Abstract

The coordinated movement of fish schools has long captivated researchers studying animal collective behavior. Classical literature from Weihs and Lighthill suggests that fish schools should favor planar diamond formations to increase hydrodynamic efficiency, inspiring a large body of work ranging from fluid simulations to hydrofoil experiments. However, whether fish schools actually adopt and maintain this idealized formation remains debated and unresolved. When fish schools are free to self-organize in three dimensions, what formations do they prefer? By tracking polarized schools of giant danios (Devario aequipinnatus) swimming continuously for ten hours, we demonstrate that fish rarely stay in a horizontal plane, and even more rarely, in the classical diamond formation. Of all fish pairs within four body-lengths from each other, only 25.2% were in the same plane. Of these, 54.6% were inline, 30.0% were staggered, and 15.4% were side-by-side. The diamond formation was observed in less than 0.1% of all frames. Notably, a vertical “ladder formation” emerged as the most probable formation for schooling giant danios, appearing in 79% of all fish pairs, and it elongated at higher swimming speeds. These findings highlight the dynamic and three-dimensional nature of fish schools and suggest that hydrodynamic benefits may be obtained without maintaining fixed formations. This research provides a foundation for future studies that examine the hydrodynamics and control of underwater collectives in 3D formations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Fish schooling is a common and classical collective behavior. It has been estimated that 50% of fish species form schools as juveniles and 25% form schools throughout their life1. Recent experimental studies have demonstrated that schooling behavior allows fish to save up to 53% of metabolic energy compared to swimming by themselves2. One potential cause of this energetic saving is the complex hydrodynamic interaction between fish and their surrounding fluid environment, an intriguing problem that dates back to the 1970s, when applied mathematicians Weihs3 and Lighthill4 theorized that a planar diamond formation is both energy-saving and self-stabilizing. Using potential flow theory in fluid mechanics, they argued that this formation would allow a trailing fish to avoid the jet produced by its leaders and swim in a reduced flow region. Furthermore, assuming synchronized kinematics, the side-by-side fish pairs in this formation would have an increased hydrodynamic efficiency.

While the diamond formation has inspired a diversity of work using simulations, hydrofoils, and underwater robots5, hydrodynamic benefits of other formations have also been proposed5. Indeed, whether fish schools adopt the diamond formation at all remains highly debated6, and experimental studies have yielded conflicting results7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14 (Table 1). For example, 10showed that fish prefer a side-by-side ‘phalanx’ formation at a swimming speed of around 4 body-lengths per second. 12demonstrated that rainbowfish (Melanotaenia) favor inline formations whose spacing increases with the swimming speed.

Identifying the three-dimensional positions of multiple schooling fish swimming freely in deep water and against currents presents significant challenges even in laboratory settings. Consequently, most experimental studies of fish school formations have been limited, often conducted either in still water, using short video recordings, or in shallow water to restrict vertical movement (Table 1). Most used two to ten individuals. Without flow, it is difficult to distinguish betweeen fish positions resulting from social cohesive interactions and those leading to hydrodynamics efficiency and energy savings – a factor that becomes increasingly important as swimming speed increases2,15,16. Furthermore, fish in still water form non-polarized groups2,17, swimming intermittently with varied headings. To identify the fish school formations that provide hydrodynamic benefits and test the classical diamond formation proposed by Weihs and Lighthill3,4, it is essential to provide flow and challenge fish schools to swim actively in a common mean direction.

Previous studies on fish school behavior at higher swimming speeds also often limit their recordings to less than five minutes11,14. It remains unclear whether this provides sufficient time for schools to reach a steady formation in a laboratory setting and if school kinematics might change over a longer period. Do fish schools maintain consistent formations over hours when swimming against the flow? We address this question by recording active directional schools for ten hours, generating an unprecedented long-duration 3-D dataset that enabled comprehensive analysis of fish school formation dynamics. To ensure that fish can swim continuously for such a long period, we used a moderate speed at which fish schools exhibit the minimum cost of transport2, at approximately 2.4 body-lengths per second.

Another critical limitation in previous experiments is the lack of water depth. To facilitate automated tracking and prevent individuals from overlapping in the camera frame, fish were often confined in shallow water (Table 1). This artificial constraint forces fish schools into planar formations close to the surface and the ground, which can substantially alter flow and influence group behavior. In natural environments such as rivers and oceans, however, fish schools exhibit three-dimensional structures when provided sufficient water depth (Fig. 1). While a pair of fish may appear to be inline or staggered in a ventral view, they are often separated vertically (Fig. 1). Such three-dimensional arrangements challenge the planar assumption fundamental for the diamond formation conjecture3. However, due to the difficulties associated with automatic tracking, long-term quantitative characterization of fish school formations in three dimensions remains limited.

Fish schools adopt 3D formations both in nature and in the laboratory. Schools of (A) bluefin tuna and (B) pacific herring in 3D formations. (C–D) A small school of three giant danios with a pair (red and yellow dots) in an apparent (C) inline and (D) staggered formation when viewed from above. However, both had a significant vertical separation.

In this study, we overcome these critical limitations, combining animal experiments and computer vision to characterize the occurrence frequency of different three-dimensional fish formations. We hypothesized that the three-dimensional nature of fish schools could result in preferred formations that are non-planar, potentially challenging the assumptions of many common kinematic and hydrodynamic models used to support energy-saving resulting from planar formations. To test this, we conducted long-duration 3D recordings of small schools of giant danios (Devario aequipinnatus) swimming at 1.6 to 5.6 BL/s in a circulating flow channel. We developed a custom computer vision pipeline utilizing deep neural networks to extract the 3D coordinates of all fish in the schools. This combined approach allowed us to directly test the diamond formation conjecture and explore the preferred formations of giant danio in three dimensions.

Results

A machine vision pipeline for tracking fish schools in 3D. (A) A photo and (B) a schematic of the experimental setup. Note that the danio schools swam within a mesh chamber suspended within a recirculating flow tank that greatly reduced boundary layer effects (see Methods and Supplemental Information). (C) Histograms of both yaw \(\phi\) and pitch \(\alpha\), centering around zero, i.e. aligning with the flow. (D) A diagram of the video-processing pipeline. (E) a two-minute sequence of the coordinates for the nose of all six fish within a school. Different colors represent different individuals.

We placed schools of six giant danio in a chamber 8.8 times the height of a fish (\(\sim\)1.9 BL)(Fig. 2A–B). Bounded by a mesh net and located at the center of a recirculating flow tank, the chamber minimizes the effects of fluid boundary layers, as verified by particle imagery velocimetry (PIV) (Fig. S1). A flow of 2.4 body-lengths per second (BL/s) polarized the schools, reducing the mean pitch \(\alpha\) and yaw \(\phi\) angles to near zero (Fig. 2C), while ensuring that fish sustained steady-state swimming for the full duration of the experiments (ten hours). The fish schools were recorded from both side and bottom views. For each view, we trained two neural network models using different computational architectures in SLEAP.ai (top-down and bottom-up)18 to locate the coordinates of each fish’s nose (Fig. 2D). A custom MATLAB program then integrated data from both models, removed outliers, triangulated 3D coordinates, and tracked individuals across frames over time (see Methods and Supplemental Information). Figure 2E illustrates sample 3D trajectories of six fish over a two-minute period, highlighting the detailed behavioral data collected.

Giant danio schools are transient and never planar

Fish schools are three-dimensional and transient. Time series of the (A) average fish speed with respect to the chamber, and (B) height of the school. The inset in A shows the variation over a 30-second window. Black lines represent moving averages and the gray regions represent standard deviations across 1-min-long moving windows. The transient period is marked in blue. Autocorrelation functions for (C) individual fish coordinates and (D) school volume.

We begin by demonstrating the behavior of the entire school. Figure 3A shows a time series of fish speed. Calculated as the mean 3D speed of all fish relative to the chamber (in the lab frame), this metric characterized the school’s activity in the chamber. In the first hour, fish moved relatively quickly at approximately 0.2 BL/s. Then, their speed gradually decreased until it reached a baseline of around 0.14 BL/s (N=161,977). This suggests that it takes giant danio schools an hour to adapt their behavior to the flow. Thus, we limit our following analysis to the data after the first hour. The school’s vertical structure also exhibited an initial transient period (Fig. 3B). We measured school height as the vertical separation between the noses of the highest and lowest fish. Initially, the school maintained a relatively flat formation about one body-length tall, approximately 4.8 times the average height of an individual fish. After the first hour, school height fluctuated around a mean of 1.2 body-lengths, or 5.5 times fish body height (N=161,996). Notably, the fish school was never planar: less than 0.5% of all frames showed a school flatter than 0.25 body-length, or 1.15 body-height.

Both time series (Fig. 3A–B) also demonstrate that giant danio schools are in constant motion, actively rearranging their relative positions. To characterize this transient behavior, we calculated the autocorrelation function ACF\((\tau )\), which captures how a variable measured at two time instants \(\tau\) apart correlates with itself (see Methods for details). This function typically decays from 1 at \(\tau =0\) (perfect correlation with itself) to 0 when \(\tau\) is so large that the two values are no longer correlated. The ACF for individual fish’s coordinates and the school’s volume indeed decayed with \(\tau\) (Fig. 1D–E). The de-correlation timescale (see definition in the Methods section) was around 48 seconds for individual fish and around 32 seconds for the whole school. The school’s timescale was much shorter than the individual’s because the movement of any of the six fish in the school could change the school’s volume.

Fish schools rarely form a diamond

We used our data to directly test the conjecture posed by Weihs and Lighthill3,4. This required a mathematical definition of the formation. We considered a fish quadruple to be in a diamond formation if they satisfied the following conditions (Fig. 4A):

-

The quadruple’s height \(c_0 < 0.25\) BL;

-

Its width \(c_1 < 1\) BL;

-

There exists a pair of fish side by side with streamwise separation \(c_2<0.25\) BL;

-

There exists a leader \(c_3\) and a follower \(c_4\) in front of and behind the pair.

We designed an algorithm to automatically detect the frames with diamond formations in our videos. Figure 4B shows a representative frame identified by the algorithm. A quadruple of fish in this frame closely resembles the diamond formation proposed by Weihs and Lighthill3,4. However, such frames were extremely rare in our experiments. Our video data provided 264,173 frames out of 324,000 total frames with at least four fish tracked from both views. Of these, less than 3.3 % (8,589) had at least a group of four fish in a plane (Table S1), and only less than 0.1 % (262) were diamond formations. Figure 4C shows the probability distribution of all fish around a side-by-side pair, i.e. satisfying conditions \(c_0-c_2\). The distribution of fish is almost uniform except for the region in front of the pair. Indeed, in our search, only 1.5 % of frames with four fish in a plane had a side-by-side pair and at least a leader in front. This probability is still higher than having a fish trailing the pair, at 0.8 %. The hydrodynamic benefit proposed by the diamond model requires a minimal school with at least a pair of side-by-side fish and a trailing fish. We discovered that such a scenario is extremely rare for schools of giant danios under our experimental test conditions.

Fish rarely adopt diamond formations. (A) Diamond formations require a quadruple of fish satisfying conditions relating to school height (\(c_0\)), school width (\(c_1\)), streamwise separation between the fish pair on the outside (\(c_2\)), and the presence of a leader and a follower (\(c_4\)). (B) An example of the diamond formation identified by the automated algorithm. Such frames are rare in our recordings. (C) The probability distribution of other fish next to a side-by-side fish pair.

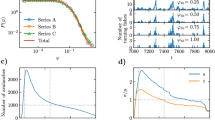

Fish most frequently adopt ladder formations in 3D

Although we never observed fish in schools maintaining any one formation for a prolonged period, a preferred unique ladder-like 3D arrangement was identified in our ten-hour-long experiments. Figure 5A, B shows the probability maps of finding a neighbor around a fish located in the middle of the plot. Bright spots indicate the most likely location of a neighbor (N=2,482,308). Figure 5A shows that a fish is likely to find a neighbor half a body-length either in front of it or behind it. The side view of this 3D heatmap (Fig. 5B) further revealed that the neighbor is likely below if in front, and above if behind. This unique ladder-like 3D arrangement can also be observed in Figs. 1C and 2A. To the knowledge of the authors, this ladder formation has never been reported, and emphasizes the importance of considering 3D schooling formations.

The probability of finding a neighbor within a cylindrical zone surrounding an individual fish was calculated (Fig. 5C). A neighbor’s relative location can be characterized by the bearing angle \(\theta\) and vertical separation \(\Delta\)z. The relative bearing angle \(\theta\) between a fish pair defines whether their formation is inline, staggered, or side-by-side while their vertical separation \(\Delta\)z determines whether they are in a plane (see methods for more detail). Figure 5D shows the distribution of \(\theta\) for all planar pairs (N=62,212). 54.1% of these fish pairs were in inline formation, with a \(\theta\) close to 0 or π. Staggered formation was the second most likely at 39.5% and side-by-side formation was the least likely at 15.5%. Overall, planar formations (|\(\Delta\)\(z|<0.25\) BL) only consisted 25.1% of all fish pairs. This result suggests that the probability for a whole school of six giant danios to be in a plane is extremely low, around (25.1%)5 0.01%. This explains why the school height remained significant in Fig. 3B.

The full heat map (Fig. 5E) reveals how most pairwise formations are offset in the vertical direction \(\Delta\)z. The most probable locations of a neighbor occur when \(\theta\) is around \(\pi\) or \(-\pi\) and \(\Delta z\) around 0.5 BL, and when \(\theta\) is around 0 and \(\Delta z\) around −0.5 BL. These locations correspond to the ladder formation shown in Fig. 5A,B. Summing all the probabilities within the brown box, ladder formations accounted for 79.0% of all formations. In contrast, only 7.6 % of all fish pairs were in planar staggered formations, a configuration where fish in diamond formations would occur. Thus, Fig. 5E again demonstrates that diamond formations rarely occur in giant danio schools.

Fish pairs prefer vertically separated ladder formations. (A) A bottom view and (B) a side view of the probability distributions of finding a neighbor next to a central fish fixed at the center of the heat map. (C) A cylindrical coordinate representation of a fish pair’s relative location. The coordinate system’s origin coincides with the fish’s nose and its axis aligns with the fish. (D) A probability distribution of a neighbor’s bearing angle \(\theta\) for all planar pairs. (E) A full probability distribution of a neighbor’s \(\theta\) and \(\Delta\)z. Brown boxes denote ladder formations while black boxes denote planar staggered formations that would be prevalent in diamond formations. The colorbar is shared for A, B, and E.

Ladder formations elongate in faster flow

We characterized how fish within schools adjust their formation as average water velocity increased from 1.6 to 5.6 BL/s. We limited the duration at each flow speed to five minutes and excluded the first minute in our analysis. The relatively short time was chosen to avoid tiring the fish and to ensure steady-state swimming. The step-wise flow-ramping procedure follows a well-established protocol2,19,20. While the school as a collective was still actively adjusting to flow in this period (Fig. 3A, B), it only took several seconds for individual fish to adapt their swimming speeds to the increased incoming flow.

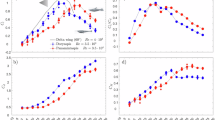

Fish pairs at all speeds adopted vertically separated formations similar to those in our 10-hour experiments at 2.4 BL/s (Fig. 4). Figure 6A shows a heatmap from the side view for schools at three representative speeds, 1.6, 3.2, and 4.8 BL/s. At the lowest speed, a majority of the fish pairs were stacked vertically. As flow speed increased, the fish on top retreated and the formation became sheared. As a result, the school elongated as the flow rate increased with a slope of 0.65 body-lengths per unit speed (BL/s)(p<0.001) (Fig. 6D). This adaptive response to flow is similar to that observed for other collective systems such as the rafts of fire ants Solenopsis invicta21.

Although schools are polarized across all speeds, the polarization is stronger at faster speeds (Fig. 6E, F). The variances in yaw \(\phi\) and pitch angles \(\alpha\) with respect to the flow decrease with the flow speed. Note that the mean of the pitch angle \(\alpha\) is slightly positive at low speed. This pitching behavior at low swimming speed has been previously described in leopard sharks (Triakis Semifasciata)22, clearnose skate (Raja eglanteria)23, rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss)23, and giant danio2, and is thought to allow fish to generate lift and maintain vertical position. Our results indicate that the same mechanism may be used in schooling giant danio.

Fish schools become more polarized and more elongated in faster flow. (A–C) Heatmaps of neighbor probability from the side view when the school swims at (A) 1.6 BL/s, (B) 3.2 BL/s, and (C) 4.8 BL/s. (D) school length L (BL) (E) yaw \(\phi\) (rad), and (F) pitch \(\alpha\) (rad) as a function of swimming speeds. School length L is defined as the distance between the noses of the second first fish and the second last..

Discussion

Here we present a 10-hour three-dimensional characterization of fish school formations. By tracking polarized schools of giant danios swimming against flow in an experimental laboratory setting, we reveal that only 25.2 % of all fish pairs are in planar formations. This includes 13.6% in inline formations, 7.6 % in staggered formations, and 3.9 % in side-by-side formations (Fig. 7). The classical diamond formation, widely cited as a preferred position for energy saving by fish within schools3,4,24, was present less than 0.1 % of the time. A significant number of fish pairs are vertically separated by more than half a body-length apart. Notably, a “ladder formation” emerged as the most probable for schooling giant danios, appearing in 79.0 % of all fish pairs.

To explore whether this ladder formation allows fish to gain hydrodynamic benefits, it is instructive to revisit the original hydrodynamic arguments for diamond formations3,4,24. Weihs argued that schooling fish would benefit from being in a horizontal diamond formation due to two hydrodynamic effects, one along the swimming direction (streamwise) and another perpendicular to the swimming direction (spanwise)3. The streamwise effect considers the fact that on average, a free-swimming fish leaves a jet behind going backwards. Thus, it is energetically unfavorable for a follower to be directly behind another fish. While fish confined in shallow water have to stagger horizontally to obtain this hydrodynamic benefit, when allowed to swim freely in all three dimensions, they can also stagger in the vertical direction, resulting in ladder formations.

The second proposed hydrodynamic benefit that fish in diamond formations could enjoy requires significant coordination among individuals. Weihs argued that if fish pairs that are side-by-side with each other beat their tails anti-phase, by symmetry, it would be as if they were beating their tails against a wall nearby, and therefore boosting their thrust3. In reality, this requirement may be difficult to satisfy. Coordinating tail beats among individuals is challenging, especially when fish are within large schools with hundreds or thousands of individuals. Phase relationships among individuals within a school often vary considerably. Furthermore, the observation that goldfish match each other’s vortex phase predicts that a side-by-side fish pair would in fact beat their tails in phase25. This suggests that the second proposed benefit of diamond formations is seldom achieved and that the ladder formation may be just as efficient as the diamond formation. Further research is required to characterize the hydrodynamic efficiencies of ladder formations and investigate how their asymmetry (follower often above the leader, Fig. 5B) may arise from fish morphology and kinematics.

A key result of this study is that fish within a school are constantly rearranging their relative positions and do not maintain any one formation for long periods of time, including even ladder formations. This result, when combined with previous direct metabolic measurements of schooling energetics in this same species2,20, raises the question: how could fish reduce their locomotive energy expenditure in a school when they are frequently changing their relative positions? The resolution of this question lies in the diverse array of formations that offer energy-saving benefits. Numerical simulations and experimental work involving live fish, flapping hydrofoils, and robotic models have revealed that energy savings occur across a wide spectrum of relative positions26,27,28, including in inline formations29,30,31,32,33, side-by-side formations34,35, staggered formations36,37,38, and rectangular formations24,39. This diversity of energy-saving positions suggests that fish schooling behavior is highly permissive in allowing a hydrodynamic energetic reduction in swimming cost even though fish in a school are in constant motion relative to each other, as demonstrated here. The previously measured energy reduction could result from the accumulation of all savings retained under each of the formations temporarily occupied. The transient nature of these formations also raises the question of hydrodynamic stability5. Are the fluid forces around swimmers in these positions balanced? Our biological data cannot fully answer this question because fish frequently adjust their tail beats as they rearrange positions. Future experiments with schools of controlled fish-like robots will provide valuable insights.

The hydrodynamic interactions between fish in three-dimensional formations such as ladder formations remain an open area of research, since previous research has focused primarily on two-dimensional formations. How does fluid flow develop and propagate around fish in ladder formations? Are energy savings enhanced when tail beats are synchronized across different formations? Recent numerical studies have already started to suggest that individual fish in a vertical formation can obtain hydrodynamic benefits40,41. In particular, a numerical study suggests that fish in vertical formations similar to ladder formations can indeed obtain hydrodynamic benefits and that the vertical spacing played a critical role40. Future studies employing numerical simulations, hydrofoil experiments, and swarm robotics will provide further insights into the mechanics of 3D fish school formations and improve our understanding of this canonical collective behavior5.

In the meantime, three-dimensional tracking of animal collectives may continue to yield exciting and fruitful discoveries, offering unprecedented insights into complex biological systems. Our computer vision pipeline contributes to this rapidly evolving landscape, complementing recent advancements such as the tracking of fireflies in their native habitat, which has unveiled crucial self-organizing mechanisms42,43, and the 3D tracking of brine shrimp movements, which has illuminated the hydrodynamic consequences of collective migration44.

To facilitate automated tracking, this study is limited in that it has a relatively small number of individuals, and the indoor laboratory setup was used to provide consistent lighting conditions for the recording, limiting the range of species that can be studied. Fish schools in the wild experience non-uniform fluid environments unlike in the laboratory setting, and predation risk may affect their self-organizing properties, such as the formation of bait balls. Indeed, the functions of fish schooling extend beyond hydrodynamic factors1. The internal structures of fish groups as they avoid predators and perform collective navigation remain open areas of research. Future research that characterizes the formations of fish schools in the wild, includes schools with more individuals, or investigates schools of larger species or other aquatic organisms, will advance our understanding of collective behavior across species and scales.

Methods

Fish care

In our experiments, we used giant danio (Devario aequipinnatus) that were 6.0 ± 0.6 cm long, 0.7 ± 0.1 cm wide, and 1.3 ± 0.1 cm tall. They were acquired from a local commercial supplier near Boston, Massachusetts, United States of America, and housed in a 37.9 L aquarium. The aquarium was equipped with a filtration system and was temperature and aeration controlled (at \(28^\circ\)C and >95% air saturation). Water changes (up to 50% exchange ratio) were carried out weekly. Fish were fed ad libitum daily (TetraMin, Germany). A school of six individuals was used for the constant-flow experiments and another school of six individuals was used in the ramping flow experiments. Experiments were only conducted during the day, after at least spending twelve hours in the dark without flow. Animal holding and experimental procedures were approved by the Harvard Animal Care IACUC Committee (protocol number 20-03-3) and this report followed the ARRIVE guidelines.

Experiments

Experiments were conducted in June 2023. A water channel (overall test channel 50 cm long, 30 cm wide, and 30 cm tall) was used to provide constant flow to the fish schools to encourage active directional schooling behavior and polarized formations. Schools were placed within a rectangular cage made with carbon fiber rods and nylon netting to form boundaries (30 cm x 11.5 x 11 cm) located within the test section of the water channel (Fig. 2). Without this cage, fish preferred staying in regions of slower flow next to the walls of the water channel, taking advantage of the boundary layer that develops at the walls. The cage greatly reduced the wall effect. The mesh boundaries of the cage, and thus the fish, were at least 10 cm away from the solid boundaries of the tank (bottom, side walls, and top plate), significantly larger than our previously measured boundary layer thickness from 5.5 to 7.0 mm45. As a result, the flow within the cage was much more uniform, as our PIV (Particle Image Velocimetry) calibration verifies (Fig. S1). Flow velocity at the net walls of the chamber was only up to 28% slower than the free stream velocity at the center (Fig. S1). In contrast, without the cage, flow velocity would have decreased to zero at the boundaries, i.e. a 100% reduction in speed. This substantial improvement in flow uniformity mitigated the boundary layer effects on fish school behavior and reduced the frequency with which fish were located near the boundaries.

The experiments were recorded using a pair of streaming cameras AOS PROMON U1000 fitted with aspherical lenses (4-12 mm). Videos were taken from the side and the bottom at 5 fps. Both views were back-lit. We placed an LED panel (HUION A3) at the back of the flow channel for the side view, and two diffused LED spotlights (Nila Zaila) above the water channel for the bottom view. A transparent acrylic plate was placed on the water surface to avoid shadows caused by surface distortion. Videos were streamed to a hard drive (500G) using AOS Imaging Studio. All frames were cropped from 1920x1080 to 1500x600 while being saved. Each 10-hour video took up 2.5 GB in raw format and 32 MB after being converted to mp4 format.

The night before each experiment, we transferred six giant danios into the net cage to allow for at least 12 hours of acclimation. At the beginning of each experiment, we applied gentle flow to clear away debris in the water channel. Two experimental protocols were used in this study. In the steady flow experiments, we provided a constant flow at approximately 14 cm/s or 2.4 BL/s. Throughout the ten-hour experiments, all six fish were able to keep up with the incoming flow and the entire experiment was shrouded to avoid external stimuli affecting fish schooling behavior. Recording started 15 minutes after the flow started. In separate ramping flow experiments, we increased flow velocity by 0.8 BL/s every ten minutes, varying from 1.6 to 5.6 BL/s. We performed six such trials, separated at least an hour apart for fish to rest in static water in between replicate trials.

Fish tracking

We used SLEAP.ai, a deep-learning-based multi-animal markerless tracking algorithm18. We manually labeled the nose and peduncle (the narrowed region before the caudal fin) in approximately 150 frames in both views. Two tracking methods were used: a top-down method used a network to find the location of each fish first and then used a separate network to locate its nose and peduncle (the area near the base of the tail). A bottom-up method used a network to find all the noses and peduncles in a frame before assigning them to each fish. Neither method provided perfect tracking for our videos but one method often succeeded where the other one failed. Therefore, we used both methods and designed a post-processing script in MATLAB to improve tracking results. See Supplemental Information for the pseudo code. In this automated script, we kept the coordinates if they were predicted by both methods. If a coordinate was only identified in one method but not the other, we decided whether to remove it based on a cost function that considered both the fish’s location in the previous frame, and the fish’s streamwise locations (x-coordinate) in the other view. The script then combined the processed information to calculate the 3D trajectories of each fish. Note that as fish cross paths with each other, their identity may be swapped. Therefore, our method cannot yet answer questions such as how often fish switch leadership. The training of all neural nets was performed on Google Colab, and the inference was performed on the Tiger Cluster of Princeton University. On a node with one GPU, four CPUs, and 120 GB memory, tracking all 180,000 frames in a 10-hour video using each method and from each view took around 2.5 to 3 hours. Post-processing took another 5 hours on a node with 1 GPU, 4 CPUs, and 64 GB memory.

Pairwise formations

In this manuscript, fish pairwise formations were defined based on the relative positions between each fish pair within the school. A fish pair is considered to be planar if their relative displacement in the vertical direction is within 0.25 body-length, approximately 1.25 times the height of a fish. Following common practice, we define all staggered formations, inline formations, and side-by-side formations as planar formations. A planar (or at least near-planar) orientation is necessary for fish to interact hydrodynamically based on current hypotheses and models considered further in the Discussion. These formations are distinguished based on the bearing angle, \(\theta\) (Fig. 5C). \(|\theta |< \frac{1}{6}\pi\) (neighbor in the front) and \(|\theta |> \frac{5}{6}\pi\) (neighbor in the back) were defined as inline formations. \(\frac{1}{6}\pi< |\theta |< \frac{1}{3}\pi\) (neighbor at an angle to the front) and \(\frac{2}{3}\pi< |\theta |< \frac{5}{6}\pi\) (neighbor at an angle to the back) were defined as diamond formations. \(\frac{1}{3}\pi< |\theta |< \frac{2}{3}\pi\) were defined as side-by-side formations. The emergent ladder formations were defined based on the brown box in Fig. 5E: for \(-0.625 \text { BL}<\Delta z<-0.125 \text { BL}\) when \(|\theta |< \frac{1}{6}\pi\), and for \(0.125 \text { BL}<\Delta z<0.625 \text { BL}\) when \(|\theta |> \frac{5}{6}\pi\). Based on this definition, if all fish pairs were randomly distributed, staggered, inline, and side-by-side formations would take up 1/3 of planar formations, and all formations including ladder formations would be equally probable at 1/18 or 5.6%.

For the calculation of the probabilities of pairwise formations, we removed the initial transient periods (1 hr) as shown in Fig 3A, B. In addition, we excluded individuals immediately next to our netted cage to avoid the bias introduced by the boundaries. Only fish pairs that are within 4.0 body-lengths apart radially, and 1.5 body-lengths apart vertically were included. Fish pairs outside of this range likely have negligible hydrodynamic and social interactions with each other. The total number of fish pairs that satisfied these criteria was used as the denominator for all probabilities reported in this manuscript.

Fish school metrics

In this project, we calculated fish speed, school height, and school length. Fish speed (Fig. 3A) was calculated as the average speed of all six fish relative to their arena, i.e. the netted cage. School height (Fig. 3B) was calculated as the vertical gap between the highest and the lowest fish detected in the frame. Since the algorithm failed to identify all six fish in some frames, the school height calculated was a lower bound. Any undetected fish would only increase the value, further showcasing that danio schools seldom form planar formations. Lastly, the school length reported in Fig. 6D was calculated as the streamwise distance between the second fish and the second last fish. This was to avoid situations where there was a solitary fish far away, either in front of or behind the school.

To characterize the persistence timescale for fish coordinates x(t), y(t), z(t), and the school volume V(t), we calculated autocorrelation functions (ACF) of these time series (Fig. 3). The school volume V(t) was defined as the convex hull volume around the school. An autocorrelation function calculates how a variable de-correlates with itself given the delay \(\tau\) between the two measurements. It was calculated using the formula ACF\((\tau ) = \frac{\langle (X(t+\tau )-\mu )(X(t)-\mu )\rangle }{\sigma ^2}\). Here, X(t) is a shorthand for any of the four time series to be calculated, and \(\mu\) and \(\sigma\) are the time series’ mean and standard deviation across 2-min-wide moving windows. \(\langle \cdots \rangle\) represents an average across all individuals and all frames. By definition, ACF=1 at \(\tau =0\). As the delay between two measurements of the same variable increases, \(\tau \rightarrow \infty\), \(X(t+\tau )\) and X(t) become un-correlated, and ACF approaches zero. We calculated the de-correlation timescale as the time after which |ACF\(|<0.05\).

Finally, we examined whether the school length, fish’s yaw, and fish pitch correlate with the swimming speed using a general linear model (GLM, Fixed factors: water velocity) followed by Tukey HSD posthoc tests. The test was implemented in SPSS (v29.0.0, SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA).

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.

References

Shaw, E. Schooling fishes: the school, a truly egalitarian form of organization in which all members of the group are alike in influence, offers substantial benefits to its participants. Am. Sci. 66(2), 166–175 (1978).

Zhang, Y. & Lauder, G. V. Energy conservation by collective movement in schooling fish. Elife12, RP90352 (2024).

Weihs, D. Hydromechanics of fish schooling. Nature 241(5387), 290–291 (1973).

Lighthill, S. J. Mathematical biofluiddynamics (SIAM, 1975).

Ko, H., Lauder, G. & Nagpal, R. The role of hydrodynamics in collective motions of fish schools and bioinspired underwater robots. J. Royal Soc. Interface 20(207), 20230357 (2023).

Partridge, B. L. & Pitcher, T. J. Evidence against a hydrodynamic function for fish schools. Nature 279(5712), 418–419 (1979).

Herbert-Read, J. E. et al. Inferring the Rules of Interaction of Shoaling Fish. In Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 108(46), 18726–18731. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1109355108 (2011).

Katz, Y. et al. Inferring the Structure and Dynamics of Interactions in Schooling Fish. In Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 108(46), 18720–18725. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1107583108 (2011).

Butail, S. & Paley, D. A. Three-dimensional reconstruction of the fast-start swimming kinematics of densely schooling fish. J. Royal Soc. Interface9(66), 77–88 (2012).

Ashraf, I. et al. Synchronization and collective swimming patterns in fish (Hemigrammus Bleheri). J. Royal Soc. Interface13(123), 20160734. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsif.2016.0734 (2016).

Ashraf, I. et al. Simple Phalanx Pattern Leads to Energy Saving in Cohesive Fish Schooling. In Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 114(36), 9599–9604. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1706503114 (2017).

Kent, M.A. et al. Speed-mediated properties of schooling. Royal Soc. Open Sci.6(2), 181482. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.181482 (2019).

Mekdara, P. J. et al. Tail beat synchronization during schooling requires a functional posterior lateral line system in giant danios, devario aequipinnatus. Integrative Comparative Biol.61(2), 427–441. https://doi.org/10.1093/icb/icab071 (2021).

Lombana, D. A. B. & Porfiri, M. Collective response of fish to combined manipulations of illumination and flow. Behav. Process.203, 104767. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beproc.2022.104767 (2022).

Zhang, Y. & Lauder, G. V. Energetics of collective movement in vertebrates. J. Exper. Biol.226(20), jeb245617. https://doi.org/10.1242/jeb.245617 (2023).

Zhang, Y. & Lauder, G. V. Physics and physiology of fish collective movement. Newton https://doi.org/10.1016/j.newton.2025.100021 (2025).

Evelyn, S. Schooling in fishes: critique and review. In: LR Aronson et al.(Eds.), Development and Evolution of Behavior. Essays in memory of TC Schneirla, San Francisco (WH Freeman and Company) 1970, pp. 452-480. (1970).

Pereira, T. D. et al. SLEAP: A deep learning system for multi-animal pose tracking. Nat. Methods19(4), 486–495 (2022).

Farrell, A. P. Comparisons of swimming performance in rainbow trout using constant acceleration and critical swimming speed tests. J. Fish Biol. 72(3), 693–710. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1095-8649.2007.01759.x (2008).

Zhang, Y. et al. Collective movement of schooling fish reduces the costs of locomotion in turbulent conditions. PLoS Biol.22(6), e3002501 (2024).

Ko, H., Ting-Ying, Y. & David L. H. Fire ant rafts elongate under fluid flows. Bioinspiration Biomimetics17(4), 045007 (2022).

Wilga, C. D. & Lauder, G. V. Three-dimensional kinematics and wake structure of the pectoral fins during locomotion in leopard sharks Triakis semifasciata. J. Exper. Biol.203(15), 2261–2278 (2000).

Di Santo, V. K., Christopher, P. & Lauder, G. V. High postural costs and anaerobic metabolism during swimming support the hypothesis of a U-shaped metabolism-speed curve in fishes. In Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences114(49), 13048–13053 (2017).

Daghooghi, M. & Borazjani, I. The hydrodynamic advantages of synchronized swimming in a rectangular pattern. Bioinspiration Biomimetics 10(5), 056018 (2015).

Li, L. et al. Vortex phase matching as a strategy for schooling in robots and in fish. Nat. Commun.11(1), 5408 (2020).

Hemelrijk, C. K. et al. The increased efficiency of fish swimming in a school. Fish Fisheries 16(3), 511–521 (2015).

Dai, L. et al. Stable formations of self-propelled fish-like swimmers induced by hydrodynamic interactions. J. Royal Soc. Interface15(147), 20180490 (2018).

Park, S. G. & Sung, H. J. Hydrodynamics of flexible fins propelled in tandem, diagonal, triangular and diamond configurations. J. Fluid Mechan. 840, 154–189 (2018).

Saadat, M. et al. Hydrodynamic advantages of in-line schooling. Bioinspiration Biomimetics16(4), 046002 (2021).

Thandiackal, R. & Lauder, G. In-line swimming dynamics revealed by fish interacting with a robotic mechanism. elife12, e81392 (2023).

Filella, A. et al. Model of collective fish behavior with hydrodynamic interactions. Phys. Rev. Lett.120(19), 198101 (2018).

Heydari, S. & Kanso, E. School cohesion, speed and efficiency are modulated by the swimmers flapping motion. J. Fluid Mechan.922, A27 (2021).

Boschitsch, B. M., Dewey, P. A. & Smits, A. J. Propulsive performance of unsteady tandem hydrofoils in an in-line configuration. Phys. Fluids26(5), 1–2 (2014).

Peter, A. D. et al. Propulsive performance of unsteady tandem hydrofoils in a side-by-side configuration. Phys. Fluids 26(4) (2014).

Li, L. et al. Energy saving of schooling robotic fish in three-dimensional formations. IEEE Robotics Automation Lett.6(2), 1694–1699 (2021).

Yu, P. George, V. L. Combining computational fluid dynamics and experimental data to understand fish schooling behavior. Integrative Comparative Biol. (2024), icae044.

Yu, P. Haibo, D. Computational analysis of hydrodynamic interactions in a high-density fish school. Phys. Fluids 32(12) (2020).

Yu, P. Haibo, D. Effects of phase difference on hydrodynamic interactions and wake patterns in high-density fish schools. Phys. Fluids 34(11) (2022).

Wei, C. et al. Hydrodynamic interactions and wake dynamics of fish schooling in rectangle and diamond formations. Ocean Eng.267, 113258 (2023).

Alec, M. et al. Fish schools in a vertical diamond formation: Effect of vertical spacing on hydrodynamic interactions (Phys. Rev, Fluids, 2025).

Xiaohu, L. et al. Hydrodynamic analysis of fish schools arranged in the vertical plane. Phys. Fluids 33(12) (2021).

Sarfati, R. et al. Spatio-temporal reconstruction of emergent flash synchronization in firefly swarms via stereoscopic 360-degree cameras. J. Royal Soc. Interface17(170), 20200179 (2020).

Sarfati, R., Hayes, J. C. & Peleg, O. Self-organization in natural swarms of Photinus carolinus synchronous fireflies. Sci. Adv.7(28), eabg9259 (2021).

Mohebbi, N. et al. Measurements and modelling of induced flow in collective vertical migration. J. Fluid Mechan.1001, A50. https://doi.org/10.1017/jfm.2024.1102 (2024).

Tytell, E. D. & Lauder, G. V. The hydrodynamics of eel swimming. J. Exper. Biol.207(11), 1825–1841. https://doi.org/10.1242/jeb.00968 (2004).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the support from ONR MURI grant N00014-22-1-2616 (co-PIs R. Nagpal and G.V. Lauder). In addition, H.Ko is supported by the James S. McDonnell Foundation’s Postdoctoral Fellowship for Understanding Dynamic & Multi-scale Systems and the Company of Biologists Travelling Fellowship. Y. Zhang is supported by a Postdoctoral Fellowship of the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC PDF - 557785 – 2021) and a Banting Postdoctoral Fellowship (202309BPF-510048-BNE-295921) of NSERC & CIHR (Canadian Institutes of Health Research). Computations performed on a cluster managed and supported by Princeton Research Computing.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

This statement is inspired by a recent initiative (Zurn et al. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2020.06.009) and recent studies that revealed the under-representation and under-citation of women, non-white, and other marginalized scholars (Teich et al. https://doi.org/10.1038/514s41567-022-01770-1). Here, we provide a breakdown of our references using the tool https://github.com/dalejn/cleanBib, excluding self citations. Our references contain 8.8% woman(first author)/woman(last author), 20.6% man/woman, 17.7% woman/man, and 52.9% man/man. By race, our references contain 18.2% non-white(first)/non-white(last), 11.3% white/non-white, 19.2% non-white/white, and 51.2% white/white. This method is limited in that the gender and race predictions are not always correct, and fail to account for non-binary, transgender, indigenous, and mixed-race, and other marginalizations. We look forward to future work that better supports equitable practices in science.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ko, H., Girma, A., Zhang, Y. et al. Beyond planar: fish schools adopt ladder formations in 3D. Sci Rep 15, 20249 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-06150-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-06150-2