Abstract

This study introduces a novel methodology for predicting hydraulic conductivity (K) from standard penetration test (SPT) N-values, addressing the critical challenges of conventional field measurements that result in sparse K data. The research objectives were to: (1) establish empirical correlations between N and K, (2) develop a robust prediction model with quantifiable bounds, and (3) demonstrate practical applications for enhanced subsurface characterization. Analysis of 3508 boreholes across South Korea revealed a statistically significant negative correlation between N and K in sandy soils. Quantile regression enabled prediction of both point estimates and percentile ranges. Evaluation of six empirical equations for K estimation identified the Chapuis equation as optimal, which was integrated with field measurements to strengthen the regression model. For weathered rocks, a consistent K range was established. The methodology’s novelty lies in combining readily available SPT data with advanced statistical techniques to generate high-resolution 3D K domains, as demonstrated through kriging. Despite relatively low R2 values, the methodology achieves practical accuracy with most predictions falling within one order of magnitude of measured values. This approach significantly enhances spatial and depth-wise characterization of subsurface K, offering a practical solution for groundwater flow modeling and geotechnical design with improved resolution.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Hydraulic conductivity (K) is an essential soil property used to analyze groundwater flow, evaluate effective stress distributions, and predict contaminant transport behavior1,2. Despite its importance, reliable field measurement of K is significantly challenging due to the high variability inherent in natural soil deposits and methodological limitations3,4,5,6. Traditional field methods such as falling head or pumping tests are often costly, time-consuming, and typically provide limited data points without detailed vertical resolution, resulting in sparse and insufficient data for precise subsurface characterization7.

Conversely, the standard penetration test (SPT), a common site characterization tool, provides cost-effective and easily accessible data in the form of blow counts (N-values), which have established correlations with various geotechnical properties8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15. Due to its simplicity and cost-effectiveness, the SPT is routinely performed and provides continuous depth-wise profiles, enabling the potential creation of detailed 3D maps through geostatistical methods. Although a direct physical relationship between N and K is not clear, since N-values mainly reflect soil resistance influenced by effective stress, whereas K is primarily controlled by pore structure, an indirect correlation through void ratio (e) and effective stress is plausible and warrants empirical investigation16,17,18. Investigating a phenomenological correlation (i.e., statistical relationship observed consistently in data, without necessarily implying a direct theoretical mechanism) is worthwhile, because this effort enables constructing 3D-flow domains from N-values.

This study aims to establish the correlation between N and K specifically targeting sandy soils and weathered rocks. A database comprising 3,508 borehole records from various geotechnical investigations was analyzed. Empirical relationships were developed between N and measured K, supplemented by indirect estimates using established empirical equations (e.g., Chapuis equation) based on void ratio and grain size. To address data variability and uncertainty, quantile regression was employed, offering both central estimates and practical prediction intervals. In addition, the practical effectiveness of the proposed methodology was demonstrated by creating high-resolution 3D K models using ordinary kriging, enhancing subsurface characterization capabilities.

Research significance

This research contributes to geotechnical and hydrogeological practice by providing an effective methodology to predict K using widely available SPT data.

Novelty and literature gap

Previous studies have primarily focused on correlating N with mechanical properties such as modulus, relative density, or shear strength. This study addresses an important gap in literature by establishing correlations between N and K, using a comprehensive dataset from diverse geological settings.

High-resolution subsurface characterization

The methodology transforms routine SPT data into continuous vertical profiles of K, enabling high-resolution 3D characterization of subsurface hydraulic properties.

Cost-effectiveness and generalizability

By using existing SPT data, this approach eliminates the need for additional specialized hydraulic testing, making it particularly valuable for preliminary site assessments and projects with limited resources. The global standardization of SPT procedures further enhances the potential transferability of this approach to various geographical contexts.

The empirical foundation of this approach, supported by field observations, aligns with geotechnical engineering practices where correlations based on field data often prove valuable regardless of underlying theoretical relationships. This approach can significantly improve subsurface K characterization, leading to more reliable groundwater flow modeling and informed geotechnical designs.

Available data and correlation

Data acquisition and processing

Data from geotechnical investigation reports in practices across various apartment complex construction sites were used in the study. A total of 318 reports containing 3,508 boreholes were analyzed to extract the data:

-

Field-measured N-value profiles were available for all 3,508 boreholes.

-

Field-measured K values (KField-measured) from 653 cases were available with N-value profiles.

-

A pair of void ratio (e) and effective diameter (D10) calculated by index properties from 281 cases were available with N-value profiles.

-

98 sets of both KField-measured and e–D10 pairs were available with N-value profiles.

Consequently, the following datasets were prepared with a possible combination of each property: 653 N–K sets (555 N–K sets + 98 N–K–e–D10 sets) and 281 N–e–D10 sets (183 N–e–D10 sets + 98 N–K–e–D10 sets). Figure 1 shows how these datasets were categorized into three distinct types: (A) cases with only N and K measurements, (B) cases with N, e, and D10 measurements but without K values, and (C, D) cases with complete data including all measurements. The following section summarizes each testing method described in the report.

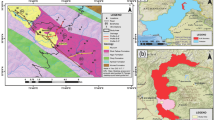

Overview of the proposed methodology: (a) Schematic representation of data organization and representative N-value (N*) determination, showing three data types based on available parameters; (b) Workflow for K prediction from N-values, illustrating the integration of direct field measurements with empirical equations to construct the regression model, followed by quantile regression analysis, order-based validation, machine learning comparison, and practical application through 3D kriging visualization.

Measuring hydraulic conductivity: field permeability test

A field permeability test (falling head test) was conducted following ASTM D6391-1119: A casing was installed up to the upper boundary of the depth range where K was to be measured. Further, water was injected from outside the casing until the water level increased to the casing top. Then, the water level dropped with time, and K was calculated. This procedure provided a single value of K to represent the depth range where the casing was installed.

Measuring N-value: borehole drilling and SPT

SPT was conducted in accordance with KS F 230720. For cases where less than 30 cm penetration even after 50 blows, the final penetration depth was recorded and the linear rescaling regarding 30 cm was applied to consistently compile data (e.g., N-value of 50 blows per 10 cm was converted to 150 blows per 30 cm). The N-values were compiled along the depth, and relevant data such as layer type, soil classification, and groundwater level (GWL) were summarized as reported in the document without any further correction. The N-values were continuously obtained at discrete intervals along the borehole, whereas KField-measured represents the overall depth range.

As shown in Fig. 1, this difference in measurement scale necessitated a methodology to determine a representative N-value (N*) for each K-measured depth range. Three different approaches to extract N* were explored:

-

Linear interpolation (N*interp): The N-value at the midpoint of the K-measured range was estimated through linear interpolation between adjacent N-values.

-

Arithmetic mean (N*mean): The average of all N-values within the K-measured range was calculated.

-

Weighted average (N*weighted): The weighted average of all N-value within the K-measured range was calculated using weight factors inversely proportional to the distance from the midpoint.

Among these approaches, the linear interpolation (N*interp) exhibited the highest correlation with K and was therefore adopted for all subsequent analyses. This can be attributed to several factors: (1) linear interpolation captures the continuous depth-dependent variation of N-values more accurately than simple averaging methods, (2) the midpoint of the K-measurement range typically represents the most characteristic hydraulic properties of that interval, and (3) arithmetic mean can be disproportionately influenced by extreme values, while weighted average introduces arbitrary assumptions about the influence of distance. The linear interpolation method provided correlations approximately 5–8% stronger than the alternative approaches, validating its selection for this study.

Estimating the void ratio and effective diameter: soil index property tests

Reports included soil index properties such as water content, specific gravity, grain size distribution (GSD) curve, and Atterberg limits, from laboratory tests21,22,23,24. For boreholes lacking KField-measured, the void ratio (e) and effective diameter (D10) that were used to estimate K in further sections were determined using \(S \cdot e = w \cdot G_{s}\) and interpolated from the GSD curve, respectively.

Overview of methodological workflow

The methodological framework adopted in this study is schematically summarized in Fig. 1b, illustrating a structured workflow from data acquisition to the practical application of the developed model. The workflow involves the following sequential steps:

Data classification and representative N-value determination: Depending on the availability of parameters, data were grouped into three types: (1) N–K sets, (2) N–e–D10 sets, and (3) N–K–e–D10 sets. For each case, representative N-values at the K measurement depth were calculated using interpolation (Fig. 1a).

Empirical correlation development: Direct correlations between N and KField-measured were analyzed (Fig. 3). In parallel, K estimations were performed (Fig. 5) using empirical equations from soil index properties (i.e., e and D10).

Quantile regression modeling: A quantile regression model was developed to capture both central trends and prediction intervals (10th–90th percentiles), reflecting the variability of field data (Fig. 7).

Model validation and comparison: The predictive model was further validated using order-based analysis (Fig. 8), and comparison with a multivariate random forest regression (Fig. 9) to assess its practical reliability.

3D hydraulic conductivity modeling: The predicted K were applied to create high-resolution 3D subsurface domains using ordinary kriging (Fig. 10), demonstrating the method’s practical utility.

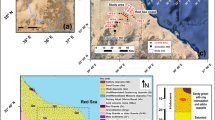

Regional distribution and characteristics of the dataset

To evaluate the representativeness and spatial diversity of the dataset, all 3508 boreholes were grouped into nine regions (A–I) based on geographic proximity and similarities in soil composition, as illustrated in Fig. 2. Each region is characterized by its number (No.) of boreholes, average (Avg.) GWL, and average sampling or testing depth (i.e., the depth from which K or soil index properties were obtained), with statistics summarized in a tabular format.

Pie charts show the proportion of each soil type based on unified soil classification system (USCS) within each region. SM (silty sand) was the dominant soil type across all regions, with some areas consisting entirely of sand. In some regions (A, B, C, D, and I), the average test depth exceeds the average GWL, indicating that samples were typically taken from fully saturated zones. However, in the other regions (E, F, G, and H), the average GWL is deeper than the test depth, suggesting that certain samples were collected above the water table. These samples were excluded from correlation analysis to ensure consistency in saturated conditions. This spatial and soil-type-based overview highlights the diversity yet consistency of the dataset.

Correlations between available data

Correlation between measured N-value and hydraulic conductivity

Figure 3 shows the correlation between the measured and representative N-values and the corresponding KField-measured for each borehole (653 N–K sets; (A, C, D) in Fig. 1). Each soil type is labelled with different symbols and colors ranging from clay to weathered rock. Clayey and silty soils, characterized by weak SPT resistance and inherently low K, are plotted in the lower-left region. Conversely, gavel, with a high K and strong SPT resistance, appears in the upper part of the plot. The weathered rock consistently exhibits N-values exceeding 50 blows/10 cm, with KField-measured ranging between 10–3 and 10–5 cm/s.

Correlation between field-measured SPT N-values and hydraulic conductivity (KField-measured) for different soil types. For sandy soils (SM), which are shown in black, a clear negative correlation between N-values and K is observed, as indicated by the regression line (Eq. 1).

On the other hand, the negative correlation between N and K is predominant for sandy soils, as regressed by a black line (Eq. 1) in Fig. 3, despite its relatively low coefficient of determination (R2) (= 0.3869) and high mean absolute percentage error (MAPE) (= 10.31%) calculated in logarithmic scale. It is noted that such scatter and relatively low R2 values are typical in geotechnical correlations involving SPT N-values, yet these correlations are widely accepted and used in practice14,25. This level of correlation can be considered acceptable particularly for K, where order of magnitude differences are required to significantly influence flow analyses.

Correlation between measured N-value and estimated void ratio

The calculated void ratio from the measured water content and specific gravity is plotted with the measured N-values (281 N–e–D10 sets; (B, C, D) in Fig. 1) in Fig. 4. Each soil type is distinguished using different symbols and colors. As highlighted in previous section, clayey soil exhibits low K and N-values and a higher void ratio than sand. However, gravel and weathered rock show notably scattered data within specific ranges. Sandy soil shows a clear negative correlation between the N-values and void ratio, with the N-values increasing with an increase in soil density. The correlation between these variables indicates that N-values can be indirectly linked to K through their effect on void ratio.

A higher N-value indicates greater resistance in sand, which is often associated with higher effective stress. While effective stress itself does not directly cause changes in the void ratio, a higher effective stress typically corresponds to a lower void ratio from a phenomenological perspective. As soils become denser under higher effective stress (reflected by higher N-values), the pore structure undergoes fundamental changes that control hydraulic behavior, not only through reduced void volume, but also through potential changes in pore connectivity and increased flow path tortuosity. These modifications in pore structure may lead to reduced permeability pathways between soil particles, providing a physical basis for the observed negative correlation between N and K. This indirect physical connection supports the empirical correlation developed in this study.

Application of the empirical equation for estimating K

Comparative analysis of empirical equations

Among 281 N–e–D10 sets (183 N–e–D10 sets + 98 N–K–e–D10 sets; ((B, C, D) in Fig. 1)), the initial focus was on estimating K for 183 N–e–D10 sets ((B) in Fig. 1) that lacked field-measured values. Here, KField-measured were not available; however, N-values, void ratio (e), and effective diameter (D10) were present and included in the analysis. The K for granular media increases with higher e and higher D1026. Various empirical equations reflecting these trend are summarized in Table 127,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35.

The data collected from boreholes with both KField-measured and the corresponding index properties (98 N–K–e–D10 sets; (C, D) in Fig. 1) were used to evaluate the applicability of each model for estimating K. The estimated hydraulic conductivity (KEstimated) by each equation in Table 1 is plotted in Fig. 5. Either the underestimation or overestimation of KEstimated originated from limited applicability as designated for each model. Among the six equations, the Chapius equation (Fig. 5f), which has a broad applicability in terms of D10, demonstrated the best performance with the lowest MAPE of 17.38%, making it particularly suitable for K estimation in sandy soils, including silty sands.

Validation of empirical equations for hydraulic conductivity estimation based on void ratio and effective diameter: Comparison between field-measured (KField-measured) and estimated (KEstimated) values using (a) Hazen, (b) Slichter, (c) Terzaghi, (d) Kozeny–Carman, (e) Navfac DM7, and (f) Chapuis equations.

Validating the estimated hydraulic conductivity using quantile regression

Quantile regression methodology

Quantile regression is an advanced statistical technique that extends the linear regression model to estimate conditional quantiles of the response variable distribution36. In this study, this is employed to address the scattered and enveloped distribution observed in the relationship between N-values and K, as indicated in Fig. 3. Although a negative correlation between N-values and K is evident, the data exhibit significant variability and spread, with no single linear trend capturing the full range of the possible K values for a given N-value. This variability highlights the inherent uncertainty in K distributions, which cannot be adequately represented by traditional linear regression methods that predict only a single central tendency.

Unlike traditional linear regression, quantile regression can model multiple conditional quantiles (e.g., 10th, 50th, and 90th percentiles). For example, the 50th quantile corresponds to the median of the distribution, whereas the 10th and 90th quantiles represent the lower and upper extremes, respectively. This allows for a more comprehensive analysis of the variability in K. This approach predicts not only a specific K value but also a range of likely values, thereby affording the potential to effectively capture the bounded distribution.

Quantile regression for measured and empirically estimated hydraulic conductivity

Among the results presented in Fig. 3, the KField-measured of sandy soils (410 sets; (A, C, D) in Fig. 1) were subjected to quantile regression, and the results were presented in Fig. 6a. The black line represents the 50th quantile (i.e., median prediction). The red-colored region represents the quantile range of 25th–75th (i.e., near the median) and includes 49.76% of data, while the blue-colored region indicates 10th–90th quantile ranges and captures 79.27% of data. Theoretically, ideal quantile ranges of 25th–75th and 10th–90th should cover 50% and 80% of the data, respectively. The selection of 10th–90th and 25th–75th percentile ranges was based on both statistical and practical considerations. The 10th–90th range captures approximately 80% of the data while excluding extreme outliers that may result from measurement errors or highly localized anomalies, making it suitable for engineering design purposes. The 25th–75th range represents the interquartile range, a robust measure of central tendency that is less sensitive to outliers than standard deviation.

Quantile regression analysis of hydraulic conductivity from SPT N-values for sandy soil: (a) Field-measured data (KField-measured) with 10th–90th (blue zone) and 25th–75th (red zone) quantile bounds. (b) Validation of empirically estimated data (KEstimated) against the established quantile ranges from field measurements, with inset quantile–quantile (Q–Q) plot demonstrating distribution alignment between theoretical and sample values.

The quantile regression results derived from KField-measured were used as a benchmark to assess the validity of KEstimated. The 183 N–e–D10 sets ((B) in Fig. 1) with available N-values, void ratio, and effective diameter and without KField-measured were used to calculate KEstimated using the Chapuis empirical equation. These KEstimated values were then plotted against their corresponding N-values in Fig. 6b. Importantly, rather than developing new quantile ranges from KEstimated, these values were overlaid on the previously established quantile ranges from KField-measured. This approach allows for an independent validation of the Chapuis equation’s performance against the empirically observed distribution patterns.

The alignment of KEstimated with the quantile ranges derived from KField-measured was evaluated using a quantile–quantile (Q–Q) plot, a graphical method for comparing two probability distributions, shown as an inset in Fig. 6b. The Q–Q plot demonstrates that the distribution of KEstimated closely aligns with the quantile distribution of KField-measured, with most points falling near the 1:1 line. This alignment was further quantified by calculating the quantile coverage: 86.07% of KEstimated fell within the 10th–90th quantile range, and 53.28% fell within the 25th–75th quantile range. These values indicate that the distribution of KEstimated satisfactorily matches the variability observed in KField-measured, demonstrating the reliability of the Chapuis equation for estimating K.

The Chapuis equation demonstrated superior performance not only in directly estimating K values but also in maintaining consistency with the N–K relationship. This dual effectiveness is further supported by the similar distribution and scattered tendency between KField-measured versus N-value (Fig. 6a) and KEstimated versus N-value (Fig. 6b). The consistency across different data sources (i.e., field measurements and empirical estimations) supports the claim that the relationship between N-values and K is not merely coincidental; rather it reflects a physical relationship. The Chapuis equation’s effectiveness in bridging N-values and K validates the physical basis of our correlation, as it explicitly incorporates void ratio, the link between penetration resistance and hydraulic conductivity. This consistency demonstrates the reliability of K prediction even in scenarios where direct field measurements of K might be limited or unavailable.

Proposed regression model for predicting hydraulic conductivity

Given the reliability of the derivation of KEstimated from the void ratio and effective diameter, the values of KEstimated were included in the final regression analysis to improve robustness. The entire dataset presented in Fig. 6a,b was combined and plotted in Fig. 7 to propose the regression model provided in Eq. (2), which is represented as a blue line.

Comprehensive K prediction model: Integration of field-measured (KField-measured) and empirically estimated (KEstimated) values showing a regression relationship for sandy soils (blue zone indicates the 10th–90th quantile range), and consistent K range for weathered rocks (red zone indicates an 80% confidence interval). Histogram (inset) demonstrates normally distributed residuals of the regression model.

Equation (1) is phenomenologically derived only from KField-measured, whereas Eq. (2) incorporates both measured data and estimated data calculated from void ratio and effective diameter (KField-measured + Estimated), integrating K data from different sources to enhance comprehensiveness. These different data sources were integrated to: (1) increase the sample size, which potentially leads to more statistically reliable results, and (2) demonstrate the ability of the model to reconcile direct measurements with theoretically derived estimates, which further validates the underlying physical relationships.

The histogram in the lower left corner in Fig. 7 presents the residuals calculated on a logarithmic scale for each data point. Its near-normal distribution suggests that the regression model captures the underlying data pattern well and that the error terms are independently distributed. Despite the scattered data distribution, the upper and lower limits can be bound by considering the 10th–90th quantile range (blue zone), as indicated in Eqs. (3) and (4). These upper and lower bounds provide practical reference limits, establishing a range within which predicted K values can be considered acceptable for engineering applications. The 10th–90th quantile range captures approximately 80% of the observed data points, offering a reliable prediction interval for practical purposes.

The quantile range gradually narrows with increasing N-values, suggesting that K becomes more predictable in denser soils where N-values are higher. This narrowing trend reflects the relationship between depth, effective stress, soil density, and void ratio. As depth increases, N-values typically increase due to higher effective stress. At shallow depths where effective stress is low, soils exhibit wide variations in their initial density states, leading to diverse void ratios and consequently diverse K values at similar N-values. Conversely, higher effective stress at greater depths induces natural densification of initially loose soils, resulting in more uniform void ratios. This convergence in void ratios explains the reduced variation in K values observed at higher N-values. The proposed regression is valid up to N-values less than 50 blows/10 cm. This upper limit corresponds to the transition from soil-like to rock-like behavior, where the relationship between density state and hydraulic conductivity fundamentally changes from matrix-controlled to fracture-dominated flow.

The correlation was not clearly pronounced for weathered rocks where N-values exceed 50 blows/10 cm (equivalent to a converted N-value of 150 blows)37,38, as indicated by the red symbols in Fig. 7. Instead, it is distributed within a relatively narrow range. Therefore, the average K of 10–4 cm/s was delineated, regardless of the N-values that depend on the degree of weathering, with an 80% confidence interval (i.e., red zone).

The consistent K observed in weathered rocks, irrespective of N-values, can be attributed to their rock-like nature, where fluid flow is mainly governed by discontinuities such as fractures and joints, and not only by the density or pore size of the structure39,40. These discontinuities, as primary flow paths for fluids, dominate K in weathered rocks, which lead to its relatively consistent behavior. While our data shows approximately one order of magnitude variation in K values for weathered rocks, this simplified characterization provides a practical approach for engineering applications, though users should be aware of potential limitations in highly fractured or heterogeneous rock masses.

Order-based validation of the proposed regression model

The practical applicability of the proposed regression model for sandy soils was further evaluated using an order of magnitude analysis (Fig. 8). KField-measured values were categorized into two different orders of magnitude, with –4 representing values between 10–4 and 10–3 cm/s (362 samples) and –3 representing values between 10–3 and 10–2 cm/s (158 samples) in horizontal axis. Very low conductivity samples (order of –5) and high conductivity samples (order of –2) were excluded from this analysis due to insufficient sample sizes (11 and 1 samples, respectively).

Order-based validation of the proposed regression model for sandy soils: Bar chart showing the percentage of KPredicted values that fall within ± 0.5, ± 1, and ± 2 orders of magnitude of KField-measured (left axis). Red squares indicate the average order difference between KPredicted and KField-measured (right axis).

For each order category, the match rate between KField-measured and K values predicted from N-values (KPredicted) was quantified at three precision levels: within ± 0.5 order, within ± 1 order, and within ± 2 orders of magnitude. The left vertical axis in Fig. 8 represents these match rates as percentages. For soils with KField-measured in 10–4 and 10–3 cm/s range, the model demonstrated excellent reliability with 88.4% of predictions falling within ± 0.5 order of magnitude and 100% within ± 1 order. Similarly, for soils with KField-measured in 10–3 and 10–2 cm/s range, 67.7% of predictions were within ± 0.5 order of magnitude and 98.7% within ± 1 order. In both cases, all predictions fell within ± 2 orders of magnitude.

The average order difference between predicted and measured values, represented by the red squares in Fig. 8 (right vertical axis), was 0.23 for the lower conductivity range (–4) and 0.41 for the higher conductivity range (–3). This pattern of increasing divergence with higher KField-measured aligns with the quantile regression results shown in Fig. 7, where the prediction bands narrow with increasing N-values (corresponding to lower K). This systematic behavior confirms that the regression model performs more consistently in denser soils with higher N-values and lower K.

Despite scattered data distribution and the prediction model’s relatively low R2 value, this order-based analysis validates the practical utility of the N-value-based prediction. A high percentage of KPredicted values fall within one order of magnitude of the measured values, which is generally acceptable for most geotechnical applications. This level of accuracy, achieved using only readily available SPT data, highlights the model’s effectiveness for practical use, particularly in groundwater flow analyses. However, the exclusion of very low and high conductivity samples (order of –5 and –2, respectively) represents a limitation of the current validation, as the model’s performance at these extreme ranges remains unverified. Future studies with larger datasets including these extreme conductivity values would be valuable for extending the model’s applicable range.

Multivariate regression analysis using machine learning

While the proposed N–K regression model provides a practical and interpretable approach for estimating K using only SPT N-values, it is important to assess whether incorporating additional soil parameters can improve predictive performance. At the same time, recent studies have demonstrated the potential of machine learning models in predicting geotechnical properties from basic soil data or N-values41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48. However, these methods often come with challenges such as increased model complexity, overfitting risk, and reduced transparency, which may limit their applicability in routine engineering practice. To evaluate both the benefit of additional input variables and the comparative performance of advanced modeling techniques, a multivariate regression analysis was performed using a random forest (RF), a widely used machine learning algorithm capable of modeling complex non-linear interactions among multiple predictors.

Using the complete N–K–e–D10 sets ((C, D) in Fig. 1), the data were randomly split into training (80%) and testing (20%). Three random forest models with progressively expanding input features were developed: RF-I (N and e), RF-II (N, e, D10, and median grain size (D50)), and RF-III (N, e, D10, D50, coefficient of uniformity (Cu), and fines content (FC)). Figure 9a–c presents the comparison between measured and predicted K values for each model, and Fig. 9d–f illustrates the relative importance of each feature in the corresponding models.

Inspection of results from Fig. 9a–c reveals that the scatter patterns of predicted versus measured K values remain notably similar across all three models despite the increasing number of input features, indicating that additional parameters beyond N-values provide minimal improvement in prediction capability. The performance metrics for each model are summarized in Table 2. The R2 improved from 0.5418 to 0.6629 as additional features were incorporated, with a corresponding decrease in MAPE from 7.8411% to 6.6513% for training data. However, when evaluating model performance on test data, mixed results were observed: while R2 slightly improved from 0.2670 to 0.2911 in RF-II, it declined to 0.2652 in RF-III, falling below even in RF-I. Test MAPE consistently increased from 7.2015 to 7.5114% as model complexity increased. This pattern of deteriorating test performance despite improvements in training metrics further confirms overfitting in more complex models. Several strategies could potentially mitigate this overfitting: (1) implementing k-fold cross-validation during model training to better assess generalization performance, (2) employing feature selection techniques to identify most informative predictors, (3) applying regularization methods by limiting the number of estimators, or (4) acquiring larger datasets to better support complex models. However, even with these mitigation strategies, the fundamental challenge remains that comprehensive datasets with all required parameters are scarce in practice. Despite the theoretical advantages of including additional soil parameters, the practical utility of the simpler N–K regression model becomes evident when considering both model performance and data availability in typical geotechnical investigations. Feature importance analysis (Fig. 9d–f) consistently identified the N-value as the most influential predictor across all models, accounting for 59.76% of predictive power in RF-I, 42.59% in RF-II, and 38.50% in RF-III. These findings confirm our central hypothesis that N-values serve as robust predictors of K in sandy soils, even when considered alongside traditional soil parameters like void ratio and GSD characteristics. The consistent identification of N-value as the dominant predictor demonstrates that while additional input features contribute to K variation, N-values effectively capture the primary factors affecting K in sandy soils.

Despite the marginal improvements in training accuracy with more complex models, the practical utility of the N-value-based approach becomes evident when considering data availability. Complete N–K–e–D10 sets required for multivariate analysis are relatively scarce (98 sets in this study), whereas N-values are abundantly available from standard site investigations (3,508 boreholes in this study). Therefore, while incorporating additional soil parameters might theoretically improve prediction accuracy, the simple N–K regression model proposed in Eq. (2) offers a more practical solution for widespread application in geotechnical practice.

Generating 3D hydraulic conductivity domains using kriging

Constructing accurate flow domains of K is essential for analyses involving groundwater flow, contaminant transport, and settlement prediction. However, generating these domains using only in-situ measured K is challenging because of the limited data availability, which typically restricts the modeling to 2D analyses. Conversely, utilizing SPT N-values enables the assignment of K at a greater number of spatial locations and across depth profiles, facilitating the construction of more detailed 3D flow domains.

Figure 10a shows a plan view of the sample study area with borehole locations, along with the digital elevation model (DEM) of the area. Black symbols indicate boreholes where both K and N-values were available (17 locations), while red symbols indicate boreholes where only N-values were available (214 additional locations). Incorporating the datasets enabled constructing a 3D flow domain over an area of 2.8 km × 2.5 km, which covered both horizontal and vertical variations of K.

Enhanced 3D hydraulic conductivity (K) domains generated using ordinary kriging with both measured (KField-measured) and N-based predicted (KPredicted) values: (a) Study area (2.8 km × 2.5 km) showing borehole locations with N-only measurements (red, n = 214) and K–N measurements (black, n = 17). (b) 3D visualization of kriged K domain with digital elevation model (DEM) as surface mesh, demonstrating enhanced spatial resolution from incorporating predicted values. (c) Horizontal cross-sections at 10, 15, and 20 m elevations showing detailed K variability captured by the integrated approach.

Ordinary kriging, which is a widely used geostatistical interpolation method for spatial data distribution, was employed to construct the flow domain49. Ordinary kriging was selected due to its well-established performance in geostatistical modeling and its ability to account for spatial autocorrelation while maintaining computational efficiency50. The kriging implementation involved a spherical variogram model (a function describing spatial correlation as a function of distance) to estimate spatial relationships, with optimized grid spacing for efficiency. Kriging was performed to generate and compare two 3D K domains: one using only KField-measured, and the other using both KField-measured and KPredicted. For sandy soils, K was predicted based on Eq. (2), while for weathered rock, a constant K value of 10–4 cm/s was applied.

Kriging with only K Field-measured

The results showed that K remains nearly constant at a given elevation and decreases with an increase in depth. The near-constant K at the same elevation is attributed to the limited number of boreholes with KField-measured and the inconsistent elevations where measurements are conducted. The decrease in K with depth aligns with the negative correlation between the N-values and K discussed in previous sections, because N-values typically increase with depth.

Kriging with both K Field-measured and K Predicted

The results of kriging with both KField-measured and KPredicted are shown in Fig. 10b,c respectively. Figure 10b presents the reconstructed 3D K distribution, where the surface mech represents the DEM. By incorporating KPredicted, the kriging results revealed detailed horizontal and vertical variations in K, which were not discernible in domains generated using only KField-measured. Figure 10c provides horizontal cross-sections of the 3D domain at elevations of 10, 15, and 20 m. These cross-sections illustrate how incorporating N-based predictions enhance the resolution of K distribution in the horizontal direction. In addition, the variation in K in the vertical direction is captured more precisely. Whereas the overall trend shows a decrease in K with depth, localized variations where K increases at certain areas were identified.

The inclusion of N-based K predictions addressed the limitations posed by sparse KField-measured. The kriging results demonstrated how this approach enables a more robust representation of subsurface conditions, capturing localized variations and providing a continuous 3D distribution of K values. The ability to resolve horizontal variations and depth-dependent trends in K has potential to improve the accuracy and utility of flow domain models for geotechnical and hydrogeological applications.

Conclusions

This study presented a comprehensive approach for predicting hydraulic conductivity (K) in sandy soils and weathered rocks using standard penetration test (SPT) N-values to overcome the challenges of hydraulic data scarcity. A robust and generalized regression model was developed by integrating field data with empirical equations, despite no direct physical relationship.

-

A negative correlation was identified between N-values and K in sandy soils. For weathered rocks, a consistent range of K values was observed; however, no direct correlation with N was found.

-

K estimated from empirical equations, particularly the Chapuis equation, were incorporated to enhance the robustness of the N-based prediction model. This integration accounted for variability in K and strengthened the robustness of the prediction model, especially in cases where field measurements were sparse or inconsistent.

-

The quantile regression provided not only point predictions but also probabilistic ranges of K. This approach acknowledges the inherent variability in soil properties and offers more comprehensive predictions, supporting better decision making in geotechnical engineering.

-

Additional validation through order-based analysis and multivariate machine learning techniques confirmed the practical utility and robustness of the N-based prediction model. Most predictions fell within one order of magnitude of measured values, while random forest analysis consistently identified N-values as the dominant predictor of K.

-

A comparison between kriging results using only measured K and those incorporating predicted values highlighted the practical advantages of N-based predictions in constructing 3D K domains. The inclusion of predicted values significantly improved spatial resolution, offering a more detailed understanding of both horizontal and vertical variations of subsurface hydraulic characteristics.

The correlation between K and N enabled a more detailed spatial modeling of K. The prediction model demonstrated practical utility despite the inherent data variability. The robustness of the proposed methodology is supported through multiple parallel validation approaches, including empirical equation consistency, quantile regression analysis, and order-based validation, collectively establishing confidence in the model’s reliability. This study contributes to the field by improving the accuracy and applicability of K predictions, particularly in data-limited environments. While this study demonstrates the practical utility of N-based K prediction for enhancing subsurface modeling, several limitations, such as relatively low R2 values and simplified approach for weathered rock characterization, should be acknowledged. Future work should focus on external validation with datasets from more diverse geological settings to further assess the model’s broader applicability.

Data availability

Data will be made available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Rangarajan, S., Rahardjo, H., Satyanaga, A. & Li, Y. Influence of 3D subsurface flow on slope stability for unsaturated soils. Eng. Geol. 339, 107665 (2024).

Goodarzi, M. R., Vazirian, M. & Niazkar, M. Hydraulic conductivity estimation: Comparison of empirical formulas based on new laboratory experiments. Water 16, 1854 (2024).

Deb, S. K. & Shukla, M. K. Variability of hydraulic conductivity due to multiple factors. Am. J. Environ. Sci. 8, 489–502 (2012).

Gofar, N. et al. Factors affecting hydraulic anisotropy of soil. Geomech. Eng. 36, 343–353 (2024).

Hu, W., Shao, M., Wang, Q. & She, D. Effects of measurement method, scale, and landscape features on variability of saturated hydraulic conductivity. J. Hydrol. Eng. 18, 378–386 (2013).

Lee, B.-J. Improvement of field falling-head test and determination of hydraulic conductivity using Darcy’s equation. Sci. Rep. 14, 17928 (2024).

Palmer, M. & El-Idrysy, H. Comparison of borehole testing techniques and their suitability in the hydrogeological investigation of mine sites. in Agreeing on Solutions for More Sustainable Mine Water Management–Proceedings of the 10th ICARD and IMWA Annual Conference, Santiago, Chile (2015).

Anbazhagan, P., Parihar, A. & Rashmi, H. N. Review of correlations between SPT N and shear modulus: A new correlation applicable to any region. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 36, 52–69 (2012).

Bol, E. A new approach to the correlation of SPT-CPT depending on the soil behavior type index. Eng. Geol. 314, 106996 (2023).

Cubrinovski, M. & Ishihara, K. Empirical correlation between SPT N-value and relative density for sandy soils. Soils Found. 39, 61–71 (1999).

Fabbrocino, S., Lanzano, G., Forte, G., Santucci de Magistris, F. & Fabbrocino, G. SPT blow count vs. shear wave velocity relationship in the structurally complex formations of the Molise Region (Italy). Eng. Geol. 187, 84–97 (2015).

Ji, P. et al. Energy measurement in standard penetration tests. Sustainability 15, 1–15 (2023).

Kang, C. et al. Examination of the correlation between SPT and undrained shear strength: Case study of clay till in Alberta, Canada. Eng. Geol. 334, 107510 (2024).

Mujtaba, H., Farooq, K., Sivakugan, N. & Das, B. M. Evaluation of relative density and friction angle based on SPT-N values. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 22, 572–581 (2018).

Panjamani, A., Manohar, D. R., Moustafa, S. S. R. & Al-Arifi, N. S. N. Selection of shear modulus correlation for SPT N values based on site response studies. J. Eng. Res. 4, 18–42 (2016).

Morin, R. H. Negative correlation between porosity and hydraulic conductivity in sand-and-gravel aquifers at Cape Cod, Massachusetts, USA. J. Hydrol. 316, 43–52 (2006).

Rosas, J. et al. Determination of hydraulic conductivity from grain-size distribution for different depositional environments. Groundwater 52, 399–413 (2014).

Sperry, J. M. & Peirce, J. J. A model for estimating the hydraulic conductivity of granular material based on grain shape, grain size, and porosity. Groundwater 33, 892–898 (1995).

ASTM-D6391-11. Standard Test Method for Field Measurement of Hydraulic Conductivity Using Borehole Infiltration. ASTM International at (2020).

KS-F-2307. Method for Standard Penetration Test. Korean Industrial Standards at (2022).

KS-F-2303. Test Method for Liquid and Plastic Limit of Soils. Korean Industrial Standards at (2022).

KS-F-2306. Standard Test Method for Water Content of Soils. Korean Industrial Standards at (2020).

KS-F-2308. Test Method for Density of Soil Particles. Korean Industrial Standards at (2022).

KS-F-2302. Test Method for Particle Size Distribution of Soils. Korean Industrial Standards at (2022).

Tsai, C. C., Kishida, T. & Kuo, C. H. Unified correlation between SPT–N and shear wave velocity for a wide range of soil types considering strain-dependent behavior. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 126, 105783 (2019).

Chapuis, R. P. Predicting the saturated hydraulic conductivity of soils: A review. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 71, 401–434 (2012).

NavfacDM7. Design Manual-Soil Mechanics, Foundations, and Earth Structures. US Gov. Print. Off. (1974).

Carman, P. C. Fluid flow through granular beds. Trans. Inst. Chem. Eng. Lond. 15, 150–156 (1937).

Kozeny, J. Ueber kapillare leitung des wassers im boden. Sitzungsberichte Akad. Wissenschaften Wien 136, 271 (1927).

Carman, P. C. Flow of Gases Through Porous Media (Butterworths, 1956).

Chapuis, R. P., Gill, D. E. & Baass, K. Laboratory permeability tests on sand: influence of the compaction method on anisotropy. Can. Geotech. J. 26, 614–622 (1989).

Hazen, A. Some physical properties of sand and gravel with special reference to their use in filtration, in 24th Ann, Rep. Mass. State Board Heal. Boston, 1983 (1983).

Chapuis, R. P. Predicting the saturated hydraulic conductivity of sand and gravel using effective diameter and void ratio. Can. Geotech. J. 41, 787–795 (2004).

Slichter, C. S. Theoretical investigation of the motion of ground waters, in 19th Ann. Rep. US Geophys Surv. 304–319 (1899).

Terzaghi, K. Principles of soil mechanics: III. Determination of permeability of clay. Eng. News Rec. 95, 832–836 (1925).

Hao, L. & Naiman, D. Q. Quantile Regression (Sage, 2007).

Seoul-Metropolitan-Government. Geotechnical Investigation Manual. 17 at (2006).

Ministry-of-Land-Infrastructure-and-Transport. Road Design Manual. 402 at (2000).

Chicco, J. M., Comina, C., Mandrone, G., Vacha, D. & Vagnon, F. Field surveys in heterogeneous rock masses aimed at hydraulic conductivity assessment. SN Appl. Sci. 5, 374 (2023).

Zoorabadi, M., Saydam, S., Timms, W. & Hebblewhite, B. Analytical methods to estimate the hydraulic conductivity of jointed rocks. Hydrogeol. J. 30, 111–119 (2022).

Olamide Taiwo, B. et al. Explosive utilization efficiency enhancement: An application of machine learning for powder factor prediction using critical rock characteristics. Heliyon 10, e33099 (2024).

Rabbani, A. et al. Optimization of an artificial neural network using four novel metaheuristic algorithms for the prediction of rock fragmentation in mine blasting. J. Inst. Eng. Ser. D https://doi.org/10.1007/s40033-024-00781-x (2024).

Rabbani, A. et al. Utilization of tree-based ensemble models for predicting the shear strength of soil. Transp. Infrastruct. Geotechnol. 11, 2382–2405 (2024).

Rabbani, A. et al. A comprehensive study on the application of soft computing methods in predicting and evaluating rock fragmentation in an opencast mining. Earth Sci. Inf. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12145-024-01488-z (2024).

Rabbani, A., Samui, P. & Kumari, S. Implementing ensemble learning models for the prediction of shear strength of soil. Asian J. Civ. Eng. 24, 2103–2119 (2023).

Rabbani, A., Samui, P. & Kumari, S. A novel hybrid model of augmented grey wolf optimizer and artificial neural network for predicting shear strength of soil. Model. Earth Syst. Environ. 9, 2327–2347 (2023).

Rabbani, A., Samui, P. & Kumari, S. Optimized ANN-based approach for estimation of shear strength of soil. Asian J. Civ. Eng. 24, 3627–3640 (2023).

Rabbani, A. et al. Optimization of an artificial neural network using three novel meta-heuristic algorithms for predicting the shear strength of soil. Transp. Infrastruct. Geotechnol. 11, 1708–1729 (2024).

Wackernagel, H. Ordinary Kriging. Multivariate Geostatistics: An Introduction with Applications (Springer, 2003). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-662-05294-5_11.

Li, Y. et al. Database of soil properties incorporating organic content from roots and soil organisms for regional slope stabilisation. Sci. Rep. 15, 1066 (2025).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (Nos. RS-2021-NR060085, RS-2023-NR076991). This work was based on data obtained from “GS Engineering and Construction”.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Wanhyuk Seo: Visualization, Methodology, Software, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing—Original Draft. Eomzi Yang: Methodology, Formal analysis, Investigation. Tae Sup Yun: Conceptualization, Supervision, Validation, Writing—Review and Editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Seo, W., Yang, E. & Yun, T.S. Enhanced characterization of hydraulic conductivity via standard penetration test for sandy soils and weathered rocks. Sci Rep 15, 23594 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-08300-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-08300-y