Abstract

Congenital heart disease (CHD) is the most common type of birth defects in humans. Genetic factors have been identified as an important contributor to the etiology of CHD. However, the underlying genetic causes in most individuals remain unclear. Here, 101 individuals with CHD and their unaffected parents were included in this study. Chromosomal microarray analysis (CMA) as a first-tier clinical diagnostic tool was applied for all affected individuals, followed by trio-based whole exome sequencing (WES) of 76 probands and proband-only WES of 3 probands. We detected aneuploidies in 2 individuals (trisomy 21 and monosomy X), 21 pathogenic and likely pathogenic copy number variants (CNVs) in 19 individuals, and pathogenic and likely pathogenic SNVs/InDels in 8 individuals. The combined genetic diagnostic yield was 28.7%, including 20.8% with chromosomal abnormalities and 7.9% with sequence-level variants. Eighteen CNVs in 17 individuals were associated with 13 recurrent chromosomal microdeletion/microduplication syndromes, the most common being 22q11.2 deletion syndrome. Pathogenic/likely pathogenic sequence-level variants were identified in 8 genes, including GATA6, FLNA, KANSL1, TRAF7, KAT6A, PKD1L1, RIT1, and SMAD6. Trio sequencing facilitated the identification of pathogenic variation (55.6% were de novo missense variants). In individuals with extracardiac features, the overall detection rate was significantly higher (61.5%) than in individuals with isolated CHD (17.3%) (P = 4.6 × 10− 3). Our study further emphasized the importance of combining CMA and trio-WES for clinical genetic testing of individuals with CHD. Trio-based WES should be part of the diagnostic algorithm.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Congenital heart disease (CHD) is the most common type of birth defect with an incidence of approximately 10 per 1,000, ranging from 2.3 to 13.1 in 1,000 live births based on the geographic region, and leading to significant morbidity and mortality in childhood worldwide1,2,3,4. It has been estimated that contribution of genetic factors to the etiology is about 40%, or even up to 90% of CHD cases, including chromosome aneuploidies, copy number variations (CNVs), and single nucleotide variants (SNVs)5,6but so far, the genetic etiology has only been identified in ~ 30% of individuals with CHD indicating that many genetic causes are still undetermined7,8,9. Moreover, the pathogenicity of some genetic variants is incompletely understood partly due to lack of supporting segregation data and incomplete penetrance of the phenotypes10.

Chromosomal microarray analysis as a first-tier clinical diagnostic tool in patients with developmental delay/intellectual disability (DD/ID), autism spectrum disorders (ASD), and multiple congenital anomalies (MCA), has revealed that rare CNVs are important contributors to CHD in 3 − 25% of CHD patients with wide variation depending on testing platform and the cohort characteristics9,11,12. High-throughput sequencing allows the detection of additional types of pathogenic genetic variations in individuals with CHD13,14. Patients with CHD have increased risks of extracardiac MCA and neurodevelopmental disorders (NDDs), including CNVs, have been implicated in both CHD and NDDs15,16. Therefore, studying genetic abnormalities in patients with CHD is not only uncovering the genetic etiology of CHD, but also contributing to a better understanding of the molecular mechanisms of CHD and related disorders including MCA and NDDs15,16,17. The contribution of rare genetic variants to CHD is well-established11,12,13,14,18however the overall diagnostic yield of CNVs and SNVs in affected children is still uncertain. Identifying a genetic diagnosis in patients with CHD can facilitate targeted therapies and interventions, genetic counseling for families, and monitoring of manifestations of MCA and NDDs.

In this study, we investigated clinically relevant genetic variants in a Chinese cohort of 101 patients with CHD and their non-affected parents using chromosomal microarray analysis (CMA) followed by trio-based exome sequencing. We also assessed the clinical implications of genetic testing, including the probability of extra-cardiac MCA and NDDs features, and recurrence risks of CHD in family members.

Results

Demographics of the study population

The 101 CHD cases consisted of 56.4% (57/101) male and 43.6% (44/101) female patients ranging in age from 1 day to 9 years old with mean age of 9 month-old. The cohort could be classified into 74.3% (75/101) isolated and 25.7% (26/101) non-isolated CHD based on the absence or presence of extra-cardiac MCA and NDDs (Table 1). The mean age of onset was 9.5 months in isolated CHD group while it was 8.5 months in non-isolated CHD group, indicating no statistical difference between two groups (P = 0.75).

According to the Botto criteria19the cohort of CHD cases could be classified into 3 groups by clinical findings (baby phenotype) and complexity of cardiac phenotype, including 66.3% (67/101) simple, 29.7% (30/101) association and 4% (4/101) complex (Table 1). The cohort of CHD cases was also categorized into different subgroups by cardiac complexity category based on the Botto criteria, including 10.9% (11/101) with conotruncal, 13.9% (14/101) with atrioventricular septal defect, 3%(3/101) with left ventricular outflow tract obstruction, 4%(4/101) with right ventricular outflow tract obstruction, 56.4%(57/101) with septal defect, 1%(1/101) with single ventricle/complex, 6.9%(7/101) with septal plus LVOTO and 4%(4/101) with septal plus RVOTO based on Botto classification (Table 2).

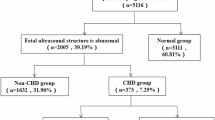

Diagnostic yield of CMA and WES

We identified 12 pathogenic/ likely pathogenic CNVs and 2 aneuploidies in 12 CHD cases and 6 VUS in 6 cases using Affy-HD array, and then detected 9 pathogenic/ likely pathogenic CNVs in 9 CHD cases and 1 VUS in 1 case using Illumina-CytoSNP-12 array. In total, we identified 21 pathogenic/ likely pathogenic CNVs in 19 CHD cases, 2 aneuploidies in 2 cases and 7 VUS in 7 cases by CMA (Table 2, Table S2). The stringent diagnostic yield of CMA for this CHD cohort was 20.8% (21/101) when only considering pathogenic/likely pathogenic CNVs and aneuploidies. We then applied trio-based whole exome sequencing (WES) for remaining patients without pathogenic/likely pathogenic CNVs and aneuploidies, and found 8 probands carried pathogenic/likely pathogenic SNVs, which resulted in a general diagnostic yield of CMA and WES for this cohort was 28.7% (29/101) (Table 1).

We compared the diagnostic yield between both groups of isolated and non-isolated CHD. In the 75 isolated CHD cases, 7 CNVs, 1 monosomy X and 5 SNVs were detected and the diagnostic yield was 17.3%. In the 26 non-isolated CHD cases with extracardiac phenotypes, we identified 16 genetic diagnoses (diagnostic yield of 61.5%), including 1 trisomy 21, 12 CNVs and 3 SNVs/InDels, indicating that the diagnostic yield was significantly higher than that in individuals with isolated CHD (P = 4.6 × 10− 3). The diagnostic yield of CNVs and aneuploidies in non-isolated CHD group using CMA was 50.0% which was also significantly higher than that in isolated CHD group (10.7%) (P = 3.3 × 10− 4), suggesting a significant statistical significance. While there was no statistical significance of the positive rate of SNVs between the two groups using WES (P = 0.23) (Table 1). As far as the three cardiovascular malformation groups of simple, association and complex concerned, the detection rate was ranged from 25.0% in 4 individuals with complex, 23.9% in individuals with simple, and 43.3% in individuals with association, though no statistical significance (P = 0.31) (Table 1). We then compared the detection rates among different CHD subgroups, and found no statistical significance (Table 2).

Pathogenic/ likely pathogenic CNVs and aneuploidies found using CMA

The 2 aneuploidies identified by CMA included 1 monosomy X in a 4-month-old girl (ID: J005) with Perimembranous ventricular septal defect (VSD pm) and 1 trisomy 21 in an 11-day-old boy (ID: J143) with complete atrioventriclar septal defect as well as mild craniofacial anomalies (Table S1). The 21 pathogenic/ likely pathogenic CNVs identified in 19 individuals with CHD included 16 (76.2%) deletions and 5 (23.8%) duplications distributed in 11 different chromosomes (Fig. 1; Table 3). Of which, 14 (66.7%) were de novo, 4 (19.0%) paternally and 3 (14.3%) maternally inherited. The size of the CNVs varied from 512 kb to 71.1 Mb. The majority of CNVs (15/21, 71.4%) were smaller than 10 Mb in size, which were submicroscopic CNVs and would likely not have been identified by conventional karyotyping.

Among the 21 CNVs, 18 (85.7%) in 17 cases were associated with 13 recurrent chromosomal microdeletion/ microduplication syndromes, including 3 microduplication and 10 microdeletion syndromes. Of the 3 microduplication syndromes, there were a 51.9 Mb duplication at 11q14.1q25 in a 6-month-1-day female (J180) diagnosed as 11q partial trisomy, a 13.1 Mb duplication at 16q11.2q21 in a 3-year-4-month female (J150) diagnosed as 16q partial trisomy, and a 2.177 Mb duplication at 17q23.1q23.2 in a 4-month-16-day girl (J128) diagnosed as 17q duplication syndrome (Table 2). The 10 microdeletion syndromes involved five classic A-D deletions at 22q11.2 in 2 boys (J131, J202) and 3 girls (J173, J194, J201) diagnosed as 22q11.2 deletion syndrome /DiGeorge syndrome, two deletions of 546 kb and 512 kb at 15q11.2 in one male (J106) and one female (J199) diagnosed as 15q11.2 microdeletion syndrome, a 1.4 Mb deletion at 7q11.23 in a 4-month-old boy (J003) diagnosed as Williams-Beuren syndrome, a 14.2 Mb deletion at 8q24.11q24.22 in a 1-month-12-day-old boy (J217) diagnosed as Langer-Giedion syndrome, a 51.9 Mb duplication at 11q14.1q25 in a 6-year-1-day-old girl (J180) diagnosed as 11q partial trisomy, a 27.7 Mb deletion at 13q14.2q22.1 in a 1-month-27-day-old boy (J144) diagnosed as Partial monosomy 13q with mosaic level at about 50%, a 3.256 Mb deletion at 13q34 in a 2-year-old boy (J109) diagnosed as 13q deletion syndrome, a 15.3 Mb deletion at 16p13.12p13.11 in a 6-month-12-day-old boy (J177) diagnosed as 16p13.11 microdeletion syndrome, a 13.1 Mb duplication at 16q11.2q21 in a 3-year-4-month-old girl (J150) diagnosed as 16q partial trisomy, a 3.53 Mb deletion at 17p11.2 in a 1-year-1-month boy (J179) diagnosed as Smith-Magenis syndrome, a 4.81 Mb deletion at 18p11.32p11.31 in a 1-year-5-month boy (J016) diagnosed as 18p deletion syndrome (Table 3; Fig. 2).

A mosaic deletion (1-2) at 13q14.2q22.1 identified by Illumina-CytoSNP-12 array.Illumina-CytoSNP-12 array analyses revealed a 3.256 Mb mosaic deletion (1-2) at 13q14.2q22.1 in the patient (J144) with VSD. The black arrow indicates the deletion. The red arrow indicates the deleted region on chromosome.

There were 2 cases who harbored more than one clinically relevant CNVs, of which a 2-month-7-day boy with perimembranous ventricular septal defect( J109), was identified with a 3.3 Mb de novo deletion at 13q34 and a 1.6 Mb paternally inherited duplication at 19p13.3; a 3-month-17-day boy with perimembranous ventricular septal defect and genitourinary malformation(J153) harboring a de novo deletion at 7p22.3, immediately adjacent to 2 de novo duplications at 7p22.3p22.2 and 7q33q36.3. The phenotypes of above cases were considered combined effects from the CNVs (Table 3, Table S2).

Incremental yield of WES

Apart from 21 individuals with pathogenic/likely pathogenic CNVs and aneuploidies, we obtained the sequencing data from 76 trio-based and 3 probands-only WES. Single nucleotide variations (SNVs) and small insertion and deletions (InDels) were detected based on comparison with the human reference sequence (hg19).

We identified 9 pathogenic/likely pathogenic variants in 8 genes from 8 CHD patients. Five of the variants have been previously reported in the literature, and 4 were novel, including 6 de novo, 1 paternally inherited and 2 compound heterozygous variants (Table 4). The 6 de novo variants consisted of 4 missense variants in 4 CHD genes, GATA6, TRAF7, KAT6A and RIT1, and two loss-of-function variants in KANSL1 and FLNA. We identified 2 compound heterozygous loss-of-function variants in PKD1L1 and 1 paternally inherited loss-of-function variant in SMAD6 (Table 4). The 4 novel variants were identified in FLNA (exon 8–9 duplication), KAT6A (c.2044 C > A) and PKD1L1 (c.5451 C > G, c.1071delT). The incremental yield of WES was 7.9% (8/101), resulting in a combined molecular diagnostic rate of 28.7% (29/101). Additionally, we found 7 potentially relevant variants which were classified as variants of uncertain significance (VUS) according to the ACMG guidelines (Table 4, Table S3). In our cohort, there were two siblings from one family, of which one patient (J001) was a 4-month-old boy with Conotruncal, TOF, inguinal hernia and umbilical hernia. His sister (J002) was 3 years old with perimembranous ventricular septal defect without extracardiac MCA. We compared their WES data side by side with their parents but did not find pathogenic /likely pathogenic genes associated with CHD (Table S4).

Discussion

We utilized chromosomal microarray analysis (CMA) and whole exome sequencing (WES) to investigate the prevalence of clinically relevant CNVs and SNVs/Indels in an unselected cohort of 101 CHD patients without clear etiology. we got a higher general prevalence of chromosomal abnormalities of 20.8% (21/101), which is consistent with a recent Chinese study that identified pathogenic/likely pathogenic CNVs in 24/104 (23.1%) CHD patients20confirming the important role for CMA in clinical settings. Among them, 26 individuals classified as non-isolated CHD when they had at least one extracardiac multiple congenital anomaly (MCA), such as craniofacial anomalies, neck anomalies, cleft palate, trachea and thorax abnormalities, hernia, genitourinary malformation and skeletal dysplasia as well as DD and ID. However, due to younger age, lack of certain clinical manifestations and inadequate clinical assessment, it is possible to classify the two groups of isolated and non-isolated patients inaccurately. For instance, Langer-Giedion syndrome is a rare chromosomal syndrome with deletions of the distal part of 8q24.1, characterized by distinct facial features, mental retardation, bone abnormalities and some patients suffering from CHD, which is hard to be recognized in childhood21. In our study, a 14.2 deletion at 8q24.11q24.22 was identified in a 1-month-12-day boy with complete atrioventricular septal defect, while no other phenotypes were noted when he was enrolled, so he was classified incorrectly into isolated CHD group.

We re-assessed retrospectively the clinical presentations of the patients with recognizable features of the identified genetic syndromes and compared with previously reported cases in the literature. For example, 22q11.2 deletions are among the most frequent genetic causes in individuals with CHD and present with a variety of clinical features. About 64% of individuals with 22q11.2 deletion syndrome have heart defects and > 90% are de novo22,23. Consistently, 5 cases in the study identified 22q11.2 deletion syndrome (DiGeorge syndrome) presented facial features (4/5), TOF/VSD (5/5), hypocalcemia (2/5), immunodeficiency (2/5), and DD (1/5) who were 4 de novo and 1 maternal inherited. Trisomy-21 (known as Down syndrome) is the most common chromosomal abnormality in CHD patients who usually have distinctive pattern of clinical features, such as global developmental delay, intellectual disability, characteristic face, microcephaly, and other physical traits so that it is generally do not require genetic testing for them to obtain a diagnosis and most studies investigating the yield of genetic testing in CHD patients exclude cases of trisomy-21 as these patients24. A 11-day-old boy with complete atrioventricular septal defect and mild craniofacial anomalies was identified as trisomy-21, but he was not recognizable before he was enrolled due to his young age and lack of distinctive features.

Interestingly, we detected 3 rare de novo CNVs at chromosome 7 in one 3-month-17-day-old boy with complex phenotypes of multiple systems such as perimembranous ventricular septal defect, agenesis of corpus callosum, scoliosis, hypotonia, microphallus, hypospadias, and DD. The 3 CNVs include a 1.8 Mb deletion at 7p22.3 encompassing 36 genes and a major OMIM gene of FAM20C (#611060). There are 6 individuals with overlapping deletions (from 1.12 Mb to 2.32 Mb) and a variety of phenotypes mainly including DD, ID, cognitive impairment and seizures in the DECIPHER database. The second CNVs, a 1.8 Mb duplication at 7p22.2 involving 19 genes has been associated with developmental delay, mild ID, asthma, myopia, dysmorphic features in the literature25. There are additional 21 cases with overlapping duplications (from 198.88 kb to 2.23 Mb) and a variety of phenotypes mainly including abnormal heart morphology, cerebellar vermis hypoplasia, renal hypoplasia, cognitive impairment, scoliosis, strabismus, and ID in the DECIPHER database. The third CNV is a 23.5 Mb duplication at 7q33q36.3 encompassing over 100 genes, overlapping reported however smaller microduplications of 507 kb, 730 kb and 1.35 Mb from 7q36.1 to 7q36.3. The 507 kb duplication at 7q36.3 was found in a 20w6d fetus with multiple congenital anomalies like cleft lip/palate, prominent cavum septum pellucidum, right-sided heart position, absent right radius and thumb, fixed right forearm, and scoliosis26; the 730 kb duplication at 7q36.3 was found in four individuals from a three-generation family with agenesis of the corpus callosum and mild ID, macrocephaly27; the 1.35 Mb duplication at 7q36.1q36.2 was found in a 22 month old child presenting with hypotonia, respiratory distress, feeding difficulties, cardiovascular malformation, growth failure with microcephaly, short stature, sensorineural hearing loss, myopia, cryptorchidism, hypospadias, microphallus, distinctive facial features and DD28. Furthermore, from the DECIPHER database additional 109 cases with duplications within 7q33q36.3 presented some overlapping manifestations, such as corpus callosum dysplasia, scoliosis, muscular hypotonia and microphallus, macrocephaly, cardiac defects, TOF, and ID. Likely, the 3 de novo CNVs could be a more complex structural rearrangement, such as a ring chromosome (often mosaic) which contribute to the phenotype of this individual, but more follow-up work is needed in the future.

Through WES, we identified ten pathogenic and likely pathogenic variants in 8 individuals, and most genes (including FLNA, KANSL1, TRAF7, KAT6A, PKD1L1, and RIT1) have previously been associated with syndromic CHD29,30,31,32,33,34. However, 4 genes of TRAF7, KAT6A, PKD1L1, and RIT1 were found in probands with isolated CHD. The main reason should also be clinically unrecognized associated features especially in young patients. Our findings provide further evidence supporting an important role of these genes in CHD. FLNA, located on chromosome Xq28, encodes an actin - binding protein (filamin A) expressed in virtually every tissue, and mutations in the FLNA gene cause X-linked filaminopathies including cardiovascular malformations, such as X-linked cardiac valvular dystrophy (CVDPX; OMIM#314400), X-linked periventricular nodular heterotopia (PVNH1; OMIM#300049), FG syndrome-2 (FGS2; OMIM#300321)35,36. We identified an exon 8–9 duplication in the FLNA gene in a 7-month- old boy (J102) presenting with perimembranous ventricular septal defect, trachea abnormality and umbilical hernia. He died at 10 months of respiratory insufficiency and heart failure. The intragene duplication was predicted to cause loss-of-function of the FLNA gene. Other individuals with loss-of-function variants in the FLNA gene presented with periventricular nodular heterotopia, heart defects, interstitial lung disease, respiratory failure, and/or early death, further indicating an association of FLNA deficiency and congenital malformations of the brain, heart and lungs37,38.

In this study, we performed sequential genetic testing using CMA followed by trio-WES in a cohort of unselected CHD patients in order to obtain reliable diagnostic yields. Our study indicates that trio-WES increments the diagnostic yield in patients with extracardiac features but also in those with apparently “isolated” CHD. It’s worthy noting that finding de novo pathogenic variants in genes with an uncertain link to CHD, does not prove this association but may contribute data to support this association. In addition, the sample size was small, and it is possible missing some dual diagnoses by only performing exome on the patients with negative CMAs, further studies with large samples and using genome sequencing are warranted to find new genes and variants, and to assess the clinical spectrum and recurrence risks in affected individuals and their families.

Methods

Subjects

The study was approved by Ethics Committee of Jinan Children’s Hospital (Children’s Hospital Affiliated to Shandong University). Informed written consent was obtained from the patients’ parents. The personal privacy information of the patients’ and their families was anonymized prior to genotyping and analysis. All the procedures performed in the study were in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

A total of 101 unrelated children with congenital heart disease (CHD) (male: 57, female: 44, mean age: 9 months, range from 1 day to 9 years old) and their unaffected parents were enrolled in the study between March 2015 and December 2017. Among them, 2 patients were not biologically to father and 1 patient was not biologically related to both parents. All subjects were Han Chinese population in Shandong province and recruited from the department of cardiac surgery in Jinan Children’s Hospital (Children’s Hospital Affiliated to Shandong University) before they were hospitalized for surgery. The 101 patients were diagnosed by experienced pediatricians and pediatric cardiologists based on medical history, physical examination, echocardiogram and/or thoracic computed tomography angiography, and subsequently confirmed by cardiac surgery. Extracardiac multiple congenital anomalies (MCA) included craniofacial anomalies, neck anomalies, cleft palate, trachea and thorax abnormalities, hernia, genitourinary malformation and skeletal dysplasia were examined and diagnosed by multi-specialty pediatricians. Developmental delay (DD) and intellectual disability (ID) were tested and diagnosed by experienced pediatric neurologists. The patients’ parents stated that they had no medical and family history of CHD, though they did not have echocardiogram at hospital, except for one 4-monthe-old boy with tetralogy of Fallot (TOF), inguinal and umbilical hernia, and his 3-year-old sister with ventricular septal defect (VSD).

Chromosomal microarray analysis

Peripheral blood samples were obtained from all subjects. Genomic DNA was extracted using a TIANGEN Blood DNA Mini Kit (TIANGEN, BEIJING, China). Two CMA platforms of Affymetrix CytoScan HD Arrays (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA) and Illumina HumanCytoSNP-12 array (Illumina, San Diego, CA) were applied for detection of CNVs. Among them, 58 samples were first tested by Affy-HD array and then 43 samples were done by Illumina-CytoSNP-12 array when this platform with lower cost was available in our lab and no significant difference for CNVs detection. Genomic DNA was digested, amplified, and hybridized to the arrays following the protocols of Affymetrix or Illumina. The arrays were scanned on Cytoscan or iSan System, respectively.

Primary data were analyzed with Affymetrix Chromosome Analysis Suite (ChAS) or Illumina GenomeStudio software. The reporting threshold was set at 50 kb (markers ≥ 20) for deletions and 100 kb (markers ≥ 50) for duplications. Secondary analysis was performed and 1679 Chinese subjects from multiple sources were compared according to Liu et al.39. Frequency of prioritized CNVs was computed against the aforementioned controls in Liu et al.39. CNVs with > 50% reciprocal overlap were deemed identical40,41. All CNVs were classified as pathogenic, likely pathogenic, variants of uncertain significance (VUS), likely benign, and benign according to the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics guidelines42,43.

Whole exome sequencing and data analysis

To further assess the causal role of sequence variants, trio-based whole exome sequencing with xGen Exome Hyb Panel (IDT, USA) on the Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform was applied for the patients and their parents. In brief, genomic DNA was extracted using same kit as descripted above. A total of 1.5 µg genomic DNA was used to shear by KAPA Frag Enzyme (KAPA Inc, MA, USA) to generate average size of 300 bp libraries and then purified using Agencourt AMPure XP kit (Beckman Coulter Inc, CA, USA). After ligation with the paired-end adaptor and enriched by PCR, the DNA samples were hybridized with xGen Exome Hyb Panel and the targeted molecules were captured using Dynabeads MyOne Streptavidin T1 (Life Technologies, CA, USA), and then sequenced on an Illumina NovaSeq 6000 (Illumina Inc, CA, USA). Enrichment, sequencing kits and sequencing system were supplied by Illumina Inc (Illumina Inc, CA, USA).

Preliminary data analysis included read alignment, variant calling, and annotation. After quality control of raw reads with low quality sequences (quality score < 20) removed, sequencing reads were aligned to the human reference genome (GRCh37/hg19) using Sentieon (Sentieon Inc, Shanghai) and the Burrows-Wheeler Aligner44,45. Variant calling and annotation were performed according to the Broad Institute’s GATK (v4.0) and Annovar. The median coverage was 100 X with 98% of the target bases being covered ≥ 10 X. Variants were filtered out when their minor allele frequency > 0.5% in public databases including 1000 Genomes Project (https://www.internationalgenome.org/) and gnomAD (https://gnomad.broadinstitute.org). ClinVar (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar) and the Human Gene Mutation Database (http://www.hgmd.cf.ac.uk) were used to search for previously reported variant-disease associations. In silico analysis of the variants was carried out using PolyPhen-2, SIFT and Mutation Taster to predict potentially disrupted protein function. The variants identified using this procedure were classified according to the 2015 American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) guidelines46.

Validation of gene variants

Real-time qPCR with SYBR Green chemistry were utilized to verify potentially clinical relevant CNVs in cases and their parents, as described before47. Sanger sequencing was used to validate pathogenic and likely pathogenic variants identified by whole exome sequencing. Sanger validation primer sets were designed using Primer Premier v5.0 software. PCR amplification was performed with AmpliTaq Gold® 360 DNA Polymerase (Applied Biosystems). PCR products were further purified and sequenced using an ABI Prism 3700 automated sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS 26 software. Chi-square test or two-sided Fisher’s test was used to compare the positive rates of between Isolated and non-isolated CHD as well as the three CHD subgroups. A difference was considered statistically significant when the p value was less than 0.05 and the confidence interval was 95%.

Data availability

The datasets generated during the current study are available in the repository (GSA-Human with accession number: HRA009732) [https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/gsa-human].

References

GBD 2017 Congenital Heart Disease Collaborators. Global, regional, and National burden of congenital heart disease, 1990–2017: A systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2017. Lancet Child. Adolesc. Health. 4, 185–200 (2020).

Pierpont, M. E. et al. Genetic basis for congenital heart disease: revisited: A scientific statement from the American heart association. Circulation 138, e653–e711 (2018).

Liu, Y. et al. Global birth prevalence of congenital heart defects 1970–2017: updated systematic review and meta-analysis of 260 studies. Int. J. Epidemiol. 48 (2), 455–463 (2019).

Lucron, H. et al. Infant congenital heart disease prevalence and mortality in French guiana: a population-based study. Lancet Reg. Health Am. 29, 100649 (2023).

Russell, M. W. et al. Advances in the Understanding of the genetic determinants of congenital heart disease and their impact on clinical outcomes. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 7 (6), e006906 (2018).

Diab, N. S. et al. Molecular genetics and complex inheritance of congenital heart disease. Genes (Basel). 12 (7), 1020 (2021).

Geddes, G. C. et al. Variants of significance: medical genetics and surgical outcomes in congenital heart disease. Curr. Opin. Pediatr. 32 (6), 730–738 (2020).

Jerves, T. et al. The genetic workup for structural congenital heart disease. Am. J. Med. Genet. C Semin. Med. Genet. 184, 178–186 (2020).

Nees, S. N. & Chung, W. K. The genetics of isolated congenital heart disease. Am. J. Med. Genet. C Semin. Med. Genet. 184 (1), 97–106 (2020).

Joynt, A. C. M. et al. Understanding genetic variants of uncertain significance. Paediatr. Child. Health. 27 (1), 10–11 (2022).

Choi, B. G. et al. Array comparative genomic hybridization as the first-line investigation for neonates with congenital heart disease: experience in a single tertiary center. Korean Circ. J. 48, 2019 – 216 (2018).

Saacks, N. A. et al. Investigation of copy number variation in South African patients with congenital heart defects. Circ. Genom. Precis. Med. 15 (6), e003510 (2022).

Westphal, D. S. et al. Lessons from exome sequencing in prenatally diagnosed heart defects: A basis for prenatal testing. Clin. Genet. 95, 285 – 289 (2019).

Shabana, N. A., Shahid, S. U. & Irfan, U. Genetic contribution to congenital heart disease (CHD). Pediatr. Cardiol. 41 (1), 12–23 (2020).

Nattel, S. N. et al. Congenital heart disease and neurodevelopment: clinical manifestations, genetics, mechanisms, and implications. Can. J. Cardiol. 33, 1543–1555 (2017).

Homsy, J. et al. De Novo mutations in congenital heart disease with neurodevelopmental and other congenital anomalies. Science 350, 1262–1266 (2015).

Uke, P. et al. Neurodevelopmental assessment of children with congenital heart diseases using Trivandrum developmental screening chart. J. Neurosci. Rural Pract. 14 (4), 692–697 (2023).

Reuter, M. S. et al. The cardiac genome clinic: implementing genome sequencing in pediatric heart disease. Genet. Med. 22 (6), 1015–1024 (2020).

Botto, L. D. et al. Seeking causes: classifying and evaluating congenital heart defects in etiologic studies. Birth Defects Res. Clin. Mol. Teratol. 79 (10), 714–727 (2007).

Li, P. et al. Copy number variant analysis for syndromic congenital heart disease in the Chinese population. Hum. Genom. 16 (1), 51 (2022).

Chen, C. P. et al. An interstitial deletion of 8q23.3-q24.22 associated with Langer-Giedion syndrome, Cornelia de Lange syndrome and epilepsy. Gene 529, 176–180 (2013).

Ma, Y. et al. Chromosome microarray analysis of 3 patients with different phenotypes of digeorge syndrome. Chin. J. Appl. Clin. Pediatr. 33, 620–622 (2018).

McDonald-McGinn, D. M. et al. 22q11.2 Deletion Syndrome. In: Adam MP, Feldman J, Mirzaa GM, et al. GeneReviews®. University of Washington, 2024. (1993).

Nees, S. N. & Chung, W. K. Genetic basis of human congenital heart disease. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 12 (9), a036749 (2020).

Cox, D. M. & Butler, M. G. A case of the 7p22.2 microduplication: refinement of the critical chromosome region for 7p22 duplication syndrome. J. Pediatr. Genet. 4 (1), 34–37 (2015).

Micale, M. et al. Prenatal identification of two discontinuous maternally inherited chromosome 7q36.3 microduplications totaling 507 kb in cluding the Sonic Hedgehog gene in a fetus with multiple congenital anomalies. Clin. Case Rep. 5 (6), 993–999 (2017).

Wong, K. et al. A Familial 7q36.3 duplication associated with agenesis of the corpus callosum. Am. J. Med. Genet. A. 167A (9), 2201–2208 (2015).

Al Dhaibani, M. A. et al. De Novo chromosome 7q36.1q36.2 triplication in a child with developmental delay, growth failure, distinctive facial features, and multiple congenital anomalies: a case report. BMC Med. Genet. 18 (1), 118 (2017).

Wade, E. M. et al. The X-linked filaminopathies: synergistic insights from clinical and molecular analysis. Hum. Mutat. 41 (5), 865–883 (2020).

Koolen, D. A. et al. Koolen-de Vries Syndrome. University of Washington, Seattle. 1993–2024 (2010).

Castilla-Vallmanya, L. et al. Phenotypic spectrum and transcriptomic profile associated with germline variants in TRAF7. Genet. Med. 22 (7), 1215–1226 (2020).

Kennedy, J. et al. KAT6A syndrome: genotype-phenotype correlation in 76 patients with pathogenic KAT6A variants. Genet. Med. 21, 850–860 (2019).

Vetrini, F. et al. Bi-allelic mutations in PKD1L1 are associated with laterality defects in humans. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 99, 886–893 (2016).

Calcagni, G. et al. Congenital heart defects in Noonan syndrome and RIT1 mutation. Genet. Med. 18, 1320 (2016).

Masurel-Paulet, A. et al. Lung disease associated with periventricular nodular heterotopia and an FLNA mutation. Eur. J. Med. Genet. 54 (1), 25–28 (2011).

Sasaki, E. et al. A review of filamin A mutations and associated interstitial lung disease. Eur. J. Pediat. 178, 121–129 (2019).

Oegema, R. et al. Novel no-stop FLNA mutation causes multi-organ involvement in males. Am. J. Med. Genet. A. 161A (9), 2376–2384 (2013).

Calcaterra, V. et al. A case report on filamin A gene mutation and progressive pulmonary disease in an infant: A lung tissued derived mesenchymal stem cell study. Med. (Baltim). 97 (50), e13033 (2018).

Liu, Y. et al. Chromosomal microarray analysis of 410 Han Chinese patients with autism spectrum disorder or unexplained intellectual disability and developmental delay. NPJ Genom. Med. 7 (1), 1 (2022).

Zarrei, M. et al. A copy number variation map of the human genome. Nat. Rev. Genet. 16, 172–183 (2015).

MacDonald, J. R. et al. The database of genomic variants: a curated collection of structural variation in the human genome. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, D986–992 (2014).

South, S. T. et al. ACMG standards and guidelines for constitutional cytogenomic microarray analysis, including postnatal and prenatal applications: revision 2013. Genet. Med. 15, 901–909 (2013).

Riggs, E. R. et al. Technical standards for the interpretation and reporting of constitutional copy-number variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American college of medical genetics and genomics (ACMG) and the clinical genome resource (ClinGen). Genet. Med. 22 (2), 245–257 (2020).

Kent, W. J. et al. Exploring relationships and mining data with the UCSC gene sorter. Genome Res. 15, 737–741 (2005).

Raney, B. J. et al. Track data hubs enable visualization of user-defined genome-wide annotations on the UCSC genome browser. Bioinformatics 30, 1003–1005 (2014).

Richards, S. et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American college of medical genetics and genomics and the association for molecular pathology. Genet. Med. 17, 405–424 (2015).

Liu, Y. et al. De Novo exon 1 deletion of AUTS2 gene in a patient with autism spectrum disorder and developmental delay: a case report and a brief literature review. Am. J. Med. Genet. A. 167 (6), 1381–1385 (2015).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the patients and their parents for their contribution to the work. The authors also express their gratitude to the Fujun Genetics Company for data analysis and technical support of WES. We would like to thank The Centre for Applied Genomics at the Hospital for Sick Children and the University of Toronto McLaughlin Centre. S.W.S. holds the Northbridge Chair in Paediatric Research at the Hospital for Sick Children and University of Toronto.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

This study was conceived and designed by YL and SWS. The experiments were conducted by GZ, XY, HZ and YW. Data analyzed by RG, CD, MZ, MR, RD, SWS and YL. RG, CD and ZG contributed to the clinical diagnosis of the patients. The paper was written by YL and revised by MZ, MR and SWS. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

S.W.S. is on the Scientific Advisory Committees of Deep Genomics, and is a Highly Cited Academic Advisor for the King Abdulaziz University. The other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Guo, R., Duan, C., Zarrei, M. et al. Genetic findings of children with congenital heart diseases using chromosomal microarray and trio-based whole exome sequencing. Sci Rep 15, 27312 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-06977-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-06977-9