Abstract

Tyrosinase is a crucial enzyme targeted for the development of various skin-whitening agents due to its role in regulating key steps in melanin production. Despite the significance of human tyrosinase (hTYR), its crystal structure remains unresolved, hindering the development of specific inhibitors. Researchers frequently use mushroom tyrosinase (mTYR) to evaluate the inhibition capabilities of compounds, but the structural differences between hTYR and mTYR present considerable challenges in accurately developing hTYR-specific inhibitors. For instance, compounds like kojic acid show promising inhibitory effects but face limitations due to cytotoxicity or allergic reactions. This study aims to utilize the AlphaFold-predicted structure of hTYR to provide insights for developing specific inhibitors by comparing it with mTYR. We utilized natural tyrosinase inhibitors reported in the literature for molecular docking and molecular dynamic simulations to examine their binding modes with mTYR and hTYR. Through the analysis of these binding interactions and dynamic behaviors, we intend to identify residues that significantly enhance affinity, assess reliable binding modes, and offer essential insights for the development of effective hTYR inhibitors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Tyrosinase catalyzes the hydroxylation of L-tyrosine, initiating a series of biochemical reactions that lead to the production of melanin (Fig. 1a)1. Melanins are primarily dark pigments ranging from black to brown, although some forms can appear light red or yellow2. Based on their pigment compositions, melanins are classified into two main types: Eumelanin (eu = good) and Pheomelanin (pheo = cloudy or dusky), which differ in their pigment ratios and contribute to the variations in hair and skin color3,4. Melanin plays a crucial role in the browning of fruits, fungi, and vegetables, as well as in the pigmentation of mammalian skin. It serves as a broad-spectrum UV absorber and exhibits antioxidant properties along with free radical scavenging abilities5. However, excessive or abnormal melanin production can result in various hyperpigmentation disorders, such as freckles, melasma, and age spots6. The catalytic process of tyrosinase in melanin biosynthesis can be broadly divided into two stages. In the first stage, tyrosinase catalyzes the hydroxylation of L-tyrosine to form L-3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine (L-DOPA) (monophenolase activity), which is then oxidized to dopaquinone (diphenolase activity). In the second stage, dopaquinone undergoes two distinct pathways to synthesize Eumelanin and Pheomelanin. Since most reactions in the second stage are spontaneous, tyrosinase acts as the rate-limiting enzyme in melanin synthesis, making it the primary enzyme involved in both enzymatic browning and melanin production7.

Tyrosinase, a multifunctional copper-containing oxidase, is crucial for melanin synthesis in humans and other organisms. The full-length human tyrosinase comprises 529 amino acid residues and has a molecular weight of approximately 59.1 kDa. While the three-dimensional structure of tyrosinase has been crystallized in various species, the human tyrosinase crystal structure remains unresolved. In recent years, several studies have utilized the structure of mushroom tyrosinase as a model enzyme due to the unavailability of the human structure8,9,10,11,12. However, the low sequence homology of 25% between mushroom tyrosinase (C7FF04) and human tyrosinase (P14679) indicates significant structural differences, limiting the applicability of mushroom-based findings to human tyrosinase. Recent advances in computational biology, particularly through the development of AlphaFold, have enabled the prediction of the structures of 98% of the human proteome13,14. This significant breakthrough allows researchers to use the predicted structure of human tyrosinase for more accurate and refined biochemical studies.

The catalytic active site of tyrosinase contains multiple histidine residues that coordinate with copper ions, forming an active center capable of catalyzing the oxidation of tyrosine. (Fig. 1b). Structural changes in this active center are closely linked to the enzyme’s catalytic activity, which determines its ability to oxidize tyrosine15. Tyrosinase undergoes catalytic reactions through three oxidative states: oxidized tyrosinase (oxy), met tyrosinase (met), and deoxy tyrosinase (deoxy)1,16. In the oxy state, the copper ion at the active site chelates with a peroxide molecule (Fig. 1b), directly catalyzing the conversion of L-Tyrosine to Dopaquinone-H + while converting itself to deoxy form, or catalyzing L-Tyrosine substrates into L-Dopa while converting itself to met state. In the met state, the copper ion at the active site chelates with a hydroxide ion (Fig. 1b), maintaining its oxidation capability to oxidize L-Dopa substrates to Dopaquinone-H + while converting itself to deoxy state. In the deoxy state (Fig. 1b), the enzyme has no catalytic function. When an oxygen molecule enters the active site, deoxy tyrosinase converts back to the oxidized tyrosinase state, completing the cycle. These transformations among the three states are critical steps in the oxidative reactions catalyzed by tyrosinase (Fig. 1c).

Tyrosinase is widely present in fungi, plants, and animals, and plays a crucial role in various biological processes, making it highly valuable in the biomedical and cosmetic fields. In medicine, tyrosinase is a key therapeutic target for treating a range of skin pigmentation disorders, including vitiligo17, hyperpigmentary18,19,20,21, and melanoma22. In the food processing industry, tyrosinase is used to prevent oxidative discoloration in fruits and vegetables, thereby enhancing product quality and extending shelf life23. Furthermore, tyrosinase is extensively utilized in the cosmetics industry for the development of products aimed at addressing consumer skin concerns, including anti-aging, skin lightening, and skincare24.

Tyrosinase inhibitors are crucial in skincare products aimed at reducing pigmentation, with compounds like hydroquinone and kojic acid had been commonly used7. However, several chemicals exhibit significant toxicity, including cytotoxicity and mutagenicity25. For instance, hydroquinone’s potential has been hindered by adverse reactions such as burning, stinging, and ochronosis, leading to its ban in skincare products7. Similarly, kojic acid can cause side effects such as erythema, stinging, moderate exfoliation, and contact dermatitis25,26. Additionally, kojic acid is carcinogenic to the thyroid and liver in rodent models, resulting in its prohibition in Switzerland27. In contrast, the market favors tyrosinase inhibitors with lower toxicity, including natural products like arbutin, peptides, and Chinese medicinal extracts. Arbutin, particularly β-arbutin, is widely used in cosmetic products for its significant skin-lightening effects22 and relatively low cytotoxicity28. Understanding the binding mechanisms of arbutin with human tyrosinase is valuable for developing effective inhibitors. Meanwhile, peptides have gained attention in recent years due to their non-toxic and effective properties, attracting significant interest from researchers25,29,30. Glutathione plays a crucial role in protecting cells from oxidative damage by interacting with vitamin C31 and vitamin E32, participating in cellular metabolism33, and reducing cytotoxic effects34. Its mechanisms for inhibiting melanin production include binding to the copper-containing active site of tyrosinase to inhibit activity and quenching free radicals and peroxides35. In addition to arbutin and glutathione, which have been widely used, The use of Chinese medicinal extracts integrates traditional Chinese medicine principles with modern cosmetic techniques to treat skin pigmentation using natural extracts from both animals and plants36,37. Sea cucumber was noted in many ancient texts, such as Bencao Gangmu Shiyi, Wuzazu, Bencao Congxin, as a tonic and medicinal ingredient, contains nutrients such as vitamin A, vitamin B1 (thiamine), vitamin B2 (riboflavin), vitamin B3 (niacin), and minerals38,39. Studies have shown that various sea cucumber extracts can influence melanin production25,40,41,42,43. Currently, the sea cucumber peptide CME has only been studied in the laboratory. However, with the market’s enthusiasm for low-toxicity polypeptide extracts derived from traditional Chinese medicine, polypeptide tyrosinase inhibitors may be the main direction in the future.

Molecular dynamics is widely used in the analysis of conformational changes in the pockets of target proteins44, as well as in the design and research of inhibitors based on the structure of the target45,46. In recent years, numerous computational studies have investigated tyrosinase inhibitors using the structure of mushroom tyrosinase (mTYR) as a model enzyme8,9,10,11,12. Computational chemistry tools, such as molecular docking and molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, have proven invaluable for analyzing the binding modes and mechanisms of these inhibitors. Molecular docking predicts the initial binding sites and conformations of inhibitors at the enzyme’s active site. MD simulations further elucidate the dynamic behavior of enzyme-inhibitor complexes under physiological conditions, revealing the roles and interactions of key amino acid residues during the binding process47. These computational methods provide crucial molecular-level details that enhance our understanding of inhibitor mechanisms and guide the design and optimization of novel inhibitors48.

While some studies have shown a correlation between computational results on mTYR and experimental results on human tyrosinase (hTYR)8, the lack of a resolved hTYR crystal structure has hindered a deeper understanding of the inhibitory mechanisms of many compounds against hTYR. This limitation underscores the need for targeted computational studies on hTYR. In this study, we leverage the recent availability of the AlphaFold3-predicted hTYR structure to investigate the binding modes and inhibitory mechanisms of three natural compounds: arbutin, glutathione, and sea cucumber peptides. These compounds were selected based on their reported tyrosinase inhibitory activities and their potential as safe and effective skin-whitening agents. By employing molecular docking and MD simulations, we aim to:

(1) Characterize the binding modes of arbutin, glutathione, and sea cucumber peptides to hTYR. This includes identifying the key residues involved in binding and analyzing the specific interactions contributing to inhibitor binding.

(2) Compare the binding modes and inhibitory mechanisms of the three compounds. This will provide insights into the development of more potent and selective inhibitors.

(3) Analyze the binding modes of inhibitors, examine the interactions that facilitate inhibitor binding, and identify key binding residues or regions of the inhibitors.

By exploring the mechanisms of tyrosinase inhibitors based on natural whitening ingredients, this study aims to utilize computational simulations to aid in developing safe and effective compounds with whitening efficacy for skincare applications.

Materials and methods

Docking and system Preparation

The X-ray crystal structure and sequence of tyrosinase bound with tropolone and copper (PDBID: 2Y9X) were obtained from the RCSB Protein Data Bank (https://www.rcsb.org/)49. A single crystal unit of tyrosinase comprises four subunits, four tropolone molecules, four Ho atoms, and eight Cu atoms, with a resolution of 2.78 Å. The human tyrosinase structure, predicted using AlphaFold3, estimated a high confidence value (pLDDT mostly above 90). The structure selected for dynamic simulation in solvent was renumbered starting from 1, between residues Phe20 and Asp454. Molecular dynamics simulations of 200 ns were performed for both mushroom and human tyrosinase structures with subsequent cluster analysis to identify the representative structures for docking studies49.

MOE (Molecular Operating Environment) software was used to perform induced-fit docking simulations on the enzyme-inhibitor complexes50. Induced fit docking was applied to optimize the binding conformations of inhibitors with tyrosinase. Parameters near the copper ions were constructed using MCPB.py51. This process generated PDB files for small, standard, and large models, as well as fingerprint files for standard and large models, and quantum input files for small and large models52. Gaussian 16 was used, employing the XQC convergence criteria, to calculate partial charges for the Cu ions and their surrounding histidine coordinating atoms at the B3LYP/6-31G* level54. Subsequently, MCPB.py was utilized to generate the topology and coordinate files required for simulations.

Molecular dynamics simulations and analysis

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations were performed using the AMBER2247. The protein-ligand complexes were solvated in a TIP3P water box53 with periodic boundary conditions. The systems were initially neutralized with Na+ counterions via the tleap module in AMBER22 to balance electrostatic charges. Subsequently, Na+/Cl+ ion pairs were systematically added to attain a physiological NaCl concentration, emulating intracellular ionic strength conditions54. A cutoff distance of 10 Å was applied to manage nonbonding interactions, ensuring efficient computation and accurate simulation of molecular interactions47. The AMBER19SB force field55 was applied to the tyrosinase complexes56,57,58. All protein-ligand complexes underwent one 500-ns MD simulation and two independent 200-ns MD simulations, with all trajectories subjected to RMSD analysis. The final 200-ns segment of the 500-ns MD simulation was used for RMSF analysis and binding free energy calculations. While the 200-ns replicates served as control runs to verify result reliability, the final 80-ns segment of the repetitive MD simulations were used for binding free energy calculations. In the hydrogen bond analysis, the Acceptor column represents the hydrogen bond acceptor, the DonorH column represents the hydrogen bond donor, and the Frac column indicates the percentage of hydrogen bond conformations relative to all conformations across the trajectories.

MM/PBSA (Molecular Mechanics/Poisson-Boltzmann Surface Area) calculates the free energy difference between the ligand and the protein-ligand complex in various states, which helps evaluate the binding affinity of a ligand to a protein. In this study, MM/PBSA is used to calculate the binding free energy between tyrosinase (hTYR and mTYR) and inhibitors, in order to assess the strength of their interactions and screen potential binding modes with high affinity59. The last 200 ns of the trajectory were used to obtain the free binding energy.

Results

Structural comparison of mTYR and hTYR

The three-dimension al structure of tyrosinase has been crystallized in various species, but the human-derived crystal structure is still unavailable. Mushroom tyrosinase consists of 576 amino acids, divided into L and H subunits. The L subunit, being relatively distant from the active site (25 Å), does not obstruct ligand entry and is considered not to affect the binding of ligands to the dicopper center60. Thus, the H subunit sequence of mTYR was selected for comparison with human tyrosinase. The human tyrosinase sequence comprises 529 amino acids. The AlphaFold-predicted structure with high confidence corresponds to residues 20 to 45213, which was chosen for structural analysis and computational study (Fig. 2a). The sequence identity between mTYR and hTYR is only 25%, implying limited structural similarity and transferability of research results from mTYR to hTYR.

Static comparison of mTYR and hTYR: (a) Sequence comparison of hTYR and mTYR: (b, c) Residues surrounding the pocket in mTYR; (d, e) Residues surrounding the pocket in hTYR; (f) The overall structure of the mTYR and the key residues around its pockets (C1: H243, E255, N259 and F263); (g) The overall structure of the hTYR and the loop area around its pockets (L1: Residues 40–50; L2: Residues 176–182; L3: Residues 284–292; L4: Residues 356–351).

For hTYR, H161, H183, and H192 chelate CuA, while H344, H348, and H371 chelate CuB. For mTYR, H60, H84 and H93 chelate CuA, while H258, H262 and H295 chelate CuB. The pocket surface of mTYR is more deeply embedded within the protein, positioning the dual copper-binding site at the pocket surface. This structure may facilitate smaller inhibitors entering the pocket and chelating with copper ions, while larger molecules are more likely to bind with residues on the outer edge of the pocket, occupying the pocket entrance (Fig. 2b, c). In contrast, the dual copper-binding site of hTYR is positioned deeper inside the protein(Fig. 2d). According to the static PDB structure, it is difficult for inhibitors to interact with copper ions and inhibit tyrosinase activity (Fig. 2e). This also highlights the importance of studying the binding modes of tyrosinase inhibitors using molecular dynamics in the development of human tyrosinase inhibitors.

According to the main chain lengths of the two tripeptides, the residues on the surface of the pocket within a range of 12 Å from the copper ion were selected for analysis (Table 1). Within this 12 Å range, there are 18 residues respectively distributed on the surfaces of the hTYR and mTYR pockets. Compared to mTYR, the hTYR pocket contains more acidic amino acids, including Asp167, Asp178, Asp180, Asp286, and Glu184 (Table 1). Conversely, the mTYR pocket has more hydrophobic amino acids. The identity of the residues surrounding the pockets of mTYR and hTYR is only 11.8%, with a similarity of 23.5%. These differences indicate that computational research based on non-human tyrosinase cannot be directly applied to human tyrosinase, and inhibitor design must consider the specific characteristics of the human tyrosinase pocket.

Computational simulation study of arbutin

Docking analysis

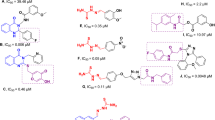

Arbutin is a widely used whitening agent that inhibits tyrosinase activity. Based on the spatial orientation of the glycosidic bond, it exists in two forms: α-Arbutin and β-Arbutin. In this study, the more commonly used β-Arbutin was selected for docking analysis (Fig. S1, Table S1).

Several studies have investigated the binding modes of arbutin with tyrosinase from various sources. Mubashir Hassan et al.61 found that in Bacillus megaterium tyrosinase (PDB: 3NTM), the hydroxyphenyl part of arbutin orients towards the copper-binding site and interacts with the pocket. Antonio Garcia-Jimenez et al.62 found that in Agaricus bisporus tyrosinase (PDB: 2Y9W), the hydroxyphenyl part of arbutin binds closer to the CuB ion. Daungkamon Nokinsee et al.63 suggested that arbutin primarily relies on the hydroxyphenyl part to form π-π stacking with histidines around the metal site, stabilizing its binding. Conversely, Tang et al.64 reported that in Bacillus megaterium tyrosinase (PDB: 3NM8), the pyranose glucoside part of arbutin faces the metal active site. Additionally, an arbutin derivative (AU)64 binds to the metal active site of mushroom tyrosinase (PDB: 2Y9X) via its ether group. These findings suggest that the source of tyrosinase can influence the optimal binding mode of arbutin, indicating that arbutin may have two preferred binding orientations.

Based on this research, docking was performed on the dual copper-binding sites of mTYR and hTYR. Referring to the docking modes from earlier studies, the highest-scoring binding modes in these conformations were selected (Fig. 3).

Docking conformations of arbutin, which is shown in yellow, with surrounding residues in blue(mTYR)/pink(hTYR): (a) Arbutin_a: Arbutin binds within the pocket and chelates with Cu ions in mTYR; (b) Arbutin_b: Arbutin binds to the surrounding residues of the pocket in mTYR; (c) Arbutin_c: Arbutin binds within the pocket and chelates with Cu ions in hTYR; (d) Arbutin_d: Arbutin binds within the pocket and chelates with Cu ions in hTYR.

In the two binding modes of mTYR, arbutin coordinates with CuA in both cases. In Arbutin_a, arbutin additionally forms hydrogen bonds with H84, H263, and V282, which collectively stabilize arbutin in the pocket’s upper side (Fig. 3a). In Arbutin_b, the pyranose glucose part of arbutin is positioned deeper within the pocket, coordinating with CuA and forming hydrogen bonds with H84 (Fig. 3b). This could be due to the narrower pocket at the dual copper-binding site of mTYR (Fig. 2b), which restricts the conformational flexibility of arbutin in this binding mode, thereby limiting opportunities for additional interactions.

In hTYR, docking simulations revealed two potential binding modes of arbutin at the active site of hTYR. In the first mode (Fig. 3c), the hydroxyphenyl portion interacts with CuA at a distance of 3.3 Å, while the hydroxyl group of the pyranose glucoside forms hydrogen bonds with H161, S165, D180, and E184. In the second mode (Fig. 3d), the pyranose glucoside is closer to the dicopper center, with its ether group interacting with CuB at a distance of 2.5 Å, and two hydroxyl groups forming hydrogen bonds with S361 and E326, which stabilizes the ligand binding. In both binding modes, arbutin interacts with residues on the CuA and CuB sides, respectively.

MD analysis

The mean binding free energies from all MD simulations are −30.2195 ± 1.6479 kcal/mol for Arbutin_a, −12.4682 ± 1.8569 kcal/mol for Arbutin_b, −30.8403 ± 1.4281 kcal/mol for Arbutin_c, and −28.0049 ± 0.8462 kcal/mol for Arbutin_d. The arbutin-tyrosinase complexes demonstrated remarkable conformational consistency throughout MD simulations, with RMSD analysis and binding free energy (Fig. S4 and Table S2).

In mTYR, the MD-stable conformation of Arbutin_a exhibits minimal deviation from its initial docking pose (Fig. 4a). In contrast, during molecular dynamics simulations, the spatial orientation of Arbutin in the Arbutin_b conformation shows noticeable changes compared to its docked structure, which may be attributed to the limited space within the binuclear copper active site that constrains the positioning of the pyranosyl glucose moiety (Fig. 4b). In hTYR, the hydroxylphenyl group of Arbutin_c, which originally coordinated with CuA, shifts and instead coordinates with CuB during the simulation (Fig. 4e). Meanwhile, Arbutin_d maintains coordination with CuB throughout the simulation, with only minor deviations from its original docking conformation (Fig. 4f).

To investigate the binding stability of the two modes, the root mean square deviation (RMSD) of the protein backbone atoms for each mode was measured (Fig. 4, Fig. S4). The RMSD of Arbutin_a and Arbutin_b is generally greater than 1.4 Å after 200 ns, with the former’s RMSD continuously increasing after 400 ns, reaching over 2.2 Å. The RMSD for Arbutin_c increased at the beginning of the simulation but eventually stabilized above 1.4 Å, while Arbutin_d maintained better stability, remaining below 1.4 Å throughout the simulation. Considering both the RMSD values and free energy, Arbutin_d demonstrates better stability. For mTYR, the narrow dual copper-binding site makes it more difficult for arbutin, which has two rings, to fit, especially in the MD-stable conformation of Arbutin_b, where the number of hydrogen bonds between arbutin and the pocket is much lower than in other conformations (Table 2). In contrast, the pocket of hTYR allows the binding mode of arbutin to be more flexible and stable.

To analyze the flexibility of the protein residues, the root mean square fluctuation (RMSF) was measured and plotted (Fig. 4d, h). Higher RMSF values indicate greater flexibility, while lower values indicate greater rigidity. In mTYR, both Arbutin_a and Arbutin_b have the maximum RMSF at V247, a residue located in the lower part of C1 (Fig. 2f). Part of the reason could be that arbutin does not form hydrogen bonds with the residues in the C1 region (Table 2).The RMSF values of the residues surrounding Arbutin_c and Arbutin_d were generally low. The lower RMSF values for residues 200 to 400 in the Arbutin_d mode are hypothesized to be due to the hydroxyphenyl group of Arbutin_d facing the L3 region, where R289 tends to interact with the hydroxyphenyl group of Arbutin, stabilizing this region.

MD conformations and trajectory analysis for abutin: (a) MD-Stable conformations of Arbutin_a; (b) MD-Stable conformations of Arbutin_b; (c) RMSD of mTYR backbone atoms; (d) RMSF of mTYR residues (300ns ~ 500ns), with red and blue scatter points marking the parameters of residues within 4 Å of the ligand in their binding modes; (e) MD-Stable conformations of Arbutin_c; (f) MD-Stable conformations of Arbutin_d; (g) RMSD of hTYR backbone atoms; (h) RMSF of hTYR residues (300ns ~ 500ns), with red and blue scatter points marking the parameters of residues within 4 Å of the ligand in their binding modes.

During the 300 ns to 500 ns MD simulation, hydrogen bonds between the protein and the ligand were analyzed (Table 2). The comparison of docking and MD stable conformations helps to determine the stability of the complexes. Due to the high polarity of β-Arbutin, it readily forms hydrogen bonds to stabilize binding conformation. The docking conformation of Arbutin_a shows very little difference from the MD-stable conformation, indicating that arbutin can stably bind to mTYR in this conformation. On the other hand, Arbutin_b shows greater conformational changes, and its binding hydrogen bonds are also fewer (Table 2). For Arbutin_c, it stably interacts with four key residues: D180, E184, S165, and S361 (Table 2). Compared to the conformation in Fig. 3c, the hydroxyphenyl group’s chelation site shifted from CuA to CuB, and it interacts more with regions L2 and L4, orienting from the L2 region towards CuB. For Arbutin_d, the key interacting residues are S356, E326, and E184 (Table 2). In comparison to the docking conformation, the chelation site of CuB shifted from the ether oxygen to the hydroxymethyl group, with the hydroxyphenyl group forming a hydrogen bond with S356. The overall orientation shifted from CuA towards the L4 region. This orientation potentially stabilizes the L3 region.

Given its small molecular weight, β-Arbutin, with its hydroxyphenyl head, can easily fit into the binding pocket of both hTYR and mTYR. The stable binding of the pyran glucoside part of Arbutin_d around the metal site also suggests that β-Arbutin may have multiple binding tendencies with hTYR.

Computational simulation study of glutathione (GSH)

Docking analysis

Glutathione is a small peptide composed of three amino acids (glutamate, cysteine, and glycine) and performs several important biological functions (Fig. S2). The glutamate and cysteine residues are connected by a γ-amide bond, forming the structure of γ-glutamylcysteine.

Although glutathione’s inhibition of melanin production is not solely due to tyrosinase inhibition, studying endogenous peptide inhibitors such as glutathione can significantly contribute to the research of other peptide inhibitors. GSH was subjected to multiple docking runs against both human and mushroom tyrosinases, from which several representative conformations were selected for further analysis (Fig. 5, Table S1).

Docking conformations of glutathione, which is shown in purple, with surrounding residues in blue(mTYR)/pink(hTYR): (a) GSH_a: GSH binds within the pocket and chelates with Cu ions in mTYR; (b) GSH_b: GSH binds to the surrounding residues of the pocket in mTYR; (c) GSH_c: GSH binds within the pocket and chelates with Cu ions in hTYR; (d) GSH_d: GSH binds to the surrounding residues of the pocket in hTYR.

The docking results of GSH with mTYR indicate that GSH can form extensive interactions with the residues surrounding the pocket. However, due to the narrow spatial structure of the mTYR pocket, the positioning of GSH within the pocket is restricted, leading to relatively uniform docking results. Based on the docking scores provided by MOE, two binding modes, GSH_a and GSH_b, are considered more likely. In the first binding mode (Fig. 5a), GSH not only maintains stable coordination with the copper ion but also establishes a network of hydrogen bonds with amino acids such as H84, H60, and N259. Notably, the glutamic acid portion of GSH forms a salt bridge with N259, exhibiting a binding energy of −10.9 kcal/mol, which undoubtedly stabilizes this binding mode. In the second binding mode (Fig. 5b), the overall position of GSH shifts upwards relative to GSH_a, forming a hydrogen bond with V282 and moving closer to the C1 region. The glutamic acid portion of GSH once again forms a salt bridge with N259, showing a binding energy of −11.4 kcal/mol.

Docking results of glutathione at the hTYR binding pocket reveal two potential binding modes. In the first binding conformation (Fig. 5c), the glutamate part interacts with S165 and D180, with a binding energy of −22.3 kcal/mol, while the cysteine part forms a hydrogen bond with E326. The thiol group further stabilizes the complex through additional hydrogen bonds within the pocket. The carboxyl group of the glycine part chelates with the two copper ions, with the hydroxyl oxygen binding to CuB at a distance of 2.82 Å and the carbonyl oxygen binding to CuA at a distance of 2.66 Å. These hydrogen bonds enable glutathione to extend into the metal center, stabilizing its binding within the pocket. In the second binding conformation (Fig. 5d), the charged amino group of glutamate interacts with D167 and R177, with binding energies of −17.3 and − 16.3 kcal/mol, respectively. Additionally, it forms a hydrogen bond with I179. Q357 forms a hydrogen bond with the cysteine part, enhancing the stability of the middle part of the ligand. The glycine part forms three hydrogen bonds with R289 and N345, with an average binding energy of −5.6 kcal/mol. In this binding mode, GSH primarily interacts with L2, L3, and L4, blocking the entrance of the pocket.MD Analysis.

The mean binding free energies from all MD simulations are −23.6431 ± 1.1179 kcal/mol for GSH_a, −19.1851 ± 2.2096 kcal/mol for GSH_b, −22.0390 ± 0.9459 kcal/mol for GSH_c, and −16.7373 ± 1.3320 kcal/mol for GSH_d. The selected GSH-tyrosinase complexes demonstrated remarkable conformational consistency throughout MD simulations, with RMSD analysis and binding free energy (Fig. S5 and Table S2).

Compared to the docking conformation, the MD-stable conformation of GSH_a shows little change, suggesting that this binding mode may be reliable. The stable salt bridge interaction between GSH and N259, along with the chelation with the copper ion, allows the entire structure to fit well into the mTYR pocket (Fig. 6a). In the simulation, the binding mode of GSH_b does not has a good stability. In some conformations, the glutamic acid moiety of glutathione in GSH_b still tends to form a hydrogen bond with V282, just like in the docking conformation. In other conformations, it chelates with the copper ion (Fig. 6b). It is notable that GSH_b_r1 shows the similar conformation in Fig. S6, and the RMSD of GSH_b_r2 also showed an upward trend. The cysteine part of GSH_c shifts towards the L4 region compared to the docking conformation Compared to the docking conformation (Fig. 6e). In GSH_d, the entire conformation is pulled towards the L2 region, with the glycine part losing its hydrogen bond with R289 and forming an interaction with K315 (Fig. 6f).

The RMSD of GSH_a and GSH_b illustrates the fluctuation of the protein backbone following GSH’s binding to mTYR (Fig. 6c, Fig. S5). GSH_a’s RMSD shows slight fluctuations during the first 50 ns but stabilizes around 1.5 thereafter, while the RMSD of GSH_b gradually increases over time. Given the difference between its MD and docking conformations, it suggests that the dynamic trajectory of GSH_b is less stable. RMSD analysis (Fig. 6g) reveals that the backbone atoms of GSH_c experience some deviation at around 50 ns and 180 ns, stabilizing after 200 ns and maintaining this stability until 500 ns. This suggests the reliability of GSH_c’s MD stable conformation. Following stabilization at 200 ns, GSH_d maintains an RMSD similar to that of GSH_c.

The RMSF curves of GSH_a and GSH_b are quite similar, both showing larger fluctuations around residue 249, which corresponds to a small loop below the C1 region (Fig. 2f). GSH_a’s RMSF value around residue 249 is slightly smaller, indicating that in the GSH_a mode, glutathione is more likely to stabilize the mTYR structure (Fig. 6d). Compared to GSH_a, the higher RMSF values of residues surrounding GSH_b reflect its greater conformational flexibility. In the GSH_c binding mode, residue 49 in the L1 region is within 4 Å of the ligand (Fig. 6h). In this binding mode, no hydrogen bonds are formed between this residue and the ligand (Table 3), but the RMSF is relatively high. This is likely because the hydrogen bond between GSH and D180 in the L2 region is unstable (Table 3), causing fluctuations that affect the L1 region, resulting in significant movement in residues 40 to 49. For GSH_d, the RMSF shows significant fluctuations in residues 285 to 290 in the L3 region (Fig. 6h). Analysis of the docking conformation (Fig. 5d) and hydrogen bonds (Table 3) reveals that R289, which initially formed hydrogen bonds with GSH, shifts during the simulation, altering the original binding mode.

MD conformations and trajectory analysis for glutathione: (a) MD-Stable Conformations of GSH_a; (b) In GSH_b, the glycine moiety of glutathione participates in copper ion chelation; (c) RMSD of mTYR backbone atoms; (d) RMSF of mTYR residues (300ns ~ 500ns), with red and blue scatter points marking the parameters of residues within 4 Å of the ligand in their binding modes; (e) MD-Stable Conformations of GSH_c; (f) MD-Stable Conformations of GSH_d; (g) RMSD of hTYR backbone atoms; (h) RMSF of hTYR residues (300ns ~ 500ns), with red and blue scatter points marking the parameters of residues within 4 Å of the ligand in their binding modes.

During the molecular dynamics simulations, GSH_b exhibits a tendency to chelate copper ions, showing some similarity to GSH_a in this regard. The key residues in both GSH_a and GSH_b binding modes are located in the C1 region (N259 and E255), it is evident that for GSH, the C1 region of mTYR is the critical binding area. The key binding residues for GSH_a are E184, D180, S361, and Q359 (Table 3). In the MD stable conformation of hTYR, GSH_c forms hydrogen bonds with residues in the L2 and L4 regions, spanning these regions and ultimately chelating with both copper ions. For GSH_d, the key binding residues are D167, R177, I179, S165, Q357, and K315 (Table 3). The charged amino group of the glutamic acid moiety forms stable interactions with D167, R177, and I179. Although the glycine part forms a salt bridge with K315, the long and flexible side chain of K315, which can span up to 12 Å, suggests that this binding mode is not stable.

The high flexibility and length of the γ-glutamyl bond formed by glutamic acid and cysteine in GSH contribute to the instability of its interactions with the loop regions. However, this flexibility also allows GSH to penetrate deeper into the binding pocket and reach the dicopper active site. For the more extended peptide backbone of GSH, the binding modes GSH_a and GSH_c appear to be more valuable in computational studies due to their greater stability.

Computational simulation study of sea cucumber peptide (CME)

Docking analysis

Sea cucumber extracts contain a variety of compounds that can be used as skin-whitening agents. Among these, the protein hydrolysates from echinoderms like sea cucumbers are rich in antioxidant peptides65. Specifically, extracts from the viscera of sea cucumbers (Stichopus japonicus viscera extracts, VF) have been shown to stimulate the ERK signaling pathway, downregulate melanin synthesis, and enhance collagen synthesis42. Additionally, compounds such as ethyl-α-D-glucopyranoside and adenosine have been isolated from sea cucumbers and identified as potential tyrosinase inhibitors43. For this study, we selected the tripeptide extract CME from sea cucumbers for computational analysis25.

Hui Chen et al.25, suggested that CME (Fig. S3) interacts with histidines and glutamates around the metal site in mushroom tyrosinase (mTYR), forming stable complexes. Multiple docking simulations of CME with both human and mushroom tyrosinases were performed, with representative conformations being selected for subsequent analysis (Fig. 7, Table S1).

Docking conformations of CME, which is shown in green, with surrounding residues in blue(mTYR)/pink(hTYR): (a) GSH_a: GSH binds within the pocket and chelates with Cu ions in mTYR; (b) GSH_b: GSH binds to the surrounding residues of the pocket in mTYR; (c) GSH_c: GSH binds within the pocket and chelates with Cu ions in hTYR; (d) GSH_d: GSH binds to the surrounding residues of the pocket in hTYR.

The narrow pocket of mTYR and the long side chain of CME limit the available conformations for CME during the docking process. Two binding modes, CME_a and CME_b, are selected (Fig. 7a, b). In CME_a, the glutamate portion of the CME forms stable chelation with the double copper binding site, and CME forms hydrogen bonds with H84, H262, and N259 in the pocket, which greatly contributes to the overall stability. In CME_b, CME interacts with residues around the pocket, and the interaction with the C1 region helps it better occupy the pocket position in MD simulation.

Two potential binding modes were selected from the docking results in hTYR (Fig. 7c, d). In the first binding conformation (Fig. 7c), the charged amino group of the cysteine part of CME interacts strongly with the side-chain carboxyl group of E184, exhibiting a binding energy of −11.3 kcal/mol. The methionine part forms hydrogen bonds with N345 and E184, which stabilize the ligand binding conformation. The side-chain hydroxyl oxygen of the glutamate part chelates with CuA at a distance of 2.66 Å, while the carbonyl oxygen forms a hydrogen bond with S361. This binding mode is similar to GSH_c, primarily involving chelation with copper ions and interaction with E184 to determine the binding mode. In the second binding conformation (Fig. 7d), the cysteine part of CME forms hydrogen bonds with D180, E184, and Q359. The charged amino group of cysteine forms stable hydrogen bonds with the carboxyl groups of D180 and E184, exhibiting binding energies of−9.6 and − 9.2 kcal/mol, respectively. Both peptide bonds of the tripeptide form hydrogen bonds with the carboxyl group of E184, stabilizing the overall binding of the tripeptide CME around E184 within the pocket. The C-terminus residue and its side chains interact with R289 and N345, respectively. CME_d forms additional hydrogen bonds with E184, further stabilizing the overall position of the tripeptide within the pocket.

MD analysis

The mean binding free energies from all MD simulations are −12.7041 ± 0.3243 kcal/mol for CME_a, −11.1474 ± 0.8642 kcal/mol for CME_b, −15.4422 ± 1.5895 kcal/mol for CME_c, and −39.3216 ± 0.7125 kcal/mol for CME_d. The selected CME-tyrosinase complexes demonstrated conformational consistency throughout MD simulations, with RMSD analysis and binding free energy (Fig. S7 and Table S2).

In mTYR, CME_a and CME_b coordinate with CuA and CuB, respectively. Notably, CME_b, which did not chelate with any copper ion in the docking conformation, establishes coordination with CuB during the molecular dynamics simulation (Fig. 8a, b). Compared to the docking pose in hTYR, CME_c loses the hydrogen bond with H348 and shifts closer to the CuA site during the simulation, whereas CME_d exhibits only minor conformational changes (Fig. 8e, f).

The RMSD of CME_a is relatively stable, while CME_b shows fluctuation during the first 200 ns (Fig. 8, Fig. S7). MD simulations showed that CME_b’s binding mode changes in the first 200 ns, compared to the docking pose, CME preferentially interacted with the C1 region while chelating copper ions (Fig. 8c), In the two repeated computational simulations, CME_b_r1 also shows such Conformational Changes in Fig. S8. It implies that the original docking conformation of CME_b may not be a reliable binding mode. RMSD analysis (Fig. 8g) shows that the backbone atoms in the CME_c binding mode are relatively stable for the first 300 ns, with deviations around 320 ns and 430 ns. In contrast, CME_d maintains stability around 1 Å, indicating better overall stability.

The RMSF curves of the two conformations in mTYR are very similar (Fig. 8d). Combined with the RMSD analysis, it can be inferred that after the fluctuation in the first 200 ns, the conformation of CME_b undergoes changes, making it more similar to the characteristics of CME_a.In the CME_c binding mode, the L1 and L4 regions exhibit significant fluctuations during the simulation (Fig. 8h). For CME_d, D180 and R289 form stable hydrogen bonds with the N- and C-termini of CME, respectively, stabilizing the L1 and L4 regions around the metal site and resulting in relatively smaller RMSF values. The extensive hydrogen bonds formed between CME_d and the pocket residues lead to greater stability in the surrounding residues compared to CME_c (Fig. 8h).

MD conformations and trajectory analysis for CME: (a) MD-stable conformations of CME_a; (b) MD-stable conformations of CME_b; (c) RMSD of mTYR backbone atoms; (d) RMSF of mTYR residues (300ns ~ 500ns), with red and blue scatter points marking the parameters of residues within 4 Å of the ligand in their binding modes; (e) MD-stable Conformations of CME_c; (f) MD-stable Conformations of CME_d; (g) RMSD of hTYR backbone atoms; (h) RMSF of hTYR residues (300ns ~ 500ns), with red and blue scatter points marking the parameters of residues within 4 Å of the ligand in their binding modes.

For CME_a, the key residues in the C1 region, N259 and E255, are crucial for its binding, further emphasizing the importance of the C1 region in mTYR (Table 4). In the hydrogen bond analysis of CME_b, F263 is also a residue in the C1 region, but no additional stable hydrogen bond interactions are observed. For CME_c, the key residues are E184, N345, and S361 (Table 4). The data indicate that the hydrogen bonds formed in this binding mode are not very reliable, and the fluctuations in the RMSD during the latter part of the simulation confirm the instability of CME_c. For CME_d, the key residues are E184, D180, R289, and Q359 (Table 4), with E184 forming the most frequent and stable interactions, playing a crucial role. The extensive hydrogen bonding network around E184 stabilizes the overall structure.

The MD analysis reveals some differences among these binding modes of CME. Considering the free energy, RMSD, and RMSF, it can be concluded that the long side chain of CME restricts its binding to mTYR. The lack of additional interactions reduces its stability, and the absolute value of the binding free energy is relatively low. In hTYR, Although CME is a shorter tripeptide, it can pull the loop regions towards the pocket center, narrowing and occupying the pocket entrance. Given the stability and extensive hydrogen bonding network, CME_d is evidently more valuable for further studies.

Conclusion

This study utilized AlphaFold3 to model the crystal structure of human tyrosinase. Through molecular docking and molecular dynamics simulations, the binding modes of these natural tyrosinase inhibitors with human tyrosinase (hTYR) and mushroom tyrosinase (mTYR) were systematically explored. At the computational level, the structural differences between the enzyme-inhibitor binding sites of hTYR and mTYR were revealed. These differences significantly impact the binding of inhibitors, leading to variations in their binding modes and affinities with the two enzymes. The study found that the three natural inhibitors exhibited distinct binding orientations when interacting with hTYR and mTYR.

A comparison of the sequence and pocket structures of human and mushroom tyrosinases revealed some similarities in overall structure but limited overlap in the residues around the active site. The hTYR pocket is more acidic, whereas the mTYR pocket is more hydrophobic, indicating some differences between the two enzymes.

The key areas and residues around the pocket in both mTYR and hTYR are noted in Fig. 9. In mTYR, the C1 region and V282 compress the space within the pocket (Fig. 9a), Arbutin, which has a smaller molecular weight, tends to chelate with copper ions, interacting with H84, V282, and F263, with the hydroxyphenyl group directed towards the metal site. The overall binding position is at the top of the pocket (Fig. 4a). Both GSH and CME also tend to chelate with copper ions, and their respective conformations are GSH_a and CME_a, which interact with residues in the C1 region. Notably, N259 and E255 in the C1 region are critical residues. In the dynamic simulation of GSH_a, the conformation exhibiting a hydrogen bond between N259 and the ligand occurs 100% of the time, while E255 appears over 95% (Table 3). In the dynamic simulation of CME_a, the conformations where these two residues form hydrogen bonds with the ligand represent more than half of all conformations with hydrogen bonds. These two residues are essential for the binding of GSH and CME to the pocket in both GSH_a and CME_a conformations.

In hTYR, arbutin exhibited two potential binding modes, Arbutin_a and Arbutin_b. Compared to the more exposed copper-binding site in mTYR, the pocket of hTYR offers more space for arbutin to adopt various orientations. The rich polar and acidic amino acids in the L2 and L4 regions of hTYR stabilize arbutin in this area, allowing it to successfully chelate with copper ions. Glutathione, with its glutamic acid and cysteine residues linked by a γ-amide bond, exhibits greater flexibility, characterized by a relatively shorter side chain, making it easier to extend into the dual copper-binding site and chelate with copper ions. Notably, GSH is more likely to bind to the L2 and L4 regions near CuA. In contrast to arbutin and GSH, CME’s optimal conformation with hTYR does not involve copper ion chelation. Instead, it is positioned closer to the outer side of the pocket, forming hydrogen bonds with several residues in the L2, L3, and L4 regions and being trapped at the pocket entrance. The free energy of CME_d further supports the reliability of this binding mode.

Comparing the binding modes of these natural inhibitors in hTYR and mTYR, it is evident that when searching for inhibitors for mTYR, smaller molecules or short peptides with elongated backbones are more desirable. These types of inhibitors may exhibit better inhibitory effects.

For hTYR, compounds with smaller molecular weights or high flexibility can penetrate the active site with fewer hydrogen bonds and appropriate structures, and more consideration should be given to the potential impact of L2 and L4 (Fig. 9b). Inhibitors structurally similar to CME can effectively limit the movements of loop regions around the pocket through hydrogen bonds with residues R289 and D180, narrowing the pocket entrance and providing competitive inhibition (Fig. 7d). Despite also being a tripeptide like GSH, CME inhibits tyrosinase activity through its longer side chains that tend to close the pocket entrance. This inhibition mode in hTYR is noteworthy, as it suggests that the search for and optimization of efficient and safe peptide-based inhibitors may become a key direction in the development of human tyrosinase inhibitors. These structural characteristics hold significant value for the design of novel inhibitors.

The data in this study are insufficient to fully simulate all relevant factors. This study only covers a portion of natural tyrosinase inhibitors, and the results are inadequate to encompass all types of tyrosinase inhibitors. Future research can expand to include more natural products as well as the screening and optimization of synthetic inhibitors, particularly those with higher efficiency and lower toxicity. With advances in computational technology, combining more effective computational methods with experimental techniques is expected to further enhance the precision of tyrosinase inhibitor identification and drive the development of green chemistry and drug discovery.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.

References

Seo, S. Y., Sharma, V. K. & Sharma, N. Mushroom tyrosinase: recent prospects. J. Agric. Food Chem. 51 (10), 2837–2853. https://doi.org/10.1021/jf020826f (2003).

Simon, J. D. & Peles, D. N. The red and the black. Acc. Chem. Res. 43 (11), 1452–1460. https://doi.org/10.1021/ar100079y (2010).

Solano F. Melanins: Skin pigments and much More—Types, structural models, biological functions, and formation routes. New. J. Sci. 2014(1), 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/498276 (2014).

Jiménez, M. & García-Carmona, F. Hydrogen peroxide-dependent 4-t-butylphenol hydroxylation by tyrosinase–a new catalytic activity. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1297 (1), 33–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/0167-4838(96)00094-5 (1996).

Brenner, M. & Hearing, V. J. The protective role of melanin against UV damage in human skin. Photochem. Photobiol. 84(3), 539–549. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-1097.2007.00226.x (2008).

Lambert, M. W., Maddukuri, S., Karanfilian, K. M., Elias, M. L. & Lambert, W. C. The physiology of melanin deposition in health and disease. Clin. Dermatol. 37 (5), 402–417. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clindermatol.2019.07.013 (2019).

Zolghadri, S., Bahrami, A., Khan, M. T. H., Munoz-Munoz, J., Garcia-Molina, F., Garcia-Canovas, F. & Saboury, A. A. A comprehensive review on tyrosinase inhibitors. J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem. 34 (1), 279–309. https://doi.org/10.1080/14756366.2018.1545767 (2019).

Rosa, G. P., Palmeira, A., Resende, D. I. S. P., Almeida, I.F., Kane-Pagès, A., Barreto, M. C., Sousa, E. & Pinto, M. M. M. Xanthones for melanogenesis inhibition: molecular Docking and QSAR studies to understand their anti-tyrosinase activity., G. P. et al. Xanthones for melanogenesis inhibition: molecular Docking and QSAR studies to understand their anti-tyrosinase activity. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 29 (1), 115873. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bmc.2020.115873 (2021).

Al-Rooqi, M. M., Sadiq, A., Obaid, R. J., Ashraf, Z., Nazir, Y., Jassas, R. S., Naeem, N., Alsharif, M. A., Shah, S. W. A., Moussa, Z., Mughal, E. U., Farghaly, A. R. & Ahmed, S. A. Evaluation of 2,3-Dihydro-1,5-benzothiazepine derivatives as potential tyrosinase inhibitors: in vitro and in Silico studies. ACS Omega 8 (19), 17195–17208. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.3c01566 (2023).

Choi, J., Choi. K., Park, S. J., Kim, S. Y. & Jee, J. Ensemble-Based virtual screening led to the discovery of new classes of potent tyrosinase inhibitors. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 56 (2), 354–367. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jcim.5b00484 (2016).

Gou, L., Lee, J., Yang, J., Park, Y., Zhou, H. M., Zhan, Y. & Lü, Z. R. The effect of alpha-ketoglutaric acid on tyrosinase activity and conformation: kinetics and molecular dynamics simulation study. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 105 (3), 1654–1662.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2016.12.015 (2016).

Cheng, J. X., Li, L. Q., Cai, J., Zhang, C. F., Akihisa, T., Li, W., Kikuchi, T., Liu, W. Y., Feng, F. & Zhang, J. Phenolic compounds from Ficus hispida l.f. As tyrosinase and melanin inhibitors: biological evaluation, molecular docking, and molecular dynamics. Journal Mol. Structure. 1244(3), 130951. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molstruc.2021.130951 (2021).

Tunyasuvunakool, K., Adler, J., Wu, Z., Green, T., Zielinski, M., Žídek, A., Bridgland, A., Cowie, A., Meyer, C., Laydon, A., Velankar, S., Kleywegt, G. J., Bateman, A., Evans, R., Pritzel, A., Figurnov, M., Ronneberger, O., Bates, R., Kohl, S. A. A., Potapenko, A., Ballard, A. J., Romera-Paredes, B., Nikolov, S., Jain, R., Clancy, E., Reiman, D., Petersen, S., Senior, A. W., Kavukcuoglu, K., Birney, E., Kohli, P., Jumper, J. & Hassabis, D. Highly accurate protein structure prediction for the human proteome. Nature 596 (26), 590–596. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-03828-1 (2021).

Abramson, J., Adler, J., Dunge, Jack., Evans, R., Green, T., Pritzel, A., Ronneberger, O., Willmore, L., Ballard, A. J., Bambrick, J., Bodenstein, S. W., Evans, D. A., Hung, C. C., O’Neill, M., Reiman, D., Tunyasuvunakool, K., Wu, Z., Žemgulytė, A., Arvaniti, E., Beattie, C., Bertolli, O., Bridgland, A., Cherepanov, A., Congreve, M., Cowen-Rivers, A. I., Cowie, A., Figurnov, M., Fuchs, F. B, Gladman, H., Jain, R., Khan, Y. A., Low, C. M. R., Perlin, K., Potapenko, A., Savy, P., Sigh, S., Stecula, A., Thillaisundaram, A., Tong, C., Yakneen, S. Zhng, E. D., Zielinski, M., Žídek, A., Bapst, V., Kohli, P., Jaderberg, M., Hassabis, D. & Jumpe, J. M. Accurate structure prediction of biomolecular interactions with alphafold 3. Nature 630 (13), 493–500. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-07487-w (2024).

Fujieda, N., Umakoshi, K., Ochi, Y., Nishikawa, Y., Yanagisawa, S., Kubo, M., Kurisu, G. & Itoh, S. Copper–Oxygen dynamics in the tyrosinase mechanism. Angew. Chem. 132 (32), 13487–13492. https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.202004733 (2020).

Margarita, K., Goldfeder, M. & Fishman, A. Structure-function correlations in tyrosinases. Protein Science: Publication Protein Soc. 24 (9), 1360–1369. https://doi.org/10.1002/pro.2734 (2015).

Singh, K. G., Umme, U. S., Sushmitha, K. & Veeraraghavan, V. In vivo therapeutic study of repigmentation of depigmented patches in vitiligo disorder isolated tyrosinase of Moringa oleifera and other extracts in Zebra fish embryo. J. Surv. Fisheries Sci. 10 (1S), 6544-6553. (2023).

Arrowitz, C., Schoelermann, A. M., Mann, T., Jiang, L. I., Weber, T. & Kolbe, L. Effective tyrosinase Inhibition by thiamidol results in significant improvement of mild to moderate melasma. J. Invest. Dermatology. 139 (8), 1691–1698.e6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jid.2019.02.013 (2019).

Roggenkamp, D., Dlova, N., Mann, T., Batzer, J., Riedel, J., Kausch, M., Zoric, I. & Kolbe, L. Effective reduction of post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation with the tyrosinase inhibitor isobutylamido-thiazolyl-resorcinol (Thiamidol). Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 43 (3), 292–301. https://doi.org/10.1111/ics.12694 (2021).

Philipp-Dormston, W. G., Echagüe, A. V., Damonte, S. H. P., Riedel, J., Filbry, A., Warnke, K., Lofrano, C., Roggenkamp, D. & Nippel, G. Thiamidol containing treatment regimens in facial hyperpigmentation: an international multi-centre approach consisting of a double-blind, controlled, split-face study and of an open-label, real-world study. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 42 (4), 377–387. https://doi.org/10.1111/ics.12626 (2020).

Mann, T., Gerwat, W., Batzer, J., Eggers, K., Scherner, C., Wenck, H., Stäb, F., Hearing, V. J., Röhm, K. H. & Kolbe, L. Inhibition of human tyrosinase requires molecular motifs distinctively different from mushroom tyrosinase. J. Invest. Dermatology. 138 (7), 1601–1608. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jid.2018.01.019 (2018).

Xu, H. X., Li, X. F., Xin, X., Mo, L., Zou, X. C., Zhao, G. L., Yu, Y. G. & Chen, K. B. Antityrosinase mechanism and antimelanogenic effect of arbutin esters synthesis catalyzed by Whole-Cell biocatalyst. J. Agric. Food Chem. 69 (14), 4243–4252. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jafc.0c07379 (2021).

Lin, Y. F., Hu, Y. H., Lin, H. T., Liu, X., Chen, Y. H., Zhang, S. & Chen, Q. X. Inhibitory effects of propyl gallate on tyrosinase and its application in controlling pericarp Browning of harvested Longan fruits. J. Agric. Food Chem. 61 (11), 2889–2895. https://doi.org/10.1021/jf305481h (2013).

Lee, S. Y., Baek, N. & Nam T. Natural, semisynthetic and synthetic tyrosinase inhibitors. J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem. 31 (1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.3109/14756366.2015.1004058 (2016).

Chen, H., Yao, Y. R., Xie, T. Y., Guo, H. H., Chen S. J., Zhang, Y. P. & Hong, Z. Identification of tyrosinase inhibitory peptides from sea cucumber (Apostichopus japonicus) collagen by in Silico methods and study of their molecular mechanism. Current Protein & Pept. Science. 24 (9), 758-766. (2023).

Ubeid, A. A., Sylvia, D., Nye, C. & Hantash, B. M. Potent low toxicity Inhibition of human melanogenesis by novel indole-containing octapeptides. BBA - Gen. Subj. 1820 (10), 1481–1489. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbagen.2012.05.003 (2012).

Fujimoto, N., Onodera, H., Mitsumori, K., Tamura, T., Maruyama, S. & Ito, A., Changes in thyroid function during development of thyroid hyperplasia induced by kojic acid in F344 rats. Carcinogenesis. 20 (8), 1567–1572. https://doi.org/10.1093/carcin/20.8.1567 (1999).

Sugimoto, K., Nishimura, T., Nomura, K., Sugimoto, K. & Kuriki, T. Inhibitory effects of alpha-arbutin on melanin synthesis in cultured human melanoma cells and a three-dimensional human skin model. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 27 (4), 510–514 (2004).

Li, X. F., Guo, J., Lian, J. Q., Gao, F., Khan, A. J., Wang, T. & Zhang, F., Molecular simulation study on the interaction between tyrosinase and flavonoids from sea Buckthorn. ACS Omega. 6 (33), 21579–21585. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.1c02593 (2021).

Feng, Y. X., Wang, Z. C., Chen, J. X., Li, H. R., Wang, Y. B., Ren, D. F. & Lu, J. Separation, identification, and molecular Docking of tyrosinase inhibitory peptides from the hydrolysates of defatted walnut (Juglans regia L.) meal. Food Chem. 353 (15), 129471. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.129471 (2021).

Meister, A. On the antioxidant effects of ascorbic acid and glutathione. Biochem. Pharmacol. 44 (10), 1905–1915. https://doi.org/10.1016/0006-2952(92)90091-V (1992).

Haaften, R. I. M. V., Haenen, G. R. M. M., Evelo, C. T. A. & Bast, A. Effect of vitamin E on glutathione-dependent enzymes. Drug Metab. Rev. 35 (2), 215–253. https://doi.org/10.1081/dmr-120024086 (2003).

Sonthalia, S., Daulatabad, D. & Sarkar, R. Glutathione as a skin whitening agent: facts, myths, evidence and controversies. Indian J. Dermatol. Venereol. Leprol. 82 (3), 262–272. https://doi.org/10.4103/0378-6323.179088 (2016).

Vangronsveld, J., Cuypers, A., Remans, T. & Jozefczak, M. Glutathione is a key player in Metal-Induced oxidative stress defenses. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 13 (3), 3145–3175. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms13033145 (2012).

Villarama, C. D. & Maibach, H. I. Glutathione as a depigmenting agent: an overview. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 27 (3), 147–153. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-2494.2005.00235.x (2005).

Chai, W. M., Lin, M. Z., Feng, H. L., Zou, Z. R., & Wang, Y. X. Proanthocyanidins purified from fruit pericarp of Clausena lansium (Lour.) Skeels as efficient tyrosinase inhibitors: structure evaluation, inhibitory activity and molecular mechanism. Food Funct. 8 (3), 1043–1051. https://doi.org/10.1039/c6fo01320a (2017).

Chen, Y. R., Chiou, R. Y. Y., Lin, T. Y., Huang, C. P., Tang, W. C., Chen, S. T. & Lin, S. B. Identification of an alkylhydroquinone from Rhus succedanea as an inhibitor of tyrosinase and melanogenesis. J. Agric. Food Chem. 57 (6), 2200–2205.https://doi.org/10.1021/jf802617a (2009).

Bordbar, S., Anwar, F. & Saari, N. High-Value components and bioactives from sea cucumbers for functional Foods—A review. Mar. Drugs 9 (10), 1761–1805. https://doi.org/10.3390/md9101761 (2011).

Moussa, R. M. & Wirawati, I. Observations on some biological characteristics of Holothuria polii and Holothuria sanctori from mediterranean Egypt. International J. Fisheries Aquat. Studies. 6 (3), 351-357. (2018).

Kim, S. J., Park, S. Y., Hong, S. M., Kwon, E. H. & Lee, T. K. Skin whitening and anti-corrugation activities of glycoprotein fractions from liquid extracts of boiled sea cucumber. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Med. 9 (10), 1002–1006. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apjtm.2016.08.001 (2016).

Wang, J. F., Wang, Y. M., Tang, Q. J. & Wang, Y. Antioxidation activities of low-molecular-weight gelatin hydrolysate isolated from the sea cucumber Stichopus japonicus. J. Ocean. Univ. China. 9 (1), 94–98. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11802-010-0094-9 (2010).

Kwon, T. R., Oh, C. T., Bak, D. H., Kim, J. H., Seok, J., Lee, J. H., Lim, S. H., Yoo, K. H., Kim, B. J. & Kim, H. Effects on skin of Stichopus japonicus viscera extracts detected with saponin including holothurin A: Down-regulation of melanin synthesis and Up-regulation of neocollagenesis mediated by ERK signaling pathway. J. Ethnopharmacol. 226 (15), 73–81.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2018.08.007 (2018).

Husni, A., Jeon, J. S., Um, B. H., Han, N. S. & Chung, D. H. Tyrosinase Inhibition by water and ethanol extracts of a Far Eastern sea cucumber, Stichopus japonicus. J. Sci. Food. Agric. 91 (9), 1541–1547. https://doi.org/10.1002/jsfa.4335 (2011).

Sakkiah, S., Arooj, M., Cao, G. P. & Lee, K. W. Insight the C-site pocket conformational changes responsible for Sirtuin 2 activity using molecular dynamics simulations. PloS One 8 (3), e59278. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0059278 (2013).

Thangapandian, S., John, S., Arooj, M. & Lee, K. W. Molecular dynamics simulation study and hybrid pharmacophore model development in human LTA4H inhibitor design. PloS One 7 (4), e34593. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0034593 (2012).

Arooj, M., Sakkiah, S., Cao, G. P., Kim, S., Arulalapperumal, V. & Lee, K. W. Finding off-targets, biological pathways, and target diseases for chymase inhibitors via structure-based systems biology approach. Proteins. 83 (7), 1209–1224. https://doi.org/10.1002/prot.24677 (2015).

Case, D. A., Belfon, A. H., Ben-Shalom, K. A. A., Berryman, I. Y. & Brozell, J. T. SR et al. Amber 2022 reference manual: (Covers Amber22 and AmberTools22). 1013. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.31337.77924 (2022).

Hollingsworth, S. A. & Dror, R. O. Molecular dynamics simulation for all. Neuron. 99 (6), 1129–1143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2018.08.011 (2018).

Roe, D. R. & Cheatham, T. E. PTRAJ and CPPTRAJ: Software for processing and analysis of molecular dynamics trajectory data. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 9 (7), 3084–3095. https://doi.org/10.1021/ct400341p (2013).

Molecular Operating Environment (MOE). C. C. G. U., Sherbrooke St. W., Montreal, QC H3A 2R7, 910–1010 (2025).

Li, P. F. & Merz, K. M. MCPB.py: A Python based metal center parameter builder. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 56 (4), 599–604.https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jcim.5b00674 (2016).

Li, P. f. & Merz, K. M. Parameterization of a dioxygen binding metal site using the mcpb.py program. Methods Mol. Biology 2199, 257–275. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-0716-0892-0_15 (2021).

Jorgensen, W. L., Chandrasekhar, J., Madura, J. D., Impey, R. W. & Klein, M. L. Comparison of simple potential functions for simulating liquid water. The Journal of Chemical Physics. 79, 926–935. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.445869 (1983).

Favre, E., Daina, A., Carrupt, P. A. & Nurisso, A. Modeling the Met form of human tyrosinase: a refined and hydrated pocket for antagonist design. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 84 (2), 206–215. https://doi.org/10.1111/cbdd.12306 (2014).

Tian, C., Kasavajhala, K., Belfon, K. A. A., Raguette, L., Huang, H., Migues, A. N., Bickel, J., Wang, Y. Z., Pincay, J., Wu, Q. & Simmerling, C. ff19SB: Amino-Acid-Specific protein backbone parameters trained against quantum mechanics energy surfaces in solution. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 16 (1), 528–552. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jctc.9b00591 (2020).

Grand, S. L., Götz, A. W. & Walker, R. C. SPFP: speed without compromise—A mixed precision model for GPU accelerated molecular dynamics simulations. Comput. Phys. Commun. 184 (2), 374–380. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpc.2012.09.022 (2013).

Romelia, S. F., Götz, A. W., Poole, D., Grand, S. L. & Wallker, R. C. Routine microsecond molecular dynamics simulations with AMBER on gpus. 2. Explicit solvent particle mesh Ewald. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 9(9), 3878–3888. https://doi.org/10.1021/ct400314y (2013).

Götz, A. W., Williamson, M. J., Xu, D., Poole, D., Grand, S. L. & Wallker, R. C. Routine microsecond molecular dynamics simulations with AMBER on gpus. 1. Generalized born. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 8 (5), 1542–1555. https://doi.org/10.1021/ct200909j (2012).

Nunes, J. A., Araújo, R. S. A., Silva, F. N., Cytarska, J., Łączkowski, K. Z., Cardoso, S. H., Mendonça-Júnior, F. J. B. & Silva-Júnior, E. F., Coumarin-Based compounds as inhibitors of tyrosinase/tyrosine hydroxylase: synthesis, kinetic studies, and in Silico approaches. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24 (6), 5216–5216. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24065216 (2023).

Ismaya, W. T., Rozeboom, H. J., Weijn, A., Mes, J. J., Fusetti, F., Wichers, H. J. & Dijkstra, B. W. Crystal structure of agaricus bisporus mushroom tyrosinase: identity of the tetramer subunits and interaction with tropolone. Biochemistry 50 (24), 5477–5486. https://doi.org/10.1021/bi200395t (2011).

Hassan, M., Ashraf, Z., Abbas, Q., Raza, H. & Seo, S. Y. Exploration of novel human tyrosinase inhibitors by molecular modeling, Docking and simulation studies. Interdisc. Sci. Comput. Life Sci. 10 (1), 68–80. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12539-016-0171-x (2018).

Antonio, G. J., Jose, A. T. P., Jose, B., José, N. R. L., Jose, T. & Francisco, G. C. Action of tyrosinase on alpha and beta-arbutin: A kinetic study. PloS One. 12 (5), e0177330. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0177330 (2017).

Nokinsee, D., Shank, L., Lee, V. S. & Nimmanpipug, P. Estimation of Inhibitory Effect against Tyrosinase Activity through Homology Modeling and Molecular Docking. Enzyme Research. 262364. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/262364 (2015).

Tang, H. C. & Chen, Y. C. Identification of tyrosinase inhibitors from traditional Chinese medicines for the management of hyperpigmentation. SpringerPlus 4, 184. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40064-015-0956-0 (2015).

Mamelona, J., Saint-Louis, R. & Pelletier, É. Nutritional composition and antioxidant properties of protein hydrolysates prepared from echinoderm byproducts. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 45 (1), 147–154. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2621.2009.02114.x (2010).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.Z. is the supervisor of this study and edited the manuscript, S.Z. wrote the original manuscript and responsible for part of the computational simulations, T.J., T.S. and Z.X. are responsible for other part of the computational simulations, W.L. prepared all figures, X.S. analyzed the data of study. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zheng, Z., Zhang, S., Jiang, T. et al. Theoretical studies of arbutin, glutathione, and sea cucumber extracts as inhibitors of tyrosinase. Sci Rep 15, 32851 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-06316-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-06316-y