Abstract

Massive-multiple input and Multiple Outputs Non orthogonal multiple access (M-MIMO–NOMA) systems require efficient signal detection techniques to mitigate interference and enhance spectral efficiency, especially under diverse channel conditions and varying modulation schemes. This study investigates the performance of the Successive Interference Cancellation with Reinforcement Learning (SIC-RL) detector compared to conventional methods, including the Minimum Mean Square Error (MMSE), Maximum Likelihood Detection (MLD), Approximate Message Passing (AMP), Gauss–Seidel (GS), Conjugate Gradient (CG), and zero-forcing equalizer (ZFE). The analysis was conducted for 16-QAM, 64- Quadrature Amplitude Modulation (QAM), and 256-QAM in Rayleigh fading channels with 10% error. The simulation results indicate that SIC-RL outperforms traditional detectors in terms of bit error rate (BER), power spectral density (PSD), and computational complexity. At a BER of 10⁻3, SIC-RL achieves an SNR 11.2 dB (512-QAM), 6.6 dB (256-QAM), 5 dB (64-QAM) and 5.8 dB (64-QAM with 10% channel error) as compared with conventional methods. The PSD analysis shows that SIC-RL exhibits a 35% and 20% lower spectral leakage compared to contemporary methods, ensuring better spectral efficiency for diverse channel conditions. In terms of computational complexity, SIC-RL achieves near-logarithmic growth with the number of antennas, significantly reducing the processing burden compared to MLD, which has exponential complexity. Although ZFE and CG are computationally efficient, they suffer from noise amplification and poor BER performance. GS and AMP balance complexity and performance but still fall short of SIC-RL gains. Overall, SIC-RL has emerged as an optimal solution for massive MIMO signal detection, achieving a superior trade-off between BER, PSD, and computational efficiency across diverse modulation schemes and channel conditions. Critically, SIC-RL achieves near-quadratic complexity \(O(N_{t}^{2} ),\) contrasting the exponential complexity \(O(M^{{N_{{\text{t}}} }} )\) of MLD and the cubic complexity \(O(N_{t}^{3} )\) of MMSE and ZFE, making it scalable for large antenna arrays. Iterative methods such as AMP, GS, and CG achieve lower complexity, but suffer from convergence issues or degraded BER. Despite requiring initial training, SIC-RL provides a favorable trade-off between the detection accuracy and processing cost, positioning it as a computationally efficient and high-performance detector for next-generation MIMO–NOMA systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Massive multiple-input multiple-output (MIMO) combined with non-orthogonal multiple access (NOMA) has become a cornerstone technology for next-generation wireless communication systems, particularly in 5G and the emerging 6G networks. Massive MIMO boosts the spectral efficiency by employing a large number of antennas at the base station, enabling spatial multiplexing for multiple users. Concurrently, NOMA allows multiple users to share the same time and frequency resources by employing power- or code-domain multiplexing, thereby increasing user connectivity and resource utilization. While the integration of MIMO and NOMA promises substantial performance gains, it also introduces significant signal detection challenges owing to intensified multiuser interference (MUI), complex channel characteristics, and increased computational overhead1. Signal detection is a critical aspect in Massive MIMO–NOMA (M-MIMO–NOMA) systems to ensure reliable communication, an improved bit error rate (BER), and efficient power allocation. Traditional detection methods, such as the minimum mean square error (MMSE) and zero-forcing (ZF), are less effective in the presence of severe MUI. To address these limitations, advanced techniques, such as successive interference cancellation (SIC), maximum likelihood detection (ML), and machine learning-based methods, have been proposed. Among them, Approximate Message Passing (AMP) stands out as a low-complexity, iterative technique based on belief propagation that is suitable for detecting signals in sparse MIMO environments. However, AMP’s performance of AMP deteriorates in non-Gaussian channels owing to convergence issues2. Similarly, iterative algorithms, such as Gauss–Seidel (GS) and Conjugate Gradient (CG), offer a balance between accuracy and computational load by avoiding costly matrix inversion, making them suitable for large-scale systems. Despite these advances, the dynamic nature of wireless environments, particularly under Massive MIMO–NOMA configurations, limits the performance of static detection strategies. SIC remains a widely used technique in NOMA for separating superimposed signals, but it suffers from error propagation and reduced efficacy under time-varying or low-SNR conditions3,4. In this context, reinforcement learning (RL) has emerged as a promising solution that offers adaptive and data-driven approaches to dynamically optimize detection strategies. By learning from the environment, RL enhances the robustness of SIC against interference and channel variations, thereby improving the system reliability and user fairness5. However, existing studies on RL-based signal detection have limitations. Conventional SIC-based models often assume ideal channel estimation and static user behavior, which are unrealistic in practical deployments6. Moreover, RL approaches typically require large datasets and high computational resources, which constrain their adaptability to real-time scenarios. Additionally, the spatial correlation inherent in massive MIMO channels has not been fully exploited by many current RL frameworks, leading to suboptimal detection accuracy. To address these challenges, there is a growing need for hybrid detection schemes that combine the advantages of SIC and RL. Such hybrid approaches aim to overcome error propagation, reduce computational complexity, and enhance adaptability under various channel conditions. The core objective of this study is to develop a hybrid Successive Interference Cancellation with Reinforcement Learning (SIC-RL) signal detection framework tailored for M-MIMO–NOMA systems, focusing on improving detection accuracy, minimizing latency, and enhancing system robustness under interference and noise7. By intelligently integrating RL with SIC, the proposed method seeks to optimize real-time detection strategies, making it highly suitable for large-scale, interference-prone environments characteristic of 5G and beyond8.

The proposed hybrid signal detection in Massive MIMO–NOMA enhances detection efficiency by integrating traditional SIC with RL-based optimization. SIC mitigates multiuser interference sequentially, but its performance degrades in complex environments. RL dynamically adjusts detection strategies by learning from signal patterns and channel conditions, thereby improving the robustness against noise and interference. This hybrid approach balances the computational complexity and detection accuracy, making it highly effective for large-scale NOMA networks in 5G and beyond, ensuring enhanced spectral efficiency and user fairness. By intelligently balancing computational efficiency and adaptability, the proposed technique improves the spectral efficiency and system reliability, making it a robust solution for next-generation Massive MIMO–NOMA networks. Despite recent progress in the signal detection of Massive-MIMO–NOMA systems, current approaches such as SIC coupled with RL are challenged by several issues. These exhibit poor adaptability to various channel conditions and inconsistent performance under various modulation schemes. Most current designs are optimized for optimal or static cases and fail to be robust in dynamic or actual fading scenarios. Moreover, learning models tend to have very high complexity and slow convergence, rendering real-time processing problematic. There has also been insufficient investigation into modulation-aware and channel-aware adaptive RL methods, indicating that more efficient, scalable, and generalizable detection schemes in real-world 5G/6G systems are necessary. This study makes the following major contributions to massive MIMO signal detection.

-

1.

Development of SIC-RL for Better Signal Detection: We introduce a new Successive Interference Cancellation with Reinforcement Learning (SIC-RL) approach that considerably enhances signal detection under 16-QAM, 64-QAM, 256-QAM, and 512-QAM modulation. This approach efficiently reduces interference and compensates for Rayleigh fading channels with up to 10% channel estimation error, outperforming traditional methods such as MMSE, Maximum Likelihood Detection (MLD), AMP, GS, CG, and zero-forcing equalizer (ZFE).

-

2.

Comprehensive Performance Evaluation: Large-scale simulations show that SIC-RL provides better SNR gains at BER = 10–3, i.e., 11.2 dB (512-QAM), 6.6 dB (256-QAM), 5 dB (64-QAM), and 5.8 dB (64-QAM with 10% channel error), compared to state-of-the-art detectors. Moreover, power spectral density (PSD) analysis shows that SIC-RL minimizes spectral leakage by 35% and 20%, providing better spectral efficiency for massive MIMO systems under various channel conditions.

-

3.

Computational Complexity Reduction: In comparison to conventional detectors such as MLD, which have exponential complexity, SIC-RL achieves near-logarithmic growth in complexity, which makes it extremely scalable for massive antenna arrays. This makes real-time implementation efficient, with an improved trade-off between BER, PSD, and computational efficiency, rendering SIC-RL the best option for future wireless networks.

-

4.

The proposed method advances academia by introducing an intelligent adaptive signal detection approach, bridging machine learning, and wireless communication. The industry benefits from improved spectral efficiency and lower latency in the next-generation networks. Societally, enhanced connectivity supports applications, such as smart cities and IoT, ensuring seamless, energy-efficient, and high-capacity communication systems.

Literature review

The authors in9 proposed a deep learning-based method for shared spectrum environment signal detection and classification, utilizing convolutional neural networks (CNNs) to enhance the performance in dynamic wireless environments. This research clearly demonstrates the interference and channel variation robustness of deep learning. It suffers from the limitation that it depends heavily on large amounts of labeled training data, which can limit its real-world applicability, particularly in fast-evolving spectrum environments. In10, the authors investigated deep learning-based signal detection in massive MIMO–NOMA systems and presented better detection accuracy along with interference robustness. This research successfully incorporated neural networks for performance improvement over the traditional approaches. Nevertheless, this work does not include a proper complexity analysis, and real-time implementability is in question. Moreover, the generalizability of the model to various channel conditions needs to be verified. A comparative study using hybrid AI approaches would strengthen the results. The authors in11 proposed deep-learning-based MIMO systems with an open-loop autoencoder to optimize end-to-end wireless communication. This work demonstrates the performance improvements in channel estimation and signal detection. However, its drawback is the use of idealized assumptions, that is, perfect Channel State Information (CSI) availability, which can impede real-world applications. Furthermore, the computational complexity and training overhead can pose deployment issues in resource-constrained settings. In12. Researchers have explored deep learning-based signal detection in co-channel interference, displaying better detection capability than conventional algorithms. This study successfully incorporated neural networks to prevent interference and secure communication reliability. Nevertheless, real-time utilization is constrained by the use of large amounts of training data and computational power. The work also mostly concerned simulated environments with no practical applicability verification. Real-world deployability and the reduction of complexity are areas for future research. The writers in13 introduced a deep learning-powered multi-signal detection framework for carrier frequency and bandwidth estimation, showing high performance in challenging environments. In this study, CNNs and LSTMs were successfully combined to improve the signal classification. Its dependency on large datasets and computationally expensive training hinder real-time adaptability. The performance in dynamic, low-SNR environments also requires further confirmation, limiting practical applications within resource-constrained wireless networks. The authors in14 suggested an ML method for signal detection in low-SNR scenarios with enhanced classification performance compared with conventional methods. Deep learning models were used to promote noise robustness. Nonetheless, the research mainly concentrated on simulated data; thus, its applicability in real-world cases is modest. Moreover, the computational requirements of the proposed models may delay their deployment within resource-limited devices. Future research could work on generalization to varied signal scenarios as well as real-world data. The authors of15 proposed an efficient hybrid iterative strategy for signal detection in massive MIMO uplinks for an AWGN channel. This method enhances the accuracy of detection while reducing the computational expense. The drawback of this study is that it treats AWGN channels alone, without discussing practical scenarios for fading. Furthermore, the paper does not provide a critical comparison of the approach with state-of-the-art deep learning-based detection methodologies that are becoming mainstream for massive MIMO systems. The authors in16 introduce a novel method for MIMO NOMA signal detection by combining SIC with ML methods. The hybrid technique is designed to improve the detection performance and system capacity in challenging communication environments. Although the combination of SIC and ML is promising, this paper does not adequately discuss the possible computational complexity and latency problems inherent in ML methods, which may impact real-time application viability. Future studies should concentrate on refining these factors to make the model practically deployable in real situations. In17, the authors proposed a low-complexity signal-detection network based on the Gauss–Seidel iterative method for massive MIMO systems. This method lowers the computational complexity without sacrificing the detection accuracy, making it applicable to large-scale scenarios. The authors present a theoretical analysis and simulation results to support performance improvements. The limitation of this work is that it depends on idealized system assumptions, which do not necessarily reflect practical hardware degradations or realistic channel conditions that could influence performance in practical implementations. The authors in18 introduce a Bi-LSTM-based deep learning solution for 5G signal detection and channel estimation with better accuracy than conventional techniques. This research successfully highlights the advantage of using deep learning to improve wireless communication. However, the study does not include a thorough complexity analysis; therefore, the computationally acceptable nature of the proposed model for real-time implementation is uncertain. In addition, the study does not fully compare its method with the current best techniques, restricting the analysis of its relative performance and scalability. The authors of19 presents a comparative review of data detection methods for 5G massive MIMO systems based on performance, complexity, and sustainability. It successfully compared many detection algorithms and their trade-offs. The study is mostly based on theoretical analysis and does not extend the extensive real-world verification. It also did not investigate the effects of hardware impairments and energy efficiency in real-world deployments. Future work should involve experimental observations and investigate new deep-learning-based detection methods. The authors in20 introduced a decoupled signal detection (DSD) method for the uplink of 5G heterogeneous networks’ massive MIMO systems. This technique enables the base station to decouple uplink signals from different user classes to improve detection efficiency. The authors derived a mathematical model for centralized and distributed antenna configurations and proved that DSD offers superior performance when combined with linear and successive interference cancellation methods. However, the research fails to comprehensively cover the effects of hardware faults and real-world environmental conditions on the suggested DSD algorithm, which might influence its application in real-world scenarios. The authors in21 investigated the influence of antenna spacing on Differential Spatial Modulation (DSM) and Spatial Modulation (SM) in 5G compact wireless devices. It effectively analyzes the performance variations under constrained antenna configurations. However, the limitations include a lack of experimental validation, restricted channel models, and the absence of power efficiency and hardware complexity considerations in practical deployment scenarios. Table 1 indicated the comparative table of proposed and published work:

Problem formulation

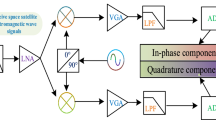

MIMO–NOMA is a key technology for next-generation wireless networks that enhances the spectral efficiency and user connectivity. Combining MIMO spatial multiplexing with NOMA’s power-domain multiplexing allows multiple users to share the same time and frequency resources, improving system capacity and fairness. Unlike conventional orthogonal schemes, MIMO–NOMA supports massive connectivity, making it ideal for 5G and beyond applications. It efficiently manages user interference through successive interference cancellations while optimizing power allocation. This hybrid approach significantly boosts network throughput, reduces latency, and supports diverse applications including IoT, smart cities, and ultra-reliable communications. Massive MIMO is one of the central technologies in contemporary wireless communication, which utilizes a large number of antennas at the base station to serve multiple users simultaneously. This significantly increases the spectral and energy efficiency and ensures strong connectivity in dense networks. Signal detection in massive MIMO systems is extremely complicated owing to several challenges. First, the huge channel matrix amplifies the computational complexity of the detection algorithms. Conventional techniques, such as ML detection, are rendered impractical with exponential complexity22. Second, hardware impairments and channel estimation errors, such as phase noise and nonlinear distortion, impair the detection performance. Third, the spatial correlation between the antennas makes interference mitigation more challenging. Although linear detectors such as ZFE and MMSE provide suboptimal but practical solutions, sophisticated techniques, including message passing and deep learning-based detectors, are on the rise to effectively manage complexity. Therefore, the design of high-performance, low-complexity detection algorithms is an important problem in massive MIMO systems. Figure 1 shows an M-MIMO system.

Let us consider a massive MIMO system with \({N}_{t}\) transmit antennas and \({N}_{r}\) receive antennas, where \({N}_{r}\gg {N}_{t}\). The received signal in a narrowband flat-fading channel can be modelled as23:

where \(y\in {\mathbb{C}}^{{N}_{r}\times 1}\) is the received signal vector, \(H\in {\mathbb{C}}^{{N}_{r}\times {N}_{t}}\) is the channel matrix with independent and identically distributed complex Gaussian entries \({h}_{ij}\sim {\mathbb{C}}\mathbb{\aleph }(\text{0,1})\) , \(x\in {\mathbb{C}}^{{N}_{t}\times 1}\) is the transmitted signal vector drawn from a modulation constellation, and \(n\in {\mathbb{C}}^{{N}_{r}\times 1}\) is the noise. The goal of signal detection is to estimate the transmitted vector \(x\) given the received signal \(y\) and channel matrix \(H\). The optimal detection problem is formulated as follows.

where \(\mathcal{X}\) is the set of transmitted symbols. Because of the high complexity of ML detection (exponential in \({N}_{t}\)), suboptimal practical methods, such as ZF, MMSE, and MPA, are usually used. For systems with hardware impairments, an additional distortion term \(\eta\) is introduced, modifying the received-signal equation as follows:

where \(\eta \sim {\mathbb{C}}\mathbb{\aleph }(0,{\sigma }_{\eta }^{2} I)\) represents the nonlinear distortions and phase noise. Robust detection algorithms, such as RL-based approaches integrated with SIC, should be utilized to mitigate these impairments and improve performance. The SIC-RL detector solves massive MIMO signal detection problems through iterative interference mitigation and RL-aided decision optimization. SIC detects symbols sequentially with lower error propagation, and RL adjusts the detection thresholds according to channel conditions and hardware distortions. The proposed method increases robustness against nonlinearity and noise and achieves better performance than conventional methods, such as MMSE24. SIC-RL learns optimal action policies and achieves enhanced detection accuracy and improved computational efficiency. Thus, it is applicable to realistic large-scale MIMO scenarios with hardware distortions.

Proposed system model

SIC-RL is a sophisticated signal-detection method aimed at improving the performance of massive MIMO systems. Conventional SIC iteratively detects and cancels the interference from previously detected symbols to enhance the signal recovery of overloaded MIMO systems. Conventional SIC has the drawback of error propagation, particularly under high noise and correlated channel conditions. RL is incorporated into SIC to optimize the detection sequence and make the detection process more interference-robust. In SIC-RL, an RL agent learns to dynamically choose the best order of symbol detection to minimize error propagation. The system is represented as a Markov Decision Process (MDP), with states being the partially detected symbol vector, actions being the choice of the next symbol to decode, and rewards derived from detection accuracy and interference reduction. Using algorithms such as Q-learning or deep reinforcement learning (DRL), the agent learns the optimum detection sequence with time. This method largely improves the massive MIMO performance by enhancing the detection accuracy, particularly under high user density and hardware impairment cases. SIC-RL is adaptive to changing channel conditions and alleviates deep fades and correlated interference that worsen traditional linear detectors such as ZF and MMSE. In addition, it has less computational complexity than ML detection; therefore, it is more suitable for real-time processing. SIC-RL is also resistant to nonlinear hardware distortion, and it is applicable in practical implementations for 5G and the future. SIC-RL, with its clever utilization of reinforcement learning, increases spectral efficiency, decreases BER, and provides guaranteed communication in large-scale MIMO systems. Therefore, it is a great candidate for next-generation wireless networks. SIC, together with RL, for signal detection in a massive MIMO system attempts to iteratively detect and improve symbol estimates and learn an optimal detection policy. The received signal in a narrowband massive MIMO system is expressed as

SIC detects MIMO signals by sequentially decoding and cancelling out stronger signals to reduce interference from weaker signals. It initially sorts users according to their signal strength or Signal-to-Interference-plus-Noise Ratio (SINR), detects the strongest signal, and then cancels out its contribution from the observed signal. It repeats for other signals, thereby gradually decreasing interference. While SIC enhances the detection accuracy, it is subject to error propagation if the initial decisions are erroneous. Additions such as RL-based refinement enhance the robustness of real-world implementation. The SINR for each detected symbol \({x}_{k}\) at the \(k-th\) iteration is

where \({h}_{k}\) is the effective channel coefficient of the selected user. The decoding order was determined by sorting the SINR values in the descending order. For the detected symbol \(\overline{{x }_{k}}\), the estimated signal is

After detecting \(\overline{{x }_{k}}\), the received signal is updated by cancelling the detected component as follows:

RL improves MIMO detection through dynamic symbol-decision refinement learned through policies. It optimizes the detection order, reduces error propagation, and accommodates changes in the channel conditions. Through the use of reward-based learning, RL-based detectors enhance the signal estimation precision, leading to more robust MIMO systems against interference and hardware impairments. The RL-based reward function for improving signal detection is given by:

where \(\overline{{x }_{k}}\) denotes the estimated symbol vector at step \(k\). The RL agent updates the detection policy \(\pi (x\mid y)\) using a Q-learning update. In a Rayleigh fading channel, the channel matrix \(H\) is typically modelled as

where \({H}_{true}\) is the true Rayleigh fading channel matrix, \(E\in {\mathbb{C}}^{{N}_{r}\times {N}_{t}}\sim {\mathbb{C}}N(0,{\sigma }_{e}^{2})\) represents the channel estimation error, modelled as an independent Gaussian matrix, and \({\sigma }_{e}^{2}=0.{1}^{2}=0.01\) ensures a 10% estimation error. Thus, the estimated channel used in SIC-RL detection is

The received signal considering channel estimation error is then:

This error affects SIC-RL-based detection, requiring the RL agent to learn robust policies that compensate for the biased channel estimate. The Q-learning update in RL-based signal detection optimizes decision making by learning from past actions, refining detection accuracy, mitigating error propagation in SIC, and adapting to dynamic channel conditions in massive MIMO systems.

\(Q(s,a)\) is the state-action value function, \(\alpha\) is the learning rate, \(\gamma\) is the discount factor, \(s\) is the state (received signal and detected symbols), \(a\) is the action (symbol decision), and \(s{\prime}\) is the next state after taking action \(a\). The RL-SIC detector refines the detected symbols using the policy \(\pi *(x\mid y)\), improving upon the traditional SIC-based detection in massive MIMO. The final detected signal vector is

The proposed method enhances detection accuracy, mitigates error propagation in SIC, and adapts to nonlinear distortions in hardware-impaired systems. The 10% error channel estimation in Rayleigh fading affects SIC-RL detection by causing bias in signal reconstruction, resulting in compromised detection accuracy. The RL-based detector needs to learn from this flaw, develop robust procedures to reduce error propagation, guarantee enhanced symbol detection, and improve the performance in dynamic massive MIMO systems. Table 2 lists the pseudocode for the proposed method.

Simulation results

In this study, we used Matlab-2016 to estimate the performance of the proposed SIC-RL and conventional signal detectors with a Rayleigh channel. The parameters used in this study are listed in Table 3. The selected parameters ensure an accurate evaluation of the SIC-RL detection in Massive MIMO. Large \({N}_{t}\), \({N}_{r}\) models realistic MIMO scenarios, whereas 64, 256, and 512-QAM represent different modulation complexities. Rayleigh fading with 10% error adds real-world impairments. Q-learning with an adaptive \(\epsilon\)-greedy policy enhances decision-making. The BER PSD and complexity assess the detection performance under different noise conditions, ensuring a robust evaluation.

In Q-learning-based signal detection for SIC-RL in Massive-MIMO–NOMA systems, particularly under varying modulation schemes and diverse channel conditions, the exploration rate plays a crucial role in balancing the trade-off between exploring new actions and exploiting learned policies. Typically, the exploration rate, denoted as ε in the ε-greedy policy, starts at a relatively high value (\(\varepsilon =1\)), to encourage the agent to explore a wide range of possible detection actions. Over time, \(\varepsilon\) decayed gradually to a lower threshold ( \({\varepsilon }_{min}=0.01\)) to favor exploitation as the Q-values converged. Decay can follow a linear, exponential, or adaptive schedule. For instance, in exponential decay, the rate is updated using \({\varepsilon }_{t}= {\varepsilon }_{0}\times exp(-\lambda t)\), where \(\lambda\) is the decay rate and t is the episode count. This decay ensures that during the early learning phases, the RL agent experiences varied interference patterns, channel conditions, and modulation effects, thereby improving its generalization across environments. In SIC-RL, such decay allows the system to initially explore various signal ordering and decoding strategies under high-order modulations and then converge towards optimized detection strategies tailored to dynamic channel characteristics and modulation-aware interference patterns, ensuring both robustness and efficiency in signal reconstruction. The Fig. 2 illustrates the exponential decay of the exploration rate (\(\varepsilon\)) over 1000 episodes in a Q-learning-based SIC-RL system. Initially, ε was high, which encouraged the exploration of various detection strategies. As the training progresses, ε decreases gradually, favoring the exploitation of learned policies and ensuring stable and efficient signal detection under diverse conditions.

In SIC-RL for massive-MIMO–NOMA signal detection, the initial Q-table values are typically set to zero or small random values. This neutral initialization implies that the agent has no prior knowledge of the optimal detection policy, allowing a fair exploration of all possible actions (e.g., user decoding orders and modulation-specific strategies). Each Q-table entry corresponds to a state-action pair, where the state may represent features such as the estimated SINR, modulation type, and user index, while the action could be the selection of the next user to decode in the SIC process. The convergence criteria are based on the stabilization of the Q-values and consistent performance of the signal detection metrics (BER). Typically, convergence is assumed when.

-

a.

The change in Q values over successive episodes fell below a small threshold (\(\Delta Q < 0.001\)).

-

b.

The selected actions (detection sequences) stabilize across multiple episodes.

-

c.

Performance metrics like BER or throughput plateau, indicating policy maturity.

In addition, in dynamic channel or modulation environments, a windowed moving average of the performance is often used to confirm convergence under variable conditions. Early stopping or adaptive learning rates may be introduced to improve convergence in nonstationary environments. Table 4 lists the initialization and Final Q-table. In the Q-learning framework, Q (state, action) represents the expected reward for selecting an action in a given state. The reward function, represented by get Reward, is a placeholder in this example, but in a real system, it reflects the performance of signal detection, such as the Bit Error Rate (BER) or throughput, depending on the system’s objectives. The convergence of the Q-learning algorithm was monitored by tracking the maximum change in the Q-table across episodes. If the change between consecutive Q-table updates was below a specified threshold, the system was considered to have converged. Additionally, the epsilon parameter, which controls the exploration–exploitation trade-off, decays over time, gradually reducing exploration and shifting the focus towards exploiting the learned policies as the agent gains experience in the environment.

Figure 3 illustrates the BER vs. SNR graph, which compares different signal detection techniques in a Massive MIMO system using 512-QAM. The BER of 10–3 is attained at the SNR of 20 dB, 18.8 dB, 17.7 dB, 16 dB, 14.3 dB, 13.4 dB and 11.2 dB by the ZFE, CG, GS, AMP, MLD, MMSE and SIC-RL. The SIC-RL detector achieved the BER at the lowest SNR, outperforming all methods, followed by MMSE and MLD. AMP, GS, and CG showed moderate performance, whereas ZFE had the highest SNR owing to noise amplification. It is also noted that the proposed SIC-RL achieve a SNR gain of 8.8 dB, 7.6 dB, 6.4 dB, 4.8 dB, 3.1 dB and 2.2 dB as compared with the contemporary detectors. The graph highlights the effectiveness of SIC-RL in improving detection accuracy, especially at a low SNR. As the SNR increased, the BER decreased exponentially for all methods, demonstrating their reliability at higher signal quality, with SIC-RL providing the best error resilience.

The BER vs. SNR plot for 256-QAM modulation in a Massive MIMO system, comparing various detection methods, is presented in Fig. 4. The BER of 10–3 is achieved at the SNR of 18 dB by ZFE, 16.3 dB by CG, 14.5 dB by 13.1, 10.9 dB by MLD, 9.7 by MMSE and 6.6 dB by SIC-RL. The numerical results show that SIC-RL performs better than the traditional methods by achieving an SNR gain in the range 11.4 dB of 3.1 dB. The SIC-RL method performed the best, with the lowest SNR, followed by the MMSE and MLD. AMP, GS, and CG performed moderately well, whereas ZFE had the highest SNR because of noise amplification. With an increasing SNR, the BER decreases exponentially, which means that the detection accuracy is better. SIC-RL performs considerably better than all other approaches, particularly at a low SNR, and shows the strength of reducing errors. This indicates that SIC-RL is a highly efficient detection method for high-order QAM in Massive MIMO systems.

In Fig. 5, a graph of BER vs. SNR for 64-QAM is shown. With the SNR of 16 dB by ZFE, 14.3 dB by CG, 13.1 dB by GS, 11.7 dB by AMP, 10.2 dB by MLD, 8.3 dB by MMSE and 5 dB by SIC-RL respectively, the BER is 10^-3. It is observed that the SIC-RL considered in this paper got maximum detection as it has been able to attain SNR gain of 11 dB, 9.3 dB, 8.1 dB, 6.7 dB, 5.2 dB and 3.2 dB over the Conventional techniques. It is observed that signal detection requires less SNR than 256 and 512 QAM. The detection quality is improved over 256-QAM and 512-QAM with a lower modulation complexity and lower symbol density. 64-QAM has fewer symbol points, and thus a larger Euclidean distance between symbols; therefore, detection is less prone to noise and interference. This resulted in a reduced BER for the same SNR. In comparison, 256-QAM and 512-QAM contain denser constellations with greater vulnerability to interference and noise and require greater SNR for successful detection. The SIC-RL detector remains the best compared to the other methods with the least BER, followed by MMSE and MLD. The ZFE method exhibited the worst performance owing to the noise amplification. Generally, 64-QAM is more accurate in detection and has lower SNR requirements, which renders it a stronger candidate for actual wireless communication.

The analysis of 64-QAM BER performance under 5% channel error shows the robustness of every detector to inaccurate channel estimation. It reveals how sophisticated algorithms such as SIC-RL can keep the BER very low even with moderate channel errors, demonstrating their efficacy in real-world applications. This analysis is crucial for the design of efficient communication systems that can perform well even with estimation errors. Figure 6 illustrates the BER performance of various signal detectors for 64-QAM under 5% channel estimation error. At a BER of 10–3, the SNR values were approximately ZFE (13.8 dB), CG (12 dB), CS (10.2 dB), AMP (8.6 dB), MLD (7.7 dB), MMSE (6 dB), and SIC-RL (4.2 dB). The proposed SIC-RL detector outperformed the others significantly, achieving an SNR gain in the range of 1.8 dB 9.6 dB as compared with the conventional schemes. The results highlight that a significant improvement in performance is indicative of increased detection accuracy and noise robustness. Thus, SIC-RL is extremely well suited to high-data-rate and error-prone communication systems, particularly in situations where ideal channel knowledge is not practical.

The BER curves of 64-QAM with 10% channel error are shown in Fig. 7. The BER of 10–3 is achieved at the SNR of 17.4 dB, 16 dB, 14.4 dB, 13.2 dB, 11.8 dB 10 dB and 5.8 dB by the proposed SIC-RL and conventional schemes. The proposed SIC-RL significantly enhances the BER performance by achieving an SNR gain in the range of 4.2 dB 11.6 dB as compared with contemporary schemes. The BER vs. SNR performance of 64-QAM with 10% channel error, traditional detection algorithms (ZFE, CG, GS, AMP, MMSE, MLD) exhibit significant degradation in BER performance because of the effect of channel estimation errors. Traditional detection algorithms use precise channel state information (CSI) for equalization and detection; however, channel errors create mismatches, enhancing noise and interference. This leads to an elevated BER, particularly at lower SNR values. Conversely, the SIC-RL exhibited superior BER performance. The RL approach dynamically adjusts in accordance with channel variations and learns optimal detection techniques independently of channel shortcomings. It handles interference and noise effectively without heavy dependence on a given CSI, and is therefore resistant to channel errors. This flexibility enables the SIC-RL to perform better than traditional detectors with a significantly lower BER at all SNR values, particularly in adverse channel conditions.

The results in highlight the robustness of the proposed SIC-RL detector under 20% channel estimation error. It achieves a notable SNR gain of 14.5 dB to 2.6 dB over traditional detectors at a BER of 10–3, demonstrating superior noise resilience and enhanced reliability in highly impaired communication environments. Figure 8 presents the BER performance of various signal detectors for 64-QAM with 20% channel estimation error. At a BER of 10–3, the approximate SNR values are as follows: ZFE (22.3 dB); CG (19 dB) CS, (16.2 dB) AMP, (14.3 dB) MLD, (12 dB) MMSE, (10.4 dB); and SIC-RL (7.8 dB). The proposed SIC-RL detector shows a significant performance advantage, achieving a SNR gain in the range of 14.5 dB to 2.6 dB as compared with the contemporary algorithms, confirming its robustness in severely impaired channel conditions.

The Power Spectral Density (PSD) performance estimation of MIMO systems is an important analysis of spectral efficiency, interference cancellation, and signal integrity. PSD facilitates power distribution evaluation over frequencies to utilize the optimal bandwidth with minimal spectral leakage. PSD assists in comparing detection algorithms to determine their contributions to noise amplification and interference cancellation. Correct PSD estimation is important for adaptive modulation, beamforming, and interference cancellation in next-generation wireless communications to improve the overall system capacity, energy efficiency, and reliability of the communication. In Fig. 9, we compare the PSD performance of the 256X256 MIMO for 64-QAM under a Rayleigh channel for the signal detection schemes. PSD values of − 130, − 190, − 230, − 310, − 380, − 460 and − 530 were achieved using the ZFE, CG, CS, AMP, MLD, MMSE, and SIC-RL schemes. The proposed SIC-RL significantly improves the spectral access performance by minimizing the out-of-band emission (OBE) to − 530. It can be observed from the numerical values that the ZFE has greater PSD values, indicating more noise amplification. MMSE and MLD demonstrated better noise reduction. The SIC-RL had the lowest PSD value, indicating successful interference suppression. AMP, GS, and CG provide equal trade-offs. The comparison helps choose good detectors for resilient signal processing in next-generation wireless communication systems.

Figure 10 shows the PSD performance of the signal detectors for 64-QAM in Rician channel with 10% channel error. PSD values of − 52, − 110, − 157, − 210, − 290, − 340 and − 410 were achieved by the ZFE, CG, CS, AMP, MLD, MMSE, and SIC-RL schemes. The proposed SIC-RL outperformed contemporary detectors by achieving a PSD gain in the range of − 352 to − 70. The PSD performance comparison of different detectors for 64-QAM with 10% channel error demonstrated their insensitivity to channel distortions. The ZFE has the highest PSD, which reflects increased noise, and the SIC-RL has the lowest, reflecting better interference cancellation. MMSE and MLD offer improved noise suppression compared to AMP, GS, and CG, which have a trade-off between complexity and performance. The results show that sophisticated detection techniques improve spectral efficiency in the presence of channel imperfections.

Complexity

The complexity of signal detection in MIMO systems is essential for performance optimization, resource management, and real-time processing. With MIMO growing to Massive MIMO, detection complexity directly affects the processing time, power, and hardware feasibility. Optimal detection algorithms, such as MLD, are available but have exponential complexity, rendering them unsuitable for large systems. MMSE and ZFE are based on matrix inversion, resulting in cubic complexity \(O({N}_{t}^{3})\), which is computationally expensive for large numbers of antennas. Iterative techniques such as AMP, GS, and CG minimize the computational cost, but can suffer from convergence problems. SIC-RL adds learning-based detection, trade-off performance, and flexibility, but at the cost of heavy training25. By analyzing complexity, researchers can select effective detectors using system constraints, including latency, power consumption, and processing capability. Complexity analysis will aid in devising low-complexity high-performance detection methods for advanced radio system26. Table 5 presents a complexity analysis of the proposed and conventional detectors.

The complexity and antenna analyses are illustrated in Fig. 11. In Massive-MIMO–NOMA systems, the computational complexity of SIC-RL scales logarithmically with the number of antennas, denoted by \(O(log N\)). This reflects the efficient detection process in SIC combined with reinforcement learning, which scales more gracefully as the number of antennas increases. In contrast, Maximum Likelihood Detection (MLD) exhibits exponential complexity, \(O(2^{n} ),\) due to the exhaustive search required to evaluate all possible symbol combinations, making it computationally intensive as the number of antennas grows. The log–log plot visually demonstrates that while SIC-RL’s complexity increases slowly with the number of antennas, MLD’s complexity of the MLD grows exponentially, highlighting the scalability advantages of SIC-RL in large-scale Massive-MIMO–NOMA systems.

Conclusion

This study presents an in-depth evaluation of SIC-RL for massive MIMO signal detection across diverse modulation schemes and channel conditions. Comparative analysis with conventional detectors, including MMSE, MLD, AMP, GS, CG, and ZFE, demonstrated the superiority of SIC-RL in terms of BER, PSd), and computational complexity. Notably, at BER = 10⁻3, SIC-RL achieves substantial SNR gains of 11.2 dB for 512-QAM, 6.6 dB for 256-QAM, 5 dB for 64-QAM, and 5.8 dB for 64-QAM under 10% channel error, highlighting its robustness under challenging wireless environments. From a spectral efficiency perspective, SIC-RL reduces spectral leakage by 35% and 20% compared with traditional methods, making it an ideal choice for next-generation wireless networks requiring high data rates and minimal spectral contamination. Although ZFE and CG offer computational advantages, they suffer from poor BER performance owing to noise amplification. GS and AMP strike a balance between complexity and accuracy but still lag behind SIC-RL in terms of detection accuracy and adaptability to channel variations. Importantly, MLD provides optimal detection, but is computationally prohibitive for large-scale MIMO systems, whereas SIC-RL achieves near-logarithmic complexity growth, making it a feasible and scalable solution. One of the main limitations of the proposed method is that it relies on training data for convergence, resulting in performance loss in fast-changing channels and a higher computational cost for high-order modulation schemes. The key objective of this study is to establish a robust, adaptive, and computationally efficient signal detection strategy for large-scale MIMO–NOMA networks. Future research will focus on extending the SIC-RL framework to hybrid beamforming architectures and integrating it with intelligent reflecting surfaces (IRS) and reconfigurable intelligent surfaces (RIS) to further enhance detection under dynamic wireless environments. Moreover, efforts will be directed toward developing transfer-learning-based SIC-RL models that can be generalized across diverse channel distributions, reducing the training overhead. Another promising direction is to investigate the feasibility of hardware implementation using field-programmable gate arrays (FPGAs) or system-on-chip (SoC) platforms to validate latency and energy efficiency. Ultimately, the future aim is to build a unified SIC-RL framework that seamlessly adapts to real-world 6G communication scenarios, thereby enabling ultra-reliable, low-latency, and spectrum-efficient wireless communication.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Khwandah, S. A. et al. Massive MIMO systems for 5G communications. Wirel. Pers. Commun. 120, 2101–2115. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11277-021-08550-9 (2021).

Gao, D. et al. Signal detection in MIMO systems with hardware imperfections: Message passing on neural networks. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 23(1), 820–834. https://doi.org/10.1109/TWC.2023.3283275 (2024).

Albreem, M. A., Juntti, M. & Shahabuddin, S. Massive MIMO detection techniques: A survey. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 21(4), 3109–3132. https://doi.org/10.1109/COMST.2019.2935810 (2019).

Hassan, M. et al. Modeling of NOMA-MIMO-based power domain for 5G network under selective Rayleigh fading channels. Energies 15(15), 5668. https://doi.org/10.3390/en15155668 (2022).

Xie, J. Application study on the reinforcement learning strategies in the network awareness risk perception and prevention. Int. J. Comput. Intell. Syst. https://doi.org/10.1007/s44196-024-00492-x (2024).

Choi, J. & Nguyen, H. X. Low complexity SIC-based MIMO detection with list generation in the LR domain. In GLOBECOM 2009—2009 IEEE Global Telecommunications Conference, Honolulu, HI, USA, 2009, pp. 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1109/GLOCOM.2009.5425477.

Wang, Z., Xie, W., Zhou, Z., Meng, H. & Yang, M. Reinforcement learning-based MIMO radar multitarget detection assisted by Bayesian inference. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 60(4), 4463–4478. https://doi.org/10.1109/TAES.2024.3380581 (2024).

Kumar, A., Gaur, N. & Nanthaamornphong, A. A SIC and ML approach for MIMO non-orthogonal multiple access signal detection. Results Opt. 18, 100792 (2025).

Zhang, W., Feng, M., Krunz, M. & Hossein Yazdani Abyaneh, A. Signal detection and classification in shared spectrum: A deep learning approach. IEEE INFOCOM 2021—IEEE Conference on Computer Communications, Vancouver, BC, Canada (2021). https://doi.org/10.1109/INFOCOM42981.2021.9488834

Kumar, A., Gaur, N., Gupta, M. & Nanthaamornphong, A. Implementation of the deep learning method for signal detection in massive-MIMO-NOMA systems. Heliyon (2024). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e25374

Bui, T. T. T., Tran, X. N. & Phan, A. H. Deep learning based MIMO systems using open-loop autoencoder. AEU-Int. J. Electron. Commun. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aeue.2023.154712 (2023).

Liu, C., Chen, Y. & Yang, S. H. Signal detection with co-channel interference using deep learning. Phys. Commun. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phycom.2021.101343 (2021).

Lin, M., Zhang, X., Tian, Y. & Huang, Y. Multi-signal detection framework: A deep learning based carrier frequency and bandwidth estimation. Sensors https://doi.org/10.3390/s22103909 (2022).

Lacy, F., Reyes, A. R. & Brescia, A. Machine learning for low signal-to-noise ratio detection. Pattern Recognit. Lett. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.patrec.2024.02.008 (2024).

Gebeyehu, Z. M., Singh, R. S., Mishra, S. & Rathee, D. S. Efficient hybrid iterative method for signal detection in massive MIMO uplink system over AWGN channel. Hindawi J. Eng. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/3060464 (2022).

Kumar, A., Gaur, N. & Nanthaamornphong, A. A SIC and ML approach for MIMO non-orthogonal multiple access signal detection. Results Opt. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rio.2025.100792 (2025).

Yao, H. et al. Low complexity signal detection networks based on Gauss Seidel iterative method for massive MIMO systems. EURASIP J. Adv. Signal Process. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13634-022-00885-0 (2022).

Ratnam, D. V. & Rao, K. N. Bi-LSTM based deep learning method for 5G signal detection and channel estimation. AIMS Electron. Electr. Eng. https://doi.org/10.3934/electreng.2021017 (2021).

Albreem, M. A., Kumar, A., Alsharif, M. H., Khan, I. & Choi, B. J. Comparative analysis of data detection techniques for 5G massive MIMO systems. Sustainability https://doi.org/10.3390/su12219281 (2020).

Arévalo, L., de Lamare, R. C., Haardt, M. & Sampaio-Neto, R. Decoupled signal detection for the uplink of massive MIMO in 5G heterogeneous networks. EURASIP J. Wirel. Commun. Netw. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13638-017-0916-1 (2017).

Patel, S. et al. Impact of antenna spacing on differential spatial modulation and spatial modulation for 5G-based compact wireless devices. 2021 4th International Symposium on Advanced Electrical and Communication Technologies (ISAECT), Alkhobar, Saudi Arabia, 2021, pp. 01–06. https://doi.org/10.1109/ISAECT53699.2021.9668400.

Yang, J., Chen, Y., Gao, X., Slock, D. T. M. & Xia, X.-G. Signal detection for ultra-massive MIMO: An information geometry approach. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 72, 824–838. https://doi.org/10.1109/TSP.2024.3358617 (2024).

Cheng, Q., Shi, Z., Yuan, J. & Lin, H. MIMO-ODDM signal detection: A spatial-based generative adversarial network approach. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 23(9), 12499–12512. https://doi.org/10.1109/TWC.2024.3392881 (2024).

Ismail, H. et al. RL-ECGNet: reSource-aware multi-class detection of arrhythmia through reinforcement learning. Appl. Intell. 53, 30927–30939. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10489-023-05147-6 (2023).

Chinnusami, M. et al. Low complexity signal detection for massive MIMO in B5G uplink system. IEEE Access 11, 91051–91059. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2023.3266476 (2023).

Liu, X., Zhang, Z., Wang, X., Lian, J. & Dai, X. A low complexity high performance weighted Neumann series-based massive MIMO detection. Proceedings of 28th Wireless Optical Communication Conference (WOCC), pp. 1–5 (2019).

Acknowledgements

The authors extend their appreciation to Taif University, Saudi Arabia, for supporting this work through project number (TU-DSPP-2024-04).

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This research was funded by Taif University, Saudi Arabia, project number (TU-DSPP-2024-04).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.K, A.Z, M.Ah and M.M all have equally contributed in the article.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kumar, A., Nanthaamornphong, A., Alsharif, M.H. et al. SIC based RL for massive MIMO NOMA signal detection for different modulation schemes under diverse channel conditions. Sci Rep 15, 24641 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-06492-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-06492-x

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Optimizing FBS 3D positions for sum rate maximization in downlink NOMA 6G network

Scientific Reports (2025)