance and strength of monthly relationships between teleconnection patterns and annual streamflow changes and AR behavior along the US western coast. To analyze the relationship between changes in teleconnection patterns and their impacts on annual streamflow, we perform correlation analysis on year-to-year differences. For example, we calculate the difference between normalized indicator values for consecutive years (e.g., ΔNormalized Indicator2023-2022 = Normalized Indicator2023 − Normalized Indicator2022) and pair this with the difference between telecommunication indices for the same years and specific months (e.g., SOI2023-2022 December = SOI2023 December − SOI2022 December).

Connecting intraseasonal teleconnection patterns with streamflow and AR activities

The methodology of this study focuses on analyzing the intraseasonal teleconnections between the MJO, streamflow, and ARs in the Pacific Southwest (California coast) and Northwest coast. First, the MJO activity data, including the number of days in different Phases (2/3 and 6/7) and corresponding amplitude mean and maximum values, were derived from the Real-time Multivariate MJO (RMM) index, which identifies the progression of the MJO through different phases. AR data, including AR length as the number of hours of AR-induced precipitation and the timing and location of AR-induced precipitation events, were collected from the NCEP Reanalysis (SIO-R1) datasets focusing on regions of California and the Pacific Northwest coast. Streamflow data for California and the Pacific Northwest basins were obtained as the normalized indicators from previous steps.

The analysis involves investigating the relationships between MJO phases and hydrological conditions, categorized as wet (above the historical average) or dry (below the historical average). We focus on two primary periods: October to December and January to March, corresponding to the early and late wet seasons, respectively. Scatterplots and regression models examined the relationship between the MJO phases (Phases 2/3 and 6/7) and streamflow conditions. We compute the sum of the amplitudes of days when the MJO was in specific phases for wet and dry conditions, correlating this sum with the corresponding streamflow data. To further explore the combined impact of MJO and ENSO events, we use the ONI to classify moderate to strong El Niño years and highlight their influence on streamflow and AR events. To identify moderate to strong El Niño years, we used the ONI values ≥ 1.0 °C during the three-month periods relevant to our analysis (OND and JFM). The moderate to strong El Niño years identified in our study period such as 1982–83, 1986–87, 1991–92, 1997–98, 2002–03, 2009–10, and 2015–16.

For the AR analysis, we investigate the correlation between AR length (the total number of hours of AR-induced precipitation) and MJO characteristics, including the total count of days, mean amplitude, and maximum amplitude, during the MJO phases of interest. Separate analyses are conducted for the October to December and January to March periods, considering MJO Phases 2/3 and 6/7. We use scatterplots to visualize the relationships, and linear regression models were applied to quantify the strength and significance of these correlations. While more complex measures such as the Maximal Information Coefficient could potentially capture nonlinear relationships, the relatively small sample size of our AR dataset (35–40 annual observations) and the importance of directional information led us to prioritize these established linear measures. Additionally, supplementary analyses are performed for the Pacific Northwest to provide a regional comparison of MJO’s influence on ARs and streamflow, highlighting the variability and potential teleconnections in different hydrological contexts.

Assessment of future precipitation conditions

To anticipate future precipitation conditions, which significantly drive basin wet and dry conditions and transitions between these states, we conduct an in-depth analysis using NASA-NEX GDDP CMIP5 (RCP 4.5 and 8.5) and CMIP6 (SSP2-4.5 and 5-8.5) precipitation data. Specifically, we examine multi-model precipitation projections for four major basins in the western United States, calculating a series of statistical measures to understand long-term precipitation variability and trends.

The statistical analyses include a 40-year moving mean, 40-year moving median, 40-year moving coefficient of variation, and 40-year moving skewness. These moving statistics are computed using precipitation data for the period spanning from 1980 to 2020 to 2060–2100, providing insight into how precipitation regimes are projected to evolve across the western U.S. basins.

The 40-year moving mean and median are used to assess general trends in precipitation levels, indicating whether precipitation’s average and central tendencies are expected to increase or decrease under future climate scenarios. In addition, precipitation skewness is used to measure the asymmetry of precipitation distribution, indicating the tendency towards extreme wet or dry conditions. A positive skewness value implies more frequent low-precipitation events, whereas negative skewness suggests more frequent high-precipitation events. Here, the 40-year moving skewness is used to study potential changes in the asymmetry of comprehensive statistical analysis and is crucial for evaluating potential future fluctuations in precipitation and their implications for hydrological extremes, including wet and dry spells as well as rapid transitions between these conditions—commonly referred to as hydrological whiplashes.

The coefficient of variation (CV), calculated as the ratio of the standard deviation to the mean, is used to assess the variability and volatility of precipitation patterns. A higher CV indicates greater variability, signifying more unpredictable precipitation conditions that could lead to hydrological extremes. By employing the 40-year moving coefficient of variation, we quantify the relative variability of precipitation over time and compare the spatiotemporal distributions in maps, offering a perspective on how consistent or erratic future precipitation patterns might become. This approach allows us to evaluate changes in precipitation trends, volatility, and the potential for hydrological extremes under varying climate conditions.

Results and discussion

Our analysis reveals pronounced variability in hydrological conditions across the Western U.S., characterized by increasing frequency and severity of whiplash events. We first examine the spatial and temporal patterns of these transitions, followed by their teleconnection drivers, subsequently analyze their relationship with intraseasonal oscillations and atmospheric rivers, and finally explore future projections under various climate scenarios.

Historical hydrological whiplash patterns

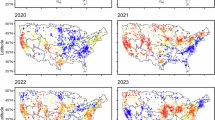

During the water years from 2018 to 2023, the Western U.S. experienced significant shifts in hydrological conditions, transitioning between wet and dry phases. Notable switches were observed from 2019 to 2020 and 2022 to 2023 (Fig. 1a,f). In 2019 (Fig. 1b), a predominance of wet conditions was evident across southern regions, with many stations represented by blue circles. This wet phase was followed by a sharp transition to drier conditions in 2020 (Fig. 1c), characterized by increased stations classified as Dry or Critically Dry, indicated by red circles.

The water year 2021 (Fig. 1d) was marked by persistently dry conditions, with a high density of stations displaying critically low streamflow values, suggesting a continuation and potential exacerbation of multi-year drought conditions. However, by 2022 (Fig. 1e), a spatially heterogeneous pattern emerged, with northern regions in the Columbia River Basin experiencing above normal or wet conditions while other basins remained in deficit. This contrast highlighted the spatial variability in hydrological responses across the Western U.S., driven by differing climatic influences and watershed characteristics.

Shifts in wet and dry conditions and multi-year droughts at western U.S. hydrological stations, 2018–2023. (a), Map showing normalized streamflow deficit/surplus for the 2018 water year, where values of 1 and − 1 represent streamflow volumes equal to surplus and deficit conditions relative to the 1981–2020 average, respectively. Circle colors indicate water year classifications: Wet, Above Normal, Below Normal, Dry, and Critically Dry (Critical), based on the normalized streamflow data from USGS. (b)–(f), Similar maps for each subsequent water year from 2019 to 2023 to illustrate annual variations.

The 2023 water year (Fig. 1f) saw another substantial shift, with many stations in the California and Colorado River Basins returning to wet conditions, while the northern regions switch to dry/critical conditions. Such fluctuations, captured through the normalized streamflow indicators, highlight the vulnerability of the Western U.S. to both hydrological droughts and surplus events, complicating water resource management and planning in the face of increasing climate variability. It is noted that the interior regions between California and lower Colorado Basins have witnessed consistently dry conditions throughout the years.

The spatial patterns of hydrological extremes shown in Fig. 1 manifest as quantifiable whiplash events tracked in Fig. 2, with both figures demonstrating the increasing frequency and severity of transitions between wet and dry conditions across the western U.S. The pronounced variability visible in the spatial mapping of conditions (Fig. 1d,f) is particularly evident in the California and Colorado River Basins, which show the most dramatic transitions between 2021 and 2023, corresponding to the violin plot distributions in Fig. 2a,b that highlight these basins’ susceptibility to whiplash events. Table 1 supports the findings presented in Fig. 2 by summarizing the number of whiplash streamflow stations from 1981 to 2023 across the Basins. The 1991–1995 period experienced the most severe hydrological transitions, with 206 stations experiencing dry-to-wet whiplash and 110 stations experiencing wet-to-dry whiplash, representing 43.9% and 23.5% of all analyzed stations, respectively. This frequency is approximately 2.5 times higher than the 2016–2020 period (81 dry-to-wet events) and 4.1 times higher than the 2006–2010 period (37 dry-to-wet events). This highlights a period of heightened hydrological instability across the Western U.S., with frequent and extreme shifts between wet and dry conditions.

Dry and wet conditions in western U.S. Basins (1981–2023) and teleconnection influences. (a) Violin plots displaying 5-year statistics of normalized streamflow data for the California Basin over 1981–2023. The central red line marks the historical mean from 1981–2020; plots below this line suggest dry conditions, while those above indicate wet conditions. The extremity of conditions is shown by the distance of each plot from this line. Blue dots represent stations with severe transitions from critically dry to wet conditions (“critical to wet whiplash”), and red dots indicate stations transitioning from wet to critically dry (“wet to critical whiplash”). Scatterplots illustrate the responses of whiplash and non-whiplash stations to changes in Western Pacific Oscillation (ΔWP) values from August of the previous year (e.g., August ΔWP2022–2021 vs. Δ Normalized Indicator2023–2022), highlighting the potential impact of teleconnections on whiplash events. Notably, the R2 value for whiplash stations (0.54) suggests a stronger response than non-whiplash stations (0.1). August was selected for analyzing the influence of the WP based on lag correlation analysis showing the strongest teleconnection signal with subsequent water year streamflow approximately 1–2 months before the water year begins. This timing coincides with late summer atmospheric circulation patterns that often establish conditions for the upcoming wet season. (b) Similar analysis for the Colorado River Basin showing influence of August ΔWP. (c) Analysis for the Columbia River Basin, with scatterplots focused on September Eastern Pacific/Northern Pacific Oscillation (ΔEPO) impacts. EPO in September was specifically analyzed for the Columbia River Basin because this basin shows unique sensitivity to early fall atmospheric circulation patterns over the northeastern Pacific. Our analysis of lag correlations revealed that September EPO configurations have the strongest predictive relationship with Columbia Basin streamflow in the following water year. This timing is critical as it coincides with the initial establishment of winter storm tracks that predominantly affect the northern portion of our study area. (d) As in panel (a) and (b) but for the Great Basin, with scatterplots reflecting the influence of August ΔWP changes on streamflow conditions.

In the California Basin (Fig. 2a), the data show considerable variability, with pronounced wet and dry streamflow extremes occurring over multiple periods. The scatterplot plots illustrate the influence of teleconnections, such as changes in ΔWP from the summer (August), on streamflow variability in the following water year. The stronger response observed in whiplash stations (red and blue dots), indicated by a higher R2 value (0.54), suggests that these extreme shifts are more sensitive to climatic drivers compared to non-whiplash stations. Similarly, the Colorado River Basin (Fig. 2b) exhibits notable shifts between wet and dry conditions, with ΔWP moderately influencing whiplash events (R2 = 0.22).

The Columbia River Basin (Fig. 2c) displays a different pattern, highlighting the negative impact of the ΔEPO in September. The scatterplots indicate that whiplash events in this basin are also significantly influenced by teleconnection patterns, with higher R2 values (0.44) for whiplash stations compared to non-whiplash stations (R2 = 0.08). In the Great Basin (Fig. 2d), August ΔWP also significantly influences streamflow conditions, with whiplash events showing a particularly strong response. The high R2 value (0.66) for whiplash stations underscores the heightened sensitivity of this basin to climatic variability, emphasizing the challenges posed by rapid transitions between hydrological extremes. These substantial disparities in R2 values indicate that stations prone to hydrological whiplash are significantly more responsive to teleconnection patterns than stations with more stable hydrology.

Teleconnection influences on whiplash events

Having established the patterns of hydrological whiplash events, it is needed to examine their atmospheric drivers through teleconnection relationships, building on the basin-specific correlations identified in Fig. 2. While Fig. 2 demonstrates the heightened sensitivity of whiplash stations to specific teleconnection patterns (e.g., ΔWP in August for California Basin stations with R2 = 0.54), Fig. 3 provides a comprehensive view of all potential teleconnection influences across basins, providing a more detailed analysis of teleconnection patterns and their effects on hydrological conditions. The heatmap illustrates correlation values between changes in basin-averaged normalized indicator values and various teleconnection patterns using data from preceding months.

In the California Basin, significant correlations emerge between teleconnections and streamflow changes. ΔEPO in September correlates negatively (r = − 0.39), while ΔWP in August shows a positive correlation (r = 0.5), supporting earlier findings on WP’s role in hydrological switches. Additionally, ΔSOI in November exhibits a negative correlation (r = − 0.36), suggesting La Niña events are linked to decreased streamflow. The Colorado River Basin displays distinct relationships with atmospheric circulation patterns. ΔWP in August correlates moderately (r = 0.34), while ΔNAO in July shows a stronger positive correlation (r = 0.47). Conversely, ΔEPO in October correlates negatively (r = − 0.45), indicating its impact on reduced streamflow. The Columbia River Basin demonstrates unique responses to teleconnections. ΔSOI from June to October exhibits strong positive correlations (r > 0.4), while ΔEPO in September/October shows a negative correlation (r = − 0.52). Other ENSO-related indices (e.g., NINO3, NINO4, ONI) correlate negatively with streamflow changes, indicating increased streamflow during La Niña conditions. In the Great Basin, ΔAO in August correlates positively (r = 0.43), highlighting its influence on hydrological conditions. Conversely, ΔEPO in September shows a negative correlation (r = − 0.44), suggesting higher EPO values are associated with drier conditions in this region.

Seasonal teleconnection influences on change of hydrological condition. Heatmap shows Pearson correlation values between changes in basin-averaged normalized indicator values and changes in climate indices from the preceding year, aggregated by month. Statistically significant correlations (p < 0.05) are displayed in bold font, enabling clearer identification of robust teleconnection relationships.

These findings reveal substantial shifts in hydrological dynamics across the Western U.S., characterized by increasing streamflow variability and more frequent whiplash events. The study emphasizes the potential influence of teleconnection patterns, such as the WPO and EPO, on the occurrence of these extreme events. The WP pattern, a key mode of low-frequency variability over the North Pacific, amplifies precipitation variability in the region34,35. Its positive phase brings above-average precipitation to high latitudes and below-average precipitation to central areas, particularly during winter and spring36. Similarly, the EPO pattern influences weather patterns; its positive phase shifts the Pacific jet stream southward, enhancing anticyclonic circulation over western North America and reducing temperatures in the central North Pacific and eastern North America37.

As seen in Fig. 3, the ENSO has a strong impact on the Columbia River Basin, where northern Pacific conditions modulate its streamflow in the Snake River headwaters38. NSO also affects streamflow variability in regions near the Pacific Ocean39. Other influential climate oscillations, including PDO and NAO, could interact with ENSO, modulating its effects on streamflow across the contiguous United States40. In the northern Pacific coastal temperate rainforest, ENSO and PDO impact streamflow timing, particularly during snowmelt and autumn rainfall periods41. The Arctic Oscillation also influences freshet flows through temperature and precipitation anomalies41.

Concerning incorporating teleconnection patterns for hydroclimate projection14, examined seasonal forecasts of precipitation, temperature, and snow mass in the western U.S. by integrating ensemble post-processing with empirical ocean-atmosphere teleconnections. Their results showed that incorporating climate indices through linear regression improved forecast accuracy, underscoring the importance of teleconnections in predicting hydrological conditions. However, long-term Pacific Ocean variability and its impact on the Western U.S. hydroclimate, as explored by42. Their findings suggest that the inherent statistics of the observable system can produce century-long periods with a wide range of correlations to Southwest U.S. hydroclimate, including nonsignificant correlations.

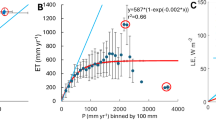

Intraseasonal teleconnections among MJO, streamflow, and atmospheric river

These basin-specific teleconnection influences illustrated in Figs. 2 and 3 establish the foundation for understanding the broader climate patterns that drive hydrological extremes in the western U.S. Building on these seasonal to annual relationships, this session next explore how intraseasonal oscillations further modulate streamflow and precipitation delivery mechanisms. Figure 4 introduces the combined intraseasonal teleconnections of the MJO on wet hydrological conditions (averaged normalized indicator > 0) in the California Basin. Figure 4a and b present scatterplots showing the relationship between wet year streamflow conditions and the sum of amplitudes for days when the MJO is in Phases 2/3 and 6/7 from October to December, respectively. Notably, in MJO Phases 2/3 (Fig. 4a), there is a clear positive relationship (R2 = 0.27), indicating that increased daily amplitudes of these phases correspond to wetter hydrological conditions, particularly during moderate to strong El Niño years, as indicated by the red-colored points with ONI as active El Nino phase (e.g., 1995, 1998). Conversely, Fig. 4b shows a negative relationship for MJO Phases 6/7 (R2 = 0.24). Figure 4c,d provide similar analyses for the January to March period. A weak negative trend is observed in MJO Phases 2/3 (Fig. 4c) (R2 = 0.1), suggesting a limited influence on streamflow during this period. Likewise, Fig. 4d shows that MJO Phases 6/7 have an even weaker relationship with wet conditions (R2 < 0.01), indicating minimal impact from January to March.

Combined MJO and ENSO sub-seasonal teleconnections on wet hydrological conditions (averaged normalized indicator > 0) in California. (a) Scatterplots with regression lines showing the relationship between basin-average wet year streamflow conditions and the sum of amplitudes for days when the MJO is in Phases 2 and 3 from October to December. The size of the points represents the number of days of Phases 2 and 3. (b) Similar to panel (a) but for MJO Phases 6 and 7. (c) Similar to panel (a) but for January to March. (d) Similar to panel (c) but for MJO Phases 6 and 7.

Figure 5 illustrates the combined influence of the MJO and ENSO on dry hydrological conditions (lower than the historical average level) in California. Figure 5a and b indicate that MJO Phases 2/3 and Phases 6/7 from October to December have limited or negligible effects on dry streamflow conditions, with weak trends (p > 0.05). Figure 5c and d show similar analyses for January to March, where MJO Phases 2/3 have no significant impact, while Phases 6/7 exhibit a minor negative trend (p = 0.166, R2 = 0.04), indicating a slight but minimal influence on dry conditions. Figures S1 and S2 present the same analysis for the Pacific Northwest. Similar to what is presented in Fig. 5, the results suggest the minimal influence of MJO phases (p > 0.05, R2 < 0.01) on streamflow in the Pacific Northwest, regardless of the wet or dry hydrological conditions.

Combined MJO and ENSO sub-seasonal teleconnections on dry streamflow conditions (averaged normalized indicator < 0) in California. (a) Scatterplots with regression lines showing the relationship between basin-average wet year streamflow conditions and the sum of amplitudes for days when the MJO is in Phases 2 and 3 from October to December. The size of the points represents the number of days of Phases 2 and 3. (b) Similar to panel (a) but for MJO Phases 6 and 7. (c) Similar to panel (a) but for January to March. (d) Similar to panel (c) but for MJO Phases 6 and 7.

The seasonal dependence of MJO influences is evident when comparing the significant correlations observed in October–December with the weaker relationships in January–March. This seasonal variation creates an important context for understanding the physical mechanisms linking atmospheric teleconnections with precipitation delivery via atmospheric rivers, as explored in Figs. 6 and 7. Figure 6 shows the analysis of the relationships between AR and various MJO characteristics for California, focusing on the October to December period. AR length represents the total number of hours for which AR-induced precipitation occurred. Figure 6a,c show scatterplots depicting AR length correlations with MJO total count of days, mean amplitude, and maximum amplitude, respectively, for MJO Phases 2/3. Figure 6a shows a significant positive correlation between AR length and MJO Phase 2/3 total count (R2 = 0.199, r = 0.446, p = 0.005), suggesting that increased MJO activity in these phases is associated with more AR events.

Figure 6b and c display a weak correlation between AR length and mean and max amplitude, suggesting minimal impact. Figure 6d–f show similar analyses for MJO Phases 6/7. Figure 6d,e also present minimal impact by the weak correlation between AR length, total count, and mean amplitude. Finally, Fig. 6f shows a significant negative correlation between AR length and maximum amplitude of MJO Phases 6/7 (R2 = 0.165, r = − 0.406, p = 0.011), suggesting that the larger MJO amplitudes in these phases may contribute to shorter AR-induced precipitation events. These findings emphasize the complexity of sub-seasonal interactions between MJO phases and AR characteristics, which likely contribute to the variability of precipitation events in California from October to December.

During January to March, for Phases 2/3, as shown in Fig. 7a,c, weak correlations are observed between AR length and total count, mean amplitude, and maximum amplitude (R2 = 0.016–0.041, p > 0.2), suggesting minimal influence of MJO activity on AR duration. Similarly, for Phases 6/7, as shown in Fig. 7d,f, AR length also exhibits weak negative correlations with the total count, mean amplitude, and maximum amplitude (R2 = 0.025–0.053, p > 0.16), indicating the limited impact of MJO Phases on AR length during the January to March.

Figures S3 and S4 present the same analysis for the Pacific Northwest from January to March and October to December, respectively. For MJO Phases 2/3, both figures show weak correlations between AR length and total count, mean amplitude, and maximum amplitude, with R2 values below 0.015. Similarly, MJO Phases 6/7 exhibit weak to moderate correlations across both periods, with the strongest correlation observed for the total count from October to December (R2 = 0.057, r = − 0.239, p = 0.149). Overall, these results suggest a minimal influence of MJO phases on AR length in the Pacific Northwest, regardless of the season.

Reference14 mentioned that MJO and ENSO are interacting in driving the compound hydrometeorological extremes in the western U.S. and very complex relationship between large-scale climate patterns and extreme events. Furthermore, Ref.13 stated observational evidence of the MJO’s influence on the intensity, frequency, and duration of precipitation extremes in the western U.S. They reported that much of the region observed significantly more precipitation extremes when the MJO was in western Pacific phases during the extended boreal winter, often from late autumn to early winter—specifically in California. The seasonality of MJO impacts can be characterized by differences in amplitude and spatial patterns of the MJO and background atmospheric states, which tend to be weaker and more northwestward in October-December than in January-March. The interaction between overturning western Pacific MJO introduces Rossby waves, as well as the influence of ENSO, amplifier or reducing the rainfall patterns, which results in elusive anomalies beyond what can be usually be expected of ENSO precipitation signals43.

Our analysis found combined MJO-ENSO effects on streamflow conditions in the Pacific Southwest from October to December, with less pronounced impacts in the Northwest and during other seasons. Our study provides additional insights into how the MJO modulates the effects of other large-scale climate patterns, offering valuable context for understanding similar interactions in the western U.S. Quantitatively, our analysis revealed distinct seasonal and regional variations in MJO-related teleconnections. During October-December, MJO Phases 2/3 explained 27% of the variance in wet conditions in California (R2 = 0.27, p = 0.002), with the effect particularly pronounced during El Niño years when the normalized indicator increased by up to 0.32 above the historical mean. For atmospheric rivers, the total count of days in MJO Phases 2/3 showed the strongest relationship with AR length (R2 = 0.199, p = 0.005), with each additional day in these phases associated with approximately 4.8 h of additional AR-induced precipitation. Conversely, MJO Phases 6/7 showed a negative relationship with AR length, particularly when examining maximum amplitude (R2 = 0.165, p = 0.011), with each unit increase in amplitude associated with approximately 27.5 fewer hours of AR activity. These numerical relationships provide important quantitative benchmarks for potential predictive applications.

Scatter plots depict the relationships between AR Length (hours of AR-induced precipitation) and various MJO characteristics for California from October to December. Panels (a–c) show AR Length correlations with MJO Total Count, Mean Amplitude, and Max Amplitude, respectively, for MJO phases 2 and 3. Panels (d–f) display corresponding correlations for MJO phases 6 and 7. Linear regression lines with shaded confidence intervals are included with the R2 values, correlation coefficients (r), and p-values.

Scatter plots depict the relationships between AR Length (hours of AR-induced precipitation) and various MJO characteristics for California from January to March. Panels (a–c) show AR Length correlations with MJO Total Count, Mean Amplitude, and Max Amplitude, respectively, for MJO phases 2 and 3. Panels (d–f) display corresponding correlations for MJO phases 6 and 7. Linear regression lines with shaded confidence intervals are included with the R2 values, correlation coefficients (r), and p-values.

Future precipitation among the scenarios

Having established the historical patterns and drivers of hydrological whiplash events, we now examine future projections of precipitation variability that may influence the frequency and intensity of these events under different climate change scenarios. The teleconnection patterns identified in Figs. 2 and 3 and the seasonal mechanisms revealed in Figs. 4, 5, 6 and 7 provide the foundation for interpreting future precipitation projections presented in Figs. 8 and 9. The nonstationary and volatile nature of future precipitation primarily influences drivers of an extreme future. Figures S5 to S7 and Fig. 8 present comprehensive projections of precipitation trends across Western U.S. basins under different climate scenarios from CIMP5 and CMIP6, focusing on the mean, median, skewness, and coefficient of variance of basin-wide precipitation, respectively.

Figure S5 highlights 40-year moving means of precipitation. Across all basins, precipitation is projected to increase, with the strongest upward trends under the high-emission RCP 8.5 and SSP5-8.5 scenarios. The Great Basin shows the highest rate of change, with a significant projected increase of 0.9 mm/year for 2061–2100 under SSP5-8.5. There are also noted differences between the CMIP5 and CMIP6 projections concerning the annual precipitation, as presented in the Colorado River Basin and Great Basin, that the CMIP6 (SSPs) holistically have higher values than those from CMIP5 (RCPs). Figure S6, which shows the 40-year moving medians of precipitation, reinforces these trends, where the Great Basin also shows the highest rate of change (0.84 mm/year) for 2061–2100 under SSP5-8.5.

Figure S7 focuses on skewness, which measures the asymmetry of precipitation distributions, indicating the extent to which extreme wet or dry conditions dominate. In the California Basin, all scenarios show a decline in skewness, with the sharpest decrease for 2020–2060 under RCP 8.5 at − 9.2e− 03 /year, indicating a shift away from extreme wet/dry events. This trend, however, reverses after the 2060s with a rate of 4.9e− 03 /year, indicating an increase in extreme events. Other basins show mixed results, with RCP 8.5 indicating a significant reduction of -2.2e− 03 1/year in the Far Future period.

Figure 8 focuses on the volatility of future precipitation, represented by the 40-year moving CV for basin-wide precipitation under the four climate scenarios. The coefficient of variation provides insights into the expected variability in precipitation, indicating how nonstationary and volatile future conditions might become. In Fig. 8a, the California Basin shows an abrupt increasing CV for RCP 8.5 after the 2060s, indicating higher volatility in precipitation patterns, with an increasing rate of 1e− 3/year. The Colorado River Basin (Fig. 8b) also shows higher variability under RCP 8.5 than other scenarios in the 2020–2040 s, suggesting enhanced near-future instability in hydrological conditions, also seen in the Great Basin (Fig. 8d). Figure 8c shows that the Columbia River Basin is also expected to experience the most significant increase in precipitation volatility, particularly under warmer (SSP5-8.5 and RCP 8.5) than moderate (SSP2-4.5 and RCP 4.5) warming scenarios.

The basin-averaged volatility trends quantified in Fig. 8 manifest geographically as shown in Fig. 9, where spatial patterns of precipitation variability reveal consistent intensification under high-emission scenarios. The maps in Fig. 9 show substantial spatial variability in precipitation volatility, indicated by CV, across Western U.S. basins under different climate scenarios. Southern regions, particularly southern California and the Colorado River Basin, display higher CV values, indicating greater volatility, especially under CMIP5 scenarios (RCP 4.5 and RCP 8.5). This volatility is most pronounced in the far future (2060–2100), with darker red areas reflecting increased variability. The extreme scenario RCP 8.5 shows the highest CV values, concentrated primarily in the southern areas, emphasizing the role of emissions in affecting hydrological stability. The temporal trend between 2020 and 2060 and 2060–2100 reveals a northward expansion of high-variability zones, particularly under high-emission scenarios. However, under the extreme scenario SSP5-8.5, variability is projected to decrease in 2060–2100 compared to 2020–2060, suggesting differing projections between CMIP5 and CMIP6 models.

Projected precipitation volatility under climate change scenarios in western U.S. Basins. (a) This panel illustrates the 40-year moving coefficient of variation for basin-wide precipitation in the California Basin, spanning from 1980–2020 to 2060–2100, under four climate scenarios: CMIP5 RCP 4.5, RCP 8.5, CMIP 6 SSP 2-4.5, and SSP 5-8.5. Solid lines depict the mean values of all models for each scenario, with shaded areas representing 95% confidence intervals. Each point on these lines represents the coefficient calculated over a 40-year window (e.g., the 2020 point shows the coefficient for 1981–2020). Trends for the Near Future (slope between 1981–2020 and 2021–2060) and Far Future (slope between 2021–2060 and 2061–2100) are plotted in terms of annual rate change in the coefficient of variation, with symbols denoting statistical significance ): ns (not significant, p > 0.05), * (p ≤ 0.05), ** (p ≤ 0.01), *** (p ≤ 0.001), and **** (p ≤ 0.0001). (b–d, As in panel (a) but for (b) the Colorado River Basin, (c) the Columbia River Basin, and (d) the Great Basin.

Spatial distribution of precipitation volatility in the Western U.S. basins for near-term (2020–2060) and far-term future (2060–2100) under four climate scenarios: CMIP5 RCP 4.5, RCP 8.5, and CMIP6 SSP2-4.5, SSP5-8.5. CV is used to illustrate variability in precipitation. Higher CV values (red areas) indicate increased volatility and uncertainty in precipitation patterns. Panels a-d represent RCP scenarios, while panels e-h represent SSP scenarios for the same timeframes.

The changing precipitation patterns indicate significant shifts in the variability and predictability of future streamflow dynamics. Our analysis of future precipitation trends reveals increasing variability in some CMIP5 and CMIP6 model ensemble scenarios. These changes may lead to more frequent and severe “wet” and “critically dry” years, creating challenges for hydrological management and planning in the western U.S. Increasing hydroclimate variability challenges traditional water management, emphasizing the need to account for both natural climate variability and global warming44.

The discrepancies between CMIP5 and CMIP6 projections, especially in the California Basin toward the late 21st century, suggest a need to reevaluate the use of RCP scenarios, particularly RCP 8.5, given its widespread application in both policy-making45 and academic research46. A recent study showed CMIP6 climate model projections exhibit reduced uncertainty compared to CMIP5 for temperature, precipitation, and hydrological impacts across North America47. However, some CMIP6 models display a “hot model” issue, characterized by high equilibrium climate sensitivity (ECS) or transient climate response (TCR) values, which exceed the “assessed warming” established by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Sixth Assessment Report (AR6) and other studies48,49,50,51. This necessitates further investigation into the differences between CMIP5 and CMIP6 projections and the impact of these “hot models” on future water availability in the western U.S.

These findings have broader implications beyond the western U.S. The identification of specific teleconnection patterns as whiplash precursors suggests potential for developing early warning systems in regions with similar ocean-atmosphere dynamics. Our analysis has limitations worth noting: we focused primarily on natural streamflow variability without fully accounting for human modifications to hydrological systems; our teleconnection analysis was limited to seasonal-to-annual timescales; and future projections rely on climate models with known limitations in representing regional extremes. Future research should incorporate water management factors, investigate higher-frequency whiplash events, develop targeted forecasting models, and explore compound climate extremes52. Extending this methodology to other teleconnection-influenced regions could validate the generalizability of our findings and contribute to a global understanding of hydrological whiplash mechanisms.

Conclusion

This study comprehensively analyzes hydrological whiplash events and their relationship to atmospheric teleconnection patterns in the Western United States. Our examination of 469 streamflow stations from 1981 to 2023 reveals the frequency and intensity of hydrological whiplash events, with a peak of 206 stations experiencing dry-to-wet transitions in the early 1990s. We also identified strong correlations between streamflow variability and climate oscillations, particularly the WP and EPO patterns. For example, the August ΔWP demonstrates R2 values of 0.54 and 0.66 for whiplash-affected stations in the California and Great Basin regions, respectively. The MJO also has a significant influence on streamflow, with MJO Phases 2/3 showing a positive correlation (R2 = 0.27) with wet conditions in the Pacific Southwest from October to December. Our analysis of future precipitation patterns using CMIP5 and CMIP6 models projects increased variability across the Western U.S. under the SSP5-8.5 scenario. California, in particular, is expected to experience heightened volatility, with a sharp rise in the coefficient of variation after the 2060s under SSP5-8.5.

The significance of this study lies in its detailed approach to understanding the complex dynamics of hydrology in the Western U.S. By linking large-scale atmospheric patterns to local hydrological extremes and projecting future scenarios, this research provides critical insights for water resource managers and policymakers. These findings are essential for developing adaptive strategies to ensure water security amidst increasing climate variability and change.

Data availability

The authors declare that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its Supplementary Information files. The raw data used in this study are publicly available from the following sources: (1) USGS streamflow data: https://waterdata.usgs.gov/nwis, (2) NOAA teleconnection indices: https://psl.noaa.gov/data/climateindices/, (3) MJO indices: http://www.bom.gov.au/climate/mjo/, (4) Atmospheric River data: https://cw3e.ucsd.edu/AR_Catalog/, and (5) NASA-NEX GDDP climate projections: https://www.nasa.gov/nex-gddp/. Additionally, we have created a public repository on Zenodo Repository (https://zenodo.org/records/12575692) containing analysis scripts necessary to reproduce the figures and results presented in this study. The repository includes detailed documentation to guide users through the data processing steps and analytical procedures.

References

Lins, H. F. Regional streamflow regimes and hydroclimatology of the United States. Water Resour. Res. 33, 1655–1667 (1997).

Meko, D. & Stockton, C. W. Secular variations in streamflow in the western United States (1984).

Konrad, C. P. Seasonal precipitation influences streamflow vulnerability to the 2015 drought in the Western United States. J. Hydrometeorol. 20, 1261–1274 (2019).

Jain, S., Woodhouse, C. A. & Hoerling, M. P. Multidecadal streamflow regimes in the interior Western united states: implications for the vulnerability of water resources. Geophys. Res. Lett. 29, (2002).

Cayan, D. R. & Peterson, D. H. The Influence of North Pacific atmospheric circulation on streamflow in the West. In Aspects of Climate Variability in the Pacific and the Western Americas, 375–397 (American Geophysical Union, 2013).

Lo, M. & Famiglietti, J. Irrigation in california’s central Valley strengthens the Southwestern U.S. Water cycle. Geophys. Res. Lett. 40, 301–306 (2013).

Huang, W. T. K. et al. Economic valuation of temperature-related mortality attributed to urban heat Islands in European cities. Nat. Commun. 14, 7438 (2023).

Leung, L., Qian, Y., Bian, X. & Hunt, A. Hydroclimate of the Western United States Based on Observations and Regional Climate Simulation of 1981–2000. Part II (Mesoscale ENSO Anomalies, 2003).

Piechota, T. C., Dracup, J. A. & Fovell, R. G. Western US streamflow and atmospheric circulation patterns during El Niño-Southern Oscillation. J. Hydrol. 201, 249–271 (1997).

Chang, J., Zhang, H., Wang, Y. & Zhu, Y. Assessing the impact of climate variability and human activities on streamflow variation. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 20, 1547–1560 (2015).

Dey, P. & Mishra, A. Separating the impacts of climate change and human activities on streamflow: A review of methodologies and critical assumptions. J. Hydrol. 548, 278–290 (2017).

NOAA. United States El. Niño Impacts | NOAA Climate.gov. https://www.climate.gov/news-features/blogs/enso/united-states-el-ni%C3%B1o-impacts-0 (2014).

Wang, J., DeFlorio, M. J., Guan, B. & Castellano, C. M. Seasonality of MJO impacts on precipitation extremes over the Western united States. J. Hydrometeorol. 24, 151–166 (2023).

Wang, J. et al. Association of Western US compound hydrometeorological extremes with Madden-Julian Oscillation and ENSO interaction. Commun. Earth Environ. 5, 314 (2024).

Svoma, B. M. El Niño-Southern Oscillation and snow level in the western United States: ENSO AND SNOW LEVEL. J. Geophys. Res. 116, (2011).

Zhou, W., Yang, D., Xie, S. P. & Ma, J. Amplified Madden–Julian Oscillation impacts in the Pacific–North America region. Nat. Clim. Chang. 10, 654–660 (2020).

Barth, N. A., Villarini, G., Nayak, M. A. & White, K. Mixed populations and annual flood frequency estimates in the Western united states: the role of atmospheric rivers. Water Resour. Res. 53, 257–269 (2017).

Jain, S., Hoerling, M. & Eischeid, J. Decreasing reliability and increasing synchroneity of Western North American streamflow. J. Clim. 18, 613–618 (2005).

2021 SECURE Water Report | Bureau of Reclamation. https://www.usbr.gov/climate/secure/2021secure.html.

Regonda, S. K., Rajagopalan, B., Clark, M. & Pitlick, J. Seasonal cycle shifts in hydroclimatology over the Western United States. J. Clim. 18, 372–384 (2005).

Luce, C. H. & Holden, Z. A. Declining annual streamflow distributions in the Pacific Northwest United states, 1948–2006. Geophys. Res. Lett. 36, (2009).

Safeeq, M., Grant, G. E., Lewis, S. L. & Tague, C. L. Coupling snowpack and groundwater dynamics to interpret historical streamflow trends in the Oregon cascades. Clim. Change. 86, 189–210 (2008).

Siirila-Woodburn, E. R. et al. A low-to-no snow future and its impacts on water resources in the Western United States. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2, 800–819 (2021).

California Department of Water Resources. California water plan update 2023. Retrieved from https://water.ca.gov/Programs/California-Water-Plan/Update-2023 (2024).

Facincani Dourado, G., Rheinheimer, D. E., Abaztoglou, J. T. & Viers, J. H. Stress testing California’s hydroclimatic whiplash: potential challenges, trade-offs and adaptations in water management and hydropower generation. Water Resour. Res. 60, e2023WR035966 (2024).

Madrigal, C. et al. Water whiplash in mediterranean regions of the world. Water. 16, 450 (2024).

Li, W., Maharjan, S., Fisher, J. B., Piechota, T. & El-Askary, H. Escalating hydrological extremes and whiplashes in the Western U.S.: Challenges for water management and frontline communities. Earth’s Future. 13, e2024EF005447 (2025).

Climate Indices. Monthly Atmospheric and Ocean Time Series: NOAA Physical Sciences Laboratory. https://psl.noaa.gov/data/climateindices/

Madden-Julian Oscillation (MJO) monitoring. http://www.bom.gov.au/climate/mjo/

Gershunov, A., Shulgina, T., Ralph, F. M., Lavers, D. A. & Rutz, J. J. Assessing the climate-scale variability of atmospheric rivers affecting Western North America. Geophys. Res. Lett. 44, 7900–7908 (2017).

Thrasher, B., Maurer, E. P., McKellar, C. & Duffy, P. B. Technical note: Bias correcting climate model simulated daily temperature extremes with quantile mapping. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 16, 3309–3314 (2012).

California Department of Water Resources (CDWR) (1989), Bay-Delta Estuary Proceedings Water Year Classification Workgroup, San Joaquin River Index, Summary of Workshop Activities, California Department of Water Resources.

California Department of Water Resources (CDWR) (1991), Bay-Delta Estuary Proceedings Water Year Classification Sub-Workgroup, Summary of Workshop Activities, California Department of Water Resources.

Barnston, A. G. & Livezey, R. E. Classification, seasonality and persistence of low-frequency atmospheric circulation patterns. Mon. Weather Rev. 115, 1083–1126 (1987).

Wallace, J. M. & Gutzler, D. S. Teleconnections in the geopotential height field during the Northern hemisphere winter. Mon. Weather Rev. 109, 784–812 (1981).

Climate Prediction Center—West Pacific (WP). https://www.cpc.ncep.noaa.gov/data/teledoc/wp.shtml.

Climate Prediction Center - East Pacific—North Pacific. (EP-NP). https://www.cpc.ncep.noaa.gov/data/teledoc/ep.shtml.

Wise, E. K. Climate–Streamflow linkages in the North-Central Rocky mountains: implications for a changing climate. Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 100, 806–817 (2010).

Bhandari, S., Kalra, A., Tamaddun, K. & Ahmad, S. Relationship between Ocean-Atmospheric climate variables and regional streamflow of the conterminous united States. Hydrology. 5, 30 (2018).

Singh, S., Abebe, A., Srivastava, P. & Chaubey, I. Effect of ENSO modulation by decadal and multi-decadal Climatic oscillations on contiguous united States streamflows. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 36, 100876 (2021).

Fleming, S. W., Hood, E., Dahlke, H. E. & O’Neel, S. Seasonal flows of international British Columbia-Alaska rivers: the nonlinear influence of ocean-atmosphere circulation patterns. Adv. Water Resour. 87, 42–55 (2016).

Evans, C. P. et al. Intrinsic century-scale variability in tropical Pacific Sea surface temperatures and their influence on western US hydroclimate. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49, e2022GL099770 (2022).

Arcodia, M. C., Kirtman, B. P. & Siqueira, L. S. P. How MJO teleconnections and ENSO interference impacts U.S. precipitation. J. Clim. 33, 4621–4640 (2020).

Gangopadhyay, S. & McCabe, G. Predicting regime shifts in flow of the Colorado river. Geophys. Res. Lett. 37, (2010).

Kalansky, J. et al. California’s fourth climate change assessment. (2018).

Swain, D. L., Langenbrunner, B., Neelin, J. D. & Hall, A. Increasing precipitation volatility in twenty-first-century California. Nat. Clim. Change. 8, 427–433 (2018).

Martel, J. L. et al. CMIP5 and CMIP6 model projection comparison for hydrological impacts over North America. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49, e2022GL098364 (2022).

Hausfather, Z., Marvel, K., Schmidt, G. A., Nielsen-Gammon, J. W. & Zelinka, M. Climate simulations: recognize the ‘hot model’ problem. Nature. 605, 26–29 (2022).

Li, W., Li, D., El-Askary, H., Fisher, J. B. & Fang, Z. N. Evaluating future water availability in Texas through the lens of a data-driven approach leveraged with CMIP6 general circulation models. Sci. Total Environ. 921, 171136 (2024).

Nijsse, F. J. M. M., Cox, P. M. & Williamson, M. S. Emergent constraints on transient climate response (TCR) and equilibrium climate sensitivity (ECS) from historical warming in CMIP5 and CMIP6 models. Earth Syst. Dyn. 11, 737–750 (2020).

Tokarska, K. B. et al. Past warming trend constrains future warming in CMIP6 models. Sci. Adv. 6, eaaz9549 (2020).

Maharjan, S. et al. Unfolding cascading impacts of changing South Asia monsoon on a Hindu Kush Himalayas basin. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 57, 102155 (2025).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the support from the US Department of Education award number P116Z220190, “Earth Systems Science and Data Solutions Lab (EssDs): Applying Data Science Techniques to Achieve the UN Sustainable Development Goals”. The authors also acknowledge Dr. Cyril Rakovski from Chapman University for his comments on this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

W.L. led the research, performed the primary analyses, and drafted the manuscript. S.M. contributed to data visualization, supported the analysis, and assisted in manuscript preparation. H.E.-A. secured funding, provided project oversight and supervision, and critically reviewed and revised the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, W., Maharjan, S. & El-Askary, H. Atmospheric teleconnection patterns and hydrological whiplashes in the Western U.S.. Sci Rep 15, 21262 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-06087-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-06087-6

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

The future intensification of hydrological extremes and whiplashes in the contiguous United States increase community vulnerability

Communications Earth & Environment (2025)