Abstract

Resveratrol is widely used in the fields of medicine and health supplements; however, its poor stability and low relative bioavailability limit its applications. This study aimed to compare the plasma drug concentrations and key pharmacokinetic parameters of two resveratrol solid formulations, T1 and T2. A single-center, randomized, open-label, two-formulation, single-dose, two-period, crossover trial was conducted involving 12 healthy subjects. Blood samples were collected after a single dose for pharmacokinetic (PK) analysis, including Cmax, AUC0 − t, AUC0−∞, Tmax, and T1/2. The concentrations of resveratrol and its metabolites in human plasma were determined using HPLC-MS/MS. The results showed for total resveratrol, the Cmax of T1 was 4.8 times higher than that of T2, while the AUC0 − t of T1 was 1.7 times that of T2. The Tmax of T1 was also markedly shorter, whereas the t1/2 of T2 was slightly longer than that of T1. This suggests that T1 demonstrated superior absorption extent and rate, with overall pharmacokinetic performance surpassing that of T2. In addition, all drugs were well tolerated, no severe adverse reactions occurred. In conclusion, following single-dose oral administration of the two resveratrol formulations, T1 and T2, both formulations were demonstrating good safety profiles. Compared to T2, the modified formulation of T1 significantly enhanced the absorption rate, extent, and relative bioavailability of resveratrol. The test formulation T1 was overall superior to the test formulation T2.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Resveratrol (C14H12O3) was first isolated from the roots of Polygonum cuspidatum in 1940, thus being named resveratrol. Also known as 3,4’,5-trihydroxystilbene, it is a natural polyphenolic compound that is beneficial to health, predominantly found in plants such as grapes, Japanese knotweed, and mulberries1,2. Resveratrol is a colorless needle-like crystal with low solubility in water but is easily soluble in ethanol, acetone, dimethyl sulfoxide, and benzene3.

Resveratrol acts as a plant toxin and exhibits various biological activities and pharmacological effects, making it highly applicable in the food industry. It has strong antioxidant activity, capable of scavenging free radicals and inhibiting cellular oxidative damage4,5. Additionally, resveratrol has diverse bioactive properties, including anti-cancer, anti-inflammatory, anti-aging, hypoglycemic, hypolipidemic, and detoxifying effects. As a result, it is widely used in pharmaceuticals and health products6. Moreover, resveratrol can inhibit the growth of bacteria and viruses, positioning it as a potential natural antimicrobial and antiviral agent. Therefore, the application prospects of resveratrol are vast7.

Resveratrol exists in two isomeric forms: cis and trans. In nature, the trans form predominates, and under ultraviolet light, trans-resveratrol undergoes isomerization to form cis-resveratrol8. The isomerization phenomenon, coupled with its poor water solubility and stability, results in low relative bioavailability, limiting its development and utilization in food products9. Currently, extensive research is being conducted in the fields of food and pharmaceuticals to encapsulate resveratrol in delivery systems such as nanoparticles, emulsions (nanoemulsions, multiple emulsions, pickering emulsions), liposomes, hydrogels, and cyclodextrin (CD) complexes10. These delivery systems can improve the solubility, stability, and relative bioavailability of resveratrol. However, its limited relative bioavailability and poor stability remain a challenge, constraining its broader application11.

This study primarily utilized two resveratrol solid beverages developed by Qingdao Chenlan Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. as the test formulations T1 and T2. The pharmacokinetic profile, including blood drug concentrations and key pharmacokinetic parameters, of T1 and T2 was evaluated in healthy Chinese subjects following oral administration in a fasting state. The study aimed to compare the differences in the absorption rate and extent of the two formulations in the body of healthy subjects.

Subjects and methods

Study design

The study was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki and ICH-GCP guidelines. The study protocol and informed consent forms were reviewed and approved by the Independent Ethics Committee of Wuhan Zijing Hospital. All subjects provided written informed consents before any related procedure was conducted.

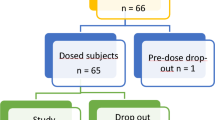

In accordance with the guidelines outlined in the National Medical Products Administration (NMPA) “Technical Guideline for Bioequivalence Studies of Generic Chemical Drugs with Pharmacokinetic Parameters as the Endpoints,” and considering the characteristics of the drug used in this study, the overall design was a single-center, open-label, randomized, two-formulation, two-period, two-way crossover, fasting pharmacokinetic study. The pharmacokinetics of the resveratrol solid beverages (dosage: 406 mg) of test formulations T1 and T2 were evaluated following a single dose of fasting oral administration in 12 healthy subjects. The randomization schedule was generated by the statistical analysis unit using SAS (version 9.4 or above), employing a block randomization method to assign each subject to either the T1-T2 or T2-T1 group. A detailed schematic of the study design is shown in Fig. 1.

Method of preparation

T1: Resveratrol and hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin (HP-β-CD)were weighed at a ratio of 1:9.5 (w/w) (1:1.57 (mol/mol)), this ratio slightly exceeds the commonly used 1:1 molar ratio reported in the literature12, aiming to further enhance inclusion efficiency and solubility. Resveratrol was dissolved in 95% ethanol and mixed with an aqueous solution of HP-β-CD. The mixture was subjected to colloid milling for over 2 h to ensure complete inclusion complex formation. After concentration, the mixture was dried under reduced pressure at 50 °C. The dried product was collected, pulverized, passed through an 80-mesh sieve, and packaged at 4.06 g per sachet.

T2: Resveratrol and starch were weighed at a ratio of 1:9.5 (w/w). Same as above.

The specific materials used in the preparation process are listed in Table 1.

Dose selection

The selected dose of resveratrol (406 mg) was determined based on a combination of safety, efficacy, and market relevance. Clinical studies have shown that doses up to 1 g/day are generally well tolerated, with only mild adverse events reported at this level13. Additionally, a 150 mg/day dose has demonstrated metabolic benefits in humans, supporting its potential for chronic disease prevention14. Furthermore, a review of commercial supplements revealed that 400 mg is the maximum single dose commonly available, making 406 mg a reasonable and practical choice for our study.

Subjects

The inclusion criteria for this study were as follows: participants aged 18 to 40 years (inclusive of both 18 and 40 years), with an appropriate gender distribution. Male subjects were required to weigh ≥ 50.0 kg, and female subjects ≥ 45.0 kg, with a body mass index (BMI) ranging from 19.0 to 26.0 kg/m². Eligible participants should be capable of effective communication with the investigator, adhere to the study requirements, and sign a written informed consent form. subjects meeting any of the following criteria were excluded: (1) Participants who have participated in other drug/device clinical trials and used investigational drugs/devices within the past 3 months; (2) Subjects with clinical conditions that require exclusion; (3) Subjects with a history of vomiting or diarrhea, or any physiological condition within 7 days prior to the trial that could interfere with the results; (4) Subjects with a history of specific allergies (e.g., asthma, urticaria, eczema), or allergies to any drug, food, or pollen, or known allergies to resveratrol; (5) Subjects who have donated blood or lost more than 400 mL of blood within the past 3 months, or who plan to donate blood during the study period; (6) Subjects deemed by the investigator to have poor compliance or any other factors that would make them unsuitable for participation in the study.

Drug administration and blood sampling

The investigational drugs were provided by Qingdao Chenlan Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. The test formulation T1 (specification: 406 mg per sachet, based on resveratrol) batch number: ResUP-20,240,802, and the test formulation T2 (specification: 406 mg per sachet, based on resveratrol) batch number: Res-20,240,802. Prior to each dosing period, subjects were required to fast for at least 10 h, with the exception of water. Subjects received either test formulation T1 or T2 (406 mg per person) in a fasting state, administered with 240 mL of warm water. No drinking was allowed from 1 h before until 1 h after dosing (except for the 240 mL of warm water used for administration). A standard lunch was provided at least 4 h after dosing.

Blood samples were collected at the following time points in each cycle: 24 h, 12 h, and 0 h before dosing, and 5 min, 10 min, 15 min, 20 min, 30 min, 45 min, 1 h, 1.25 h, 1.5 h, 1.75 h, 2 h, 2.5 h, 3 h, 3.5 h, 4 h, 5 h, 6 h, 8 h, 12 h, and 24 h after dosing, totaling 23 collection points. Blood samples of approximately 4 mL were collected under white light conditions at room temperature into EDTA-K2 anticoagulant vacuum tubes. The samples were gently inverted 6 times to mix with the anticoagulant. After collection, the samples were kept under white light at room temperature and then centrifuged (centrifugation conditions: temperature set to 4 °C, centrifugal force at 1700 g for 10 min). After centrifugation, the plasma was separated and aliquoted into two cryovials. One cryovial was used for analysis (approximately 0.8 mL), and the remaining portion was stored in a backup cryovial (approximately 0.8 mL; if less than 0.8 mL, the actual volume was recorded). The volume of plasma in each cryovial did not exceed 80% of the maximum capacity to prevent overflow during freezing.

The time from sample collection to plasma separation was controlled to within 100 min (no more than 120 min), and the samples were immediately stored at − 80 °C in a freezer. For long-term storage, the samples were kept at − 80 °C.

Assay of Resveratrol

The experiment utilized a validated LC-MS/MS assay to quantify resveratrol (BLLC), resveratrol-3-O-β-D-glucuronide (R3G), resveratrol-4-O-β-D-glucuronide (R4G), and resveratrol-3-O-D-sulfate (R3S) in plasma samples. Where total resveratrol is the sum of BLLC, R3G, R4G and R3S. A Shimadzu liquid chromatography system (Japan) was employed, consisting of a high-pressure pump (LC-30AD), online degasser (DGU-20A5R), autosampler (SIL-30AC), and column oven (CTO-30 A), all controlled by a system controller (CBM-20 A). Mass spectrometric analysis was performed using a QTRAP 5000 triple quadrupole mass spectrometer equipped with an electrospray ionization (ESI) source (Applied Biosystems, USA). Data acquisition and processing were carried out using Analyst software version 1.6.3 (Applied Biosystems, USA) and Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corp., USA). Resveratrol acid-d4, resveratrol-3-O-β-D-glucuronide-¹³C₆, and resveratrol-d4-4-O-β-D-glucuronide (TLC PHARMACEUTICAL STANDARDS) were used as internal standards. The chromatographic conditions were as follows: YMC-C18 column of 3*100 mm, 8 μm (YMC, Japan) was used; the mobile phase was (A): 5 mM ammonium bicarbonate in water and (B): 5 mM ammonium bicarbonate in methanol. The flow rate was 0.80 mL/min; autosampler temperature was set at 4 °C; column temperature was 40 °C; injection volume was 6µL. Pre-treatment of the blood sample: internal standards were added after the samples were naturally melted, and then the samples were processed by protein precipitation. In an ice water bath, 30µL of blood sample was placed in a 96 deep-well plate, 100 µL of ultrapure water was added, 500 µL of precipitant (methanol) was added, the plate was sealed, vortexed and shaken for 10 min, and centrifuged (4000 rpm) for 15 min. A 100 µL aliquot of the supernatant was transferred to a 96-deep-well plate preloaded with 300 µL of ultrapure water. The plate was sealed, vortexed for 5 min, and centrifuged at 4000 rpm for 3 min. An aliquot of 6 µL was injected for LC-MS/MS analysis. Quality control (QC) samples for resveratrol were prepared at the following concentrations: LLOQ QC (2.000 ng/mL), LQC (6.000 ng/mL), MQC2 (60.0 ng/mL), MQC1 (800 ng/mL), HQC (1600 ng/mL), and DQC (6000 ng/mL). For R3G, R4G, and R3S, QC samples were prepared at: LLOQ QC (20.00 ng/mL), LQC (60.00 ng/mL), MQC2 (600.0 ng/mL), MQC1 (8000 ng/mL), HQC (16000 ng/mL), and DQC (60000 ng/mL). For each analytical batch, the mean accuracy of LLOQ QC samples was within ± 20% of the nominal concentration, and the mean accuracy of QC samples at other concentrations was within ± 15% of the nominal values, both for intra- and inter-batch assessments. (The essential method validation parameters data are shown in Supplementary material 1, and the MS parameters are shown in Supplementary material 2).

After completion of the primary analysis, a total of 72 samples were selected for reanalysis, focusing on the Cmax vicinity and elimination phases in periods P1 and P2 for each subject. The recalculated concentrations, accuracy, and parameters of standard curves for each analytical batch, along with the recalculated concentrations and accuracy of quality control (QC) samples. Based on the accuracy data for the standard curves and QC samples from the analytical batches, the analytical data were accepted (The ISR data are shown in Supplementary material 3).

The pharmacokinetic (PK) data of free resveratrol, resveratrol glucuronide conjugates, and resveratrol sulfate conjugates were processed using Phoenix WinNonlin software (version 7.0). The primary pharmacokinetic parameters included AUC0 − t, AUC0−∞, Cmax, Tmax, t1/2, λz, AUC_%Extrap. Plasma concentration data were analyzed using a non-compartmental model. Cmax and Tmax were reported as observed values. AUC0 − t was calculated using the trapezoidal rule, AUC0−∞ = AUC0 − t + Ctn/λz. The half-life (t₁/₂) was calculated as t1/2 = 0.693/λz. The percentage of extrapolated area under the curve (AUC_%Extrap) was calculated as AUC_%Extrap = [(AUC0−∞ − AUC0 − t) / AUC0−∞] × 100%. The relative bioavailability (F value) of the test formulations was calculated using the following formula: F = AUCT1 / AUCT2 × 100%.

AUCT1: represents the area under the concentration-time curve for test drug T1, AUCT2: represents that for test drug T2 (Table 2).

Safety

All adverse events (AEs) and serious adverse events (SAEs) occurring during the clinical study were monitored for all participants. The primary safety evaluation parameters included the incidence of AEs/SAEs, clinical symptoms, vital signs, physical examination findings, laboratory test results, and 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) assessments.

Statistical methods

Analyses were performed using Student’s t test to compare, using SPSS version 25.0 (IBM, Chicago, IL, USA). P < 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

Results

Subjects

A total of 26 subjects were screened, and 12 subjects (9 males and 3 females) were ultimately enrolled. The clinical characteristics and biochemical results were showed as Table 3.

Pharmacokinetic parameters

After a single fasting oral administration of T1 or T2 preparation in 12 healthy subjects, the concentration of free (unconjugated) resveratrol, R3G, R4G, R3S and total resveratrol were measured. The pharmacokinetic parameters and concentration-time profiles of drug are listed below (Fig. 2; Table 4). Take free (unconjugated) resveratrol, for example, the calculated Cmax of T1 and T2 were 1271.79 ± 496.4 ng mL− 1 and 44.14 ± 19.05 ng mL− 1, AUC0 − t were 706.77 ± 311.24 ng h mL− 1 and 109.7 ± 45.43 ng h mL− 1, AUC0−∞ were 777.29 ± 275.48 ng h mL− 1 and 149.85 ± 51.3 ng h mL− 1. The Tmax were 0.5 h and 1.75 h and the t1/2 were 4.56 ± 5.9 h and 5.65 ± 5.36 h, respectively. The results showed significant difference between T1 and T2 administration. (The individual subject data are shown in Supplementary Material 4).

Bioavailability

As summarized in Fig. 3, compared with T2, the relative bioavailability in plasma of free (unconjugated) resveratrol in plasma was 673.95%. The R3G was 364.04%, while that of R4G was 223.97%. The relative bioavailability of R3S was 170.95%, and the total resveratrol was 212.13%.

Safety and tolerability

The safety evaluation was conducted using data from the safety analysis set, comprising 12 subjects. Among these, 10 subjects experienced a total of 17 adverse events (AEs), all of which were classified as Grade 1 in severity. The overall incidence of adverse events was 83.3% (10/12). Five subjects reported five AEs that were assessed as possibly related to the investigational drug, resulting in an adverse reaction incidence rate of 41.7% (5/12). These included one case of chest tightness and four cases of nausea. During the study, two subjects exhibited clinically significant post-dosing laboratory abnormalities as positive urine protein results, which were determined to be likely unrelated to the investigational drug. Except for two subjects with positive urine protein who reported no discomfort and refused to come to the hospital for review, the other adverse events had improved or disappeared/relapsed after follow-up. All of those AEs are summarized in Table 5.

Discussion

Recent studies on resveratrol have significantly expanded our understanding of its biological activities and potential health applications15. Resveratrol has shown promise in multiple domains, including cardiovascular health, cancer prevention, anti-aging, and metabolic regulation16. Despite these promising findings, the clinical application of resveratrol is hindered by its low relative bioavailability. After oral administration, resveratrol is rapidly metabolized in the liver and intestines through glucuronidation and sulfation, resulting in the formation of inactive metabolites and minimal systemic circulation of the parent compound17. This rapid metabolism, combined with poor water solubility and limited absorption in the gastrointestinal tract, leads to insufficient plasma concentrations to exert significant pharmacological effects18,19. Current research is focusing on optimizing formulations and delivery methods, including the use of metabolites and synthetic analogs, to enhance its efficacy in humans.

Resveratrol undergoes rapid and extensive metabolism following oral administration. Its primary metabolic pathways include glucuronidation and sulfation, resulting in metabolites such as glucuronide and sulfate conjugates20. In this study, we assessed the pharmacokinetic parameters of free (unconjugated) resveratrol, R3G, R4G and R3S. The pharmacokinetic parameters calculated for the two resveratrol formulations (T1 and T2) following oral administration in healthy Chinese subjects under fasting conditions reveal significant differences. For unbound resveratrol, the Cmax of T1 was 28.8 times higher than that of T2, the AUC0 − t of T1 was 6.4 times higher, and the AUC0−∞of T1 was 5.18 times higher. Moreover, the Tmax of T1 was considerably shorter, and its t1/2 was reduced compared to T2. These results indicate that T1 exhibited a higher absorption extent and faster absorption rate compared to T2. For total resveratrol, the Cmax of T1 was 4.8 times higher than that of T2, while the AUC0 − t of T1 was 1.7 times that of T2. The Tmax of T1 was also markedly shorter, whereas the t1/2 of T2 was slightly longer than that of T1. This suggests that T1 demonstrated superior absorption extent and rate, with overall pharmacokinetic performance surpassing that of T2. Meanwhile, the modified formulation process of T1 significantly enhanced the relative bioavailability of resveratrol in humans compared to T2.

The oral relative bioavailability of native resveratrol is remarkably low, often reported at less than 1%. This is attributed to its rapid metabolism and excretion, as free resveratrol is minimally detectable in plasma, even at high doses21. We performed a processing of T1, resveratrol and HP-β-CD were subjected to inclusion complexation, dried, pulverized and sieved. So this is the reason of the pharmacokinetic parameters for the two resveratrol formulations (T1 and T2) reveal significant differences. The inclusion complex of resveratrol (RES) with HP-β-CD has been extensively studied to overcome the poor solubility, stability, and relative bioavailability of resveratrol22. Studies using methods like molecular docking, Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR), X-ray Diffraction (XRD), and Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) confirmed that resveratrol molecules fit into the cavity of HP-β-CD, these interactions significantly improved the solubility and thermal stability of resveratrol23. Encapsulation with HP-β-CD not only stabilizes resveratrol but also retains or even enhances its antioxidant activity. For example, inclusion complexes demonstrated similar or better free radical scavenging performance compared to free resveratrol24. In our study, the resveratrol inclusion complex demonstrated significantly faster absorption rates, higher absorption efficiency, and superior relative bioavailability following oral administration in humans. These advances highlight the utility of HP-β-CD in addressing the delivery challenges of resveratrol, making it a promising carrier for pharmaceutical and nutraceutical applications.

The pharmacokinetics of resveratrol are influenced by a variety of factors that collectively determine its absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion. Apart from formulation techniques, the composition of gut microbiota affects the metabolism of resveratrol. Certain microbial species can convert resveratrol into metabolites such as dihydroresveratrol, which may contribute to its pharmacological effects25. Variability in microbiota composition among individuals can thus lead to differences in relative bioavailability and efficacy. The co-administration of fats or bio-enhancers like piperine has been reported to increase resveratrol absorption by altering intestinal permeability or inhibiting metabolic enzymes. Additionally, factors like age, gender, and health status may influence its pharmacokinetics26.

Various strategies have been explored to enhance resveratrol’s relative bioavailability and pharmacokinetic profile. These strategies aim to improve its solubility, stability, absorption, and systemic retention. Improving the solubility of resveratrol is a fundamental approach to increasing its absorption in the gastrointestinal tract27. Nanocarriers protect resveratrol from metabolic degradation and facilitate controlled release28. Chemical modification of resveratrol to form prodrugs or derivatives can enhance its metabolic stability and membrane permeability29. Besides, bypassing first-pass metabolism through non-oral routes—such as transdermal, sublingual, intranasal, or injectable formulations—can significantly improve systemic availability30. These insights underline the complexity of optimizing resveratrol’s pharmacokinetics. In our study, the improved relative bioavailability observed with the test formulation suggests the success of advanced delivery techniques in addressing these challenges. Further research should explore personalized approaches considering gut microbiota composition and physiological factors, as well as combining resveratrol with bio-enhancers or co-encapsulated compounds. Such strategies could pave the way for more consistent and effective therapeutic applications of resveratrol.

As for the mechanism by which β-CD enhances the pharmacokinetics of resveratrol, firstly, upon complexation with β-CD, the hydrophobic resveratrol molecule is encapsulated within the hydrophobic cavity of β-CD, while the hydrophilic exterior remains exposed to the aqueous environment. This significantly improves the apparent solubility and dissolution rate of resveratrol, facilitating its absorption through the intestinal mucosa31. Secondly, β-CD enhanced its chemical and metabolic stability32. Thirdly, β-CD improved permeability and absorption, which may further assist the transport of resveratrol across biological barriers33. Finally, by protecting resveratrol from rapid metabolism (particularly glucuronidation and sulfation), the complex reduces the rate of hepatic clearance and prolongs systemic circulation time. This contributes to higher and more sustained plasma concentrations34.

There are some limitations in this study. First, only healthy volunteers were enrolled in the present study, the concentration-time profile of which may differ from the different patients. Secondly, in this study, relatively high coefficients of variation (CV%) were observed for key pharmacokinetic parameters. This degree of variability has implications for both the interpretation of pharmacokinetic data and the assessment of bioequivalence. Factors such as genetic polymorphisms in UGT and SULT enzymes, variability in gut microbiota, hepatic and intestinal enzyme activity, and transporter expression all contribute to inconsistent metabolic profiles35. Notably, the coefficient of variation (CV%) for free (unconjugated) resveratrol was particularly high in this study. Free resveratrol undergoes rapid and extensive phase II metabolism—primarily glucuronidation and sulfation—shortly after absorption. As a result, the systemic exposure to the unconjugated form is typically low and highly sensitive to individual differences in metabolic enzyme activity (e.g., UGTs and SULTs), leading to marked inter-individual variability. High CV% can reduce the statistical power to detect significant differences or to demonstrate equivalence, particularly when sample sizes are modest. Although our study was designed in accordance with regulatory guidelines, we acknowledge that the observed variability may have limited the precision of our estimates. Future studies may benefit from a larger sample size to better account for inter-subject variability and to enhance the robustness and generalizability of the conclusions.

Conclusion

In summary, following single-dose oral administration of the two resveratrol formulations, T1 and T2, in healthy Chinese subjects under fasting conditions, both formulations were well-tolerated with minimal adverse reactions, demonstrating good safety profiles. Compared to T2, the modified formulation of T1 significantly enhanced the absorption rate, extent, and relative bioavailability of resveratrol. Clinical applications of resveratrol should consider personalized approaches that account for individual physiological factors. Additionally, the use of bio-enhancers or co-encapsulation with synergistic compounds may further optimize its pharmacokinetic and therapeutic outcomes.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request. Please contact Weiyong Li for data availability.

Change history

13 October 2025

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23692-7

References

Qu, J., Zhang, Y., Song, C. & Wang, Y. Effects of resveratrol-loaded dendrimer nanomedicine on hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Front. Immunol. 14 (15), 1500998. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2024.1500998 (2024).

Guo, Y., Wang, A., Liu, X. & Li, E. Effects of Resveratrol on reducing spermatogenic dysfunction caused by high-intensity exercise. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 17, 42. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12958-019-0486-7 (2019).

Yang, C. et al. Tanshinone IIA: a Chinese herbal ingredient for the treatment of atherosclerosis. Front. Pharmacol. 14, 1321880. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2023.1321880 (2023).

Gnocchi, D., Sabbà, C., Massimi, M. & Mazzocca, A. Metabolism as a new avenue for hepatocellular carcinoma therapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24 (4), 3710. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24043710 (2023).

Chen, L. et al. Intervention mechanism of marine-based chito-oligosaccharide on acute liver injury induced by AFB1 in rats. Bioresour Bioprocess. 11 (1), 13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40643-023-00708-6 (2024).

Wang, Y. et al. An umbrella insight into the phytochemistry features and biological activities of corn silk: a narrative review. Molecules 29 (4), 891. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules29040891 (2024).

Angane, M., Swift, S., Huang, K., Butts, C. A. & Quek, S. Y. Essential oils and their major components: an updated review on antimicrobial activities, mechanism of action and their potential application in the food industry. Foods 11 (3), 464. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods11030464 (2022).

Xu, X. L., Deng, S. L., Lian, Z. X. & Yu, K. Resveratrol targets a variety of oncogenic and oncosuppressive signaling for ovarian cancer prevention and treatment. Antioxid. (Basel). 10 (11), 1718. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox10111718 (2021).

Napiórkowska, A. et al. Microencapsulation of Juniper and black pepper essential oil using the coacervation method and its properties after freeze-drying. Foods 12 (23), 4345. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods12234345 (2023).

Sun, X. et al. Maillard-type protein–polysaccharide conjugates and electrostatic protein–polysaccharide complexes as delivery vehicles for food bioactive ingredients: formation, types, and applications. Gels 8 (2), 135. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels8020135 (2022).

Qin, P., Li, Q., Zu, Q., Dong, R. & Qi, Y. Natural products targeting autophagy and apoptosis in NSCLC: a novel therapeutic strategy. Front. Oncol. 14, 1379698. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2024.1379698 (2024).

Loftsson, T. & Duchêne, D. Cyclodextrins and their pharmaceutical applications. Int. J. Pharm. 329 (1–2), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpharm.2006.10.044 (2007).

Boocock, D. J. et al. Phase I dose escalation Pharmacokinetic study in healthy volunteers of resveratrol, a potential cancer chemopreventive agent. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 16 (6), 1246–1252. https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-0028 (2007).

Timmers, S. et al. Calorie restriction-like effects of 30 days of Resveratrol supplementation on energy metabolism and metabolic profile in obese humans. Cell. Metab. 14 (5), 612–622. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2011.10.002 (2011).

Kluska, M., Jabłońska, J. & Prukała, W. Analytics, properties and applications of biologically active Stilbene derivatives. Molecules 28 (11), 4482. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules28114482 (2023).

Li, N. et al. Comparison of different drying technologies for green tea: changes in color, non-volatile and volatile compounds. Food Chem. X. 24, 101935. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fochx.2024.101935 (2024).

Jiang, T. et al. Review of the potential therapeutic effects and molecular mechanisms of Resveratrol on endometriosis. Int. J. Womens Health. 15, 741–763. https://doi.org/10.2147/IJWH.S404660 (2023).

Wang, Y. et al. Resveratrol in intestinal health and disease: focusing on intestinal barrier. Front. Nutr. 9, 848400. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2022.848400 (2022).

Rege, S. D. et al. Neuroprotective effects of Resveratrol in alzheimer disease pathology. Front. Aging Neurosci. 6, 218. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnagi.2014.00218 (2014).

Xu, Y. et al. Contributions of common foods to Resveratrol intake in the Chinese diet. Foods 13 (8), 1267. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods13081267 (2024).

Ciccone, L. et al. Resveratrol-like compounds as SIRT1 activators. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23 (23), 15105. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms232315105 (2022).

Wangsawangrung, N. et al. Quercetin/hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin inclusion complex-loaded hydrogels for accelerated wound healing. Gels 8 (9), 573. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels8090573 (2022).

Teodorescu, G. M. et al. Morphological, thermal, and mechanical properties of nanocomposites based on bio-polyamide and feather keratin–halloysite nanohybrid. Polym. (Basel). 16 (14), 2003. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym16142003 (2024).

De Gaetano, F. et al. Chitosan/Cyclodextrin nanospheres for potential nose-to-brain targeting of idebenone. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 15 (10), 1206. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph15101206 (2022).

Bahramzadeh, A., Bolandnazar, K. & Meshkani, R. Resveratrol as a potential protective compound against skeletal muscle insulin resistance. Heliyon 9 (11), e21305. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e21305 (2023).

Choi, M-K. et al. Pharmacokinetics of Jaspine B and enhancement of intestinal absorption of Jaspine B in the presence of bile acid in rats. Mar. Drugs. 15 (9), 279. https://doi.org/10.3390/md15090279 (2017).

Moura, F. A. et al. Antioxidant therapy for treatment of inflammatory bowel disease: does it work? Redox Biol. 6, 617–639. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.redox.2015.10.006 (2015).

Soltani, M. et al. Efficacy of graphene quantum dot-hyaluronic acid nanocomposites containing Quinoline for target therapy against cancer cells. Sci. Rep. 15 (1), 8494. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-81604-7 (2025).

Abo-Kadoum, M. A. et al. Resveratrol biosynthesis, optimization, induction, bio-transformation and bio-degradation in mycoendophytes. Front. Microbiol. 13, 1010332. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2022.1010332 (2022).

Yau, G. T. Y. et al. Cannabidiol for the treatment of brain disorders: therapeutic potential and routes of administration. Pharm. Res. 40 (5), 1087–1114. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11095-023-03469-1 (2023).

Almawash, S. et al. Injectable hydrogels based on cyclodextrin/cholesterol inclusion complexation and loaded with 5-fluorouracil/methotrexate for breast cancer treatment. Gels 9 (4), 326. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels9040326 (2023).

Hu, B., Zheng, X. & Zhang, W. Resveratrol-βcd inhibited premature ovarian insufficiency progression by regulating granulosa cell autophagy. J. Ovarian Res. 17 (1), 18. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13048-024-01344-0 (2024).

Huang, X. et al. Preparation and embedding characterization of hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin/menthyl acetate microcapsules with enhanced stability. Pharmaceutics 15 (7), 1979. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics15071979 (2023).

Elizabeth Millichap, L. et al. Targetable pathways for alleviating mitochondrial dysfunction in neurodegeneration of metabolic and non-metabolic diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22 (21), 11444. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms222111444 (2021).

Kerimi, A. et al. The gut Microbiome drives inter- and intra-individual differences in metabolism of bioactive small molecules. Sci. Rep. 10, 19590. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-76558-5 (2020).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 82173903).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Tingting Liu and Weiyong Li contributed to the conception of the study, and Jing Wang, Peiru Chen, Dongli Yin, Haijun Zhang, Xiang Qiu and Shengcan Zou experimented. Jing Wang performed the data analyses and wrote the manuscript; Weiyong Li funded the successful completion of this experiment.All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This research was conducted under the guidance of the Declaration of Helsinki, Good Clinical Practice (GCP) guidelines of the China Food and Drug Administration (CFDA) and authorized by the Independent Ethics Committee of Wuhan Zijing Hospital. Clinical trial registration numbers: ChiCTR2500095657. The date of registration is 10/01/2025.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original online version of this Article was revised: The original version of the Article contained an error in the Author Contributions section. It now reads: “Tingting Liu and Weiyong Li contributed to the conception of the study, and Jing Wang, Peiru Chen, Dongli Yin, Haijun Zhang, Xiang Qiu and Shengcan Zou experimented. Jing Wang performed the data analyses and wrote the manuscript; Weiyong Li funded the successful completion of this experiment.All authors reviewed the manuscript.”

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, J., Liu, T., Chen, P. et al. Pharmacokinetic evaluation of two oral Resveratrol formulations in a randomized, open-label, crossover study in healthy fasting subjects. Sci Rep 15, 24515 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-08665-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-08665-0