Abstract

Ultrafast electron diffraction (UED) experiments can extract insights into material behavior at ultrafast timescales but are limited by the manual analysis required to process several gigabytes of diffraction pattern data. The lack of real-time data prevents in situ tuning of experimental parameters toward desirable material dynamics or avoid sample damage. We demonstrate that machine learning methods based on Convolutional Neural Networks trained on synthetic and experimental diffraction patterns can perform real-time analysis of diffraction data to resolve dynamical processes in a representative material, \({\textrm{MoTe}_{2}}\), and identify signs of material damage. By building on CNN’s ability to learn compressed representations of diffraction patterns that map to distinct material dynamics, we construct Convolutional Variational Autoencoder models to track structural phase transformation in a model material system through the time trajectory of UED images in the low-dimensional latent space. Such models enable real-time steering of experimental parameters towards conditions that realize phase transformations or other desirable outcomes by mapping experimental conditions to distinct regions of the latent space. These examples show the ability of machine learning to design self-correcting diffraction experiments to optimize the use of large-scale user facilities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

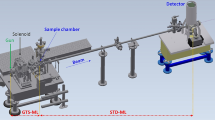

Ultrafast electron diffraction (UED) is an important technique for the characterization of sub-picosecond material dynamics with spatial resolutions approaching atomic length scales, particularly with mega-electron-volt electron sources at large scale user facilities. UED experiments, often lasting several hours, can record tens of thousands of distinct diffraction patterns amounting to several hundred gigabytes in raw image data that must be manually analyzed to infer material dynamics1. The LINAC Coherent Light Source (LCLS), for instance, has a repetition rate of 120 Hz with typical hit rates ranging from 1% to 30%2,3, depending on the performed experiment, adding up to several million distinct diffraction patterns in a single run. The next generation of light sources promises to increase data generation rate by orders of magnitude. This represents a significant problem for data analysis. Currently, hand-made algorithms are developed to search for particular features within the data with the goal to filter out a certain type of events (e.g. structural phase transformations)4, but such approaches are very time-consuming and do not generalize well to datasets from other materials5.

Data analysis through these hand-crafted algorithms is often performed over the course of several weeks after the experiments to identify interesting material phenomena or properties6. This type of post-experimental data analysis precludes in situ tuning of experimental conditions like wavelength and intensity of the optical excitation, electron beam intensity, which are instead chosen in an ad hoc manner based on the physical intuition of the researcher. Such an empirical choice of experimental conditions is not guaranteed to result in the observation of desired material dynamics. It is also likely that the chosen experimental conditions can result in damage to the material samples and thus not lead to the collection of useful data.

Machine learning (ML) is a promising solution to rapidly classify or predict molecular and crystal structure based on the observed diffraction pattern7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22. ML methods have been used to solve existing challenges related to diffraction and reciprocal space mapping23,24,25,26,27,28. ML algorithms have also been used for experimental design of scattering studies at user facilities, but such studies have been narrowly limited to optimization of beam and image quality29,30,31 and not focused on image classification. Diffraction patterns are known to be excellent feature vectors for classifying material structure9, and CNNs have proven to be interpretable ML tools to classify and analyze such diffraction patterns11. The success of neural networks in the regime of image processing, classification, object detection and segmentation provides a scalable method to tackle the challenge of classification of large UED datasets.

While the application of ML approaches to the analysis of x-ray and electron diffraction patterns is well-established, there exist significant qualitative differences between conventional electron diffraction and ultrafast pump-probe electron diffraction. Therefore, existing ML pipelines require modifications before they can be effectively applied for analysis of UED data. The primary challenge in conventional electron or x-ray diffraction is to identify the crystal structure and chemical composition of a material from the diffraction pattern. ML algorithms developed for this purpose are required only to distinguish between qualitatively different diffraction patterns and classify them according to their respective point groups32,33,34. On the other hand, the primary motive for UED experiments is to identify and distinguish between dynamic processes in materials, including defect formation, phonon excitation, and phase transformation, which only subtly affect the measured diffraction pattern of the material. Therefore, ML models for analyzing UED data must be suitable for analyzing small or subtle changes in the UED diffraction data. Further, diffraction patterns from conventional sources are obtained over relatively large time-scales of a few milliseconds, at high electron currents35. This results in excellent signal-to-noise ratios, with well-defined diffraction peak positions and widths. UED experiments collect diffraction patterns using femto-second electron pulses that result in significant shot noise, particularly for low-flux electron sources and analysis of diffuse scattering36. Therefore, ML models for analysis of UED data must be robust against source and detector noise.

Here, we show that neural networks can be used to classify large quantities of diffraction data if they are previously trained on a qualitatively similar labeled synthetic dataset. Specifically, we describe a scheme that translates real-time changes in the measured reciprocal-space diffraction patterns to changes in the molecular configuration of a prototypical two-dimensional material, \({\textrm{MoTe}_{2}}\), to identify desirable dynamical changes like structural phase transformations or understand material damage in real-time during experiments. We further describe how generative models, combined with convolutional neural networks, can identify the impact of different experimental parameters on the observed diffraction patterns and predict which experimental conditions are most likely to drive the material to explore interesting part of the phase space that result in previously unknown dynamics or properties.

Results

Convolutional neural networks (CNN) for classifying features in reciprocal space images

\({\textrm{MoTe}_{2}}\) is a prototypical transition metal dichalcogenide whose electronic properties and phase transformations are promising for future low-dimensional opto-electronic device applications. \({\textrm{MoTe}_{2}}\) has two stable polytypes - 2H and 1T’, which show hexagonal and monoclinic crystal respectively37,38,39. Reversible transformation between these two phases has been demonstrated through various external stimuli, such as thermal excitation, electronic gating and chemical doping, all of which can cause collective atomic displacements necessary to convert the 2H structure to the 1T’ structure40,41,42,43. Due to its strong structural response to optical excitation, Ultrafast electron diffraction experiments are an ideal probe to investigate light-driven structural changes in \({\textrm{MoTe}_{2}}\).

However, optical excitation induced by the UED pump probe can also result in other structural changes beyond phase transformation. Moderate excitation can induce thermal heating resulting in random atomic displacements, or the activation of specific phonon modes, which results in correlated motion of atoms. More intense excitation can induce thermally-driven vacancy formation and anisotropic heating, which can lead to lattice expansion and other lattice distortions. The strongest excitations lead to Te sublimation, material degradation and changes in material composition. It is difficult to identify a priori, the exact optical excitation parameters that result in selective excitation of those phonon modes responsible for the 2H-1T’ phase transformations and those responsible for material degradation.

We demonstrate convolutional neural networks that can distinguish between the different deformations in \({\textrm{MoTe}_{2}}\) induced by optical excitation, based on differences in their diffraction pattern Fig. 1. shows the layout of the convolutional neural network used to classify observed diffraction patterns. The CNN consists of 3 CNN blocks, each consisting of a pair of WideResNet layers44 (each containing a pair of convolutional layers and a dropout layer) and a max-pooling layer, followed by a fully-connected network that classifies the input diffraction pattern into one of seven classes, each corresponding to a different type of structural distortion expected in the UED experiment.

CNN architecture: (a) schematic of a single WideResNet layer containing convolution and dropout elements. (b) CNN architecture composed of three blocks, each containing two WideResNet layers and a max-pool layer for representation learning, followed by a single fully-connected layer for classification of noisy diffraction patterns based on structural changes in the material.

We train the CNN model, CNNSyn, using synthetic data for CNN training. Specifically, we simulate diffraction patterns from monolayer \({\textrm{MoTe}_{2}}\) crystal with 7 types of structural distortions, as illustrated in Fig. 2 and in the Methods section. The first set of images, Class 0, is generated from pristine defect-free and distortion-free \({\textrm{MoTe}_{2}}\) 2H crystal with random thermal atomic displacements. Class 1 is generated from 2H \({\textrm{MoTe}_{2}}\) structures that contain various concentrations of Mo and Te vacancies. The next set of images, Class 2, is created from 2H \({\textrm{MoTe}_{2}}\) structures that contain various degrees of isotropic and anisotropic lattice deformation. The fourth set of images, Class 3, is formed from 2H \({\textrm{MoTe}_{2}}\) structures that contain collective displacement due to various phonon modes. The next set of images, Class 4, is created from 1T’ \({\textrm{MoTe}_{2}}\) structures that contain various concentrations of Mo and Te vacancies. The sixth set of images, Class 5, is generated from 1T’ \({\textrm{MoTe}_{2}}\) structures that contain various degrees of isotropic and anisotropic lattice deformation. The final set of images (Class 6) is produced from 1T’ \({\textrm{MoTe}_{2}}\) structures that contain collective deformation due to various phonon modes.

Due to the lack of high-quality, well-annotated experimental diffraction patterns for supervised learning, synthetic data is widely used as a potential method to generate scalable datasets in electron microscopy settings45,46,47,48, because physics-based simulations and data generation and labeling, can generate bias-free and reproducible data across all possible experimental condition in a high-throughput manner at substantially lower cost. Furthermore, UED analysis relies on relatively subtle changes in diffraction patterns to identify material dynamics. Therefore, we provide this inductive bias to the diffraction data by subtracting the diffraction pattern of a pristine, defect-free, un-deformed 2H in its vibrational ground state from the input image. Specifically, this subtraction is used to generate a 2-channel image - positive deviations (i.e. increase in intensity) from the diffraction pattern of the pristine, defect-free, un-deformed 2H in its vibrational ground state are stored in the red channel, while negative deviations (i.e. decrease in intensity) are stored in the blue channel. This unique data modification greatly increases the variance in the input data and improves the sensitivity of the CNNSyn model to small variations in the diffraction pattern. Example training data from different class both before and after subtraction, is shown in Fig. 2. It can be clearly seen that the signatures of each class of lattice distortion is encoded in the distribution of red and blue values over the different regions of the diffraction image. The CNN was trained to minimize the cross-entropy loss for this multi-class classification problem using standard techniques (see Methods section).

The confusion matrix in Fig. 3 summarizes the performance of CNNSyn in classifying structural distortions in \({\textrm{MoTe}_{2}}\). CNNSyn demonstrates high accuracy and reliability by correctly identifying the majority of instances across the dissimilar classes. The lowest class accuracy for the CNN was recorded for Class 2, where 967 out of 996 instances were classified correctly, reflecting an accuracy 97%. The primary misclassifications suggest some feature overlap between Classes 0 and 2. The confusion matrix also includes an additional Class 6, which contains diffraction images that do not belong to any of the other five classes. The purpose of this class was to assess the model’s ability to recognize and classify images that exhibit structural distortions that don’t belong to any of the predefined categories. These results highlight the CNN’s Overall high accuracy - greater than 98%- and effectiveness in classifying different structural distortions in \({\textrm{MoTe}_{2}}\). Such a high accuracy on synthetic data is known to correspond to approximately 94% accuracy in experimental test data, as seen in other deep learning approaches to crystallography49.

Transfer learning for experimental UED data

ML models for conventional x-ray and electron diffraction benefit from existing large and curated datasets of diffraction patterns from known materials and crystal structures. In contrast, the public availability of ultrafast electron diffraction datasets is very limited, since UED experiments can only be performed at a limited number of facilities with MeV electron beams. Therefore, in order to develop a general scheme for the design and analysis of UED data, we propose a two-stage approach that uses easily-generated synthetic data to develop a CNN-based classification model, which is subsequently updated to use experimental UED data through transfer learning.

To demonstrate the feasibility of transfer learning, we update the CNNSyn model developed in the previous section using 77 experimental images. Transfer learning is performed by retraining the model against the experimental UED images at a significantly reduced learning rate (0.001 vs 0.01 for training with synthetic data). All model parameters, including weights and biases for the representation layer (WideResNet blocks) and the classification layer (FNN layer) are tuned during the retraining process. Figure 4 shows representative input images from the synthetic and experimental UED dataset and the performance of the CNNSyn model and the transfer-learned CNNExp model on the experimental test dataset. To demonstrate the performance of the retrained model, we plot the predicted classification of a previously reported UED dataset of pump-probe experiments on \({\textrm{MoTe}_{2}}\) monolayers. Manual analysis of the \({\textrm{MoTe}_{2}}\) UED patterns demonstrated the excitation of phonon modes (predominantly the M-point and K-point phonon modes4) due to optical excitation. CNNSyn predicts unphysical changes in structure classification over short timescales of 10 ps. The transfer-learned CNNExp model performs significantly better on this experimental dataset, preventing the unphysical classification changes on short timescales, as well as predicting the emergence of phonon modes after optical excitation, consistent with experimental observations. This result demonstrates that the two-stage scheme proposed in this section, including transfer learning, is a feasible approach to employ for real-time classification of experimental UED patterns.

Transfer learning: (a) time-trajectory of experimental UED images. (b) CNNSyn, trained only on synthetic data, has poor performance in classifying experimental data, but transfer-learned CNNExp model demonstrates no unphysical classifications and indicates the presence of phonons after optical excitation.

Experimental design using generative C-VAE and self-supervised learning

Experimental design for ultrafast electron diffraction involves the identification of experimental conditions (e.g. beam power, repetition rate etc.) that can result in desirable changes to the sample’s diffraction pattern (e.g. phase transformations and excitations of specific vibrational modes). In order to steer experimental conditions towards promising regions of the phase-space, we develop a generative Convolutional Variational Autoencoder (C-VAE) model (Fig. 5) to identify a collapsed low-dimensional representation of different diffraction patterns within the model’s latent space, with similar diffraction patterns being clustered together within the low-dimensional latent space.

In the case of \({\textrm{MoTe}_{2}}\), an example of a promising experimental condition is one responsible for transforming 2H \({\textrm{MoTe}_{2}}\) to 1T’ \({\textrm{MoTe}_{2}}\). To identify such promising conditions, we first compute the latent space distribution of diffraction patterns from both 2H \({\textrm{MoTe}_{2}}\) and 1T’ \({\textrm{MoTe}_{2}}\), Figure 6. Additionally, we compute the latent space distribution of a set of images that are pixel-by-pixel interpolations of diffraction patterns from a desirable dynamical process, e.g. 2H \({\textrm{MoTe}_{2}}\) and 1T’ \({\textrm{MoTe}_{2}}\). The latent space distribution of these interpolated images represents the expected trajectory of diffraction patterns of \({\textrm{MoTe}_{2}}\) samples undergoing phase transformation from the 2H to 1T’ crystal structures. On the other hand, unexpected or undesirable structural changes, such as lattice melting or degradation will lead to molecular configurations and diffraction patterns that are significantly different from those of either 2H or 1T’ \({\textrm{MoTe}_{2}}\). Therefore, these diffraction patterns from defective structures (and the experimental conditions leading to them) will be represented in the latent space as clusters distinct from those of the images representing the 2H, 1T or interpolated diffraction patterns.

By exploiting the well-structured nature of the latent space in C-VAE, which ensures that similar diffraction patterns are clustered together, such models can identify, in real-time, a promising experimental condition by computing the n-dimensional Euclidean distance between a given diffraction pattern and a line connecting the 2H and 1T’ patterns in the VAE’s latent space. Distance measures in the latent space of generative models have previously been used as a metric for the similarity of input images or molecular structures in materials chemistry and other engineering applications50,51,52. By identifying experimental conditions that result in diffraction patterns close to the 2H and 1T’ patterns in the latent space, we can drive experiments towards conditions that induce the structural phase transformation.

Types of \({\textrm{MoTe}_{2}}\) diffraction patterns: (a) Representative crystal structures of 2H, 1T’ and defective \({\textrm{MoTe}_{2}}\) and \({\textrm{MoTe}_{2}}\) undergoing phase transformation. (b) Diffraction patterns of different \({\textrm{MoTe}_{2}}\) configurations that cluster in different regions of the C-VAE latent space.

The encoder (decoder) of the C-VAE is a sequence of three convolutional (deconvolutional) layers followed by batchnorm and activation (ReLU) layers. The encoder performs a dimensionality reduction of the input diffraction pattern to a four-dimensional latent space. During C-VAE training, the Adam optimizer was used to update model parameters. The C-VAE model is trained to reduce the total loss, which is a sum of two components – Mean Squared Error, and Kullback-Leiber Divergence. The Mean Squared Error (MSE) loss quantifies the difference between input and reconstructed diffraction pattern image53. The Kullback-Leibler divergence loss (KL) which contribute in regularizing and shaping the latent space into a Gaussian probability distribution54.

Figure 7 shows the t-SNE projection of the latent space representation of different diffraction patterns from five \({\textrm{MoTe}_{2}}\) crystals, 2H \({\textrm{MoTe}_{2}}\), 1T’ \({\textrm{MoTe}_{2}}\), pixel-by-pixel interpolation of diffraction patterns between 2H and 1T’ \({\textrm{MoTe}_{2}}\), crystals undergoing a phase transformation, and defective or molten \({\textrm{MoTe}_{2}}\). The region enclosed by the distribution of 2H, 1T’, and interpolated \({\textrm{MoTe}_{2}}\) diffraction patterns defines the region of expected diffraction patterns due to the phase transformation. Synthetic diffraction patterns of \({\textrm{MoTe}_{2}}\) crystals undergoing the 2H-1T’ phase transformation lies within the expected region. In contrast, the diffraction patterns corresponding to the defective or molten \({\textrm{MoTe}_{2}}\) fall outside the defined region, indicating that experimental conditions that result in such diffraction patterns are not optimal in inducing a 2H-1T’ phase transformation.

Experimental design using the VAE latent space: Distribution of 2H, 1T’ and interpolated diffraction patterns defines the trajectory of \({\textrm{MoTe}_{2}}\) crystals undergoing a phase transformation. Diffraction patterns from defective or molten \({\textrm{MoTe}_{2}}\) structures fall outside the region describing the phase transformation.

Discussion

In conclusion, we have developed two machine learning methods, based on convolutional neural networks to provide real-time analysis of UED images and assist in real-time design of UED experimental parameters. CNNSyn, trained on synthetic data, and CNNExp, trained by transfer learning, are both shown to be effective tool to classify UED images and identify defect formation, lattice distortions and phase transformations in a model material system, \({\textrm{MoTe}_{2}}\). Convolutional VAEs (C-VAEs) can perform dimensionality reduction and clustering of different crystal structures. Euclidean distance metrics in the latent space of the C-VAE provide a metric to identify changes in experimental parameters required to induce desired structural changes or phase transformations.

Methods

Synthetic data generation for CNNSyn and VAE training

Simulated electron diffraction patterns are generated by calculating the static structure factor on a uniform \(261 \times 261\) reciprocal grid centered on the origin using the standard formula given below.

where the intensity I at reciprocal point \({\textbf{q}}\) depends on positions, \(\mathbf {R_i}\), and atomic form factors, \(f_i\), of Mo and Te atoms in the crystal structure. Diffraction patterns are generated for seven classes of the crystals – 2H and 1T’ crystal with defects, lattice distortion, and phonons, as well as pristine defect-free 2H crystal as a reference. For UED simulations, defective crystals are constructed by creating vacancies at up to 20% of lattice sites. Distorted lattices are constructed by applying a random strain tensor, with normal and shear components up to 10%. Crystal structures with phonon modes are generated by displacing the atoms from the perfect crystal structure along a random phonon eigenmode generated using the phonopy package55. Thermal displacement of atoms is included in the generation of all synthetic data. Each diffraction pattern in training and test data includes up to 50% noise to replicate the noise level of experimental UED data. The training dataset is augmented by 2-fold rotation of each diffraction image56.

Unlike other ML models for diffraction pattern classification, ML models for UED must emphasize identification and classification of subtle changes in diffraction patterns. Therefore, synthetic data for the CNNSyn model is generated as a 2-channel RGB image, where the red and blue channels capture the positive and negative deviations from the diffraction pattern of a pristine defect-free 2H crystal respectively. In all, a large dataset comprising 70,000 synthetic diffraction images was generated, with raw diffraction images used for VAE training and subtracted, 2-channel diffraction images used for CNNSyn training.

CNN models for classifying UED diffraction patterns

The CNN contains 3 WideResNet blocks, made up of convolutional and pooling blocks connected by rectified linear unit (ReLU) activation functions. Dropout layers were included in each WideResNet block to prevent overfitting. Network weights are updated using the Adam optimizer. Training was conducted over a maximum 40 epochs, with early stopping based on target validation accuracy of 85% and patience of 2 epochs. Hyperparameter tuning was performed by varying the learning rate and batch size across twelve runs.

VAE models for experiment design

The VAE architecture comprises an encoder and decoder network, trained to encode input images into a lower-dimensional latent space and subsequently decode them back to their original dimensions. The original dataset images were resized to \(256 \times 256\) pixels and transformed into tensors. The batch sizes were 64 and 20 for training and testing, respectively. 3-channel input images pass through four convolutional layers and ReLU activations in the encoder. The resulting feature map is flattened and passed through two fully connected layers to produce the mean and log-variance of the latent space distribution. The decoder takes the latent vectors as input through a fully-connected layer to upscale the latent vectors to match the flattened feature map size, followed by four transposed convolutional layers to reconstruct the image. ReLU activations were utilized in all layers except the final layer, which used a sigmoid activation to produce outputs between 0 and 1., reflecting the intensity of each pixel in the \(256 \times 256\) image. We trained the VAE model using the Adam optimizer with a learning rate of \(1.5 \times 10^{-4}\) over 100 epochs.

Data availability

All code for CNN and C-VAE models is available at https://github.com/MATSAIL-TAMU/ML-UED. Synthetic data and labels for CNN training is available from the corresponding author, Aravind Krishnamoorthy, on request.

References

Filippetto, D. et al. Ultrafast electron diffraction: Visualizing dynamic states of matter. Rev. Mod. Phys. 94, 045004 (2022).

...Emma, P. et al. First lasing and operation of an ångstrom-wavelength free-electron laser. Nat. Photon. 4, 641. https://doi.org/10.1038/nphoton.2010.176 (2010).

Bostedt, C. et al. Linac coherent light source: The first five years. Rev. Mod. Phys. 88, 015007. https://doi.org/10.1103/RevModPhys.88.015007 (2016).

...Krishnamoorthy, A. et al. Optical control of non-equilibrium phonon dynamics. Nano Lett. 19, 4981. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.nanolett.9b01179 (2019).

Ma, Z.-R., Qi, F.-F. & Xiang, D. Probing molecular dynamics with ultrafast electron diffraction. Chin. J. Chem. Phys. 34, 15 (2021).

Ge, M., Su, F., Zhao, Z. & Su, D. Deep learning analysis on microscopic imaging in materials science. Mater. Today Nano 11, 100087 (2020).

Ekeberg, T., Engblom, S. & Liu, J. Machine learning for ultrafast x-ray diffraction patterns on large-scale GPU clusters. Int. J. High Perform. Comput. Appl. 29, 233. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094342015572030 (2015).

Laanait, N., Zhang, Z. & Schlepütz, C. Imaging nanoscale lattice variations by machine learning of X-ray diffraction microscopy data. Nanotechnology 27, 374002. https://doi.org/10.1088/0957-4484/27/37/374002 (2016).

Meredig, B. & Wolverton, C. A hybrid computational-experimental approach for automated crystal structure solution. Nat. Mater. 12 ( 2012). https://doi.org/10.1038/nmat3490

Park, W. et al. Classification of crystal structure using a convolutional neural network. IUCrJ 4 ( 2017). https://doi.org/10.1107/S205225251700714X

Wang, H. et al. Rapid identification of X-ray diffraction patterns based on very limited data by interpretable convolutional neural networks. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 60, 2004. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jcim.0c00020 (2020).

Kaufmann, K. et al. Crystal symmetry determination in electron diffraction using machine learning. Science 367, 564. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aay3062 (2020).

Zaloga, A., Stanovov, V., Bezrukova, O., Dubinin, P. & Yakimov, I. Crystal symmetry classification from powder X-ray diffraction patterns using a convolutional neural network. Mater. Today Commun. 25, 101662. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mtcomm.2020.101662 (2020).

Zimmermann, J. et al. Deep neural networks for classifying complex features in diffraction images. Phys. Rev. E 99 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevE.99.063309

Ziletti, A., Kumar, D., Scheffler, M. & Ghiringhelli, L. Insightful classification of crystal structures using deep learning. Nat. Commun. 9 ( 2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-05169-6

Vecsei, P., Choo, K., Chang, J. & Neupert, T. Neural network-based classification of crystal symmetries from X-ray diffraction patterns ( 2018)

Tiong, L., Kim, J., Han, S. S. & Kim, D. Identification of crystal symmetry from noisy diffraction patterns by a shape analysis and deep learning. npj Comput. Mater. 6 ( 2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-020-00466-5

Cherukara, M. et al. Ai-enabled high-resolution scanning coherent diffraction imaging. Appl. Phys. Lett. 117, 044103. https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0013065 (2020).

Suzuki, Y., Hino, H., Hawai, T., Saito, K., Kotsugi, M. & Ono, K. Symmetry prediction and knowledge discovery from X-ray diffraction patterns using an interpretable machine learning approach. Sci. Rep. 10 ( 2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-77474-4

Yann , M. & Tang, Y. Learning deep convolutional neural networks for X-ray protein crystallization image analysis. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence. Vol. 30 ( 2016). https://doi.org/10.1609/aaai.v30i1.10150

Ra, M. et al. Classification of crystal structures using electron diffraction patterns with a deep convolutional neural network. RSC Adv. 11, 38307. https://doi.org/10.1039/D1RA07156D (2021).

Bridger, A., David, W., Wood, T., Danaie, M. & Butler, K. Versatile domain mapping of scanning electron nanobeam diffraction datasets utilising variational autoencoders, npj Comput. Mater. 9 ( 2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-022-00960-y

Scheinker, A. & Pokharel, R. Adaptive 3D convolutional neural network- based reconstruction method for 3D coherent diffraction imaging. J. Appl. Phys. 128, 1. https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0014725 (2020).

Cherukara, M., Nashed, Y. & Harder, R. Real-time coherent diffraction inversion using deep generative networks ( 2018)

Xu, W. & LeBeau, J. A deep convolutional neural network to analyze position averaged convergent beam electron diffraction patterns. Ultramicroscopy 188 ( 2017). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ultramic.2018.03.004

Rupp, D. et al. Generation and structure of extremely large clusters in pulsed jets. J. Chem. Phys. 141, 044306. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4890323 (2014).

Barke, I. et al. The 3D-architecture of individual free silver nanoparticles captured by X-ray scattering. Nat. Commun. 6, 6187. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms7187 (2015).

Lundholm, I. et al. Considerations for three-dimensional image reconstruction from experimental data in coherent diffractive imaging. IUCrJ 5, 531. https://doi.org/10.1107/S2052252518010047 (2018).

Zhang, Z. et al. Toward fully automated UED operation using two-stage machine learning model. Sci. Rep. 12 ( 2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-08260-7

Ji, F. et al. Multi-objective Bayesian active learning for MeV-ultrafast electron diffraction. Nat. Commun. 15 ( 2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-48923-9

Zhang, Z. et al. Accurate prediction of mega-electron-volt electron beam properties from UED using machine learning. Sci. Rep. 11 ( 2021) https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-93341-2

Szymanski, N. J. et al. Adaptively driven X-ray diffraction guided by machine learning for autonomous phase identification. npj Comput. Math. 9, 31 ( 2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-023-00984-y

Salgado, J. et al. Automated classification of big X-ray diffraction data using deep learning models. npj Comput. Mater. 9 ( 2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-023-01164-8

Chen, J. et al. Automated crystal system identification from electron diffraction patterns using multiview opinion fusion machine learning. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 120, e2309240120. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2309240120 (2023).

Filippetto, D. et al. Ultrafast electron diffraction: Visualizing dynamic states of matter. Rev. Mod. Phys. 94, 045004. https://doi.org/10.1103/RevModPhys.94.045004 (2022).

Kealhofer, C. , Lahme, S., Urban, T. & Baum, P. Signal-to-noise in femtosecond electron diffraction. Ultramicroscopy 159, 19 ( 2015). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ultramic.2015.07.004

Zhao, W. et al. Synthesis and electronic structure of atomically thin 2h-mote2. Nanoscale 17, 10901. https://doi.org/10.1039/D4NR05191B (2025).

Tao, L., Zhou, Y. & Xu, J.-B. Phase-controlled epitaxial growth of mote2: Approaching high-quality 2D materials for electronic devices with low contact resistance. J. Appl. Phys. 131, 110902. https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0073650 (2022).

Yelgel, C. et al. Engineering the electronic properties of mote2 via defect control. Sci. Technol. Adv. Mater. 25, 2388502 ( 2024). https://doi.org/10.1080/14686996.2024.2388502

Wang, Y. et al. Structural phase transition in monolayer mote2 driven by electrostatic doping. Nature 550 ( 2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/nature24043

Shi, J. et al. Intrinsic 1\({T}^{{\prime } }\) phase induced in atomically thin 2h-mote2 by a single terahertz pulse. Nat. Commun. 14 ( 2023) https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-41291-w

Kowalczyk, H. et al. Gate and temperature driven phase transitions in few-layer mote2. ACS Nano 17, 6708. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsnano.2c12610 (2023).

Awate, S. S. et al. Strain-induced 2h to 1t’ phase transition in suspended mote2 using electric double layer gating. ACS Nano 17, 22388. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsnano.3c04701 (2023).

Zagoruyko, S. & Komodakis, N. Wide Residual Networks ( 2017). arXiv:1605.07146 [cs.CV]

Cid-Mejias, A., Alonso-Calvo, R., Gavilan, H., Crespo, J. & Maojo, V. A deep learning approach using synthetic images for segmenting and estimating 3d orientation of nanoparticles in em images. Comput. Methods Prog. Biomed. 202, 105958 ( 2021). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmpb.2021.105958

Ziatdinov, M., Ghosh, A., Wong, C. & Kalinin, S. Atomai framework for deep learning analysis of image and spectroscopy data in electron and scanning probe microscopy. Nat. Mach. Intell. 4 ( 2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42256-022-00555-8

Lynch, M. J., Jacobs, R., Bruno, G., Patki, P., Morgan, D. & Field, K. G. Accelerating domain-aware electron microscopy analysis using deep learning models with synthetic data and image-wide confidence scoring ( 2024). arXiv:2408.01558 [cs.CV]

DaCosta, L. R., Sytwu, K., Groschner, C. K. & Scott, M. C. A robust synthetic data generation framework for machine learning in high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM). npj Comput. Mater. 10 ( 2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-024-01336-0

Souza, A. et al. Deepfreak: Learning crystallography diffraction patterns with automated machine learning ( 2019). arXiv:1904.11834 [cs.LG]

Tsutsumi, M., Saito, N., Koyabu, D. & Furusawa, C. A deep learning approach for morphological feature extraction based on variational auto-encoder: an application to mandible shape. NPJ Syst. Biol. Appl. 9, 30. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41540-023-00293-6 (2023).

Bjerrum, E. J. & Sattarov, B. Improving chemical autoencoder latent space and molecular de novo generation diversity with heteroencoders. Biomolecules 8 ( 2018). https://doi.org/10.3390/biom8040131

Sellner, M., Mahmoud, A. & Lill, M. Efficient virtual high-content screening using a distance-aware transformer model. J. Cheminform. 15 ( 2023)

Regenwetter, L., Nobari, A. H. & Ahmed, F. Deep generative models in engineering design: A review. J. Mech. Des. 144, 071704 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1115/1.4053859. https://asmedigitalcollection.asme.org/mechanicaldesign/article-pdf/144/7/071704/6866682/md_144_7_071704.pdf.

Asperti, A. & Trentin, M. Balancing reconstruction error and Kullback-Leibler divergence in variational autoencoders. IEEE Access 8, 199440 (2020).

Togo, A., Chaput, L., Tadano, T. & Tanaka, I. Implementation strategies in phonopy and phono3py. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 35, 353001. https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-648X/acd831 (2023).

Oviedo, F. ET AL. Fast and interpretable classification of small X-ray diffraction datasets using data augmentation and deep neural networks ( 2019). arXiv:1811.08425 [physics.data-an]

Acknowledgements

MS and SEB are thankful to Qatar Foundation and Texas A&M University at Qatar for the research funding of the mechanical engineering high-impact project and the fellowship program.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MS and AK performed the materials modeling and machine learning research. MS and SEB prepared and reviewed all figures in the manuscript. All authors wrote and reviewed the main manuscript text.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing intereests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shaaban, M., El-Borgi, S. & Krishnamoorthy, A. Machine learning for experimental design of ultrafast electron diffraction. Sci Rep 15, 23059 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-06779-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-06779-z