Abstract

In today’s digital environment, effectively detecting and censoring harmful and offensive objects such as weapons, addictive substances, and violent content on online platforms is increasingly important for user safety. This study introduces an Enhanced Object Detection (EOD) model that builds upon the YOLOv8-m architecture to improve the identification of such harmful objects in complex scenarios. Our key contributions include enhancing the cross-stage partial fusion blocks and incorporating three additional convolutional blocks into the model head, leading to better feature extraction and detection capabilities. Utilizing a public dataset covering six categories of harmful objects, our EOD model achieves superior performance with precision, recall, and mAP50 scores of 0.88, 0.89, and 0.92 on standard test data, and 0.84, 0.74, and 0.82 on challenging test cases–surpassing existing deep learning approaches. Furthermore, we employ explainable AI techniques to validate the model’s confidence and decision-making process. These advancements not only enhance detection accuracy but also set a new benchmark for harmful object detection, significantly contributing to the safety measures across various online platforms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Online platforms host an immense volume of user-generated images and videos. Ensuring safety on online platforms requires the rapid and accurate detection of harmful or prohibited visual content. This necessitates robust object detection models capable of identifying target objects (e.g. weapons or explicit imagery) in user-uploaded images in real time. Object detection is a fundamental computer vision task where algorithms must both locate and classify objects within an image1. Modern object detection has been driven by deep learning, yielding two major paradigms: two-stage detectors exemplified by Faster R-CNN2 and one-stage detectors exemplified by the YOLO series3. In two-stage frameworks like Faster R-CNN, a Region Proposal Network first hypothesizes potential object regions, which are then classified and refined in a second stage4. This approach achieves high accuracy but can be computationally heavy due to the sequential proposal and classification steps. In contrast, one-stage models such as You Only Look Once (YOLO) perform detection in a single pass: a convolutional network directly predicts object bounding-boxes and classes across the entire image1. By eliminating the proposal stage, YOLO dramatically improves the speed at some cost to absolute accuracy, making it attractive for real-time applications. A more recent paradigm is transformer-based detectors such as DEtection TRansformer (DETR)5, which redefine detection as a set prediction problem using an encoder–decoder transformer architecture. DETR eliminates the need for hand-designed anchors and post-processing (non-max suppression) by predicting a fixed set of objects with a global attention mechanism. However, the attention-based approach requires extensive computation and data, which initially limited its practicality6. Thus, despite the rise of transformers, convolutional backbones remain highly competitive, especially when data are limited or real-time performance is required.

Backbone neural networks play a critical role in these frameworks by extracting visual features for detection. Traditionally, deep convolutional neural networks (CNNs) such as ResNet7 or CSPNet8 serve as backbones, leveraging hierarchical feature extraction that has proven to be effective in vision tasks. CNN backbones are favored for their efficiency and strong inductive bias for locality, but they can struggle with modeling long-range dependencies. The advent of Vision Transformers (ViT) introduced an alternative backbone architecture, using self-attention to capture global relationships in the image. Vision Transformers have achieved remarkable results in image classification and are being explored in detection frameworks. However, ViT models often require large training datasets and careful regularization, as they can under-perform CNNs on tasks (such as remote sensing) where labeled data are sparse9. Recent research emphasizes that neither approach strictly dominates; instead, their combination or careful selection based on data availability can yield the best results. For instance, hybrid models that distill knowledge from a ViT into a CNN have shown superior accuracy with compact size10, and transformer-based detectors augmented with convolutional modules can attain real-time speeds6. These insights guide the design of next-generation object detectors that strive for both high accuracy and efficiency.

Recently, YOLOv8 has emerged as a leading one-stage detector for its balance of accuracy and real-time speed. Nevertheless, challenging cases–where objects are obscured, small, or visually ambiguous–remain a bottleneck. Such “hard-case” scenarios require more refined representation learning and robust feature extraction to ensure reliable detection. Additional complexities arise from the varying resolutions and angles under which harmful items may appear, further complicating accurate classification and localization.

Motivated by these challenges, this study proposes an enhanced YOLOv8-based model that addresses the detection of harmful or offensive objects under visually complex scenarios. Unlike methods that rely heavily on large architectural overhauls (e.g., attention-based transformers or multi-model ensembles), our aim is to retain YOLOv8’s efficiency while making targeted improvements that improve object detection reliability in real-world contexts. Our contributions can be summarized as follows:

-

We propose a structured enhancement of the YOLOv8 model architecture, incorporating modifications to the cross-stage partial fusion blocks in the backbone, model head, and adjusting depth-multiples for optimized performance and detection accuracy.

-

We conduct training and validation of our modified model variants with both normal and hard-case (e.g. small or camouflaged objects) test scenarios, followed by fine-tuning the best-performing model.

-

We evaluate our method using precision-recall analysis at different confidence levels, calculate the mean Average Precision (mAP) metric, inference speed and test on a separate dataset to ensure robust detection in novel scenarios.

-

We visually present the model’s predictions to rigorously evaluate and confirm its performance to standard YOLOv8 across challenging scenarios, without employing additional attention modules or complex knowledge-distillation pipelines.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 provides a review of related work. Section 3 outlines our methodology, including architectural modifications and experimental protocols. Experimental results and comparisons are presented in Section 4, and Section 5. Section 6 presents the final remarks for the study.

Literature review

Explicit content detection (blood & distressful content)

The detection of explicit, distressful, or harmful imagery has become a crucial aspect of online platform moderation, especially with the rise of disturbing content that can negatively impact users. This includes the identification of violent scenes, blood, and offensive materials such as weapons, drugs, or abusive gestures. One of the pioneering works in this area is the HOD: Harmful Object Detection dataset introduced by Ha et al. (2023)11, which addressed the gap in performance between normal and challenging (hard-case) scenarios. Their study revealed a marked decrease in mean average precision (mAP) when harmful objects were occluded or partially visible, demonstrating the inherent difficulty in detecting harmful content in low-quality, and cluttered environments. These findings suggest that object detection systems, such as YOLOv5, may require domain-specific modifications to effectively handle real-world data where obscured or partial objects are common.

Further extending the concept of explicit content detection, Gutfeter et al. (2024)12 tackled the issue of detecting sexually explicit content related to child sexual abuse materials, reporting an impressive accuracy exceeding 90%. Their focus on sensitive and covert content highlights the need for meticulous visual analysis when identifying harmful materials, particularly those that may be subtly embedded within larger datasets. Joshi et al. (2023)13 proposed a multi-modal approach for video content, integrating both textual and visual cues to improve the identification of short-lived, explicit events in videos. By improving the model’s ability to understand both the visual and textual contexts, they were able to capture fleeting instances of violence or explicit content that may otherwise be missed using only visual data.

Moreover, Ishikawa et al. (2019)14 explored the phenomenon of disturbing children’s animations, such as the “Elsagate” content, which incorporated violent or inappropriate imagery disguised as child-friendly media. This study underscores the potential for harmful content to appear in unconventional forms, challenging traditional detection methods. In a similar vein, Liu et al. (2022)15 adapted YOLO for adverse weather conditions like fog, illustrating the model’s flexibility to handle distorted, low-visibility environments. The same principle of domain-specific optimization can be applied to the detection of explicit content in visually impaired scenarios, such as low-quality images or partially obscured violent objects15. These collective works highlight the growing need for robust feature extraction pipelines capable of coping with clutter, low resolution, or subtle indicators of violence, all of which are essential for detecting harmful, explicit content in media.

Object detection models

Object detection is essential for identifying harmful content in images and videos, ranging from weapons to distressing images such as blood or drugs. Although classical two-stage models like Faster R-CNN have been widely used, they are often hindered by high computational overhead, making them less suitable for real-time applications. Conversely, one-stage models like YOLO have become popular due to their speed and accuracy, particularly in real-time detection tasks. A key focus of recent research is improving YOLO models to handle complex scenarios more effectively.

Wei et al. (2023)16 introduced YOLO-G, an improved YOLO variant designed for cross-domain object detection, enhancing the model’s ability to adapt to diverse and noisy environments. This domain-adaptive strategy is particularly beneficial when detecting harmful objects that may appear in varying backgrounds across platforms. Similarly, Uganya et al. (2023)17 employed Tiny YOLO for crime-scene object detection in surveillance video, specifically targeting weapons such as guns and knives. Their study emphasized the need for lightweight models that can operate on lower-end hardware, though they noted potential issues in detecting objects that are partially occluded or small. These findings suggest that real-time detection models must balance accuracy and computational efficiency, especially when dealing with hard-to-detect objects in dynamic settings.

A significant advancement in YOLO’s architecture was introduced by Liu et al. (2023)18, who proposed ADA-YOLO, a model that fuses YOLOv8 with adaptive heads to handle multi-scale and ambiguous visuals. This development is essential for enhancing detection accuracy in challenging environments, where objects may be obscured or appear in non-standard orientations. Similarly, Li et al. (2024)19 presented a “slim-neck” design using GSConv, a lightweight convolutional technique aimed at improving detection speed and efficiency, crucial for real-time applications in large-scale moderation systems. Meanwhile, Wen et al. (2024)20 introduced modifications to YOLOv8, such as EMSPConv and SPE-Head modules, to improve the detection of small, high-occlusion objects. This research demonstrates how minor architectural tweaks can significantly improve detection performance in real-world scenarios, especially when dealing with smaller objects like weapons in cluttered environments.

In addition to these enhancements, Li, Y. et al. (2023)21 modified YOLOv8 for UAV imagery recognition, demonstrating how reconfiguring detection heads can accommodate unusual viewpoints and small objects. This research is directly relevant to harmful content detection, where objects (e.g., weapons, contraband) often appear in fleeting or unusual angles that traditional models struggle to localize. Moreover, the development of QAGA-Net (Song et al., 2025) incorporates a Vision Transformer-based object detection approach that utilizes data-driven augmentation strategies to address sparse sample distributions9. This transformer-based architecture enhances multi-scale fusion and global attention, providing valuable insights for improving YOLOv8’s feature extraction and robustness, particularly in explicit or harmful content detection tasks. Additionally, Song et al. (2024)22 introduced a quantitative regularization (QR) approach to mitigate domain discrepancies in vision transformer-based object detection pipeline. Although QR is aimed at ViTs, its strategy of targeted data augmentation and variance handling can similarly inform robust detection pipelines for handling small or occluded harmful objects in data-sparse or hard-case scenarios. Likewise, HMKD-Net (Song et al., 2024) demonstrated the potential of knowledge distillation, showing that hybrid ViT-CNN models can significantly improve classification performance, which could inform future detection models focusing on fine-grained harmful content detection10.

Despite the improvements in object detection, hard-case scenarios remain a major challenge. As emphasized by Ha et al. (2023), detection performance drops significantly when objects are obscured, partially visible, or small11. While specialized techniques such as domain adaptation or partial transformation can mitigate some of these challenges, there is no single solution that fully resolves the issue. Transformer-based models like QAGA-Net may provide better global context modeling, but they often require large datasets and complex architectures to outperform CNN-based solutions in challenging scenes. Therefore, ongoing modifications to YOLOv8, such as enhancing its backbone or introducing specialized data augmentation (as seen in Ha et al.), represent viable strategies for improving detection in hard-case scenarios.

Classification Models

In object detection pipelines, classification models typically serve as the backbone for feature extraction, learning representations that inform subsequent localization tasks. Thus, classification improvements can directly translate into stronger detection performance when used as the backbone in detection models.

For example, Sattar et al. (2024)23 used a CNN+SVM pipeline to detect harmful substances in fruits, achieving 96.71% accuracy. This classification approach demonstrates the importance of domain-specific training, which is highly relevant when detecting harmful objects like weapons or drugs in complex scenes. Similarly, Pundhir et al. (2021)24 combined YOLOv3 with CNN-based classification to monitor cigarette-smoking behavior, achieving 96.74% accuracy. Their work illustrates how classification modules can complement detection systems by refining object detection results, especially for niche harmful activities like smoking.

Beyond object-level tasks, Grasso et al. (2024)25 developed KERMIT, a memory-augmented neural network designed to detect harmful memes using both textual and visual features. While KERMIT does not focus on object localization, its success in integrating multi-modal features could inform future detection pipelines, particularly in detecting symbols or violent imagery within memes or other media. Similarly, Manikandan et al. (2022)26 explored CNN-based gun classification in video frames, underscoring how classification-based architectures can assist in identifying harmful objects even in complex visual environments. Deshmukh et al. (2022)27 also proposed a CNN-based approach for identifying suspicious activities, further illustrating the broader role of classification models in analyzing risk-laden content. Lastly, Song et al. (2023)28 introduced a minimalistic single-CNN approach, achieving competitive accuracy without the complexity of multi-stage models or hybrid networks. Although aimed at remote sensing image (RSI) classification rather than detection, their findings underscore how domain-focused optimizations in a lightweight CNN can yield significant gains without large computational overhead.

While classification models are crucial for feature extraction in detection systems, it is important to note that direct comparisons between classification and detection frameworks can be misleading. Classification models do not perform localization, yet their insights into data augmentation, domain adaptation, and feature learning remain highly relevant to detection tasks. For example, YOLOv8 integrates classification networks like CSP variants of ResNet7 or MobileNet29 as part of its backbone, which emphasizes the symbiotic relationship between classification and detection models. The ongoing focus on domain-aligned modifications (e.g., enhanced feature extraction, fine-tuned training datasets) is key to achieving meaningful improvements in the detection of harmful objects, particularly in challenging environments.

In summary, the literature suggests a combination of strategies to tackle hard cases: multi-scale and context-aware feature modeling, data augmentation focusing on rare or small instances, and hybrid architectures or training to capture both local and global information. In designing the EOD-Model, we have incorporated these lessons. The enhanced backbone/neck provides strong multi-scale features; and the training data is augmented to ensure the model sees enough examples of difficult scenarios. By comparing against state-of-the-art models like QAGA-Net on their handling of challenging cases, we ensure our model’s novelty lies in how it combines these strategies within a single, efficient detector. The next section will detail our proposed methodology and illustrate how these ideas are concretely implemented in EOD-Model.

Methodology

Dataset description

The dataset used for this study is sourced from the HOD-Benchmark Dataset11, which is publicly available on GitHub. This dataset was shared for academic and research purposes only. Privacy concerns were strictly observed in alignment with the dataset’s intended research purpose.

The dataset was categorized into two groups: ’normal-case’ for images that are easily recognizable, and ’hard-case’ for images that are more difficult to identify and necessitate additional contextual information for accurate detection11. The normal case includes easily recognizable images, similar to those commonly used in current research. On the other hand, the hard-case group features images that are more challenging to identify, making this dataset a unique contribution compared to previous research. The hard-case collection consists primarily of images with dangerous objects that have obscured discriminative features or items whose colors closely match the background. This makes classification difficult and often requires additional contextual information. After dividing the dataset into normal-cases and hard-cases, each group was further split into training, validation, and test sets in a 70%-15%-15% ratio. Table 1 provides an overview of the data allocation, while Fig. 1 presents sample images from both normal-case and hard-case categories.

The instance images are chosen randomly among the datasets. The initial row displays the images in the normal scenario, while the subsequent row showcases the images in the challenging scenario. Each column represents a specific category: blood, gun, insulting gesture, knife, alcohol, and cigarette.

Proposed workflow for harmful object detection

To address the challenges of detecting harmful objects in complex scenarios, we propose a workflow that integrates the YOLOv8 model with an enhanced training, validation, and evaluation pipeline. The workflow is designed to optimize feature extraction, improve object detection accuracy, and ensure robust performance across both normal and hard-case scenarios. Figure 2 illustrates the steps involved in this process.

The workflow begins with the collection and annotation of images to establish a dataset designated for harmful object detection. During the training phase, the YOLOv8 architecture is employed, leveraging its cross-stage partial connections and advanced detection head to extract robust feature representations and predict object locations with high precision. The validation phase ensures iterative improvement of the model by evaluating performance metrics and adjusting hyperparameters as needed. Following training and validation, the final model is evaluated on the testing set to analyze its precision and recall across different confidence thresholds. Performance metrics, such as mean Average Precision (mAP), are used to assess the model’s accuracy and robustness in detecting harmful objects.

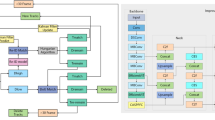

The architecture enhancements, as depicted in Fig. 3, include modifications to the detection head and additional convolutional layers to improve the classification and localization processes. The modified architecture employs extra convolution blocks in the detection head, refining the detection and classification tasks, particularly in visually complex environments. The workflow also incorporates fine-tuning and iterative evaluations, ensuring adaptability and reliability for diverse harmful object detection scenarios.

This proposed workflow aims to bridge the gap between normal and hard-case scenarios by enabling robust detection capabilities, providing a practical solution for applications such as online content moderation, surveillance, and public safety.

Proposed YOLOv8 model: setup and architectural modifications

The conv blocks activation function

In our modified YOLOv8 model, we employ the Swish activation function, also known as Sigmoid-Weighted Linear Unit (SiLU), which is defined as:

where \(\sigma (x)\) is the sigmoid function. Swish combines the properties of linear and nonlinear activation functions, enabling the network to capture complex patterns by allowing non-zero gradients for negative inputs. This characteristic is particularly beneficial for harmful object detection, where subtle features need to be identified.

We assess SiLU with often used alternatives: ReLU, Hard-Swish, and Leaky ReLU in order to better understand the behavior of various activation functions. Their mathematical formulations and explanations are given below:

-

ReLU (Rectified Linear Unit): This is one of the simplest activation functions, widely used in deep learning due to its computational efficiency.

$$\begin{aligned} \text {ReLU}(x) = \max (0, x) \end{aligned}$$(2)ReLU outputs the input \(x\) if it is positive; otherwise, it returns zero.

-

Hard-Swish: A computationally efficient approximation of Swish that replaces the sigmoid function with a piecewise linear function.

$$\begin{aligned} \text {HardSwish}(x) = {\left\{ \begin{array}{ll} 0 & \text {if } x \le -3 \\[8pt] \frac{x(x + 3)}{6} & \text {if } -3< x < 3 \\[8pt] x & \text {if } x \ge 3 \end{array}\right. } \end{aligned}$$(3)Hard-Swish approximates Swish using three linear regions:

-

For \(x \le -3\), the activation is 0.

-

For \(-3< x < 3\), the function behaves as a smooth quadratic function \(\frac{x(x + 3)}{6}\), ensuring a smooth transition.

-

For \(x \ge 3\), the activation is simply \(x\), similar to ReLU.

-

-

Leaky ReLU: This variation of ReLU allows small negative values instead of zero, preventing inactive neurons.

$$\begin{aligned} \text {LeakyReLU}(x) = {\left\{ \begin{array}{ll} x, & \text {if } x > 0 \\[8pt] \alpha x, & \text {if } x \le 0 \end{array}\right. } \end{aligned}$$(4)where \(\alpha\) is a small positive constant (typically 0.01). Unlike standard ReLU, which zeroes out negative values, Leaky ReLU assigns them a small slope \(\alpha\), reducing the dying neuron problem.

Every activating function has advantages and drawbacks. ReLU struggles with the “dying ReLU” problem even if it is computationally efficient. Applications for low power devices will find Hard-Swish helpful since it strikes a mix between efficiency and non-linearity. Leaky ReLU enables small gradients for negative inputs therefore reducing the dying ReLU problem. Effective for deep networks, our model employs SiLU to guarantee smooth gradient flow and enhances feature representation.

Adjustments to the cross-stage partial fusion (C2F) blocks

To further enhance the performance of our customized YOLOv8 model for harmful object detection, we implemented specific modifications to the Cross-Stage Partial Fusion (C2F) blocks. The primary adjustments include altering the split ratio and increasing the kernel size of the final convolutional layer within the C2F module. In the standard C2F block, the input feature map is split equally (50:50) into two branches: one passes through a series of bottleneck layers, while the other is directly concatenated with the processed features. To optimize information flow and feature diversity, we modified the split ratio to 60:40. By allocating a larger portion of the feature map to bypass the bottleneck, the model retains more raw features, which are essential for detecting subtle and varied harmful objects. This balance enhances feature extraction without overwhelming the model with redundant information. The revised split operation is defined as:

The final convolutional layer within the C2F block traditionally employs a 1x1 kernel, which primarily focuses on channel-wise feature aggregation. We increased the kernel size to 3x3 to capture larger contextual information and spatial dependencies within the feature maps, allowing the model to recognize harmful objects that may vary in size, shape, and orientation. This improvement is particularly beneficial in complex scenes where harmful objects may be partially occluded or presented in diverse contexts. However, this approach also introduces additional computational overhead. In our experiments, we observed that the increase in computation was within acceptable limits for our application. The trade-off between improved detection accuracy and computational cost was justified, as the enhanced model performance significantly contributed to more accurate harmful object detection without necessitating additional optimization techniques. This modification is formalized as:

where \(W_{\text {conv2}}^{3 \times 3}\) denotes a convolutional kernel of size 3x3, replacing the default 1x1 kernel.

Augmenting the head with additional convolutional blocks

The first detection and classification head of the YOLOv8 model employs convolutional blocks with three kernel sizes, resulting in the generation of 64 tensors and 192 channels. These are used to identify and classify the three feature maps. Afterwards, the tensor was transformed into the required channels for the purpose of identifying and classifying the output using a convolution layer. To enhance the original model, additional convolutional blocks, all with three kernel size, are added to both the detection and classification heads, increasing depth without significantly raising the parameter count. The number of additional convolutional layers can be parameterized by \(n\), which allows for flexibility in ablation experiments. Here, we consider \(n\) based on the following considerations: choosing \(n\) for our configuration to add moderate depth, increasing \(n\) slightly if it leads to a balanced improvement in performance, and limiting the maximum \(n\) to avoid the risk of overfitting and significant computational demands within the tested configurations. This structure is particularly beneficial for the model to learn specialized features by leveraging the initial layers to capture primary features and the additional layers to refine these features for more precise object detection.

QAGA-Net model overview

QAGA-Net9 is constructed upon the Faster R-CNN framework, with the Swin Transformer (Swin-T) as its foundational backbone. The Swin-T model, pre-trained on ImageNet, effectively captures both local and global visual information through its hierarchical structure of moving windows. The output from Swin-T is processed by a specialized Feature Pyramid Network (FPN) named QAGAFPN, which comprises two essential components: the Global Attention (GA) module and the Efficient Pooling (EP) module. The GA module enhances features using group convolutions and channel attention, whereas the EP module use dilated convolutions to capture objects at various scales without compromising resolution.

The Quantitative Augmentation Learning (QAL) module employs diverse probabilistic augmentations, like color jitter and Gaussian blur, throughout training to improve the model’s generalization capability. This module enhances the model’s exposure to diverse data, hence augmenting its resilience. The Region Proposal Network (RPN) of Faster R-CNN produces candidate object proposals that are then refined via Region of Interest (RoI) pooling. This procedure results in precise object detection by classification and bounding box regression.

In order to enhance efficiency, QAGA-Net implements mixed precision training with the AdamW optimizer during training. A learning rate scheduler, ReduceLROnPlateau, modifies the learning rate according to validation performance. Standard measures, including mAP, Precision, and Recall, are employed to evaluate model performance. The MeanAveragePrecision class computes these metrics, offering insight into the model’s precision in detection and localization tasks.

QAGA-Net integrates the advantages of Swin-T with specific modules such as QAL, GA, and EP to attain superior object detection efficacy.

Experimental setup

Specifications of software and hardware

We utilized the Ultralytics YOLOv8 repository as the foundation for our research code, which we updated to compare the various configuration modifications. Table 2 provides a detailed description of software and hardware specifications.

Hyperparameters of the models

Hyperparameters are crucial configurations that determine the behavior of a model during training and impact its performance. They include variables such as learning rate, batch size, and regularization strength. The predetermined hyperparameters used in the experiments are listed in Table 3. These settings were applied to all experiments.

Loss functions of YOLOv8 models

The YOLOv8 object detection model employs a combination of loss functions to optimize the training for both classification and bounding box regression. YOLOv8 utilizes three loss functions that are summed to compute the total loss, which is then used by the optimizer for backpropagation. These three loss functions are as follows:

-

1.

Varifocal Loss (VFL): The purpose of this loss function is to accurately predict the IoU Aware Classification Score (IACS) by training a dense object detector. It draws inspiration from the focal loss, which is commonly used as the classification loss (Haoyang Zhang et al.30) and is defined as:

$$\begin{aligned} \begin{aligned} \operatorname {VFL}(p, q)&= {\left\{ \begin{array}{ll} -q(q \log (p) + (1-q) \log (1-p)) & \text {if } q>0 \\ -\alpha p^\gamma \log (1-p) & \text {if } q=0 \end{array}\right. } \\ \end{aligned} \end{aligned}$$(7)Where p denotes the predicted IACS, q denotes the target score, and \(\gamma\) is the focusing parameter that adjusts the rate at which easy examples are given less importance.

-

2.

CIoU Loss: The Complete Intersection over Union (CIoU) loss improves the Intersection over Union (IoU) metric for bounding box regression by incorporating additional factors such as aspect ratio and distance, leading to more precise bounding box predictions.

$$\begin{aligned} \textrm{CIoU}=1-\textrm{IoU}+\frac{\rho ^2\left( b, b^{g t}\right) }{c^2}+\alpha v \end{aligned}$$(8)The symbol \(\rho\) denotes the Euclidean distance between the actual bounding box and the predicted bounding box centers. b and \(b^{g t}\) represent the centroids of the two bounding boxes. c is the diagonal length of the smallest enclosing box covering both bounding boxes. v measures the consistency of aspect ratios between the predicted and ground-truth boxes.

-

3.

Distribution Focal Loss (DFL): The DFL is computed by utilizing the probability distribution of bounding box coordinates, encouraging the network to learn continuous-valued localization predictions. It is formulated as:

$$\begin{aligned} \begin{aligned} \textrm{DFL} = -\Big (&\log (S_i) \times (y_{i+1}-y) + \log (S_{i+1}) \times (y-y_i)\Big ) \end{aligned} \end{aligned}$$(9)Where, \(S_i\) and \(S_{i+1}\) are the probabilities assigned to adjacent discrete locations. \(y_i\) and \(y_{i+1}\) represent the actual target locations in the distribution.

The total loss function used for training the YOLOv8 model is a weighted sum of these three components:

where hyperparameters \(\ lambda_1\), \(\ lambda_2\), and \(\ lambda_3\) regulate the relative weight of each loss function. The actual tuning of these weights is intended to achieve a balance between the efficacy of bounding box regression and the accuracy of classification. While the CIoU loss maximizes bounding box alignment and the DFL guarantees localization accuracy, the VFL component guarantees correct object categorization.

Evaluation metrics

Evaluating the effectiveness of object detection methods such as YOLO requires the evaluation of metrics. To assess the harmful object detection capabilities and performance of the proposed model, we need a collection of measures that can accurately and efficiently quantify its reliability and effectiveness. The assessment metrics employed in our experiments are as follows:

-

Precision: defined as the count of accurate positive outputs generated by the model. The computation of precision is demonstrated in equation 11.

$$\begin{aligned} \text {Precision} = \frac{TP}{TP + FP} \end{aligned}$$(11) -

Recall: measures the model’s capacity to accurately detect positive occurrences out of the total number of actual positive cases in the dataset. The recall computation is defined in equation 12.

$$\begin{aligned} \text {Recall} = \frac{TP}{TP + FN} \end{aligned}$$(12) -

IoU: the Intersection over Union (IoU) is a metric that is employed in object detection and segmentation tasks to evaluate performance. This metric measures the degree of overlap between the predicted bounding box (or segmentation mask) and the ground truth. To calculate the IoU value, we used equation 13.

$$\begin{aligned} \text {IoU} = \frac{\text {Area of Intersection}}{\text {Area of Union}} \end{aligned}$$(13) -

mAP: Mean Average Precision (mAP) is a widely used performance metric in object detection tasks. It provides a single scalar value that summarizes the precision-recall trade-off across multiple classes and different Intersection over Union (IoU) thresholds. The mAP50 metric is computed using an IoU threshold of 0.50, which primarily evaluates performance on easier detections. In contrast, the mAP50-95 metric is the mean mAP calculated over IoU thresholds ranging from 0.50 to 0.95 at 0.05 intervals, providing a more comprehensive assessment of the model’s ability to detect objects under varying degrees of difficulty. The overall mAP is computed using Equation 14, where \(AP_{k}\) represents the Average Precision (AP) for class k, and n is the total number of classes. The AP for each class is obtained using a numerical integration approach, as shown in Equation 15.

$$\begin{aligned} \text {mAP} = \frac{1}{n} \sum _{k=1}^{n} AP_{k} \end{aligned}$$(14)The Average Precision (AP) for each class is computed as the area under the Precision-Recall curve:

$$\begin{aligned} \text {AP} = \int _0^1 \text {Precision}(\text {Recall}) \, d\text {Recall} \end{aligned}$$(15)Since exact integration is impractical for discrete data points, we approximate it using the trapezoidal rule:

$$\begin{aligned} \text {AP} \approx \sum _{k=1}^{n} \frac{\text {Precision}(k) + \text {Precision}(k-1)}{2} \cdot (\text {Recall}(k) - \text {Recall}(k-1)) \end{aligned}$$(16)By combining the contributions of small trapezoidal sections, equation 16 represents the area under the Precision-Recall curve, therefore guaranteeing a more accurate representation of AP.

Explainability AI for interpretation

Building trust in neural network-based models requires providing explanations for their methods and predictions. To establish confidence in our model by providing a visual explanation, we utilized the Grad-CAM++ (Gradient-weighted Class Activation Mapping Plus Plus) (Chattopadhay et al.31), a refined iteration of Grad-CAM. Grad-CAM++ conveys visual explanations that rely on Class Activation Mapping (CAM). This methodology detects multiple instances within identical categories by localizing heatmaps to precisely identify regions associated with specific classes in an image. By employing Grad-CAM++, it is possible to display the projections of the final convolutional layers of the proposed model with high accuracy. The equation used for Grad-CAM++ can be represented as equation17.

The variable \(W_k^c\) represents the weights of a neuron. The term \(\alpha _{i, j}^{k c}\) indicates the significance of the position (i, j). The variable \(A_k\) identifies the activation map. The variable c represents the target class, and \(Y^c\) represents the score of the network’s class c.

The utilization of a pixel-wise Rectified Linear Unit (ReLU) on the ultimate activation map is essential, as it enhances the features that exert a favorable influence on the intended class.

Result and analysis

Mean Average Precision is a comprehensive indicator that combines precision and recall into a single value helpful in the evaluation of object detection methods. We therefore evaluated the baseline model as well as multiple YOLOv8 variations in search of identifying a superior harmful object detection model all based on mAP.

Comparative analysis of base models

In order to identify the most effective baseline model for our use case, we conducted an analysis of YOLOv8’s32 nano, small, and medium models. We evaluated their performance using the precision, recall, mAP50, and mAP50-90 metrics. The comparative findings are outlined in Table 4. The YOLOv8 models were pre-trained on the COCO object detection dataset, as described by Lin et al.33.

We observed that the YOLOv8m model performed well on both normal-case and hard-case test datasets compared with the YOLOv8n and YOLOv8s models. The mAP50 of YOLOv8m (0.77% and 0.69%) for the normal-case and hard-case test datasets has been achieved with the normal-case trained model, whereas the mAP50 is (0.71% and 0.55%), (0.74% and 0.65%) for the YOLOv8n and YOLOv8s models, respectively. By contrast, for the all-case dataset, the YOLOv8m model also performed better than YOLOv8n and YOLOv8s. For the all-case trained model, YOLOv8m achieved mAP50 values of (0.85% and 0.76%) in both the normal-case and hard-case test datasets, respectively. Although the parameter count of YOLOv8m is slightly higher (25.84 million) than that of YOLOv8n (3.007 million) and YOLOv8s (11.12 million), the medium model performs better overall, which will help to detect harmful objects effectively.

Comparative analysis of modified YOLOv8m

Comparison of different head configurations

The primary aim of this study is to enhance the effectiveness of YOLOv8m while minimizing the increase in parameter count. The approach used entailed enhancing the ability to detect and classify components of the YOLOv8m model using supplementary convolutional blocks. Our experiment sought to measure how enhancing the head affects the performance of YOLOv8m. Improving the performance involved implementing configurations that involved appending three, four, and five new convolution blocks. Incorporating different numbers of these blocks at the beginning of YOLOv8m yielded to various results, as shown in Table 5.

Figure 4 illustrates that more convolution blocks increase both cost and effectiveness. Based on these results, adding three more convolutional blocks boosted mAP, leading to better results compared to other models evaluated using the test dataset. However, adding five convolutional blocks showed minimal improvement, as assessed by the precision-recall metric. The main reason behind the diminished performance upon inserting more than three convolution blocks is coined as falling feature discriminability. Although initially the inclusion of more convolutional blocks enhances the model’s capability to perceive intricate features, it results in overfitting due to the inclusion of redundant attributes. Hence, the model may disproportionately prioritize the training data, which impairs its capacity to be applied to new, unfamiliar data.

Comparison of different activation functions

Further analysis was carried out on the effects of changing the default activation function, based on the optimal configuration recognized in previous experiments that revealed a marked advancement in the general performance of YOLOv8m through the incorporation of three extra convolutional blocks.YOLOv8 originally integrated SiLU, a SWISH activation function, as the default activation function across the whole network. In the upcoming experiment, we replaced SiLU with several activation functions such as Hard-Swish, ReLU, and Leaky ReLU in a systematic manner to investigate how they affect the performance of the model. The effectiveness of the SiLU can be ascribed to its distinctive attributes. SiLU provides a favorable balance between linearity and non-linearity, rendering it highly suitable for the complex tasks associated with object detection. This allows the model to accurately capture intricate patterns while addressing problems associated with the disappearance of gradients or the excessive amplification of a particular feature. Table 6 summarizes the experimental results. The SiLU was found to be the most effective activation function overall. Using the SiLU activation function, we obtained mAP50 values 90% and 70% on the normal-case and hard-case test datasets, respectively; for the normal-case train dataset only and for the all-case train dataset, we obtained mAP50 values 92% and 82% on the normal-case and hard-case test datasets, respectively.

Proposed model evaluation

The suggested model, developed through rigorous experimentation and optimization, was thoroughly examined on both normal-case and hard-case test datasets to comprehensively evaluate its effectiveness. Figure 5 shows the confusion matrices that have been normalized. Figure 6 displays the curves that represent the relationship between precision and confidence. Figure 7 displays the curves that represent the relationship between recall and confidence. Figure 8 displays the F1-confidence curves. The precision-recall curves of the suggested model on the test datasets are shown in Figure 9. Table 7 provides a summary of the efficiency of the suggested (YOLOv8m+Conv3+SiLU) model on the normal-case and hard-case test datasets, respectively, categorized by class.

Furthermore, it is crucial to build a feeling of confidence and reliability among users by providing a thorough explanation of the suggested framework. Grad-CAM++ was used to visually represent the projections made by the proposed design. The projections are derived from distinct components of the image identified within the architecture’s various Up-sample, C2F, Concat, and Conv layers. We employed the Grad-CAM++ technique to capture and analyze every image from each category in the collected data. Every image poses distinct issues, such as differences in the rotation and background. The trained model and projected label identify the created region as the main point, displaying a prominent red color to indicate its significance. Every detected flaw has a reddish spot on the heat-map. We have rendered the contours and edges precisely, demonstrating the distinct absence of overlapping issues. Figure 10 shows the input images and images generated by Grad-CAM++ for all the categories of harmful objects.

Comparison of proposed model and QAGA-Net

This section evaluates how well the Proposed model and the QAGA-Net model perform using a number of important measures, including as precision, recall, mAP50, and mAP50-90. The results of the evaluation of both models on the normal test dataset indicate there are significant differences in their performance.

Across all evaluation metrics, the Proposed model consistently outperforms the QAGA-Net model. In particular, the proposed model scored 0.89 on the precision scale, whereas QAGA-Net only scored 0.0057. This notable difference indicates the proposed model detects items in the test dataset with far greater precision. Similarly, the Proposed model demonstrated a Recall of 0.85, which was significantly higher than QAGA-Net’s Recall of 0.0522. This suggests that the Proposed model is more effective at detecting objects throughout the entire dataset.

The suggested model also performs better when looking at the mAP50 score, a crucial parameter for assessing object detection models, with a score of 0.90 as opposed to QAGA-Net’s 0.0299. This substantial difference in mAP50 highlights a clear difference in model accuracy, with the suggested model performing significantly better at precisely finding and distinguishing between objects. Furthermore, the Proposed model maintained a higher score of 0.74 in terms of mAP50-90, whereas QAGA-Net only managed a score of 0.0057. This indicates a difference in the models’ ability to maintain detection performance at different levels of Intersection over Union (IoU).

Precision, Recall, mAP50, mAP50-90, and the number of parameters for each model are all included in the comprehensive comparison of the models that can be found in Table 8.

These findings clearly show that Proposed model exceeds QAGA-Net in all evaluation criteria, implying that for object detection on the normal dataset it is a more accurate and dependable model. Although QAGA-Net’s creative design shows promise, it still lags below current models such as Proposed model. Thus, further improvements to QAGA-Net are required to close the performance gap and render it competitive with other state-of- the-art models in this field.

Comparative analysis of inference speed (FPS)

Table 9 provides a comparison of various YOLO models using their inference speed (measured in frames per second, FPS) and latency (measured in milliseconds) under two detection complexities: Normal Case and Hard Case.

With a performance of 23 FPS and 43.563 ms latency, the suggested model (YOLOv8m + Conv3 + SiLU) beats both YOLOv9m and YOLOv11m in terms of FPS while also keeping a smaller latency in the Normal Case. Though YOLOv10m and YOLOv8m have better FPS, the suggested model presents a reasonable compromise with reduced latency, which appeals to real-time users.

Once more displaying competitive performance, the suggested model in the Hard Case achieves 23.1 FPS with 43.215 ms latency. In terms of FPS, this outcome is the same as YOLOv10m and YOLOv8m except with a much reduced latency. In more complicated detecting situations, the ability of the suggested model to preserve a high FPS while lowering latency is obviously an advantage.

Therefore, for real-time detection tasks the suggested model (YOLOv8m + Conv3 + SiLU) presents a better combination of high FPS and low latency across both Normal and Hard Cases.

Discussion

This section assesses the efficacy of the proposed Enhanced Object Detection (EOD) model for detecting harmful materials by comparing its performance with those of the top approaches using the HOD benchmark dataset. Table 6 provides a comprehensive analysis of detection accuracy on the test set, the difference between training and test data, and the unique features of each method. Based on the findings, the proposed solution outperformed the existing methods in detecting the studied harmful objects. Utilizing an enhanced version of YOLOv8 for transfer learning, this has been demonstrated by achieving a 92% mAP on regular test cases and 82% mAP on difficult test cases, as shown in Fig. 4. This represents a significant step forward in the field.

The proposed EOD model has broad applications in enhancing online safety. Social media platforms can integrate this model to monitor and flag or remove harmful content, ensuring compliance with platform guidelines. Video sharing platforms can scan uploaded videos to prevent exposure to inappropriate content, especially for younger audiences. Online forums and discussion platforms can use this model to moderate large volumes of dynamic user-generated content, reviewing and eliminating inappropriate posts immediately. Additionally, companies providing online safety solutions can develop this model into an API, offering it as a service to other businesses. This broadens its application scope, making online safety accessible to smaller platforms that lack in-house resources to develop such technologies. Integrating our proposed model into these platforms will enhance their ability to detect harmful content, improve online safety, and provide a better user experience.

Conclusions

The proposed method for detecting harmful objects shows significant potential in enhancing the accuracy and reliability of computer vision analysis in real-time footage. Our enhancements to YOLOv8’s architecture aim to improve robustness and feature extraction capabilities, particularly in visually complex scenarios. By improving the YOLOv8 architecture, the proposed approach addresses the limitations of traditional methods and focuses on refining detection precision, reducing missed harmful materials, and enhancing the model’s ability to recognize inappropriate content in various settings. This sets the stage for future work to explore broader real-time applications and further advancements using advanced deep learning and segmentation techniques. Future research should consider expanding harmful object detection tasks to handle a wider range of object classes, thereby increasing the model’s versatility. Addressing the issue of false positives and negatives remains crucial, as the current method can occasionally lack confidence in identifying genuine threats or mistakenly classify harmless objects as dangerous. Additionally, efforts to improve the model’s efficiency in recognizing multiple instances within a single image using instance-segmentation techniques will be essential. While our proposed method enhances the detection capabilities of existing models, further research inspired by Ha et al. will continue to refine these techniques. This ongoing effort aims to contribute to a safer digital environment, benefiting various online services and research domains utilizing visual censoring systems.

Data availability

The original dataset was created by Ha et al.11 is publicly available and can be accessed for research purposes on the GitHub link dataset: https://github.com/poori-nuna/HOD-Benchmark-Dataset/tree/main/dataset and copyright information: https://github.com/poori-nuna/HOD-Benchmark-Dataset/tree/main

References

Yaseen, M. What is yolov8: An in-depth exploration of the internal features of the next-generation object detector (2024).

Ren, S., He, K., Girshick, R. & Sun, J. Faster r-cnn: Towards real-time object detection with region proposal networks. IEEE transactions on pattern analysis and machine intelligence 39, 1137–1149 (2016).

Redmon, J., Divvala, S., Girshick, R. & Farhadi, A. You only look once: Unified, real-time object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 779–788 (IEEE, 2016).

G., A. & S., J. Faster r-cnn explained for object detection tasks (2024).

Carion, N. et al. End-to-end object detection with transformers. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), vol. 12346 of Lecture Notes in Computer Science (LNCS), 213–229, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-58452-8_13 (Springer, 2020).

Zhao, Y. et al. Detrs beat yolos on real-time object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 16965–16974 (2024).

He, K., Zhang, X., Ren, S. & Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 770–778 (2016).

Wang, C.-Y. et al. Cspnet: A new backbone that can enhance learning capability of cnn. arXiv preprint https://doi.org/10.48550/ARXIV.1911.11929 (2019).

Song, H. et al. Qaga-net: Enhanced vision transformer-based object detection for remote sensing images. IJICC 18, 133–152 (2025).

Song, H., Yuan, Y., Ouyang, Z., Yang, Y. & Xiang, H. Efficient knowledge distillation for hybrid models. IET Cyber-Systems and Robotics (2024).

Ha, E., Kim, H., Hong, S. C. & Na, D. Hod: A benchmark dataset for harmful object detection. arXiv preprint arXiv:2310.05192 (2023).

Gutfeter, A., Gajewska, E. & Pacut, A. Detecting sexually explicit content in the context of child sexual abuse materials (2024). Preprint.

Joshi, A. & Gaggar, A. Extraction and summarization of explicit video content using multi-modal deep learning. Int. J. Comput. Sci. Trends (2023).

Ishikawa, A. Combating the elsagate phenomenon: Deep learning architectures for disturbing cartoons. In Proceedings of Secure & Trustworthy AI Conference, 124–135 (2019).

Liu, W. et al. Image-adaptive yolo for object detection in adverse weather conditions. In Proceedings of the AAAI conference on artificial intelligence 36, 1792–1800 (2022).

Uganya, G. et al. Crime scene object detection from surveillance video by using tiny yolo algorithm. In 2023 3rd International Conference on Pervasive Computing and Social Networking (ICPCSN), 654–659 (IEEE, 2023).

Wei, J., Wang, Q. & Zhao, Z. Yolo-g: Improved yolo for cross-domain object detection. Plos one 18, e0291241 (2023).

Liu, S., Zhang, J., Song, R. & Teoh, T. T. Ada-yolo: Dynamic fusion of yolov8 and adaptive heads for precise image detection and diagnosis. arXiv preprint arXiv:2312.10099 (2023).

Li, H. et al. Slim-neck by gsconv: a lightweight-design for real-time detector architectures. Journal of Real-Time Image Processing 21, 62 (2024).

Wen, G., Li, M., Luo, Y., Shi, C. & Tan, Y. The improved yolov8 algorithm based on emspconv and spe-head modules. Multimedia Tools and Applications 1–17 (2024).

Li, Y., Fan, Q., Huang, H., Han, Z. & Gu, Q. A modified yolov8 detection network for uav aerial image recognition. Drones 7, 304 (2023).

Song, H., Yuan, Y., Ouyang, Z., Yang, Y. & Xiang, H. Quantitative regularization in robust vision transformer for remote sensing image classification. The Photogrammetric Record 39, 340–372 (2024).

Sattar, A., Ridoy, M. A. M., Saha, A. K., Babu, H. M. H. & Huda, M. N. Computer vision based deep learning approach for toxic and harmful substances detection in fruits. Heliyon 10, (2024).

Pundhir, A., Verma, D., Kumar, P. & Raman, B. Region extraction based approach for cigarette usage classification using deep learning. In International Conference on Computer Vision and Image Processing, 378–390 (Springer, 2021).

Grasso, B., La Gatta, V., Moscato, V. & Sperlì, G. Kermit: Knowledge-empowered model in harmful meme detection. Information Fusion 106, 102269 (2024).

Manikandan, V. & Rahamathunnisa, U. A neural network aided attuned scheme for gun detection in video surveillance images. Image and Vision Computing 120, 104406 (2022).

Deshmukh, S., Fernandes, F., Ahire, M., Borse, D. & Chavan, A. Suspicious and anomaly detection (2022). arXiv:2209.03576.

Huaxiang Song, Y. Z. Simple is best: A single-cnn method for classifying remote sensing images. Networks and Heterogeneous Media (NHM) 18, 1600–1629 (2023).

Howard, A. et al. Mobilenets: Efficient convolutional neural networks for mobile vision applications. arXiv preprint 1704, 04861 (2017).

Zhang, H., Wang, Y., Dayoub, F. & Sunderhauf, N. Varifocalnet: An iou-aware dense object detector. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 8514–8523 (2021).

Chattopadhay, A., Sarkar, A., Howlader, P. & Balasubramanian, V. N. Grad-cam++: Generalized gradient-based visual explanations for deep convolutional networks. In 2018 IEEE winter conference on applications of computer vision (WACV), 839–847 (IEEE, 2018).

Ultralytics. Github - ultralytics/ultralytics: New - yolov8 in pytorch> onnx> openvino> coreml> tflite. https://github.com/ultralytics/ultralytics. Accessed: 2024-05-04.

Lin, T.-Y. et al. Microsoft coco: Common objects in context. In Computer Vision–ECCV 2014: 13th European Conference, Zurich, Switzerland, September 6-12, 2014, Proceedings, Part V 13, 740–755 (Springer, 2014).

Acknowledgements

The authors extend their appreciation to the Research Chair of Online Dialogue and Cultural Communication, King Saud University, Saudi Arabia for funding this research.

Funding

This work was supported by the Research Chair of Online Dialogue and Cultural Communication, King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Methodology, F.I.B., A.A.; Software, A.A.; Validation, F.I.B, M.K.J., A.A.; Formal analysis, F.I.B., A.A.; Investigation, M.K.J., A.A.; Resources, M.K.J., F.I.B, A.A.; Writing - original draft, A.A., M.K.J; Writing - review & editing, M.K.J., A.A., F.I.B., M.F.M. and S.A.; Visualization, A.A., F.I.B.; Supervision, M.F.M. and D.C.; Project administration, M.S. and S.A.; Funding acquisition, M.S. and S.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jahan, M.K., Bhuiyan, F.I., Amin, A. et al. Enhancing the YOLOv8 model for realtime object detection to ensure online platform safety. Sci Rep 15, 21167 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-08413-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-08413-4