Abstract

The synergistic effects of landscape composition and spatial configuration are critical for regulating terrestrial carbon storage. However, their dynamic relationships and driving pathways remain poorly understood, especially in high-altitude semi-arid ecosystems. As the world’s largest alpine carbon sink, the Qinghai Tibetan Plateau (QTP) is undergoing rapid landscape transformation, threatening the stability of its carbon storage function. This study integrates the InVEST carbon storage model with Fragstats metrics to investigate how multiscale landscape dynamics influence carbon storage services on the QTP. From 1980 to 2020, grasslands experienced the most significant land conversion (468 × 103 km2), primarily into unused land (75.39%), forest (15.32%), and water (7.67%). These transitions increased landscape fragmentation and diversity while reducing aggregation and connectivity. Carbon storage was positively correlated with Aggregation Index and Largest Patch Index, but negatively correlated with Patch Density and Edge Density. Over four decades, total carbon storage (TCS) decreased by 4.86% from 270 × 108 to 258 × 108 t driven largely by a 29 × 108 t loss in grassland carbon, partly offset by an 11 × 108 t gain in forests. These findings help improve land use planning and management to boost carbon storage in high-altitude areas.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Ecosystem services represent a crucial nexus between human society and natural ecosystems and are indispensable for human well-being and sustainable economic and social development1,2,3. However, the United Nations Ecosystem Assessment Report indicates that 60% of the world’s ecosystem services have degraded over the past half century, thereby endangering the security and stability of global and regional ecosystems4,5. Among these services, terrestrial carbon storage plays a key role in climate regulation by absorbing atmospheric carbon dioxide, yet land use change remains the second-largest driver of CO₂ emissions after fossil fuels (Causing approximately 3.2 billion tons of carbon dioxide emissions annually)6,7,8. Land use and land cover (LULC) influences regional carbon storage by altering vegetation cover and soil quality9. Landscape patterns, an important expression of LULC, directly influence landscape heterogeneity through spatial changes, leading to alterations in ecosystem services and functions10,11. Recent studies showed that there are complex spatial correlations and feedback between carbon storage services and landscape pattern dynamics, rather than a simple linear relationship12,13.

Numerous studies have examined the links between landscape patterns and terrestrial carbon storage using a variety of spatial modeling tools and ecological indicators. For instance, researchers have employed spatially explicit models such as InVEST and FLUS to estimate carbon storage dynamics in relation to land use transitions and landscape metrics (e.g., patch density, contagion, edge density) across agricultural, urban, and forested regions14,15. At the regional scale, studies in the Yangtze River Delta and Pearl River Delta revealed that landscape fragmentation and urban expansion can significantly reduce ecosystem carbon sequestration potential16. Moreover, connectivity and aggregation indices have been shown to correlate with soil organic carbon and aboveground biomass, particularly in forest and wetland ecosystems4,12,17.

Despite the progress made, several critical knowledge gaps remain. First, the combined effects of landscape composition (e.g., the proportion of different land cover types) and configuration (e.g., spatial arrangement and fragmentation) on carbon storage have rarely been investigated in an integrated manner. Most existing studies tend to focus on a single aspect of landscape patterns—either composition (e.g., how much forest, grassland, water, or urban area exists within a region) or configuration (e.g., how these land cover types are spatially arranged), while overlooking their joint influence on ecosystem functions such as carbon storage. In reality, the interaction between composition and configuration can exert both positive and negative effects on biodiversity and ecosystem functioning. For example, it has been found that land use, slope, and elevation gradients can explain the spatial patterns of landscape services in the Yangtze River Basin18, while in high-altitude areas, landscape dynamics are primarily driven by land use and elevation gradients19. Therefore, simultaneously considering both landscape composition and configuration across different elevation zones is essential for accurately assessing ecosystem services. Second, existing research on the impacts of landscape composition and configuration on ecosystem services has largely focused on low-altitude areas—such as coastal or marine habitats, forests, and drylands—while our understanding of how these relationships operate in high-altitude, semi-arid ecosystems remains limited20. Third, most current studies rely on static or short-term observations, neglecting the long-term evolution of landscape–carbon interactions21. This oversight is particularly critical in mountainous regions, where climate variability and elevation gradients are pronounced. These areas tend to be ecologically fragile, with more complex landscape structures and limited self-regeneration capacity. Therefore, identifying the spatiotemporal impacts of landscape pattern changes on ecosystem services at a regional scale is vital for informing future landscape management and promoting sustainable development in such vulnerable areas.

The QTP is not only the world’s highest and largest plateau but also a crucial ecological security barrier for Asia. It’s cold, arid climate and slow soil decomposition rate result in unusually high soil organic carbon storage, accounting for nearly one-quarter of China’s total21,22. As a major carbon sink, absorbs 120 to 140 million tons of carbon dioxide annually—a pivotal contribution to China’s carbon neutrality targets23. However, recent decades have witnessed dramatic landscape changes, including lake expansion, desertification, and grassland degradation, driven by rapid urbanization and climate change24,25,26. These transformations threaten the Plateau’s carbon sink capacity, yet little is known about how the spatial distribution and configuration of landscape elements shape the dynamics of carbon storage services on the QTP. Most existing studies have focused on soil or individual land use types, lacking a holistic, pattern-based perspective27,28.

To address these gaps, this study adopts a landscape pattern–carbon storage coupling framework to investigate the dynamic response of carbon storage services to both the composition and configuration of multiple land cover types on the QTP. This represents a novel analytical approach, particularly well-suited to capturing the complexity of land–carbon interactions in fragile high-altitude ecosystems. Specifically, this study aims to: (1) analyze the spatiotemporal evolution of land use and landscape structure from 1980 to 2020; (2) quantify changes in carbon storage across different land use categories; and (3) evaluate the influence of landscape composition (e.g., the proportion of land cover types) and configuration (e.g., patch size and connectivity) on TCS. The findings offer practical guidance for developing land management and carbon sequestration strategies tailored to the unique environmental conditions of the QTP.

Material and methods

Study area

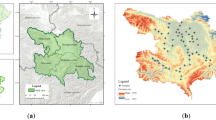

Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau (QTP) is situated in the southwestern region of China (26°00′-39°47′N, 73°19′-104°47′E), covering 2.57 million square kilometers, which constitutes 26.8% of China’s total land area (Fig. 1). Including the entire Tibet Autonomous Region and Qinghai Province, and parts of Yunan Province, Gansu Province, Sichuan Province and Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region29. There is a significant regional land cover transition from alpine deserts to alpine grasslands, meadows, mats, shrubs, and forests as one moves from northwest to southeast30. Plateau is characterized by extensive vegetation coverage, which offers essential carbon sequestration services and is vital to the global carbon cycle31. Therefore, QTP has become an ideal site for studying the dynamic response of carbon storage services to key landscape patterns in typical alpine climate areas.

The location of the Qinghai Tibetan regions (QTP), China. Note: Generated using ArcGIS Pro 3.1, https://www.esri.com/en-us/arcgis/products/arcgis-pro/overview.

Datasets

LULC data were obtained from the Data Center for Resources and Environmental Sciences, Chinese Academy of Sciences (RESDC) (http://www.resdc.cn). The spatial resolution of the LULC data is 30 m. Account for the stability of land cover over short-term periods, a 10–20 years interval was chosen to more clearly highlight the characteristics of LULC structure changes. This study selected LULC data from the years 1980, 1990, 2000, 2010, and 2020 to delegate the land cover and landscape features of the QTP during different periods. This study focused on six primary land categories: cropland, forest, grassland, water, construction land, and unused land.

Carbon density data for different LULC types on the QTP were statistically analyzed by collecting data from the China Ecosystem Research Network (http://www.cnern.org.cn) and selecting published literatures29,32,33,34,35,36 (Table 1). TCS was calculated based on LULC data.

The elevation dataset, sourced from Geospatial Data Cloud (http://www.gscloud.cn) with a spatial resolution of 90 m, was employed to examine the dynamic changes in landscape patterns across different altitudes from 1980 to 2020.

Methods

The workflow for assessing the impact of landscape pattern changes on carbon storage services in the QTP is shown in Fig. 2. The study includes the following four parts: first, the spatiotemporal dynamics of different LULC types during the period from 1980 to 2020 (including: 1980, 1990, 2000, 2010, and 2020) are analyzed; second, landscape pattern indices are calculated for different periods, elevations, and land types based on LULC data; third, the total carbon storage in four basic carbon pools (aboveground, underground, soil, and dead biomass) for different land types over the past 40 years is quantified; finally, a correlation analysis is conducted to quantify the relationship between the dynamics of landscape patterns in different land types and carbon storage services.

Technology roadmap for this study. Note: Generated using Visio Standard 2021, https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/microsoft-365/visio/flowchart-software.

Spatiotemporal LULC change analysis

The LULC transition matrix was utilized to evaluate the rates of change among different LULC types37. The formula is as follows:

where \(i\) is a certain LULC type; \({S}_{i}\) is the area before transferred; \({S}_{ii}\) is the area that does not be transferred; \(T\) represents the duration of the study.

Selections and measurements of Landscape metrics

Landscape pattern metrics provide a quantitative assessment of the structural composition and spatial arrangement of landscape patterns across three hierarchical levels: patch, landscape, and class. The patch level focuses on the attributes of individual landscape patches, the landscape level captures the overall spatial pattern of the entire study area, and the class level aggregates landscape characteristics across various land types. The landscape pattern system encompasses intricate information that cannot be expressed by a single metric. Generally, a single index can only summarize information regarding one or a few aspects of the entire landscape system38. Therefore, the selection of landscape metrics should adhere to the following principles: First, highly correlated metrics should be excluded in statistical analyses. Second, the selection of landscape metrics should be guided by the research objectives and the regional characteristics. As this study focuses on ecosystem services in the plateau region—specifically carbon storage—metrics related to patch connectivity and fragmentation were prioritized. Accordingly, the Aggregation Index (AI) and Patch Density (PD) were selected to represent landscape connectivity and fragmentation, respectively, in relation to ecosystem service functions. Finally, the Shannon Diversity Index (SHDI) and the Shannon Evenness Index (SHEI) were used to assess overall landscape diversity and evenness across the plateau. The definition and range of landscape metrics are described in Table 2. All landscape metrics were computed using FRAGSTATS 4.2 software, which is used to analyze and evaluate landscape metrics.

Moving window method and Semi-variogram model

The moving window technique applies raster data to extract relevant landscape metrics, shifting one grid incrementally from the top-left corner across the area. During this process, landscape metrics are calculated for each window, enabling the visualization of the spatial distribution of landscape metrics in the landscape level39. The accuracy of the computed results is influenced by the scale at which landscape features were selected. The ideal analysis granularity for the study area was established using the granularity effect of landscape pattern metrics alongside the area information conservation evaluation model. This granularity was then used to apply the semi-variation function to obtain the optimal analysis amplitude, thereby determining the feature scale. This study selected the PD, AI, and SHDI metrics, set the moving window size to an odd multiple of 300 m, and used 3600 m as the upper limit to calculate and statistically analyze the landscape metrics changes at different granularities. A lower (C0/(C0 + C)) value indicates reduced spatial variation and increased stability of the landscape metrics (see SI Appendix Figure S1). The stability of the three landscape pattern metrics initially increases and then decreases with the increase of window radius, reaching a certain value before stabilizing. Consequently, the determination of the feature scale can be carried out. The results demonstrated the presence of clear turning points on the trend chart at particle sizes of 1200 m and 1800 m. When the window was 900 m, it displayed an upward trend and unstable changes, while at 1500 m and 2100 m, it showed a downward trend and unstable changes, which could not be used as characteristic scales. The spatial variation characteristic values of the three landscape indices begin to stabilize at approximately 3000 m, indicating that this scale can reflect the spatial configuration and properties of the research area’s landscape. An excessive scale (3300 m or 3600 m) can lead to a significant loss of information patterns; therefore, this study selected 3000 m as the optimal feature analysis scale for the landscape pattern of the QTP.

This study employs the semi-variogram model (SVM) to determine the scale of landscape characteristics based on moving windows. The SVM reflects the spatial relationship between a sampling point and its neighboring sampling points39. Regionalized variable \({Z}_{(x)}\) at points \(x\) and \(x+h\) is half of the variance of the \({Z}_{(x)}\) subtraction the \({Z}_{(x+h)}\) to define the semi-variogram, denoted as \(r\left(x,h\right)\):

The SVM reflects the spatial relationship between a sampling point and its adjacent points. The curve has two important points: the point with a 0 interval and the inflection points when the semi-variogram trend stabilizes. These two points generate four corresponding parameters: Nugget, Range, Still, and Partial Still, which reflect changes in landscape pattern. The joint action of the sampling points produces Nugget (\({C}_{0}\)). As the interval between the sampling points increases, the initial nugget value reaches a stable constant, which is Still (\({C+C}_{0}\)). The partial base value, which is the structural variance C, represents the difference between the base value and the nugget effect. The block-to-base ratio \({C}_{0}/\)(\({C+C}_{0}\)) denotes the proportion of block value to base value. The smaller the ratio of \({C}_{0}/\)(\({C+C}_{0}\)), the more stable the spatial autocorrelation. When the ratio variation tends to stabilize, it indicates that the landscape index tends to stabilize in spatial variation.

InVEST model

The InVEST model is a comprehensive ecosystem service and trade-off assessment model that provides technical support for visualizing, analyzing dynamically, and quantifying ecosystem functions40. We employed the carbon storage and sequestration module of the InVEST 3.7.0 model to estimate the TCS on the QTP from 1980 to 2020. The carbon storage is based on LULC data and divides it into four basic carbon pools: \({C}_{above}\), \({C}_{below}\), \({C}_{soil}\) and \({C}_{dead}\). The formula is as follows:

where \({C}_{t}\) is the total carbon storage (TGS); \(i\) is a specific LULC type; n is the total number of LULC types; and \({S}_{i}\) refers to the area of LULC type \(i\) (unit: hm2).

Correlation analysis

The values of different LULC landscape metrics and TCS within grids were exacted to points. Then, the relationship between landscape indices and carbon storage was determined by Pearson’s test from 1980 to 202010.

Results

LULC dynamic variations

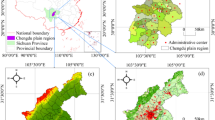

As shown in Fig. 3 and Table 3, the overall LULC structure of the QTP remained stable, with less than 1% (the ratio of the total land area transferred from the plateau to the total plateau area) of area changing between 1980 and 2020. However, significant changes were observed in both the area and proportion of various land types. Grassland was the predominant LULC type, constituting exceed half of the total area of the QTP, primarily distributed in the southeastern and central regions. Unused land comprised approximately 30%, mainly located in the northern region. Forest accounted for around 11% and was situated in the southeastern part of the plateau. Water covered 4.5% and were uniformly distributed across the QTP. Construction land and cropland represented 0.07% and 0.8%, respectively, and were found in the southeastern plateau and certain river valleys (Fig. 3 and Table 3). Over the past four decades, the area of construction land experienced an extraordinary growth rate of 122.31%, making it the most rapidly expanding category. This was followed by increases of 26.36% in unused land and 24.55% in water resources. Additionally, cropland and forest land expanded by 18.67% and 15.1%, respectively.

The spatial distribution of LULC in 1980, 1990, 2000, 2010, and 2020, and the changes between 1980 and 2020 on the QTP. Note: Generated using ArcGIS Pro 3.1, https://www.esri.com/en-us/arcgis/products/arcgis-pro/overview.

Significant differences in conversion rates across different land types from 1980 to 2020. Grasslands experienced the largest area of conversion, totaling 468 × 103 km2, primarily converting to unused land, forest, and water. The transferred areas accounted for 75.39%, 15.32%, and 7.67% of the total converted area, respectively (Fig. 4). The transform of grasslands to unused land was widely observed in the southern part of the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region; grasslands to unused land was primarily distributed in southeastern Tibet and Gansu Province, while grassland-to-water conversions were scattered distributed in the plateau (Fig. 3). The total conversion area of unused land amounted to 204.7 × 103 km2, mainly converting to grassland and water, accounting for 79.3% and 13% of the total converted area, respectively. In the southern Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, there was widespread conversion of unused land to grassland. Forests experienced a total conversion area of 48.3 × 103 km2, with 84% of this area transitioning to grassland and 8.5% to unused land. The transition from forest to grassland and unused land areas was widely distributed in the river valleys of southeastern Tibet, while the rates of conversion between other LULC types remained relatively low.

Various LULC types transitions on the QTP from 1980 to 2020 (unit: 103 km2). Note: Generated using Origin 2021, https://www.originlab.com/

Dynamics of landscape patterns at both the landscape and class levels

The landscape pattern showed an obvious spatiotemporal change over the past four decades (Fig. 4 and SI Appendix Figure S2). At the landscape scale, PD, LSI, SHDI, and SHEI demonstrated upward trends, while LPI, AREA_MN, and AI exhibited downward trends (Table 4). The LPI and AI, which reflect the dominant types and connectivity of landscapes, showed a decreasing trend, indicating increased human impact, resulting in a decrease in dominant landscape types, as well as decreasing connectivity and aggregation between landscapes. SHDI and SHEI have grown rapidly and showed a gradually increasing trend in space from northwest to southeast, indicating an increase in landscape diversity and richness on the QTP (see SI Appendix Figure S2).

As altitude increases, landscape fragmentation, diversity metrics, and evenness metrics initially increase and subsequently decrease (Fig. 5). Forest landscapes dominate the southeastern edge of the plateau at altitudes below 2500 m, accounting for only 2.37% of the entire plateau area and exhibiting a relatively low degree of landscape fragmentation. The altitude range between 2,500 and 3,500 m includes both the sparsely vegetated northern desert area and the primary human activity region in the east. These areas are characterized by increasing landscape fragmentation (PD > 0.4) and high diversity (SHEI > 0.56). The main grazing areas are situated in the middle to high-altitude range between 3500 and 4500 m, characterized by a higher degree of landscape fragmentation and complex landscape shapes. The high-altitude zone between 4500 and 5500 m is primarily composed of high-altitude grasslands and alpine vegetation in the northwest, covering over half of the total plateau area (51.79%). This zone is characterized by uniform and complete landscape types, with a high degree of clustering of landscape patches (AI > 92). In extremely high-altitude areas above 5500 m, the landscape exhibits the highest degree of aggregation, high landscape richness and evenness, diverse LULC types, and relatively low fragmentation.

Spatial distributions and vertical distributions characteristics of average landscape metrics on the QTP from 1980 to 2020. Note: Generated using ArcGIS Pro 3.1, https://www.esri.com/en-us/arcgis/products/arcgis-pro/overview; and using FRAGSTATS 4.2, https://www.fragstats.org/

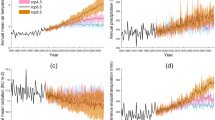

Overall, landscape metrics at different altitudes exhibited significant temporal variation trend. Before 2000 fluctuations in these metrics were relatively small, but after 2000, the range of fluctuations increased of all landscape metrics. In low-altitude and medium–high altitude areas, PD and SHDI exhibit a notable upward trend, while LPI shows a significant decline trend, suggesting increased landscape fragmentation and decreased patch aggregation from 1980 to 2020. In contrast, in high-altitude areas, AI demonstrates an increasing trend. The degree of landscape fragmentation in extremely high-altitude areas is accelerating, while the richness and evenness of the landscape have improved (Fig. 6).

Vertical distribution characteristics of landscape metrics from 1980 to 2020. Note: Generated using FRAGSTATS 4.2, https://www.fragstats.org/;and using python 3.11.8, https://www.python.org/downloads/release/python-3118/

The rate of change in landscape metrics varied obviously between different LULC types (Fig. 7). For the cropland, the SPLIT, ED, and LPI mostly increased at a rate of 17.3%, while other landscape metrics showed no significant changes between 1980 and 2000; For forest, LPI increased by 15.6%, while the AREA_MN decreased at a rate of 13.2%, with no significant changes in other landscape metrics; For the grassland, AREA_MN showed an increasing trend, while other metrics exhibited no significant variations. For the water, the SPLIT decreased, while the change rates of AI, AREA_MN, and PD all increased, with PD showing the most significant rise at 23.4%; For the construction land, the AI increased, while LPI, ED, SPLIT and LSI decreased; For the unused land, ED, PD and AI decreased, while other indices show no significant changes. Between 2000 and 2020, for cropland, LSI and ED showed a significant decreasing trend, while SPLIT, AI, ED, LPI and AREA_MN increased, with AI mostly growing at a rate of 14.3%; For forest, all landscape metrics showed an increasing trend; For the grassland, except for LPI and AI, others landscapes metrics increased; For the water, LSI, AREA_MN, LPI, and AI all increased, with LPI experiencing the most substantial growth at 34%, while SPLIT, ED and PD decreased; For the construction land, exception of LSI and LPI, others landscapes metrics increased; For the unused land, exception of the PD, others landscapes metrics increased.

Heat map of the rate of change in landscape pattern metrics for different LULC types from 1980 to 2020 on the QTP. The data were standardized using the "maximum value method." The radii of the heat map circles represent the landscape metrics for 1980 and 2020, while the circle colors indicate the rate of change in these metrics from 1980–2000 and 2000–2020, illustrating the range of changes across different land types. (a) 1980–2000. (b) 2000–2020. Note: Generated using FRAGSTATS 4.2, https://www.fragstats.org/;and using python 3.11.8, https://www.python.org/downloads/release/python-3118/

Temporal and spatial in carbon storage services

The spatial distribution of TCS shows notable heterogeneity, exhibiting a decreasing trend from southeast to northwest (Fig. 8). Between 1980 and 2020, TCS decreased significantly, with 16.5% of regions experiencing a decline, 10.6% showing an increase, and 72.7% exhibiting no significant changes. The increase in carbon reserves was primarily observed in the southeastern and central regions, specifically in the Yarlung Zangbo River and Hengduan Mountain regions, with a few areas in the Qiangtang Plateau. Conversely, the areas with decreased TCS were primarily located in the central and western regions of the plateau, specifically within the central and western parts of the Tibet Autonomous Region.

Space layout of total carbon storage (TCS) for the year for the year 1980, 1990, 2000, 2010, 2020, and 1980–2020 variation on the QTP. Note: Generated using ArcGIS Pro 3.1, https://www.esri.com/en-us/arcgis/products/arcgis-pro/overview; and using the Invest model https://naturalcapitalproject.stanford.edu/software/invest.

The TCS exhibited a declining trend from 1980 to 2020 on the QTP (Fig. 9). By 2020, TCS had decreased by 4.86% compared to 1980. Between 1980 and 2000, the TCS remained stable at 270 × 108 t. Since 2000, TCS has rapidly declined, reaching 258 × 108 t, which was the lowest in the four decades. In the four carbon pool, the \({C}_{soil}\) was 240 ~ 227 × 108 t, which accounts for approximately 88% of the QTP. The \({C}_{above}\) and \({C}_{below}\) carbon storage was 14 ~ 13 × 108 t and 13–15 × 108 t, accounting for approximately 5% of the TCS. The \({C}_{dead}\) was about 3 × 108 t, only accounting for 1% of the TCS in the plateau (Fig. 9a). The grasslands have the highest TCS (148 ~ 177 × 108 t), followed by forest (75 ~ 86 × 108 t), unused land (18 ~ 23 × 108 t), cropland (1.2 ~ 1.4 × 108 t) and water (0.4 ~ 1 × 108 t). Cropland, forest, and unused land show an increasing trend in TCS, while the grasslands were decreasing during the 1980 to 2020 (Fig. 9b). Especially, after to 2000, grassland carbon storage has significantly declined by 29 × 108 t, while forest and unused land increasing by 11 × 108 t and 5 × 108 t.

Variations in Total Carbon Storage (TCS) from 1980 to 2020. (a) Change in carbon storage of different carbon pool in the QTP from 1980 to 2020. (b) TCS for different LULC types. Note: Generated using the Invest model https://naturalcapitalproject.stanford.edu/software/invest; and using the Origin 2021, https://www.originlab.com/

Effect of landscape pattern on carbon storage services

Alterations in landscape pattern metrics for various land types have a significant effect on ecosystem services associated with carbon storage (Fig. 10). At the class level, the carbon storage services of cropland showed a significant positive correlation with AREA_MN, AI, and LSI, while there was a negative correlation with SPLIT and PD. For forest and grassland, carbon storage services were positively correlated with AI, LPI and AREA_MN, while there was a significant negative correlated with SPLIT, PD and ED. For water, carbon storage services had a positive correlation with LSI and ED, while there was a negative correlation with AI. For construction land, carbon storage services had a positive correlation with LSI and ED, but negatively correlated with AI and AREA_MN. Similarly, for unused land, positive correlations were observed with ED and SPLIT, while negative correlations were found with LPI and AI.

Variations in the correlation between landscape metrics and total carbon storage (TCS) across different LULC types in 1980, 2000, and 2020. Note: * represents significance level p < 0.05, **represents significance level p < 0.01. Note: Generated using python 3.11.8, https://www.python.org/downloads/release/python-3118/

Discussion

Validation of model and limitations

This study employed the InVEST model to quantify the spatiotemporal dynamics of carbon storage on the Tibetan Plateau over the past four decades. Given the limited availability of field measurement data, the model outputs were validated using estimates from previous studies. The results reveal a spatial gradient in carbon storage characterized by higher values in the southeast and lower values in the northwest, a pattern broadly consistent with numerous prior studies. The estimated carbon storage range of the plateau in this study is between 258 × 108 and 270 × 108 t, which closely aligns with the estimates of 247–259 × 108 t and 262–272 × 108 t, respectively by Gao et al.29 and Hao et al.41, thereby suggesting a reasonable level of credibility.

Despite the model’s is widely used for estimating carbon storage and sequestration due to its simplicity and accessibility, it exhibits substantial limitations in representing dynamic ecological processes—particularly those associated with vegetation growth, species-specific functional traits, and human-led restoration activities. First, the structural limitations of the InVEST model result in an oversimplification of the carbon cycle. For instance, while warming may extend the growing season and enhance vegetation carbon sequestration, it can also accelerate soil respiration, leading to carbon loss—interactions that are not adequately captured by the model. Moreover, key biological processes such as photosynthesis and microbial activity are omitted, and carbon storage is assumed to change linearly over time, which may introduce bias in carbon sink estimates42. In particular, the model fails to incorporate age-dependent growth dynamics, lacking a module that represents biomass accumulation across different forest age classes. However, forest age significantly affects net primary productivity and carbon sequestration potential, with younger stands often acting as stronger carbon sinks than older forests43. Additionally, the model does not account for species-specific variation in carbon accumulation rates or phenological responses. Tree species differ markedly in growth rates, leading to differential carbon sequestration trajectories. As a result, carbon estimates may be biased in regions with high biodiversity. Recent research has also highlighted that:

Climate-induced phenological shifts, such as earlier leaf emergence or delayed senescence—can alter photosynthetic dynamics and carbon uptake44. In particular, longer growing seasons have been shown to enhance carbon assimilation in temperate forests45. Nonetheless, InVEST model does not simulate seasonal or interannual variability in vegetation carbon fluxes, limiting its ability to capture the temporal complexity of ecosystem functioning under climate change.

Second, the model lacks functionality to incorporate user-defined ecological restoration practices—such as reforestation schedules, thinning regimes, or fertilization interventions. Consequently, it cannot simulate the temporal trajectory of post-restoration carbon gains. To address these limitations, future research could integrate process-based ecosystem models that explicitly simulate biophysical and physiological processes, or develop hybrid approaches that combine the InVEST framework with time-series data derived from remote sensing. Furthermore, the model lacks the capacity to dynamically couple with permafrost thermodynamic processes. Previous studies have shown that the permafrost regions of the Tibetan Plateau store approximately 160–180 × 108 t of soil organic carbon, accounting for roughly 2.4% of global soil carbon stocks46. Deeper soil carbon in these areas is particularly sensitive to changes in temperature and moisture. However, this study only considered carbon storage variations within the top one-meter soil layer across major land cover types. Future work should therefore incorporate assessments of deep soil organic carbon in permafrost regions into the modeling framework to enhance the comprehensiveness and accuracy of carbon storage estimations.

Meanwhile, this model has certain limitations in evaluating long-term ecosystem responses to global change. To overcome these limitations and provide a more comprehensive evaluation, future research should consider integrating InVEST with process-based terrestrial ecosystem models such as CASA (Carnegie-Ames-Stanford Approach) and LPJ-GUESS (Lund-Potsdam-Jena General Ecosystem Simulator)29. These models simulate carbon fluxes in response to environmental drivers and can capture the nonlinear interactions between climate variability and vegetation dynamics. In addition, incorporating climate scenario projections (e.g., CMIP6 outputs) would allow for the assessment of future trajectories of carbon storage under different climate pathways40.

The correlation between LULC and landscape pattern

Over the past four decades, climate change and human activities have been the dominant drivers of LULC and landscape pattern changes on the QTP. While the overall LULC structure has remained relatively stable (land transfers affecting less than 1% of the plateau (see SI Appendix Table S1), substantial transitions among specific LULC types have occurred, particularly in grasslands. Grasslands have experienced the most extensive conversion, mainly into unused land and forest, altering the plateau’s landscape configuration10,30. This trend is most evident in the northwest QTP, southern Xinjiang, and western Tibet, where grasslands have transformed into bare land. This finding is consistent with the research conducted by Zhang and Zhou47. As warming intensifies and human pressures mount, conflicts between grasslands and livestock have accelerated degradation. Surveys indicate that degraded grassland now spans approximately 700,000 km2—about 25% of total grassland area on the plateau45.

From the 1970s to 2010, decertified areas increased by 506,075 km2 at an 8.3% growth rate16. Rapid temperature increases have disrupted alpine vegetation metabolism and reduced vegetation cover; while overgrazing and rodent infestations have worsened fragmentation. Between 2000 and 2010, grassland degradation peaked, with the most severe impacts observed in Three-River-Source National Park, the Qiangtang Plateau, and the Ruoergai Wetland. In the Three Rivers Headwater Region, moderately to severely degraded grassland expanded from 18 to 27%16. During the same period, the grassland–livestock balance index rose from 67.88 to 79.90%, largely due to overgrazing and drought40. In eastern Tibet, degraded grassland increased by 22%, with half the degradation attributed to human activities like fencing, which fragmented pastures47. Rising temperatures and declining precipitation further exacerbated grassland decline, resulting in simplified vegetation structures and reduced ecological resilience.

Landscape fragmentation serves as a key indicator of LULC transition. Over the past two decades, grasslands and water bodies on the QTP have shown high fragmentation rates of 26.3% and 23.4%, respectively (Fig. 6). The reduction in patch size and transformation of continuous landscapes into isolated patches have weakened habitat connectivity and species dispersal. These changes not only threaten ecological stability but also reduce habitat quality. As the source region for major rivers, the QTP has also experienced increasing watershed fragmentation driven by dam construction, road development, and agricultural expansion48. By 2023, eight cascade dams had been planned along the Yarlung Tsangpo River, and eleven large-scale dams were built in the Lancang River Basin49,50. These projects disrupted longitudinal river connectivity, reduced baseflow, impaired surface–groundwater interactions, and degraded wetland vegetation50. Concurrent land reclamation and urban growth in ecologically sensitive regions like Three-River-Source National Park have intensified patchiness and further decreased carbon storage capacity51.

Construction land and cropland have also expanded significantly since 1980. Construction land is the fastest-growing LULC category on the QTP, increasing by 122.31% over 40 years—91.82% of that growth occurred after 2000, highlighting the rapid pace of urbanization. Landscape metrics such as PD, ED, and AREA_MN have all increased, reflecting heightened fragmentation. At the same time, the AI index, indicating stronger connectivity and the emergence of large, contiguous urban patches. Population growth and socio-economic development have driven these changes. Between 1980 and 2020, the combined population of Tibet and Qinghai rose from 5.6 million to 9.6 million, and their GDP surged from 9.4 billion to 486.9 billion RMB52. Urban construction areas tripled, highway lengths quadrupled, and tourist numbers soared from 0.27 million to over 90 million18,38. These pressures contributed to greater human interference and landscape fragmentation.

Cropland fragmentation has similarly intensified. While the LPI has risen, indicating dominant cropland patches, increased fragmentation has resulted in more dispersed land parcels10. This shift is influenced by both policy and population pressures53. Since the mid-1970s, the altitudinal limits for cultivating winter wheat and highland barley have expanded by 133 m and 550 m, respectively, with suitable cropland expanding by 870 km2 by 200054. This expansion has primarily occurred in ecotones between agriculture and animal husbandry, increasing land-use intensity at higher elevations. The impacts of population growth on cropland distribution manifest in two ways55. First, higher food demand in densely populated areas requires more arable land; second, infrastructure development for rural settlements and public services consumes additional cropland56. According to official data, crop yields in Tibet increased from 2505 kg/ha in 1987 to 5711 kg/ha in 201711. However, this intensification has heightened spatial heterogeneity and fragmentation across agricultural landscapes on the plateau.

Altitudinal variations in landscape patterns on the QTP are primarily shaped by species distribution along elevation gradients57. Intensified landscape fragmentation in extreme high-altitude, while the richness and evenness of the landscape have improved of the QTP is primarily driven by glacier retreat and permafrost degradation, which have reduced by ~ 15% and ~ 16%, respectively, over the past 50 years. Glacial retreat (10–15 m/year) and permafrost thaw expose glacial till, bare ground, and karst lakes, breaking once-continuous habitats58. Meanwhile, climate-driven species migration has increased landscape richness and evenness, with new plant species colonizing ice-edge zones and species like Dolophragma polytrichoides shifting upward in elevation59.

Impacts of landscape patterns on carbon storage across various land types

The InVEST model was used to assess the spatiotemporal variation of TCS across the QTP from 1980 to 2020. Results revealed a declining TCS trend from southeast to northwest, consistent with previous studies29. However, since 2000, the TCS trajectories among different land types have diverged. While forest, cropland, and unused land exhibited increasing carbon storage, grasslands and water bodies showed declines. These shifts are closely tied to regional climatic dynamics43,52: central and western plateau regions have experienced limited precipitation, higher temperatures, and more frequent droughts, leading to grassland degradation and reduced carbon sequestration18. In contrast, warming and increased humidity in parts of the southwest and southeast have facilitated grassland-to-forest transitions, enhancing vegetation productivity and carbon uptake via photosynthesis10.

Changes in landscape patterns have significantly reshaped ecosystem structure and function, thereby altering carbon storage potential57. Forests and grasslands, which together contribute over 95% of the QTP’s total carbon stock, are particularly sensitive to landscape configuration2,37. Our correlation analysis indicates that forest TCS positively correlates with landscape aggregation indices (AI and AREA_MN) and negatively with fragmentation metrics (SPLIT, ED, and PD). This implies that clustered, less fragmented forest patches support higher carbon densities15. Previous findings in Qinghai Province confirm that high TCS areas are typically large, complexly shaped, but spatially cohesive forest and grassland patches37. Habitat fragmentation reduces forest patch size and intensifies edge effects, potentially accelerating soil organic carbon decomposition and impairing canopy photosynthetic efficiency58. Likewise, in grasslands, fragmentation disrupts nutrient cycling and seed dispersal, leading to lower vegetation productivity and reduced soil carbon sequestration59.

Unlike forests and grasslands, the TCS of unused land shows a positive correlation with ED, suggesting that moderate fragmentation may enhance microhabitat heterogeneity, thereby promoting local vegetation recovery and soil organic carbon accumulation. For example, fragmentation at the desert margins may give rise to small-scale vegetation patches, which in turn enhance local carbon sequestration. However, excessive fragmentation can still lead to soil erosion and carbon loss, necessitating a balance between fragmentation degree and carbon storage effects2. In the central and western regions of the QTP, climate drying has intensified grassland degradation, and fragmentation has further weakened their carbon sink function14. In contrast, humidification in the southeastern region has facilitated forest expansion, but high levels of fragmentation may still constrain the potential for carbon storage27.

Therefore, scientifically informed land-use policies are urgently required to enhance carbon sequestration potential in this ecologically vulnerable region and to support China’s national goals of carbon peaking and carbon neutrality. First, grazing intensity should be strategically optimized to maintain ecosystem integrity while sustaining pastoral livelihoods60 This includes the implementation of rotational grazing systems and livestock quotas determined by ecological carrying capacity, whereby rangelands are delineated into exclusion, rest, and active grazing zones based on vegetation productivity and ecological sensitivity. In ecologically fragile subregions, permanent grazing exclusions should be strictly enforced year-round to prevent further ecological degradation61. Furthermore, satellite-based monitoring of grassland productivity should be employed to continuously adjust grazing intensity in response to both seasonal and interannual climatic variability. Second, comprehensive large-scale ecological restoration programs should be promoted to maximize the region’s terrestrial carbon sink potential. Key initiatives include the “Return Grazing Land to Grassland” program, wetland restoration projects, and the establishment of a standardized evaluation system that integrates carbon sink enhancement as a core performance indicator62,63. Third, adaptive vegetation management is essential in the face of climate change47. This includes introducing drought and cold resistant deep-rooted species (e.g., Elymus nutans Griseb.) to enhance belowground carbon pools, and managing water resources through small-scale hydropower infrastructure in regions experiencing rising precipitation, which can mitigate seasonal drought and support vegetation recovery51,64.

While the present study emphasizes the effects of landscape fragmentation on carbon storage, it is essential to acknowledge that the carbon dynamics of alpine ecosystems are also strongly influenced by ongoing climatic changes, particularly in ecologically sensitive regions such as the QTP. Warming temperatures are accelerating permafrost thaw, releasing large quantities of soil organic carbon, while increased precipitation has promoted vegetation greening and carbon uptake. Conversely, overgrazing remains a critical driver of carbon loss in grasslands. The resulting decline in TCS triggers cascading ecological effects: (1) reduced water conservation capacity due to permafrost degradation, threatening downstream water supply for over 250 million people in the Yangtze and Yellow River basins16; (2) increased habitat fragmentation, endangering migratory species like the Tibetan antelope19; (3) altered carbon–climate feedback loops that may intensify global warming; and (4) diminished pastoral incomes by 20–30%, intensifying the conflict between ecological protection and rural livelihoods30. Hence, integrating landscape pattern optimization with adaptive ecosystem management is crucial to safeguarding both carbon stocks and regional ecological stability.

Conclusions

This study analyzed the spatiotemporal changes of LULC and landscape patterns on the QTP from 1980 to 2020. The InVEST model was utilized to assess TCS, and correlation analysis was conducted to investigate TCS dynamically responds to variations in landscape patterns. The results showed that the overall LULC structure on the QTP remained stable, with less than 1% of the plateau area undergoing changes over the past four decades. However, there were significant differences in conversion rates between different land types. Grasslands experienced the largest conversion, totaling 468 × 103 km2, primarily into unused land, forest, and water, accounting for 75.39%, 15.32%, and 7.67% of the total converted area. The spatiotemporal trends of the QTP landscape pattern were evident, showing increased diversity and fragmentation, characterized by intricate boundaries, reduced patch aggregation, and distinct vertical gradient variations with altitude. As elevation increases, landscape fragmentation, diversity, and evenness indices initially rise, followed by a subsequent decline. Significant changes were observed in the landscape metric of water, construction land, grassland, and unused land, while forests and cropland exhibited relatively minor fluctuations. Carbon storage services have declined over the past four decades, with significant spatial heterogeneity and a gradual decrease from southeast to northwest. The effect of landscape pattern changes on carbon storage services differed among LULC types, with AI, LPI, and AREA_MN positively correlating with carbon storage in forestland and grassland, while PD, SPLIT, and ED showed a negative relationship. The research provides theoretical guidance for optimizing LULC and landscape planning on the QTP, enhancing regional carbon storage services, and promoting sustainable development.

Data availability

All data presented in this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Englund, O., Berndes, G. & Cederberg, C. How to analyse ecosystem services in landscapes—A systematic review. Ecol. Indic. 73, 492–504. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2016.10.009 (2017).

Hao, R. et al. Impacts of changes in climate and landscape pattern on ecosystem services. Sci. Total. Environ. 579, 718–728. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.11.036 (2017).

Metzger, J. P. et al. Considering landscape-level processes in ecosystem service assessments. Sci. Total. Environ. 796, 149028. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.149028 (2021).

Alemu, J. B. et al. Identifying spatial patterns and interactions among multiple ecosystem services in an urban mangrove landscape. Ecol. Indic. 121, 107042. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2020.107042 (2021).

Reid, W. V. et al. Ecosystems and Human Well-Being-Synthesis: A report of the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (Island Press, 2005).

Renard, D., Rhemtulla, J. M. & Bennett, E. M. Historical dynamics in ecosystem service bundles. PNAS 112, 13411–13416. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1502565112 (2015).

Mengist, W., Soromessa, T. & Feyisa, G. L. Responses of carbon sequestration service for landscape dynamics in the Kaffa biosphere reserve, southwest Ethiopia. EIA Rev. 98, 106960. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eiar.2022.106960 (2023).

Gong, J. et al. Integrating ecosystem services and landscape ecological risk into adaptive management: Insights from a western mountain-basin area, China. J. Environ. Manag. 281, 111817. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2020.111817 (2021).

Morán-Ordóñez, A. et al. Ecosystem services provision by Mediterranean forests will be compromised above 2℃ warming. Global Change Biol. 27, 4210–4222. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.15745 (2021).

Dai, E., Lu, R. & Yin, J. Identifying the effects of landscape pattern on soil conservation services on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Glob Ecol. Conserv. 50, e02850. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gecco.2024.e02850 (2024).

Chen, L. et al. Mapping and analysing tradeoffs, synergies and losses among multiple ecosystem services across a transitional area in Beijing, China. Ecol. Indic. 123, 107329. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2020.107329 (2021).

Zhu, L., Zhu, K. & Zeng, X. Evolution of landscape pattern and response of ecosystem service value in international wetland cities: A case study of Nanchang City. Ecol. Indic. 155, 110987. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2023.110987 (2023).

Gilman, J. & Wu, J. The interactions among landscape pattern, climate change, and ecosystem services: Progress and prospects. Reg. Environ. Change. 23, 67. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-023-02060-z (2023).

Zhu, L. et al. Land use/land cover change and its impact on ecosystem carbon storage in coastal areas of China from 1980 to 2050. Ecol. Indic. 142, 109178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2022.109178 (2022).

Lv, H. Spatial and temporal variations of urban vegetation and soil carbon storage: a case study in Harbin. Ph.d, Northeast Institute of geography and Agroecology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Changchun (2017).

Li, Y. et al. Trends in total nitrogen concentrations in the Three Rivers Headwater Region. Sci. Total. Environ. 852, 158462. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.158462 (2022).

Hou, B. et al. Assessing forest landscape stability through automatic identification of landscape pattern evolution in Shanxi Province of China. Remote. Sens. 15(3), 545. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs15030545 (2023).

Kong, L. et al. Mapping ecosystem service bundles to detect distinct types of multifunctionality within the diverse landscape of the Yangtze River Basin, China. Sustainability 10(3), 857–873 (2018).

Ferrari, M. et al. Analysis of bundles and drivers of change of multiple ecosystem services in an Alpine region. J. Environ. Assess. Policy Manag. 18(04), 1650026 (2017).

Duarte, G. et al. The effects of landscape patterns on ecosystem services: meta-analyses of landscape services. Landscape Ecol. 33, 1247–1257 (2018).

Loudermilk, E. et al. Carbon dynamics in the future forest: the importance of long-term successional legacy and climate–fire interactions. Global Change Biol. 19(11), 3502–3515 (2013).

Zhang, M. et al. Increased forest coverage will induce more carbon fixation in vegetation than in soil during 2015–2060 in China based on CMIP6. Environ Res Lett. 17, 105002. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/ac8fa8 (2022).

Xia, M. et al. Spatio-temporal changes of ecological vulnerability across the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau. Ecol. Indic. 123, 107274. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2020.107274 (2021).

Chen, H. et al. Carbon and nitrogen cycling on the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 3, 701–716. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43017-022-00344-2 (2022).

Zhang, G. et al. Regional differences of lake evolution across China during 1960s–2015 and its natural and anthropogenic causes. Remote Sens. Environ. 221, 386–404. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rse.2018.11.038 (2019).

Liang, Y. & Song, W. Ecological and environmental effects of land use and cover changes on the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau: A bibliometric review. Land 11, 2163. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11122163 (2022).

Zhou, H. et al. Changes in the soil microbial communities of alpine steppe at Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau under different degradation levels. Sci. Total. Environ. 651, 2281–2291. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.09.336 (2019).

Zhao, Z. et al. Assessment of carbon storage and its influencing factors in Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Sustainability 10, 1864. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10061864 (2018).

Gao, M. et al. Increase of carbon storage in the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau: Perspective from land-use change under global warming. J. Clean. Prod. 414, 137540. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2023.137540 (2023).

Peng, F. et al. Changes of soil properties regulate the soil organic carbon loss with grassland degradation on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Ecol. Indic. 93, 572–580. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2018.05.047 (2018).

Harris, R. B. et al. Rangeland responses to pastoralists’ grazing management on a Tibetan steppe grassland, Qinghai Province, China. Rangeland J. 38, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1071/RJ15040 (2016).

Lü, F. & Yan, X. The three rivers source region alpine grassland ecosystem was a weak carbon sink based on BEPS model analysis. Remote. Sens. 14, 4795. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs14194795 (2022).

Li, T., Li, J. & Wang, Y. Carbon sequestration service flow in the Guanzhong-Tianshui economic region of China: How it flows, what drives it, and where could be optimized?. Ecol. Indic. 96, 548–558. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2018.09.040 (2019).

Huang, X. et al. Temporal and spatial dynamics of carbon storage in qinghai grasslands. Agronomy 12, 1201. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy12051201 (2022).

Huang, D. Z. et al. The spatial distribution and driving factors of carbon storage in the grassland ecosystems of the northern Tibetan plateau. J. Resources Ecol. 14, 893–902. https://doi.org/10.5814/j.issn.1674-764x.2023.05.001 (2023).

Cao, Z. et al. Increasing forest carbon sinks in cold and arid northeastern Tibetan Plateau. Sci. Total. Environ. 905, 167168. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.167168 (2023).

Qian, D. et al. Ecosystem services relationship characteristics of the degraded alpine shrub meadow on the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau. Ecol Evol. 13, e10351. https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.10351 (2023).

Zhang, Q. et al. The spatial granularity effect, changing landscape patterns, and suitable landscape metrics in the Three Gorges Reservoir Area, 1995–2015. Ecol. Indic. 114, 106259. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2020.106259 (2020).

Li, P. et al. Dynamic changes of land use/cover and landscape pattern in a typical alpine river basin of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau, China. Land Degrad. Dev. 32, 4327–4339. https://doi.org/10.1002/ldr.4039 (2021).

Liu, S. et al. Ecosystem Services and landscape change associated with plantation expansion in a tropical rainforest region of Southwest China. Ecol. Model. 353, 129–138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2016.03.009 (2017).

Hao, J. Y. et al. Temporal and spatial variations and the relationships of land use pattern and ecosystem services in Qinghai-Tibet Plateau, China. Ying Yong Sheng Tai Xue Bao 34(11), 3053–3063. https://doi.org/10.13287/j.1001-9332.202311.019 (2023).

Li, K. M. et al. Assessing the effects of ecological engineering on spatiotemporal dynamics of carbon storage from 2000 to 2016 in the Loess Plateau area using the InVEST model: A case study in Huining County, China. Environ. Dev. 39, 100641. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envdev.2021.100641 (2021).

Law, B. E. et al. Changes in carbon storage and fluxes in a chronosequence of ponderosa pine. Global Change Biol. 9(4), 510–524. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2486.2004.00866.x (2003).

Lang, W. G. et al. Phenological divergence between plants and animals under climate change. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 9(2), 261–272 (2025).

Norby, R. J. et al. Enhanced woody biomass production in a mature temperate forest under elevated CO2. Nat. Clim. Change 14(9), 983–988 (2024).

Chen, H. et al. Carbon and nitrogen cycling on the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 3(10), 701–716 (2022).

Zhang, B. & Zhou, W. Spatial–temporal characteristics of precipitation and its relationship with land use/cover change on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau, China. Land 10, 269. https://doi.org/10.3390/land10030269 (2021).

Cao, J. et al. Grassland degradation on the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau: reevaluation of causative factors. Rangeland Ecol. Manag. 72, 988–995. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rama.2019.06.001 (2019).

Wang, Y. et al. Grassland changes and adaptive management on the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 3, 668–683. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43017-022-00330-8 (2022).

Lam, N. S. N. et al. Effects of landscape fragmentation on land loss. Remote. Sens. Environ. 209, 253–262. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rse.2017.12.034 (2018).

Tao, H. et al. Research on medium and long term optimal operation of cascade hydropower stations on Tibet’s Lhasa River-Yarlung Zangbo River. IET Conf. Proc. 20, 263–273. https://doi.org/10.1049/icp.2024.4116 (2024).

Xu, B. et al. The transborder flux of phosphorus in the Lancang-Mekong River Basin: Magnitude, patterns and impacts from the cascade hydropower dams in China. J. Hydrol. 590, 125201 (2020).

Sarker, S. et al. Critical nodes in river networks. Sci. Rep. 9(1), 11178. https://doi.org/10.1038/41598-019-47292-4 (2019).

Lin, Z. P. et al. Upland river planform morphodynamics and associated riverbank erosion: Insights from channel migration of the upper Yarlung Tsangpo river. CATENA 231, 107280. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.catena.2023.107280 (2023).

Liu, H. et al. Assessing the dynamics of human activity intensity and its natural and socioeconomic determinants in Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Geo Sus. 4, 294–304. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geosus.2023.05.003 (2023).

Fan, F. et al. Scenario-based ecological security patterns to indicate landscape sustainability: A case study on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Landscape Ecol. 36, 2175–2188. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10980-020-01044-2 (2021).

Tang, Z. et al. Impacts of land-use and climate change on ecosystem service in Eastern Tibetan Plateau, China. Sustainability. 10, 467. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10020467 (2018).

Dadashpoor, H., Azizi, P. & Moghadasi, M. Land use change, urbanization, and change in landscape pattern in a metropolitan area. Sci. Total. Environ. 655, 707–719. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.11.267 (2019).

Guo, J. et al. Cultivated land area changes and driving forces in Tibet during 1978–2017. J. Yunnan Agricult. Univ. (Soc. Sci.) 14, 100–105. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1004-390X(s).201911045 (2020).

Hou, Y. Z. et al. Relationships of multiple landscape services and their influencing factors on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Landscape Ecol. 36, 1987–2005 (2021).

Xiao, Y. et al. Potential risk to water resources under eco-restoration policy and global change in the Tibetan Plateau. Environ. Res. Lett. 16(9), 094004 (2021).

Zhang, Y. Z. et al. Diversity patterns of cushion plants on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau: A basic study for future conservation efforts on alpine ecosystems. Plant Divers. 44(3), 231–242 (2022).

Yang, S. et al. Assessing land-use changes and carbon storage: A case study of the Jialing River Basin, China. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 15984. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-66742-2 (2024).

Duarte, G. T. et al. The effects of landscape patterns on ecosystem services: Meta-analyses of landscape srvices. Landscape Ecol. 33, 1247–1257. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10980-018-0673-5 (2018).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, Grant No. 72394401.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, J.L. and G.L.; methodology, J.L.; validation, J.L. and J.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, J.L.; writing—review and editing, J.L. and X.S.; visualization, J.L. and L.Z.; su-pervision, S.Z. and K.L.; project administration, J.L.; funding acquisition, G.L. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, J., Liu, G., Su, X. et al. Effects of pattern dynamics on carbon storage capacity in the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau from 1980 to 2020. Sci Rep 15, 23265 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-07392-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-07392-w