Abstract

The widespread adoption of Electric Vehicles (EVs) presents new challenges for efficient and timely access to Charging Stations (CSs), particularly under constraints of limited availability and variable demand. The current investigation addresses the EV charging station allocation problem, aiming to guide EVs to optimal CSs based on real-time and forecasted system dynamics. An integrated framework that combines load profile forecasting, optimal path planning, and drone-assisted edge computing is proposed to support decision-making. Specifically, a Nonlinear Auto-Regressive with Exogenous inputs (NARX) model is used to predict future load profiles at CSs, enabling proactive management of charging demand. To determine the most accessible stations, Dijkstra’s algorithm for shortest-path computation based on the EV’s current location and the locations of the CSs around is applied. Furthermore, drones with lightweight edge computing algorithms enabled real-time data exchange between CSs and EVs, providing up-to-date information on slot availability and local crowd conditions. For the forecasting component, the NARX model has provided a correlation coefficient of 90% for the CS real data collection. Dijkstra’s algorithm was employed to effectively optimize the routing of EVs to their nearest charging stations by determining optimal shortest paths. The simulation results demonstrate that the proposed approach significantly enhances EV allocation efficiency while reducing both waiting times and travel distances. Further research is needed to address regulatory and logistical challenges associated with drone deployment in real-time applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Study background

Electric vehicles (EVs) have emerged as a transformative solution in the global shift toward sustainable and environmentally friendly transportation. Unlike conventional internal combustion engine vehicles, EVs rely on electric power stored in batteries, resulting in significantly lower greenhouse gas emissions, reduced dependence on fossil fuels, and quieter operation1. In addition, EVs are known for their reduced maintenance requirements. In this perspective, EVs can significantly mitigate climate change impacts, especially if powered by renewable energy sources such as solar panels. This advantage, combined with technological advancements, supportive government policies, and increased environmental awareness, has driven widespread EV adoption. However, the global transition to EVs faces challenges, particularly in developing charging infrastructure and managing charging operations.

Charging infrastructure challenges

The rapid development and the growing adoption of EVs have posed new concerns for the almost stakeholders including the EVs’ owners, the charging infrastructure managers, the aggregators, the electric grid operators, and the relevant decision-makers2. As EVs become increasingly favorite car user option, their success depends not only on manufacturing technology but also on the effectiveness and accessibility to their supporting logistical infrastructure, including charging stations (CSs). EVs charging infrastructure plays a critical role in enabling widespread use, yet it faces several pressing challenges. Firstly, the spatial distribution of CSs is often uneven, with urban areas better served than rural or suburban regions. Secondly, the current infrastructure struggles to keep pace with the rapidly growing EV fleet, leading to congestion and long waiting times at CSs. Additionally, many CSs lack efficient energy management systems, resulting in inefficient utilization and potential overloading of local power grids. Technical issues such as varying charging standards, insufficient real-time information on CSs availability, and the absence of predictive analytics for demand forecasting further complicate the user experience. These limitations underscore the need for intelligent, scalable, and future-proof solutions to ensure that EV charging infrastructure can support the next phase of sustainable mobility.

The problem of EVs allocation to charging stations (CSs) is inherently multi-dimensional, involving temporal, spatial, and computational complexities. Indeed, EVs must be routed to suitable CSs based on geographical proximity, the dynamic availability of charging slots and the forecasting of energy demand at each station. A simplistic shortest-path strategy may lead to congestion or excessive wait times if the nearest station is already overloaded. Key challenges include: (1) Real-time availability uncertainty since charging station occupancy can change rapidly, requiring real-time information sharing; (2) Forecasting energy load. Indeed, accurate load forecasting is crucial, as unplanned EV arrivals during peak demand periods can result in significant charging delays; (3) Path optimization under uncertainty for which deciding on a charging station based purely on distance ignores critical factors like expected waiting time or crowd density; and (4) Scalability of data processing: centralized systems face significant performance limitations when processing large-scale data in real time. To address these challenges, the present framework integrates load profile forecasting using NARX models, optimal path planning with Dijkstra’s algorithm, and drone-based edge computing for real-time, decentralized decision support. This holistic approach aims to provide EVs with actionable information to make informed charging decisions in dynamic environments with space–time dependencies.

While the proposed framework incorporates drone-based edge computing for real-time EV-CS communication, this component remains theoretical and was not fully implemented in the current evaluation. Key barriers to full implementation include regulatory and logistical challenges, specifically airspace authorization requirements, public safety policies, and operational constraints associated with UAV deployment in urban environments. This study’s scope emphasizes solutions compatible with current infrastructure limitations.

Motivation

As EV adoption rises, new challenges emerge, particularly around establishing efficient, feasible/optimal, and intelligent allocation of EVs to CSs. Therefore, EVs’ owners should efficiently participate in any effort aiming to improve the charging ecosystem and contribute to the optimal scheduling3. Optimal allocation of CSs to moving EVs has become a cornerstone of EV infrastructure planning and management. This ensures users’ needs are met while maximizing network efficiency and reliability. For instance, a recent survey paper4 investigated the problems related to control and forecasting aiming to improve the charging operations based on emerging technologies such as data-driven approaches and machine learning (ML). In the context of a deregulated energy market, the price of electricity is also important and impactful5. To reduce the cost, save time, and increase the life-time of the EV battery, efficiently forecasting the price of charging is also critical for all EVs charging ecosystem components6. To meet the rising charging needs, effective EV to CS allocation requires a multifaceted approach involving load profile forecasting at the CS level, optimal path planning for EVs in low State of Charge (SoC), and real-time computational support at the various devices/equipment and enablers level. Traditional approaches for station allocation have primarily relied on static parameters, such as population density, proximity to main highways, and estimates of average daily usage. However, the rapid evolution of data analytics, machine learning, and the Internet of Things (IoT) has created opportunities to enhance these methods by using predictive models, real-time data analysis, and path optimization. In fact, as opposed to the classical charging problem where vehicles are to be charged during their parking time (usually during night hours), dynamic EV charging is requested in real-time when EVs are on the road while facing a shortage of charge. Under such circumstances, EVs may need assistance from other parties playing the role of enablers. The EV drivers should therefore be alerted about their vehicle battery SoCs in real-time. Once the SoC reaches a minimum threshold, an optimal (not necessarily the nearest) CS as well as the optimal path he should follow to reach the allocated CS7 should be assigned. By leveraging data on electricity demand at the CSs level, road patterns, and vehicle energy consumption, advanced forecasting models and path planning algorithms can assist in determining future demand and establish optimal station allocation that aligns with both current EV SoC and its short-term need for charging. Additionally, EVs’ relatively short driving range and dependence on accessible CSs necessitate an approach that accounts for route planning and energy consumption patterns. This may enable drivers to access charging facilities with minimal deviation from their planned paths8. To ensure efficient charging operations, several attributes related to load and energy storage should be considered carefully. The EV charging behavior and load have randomness and uncertainty, making them affected by many factors. Road network structure (rectilinear and curvilinear paths), traffic congestion, CSs distribution, driving path, travel destination, initial SoC and even the driver(s) psychology and level of anxiety are the most relevant attributes9.

In the current landscape, integrating emerging technologies such as drones10,11, Internet-of-Things (IoT)12, servers and Mobile Edge Computing (MEC) technologies are important to process and analyse data related to EVs charging locally and globally13. Meanwhile, urban and high-traffic areas exhibit data latency that could be detrimental for the efficient operation. Therefore, integrating those contributors may help in improving the EVs ecosystem. Via Edge computing devices, computational power is brought closer to EVs and CSs, providing real-time processing capabilities that reduce the need for centralized data centres and minimize data transfer delays14. Drone-enabled edge computing can support a wide range of functionalities in EV charging infrastructure, from monitoring CSs availability and energy demand to providing real-time updates on route crowds by accurately surveying the urban area traffic around the CSs15. By deploying a fleet of drones, it becomes possible to dynamically manage charging station resources and optimize power distribution based on real-time data. Additionally, using drones with high-resolution cameras and lightweight computer vision algorithms may assist the CS allocation by efficiently surveying traffic congestion, mainly around CSs16. To contribute to the effort of improving the EVs’ charging operations, the current paper introduces a comprehensive framework to efficiently assign any EV needing charge to the “best” charging station by involving new technologies and algorithms. The proposed solution integrates path planning optimization at the vehicle level with energy management strategies at the CS level.

Research gap and study contributions

The primary goal of this study is to present a comprehensive approach integrating a fleet of drones, load profile forecasting at the CSs and an optimal path planning algorithm to support informed decision-making for optimally allocating EVs to CSs in a dynamic real-time context. The main aim of this study is to develop the overall architecture and contribute to provide insightful solutions for alleviating the assignment problem already complex even in a static context, as it involves many constraints. Therefore, the main contributions of this study can be summarized as follows:

-

This study introduces a holistic and intelligent framework that addresses the complex and dynamic problem of assigning EVs to CSs in real-time. Unlike static or offline methods, this framework integrates multiple cutting-edge technologies to enable smart, context-aware decision-making. The system combines forecasting models, path planning algorithms, and mobile edge computing, facilitated through drones, to dynamically evaluate and respond to rapidly changing conditions such as station availability, traffic patterns, and load demands. This comprehensive and modular architecture allows for adaptive behavior in real-world urban environments, significantly enhancing the responsiveness, efficiency, and scalability of EV charging logistics.

-

A major contribution of this study is the implementation of a load forecasting mechanism using the Nonlinear Auto-Regressive with Exogenous inputs (NARX) model. This predictive tool enables the system to anticipate future charging loads at individual CSs by accounting for historical usage patterns, time-of-day effects, and other external inputs. Accurate ahead-of-time load forecasting allows the system to proactively steer EVs away from stations that are predicted to be overloaded or congested, thereby reducing queue times and mitigating the risk of charging delays. This forecasting approach empowers infrastructure operators and EV users alike to optimize resource allocation and improve overall system reliability.

-

To further support the decision-making process of EV drivers, the study incorporates a path optimization component based on Dijkstra’s algorithm. This robust shortest-path algorithm is adapted here to calculate the most efficient route to candidate CSs while considering geographic proximity. By integrating this path planning capability with real-time station data, the system helps drivers avoid unnecessary detours and ensures a balance between minimizing travel distance and maximizing the likelihood of successful, timely charging. This component plays a crucial role in enhancing user convenience and reducing both travel time and energy waste.

-

The framework also pioneers the use of drone-assisted edge computing as a novel solution for real-time data collection and dissemination. Drones equipped with lightweight processing capabilities act as mobile edge nodes that continuously gather, process, and relay information about CS availability, crowd levels, and local traffic. This decentralized approach ensures low-latency communication between infrastructure components and the EVs. The use of drones not only expands the spatial coverage of information networks but also allows for quick adaptation to dynamic environmental conditions, such as unexpected outages or surges in demand. This innovation enhances system agility and supports more informed, balanced decisions by the EVs’ drivers.

In the present study, the focus will be on the two first components, namely, the load profile forecasting and the path planning. The fleet of drones as part of the proposed comprehensive approach will not be considered for technical challenges related to regulations on using drones and logistical reasons.

Paper organization

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. “Material and methods” section presents the literature review, discussing existing works on EV charging infrastructure, load forecasting, demand side management (SDM) and path planning with focus on key research gaps. “Data records” section describes the materials and methods used in the proposed framework, including the NARX model for load forecasting and Dijkstra’s algorithm for optimal route planning. “Results and discussion” section outlines the datasets utilized for conducting the forecasting part. “Conclusions and future directions” section presents the experimental results and analysis, evaluating the framework’s performance through multiple metrics including forecasting accuracy, travel efficiency, and decision responsiveness. The proposed approach is benchmarked against baseline methods. Section 6 provides final conclusions from the investigation summarizing the main findings and proposing future research directions, such as enhancing scalability, developing more advanced prediction models, and integrating with smart grid technologies.

Literature review

The following section presents a critical review of literature addressing load profile forecasting at charging stations, demand-side management, and path planning optimization.

Load profile forecasting

Focusing on the short-term load forecasting of EV-CSs using machine/deep learning techniques2,3, the following recent articles are reviewed, while highlighting various aspects, when available, such as: the statistical, machine learning, deep learning, or hybrid method being used, the case study being investigated, inputs/features being selected while developing the forecasting model, prediction horizon, performance metrics to evaluate the goodness of the built-forecasting models, and main findings obtained.

For instance, one of the objectives of17 was to, indirectly, estimate solar PV power generation and, directly, estimate the corresponding EV charging demand by utilizing three deep learning techniques, namely Recurrent Neural Network (RNN), Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) (alongside its variants, including vanilla, stacked, and bidirectional), and Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU). Once the forecasts were obtained, the second objective was to exploit them in identifying the optimal capacity of battery storage needed to support the EV charging infrastructure. Hourly solar PV power generation data (15 kWp capacity for one operational year) and 15-min EV charging-demand data at university facilities were used to conduct the forecasting tasks. The latter comprises of various parameters, such as timestamp, EV ID, CS, power required, etc. were used to develop the forecasting models. Standard performance metrics, including the Mean Square Error (MSE), Root MSE (RMSE), and Mean Absolute Error (MAE) were used to evaluate the effectiveness of the investigated forecasting models. Results showed that a simple RNN and bidirectional LSTM were superior to other techniques investigated for forecasting the solar PV power generation and EV charging demand, respectively.

The authors in18 examined three time series models to directly predict electricity demand of EV CSs, namely Auto Regressive Moving Average (ARMA), Auto Regressive Integrated Moving Average (ARIMA), and Seasonal Auto Regressive Integrated Moving Average (SARIMA). Dataset of EV charging activities from two sources were used to develop the forecasting models: public data on EV charging events in Colorado, USA for four operational years and EV charging data from ChargeMOD terminals in Kerala, India for several operational months of various configurations and targets (for technical and economical perspectives). Both sources comprise various parameters used while developing the forecasting models, such as start and end timestamp of charging events, total duration of charging events, and energy consumption in kWh. Standard performance metrics, including the RMSE, MAE, and Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE) were used to evaluate the effectiveness of the investigated forecasting models. Results indicated that SARIMA was superior to other techniques in terms of forecasting accuracy.

The authors in9 studied the challenges of predicting the short-term EV stations’ charging power caused by the randomness and uncertainty of user behavior. Specifically, the authors proposed a fusion prediction model integrating time-series and nonlinear attributes using Partial Least Squares Regression (PLSR) and Light Gradient Boosting Machine (Light-GBM), whose hyper-parameters were optimized using Bayesian methods for enhanced performance. The RMSE, MAE, and MAPE were used to assess the prediction accuracy of the proposed approach. Experimental investigation using historical real EV charging load data19 showed the superiority of the fusion prediction approach compared to each individual model and other benchmarks (i.e., Backpropagation Neural Network (BPNN), Convolutional Neural Network (CNN), and LSTM) in accurately predicting the EV charging power, thereby ensuring an optimal scheduling of EV/CSs as well as a safe operation of the power grid.

In20, a multi-feature data fusion-based load forecasting approach for EV CSs using an LSTM forecasting model was proposed. The proposed model incorporated historical weather conditions, such as wind speed, ambient temperature, and relative humidity, as crucial inputs with different lags to enhance the predictability of the LSTM model. The results demonstrated the effectiveness of the data fusion strategy, with the MAE used as the performance metric.

The authors in21 examined the effectiveness of various data-driven forecasting techniques, ranging from simple methods (e.g., linear regression) to more advanced machine learning models (e.g., neural network, ensemble methods such as Bagging, Gradient Boosting, Ada Boosting, and RF) and deep learning models (e.g., CNN, LSTM) models. All models were evaluated against a naïve model, and a traditional baseline forecasting approach. Based on data from Charge pilot system, a charging and energy management system, was used to evaluate the models’ performance, comprising over 350,000 charging sessions from more than 500 sites. Multiple features and performance metrics were used to develop the forecasting models, RMSE, normalized RMSE (nRMSE), MAE, which mean fundamental scaled error, coefficient of determination (R2), as well as pinball and interval scores for the probabilistic forecasting evaluation. Among the models investigated, Ada Boosting and RF demonstrated the most robust forecasting results.

The study conducted in22 proposed a novel intelligent grid EV charging scheduling and energy management approach by integrating a Genetic Algorithm (GA), i.e., to optimize EV charging demands while minimizing peak grid loads, GRU, i.e., to accurately predict EV charging demands and grid load conditions, paving the way towards effective optimization of EV charging schedules, and Reinforcement Learning (RL) algorithm, i.e., to minimize grid energy costs while meeting EV charging demands, thereby ensuring effective an overall energy management. Four datasets were used to evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed approach (GA-GRU-RL): Pecan Street, NREL, ChargePoint, and UCI. Various performance metrics from the literature, such as accuracy, recall, F1 score, and AUC, were used to assess its effectiveness. Results demonstrated the superiority of the proposed approach, though certain limitations were noted.

In23, a comparison between various deep learning techniques for the EV charging load forecasting problem up to 72 h ahead was conducted. Specifically, LSTM, GRU, hybrid CNN and LSTM, hybrid CNN and GRU, multivariate LSTM, and multivariate GRU models were investigated and effectively compared, with K-Nearest Neighbor (KNN), Decision Tree (DT), Random Forest (RF), and Support Vector Machines (SVMs) used as benchmarks. The study utilized a publicly available dataset comprising data from over 30,000 EV charging sessions collected from various charging sites in California, USA24. The dataset included various features for developing forecasting models, such as timestamps and energy delivered in kWh. The RMSE and MAE were used to assess the models’ effectiveness. Results showed that the multivariate LSTM and GRU models were superior in terms of prediction accuracy. Similarly,25 developed a forecasting model for EV charging requirements across different forecasting horizons, including 1-h ahead, day-ahead, and week-ahead predictions, using ANN and LSTM models. The study utilized a real dataset extracted from the Adaptive Charging Network at the California Institute of Technology, USA. Results demonstrated that the LSTM model outperformed the ANN model in terms of RMSE across the various forecasting horizons investigated.

Researchers in26 adopted the deep learning LSTM model to forecast the charging demand/task of EV CSs and proposed a comprehensive optimization model addressing charging costs, battery degradation, and user dissatisfaction. The model, formulated as a Mixed-Integer Non-Linear Programming (MINLP) problem, integrates traffic uncertainty, facility limitations, and time-of-use electricity prices. The proposed model showed superior performance and effectiveness in simulations compared to existing methods.

On the other hand, there are other indirectly related research works where the contribution of forecasting-based machine/deep learning is shown effective in optimizing the scheduling of EV CSs. For instance,27 adopted an ANN-based forecasting model, developed using the Levenberg–Marquardt training/learning algorithm, for short-term forecasting of solar PV power generation and the state of charge of the storage battery in a solar PV-powered EV charging station for decision-making perspectives. Similarly,28 implemented an ANN-based forecasting model equipped with the Levenberg–Marquardt algorithm to effectively estimate energy production from a 65-kW solar PV system integrated with a charging station featuring charging points of varying power levels. Specifically, the ANN was used to estimate the weather data, from which the associated energy generation was subsequently computed. The authors in29 developed a novel design approach that encompassed evaluating and analysing various solar irradiance prediction models, forecasting day-ahead solar PV power generation, both using ANN-based models and other techniques from the literature, and optimizing EV charging schedules using Energy Storage Systems (ESSs). The study in30 explored AI-driven energy forecasting for EV charging infrastructure by investigating the capabilities of various forecasting techniques in accurately estimating solar and wind energy generation for EV CSs.

Collectively, these efforts demonstrate the effectiveness of AI-driven forecasting solutions in supporting EV CSs scheduling and decision-making processes. In practice, the impact of forecasting accuracy (or interchangeably, imperfect predictions) on EV charging scheduling costs is crucial and should also be considered. The uncertainty in EV arrival times, departure times, and charging volumes are potential causes of such imperfect predictions. To address these sources of uncertainty,31 proposed a risk-limiting charging scheduling approach using chance-constrained optimization in an offline setting. The authors developed a Model Predictive Control (MPC) approach for online scheduling of EV CSs. The obtained results demonstrated the significance of incorporating accurate forecasting and robust optimization techniques to enhance EV CSs’ scheduling efficiency.

Demand side management

DSM has become a pivotal strategy in addressing the challenges posed by the increasing integration of EVs into power grids. As EVs’ adoption accelerates, EVs need to be recharged when they are out of use. Such recharging may be performed during nighttime or when drivers are occupied by other tasks in various locations (malls, restaurants, etc.). Uncoordinated charging can lead to significant peak loads, stressing grid infrastructure, and potentially long waiting time32. DSM offers a suite of techniques aimed at optimizing energy consumption patterns, thereby ensuring grid stability and efficiency. In the context of EVs, DSM encompasses strategies such as smart charging, where EV charging is scheduled during off-peak hours, and vehicle-to-grid (V2G) technologies that allow EVs to discharge energy back into the grid during high-demand periods. These approaches not only mitigate the risk of grid overload but also enhance the utilization of renewable energy sources by aligning charging activities with periods of high renewable generation. Researchers such as in33, have developed efficient management strategies based on inference fuzzy systems (IFSs) to manage the available power at a parking lot level. Recent studies have highlighted the efficacy of DSM in managing EV charging demands. For instance, a comprehensive review emphasizes the role of DSM in facilitating the integration of EVs into smart grids, underscoring the importance of coordinated charging to prevent grid instability34,35,36. Furthermore, advanced control methodologies, such as model predictive control, have been proposed to dynamically adjust EV charging based on real-time grid conditions, electricity prices, and user preferences, thereby optimizing both grid performance and user satisfaction37.

From an operational perspective, DSM is a crucial component that serves as a foundational element in the sustainable integration of EVs into power systems. By leveraging advanced forecasting, optimization algorithms, and real-time communication technologies, DSM enables a more resilient and efficient energy ecosystem that accommodates the growing demands of electric mobility in terms of charging needs.

Path planning

Like the load profile forecasting, optimal path planning of EVs seeking charging (while riding) is crucial. Classical path planning, although efficient in static circumstances, may fail in dynamic conditions since the shortest path may not be the best way that drives the EV to the best charging station because of other constraints like the crowd and the route nature. In this sub-section, we will survey few studies tackling path planning, while concentrating on the trade-off between route feasibility and optimality.

Based on Martin’s algorithm, the study in38 provided EV users by a tool to select CSs and charging paths. The bidirectional version of the algorithm was reported to be efficient in selecting three candidate CSs. However, the main limitation of this approach is the computational burden induced by the calculation of the minimal distance between each CS and each node in the road network. This issue may be accentuated when the number of EVs seeking charging and the number of nodes in the network are relatively high. The study in39 proposed a general framework including information exchange between CSs, EVs and other parties involved in the traffic management. The study has been reported to help the EV user in selecting the best station. However, the objective functions optimized (charging cost, waiting time, etc.) for better charging experience were considered separately which may limit the inherent multi-objective aspect of the problem. The authors in40 have used the Route-Assisted Rapid Random Tree (RA-RRT*) algorithm for searching the most feasible routes and aggregators stopping points while considering SoC constraints. Although the results were reported to be acceptable, random tree algorithms may face challenges when used in a real-time because of each computational complexity. The study in41 has investigated a distributed Ant System (AS) algorithm to find the best CSs to which an EV may be driven. Although the usefulness of the study findings, the main limitation of this study is that it doesn’t consider the state of the road and that it is based only on the minimal path regardless of its hardness. In our study, Dijkstra algorithm will be used for path planning of EVs in need of charging during their trip since this algorithm is known to be lightweight and computationally tractable42.

Material and methods

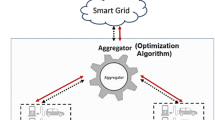

General framework of EV/CS allocation problem

In this paper, a general framework for the complex allocation of EVs in need of charging while riding, to the suitable CSs, is presented (Fig. 1).

The proposed unified framework is expected to improve both operational efficiency and user experience within the EV charging ecosystem. Unlike traditional approaches relying on static or limited data inputs, the present approach is inherently dynamic since it considers the EV needing charging is currently in road and extract real-time data about the traffic situation and the CSs current charging loads. In what follows, details of the framework components as well as their expected roles in the charging allocation problems are provided:

-

Load profile forecasting at the CSs (mainly in the short term) is crucial to anticipating fluctuations in electric load demand across different CSs and at different time periods. The main focus of this study is allocated to the real-time assistance of EVs to reach the optimal CS in its immediate surrounding or in the way of its current destination. In order to be efficient and informative, forecasting load profile should be conducted at all CSs in the covered urban area. The prediction of load is beneficial for the CS owner (helps him to manage the energy resources efficiently and therefore satisfy the customers’ needs) and for the EV (assist the driver about the load being requested at different CSs to prevent delays and waste of time if seeking charging from an overloaded CS).

-

Path planning is significant in the context of EV/CS allocation, as it directly affects the way an EV needing charging to efficiently reach the suitable CS. Path planning in urban area is inherently complex due to the road network structure and the number of vehicles. Additional complexity is added when considering the dynamic nature and the urgent need of charging. Effective path planning ensures that EV drivers can reach CSs with minimal cost either in traveling time or satisfaction of the constrained current SoC that may not allow the EV to reach the suitable CS.

-

Drone-enabled edge computing represents a transformative innovation in the management of EV charging operation in urban areas. As mobile computing units, fleet of drones equipped with edge computing capabilities can collect, process, and transmit data to optimize EV/CS allocation. In our framework, drones can assist in monitoring charging station availability, providing real-time data about crowd management which may assist the EV driver to select the best CS convenient to his needs. Additionally, drones can also collect information on road conditions around CSs including weather patterns. By operating at the edge of the network, drones reduce the need for centralized data processing and offer a decentralized solution for maintaining data integrity, security, and responsiveness across the charging infrastructure.

-

As the focus of this study is the implementation of an approach to allocate EVs seeking for charging to the optimal CSs, this section will detail the two main components of the proposed solution. Namely, the load profile forecasting at the CS level and the optimal path planning.

In the proposed framework, path planning and load forecasting are treated as distinct yet complementary components. The path planning module utilizes Dijkstra’s algorithm to identify the shortest feasible paths from the electric vehicles (EVs) to candidate charging stations. In parallel, a Nonlinear Auto-Regressive model with exogenous inputs (NARX) is employed to forecast the near-future load profiles at each charging station, offering predictive insight into energy consumption and slot availability. While these modules operate independently, their outputs are jointly considered during the EV’s decision-making process, allowing the selection of charging stations that are not only geographically accessible but also operationally optimal. For instance, an EV may bypass the nearest station if its predicted load suggests potential delays. Although our current implementation does not embed the load forecasting directly into the path planning algorithm, such as through load-weighted graph edge adjustments, this modular structure offers a flexible foundation for future integration of these components into a unified optimization framework.

The proposed general framework can be run according to the following pseudocode (Algorithm 1).

As described in the above pseudocode, each time an EV sends a request of recharging and its current location, the principal algorithm runs Dijkstra’s algorithm to find and later sort the CSs according to their respective distances. In addition, it calls the forecasting algorithm and runs it for all CSs. A compromised combination of distances and forecasted load profiles is then sent to the EV to select the best CS corresponding to its current situation in terms of remaining charge and CS’s probable waiting time.

Load profile forecasting

This subsection illustrates the overall methodology proposed to forecast the charging time (\(T\)) and ahead charging energy (\(E\)) for an EV-CS allocation (as depicted in Fig. 2). The pseudocode of the forecasting task is provided in Algorithm 2 below.

Note here that the forecasting horizon is crucial since shorter is this horizon, better impact may it add to the EV/CS assignment problem. In this study, we expect to investigate the feasibility/optimality of the forecasting based on daily dataset. However, for better participation in the EV/CS allocation problem, the forecasting should be performed for all CSs at a given urban area using large datasets preferably at the minimum horizon.

The overall collected dataset (\(\mathbf{X}\)) of an EV CS utilized in this work is established. Specifically, it comprises the charging events characterized by their associated remained feature values (i.e., \(\overrightarrow{M}\), \(\overrightarrow{Y}\), and \({\overrightarrow{W}}_{D}\)) in inputs and the corresponding response variables (\(\overrightarrow{T}\) or \(\overrightarrow{E}\)) in outputs:

For forecasting purposes, the predictors were used as inputs to a time series machine learning model while the two target variables were considered individually, with a separate model developed for forecasting each target variable. Specifically, two models were investigated, mainly due to ease of use, straightforward development, convenient computational requirements compared to other existing time series models, and their proven effectiveness in various engineering applications:

-

(1).

Nonlinear AutoRegressive (NAR)

-

(2).

Nonlinear AutoRegressive with eXogenous inputs (NARX).

Both are types of neural network models widely used in time series forecasting across various applications. The former is a type of RNN commonly used to forecast a response variable (hereafter denoted as \(y\)) solely based on its past values, considering an embedding dimension or feedback delay, \(d\) (Eq. (2)). On the other hand, NARX model extends NAR by considering exogenous (i.e., external) input variables (hereafter denoted as \(x\)) such as the variables available at hand, making it useful for systems influenced by both their history and exogenous (external) factors (Eq. (3)). Both consider the error/noise term, \(e(t)\), accommodating the unexplained or random variation in the model’s output, thus covering factors not captured by the function \(f\), as shown in Eq. (2) and Eq. (3) for NAR and NARX models, respectively:

For the forecasting task, predictions were made for one-day ahead (forecasting horizon 1, \({H}_{1}\)) for the two response variables: charging time (\(T\)) and charging energy (\(E\)).

The models were properly optimized in terms of the number of hidden neurons (\({N}_{h}\)) and feedback delays (\(d\)), with both parameters assumed to span the values from 1 to 10, representing their potential minimum and maximum candidate values.

The overall dataset was divided into three distinct sets: (i) training, (ii) validation, and (iii) test datasets, with random sampling portions of 60%, 20%, and 20%, respectively, for building, optimizing, and evaluating NAR and NARX models.

Two performance metrics were employed to evaluate the effectiveness of the forecasting models: Root Mean Square Error (\(RMSE\)) in kWh (Eq. (4)) and the Correlation Coefficient (\(R\)) in percentage (Eq. (5)). \(RMSE\) measures forecasting accuracy, while \(R\) emphasizes the strength of the relationship between the forecasted and true response values. Typically, lower \(RMSE\) and higher \(R\) values indicate the effectiveness of the built-forecasting models. For each combination of \({N}_{h}\) and \(d\), the simulation was repeated 10 times, with different random sampling of the dataset portions, and the performance metrics and their variability measured in terms of the standard deviation (\({\sigma }_{RMSE}\) and \({\sigma }_{R}\)) were computed on average. The optimal combination of \({N}_{h}\) and \(d\) is then identified at which \(RMSE\) is minimized.

where \({N}_{Valid}\) is the number of sampled-validation charging days, \({y}_{j}\) and \({\widehat{y}}_{j}\) are the \(j\)-th actual and forecasted response values, respectively, and \(\overline{y }\) and \(\overline{\widehat{y} }\) are the average actual and forecasted response values, respectively.

To measure the effectiveness of the built and optimized NAR and NARX models, the typical naïve forecasting model is built and effectively compared with the performance obtained by the optimal models on the test dataset. As a final remark, the computational efforts required for developing and optimizing the models were recorded to assess the efficiency of the model development process.

Optimal path planning

For EV/CS allocation problem, finding the optimal path an EV should follow to reach the best CS is challenging. In a dynamic context (as opposed to the static context where the route conditions are not considered), the shortest path may not be the best due to traffic congestion or route nature (such as bent or upward sloped routes). Under such conditions, optimal path-finding algorithms may be penalized if those conditions are well-understood. However, in this subsection, the main algorithms used for optimal planning are summarized, and a compromise choice of the best algorithm will be made.

For EV charging optimal path search, the shortest path algorithms consider a network where single-source/single-destination problems focus on finding the optimal path between a starting node (location of the EV in shortage of charge) and a target node (position of a CS) in a weighted graph. The three main algorithms used for this purpose, along with their advantages and limitations, are summarized as follows.

Dijkstra’s Algorithm Its principle of working is based on iteratively exploring the shortest known path to each vertex from the source43. It uses a priority queue to efficiently select the next node with the smallest tentative distance. Its main advantage is that it guarantees the shortest path in graphs with non-negative edge weights. Its application is usually preferred for dense graphs44. Although its usefulness, Dijkstra’s algorithm’s main limitation is that it computes paths to all vertices, which may be unnecessary when interested in only a single destination45.

Bellman-Ford Algorithm This algorithm uses relaxation to iteratively update the shortest paths by considering each edge multiple times46. It can handle graphs with negative edge weights and can detect negative weight cycles and report their existence. Compared to Dijkstra’s algorithm, it is known to be slower, especially on dense graphs.

A* Search Algorithm Known as simply A* (Star), this algorithm combines Dijkstra’s algorithm with a heuristic rule to prioritize nodes that are estimated to be closer to the destination47. It may be efficient for single-source/single-destination problems (like our problem). Its main limitation is that it requires a heuristic function, which may not always be easy to define or compute.

As our EV/CS allocation problem is single-source/single-destination, Dijkstra’s algorithm will be used as a compromised choice while considering its time complexity since the latter is proportional to the product of the number of vertices and the number of edges. The interested reader to the algorithm details may refer to42 and the references therein. The path planning algorithm proposed in this paper is provided in the following pseudocode (Algorithm 3).

Data records

The dataset used in this work for forecasting the charging energy demand is collected from48. It comprises 17 parameters whose description and units are provided in Table 1. The dataset spans the period from 18th November 2014 to 8th October 2015, with a total of 3395 charging events.

To gain further insights into the available dataset, Fig. 3 shows the distribution of charging events on a daily basis from Saturday to Friday, spanning the study period.

Figure 4 shows the hourly distribution of the charging energy (in kWh), fitted with a Smoothing Spline (red line) with \(SSE=13981, {R}^{2}=99.80\%,\) and \(RMSE=51.1985\) kWh. Figure 4 indicates two peaks of EV charging during the day: one occurring around midday (between 12 and 14 PM) and the other occurring in the early evening (between 17 and 19 PM), reflecting the typical EV charging times aligned with daily traffic patterns. It is worth mentioning that Fig. 4 only displays charging energy exceeding 50 kWh, for illustration purposes.

For day-ahead forecasting, the following features are selected, while the remaining ones were excluded due to irrelevance or redundancy, as they are already embedded within the considered features. Specifically, the selected features are extracted and transformed into the form of daily charging events:

-

Day of the year (feature 1, denoted as \(D\)). It represents the specific day of the month on which the charging event occurred, e.g., 18 for the 18th of the month and so on, capturing daily patterns in the charging events.

-

Month of the year (feature 2, denoted as \(M\)). It represents the specific month number of the year on which the charging event occurred, e.g., 11 for November and so on, capturing monthly patterns in the charging events.

-

Year identifier (feature 3, denoted as \(Y\)). It represents the year identifier in which the charging event occurred, e.g., 2014 and 2015, capturing yearly variations in the charging events.

-

Week day index/label (feature 4, denoted as \({W}_{D}\)). It assigns a label or index to each day of the week, e.g., 1 corresponds to Saturday and 7 corresponds to Friday, and so on, capturing weekly patterns in the charging events.

-

Total daily charging time (feature 5, denoted as \(T\)). It represents the total daily charging time spent in hours.

-

Total daily charging energy (feature 6, denoted as \(E\)). It represents the total daily charging energy spent charging in kWh.

Specifically, the charging events that occurred each day were aggregated into daily charging events for the purpose of day-ahead forecasting of the charging time (\(T\)) and energy (\(E\)) (i.e., response or dependent variables), based on the day of the year (\(D\)), month of the year (\(M\)), year identifier (\(Y\)), and weekday index or label (\({W}_{D}\)) (i.e., predictors or independent variables). The dataset was structured as a time series, and a data-driven machine learning model was employed for the forecasting task, predicting 1 day (forecasting horizon 1) for the two response variables, charging time and energy, \(T\) and \(E\), respectively. The established time series daily dataset comprises \(N=321\) days, covering the charging events that occurred between November 18, 2014 and October 8, 2015.

It is worth mentioning that there were no charging events on some days, and the associated charging time and energy values were replaced with NaN for the subsequent analysis of the forecasting task. Specifically, 25.86% of the data was missing (i.e., 83 days), while the remaining 74.15% was complete (i.e., 238 days).

Figure 5 shows the charging time (\(T\)) and charging energy (\(E\)) across the entire period of 321 days, including the missing operational days. The following insights can be stated:

-

Both features increase over time, highlighting the potential for an increase in EV charging events as time progresses.

-

The zoomed-in figure reveals cyclical charging patterns occurring at different times of the day, week, or across the operational period.

To effectively identify the most influential features and their impact on the predictability of both charging time and energy, Fig. 6 presents the Pearson correlation matrix for the six considered features. From the figure, the highest correlation values with charging time and energy are observed for the month of the year (\(M\)), followed by the weekday index/label (\({W}_{D}\)), and then the year identifier (\(Y\)). In contrast, the day of the year (\(D\)) shows the lowest correlation value of 0.06 and will therefore be excluded from the subsequent forecasting analysis.

Results and discussion

Load profile forecasting

Table 2 reports the optimal parameters (\({N}_{opt}\) and \({d}_{opt}\)) identified for each NAR and NARX models, along with the optimal performance metrics and computational efforts on the validation dataset obtained for forecasting the charging time (\(T\)) and the charging energy (\(E\)) one-day ahead. It is worth mentioning that the models were developed using MATLAB R2024a, running on a personal computer whose processor is 11th Gen Intel(R) Core (TM) i5-1135G7.

Looking at Table 2, one can notice the following:

-

NARX model achieves the best forecasting accuracy for both charging time and energy on the validation dataset. The model achieves an \(RMSE\) value of 17.08 h (~ 11.52% percentage error compared to the maximum charging time value recognized in the study period) and 30.27 kWh (~ 11.68% percentage error compared to the maximum charging energy value recognized in the study period) compared to those obtained by the NAR model with values equal to 28.06 h and 54.30 kWh, for forcasting the charging time and energy, respectively.

-

The NARX model, as expected, requires a larger number of hidden neurons to establish the mathematical relationship between the input sets and the output, compared to the NAR model, which relies solely on the historical values of the response variable.

-

As expected, the computational effort required to develop and optimize NARX models is greater than that for NAR model, due to the inclusion of additional exogenous (external) factors.

For clarification, Fig. 7 shows the evolution of the \(RMSE\) and \(R\) performance metrics versus the different values of \(N\) and \(d\). Figure 7a and b illustrate the evolution of \(RMSE\) against varying values of \(N\) (at \({d}_{opt}\)) and \(d\) (at \({N}_{opt}\)) candidates, respectively. Figure 7c and d display the evolution of \(R\) against varying values of \(N\) (at \({d}_{opt}\)) and \(d\) (at \({N}_{opt}\)) candidates, respectively, for charging time (\(T\)) forecasting, with an indication of the optimal (minimum) \(RMSE\) value obtained and the corresponding \(R\) value. Similarly, Fig. 8 shows the evolution of the two-performance metrics against the two variables for charging energy (\(E\)) forecasting. In Figs. 7 and 8, one can observe, as discussed, NARX model requires a large number of hidden neurons to effectively establish the relationship between the input sets and the output for charging time and energy, i.e., 10 and 8, respectively.

Once the NAR and NARX models are built and optimized, their effectiveness is evaluated against the typical forecasting model in the literature, naïve, on the unseen test dataset across the 10 different simulation trials. To robustly quantify the goodness of the built models, the performance metrics and their associated variability obtained across the 10 simulation trials are reported in Table 3, for completeness.

Looking at Table 3, one can state the following points:

-

NARX model outperforms the forecasting accuracy achieved by NAR and Naïve forecasting model for the two response variables, as expected, across almost the entire performance metrics.

-

The variability obtained by NARX is larger than that obtained by NAR model for the two response variables, as expected, due to the variability inherent in the additional exogenous (external) factors considered while developing the model.

It is worth noting that the 60%, 20%, and 20% splits for training, validation, and test data were consistently maintained across the 10 simulation trials when developing the NAR and NARX models to ensure a fair comparison. Additionally, the differences observed in the Naïve approach results across the two response variables are due to the distinct optimal configurations identified for each model (NAR and NARX). These differences led to varying test dataset splits, which in turn produced varied yet consistent outcomes for the Naïve forecasting approach.

For the sake of clarity, the best simulation trials (i.e., trial #9 for charging time and trial #8 for charging energy) were selected to illustrate examples of the one-day ahead forecasts made by the NARX model for charging time (Fig. 9a) and energy (Fig. 9b). Notably, there is a significant match between the true/actual and forecasted values of both charging time and energy across the selected days. This alignment also highlights how effectively the NARX model detects trends, confirming its accuracy in forecasting the two response variables.

For completeness regarding the load profile forecasting of EV CSs, Table 4 presents a comprehensive comparison between the proposed approach and other forecasting approaches reported in the literature. As reported in Table 4, the reviewed studies cover a wide range of machine/deep learning and hybrid forecasting approaches applied, for instance, to EV CSs, focusing on short-term EV charging demand and/or electricity consumption. Specifically, two key points can be highlighted:

-

the current study introduces a novel integration of ahead load profile forecasting using an NARX model, integrated with optimal path planning via Dijkstra’s algorithm and real-time availability checking using lightweight drone-based edge computing. In contrast, most of the reported studies focus mainly on improving forecasting accuracy based on standard performance metrics, whereas the proposed framework of this study extended to couple the forecasting outcomes with real-time decision-making and CS allocation strategies, offering a more holistic approach that addresses not only forecasting accuracy but also practical operational challenges, e.g., EV CSs availability, congestion, and optimal routing.

-

It is crucial to emphasize that conducting a complete quantitative comparison across all literature studies is inherently challenging due to the diversity of metrics employed, differences in datasets, variations in forecasting horizons, and the specific system contexts investigated.

Optimal path planning

In this subsection, the efficiency of Dijkstra’s algorithm in supporting the optimal assignment of an EV to a CS is illustrated through small-size case studies. The routes network is modelled as a directed graph composed of nodes and edges with known weights (which is the case if the road network is well-established). Additionally, the CSs locations are also known in advance which is the case of an established road infrastructure. We assume that any EV seeking charging is positioned at a node of the network (the case where the EV is between two nodes is not considered). We assume also that the remaining EV charge is able to drive it to any of the CSs and that the information on availability of charging slots at all nearby CSs is communicated by the fleet of drones and that this information can be shared with the EV (either the driver or the EV itself if it is autonomous).

To evaluate the proposed optimal path planning and EV-to-charging station allocation framework, we constructed a set of artificial graph-based scenarios that simulate a simplified road network. These graphs consist of nodes representing intersections or locations and edges representing roads with associated weights (e.g., distance or travel cost). Charging stations were strategically placed at selected nodes, while electric vehicles were randomly assigned to starting nodes. This synthetic setup was chosen to allow controlled testing of the framework’s performance under varied and customizable conditions. It also enabled flexibility in modelling edge weights, network density, and station distributions, parameters that would be difficult to manipulate in a fixed real-world dataset. While this study focuses on validating the methodology in a controlled environment, future work will involve applying the framework to real-world EV infrastructure data to further assess its scalability and practical applicability.

Case#1 To illustrate the effectiveness of the proposed approach, a network composed of 15 vertices and edges with random weights are generated and used (See Table 5). The adjacency matrix is deliberately chosen as asymmetric which indicates that two adjacent vertices are connected via two roads with different weights. The case study information is summarized in Table 5.

The road network was generated randomly with edges’ weights between 0 and the maximum weight of edges. Additionally, the three CSs were positioned randomly at specific nodes of the network. The network adjacency matrix as well as the positions of CSs are provided in Table 6 below.

After running Dijkstra’s algorithm for the shortest path in term of distance (or time), the cost of the paths as well as the best CS an EV seeking for charging is allocated are summarized in Table 7. Moreover, a schematic illustration of this case scenario is depicted in Fig. 10.

In this case scenario, EV1 and EV2 are allocated to CS1. If both EVs request charging at the same time, EV2 has a higher chance to reach CS1 before EV1. Therefore, the charging schedule at CS1 should be updated to include EV2 and later include EV1. Additionally, since EV3 and EV4 are assigned to CS2, EV3 may arrive to the charging station earlier and has a chance to be charged faster than EV4.

Case#2 In this second case, a larger network involving 50 nodes, 5 CSs and 10 EVs is considered. For space limitation, only the results of the EVs/CSs assignment (Table 8) as well as the graph (Fig. 11) are provided.

The results of the second case study (Case#2) showed the potential of the proposed approach to provide optimal solution of the EV path planning in the context of EV/CS allocation problem. However, it was noticed that the larger the network is, more the algorithm takes time to provide the solution.

Although Dijkstra’s algorithm offers computational efficiency in moderately sized networks, its scalability is limited in large-scale, real-time EV charging systems. To overcome this, future work will explore advanced and scalable path planning techniques. These may include heuristic methods such as the A* algorithm, which uses informed search to reduce computation time, and hierarchical routing methods that simplify graph complexity through abstraction. Furthermore, integrating edge computing resources can enable distributed processing of route computations across multiple nodes. We also envision the use of machine learning–based path planning, particularly reinforcement learning, to dynamically adapt to changing traffic patterns and charging station availability. These enhancements aim to ensure real-time responsiveness and efficiency in large-scale deployment scenarios.

A major limitation of this study is the absence of experimental validation or detailed simulation results. This is due in part to the complexity of deploying drone-based systems for critical infrastructure support, which involves not only technical development but also adherence to strict aviation safety standards and regulatory protocols. Future work will focus on developing simulated environments to model realistic drone behaviors, communication latency, edge processing loads, and route allocation efficiency, while also incorporating real-world constraints imposed by aviation authorities and urban planning considerations.

Conclusions and future directions

With the large-scale adoption of EVs worldwide, operational issues such as the limited number of CSs being deployed in urban areas and the relatively long charging time are being faced nowadays. From economic and time perspectives, the installation of CSs is not an easy task. In addition, decreasing EV’ charging time is challenging because of grid stability and the high probability of battery deterioration. Therefore, the number of CSs cannot expand quickly, and the charging time cannot be shortened easily. Under such conditions, the unique remaining solutions may be built around optimizing the use of charge and the scheduling of the recharging operation.

To contribute to this domain, this paper develops a framework including three components, namely, load profile forecasting, optimal path planning and fleet of drones to assist the EV users in selecting the best CS. The main focus of this paper was on the first two components. The load profile prediction at the CS level was performed based on a nonlinear autoregressive model (NARX) and the path planning was based on Dijkstra’s algorithm. The experimental results have shown that the proposed algorithm for ahead load forecasting is efficient. Additionally, optimal path planning has provided good feasible paths toward optimal CSs. Once combined, the proposed approach components enforced by information about the CSs availability and the traffic situation in terms of crowd analysis, may assist the EV driver (or the EV itself if it is autonomous) to select the best CS. However, the findings of this paper may be strengthened by considering the user preferences (such as selecting CSs existing in its current route) and considering a shorter horizon for the forecasting at the CS level.

Future work will focus on several key areas to enhance and validate the proposed framework. First, we plan to develop high-fidelity simulation environments that model large-scale urban deployments, including dynamic EV flows and charging demand. This will allow for performance benchmarking under realistic conditions. Second, more scalable path planning algorithms, such as heuristic (e.g., A*) or learning-based approaches, will be explored to improve computational efficiency. Third, the integration of regulatory considerations related to drone operations (e.g., airspace restrictions, safety protocols, and licensing requirements) will be considered. Finally, we aim to prototype a decentralized architecture leveraging edge computing for real-time data processing and decision-making, which will help assess latency, fault tolerance, and robustness in practical settings. These improvements will significantly advance the feasibility and deployment readiness of the proposed system.

Data availability

The data used in this study are included within the manuscript. The data used for implementing the forecasting algorithms are available at https://data.mendeley.com/datasets/5zrtmp7gwd/2.

Abbreviations

- ANN:

-

Artificial neural network

- ARMA:

-

Auto regressive moving average

- ARIMA:

-

Auto regressive integrated moving average

- AS:

-

Ant system

- BPNN:

-

Backpropagation neural network

- CSs:

-

Charging stations

- CNN:

-

Convolutional neural network

- R2 :

-

Coefficient of determination

- R:

-

Correlation coefficient

- DT:

-

Decision tree

- ESSs:

-

Energy storage systems

- EVs:

-

Electric vehicles

- GRU:

-

Gated recurrent unit

- GA:

-

Genetic algorithm

- IoT:

-

Internet of things

- KNN:

-

K-nearest neighbor

- LSTM:

-

Long short-term memory

- Light-GBM:

-

Light gradient boosting machine

- MINLP:

-

Mixed-integer non-linear programming

- MEC:

-

Mobile edge computing

- MSE:

-

Mean square error

- MAE:

-

Mean absolute error

- MAPE:

-

Mean absolute percentage error

- MPC:

-

Model predictive control

- nRMSE:

-

Normalized RMSE

- NAR:

-

Nonlinear autoregressive

- NARX:

-

Nonlinear Autoregressive with eXogenous inputs

- PLSR:

-

Partial least squares regression

- RNN:

-

Recurrent neural network

- RMSE:

-

Root MSE

- RL:

-

Reinforcement learning

- RF:

-

Random forest

- RA-RRT*:

-

Route-assisted rapid random tree

- SoC:

-

State of charge

- SARIMA:

-

Seasonal auto regressive integrated moving average

- SVMs:

-

Support vector machines

- X :

-

Overall collected dataset for regression

- N :

-

Number of days in X

- \({N}_{Valid}\) :

-

Number of validation charging days

- \({N}_{h}\) :

-

Number of hidden neurons

- \(f\) :

-

NAR and NARX function

- \(x\) :

-

Input variables

- \(y\) :

-

Response variable

- \(d\) :

-

Feedback delay

- \(e\) :

-

Error/noise term

- \({y}_{j}\) , :

-

\({\widehat{y}}_{j}: j\)-Th actual and forecasted responses

- \(\overline{y }\),\(\overline{\widehat{y} }\) :

-

Average actual and forecasted responses

- \(\overrightarrow{D}\) :

-

Day of the year

- \(\overrightarrow{M}\) :

-

Month of the year

- \(\overrightarrow{Y}\) :

-

Year identifier

- \({\overrightarrow{W}}_{D}\) :

-

Weekday index/label

- \(T\) :

-

Total daily charging time

- \(E\) :

-

Total daily charging energy

- \({\sigma }_{RMSE}\) :

-

RMSE standard deviation

- \({\sigma }_{R}\) :

-

R standard deviation

- \({N}_{opt}\) :

-

Optimal number of hidden neurons

- \({d}_{opt}\) :

-

Optimal feedback delay

References

Hussain, S. et al. Enhancing electric vehicle charging efficiency at the aggregator level: A deep-weighted ensemble model for wholesale electricity price forecasting. Energy 308, 132823 (2024).

Jia, Z., Li, J., Zhang, X.-P. & Zhang, R. Review on optimization of forecasting and coordination strategies for electric vehicle charging. J. Mod. Power Syst. Clean Energy 11, 389–400 (2022).

Chen, Q. & Folly, K. A. Application of artificial intelligence for EV charging and discharging scheduling and dynamic pricing: A review. Energies 16, 146 (2022).

Al-Ogaili, A. S. et al. Review on scheduling, clustering, and forecasting strategies for controlling electric vehicle charging: Challenges and recommendations. IEEE Access 7, 128353–128371 (2019).

Hussain, S. et al. Hybrid coordination scheme based on fuzzy inference mechanism for residential charging of electric vehicles. Appl. Energy 352, 121939 (2023).

Dang, Q., Wu, D. & Boulet, B. Ev charging management with ann-based electricity price forecasting. In 2020 IEEE Transportation Electrification Conference & Expo (ITEC) 626–630 (IEEE, 2020).

Savari, G. F., Krishnasamy, V., Sathik, J., Ali, Z. M. & Aleem, S. H. A. Internet of Things based real-time electric vehicle load forecasting and charging station recommendation. ISA Trans. 97, 431–447 (2020).

Lu, J., Yin, W., Wang, P. & Ji, J. EV charging load forecasting and optimal scheduling based on travel characteristics. Energy 311, 133389 (2024).

Yin, W. & Ji, J. Research on EV charging load forecasting and orderly charging scheduling based on model fusion. Energy 290, 130126 (2024).

Gattuso, D., Cassone, G. C. & Malara, M. Traffic flows surveying and monitoring by drone-video. In New Metropolitan Perspectives Vol. 178 (eds Bevilacqua, C. et al.) 1541–1551 (Springer, 2021).

Husman, M. A. et al. Unmanned aerial vehicles for crowd monitoring and analysis. Electronics 10, 2974 (2021).

Liyakat, K. S. S. & Liyakat, K. K. S. IoT in electrical vehicle: A study. J. Control Instrum. Eng. 9, 15–21 (2023).

Cao, Y. et al. Mobile edge computing for big-data-enabled electric vehicle charging. IEEE Commun. Mag. 56, 150–156 (2018).

Chamola, V., Sancheti, A., Chakravarty, S., Kumar, N. & Guizani, M. An IoT and edge computing based framework for charge scheduling and EV selection in V2G systems. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 69, 10569–10580 (2020).

Butilă, E. V. & Boboc, R. G. Urban traffic monitoring and analysis using unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs): A systematic literature review. Remote Sens. 14, 620 (2022).

Hamrouni, A., Ghazzai, H., Menouar, H. & Massoud, Y. Multi-rotor UAVs in crowd management systems: Opportunities and challenges. IEEE Internet Things Mag. 6, 74–80 (2023).

Aksan, F., Suresh, V. & Janik, P. Optimal capacity and charging scheduling of battery storage through forecasting of photovoltaic power production and electric vehicle charging demand with deep learning models. Energies 17, 2718 (2024).

Akshay, K. C., Grace, G. H., Gunasekaran, K. & Samikannu, R. Power consumption prediction for electric vehicle charging stations and forecasting income. Sci. Rep. 14, 6497 (2024).

Han, X., Wei, Z., Hong, Z. & Zhao, S. Ordered charge control considering the uncertainty of charging load of electric vehicles based on Markov chain. Renew. Energy 161, 419–434 (2020).

Aduama, P., Zhang, Z. & Al-Sumaiti, A. S. Multi-feature data fusion-based load forecasting of electric vehicle charging stations using a deep learning model. Energies 16, 1309 (2023).

Ostermann, A. & Haug, T. Probabilistic forecast of electric vehicle charging demand: Analysis of different aggregation levels and energy procurement. Energy Inform. 7, 13 (2024).

Zhao, X. & Liang, G. Optimizing electric vehicle charging schedules and energy management in smart grids using an integrated GA-GRU-RL approach. Front. Energy Res. 11, 1268513 (2023).

Sasidharan, P. M., Kinattingal, S. & Simon, S. P. Comparative analysis of deep learning models for electric vehicle charging load forecasting. J. Inst. Eng. India Ser. B 104, 105–113 (2023).

Lee, Z. J., Li, T. & Low, S. H. ACN-Data: Analysis and applications of an open EV charging dataset. In Proceedings of the Tenth ACM International Conference on Future Energy Systems 139–149 (ACM, Phoenix AZ USA, 2019). https://doi.org/10.1145/3307772.3328313.

Kumar, N., Kumar, D. & Dwivedi, P. Load forecasting for EV charging stations based on artificial neural network and long short term memory. In Advanced Network Technologies and Intelligent Computing Vol. 1534 (eds Woungang, I. et al.) 473–485 (Springer, 2022).

Liu, J. et al. Data-driven intelligent EV charging operating with limited chargers considering the charging demand forecasting. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 141, 108218 (2022).

Ghenai, C., Ahmad, F. F. & Rejeb, O. Artificial neural network-based models for short term forecasting of solar PV power output and battery state of charge of solar electric vehicle charging station. Case Stud. Thermal Eng. 61, 105152 (2024).

Sheik Mohammed, S. et al. Charge scheduling optimization of plug-in electric vehicle in a PV powered grid-connected charging station based on day-ahead solar energy forecasting in Australia. Sustainability 14, 1–20 (2022).

Subashini, M. & Sumathi, V. Smart algorithms for power prediction in smart EV charging stations. J. Eng. Res. 12, 124–134 (2024).

Shetty, N. et al. AI-driven energy forecasting for electric vehicle charging stations powered by solar and wind energy. In 2024 12th International Conference on Smart Grid (icSmartGrid) 336–339 (IEEE, 2024).

Zhang, Y., Wu, C. & Lu, C. Risk-limiting multi-station EV charging scheduling with imperfect prediction. In 2022 7th IEEE Workshop on the Electronic Grid (eGRID) 1–5 (IEEE, 2022).

Hussain, S., Kim, Y.-S., Thakur, S. & Breslin, J. G. Optimization of waiting time for electric vehicles using a fuzzy inference system. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 23, 15396–15407 (2022).

Hussain, S., Ahmed, M. A. & Kim, Y.-C. Efficient power management algorithm based on fuzzy logic inference for electric vehicles parking lot. IEEE Access 7, 65467–65485 (2019).

Mohanty, S. et al. Demand side management of electric vehicles in smart grids: A survey on strategies, challenges, modeling, and optimization. Energy Rep. 8, 12466–12490 (2022).

Sarker, E. et al. Progress on the demand side management in smart grid and optimization approaches. Int. J. Energy Res. 45, 36–64 (2021).

Mwasilu, F., Justo, J. J., Kim, E.-K., Do, T. D. & Jung, J.-W. Electric vehicles and smart grid interaction: A review on vehicle to grid and renewable energy sources integration. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 34, 501–516 (2014).

Gbadega, P. A. & Saha, A. K. Predictive control of adaptive micro-grid energy management system considering electric vehicles integration. Int. J. Eng. Res. Afr. 59, 175–204 (2022).

Hou, W., Luo, Q., Wu, X., Zhou, Y. & Si, G. Multiobjective optimization of large-scale EVs charging path planning and charging pricing strategy for charging station. Complexity 2021, 8868617 (2021).

Kumar, A., Kumar, R. & Aggarwal, A. S2RC: A multi-objective route planning and charging slot reservation approach for electric vehicles considering state of traffic and charging station. J. King Saud Univ.-Comput. Inf. Sci. 34, 2192–2206 (2022).

Muhammad, S. & Zhou, Y. Path planning for EVs based on RA-RRT* model. Front. Energy Res. 10, 996726 (2023).

Elgarej, M., Khalifa, M. & Youssfi, M. Optimized path planning for electric vehicle routing and charging station navigation systems. In Research Anthology on Architectures, Frameworks, and Integration Strategies for Distributed and Cloud Computing 1945–1967 (IGI Global, 2021).

Alshammrei, S., Boubaker, S. & Kolsi, L. Improved Dijkstra algorithm for mobile robot path planning and obstacle avoidance. Comput. Mater. Contin 72, 5939–5954 (2022).

Bing, H. & Lai, L. Improvement and application of Dijkstra algorithms. Acad. J. Comput. Inf. Sci. 5, 97–102 (2022).

Chen, Y. Application of improved dijkstra algorithm in coastal tourism route planning. J. Coastal Res. 106, 251–254 (2020).

Zhu, Z., Li, L., Wu, W. & Jiao, Y. Application of improved Dijkstra algorithm in intelligent ship path planning. In 2021 33rd Chinese Control and Decision Conference (CCDC) 4926–4931 (IEEE, 2021).

Parimala, M., Broumi, S., Prakash, K. & Topal, S. Bellman-Ford algorithm for solving shortest path problem of a network under picture fuzzy environment. Complex Intell. Syst. 7, 2373–2381 (2021).

Erke, S. et al. An improved A-Star based path planning algorithm for autonomous land vehicles. Int. J. Adv. Rob. Syst. 17, 1729881420962263 (2020).

Gholizadeh, N. & Musilek, P. Daily electric vehicle charging dataset for training reinforcement learning algorithms. Data in Brief 110587 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by the University of Jeddah, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, under grant No. (UJ-23-SRP-10). The authors, therefore, thank the University of Jeddah for its technical and financial support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Supervision: Sahbi Boubaker; Conceptualization: Sahbi Boubaker, Souad Kamel, Nejib Ghazouani, Faisal S. Alsubaei, Mohamed Benghanem and Farid Bourennani; Formal analysis: Souad Kamel, Farid Bourennani, Habib Kraiem, and Adel Mellit; Investigation: Sahbi Boubaker, Sameer Al-Dahidi and Walid Meskine; Writing the initial draft: Sahbi Boubaker, Sameer Al-Dahidi and Nejib Ghazouani; Data curation: Sahbi Boubaker and Sameer Al-Dahidi; Funding acquisition: Sahbi Boubaker; Reviewing the manuscript: Mohamed Benghanem, Faisal S. Alsubaei, Habib Kraiem and Adel Mellit; Methodology: Sahbi Boubaker and Sameer Al-Dahidi; Implementation: Sahbi Boubaker and Sameer Al-Dahidi.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Boubaker, S., Al-Dahidi, S., Kamel, S. et al. Electric vehicles charging station allocation based on load profile forecasting and Dijkstra’s algorithm for optimal path planning. Sci Rep 15, 23844 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-08840-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-08840-3