Abstract

Cardiovascular failure has been recognized as the predominant cause of perioperative mortality in small animals, particularly dogs. This study was designed to evaluate the effectiveness of adding intravenous atracurium to a ketofol infusion during anesthesia in dogs. Thirty male mongrel dogs were premedicated with an intramuscular injection containing 0.02 mg/kg of acepromazine and 0.2 mg/kg of methadone. Thirty minutes later, the dogs were equally and randomly divided into two groups (n = 15): the Ketofol Group (KFG), in which anesthesia was induced using IV administration of 0.5 ml/kg of ketofol, and the atracurium/ketofol Group (AKFG), in which anesthesia was induced using IV administration of 0.25 mg/kg of atracurium with 0.5 ml/kg of ketofol. Following intubation, anesthesia was maintained by a variable intravenous infusion at 0.2 ml/kg/min in KFG or a combination of 0.01 mg/kg/min atracurium and 0.2 ml/kg/min ketofol in AKFG. Respiratory frequency (fR), mean arterial pressure (MAP), heart rate (HR), oxygen saturation of hemoglobin (SpO2), end-tidal carbon dioxide concentration (EtCO2), rectal temperature (RT), the quality of induction, intubation, recovery period, ejection fraction percentage (EF%), fractional shortening percentage (FS%), and stroke volume (SV) were recorded. The ketofol doses were significantly lower, P ≤ 0.01, in the AKFG group (4.2 ± 0.44 mg/kg) than in the KFG group (2.27 ± 0.6 mg/kg). There were statistically significant increases in RR, HR, MAP, EtCO2, and echocardiography parameters in the AKFG group compared to the KFG group. Additionally, the AKFG group exhibited a significant reduction in induction, intubation, and recovery scores compared to the KFG group. Adding atracurium to ketofol during dog anesthesia positively impacts the hemodynamic and cardiac parameters and improves the quality of induction, intubation, and recovery.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cardiovascular failure is the most frequently reported cause of perioperative death in dogs1. The mortality rate ranges from 30 to 70% and is primarily attributed to anesthetic overdose, myocardial depression, cardiac arrhythmias, circulatory failure, and hypovolemia2,3,4,5,6. In veterinary cardiology, the echocardiogram has recently become a crucial adjunctive examination7,8,9,10. With its non-invasive nature, wide accessibility, and ability to provide real-time imaging, this tool is essential for identifying anatomical structures, assessing the size and function of the heart and large vessels, evaluating hemodynamics, and detecting both congenital and acquired heart diseases11,12. M‐mode echocardiography determines standard reference values for dogs13 and other animals14,15,16,17,18.

Propofol, an alkyl phenol compound, exhibits a rapid onset and brief duration of action, rendering it primarily suitable for use as an induction agent19,20. However, its use as the sole anesthetic agent for prolonged surgical procedures is limited due to its dose-dependent respiratory depression and hypotension19,20. Another common anesthetic drug used in dogs is ketamine, a dissociative agent with a rapid onset of action and mild to moderate respiratory and cardiovascular effects5,6. It causes mild to moderate transient impacts on blood pressure, cardiac output, and heart rate, leading to convulsions, muscle stiffness, and ultimately to eventful recoveries6. The overall cardiovascular effects of propofol and the potential benefits of combining co-induction agents in dogs are still a subject of debate21,22,23.

Ketofol, which is a combination of propofol and ketamine, is extensively utilized for short procedural sedation and analgesia, so that it is used to achieve the hemodynamic stability observed when these drugs are separately administered while providing the convenience of a single infusion20,24,25. Ketofol (1:1) is frequently administered as a variable intravenous infusion to provide sedation and analgesia for both humans and animals4,26,27,28. Combining ketamine with muscle relaxants and tranquilizers can prolong the anesthetic effect, prevent seizures, and achieve analgesia and muscle relaxation29.

Neuromuscular blocking agents (NMBA) are commonly used in human or veterinary surgeries as neuromuscular block (NMB) allows easier surgical access to the abdominal cavity as well as organ manipulation30. The depth of NMB refers to the muscular response following stimulation of a motor nerve, typically the ulnar nerve. The contraction of the limb muscle is quantified by the train-of-four method (TOF) after TOF stimulation31.

In contrast, neuromuscular blockers (NMBs) do not induce central nervous system depression. Therefore, they are primarily administered along with anesthetics and analgesics during surgery. NMBs are affected by anesthetics, and their most prominent augmentation is observed when used in combination with hypnotic drugs such as propofol32,33. In dogs, the administration of low doses of atracurium (25, 50, or 75 μg/kg) results in muscle relaxation such as oculomotor, tail, and limbs without complete blocking the intercostal and diaphragmatic muscles in dogs. Hence, the severity of atracurium side effects is contingent upon the dosage and administration technique34,35.

To date, no previous studies have evaluated the equality of anesthesia, including induction, intubation, and recovery during a variable rate infusion (CRI) of atracurium/ketofol in healthy dogs. Therefore, this study was conducted to assess the impact of ketofol infusion anesthesia alone or in combination with atracurium on anesthesia quality during induction, intubation, and recovery. Besides, this study aimed to examine any changes in hemodynamic and echocardiographic parameters in dogs. We hypothesized that adding atracurium to ketofol would result in greater stability in cardiovascular parameters than ketofol alone in dogs.

Materials and methods

Animal ethics and consent

This study is in accordance with ARRIVE guidelines. All experiments conducted in this study were in strict accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. This study had an approval number from the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine- Mansoura University Animal Care and Use Committee, Egypt, with the registration code R/146, and informed owner consent was obtained.

Animals

Based on sample size calculations with an alpha error of 0.05, a beta error of 0.90, an effect size of 0.5, and a critical F of 4.196, this prospective study indicated that the total sample size was 30 dogs. Thus, each group consisted of 15 dogs.

Thirty male mixed-breed dogs were admitted to Mansoura University Veterinary Hospital. The dogs were brought from a shelter situated in Mansoura under the supervision of the Mansoura University Animal Care and Use Committee.

The dogs’ ages were 25 ± 3 months, and their weight was 24 ± 2.36 kg. All dogs were deemed healthy following a clinical examination classified as ASA I. The dogs were owned by a private shelter specifically designed and constructed to accommodate abandoned and stray dogs. The dogs were relocated to the Hospital of Veterinary Medicine and housed individually in cages with dimensions of 1 × 1.5 × 1.2 m. The dogs were kept in these cages until one day after the completion of the experiments. The dogs were confined indoors all day without any opportunity for outdoor physical activity, but they were allowed to be free from their cages for approximately 15–20 min during feeding time. The animals’ health status was assessed through a comprehensive physical, biochemical (urea, creatinine, glucose, albumin, alanine aminotransferase, Na+, Ca++, K+, and Mg++), and hematological examination. The exclusion criteria encompass evident inflammatory conditions, aggressive behavior, any hematologic crises in the complete blood count (CBC), and abnormal biochemical analysis results.

Anaesthetic protocols

The anaesthesia drugs and infusion pumps used in this study were prepared before the study. All syringes were labeled with numbers by (RF). The anaesthesia protocol was conducted by a blind, experienced veterinarian (MA). The animals were fasted for a minimum of 6 h, with free access to water until pre-medication was administered. All dogs in this study were premedicated with 0.02 mg/kg of acepromazine maleate (Prequillan, 10 mg/ml, Fatro, Switzerland) and 0.2 mg/kg of methadone HCL (methadone 1%, Bioniche Pharma, USA) intramuscularly in the thigh muscles. After thirty minutes, a 20-gauge intravenous cannula (Mdk Mart, Egypt) was inserted into a cephalic vein. For non-invasive oscillometric blood pressure monitoring, a suitable blood pressure cuff (Critikon Soft-cuff, GE Healthcare, UK), with a cuff width/metatarsal circumference ratio of 0.3, was placed over the dorsomedial artery (M69S user’s manual, China).

The study design was investigated in a prospective, randomized, blind controlled trial, in which the premedicated dogs were assigned to two groups (n = 15) to receive an intravenous induction mixture. The first group (KFG) received 0.5 mL/kg of ketofol (1:1), a combination of 100 mg of propofol (Diprivan 10 mg/ml, AstraZeneca, Egypt), and 100 mg of ketamine (Ketamine 100 mg/ml; Alfasan, Holland) (i.e.: each 10 ml of propofol1% added to 1 ml of ketamine10%; 0.5 ml of ketofol contains about 4.17 mg ketamine and 4.17 mg propofol). This admixture of ketofol was kept for a maximum of 12 h28. The second group (AKFG) IV received 0.25 mg/kg of atracurium (atracurium besylate, 10 mg/ml, Hameln, Germany) combined with 0.5 mL/kg of ketofol (both drugs were prepared in one syringe).

The quality of induction in dogs was evaluated36 (Table 1). The dogs that showed a rough (marked excitement, muscle twitching, paddling of limbs, head movement, or severe excitement with vocalization, ie, scoring 2 or 3) were excluded from this study. Two dogs in the KFG had a rough induction score of 3, and one in the AKFG had a rough induction score of 2. The endotracheal tube was connected to a rebreathing circle system, and the oxygen had adjustable flow rates from 3 L/minute.

Anesthesia was maintained immediately 10 min after induction throughout the study using a variable rate infusion system (VRI; Mindray SK-500II, China). The first group (KFG) received ketofol at a 0.2 mL/kg/minute dose. The second group (AKFG) received a combination of atracurium at a dose of 0.01 mg/kg/minute and ketofol at a dose of 0.2 mL/kg/minute (i.e., 3.3 mg/kg propofol and 3.3 mg/kg ketamine). The dogs in both groups (KFG or AKFG) were administered incremental doses of ketofol at 0.2 mL/kg only in case of withdrawal or twitching of the non-stimulated right limbs, head movement, chewing, licking, blinking, or swallowing occurred.

Both groups of dogs received lactated Ringer’s solution at a rate of 5 mL/kg/h IV. The variable rate infusion of ketofol, atracurium, and IV fluid therapy was disconnected after 50 min. Afterward, the dogs were allowed to recover and were extubated once they were able to swallow.

Data collection and evaluation times

An observer who was blinded to the treatment groups assessed the quality (score) and time per minute of sedation, induction, intubation, and recovery36,37,38,39 (Table 1). Induction time was recorded as the time from the administration of ketofol or atracurium/ketofol (time 0 of anesthesia) until the dogs achieved recumbency. Intubation time was recorded as the time required to insert an endotracheal tube. Recovery time was recorded as the time from the stopped administration of VRI ketofol or atracurium/ketofol till the dogs stood.

The time (per second) to first breath after induction of anesthesia with ketofol or atracurium/ketofol and the total doses (ml) of ketofol used during the maintenance of anesthesia were recorded and analyzed.

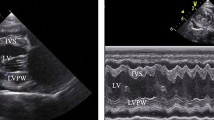

Furthermore, the following parameters were assessed: the mean arterial blood pressure (MAP), heart rate (HR), respiratory frequency (fR), oxygen saturation of hemoglobin (SpO2), end-tidal carbon dioxide concentration (EtCO2), and rectal temperature (RT) were measured at previous time points using a multi-parameter monitor (Aisys Carestation, General Electric Co; Datex-Ohmeda, GE Healthcare Inc., Madison, WI, USA). Additionally, the echocardiographic examination was conducted using portable ultrasonographic equipment (Esaote MylabTM 30 Vet Gold, Brazil) with a sectoral transducer (PA240) at a frequency range of 1 to 4 MHz. These parameters were assessed at different time points: before the administration of pre-anesthetic medications considered as a baseline (M0); 30 min after the administration of pre-anesthetic medications (M1); immediately after intubation (M2); and at 10, 20, 30, 40, and 50 min after maintaining anesthesia (T10, T20, T30, T40, and T50).

The dogs were placed in right lateral recumbent positions, and echocardiographic measurements followed the guidelines outlined in the literature40,41,42,43,44,45. In the right parasternal window, on the transverse axis, the following parameters were evaluated using M mode: diastolic and systolic interventricular septum thickness (IVSd and IVSs cm), diastolic and systolic left ventricular internal diameter (LVIDd and LVIDs cm), left ventricular posterior wall thickness at end-diastole and end-systole (LVPWd and LVPWs cm), interventricular septal thickness at end-diastole and end-systole (IVSTd and IVSTs cm), left ventricular volume at end-diastole and end-systole (EDV and ESV ml). The stroke volume (SV ml), fractional shortening percentage (FS%), ejection fraction percentage (EF%), and the left atrial/aortic diameter ratio (La/Ao ratio) were calculated from the measurements performed in M mode.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using Minitab 16 Statistical Software (Minitab Ltd., UK). Deviations from assumptions of normality were assessed using graphical displays and the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Demographic data, induction, intubation, recovery score, and ketofol doses were compared using the Mann–Whitney U-test. The data were presented as median (range). Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05. The unpaired Student’s t-test was used to compare the average HR, fR, MAP, RT, SpO2, ETCO2, and echocardiographic parameters at different time points between the groups.

Repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used, followed by the Bonferroni test, to compare means within each group at time zero. To compare between groups at each time, one-way ANOVA was performed. The level of significance was set at P ≤ 0.05. The normally distributed data were presented as mean ± standard deviation, while non-normally distributed data were presented as median (range).

Results

There were no significant differences between animals at the baseline (M0), and all animals were classified as ASA I. The sedation score following the administration of acepromazine and methadone in both groups was 2 (1–2), with no significant differences (P = 0.825). In addition, there was no difference between the groups following pre-anesthetic administration of acepromazine/methadone. None of the animals in either group received additional doses of sedation agents.

The induction time in the AKFG was significantly faster in comparison to the KFG (2.49 ± 0.31 min vs. 6.28 ± 0.27 min; P < 0.04). The intubation time did not show significant differences among the animals (the KFG was 4 ± 2 min vs. the AKFG was 5 ± 1 min; P = 0.782). Conversely, the recovery time was considerably longer in the KFG than in the AKFG (9.49 ± 0.3 vs. 5.49 ± 1.23 min; P = 0.011).

The total VRI dose of ketofol used for maintaining anesthesia in the KFG group was 4.2 ± 0.44 ml/kg, significantly higher than the dose used in the AKFG group (2.27 ± 0.6 ml/kg; P ≤ 0.05).

Furthermore, the induction, intubation, and recovery scores in the AKFG substantially increased and considerably improved compared to the KFG (0 (0–1), 1(0–1), and 1 (0–2) vs. 1(0–1), 2(1–2) and 2 (2–3); P = 0.04; Fig. 1). Overall, induction, intubation, and recovery were smooth in all dogs in AKFG. In contrast, the five dogs in the KFG group experienced muscle twitching during the induction period and were given additional induction doses of ketofol 0.5 ml/kg.

Following sedation (M1), all recording parameters significantly reduced compared to baseline (M0) without difference between groups. The rectal temperature in all animals remained between 37.2 and 37.9 °C without a significant difference at any time point.

The heart rate was significantly higher in the AKFG (120 ± 10 bpm) than in the KFG (96 ± 9.1 bpm; P = 0.02) post-induction and intubation (M2) and till the end of the anesthesia (T50) in (Fig. 2A).

Time to the first spontaneous breath after induction of anesthesia with ketofol or atracurium/ketofol was substantially different between the KFG (6 ± 3 s) vs. the AKFG (2 ± 2 s; P = 0.043) post-induction. The KFG group experienced a more significant reduction in respiratory rate (fR) compared to the AKFG group (12 ± 1.23 bpm vs. 17 ± 2.54; P = 0.025) at M2 till T50 (Fig. 2B). Oxygen saturation of hemoglobin (SpO2) was significantly higher in the KFG group than in the AKFG group (98.47 ± 0.52 vs. 95.33 ± 0.61%; P = 0.036). Unlike End-tidal carbon dioxide level (EtCO2) significantly increased in the KFG group than the AKFG group at M2 (38.33 ± 1.21 vs. 39.47 ± 1.32 mmHg; P = 0.016) till T50 (Fig. 2C). Immediately after intubation (M2), the MAP was significantly higher in the AKFG compared to the KFG (89 ± 8 vs. 69 ± 5 mmHg; P = 0.033) and throughout the anaesthetic period T50 in (Fig. 2D).

The effects of acepromazine/methadone, ketofol, and atracurium/ketofol during the experimental period on the echocardiographic parameters between the groups and within the same group are presented (Table 2). Echocardiography findings of SV, EF%, and FS% were significantly affected by the time for ketofol (P = 0.012) and atracurium/ketofol (P = 0.031) compared with the post-sedation period M1. However, the AKFG recorded significantly higher values (P ≤ 0.05) of SV, EF%, and FS% at M2 compared with the KFG during the maintenance period of anesthesia.

At M1, the La/Ao ratio in both groups exhibited a significantly reduced value (P = 0.01), which subsequently increased following induction and throughout anesthesia. Nevertheless, the AKFG values substantially increased compared to the KFG values (P ≤ 0.05; Fig. 3).

The stroke volume (SV), ejection fraction (EF%), and fractional shortening (FS%) were significantly affected by time (P < 0.002). From M2 to T50, treatment with AKFG resulted in significantly higher values of SV ml (Fig. 4A), EF% (Fig. 4B), and FS% (Fig. 4C) compared to KFG.

In addition, the left atrial/aortic diameter ratio (La/Ao) showed a significant increase over time (P = 0.03) in both groups (Fig. 5). The AKFG group exhibited a significant increase in La/Ao (P = 0.01) at M2, T10, T20, T30, T40, and T50 compared to the KFG group (Fig. 6).

Discussion

Previous studies have examined the use of ketamine in combination with propofol to attenuate the dose-dependent adverse events of propofol, including respiratory depression and hypotension4,28,46,47. Moreover, while the CV effects of ketofol treatment were satisfactory, respiratory adverse events did not decrease and tended to worsen as the ketamine ratio increased. In contrast, some studies have emphasized that ketofol, with a lower proportion of ketamine compared to propofol, may serve as a viable alternative to propofol alone, particularly in cases where there is a higher risk of respiratory depression48,49. No cardiovascular effects, such as impaired cardiac function or myocardial injury, were detected in healthy dogs when ketamine was administered at doses of 0.02 and 0.04 mcg/kg/minute for an extended time. In addition, the lower dosage that was examined exhibited enhanced stability in cardiac function, as evidenced by fewer changes in variables such as CI, MAP, HR, and EF compared to the baseline values43. Conversely, bolus doses of ketamine have a more significant effect on the CVS, leading to unfavorable conditions like hypertension and tachycardia50. The present research was designed to study the impact of ketofol 1:1 when added to atracurium on the heart rate, mean blood pressure, respiratory rate, SpO2, ETCO2, stroke volume, ejection fraction, and fractional shortening.

The findings of our study indicated that the administration of a VRI of 0.01 mg/kg/h of atracurium combined with 0.2 ml/kg/h of ketofol resulted in significantly higher HR, fR, and MAP compared to the administration of 0.2 ml/kg/h of ketofol alone. This finding aligns with a previous study28 that noted differences in delivery speed, and the possibility of dogs having a particular vulnerability to ketamine, should not be ignored.

The current study only evaluated respiratory effects by measuring fR, ETCO2, and SpO2, which coincides with28. However, additional information, such as blood gases and minute volume, would have been beneficial in evaluating respiratory function. Hypercapnia recorded in AKFG may be the cause of higher HR, RR, as an increase in carbon dioxide levels stimulates the sympathetic system, leading to tachycardia and tachypnea51.

In the current study, two dogs in the KFG had a rough induction score of 3, and one in the AKFG had a rough induction score of 2, were excluded to avoid an additional bolus and the effect of induction drugs (ketofol and atracurium).

AKFG demonstrated enhanced efficacy in tracheal intubation and anesthesia induction compared to KFG alone. These results are consistent with a study conducted52 that found that NMBs improved tracheal intubation.

However, Lerche et al. mentioned that53 the administration of rapid bolus ketamine with midazolam can lead to a transient decrease in ventilation in dogs. In our study, the KFG resulted in a more significant decrease in the rate of respiration than the AKFG. This result is inconsistent with a previous study54 indicating that the addition of ketamine to propofol did not exacerbate apnea when compared to propofol alone. In contrast to a study conducted in cats55, ketofol has been shown to cause no or minimal respiratory depression when baseline values were compared to post-induction measurements. The variation in the use of anesthetic agents was elucidated by56 those who mentioned that various factors determine the use of anesthetic agents. These factors include the surgical operation settings, the patient’s response to the anesthetic drug action, the animal species or breed, and the operated animal’s health status.

Ketamine can be used as a standalone anesthetic agent; however, it causes muscle rigidity, catalepsy, tachycardia, poor muscle relaxation, and hypertension. Therefore, the utilization of ketamine as a solitary anesthetic medication has been restricted to cases involving myoclonus and muscle hypertonicity, infrequent convulsions, and violent recovery. In addition, ketamine must be integrated with other sedatives, such as acepromazine and midazolam, to decrease adverse impacts57,58,59 such as muscle relaxation.

The current study found that the combination of acepromazine and methadone resulted in a level of sedation ranging from mild to moderate. This sedation was effective in allowing the placement of a catheter and facilitating the induction of anesthesia, eliminating the requirement for supplementary sedation. Consequently, there was a decrease in the negative impact on the cardiorespiratory function60,61,62. Acepromazine’s fundamental mechanism does not involve any analgesic effect, but it does have a prolonged duration of action. In addition, it is associated with hypotension due to notable peripheral vasodilatation and variability in its response in dogs63.

Sedation may be necessary when animals experience stress and echocardiographic examination becomes challenging64. Another study found that using a combination of acepromazine and hydromorphone for sedation does not impact M-mode and two-dimensional (2D) measurements despite the mild increase in HR13,65.

Specific drugs, such as ketamine and xylazine, can significantly decrease many echocardiographic variables, including the left ventricular lumen diameter in the diastolic phase, the fractional shortening, and the left atrium diameter (LA)14. Prior research revealed that propofol caused a mild decrease in systolic mitral annular velocity, but it did not affect diastolic function in Maine coon cats with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM)66. Nevertheless, the potential adverse cardiac effects of ketofol have not been fully elucidated. Furthermore, ketofol has been reported to provide smooth recoveries in other species, as revealed by46,55.

Atracurium is reported to decrease blood pressure due to histamine or prostacyclin release occasionally20. Other studies in dogs have not shown significant changes in cardiovascular parameters, blood pressure, and heart rate associated with administering atracurium followed by propofol induction67,68. Considering that TIVA needs a higher dose of NMBs than inhalation anesthesia69, using NMBs reduces spasmodic breaths during mechanical ventilation of the lungs and the plasma clearance process70. These advantages may cause hemodynamic stability and improve induction, intubation, and recovery scores registered in the AKFG32,33.

Contrary to specific induction anesthetics like alfaxalone, which have a more significant impact on body temperature, especially in the early stages of sedation42. The findings indicated a marginal and statistically insignificant decline in body temperature (approximately 1 °C) in both groups, a common occurrence during anesthesia.

Researchers have focused on standardizing M-mode echocardiography values according to the breed type. Multiple studies presented proposed values. Kawahara et al.71 found that the cardiac functional parameters, including EF%, CI, FS%, and SV, are commonly used to examine animal cardiac and hemodynamic function profiles. Anesthetic drugs have a direct and indirect effect on hemodynamics and cardiac performance, making them significant factors to consider in interpreting changes in these parameters under different pathophysiological and physiological circumstances45,71,72.

The decrease in HR improved the alignment of the M-mode echocardiographic measurements. Additionally, the decreased voluntary movements of the animals, due to the reassurance during sedation, aided the examination process73.

Consistent with38, left ventricular end-diastolic diameter (LVDd) and left ventricular end-systolic diameter (LVDs), as well as the other parameters, were significantly decreased after sedation with acepromazine/methadone compared to the baseline values. The decrease in LVDd and LVDs can be attributed to the hypotensive effects induced by the combination of acepromazine and methadone. Moreover, this reduction in diameter is sufficient to result in a decrease in the left ventricular volume and aortic diameters. When comparing the KFG to those in the baseline measurements, statistically significantly lower EF% and FS% were reported. The hypotensive effects of acepromazine, methadone, and propofol administration may be the cause. In the case of reduced blood flow to the heart, the passive pathway of blood from the left atrium to the left ventricle remains relatively constant, which may result in a smaller blood volume available for the active pathway. Therefore, it may lead to an increase in these parameters41.

The cardiac parameters, such as FS%, EF%, and SV, exhibited significant changes until the end of the anaesthetic period (P ≤ 0.05) in dogs that received the AKFG compared to the KFG. The most significant difference between the M1 and T10 was observed when atracurium and ketamine were administered via bolus injection. Interestingly, the wall thickness did not rapidly increase, suggesting that ventricular myocardial fibers in postnatal dogs tend to elongate more than they widen. Another possibility is that myocardial density increases with age while extracellular water concentration decreases. In addition, age had a significant impact on the mean values of left ventricular posterior wall thickness (LVPWs) and interventricular septal thickness at end-diastole (IVSd)74.

The La/Ao ratio depends on two variables: the diameter of the left atrium divided by the diameter of the aortic annulus11. In the present study, there was a significant reduction in the La/Ao ratio post-sedation with acepromazine/methadone, resulting from blood reduction. Subsequently, there was a rapid rise in the ratio after the administration of ketamine in the induction protocol, observed in both groups. However, the increase in the cardiac index was particularly pronounced in the AKFG due to the positive inotropic effect of the NMBs75 and the use of low doses of atracurium.

One limitation of the current study was the absence of controlled ventilation and monitoring with Train of Four. Further study should be made to evaluate the impact of this protocol when mechanical ventilation is used.

Conclusion

It was noted that adding atracurium to Ketofol resulted in reduced duration of apnea after induction, as well as improved the quality of induction, intubation, and recovery periods. It had minimal effects on heart rate, respiratory rate, and blood pressure levels. Additionally, it can conserve echocardiographic parameters and cardiac hemodynamics. Consequently, it could be considered an alternative to ketofol for the induction and maintenance of anesthesia in healthy dogs.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- IVSd:

-

Interventricular septum thickness at diastole

- IVSs:

-

Interventricular septum thickness at systole

- LVIDd:

-

Left ventricular internal diameter at diastole

- LVIDs:

-

Left ventricular internal diameter at systole

- LVPWd:

-

Left ventricular posterior wall thickness at end-diastole

- LVPWs:

-

Left ventricular posterior wall thickness at end-systole

- IVSTd:

-

Interventricular septal thickness at end-diastole

- IVSTs:

-

Interventricular septal thickness at end-systole

- EDV:

-

Left ventricular volume at end-diastole

- ESV:

-

Left ventricular volume at end-systole.

- SV:

-

Stroke volume.

- FS%:

-

Fractional shortening percentage.

- EF%:

-

Ejection fraction percentage.

- La/Ao:

-

Left atrial/aortic diameter ratio

References

Shoop-Worrall, S. J., O’neill, D. G., Viscasillas, J. & Brodbelt, D. C. Mortality related to general anaesthesia and sedation in dogs under UK primary veterinary care. Vet. Anaesth. Analg. 49, 433–442 (2022).

Giselle Hosgood, B. V. S. C. Evalution of age as a risk factor for perianesthetic morbidity and mortality in the dog. J. Vet. Emerg. Crit. Care 8, 222–236 (1998).

Dyson, D., Maxie, M. G. & Schnurr, D. Morbidity and mortality associated with anesthetic management in small animal veterinary practice in Ontario. J. Am. Anim. Hosp. Assoc. 34, 325–335 (1998).

Wamaitha, M. N., Mogoa, E. M. & Mande, J. D. Evaluation of anesthesia produced by ketofol in acepromazine-or medetomidine-sedated dogs. J. Adv. Vet. Anim. Res. 6, 215 (2019).

Tranquilli, W. J., Thurmon, J. C. & Grimm, K. A. Lumb and Jones’ veterinary anesthesia and analgesia (John Wiley & Sons, 2013).

Nicholson, A. & Watson, A. Survey on small animal anaesthesia. Aust. Vet. J. 79, 613–619 (2001).

Torre, P. D., Kirby, A., Church, D. & Malik, R. Echocardiographic measurements in Greyhounds, Whippets and Italian Greyhounds-dogs with a similar conformation but different size. Aust. Vet. J. 78, 49–55 (2000).

Chetboul, V. & Tissier, R. Echocardiographic assessment of canine degenerative mitral valve disease. J. Vet. Cardiol. 14, 127–148 (2012).

Singh, P., Singh, N., Mahajan, S. & Singh, T. Echocardiography as an approach for canine cardiac disease diagnosis. Vet. World 7, (2014).

Tsai, C.-H., Huang, C.-C., Ho, C.-C. & Claretti, M. Echocardiographic parameters and indices in 23 healthy Maltese dogs. J. Vet. Sci. 22, e60 (2021).

Ram, R., Mickelsen, D. M., Theodoropoulos, C. & Blaxall, B. C. New approaches in small animal echocardiography: Imaging the sounds of silence. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 301, H1765–H1780 (2011).

De Madron, E., Chetboul, V. & Bussadori, C. Clinical echocardiography of the dog and cat. (Elsevier Health Sciences, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015).

Wess, G., Bauer, A. & Kopp, A. Echocardiographic reference intervals for volumetric measurements of the left ventricle using the Simpson’s method of discs in 1331 dogs. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 35, 724–738 (2021).

Zucca, E. et al. Echocardiographic measurements of cardiac dimensions in normal Standardbred racehorses. J. Vet. Cardiol. 10, 45–51 (2008).

Silva, A., Muzzi, R., Oberlender, G., Nogueira, R. & Muzzi, L. Feline hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: An echocardiographic approach. Arch. Med. Vet. 45, 1–6 (2013).

Mandour, A. S. et al. Assessment of the cardiac functions using full conventional echocardiography with tissue Doppler imaging before and after Xylazine sedation in male shiba goats. Animals 10, 2320 (2020).

Esmailinejad, M. R., Masoudifard, M., Azari, O., Sakhaee, E. & Ghalekhani, N. Echocardiographic assessment of intravenous administration of medetomidine and xylazine hydrochloride at different sedative doses in one-humped camel calves (Camelus dromedarious). In vol. 13 39 (Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Urmia University, Urmia, Iran, 2022).

Marzok, M. et al. Evaluation of cardiac indices using M-mode echocardiography after administration of metoclopramide and ondansetron in donkeys (Equus asinus): An experimental study. Front. Vet. Sci. 10, 1189710 (2023).

Kam, P. & Cardone, D. Propofol infusion syndrome. Anaesthesia 62, 690–701 (2007).

Dugdale, A. H., Beaumont, G., Bradbrook, C. & Gurney, M. Veterinary anaesthesia: Principles to practice (John Wiley & Sons, 2020).

Anderson, L. & Robb, H. A comparison of midazolam co-induction with propofol predosing for induction of anaesthesia. Anaesthesia 53, 1117–1120 (1998).

Goel, S., Bhardwaj, N. & Jain, K. Efficacy of ketamine and midazolam as co-induction agents with propofol for laryngeal mask insertion in children. Pediatr. Anesth. 18, 628–634 (2008).

Hopkins, A., Giuffrida, M. & Larenza, M. P. Midazolam, as a co-induction agent, has propofol sparing effects but also decreases systolic blood pressure in healthy dogs. Vet. Anaesth. Analg. 41, 64–72 (2014).

Lumb, W. V. & Jones, E. W. Veterinary anesthesia (Lea & Febiger, 1984).

Brodbelt, D. C. The confidential enquiry into perioperative small animal fatalities. (2006).

Phillips, W., Anderson, A., Rosengreen, M., Johnson, J. & Halpin, J. Propofol versus propofol/ketamine for brief painful procedures in the emergency department: Clinical and bispectral index scale comparison. J. Pain Palliat. Care Pharmacother. 24, 349–355 (2010).

Amornyotin, S. Ketofol: A combination of ketamine and propofol. J. Anesth. Crit. Care Open Access 1, 00031 (2014).

Martinez-Taboada, F. & Leece, E. A. Comparison of propofol with ketofol, a propofol-ketamine admixture, for induction of anaesthesia in healthy dogs. Vet. Anaesth. Analg. 41, 575–582 (2014).

Sager, J. K. & Norkus, C. L. Emergency and critical care anesthesia. Vet. Tech. Man. Small Anim. Emerg. Crit. Care 439–477 (2018) https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119536598.ch22.

Rauser, P., Crha, M., Sivkova, A., Zapletalova, J. & Korytarova, N. Influence of atracurium on selected cardiovascular and respiratory variables and surgical times in dogs undergoing laparoscopic ovariectomy with a standardised ventilation pattern. Veterinární Medicína 60, (2015).

Frenkel, M. & Lien, C. A. Eliminating residual neuromuscular blockade: a literature review. Ann. Transl. Med. 12, 65 (2024).

Interlandi, C. et al. Effects of cisatracurium in sevoflurane and propofol requirements in dog-undergoing-mastectomy surgery. Animals 12, 3134 (2022).

Costa, G. L. et al. Levobupivacaine combined with cisatracurium in peribulbar anaesthesia in cats undergoing corneal and lens surgery. Animals 13, 170 (2023).

Carregaro, A., Gerardi, P., Mujalli, M. & Martins, F. Uso de atracúrio para o bloqueio da musculatura extrínseca do bulbo ocular em cães submetidos à anestesia inalatória sob ventilação espontânea. Arq. Bras. Med. Veterinária E Zootec. 58, 1057–1063 (2006).

Carregaro, A. B. et al. Cardiopulmonary effects and eyeball centralization with low-dose atracurium in spontaneously breathing, anesthetized dogs. Ciênc. Rural 40, 1576–1582 (2010).

Covey-Crump, G. L. & Murison, P. J. Fentanyl or midazolam for co-induction of anaesthesia with propofol in dogs. Vet. Anaesth. Analg. 35, 463–472 (2008).

Hampton, C. E., Riebold, T. W. & Mandsager, R. E. Recovery characteristics of dogs following anesthesia induced with tiletamine-zolazepam, alfaxalone, ketamine-diazepam, or propofol and maintained with isoflurane. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 254, 1421–1426 (2019).

Cubeddu, F. et al. Cardiorespiratory effects and desflurane requirement in dogs undergoing ovariectomy after administration maropitant or methadone. Animals 13, 2388 (2023).

Martinez, S. et al. The safety and effectiveness of a long-acting transdermal fentanyl solution compared with oxymorphone for the control of postoperative pain in dogs: A randomized, multicentered clinical study. J. Vet. Pharmacol. Ther. 37, 394–405 (2014).

Nakaigawa, Y., Akazawa, S., Shimizu, R., Ishii, R. & Yamato, R. Effects of graded infusion rates of propofol on cardiovascular haemodynamics, coronary circulation and myocardial metabolism in dogs. Br. J. Anaesth. 75, 616–621 (1995).

Boon, J. A. Veterinary echocardiography (John Wiley & Sons, 2011).

Cruz-Benedetti, I.-C. et al. Pharmacokinetics of intramuscular alfaxalone and its echocardiographic, cardiopulmonary and sedative effects in healthy dogs. PLoS ONE 13, e0204553 (2018).

Franco, L. G. et al. Effects of ketamine constant rate infusions on cardiac biomarkers and cardiac function in dogs. Vet. Anaesth. Analg. 45, 250–259 (2018).

Fernández-Parra, R. et al. Conventional and advanced echocardiographic assessment of systolic function in dogs sedated with dexmedetomidine or acepromazine. Res. Vet. Sci. 141, 129–137 (2021).

Kibar, M., Keskin, A., Aytmirzakizi, A. & Özturk, Z. Comparison of the impacts of medet omidi ne/ke tamin e and medetomidine/propofol anesthesia and their reversal by atipamezole on echocardiographic values in dogs. Acta Vet. Eurasia 48, 167–176 (2022).

Zonca, A. et al. Pharmacokinetics of ketamine and propofol combination administered as ketofol via continuous infusion in cats. J. Vet. Pharmacol. Ther. 35, 580–587 (2012).

Arora, S. Combining ketamine and propofol (“ketofol”) for emergency department procedural sedation and analgesia: A review. West. J. Emerg. Med. 9, 20 (2008).

Thomas, M. C., Jennett-Reznek, A. M. & Patanwala, A. E. Combination of ketamine and propofol versus either agent alone for procedural sedation in the emergency department. Am. J. Health. Syst. Pharm. 68, 2248–2256 (2011).

Lee, M. et al. Anesthetic effect of different ratio of ketamine and propofol in dogs. J. Vet. Clin. 34, 234–240 (2017).

Krimins, R. A., Ko, J. C., Weil, A. B., Payton, M. E. & Constable, P. D. Hemodynamic effects in dogs after intramuscular administration of a combination of dexmedetomidine-butorphanol-tiletamine-zolazepam or dexmedetomidine-butorphanol-ketamine. Am. J. Vet. Res. 73, 1363–1370 (2012).

Almanza-Hurtado, A. et al. Hypercapnia from physiology to practice. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2022, 2635616 (2022).

Brouwer, G. J. Clinical use of neuromuscular blocking agents in dogs and cats. In Pract. 12, 113–119 (1990).

Lerche, P., Reid, J. & Nolan, A. Comparative study of propofol or propofol and ketamine for the induction of anaesthesia in dogs. Vet. Rec. 146, 571–574 (2000).

Hui, T. et al. Additive interactions between propofol and ketamine when used for anesthesia induction in female patients. J. Am. Soc. Anesthesiol. 82, 641–648 (1995).

Ravasio, G. et al. Evaluation of a ketamine-propofol drug combination with or without dexmedetomidine for intravenous anesthesia in cats undergoing ovariectomy. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 241, 1307–1313 (2012).

Hofmeister, E. H., Williams, C. O., Braun, C. & Moore, P. A. Propofol versus thiopental: Effects on peri-induction intraocular pressures in normal dogs. Vet. Anaesth. Analg. 35, 275–281 (2008).

Sumitra, M. et al. Cardiorespiratory effects of diazepam-ketamine, xylazine-ketamine and thiopentone anesthesia in male Wistar rats-a comparative analysis. Life Sci. 75, 1887–1896 (2004).

Henao-Guerrero, N. & Riccó, C. H. Comparison of the cardiorespiratory effects of a combination of ketamine and propofol, propofol alone, or a combination of ketamine and diazepam before and after induction of anesthesia in dogs sedated with acepromazine and oxymorphone. Am. J. Vet. Res. 75, 231–239 (2014).

Jacobson, J. & Hartsfield, S. Cardiorespiratory effects of intravenous bolus administration and infusion of ketamine-midazolam in dogs. Am. J. Vet. Res. 54, 1710–1714 (1993).

Dehuisser, V. et al. Effect of premedication on dose requirement, cardiovascular effects and recovery quality of alfaxalone total intravenous anaesthesia in dogs. Vet. Anaesth. Analg. 46, 421–428 (2019).

Grint, N. J., Alderson, B. & Dugdale, A. H. A comparison of acepromazine-buprenorphine and medetomidine-buprenorphine for preanesthetic medication of dogs. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 237, 1431–1437 (2010).

Keating, S. et al. Effects of acepromazine or dexmedetomidine on fentanyl disposition in dogs during recovery from isoflurane anesthesia. Vet. Anaesth. Analg. 43, 35–43 (2016).

Arenas Alvarez, A. & Bruniges, N. Management of severe hypotension in a dog undergoing transvenous pacemaker implantation following acepromazine and subsequent terbutaline administration. Vet. Rec. Case Rep. 11, 682. https://doi.org/10.1002/vrc2.682 (2023).

Ferasin, L. Feline myocardial disease: 2: Diagnosis, prognosis and clinical management. (2009) https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfms.2009.01.002.

Cerbu, M., Cerbu, C. & Papuc, I. M-mode echocardiography in canine veterinary practice: A comprehensive review of left ventricular measurements in 44 different dog breeds. Animals 13, 2986 (2023).

MacDonald, K. A., Kittleson, M. D., Garcia-Nolen, T., Larson, R. F. & Wisner, E. R. Tissue Doppler imaging and gradient echo cardiac magnetic resonance imaging in normal cats and cats with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 20, 627–634 (2006).

McMurphy, R. M., Davidson, H. J. & Hodgson, D. S. Effects of atracurium on intraocular pressure, eye position, and blood pressure in eucapnic and hypocapnic isoflurane-anesthetized dogs. Am. J. Vet. Res. 65, 179–182 (2004).

Braun, C., Hofmeister, E. H., Lockwood, A. A. & Parfitt, S. L. Effects of diazepam or lidocaine premedication on propofol induction and cardiovascular parameters in dogs. J. Am. Anim. Hosp. Assoc. 43, 8–12 (2007).

Tutunaru, A. et al. Use of cis-atracurium to maintain moderate neuromuscular blockade in experimental pigs. Vet. Anaesth. Analg. 44, 910–914 (2017).

Kastrup, M. R. et al. Neuromuscular blocking properties of atracurium during sevoflurane or propofol anaesthesia in dogs. Vet. Anaesth. Analg. 32, 222–227 (2005).

Kawahara, Y. et al. Preferable anesthetic conditions for echocardiographic determination of murine cardiac function. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 99, 95–104 (2005).

Roth, D. M., Swaney, J. S., Dalton, N. D., Gilpin, E. A. & Ross, J. Impact of anesthesia on cardiac function during echocardiography in mice. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 282, H2134–H2140 (2002).

Santos, E. et al. Echocardiographic parameters in dogs treated with acepromazine and fentanyl. Arq. Bras. Med. Veterinária E Zootec. 70, 1767–1774 (2018).

Locatelli, C. et al. Echocardiographic values in clinically healthy adult dogue de Bordeaux dogs. J. Small Anim. Pract. 52, 246–253 (2011).

Doğan, S. C., Polat, Z. A., Deren, S., Yayci, S. F. & Cetin, A. Effects of neuromuscular blocking drugs on viability of human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs). J. Int. Med. Res. 48, 0300060520910888 (2020).

Funding

Open access funding provided by The Science, Technology & Innovation Funding Authority (STDF) in cooperation with The Egyptian Knowledge Bank (EKB). There was no external funding for this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MA: the conceptualization, study design, validation, supervision, and writing edit of the original manuscript. AF: Echocardiography examination of the dogs, original draft, reviewing, editing the manuscript. RF: data curation, data analysis, data visualization. And data interpretation, and writing the original draft. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics and consent to participate

This study is in accordance with ARRIVE guidelines. All experiments conducted in this study were in strict accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. This study had an approval number from the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine- Mansoura University Animal Care and Use Committee, Egypt with the registration code R/146, and informed owner consent was obtained.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Abass, M., Farag, A. & Fahmy, R.A. Echocardiography and cardiorespiratory changes post ketofol or atracurium/ketofol on acepromazine-methadone premedicated dogs. Sci Rep 15, 20278 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-06722-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-06722-2