Abstract

Sodium magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is highly sensitive to cellular ionic balance due to tenfold difference in sodium concentration across membranes, actively maintained by the sodium–potassium (Na+-K+) pump. Disruptions in this pump or membrane integrity, as seen in neurological disorders like epilepsy, multiple sclerosis, bipolar disease, and mild traumatic brain injury, lead to increased intracellular sodium. However, this cellular-level alteration is often masked by the dominant extracellular sodium signal, making it challenging to distinguish sodium populations with mono- vs. bi-exponential transverse (T2) decays—especially given the low signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) even at an advanced clinical field of 3 Tesla. Here, we propose a novel technique that leverages intrinsic difference in T2 decays by acquiring single-quantum images at multiple echo times (TEs) and applying voxel-wise matrix inversion for accurate signal separation. Using numerical models, agar phantoms, and human subjects, we achieved high separation accuracy in phantoms (95.8% for mono-T2 and 72.5–80.4% for bi-T2) and demonstrated clinical feasibility in humans. This approach may enable early detection of neurological disorders and early assessment of treatment responses at the cellular level using sodium MRI at 3 T.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In human brains, sodium ions (Na+), when exposed to an electric field gradient of negatively charged macromolecules and proteins, experience nuclear quadrupolar interaction that results in biexponential decay in transverse (T2) relaxation of nuclear spins when ions are not in fast motion – a situation in which correlation time between sodium ions and electric field gradient is much shorter than the inverse of the Larmor frequency, τc < < 1/ω01,2. On the other hand, sodium ions in relatively fast motion cancel out the effect of quadrupolar interactions, resulting in mono-exponential T2 decay1,2,3,4. Historically, the short-T2 component of the biexponential decay was mis-considered arising from “bound” sodium5,6 as it was not detectable by then-NMR (nuclear magnetic resonance)1,2,3,4. The terminology of “bound sodium” however remains in use in today’s literature of sodium MRI, but it comes into question more recently7. For clarity, this article refers to the “bi-T2” sodium population as those ions showing biexponential T2 decay and “mono-T2” sodium population as those ions showing mono-exponential T2 decay. It is important to note that mono- and bi-T2 sodium ions can be present in both intra- and extracellular spaces8,9,10, dependent on relative correlation time with electric field gradient1,2.

Sodium (23Na) MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) currently acquires signals from both populations of sodium ions (mono- and bi-T2) and quantifies total sodium concentration (TSC) at each voxel. TSC is a unique MRI measure that taps ionic status in tissue and has the potential to non-invasively detect disruptions in ionic homeostasis present in a variety of conditions including stroke, tumor, demyelination, epilepsy, bipolar disorder, and mild traumatic brain injury8,9,10,11,12. However, TSC can be dominated by the mono-T2 sodium population in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) of a high sodium concentration (~ 145 mM) and overshadows alterations happening in the intracellular space of a much lower concentration (~ 15 mM), particularly in the gray matter due to its proximity to the brain CSF spaces. Separation of mono- and bi-T2 sodium signals would effectively remove the impact of CSF and more clearly depict intracellular alterations, especially at the early stage of a disease happening at the cellular level or in the early (cellular) response to a treatment.

The difference in T2 relaxation was extensively explored in sodium MRI to separate the two populations of sodium ions in the brain. Triple quantum filtering (TQF) in which magnetic resonance (MR) signals are generated solely from triple-quantum (TQ) transitions, was considered a standard for human studies13. TQF techniques, however, require multiple radiofrequency (RF) pulses for excitation and multi-step phase cycling to extract TQ signals and eliminate single-quantum (SQ) signals13,14,15,16,17, leading to long scan times (20–40 min) and high specific absorption rate (SAR)—the two major concerns about safety and practicality. More problematic is that the TQF signal has very low signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), about tenfold lower than the SQ15,16,17. These difficulties hamper translatable use of TQF in human subjects. Recent efforts relaxed the SAR concern by using two or even one RF pulse, but the low SNR issue remained24,52,53.

Alternative approaches have also been proposed. Inversion recovery (IR), adopted from proton (1H) MRI, exploits the difference in longitudinal (T1) relaxation between mono- and bi-T2 sodium ions, and attempts to suppresses signals from mono-T2 sodium of longer T1 time18,19,20. Such IR approaches require an additional RF pulse for the suppression, further compounding the SAR issue20,21, although adiabatic pulses are usually used. It also suffers from incomplete suppression of mono-T2 sodium signals due to spatial inhomogeneities of the B1+ field and from partial loss of the desired bi-T2 sodium signal due to incomplete recovery at the chosen inversion time. Incomplete suppression further complicates accurate quantification of bi-T2 sodium due to unknown residual mono-T2 sodium signals which is tenfold higher than bi-T2 sodium signal9,11,18. To overcome these drawbacks, another alternative approach, called the short-T2 imaging, was proposed in which SQ images were acquired at multiple echo times (TEs) and subtracted from each other to produce an image of the short-T2 component of bi-T2 sodium22,23,24,25. In such a way, SAR was reduced to, and SNR was increased to, the level of SQ images, favorable to human studies in clinic. Unfortunately, the subtraction could not eliminate completely mono-T2 sodium signal (~ 20% in residual signal), degrading accuracy of bi-T2 sodium quantification25.

In this study, the concept of the short-T2 imaging is generalized to multi-TE single-quantum (MSQ) imaging with more accurate matrix inversion replacing the subtraction to substantially improve accuracy of the separation between mono- and bi-T2 sodium signals. To develop the MSQ technique, we optimized TEs for data acquisition, investigated impact of T2 values on accuracy of the separation, and acquired free induction decay (FID) signals to generate a T2* spectrum for aiding the matrix equation. To test the MSQ technique, we implemented numerical simulations, phantom experiments, and human studies. The results are supportive of the proposed MSQ technique. We also itemized limitations of the MSQ technique and potential pitfalls in the interpretation of the separated sodium signals.

Results

Theoretical development

Model of sodium MRI signals

We use a two-population model, Eq. (1), to describe the single-quantum sodium image signal, m(t), evolving with time t at an imaging voxel ∆V. Time t = 0 is at the center of excitation RF pulse.

with \({m}_{mo}\) ≥ 0, \({m}_{bi}\) ≥ 0, and \({m}_{mo}+{m}_{bi}=m(0)\)

The \({m}_{mo}\) and \({m}_{bi}\) are signal intensity proportional to volume fraction \({v}_{q}\) and sodium concentration \({C}_{q}\), i.e., \({m}_{q}\) \(\propto \Delta V{v}_{q}{C}_{q}\) , q = mo and bi, for mono-T2 and bi-T2 sodium populations in a voxel ∆V, respectively. \(m(0)\) is total sodium signal intensity. \({Y}_{mo}\left(t\right)\) is the relaxation decay of the mono-T2 sodium with time constant \({T}_{2,mo}\) while \({Y}_{bi}\left(t\right)\) corresponds to the bi-T2 sodium with \({a}_{bs}=0.6\) for the short-T2 component \({T}_{2,bs}\) and \({a}_{bl}=0.4\) for the long-T2 component \({T}_{2,bl}\) . The ratio 0.6:0.4 in intensity of the bi-T2 sodium is from theoretical and experimental results for sodium nuclear spins in single molecular environment1,2,3,4 and is applicable to some types of biological tissues with multiple molecular environments, such as rabbit brains and kidneys5 and implanted brain tumors in rats26. The values of T2 are in an order of \({T}_{2,bs}\)<< \({T}_{2,bl}\) ≤ \({T}_{2,mo}\). However, Eq. (1) doesn’t include mono-T2 sodium with a short T2 value.

Separation of mono- and bi-T2 sodium signals

We then found a solution to Eq. (1) and separated the mono- and bi-T2 sodium signal intensities, \({m}_{mo}\) and \({m}_{bi}\). Given SQ sodium images at multiple echo times, TEs = {TE1, TE2, …, TEN}, in which TE is defined as time interval between the center of excitation RF pulse and center of the k-space, Eq. (1) becomes a matrix equation below.

where the superscript T is operator for matrix transpose. A solution to Eq. (2) is given in Eq. (3) via an established algorithm called non-negative least-squares (NNLS)27 in which the non-negative condition on X is incorporated into the solution.

We summarized this solution, called the MSQ approach, into a flowchart in Fig. 1. The inputs are multi-TE sodium images and an FID signal. The outputs are mono-T2, bi-T2, and total sodium images, as well as maps of field inhomogeneity ∆B0 and single-term exponential fitted effective T2 (called T2*)—single-T2* for short. Hereinafter, T2* replaces T2 as spin echo is not favorable to sodium MRI. Motion correction (MoCo) across multi-TE images is optional. Also optional is the low-pass (LP) filtering, which is a 3D averaging over a volume of 3 × 3 × 3 voxels for instance, to reduce random noise on the bi-T2 sodium images. The ∆B0 and single-T2* maps represent spatial distributions of the B0 field inhomogeneity and the short- and long-T2* components, providing indications for uncertain short-T2* decays possibly caused by B0 inhomogeneity. Such maps are complimentary but critical to quantification and interpretation of the separated mono- and bi-T2 sodium signals.

Flowchart of the MSQ sodium MRI. Input multi-TE SQ images m(TE) and an FID signal producing T2* spectrum. Motion correction (MoCo) between SQ images is optional. Separation voxel-wise matrix inversion. Output three sodium images, i.e., mono-T2 as mmo, bi-T2 as mbi, and total as mmo + mbi . The low-pass (LP) filtering (optional) is a 3D smoothing of size 3 × 3 × 3 or others, to further reduce random noise. Additional outputs the maps of B0 inhomogeneity and single-T2*.

Technical development

Optimization of the number of TEs

In principle, the more TEs the better differentiation between T2* relaxations of the mono- and bi-T2 sodium populations. In practice, the number of TEs is restricted by total scan time (TA), SNR, signal decay, and risk of motion across TEs. Therefore, a trade-off must be made for the number of TEs. To determine an optimal number of TEs, it is necessary to understand noise propagation in Eq. (2). We applied singular value decomposition (SVD) analysis28 to the matrix Y in Eq. (2) and got Eq. (4)

Singular values (\({\sigma }_{1}\)≥ \({\sigma }_{2}\)≥0) determine noise transfer (amplification or suppression) in Eq. (4b) from the measured TE-images M to the separated mono- and bi-T2 sodium images X. However, Eq. (4b) allows negative values in X when random noise contaminates M. This violates the “non-negative” condition on X. Therefore, the SVD analysis is applicable only to X elements with SNR ≥ 2 where the elements, with Gaussian noise, have 95.4% of chance in the territory of non-negative value29.

The simulations were implemented via Eq. (4) for three cases: an idea case serving as reference, practical case 1 having a large number of TEs, and practical case 2 having a small number of TEs. The idea case has 80 TEs, i.e., TE = (0, 1, 2,…, 79) ms, to cover entire range of the T2* decays. The two practical cases, based on our extensive experience on human studies18,23,25,45, have total scan time limited to 22 min for 8 TE-images, 2.66 min for each TE-image; and the distribution of TEs was chosen such that it was most sensitive to T2* decays2345. Thus, the case 1 had 8 TEs, i.e., TE = (0.5, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 7, 10) ms, while the case 2 only has two TEs, i.e., TE = (0.5, 5.0) ms but four averages at each TE. The 4-averages lead to a reduction in random noise standard deviation (SD), or an increase in SNR, by a factor of 2 in the case 2 relative to case 1. The optimal set of TEs is identified as the one that has a \({\sigma }_{2}\) value producing minimum amplification of random noise in the separated mono- and bi-T2 sodium images.

Figure 2 presents the results at a typical set of T2* values, {\({T}_{2,mo}^{*}\), \({T}_{2,bs}^{*}\), \({T}_{2,bl}^{*}\)} = {50.0, 3.5, 15.0} ms. Singular value σ2 is less than 1.0 for the 8-TE and 2-TE cases, leading to a noise amplification. Therefore, a better choice for less noise amplification is the 2-TE case, in which TE2 at 5 ms produced a value near maximum of σ2 while preserving higher signal than larger TE2. Thus, the 2-TE scheme was selected for our studies.

Optimization of TE sampling scheme. (A) A reference sampling scheme of 80 TEs in a range of 0–79 ms at an interval of 1.0 ms, distributing on a mono-exponential T2* decay Ymo (TE) of mono-T2 sodium at a typical value of T2*mo = 50 ms, and on a bi-exponential T2* decay Ybi (TE) of bi-T2 sodium at a typical set {T2*bs, T2*bl} = {3.5, 15.0} ms. (B) The 8-TE case at TE = {0.5, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 7, 10} ms, distributing on the decay curves Ymo and Ybi. (C) The 2-TE case at TE = {0.5, 5} ms. (D) SVD singular values (σ1 and σ2) of the three sampling schemes. σ2 is less than 1.0 at both 8- and 2-TE schemes but the 2-TEs (arrow) leads to less noise amplification when using four averages. (E) Singular values of the 2-TE scheme changing with TE2 at 5 ms (arrow) produced a value near maximum for σ2 while preserving higher signal than the larger TE2. Collectively, the 2-TEs scheme is an optimal one for the human brain.

Impact of T2* values on the separation

Intuitively, the solution {\({m}_{mo}\), \({m}_{bi}\)} to Eq. (1) is not sensitive to T2* values due to exponential decays in Eqs. (1a,b). This observation can be verified theoretically and numerically. Theoretically, small changes in T2* values, {\(\delta {T}_{2,q}^{*}\), q = mo, bs, bl}, lead to small changes {\(\delta {m}_{p}\), p = mo, bi} in \({m}_{mo}\) and \({m}_{bi}\) under the same m(t), that is.

where \(\delta\) is difference operator. Numerically, errors in \({m}_{mo}\) and \({m}_{bi}\) can be calculated, given a series of {\({T}_{2,q}^{*}\), \(\delta {T}_{2,q}^{*}\); q = mo, bs, bl} at a specific pair (\({m}_{mo}\), \({m}_{bi}\)). This creates a plot showing how {\({m}_{mo}\), \({m}_{bi}\)} changes with {\(\delta {T}_{2,q}^{*}\); q = mo, bs, bl}.

Figure 3 shows two extreme cases: mono-T2 sodium dominating at \({m}_{mo}\) = 0.9 and bi-T2 sodium dominating at \({m}_{bi}\) = 0.9. In Fig. 3a, an error in \({T}_{2,mo}^{*}\) causes an error in \({m}_{mo}\) or \({m}_{bi}\) much smaller for the dominant one, e.g., \({\delta m}_{bi}\)< 2.2% when \({\delta T}_{2,mo}^{*}\)< 20%, and \({\delta m}_{mo}\) < 2.9% when \({\delta T}_{2,mo}^{*}\)< 5.0%. In Fig. 3b, an error in \({T}_{2,bs}^{*}\) has a small impact on both \({m}_{mo}\) and \({m}_{bi}\), e.g., when dominating, \({\delta m}_{bi}\)< 4.8% and \({\delta m}_{mo}\)< 0.04% when \({\delta T}_{2,bs}^{*}\) < 20%. In Fig. 3c, an error in \({T}_{2,bl}^{*}\) leads to an error in \({m}_{mo}\) or \({m}_{bi}\) much smaller for the dominant one, e.g., \({\delta m}_{bi}\)< 5.2% and \({\delta m}_{mo}\)< 0.6% when \({\delta T}_{2,bl}^{*}\) < 20%. The best case is Fig. 3b where \({T}_{2,bs}^{*}\) has small impact (< 4.9%) on both mono- and bi-T2 sodium signals. The worst case is Fig. 3a (top) where \({T}_{2,mo}^{*}\) had a large impact on bi-T2 sodium signal, \({\delta m}_{bi}\)= 35.6% when \({\delta T}_{2,mo}^{*}\) = − 5%. In other words, when the mono-T2 sodium is very dominating, \({T}_{2,mo}^{*}\) value should be as accurate as possible (achievable via single-T2* map) to attain the best separation for the bi-T2 sodium.

Impact of T2* values on the separation of mono- and bi-T2 sodium signals (mmo, mbi) at {T2*mo, T2*bs, T2*bl} = (50.0, 3.5, 15.0) ms for two extreme cases: mono-T2 sodium dominating (top row), mmo = 0.9, and bi-T2 sodium dominating (bottom row), mbi = 0.9. (A) Error in T2*mo. (B) Error in T2*bs. (C) Error in T2*bl.

Testing on numerical and physical models

Numerical models

We first tested the separation of mono- and bi-T2 sodium signals on numerical models via Eq. (2) at a typical set of T2* values, (\({T}_{2,mo}^{*}\), \({T}_{2,bs}^{*}\), \({T}_{2,bl}^{*}\)) = (50.0, 3.5, 15.0) ms, and an optimal two-TE scheme, TE = (0.5, 5.0) ms. Sodium image signals were calculated via Eq. (1), with an additive Gaussian noise, \(N(0,{\sigma }^{2})\), at each of noise trials (independent from each other), \(m\left(t)+n(t\right)\). The mono- and bi-T2 signal intensities {\({m}_{mo}\), \({m}_{bi}\)} vary in a normalized range of 0.1–0.9 at a step size = 0.1. The separation was implemented using the function lsqnonneg() in MATLAB, and repeated Nnoise times at each of the specific intensity. Mean and standard deviation (SD) were reported as the separated sodium signal. Nnoise = 1054 was chosen to detect a 10% of SD, or 0.1 effect size d = Δμ/SD, in difference between the mean and true value at 90% power and 5% significant level under the two-sided Student’s t-test29. Figure 4 demonstrates the simulated separation at three SNRs of interest: 100 (extra-high), 50 (high), and 25 (regular). The SD (error bar) consistently decreased with SNR increasing. There were underestimates (3.9–5.6%) in \({m}_{mo}\) and \({m}_{bi}\) near maximum value 1.0 but overestimates (4.2–5.5%) near minimum value 0.0, with the amount decreasing with SNR increasing.

Simulated separation of the mono- and bi-T2 sodium signals. (A) Extra-high SNR = 100. (B) High SNR = 50. (C) Regular SNR = 25. The SD (error bar) of the separated mmo (top) and mbi (bottom) consistently decreases with SNR increasing from 25 to 100, with an underestimate (arrow) for mmo or mbi near maximum value 1.0 but an overestimate (arrow) near minimum value 0.0. The amount decreases with SNR increasing.

Physical models

We then tested the separation on four physical models (phantoms) with known sodium concentrations. These phantoms were custom-built and described in our previous publications25,30. They are 50-mL centrifuge tubes filled with a mixture of distilled water, 10% w/w agar powder, and sodium chloride (NaCl) at three concentrations of 90, 120, and 150 mM and at 150 mM without agar, to mimic bi- and mono-T2 sodium signals in human brains. Sodium MRI was performed on a clinical MRI scanner at 3 T (MAGNETOM Trio Tim, Siemens Medical Solutions, Erlangen, Germany) with a dual-tuned (1H-23Na) volume head coil (Advanced Imaging Research, Cleveland, OH). The data acquisition was implemented using an SNR-efficient, three-dimensional (3D) pulse sequence called twisted projection imaging (TPI)31.

Figure 5 summarizes outcomes of the phantom studies30. The separation in Fig. 5h recovered 95.8% of mono-T2 sodium signal in the saline water tube, while leaving 4.2% to bi-T2 sodium signal, much better than 20% left by the subtraction approach25. The separation recovered 72.5, 80.4, and 75.9% of bi-T2 sodium signal in the agar tubes at sodium concentrations of 150, 120, and 90 mM, respectively. The quantification of sodium concentration in Fig. 5i, when calibrated at the saline water, showed a systematic bias in total and bi-T2 sodium concentrations, leading to an underestimate of sodium concentrations.

Phantom study. (A) Phantoms of four tubes with sodium concentration: 150 mM for the saline water simulating mono-T2 sodium ions and 90, 120, 150 mM for the agar gels simulating bi-T2 sodium ions. (B) Sodium images of the phantoms at TE1/TE2 = 0.5/5 ms, shown in the same window/level. (C) FID signals (original and fitted) from the four tubes (no averaging), with the correction for distortion at the first five data points. (D) Residual error of the fitting in C. (E) T2* spectrum calculated from the FID in C and used to produce the fitted FID. (F) Sodium images (total, mono-T2, and bi-T2) separated from the two images in B at (T2*mo, T2*bs, T2*bl) = (50, 5, 25) ms according to E and G. (G) Maps of ∆B0 and single-T2* calculated from the images in B, and a map of SNR at TE = 0.5 ms. (H) Separated sodium signals in the regions of tubes in F. (I) Quantified sodium concentration from F.

Testing on humans

To demonstrate feasibility of the proposed MSQ approach at clinical field strength of 3 Tesla, we conducted the human study on 15 subjects including nine healthy adults (age 39.6 ± 21.4 years in a range of 21–74 years; 3 males and 6 females) and six patients with different neurological conditions (1 bipolar disorder, 3 epilepsy, 1 multiple sclerosis, and 1 mild traumatic brain injury; age 30.5 ± 15.1 years in a range of 18–59 years; 3 males and 3 females), after the exclusion of one healthy subject and one patient due to motion between the two TE-images. The MSQ sodium MRI was performed on a clinical 3 T MRI scanner (Magnetom Prisma, Siemens Healthineers, Erlangen, Germany) with a custom-built 8-channel dual-tuned (1H-23Na) head array coil32.

T2* values in whole brain of the study subjects

The MSQ approach needs an input of {\({T}_{2,mo}^{*}\), \({T}_{2,bs}^{*}\), \({T}_{2,bl}^{*}\)} at each voxel ∆V in the field of view (FOV). To measure these values is time consuming (~ 2 h) and impractical in clinical routine. Alternatively, we proposed to use a global set of these values for all voxels. This global set can be measured quickly (< 1 min) on whole brain of each study subject by acquiring FID signal s(t) and fitting to it with multi-term exponential T2* decays to attain a T2* spectrum through Eq. (6).

To confirm the validity of such alternative approach, we acquired FID signals on all the 15 subjects. Figure 6 demonstrates two such FID signals and T2* spectra from a healthy young subject (21 years old, male, Fig. 6a) and a patient with epilepsy (31 years old, male, Fig. 6b). The spectra are sparse with just 2–4 peaks, indicating that the global set of {\({T}_{2,mo}^{*}\), \({T}_{2,bs}^{*}\), \({T}_{2,bl}^{*}\)} is a reasonable estimate for the separation. We also observed that these T2* values however are different from subject to subject as shown in the two-dimensional (2D) scatter plot (Fig. 6c). The short-T2* component is clearly crowded in a range of 1–5 ms while the long-T2* is widely scattered in three bands centered at 10, 20, and 30 ms, respectively. Interestingly, the long-T2* component is shifted to lower values in the patient group, relative to the healthy group, potentially due to micro magnetic environment altered in the patients. There seems no difference between males and females in the healthy group.

Human study: individual T2* components in whole brain across all the 15 study subjects. (A) A typical T2* spectrum and associated FID signal and fitting error from whole brain of a healthy young subject (21 years old, male). (B) Another example from a patient with epilepsy (31 years old, male). (C) Scatter plot of individual T2* components.

Healthy subjects and patients

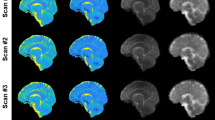

We presented here two representative cases of the 15 human subjects: a healthy young subject (26 years old, female) in Fig. 7 and a mid-aged patient with self-reported bipolar disorder (59 years old, male) in Fig. 8. The other cases are available to readers under the data availability conditions.

Human study #1 (26-year-old female, healthy). (A) 3D sodium images of the brain in three orthogonal slices at TE1/TE2 = 0.3/5 ms. (B) FID signal of whole brain and the associated fitting error and T2* spectrum. (C) Separated sodium images from the 2-TE images in A using (T2*mo, T2*bs, T2*bl) = (50.0, 6.0, 19.0) ms according to peaks in B. (D) Inverse-contrast display to highlight areas of low intensity. All the images in A and C were displayed using the same window/level. (E–G) Maps of SNR, ΔB0, and single-T2*, calculated from the 2-TE images in A.

Human study #2 (59-year-old male, patient with bipolar disorder). (A) 3D sodium images of the brain at TE1/TE2 = 0.3/5 ms. (B) FID signal of whole brain and the associated fitting error and T2* spectrum. (C) Separated sodium images from the 2-TE images in A using (T2*mo, T2*bs, T2*bl) = (50.0, 2.5, 7.0) ms according to the peaks in B. (D) Inverse-contrast display to highlight areas of low intensity. All the images in A and C were displayed using the same window/level, except bi-T2 sodium where W/L was halved. (E–G) Maps of SNR, ∆B0, and single-T2*, calculated from the 2-TE images in A. Note that the bi-T2 sodium images in C highlight possible regions (arrows) of elevated bi-T2 sodium concentration in the parenchyma.

Figure 7 indicates that signals from CSF in the brain were effectively separated into mono-T2 sodium image (Fig. 7c or d), while signals from brain tissues such as gray and white matters were mostly contained in the bi-T2 sodium image (Fig. 7c or d). Notably and not surprisingly, signal intensity across brain tissues looks more uniform in the bi-T2 sodium images than in the mono-T2 sodium images (Fig. 7c), total sodium images (Fig. 7c), or TE1-images (Fig. 7a), which is in consistency with the knowledge that the bi-T2 sodium ions are mainly located in intracellular space of the brain tissues with a normal concentration of about 15 mM5,26. SNR in Fig. 7e is ≥ 25 in most regions of the brain, ensuring a robust separation as suggested in the simulations (Fig. 4). The field inhomogeneity ∆B0 in Fig. 7f varied between ± 20 Hz across the brain, with the largest off-resonance in the prefrontal and occipital lobes, leading to visible blurring of the tissues in the bi-T2 sodium images (Fig. 7c or d, sagittal). The single-T2* map in Fig. 7g provides a spatial distribution of short and long T2* components across the brain, complementary to T2* spectrum in Fig. 7b. It also indicates that majority of the long T2* components are in the prefrontal lobe in this case (Fig. 7g, sagittal).

Figure 8 shows potential benefits from the bi-T2 sodium images of patients with neurological disorders such as bipolar disorder which is known to cause abnormally high intracellular sodium concentration in the brain, but locations are hard to define33,34. The bi-T2 sodium images (Fig. 8c or d) clearly highlighted brain regions of an elevated bi-T2 sodium signal against surrounding tissues, with a ratio of 1.78 vs. 1.40 (or 27.1% increase) before the separation (Fig. 8c). These regions have no visible contrast in the total or TE1-images (Fig. 8a or c). SNR in these regions is > 40 (Fig. 8e), supporting a robust separation. The field inhomogeneity ∆B0 in these regions is low (< 5 Hz, Fig. 8f), excluding field-induced artifacts. Single-T2* map in Fig. 8g shows abnormally low T2* values in the regions, confirming an increase in short-T2* components.

Validation via the estimates of upper limit for extra- and intracellular volume fractions

The human studies, different from the phantom studies above where the ground truth of sodium concentrations is known, lack the ground truth for validation. Although each step in the MSQ separation is scientifically reasonable and its outcome should be believed correct, we alternatively and indirectly validate it by applying the separated sodium images to estimation of the upper limit of extra- and intracellular volume fractions for which accurate measurements are available in literatures8,26,35,36. To that goal, we assigned all mono-T2 sodium to extracellular space and all bi-T2 sodium to intracellular space, although they may co-exist in both extra- and intracellular spaces. The estimates (mean and SD) were made in the regions of interest (ROIs) of gray matter (GM) and white matter (WM) across three continuous slices via Eqs. (7–9) using sodium concentrations \({C}_{ex}\)=145 mM for extracellular space and \({C}_{in}\)=15 mM for intracellular space.

Figure 9 presents the upper-limit estimates in the healthy (N = 9) and patient (N = 6) groups. The healthy group shows significant (P = 0.023) difference in volume fraction between the gray and white matters: 89.6 ± 4.5 vs. 94.0 ± 2.6% for intracellular space, in line with the literatures of 75 vs. 92%8,26; and 10.4 ± 4.5 vs. 6.0 ± 2.6% for extracellular space, comparable to literatures of 14.1 ± 1.835 vs. 18 ± 5%36. There’s no significant difference (P = 0.953) between the healthy and patient groups.

Estimates of upper limit of the volume fraction for extra- and intracellular spaces. (A) Typical sodium images (total, mono-T2, and bi-T2) and ROIs for the gray matter (GM) and white matter (WM) in an axial slice from a healthy subject. (B) Volume fractions for the healthy group (N = 9), and (C) for the patient group (N = 6).

Discussion

We presented here a new technique, MSQ, that simply separates the mono- and bi-T2 sodium signals with high accuracy offered by voxel-wise matrix inversion (Fig. 1). The MSQ approach leverages intrinsic difference in T2 relaxation between the two sodium populations (Figs. 7, 8). The 2-TE sampling scheme stands out for smaller noise transfer during the separation (Fig. 2). The T2* spectrum of whole brain has sparse peaks and confirms a global set of T2* values {\({T}_{2,mo}^{*}\), \({T}_{2,bs}^{*}\), \({T}_{2,bl}^{*}\)} applicable to humans (Fig. 6). The measurement of T2* spectrum facilitates fine tuning of the global set of T2* values towards individual subjects with diverse T2* relaxations in the brain (Figs. 7, 8). However, a global set of T2* values may not be plausible in such situations where T2* in an individual brain has substantial spatial variation37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44, multi-regional sets, or a linear combination of them, may be applied to the separation.

This paper outlines a novel method for sodium signal separation and, of note, does not detail subsequent quantification of sodium concentrations of the two sodium populations after separation. Such quantification involves further procedures including calibration to sodium concentration from signal using different strategies such as external phantoms or internal regions like ventricles and vitreous humors and corrections for inhomogeneous coil sensitivity including the RF fields of B1+ and B1−. These procedures merit further study.

Limitations of the MSQ approach are important to understand when applying them. First, the method assumes a two-population model exhibiting mono- and bi-T2 decay behaviors. Theoretically, this could be a problem if, for example, there is no bi-T2 signal at all but rather two mono-T2 sodium decays of different T2* values within the same voxel; these components would be mathematically combined and then falsely created as what appears to a bi-T2 sodium population. This error stems from the fact that the described separation is based on a mathematical model, rather than the physical model as the TQF approaches are based on. To minimize this kind of false positive errors, the NNLS algorithm, rather than the analytical one, is required to solve the matrix Eq. (2) under the non-negative constrains although it takes longer time in computation.

The second limitation may occur at voxels filled solely with mono-T2 sodium of very small T2* values, such as regions in the paranasal sinuses (Figs. 7c and 8c). Such areas may mislead the MSQ to produce pseudo bi-T2 sodium. Any such mis-separated regions can be readily identified by cross-referencing the maps of ∆B0 and single-T2* (Figs. 7 and 8).

The third limitation is potential underestimation of bi-T2 sodium signal caused by the image at TE1, as illustrated in the phantom studies (Fig. 5). The separation in Eq. (2) assumes TE1-image intensity precisely at TE1 (i.e., a very short readout time). Actual TE1-image intensity is an average over readout time during which short-T2* components decay significantly when readout is relatively long (e.g., Ts = 36.32 ms, which is about ten times longer than the short-T2* of 3 ms seen in this study). Therefore, the extent of underestimation depends on readout time or pulse sequence. To mitigate this problem, two strategies may be applicable. One is to replace TE1 in Eq. (2) with an effective (larger) value accounting for short-T2* decay during readout. The other is to shift \({T}_{2,bs}^{*}\) to a larger value, as did in a previous work on phantoms30. Alternatively, correction for such underestimation could be integrated into calibration process when quantifying sodium concentration (Fig. 5).

Materials and methods

Experimental design

The objective of this study is to demonstrate the feasibly of the proposed MSQ approach to separate mono- and bi-T2 sodium signals in brain tissues of human subjects at a clinical field strength of 3 Tesla. We designed three types of experiments: numerical simulations, phantom experiments, and human subject studies. To implement the MSQ approach, we used a clinical MRI scanner at 3 Tesla for data acquisition and a custom-developed software package for data processing.

Calculation of the separation sensitivity to T2* values

We used the most common set of T2* values from our human studies, {\({T}_{2,mo}^{*}\), \({T}_{2,bs}^{*}\), \({T}_{2,bl}^{*}\)} = {50.0, 3.5, 15.0}ms, as true values, and calculate via Eqs. (1–3) the separation error {\({\delta m}_{mo}\), \(\delta {m}_{bi}\)} relative to the ground truth of mono- and bi-T2 sodium signals {\({m}_{mo}\), \({m}_{bi}\)} when adding errors \(\delta {T}_{2,q}^{*}\), q = mo, bs, bl, up to ± 20% to the true T2* values. The relationship between {\(\delta {T}_{2,q}^{*}\); q = mo, bs, bl} and {\({\delta m}_{mo}\), \(\delta {m}_{bi}\)} was plotted out in Fig. 3. To focus on the relation of “\(\delta {T}_{2}^{*}-\delta m\)”, TEs were sampled in an ideal case with TE0 = 0, ∆TE = 1.0 ms, and 80 TEs covering entire T2* decays.

Numerical simulation

These simulations were performed in MATLAB on a MacBook Pro laptop or Windows desktop, otherwise specified. Random noise of Gaussian distribution was generated using MATLAB function randn(n), while the NNLS algorithm was implemented using [x, resnorm, residual] = lsqnonneg(C, d).

Phantom experiments

MRI data acquisition was implemented using the TPI sequence31 with parameters: rectangular RF pulse duration = 0.8 ms, flip angle = 80º (limited by SAR and TR), field of view (FOV) = 220 mm, matrix size = 64, nominal resolution = 3.44 mm (3D isotropic), TPI readout time = 36.32 ms, total TPI projections = 1596, TPI p-factor = 0.4, TR = 100 ms, TE1/TE2 = 0.5/5 ms, averages = 4, and TA = 10.64 min per TE-image. The sodium images were offline reconstructed on a desktop computer (OptiPlex 7050, 8 GB memory, Windows 10, DELL, Round Rock, TX) using the gridding algorithm47,48 and a custom-developed programs in C++ (MS Visual Studio 2012, Microsoft, Redmond, WA). The mono- and bi-T2 sodium signals was separated using a custom-developed program in MATLAB as described below.

Clinical MRI scanner for data acquisition

The sodium MRI images and FID signals were acquired on two 3 T clinical MRI scanners for the phantom experiments and human studies, respectively. One was MAGNETOM Trio Tim (Siemens Medical Solutions, Erlangen, Germany) with a dual-tuned (1H-23Na) volume head coil (Advanced Imaging Research, Cleveland, OH) and used for the phantom experiments. The other was MAGNETON Prisma (Siemens Healthineers, Erlangen, Germany) with a custom-built 8-channel dual-tuned (1H-23Na) head array coil32 and used for human studies.

Software for data processing and image display

We developed a software (code) called SepMoBi in MATLAB (R2021a, MathWorks, Natick, MA) on a laptop computer (MacBook Pro, 16 GB memory, Apple M1 chip, Apple Inc., Cupertino, CA), and used it for data processing, including the calculations of T2* spectrum, mono- and bi-T2 sodium images, and maps of SNR, ∆B0 and single-T2*. In addition, we used software MRView (MRI Research, Mayo Clinic and Foundation, December 2020) for image display and parameter calculation in ROIs (Fig. 9).

Pre-processing of FID signals

When acquired with an array coil, FID signals may have unique initial phases {\({\varphi }_{0,l}\), l = 1, 2,…, Nc} at individual elements, and need to be aligned to produce a resultant FID signal. Alignment (via phase correction) can be towards a reference phase such as zero phase, one of the initial phases, or mean phase across elements. In addition, signal intensity at individual elements needs to be scaled using “FFT factor” stored in the header of a raw FID data file, for instance.

FID signals at the first few samples are distorted by hardware filtering during analog-to-digital conversion (ADC). The number of affected samples are in a range of 3–10 points, dependent on sampling bandwidth, with the first sample having the largest distortion. This distortion alters measurement of T2* components, especially the short T2* components which are critically important to the bi-T2 sodium. Correction for the distortion can be performed using an established exponential extrapolation (see Supplementary Information).

Global T2* spectrum

We measured FID signals on clinical 3 T MRI scanners using a product pulse sequence, either AdjXFre embedded in manual shimming or independent fid_23Na, with acquisition parameters: TE = 0.35–1.0 ms, TR = 100–300 ms, and averages = 1–128, and TA = 0.2–39 s. After the pre-processing described above, resultant FID signals are curve-fitted to Eq. (6) using the NNLS algorithm27 when T2* values are pre-distributed in a range of interest [T2*min, T2*max] at uniform or non-uniform intervals {\({\Delta T}_{2,j}^{*}, j=1, 2, \dots\)}. Amplitudes {\({A}_{j}\)}, called T2* spectrum, determine relative incidence of T2* components in an imaging volume which counts all T2* components from both mono- and bi-T2 sodium populations. We used a uniform interval of \({\Delta T}_{2}^{*}\) = 0.5 ms in a range of interest 0.5–100 ms for a high resolution of T2* values. Assignment of the peaks in the T2* spectrum to {\({T}_{2,mo}^{*}\), \({T}_{2,bs}^{*}\), \({T}_{2,bl}^{*}\)} was based on their relative positions of \({T}_{2,mo}^{*}\) ≥ \({T}_{2,bl}^{*}\) > > \({T}_{2,bs}^{*}\) and intensity ratio about 6:4 for the bi-T2 sodium. Robustness of the T2* measurement including data acquisition and spectrum computation is addressed in the Supplementary Information. In case of missing \({T}_{2,mo}^{*}\) peak in the T2* spectrum representing cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), use the single-T2* map to determine the value of \({T}_{2,mo}^{*}\) by calculating the mean value in a region filled with pure CSF in the ventricles or with pure fluid in the vitreous humors.

Human studies

The human studies were approved by local Institutional Review Board (IRB) at New York University Grossman School of Medicine, New York, NY, USA, and performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. Informed consent was obtained from each of the study subjects. For data acquisition, the same TPI pulse sequence was used as in the phantom studies. Sodium images were reconstructed off-line using the gridding algorithm47,48, channel by channel, and combined into a resultant image via the sum-of-squares (SOS) algorithm49. To decouple random noise across channels, an orthogonal linear transform (detailed in Ref.46) was performed in which physical channel data were transformed into virtual channels with random noise independent from channel to channel. This decoupling and denoising process also normalized signal amplitudes across channels by dividing noise standard deviation. Separation of the mono- and bi-T2 sodium signals was then implemented in the same way as in the phantom studies.

Mapping of ∆B0 and single-T2*

To map ∆B0 or ∆f0 (= γ∆B0/2π), Hermitian product method50 was performed via Eqs. (10–12) at individual imaging voxels to calculate phase differences \(\left\{{\Delta \varphi }_{i}, i=1, 2, \dots , N-1\right\}\) between TEs \(\{{TE}_{i}, i=1, 2, ..., N\}\). Image amplitude at individual channels were corrected with the scale factors \(\left\{{w}_{l}, l=1, 2, ..., {N}_{c}\right\}\). Phase unwrapping was not performed due to small intervals in the TEs and, in general, small inhomogeneity in B0 field in sodium MRI. Computation for ∆B0 map is fast (0.078 s) on a Mac laptop computer for images of matrix size 64 × 64 × 64 at two TEs.

To map single-T2*, a MATLAB curve-fitting function fit(x, y, ‘exp1’) was used to calculate single-T2* values at each voxel via Eq. (13). A restriction (T2*max < 100 ms) was enforced to exclude unreasonable values caused by random noise. The computation time is acceptable (10min17s).

Calculation of signal-to-noise ratio (SNR)

In a region of interest (ROI), SNR was calculated via Eq. (14) in a simplified way for both volume and array coils by taking the ratio of mean intensity S in a ROI to noise standard deviation (SD) in noise-only background regions. A factor of 0.655 was applied to noise SD to account for Rician distribution in magnitude images51. For SNR mapping, pixel signal is used in the calculation.

Statistical analysis

A regular statistical significance (P = 0.05) was applied to the comparisons, via Student’s t-test, between the two sets of data in this work. Minimum sample size for the t-test is 16, with 80% power, 5% significance level, two-sided test, and 1.0 effect size29.

Conference presentation

This work was partially presented in the 25th Annual Meeting of ISMRM 2017, Honolulu, Hawaii, USA.

Preprint

A previous version of this manuscript was published as a preprint [https://arxiv.org/abs/2407.09868].

Data availability

Upon written request to the correspondence author, Yongxian Qian, PhD, all data (sodium images and FID signals) and codes used in this work (main text and supplementary materials) are available to any researcher solely for scientific research purposes.

References

Hubbard, P. S. Nonexponential nuclear magnetic relaxation by quadrupole interaction. J. Chem. Phys. 53, 985–987 (1970).

Jaccard, G., Wimperis, S. & Bodenhausen, G. Multiple-quantum NMR spectroscopy of S=3/2 spins in isotropic phase: A new probe for multiexponential relaxation. J. Chem. Phys. 85, 6282–6293 (1986).

Shporer, M. & Civan, M. M. Nuclear magnetic resonance of sodium-23 linoleate-water: Basis for an alternative interpretation of sodium-23 spectra within cells. Biophys. J. 12, 114–122 (1972).

Andrasko, J. Nonexponential relaxation of 23Na+ in agarose gels. J. Magn Reson. 16, 502–504 (1974).

F. Cope, NMR evidence for complexing of Na+ in muscle, kidney, and brain, and by actomyosin. The relation of cellular complexing of Na+ to water structure and to transport kinetics. J. Gen. Physiol. 50, 1353–1375 (1967).

Sterk, H. & Schrunner, H. On the discrimination of bound and mono-T2 sodium ions in solutions of biomolecules by means of the T1 relaxation. J. Mol. Liq. 30, 1781–2183 (1985).

Burstein, D. & Springer, C. S. Jr. Sodium MRI revisited. Magn. Reson. Med. 82, 521–524 (2019).

Winkler, S. S. Sodium-23 magnetic resonance brain imaging. Neuroradiology 32, 416–420 (1990).

Hilal, S. K. et al. In vivo NMR imaging of sodium-23 in the human head. J. Comput. Assist. Tomogr. 9, 1–7 (1985).

Perman, W. H., Turski, P. A., Houston, L. W., Glover, G. H. & Hayes, C. E. Methodology of in vivo human sodium MR imaging at 1.5 T. Radiology 160, 811–820 (1986).

Thulborn, K. R. Quantitative sodium MR imaging: A review of its evolving role in medicine. Neuroimage 168, 250–268 (2018).

Bottomley, P. A. Sodium MRI in man technique and findings. eMagRres 1, 353–365 (2012).

Chung, C. & Wimperis, S. Optimum detection of spin-3/2 biexponential relaxation using multiple-quantum filteration techniques. J. Magn. Reson. 88, 440–447 (1990).

Navon, G. Complete elimination of the extracellular 23Na NMR signal in triple quantum filtered spectra of rat heart in the presence of shift reagents. Magn. Reson. Med. 30, 503–506 (1993).

Reddy, R., Shinnar, M., Wang, Z. & Leigh, J. S. Multiple-quantum filters of spin-3/2 with pulses of arbitrary flip angle. J. Magn. Reson. 104, 148–152 (1994).

Hancu, I., Boada, F. E. & Shen, G. X. Three-dimensional triple-quantum-filtered 23Na imaging of in vivo human brain. Magn. Reson. Med. 42, 1146–1154 (1999).

Tsang, A., Stobbe, R. W. & Beaulieu, C. Triple-quantum-filtered sodium imaging of the human brain at 4.7T. Magn. Reson. Med. 67, 1633–1643 (2012).

Stobbe, R. & Beaulieu, C. In vivo sodium magnetic resonance imaging of the human brain using soft inversion recovery fluid attenuation. Magn. Reson. Med. 54, 1305–1310 (2005).

Rong, P., Regatte, R. R. & Jerschow, A. Clean demarcation of cartilage tissue 23Na by inversion recovery. J. Magn. Reson. 193, 207–209 (2008).

Mennecke, A. B. et al. Longitudinal sodium MRI of multiple sclerosis lesions: Is there added value of sodium inversion recovery MRI. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging. 55, 140–151 (2022).

Okada, T. & Akasaka, T. Editorial for “longitudinal sodium MRI of multiple sclerosis lesions: is there added value of sodium inversion recovery MRI?”. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging. 55, 152–153 (2022).

Ra, J. B., Hilal, S. K. & Cho, Z. H. A method for in vivo MR imaging of the short T2 component of sodium-23. Magn. Reson. Med. 3, 296–302 (1986).

Ra, J. B., Hilal, S. K. & Oh, C. H. An algorithm for MR imaging of the short T2 fraction of sodium using the FID signal. J. Comput. Assist. Tomogr. 13, 302–309 (1989).

Benkhedah, N., Bachert, P. & Nagel, A. M. Two-pulse biexponential weighted 23Na imaging. J. Magn. Reson. 240, 67–76 (2014).

Qian, Y. et al. Short-T2 imaging for quantifying concentration of sodium (23Na) of bi-exponential T2 relaxation. Magn. Reson. Med. 74, 162–174 (2015).

Winter, P. M. & Bansal, N. TmDOTP5–as a 23Na shift reagent for the subcutaneously implanted 9L gliosarcoma in rats. Magn. Reson. Med. 45, 436–442 (2001).

C. L. Lawson, R. J. Hanson, Solving least-squares problems (Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, 1974), Chapter 23, p.161.

G. H. Golub, C. F. Van Loan, Matrix computations (3rd Ed) (The John Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, ed. 3, 1996).

Kirkwood, B. R. & Sterne, J. A. C. Essential medical statistics (Blackwell Science, 2003).

Qian, Y. et al. Proof of concept for the separation of mono-T2 and bi-T2 sodium in human brain through two-TE acquisitions at 3T, presented at the 25th Annual Meeting of the ISMRM. Honolulu, Hawaii, USA 22–27, 6355 (2017).

Boada, F. E., Gillen, J. S., Shen, G. X., Chang, S. Y. & Thulborn, K. R. Fast three-dimensional sodium imaging. Magn. Reson. Med. 37, 706–715 (1997).

Lakshmanan, K. et al. An eight-channel sodium/proton coil for brain MRI at 3 T. NMR Biomed. 31, e3867 (2018).

Goldstein, I. et al. Association between sodium-and potassium-activated adenosine triphosphatase α isoforms and bipolar disorders. Biol. Psychiat. 65, 985–991 (2009).

Carvalho, A. F., Firth, J. & Vieta, E. Bipolar disorder. N. Engl. J. Med. 383, 58–66 (2020).

Xie, L. et al. Sleep drives metabolite clearance from the adult brain. Science 342(6156), 373–377 (2013).

Madelin, G., Kline, R., Walvick, R. & Regatte, R. R. A method for estimating intracellular sodium concentration and extracellular volume fraction in brain in vivo using sodium magnetic resonance imaging. Sci. Rep. 4, 4763 (2014).

Blunck, Y. et al. 3D-multi-echo radial imaging of 23Na (3D-MERINA) for time-efficient multi-parameter tissue compartment mapping. Magn. Reson. Med. 79, 1950–1961 (2018).

Lommen, J. M. et al. Probing the microscopic environment of 23Na ions in brain tissue by MRI: On the accuracy of different sampling schemes for the determination of rapid, biexponential decay at low signal-to-noise ratio. Magn. Reson. Med. 80, 571–584 (2018).

Leroi, L. et al. Simultaneous multi-parametric mapping of total sodium concentration, T1, T2 and ADC at 7 T using a multi-contrast unbalanced SSFP. Magn. Reson. Med. 53, 156–163 (2018).

Alhulail, A. A. et al. Fast in vivo 23Na imaging and mapping using accelerated 2D-FID UTE magnetic resonance spectroscopic imaging at 3 T: Proof of concept and reliability study. Magn. Reson. Med. 85, 1783–1794 (2021).

Ridley, B. et al. Distribution of brain sodium long and short relaxation times and concentrations: a multi-echo ultra-high field 23Na MRI study. Sci. Rep. 8, 4357 (2018).

Kratzer, F. J. et al. 3D sodium (23Na) magnetic resonance fingerprinting for time-efficient relaxometric mapping. Magn. Reson. Med. 86, 2412–2425 (2021).

Syeda, W., Blunck, Y., Kolbe, S., Cleary, J. O. & Johnston, L. A. A continuum of components: Flexible fast fraction mapping in sodium MRI. Magn. Reson. Med. 81, 3854–3864 (2019).

Riemer, F., Solanky, B. S., Wheeler-Kingshott, C. A. & Golay, X. Bi-exponential 23Na T2* component analysis in the human brain. NMR Biomed. 31, e3899 (2018).

Qian, Y., Williams, A. A., Chu, C. R. & Boada, F. E. Multi-component T2* mapping of knee cartilage with ultrashort echo time acquisitions: Ex vivo results. Magn. Reson. Med. 64, 1427–1432 (2010).

Qian, Y. et al. Sodium imaging of human brain at 7 T with 15-channel array coil. Magn. Reson. Med. 68, 1807–1814 (2012).

Jackson, J. I., Meyer, C. H., Nishimura, D. G. & Macovski, A. Selection of a convolution function for Fourier inversion using gridding. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging. 10, 473–478 (1991).

Hoge, R. D., Kwan, K. S. & Pike, G. B. Density compensation functions for spiral MRI. Magn. Reson. Med. 38, 117–128 (1997).

Roemer, P. B., Edelstein, W. A., Hayes, C. E., Souza, S. P. & Mueller, O. M. The NMR phased array. Magn. Reson. Med. 16, 192–225 (1990).

Robinson, S. & Jovicich, J. B0 mapping with multi-channel RF coils at high field. Magn. Reson. Med. 66, 976–988 (2011).

Haacke, E. M., Brown, R. W., Thompson, M. R. & Venkatesan, R. Magnetic resonance–imaging–Physical principles and sequence design (Wiley, 1999).

Reichert, S., Schepkin, V., Kleimaier, D., Zöllner, F. G. & Schad, L. R. Sodium triple quantum MR signal extraction using a single-pulse sequence with single quantum time efficiency. Magn Reson Med. 92, 900–915 (2024).

Schepkin, V. D., Neubauer, A., Nagel, A. M. & Budinger, T. F. Comparison of potassium and sodium binding in vivo and in agarose samples using TQTPPI pulse sequence. J Magn Reson. 277, 162–168 (2017).

Qian Y, Lin YC, Chen X, Zhao T, Lakshmanan K, Ge Y, Lui YW, Boada FE. Multi-TE Single-quantum sodium (23Na) MRI: a clinically translatable technique for separation of mono- and Bi-T2 sodium signals. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2407.09868

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr. Ryan Brown and Mr. Karthik Lakshmanan for their support in the development of the 8-channel array sodium coil, Dr. Timothy Shepherd for his support in the recruitment of epilepsy patients, and Dr. Tiejun Zhao for his support and discussion in sodium MRI.

Funding

National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants RF1/R01 AG067502 (YQ, YL, XC, YG, YWL, FEB), R01 NS131458 (YQ, YWL, FEB), RF1 NS110041 (YG), R01 AG077422 (YG), R01 NS113517 (YQ, FEB), R01 NS108491 (YQ, FEB), and R01 CA111996 (YQ, FEB). Department of Radiology of the New York University Grossman School of Medicine General Research Fund (YQ, YG, YWL, FEB). Research reported in this publication was supported in part by the National Institute on Aging (NIA) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) under Award Number RF1/R01AG067502. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. This work was performed under the rubric of the Center for Advanced Imaging Innovation and Research (CAI2R), a National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering (NIBIB) Biomedical Technology Resource Center grant NIH P41 EB017183.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: YQ, FEB Methodology: YQ, YWL, FEB Investigation: YQ, YL, XC, YG, YWL, FEB Visualization: YQ, YWL, FEB Supervision: FEB Writing – original draft: YQ Writing – review & editing: YQ, YL, XC, YG, YWL, FEB.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interest

Authors YQ and FEB are inventor of a US Patent Application, No.: 18/920,506. Filed on October 18, 2024. The other authors have no competing interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Qian, Y., Lin, YC., Chen, X. et al. Single-quantum sodium MRI at 3 T for separation of mono- and bi-T2 sodium signals. Sci Rep 15, 27427 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-07800-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-07800-1