Abstract

Blood pressure (BP) serves as a fundamental indicator of cardiovascular health, measuring the force exerted by circulating blood against arterial walls during each heartbeat. This paper introduces an advanced deep learning framework for precise, non-invasive BP estimation via photoplethysmography (PPG) signals, addressing critical limitations in traditional, cuff-based BP measurement methods. Traditional methods, while reliable, are limited by their inability to provide continuous data, posing challenges for proactive health management. In contrast, PPG-based BP estimation facilitates continuous monitoring, crucial for wearable health technologies and real-time applications. Our proposed model leverages a hybrid architecture of convolutional neural networks (CNNs), bidirectional long short-term memory (BiLSTM) layers, and an attention mechanism, enabling refined spatial and temporal feature extraction to enhance BP estimation accuracy. This approach is validated on an extensive dataset of 2064 patients from the MIMIC-II database, marking a significant increase in sample size over prior studies and thereby strengthening model robustness and generalizability. Through meticulous preprocessing steps, the model achieved an impressive mean absolute error (MAE) of 1.88 for systolic blood pressure (SBP) and 1.34 for diastolic blood pressure (DBP) across 5-fold cross-validation. These findings underscore the potential of integrating PPG and deep learning as a viable, scalable solution for wearable BP monitoring, providing a foundation for further advancement in accessible, non-invasive cardiovascular health monitoring technologies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

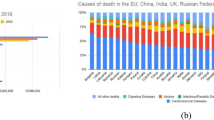

Despite remarkable advancements in modern medicine, cardiovascular disease (CVD) continues to be one of the leading causes of death worldwide, especially among the elderly1,2. This persistent health challenge not only affects millions but also leaves a profound mark on the body’s vital systems2. Among its most significant impacts is the alteration of arterial blood pressure (ABP) waveforms3,4, which serve as mirrors to the heart’s performance and the overall health of the cardiovascular system.

These waveforms are intricately connected to several crucial physiological parameters such as systolic blood pressure (SBP) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP), making them invaluable in the diagnosis and management of heart-related conditions5. SBP and DBP5,6, which reflect the pressure in the arteries during and between heartbeats, respectively, provide vital insights into an individual’s cardiovascular health6. By analyzing these indicators, healthcare professionals can assess the functioning of the heart and blood vessels, detect potential risks, and make informed decisions about treatment strategies.

Current non-invasive methods for measuring blood pressure (BP), such as cuff-based techniques using mercury or electronic sphygmomanometers7,8, provide accurate readings but are restricted to discrete measurement periods9. These methods require manual operation, preventing continuous monitoring, which is crucial for identifying fluctuations and trends in BP over time. Additionally, many patients remain unaware of elevated BP levels unless they measure it actively, potentially delaying diagnosis and treatment10. Furthermore, the repeated inflation of cuffs during measurements can cause discomfort, limiting their practicality for frequent or long-term use10.

To address these limitations, advancements in sensor technology have introduced photoplethysmography (PPG) as a promising alternative for non-invasive BP measurement11,12. PPG operates by using low-intensity infrared light, which penetrates the skin to detect changes in blood volume. As the heart pumps blood, the volume of blood in the microvascular tissue fluctuates, leading to corresponding changes in the intensity of light absorbed by the tisse13. By capturing these variations, PPG provides valuable insights into cardiovascular dynamics that are proportional to BP changes13,14,15.

PPG facilitates continuous and comfortable BP monitoring, making it ideally suited for wearable devices and long-term use13. Moreover, when combined with advanced signal processing techniques and deep learning models, PPG can enhance the accuracy of non-invasive BP estimation, further expanding its potential in modern healthcare such as the works that have been done in16,17,18,19.

Another promising approach in non-invasive BP estimation is pulse wave velocity (PWV), which represents the speed at which BP waves propagate through blood vessels and is closely associated with both blood volume and BP values20. PWV can be determined by calculating the pulse transmission time between two fixed measurement points. In this context, features such as pulse transit time (PTT)21 and pulse arrival time (PAT)11 can also be extracted and utilized to improve BP estimation accuracy22,23,24,25.

However, the accurate measurement of these parameters often requires combining PPG signals with other physiological signals, such as electrocardiogram (ECG) data or additional PPG signals captured from different body locations26. This multi-signal requirement introduces complexity and limits the practicality and scope of non-invasive BP monitoring in everyday applications, particularly for wearable devices or continuous monitoring systems.

Recent research, however, has demonstrated the potential for estimating BP using single-channel PPG signals alone27,28,29,30. Since both ABP and PPG signals originate from the same heart excitation, it is reasonable to expect a correlation between them in both the time and frequency domains31. Specifically, Martínez et al.31 support this stance by demonstrating a strong, statistically significant similarity between ABP and PPG waveforms. Their analysis reveals high correlation coefficients (often above 0.9) when comparing the morphologies of both signals in time and frequency domains. Because PPG is non-invasive, more comfortable, and still captures the essential hemodynamic information found in invasive ABP signals, Martínez and colleagues conclude that single-channel PPG can feasibly serve as a less intrusive alternative to traditional ABP monitoring for continuous blood pressure estimation.

This shift toward using single-channel PPG signals opens the door for simplified, more practical solutions for BP monitoring, reducing the dependency on complex multi-sensor setups while maintaining reliable accuracy.

Existing BP estimation methods based on PPG signals can generally be classified into two main approaches. The first approach involves extracting relevant features from the PPG signals and mapping these features to BP values using regression algorithms or neural networks32,33,34,35,36. The second approach utilizes deep learning techniques to map raw PPG signals directly to BP values in an end-to-end manner. In the latter case, the PPG signals are typically preprocessed—denoised and normalized—to simplify the mapping process and improve accuracy16,26,37,38.

For the feature extraction-based methods, both the original PPG signals and their derivative signals (such as the first and second derivatives) are sometimes considered. Early work by Duan et al.35 explored the use of PPG signals for BP estimation by evaluating 57 potential features. From these, they proposed three distinct feature sets, each containing 11 features specifically for estimating SBP, DBP, and mean arterial pressure (MAP). Building on this, Xie et al.32 refined these feature sets and ultimately recommended eight key features that could reliably estimate BP values using traditional machine learning algorithms.

In addition, Lin et al.39 found that derivative signals, such as the velocity photoplethysmogram (VPG) and the acceleration photoplethysmogram (APG), provided stronger correlations with BP values compared to the original PPG signals alone. By incorporating these derivative features, they were able to achieve more accurate BP estimations using multiple regression algorithms compared to PWV based methods under similar conditions. This indicates that both VPG and APG signals contain valuable information relevant to BP estimation. Moreover, Wang et al.40 utilized time-domain and frequency-domain features from the PPG, VPG, and APG signals to classify five common BP-related conditions. They applied convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and long short-term memory (LSTM) networks, demonstrating that feature extraction from all three signals could improve classification accuracy.

While feature extraction methods using PPG, VPG, and APG signals have shown promising results, they still require carefully designed and selected features to achieve optimal BP estimation accuracy. This feature engineering process can be labor-intensive and may limit the scalability of these methods.

In contrast, end-to-end BP estimation methods aim to bypass manual feature extraction by using preprocessed PPG signals as direct inputs to neural networks. Through deep learning, the relationship between PPG signals and BP values can be automatically learned by training the models with large datasets. For example, Baek et al.26 used both time-domain and frequency-domain representations of PPG and ECG signals as input to a CNN architecture, successfully estimating SBP and DBP values.

Wang et al.37 developed a model combining CNN and recurrent neural networks (RNNs) to estimate BP values from individual PPG beats. Although this approach eliminated the need for manual feature selection, it required the segmentation of PPG signals into smaller parts, such as heartbeats, to feed into the model. Additionally, Panwar et al.16 proposed an end-to-end model called PP-Net, which estimates both BP and heart rate from PPG signals using a combination of CNN and LSTM networks.

Ibtehaz et al.17 introduced a two-stage deep learning model named PPG2ABP. This model employs a cascaded approach to first approximate and then refine the BP values derived from PPG signals. They reported that their method achieved high accuracy in estimating SBP and DBP, surpassing many existing techniques by eliminating the need for handcrafted features or additional signals like ECG. Cheng et al.18 further demonstrated that their deep learning approach could achieve even more accurate predictions of SBP and DBP from PPG signals, contributing to the advancement of non-invasive BP estimation methods.

Tang et al.19 proposed a W-Net architecture that effectively estimates ABP from PPG signals, bypassing the need for manual feature extraction. This deep learning model comprises two concatenated U-Net structures, designed to capture both local and global features. Their results demonstrated high pearson correlation values and low root mean square errors (RMSEs) between the estimated and reference ABP values, indicating the model’s ability to provide highly accurate BP estimations.

Overall, while feature extraction-based methods rely on careful selection and design of input features, end-to-end deep learning approaches automatically learn the mapping from raw PPG signals to BP values, offering greater flexibility and potential scalability. However, the effectiveness of both approaches depends on the quality of the input data and the complexity of the models employed.

In this study, we focused on enhancing BP estimation accuracy from PPG signals by implementing advanced preprocessing steps and experimenting with several model architectures and hyperparameters. After extensive evaluation, we developed a model architecture comprising three CNN layers, two bidirectional long short-term memory (BiLSTM) layers, and an attention layer.

Compared to prior research efforts, our proposed approach offers several distinct advantages that enhance both the accuracy and practicality of non-invasive BP estimation:

-

Larger sample size: Utilizing data from 2064 patients—substantially more than prior studies16,17,18,19,26,37—improves the model’s generalizability and robustness.

-

Reduced system complexity and enhanced usability in wearable devices: By relying solely on PPG signals, this study eliminates the need for multiple signal sources such as ECG26, simplifying the system design and improving its feasibility for wearable devices and continuous monitoring systems.

-

Advanced architecture: Integrating CNN, BiLSTM, and attention layers—an architecture combination not previously explored in similar research—enables the effective capture of complex features and temporal patterns within PPG signals, enhancing the model’s ability to track BP fluctuations.

-

Improved accuracy: Superior performance in 5-fold cross-validation demonstrates the model’s high reliability and accuracy in BP estimation.

These advancements highlight the efficiency and precision of our proposed method for BP estimation from PPG signals, representing a significant contribution to the field of non-invasive BP monitoring.

The structure of this article is as follows: Sect. 2 provides a thorough and detailed overview of the methodology used in this study, outlining each step of the approach in depth. Sec. 3 then presents the experimental results, analyzing the performance of the proposed model and highlighting key findings. Finally, Sect. 4 concludes the article by summarizing the main insights, discussing the implications of the results, and suggesting potential directions for future research.

Materials and methods

This section provides an overview of the steps used for BP estimation using PPG signals, including the data used, the signal preprocessing stages, the extraction of systolic and diastolic points from ABP signals, and the training and evaluation of the deep networks employed. Figure 1 illustrates the steps of our method. After the signal preprocessing process, we extracted the systolic and diastolic points present in the segmented ABP signals to use their averages as the target for the networks. Finally, the networks were trained and evaluated using a 5-fold cross-validation approach, which enhances the robustness and generalizability of our networks. In this method, the dataset was divided into five equal parts. During each iteration, one distinct part was used for testing, while the remaining four parts were used for training. This process was repeated five times, ensuring that each part was used exactly once for testing. The final results were then averaged to provide a comprehensive evaluation. Importantly, for each iteration, the model was trained from scratch to ensure that the training process was unbiased and independent of the previous iterations.

Detailed database description

In this study, we utilize a subset of the multiparameter intelligent monitoring in intensive care II (MIMIC-II) dataset41,42, which is publicly available through the University of California Irvine (UCI) machine learning repository43. This dataset, compiled by Kachuee et al.22,44, contains physiological recordings of patients in the intensive care unit (ICU). It includes synchronously recorded PPG, ABP, and ECG signals from a total of 12,000 patients.

All signals within the dataset are sampled at a frequency of 125 Hz with 8-bit digital precision, providing a high-resolution dataset for model training and evaluation42. The focus of our study, however, is on the PPG and ABP signals, which are used to estimate BP.

The dataset has been pre-processed according to the methodology of Kachuee et al.44, making it more accessible for further analysis and ensuring that the signals are in a suitable format for training deep learning models. This pre-processing step includes noise reduction and the removal of irrelevant or unreliable signal segments, making the dataset well-suited for non-invasive BP estimation tasks.

Signal preprocessing techniques

In this study, several preprocessing techniques were applied to ensure the quality and consistency of the signals used for BP estimation. The goal of these techniques is to remove noise, irrelevant data, and signals that do not meet the required standards, ensuring that only high-quality data is used for training the deep learning models. Figure 2 illustrates the steps involved in the preprocessing pipeline, which transforms the raw PPG and ABP signals into high-quality data suitable for model training.

Detrending

In the detrending step of preprocessing, the goal is to remove baseline trends and slow changes from the PPG signal45 that could interfere with the extraction of key physiological features. A linear regression model is applied to the PPG signal to fit a baseline trend line. This trend line is then subtracted from the original signal, leaving behind the detrended signal. The resulting signal is free from low-frequency noise and is better suited for further processing steps. Figure 3 illustrates the original and detrended PPG signals over the course of one second, showcasing how the detrending process removes baseline shifts while preserving the key physiological features.

Removing records with ABP > 200 mmhg

All records where the maximum ABP exceeds 200 mmHg were removed from the dataset. This step prevents the inclusion of extreme or outlier data points that could negatively influence the model’s training.

Removing records with duration < 8 min

Referring to the previous work16, we removed all records where the duration was less than 8 min. This ensures that the dataset includes only segments of signals long enough to capture meaningful physiological patterns. As a result, the number of subjects decreased from 12,000 to 2064, allowing for more consistent and reliable data for model training and evaluation.

Segmentation

After applying the initial filters, data segmentation is performed using an 8.192-second window with 75% overlap, following the approach of38. This windowing technique has been proven effective in capturing information related to heart cycles46,47,48,49, ensuring that the deep learning models can extract relevant features for BP estimation. The overlapping windows provide a more continuous analysis of the signals, further enhancing the model’s ability to capture variations in physiological patterns. Figures 4 presents a sample of simultaneous PPG and ABP signals extracted from the database over an 8.192-second interval.

Systolic and diastolic peak detection

We decided to modify our target for training and evaluating the deep networks by extracting the systolic and diastolic points from the ABP signals in each 8.192-second window, rather than using the entire ABP signal as the target. The mean of the systolic points over the 8.192-second interval was used as the target for the corresponding 8.192-second PPG input, and similarly, the mean of the diastolic points was defined as another target for the same PPG input. Thus, our targets consist of single values for systolic and diastolic pressure. Figure 5 shows an example of an ABP signal over 8.192 s with the extracted systolic and diastolic points highlighted.

Train and test split

For evaluating our deep networks, we employ a 5-fold cross-validation approach50. This technique involves partitioning the entire dataset into five equal subsets. Prior to splitting, we applied shuffling to the dataset to ensure that the samples are randomly distributed among the folds. This step helps prevent any potential bias arising from the original ordering of the data, especially in large datasets, and leads to a more reliable evaluation. In each of the five iterations, a different subset is designated as the test set, while the remaining four subsets are combined to form the training set. This process is repeated five times, with each of the subsets used exactly once as the test set. This method provides a thorough assessment of the model’s performance. Figure 6 provides an overview to visualize this process.

Deep learning model

In this study, we present a sophisticated architecture that combines CNNs, BiLSTM networks, and an attention mechanism for BP estimation using PPG signals. This approach leverages the unique strengths of CNNs for feature extraction, BiLSTM for sequential data processing, and attention mechanism for focusing on the most relevant temporal segments of the input signal. The combination of these techniques has been inspired by their successful application in various deep learning tasks, such as speech recognition, natural language processing, and medical signal analysis.

CNN layer for feature extraction

The process begins with a CNN, designed to extract fundamental features from the PPG signals. CNNs are particularly effective in capturing local patterns in time-series data due to their ability to apply convolutional filters across the signal. Each filter learns to detect specific characteristics of the signal, allowing the model to automatically detect patterns relevant to BP estimation. In our CNN layers, we employed the ReLU activation function (Rectified Linear Unit) after each convolution operation. ReLU introduces non-linearity into the model, mitigates the vanishing gradient problem, and accelerates the convergence during training. Although we experimented with other activation functions such as sigmoid and tanh, ReLU yielded superior performance in terms of training stability and model accuracy.

The CNN layer produces a series of feature maps representing the most pertinent aspects of the input PPG signals51,52,53,53. Mathematically, for an input signal x, a 1D convolution operation can be expressed as:

Where \({w_i}\) are the learned weights of the filter, k is the filter size, b is the bias term, and σ is a non-linear activation function such as ReLU. The result is a feature map that highlights patterns essential for the next stages of the network.

BiLSTM layer for Temporal dependency capture

After feature extraction, the processed data is fed into a BiLSTM network. BiLSTM networks are particularly well-suited for capturing long-term dependencies in sequential data and mitigating the vanishing gradient problem that often affects traditional RNNs. Unlike unidirectional LSTM networks, BiLSTM models consist of two LSTM layers running in parallel: one processes the input sequence in the forward direction, and the other in the backward direction. This dual processing enables the model to simultaneously incorporate both past and future context at each time step, making it especially effective for time-series tasks like BP estimation54,55.

In this study, two BiLSTM layers are employed. The output of the first BiLSTM layer, with dimensionality doubled due to its bidirectional nature, serves as the input to the second BiLSTM layer. This hierarchical structure allows for deeper temporal feature representation and enhances the model’s ability to learn complex sequential dependencies.

Detailed illustrations of the BiLSTM architecture and the internal operations of each LSTM cell—including the input, forget, and output gates—are provided in the Supplementary Material. These details help clarify how information is selectively retained or discarded over time through gating mechanisms within the LSTM units. The BiLSTM mechanism ultimately ensures that both past and future temporal information are effectively utilized to improve the accuracy of BP estimation.

Attention mechanism for focused prediction

The output of the BiLSTM layer is passed to an attention mechanism56,57, which assigns weights to different time steps of the input sequence, enabling the model to focus on the most critical segments of the PPG signal. This is particularly important in medical signals like PPG, where certain portions of the signal may contain more relevant information for BP estimation.

The attention mechanism computes a score \({e_t}\) for each time step t by comparing the BiLSTM hidden states \({h_t}\)with a context vector v (learned during training):

The attention weights \({\alpha _t}\) are obtained by applying the softmax function to the scores:

The final context vectorc is then computed as a weighted sum of the BiLSTM hidden states:

This context vector is used to produce the final BP estimation, focusing on the most relevant parts of the input signal.

Experimental architectures

In addition to the final architecture consisting of three CNN layers, two BiLSTM layers, and one attention layer, which yielded promising results, we experimented with different network configurations, and their results are reported in the following sections. These configurations include:

-

1.

A single CNN layer combined with one BiLSTM layer and an attention layer.

-

2.

Two CNN layers combined with one BiLSTM layer and an attention layer.

-

3.

Two CNN layers combined with two BiLSTM layers and an attention layer.

This integrative approach, consisting of three CNN layers, two BiLSTM layers, and one attention layer, provides a robust framework for improving BP estimation accuracy from PPG signals by effectively extracting spatial and temporal features, while dynamically focusing on the most informative parts of the signal. All deep learning models were implemented in PyTorch, and their training and evaluation were conducted on an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3090.

Figure 7 summarizes the overall structure of this deep learning model, illustrating how the CNN layers, BiLSTM layers, and the attention mechanism are combined for accurate SBP and DBP estimation.

Evaluation criteria for model performance

To assess the effectiveness and accuracy of our model in estimating BP, we employed two regression metrics: Mean Squared Error (MSE), and Mean Absolute Error (MAE)58. Each metric provides unique insights into the model’s performance and error characteristics, allowing us to evaluate how well the model generalizes to new data and how precisely it predicts SBP and DBP values.

MSE quantifies the average squared differences between the model’s predicted values and the actual observed values. Squaring the errors penalizes larger errors more heavily than smaller ones, making MSE highly sensitive to outliers. This is useful when we want to emphasize larger deviations from the target value, which can be crucial in clinical settings where significant mispredictions of BP could have serious consequences. Mathematically, MSE for SBP and DBP is defined as follows:

Where n is the number of samples, \(SB{P_{act}}\left( i \right)\)and \(DB{P_{act}}\left( i \right)\) represent the actual values of SBP and DBP for the i -th sample, and \(SB{P_{per}}\left( i \right)\) and \(DB{P_{per}}\left( i \right)\) are the predicted values of SBP and DBP for the i -th sample. A lower MSE indicates better model performance, as it signifies smaller average squared errors.

Unlike MSE, MAE measures the average absolute difference between predicted and actual values without squaring the error term. This means each error contributes to the total proportionately, making MAE less sensitive to outliers than MSE. MAE thus provides a more balanced view of overall model accuracy. The formula for MAE is:

In applications like BP estimation, MAE provides insight into the average prediction error, offering a straightforward measure of accuracy that reflects typical deviations between the predicted and actual BP values.

By analyzing MSE and MAE collectively, we gain a comprehensive understanding of the model’s predictive power. Low values in all two metrics suggest the model is both accurate (small average error) and consistent (low variance in errors). These metrics collectively help in assessing the model’s generalizability, reliability, and overall effectiveness in clinical BP estimation, where accurate predictions are crucial for patient monitoring and intervention.

Results and discussion

This section presents a detailed evaluation of the performance of the deep learning models used in this study. All essential preprocessing steps and data preparation stages for the models were meticulously executed. The models were trained and evaluated using 5-fold cross-validation, with 20% of the data reserved for testing and 80% for training, of which 10% was further allocated for validation. Table 1 summarizes the average results across the 5 folds for the tested architectures, reported separately for SBP and DBP.

As shown in Table 1, the best results for SBP and DBP estimation were achieved using an architecture comprising three CNN layers, two BiLSTM layers, and one attention layer. The fold-specific results for SBP and DBP in this architecture are reported in Tables 2 and 3.

To evaluate the performance of the proposed network in each of the five cross-validation folds, graphical plots were used. Figure 8 illustrates the changes in the loss function and MAE over different training epochs for the training and validation data (with 10% of the training data set aside for validation) in the best fold. These plots show how the loss function and MAE decrease as training progresses, approaching a steady value in the best fold. Through these graphs, we can assess the model’s effectiveness in avoiding overfitting, as well as its ability to accurately learn PPG signal features and predict SBP and DBP. In the figures, the plot on the left shows changes in the loss function, while the plot on the right displays changes in MAE over training epochs. This graphical analysis serves as an important tool for evaluating the quality of training and model performance.

Figure 9 presents the scatter plot of actual versus predicted BP values for the validation dataset. The left plot corresponds to SBP for the best fold, Fold 1, and the right plot corresponds to DBP for the best fold, Fold 3. As observed, most points are closely aligned with the ideal prediction line (y = x), indicating the model’s high accuracy in BP estimation.

Figure 10 presents the test results of the proposed network for predicting SBP and DBP in each of the five cross-validation folds. These results are illustrated for two key model evaluation metrics: the loss function and MAE. In each figure, the plot on the left shows the distribution of loss function values for each of the five folds, clearly highlighting the fluctuations and performance variations of the network across folds. The plot on the right displays the distribution of MAE values for the same folds, providing insights into the overall accuracy of the model in BP prediction.

Figure 11 displays the Bland-Altman plots18 for the best fold. This plot is a crucial tool for assessing the agreement between the actual and predicted BP values. In this diagram, the horizontal axis represents the mean of the actual and predicted values, while the vertical axis indicates the difference between these values.

The Bland-Altman plot allows researchers to examine the distribution of differences against the mean values and identify data points that exhibit significant discrepancies. The blue lines represent the limits of agreement (1.96 ± standard deviation of the mean differences), and the red line indicates the mean difference. This plot demonstrates how closely the model’s predictions in the best fold align with the actual values and whether the differences are uniformly distributed.

We tested various hyperparameters using 5-fold cross-validation to achieve better results. The optimal hyperparameters of the network, which yielded favorable outcomes for SBP and DBP, are presented in Table 4.

Comparing similar studies in this field is often challenging due to variations in databases, methodologies, and evaluation standards. Some studies have achieved high accuracy using small, selected subsets of data, while others have worked with large-scale datasets, often yielding relatively lower accuracy. Given the limited number of similar studies, we have endeavored to conduct a fair and well-reasoned comparison.

Looking at Table 5, it can be seen that Baek et al.26 conducted a study on end-to-end BP prediction using fully convolutional networks based on deep learning. Their method bypasses traditional PWV feature extraction, instead utilizing raw ECG and PPG signals directly. This approach allows for calibration-free predictions while achieving high accuracy, with an MAE of 9.30 for SBP and 5.12 for DBP using combined ECG and PPG signals, and 10.86 for SBP and 5.95 for DBP with only PPG.

Wang et al.37 used CNN and RNN networks in their study to predict BP based on PPG signals. In this study, data from 90 patients were used from the MIMIC database. The study demonstrated that combining CNN and RNN could improve the accuracy of BP prediction. They achieved a MAE of 3.95 for SBP and 2.14 for DBP. This study showed that RNN networks have the ability to model complex time sequences in PPG signals; however, there is still a need to increase the number of participants to enhance generalizability and further improve BP estimation accuracy.

Panwar et al.16 used CNN and LSTM for BP prediction. The data in this study were extracted from the MIMIC II database and included information on 1557 patients. They showed that using LSTM can improve model performance in predicting accurate BP values. Using this method, an MAE of 3.97 for SBP and 2.30 for DBP was achieved. These results indicated that LSTM, due to its ability to model long-term temporal dependencies, can be more accurate in estimating BP compared to traditional methods.

Ibtehaz et al.17 explored the accuracy of BP prediction using U-Net and MultiResUNet architectures. This study was conducted on the MIMIC II database and included data from 942 patients. They demonstrated that U-Net and MultiResUNet architectures could improve the accuracy of BP prediction. However, the results showed an MAE of 5.73 for SBP and 3.45 for DBP, highlighting challenges in using these methods for precise BP estimation, particularly when input data are noisy or nonlinear.

Cheng et al.18 used the ABP-Net model, incorporating PPG, VPG, and APG signals, to predict BP. Data for this study were obtained from the MIMIC II database and included information on 1627 patients. They achieved an MAE of 3.27 for SBP and 1.90 for DBP. The use of multiple signals combined in the ABP-Net model led to improved prediction accuracy compared to previous models. This study indicated that using multiple signals simultaneously could enhance the accuracy of BP prediction.

Tang et al.19 conducted two separate studies to investigate the impact of using PPG, VPG, and APG signals on BP prediction. Their studies were limited to 500 participants. In the first study, they used the W-Net model for BP prediction using PPG, VPG, and APG signals, achieving an MAE of 2.62 for SBP and 1.56 for DBP. In the second study, they only used the PPG signal for BP prediction, resulting in an MAE of 2.60 for SBP and 1.45 for DBP. These results indicated that additional signals could provide acceptable prediction accuracy, but using a single signal could offer better accuracy.

The results obtained from the proposed model highlight its high accuracy and superior performance relative to existing methods for non-invasive BP estimation. As illustrated in Table 5, our model—featuring a hybrid architecture combining CNN layers, BiLSTM layers, and an attention mechanism—outperformed previous approaches. This architectural combination allows for effective extraction of spatial and temporal features from the PPG signals, with the attention layer focusing on the most relevant signal segments for BP estimation. Consequently, the proposed model demonstrates a notable improvement in predicting both SBP and DBP.

Conclusion

In this study, we developed an advanced deep learning model for non-invasive BP estimation using PPG signals, providing a significant step toward continuous, wearable BP monitoring solutions. Our approach, which integrates CNN, BiLSTM, and an attention mechanism, effectively captures the spatial and temporal dependencies within PPG signals, yielding high accuracy and robustness across a large dataset of 2064 patients from the MIMIC-II database. The model achieved MAEs of 1.88 for SBP and 1.34 for DBP, surpassing the accuracy of prior PPG-based BP estimation studies.

Compared to traditional BP measurement methods, such as cuff-based techniques, our PPG-based approach enables continuous monitoring without discomfort, offering a feasible solution for wearable health technologies and real-time applications. The proposed architecture demonstrates the efficacy of hybrid deep learning models in extracting meaningful cardiovascular information solely from PPG signals, thereby eliminating the need for multi-signal setups (e.g., ECG or VPG), which adds to the practicality and simplicity of the system.

Our study also highlights the benefits of using a larger dataset than previous works, enhancing the model’s generalizability and reliability. The results underscore the potential of deep learning in non-invasive BP estimation, providing an accurate, scalable, and patient-friendly alternative to conventional methods. This approach could play a transformative role in future healthcare, enabling timely BP monitoring and management through wearable devices and contributing significantly to cardiovascular health management.

To further advance this research, future efforts should focus on expanding the dataset to include more diverse populations, which would improve the model’s adaptability across different demographic groups and clinical settings. Additionally, implementing and testing this model in real-time on wearable devices, such as smartwatches or fitness trackers, would validate its performance under dynamic, everyday conditions. Such implementations would help optimize the model for power efficiency and on-device processing, paving the way for scalable, low-cost solutions in continuous BP monitoring. These advancements could empower individuals and healthcare providers with real-time insights, aiding in proactive management of hypertension and other cardiovascular conditions.

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are based on the publicly available database by Kachuee et al. The data used in this manuscript can be downloaded from this link https://archive.ics.uci.edu/dataset/340/cuff+less+blood+pressure+estimation (accessed on 20 December 2024). This dataset was used under its open access terms, and all analyses were conducted in accordance with the original authors’ data usage policies and guidelines.

References

Laflamme, M. A. & Murry, C. E. Heart regeneration. Nature 473 (7347), 326–335 (2011).

Townsend, N. et al. Cardiovascular disease in europe: epidemiological update 2016. Eur. Heart J. 37 (42), 3232–3245 (2016).

Hullender, D. A. & Brown, O. R. Simulations of blood pressure and identification of atrial fibrillation and arterial stiffness using an extended Kalman filter with oscillometric pulsation measurements. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 198, 105768 (2021).

Ativie, R. N. & Onah, U. E. Relationship between selected risk factors for cardiovascular diseases and the quality of life. Open. J. Therapy Rehabilitation. 7 (3), 106–119 (2019).

Miotto, R., Wang, F., Wang, S., Jiang, X. & Dudley, J. T. Deep learning for healthcare: review, opportunities and challenges. Brief. Bioinform. 19 (6), 1236–1246 (2018).

Ravì, D. et al. Deep learning for health informatics. IEEE J. Biomedical Health Inf. 21 (1), 4–21 (2016).

Jilek, J. Electronic sphygmomanometers: the problems and some suggestions. Biomedical Instrum. Technol. 37 (4), 231–233 (2003).

Kirkendall, W. M., Burton, A. C., Epstein, F. H. & Freis, E. D. Recommendations for human blood pressure determination by sphygmomanometers, Circulation, vol. 36, no. 6, pp. 980–988, (1967).

Whelton, P. K., Carey, R. M. & Aronow, W. S. Acc/ Guideline for the prevention, Detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: a Report of the American College of Cardiology/American heart Association. Task force on clinical practice guidelines//J. Am. Coll. Cardiol.-2017.-Nov 13, Почки, vol. 7, no. 1, pp. 68–74. (2018).

Parati, G. et al. European Society of Hypertension guidelines for blood pressure monitoring at home: a summary report of the Second International Consensus Conference on Home Blood Pressure Monitoring, Journal of hypertension, vol. 26, no. 8, pp. 1505–1526, (2008).

Sharma, M. et al. Cuff-less and continuous blood pressure monitoring: a methodological review, Technologies, vol. 5, no. 2, p. 21, (2017).

Loh, H. W. et al. Application of photoplethysmography signals for healthcare systems: An in-depth review, Computer Methods and Programs in Biomedicine, vol. 216, p. 106677, (2022).

Elgendi, M. PPG signal analysis: An introduction using MATLAB® (CRC, 2020).

Elgendi, M. et al. The use of photoplethysmography for assessing hypertension. NPJ Digit. Med. 2 (1), 60 (2019).

Elgendi, M. et al. Photoplethysmography Features Correlated with Blood Pressure Changes, Diagnostics, vol. 14, no. 20, p. 2309, (2024).

Panwar, M., Gautam, A., Biswas, D. & Acharyya, A. PP-Net: A deep learning framework for PPG-based blood pressure and heart rate Estimation. IEEE Sens. J. 20 (17), 10000–10011 (2020).

Ibtehaz, N. et al. PPG2ABP: Translating photoplethysmogram (PPG) signals to arterial blood pressure (ABP) waveforms, Bioengineering, vol. 9, no. 11, p. 692, (2022).

Cheng, J. et al. Prediction of arterial blood pressure waveforms from photoplethysmogram signals via fully convolutional neural networks. Comput. Biol. Med. 138, 104877 (2021).

Tang, Q., Chen, Z., Ward, R., Menon, C. & Elgendi, M. Subject-based model for reconstructing arterial blood pressure from Photoplethysmogram, Bioengineering, vol. 9, no. 8, p. 402, (2022).

Bramwell, J. C. & Hill, A. V. The velocity of pulse wave in man, Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Containing Papers of a Biological Character, vol. 93, no. 652, pp. 298–306, (1922).

Geddes, L., Voelz, M., Babbs, C., Bourland, J. & Tacker, W. Pulse transit time as an indicator of arterial blood pressure, psychophysiology, vol. 18, no. 1, pp. 71–74, (1981).

Kachuee, M., Kiani, M. M., Mohammadzade, H. & Shabany, M. Cuffless blood pressure Estimation algorithms for continuous health-care monitoring. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 64 (4), 859–869 (2016).

Dey, J., Gaurav, A. & Tiwari, V. N. InstaBP: cuff-less blood pressure monitoring on smartphone using single PPG sensor, in 40th annual international conference of the IEEE engineering in medicine and biology society (EMBC), 2018: IEEE, pp. 5002–5005., 2018: IEEE, pp. 5002–5005. (2018).

Su, P. et al. Long-term blood pressure prediction with deep recurrent neural networks, in 2018 IEEE EMBS International conference on biomedical & health informatics (BHI), : IEEE, pp. 323–328. (2018).

Tanveer, M. S. & Hasan, M. K. Cuffless blood pressure Estimation from electrocardiogram and photoplethysmogram using waveform based ANN-LSTM network. Biomed. Signal Process. Control. 51, 382–392 (2019).

Baek, S., Jang, J. & Yoon, S. End-to-end blood pressure prediction via fully convolutional networks. Ieee Access. 7, 185458–185468 (2019).

Esmaelpoor, J., Moradi, M. H. & Kadkhodamohammadi, A. A multistage deep neural network model for blood pressure Estimation using photoplethysmogram signals. Comput. Biol. Med. 120, 103719 (2020).

Radha, M. et al. Estimating blood pressure trends and the nocturnal dip from photoplethysmography. Physiol. Meas. 40 (2), 025006 (2019).

Hsu, Y. C., Li, Y. H., Chang, C. C. & Harfiya, L. N. Generalized deep neural network model for cuffless blood pressure estimation with photoplethysmogram signal only, Sensors, vol. 20, no. 19, p. 5668, (2020).

Zadi, A. S., Alex, R., Zhang, R., Watenpaugh, D. E. & Behbehani, K. Arterial blood pressure feature Estimation using photoplethysmography. Comput. Biol. Med. 102, 104–111 (2018).

Martínez, G. et al. Can photoplethysmography replace arterial blood pressure in the assessment of blood pressure? J. Clin. Med. 7 (10), 316 (2018).

Xie, Q., Wang, G., Peng, Z. & Lian, Y. Machine learning methods for real-time blood pressure measurement based on photoplethysmography, in IEEE 23rd International Conference on Digital Signal Processing (DSP), 2018: IEEE, pp. 1–5., 2018: IEEE, pp. 1–5. (2018).

Mohammadi, H., Tarvirdizadeh, B., Alipour, K. & Ghamari, M. Blood Pressure Estimation through Photoplethysmography and Machine Learning Models, in 9th International Conference on Control, Instrumentation and Automation (ICCIA), 2023: IEEE, pp. 1–6., 2023: IEEE, pp. 1–6. (2023).

Mohammadi, H., Tarvirdizadeh, B., Alipour, K. & Ghamari, M. Noninvasive Blood Pressure Classification Based on Photoplethysmography Using Machine Learning Techniques, in 2024 32nd International Conference on Electrical Engineering (ICEE), : IEEE, pp. 1–7. (2024).

Duan, K., Qian, Z., Atef, M. & Wang, G. A feature exploration methodology for learning based cuffless blood pressure measurement using photoplethysmography, in 38th Annual international conference of the IEEE engineering in medicine and biology society (EMBC), 2016: IEEE, pp. 6385–6388., 2016: IEEE, pp. 6385–6388. (2016).

Priyanka, K. et al. Estimating blood pressure via artificial neural networks based on measured photoplethysmography waveforms, in 2018 IEEE SENSORS, : IEEE, 1–4. (2018).

Wang, C. et al. An end-to-end neural network model for blood pressure estimation using ppg signal, in Artificial Intelligence in China: Proceedings of the International Conference on Artificial Intelligence in China, : Springer, pp. 262–272. (2020).

Ibtehaz, N. et al. Ppg2abp: Translating photoplethysmogram (ppg) signals to arterial blood pressure (abp) waveforms using fully convolutional neural networks, arXiv preprint arXiv:.01669, 2020. 2020. (2005).

Lin, W. H. et al. Towards accurate Estimation of cuffless and continuous blood pressure using multi-order derivative and multivariate photoplethysmogram features. Biomed. Signal Process. Control. 63, 102198 (2021).

Wang, D. et al. Photoplethysmography based stratification of blood pressure using multi-information fusion artificial neural network, in Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops, pp. 276–277. (2020).

Goldberger, A. L. et al. PhysioBank, PhysioToolkit, and PhysioNet: components of a new research resource for complex physiologic signals, circulation, vol. 101, no. 23, pp. e215-e220, (2000).

Saeed, M. et al. Multiparameter intelligent monitoring in intensive care II: a public-access intensive care unit database. Crit. Care Med. 39 (5), 952–960 (2011).

Dua, D. & Graff, C. Machine learning repository, University of California, Irvine, School of Information and Computer Sciences. Available online at: (2017). http://archive.ics.uci.edu/ml,.

Kachuee, M., Kiani, M. M., Mohammadzade, H. & Shabany, M. Cuff-less high-accuracy calibration-free blood pressure estimation using pulse transit time, in 2015 IEEE international symposium on circuits and systems (ISCAS), : IEEE, pp. 1006–1009. (2015).

Kim, B. S. & Yoo, S. K. Motion artifact reduction in photoplethysmography using independent component analysis. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 53 (3), 566–568 (2006).

Arunkumar, K. & Bhaskar, M. Heart rate Estimation from photoplethysmography signal for wearable health monitoring devices. Biomed. Signal Process. Control. 50, 1–9 (2019).

Biswas, D. et al. CorNET: deep learning framework for PPG-based heart rate Estimation and biometric identification in ambulant environment. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Circuits Syst. 13 (2), 282–291 (2019).

Koneshloo, A. & Du, D. A novel motion artifact removal method via joint basis pursuit linear program to accurately monitor heart rate. IEEE Sens. J. 19 (21), 9945–9952 (2019).

Reiss, A., Indlekofer, I., Schmidt, P. & Van Laerhoven, K. Deep PPG: Large-scale heart rate estimation with convolutional neural networks, Sensors, vol. 19, no. 14, p. 3079, (2019).

Nti, I. K., Nyarko-Boateng, O. & Aning, J. Performance of machine learning algorithms with different K values in K-fold cross-validation. Int. J. Inform. Technol. Comput. Sci. 13 (6), 61–71 (2021).

LeCun, Y., Bengio, Y. & Hinton, G. Deep learning, nature, vol. 521, no. 7553, pp. 436–444, (2015).

Goodfellow, I. Deep Learning (MIT Press, 2016).

Schlesinger, O., Vigderhouse, N., Eytan, D. & Moshe, Y. Blood pressure estimation from PPG signals using convolutional neural networks and Siamese network, in ICASSP –2020 IEEE international conference on acoustics, speech and signal processing (ICASSP), 2020: IEEE, pp. 1135–1139., 2020: IEEE, pp. 1135–1139. (2020).

Hochreiter, S. & Schmidhuber, J. LSTM can solve hard long time lag problems. Advances Neural Inform. Process. Systems, 9, (1996).

Schuster, M. & Paliwal, K. K. Bidirectional recurrent neural networks. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 45 (11), 2673–2681 (1997).

Bahdanau, D. Neural machine translation by jointly learning to align and translate, arXiv preprint arXiv:1409.0473, (2014).

Vaswani, A. Attention is all you need. Advances Neural Inform. Process. Systems, (2017).

Scikit-learn developers Regression metrics, in Scikit-learn 1.4.0 documentation, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://scikit-learn.org/stable/modules/model_evaluation.html#regression-metrics. [Accessed: Nov. 10, 2024].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed significantly to the research presented in this manuscript and have agreed to its publication. Hanieh Mohammadi conceptualized the study, led the data analysis, and drafted the manuscript. Bahram Tarvirdizadeh, Khalil Alipour, and Mohammad Ghamari provided supervisory support and were critically involved in the review and editing of the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Given the nature of this research, which involved the analysis of existing, publicly available data without direct involvement of human or animal subjects, formal ethical approval was not required.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mohammadi, H., Tarvirdizadeh, B., Alipour, K. et al. Cuff-less blood pressure monitoring via PPG signals using a hybrid CNN-BiLSTM deep learning model with attention mechanism. Sci Rep 15, 22229 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-07087-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-07087-2